1. Introduction

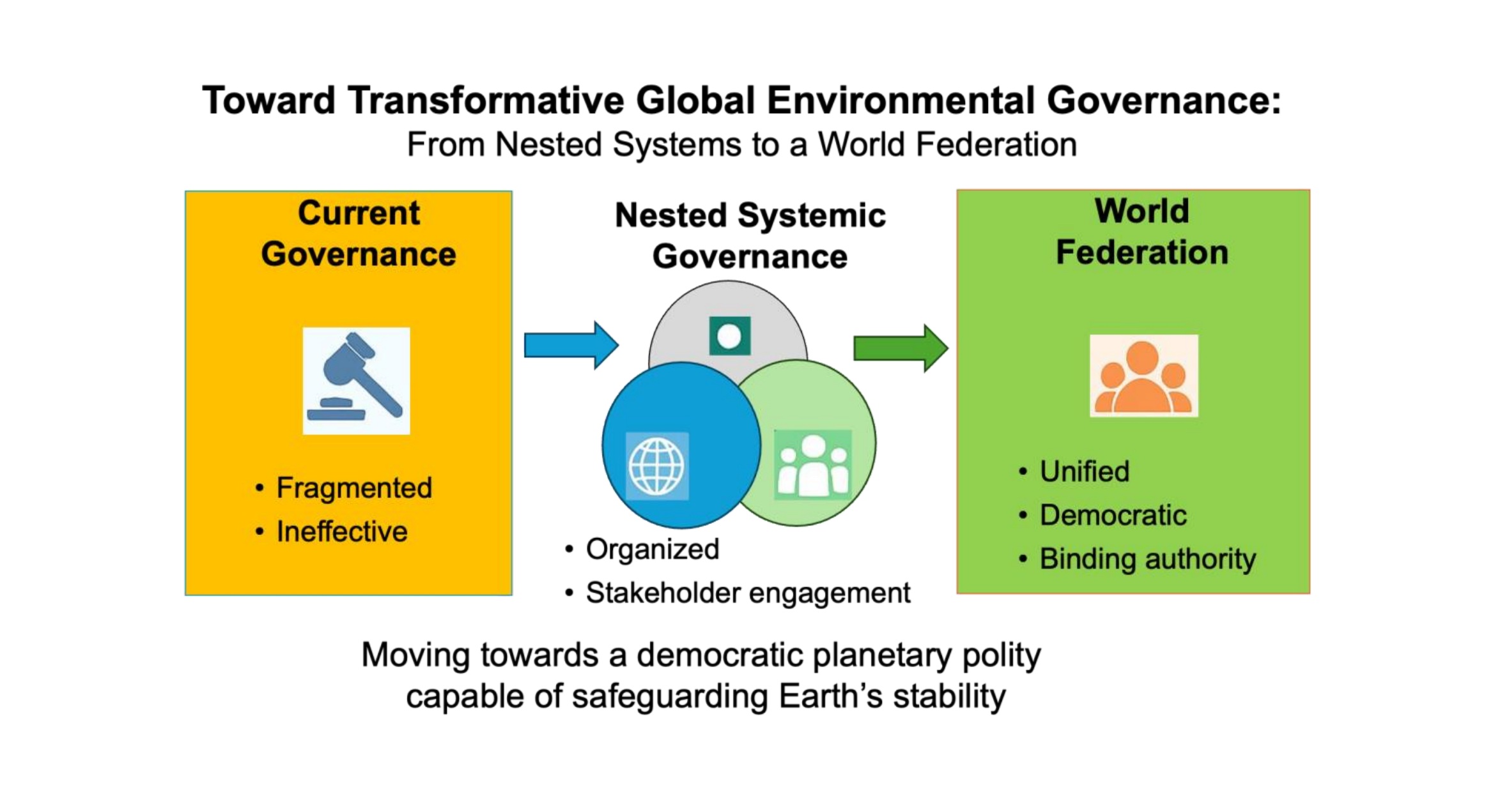

Global environmental governance has reached an inflection point. As the destabilizing pressures of the Anthropocene intensify—from accelerating biodiversity loss and planetary boundary transgressions to cascading climate risks—the institutional architecture of global governance continues to display profound limitations [

1,

2]. Despite a vast proliferation of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) since the 1970s, the overall system remains fragmented, weakly coordinated, and hamstrung by persistent sovereignty-based constraints [

3,

4]. The gap between ecological necessity and political capacity widens each year.

Long-standing reform proposals such as the creation of a World Environment Organization (WEO) or a United Nations Council on Sustainable Development (CSD) have sought to streamline coordination, rectify institutional incoherence, and elevate environmental concerns within the international system [

5,

6]. Yet while these proposals promise incremental improvements, they risk entrenching the same structural deficits that characterize the UN system today—namely voluntary compliance, uneven enforcement, and the subordination of planetary interests to geopolitical bargaining.

In recent years, scholars of global governance have increasingly turned to polycentric and adaptive models, most notably Nested Systemic Governance (NSG), which organizes governance functions across clusters, hubs, and multi-level participatory forums [

7,

8]. NSG holds promise as a flexible framework capable of coordinating diverse actors while fostering experimentation and learning. However, NSG remains ultimately constrained by the deeper problem of state-centric world order. Without binding constitutional foundations, NSG’s ability to deliver planetary-scale public goods—climate stabilization, biosphere protection, and equitable resource governance—remains limited.

This article evaluates these competing approaches and advances a different pathway: a gradual, evolutionary transition from NSG toward a constitutionally grounded World Federation. Drawing on emerging debates in planetary politics, global constitutionalism, and Earth system governance, it argues that only a federative framework—rooted in a legitimate World Constitution—can reconcile democratic accountability, enforceable obligations, and structural authority at the planetary scale [

9,

10,

11]. While politically ambitious, such a trajectory provides a coherent institutional horizon capable of addressing the magnitude of the ecological crisis.

The argument proceeds in three steps. First, it analyzes the structural limitations of existing global environmental governance and the partial reforms commonly proposed. Second, it assesses NSG as an adaptive but ultimately insufficient model. Finally, it outlines an evolutionary constitutional pathway toward a World Federation capable of delivering genuinely transformative governance of the Earth system. In doing so, the article seeks to bridge the gap between pragmatic institutional design and normative aspirations for a sustainable, democratic planetary polity.

2. From Treaties to Complexity: The Evolution of the Global Environmental Regime

The modern international environmental regime took shape gradually in the post–World War II period, as states began negotiating treaties to address discrete ecological problems such as wildlife protection, pollution, and hazardous waste. The 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm marked a critical turning point: for the first time, environmental protection was formally recognized as a matter of global concern, and the conference catalyzed a wave of treaty-making that extended into subsequent decades. Early agreements—including the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the 1987 Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, and the 1992 Rio Conventions on biodiversity, climate change, and desertification—reflected an emerging recognition that global environmental challenges transcend national borders and require coordinated international responses.

During this foundational period, analysts emphasized that treaty effectiveness depended on the alignment—or “fit”—between specific environmental problems and the institutional mechanisms designed to address them [

12,

13]. This insight underscored both the promise and the inherent limitations of issue-specific treaties: while they could address targeted concerns, they struggled to cope with cross-cutting risks and the interconnected dynamics of the Earth system.

By the 1990s and 2000s, global environmental governance had evolved far beyond the treaty-based model. The proliferation of specialized UN agencies, transnational networks, public–private partnerships, certification schemes, and scientific assessment bodies contributed to what scholars increasingly described as a

polycentric and

multi-level governance system [

14,

15]. Frank Biermann and colleagues [

7,

16] conceptualized this emerging architecture through the framework of Earth System Governance, highlighting the challenge of steering coupled human–environment systems across multiple scales, actors, and issue domains.

Polycentric governance theory suggested that such diversity could enhance adaptability and innovation. Elinor Ostrom [

8] argued that polycentric systems—when effectively coordinated—can generate experimentation, local problem-solving capacity, and resilience in the face of environmental uncertainty. At the same time, however, scholars of regime complexity warned that institutional proliferation also created new governance challenges. Raustiala and Victor [

17] introduced the concept of a “regime complex” to capture the growing density of overlapping and partially autonomous institutions operating within the same issue area. Keohane and Victor [

18] further argued that such complexity, while unavoidable, often results in coordination gaps, contradictory mandates, and incentives for selective engagement.

Parallel research programs documented the rise of transgovernmental and transnational governance arrangements that further expanded the system’s complexity. Anne-Marie Slaughter [

19] described the emergence of transgovernmental regulatory networks involving judges, regulators, and policymakers who coordinate norms and practices across borders. Alter, Hafner-Burton, and Helfer [

20] traced the increasing influence of international courts and tribunals in shaping compliance dynamics and creating legal interdependencies between regimes. Abbott and Snidal [

21] analyzed the growth of transnational public–private regulatory initiatives that have become central to environmental standard-setting and implementation.

By the early twenty-first century, what began as a treaty-centered regime had transformed into a dense, multi-actor, and polycentric global governance landscape. This institutional expansion broadened participation, produced pockets of innovation, and diversified pathways for environmental cooperation. Yet it also intensified fragmentation, a problem now widely recognized in the field. Fragmentation manifests in inconsistent norms, duplicative mandates, competition among institutions, and uneven accountability—conditions that collectively undermine the coherence and overall effectiveness of global environmental governance [

15,

22,

23].

Thus, the evolution from treaties to complexity has produced a governance architecture that is simultaneously richer and more fragile: rich in institutional diversity and actor participation, but fragile in its capacity to coordinate action across issue areas and scales. These tensions foreshadow the broader Earth system governance crisis confronting the international community today and set the stage for the debate between incremental reform and deeper constitutional transformation explored in the following sections.

3. From Expansion to Fragmentation: The Limits of Polycentricity

Since the 1972 Stockholm Conference and the establishment of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), global environmental governance has expanded at a remarkable pace. More than 1,800 multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) now populate the international landscape, supplemented by a dense array of UN bodies, scientific panels, transnational partnerships, certification schemes, and private standard-setters [

24]. Landmark instruments such as the Montreal Protocol, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and the Paris Agreement demonstrate how this expansion has produced important normative commitments and technical capabilities. Yet the cumulative result is not a coherent architecture but a polycentric mosaic marked by fragmentation, overlap, and uneven authority.

Polycentric governance theory—most prominently advanced by Elinor Ostrom [

8]—suggests that dispersed authority can foster experimentation, local innovation, and resilience. However, environmental governance scholars have increasingly questioned whether these benefits hold at the global level under conditions of accelerating planetary crisis. Biermann et al. [

15] showed that the environmental regime complex is fragmented across functional, institutional, and normative dimensions, while Keohane and Victor [

18] argued that polycentricity in climate governance has produced “regime complexes” with significant coordination problems. As Zürn and Faude [

23] emphasize, fragmented architectures can generate inter-institutional conflict and gaps in steering capacity—especially where no overarching authority exists to align efforts.

The Paris Agreement exemplifies both the potential and the limits of this model. Lauded as a diplomatic breakthrough in 2015, the Agreement’s architecture rests on nationally determined contributions (NDCs) embedded in a voluntary “pledge-and-review” system. Yet the first Global Stocktake [

25] confirmed that aggregated pledges remain incompatible with the 1.5°C trajectory and lack credible enforcement mechanisms. Similarly, the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework [

26] introduced ambitious global targets, but continues to rely on non-binding national commitments, underfunded implementation instruments, and insufficient mechanisms for monitoring and compliance.

These patterns are not isolated failures but reflect three structural governance deficits that recur across the global environmental regime:

3.1. Coordination Gaps

Issue-specific MEAs address deeply interconnected problems—land use, biodiversity loss, climate change, freshwater systems, and pollution—yet often operate in isolation. Institutional overlap has produced redundancies, inconsistent standards, and cross-regime externalities [

22]. Attempts at orchestration by UNEP, the UNFCCC, or the High-Level Political Forum remain limited by weak mandates and inadequate authority [

27].

3.2. Compliance Deficits

Most environmental treaties lack strong compliance bodies or binding enforcement. The Paris Agreement’s enhanced transparency framework relies primarily on soft mechanisms—peer review, reputational incentives, and “naming and shaming”—whose effectiveness remains contested [

28,

29]. Biodiversity and chemical regimes fare similarly, with implementation dependent on domestic political will, national capacity, and donor priorities rather than institutional constraint [

30,

31].

3.3. Legitimacy Shortfalls

Global environmental governance continues to suffer from structural imbalances in participation and representation. Civil society organizations, Indigenous peoples, and local communities remain marginalized in agenda-setting and decision-making, despite being disproportionately affected by environmental harms. Deep-rooted North–South divisions over historical responsibility, finance, and technology transfer exacerbate mistrust and hinder cooperation [

32,

33]. These legitimacy deficits undermine the social foundations of compliance and weaken the authority of global institutions.

The result is a governance system that is simultaneously expansive and ineffective: a patchwork that produces ambitious declarations but lacks the systemic coherence needed to steer humanity back within the planetary boundaries [

1,

2]. Without stronger coordination, credible compliance mechanisms, and more inclusive and equitable decision-making structures, polycentricity risks becoming less an asset than a euphemism for institutional disorder. In its current form, the global environmental regime multiplies efforts but diffuses responsibility, generating activity without achieving the scale of transformation that the Earth system crisis demands.

4. Nested Systemic Governance: A Pragmatic but Incomplete Path

NSG has emerged as a leading proposal for reorganizing today’s fragmented environmental governance landscape into more coherent architectures of cooperation [

14]. Rather than replacing the existing regime complex, NSG seeks to cluster related issue-areas—such as climate and energy, biodiversity and land, oceans and fisheries, and chemicals and waste—under the coordinating authority of a Global Environment Council. Within this framework, three design elements are especially salient.

First, regional hubs would translate global norms into context-sensitive policies, helping states align domestic strategies with instruments such as the Paris Agreement’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework. Second, assessment offices—institutionalized analogues to the IPCC [

34] and IPBES [

35]—would enhance monitoring, reporting, and review across policy domains, reducing duplication while improving scientific coherence. Third, participatory assemblies would broaden stakeholder representation, strengthening the procedural legitimacy of global environmental decision-making and responding to long-standing critiques regarding the marginalization of civil society and Indigenous peoples [

33].

The underlying rationale of NSG is explicitly transitional. By structuring governance from the bottom up, NSG reflects a foundational federal principle: centripetal authority formation, in which constituent units—national or regional—establish shared institutions with competencies limited to clearly defined common interests. In this sense, NSG offers a pragmatic pathway for moving the international system incrementally toward a more integrated and potentially constitutionalized order.

Building on existing mechanisms—such as the Paris Agreement’s transparency framework and the Convention on Biological Diversity’s system of national strategies and action plans—NSG aims to weave disparate processes into a more coordinated whole. The approach promises tangible short-term gains in coherence, implementation, and accountability.

Yet NSG’s strengths also reveal its central limitation. Its effectiveness ultimately depends on voluntary cooperation and, therefore, on the continued primacy of national sovereignty. Without binding compliance or shared authority—without “the parts” collectively empowering “the whole”—NSG cannot fully resolve the entrenched structural deficits of treaty-based governance. Coordination, no matter how sophisticated, remains vulnerable to fluctuating national priorities, geopolitical tensions, and crisis-induced retrenchment.

This constraint is not unique to NSG; it reflects a broader historical pattern. Treaty-based cooperation has repeatedly shown fragility when confronted with systemic shocks or competing state interests. NSG may consolidate progress and strengthen institutional foundations, but it cannot, on its own, deliver the structural transformation required for governing a rapidly destabilizing Earth system.

5. The Limits of Treaty-Based Cooperation: Lessons from History

The fragility of treaty-based cooperation is not unique to environmental governance; it is a recurring feature of international politics. Across modern history, institutional frameworks grounded solely in treaties have repeatedly proven inadequate for constraining the pursuit of national interests, particularly during times of crisis.

The League of Nations (1919–1946) embodied post–World War I ambitions to prevent future conflict by establishing collective rules for peace and security. Yet its reliance on voluntary compliance proved fatal. Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia in 1935 went largely unanswered, revealing the League’s profound inability to restrain aggression or enforce its own principles [

36,

37]. When obligations clashed with national priorities, states simply ignored or abandoned the institution altogether, and its erosion ultimately paved the way to World War II.

The United Nations, created in 1945 to overcome the weaknesses of its predecessor, introduced new mechanisms for collective security. However, its treaty foundation continues to impose structural constraints. The Security Council’s veto power allows any permanent member to block action—even in the face of clear violations of international law. Although Article 6 of the UN Charter technically authorizes the expulsion of states that persistently violate Charter principles, it has never been invoked because expulsion itself requires Security Council approval, where a veto by any permanent member is decisive [

38]. In practice, powerful states and their allies have shielded themselves from accountability, undermining both the UN’s legitimacy and the effectiveness of its enforcement capacity [

39].

Even the European Union, widely regarded as the most sophisticated experiment in supranational law and regional integration, demonstrates similar limitations. Despite having its own legal order and institutions that transcend national boundaries, the EU remains fundamentally a union of sovereign states. Moments of acute stress—the Eurozone debt crisis, the 2015 migration emergency, and the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the Union—exposed the fragility of this architecture: when collective rules appear incompatible with national political imperatives, member states can obstruct implementation, reinterpret obligations, or, as Brexit demonstrated, exit the system entirely [

40].

Together, these cases illustrate a consistent historical pattern: treaty-based systems tend toward institutional entropy. They can facilitate cooperation during stable periods, but without constitutional grounding—indeed, without a federal structure capable of allocating authority and enforcing compliance—such systems lack the durability, accountability, and resilience required for navigating systemic shocks. For global environmental governance, the lesson is sobering. Unless the international community moves beyond treaties toward a constitutionally anchored federal framework, even the most ambitious initiatives risk replicating the failures of the League, the structural constraints of the UN, and the periodic fragility of the EU [

41].

This fragility has become even more pronounced in today’s geopolitical context. The rise of illiberalism, democratic erosion, and resurgent nationalism threatens not only the capacity of existing institutions to cooperate, but also the normative foundations of multilateralism itself. The contemporary challenge is therefore not solely institutional but ideological: a shifting political landscape in which support for collective governance is eroding. Recognizing this dynamic is essential for envisioning any viable path toward a global environmental constitution.

6. The Challenge of Illiberalism in the Emerging Global Order

The prospects for transformative global environmental governance cannot be understood apart from the broader geopolitical context, which is increasingly shaped by the rise of illiberal and exclusionary forms of politics. Often framed in the language of national sovereignty, cultural preservation, or “national greatness,” these movements systematically erode the multilateral and science-based cooperation on which meaningful environmental governance depends. The most emblematic example has been the resurgence of Trumpism in the United States, but similar dynamics are unfolding across numerous regions.

The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, its hostility toward climate science, and its transactional approach to diplomacy exemplified not merely policy divergence but a deliberate repudiation of global cooperative norms. This pattern is part of a broader trend: the global normalization of autocratic legalism, in which democratic institutions are weakened through seemingly lawful but fundamentally anti-democratic means [

42]. As Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue [

43], the erosion of guardrails such as mutual toleration and institutional forbearance enables leaders to consolidate power while hollowing out democratic accountability.

Illiberal politics frequently combine nationalist rhetoric with extractivist economic agendas, skepticism toward scientific expertise, and hostility toward climate or biodiversity commitments. Examples span multiple regions: the Orbán government in Hungary, Bolsonaro-era Brazil, and even some political coalitions within parts of the European Union have challenged environmental protections, sidelined scientific bodies, and reasserted state-centric control over natural resources [

44,

45,

46]. These shifts undermine international trust and deepen existing North–South divides, making consensus on ambitious environmental reforms more elusive.

The geopolitical consequences are profound. By empowering obstructionist states and weakening rules-based cooperation, illiberalism constrains the very mechanisms—collective action, long-term commitments, and binding obligations—that global environmental governance requires. As a result, polycentric and treaty-based arrangements become even more vulnerable to stalemate, non-compliance, and political backsliding.

Yet the rise of illiberalism may also generate unexpected opportunities for institutional innovation. As established global institutions lose legitimacy or fail to respond effectively to democratic decay and planetary crises, civil society networks, progressive states, and transnational movements may find renewed momentum to advocate for systemic alternatives. The delegitimization of existing structures can catalyze calls for a more durable, enforceable, and democratically grounded order—one based not on voluntary commitments but on constitutional authority. What once appeared utopian—the notion of a World Federation—may increasingly be framed as a pragmatic response to escalating governance failures.

As the shortcomings of treaty-based multilateralism intensify under geopolitical strain, the intellectual and practical case for a constitutionalized global authority grows stronger. Advancing research into transitional mechanisms—such as NSG—will therefore be crucial, both for strengthening existing institutions and for charting feasible pathways toward a federal planetary polity.

Meeting the challenge of illiberalism requires more than incremental adjustments within the current treaty system. It demands confronting the deeper structural deficits of compliance, legitimacy, and accountability that allow illiberal actors to paralyze international cooperation. This is precisely where the idea of a world constitutional federation gains traction: as a framework capable of transcending both the fragmentation of polycentric governance and the vulnerabilities of treaty-based cooperation.

The rise of illiberalism underscores a decisive truth: the sustainability of global cooperation cannot rest on voluntary pledges or fragmented networks alone. The Anthropocene has revealed that global ecological interdependence requires political and legal integration of comparable depth. What is now required is not another layer of coordination, but a transformation in constitutional form—a shift from intergovernmental governance to federal government at the planetary scale.

7. A World Federation

Proponents of a World Federation argue that polycentric coordination—while valuable for experimentation and learning—cannot overcome the deep structural deficits of legitimacy, compliance, and accountability that plague contemporary environmental governance [

3,

7,

8]. Polycentric networks of states, international organizations, and civil society actors can generate innovation, but they lack the authority to impose binding obligations or ensure compliance when vital collective interests are at stake. This limitation becomes particularly acute in the Anthropocene, where planetary interdependence demands governance capacities that exceed those available within voluntary, treaty-based frameworks [

47].

To address this gap, a growing body of scholarship calls for a world constitutional federation—a political and legal transformation grounded in a democratically legitimated World Constitution [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Building on earlier debates about cosmopolitan democracy [

52,

53] and more recent interventions in global constitutionalism [

54,

55], these proposals envision an institutional architecture capable of reconciling planetary environmental limits with democratic self-governance.

Such a constitution would establish:

A World Parliament, representing both citizens and states, thereby combining the democratic legitimacy of popular representation with the cooperative functions of interstate governance [

11].

A World Executive, organized into ministries with defined portfolios—including global climate policy, biodiversity conservation, sustainable energy, and ecological restoration—improving coherence across policy domains that are currently fragmented across treaties and agencies [

56].

A World Judiciary, empowered to interpret sustainability norms, adjudicate disputes among states, corporations, and individuals, and enforce binding ecological obligations through judicial review.

An Ombudsmus Council (Quarta Politica), tasked with protecting individuals and communities from governmental failures and strengthening democratic oversight across global institutions [

57].

A World Federation would thus constitutionalize what is today voluntary, transforming weakly enforced commitments into binding obligations backed by legitimate authority. For example, the Paris Agreement’s nationally determined contributions (NDCs)—presently self-declared and politically nonbinding—could become enforceable emissions caps subject to oversight by a World Court of the Environment. Likewise, global biodiversity targets could be converted into justiciable duties, requiring states and corporations to protect ecosystems and species under penalty of international sanction [

58].

A central feature of this transformation is the construction of a legal system capable of addressing the complexity of Earth system dynamics. Traditional international law, anchored in state sovereignty and voluntary compliance, has proven inadequate for governing climate change, biodiversity collapse, and other transboundary threats [

59]. Scholars such as Louis J. Kotzé and Rakhyun E. Kim [

60] have therefore advanced the concept of Earth System Law: an integrated legal paradigm that recognizes the Earth as a single, interdependent socio-ecological system and designs norms accordingly. Embedding Earth System Law within a federal constitution would allow global governance to move beyond fragmented, sector-specific treaties and toward a holistic legal framework aligned with planetary boundaries.

Constitutionalization would also enhance the legitimacy of global environmental governance. Rather than relying on technocratic coordination or voluntary market incentives, compliance would rest on democratically legitimated institutions, binding legal authority, and judicial enforceability. Fundamental principles—intergenerational justice, ecological integrity, the safeguarding of planetary boundaries—could be entrenched as constitutional norms, ensuring that environmental protection is not subordinated to short-term economic or political interests [

61].

In this sense, a World Federation is not an abstract utopian project but a concrete institutional proposal aimed at resolving the core deficits of enforcement, legitimacy, and accountability in global governance. This model gains credibility when situated within the broader spectrum of reform proposals. Between today’s fragmented multilateralism and a fully constitutionalized federation lies a transitional paradigm—NSG—which seeks to integrate and coordinate existing institutions without consolidating them into a single polity [

62].

The question, therefore, is not whether the World Federation vision must replace polycentric or nested approaches, but how these models may function along a single evolutionary continuum. NSG may serve as a pragmatic bridge toward constitutional federalism, gradually harmonizing institutions and legal regimes while creating pathways for democratic participation and accountability. The next section compares these approaches to assess their respective strengths and limitations—and to explore how each might contribute to transformative Earth system governance in an era of escalating planetary crisis.

8. Comparing Nested Systems and Federal Integration

The preceding section argued that a World Federation offers a constitutional architecture capable of resolving the deep compliance and legitimacy deficits that characterize today’s fragmented global environmental governance. Yet a constitutional federation is not the only model proposed to address these challenges. Building on polycentric insights [

8], institutional interplay theory [

3], and debates within Earth system governance [

7,

47], NSG has emerged as a pragmatic strategy for improving coherence within the existing treaty-based order. Rather than replacing the current system, NSG seeks to reorganize it into more functional clusters coordinated by a Global Environment Council [

62]—thus mitigating fragmentation without demanding a revolutionary break with state sovereignty.

This analytical landscape suggests that the models of NSG and World Federation should not be seen as competing paradigms, but rather as different stages within a broader evolutionary spectrum of institutional transformation. Echoing Polybius’ concept of

anakyklosis—the cyclical renewal of political orders—one may interpret NSG as a transitional architecture that stabilizes and rationalizes the existing system, while a World Federation represents the constitutional culmination of this integrative trajectory. This perspective aligns with work on institutional dynamism and long-term governance evolution in the Anthropocene [

63,

64], which emphasizes that governance transformations often emerge through iterative adjustments before consolidating into coherent constitutional frameworks.

Table 1 compares the status quo, NSG, and World Federation across six core institutional dimensions. The contrast illustrates both their continuities and their fundamental differences.

The comparison demonstrates that NSG significantly enhances coordination and inclusiveness within the multilateral system, in line with scholarship emphasizing adaptive, experimentalist, and networked governance [

65]. NSG’s emphasis on functional clusters, regional hubs, and participatory assemblies corresponds to “middle-ground” governance reforms advocated in the ESG literature [

7,

62,

66], aimed at reducing fragmentation without challenging the foundational primacy of state sovereignty.

However, the table also highlights that only a World Federation establishes the constitutional authority and binding enforcement necessary for transformative environmental governance, consistent with arguments in global constitutionalism [

54], Earth System Law [

60], and normative theories of planetary justice [

67]. While NSG can strengthen accountability through monitoring and review, it cannot compel compliance when domestic political priorities diverge from global environmental imperatives—an issue repeatedly emphasized in governance effectiveness research [

18,

68].

Nevertheless, these models need not be understood as mutually exclusive. Instead, NSG may operate as transitional scaffolding for federal integration, providing a governance laboratory that enables institutional learning, stakeholder participation, and gradual alignment of norms and practices. Several evolutionary pathways illustrate this potential:

Clusters as Federal Ministries: Functional clusters within NSG could be consolidated into ministries of a future World Executive, reducing duplication and improving coherence across policy domains.

Regional Hubs as Federated Regions: NSG’s regional hubs—already tasked with adapting global norms to local realities—could evolve into semi-autonomous federal regions within a constitutional federation, balancing subsidiarity with global oversight.

Participatory Assemblies as Parliamentary Chambers: Multistakeholder deliberative bodies could be institutionalized as chambers within a bicameral World Parliament, expanding democratic legitimacy beyond state governments.

Assessment Offices as Oversight Institutions: NSG’s monitoring and review mechanisms could form the basis for a constitutionally empowered World Auditor-General for Sustainability, ensuring transparency and accountability.

Viewing NSG and World Federation as elements of a continuum of institutional evolution provides a synthetic perspective that avoids the false dichotomy between incrementalism and constitutionalism. NSG contributes immediate gains in coherence, stakeholder participation, and adaptive capacity. A World Federation, in turn, provides the constitutional enforceability, democratic legitimacy, and legal integration required to align global governance with the demands of planetary boundaries and intergenerational justice.

Yet this evolutionary path remains contested. Diverse reformist, experimentalist, and imaginative alternatives populate the Earth system governance landscape—from strengthened UN environmental institutions to global green constitutionalism, Earth System Law, and post-sovereign cosmopolitan models. Before embracing a World Federation as the ultimate horizon of institutional evolution, it is necessary to situate it within these competing visions and assess its comparative feasibility and normative desirability.

9. Global Governance Alternatives

As the preceding section argued, the comparative limitations of NSG and the strengths of a constitutionally grounded World Federation suggest an evolutionary pathway toward more integrated, enforceable, and democratic global environmental governance. Yet before embracing a World Federation as the ultimate horizon of institutional evolution, it is necessary to engage with alternative proposals that have shaped scholarly debates for decades. These models—some incremental, some visionary, others ontologically transformative—illuminate both the promise and the limits of reform within the prevailing international system.

Two of the most longstanding and institutionally pragmatic proposals are the creation of a World Environment Organization (WEO) and the establishment of a UN Council on Sustainable Development (CSD). Emerging as early as the 1970s and gaining visibility during the 1992 Rio Earth Summit and the 2002 Johannesburg Summit, the WEO proposal aimed to consolidate fragmented multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) into a coherent institutional core [

5,

6]. Advocates argue that a specialized organization could systematize global environmental rulemaking, strengthen coordination, and elevate ecological priorities within international politics (Biermann 2000). Yet critics caution that, absent constitutional authority, a WEO risks reproducing the deficiencies of the current system—weak enforcement, dependence on voluntary commitments, donor-driven agendas, and bureaucratic duplication [

32]. Rather than transforming global governance, a WEO might simply reorganize its existing limitations.

A second proposal—the UN Council on Sustainable Development (CSD)—gained momentum before the 2012 Rio+20 Conference, envisioned as a high-level body analogous to the Security Council or the Human Rights Council [

69]. Designed to integrate environmental, social, and economic pillars into global decision-making, the CSD was politically more feasible than a WEO. Nonetheless, as Biermann notes [

7], such councils remain structurally constrained by the UN system’s core features: the primacy of state sovereignty, politicized negotiations, and the lack of binding enforcement mechanisms. Without a constitutional framework, even elevated councils risk becoming symbolic forums rather than engines of systemic change.

In response to the realization that incremental reforms cannot meet the demands of the Anthropocene, more visionary alternatives have emerged. One influential proposal is the Earth System Council, articulated by Burke et al. [

70], which would represent not only states but also ecosystems, species, and Earth system science. Conceived as an epistemically plural body capable of transcending “the old bargaining rituals of diplomacy,” this council aimed to anchor decision-making in planetary-scale knowledge. Yet subsequent critiques—particularly from posthumanist and critical international relations scholars—warn that such designs may replicate liberal-cosmopolitan assumptions and reinforce epistemic hierarchies unless fundamentally reimagined [

71]. Without constitutional grounding, even ambitious planetary councils may inadvertently perpetuate the separation of nature and politics.

This debate reflects a broader imaginative and ontological turn in global environmental governance. Scholars increasingly emphasize that institutional transformation depends not only on organizational design but also on reimagining planetary futures. Moore and Milkoreit [

72] highlight the centrality of imagination in shaping political possibilities, while Oomen, Hoffman, and Hajer [

73] conceptualize techniques of futuring as socially performative practices structuring which futures become politically legitimate. Oomen [

74] warns that dominant technological imaginaries—such as solar radiation modification—can become naturalized as “inevitable,” narrowing democratic deliberation. Extending this critique, Hajer and Oomen [

75] argue that global environmental politics is often trapped within captured futures, where technocratic management displaces democratic transformation.

Parallel developments in international theory deepen this call for ontological renewal. Pan [

76] advances a quantum ontology of governance, describing a “holographic world” in which human, non-human, and planetary agencies are entangled across scales, dissolving traditional distinctions between domestic and international politics. Ellis et al. [

77] complement this view by advocating an aspirational approach to planetary futures, calling for institutions grounded in collective planetary responsibility rather than state-centric negotiation logics.

Taken together, these alternatives—whether institutional (WEO, CSD), visionary (Earth System Council), or ontological (quantum and aspirational governance)—offer invaluable insights into the evolving landscape of Earth system governance. Yet they ultimately fall short of resolving the structural deficits of legitimacy, enforcement, and constitutional authority that undermine global environmental governance. Incremental institutionalism, even when imaginatively expansive, cannot substitute for the deeper constitutional reconfiguration required to govern the Earth system as a shared political community. By contrast, a World Federation provides the institutional capacity to transform normative commitments into binding obligations, embed sustainability within a democratic constitutional order, and secure long-term planetary stewardship.

10. Conclusions

Global environmental governance remains locked in a structural paradox: despite an ever-expanding architecture of treaties, summits, and institutions, the world continues to exceed planetary boundaries. Decades of multilateral diplomacy have not halted ecological overshoot, revealing the limitations of a regime built on voluntary cooperation, fragmented mandates, and the diffuse authority of more than 500 multilateral environmental agreements. Far from producing coherence, institutional proliferation has entrenched what scholars describe as an institutional fragmentation trap—a condition in which complexity undermines both effectiveness and legitimacy.

Incremental reforms, such as proposals for a World Environment Organization or a UN Council on Sustainable Development, might improve visibility, streamline coordination, or elevate environmental priorities within existing political structures. Yet, as discussed in

Section 8 and

Section 9, these models remain circumscribed by the deeper constitutional and enforcement deficits of the current order. They cannot overcome the sovereignty-bound logic that hinders global cooperation, nor can they generate binding authority capable of ensuring compliance with climate and biodiversity targets.

NSG represents a more ambitious step, offering an adaptive, polycentric, and participatory architecture that enhances coherence and stakeholder engagement. Through functional clusters, regional hubs, and multistakeholder assemblies, NSG strengthens coordination while acknowledging the pluralism of contemporary governance. Yet it too remains ultimately dependent on voluntary state cooperation. Without legally binding authority, even the most innovative NSG mechanisms risk being subsumed by the same pathologies that have long limited multilateral environmentalism.

What is required, therefore, is not merely institutional adjustment but constitutional transformation. A World Federation, grounded in shared sovereignty and democratic legitimacy, provides the structural capacity to govern the Earth system as a unified whole. Such a federation would not abolish existing institutions; rather, it would integrate them within a coherent constitutional framework anchored in enforceable authority. Through a World Parliament, a World Executive, a World Judiciary, and an Ombudsmus Council as the Quarta Politica, a federated system would reconcile global effectiveness with democratic accountability, ensuring that sustainability norms possess not only ethical force but also legal standing.

As Manjana Milkoreit aptly argues, “We have the knowledge to prevent breaching climate tipping points—what we need is a kind of governance that matches the nature of this challenge” [

78]. A World Federation offers precisely this match: a constitutional order capable of transforming voluntary pledges into binding obligations, embedding planetary boundaries into enforceable law, and grounding environmental stewardship in a system of global democratic representation.

The transition from fragmented governance to nested coordination—and ultimately to constitutional federation—marks more than an institutional evolution; it signifies a civilizational reorientation in how humanity understands authority, sovereignty, and belonging in the Anthropocene. NSG can serve as a transitional scaffolding, preparing the normative and organizational ground for deeper constitutional integration, while a fully articulated World Federation represents the long-term horizon of transformative global environmental governance.

Advancing along this trajectory enables global governance to move beyond crisis management toward the constitutional stabilization of the Earth system. Doing so is essential not only for safeguarding planetary integrity but also for sustaining the conditions of democratic self-governance for future generations. In this sense, the emergence of a world constitutional order is not a utopian aspiration but a pragmatic necessity—one grounded in the recognition that a shared planet requires shared authority, shared responsibility, and shared democratic institutions.

Author Contributions

M. Galiñanes conceptualized the article, wrote the original draft, reviewed and carried out the editing of the manuscript. L. Klinkers reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rockström, J.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society 2009, 14, 32. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/.

- Steffen, W.; et al. Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet. Science 2015, 347(6223), 1259855. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855.

- Young, O.R. Beyond Regulation: Innovative Strategies for Governing Large Complex Systems. Sustainability 2017, 9, 938. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S.; Cashore, B. Complex Global Governance and Domestic Policies: Four Pathways of Influence. International Affairs 2012, 88, 585–604.

- Biermann, F.; Bauer, S. A World Environment Organization: Solution or Threat for Effective International Environmental Governance? Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005.

- Esty, D.C. Greening the GATT: Trade, Environment, and the Future. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 1994.

- Biermann, F. Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene. MIT Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Polycentric Systems for Coping with Collective Action and Global Environmental Change. Global Environmental Change 2010, 20, 550–557. [CrossRef]

- Patomäki, H. The Political Economy of Global Security: War, Future Crises and Changes in Global Governance. Routledge, 2011.

- Archibugi, D. The Global Commonwealth of Citizens: Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy. Princeton University Press, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.; Strauss, A. Toward Global Parliament. Foreign Affairs 2003, 82, 212–220.

- Young, O.R. International Governance: Protecting the Environment in a Stateless Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1994.

- Young, O.R. The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

- Najam, A.; Papa, M.; Taiyab, N. Global Environmental Governance: A Reform Agenda. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2006.

- Biermann, F.; et al. The Fragmentation of Global Governance Architectures: A Framework for Analysis. Global Environmental Politics 2009, 9, 14–40. [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Conca. J.J. Global Environmental Governance: Intersections of Science, Politics, and Policy. New York: Routledge, 2007.

- Raustiala, K.; Victor, D.G. The Regime Complex for Plant Genetic Resources. International Organization 2004, 58, 277–309. [CrossRef]

- Keohane, R.O.; Victor, D.G. The Regime Complex for Climate Change. Perspectives on Politics 2011, 9, 7–23. [CrossRef]

- Slaughter, A.-M. A New World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Alter, K.J.; Hafner-Burton, E.M.; Helfer, L.R. Theorizing the Judicialization of International Relations. International Studies Quarterly 2019, 63, 449–463. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Snidal, D. Strengthening International Regulation Through Transnational New Governance: Overcoming the Orchestration Deficit. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 2021, 42, 501–578. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vjtl/vol42/iss2/4.

- Oberthür, S.; Stokke, O.S. Managing Institutional Complexity: Regime Interplay and Global Environmental Change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

- Zürn, M.; Faude, B. On Fragmentation, Differentiation, and Coordination. Global Environmental Politics 2013, 13, 119–130.

- Chan, S.; et al. Reinvigorating International Climate Policy: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Nonstate Action. Global Policy 2015, 6, 466–473. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12294.

- UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). Technical Dialogue of the First Global Stocktake: Synthesis Report by the Co-Facilitators on the Technical Dialogue. Bonn: UNFCCC Secretariat. FCCC/SB/2023/9. 8 September 2023.

- CBD (Convention on Biological Diversity). Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022. https://www.cbd.int/gbf.

- Abbott, K.; Genschel, P.; Snidal, D.; Zangl, B. Orchestration: Global Governance through Intermediaries. In International Organizations as Orchestrators. pp. 3–36. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Dannenberg, A.; Lumkosky, M.; Carlton, E.K.; Victor D.G. Naming and Shaming as a Strategy for Enforcing the Paris Agreement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Raiser, K.; Çalı, B.; Flachsland, C. Understanding Pledge-and-Review: Learning from Analogies to the Paris Agreement Review Mechanisms. Climate Policy, Taylor & Francis Journals 2022, 22, 711-727. [CrossRef]

- CBD Secretariat. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. Summary for Policy Makers. Montreal, 2020. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/.

- Bothe, M. Compliance. Oxford Public International Law, 2010. https://opil.ouplaw.com/display/10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690/law-9780199231690-e46?d=%2F10.1093%2Flaw%3Aepil%2F9780199231690%2Flaw-9780199231690-e46&p=emailA2UFZfoC1cDL2&print.

- Najam, A. The Case against a New International Environmental Organization. Global Governance 2003, 9, 367–384.

- Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P. Global Environmental Governance: Taking Stock, Moving Forward. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2008, 33, 277–294. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Geneva: IPCC Secretariat, 2023.

- IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services). Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat, 2019.

- Claude, I.L. Swords into Plowshares: The Problems and Progress of International Organization. 4th ed. New York: Random House, 1971.

- Armstrong, D. The Rise of the International Organisation: A Short History. London: Macmillan, 1982.

- Mazower, M. Governing the World: The History of an Idea. New York: Penguin, 2012.

- Zacher, M.W.; Matthew, R.A. Liberal International Theory: Common Threads, Divergent Strands. In: Kegley, Charles, Jr. (ed.), Controversies in International Relations theory: Realism and the Neoliberal challenge. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995, pp. 107–150.

- Moravcsik, A. The European Constitutional Settlement. The World Economy 2008, 31, 158–183. [CrossRef]

- Schrijver, N.J. The Evolution of Sustainable Development in International Law: Inception, Meaning, and Status. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2008.

- Scheppele, K.L. Autocratic Legalism. University of Chicago Law Review 2018, 85, 545–583.

- Levitsky, S.; Ziblatt, D. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Menezes, R.G.; Barbosa Jr, R. Environmental governance under Bolsonaro: Dismantling institutions, curtailing participation, delegitimising opposition. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 2021, 15(2):229–247. [CrossRef]

- Krasznai Kovács, E.; Pataki, G. The Dismantling of Environmentalism in Hungary. In Politics and the Environment in Eastern Europe, 25–52. Cambridge (Eng.): Open Book Publishers, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ofstehage, A.; Wolford, W.; Borras, S.M. Contemporary Populism and the Environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2022, 47, 671–696. [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Pickering, J. The Politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Galiñanes, M.; Martin, G.T. Manifest for a World Federation—For Peace, Ecosystems Protection and Democracy —A Call to Action for All Global Citizens. Open Journal of Political Science 2024, 14, 640-652. [CrossRef]

- Galiñanes, M.; Klinkers, L. Constitution for a World Federation: A World Pact. Letrame Publisher, 2026.

- Martin, G.T. A Constitution for the Federation of Earth: With Historical Introduction, Commentary and Conclusion. Radford, VA: Institute for Economic Democracy Press, 2010.

- Falk, R. On Humane Governance: Toward a New Global Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995.

- Held, D. Democracy and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1995.

- Scholte, J.A. Reinventing Global Democracy. European Journal of International Relations 2014, 20, 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, G.; Ginsburg, T.; Halliday, T.C. Constitution-Making and Transnational Legal Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Lang, A.F. Jr.; et al. Handbook on Global Constitutionalism. 2nd edit. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023.

- Weiss, T.G.; Wilkinson, R. International Organization and Global Governance. 3rd ed. London; New York: Routledge, 2023.

- Galiñanes, M.; Klinkers, L. Reimagining Checks and Balances: Establishing the Ombudmus Council as Quarta Politica in Democratic Governance. London Journal of Research in Humanities & Social Sciences 2025, 25, 43-51. https://journalspress.com/LJRHSS_Volume25/Reimagining-Checks-and-Balances-Establishing-the-Ombudmus-Council-as-Quarta-Politica-in-Democratic-Governance.pdf.

- Kotzé, L.J. Earth System Law for the Anthropocene. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6796. [CrossRef]

- Pauwelyn, J.; Wessel, R.A.; Wouters, J. Informal International Lawmaking. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Kotzé, L.J.; Kim, R.E. Earth System Law: The Juridical Dimensions of Earth System Governance. Earth System Governance 2019, 1, 100003. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. The Emergence of Transnational Environmental Law in the Anthropocene. In Environmental Law and Governance for the Anthropocene, edited by Louis J. Kotzé, 271–294. Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2017.

- Biermann, F.; Kim, R.E. Architectures of Earth System Governance: Institutional Complexity and Structural Transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.E.; Kotzé, L.J. Planetary Boundaries at the intersection of Earth system law, science and governance: A state-of-the-art review. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 2021, 30, 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Galaz, V. Global Environmental Governance, Technology and Politics: The Anthropocene Gap. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2019. [CrossRef]

- De Búrca, G.; Keohane, R.; Sabel, C. Global Experimentalist Governance. British Journal of Political Science 2014, 44, 477–486. doi:10.1017/S0007123414000076.

- Mai, L.; Boulot, E. Harnessing the Transformative Potential of Earth System Law: From Theory to Practice. Earth System Governance 2021, 7, 100103. [CrossRef]

- Hickey, C.; Robeyns, I. Planetary Justice: What Can We Learn from Ethics and Political Philosophy? Earth System Governance 2020, 6, 100045. [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R. Effectiveness of International Environmental Regimes: Existing Knowledge, Cutting-Edge Themes, and Research Strategies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 19853–19860. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, F.; Laguna-Celis, J.; Thompson, E. From Rio+20 to a New Development Agenda: Building a Bridge to a Sustainable Future. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Burke, A.; Fishel, S.; Mitchell, A.; Dalby, S.; J. Levine, D.J. Planet Politics: A Manifesto from the End of IR. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 2016, 44, 499–523. [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Cudworth, E.; Hobden, S. Anthropocene, Capitalocene and Liberal Cosmopolitan IR: A Response to Burke et al.’s Planet Politics. Millennium 2018, 46, 190–208. [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.-L.; Milkoreit, M. Imagination and Transformations to Sustainable and Just Futures. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 2020, 8, 081. [CrossRef]

- Oomen, J.; Hoffman, J.; Hajer, M.A. Techniques of Futuring: On How Imagined Futures Become Socially Performative. European Journal of Social Theory 2022, 25, 252–270. [CrossRef]

- Oomen, J. Producing the Inevitability of Solar Radiation Modification in Climate Politics. Ethics and International Affairs 2024, 38, 287–301. doi:10.1017/S0892679424000273.

- Hajer, M.A.; Oomen, J. Captured Futures: Rethinking the Drama of Environmental Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025.

- Pan, C. Rethinking Challenges of a Holographic World: Towards a Quantum Ontology for Global Governance. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 2025, 27, 529–541. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.C.; et al. An Aspirational Approach to Planetary Futures. Nature 2025, 642(8069), 889–899. [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. Coral Die-off Marks Earth’s First Climate Tipping Point, Scientists Say. Nature 2025. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Comparative dimensions of current governance, NSG, and World Federation.

Table 1.

Comparative dimensions of current governance, NSG, and World Federation.

| Dimension |

Current Governance

(Status Quo) |

Nested Systemic Governance (NSG) |

World Federation |

| Mandates |

Fragmented across >500 MEAs |

Organized into functional clusters |

Unified under constitutional order |

| Coordination |

Weak, ad hoc |

Moderate, via Global Environment Council |

High, through federal ministries |

| Enforcement |

Voluntary, soft law |

Peer review, reputational pressure |

Binding judicial enforcement |

| Legitimacy |

Limited citizen input, state-centric |

Stakeholder assemblies, consultative |

World Parliament + citizen representation |

| Adaptability |

High (polycentric) but incoherent |

Moderate, adaptable via hubs |

Balanced: regional autonomy + federal oversight |

| Authority |

State sovereignty dominant |

Shared, soft authority |

Constitutional, binding global authority |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).