1. Introduction

Well-being and health concerns have driven researchers to develop alternative technologies to synthesize increasingly versatile biomolecules through new production processes to meet an increasingly demanding market [

1,

2,

3]. Prebiotics have been steadily increasing the interest of the scientific community due to their ability to not only meet nutritional needs but also to enable better health conditions along with the proper functioning of the organism [

2,

3,

4]. Galactooligosaccharides (GOS) are an important class of dietary oligosaccharides that are not digestible by the human body and act as prebiotics [

1,

3,

5,

6,

7]. These nutrients contain in their structure terminal glucose residues and galactose monomers linked by glycosidic bonds of the type Gal β(1→3), Gal β(1→6), Gal β(1→4), and may present different degrees of polymerization, configurations or even chemical compositions, depending on the process conditions as well as on the microbial origin of the enzyme used in the reaction [

3,

4,

8,

9,

10]. Among the main benefits of GOS consumption are the bifidogenic effect, suppression of pathogenic bacterial activity, decreased incidence of infections and colon cancer, reduced formation of toxic metabolites, increased mineral absorption, and strengthening of the immune system [

4,

11]. In this context, GOS synthesis has been widely studied for application in different industrial sectors, such as food, pharmaceutical, and, more recently, agricultural [

1,

9,

12].

GOS are enzymatically synthesized through a transgalactosylation reaction catalyzed by β-galactosidase (EC 3.2.1.23), which is favored by the high concentration of lactose and high temperatures [

1,

13]. This reaction must be strictly controlled due to the competition that occurs between the two reactions performed by the β-galactosidase, that is, lactose hydrolysis and transgalactosylation [

2,

9,

13,

14]. Nevertheless, improvements regarding the process of obtaining GOS are continuously investigated, with the enzyme immobilization approach being one of the potentially promising strategies to allow for greater catalyst stability, in addition to being a potentially reusable resource with easy product recovery [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Furthermore, the reuse of biocatalysts leads to a reduction in operating costs and enables the continuous bioreactor system [

3,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Considering the above aspects, it is evident that enzymatic immobilization leads to an increase in productivity as well as a reduction in the costs associated with the process of obtaining the final product [

19,

23,

24,

26,

27].

In addition to these advantages, the sustainable production of GOS has been widely reported using dairy waste, currently recognized as a by-product of industrial processes, such as cheese whey, which is an alternative and inexpensive source of substrate [

23,

25,

28,

29]. The valorization of this industrial by-product is an important strategy, considering the reduction of environmental impact due to the inadequate disposal of these resources, as well as the potential recovery of nutrients with high biological value, contributing to the sustainable generation of biotechnological products [

22,

23,

24,

25,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Approximately 50 % of cheese whey produced is used in the food sector and pharmaceutical formulations, the remaining volume is of considerable amount to be used in bioprocesses to obtain biotechnological products with high added value [

3,

15,

19,

23,

25,

29,

34].

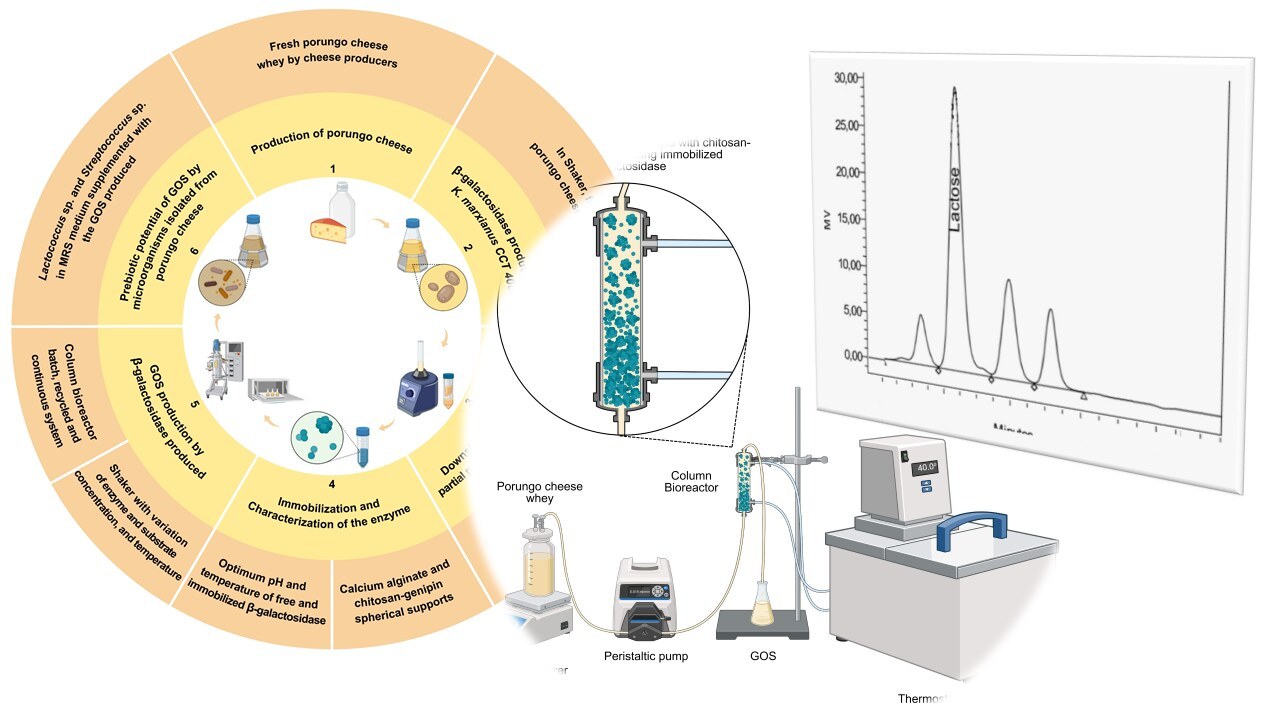

In this sense, the present research aims to study the use of Porungo cheese whey to obtain galactooligosaccharides (GOS) by means of enzymatic immobilization technology, using different bioprocess approaches and column bioreactors with different operating modes (

Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Porungo cheese whey was provided by farmers located in the southwest of the State of São Paulo, Brazil (geocoordinates 23º29’04.2”S and 48º20’14.7”W). K. marxianus CCT 4086 was provided by Tropical Culture Collection of André Tosello Foundation (Campinas, Brazil), both donated by Biotechnology & Biochemical Engineering Laboratory (BiotecLab), of the Food Science and Technology Institute (ICTA) of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Chitosan (from shrimp shells, ≥75% deacetylated), genipin (≥98%), ONPG (O-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside), Bradford reagent, D-glucose, D-galactose and lactose were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (São Paulo, Brazil). All solvents and other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Production, Extraction, and Partial Purification of the Enzyme

The β-galactosidase enzyme production was carried out under the optimized conditions previously established by our research group [

35], using the yeast

Kluyveromyces marxianus CCT 4086 (30 ºC, 200 rpm and pH 7.0), using Porungo cheese as substrate, containing 4.99 % of lactose and 0.81 % of protein (

Appendix A1), during 24 h of cultivation. The inoculum was adjusted for optical density 1.0 at 600 nm (OD

600nm), which corresponded to 1.4 g/L (dry weight) of strain

K. marxianus CCT 4086, added as 10 % volume of the final fermentation volume. To avoid protein precipitation during the sterilization process, the cheese whey was previously hydrolyzed with commercial protease (Alcalase 2.4 L, Tovani Benzaquen Ingredients, SP, Brazil), at 55 °C, pH 8.5 for 3 h. For cell recovery, the fermentation medium was centrifuged (3 000 × g for 15 min) and the cell pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3) for further enzymatic extraction. Cell disruption was carried out by two methods: mechanical disruption and chemical solubilization of cell wall. The former was performed according to the modified method of Medeiros [

36], using 1.1 g of glass beads (between 0.6 and 0.85 mm in diameter) per mL of suspension culture with a vortex for abrasion, and the latter was performed by adding chloroform 2 % (v/v) to the cell suspension and incubation at 150 rpm, 37 ºC, 17 h. Subsequently, the enzyme concentration was evaluated by 3 different strategies, the first two using chemical agents, namely an 80 % saturated ammonium sulfate solution and acetone, while the third used ultrafiltration membranes (10 kDa). Precipitation was performed using 80 % saturated ammonium sulfate solution, as described by Lima [

37], at 4 ºC for 24 h, after which the mixture was centrifuged (12 000 × g, 30 min, at 4 ºC), and the precipitate was resuspended in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and then desalted by dialysis through a 10 kDa membrane (GE Healthcare). Acetone precipitation was evaluated according to the modified methodology of Li [

38], where three times the volume of crude enzyme extract was added under gentle stirring (4 ºC), followed by resting (20 min, -8 ºC) and centrifugation (12 000 × g, 30 min, 4 ºC). The precipitate was then evaporated and resuspended in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

2.2.2. Optimal pH and Temperature of Free and Immobilized Enzyme

The immobilization of β-galactosidase was performed using two approaches: 1) using calcium alginate; and 2) using a chitosan-genipin complex. Immobilization in calcium alginate was performed according to the methodology of Bolognesi [

39], where a solution containing 5 % sodium alginate was mixed with the β-galactosidase and then dripped through a peristaltic pump containing a needle-coupled syringe with a 0.05 M calcium chloride (CaCl

2) solution to form spheres. Immobilization in chitosan was performed according to the method described by Klein [

40]. Beads were prepared by dissolving 2 % in 0.35 M acetic acid and dropped into the coagulation solution containing 1 M sodium hydroxide and 26 % ethanol. The beads were then washed with distilled water to neutrality, followed by activation with 0.5 % genipin for 3 h with gentle shaking, and kept in contact with β-galactosidase solution for 5 h with gentle shaking (4 ºC). The optimal pH of enzyme activity concerning both free and immobilized enzymes on the two different immobilization support materials was evaluated using a 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer containing a 1.5 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl

2) solution at 37 ºC, with a pH range of 5.5 to 8.0. The optimum enzyme activity temperature for free and immobilized enzymes on both supports was found to be in the range of 20 ºC to 60 ºC, at pH 7.0. Enzymatic activity was determined according to the methodology described below.

2.2.3. GOS Production in Shaker

GOS yield using immobilized β-galactosidase on chitosan-genipin supports was determined by evaluating the influence of several variables: temperature (37 ºC to 43 ºC), immobilized enzyme concentration (50 U/mL to 150 U/mL), and concentration of Porungo cheese whey (200 g/L, 300 g/L and 400 g/L). All tests were performed using 125 mL conical flasks filled with 30 % of the reaction volume and chitosan-genipin beads. All experiments were performed in duplicate. Samples were collected periodically, centrifuged (3 000 × g for 15 min), and filtered through a cellulose acetate membrane (0.22 μm) for further analysis of sugars and galactooligosaccharides.

2.2.4. GOS Production in Bioreactor

The production of GOS using a packed-bed batch column bioreactor (

Figure 2) was carried out under the conditions described in the previous step. The bioreactor was operated in batch mode at a temperature of 40 ºC with 300 g/L Porungo cheese whey, using β-galactosidase immobilized on the chitosan-genipin support (100 U/mL), which filled 60 % of the volume of the bioreactor column. Temperature control was kept by a thermostatic bath coupled to the water jacket of the bioreactor. The operational stability of the system was evaluated in bioreactors operated in a repeated batch of 7 cycles (4 h each) for a total of 28 h of reaction. At the end of each cycle, the same volume of substrate was immediately added to the bioreactor to start the new cycle. Samples were collected periodically and treated as described in section 2.4. All experiments were carried out in duplicate.

The continuous packed-bed bioreactor was operated at varying feed rates (1 mL/h - 3 mL/h) using Porungo cheese whey (300 g/L) and β-galactosidase immobilized on chitosan-genipin (100 U/mL). The feeding was started after 3 h of batch operation. Temperature control was kept by a thermostatic bath coupled to the water jacket of the bioreactor (40 ºC). Samples were collected periodically and processed as described in section 2.4. All experiments were carried out in duplicate.

2.2.5. GOS as a Potential Prebiotic

Two strains isolated from Porungo cheese, Lactococcus QP 40 and Streptococcus QP 32, and a commercial strain, Lactococcus lactis ATCC 19435, were used to evaluate their ability to metabolize GOS. The inoculum was prepared from the different strains in MRS medium (37 ºC, 50 rpm, for 18-20 h). A 10 % aliquot (OD600nm = 1.0) was then added to a 250 mL conical flask containing 50 mL MRS plus GOS (37 ºC, 50 rpm, for 96 h). The MRS medium was used as a control for the 3 strains tested here. All experiments were performed in duplicate, and samples were collected periodically. Samples were centrifuged (3 000 × g, 15 min) to determine biomass and then filtered with a cellulose acetate membrane (0.22 μm) for further analysis of HPLC sugar consumption.

2.2.6. Analytical Methods

The enzymatic activity of free β-galactosidase was performed using ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) as substrate, according to the methodology described by Klein [

17], and the determination of released o-nitrophenol (ONP) was performed with a spectrophotometer at 415 nm. The amount of protein in the enzymatic solutions was analyzed according to the methodology of Bradford [

41], using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard protein, with a spectrophotometer at 595 nm. The determination of cell concentration was performed according to the methodology proposed by Gabardo [

23], by measuring the absorbance in a spectrophotometer (OD

600nm) and correlating it with dry weight (g/L) using a calibration curve. GOS and monosaccharide analyses were performed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Shimadzu SCL-10A) equipped with a Shimadzu RID-10A detector using a SUPELCOGEL Ca

+2 column (30 cm × 7.8 mm). The column and detector temperatures were maintained at 80 °C and 40 °C, respectively. Samples were eluted with Milli-Q water at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, and the chromatograms were integrated using the software LC solution. The identification of the different carbohydrates was done using external calibration based on commercially available standards.

2.2.7. Statistics

Data were statistically evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Statistica 12.5 software (StatSoft, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Production, Extraction, and Partial Purification of the Enzyme

Before the extraction and purification, β-galactosidase was produced by fermentation on Porungo cheese whey as substrate according to a method optimized by our research group [

35]. As a result, the maximum enzymatic activity reached 17.46 U/mL, and after 15 h of cultivation, the remaining lactose in the medium was only 4.66 g/L (

Appendix A2), corresponding to 91 % of lactose consumption. Since β-galactosidase is intracellular, cell disruption is an essential step in obtaining this enzyme [

36,

37,

42]. In the present study, two methods of

K. marxianus cell disruption, mechanical and chemical, were tested. Although the glass bead abrasion disruption method showed similar enzymatic activity values as the chloroform solubilization of cell wall method (

Table 1), it was observed that the specific enzymatic activity (44.21 U/g ± 3.64 U/g) was higher when the chemical method was used. Similar results were obtained by Numanoglu and Sungur [

43] when comparing the physical and chemical methods of

K. lactis ATCC 8583 disruption. The authors reported that the enzymatic activities were practically the same when testing the mechanical disruption with glass beads (2.66 µmol/min.mg cell) as well as with the chloroform-ethanol solution (3.0 µmol/min.mg cell), further emphasizing that the physical method was chosen to avoid the probable risk of toxicity associated with this chemical procedure. In contrast, Dagbagli and Goksungur [

42] reported that the mechanical disruption of

K. lactis NRRL Y-8279 cells with glass beads (3,038.9 U/g cells) was more efficient than disruption using either Triton X-100 (1,888.8 U/g) or SDS (964.3 U/g). Mechanical methods seem to be more efficient and more widely applicable than chemical methods, even though less specific. Chemical cell wall digestion, on the other hand, presents toxicity risks and requires downstream procedures to treat the generated wastes, in addition to being corrosive to the equipment [

36,

43,

44]. The mechanical disruption technique was found to be more suitable in this work, considering that the objective was to use the β-galactosidase enzyme to obtain GOS for food applications.

Different enzyme concentration strategies were evaluated since the produced enzyme should be used in column bioreactors filled with immobilized enzyme supports. Acetone, saturated ammonium sulfate solution (80 %), and ultra-filtration through 10 kDa membranes were tested (

Table 1). The concentration achieved by the chemical methods using ammonium sulfate and acetone resulted in a significant reduction of the specific enzymatic activity (53.57 %), approximately 10 times lower than that obtained in the unconcentrated crude enzymatic extract (31.63 U/mg), respectively. This is probably because the concentration reached with these chemical agents can destabilize the ionic charges of the enzyme, changing the polarity of the solution and thus altering the stability of the enzyme, leading to instability, decreased activity, or even denaturation. Although the ammonium sulfate solution increased the total protein (9.00 mg), the total activity of the enzyme decreased (127.05 U), indicating that this method does not have a high purification rate, despite a good recovery. Similar results were verified by Gul-Guven [

45] and Heidtmann [

46], where the enzyme concentration obtained using 50 % and 70 % ammonium sulfate solutions led to a decrease in the specific enzymatic activity of β-galactosidase (45.4 % and 16.8 %, respectively).

Concentration by membrane ultrafiltration (10 kDa) showed a more than 6-fold increase in total enzyme activity (1640.80 U), but an approximately 3-fold decrease in specific activity (8.66 U/mg). As the crude enzyme extract is composed of several other uninteresting enzymes, it is possible that high molecular weight proteins were retained by the 10 kDa membrane. This hypothesis was confirmed by SDS gel (data not shown) by comparing the molecular weight of the proteins in the crude enzyme extract within the sample containing the concentrated enzyme extract and the sample purified by cation exchange chromatography in comparison to the commercial enzyme (Maxilact LGi 5000). In addition, the presence of a band in the 150 kDa region was observed for the crude and commercial enzyme samples. According to the literature, β-galactosidase from

Kluyveromyces sp. strains have a molecular weight ranging from 120 kDa to 200 kDa [

47,

48,

49]. Considering that the immobilization processes require enzymes with high enzymatic activities and low interference, the present study also adopted the strategy of concentrating the cell suspension (6 times) before its disruption (

Table 1), resulting in a 56.6 % increase in enzymatic activity (69.24 U/mL) and total enzymatic activity (517.90 U) in comparison with the crude enzymatic extract. In addition, a high specific enzymatic activity (10.90 U/mg) was found compared to that concentrated by membrane (10 kDa). The cell suspension concentration approach not only represents a reduction in the number of operations in the process, but also generating lower waste amount when compared to the chemical methods tested.

3.2. Optimal pH and Temperature of β-Galactosidase Activity

The activity of free and immobilized β-galactosidase on different support materials was determined at temperatures ranging from 20 oC to 60 oC and at pH levels ranging from 5.7 to 8.0 for both the enzyme produced in this work and the commercial one. The immobilization yield was determined for both supports, being 64.24% for chitosan-genipin and 72.47 % for alginate, nevertheless, the highest immobilization efficiency was for chitosan-genipin support (55.68%), being almost 32% times higher as alginate (37.99%). The pH variation tests (Fig. 3A) for the produced enzyme demonstrated that both the free enzyme and its immobilized form on chitosan support exhibited optimal activity at pH 6.5. Conversely, immobilization on calcium alginate extended the range, with optimal activity at pH 7.0. Furthermore, the relative enzyme activity at pH 6.0 was 73.94 % and 61.6 % for the chitosan-genipin and calcium alginate supports, respectively. However, at pH 7.0, the values were 70.65 % and 100 %, respectively, for the chitosan-genipin and alginate supports. These results suggest that the chitosan-genipin support provided greater stability at a slightly more acidic pH, while the alginate showed greater relative activity at a slightly more basic pH.

The optimal temperature (

Figure 3B) for the free enzyme (11.23 U/mL) was found to be 37 °C. It was observed that immobilization in alginate extended the thermal stability range up to 40 °C, with a relative activity of 98.62 %, whereas the immobilization in the chitosan-genipin support resulted in an increased thermal stability range (37 °C-45 °C), maintaining the relative activity between 95.8 % and 100 %. This confirms the advantages of the immobilization system and the increased thermal stability of it [

16]. Another advantage of this technique is that it allows for the reuse of the enzyme in the reaction medium, enabling the use of a continuous process [

15,

16]. Bolognesi [

39] reported that immobilization with calcium alginate increased the optimal pH range of

K. lactis β-galactosidase. Hackenhaar [

19] observed that the immobilization process using genipin as a crosslinker and used in the optimal pH range, noted an increase in the optimal temperature range of the immobilized enzyme when compared to the free enzyme. Similarly, Klein [

50] observed a shift in the optimal pH range of immobilized

A. oryzae β-galactosidase to more acidic values when using chitosan-genipin supports. However, the authors did not detect any changes in the optimal temperature compared to the free enzyme. Among the advantages of immobilization are the expansion of the activity range at different pHs and increased thermal stability, which allows for improved operational stability and the reuse of the biocatalyst [

16,

17,

39].

3.3. GOS Production in Shaker

The production of GOS using the crude β-galactosidase extract was performed with the analysis of three different process variables: temperature (37 °C-43 °C), enzyme concentration (50 U/mL-150 U/mL), and Porungo cheese whey concentration (200 g/L-400 g/L). The highest GOS production was observed at a temperature of 40 °C, with 23.91 g/L of GOS3 obtained in 6 h of reaction, reaching a maximum yield of 9.21 % and lactose conversion of 55.58 % (

Figure 4A,B). These values are 15.7 % and 37.3 % higher than those obtained at 37 °C (7.96 % and 40.47 %), and slightly higher than those obtained at 43 °C (8.63 % and 53.21 %), respectively. Higher temperatures favor the transgalactosylation reaction over the hydrolysis reaction. Following these observations, it can be inferred that the lower GOS production at 37 °C (19.97 g/L) in comparison to that obtained at 40 °C is not due to enzyme stability issues, but rather to the negative effect observed at lower temperatures on the transgalactosylation reaction. Thus, the best temperature for GOS production should not be as high to reduce enzyme activity, but not as low to render the transgalactosylation process ineffective. Similar results were reported by González-Delgado [

51], when testing the influence of temperature on GOS production (40 °C to 60 °C), verifying that temperatures above 40 °C impaired the production of these biomolecules, causing the thermal denaturation of β-galactosidase from

K. lactis (Lactozym Pure 6500), with best yields (12.18 %) achieved for lactose solution (250 g/L) at 40 °C. Srivastava [

52] investigated GOS synthesis (200 g/L lactose, 40 ºC) by permeabilizing yeasts of the

K. marxianus and

K. lactis species, reaching a maximum yield of 36 % for the first strain tested. The authors also reported inactivation of the enzyme at 60 ºC.

The Tukey test showed statistical differences (p<0.05) between enzyme concentration of 100 U/mL and the other two concentrations, 50 U/mL and 150 U/mL, but not between these last two for GOS yield and lactose conversion. The influence of enzyme concentration on GOS production can be seen in

Figure 4C. The highest GOS yields (15.24 %) and lactose conversions (50.34 %) were achieved at the 100 U/mL concentration, while the lowest values of these kinetic parameters were obtained at the 50 U/mL concentration (10.22 % and 21.41 %), respectively. For the enzymatic concentration of 150 U/mL, intermediate values of yield and conversion were reached (12.57 % and 32.66 %), indicating a possible limitation in the mass transfer on the surface of the most enzyme-loaded matrix (150 U/mL), thus hindering the access to the substrate and impairing the efficiency of the process. González-Delgado [

51] analyzed GOS synthesis from the

K. lactis β-galactosidase (250 g/L lactose, 40 °C, pH 7.0) at different enzymatic concentrations (2 U/mL - 20 U/mL), finding the highest yield (12.5 %) at the 5 U/mL concentration, suggesting that higher concentrations of enzyme tend to increase the hydrolysis over that of transgalactosylation. Conversely, González-Cataño [

53] evaluated the impact of the concentration of

K. lactis β-galactosidase immobilized in polysiloxane-polyvinyl alcohol (POS-PVA) (3 U/mL to 6 U/mL) on GOS production in batch reactors with stirred tanks (270 g/L, 40 ºC), obtaining a maximum GOS concentration (25.46 g/L) for the highest enzymatic concentration tested.

Regarding the influence of substrate concentration on GOS production (

Figure 4D), the highest GOS yield (15.24%) and lactose conversion (50.34%) were observed at the intermediate concentration (300 g/L), resulting at a GOS production of 26.5 g/L within a four-hour reaction period. The higher substrate concentration (400 g/L) resulted in lower GOS yields (12.99%) and conversion values (47.16%) when compared to those obtained at the intermediate substrate concentration. Thus, even when a higher concentration (32.8 g/L) was obtained, the presence of a considerable amount of unconverted lactose resulted in lower yields. High lactose concentrations generally favor the transgalactosylation process due to the excess of hydroxylated galactose compounds (GOS), which bind to the galactose resulting from hydrolysis, as well as the decreased percentage of water molecules available to accept galactose residues [

17,

39,

54]. Very high concentrations of lactose, such as 400 g/L, can reduce the efficiency of the process due to the competitive inhibition of galactose on enzymatic activity [

55]. The results suggest that low substrate concentrations of 200 g/L produced reduced yields (8.35%) and lactose conversion with a high conversion rate (64.32%), which can be attributed to the conversion of not only GOS through transgalactosylation, but also the formation of undesirable by-products, such as glucose (54.25 g/L) and galactose (35.33 g/L), probably due to the concomitant hydrolysis reaction, given the greater presence of water in this solution. The Tukey test showed statistical differences (p<0.05) between the substrate concentration of 200 g/L and the other two evaluated, 300 g/L and 400 g/L, but not between the last two for GOS yield and lactose conversion.

Similar results were observed by Martínez-Villaluenga [

56], who reported that GOS yields went from 14.8 % to 17.1 % when increasing the lactose solution concentration from 150 g/L to 250 g/L using

K. lactis β-galactosidase (40 °C and pH 7.5). Likewise, González-Delgado [

51] and Zhang [

57] obtained the highest GOS yields (11.6 % to 15.9 % and 20.54 % to 30.63 %), respectively, when increasing the lactose concentration (50 g/L to 250 g/L and 200 g/L to 400 g/L), using

A. aculeatus β-galactosidase (60 °C and pH 6.5) and

Lactobacillus plantarum β-galactosidase (35 °C and pH 7.0). Hackenhaar [

19] showed the effect of lactose concentration in cheese whey and whey permeate (30 % and 40 %, pH 7.0, 50 ºC), and obtained the highest concentration of GOS for the highest lactose concentration of both substrates (159.4 g/L and 168.8 g/L), with yields of 40 % and 42 %, respectively.

3.4. GOS Production in Batch and Repeated Batch Bioreactors

Figure 5A presents the kinetic profile of the conversion of lactose to GOS in a packed-bed column bioreactor in batch mode. It is possible to observe that the GOS concentration reached the maximum (20.45 g/L) in 2 h of reaction, with 68.35 % of consumption of the initial substrate. In addition, a maximum GOS yield of 19.72% and productivity of 10.22 g/L.h were achieved, being 62.49% higher than that obtained with the shaker (6.29 g/L.h). Comparing the results of batch bioreactors for GOS yield and lactose conversion with those obtained shaker, under the same process conditions, higher values of these parameters were obtained (29.39 % and 33.11 %, respectively). There is a substantial increase in the surface contact area between immobilized enzyme-substrate, improving process performances [

23]. The packed-bed reactor allows the concentration gradient along the height of the reactor column, providing more efficient enzymatic reaction at the beginning of the process, and thus, enabling higher yields. González-Cataño [

53], obtained yield values of 25.46 % for GOS production in a stirred tank reactor (270 g/L lactose, 40 °C and pH 7.1) using

K. lactis β-galactosidase covalently immobilized to polysiloxane-polyvinyl alcohol (POS-PVA) activated with glutaraldehyde. Misson [

58], reported GOS yields and lactose conversion (41 % and 88 %, respectively) in a disk stack column reactor using

K. lactis β-galactosidase immobilized on chemically modified electrospun polystyrene nanofibers (PSNF) under the conditions of lactose 300 g/L, 40 ºC, pH 7.2.

The kinetics of obtaining GOS from Porungo cheese whey conducted in repeated batch bioreactors (

Figure 5B and 5C) shows that β-galactosidase kept its activity at 83.56 % for up to 5 cycles of reuse (

Figure 5A), indicating the operational stability of the process. Additionally, a slight increase over the first cycles was observed about the substrate consumption (73.46 % to 89.13 %) and GOS yield (19.22 % to 20.44 %), remaining constant until the fifth cycle (

Figure 5C). This means that enzymatic immobilization allows not only the efficient reuse of the biocatalyst but also the operational stability of the process, hence allowing the reduction of costs associated with the process [

31]. From the sixth cycle onwards, there was a drastic loss of operational stability of the system, and this may be due to the enzyme washout, causing the system to destabilize and to a drastic reduction in yield. Hackenhaar [

19] obtained stable GOS production systems for up to 10 cycles, in which 74 % of initial enzymatic activity and 40 % GOS yield were observed, using an orbital shaker (whey permeate at 554 g/L, 50 ºC, pH 7.0) with β-galactosidase (

Bacillus circulans) immobilized on chitosan beads. Urrutia [

59], also obtained stable GOS production systems for up to 10 cycles, and observed a GOS yield of 28.8 % (lactose solution of 50 %, pH 4.5, 60 ºC) using β-galactosidase (

Aspergillus oryzae) immobilized on chitosan beads. Liu [

60] studied

K. fragilis β-galactosidase immobilized on magnetic nanospheres with polyethylenimine for GOS production (20 % lactose solution, 30 °C, pH 6.5), achieving 31.0 % yield, with the enzyme keeping 84.6 % of its initial activity after 15 cycles. Lu [

61] immobilized β-galactosidase expressed by

E. coli (with the cloned

Lactobacillus bulgaricus L3 gene) to synthesize GOS (400 g/L lactose, 45 °C, pH 7.6), obtaining a high yield of 49 %. After 20 cycles, the GOS yields remained at 40 %, showing the efficiency of the system.

3.5. GOS Production in Continuous Bioreactor

Continuously operated packed-bed bioreactors were tested under three different volumetric flow rates of fresh medium. The Tukey test showed statistical differences on GOS yields (p<0.05) between the 1 mL/h flow rate compared with 2 mL/h and 3 mL/h, but not between the latter two. For lactose conversion, all flow rates tested differed from each other. As shown in

Figure 6A and 6B, system stabilization was observed for the flow rates of 1 mL/h and 2 mL/h, indicating that a steady state was achieved. The highest yield values of 24.63% and productivity of 5.87 g/L.h were obtained for the lowest flow rate tested, reaching GOS concentration of 44.14 g/L (

Table 2). The kinetic parameters were optimal at the lowest feed flow rate as well. This may be attributed to the longer residence time, which allows the substrate to be available for the reaction for a longer period in the bioreactor column. At flow rate of 1 mL/h, a yield 28.44 % higher than that obtained at the flow rate of 2 mL/h (19.18%), and approximately three times higher than that obtained at the flow rate of 3 mL/h (8.35%) was observed. Significant increases in lactose conversion (80 % and 4-fold increase) and volumetric productivity (approximately 2 and 6-fold increase) were observed when compared to those obtained at 2 mL/h and 3 mL/h flow rates, respectively. The behavior observed for the tests at the highest flow rate (3 mL/h) suggests the possibility of a system washout (

Figure 6A and 6B), as evidenced by the significant increase in lactose concentration, reaching 85.27 % of the initial substrate concentration. This result can be explained by the short residence time of the substrate inside the bioreactor, limiting its optimized conversion into a product.

These results were consistent with those reported by Hackenhaar [

62], who used immobilized

A. oryzae galactosidase in chitosan activated with glutaraldehyde in a packed-bed reactor (40 °C, 300 g/L lactose solution), varying the substrate feed rate from 0.44 mL/min to 2.2 mL/min, and obtained a total maximum GOS production of 71.2 g/L at the lowest flow rate tested (0.44 mL/min), corresponding to a GOS yield of 23.7 %, which decreased considerably (38.7 g/L) at higher feed rates. The authors observed a conversion of lactose that was 1.7 times lower (39.7 %) than that observed in the present study. In contrast, Klein [

17] employed immobilized

K. lactis galactosidase in glutaraldehyde-activated chitosan with a packed-bed reactor operated continuously at varying flow rates (1 mL/min to 15 mL/min), resulting in the lowest yield (6.5 %) and lactose conversion (58 %) for the lowest flow rates tested (3.1 mL/min). The authors suggested that the lower synthesis of GOS was due to the hydrolysis of the synthesized GOS, since longer residence times could lead to the subsequent hydrolysis by the enzyme.

Figure 6C depicts the kinetic parameters obtained in the different systems studied in this work. It can be inferred that the continuous system in the GOS production process achieved better parameters when compared to the other processes tested, increasing the yield in relation to the batch bioreactor by 24.90 %, and 61.61 % compared to the production using the shaker. Lactose conversion was slightly higher (2.04 %) with the continuous bioreactor than with the batch bioreactor, and 35.84 % higher when compared to shaker tests. In contrast, the continuous bioreactor productivity was 6.68 % and 45.56 % lower than that obtained with the shaker and batch systems, respectively. Nevertheless, the GOS production reached maximum levels (41.06 g/L) when using the continuous system, compared to batch mode (20.45 g/L). Results here suggest the use of the continuous bioreactor, demonstrating its application in more efficient and optimized processes.

3.6. GOS as a Potential Prebiotic

The

Lactococcus QP40,

Streptococcus QP32 and

L. lactis ATCC 19435 bacteria were grown in different culture media, one with GOS (MRS + GOS) and a control without GOS (MRS), to verify the prebiotic potential of the oligosaccharides produced. These microorganisms are cited in the literature as probiotics [

63,

64,

65]. The

Lactococcus QP40 and

Streptococcus QP32 strains (

Figure 7) showed quite similar behavior, both in the ability to metabolize the total substrate (glucose and galactose) in the MRS medium (46.26 % and 48.47 %) and in the MRS medium combined with GOS (45.24 % and 41.13 %), respectively.

Although these two strains showed greater metabolism of total substrates when compared to the commercial strain L. lactis ATCC 19435, it showed a better substrate consumption when GOS was added to the MRS culture medium, in this case, the aforementioned strain metabolized 20.88 % of total substrate compared to 14.04 % in MRS medium (without GOS). This indicates that the presence of GOS improved the metabolism of other carbon sources for this strain. Therefore, L. lactis ATCC 19435 metabolized 10.94% of the GOS, while Lactococcus QP40 and Streptococcus QP32 metabolized, respectively, 9.87% and 9.41%. Nevertheless, this stage of the work is still preliminary, these previous results may serve as a basis for future studies on the prebiotic potential of GOS and probiotics related to the strains tested here.

4. Conclusions

The Porungo cheese whey demonstrated to be a promising substrate to obtain GOS from β-galactosidase produced, especially when associated with enzyme immobilization technology and different bioprocess strategies. The supports of chitosan-genipin increased thermal stability range of β-galactosidase allowing its reuse at a higher temperature. Batch packed-bed bioreactor significantly increased the productivity compared to the shaker system. Continuous bioreactor improved the lactose conversion, GOS yield, and GOS concentration compared to shaker and batch bioreactor, leading to a more efficient GOS production and optimized processes. This study contributes to the minimization of the environmental impact caused by the main waste generated in the dairy industry, while obtaining a biotechnological product with high added value and significant international commercial relevance, targeting the application in the food sector, as well as in the pharmaceutical and agricultural industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sabrina Gabardo; Methodology, Thaís Cavalcante Torres Gama, Guilherme Fermino de Oliveira, Natan de Jesus Pimentel-Filho, Marcelo Perencin de Arruda Ribeiro, Marco Antônio Záchia Ayub and Sabrina Gabardo; Validation, Thaís Cavalcante Torres Gama, Guilherme Fermino de Oliveira and Sabrina Gabardo; Investigation, Thaís Cavalcante Torres Gama and Guilherme Fermino de Oliveira; Resources, Marco Antônio Záchia Ayub and Sabrina Gabardo; Data curation, Thaís Cavalcante Torres Gama and Guilherme Fermino de Oliveira; Writing – original draft, Thaís Cavalcante Torres Gama and Guilherme Fermino de Oliveira; Writing – review & editing, Natan de Jesus Pimentel-Filho, Marcelo Perencin de Arruda Ribeiro, Marco Antônio Záchia Ayub and Sabrina Gabardo; Visualization, Sabrina Gabardo; Supervision, Sabrina Gabardo; Project administration, Sabrina Gabardo; Funding acquisition, Marco Antônio Záchia Ayub and Sabrina Gabardo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, grant number 2021/06313-7; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, grant number 405418/2021-3.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grant #2021/06313-7) and CNPq (405418/2021-3), Brazil, for the financial support of this research and scholarships for the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Centesimal composition of Porungo cheese whey.

Table A1.

Centesimal composition of Porungo cheese whey.

| Component |

% |

| Moisture |

92.30 ± 0.29 |

| Dry extract |

7.70 ± 0.35 |

| Lipids |

0.30 ± 0.03 |

| Protein |

0.81 ± 0.01 |

| Lactose |

4.99 ± 0.06 |

| Ash |

0.55 ± 0.01 |

Appendix A.2

Figure A2.

Kinetics of K.marxianus CCT 4086 (A) growing in porungo cheese whey at 30 ºC and 200 rpm. Lactose (-●-), Biomass (-◼-), Enzymatic activity (-∗-).

Figure A2.

Kinetics of K.marxianus CCT 4086 (A) growing in porungo cheese whey at 30 ºC and 200 rpm. Lactose (-●-), Biomass (-◼-), Enzymatic activity (-∗-).

References

- Davani-Davari, D.; Negahdaripour, M.; Karimzadeh, I.; Seifan, M.; Mohkam, M.; Masoumi, S.J.; Berenjian, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Prebiotics: Definition, Types, Sources, Mechanisms, and Clinical Applications. Foods 2019, 8, 92. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.E.; Merenstein, D.J.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Intestinal Health and Disease: From Biology to the Clinic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 605–616. [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.F.C.E.; Gabardo, S.; Coelho, R.D.J.S. Galactooligosaccharides: Physiological Benefits, Production Strategies, and Industrial Application. J. Biotechnol. 2022, 359, 116–129. [CrossRef]

- Farias, D.D.P.; De Araújo, F.F.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Prebiotics: Trends in Food, Health and Technological Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 23–35. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, G.R.; Scott, K.P.; Rastall, R.A.; Tuohy, K.M.; Hotchkiss, A.; Dubert-Ferrandon, A.; Gareau, M.; Murphy, E.F.; Saulnier, D.; Loh, G.; Macfarlane, S.; Delzenne, N.; Ringel, Y.; Kozianowski, G.; Dickmann, R.; Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I.; Walker, C.; Buddington, R. Dietary Prebiotics: Current Status and New Definition. Food Sci. Technol. Bull. 2010, 7, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Sako, T.; Tanaka, R. Prebiotics Types. Food Sci. 2011, 354–364. [CrossRef]

- Gosling, A.; Stevens, G.W.; Barber, A.R.; Kentish, S.E.; Gras, S.L. Effect of the Substrate Concentration and Water Activity on the Yield and Rate of the Transfer Reaction of β-Galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3366–3372. [CrossRef]

- Gosling, A.; Stevens, G.W.; Barber, A.R.; Kentish, S.E.; Gras, S.L. Recent Advances Refining Galactooligosaccharide Production from Lactose. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 307–318. [CrossRef]

- Torres, D.P.M.; Gonçalves, M.D.P.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Rodrigues, L.R. Galacto-Oligosaccharides: Production, Properties, Applications, and Significance as Prebiotics. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2010, 9, 438–454. [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Bhattacharjee, C.; Chowdhury, R. Synthesis and Separation of Galacto-Oligosaccharides Using Membrane Bioreactor. Desalination 2013, 316, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Sangwan, V.; Tomar, S.K.; Ali, B.; Singh, R.R.; Singh, R.R.B.; Singh, A.K.; Mandal, S. Galactooligosaccharides Purification Using Microbial Fermentation and Assessment of Its Prebiotic Potential by In Vitro Method. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 573–585.

- Lamsal, B.P. Production, Health Aspects and Potential Food Uses of Dairy Prebiotic Galactooligosaccharides. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2020–2028. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante Fai, A.E.; Pastore, G.M. Galactooligosaccharides: Production, Health Benefits, Application to Foods and Perspectives. Sci. Agropecu. 2015, 6, 69–81. [CrossRef]

- Vera, C.; Córdova, A.; Aburto, C.; Guerrero, C.; Suárez, S.; Illanes, A. Synthesis and Purification of Galacto-Oligosaccharides: State of the Art. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 197. [CrossRef]

- Kosseva, M.R.; Panesar, P.S.; Kaur, G.; Kennedy, J.F. Use of Immobilised Biocatalysts in the Processing of Cheese Whey. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2009, 45, 437–447. [CrossRef]

- Panesar, P.S.; Kumari, S.; Panesar, R. Potential Applications of Immobilized β-Galactosidase in Food Processing Industries. Enzyme Res. 2010, 473137. [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.P.; Fallavena, L.P.; Schöffer, J.D.N.; Ayub, M.A.Z.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Ninow, J.L.; Hertz, P.F. High Stability of Immobilized β-D-Galactosidase for Lactose Hydrolysis and Galactooligosaccharides Synthesis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 465–470. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Duan, K.-J. Production of Galactooligosaccharides Using β-Galactosidase Immobilized on Chitosan-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12499–12512. [CrossRef]

- Hackenhaar, C.R.; Spolidoro, L.S.; Flores, E.E.E.; Klein, M.P.; Hertz, P.F. Batch Synthesis of Galactooligosaccharides from Co-Products of Milk Processing Using Immobilized β-Galactosidase from Bacillus circulans. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 36, 102136. [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, B. Application of Chitin- and Chitosan-Based Materials for Enzyme Immobilizations: A Review. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2004, 35, 126–139. [CrossRef]

- Grosová, Z.; Rosenberg, M.; Rebroš, M. Perspectives and Applications of Immobilised β-Galactosidase in Food Industry—A Review. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, S.; Rech, R.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Performance of Different Immobilized-Cell Systems to Efficiently Produce Ethanol from Whey. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 87, 1194–1201. [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, S.; Rech, R.; Rosa, C.A.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Dynamics of Ethanol Production from Whey and Whey Permeate by Immobilized Strains of Kluyveromyces marxianus. Renew. Energy 2014, 69, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, S.; Pereira, G.F.; Rech, R.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Modeling of Ethanol Production by Kluyveromyces marxianus Using Whey as Substrate. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 42, 1243–1253. [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Raychaudhuri, A.; Ghosh, S.K. Supply Chain of Bioethanol Production from Whey: A Review. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 833–846. [CrossRef]

- Haider, T.; Husain, Q. Calcium Alginate Entrapped Preparations of Aspergillus oryzae β-Galactosidase. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 41, 72–80. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.F.; Marquez, L.D.S.; Ribeiro, G.P.; Brandão, G.C.; Cardoso, V.L.; Ribeiro, E.J. Comparison of Kinetic Properties of Free and Immobilized Aspergillus oryzae β-Galactosidase. Biochem. Eng. J. 2011, 58, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, P.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A.; Domingues, L. Fermentation of Lactose to Bio-Ethanol by Yeasts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2010, 28, 375–384. [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, D.; Suwal, S.; Ray, C.; Tiwari, B.K.; Jensen, P.E.; Poojary, M.M. Valorization of Dairy Side-Streams for the Cultivation of Microalgae. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 146, 104386. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.D.; Kádár, Z.; Oleskowicz-Popiel, P.; Thomsen, M.H. Production of Bioethanol from Organic Whey Using Kluyveromyces marxianus. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 283–289. [CrossRef]

- Gabardo, S.; Pereira, G.F.; Klein, M.P.; Rech, R.; Hertz, P.F.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Dynamics of Yeast Immobilized-Cell Fluidized-Bed Bioreactors. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Trindade, M.B.; Soares, B.C.V.; Scudino, H.; Guimarães, J.T.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q.; Pimentel, T.C.; Silva, M.C.; Souza, S.L.Q.; Almada, R.B.; Cruz, A.G. Cheese Whey Exploitation in Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 788–791. [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.F.; Marnotes, N.G.; Rubio, O.D.; Garcia, A.C.; Pereira, C.D. Dairy By-Products: Valorization of Whey. Foods 2021, 10, 1067. [CrossRef]

- Rech, R.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Simplified Feeding Strategies for Fed-Batch Cultivation of Kluyveromyces marxianus. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 873–877. [CrossRef]

- Coelho, R.J.S.; Gabardo, S.; Marim, A.V.C.; Bolognesi, L.S.; Pimentel Filho, N.J.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Porungo Cheese Whey: A New Substrate to Produce β-Galactosidase. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2023, 95, e20200483. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, F.O.D.; Alves, F.G.; Lisboa, C.R.; Martins, D.D.S.; Burkert, C.A.V.; Kalil, S.J. Ultrasonic Waves and Glass Beads: A New β-Galactosidase Extraction Method. Quim. Nova 2008, 31, 336–339. [CrossRef]

- Lima, M.D.A.; Freitas, M.D.F.M.D.; Gonçalves, L.R.B.; Silva Junior, I.J.D. Recovery and Purification of Kluyveromyces lactis β-Galactosidase. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1015–1016, 181–191. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, G.; Cao, L.; Ren, G.; Kong, W.; Wang, S.; Guo, G.; Liu, Y.-H. Characterization of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates of β-Galactosidase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 894–901. [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, L.S.; Gabardo, S.; Dall Cortivo, P.R.; Ayub, M.A.Z. Biotechnological Production of Galactooligosaccharides Using Porungo Cheese Whey. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 42, e64520. [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.P.; Nunes, M.R.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Benvenutti, E.V.; Costa, T.M.H.; Hertz, P.F.; Ninow, J.L. Effect of Support Size on β-Galactosidase Immobilization on Chitosan. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2456–2464. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Dagbagli, S.; Goksungur, Y. Optimization of β-Galactosidase Production Using Kluyveromyces lactis. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 11, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Numanoğlu, Y.; Sungur, S. β-Galactosidase from Kluyveromyces lactis: Cell Disruption and Immobilization. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 705–711. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.C.D.; Gonçalves, G.T.I.; Falleiros, L.N.S.S. Ethanol Production Using Agroindustrial Residues by Kluyveromyces marxianus. Ind. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 308–314. [CrossRef]

- Gul-Guven, R.; Guven, K.; Poli, A.; Nicolaus, B. Purification and Properties of a β-Galactosidase from Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 1570–1577. [CrossRef]

- Heidtmann, R.B.; Duarte, S.H.; Pereira, L.P.D.; Braga, A.R.C.; Kalil, S.J. Kinetic and Thermodynamic Characterization of β-Galactosidase from Kluyveromyces marxianus. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2012, 15, 41–49. [CrossRef]

- Galinari, É.; Sabry, D.A.; Sassaki, G.L.; Macedo, G.R.; Passos, F.M.L.; Mantovani, H.C.; Rocha, H.A.O. Chemical Structure and Antioxidant Activities of Yeast Mannan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1298–1305. [CrossRef]

- Gékas, V.; Lopez-Leiva, M. Hydrolysis of Lactose: A Literature Review. Process Biochem. 1985, 20, 2–12.

- Cavaille, D.; Combes, D. Characterization of β-Galactosidase from Kluyveromyces lactis. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 1995, 22, 55–64.

- Klein, M.P.; Hackenhaar, C.R.; Lorenzoni, A.S.G.; Rodrigues, R.C.; Costa, T.M.H.; Ninow, J.L.; Hertz, P.F. Chitosan Crosslinked with Genipin as Support Matrix. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 184–190. [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, I.; López-Muñoz, M.-J.; Morales, G.; Segura, Y. Optimisation of High GOS Synthesis from Lactose. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 61, 211–219. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Mishra, S.; Chand, S. Transgalactosylation of Lactose Using Kluyveromyces marxianus. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 412–418. [CrossRef]

- González-Cataño, F.; Tovar-Castro, L.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Regalado-Gonzalez, C.; García-Almendarez, B.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Amaya-Llano, S. Improvement of Covalent Immobilization of β-Galactosidase. Biotechnol. Prog. 2017, 33, 1568–1578. [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, C.R.; Costa, F.A.D.A.; Burkert, J.F.D.M.; Burkert, C.A.V. Synthesis of Galactooligosaccharides Using Commercial β-Galactosidase. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2012, 15, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, K.D.; Polizelli, M.A. Determination of Kinetic Parameters of β-Galactosidase. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 28194–28208. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Corzo, N.; Olano, A.; Villamiel, M. Optimization of Galactooligosaccharide Synthesis Conditions. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 258–264. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, C.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, B. Production of High-Purity Galactooligosaccharides by Lactobacillus-Derived β-Galactosidase. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1501–1510. [CrossRef]

- Misson, M.; Jin, B.; Dai, S.; Zhang, H. Interfacial Biocatalytic Performance of Nanofiber-Supported β-Galactosidase. Catalysts 2020, 10, 81. [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, P.; Bernal, C.; Wilson, L.; Illanes, A. Use of Chitosan Heterofunctionality for Enzyme Immobilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 182–193. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-F.; Liu, H.; Tan, B.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yang, R.-J. Reversible Immobilization of β-Galactosidase onto Magnetic Nanospheres. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2012, 82, 64–70. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Xu, S.; Zhao, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiao, M. Synthesis of Galactooligosaccharides by CBD Fusion β-Galactosidase. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 116, 327–333. [CrossRef]

- Hackenhaar, C.R.; Klein, M.P. Obtenção de Galactooligossacarídeos Utilizando β-Galactosidase Imobilizada. Feira de Inovação Tecnológica, UFRGS, Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2013.

- Song, A.A.-L.; In, L.L.A.; Lim, S.H.E.; Rahim, R.A. A Review on Lactococcus lactis: From Food to Factory. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 55. [CrossRef]

- Higdon, S.M.; Huang, B.C.; Bennett, A.B.; Weimer, B.C. Identification of Nitrogen Fixation Genes in Lactococcus. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2043. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.; Tromps, J. Caracterização In Vitro de Ácido Láctico Bacteriano com Potencial Probiótico. Rev. Salud Anim. 2014, 36, 124–129.

Figure 1.

General scheme and strategy of the proposal used in this study for the GOS production. 1) Porungo cheese whey obtained in cheese production process; 2) Production of β-galactosidase by K. marxianus CCT 4086; 3) Downstream stage: extraction, concentration and partial purification of the enzyme; 4) Immobilization and characterization of the β-galactosidase produced; 5) Use of the concentrated β-galactosidase for GOS production by different bioprocess strategies (shaker and bioreactor); and, 6) GOS prebiotic potential by microorganisms isolated from Porungo cheese.

Figure 1.

General scheme and strategy of the proposal used in this study for the GOS production. 1) Porungo cheese whey obtained in cheese production process; 2) Production of β-galactosidase by K. marxianus CCT 4086; 3) Downstream stage: extraction, concentration and partial purification of the enzyme; 4) Immobilization and characterization of the β-galactosidase produced; 5) Use of the concentrated β-galactosidase for GOS production by different bioprocess strategies (shaker and bioreactor); and, 6) GOS prebiotic potential by microorganisms isolated from Porungo cheese.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the experimental apparatus for the continuous GOS production process using a packed-bed column bioreactor containing the enzyme immobilized in genipin-chitosan spheres.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the experimental apparatus for the continuous GOS production process using a packed-bed column bioreactor containing the enzyme immobilized in genipin-chitosan spheres.

Figure 3.

Effect of the pH (A) and temperature (B) on the activity of β-galactosidase produced by K. marxianus CCT 4086. β-galactosidase free activity (●), immobilized on alginate (◼), and on chitosan-genipin (▲).

Figure 3.

Effect of the pH (A) and temperature (B) on the activity of β-galactosidase produced by K. marxianus CCT 4086. β-galactosidase free activity (●), immobilized on alginate (◼), and on chitosan-genipin (▲).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of lactose consumption (A) and GOS production (B) at different temperatures, and the influence of the immobilized enzyme concentration (C) and Porungo cheese whey concentration (D) on GOS yield and lactose conversion, in shaker at 150 rpm for 6h of reaction. Temperature of 37 ºC (◼), 40 ºC (●), 43 ºC (▲), Yield (

) and Conversion (

).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of lactose consumption (A) and GOS production (B) at different temperatures, and the influence of the immobilized enzyme concentration (C) and Porungo cheese whey concentration (D) on GOS yield and lactose conversion, in shaker at 150 rpm for 6h of reaction. Temperature of 37 ºC (◼), 40 ºC (●), 43 ºC (▲), Yield (

) and Conversion (

).

Figure 5.

Kinetics of GOS production from Porungo cheese whey in a batch packed-bed bioreactor system (A), the relative β-galactosidase activity (B) and the kinetic profile of GOS production (C) in repeated-batch bioreactor for 7 consecutive cycles of 4h each, at 40 °C, using Porungo cheese whey (300 g/L). Lactose concentration (■), glucose (●), galactose (▲) and GOS (*).

Figure 5.

Kinetics of GOS production from Porungo cheese whey in a batch packed-bed bioreactor system (A), the relative β-galactosidase activity (B) and the kinetic profile of GOS production (C) in repeated-batch bioreactor for 7 consecutive cycles of 4h each, at 40 °C, using Porungo cheese whey (300 g/L). Lactose concentration (■), glucose (●), galactose (▲) and GOS (*).

Figure 6.

Profile of lactose concentration (A) and GOS production (B) in a continuously operated packed-bed column bioreactor, at 40 ºC, from Porungo cheese whey (300 g/L) using β-galactosidase immobilized on chitosan-genipin as biocatalyst for three different feed rates: 1 mL/h; 2mL/h and 3 mL/h, and the comparison (C) between GOS yield, lactose conversion, productivity and maximum GOS concentration conducted in different bioprocess systems. GOS yield (●), lactose conversion (◼), productivity, Qp (▲), and GOS concentration (*).

Figure 6.

Profile of lactose concentration (A) and GOS production (B) in a continuously operated packed-bed column bioreactor, at 40 ºC, from Porungo cheese whey (300 g/L) using β-galactosidase immobilized on chitosan-genipin as biocatalyst for three different feed rates: 1 mL/h; 2mL/h and 3 mL/h, and the comparison (C) between GOS yield, lactose conversion, productivity and maximum GOS concentration conducted in different bioprocess systems. GOS yield (●), lactose conversion (◼), productivity, Qp (▲), and GOS concentration (*).

Figure 7.

Percentage of the consumption profile of the total substrate and GOS for the different bacteria grown at 37 ºC, 50 rpm. MRS medium (

), MRS medium combined with GOS (

), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS (

).

Figure 7.

Percentage of the consumption profile of the total substrate and GOS for the different bacteria grown at 37 ºC, 50 rpm. MRS medium (

), MRS medium combined with GOS (

), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS (

).

Table 1.

Total enzyme activity, total protein, and specific activity of β-galactosidase obtained from K. marxianus CCT 4086 using different strategies of cell disruption and of the enzyme concentration. .

Table 1.

Total enzyme activity, total protein, and specific activity of β-galactosidase obtained from K. marxianus CCT 4086 using different strategies of cell disruption and of the enzyme concentration. .

| Cell Disruption Method |

Total Enzyme Activity (U) |

Total Protein (mg) |

Specific Activity (U/mg) |

| Vortex shaker cell lysis |

17.33 ± 0.42 |

0.49 ± 0.05 |

38.91 ± 2.60 |

| Chloroform autolysis |

17.35 ± 1.89 |

0.40 ± 0.08 |

44.21 ± 3.64 |

| Enzyme Concentration Approaches |

| Crude extract |

237.2 ± 0.59 |

7.50 ± 0.19 |

31.63 ± 3.49 |

| 75% Acetone |

9.00 ± 0.03 |

2.70 ± 0.01 |

3.40 ± 0.41 |

80% Saturation Ammonium

Sulfate |

127.05 ± 2.27 |

9.00± 0.16 |

14.07 ± 2.40 |

| Ultrafiltration (10 kDa) |

1640.80 ± 19.07 |

568.05 ± 3.73 |

8.66 ± 0.64 |

Concentrated cell

suspension |

517.90 ±11.33 |

47.50 ± 0.64 |

10.90 ± 0.09 |

Table 2.

Values of GOS yield, lactose conversion, and productivity for continuous packed-bed bioreactors for the three tested flow rates.

Table 2.

Values of GOS yield, lactose conversion, and productivity for continuous packed-bed bioreactors for the three tested flow rates.

| Flow Rate (mL/h) |

GOS Yield (%) |

Lactose Conversion (%) |

Qp (g/L.h) |

| 1.0 |

24.63 ± 1.98 |

68.38 ± 2.45 |

5.87 ± 0.44 |

| 2.0 |

19.18 ± 3.45 |

37.97 ± 2.84 |

2.57 ± 0.37 |

| 3.0 |

8.35 ± 3.58 |

16.78 ± 2.19 |

0.47 ± 0.33 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

) and Conversion (

) and Conversion ( ).

).

) and Conversion (

) and Conversion ( ).

).

), MRS medium combined with GOS (

), MRS medium combined with GOS ( ), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS (

), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS ( ).

).

), MRS medium combined with GOS (

), MRS medium combined with GOS ( ), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS (

), and percentage of GOS consumption in MRS medium combined with GOS ( ).

).