1. Introduction

Engineering education worldwide is facing increasing demands to prepare graduates capable of addressing complex sustainability challenges, public safety concerns, and ethical responsibilities [

1,

2]. In the context of rapid urbanization, climate change, and growing resource constraints, engineers are no longer expected to function solely as technical problem-solvers but also as professionals who demonstrate ethical judgment, systems thinking, and sustainability awareness [

7,

8]. Consequently, higher education institutions are being urged to rethink traditional engineering curricula and to explore integrated educational approaches that combine technical competence with value-oriented learning [

9,

21].

Building Water Supply and Drainage Engineering is a core course in civil and environmental engineering programs and plays a critical role in connecting municipal infrastructure systems with building-scale water environments. The course is closely related to public health protection, efficient water resource utilization, and environmental sustainability. However, conventional teaching practices in this course have predominantly emphasized formula-based calculations and technical code interpretation, often overlooking the ethical, social, and environmental implications inherent in engineering decisions [

16,

17]. Such an approach may limit students’ ability to recognize the broader impacts of engineering systems and to make responsible decisions in complex real-world contexts.

Previous research in sustainability-oriented engineering education has highlighted the importance of integrating ethical responsibility and sustainability into professional training [

7,

8]. Nevertheless, in many engineering curricula these elements are still delivered as standalone modules or supplementary content, resulting in weak alignment between value education and core technical instruction [

6,

20]. This separation may hinder students from internalizing sustainability principles as an integral component of engineering practice.

In response to these challenges, embedding sustainability and ethical considerations directly into core engineering courses has emerged as a promising educational strategy. By situating value-oriented learning within authentic engineering problem-solving processes, students can engage with issues of sustainability and professional responsibility through experiential learning rather than abstract instruction [

5,

23]. This approach is consistent with the principles of Outcome-Based Education and emphasizes coherence among learning outcomes, instructional activities, and assessment methods [

15,

22].

Against this background, this study examines how a sustainability-oriented curriculum reform can be implemented in a Building Water Supply and Drainage Engineering course and evaluates its impact on student learning outcomes. By providing empirical evidence from a full cohort of undergraduate engineering students, this research contributes to international discussions on Engineering Education for Sustainable Development and offers a transferable pedagogical model for sustainability-integrated engineering education. Recent syntheses and calls for systemic transformation further emphasize the need for integrated sustainability learning in engineering curricula [

8].

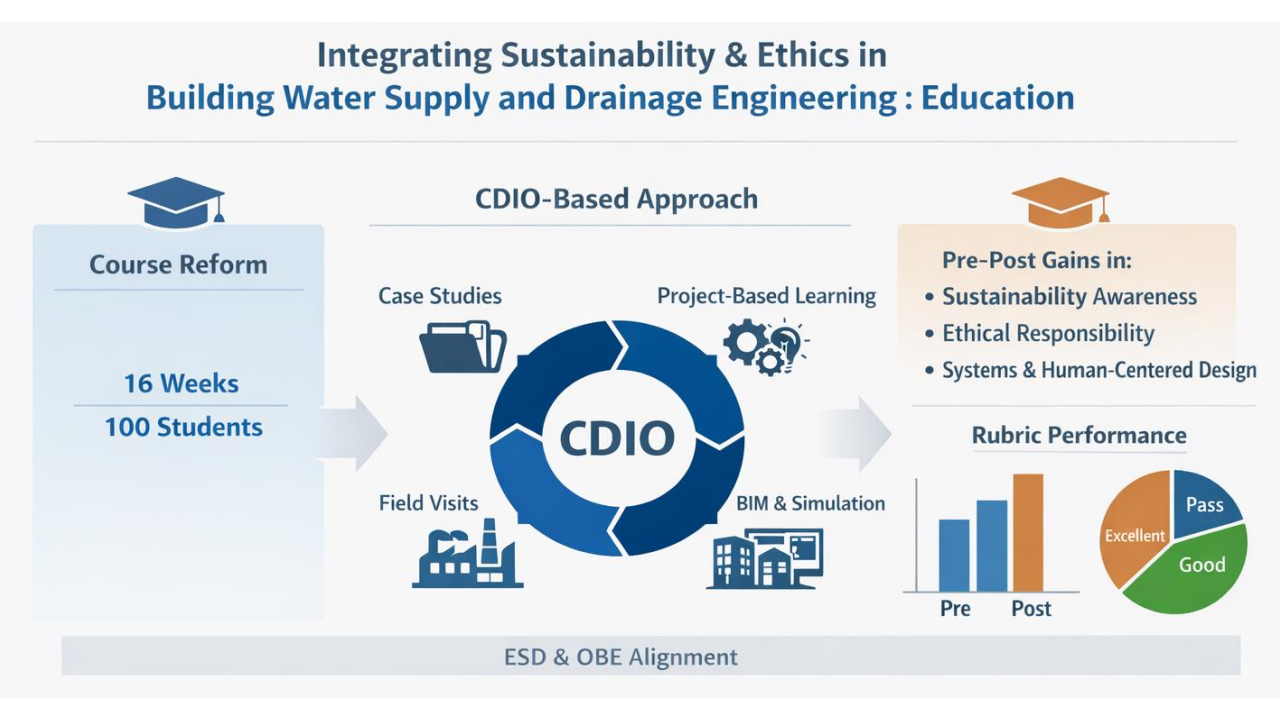

2. Conceptual Framework and Course Design

The curriculum reform was guided by Outcome-Based Education (OBE) principles and implemented through a CDIO (Conceive–Design–Implement–Operate) pedagogical framework [

5,

15]. Sustainability awareness, ethical responsibility, systems thinking, and human-centered design were identified as key learning outcomes and systematically embedded into course content and teaching activities based on widely recognized sustainability competency frameworks [

7,

8]. (

Table 1).

Table 1 was developed by the authors to illustrate the constructive alignment between intended learning outcomes, teaching activities, and assessment evidence under the OBE and CDIO framework. The four learning-outcome dimensions were informed by widely used sustainability competency frameworks and engineering ethics education literature.

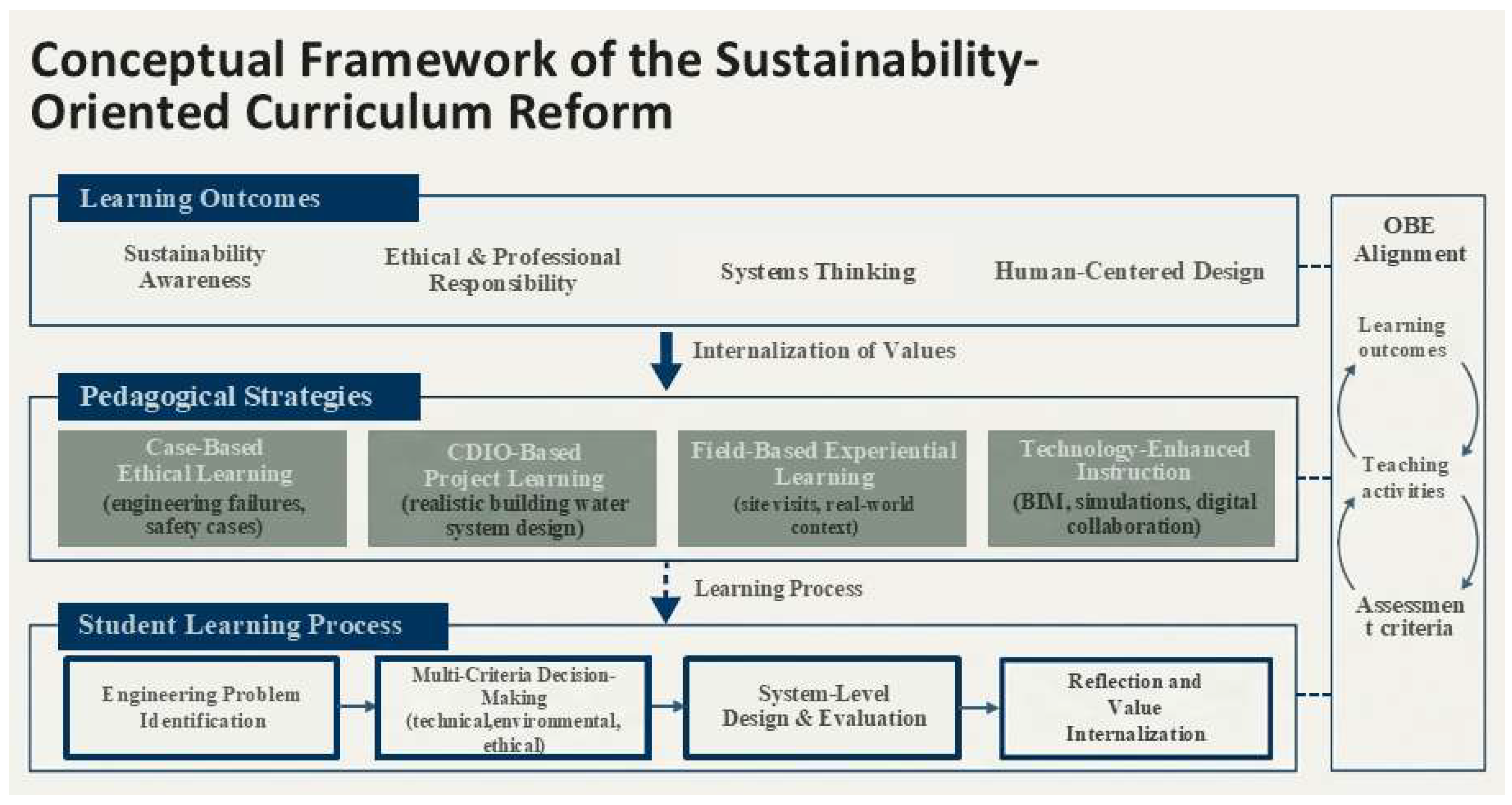

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework of the sustainability-oriented curriculum reform. As shown in

Figure 1, sustainability-oriented learning outcomes are achieved through value-integrated pedagogical strategies and a structured learning process that supports the internalization of professional responsibility and sustainability thinking.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Participants

A quasi-experimental pre–post design was adopted to examine the effects of the curriculum reform. A mixed-methods approach was employed to triangulate evidence from questionnaire data, project-based assessment, and student reflection reports [

12].

Participants were 100 third-year undergraduate students majoring in Water Supply and Drainage Engineering at Yan’an University. The sample represented a full cohort of students enrolled in the course during the academic year. (

Table 2).

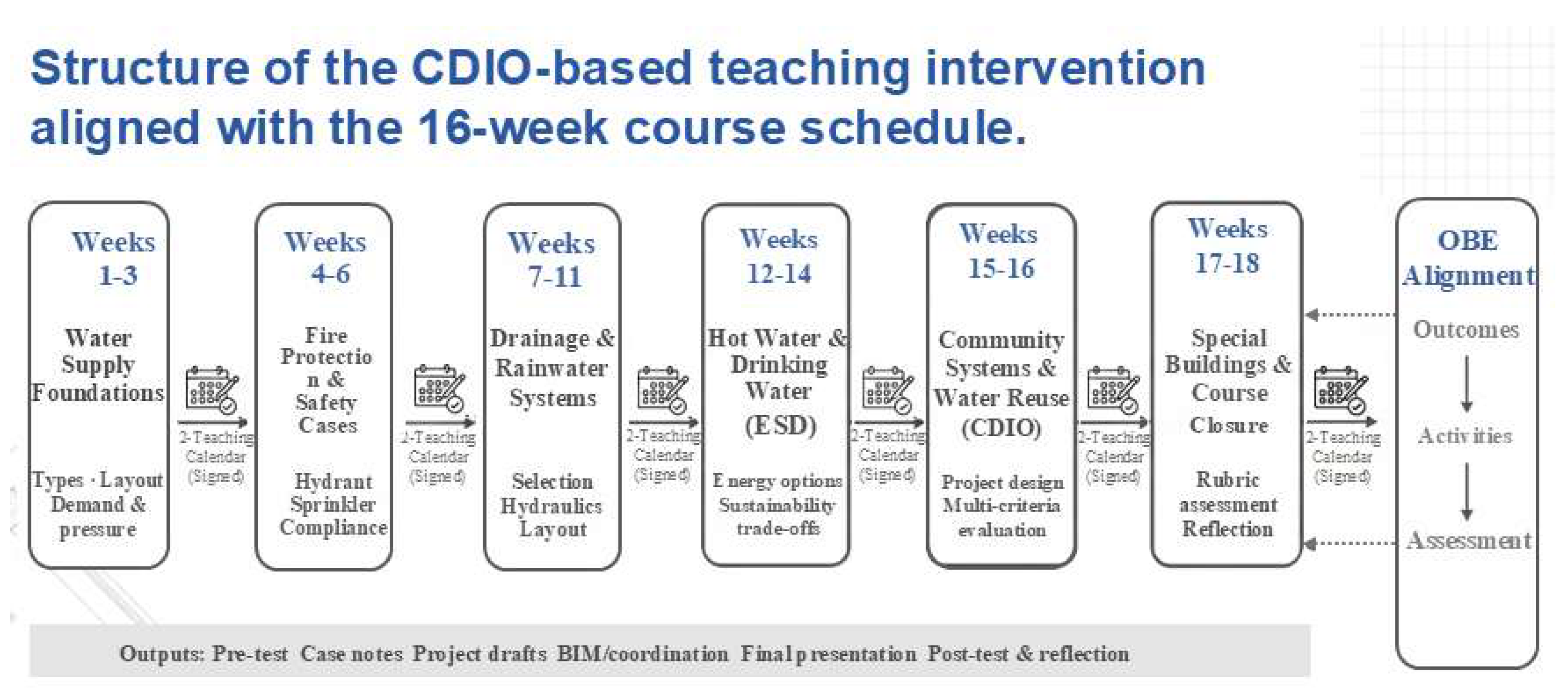

3.2. Teaching Intervention

The reformed course integrated sustainability and ethical considerations through multiple strategies, including case-based ethical learning, CDIO-based project learning, field-based experiential learning, and technology-enhanced instruction [

5,

9,

26,

27]. The overall intervention structure and its alignment with the semester schedule are summarized in

Figure 2.

3.3. Data Collection Instruments

Data were collected using (1) a sustainability-oriented questionnaire measuring four learning outcome dimensions; (2) a project assessment rubric evaluating technical accuracy, sustainability performance, ethical responsibility, human-centered design, and systems thinking; and (3) student reflection reports capturing learning experiences and value internalization [

14]. All questionnaire items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Dimension scores were computed as the mean of the corresponding items.

3.4. Data Analysis and Ethical Considerations

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, paired-sample t-tests, and effect size calculations (Cohen’s d) [

13]. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic coding [

11].

Participation was voluntary and data were collected anonymously. Students were informed that their responses would be used for research purposes only and would not affect course grades.

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and paired-sample t-tests to compare students’ pre-test and post-test scores across the four learning outcome dimensions. Paired-sample t-tests were performed based on student-level matched pre–post responses. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05. In addition, Cohen’s d was calculated to evaluate the practical magnitude of the observed changes. While the paired-sample t-test examines whether the pre–post differences are statistically significant, Cohen’s d indicates the educationally meaningful effect size of the intervention.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Reliability of the Questionnaire

Prior to further analysis, the reliability of the questionnaire was examined. The results showed good internal consistency across all dimensions. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.82 to 0.91, indicating satisfactory reliability of the measurement instrument. These findings support the appropriateness of the questionnaire for assessing students’ sustainability-oriented learning outcomes.

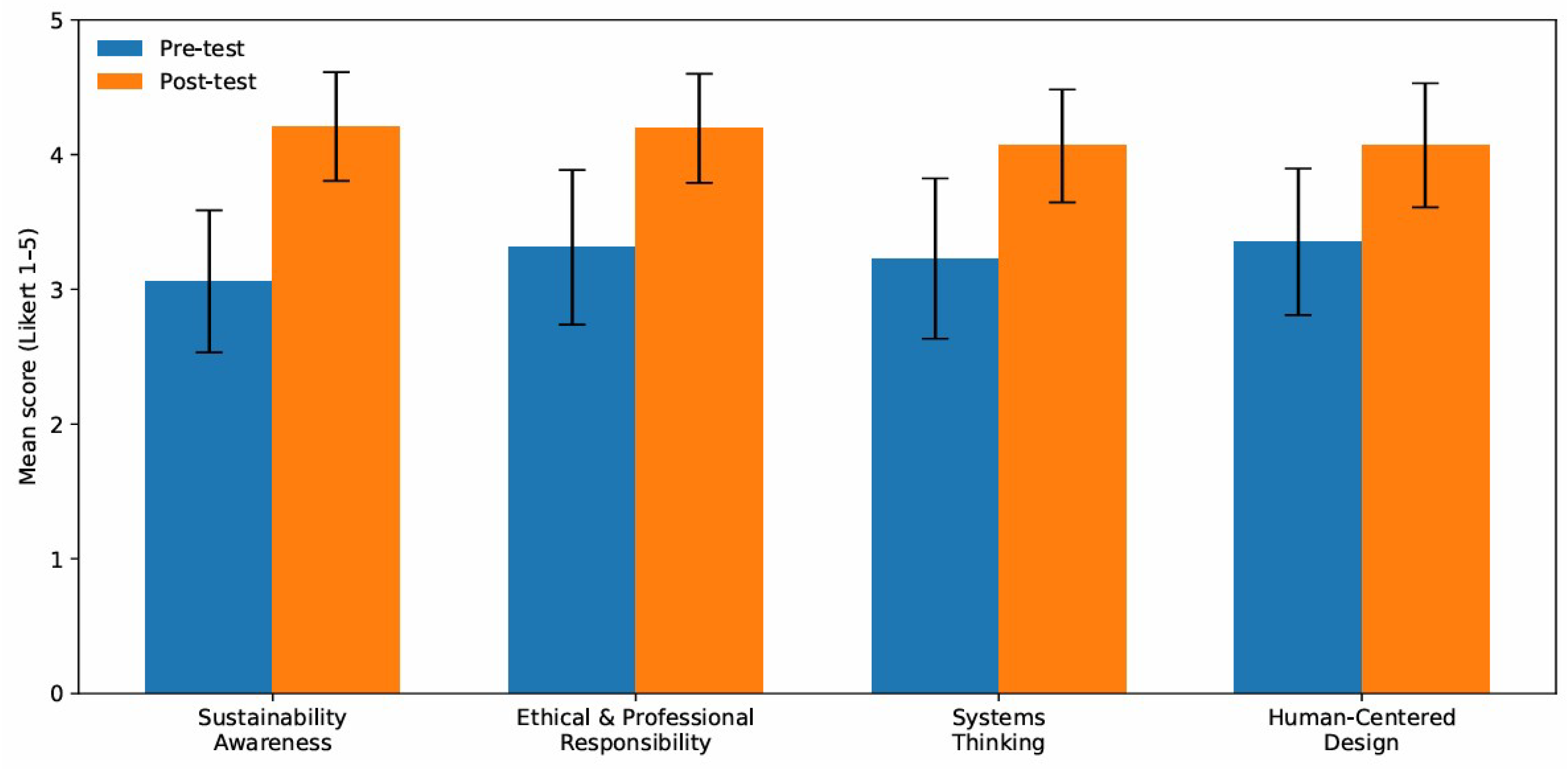

4.2. Changes in Students’ Sustainability-Oriented Learning Outcomes

To evaluate the effectiveness of the curriculum reform, paired-sample t-tests were conducted to examine differences between pre-test and post-test scores for each learning outcome dimension (

Figure 3 and

Table 3). The results indicate statistically significant improvements across all four dimensions (p < 0.001), suggesting that the observed gains were unlikely to be attributed to random variation. Cohen’s d values further demonstrated medium-to-large effect sizes, indicating that the intervention produced not only statistically significant changes but also practically meaningful improvements in students’ sustainability-oriented competencies. These findings demonstrate that integrating sustainability, ethical responsibility, and human-centered values into a core engineering course can lead to measurable gains in students’ professional competencies.

4.2.1. Engineering Ethics and Professional Responsibility

Students’ perceptions of engineering ethics and professional responsibility increased notably after the course. The mean score rose from M = 3.28 (SD = 0.54) in the pre-test to M = 4.15 (SD = 0.47) in the post-test. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.26). This improvement suggests that embedding ethical reasoning within technical learning and case-based activities can strengthen students’ awareness of professional responsibility.

4.2.2. Sustainability Awareness and Environmental Responsibility

The greatest improvement was observed in sustainability awareness. The mean score increased from M = 3.06 (SD = 0.53) to M = 4.21 (SD = 0.40), indicating a statistically significant change (p < 0.001) with a large educational effect (Cohen’s d = 1.65). This result provides evidence that sustainability competencies can be effectively cultivated when sustainability considerations are integrated into engineering design tasks rather than presented as supplementary content.

4.2.3. Human-Centered and Socially Responsible Design

Students demonstrated significant gains in human-centered and socially responsible design thinking. The pre-test mean score of M = 3.35 (SD = 0.54) increased to M = 4.07 (SD = 0.46) in the post-test (p < 0.001), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.95). This improvement indicates that connecting technical design decisions with user needs and public well-being can enhance students’ human-centered engineering perspective.

4.2.4. Systems Thinking and Engineering Decision-Making Ability

Improvements were also observed in systems thinking and decision-making ability. The mean score increased from M = 3.23 (SD = 0.60) to M = 4.06 (SD = 0.42) (p < 0.001), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.10). These findings highlight the value of project-based learning and iterative evaluation cycles in strengthening students’ ability to make system-level decisions under multiple constraints.

4.3. Project-Based Assessment Results

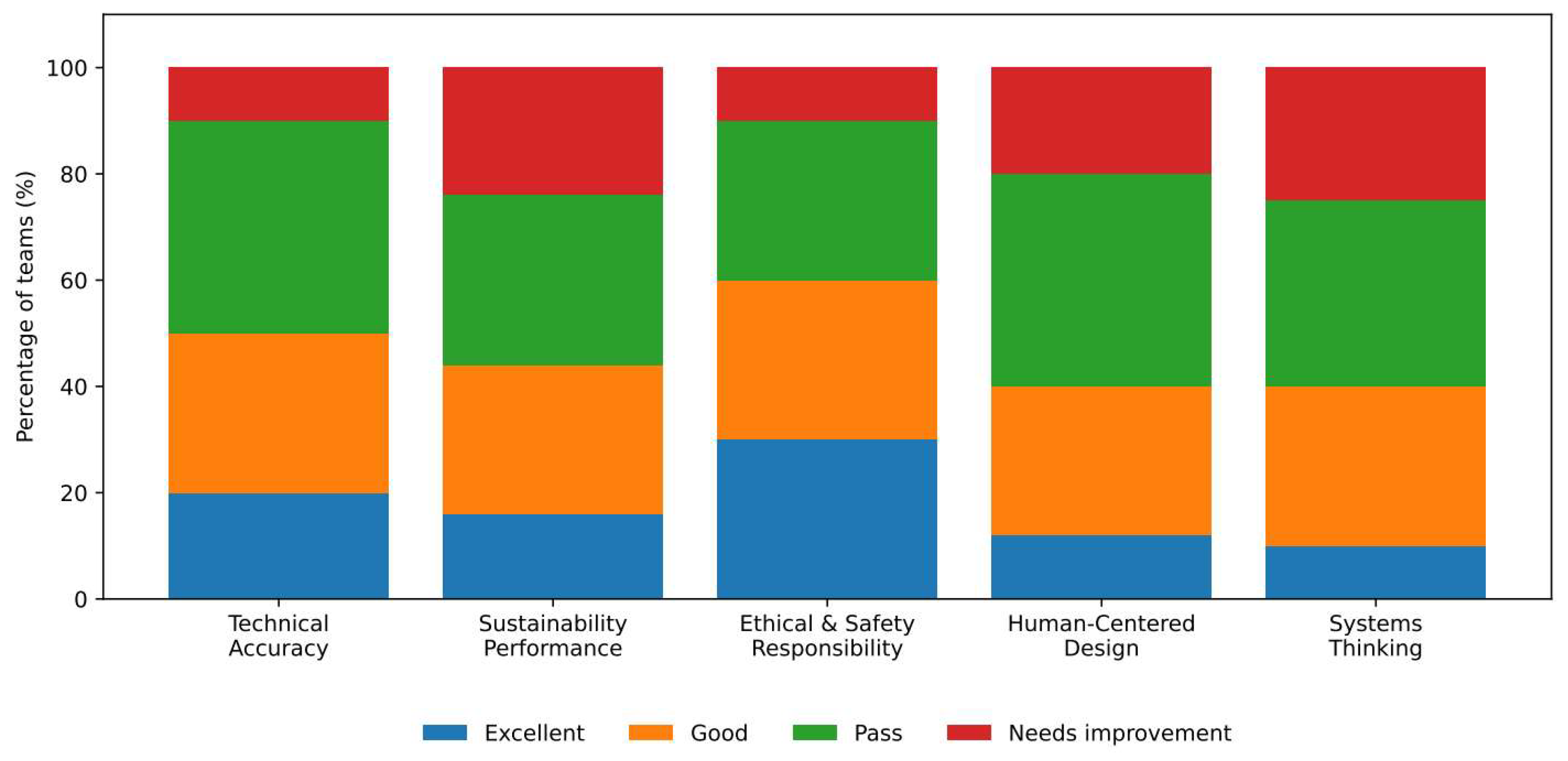

Project-based assessment results (

Table 4) further demonstrated students’ applied learning outcomes. A total of 44% of teams achieved ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ performance in sustainability criteria. Most teams explicitly incorporated water-saving technologies, water reuse systems, energy-efficient hot water strategies, or human-centered considerations into their final designs. These outcomes provide additional evidence that students were able to translate sustainability and ethical principles into practical engineering decisions. The distribution of rubric performance levels across dimensions is further illustrated in

Figure 4.

4.4. Qualitative Insights from Student Reflection Reports

Qualitative analysis of student reflection reports revealed themes consistent with the quantitative findings. Many students reported a shift in their understanding of engineering practice, recognizing that engineering design involves not only technical calculations but also ethical responsibility and sustainability considerations. These reflections further support the interpretation that value-integrated instruction contributes to students’ professional identity development and sustainability-oriented decision-making.

4.5. Implications for Engineering Education for Sustainable Development

The findings of this study offer several implications for Engineering Education for Sustainable Development (EESD). First, the results suggest that sustainability competencies can be effectively cultivated within discipline-specific core courses rather than relying solely on standalone sustainability or ethics modules. Embedding sustainability and ethical responsibility into technical problem-solving activities allows students to perceive these dimensions as integral components of engineering practice rather than external requirements.

Second, the CDIO-based instructional framework provides a practical mechanism for operationalizing EESD principles. By engaging students in the full cycle of conceiving, designing, implementing, and operating engineering systems, the course created opportunities for students to confront trade-offs among technical performance, environmental impact, safety, and social responsibility. This process-oriented learning experience supports the development of systems thinking and ethical judgment, which are widely recognized as essential competencies for sustainable engineers.

Third, the alignment of learning outcomes, teaching activities, and assessment criteria played a critical role in reinforcing sustainability-oriented learning. The use of sustainability-focused rubrics and reflective activities ensured that what was taught was also meaningfully assessed, thereby strengthening students’ motivation to engage with sustainability and ethical considerations throughout the design process.

From a broader perspective, this study demonstrates that sustainability-oriented curriculum reform does not necessarily require additional instructional hours or curricular expansion. Instead, thoughtful pedagogical redesign can enable existing courses to fulfill both technical and sustainability-related educational objectives. This insight is particularly relevant for engineering programs facing constraints related to curriculum load and accreditation requirements.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the positive findings, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted within a single institution and focused on one specific engineering course, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Future studies involving multiple institutions and diverse engineering disciplines would help to further validate the proposed teaching model.

Second, the evaluation focused primarily on short-term learning outcomes measured at the end of the course. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine whether the observed improvements in sustainability awareness, ethical responsibility, and systems thinking are sustained over time and influence graduates’ professional practice.

Finally, while this study employed a mixed-methods approach, future research could incorporate additional objective performance indicators or comparative control-group designs to strengthen causal inference. Addressing these limitations would contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the long-term impact of sustainability-oriented curriculum reform in engineering education.

4.7. Comparison with Related Studies in Sustainability-Focused Engineering Education

The present findings align with recent scholarship in sustainability-focused engineering education that highlights the effectiveness of active and experiential learning strategies in developing sustainability competencies [

8,

26,

27]. For instance, recent literature reviews emphasize that project-based learning (PBL) can foster meaningful engagement, professional skills development, and real-world problem-solving capacity when learning tasks are grounded in authentic engineering contexts [

26]. The gains observed in sustainability awareness and systems thinking in this study are consistent with this broader evidence base [

8].

Moreover, empirical studies adopting CDIO- or project-based approaches have reported that iterative design cycles, team-based tasks, and multi-criteria evaluation activities support students’ integration of technical knowledge with sustainability considerations [

27]. In this study, the emphasis on value-informed decision-making and sustainability-oriented rubrics may help explain the observed improvements across multiple learning outcomes.

In addition, recent calls for systemic transformation in engineering education have emphasized that sustainability education should be embedded in core disciplinary learning rather than treated as an external add-on [

8]. The present curriculum reform responds to this call by integrating sustainability and ethical responsibility within a core course closely tied to public health and environmental protection. By demonstrating measurable learning gains without expanding instructional hours, this study provides further evidence supporting the feasibility of sustainability integration under realistic curricular constraints.

Overall, the comparison with related work suggests that the proposed model contributes to the growing international evidence that sustainability-oriented pedagogy can enhance not only students’ knowledge and skills but also their professional identity development and responsibility awareness, which are essential outcomes for Engineering Education for Sustainable Development.

5. Conclusion

This study investigated the implementation and effects of a sustainability-oriented curriculum reform in a Building Water Supply and Drainage Engineering course. By integrating sustainability, ethical responsibility, and human-centered values into technical instruction through a CDIO-based teaching model, the course achieved significant improvements in students’ professional competencies.

The findings provide empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of embedding sustainability and ethics within core engineering courses. The proposed teaching framework offers a practical and transferable model for engineering programs seeking to advance Education for Sustainable Development without increasing curricular burden.

Future research may explore longitudinal impacts of such reforms, comparative studies across disciplines, and the relationship between sustainability-oriented education and professional identity development among engineering students.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Supplementary File S1: Sustainability-Oriented Learning Outcomes Questionnaire (English version); Supplementary File S2: Project-Based Assessment Rubric (team evaluation); Supplementary Figure S1: Structure of the Sustainability-Oriented Learning Outcomes Questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ting Huang and Tuo Wang; methodology, Ting Huang and Tuo Wang; teaching guidance, Fan Zhang and Yan’e Hao; investigation, Ting Huang, Chunbo Yuan, Li’e Liang, Xuerui Wang and Meng Yao; data curation, Ting Huang and Meng Yao; formal analysis, Ting Huang and Tuo Wang; writing original draft preparation, Ting Huang; writing, review and editing, Tuo Wang, Chunbo Yuan, Fan Zhang and Yan’e Hao; visualization, Ting Huang and Meng Yao; supervision, Fan Zhang and Yan’e Hao; project administration, Ting Huang; resources, Chunbo Yuan, Li’e Liang and Xuerui Wang; funding acquisition, Ting Huang. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shaanxi Province, grant number 2025SF-YBXM-524, and the Yan’an University Teaching Reform Project, grant number YDJG23-50.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because the research involved minimal risk and the data were collected anonymously for educational improvement purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Key R&D Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2025SF-YBXM-524) and the Yan’an University Teaching Reform Project (Grant No. YDJG23-50).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

| ABET |

Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology |

| CDIO |

Conceive–Design–Implement–Operate |

| EESD |

Engineering Education for Sustainable Development |

| ESD |

Education for Sustainable Development |

| OBE |

Outcome-Based Education |

| PBL |

Project-Based Learning |

| BIM |

Building Information Modeling |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Education for Sustainable Development for 2030; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://unece.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- ABET. Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs, 2024–2025; ABET Engineering Accreditation Commission: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.abet.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- ABET. Criteria for Accrediting Engineering Programs, 2025–2026; ABET Engineering Accreditation Commission: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.abet.org/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Crawley, E.F.; Malmqvist, J.; Östlund, S.; Brodeur, D.R.; Edström, K. Rethinking Engineering Education: The CDIO Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Edström, K.; Kolmos, A. Scholarly development of engineering education—The CDIO approach. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 45, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Barreiro-Gen, M.; Lozano, F.J.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K. Connecting competences and pedagogical approaches for sustainable development in higher education: A literature review and framework proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [CrossRef]

- Prince, M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J. Eng. Educ. 2004, 93, 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Brophy, S.; Klein, S.; Portsmore, M.; Rogers, C. Advancing engineering education in P–12 classrooms. J. Eng. Educ. 2008, 97, 369–387. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988.

- Brookhart, S.M. How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2013.

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University, 4th ed.; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2011.

- Herkert, J.R. Engineering ethics education in the USA: Content, pedagogy and curriculum. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2000, 25, 303–313. [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.E.; Pritchard, M.S.; Rabins, M.J.; James, R.W.; Englehardt, E.E. Engineering Ethics: Concepts and Cases, 6th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019.

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008.

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2000.

- Kolmos, A.; Hadgraft, R.G.; Holgaard, J.E. Response strategies for curriculum change in engineering. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 26, 391–411. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [CrossRef]

- Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. Designing and teaching courses to satisfy the ABET engineering criteria. J. Eng. Educ. 2003, 92, 7–25. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015.

- Pawson, R.; Tilley, N. Realistic Evaluation; SAGE: London, UK, 1997.

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the Ministry of Education on Issuing the Guiding Outline for Ideological and Political Education in Higher Education Curriculum (Curriculum Ideology and Politics). 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/ (accessed on 17 January 2026).

- Lavado-Anguera, S.; Velasco-Quintana, P.-J.; Terrón-López, M.-J. Project-Based Learning (PBL) as an Experiential Pedagogical Methodology in Engineering Education: A Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 617. [CrossRef]

- Menacho, J.; Pérez, J.; García, M. Evaluation of the Implementation of Project-Based-Learning in Engineering Education: A Case Study Using the CDIO Approach. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1107. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Rasche, A.; Schaltegger, S. Sustainability in Engineering Education: A Review of Learning Outcomes. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129904. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, S.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, M. Rethinking Sustainability in Engineering Education: A Call for Systemic Transformation. Front. Educ. 2025, 10, 1587430. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).