1. Introduction

As the global population ages and the burden of chronic diseases continues to rise [

1], there is an unprecedented demand for continuous, dynamic, and personalized health monitoring and diagnostic approaches. In this context, wearable medical electronic devices are rapidly advancing from concept to clinical frontiers [

2,

3,

4], aiming to extend traditional hospital-centered diagnosis and treatment to daily home-based and telemedicine settings. Ultrasound imaging, as a cornerstone of clinical diagnostics, plays a vital role in cardiovascular, oncological, and musculoskeletal fields, among others. However, conventional ultrasound systems are constrained by inherent limitations such as rigid probes, bulky structures, and reliance on liquid coupling agents, which hinder their ability to conform closely to irregular body contours (e.g., joints, thoracic cage) or adapt to tissue deformation during daily activities [

5]. Furthermore, they are incapable of supporting long-term continuous monitoring of deep tissue physiology [

6,

7]. These drawbacks severely restrict their application in emerging scenarios such as telemedicine and chronic disease management.

To overcome these barriers, the “ultrasound patch” has emerged. Its core innovation lies in the use of flexible piezoelectric materials (e.g., polyvinylidene fluoride, silicon nanopillars) and lightweight designs, enabling non-invasive, continuous, and accurate monitoring of deep tissues through conformal skin attachment [

5,

8,

9,

10]. For instance, flexible ultrasound transducers (FUST) based on silver nanowires and elastic substrates can withstand tensile strains exceeding 110%, weigh only about 1.58 g, and adapt well to highly curved surfaces such as the breast or carotid artery [

5]. Ultrasound patch (USoP) systems that incorporate signal acquisition, wireless transmission, and data-processing capabilities have been shown to track physiological signals at depths up to 164 mm continuously for 12 hours [

7]. Such breakthroughs not only address wearability challenges but also elevate ultrasound from a diagnostic tool to a platform for real-time physiological data streaming.

Building on this foundation, the scope of ultrasound patches is rapidly expanding from diagnosis toward integrated diagnosis and therapy. Their applications now encompass diverse areas, including: home-based autonomous patches for chronic wound treatment [

11]; real-time bladder volume monitoring for pediatric neurogenic bladder dysfunction [

12]; carotid artery Doppler assessment of cardiovascular function [

13,

14,

15]; sonodynamic therapy for tumors [

16]; precise neuromodulation assisting post-stroke motor recovery [

17]; and interventions for neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease [

9,

18,

19]. This breadth of utility underscores how ultrasound patches are reshaping disease management and treatment paradigms.

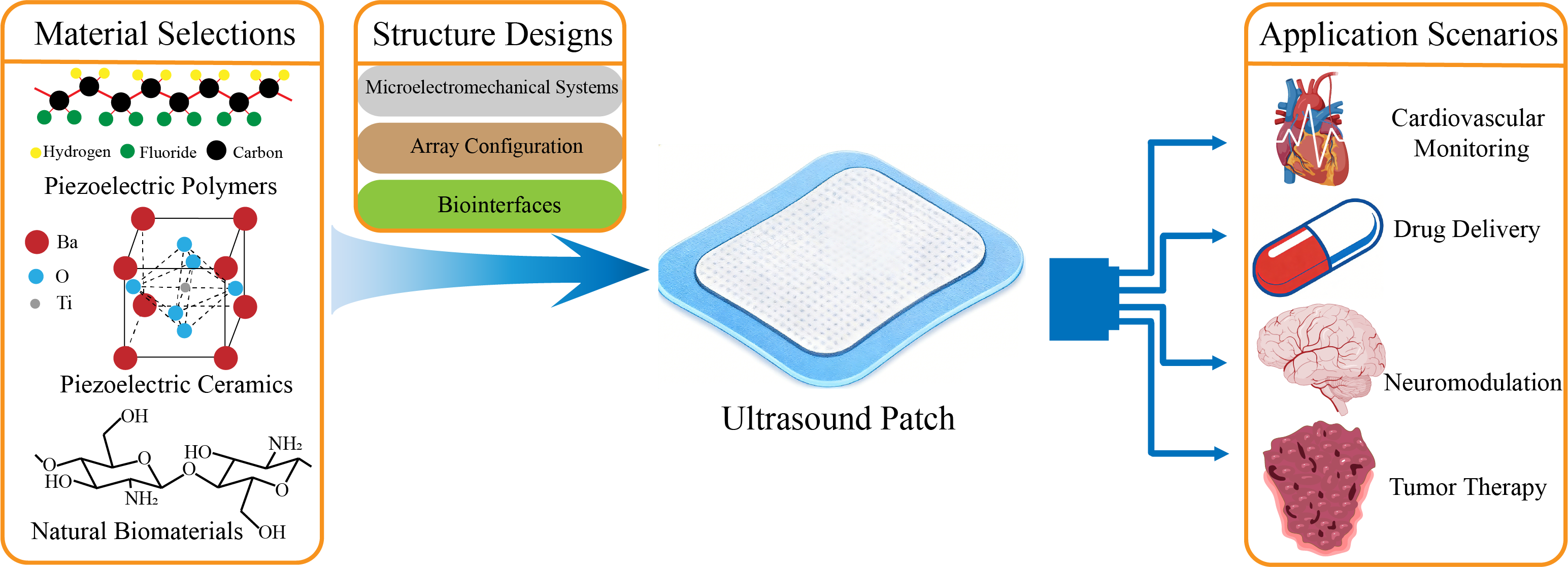

This article systematically reviews recent advances in the design and biomedical applications of ultrasound patches. First, we delve into the evolution of piezoelectric and composite materials that define their performance. Next, we examine innovative designs in transducer architecture and array configurations. Finally, we comprehensively present breakthrough applications in disease diagnosis, drug delivery, neuromodulation, and tumor therapy, while also discussing challenges and future directions toward intelligent, integrated diagnostic-therapeutic systems.

2. Material Selection

In the design of ultrasound patches, material selection is a core determinant of performance and applicable scenarios, with development trends shifting from pursuing single properties toward a balanced integration of energy conversion efficiency, physical flexibility, and biosafety (

Table 1). Early efforts primarily focused on piezoelectric ceramics with high electromechanical conversion efficiency [

20] and piezoelectric polymers offering superior flexibility [

21]. To address challenges related to biocompatibility and environmental sustainability, lead-free piezoelectric materials and natural biomaterials (e.g., chitosan) [

22] have been extensively explored. Concurrently, composite material systems that integrate the advantages of the above mentioned materials have further expanded the application boundaries of ultrasound patches [

23].

Piezoelectric polymers are among the commonly used materials in ultrasound patch design. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and its co-polymers have been widely studied owing to their excellent piezoelectric properties and flexibility. AlMohimeed and Ono [

24] developed a wearable ultrasound sensor (WUS) based on a bilayer PVDF piezoelectric polymer film. Fabricated via a simple, low-cost process, the sensor is flexible, lightweight, thin, and compact, enabling secure attachment to the skin without affecting the contraction dynamics of the target muscle. They employed this WUS to monitor contractions of the human gastrocnemius muscle. Parameters such as maximum contraction thickness and contraction time were extracted, demonstrating the value of PVDF-based ultrasound sensors for low-cost, noninvasive, and continuous monitoring of skeletal muscle contraction characteristics. Furthermore, Liu and Wu [

25] developed a flexible piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducer (PMUT) using silver-coated PVDF film mounted on a laser-processed polymeric substrate via low temperature (<100 ℃) bonding. This PMUT can conform to flat, concave, and convex surfaces while maintaining good acoustic performance, further highlighting the significant potential of PVDF in ultrasound and wearable device applications.

Piezoelectric ceramic materials, known for their high piezoelectric coefficients and favorable electromechanical coupling properties, are employed in ultrasound patches requiring high sensitivity and resolution. Joshi et al. [

26] reported a flexible, row-column addressed PMUT array that uses lead zirconate titanate (PZT) thin film as the active piezoelectric layer and polyimide as the passive layer. After optimization, the array is suitable for wearable devices (e.g., health monitoring) or ultrasonic detection in shallow water environments. Song et al. [

27] integrated high-performance Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 (PMN-PZT) piezoelectric ceramic with a flexible polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate. When attached to the skin, the resulting device enables real-time monitoring of bone condition.

However, lead-containing materials pose certain biotoxicity risks. Although the aforementioned studies employed polymer encapsulation to prevent direct skin contact with lead and emphasized use only in superficial wearables, the adoption of lead-free materials remains a preferable choice. Wang et al. [

28] fabricated a hybrid nanopatch using the lead-free piezoelectric material barium titanate-reduced graphene oxide (BTO/rGO), which successfully promoted the differentiation of neural stem cells into functional neurons and demonstrated significant efficacy in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. By avoiding the toxicity associated with lead-containing materials, such patches can be applied to deeper tissues. Sun et al. [

29] developed a wearable ultrasound blood-pressure monitoring patch using another lead-free material, sodium potassium niobate (KNN). The patch successfully measured changes in vascular diameter and established a relationship between blood pressure and vessel diameter, offering a safe, sustainable, comfortable, and wearable solution for long-term blood-pressure monitoring.

Beyond the commonly used piezoelectric materials described above, certain natural biomaterials and novel composites have also been incorporated into ultrasound patch designs to meet specific requirements such as biocompatibility and bioactivity. Chakraborty et al. [

30] prepared chitosan (CHT) films via solvent-casting followed by cross-linking in an alkaline solution. Under ultrasonic stimulation, the CHT films exhibited notable antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities, along with inhibition of inflammatory cytokines. Liu et al. [

31] developed a bilayer-structured BTO@PCL/GO@GelMA nanopatch, in which a barium titanate-polycaprolactone (BTO@PCL) nanofiber membrane serves as the piezoelectric generation layer, and a graphene oxide-gelatin methacryloyl (GO@GelMA) hydrogel layer functions as the neural interface. Under low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) stimulation, the patch converts mechanical energy into electrical energy to deliver wireless electrical stimulation, significantly promoting peripheral nerve repair and functional recovery. This illustrates the integrated advantages of piezoelectric composites in neuromodulation and tissue regeneration.

3. Structure Design

3.1. Transducer Structural Innovation and Miniaturization

The enhancement of core performance in ultrasound patches primarily relies on breakthrough designs in both piezoelectric materials and transducer architecture. Traditional rigid piezoelectric ceramics, due to their poor conformity to human body contours, severely constrain wearing comfort and acoustic field stability. Consequently, flexible piezoelectric composites have emerged as a crucial solution. Feng et al. [

32] developed a flexible ultrasound patch based on carbon nanotube (CNT) films. Employing a sandwich structure composed of a CNT film, a thermal protective layer, and a heat sinking layer (

Figure 1a), the patch generates ultrasound via the thermoacoustic effect and achieves adaptive conformal attachment to irregular body surfaces. This design offers a promising foundation for lightweight, wearable therapeutic devices. Gerardo et al. [

33] proposed a design for low-cost, polymer-based capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducers (polyCMUTs). This approach substitutes traditional piezoelectric ceramics with the photosensitive polymer SU-8 and incorporates an embedded electrode design, featuring low operating voltage and high sensitivity, thereby significantly reducing energy consumption and fabrication complexity (

Figure 1b). Inspired by traditional Chinese mortise-and-tenon joinery, Liu et al. [

34] composited an amino-anchored metal-organic framework (MOF) with PVDF, resulting in a 40% increase in β-phase content, a 550% enhancement in remnant polarization, and improved X-ray responsiveness, laying a material foundation for integrated diagnosis and therapy.

Beyond material systems, the structural miniaturization of transducers via microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) processes represents another key pathway to reconcile the demands of deep-tissue imaging and implantable applications. Zhang et al. [

35] developed a 2D PMUT array using MEMS technology, which innovatively adopts a three-level driving architecture of “unit-element-array” (

Figure 1c). Operating at only 5V, it achieves 3D volumetric imaging at a frame rate of 11 kHz (covering 40×40×70 mm3), paving the way for long-term wearable imaging of various organs within deep tissues. Gami et al. [

36] demonstrated the feasibility of PMUTs for wearable vascular imaging, finding comparable performance in pulse wave imaging (PWI) between a miniaturized PMUT array and a clinical L7-4 probe, thereby opening new avenues for cardiovascular health monitoring.

3.2. Array Configuration and Acoustic Field Control

To accommodate complex anatomical structures, multi-modal integrated arrays have become key to enhancing diagnostic and therapeutic precision. Pashaei et al. [

37] designed a body-conforming dual-mode patch integrating a 64-element, 5 MHz imaging array with an 8-element, 1.3 MHz neuromodulation array. By utilizing real-time strain-sensing feedback to optimize acoustic beam focusing and combining high-voltage multiplexing technology, they achieved a 5 dB improvement in echo signal-to-noise ratio, enabling precise targeting of structures like the vagus nerve. Similarly, Huan et al. [

38] assembled imaging (4 MHz) and neuromodulation (1.3 MHz) transducers on a flexible printed circuit board (

Figure 2a), pioneering a proportional-integral controller based on electromyographic feedback to dynamically adjust ultrasound intensity and compensate for inter-individual variability.

Regarding high-density array design, Costa et al. [

39] proposed a pixel-matched beamforming technique, directly integrating piezoelectric ultrasound transducers onto a complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) chip (4×5 mm²) (

Figure 2b). This supports precise 3D positioning of ultrasonic focal spots with arbitrary pulse widths, providing a new paradigm for powering implantable devices and neuromodulation. Chen et al. [

40] innovatively developed a transparent ultrasonic transducer (TUT) array using lithium niobate crystals, enabling synchronous quad-modal imaging combining photoacoustic, ultrasound, Doppler, and fluorescence techniques. When the 64-element, 6 MHz array is directly coupled to tissue, it can resolve blood vessels and tumors with high resolution, offering a novel tool for endoscopic and wearable imaging.

For imaging highly curved organs, biomimetic structural designs significantly improve acoustic performance. Du et al. [

41] developed a honeycomb-structured conformable ultrasound breast patch (

Figure 2c). This patch integrates a 1D phased array with a rotatable tracker, utilizing the honeycomb architecture to enable large-area, deep-tissue, multi-angle scanning of the entire breast region. Its structure employs a composite layer design of thermoplastic polyurethane and polylactic acid, balancing flexibility and rigidity, supporting 360° rotation and path tracking. Yuan et al. [

42] reported a skin-adaptive focused ultrasound patch (

Figure 2d). Its array employs a biomimetic design that utilizes the skin's own curvature as a natural acoustic lens, allowing the ultrasound beam width (2.1–4.6 mm) and depth (3.3–53.0 mm) to adaptively match the dimensions and locations of subcutaneous blood vessels under varying curvatures (radius: 10–60 mm). This achieves stable, high signal-to-noise ratio hemodynamic monitoring at sites with highly variable curvature, such as the radial and carotid arteries. These works demonstrate that biomimetic structural design effectively addresses the adaptation challenge for complex anatomical surfaces and is a key pathway for enhancing the performance of wearable ultrasound imaging.

3.3. Lightweight Structures and Biointerfaces

The long-term usability of wearable devices demands that structural design achieves lightweight characteristics while simultaneously ensuring biocompatibility and operational convenience. This is primarily manifested in three aspects: lightweight therapeutic architectures for surface-level conditions, intelligent structures enabling precise transdermal delivery, and tissue-interfacing designs that guarantee signal quality.

In the field of chronic wound therapy, Ngo et al. [

43] employed a disk-shaped patch architecture (diameter 40 mm, weight <20 g) that can be directly embedded into dressings. Applying non-thermal ultrasound (20-100 kHz, intensity 100 mW/cm²) for safe treatment durations of up to 4 hours, this approach reduced diabetic ulcer healing time from 12 weeks to 4.7 weeks. Lyu et al. [

44] constructed a conformable ultrasonic patch by discretizing the piezoelectric ceramic into a linear array of units integrated with flexible “island-bridge” circuitry and serpentine interconnects (

Figure 3a). Owing to its unique bending-induced acoustic beam self-focusing capability, the patch achieved a reduction in wound healing time by approximately 40% in a type II diabetic rat model. For transdermal delivery scenarios, Huang et al. [

45] embedded drug-loaded polyester microcapsules within a four-arm polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogel patch. Ultrasound was utilized to synchronously trigger drug release and enhance transdermal efficiency. In vitro experiments demonstrated negligible drug permeation in the absence of ultrasonic stimulation, achieving precise spatiotemporal control.

The adhesive stability of the biointerface directly impacts signal quality. Ma et al. [

46] developed a multi-level coupled hydrogel interface (PAMS patch) by mimicking the biological structures of octopus suckers and snail mucus (

Figure 3b), establishing a stable and intimate mechano-electronic coupling at the tissue-electronics interface. Xue et al. [

47] constructed an integrated bioelectronic wearable platform by combining a stretchable lead-free ultrasound array, a bioadhesive hydrogel, and dissolvable microneedles (

Figure 3c). The tight coupling between its flexible substrate and the tissue surface provides a robust foundation for sono-immunotherapy of tumors.

4. Application Scenarios

Building upon innovations in materials and transducer architecture, ultrasound patches are unlocking a spectrum of closed-loop biomedical applications (

Figure 4). Compared to traditional rigid ultrasound probes, ultrasound patches represent a breakthrough innovation in terms of wearability, tissue adaptability, and functional integration. Conventional probes are limited by their rigid substrates and dependence on liquid coupling agents, making it difficult to achieve conformal contact with irregular body surfaces, which compromises signal stability and may increase the risk of wound infection [

44]. In contrast, flexible patches, through the miniaturization of piezoelectric materials [

39] and integration with elastic substrates [

10], can seamlessly conform to skin curvatures, significantly improving detection accuracy and therapeutic reliability. Furthermore, the patch-based design facilitates long-term continuous monitoring, providing dynamic data support for chronic disease management (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, diabetes) [

7,

48]. This “unobtrusive wearability” characteristic greatly enhances patient compliance and creates conditions for home-based health management [

49].

4.1. Disease Diagnosis and Imaging

Innovations in ultrasound patches within the field of diagnostic imaging are first exemplified by their ability to enable long-term, continuous monitoring of deep-seated tissues such as those in the cardiovascular system. Compared to traditional bulky ultrasound equipment, the flexible patch design effectively overcomes signal attenuation and probe displacement caused by patient movement, significantly enhancing signal stability and data reliability during dynamic monitoring. Their superior performance has been validated in several pioneering studies: Lin et al. [

7] developed a fully integrated, autonomous wearable USoP system. By incorporating miniaturized flexible control circuits and machine learning algorithms, the system achieves automatic tracking of moving targets (e.g., a beating heart) and can continuously monitor physiological signals from tissues up to 164 mm deep—such as central arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output—for up to 12 hours. This system represents a significant breakthrough in wearable ultrasound diagnostics toward prolonged, dynamic deep-tissue monitoring, offering a novel tool for at-home cardiovascular health management. Furthermore, the patch design has also been applied to emerging imaging modalities. For example, the photoacoustic patch developed by Gao et al. [

50] achieved, for the first time, 3D imaging of hemoglobin at subcutaneous depths >2 cm, demonstrating the platform's substantial potential in expanding the detection depth and informational dimensions of wearable imaging.

Enhancements in imaging performance rely on synergistic innovations in piezoelectric material systems and miniaturized devices. Regarding lead-free piezoelectric materials, the wearable ultrasound patch based on KNN developed by Sun et al. [

29] employs biocompatible silicone rubber encapsulation, enabling tight skin conformal attachment without the need for coupling gel. By measuring changes in vascular diameter and establishing a quantitative relationship with blood pressure, its reliability for continuous non-invasive blood pressure monitoring was validated in an in vitro simulation system. In terms of device architecture, the silicon nanopillar capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer (snCMUT) array by Kang et al. [

10] combines lead-free design and miniaturized fabrication (thickness ~900 μm) with high transmission efficiency, excellent flexibility, and low power consumption. Operating at low voltage, this device achieves high resolution and a penetration depth of approximately 70 mm, and has been successfully applied to high-definition imaging of the human carotid artery and continuous blood pressure monitoring, fully demonstrating the pivotal role of miniaturization in improving wearability and imaging quality.

The functionality of ultrasound patches is expanding from pure imaging toward integrated systems featuring multimodal sensing and image-guided capabilities, laying the foundation for their application in theranostics. In multimodal sensing, Sempionatto et al. [

48] developed an epidermal patch that innovatively integrates an ultrasound transducer with electrochemical sensors on a single flexible platform, enabling synchronous non-invasive monitoring of hemodynamic parameters and multiple metabolic biomarkers. In image guidance, the body-conforming dual-mode ultrasound patch for image-guided neuromodulation designed by Pashaei et al. [

37] introduced an algorithm that uses adjacent blood vessels (e.g., the carotid artery) as imaging landmarks for automatic target nerve localization, establishing a basis for precise neural therapies. More importantly, ultrasound patches have begun to demonstrate potential for transitioning directly from diagnosis to closed-loop therapy. For instance, research by Yang et al. [

51] and Luo et al. [

52] showcased applications of ultrasound patches in intervening in type II diabetes and achieving dynamic blood glucose regulation, respectively, offering a preliminary glimpse into their role as intelligent diagnostic-therapeutic platforms integrating sensing, decision-making, and intervention.

4.2. Drug Delivery

Ultrasound patches revolutionize drug delivery and neuromodulation strategies through synergistic energy-matter delivery mechanisms. In the field of transdermal administration, these patches integrate physical permeation-enhancing techniques with intelligent drug release technologies, significantly improving the delivery efficiency of biological macromolecules.

Regarding the fusion of nanocarriers with patches, researchers are dedicated to embedding drug-loaded nanoparticles within biocompatible patch matrices, combined with ultrasound-controlled release, to achieve efficient and sustained drug delivery. Ali et al. [

53] developed a chitosan patch loaded with repaglinide solid lipid nanoparticles (REP-SLN-TDDS). This patch successfully dispersed SLNs uniformly within its matrix and exhibited biphasic release characteristics: approximately 36% of the drug was released within the first 2 hours, with cumulative release reaching 80% over 24 hours. Most importantly, its transdermal flux was enhanced by 3.56-fold. In vivo studies in rats demonstrated that it could maintain a more prolonged and effective plasma drug concentration and significantly lower blood glucose levels, proving its potential for improving the delivery of anti-diabetic drugs with low oral bioavailability. Similarly, Li et al. [

54] prepared chitosan-alendronate sodium nanoparticles for osteoporosis treatment, loaded them into a hydroxypropyl methylcellulose patch, and combined them with ultrasound-enhanced permeation. This approach increased the bioavailability by 6-fold compared to a conventional patch in rats and was more effective in reducing serum calcium levels (from 16 mg/dl to 4 mg/dl), highlighting the advantage of nanoparticle-ultrasound patch combinations in promoting the transdermal delivery of macromolecules and poorly soluble drugs.

Microstructured patch designs, combined with ultrasound and other physical enhancement strategies, further overcome skin barrier limitations by actively creating microchannels or leveraging synergistic physical effects. This is particularly suitable for macromolecule delivery or localized therapy. Bok et al. [

55] designed a unique needle-free microcup patch integrating a drug reservoir (loaded with an ultra-thin salmon DNA-based drug film), an adhesion system, and physical stimuli sources (ultrasound, electric current). In the presence of moisture, the DNA film dissolves to release the drug. Combined with ultrasound or electrical stimulation, it significantly promotes drug penetration through the stratum corneum and the entire epidermis while reducing skin irritation. Another study [

56] developed a multifunctional system composed of hyaluronic acid microneedles, where the drug load at the needle tips was controlled by adjusting solution concentration. It was found that ultrasonic cavitation pressure vibrations induced microneedle dissolution, while alternating current iontophoresis enhanced the electro-osmotic driven diffusion of charged molecules (e.g., Rhodamine B). This synergistic effect of ultrasound and iontophoresis within the microneedles significantly shortened the initial delivery time and increased permeability compared to passive diffusion or ultrasound alone, offering a new approach for macromolecular drugs and time-dependent delivery. Li et al. [

57] constructed a Piezoelectric-driven Microneedle Array (PDMA) for psoriasis treatment. A finite element model confirmed that PDMA could generate an ultrasonic field. In vitro experiments showed PDMA increased the penetration depth of methotrexate (MTX) by 9-fold. In vivo studies demonstrated that PDMA-mediated MTX delivery was significantly superior to oral administration in alleviating psoriasis symptoms, achieving better efficacy with only 50% of the oral dose, providing an efficient and minimally invasive alternative for localized treatment.

Intelligent stimuli-responsive hydrogel and microcapsule patches focus on achieving on-demand and precise drug delivery, leveraging materials responsive to external stimuli (primarily ultrasound) for controlled therapy. Huang et al. [

45] embedded diclofenac sodium (DS)-loaded polyester microcapsules into a hydrogel patch based on four-arm polyethylene glycol. This design endowed the patch with good biocompatibility, excellent skin adhesion, and controlled ultrasound-responsive release behavior. Both ex vivo and in vivo experiments indicated that under ultrasound triggering (serving simultaneously as a release trigger and permeation enhancer), the encapsulated drug was rapidly released and penetrated the skin barrier. In contrast, negligible drug release and permeation occurred in the absence of ultrasound, achieving improved and precise control over DS transdermal delivery, potentially useful for on-demand treatment of arthritis and soft tissue injuries. Zhang et al. [

58] proposed an innovative sonoelectric synergistic enhancement strategy. They developed a transdermal patch combining micron-sized gas cavitation bubbles and a piezoelectric soft structure. When ultrasound is applied, the gas cavitation converts part of the acoustic energy into electricity. The enhancement in drug delivery stems from the synergistic effect of ultrasonic pressure (promoting permeation) and the electric field (potentially facilitating the migration of ionized drugs). Animal experiments demonstrated that this patch combined with ultrasound promoted permeation increased the plasma drug concentration 100% more than using ultrasound alone, far outperforming delivery enhanced solely by an electric field or passive diffusion without external fields.

Comparative studies on ultrasound parameter optimization and physical permeation enhancement technologies provide crucial evidence for clinical application. Vaidya et al. [

59] compared the effects of three physical permeation enhancement techniques (ultrasound, electroporation, cold laser) on the transdermal efficacy of an MTX patch for treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In vitro studies indicated that ultrasound (via a sonoporation effect) offered the best permeation enhancement. Pharmacodynamic experiments in a rat RA model confirmed that the group receiving the MTX patch following ultrasound pretreatment showed significantly greater reduction in hind paw swelling, improved mobility scores, and pain relief compared to the group using only the MTX patch, with animals recovering faster. This established the value of ultrasound as an efficient permeation enhancer for MTX patches in RA treatment.

4.3. Neuromodulation

The application of ultrasound patch technology in the field of neuromodulation is gradually revealing its unique potential for non-invasive intervention, which hinges on the precise modulation of ion channel activity and neural network excitability through mechanical and thermal effects. A number of studies utilizing patch-clamp techniques have delved into the molecular mechanisms by which ultrasound influences neuronal electrical activity. Cui et al. [

60] found that ultrasound stimulation could significantly suppress voltage-gated potassium currents (including transient outward and delayed rectifier potassium currents) in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. This inhibition of potassium efflux directly led to an increase in the frequency of spontaneous neuronal firing. This phenomenon was further explored mechanistically by Prieto et al. [

61], who reported a frequency-dependent bidirectional modulation of action potential firing in CA1 neurons by high-frequency ultrasound (43 MHz): ultrasound suppressed action potentials when neurons received low input currents (near threshold) and fired at low frequencies, but enhanced firing frequency under conditions of high input current and high firing frequency. The researchers proposed that ultrasound might achieve this modulation by activating a standing potassium conductance, potentially via thermally- or mechanically-sensitive two-pore domain potassium (K2P) channels, with finite element modeling suggesting a temperature rise of less than 2°C as the primary factor. Sorum et al. [

62,

63], through quantitative membrane tension measurements and fluorescence imaging, confirmed the high sensitivity and broad response range of mechanosensitive K2P channels to tension, and demonstrated that low-intensity, low-frequency focused ultrasound could activate these channels by increasing membrane tension, providing experimental evidence for the direct action of ultrasound-mediated mechanical force on neuronal membranes.

At the level of calcium signaling and synaptic transmission, ultrasound stimulation demonstrates a complex capacity to regulate neural network activity. Fan et al. [

64] demonstrated that low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) significantly enhanced the frequency of spontaneous action potentials, as well as the frequency and amplitude of excitatory postsynaptic spontaneous currents (EPSCs) in cultured hippocampal neurons, with effects persisting for over 10 minutes post-stimulation. Combining calcium imaging, they elucidated that LIPUS promotes an increase in cytosolic calcium concentration via L-type calcium channels (LTCCs), subsequently activating the CaMKII-CREB pathway to regulate gene transcription. Li et al. [

65] further observed that LIPUS evoked significant increases in both the frequency and amplitude of EPSCs in high-density cultured hippocampal neurons, indicating enhanced glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Mechanistic analysis revealed that extracellular calcium influx, action potential firing, and synaptic transmission were necessary for this response. Concurrent calcium imaging showed that LIPUS could recruit recurrent excitatory network activity in high-density cultures, lasting for tens to hundreds of seconds, highlighting the potent regulatory potential of ultrasound on neural network cascades.

Research on the application of ultrasound in treating neurological disorders is advancing from animal models toward clinical translation, with notable progress particularly in epilepsy intervention. Lin et al. [

66] applied LIPUS (750 kHz, 0.35 MPa) to stimulate the epileptogenic focus for 30 minutes in a penicillin-induced epilepsy macaque model. This treatment significantly reduced both the total number of seizures (sham group: 107.7 ± 1.2; ultrasound group: 66.0 ± 7.9) and the hourly seizure frequency (sham group: 15.6 ± 1.2; ultrasound group: 9.6 ± 1.5) over a 16-hour period. In ex vivo experiments on human epileptic brain slices, 28 MHz ultrasound (0.13 MPa) suppressed over 65% of epileptiform activity. Xu et al. [

67] innovatively combined sonogenetics technology, specifically expressing the mechanosensitive ion channel MscL-G22S in parvalbumin (PV)-positive and somatostatin (SST)-positive inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampal CA1 region, followed by ultrasound stimulation. Results showed that activation of PV interneurons induced by MscL-G22S-mediated sonogenetics (MG-SOG) effectively ameliorated kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus (SE) in mice and corrected SE-associated electrophysiological abnormalities in the CA1 region, while activating SST interneurons was ineffective. This provides a novel strategy for precise ultrasound modulation targeting specific neural circuits. Furthermore, Zou et al. [

68] developed a portable, integrated wearable ultrasound system. Using a flexible honeycomb-structured ultrasound array patch, they achieved continuous treatment in a mouse model of familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD). The system effectively reduced cerebral β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, improved cognitive function, and promoted microglial phagocytosis of Aβ plaques and their polarization toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, opening a new avenue for the non-invasive treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

In summary, ultrasound modulates neural function through multi-scale mechanisms (ion channels, synaptic transmission, network activity) and demonstrates broad clinical application prospects in intervening in major neurological disorders such as epilepsy and Alzheimer's disease. From the elucidation of fundamental ion channel mechanisms to the development of precise sonogenetic modulation strategies, and onward to the clinical translation of wearable devices, this field is advancing toward a new era of efficient, precise, and personalized neuromodulation.

4.4. Tumor Diagnosis and Therapy

As an emerging platform for transdermal drug delivery and therapy, ultrasound patches are driving innovation in oncology toward integrated and precise theranostic models. By integrating technologies such as sonosensitive materials, piezoelectric components, and microneedles, they enable precise tumor monitoring, drug delivery, and synergistic therapies, significantly improving treatment efficacy and safety.

The key to advancing tumor theranostics with ultrasound patches lies in their ability to integrate real-time monitoring with immediate therapeutic intervention on a single platform, forming a dynamic management loop. This concept transcends mere diagnosis or treatment, aiming to optimize therapeutic processes through real-time feedback. For instance, Siboro et al. [

69] developed a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) film patch based on hafnium oxide nanoparticles (HfO2 NPs). This patch functions as a dielectric elastomer strain sensor, monitoring impedance changes induced by tumor volume variation in real time. It ingeniously combines diagnostic and therapeutic functions: as a dielectric elastomer strain sensor, it can wirelessly assess disease progression by detecting impedance changes from tumor volume; simultaneously, the loaded HfO2 NPs act as sonosensitizers, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) under ultrasound irradiation to directly kill cancer cells. This “monitoring-therapy” integrated design provides a highly promising tool for achieving personalized, dynamic tumor treatment.

Regarding specific therapeutic strategies, the ultrasound patch platform primarily supports two major innovative modalities: active drug delivery and in situ activation therapy. Active drug delivery strategies focus on utilizing the patch to physically breach biological barriers and precisely transport therapeutic agents to the tumor site. Xue et al. [

47] proposed an integrated wearable flexible ultrasound microneedle patch (wf-UMP), which combines a stretchable lead-free ultrasound transducer array, a bioadhesive hydrogel, and drug-loaded dissolvable microneedles. It efficiently delivers anticancer drugs, not only inducing tumor cell apoptosis but also, when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, activating systemic anti-tumor immunity and inhibiting distant metastasis. The in situ activation therapy strategy relies on the patch generating a controllable ultrasound field to activate pre-accumulated or intrinsic sonosensitive substances at the tumor site, producing therapeutic effects locally without the need for complex delivery systems. Zou et al. [

16] developed a fully integrated conformal wearable ultrasound patch (CWUS Patch). Through a multi-channel ultrasound array that precisely focuses on the lesion area, it controllably activates sonosensitizers to generate abundant ROS, enabling continuous sonodynamic therapy. This study validated the ability of ultrasound to penetrate deep tumor tissues in a mouse breast cancer model, demonstrating its potential for non-invasive, continuous, and efficient treatment of deep-seated tumors. Currently, many advanced nano-formulations [

70,

71,

72] designed to enhance sonodynamic efficacy also heavily depend on a portable platform capable of providing localized, controllable ultrasound fields. This further underscores the pivotal role of ultrasound patches as a crucial hub in achieving precise and minimally invasive tumor therapy.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Ultrasound patches still face multiple challenges on the path toward clinical translation. Foremost among these are the limitations in materials and device performance. While traditional lead-based piezoelectric materials (e.g., PZT) offer stable performance, their rigidity, environmental toxicity (e.g., lead contamination), and modulus mismatch with biological tissues severely constrain long-term wearing comfort and biocompatibility [

10]. Furthermore, Oh et al. [

73] point out that low energy transfer efficiency due to ultrasonic beam steering errors remains a bottleneck for the practical application of ultrasound-powered implantable devices. They developed a lightweight patch-type ultrasonic transducer array which achieved image-guided adaptive targeted energy delivery in ex vivo experiments, significantly improving transmission efficiency and opening a new avenue for powering implantable medical devices.

The lack of clinical validation and standardization constitutes another critical barrier. Amado-Rey et al. [

49] emphasize that the journey of wearable ultrasound devices from the laboratory to the medical market involves multiple stages: technical development, signal processing, laboratory validation, and clinical validation. However, most current research remains at the stage of animal models or ex vitro experiments, lacking long-term human safety and efficacy data. Moreover, the ultrasound parameters (frequency, intensity, duty cycle) employed vary widely across different studies, highlighting an urgent need to establish unified standards for safety and efficacy evaluation.

The future development of ultrasound patches will focus on the construction of intelligent diagnostic-therapeutic systems. The USoP developed by Lin et al. [

7], which integrates flexible circuits, ultrasound transducer arrays, and machine learning algorithms, enables continuous monitoring of physiological parameters in deep tissues and addresses motion artifacts through automatic target-tracking technology, laying the hardware foundation for closed-loop feedback therapy. Sempionatto et al. [

48] further merged ultrasound-based hemodynamic monitoring with electrochemical sensing of multiple biomarkers (glucose, lactate, caffeine, alcohol). By capturing the linked physiological responses following exercise or food intake (such as blood glucose fluctuations and compensatory blood pressure increases), this provides multimodal data support for personalized health management. In terms of structural design, continuous optimization of array configurations and acoustic field control strategies (e.g., honeycomb-like patches, multimodal integrated arrays) will further enhance adaptability to complex anatomical structures and therapeutic precision.

Neuromodulation and metabolic disease treatment represent highly promising application directions for ultrasound patches. Xu et al. [

67] employed sonogenetics to specifically activate PV interneurons in the hippocampal CA1 region, significantly alleviating status epilepticus, thereby opening a new avenue for non-invasive, precise modulation of neuropsychiatric disorders. Yang et al. [

51] used a wearable ultrasound patch to intervene in the liver-pancreas region of db/db mice, confirming that LIPUS can improve glucose tolerance, reduce insulin resistance without tissue damage, offering a novel non-pharmacological intervention strategy for type II diabetes.

Innovations in materials and energy technology will drive significant leaps in device performance. The snCMUT developed by Kang's team [

10] employs a lead-free design, combining high transmission efficiency, flexibility, and low cost, and has been successfully applied to high-definition imaging of the human carotid artery and continuous blood pressure waveform monitoring. Zhang et al. [

74] created a photoacoustic patch based on a self-healing PDMS/carbon nanotube composite. It achieved a breakthrough in performance with >25 MPa high acoustic pressure output and a photoacoustic energy conversion efficiency of 10.66×10-3, alongside a high laser damage threshold, providing a novel solution for designing and fabricating new photoacoustic devices.

The clinical translation pathway for ultrasound patches encompasses the entire process from laboratory research to large-scale medical application, requiring systematic breakthroughs at several key stages. Current research is predominantly concentrated on animal models and ex vivo experiments. There is a need for multicenter, large-sample randomized controlled trials to validate their long-term safety and efficacy in scenarios such as chronic disease management [

51], neuromodulation [

67,

68], and tumor therapy [

16]. Concurrently, it is essential to establish unified safety standards and efficacy evaluation systems covering key parameters like frequency, intensity, and duration to regulate product development and clinical use. Furthermore, enhanced collaboration with regulatory bodies is needed to optimize medical device certification processes. Continuous refinement of diagnostic-therapeutic algorithms and user interfaces based on multimodal sensing [

48] through real-world studies will ultimately promote the widespread adoption of ultrasound patches in home health management, telemedicine, and personalized therapy.

In summary, ultrasound patches are evolving from single-function devices into intelligent “sensing-feedback-therapy” systems. Future efforts should focus on breakthroughs in three key areas: elucidating biological mechanisms (e.g., molecular targets for neuromodulation), validating clinical translation (e.g., multicenter RCTs), and establishing standardization (e.g., safety thresholds for ultrasound parameters). This will ultimately enable their large-scale application in chronic disease management and precision medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and S.W.; methodology, J.Z., Y.H. and Y.X; literature investigation and data curation, J.Z. and Y.H; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and Y.H; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., W.G. and S.W.; visualization, J.Z. and Y.X.; supervision, Y.L. and S.W.; project administration, Y.L. and S.W.; funding acquisition, Y.L. and S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the following fundings: the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (JQ24049 and L222066), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82472160), and the Beijing Physician Scientist Training Project (BJPSTP-2025-31).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek-V3.2 for the purposes of refining the structure and language of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Aβ |

β-Amyloid |

| BTO |

Barium Titanate |

| CHT |

Chitosan |

| CMOS |

Complementary Metal-oxide-semiconductor |

| CMUT |

Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer |

| CNT |

Carbon Nanotube |

| CWUS Patch |

Conformal Wearable Ultrasound Patch |

| DS |

Diclofenac Sodium |

| EPSC |

Excitatory Postsynaptic Spontaneous Current |

| FAD |

Familial Alzheimer’s Disease |

| FUST |

Flexible Ultrasound Transducers |

| GelMA |

Gelatin Methacryloyl |

| HfO2

|

Hafnium Oxide |

| KA |

Kainic Acid |

| KNN |

Potassium Sodium Niobate |

| K2P channels |

two-pore domain potassium channels |

| LIPUS |

Low-intensity Pulsed Ultrasound |

| LTCC |

L-type Calcium Channel |

| MEMS |

Microelectromechanical Systems |

| MG-SOG |

MscL-G22S-mediated Sonogenetics |

| MOF |

Metal-organic Framework |

| MTX |

Methotrexate |

| NP |

Nanoparticle |

| PCL |

polycaprolactone |

| PDMA |

Piezoelectric-driven Microneedle Array |

| PDMS |

polydimethylsiloxane |

| PEG |

Polyethyleneglycol |

| PMN |

Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3

|

| PMUT |

Piezoelectric Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer |

| PV |

Parvalbumin |

| PVDF |

Polyvinylidene Fluoride |

| PWI |

Pulse Wave Imaging |

| PZT |

Lead Zirconate Titanate |

| RA |

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

| REP |

Repaglinide |

| rGO |

Reduced Graphene Oxide |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SE |

Status Epilepticus |

| SLN |

Solid Lipid Nanoparticles |

| sn-CMUT |

Silicon Nanopillar Capacitive Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer |

| SST |

Somatostatin |

| TDDS |

Transdermal Delivery System |

| TPU |

Thermoplastic Polyurethane |

| TUT |

Transparent Ultrasonic Transducer |

| UsoP |

Ultrasound Patch |

| wf-UMP |

Wearable Flexible Ultrasound Microneedle Patch |

| WUS |

Wearable Ultrasound Sensor |

References

- Beard, J.R.; Officer, A.; de Carvalho, I.A.; Sadana, R.; Pot, A.M.; Michel, J.P.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Epping-Jordan, J.E.; Peeters, G.; Mahanani, W.R.; et al. The World report on ageing and health: a policy framework for healthy ageing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2145-2154. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; Gao, F.; Xu, S.; Wu, X.; Ye, Z. Wearable Health Devices in Health Care: Narrative Systematic Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18907. [CrossRef]

- Mattison, G.; Canfell, O.; Forrester, D.; Dobbins, C.; Smith, D.; Töyräs, J.; Sullivan, C. The Influence of Wearables on Health Care Outcomes in Chronic Disease: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2022, 24, e36690. [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, N.; Rabiee, M. Wearable Aptasensors. Anal Chem 2024, 96, 19160-19182. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, W.; Shang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zheng, H.; Gu, D.; Wu, D.; Ma, T. Skin-Conformable Flexible and Stretchable Ultrasound Transducer for Wearable Imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2024, 71, 811-820. [CrossRef]

- Bashatah, A.; Mukherjee, B.; Rima, A.; Patwardhan, S.; Otto, P.; Sutherland, R.; King, E.L.; Lancaster, B.; Aher, A.; Gibson, G.; et al. Wearable Ultrasound System Using Low-Voltage Time Delay Spectrometry for Dynamic Tissue Imaging. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2024, 71, 3232-3243. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Bian, Y.; Wu, R.S.; Park, G.; Lou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; et al. A fully integrated wearable ultrasound system to monitor deep tissues in moving subjects. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 448-457. [CrossRef]

- Bourbakis, N.; Tsakalakis, M. A 3-D Ultrasound Wearable Array Prognosis System With Advanced Imaging Capabilities. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2021, 68, 1062-1072. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Gong, Y.; Chukwu, C.; Ye, D.; Yue, Y.; Yuan, J.; Kravitz, A.V.; Chen, H. Airy-beam holographic sonogenetics for advancing neuromodulation precision and flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2402200121. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.; Cho, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Shim, S.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, B.; Lee, Y.S.; Park, E.A.; Lee, W.; Kim, H.; et al. Silicon nanocolumn-based disposable and flexible ultrasound patches. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 6609. [CrossRef]

- Barbarevech, K.; Schafer, M.E.; DiMaria-Ghalili, R.A.; Hyatt, J.; Lewin, P.A. Design of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Device to be Used in At-Home Setting-A Holistic Approach. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2024, 71, 821-830. [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.Y.; Logvinenko, T.; Omar, B.; Oottamasathien, S.; Kurtz, M.; Estrada, C.; Bauer, S.; Nelson, C.P. Real-Time Bladder Volume Monitoring for Pediatric Patients Using a Commercially Available Wearable Ultrasound Device. Neurourol Urodyn 2025, 44, 1188-1192. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.S. Functional Hemodynamic Monitoring With a Wireless Ultrasound Patch. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2021, 35, 1509-1515. [CrossRef]

- Kenny, J.S.; Munding, C.E.; Eibl, J.K.; Eibl, A.M.; Long, B.F.; Boyes, A.; Yin, J.; Verrecchia, P.; Parrotta, M.; Gatzke, R.; et al. A novel, hands-free ultrasound patch for continuous monitoring of quantitative Doppler in the carotid artery. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7780. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Qu, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, J. Continuous Monitoring of Blood Pressure by Measuring Local Pulse Wave Velocity Using Wearable Micromachined Ultrasonic Probes. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2025, 72, 1615-1624. [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Xu, T. A Fully Integrated Conformal Wearable Ultrasound Patch for Continuous Sonodynamic Therapy. Adv Mater 2024, 36, e2409528. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Anguluan, E.; Kum, J.; Sanchez-Casanova, J.; Park, T.Y.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, H. Wearable Transcranial Ultrasound System for Remote Stimulation of Freely Moving Animal. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2021, 68, 2195-2202. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Guo, N.; Hu, C.; Ni, R.; Zhang, X.; Meng, Z.; Liu, T.; Ding, S.; Ding, W.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Efficacy of Wearable low-intensity pulsed Ultrasound treatment in the Movement disorder in Parkinson's disease (the SWUMP trial): protocol for a single-site, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Trials 2024, 25, 275. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Niu, L.; Xia, X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, X.; Su, M.; Guo, R.; Meng, L.; Zheng, H. Wearable Ultrasound Improves Motor Function in an MPTP Mouse Model of Parkinson's Disease. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2019, 66, 3006-3013. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yoon, H.; Viswanath, S.; Dagdeviren, C. Conformable Piezoelectric Devices and Systems for Advanced Wearable and Implantable Biomedical Applications. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2025, 27, 255-282. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Feng, Z.; Yao, F.-Z.; Zhang, M.-H.; Wang, K.; Wei, Y.; Gong, W.; Rödel, J. Flexible piezoelectrics: integration of sensing, actuating and energy harvesting. npj Flexible Electronics 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Wang, L.; Makihata, M.; Liu, H.C.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, X. Bioadhesive ultrasound for long-term continuous imaging of diverse organs. Science 2022, 377, 517-523. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Qin, L. Flexible Electronics: Advancements and Applications of Flexible Piezoelectric Composites in Modern Sensing Technologies. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- AlMohimeed, I.; Ono, Y. Ultrasound Measurement of Skeletal Muscle Contractile Parameters Using Flexible and Wearable Single-Element Ultrasonic Sensor. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, D. Low Temperature Adhesive Bonding-Based Fabrication of an Air-Borne Flexible Piezoelectric Micromachined Ultrasonic Transducer. Sensors (Basel) 2020, 20. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.V.; Sadeghpour, S.; Kraft, M. Flexible PZT-Based Row-Column Addressed 2-D PMUT Array. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2024, 71, 1616-1626. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Lin, D. A Highly Flexible Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Sensor for Wearable Bone Density Testing. Micromachines (Basel) 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, K.; Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Kong, Y.; Wang, L.; Yi, F.; Sang, Y.; Li, G.; et al. Ultrasound-activated piezoelectric nanostickers for neural stem cell therapy of traumatic brain injury. Nat Mater 2025, 24, 1137-1150. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Quan, Y.; Xing, J.; Tan, Z.; Sun, X.; Lou, L.; Fei, C.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Y. Lead-Free Potassium Sodium Niobate-Based Wearable Ultrasonic Patches for Blood Pressure Detection. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Debnath, S.; Mahipal Malappuram, K.; Parasuram, S.; Chang, H.T.; Chatterjee, K.; Nain, A. Flexible and Robust Piezoelectric Chitosan Films with Enhanced Bioactivity. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 1128-1140. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, W.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z. An Easy Nanopatch Promotes Peripheral Nerve Repair through Wireless Ultrasound-Electrical Stimulation in a Band-Aid-Like Way. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, H.; Qi, Q.; Tong, Z.; Rong, D.; Zhou, Z. Design and characteristic analysis of flexible CNT film patch for potential application in ultrasonic therapy. Nanotechnology 2023, 34. [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, C.D.; Cretu, E.; Rohling, R. Fabrication and testing of polymer-based capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers for medical imaging. Microsyst Nanoeng 2018, 4, 19. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Ye, W.; Luan, S.; Wang, L.; Shi, H. Tenon-and-Mortise Structure-Inspired MOF/PVDF Composites with Enhanced Piezocatalytic Performance via Dipole-Engineering Strategy. Small 2025, 21, e2409314. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, T.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, R.; He, Q.; Luo, J.; Li, J.; Du, K.; Wu, T.; et al. A low-voltage-driven MEMS ultrasonic phased-array transducer for fast 3D volumetric imaging. Microsyst Nanoeng 2024, 10, 128. [CrossRef]

- Gami, P.; Roy, T.; Liang, P.; Kemper, P.; Travagliati, M.; Baldasarre, L.; Bart, S.; Konofagou, E.E. In Vivo Characterization of Central Arterial Properties Using a Miniaturized pMUT Array Compared to a Clinical Transducer: A Feasibility Study Towards Wearable Pulse Wave Imaging. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2025, Pp. [CrossRef]

- Pashaei, V.; Dehghanzadeh, P.; Enwia, G.; Bayat, M.; Majerus, S.J.A.; Mandal, S. Flexible Body-Conformal Ultrasound Patches for Image-Guided Neuromodulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2020, 14, 305-318. [CrossRef]

- Huan, J.; Pashaei, V.; Majerus, S.J.A.; Bhunia, S.; Mandal, S. A Wearable Dual-Mode Probe for Image-Guided Closed-Loop Ultrasound Neuromodulation. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2025, 19, 357-373. [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Shi, C.; Tien, K.; Elloian, J.; Cardoso, F.A.; Shepard, K.L. An Integrated 2D Ultrasound Phased Array Transmitter in CMOS With Pixel Pitch-Matched Beamforming. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2021, 15, 731-742. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Agrawal, S.; Osman, M.; Minotto, J.; Mirg, S.; Liu, J.; Dangi, A.; Tran, Q.; Jackson, T.; Kothapalli, S.R. A Transparent Ultrasound Array for Real-Time Optical, Ultrasound, and Photoacoustic Imaging. BME Front 2022, 2022, 9871098. [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhang, L.; Suh, E.; Lin, D.; Marcus, C.; Ozkan, L.; Ahuja, A.; Fernandez, S.; Shuvo, II; Sadat, D.; et al. Conformable ultrasound breast patch for deep tissue scanning and imaging. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadh5325. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, R.; Qin, S.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Han, G.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Skin-adaptive focused flexible micromachined ultrasound transducers for wearable cardiovascular health monitoring. Sci Adv 2025, 11, eadw7632. [CrossRef]

- Ngo, O.; Niemann, E.; Gunasekaran, V.; Sankar, P.; Putterman, M.; Lafontant, A.; Nadkarni, S.; DiMaria-Ghalili, R.A.; Neidrauer, M.; Zubkov, L.; et al. Development of Low Frequency (20-100 kHz) Clinically Viable Ultrasound Applicator for Chronic Wound Treatment. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2019, 66, 572-580. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, W.; Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X. Flexible Ultrasonic Patch for Accelerating Chronic Wound Healing. Adv Healthc Mater 2021, 10, e2100785. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Sun, M.; Bu, Y.; Luo, F.; Lin, C.; Lin, Z.; Weng, Z.; Yang, F.; Wu, D. Microcapsule-embedded hydrogel patches for ultrasound responsive and enhanced transdermal delivery of diclofenac sodium. J Mater Chem B 2019, 7, 2330-2337. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, Z.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S.; Tang, C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Sui, C.; Ding, C.; et al. 3D printed multi-coupled bioinspired skin-electronic interfaces with enhanced adhesion for monitoring and treatment. Acta Biomater 2024, 187, 183-198. [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Jin, J.; Huang, X.; Tan, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, G.; Hu, X.; Chen, K.; Su, Y.; Hu, X.; et al. Wearable flexible ultrasound microneedle patch for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 2650. [CrossRef]

- Sempionatto, J.R.; Lin, M.; Yin, L.; De la Paz, E.; Pei, K.; Sonsa-Ard, T.; de Loyola Silva, A.N.; Khorshed, A.A.; Zhang, F.; Tostado, N.; et al. An epidermal patch for the simultaneous monitoring of haemodynamic and metabolic biomarkers. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 5, 737-748. [CrossRef]

- Amado-Rey, A.B.; Goncalves Seabra, A.C.; Stieglitz, T. Towards Ultrasound Wearable Technology for Cardiovascular Monitoring: From Device Development to Clinical Validation. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng 2025, 18, 93-112. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, X.; Yue, W.; Mu, J.; Lou, Z.; Zhang, R.; Shi, K.; Chen, X.; et al. A photoacoustic patch for three-dimensional imaging of hemoglobin and core temperature. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7757. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, C.; Li, F. Wearable ultrasound regulation of blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Ultrasonics 2025, 155, 107739. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xie, J.; Yang, L.; Cui, Y. An intelligent wearable artificial pancreas patch based on a microtube glucose sensor and an ultrasonic insulin pump. Talanta 2024, 273, 125879. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.S.M.; Namazi, N.; Elbadawy, H.M.; El-Sayed, A.A.A.; Ahmed, S.A.; Bafail, R.; Almikhlafi, M.A.; Alahmadi, Y.M. Repaglinide-Solid Lipid Nanoparticles in Chitosan Patches for Transdermal Application: Box-Behnken Design, Characterization, and In Vivo Evaluation. Int J Nanomedicine 2024, 19, 209-230. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, G.; Ma, Z.; Qin, S. Ultrasound-assisted transdermal delivery of alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis. Acta Biochim Pol 2020, 67, 173-179. [CrossRef]

- Bok, M.; Zhao, Z.J.; Hwang, S.H.; Jeong, Y.; Ko, J.; Ahn, J.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, S.; Jeong, J.H. Biocompatible All-in-One Adhesive Needle-Free Cup Patch for Enhancing Transdermal Drug Delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021, 13, 58220-58228. [CrossRef]

- Bok, M.; Zhao, Z.J.; Jeon, S.; Jeong, J.H.; Lim, E. Ultrasonically and Iontophoretically Enhanced Drug-Delivery System Based on Dissolving Microneedle Patches. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 2027. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Kai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Piezoelectric-Driven Microneedle Array Delivery of Methotrexate for Enhanced Psoriasis Treatment. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2025, 11, 4515-4522. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Shang, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; An, Q.; Feng, Z. Microbubble-Enhanced Transdermal Drug Delivery Sonoelectric Patch. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 49069-49082. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, J.; Shende, P. Potential of Sonophoresis as a Skin Penetration Technique in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Transdermal Patch. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 180. [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Zhang, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Ding, C.; Xu, G. Inhibitory effect of ultrasonic stimulation on the voltage-dependent potassium currents in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. BMC Neurosci 2019, 20, 3. [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.L.; Firouzi, K.; Khuri-Yakub, B.T.; Madison, D.V.; Maduke, M. Spike frequency-dependent inhibition and excitation of neural activity by high-frequency ultrasound. J Gen Physiol 2020, 152. [CrossRef]

- Sorum, B.; Docter, T.; Panico, V.; Rietmeijer, R.A.; Brohawn, S.G. Pressure and ultrasound activate mechanosensitive TRAAK K (+) channels through increased membrane tension. bioRxiv 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sorum, B.; Docter, T.; Panico, V.; Rietmeijer, R.A.; Brohawn, S.G. Tension activation of mechanosensitive two-pore domain K+ channels TRAAK, TREK-1, and TREK-2. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3142. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.Y.; Chen, Y.M.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Hu, J.Q.; Tang, W.X.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Xue, L. L-Type Calcium Channel Modulates Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound-Induced Excitation in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Neurosci Bull 2024, 40, 921-936. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jiang, H.; Lin, J.; Qiao, C.; Augustine, G.J. Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Activates Excitatory Synaptic Networks in Cultured Hippocampal Neurons. Ultrasound Med Biol 2025, 51, 1250-1260. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Meng, L.; Zou, J.; Zhou, W.; Huang, X.; Xue, S.; Bian, T.; Yuan, T.; Niu, L.; Guo, Y.; et al. Non-invasive ultrasonic neuromodulation of neuronal excitability for treatment of epilepsy. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5514-5526. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Tan, D.; Wang, Y.; Gong, C.; Yuan, J.; Yang, X.; Wen, Y.; Ban, Y.; Liang, M.; Hu, Y.; et al. Targeted sonogenetic modulation of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampal CA1 region in status epilepticus. Theranostics 2024, 14, 6373-6391. [CrossRef]

- Zou, F.; Liu, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xu, T. A wearable spatiotemporal controllable ultrasonic device with amyloid-β disaggregation for continuous Alzheimer's disease therapy. Sci Adv 2025, 11, eadw1732. [CrossRef]

- Siboro, P.Y.; Sharma, A.K.; Lai, P.J.; Jayakumar, J.; Mi, F.L.; Chen, H.L.; Chang, Y.; Sung, H.W. Harnessing HfO(2) Nanoparticles for Wearable Tumor Monitoring and Sonodynamic Therapy in Advancing Cancer Care. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 2485-2499. [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Kang, J.; Wei, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, B.; Lu, Q.; Li, H.; Yan, J.; Yang, X.; et al. A pH responsive nanocomposite for combination sonodynamic-immunotherapy with ferroptosis and calcium ion overload via SLC7A11/ACSL4/LPCAT3 pathway. Exploration (Beijing) 2025, 5, 20240002. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lou, X.; Sutrisno, L.; Peng, S.; Li, J. Oxygen-carrying semiconducting polymer nanoprodrugs induce sono-pyroptosis for deep-tissue tumor treatment. Exploration (Beijing) 2024, 4, 20230100. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Wu, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, H. Manganese carbonate nanoparticles-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction for enhanced sonodynamic therapy. Exploration (Beijing) 2021, 1, 20210010. [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Kim, Y.M.; Lee, T.; Lee, S.M.; Jung, J.; Bae, H.M.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.J. Patch-type capacitive micromachined ultrasonic transducer for ultrasonic power and data transfer. Microsyst Nanoeng 2025, 11, 124. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, C.H.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Gu, Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Ou-Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhu, B. A Self-Healing Optoacoustic Patch with High Damage Threshold and Conversion Efficiency for Biomedical Applications. Nanomicro Lett 2024, 16, 122. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).