1. Introduction

Engineering education is rapidly transforming to meet the challenges and demands of the 21st century. Today’s engineers face an increasingly complex set of issues, ranging from global sustainability and technological innovation to social and ethical considerations. It is necessary to develop tools that facilitate educators and students’ understanding of this changing reality, while aligning them with the institutional framework. Addressing the transition required by the European Green Deal [

1] requires delving into educational pedagogies and adopting an educational competency framework that develops the GreenComp framework [

2] at all educational levels. These kinds of tools can facilitate knowledge construction through bottom-up qualitative and quantitative methods, reflecting the complex and interconnected nature of sustainability competencies and fostering a deeper understanding of the intricate relationships between concepts and competencies. To this end, digital tools have been repurposed to enhance cognitive processes such as visual recognition and the management of complex information [

3]

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are adopting multidisciplinary approaches that integrate system thinking, sustainability, and ethics into engineering education to address these challenges.

By leveraging multidisciplinary engineering education, institutions can equip future engineers with the knowledge, skills, and mindset needed to address the complex challenges outlined in the SDGs. This approach can foster innovation, collaboration, and a deep commitment to sustainable development within engineering [

4].

A multidisciplinary approach can enhance the effectiveness of sustainability education in higher education curricula in several ways. Firstly, by involving multiple disciplines, students can gain a broader understanding of sustainability issues from various viewpoints. In addition, Collaboration among students and faculty from different disciplines can foster creativity and innovation in addressing sustainability issues. Multidisciplinary perspectives also enable students to approach sustainability challenges from various angles and consider broader solutions. Real-World Application: Integrating multiple disciplines in sustainability education can better prepare students for real-world challenges where solutions often require interdisciplinary collaboration. Finally, exposure to diverse disciplines can deepen students’ understanding of the interconnected nature of sustainability issues and the need for integrated solutions [

4]. Sharma et al. [

5], also explained that multidisciplinarity enhances communication and time management skills. Furthermore, multidisciplinarity would enrich all the dimensions of teamwork. However, students found it a barrier to effective learning and communication.

From a practical perspective, various institutions have demonstrated that interdisciplinary approaches enhance student engagement and comprehension in sustainable engineering courses [

6]. In this regard, the implementation of educational programs based on these models has improved graduate employability, enabling them to adapt more efficiently to technological and environmental changes [

2,

7].

Moreover, recent studies highlight that multidisciplinary methodologies in engineering have facilitated better knowledge integration, allowing for the development of more efficient, ethical, and sustainable solutions in fields such as energy, construction, and urban development [

8,

9].

Based on the background presented, this research seeks to answer the following key questions: What are the challenges and opportunities in implementing multidisciplinary approaches in engineering education to promote sustainability?

This paper analyses the role of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches in the education of engineers capable of integrating sustainability into technical solutions. Key strategies are identified, including curriculum design, interdisciplinary projects, industry partnerships, experiential learning, and professional development, which serve as fundamental pillars in achieving this goal.

To ensure the rigor and relevance of this study, the selection of bibliographic references followed a set of specific criteria, allowing for the inclusion of studies that align with the research objectives.

The research, projects and papers considered in this work were chosen based on the following principles:

Thematic relevance: Priority was given to studies that directly address engineering education, multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, and the integration of sustainability into academic programs. Additionally, research exploring the application of multidisciplinary methodologies in teaching SDGs and those analysing how engineers develop key skills, such as critical thinking and problem-solving, within a sustainable educational framework, were included.

Academic rigor and credibility: Only papers published in indexed scientific journals, specialized conferences, and reports from recognized educational and engineering institutions were selected. The cited studies had established authors, well-defined methodologies, and results backed by empirical evidence. Priority was given to research with significant citations and references, ensuring that conclusions were based on solid and up-to-date data.

Contribution to the study’s specific objectives: References were selected that provide innovative pedagogical strategies for multidisciplinary engineering education, studies that analyze the impact of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches on the development of critical competencies, and reviews that propose effective curricular models for sustainable engineering education. Documents exploring the challenges and opportunities of implementing these approaches in educational institutions were also included.

Recency and relevance: Studies published between 2010 and 2025 were selected to ensure that the information reflects current trends in engineering education and sustainability. Priority was given to documents contributing to curriculum development within the contemporary context.

2. The Concepts of Multidisciplinarity and Interdisciplinarity

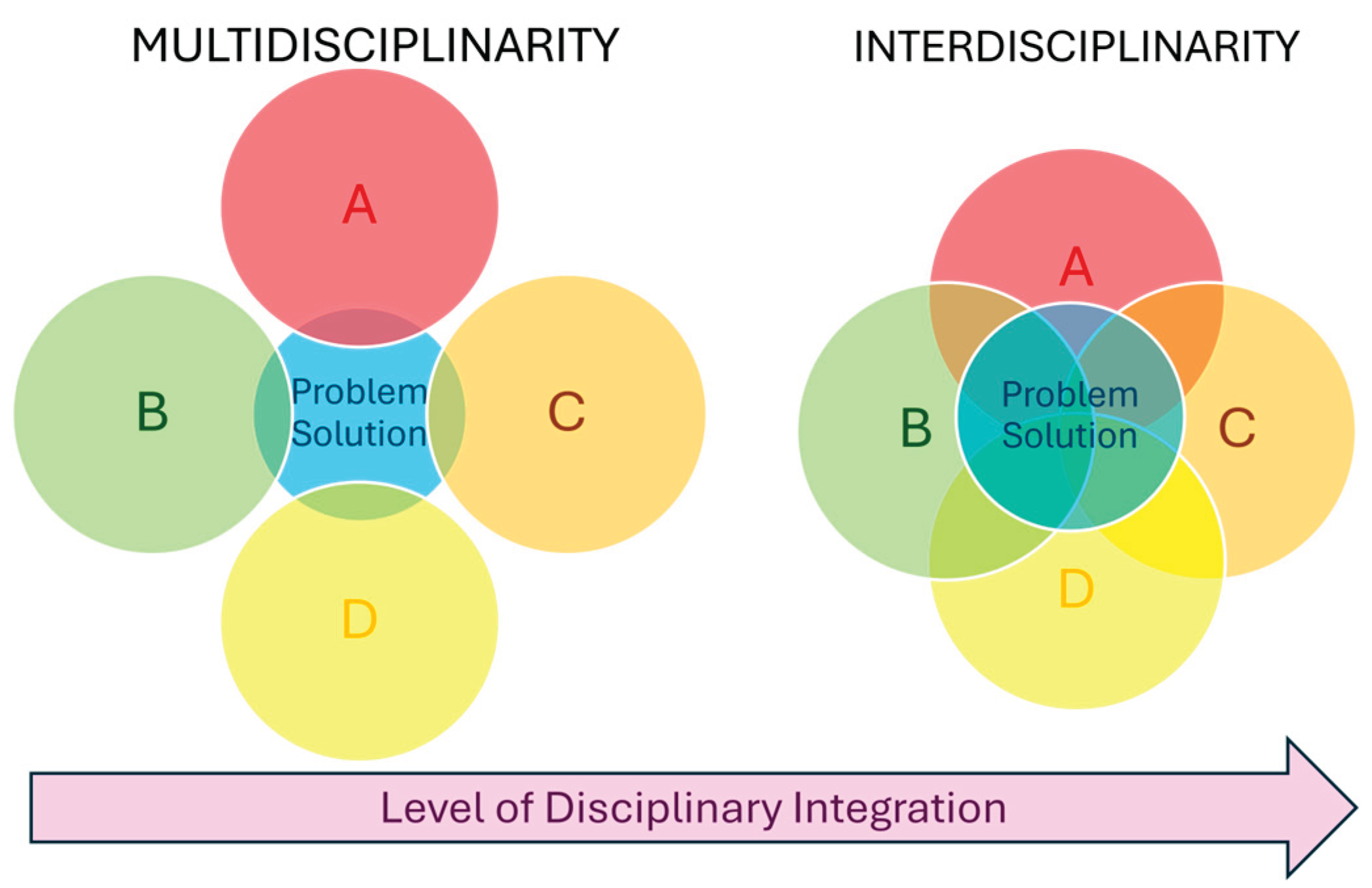

In contemporary education, particularly within engineering and sustainability contexts, two approaches have emerged as crucial for curricular innovation: multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they embody distinct methodologies for knowledge integration, each with unique structural and methodological implications for sustainability education.

Understanding these concepts can enhance curriculum development and foster more effective teaching methodologies. Multidisciplinarity refers to the inclusion of multiple academic disciplines in a single educational program or project, where each discipline retains its distinct approaches and methodologies while contributing to a common goal. In contrast, interdisciplinarity emphasizes the integration of knowledge and methodologies from various disciplines to create a cohesive framework that transcends the boundaries of individual fields (

Figure 1).

Multidisciplinary approaches often engage various fields without the need of a synthesis of discipline for problem-solving. For instance, in civil engineering education, integrating sustainability concepts can be characterized as a multidisciplinary effort, where engineering principles coexist alongside sustainability frameworks without requiring a shared methodology across disciplines. According to Chau, this approach allows students to acquire multidisciplinary skills that contribute significantly to their understanding of sustainability, reflecting the ability to apply different disciplines independently toward common educational outcomes [

10]. The incorporation of concepts such as sustainability in engineering curricula underscores the limitations of multidisciplinary, as students may learn to apply distinct concepts without necessarily integrating them into a cohesive problem-solving strategy [

5]. For example, in engineering education, sustainability topics are often introduced within standalone courses—such as environmental science, economics, and mechanical engineering—without requiring students to synthesize the different perspectives into an integrated framework. As Caro Saiz et al. ) [

6] point out, excessive specialization can hinder the ability to address complex sustainability challenges. UNESCO [

11,

12] further emphasizes that while multidisciplinary education enriches understanding, engineers must also develop the capacity to consider environmental, economic, and social dimensions in concert.

On the other hand, interdisciplinarity fosters a more collaborative and integrated learning experience. Research by Dorst [

13] demonstrates that the complex, open, and dynamic challenges of today require interdisciplinary collaboration to design effective solutions. In the context of educational initiatives aimed at addressing complex societal challenges, Coral and Carracedo assert the importance of fostering spaces for collective reflection and collaboration that enable critical thinking beyond disciplinary boundaries [

14]. Such integrative practices are essential in producing graduates capable of dynamic thinking and innovative problem-solving skills, particularly for addressing pressing issues like climate change and environmental degradation. This collaborative approach is also reflected in the study by Feng et al., which highlights how faculty experiences can pave the way for a more interdisciplinary education that prepares students for real-world challenges through a synthesis of diverse disciplinary insights [

15].

Interdisciplinary education emphasizes the need for faculties to engage in transdisciplinary teaching methods that augment conventional teaching strategies. For example, Llopis-Albert et al. point to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in mechanical engineering education to create an interdisciplinary framework where curriculum design transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries, thereby equipping students to address complex sustainability issues effectively [

9]. This approach reflects a paradigm shift in education—from a collection of separate domains toward an interconnected structure where knowledge is co-created and contextually relevant.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary methodologies align with contemporary educational trends that underscore the importance of sustainability in engineering and other disciplines. Literature advocates for a holistic approach to education, where disciplines converge to support overarching sustainability objectives. For instance, the development of tools such as the Sustainability Matrix as described by Carracedo et al. serves as an integrative mechanism for assessing sustainability competencies across diverse engineering curricula [

10]. Such tools reflect the essence of interdependence among disciplines and represent a significant advancement from mere multidisciplinary representations, which often lack the depth of integration necessary for comprehensive educational frameworks.

Additionally, the systematic review by Thürer et al. emphasizes that successful integration of sustainability into engineering curricula requires an interdisciplinary approach, which facilitates a comprehensive understanding of systemic challenges and drives innovation through collaborative efforts [

16]. This integration underscores the notion that addressing complex socio-environmental issues cannot be achieved by single disciplinary efforts alone; rather, it necessitates a fusion of insights and methodologies.

It is also important to acknowledge that the contrasting nature of multidisciplinarity and interdisciplinarity is evident in curriculum design and teaching practices. The latter demands not just the coexistence of discipline but the creation of learning environments that encourage collaborative inquiry and synthesis of knowledge. Educators are called to foster environments that facilitate dialogue across disciplines and encourage the co-creation of knowledge, which is pivotal in preparing future engineers and professionals for the complexities of modern societal challenges [

6]. In this sense, the pedagogical shift toward interdisciplinarity aligns with a broader educational imperative to develop holistic, systems-thinking competencies in students.

Furthermore, as attested by Giddings et al., effective sustainable development strategies require an understanding that environmental, economic, and social dimensions are interconnected and cannot be addressed in isolation [

17]. This underscores the necessity of interdisciplinary approaches, where students are trained to view issues through interconnected lenses rather than fragmented perspectives. The ongoing discourse surrounding these educational paradigms illustrates a growing recognition of the inherent limitations of a purely multidisciplinary approach, advocating instead for frameworks that promote collaborative, integrative learning experiences.

In terms of practical application, interdisciplinary endeavors can be observed within educational programs that incorporate real-world problem scenarios, such as those focusing on energy and environmental sustainability. The work by Skowronek et al. exemplifies the need for inclusive education that spans diverse fields and employs interdisciplinary frameworks to address the intricacies of sustainable energy development [

18]. This approach aligns with the overarching goal of cultivating educators and learners equipped to handle multifaceted, contemporary challenges, demonstrating the practical relevance of interdisciplinary integration.

The potential of interdisciplinary frameworks to transform educational practices becomes increasingly evident as the discourse surrounding sustainability and social responsibility intensifies. Ultimately, the effective integration of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary strategies has the potential to enhance educational experience, fostering deeper levels of engagement and understanding that traditional disciplinary approaches fail to achieve. Thus, moving towards an interdisciplinary educational model is essential for producing competent professionals capable of navigating the complexities of modern societal challenges.

In summary, while multidisciplinary allows for the coexistence of different disciplinary perspectives, interdisciplinarity necessitates the integration and synthesis of these perspectives into a cohesive framework. The shift towards interdisciplinary education represents a critical re-evaluation of traditional academic boundaries, fostering collaborative learning environments that enhance students’ problem-solving skills and prepare them for the complexities of a rapidly changing world. This intellectual evolution is crucial for advancing both educational practices and societal outcomes, solidifying the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in contemporary education.

The fundamental differences between multidisciplinary and interdisciplinarity can be summarized as shown in

Table 1.

This comparison accentuates that while multidisciplinarity offers diverse perspectives, its lack of integration may restrict holistic problem solving. Conversely, interdisciplinarity fosters deeper synthesis and systems thinking, which is particularly crucial for addressing the complex challenges of sustainability in engineering.

3. Educational Practices and Sustainability

The impact of a multidisciplinary approach in sustainability education is profound and multifaceted, as it aligns with the diversified and complex realities of environmental, social, and economic systems inherent in sustainability. Multidisciplinary education situates itself at the intersection of various fields, thereby facilitating a more holistic understanding of sustainability challenges, which are often interdependent and require collaborative solutions. This perspective is increasingly important in a world characterized by the intricate interactions of human and ecological systems, making the need for a comprehensive educational framework paramount [

19,

20].

The inherent challenges in sustainability are often described as "wicked problems," which are complex and not easily solved through a singular disciplinary lens [

21]. As articulated by Parry and Metzger, teachers often demonstrate a predominant understanding of environmental sustainability but lack the comprehensive training required to effectively address the social and economic dimensions [

19]. This highlights a need for educational curricula to expand beyond entrenched disciplinary divisions, allowing for the integration of diverse perspectives that are vital for instilling an understanding of sustainable principles among students.

As evidenced by Chan and Nagatomo, the Design for Disaster project exemplifies how multidisciplinary inputs can manifest in educational contexts, providing students with a structured framework to tackle sustainability issues [

22]. The project’s framework integrates various guest lectures and consultant sessions, illustrating how collaborative efforts across disciplines can cultivate essential skills in students and encourage sustainable development thought processes. This collaborative framework is critical, as sustainability problems, like climate change or resource depletion, do not conform to single-disciplinary solutions; rather, they require the integration of various methodologies and insights [

23,

24].

Moreover, educational practices that embrace outdoor and experiential learning, as seen in the research conducted by Ratinen et al., can effectively promote sustainability awareness and foster active learning experiences [

25]. The combination of theoretical knowledge with empirical outdoor experiences creates a rich learning environment where students can observe and engage with sustainability issues firsthand. Importantly, students are not only passive receivers of knowledge but active participants in the learning process, which enhances retention and understanding of complex sustainability metrics [

26]. This participatory aspect is vital in empowering learners, as it fosters responsibility and curiosity about their surroundings, encouraging them to think critically about sustainability actions.

Furthermore, the findings by Edwards et al. assert that sustainability education can act as a bridge between diverse academic disciplines, allowing students to engage with socio-ecological issues in multifaceted ways [

27]. By integrating business disciplines with scientific principles, the curriculum can more readily address the holistic nature of sustainability [

12]. This notion resonates with the idea that educational institutions must not only integrate sustainability into the curriculum but also embrace participatory processes, as these processes allow for robust engagement across disciplines, thus broadening the student experience [

5].

The role of technology in enhancing multidisciplinary approaches cannot be overlooked, as tools like virtual laboratories and digital simulations provide interactive platforms that reinforce the interconnectedness of sustainability concepts [

20]. Digital educational tools facilitate collaborative learning environments where students can experiment with real-life sustainability challenges from various perspectives, enriching their understanding of the complexities they will face in their professional careers. This innovative educational approach aligns with the growing emphasis on green technologies and sustainable practices in various sectors of the economy [

28].

Moreover, the implementation of project-based learning methodologies, as discussed by Bielefeldt and Casanovas et al., further highlights the necessity of aligning practical experiences with theoretical frameworks in sustainability education [

29,

30]. Such methodologies not only help reinforce content knowledge but also foster essential soft skills, such as teamwork, critical thinking, and problem-solving—skills that are vital for future leaders navigating the complexities of sustainability issues [

2].

In summary, the impact of multidisciplinary approaches in sustainability education cannot be understated. By fostering a comprehensive understanding of environmental, social, and economic systems, educators can better equip students with the knowledge and skills necessary to address contemporary challenges effectively. Emphasizing the integration of knowledge from various disciplines, promoting active learning, and utilizing innovative educational tools are all essential components for developing effective sustainability education curricula. It is through these multifaceted efforts that we can truly hope to cultivate a new generation of informed decision-makers equipped to champion sustainable practices in an increasingly complex world.

4. How to Use Multidisciplinary and Interdisciplinarity to Include SDGs Skills

The incorporation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) into educational practices requires a multidisciplinary approach that recognizes the interconnected nature of the goals and the diverse knowledge and skills necessary to address complex global challenges. The integration of SDGs into curricula across various educational institutions has emerged as a pivotal method to foster a comprehensive understanding of sustainability among students. This multifaceted strategy enhances academic knowledge and equips students with essential competencies for real-world applications.

One significant aspect of integrating SDGs into education is acknowledging the interrelatedness of the goals themselves. As noted by Blasco et al., universities have a critical role to play in achieving these goals, necessitating active policies that encourage collaborative participation across different disciplines [

31]. Incorporating the SDGs into curricula encourages students to consider various perspectives, leading to richer learning experiences and deeper problem-solving capabilities. This holistic approach enables students to better understand socio-environmental challenges through transformative methodological strategies, as described by González et al. [

32].

Moreover, the need of integrating multidisciplinary learning into higher education to equip future professionals with the skills required to address current and future challenges is underscored in the literature. Molina et al. describe how reciprocal learning between various socio-economic contexts contributes to a more robust educational experience, nurturing graduates capable of innovative and sustainable solutions to pressing issues [

33]. By fostering collaboration among diverse fields, educational institutions can facilitate the development of critical thinking and creativity among students, which are essential competencies in addressing the SDGs [

34].

Critical thinking emerges as a vital skill developed through interdisciplinary educational strategies. Indahwati et al. highlight the effectiveness of integrating independent learning mechanisms within the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) framework specifically in the context of renewable energy education [

35]. This integration promotes critical thinking skills and engages students in the practical application of their knowledge towards achieving specific SDGs related to environmental sustainability. By employing innovative pedagogical methods, educators can enhance students’ analytical and evaluative skills necessary for tackling the multifaceted challenges represented by the SDGs.

Inclusivity in education is another crucial aspect derived from the SDG framework. Khalil’s analysis emphasizes the need to revise educational curricula to align with SDG 4, which advocates for quality education that meets diverse student needs [

36]. This necessitates incorporating 21st-century skills and knowledge conducive to fostering sustainable development literacy among students. The education system must focus on inclusivity, ensuring that every learner, regardless of background or ability, is equipped with the tools to contribute to sustainability efforts.

Additionally, technological advancements’ role in enhancing educational strategies cannot be overlooked. Educational tools, such as serious games, have been proposed as effective methodologies for engaging students in the SDGs and developing their critical competencies in a context that resonates with contemporary digital learning environments [

37]. By using interactive platforms, educators can stimulate interest and motivate students to explore the complexities of sustainability in a collaborative atmosphere, further aligning educational objectives with the SDGs.

The incorporation of practical and applied learning experiences strengthens educational approaches toward SDGs. Projects that require students to work on real-world problems allow them to contribute to sustainability initiatives directly. As detailed in the research by Calvo et al., the implementation of multidisciplinary projects has proven to raise awareness of the SDGs and mobilize students toward sustainability as a viable professional aspiration [

21]. Projects enhance the relevance of study and solidify the application of learned skills in authentic contexts.

Moreover, the implications of SDGs in education extend beyond mere curriculum integration; they reshape the very framework of pedagogical practices employed at educational institutions. As noted by Pacheco et al., fostering an environment where teamwork and communication are emphasized through project-based learning aligns with several SDGs, such as those related to partnerships for the goals (SDG 17) and quality education (SDG 4) [

38]. Through collaborative engagements, students develop the interpersonal skills required to work effectively across disciplines, which is crucial for addressing complex sustainability challenges.

Leadership and advocacy from academic institutions are also essential. Universities, as indicated by Pacheco et al., serve as engines of social transformation that can drive forward the SDGs by developing globally minded citizens equipped with pertinent knowledge and innovative solutions to societal challenges [

38]. The strategic incorporation of SDGs within institutional missions and cultures fosters a community-wide commitment to sustainability that transcends individual academic endeavors.

Engagement with external stakeholders, including industry partners, can augment educational efforts toward sustainability as well. As highlighted by Rao et al., institutions must collaborate with industries to ensure that educational outputs align with market demands, thus maximizing employability while contributing to the SDGs [

39]. Such partnerships cultivate an ecosystem where education directly meets community and environmental needs, enhancing the practical application of learned skills.

Interdisciplinary collaborations further enrich the educational landscape concerning the SDGs. Alfarizi and Yuniarty present a robust framework where climate change and sustainability are approached through multidisciplinary lenses, each providing unique solutions that complement one another [

40]. In academia, this fosters an environment conducive to the holistic development of sustainability competencies among students.

Moreover, the use of benchmarks such as the Sustainability Tracking, Assessment & Rating System (STARS) provides a foundational approach for measuring the effectiveness of SDG integration within educational programs [

41]. These frameworks highlight institutional progress toward sustainability goals and offer insights into areas for improvement. The emphasis on continuous assessment promotes accountability and encourages institutions to evolve in their educational approaches, thereby enhancing their overall impact on global sustainability.

Furthermore, discussions surrounding public awareness and community engagement reveal the importance of extending sustainability efforts beyond academic walls. Initiatives that promote community involvement through service-learning projects showcase the real-world implications of SDGs and foster civic responsibility among students [

42]. Such programs serve to bridge the gap between theory and practice while instilling a sense of duty toward local and global communities.

In conclusion, the integration of Sustainable Development Goals into educational frameworks necessitates a robust multidisciplinary approach that encompasses various teaching methodologies, collaborative efforts, and community engagement. This comprehensive strategy prepares students to tackle complex sustainability challenges and cultivates an ethos of responsible citizenship essential for fostering a sustainable future. By fostering critical thinking, inclusivity, and collaboration across disciplines, educational institutions can create transformative learning experiences that resonate with the goals of the SDGs and ensure that future generations are equipped to navigate and contribute to an increasingly complex world..

5. Multidisciplinary/Interdisciplinary Ways in Engineering for ESD

Many authors argue that a multidisciplinary approach is essential for addressing complex sustainability challenges.

For example, findings from the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM) [

43] demonstrate that integrating sustainability into both business plans and engineering curricula improves professional readiness by explicitly incorporating ethical decision-making and socially responsible practices. The study identifies core competencies—including advanced data analysis to support decisions on social, scientific, and ethical issues—that are critical for sustainability. Furthermore, it advocates for transparent institutional models and structured ethics training programs that are embedded within the curriculum. It also notes that curricula can be enhanced by integrating hands-on projects and extracurricular learning experiences that connect theory with real social and environmental issues. Despite these challenges, inspiring case studies confirm the feasibility of incorporating sustainability into university engineering education. Adopting a multidisciplinary framework can merge theoretical insights with practical methodologies—such as team-based, problem-solving projects—to encourage innovative solutions for sustainability challenges. Successful implementation requires explicitly defined collaborative processes, including cross-departmental seminars and joint projects that are evaluated through both qualitative and quantitative assessments. Structured exposure to different fields, as measured by integrated coursework and project evaluations [

43], helps students appreciate the complexity of sustainability challenges. By explicitly linking course objectives to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), engineering programs can ensure that graduates possess the interdisciplinary skills required to develop targeted sustainable solutions. Such an integrated approach not only builds technical expertise but also emphasizes critical reflection, teamwork, and effective communication—skills that are systematically assessed through continuous feedback and targeted project reviews [

4].The current green and digital transitions underscore the need for specialized training in technologies (e.g., Building Information Modeling (BIM), cloud computing, AI, and 3D printing) which are increasingly incorporated into project-based courses that include defined assessment rubrics [

44].

Emerging engineering competencies require systematic curriculum redesign and innovative pedagogical models—such as iterative project assessments and competency-based evaluations—to effectively integrate sustainability. Reforming higher education to reflect social and sustainability imperatives demands not only interinstitutional collaboration [

45] but also the implementation of pilot programs with clear metrics for success and continual revision based on stakeholder feedback.

Nevertheless, substantial challenges remain. Instructors face difficulties such as reconciling varied disciplinary terminologies and pedagogical approaches, which can lead to miscommunication and fragmented learning experiences. Effective management of interdisciplinary initiatives requires explicit leadership structures, regular coordination meetings, and shared digital platforms to synchronize efforts across departments.Implementing these approaches may necessitate targeted faculty development programs, dedicated funding for curriculum innovation, and the establishment of interdisciplinary research centers. Additionally, robust evaluation methods—such as mixed-method assessments and longitudinal tracking of graduate performance—must be developed to gauge the true efficacy of these interdisciplinary strategies. Resistance from entrenched academic structures and traditional teaching practices remains a significant barrier, calling for institutional policies that incentivize pedagogical innovation [

46]..

Craig and Voglewede’s [

47] proposal for a Master of Engineering Studies in Mechatronics at Marquette University provides concrete evidence of multidisciplinary implementation; the program combines rigorous technical training with project-based modules that explicitly address sustainability through case studies and field projects. This program details specific methodologies—such as collaborative design challenges and sustainability audits in product development—that demonstrate measurable improvements in student competencies. It stresses that modern engineers must combine deep disciplinary expertise with cross-disciplinary knowledge and balanced hands-on experience, as evaluated through standardized rubrics and peer reviews. In practice, the program uses defined project milestones and sustainability impact assessments to ensure that product development aligns with environmental and social objectives.

MacDonald et al. [

48] highlight that aligning learning objectives with the pace of technological change requires adaptive curriculums that integrate evolving fields like AI into concrete projects with clearly defined performance indicators. Their analysis leverages Bloom’s Taxonomy [

49] to develop measurable learning outcomes in a structured manner. The work also calls for incorporating case studies that contextualize global inequalities and policy impacts, thus equipping students with analytical tools through real-world scenarios Empirical evidence suggests that structured experiential learning models—which include internships and field placements with clear evaluation metrics—substantially improve graduate outcomes in sustainability [

48] [

49].Skowronek et al. [

18] document specific challenges in STEM education, such as underrepresentation and skills gaps, and propose tailored interventions (e.g., mentorship programs and research immersion) as part of a retooled curriculum aimed at sustainable energy and AI sectors. Their proposal for a STEAM model details how integrating arts and humanities can be operationalized through interdisciplinary workshops and collaborative projects that are continually assessed for creative outputs and critical analysis. Moreover, the study provides data on how AI-driven tools can facilitate critical thinking, and it recommends structured mentoring and research immersion with quantified benchmarks for success.

Bhandari’s [

46] long-standing course at Iowa State University demonstrates a clear curriculum design: it integrates sustainability topics (water, energy, food, and shelter) through modular lessons combined with practical group projects and outcome-based assessments across diverse socioeconomic contexts. The University of Kentucky’s interfaculty course [

50] incorporates systems thinking by using interdisciplinary workshops and collaborative projects, evaluated via multi-criteria rubrics that measure both technical and communicative skills. These courses employ a combination of teacher evaluations, formative assessments, concept mapping, and exit interviews to rigorously assess student competencies.

Hitt et al. [

51] demonstrate how integrating ethics into the curriculum can be operationalized by using reflective portfolios, peer assessments, and collaborative design challenges, as implemented in their NHV and IDEAS courses at Colorado School of Mines. These courses offer detailed rubrics for evaluating ethical reasoning applied to engineering challenges, thereby ensuring that students systematically develop skills such as stakeholder engagement and contextual analysis. The evolution from NHV (established in 1997) to IDEAS (introduced in 2015) illustrates a strategic curricular refinement: IDEAS merges ethics, communication, design thinking, and problem-based learning in a two-semester sequence with clearly defined learning outcomes and continuous performance assessments.

Examples of successful university collaborations include projects at the UPV in Vitoria, where structured research initiatives investigating environmental solutions and sustainable temperature control employ defined experimental methodologies and performance indicators aligned with SDG priorities.Calvo et al. [

51] further illustrate this with an initiative where students conduct controlled experiments to analyze building thermal comfort and energy consumption, using a cross-disciplinary curriculum that includes rigorous pre- and post-project evaluations to measure learning gains in sustainability concepts.

Delft University of Technology’s 2020 MSc in Robotics [

52] provides a concrete example of multidisciplinary education by combining courses in machine perception, AI, robot planning, human–machine systems, and ethics; project work is assessed via defined milestones and reflective reports that capture student learning and adaptability in real-world scenarios. Notably, the RO47007 Multidisciplinary Project requires students to collaborate with industry partners, with performance benchmarks based on solution effectiveness, innovation, and communication clarity.

Strachan et al. [

43] provide concrete examples of multidisciplinary approaches tied to the SDGs. For instance, elective modules in Infrastructure and Environment introduce real-case analyses, while core modules like Engineering for Global Development use problem-based challenges (e.g., Engineers Without Borders Design Challenge) with structured assessment rubrics. Additionally, Vertical Integration Projects (VIP) at institutions like Purdue University combine research and undergraduate education through clearly defined deliverables, and collaborative projects with industry offer measurable benchmarks for addressing sustainability challenges.

The EDINSOST project [

14] serves as a model by integrating sustainability into curricula across ten Spanish universities (including UPM) through targeted teaching strategies and competency-based assessments, thereby providing empirical data on graduate outcomes related to sustainability skills. When implemented with defined teaching methodologies and clear assessment metrics, this approach not only enhances understanding of sustainability issues but also improves collaboration and innovation in problem-solving, as evidenced by measurable improvements in project outcomes and graduate employability surveys. Moreover, the approach has been linked to improved real-world readiness and increased ethical awareness, although further case studies with quantifiable results would strengthen this conclusion. Detailed studies identifying specific structural barriers and proposed strategies for overcoming them are scarce and warrant further research.

Habash et al. [

53] examined a Phenomenon- and Project-Based Learning (PhenoBL and PBL) model that integrates real-world tasks—developed in collaboration with campus sustainability offices and consulting firms—into design courses. Their study, which utilized both pre- and post-project surveys and performance rubrics, indicates that students value practical applications and interdisciplinary teamwork; however, further quantitative data is needed to confirm the long-term impact on sustainability competencies. Sharma et al. [

5] provide evidence, through multi-method evaluation (including teacher evaluations, concept mapping, and exit interviews), that multidisciplinary sustainability courses enhance students’ ability to address complex challenges. Yet, further research is needed to isolate which elements—such as internship experiences or project work—deliver the most significant improvements. Although these courses boost collaboration and real-world skills, challenges such as inadequate faculty training persist. Scott Stanford et al. [

54] further show that sustainability-focused capstone projects improve learning outcomes; however, they call for the development of standardized assessment criteria to better compare program effectiveness across institutions.

In summary, adopting a multidisciplinary approach to sustainability in engineering education has proven benefits in fostering innovation and ethical responsibility but also faces substantial challenges in resource allocation, curriculum restructuring, and faculty adaptation [

55].Universities are increasingly using diversified strategies—ranging from curriculum redesign and interdisciplinary projects to workshops and experiential learning—to embed SDG principles into engineering programs, though the effectiveness of these approaches requires further empirical validation [

8].. While interdisciplinary collaboration promises a holistic grasp of sustainability, more rigorous case studies with quantifiable outcomes are needed to conclusively link these educational strategies to real-world sustainable engineering practices. Students benefit by acquiring critical skills—such as advanced problem solving and effective communication—through interdisciplinary projects that incorporate standardized assessments and industry feedback.López et al. [

56] illustrate a detailed methodology for integrating sustainability into final-year projects, including the use of an assessment matrix with weighted criteria across environmental, economic, and social dimensions. This matrix, coupled with guided inquiry-based learning, provides tangible metrics for student performance in sustainability. They further propose three strategies for curricular reform: (1) the add-on strategy, which supplements existing courses with sustainability modules; (2) the integration strategy, which creates new interdisciplinary courses through targeted faculty development; and (3) the re-building strategy, which involves comprehensive curriculum overhaul guided by evidence-based frameworks.

UPM provides an illustrative example through its Environmental Sustainability Plan 2018/19, which integrates measurable performance indicators and pilot projects under the leadership of the Vice-Chancellor for Teaching Quality and Management. Its cross-disciplinary center, itdUPM22, not only channels sustainability initiatives but also employs structured project evaluations to monitor its contributions to the SDGs. Through defined innovation protocols and regular external reviews, itdUPM addresses global sustainability challenges with concrete output metrics. For instance, its building at ETSI Agronomic, Food and Biosystems was awarded second prize in the ‘Design’ category at the 2016 World Green Infrastructure Congress, a testament to the institution’s commitment to sustainable design.The Initiative for Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism (

http://habitat.aq.upm.es/iau+s/) further exemplifies its international and interdisciplinary vision by incorporating global design standards and collaborative research.

The CRUE has long prioritized embedding sustainability in Spanish higher education curricula, as documented in its 2005 guidelines—revised in 2012—which lay out actionable criteria for curriculum sustainability. These guidelines define "curriculum sustainability" as the systematic incorporation of sustainability criteria into teaching and learning, with specific recommendations now accompanied by best-practice case studies. The 2012 update further refines this concept by explicitly linking sustainability to environmental quality, social justice, and long-term economic viability, and by recommending four key competencies verified through pilot implementations. Key criteria include the ability to work in multidisciplinary teams, with case studies demonstrating how such teamwork contributes to viable professional alternatives that address socio-environmental challenges. It also stresses the importance of a holistic, systemic approach—validated by outcome metrics—in resolving socio-environmental issues beyond fragmented analyses. The GTSC highlights persistent challenges among faculty in adopting the interdisciplinary practices required for curriculum sustainability, and it calls for targeted training programs to overcome these institutional barriers [

57] [

30]. In April 2023, CRUE’s Application Report of Royal Decree 822/2021 [

58] further reinforces the mandate to include sustainability in curricula, referencing UNESCO’s 2017 framework to establish eight measurable competencies. Spain’s 2018 Action Plan for the 2030 Agenda [

59] and the European Commission’s 2022 GreenComp framework [

2] both underscore the commitment and provide benchmarks for embedding sustainability competencies into university programs.

Finally, the Manifesto of the XXXIII CRUE-Sustainability Conference “University and City: Towards Climate Neutrality” [

60] advocates for refined transdisciplinary research protocols to satisfy Europe’s climate objectives. It mandates that universities become active urban hubs for debate and innovation, explicitly measuring the effectiveness of interdisciplinary approaches in contextualizing and overcoming current and future sustainability challenges.

6. Discussion

Engineering education is undergoing an essential transformation, particularly regarding sustainability. Considering pressing environmental and social challenges, integrating multidisciplinary approaches within engineering curricula has become increasingly pivotal. Various theoretical frameworks for sustainability in engineering education underscore the necessity of broadening traditional engineering pedagogies to encompass perspectives from diverse disciplines, thereby enabling students to engage more holistically with sustainability issues.

One prominent framework is the Systems Thinking approach, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of sustainability challenges through the examination of social, economic, and environmental systems. By incorporating Systems Thinking, educators can encourage students to analyse problems within their broader context, fostering critical engagement with sustainability principles. This method has been recognized for its effectiveness in developing a comprehensive understanding of sustainability that transcends disciplinary boundaries [

55]. It cultivates a mindset among students that recognizes the complexity and interrelated nature of sustainability challenges, potentially leading to more effective problem-solving strategies crucial for engineers [

16].

Another influential theoretical framework is the Challenge-Based Learning (CBL) model, which promotes active engagement through real-world challenges. By applying CBL, students are tasked with seeking solutions to sustainability issues and are encouraged to collaborate across disciplines, reflecting a true multidisciplinary commitment to education. This framework has been shown to enhance learner engagement and foster the development of soft skills, such as teamwork and communication, which are crucial for effective collaboration in diverse teams that address sustainability issues (Castro & Zermeño, 2020). The incorporation of these multifaceted frameworks provides evidence that active learning methodologies can significantly influence students’ understanding and application of sustainability concepts in engineering contexts [

30,

37].

Moreover, the concept of sustainability in education—particularly in engineering—is often scaffolded by initiatives that aim to align educational practices with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Frameworks that emphasize service learning support this alignment, allowing students to engage in community projects that improve local conditions while fostering a practical understanding of sustainability [

42]. The participatory processes advocated in these frameworks underscore the importance of collaboration among students, faculty, and community stakeholders, thereby enriching the educational experience while directly contributing to enhanced social welfare [

4,

27].

By comparing distinct case studies, such as Iowa State University’s engineering program and the Master in Engineering Studies in Mechatronics, we can identify variations in curricular strategies, regional influences, and cultural contexts affecting sustainability education.

At Iowa State University, a commitment to sustainability is evident through collaborative efforts that align engineering curricula with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For instance, the university has utilized methodologies to assess the contributions of educational programs towards achieving SDGs, demonstrating a systematic approach towards curricular integration [

41]. Such frameworks facilitate the identification of strengths and weaknesses in sustainability education across various geographic contexts [

41]. Moreover, the use of active learning methodologies and experiential learning opportunities related to sustainability enhances students’ learning experiences, critical thinking, and practical engagement with sustainability challenges [

8,

37].

In contrast, the Master in Engineering Studies in Mechatronics program emphasizes a distinct multidisciplinary curriculum that captures the intersections of technology and sustainable practices. This program incorporates advanced technologies, such as virtual and remote laboratories, which have been recognized for their potential to enhance sustainability education by providing students with hands-on experience and improving problem-solving skills [

20]. Furthermore, fostering a design-oriented educational environment within this curriculum promotes the critical evaluation of sustainable engineering practices and encourages innovative solutions tailored to regional and cultural contexts [

22].

Culturally, the approaches to sustainability in education can vary significantly based on regional values and societal needs. For instance, institutions in North America, like Iowa State University, may focus more on sustainability from a technological innovation perspective, promoting engineering solutions that align with industrial practices. In contrast, engineering programs in regions with a strong emphasis on ecological sustainability may prioritize systems thinking and community engagement, reflecting a more collective cultural approach to sustainability [

55]. Therefore, it is crucial for engineering programs to remain adaptable and responsive to regional characteristics, ensuring that their educational frameworks align with local and global sustainability agendas [

31].

Finally, the cumulative evidence suggests that enhancing multidisciplinary approaches to sustainability in engineering education requires collaborative efforts among various disciplines and stakeholders. This can be achieved through the integration of learning objectives from engineering, social sciences, economics, and environmental studies, thereby cultivating a holistic view of sustainability that prepares students to tackle diverse challenges effectively [

38,

40]. Ultimately, these approaches not only enrich the educational experience but also empower future engineers to develop solutions that respect both environmental integrity and social equity.

A critical examination of educational methodologies reveals that active learning, project-based learning, and simulation-based learning are all effective strategies for integrating sustainability concepts into engineering education. For instance, engineering courses that include multidisciplinary projects offer students the opportunity to confront dynamic sustainability challenges, urging them to draw from various academic domains to devise comprehensive solutions [

21]. Such strategies have shown promise in not only enhancing students’ technical competencies but also in fostering a deeper appreciation for the ethical and social dimensions of engineering practice [

32].

Despite the advantages of multidisciplinary frameworks, certain challenges hinder their effective implementation. Educational institutions often operate within disciplinary silos, limiting interactions among departments that would facilitate a more holistic approach to sustainability in engineering curricula [

15]. Consequently, overcoming institutional barriers represents a significant hurdle in fostering interdisciplinary collaboration necessary for addressing complex sustainability challenges. To counteract these barriers, fostering a culture of collaboration among faculty and promoting the use of interdisciplinary teaching teams can enhance the academic environment, enriching the educational experience for students [

5,

45].

Furthermore, the evolving landscape of engineering education calls for adopting diverse pedagogical approaches that entail a shift away from traditional lectures toward learner-centric models. This transition aligns closely with the demand for sustainability competencies as outlined by various global initiatives [

20,

48]. Thus, developing innovative curricula that incorporate interdisciplinary elements and experiential learning can better prepare future engineers to meet societal demands and engage with sustainability in multifaceted ways [

31].

In summary, the multidisciplinary approach to sustainability in engineering education holds significant promise for cultivating a new generation of engineers equipped with the requisite skills to tackle pressing societal challenges. The frameworks discussed—from Systems Thinking to Challenge-Based Learning—provide a comprehensive foundation for integrating sustainability concepts within engineering curricula. When aligned with institutional support and innovative pedagogical practices, these approaches can profoundly transform engineering education and foster impactful learning experiences that champion sustainability principles.

The integration of various perspectives within engineering programs can enhance students’ understanding of sustainability, preparing them to confront real-world challenges effectively. However, gaps remain in the current educational frameworks, highlighting a need for further research and development, particularly in the context of emerging technologies like augmented reality (AR) and machine learning (ML).

Firstly, a robust integration of sustainability principles within engineering curricula can cultivate a holistic understanding of the interplay between technical, environmental, and societal dimensions. For instance, Sharma et al. emphasize that sustainability education was originally integrated into civil engineering and environmental disciplines, but is now increasingly recognized across all engineering fields due to growing environmental concerns [

5]. This is echoed by Kioupi and Voulvoulis, who assert that higher education programs must adapt to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), calling attention to the crucial role of multidisciplinary methodologies in achieving sustainability learning outcomes [

41]. Furthermore, Blatti et al. argue for the importance of systems thinking in educational contexts to promote interdisciplinary learning that connects varied fields to sustainability goals [

55].

Despite these advances, significant challenges and gaps remain in effectively implementing multidisciplinary approaches in engineering education. A systematic review by Thürer et al. indicates that while literature exists on integrating sustainability into engineering curricula, many programs still struggle with practical implementations [

16]. This gap emphasizes the need for innovative pedagogical strategies, as highlighted by Carracedo et al., who propose utilizing tools like the Sustainability Matrix to better assess and integrate sustainability competencies within engineering degree programs [

8]. Current pedagogical frameworks often remain siloed, failing to incorporate contemporary skills necessary for sustainability, such as critical thinking and problem-solving [

19].

Emerging technologies offer new pathways for enhancing multidisciplinary education in sustainability. Augmented reality, for example, can create immersive learning experiences that provide students with practical insights into complex systems and real-world sustainability applications. The application of game-based learning methodologies has shown potential in enhancing students’ engagement and perspectives on sustainability [

24]. Additionally, the introduction of machine learning could help analyze vast datasets related to sustainability, fostering a new understanding of the field that students may apply in innovative designs and decision-making processes [

30]. The integration of these technologies into curricula could facilitate a stronger grasp of complex systems and interdisciplinary collaboration, which is critical for addressing global sustainability challenges.

Future research directions should focus on identifying effective strategies for embedding these technologies in higher education curricula while holistically addressing sustainability. Studies like those led by Villacé-Molinero emphasize the need for real-world applications and community engagements to enrich student experiences and align them with SDG targets [

42]. Educational institutions should further explore partnerships with industry and community organizations to develop practical, hands-on experiences that mirror the complexities of sustainable engineering challenges [

48]. Overall, employing a multidisciplinary approach enriched with innovative technologies will be vital in overcoming educational gaps and preparing future engineers to contribute meaningfully to sustainable development.

7. Conclusions

This study underscores that embedding sustainability into engineering education involves far more than revising course content—it requires a fundamental transformation of how we conceptualize and deliver engineering training. Drawing upon multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary approaches, the work demonstrates that integrating insights from diverse academic fields not only enriches the curriculum but also equips future engineers with the critical, ethical, and innovative skills required to address complex socio-environmental challenges.

First, the research shows that a shift in theoretical frameworks—moving beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries toward holistic models—is essential for cultivating systems thinking, ethical reasoning, and problem-solving abilities. By incorporating methodologies that bridge constructivist principles with collaborative and integrative pedagogies, educational programs can foster deeper student engagement and real-world application of sustainable engineering principles. This transformation is evidenced by improved learning outcomes in programs where sustainability is interwoven with practical industry challenges and community-based projects.

Second, the study highlights significant strategic innovations, such as curriculum redesign, project-based learning, and experiential practices, which not only align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) but also respond to the evolving demands of the workforce. However, while these approaches have shown promise in case studies across various institutions, challenges persist—especially regarding resource allocation, faculty training, and institutional inertia. The need for continuous professional development and adaptive policies emerges as a critical factor in operationalizing these innovative educational models on a broader scale.

Furthermore, the presented analysis reveals that embracing ethical and cultural dimensions is as crucial as integrating advanced educational technologies. The inclusion of digital tools, such as augmented reality and data-driven learning platforms, has the potential to create immersive and interactive experiences; yet, their effectiveness remains underexplored. Addressing such gaps requires further empirical studies to validate how these technologies can synergize with traditional pedagogical methods, thereby enhancing the overall quality of sustainability education.

Finally, while the current findings affirm the positive impact of multidisciplinary strategies on student competencies, they also pave the way for several avenues of future research. Investigations into long-term learning outcomes, the scalability of innovative curricula across diverse educational settings, and the optimization of cross-sector partnerships between academia and industry are particularly warranted. Such research endeavors will be crucial in refining these educational approaches and ensuring that they can adapt to the rapid technological and societal changes of the 21st century.

In summary, this study provides a robust foundation for rethinking engineering education through the lens of sustainability. By integrating theoretical evolution with pragmatic innovations and ethical considerations, it sets the stage for training engineers who are not only technologically proficient but also responsible and adaptive change agents. The insights gained here offer a comprehensive roadmap for academic institutions aiming to bridge the gap between technical acumen and the broader imperatives of sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M. and A.A.;.; methodology, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M. and A.A.; validation, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M. and A.A. ; investigation, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; F.C-M.; A.M.;R.D. and A.A.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, S.M.,A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-funded by the European Union under the Erasmus+ Engineering Education for a Sustainable Future project - Project number: 2023-1-IE02-KA220-HED-000160939.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CRUE |

Consejo de Rectores de Universidades Españolas (Universities Chancellors Council)

|

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| UPV |

Universidad del País Vasco |

References

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal. ESDN Rep. Dec. 2020, 2, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, G.; Pisiotis, U.; Cabrera Giraldez, M. GreenComp The European Sustainability Competence Framework; Joint Research Centre (Seville site), 2022.

- Falegnami, A.; Romano, E.; Tomassi, A. The Emergence of the GreenSCENT Competence Framework. In The European Green Deal in Education; Routledge, 2024; pp. 204–216 ISBN 978-1-003-49259-7.

- Strachan, S.; Logan, L.; Willison, D.; Bain, R.; Roberts, J.; Mitchell, I.; Yarr, R. Reflections on Developing a Collaborative Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Embedding Education for Sustainable Development into Higher Education Curricula. Emerald Open Res. 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Steward, B.; Ong, S.K.; Miguez, F.E. Evaluation of Teaching Approach and Student Learning in a Multidisciplinary Sustainable Engineering Course. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4032–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahedo García, V.; Álvarez, M.; Arinyo i Prats, A.; Barceló, J.A.; Bocanegra Barbecho, L.; Bogdánovic, I.; Briz i Godino, I.; Capuzzo, G.; Caro Saiz, J.; Castillo Bernal, M.F. del; et al. Terra Incognita: Libro Blanco Sobre Transdisciplinariedad y Nuevas Formas de Investigación En El Sistema Español de Ciencia y Tecnología. 2020.

- GreenComp: The European Sustainability Competence Framework - European Commission. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/greencomp-european-sustainability-competence-framework_en (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Sánchez-Carracedo, F.; López, D.; Martín, C.; Vidal, E.; Cabré, J.; Climent, J. The Sustainability Matrix: A Tool for Integrating and Assessing Sustainability in the Bachelor and Master Theses of Engineering Degrees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Zeng, S.; Grima-Olmedo, J.; Grima-Olmedo, C. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Applied to Mechanical Engineering. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Soc. Technol. Sci. 2022, 9, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W. Incorporation of Sustainability Concepts into a Civil Engineering Curriculum. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2007, 133, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO publishing, 2017.

- Kolmos, A. Engineering Education for the Future. In Engineering for sustainable development: Delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals; UNESCO, 2021; pp. 121–128.

- Dorst, K. Frame Innovation: Create New Thinking by Design; MIT press, 2015.

- Segalàs Coral, J.; Sánchez Carracedo, F. The EDINSOST Project: Improving Sustainability Education in Spanish Higher Education.; 2019; pp. 217–240.

- Feng, X.; Ylirisku, S.; Kähkönen, E.; Niemi, H.; Hölttä-Otto, K. Multidisciplinary Education through Faculty Members’ Conceptualisations of and Experiences in Engineering Education. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2023, 48, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürer, M.; Tomašević, I.; Stevenson, M.; Qu, T.; Huisingh, D. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Integrating Sustainability into Engineering Curricula. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, B.; Hopwood, B.; O’Brien, G. Environment, Economy and Society: Fitting Them Together into Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2002, 10, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronek, M.; Gilberti, R.M.; Petro, M.; Sancomb, C.; Maddern, S.; Jankovic, J. Inclusive STEAM Education in Diverse Disciplines of Sustainable Energy and AI. Energy AI 2022, 7, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, S.E.; Metzger, E.P. Barriers to Learning for Sustainability: A Teacher Perspective. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poo, M.C.; Lau, Y.; Chen, Q. Are Virtual Laboratories and Remote Laboratories Enhancing the Quality of Sustainability Education? Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, I.; Carrascal, E.; González, J.M.; Armentia, A.; Gil-García, J.M.; Barambones, Ó.; Basogain, X.; Tazo-Herran, I.; Apiñaniz, E. A Methodology to Introduce Sustainable Development Goals in Engineering Degrees by Means of Multidisciplinary Projects. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.-N.; Nagatomo, D. Study of STEM for Sustainability in Design Education: Framework for Student Learning and Outcomes With Design for a Disaster Project. Sustainability 2021, 14, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.P.; Zermeño, M.G.G. Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability Through E-Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scurati, G.W.; Kwok, S.Y.; Ferrise, F.; Bertoni, M. A Study on the Potential of Game Based Learning for Sustainability Education. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratinen, I.; Sarivaara, E.; Kuukkanen, P. Finnish Student Teachers’ Ideas of Outdoor Learning. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2021, 23, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoller, U. Science Education for Global Sustainability: What Is Necessary for Teaching, Learning, and Assessment Strategies? J. Chem. Educ. 2012, 89, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.; Brown, P.; Benn, S.; Bajada, C.; Perey, R.; Cotton, D.; Jarvis, W.; Menzies, G.; McGregor, I.; Waite, K. Developing Sustainability Learning in Business School Curricula – Productive Boundary Objects and Participatory Processes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 26, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.; Suárez-Collado, Á. Understanding Economic, Social, and Environmental Sustainability Challenges in the Global South. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielefeldt, A. Pedagogies to Achieve Sustainability Learning Outcomes in Civil and Environmental Engineering Students. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4479–4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanovas, M.M.; Ruiz-Munzón, N.; Buil, M. Higher Education: The Best Practices for Fostering Competences for Sustainable Development Through the Use of Active Learning Methodologies. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 23, 703–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, N.; Brusca, I.; Barrafón, M.L. Drivers for Universities’ Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Analysis of Spanish Public Universities. Sustainability 2020, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, E.G.; Jiménez-Fontana, R. María del Pilar Azcárate Goded Education for Sustainability and the Sustainable Development Goals: Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions and Knowledge. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Á.A.; Helldén, D.; Alfvén, T.; Niemi, M.; Leander, K.; Nordenstedt, H.; Rehn, C.; Ndejjo, R.; Wanyenze, R.K.; Biermann, O. Integrating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Into Higher Education Globally: A Scoping Review. Glob. Health Action 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Estévez, M.; Chalmeta, R. Integrating Sustainable Development Goals in Educational Institutions. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indahwati, S.D.; Rachmadıartı, F.; Hariyono, E.; Prahanı, B.K.; Wıbowo, F.C.; Bunyamin, M.A.H.; Satriawan, M. Integration of Independent Learning and Physics Innovation in STEAM-Based Renewable Energy Education to Improve Critical Thinking Skills in the Era of Society 5.0 for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030. E3s Web Conf. 2023, 450, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A. The Application of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education) in BS English Language & Literature Curriculum. Pak. Lang. Humanit. Rev. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrero, R.; Junguitu-Angulo, L.; Osuna-Acedo, S. Deploying SDG Knowledge to Foster Young People’s Critical Values: A Study on Social Trends About SDGs in an Educational Online Activity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.C.L.; Costa, P.; Simões, J.; Loureiro, R. The Interrelationships Between the Sustainable Development Goals and Higher Education Institutions: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Educ. Train. 2022, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.S.; Subbanna, Y.B.; Rathore, S.; Kumar, V.V.S.; Kumar, S.; Vinayagam, S.S.; Rakesh, S.; Balasani, R.; Raju, D.T.; Kumar, A.; et al. Academia-Industry Linkages for Sustainable Innovation in Agriculture Higher Education in India. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarizi, M.; Yuniarty, Y. Literature Review of Climate Change and Indonesia’s SDGs Strategic Issues in a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Iop Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1105, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Voulvoulis, N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Assessing the Contribution of Higher Education Programmes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacé-Molinero, T.; Moraleda, L.F.; Orea-Giner, A.; Sánchez, R.G.; Mazón, A.I.M. Service Learning via Tourism Volunteering at University: Skill-Transformation and SDGs Alignment Through Rite of Passage Approach. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2023, 15, 34–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, S.; Logan, L.; Willison, D.; Bain, R.; Roberts, J.; Mitchell, I.; Yarr, R. Reflections on Developing a Collaborative Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Embedding Education for Sustainable Development into Higher Education Curricula. Emerald Open Res. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFCA Future Trends in the Consulting Engineering Industry 2018.

- Kolmos, A.; Hadgraft, R.G.; Holgaard, J.E. Response Strategies for Curriculum Change in Engineering. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2016, 26, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.; Ong, S.K.; Steward, B.L. Student Learning in a Multidisciplinary Sustainable Engineering Course. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2011, 137, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, K.; Voglewede, P. Multidisciplinary Engineering Systems Graduate Education: Master of Engineering in Mechatronics. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Transforming Engineering Education: Creating Interdisciplinary Skills for Complex Global Environments; IEEE: Dublin, Ireland, April 2010; pp. 1–14.

- MacDonald, L.; Thomas, E.; Javernick-Will, A.; Austin-Breneman, J.; Aranda, I.; Salvinelli, C.; Klees, R.; Walters, J.; Parmentier, M.J.; Schaad, D.; et al. Aligning Learning Objectives and Approaches in Global Engineering Graduate Programs: Review and Recommendations by an Interdisciplinary Working Group. Dev. Eng. 2022, 7, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, M. BLOOM’S TAXONOMY. Curric. Teach. Dialogue 2011, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Badurdeen, F.; Sekulic, D.; Gregory, B.; Brown, A.; Fu, H. Developing and Teaching a Multidisciplinary Course in Systems Thinking for Sustainability: Lessons Learned through Two Iterations. In Proceedings of the 2014 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings; ASEE Conferences: Indianapolis, Indiana, June 2014; p. 24.392.1-24.392.22.

- Hitt, S.J.; Holles, C.E.P.; Lefton, T. Integrating Ethics in Engineering Education through Multidisciplinary Synthesis, Collaboration, and Reflective Portfolios. Adv. Eng. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Niet, A.; Claij, C.; Saunders-Smits, G. Educating Future Robotics Engineers In Multidisciplinary Approaches In Robot Software Design. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Habash, R.; Hasan, M.M.; Chiasson, J.; Tannous, M. Phenomenon- and Project-Based Learning Through the Lens of Sustainability. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 38, 110–116. [Google Scholar]

- Scott Stanford, M.; Benson, L.C.; Alluri, P.; Martin, W.D.; Klotz, L.E.; Ogle, J.H.; Kaye, N.; Sarasua, W.; Schiff, S. Evaluating Student and Faculty Outcomes for a Real-World Capstone Project with Sustainability Considerations. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2013, 139, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatti, J.L.; Garcia, J.; Cave, D.; Monge, F.; Cuccinello, A.; Portillo, J.; Juarez, B.; Chan, E.; Schwebel, F. Systems Thinking in Science Education and Outreach toward a Sustainable Future. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, D.; Sanchez, F.; Vidal, E.; Pegueroles, J.; Alier, M.; Cabre, J.; Garcia, J.; Garcia, H. A Methodology to Introduce Sustainability into the Final Year Project to Foster Sustainable Engineering Projects. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) Proceedings; IEEE: Madrid, Spain, October 2014; pp. 1–7.

- Barrón Ruíz, Á.; Navarrete, A.; Ferrer-Balas, D.; others Sostenibilización Curricular En Las Universidades Españolas.?` Ha Llegado La Hora de Actuar? 2010.

- del Estado, B.O. Real Decreto 822/2021, de 28 de Septiembre, Por El Que Se Establece La Organización de Las Enseñanzas Universitarias y Del Procedimiento de Aseguramiento de Su Calidad. Bol. Of. Estado 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GOBIERNO, D.E. Plan de Acción Para La Implementación de La Agenda 2030. Hacia Una Estrateg. Esp. Desarro. Sosten. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UPV Manifiesto de Las XXXIII Jornadas de Crue-Sostenibilidad «Universidad y Ciudad: Hacia La Neutralidad Climática 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).