Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

23 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Commonalities in the Molecular Phenomena Underlying ESC and MSC

3. Evidence That ESC and MSC(R) Are Variants of the Same Underlying Phenomenon

3.1. Swelling and Diffusion Responses Driven by Chemical Potential Gradients

3.2. Path-Independence of Loading and Swelling

3.3. Experimental Studies Spanning the ESC–MSC Transition

4. Requirements of Constitutive Models for MSP

- Validity across the glass transition: To capture the viscoelastic, viscoplastic and fracture behavior across the glass transition as a function of mechanical stress, loading frequency, temperature, and crucially, the fluid concentration.

- Volume change independence: The polymer-fluid system volume is not equal to the sum of the volumes of the dry polymer and the solvent during the dry-to-wet transition, in contrast to the case of a hydrogel whose free volume is already saturated.

- Fluid concentration dependent properties: Both viscous and elastic properties evolve strongly across the glass transition during the dry-to-wet transition of the polymer. The model should incorporate the effect of fluid sorption on viscoplasticity, damage and fracture. The model should also incorporate the appropriate plastic behavior to capture the irreversible part of MSC associated with bound solvent.

- Built from a molecular basis: The model parameters can be traced back to the fundamental physical and chemical descriptors of the polymer and fluid.

- Fit into a computational framework capable of handling both fracture and large deformation: To be able to seamlessly transition from an ESC type brittle fracture to an ESY/MSCR type ductile failure.

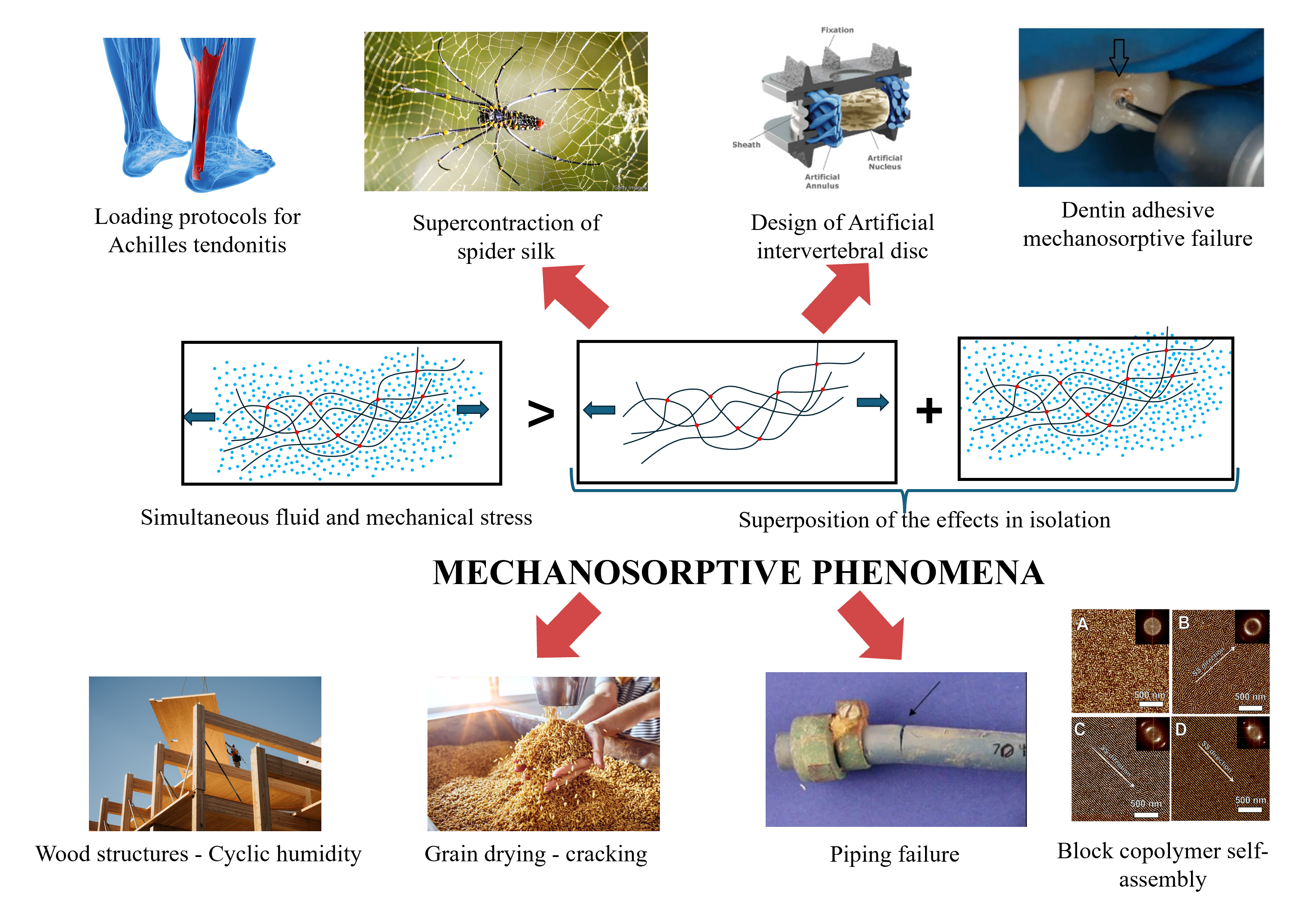

5. Applications of MSP for Biomimetic Materials

6. Discussion

- For the first time, several seemingly disparate mechanosorptive phenomena from a variety of applications have been brought together under a single review. The interrelationship between several terminologies used in literature including MSC, MSCR, ESY, SEDS, and ESC have been explained.

- MSCR and ESC have been identified as two extremes of the same underlying phenomenon with supporting evidence from a large body of studies from a variety of fields. Several experimental results which show responses resembling ESC and MSCR/ESY for the same polymer for different solvents or different sorption of the same solvent have been reproduced here to justify this conclusion.

- For the first time, it has been hypothesized that the reversible parts of MSC, ESY or SEDS can be explained by the equilibrium swelling of polymer networks. Only the irreversible part of the MSC necessitates the rate of solvent sorption as a constitutive variable. Irreversibility can also arise from plastic yielding. Once proven, this hypothesis is expected to greatly simplify constitutive modelling of MSP.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSP | Mechano-sorptive phenomena |

| ESC | Environmental stress cracking |

| MSC | Mechano-sorptive creep |

| ESY | Environmental Stress Yielding |

| MSCR | Mechano-sorptive creep rupture |

| SEDS | Stress-enhanced diffusion and solubility/swelling |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) |

| SCP | Semicrystalline polymer |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| BCP | Block copolymer thin film |

References

- P. Spencer and Y. Wang, “Adhesive phase separation at the dentin interface under wet bonding conditions,” J Biomed Mater Res, vol. 62, no. 3, pp. 447–456, 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Y. Rudakova and G. Y. Zaikov, “Effect of an aggressive medium and mechanical stress on polymers. Review,” Polymer Science USSR, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 1987. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Robeson, “Environmental stress cracking: A review,” 2013, John Wiley and Sons Inc. doi: 10.1002/pen.23284. [CrossRef]

- Almomani A, Mourad AHI, Deveci S, Wee JW, and Choi BH, “Recent advances in slow crack growth modeling of polyethylene materials,” Mar. 01, 2023, Elsevier Ltd. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2023.111720. [CrossRef]

- A. Mårtensson, “Mechano-sorptive effects in wooden material,” Wood Sci Technol, vol. 28, no. 6, Sep. 1994, doi: 10.1007/BF00225463. [CrossRef]

- FU HB, “Effect of external stress on the transport of fluids in poly aryl ether ether ketone(PEEK),” Michigan Technological University, Houghton, 1995.

- Wolf CJ and Fu HB, “Stress-enhanced transport of toluene in poly aryl ether ether ketone (PEEK),” J Polym Sci B Polym Phys, vol. 34, no. 75–82, pp. 75–82, Jan. 1996, doi: doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0488(19960115)34:1<75::AID-POLB5>3.0.CO;2-V. [CrossRef]

- Wolf CJ and Grayson MA, “Solubility, diffusion and swelling of fluids in thermoplastic resin systems*,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 746–751, Feb. 1993, doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(93)90358-H. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Wright, Environmental stress cracking of plastics. iSmithers Rapra Publishing, 1996.

- Hargreaves AS, “The effect of the environment on the crack initiation toughness of dental poly(methyl methacrylate),” J Biomed Mater Res, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 757–768, 1981, doi: 10.1002/jbm.820150511. [CrossRef]

- Singh V, Misra A, Parthasarathy R, Ye Q, Park J, and Spencer P, “Mechanical properties of methacrylate-based model dentin adhesives: Effect of loading rate and moisture exposure,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, vol. 101, no. 8, pp. 1437–1443, Nov. 2013, doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32963. [CrossRef]

- Entwistle KM and Zadoroshnyj A, “The recovery of mechano-sorptive creep strains,” J Mater Sci, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 967–973, Feb. 2008, doi: 10.1007/s10853-007-2138-0. [CrossRef]

- Toratti T, “Mechano-sorptive creep rupture,” Rakenteiden Mekaniikka, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 3–11, 1992.

- Hearmon RFS and Paton JM, “Moisture content changes and creep of wood,” For Prod J, vol. 14, no. 8, 1964.

- Hassani MM, Wittel FK, Hering S, and Herrmann HJ, “Rheological Model for Wood,” Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng, vol. 283, 2015, doi: doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2014.10.031. [CrossRef]

- Stevanic JS and Salmén L, “Molecular origin of mechano-sorptive creep in cellulosic fibres,” Carbohydr Polym, vol. 230, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115615. [CrossRef]

- Frilette VJ, Hanle J, and Mark H, “Rate of exchange of cellulose with heavy water,” J Am Chem Soc, vol. 70, p. 25, 1948, [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines.

- Reichel S and Kaliske M, “Hygro-mechanically coupled modelling of creep in wooden structures, Part I: Mechanics,” Int J Solids Struct, vol. 77, pp. 28–44, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2015.07.019. [CrossRef]

- Reichel S and Kaliske M, “Hygro-mechanically coupled modelling of creep in wooden structures, Part II: Influence of moisture content,” Int J Solids Struct, vol. 77, pp. 45–64, Dec. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2015.07.029. [CrossRef]

- Crank J and Park GS, Diffusion in Polymers. Academic Press, 1968.

- L. M. Robeson, “Environmental stress cracking: A review,” Polym Eng Sci, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 453–467, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Flory PJ, Principles of Polymer Chemistry. New York: Cornell University, 1953.

- A. N. Gent, “Hypothetical mechanism of crazing in glassy plastics,” J Mater Sci, vol. 5, pp. 925–932, 1970. [CrossRef]

- A. I. Soshko, G. I. Saner, N. G. Kalinin, and A. N. Tynnyi, “Estimation of the durability of polymer materials in liquid media,” Soviet materials science: a transl. of Fiziko-khimicheskaya mekhanika materialov/Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 532–534, 1967. [CrossRef]

- C. Wolf, “Effect of External Stress on the Transport of Fluids in Thermoplastic Resin Systems,” Michigan, 1994.

- C. J. Wolf and H. Fu, “Stress-enhanced transport of toluene in poly aryl ether ether ketone (PEEK),” J Polym Sci B Polym Phys, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 75–82, 1996.

- C. J. Wolf and M. A. Grayson, “Solubility, diffusion and swelling of fluids in thermoplastic resin systems,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 746–751, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Y.-H. Lin, Polymer viscoelasticity: basics, molecular theories, experiments and simulations. World Scientific, 2010.

- Flory PJ, “Network structure and the elastic properties of vulcanized rubber,” Chem Rev, vol. 35, pp. 51–75, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Gee G, “The interaction between rubber and liquids. X. Some new experimental tests of a statistical thermodynamic theory of rubber-liquid systems,” Transactions of the Faraday Society, vol. 42, pp. 33–44, 1946, doi: 10.1039/tf946420b033. [CrossRef]

- Fujine M, Takigawa T, and Urayama K, “Strain-driven swelling and accompanying stress reduction in polymer gels under biaxial stretching,” Macromolecules, vol. 48, no. 11, pp. 3622–3628, Jun. 2015, doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00642. [CrossRef]

- Lejcuś K, Śpitalniak M, and Dabrowska J, “Swelling behaviour of superabsorbent polymers for soil amendment under different loads,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 10, no. 3, Mar. 2018, doi: 10.3390/polym10030271. [CrossRef]

- Soshko AI, Saner GI, Kalinin NG, and Tynnyi AN, “Estimation of the durability of polymer materials in liquid media,” Soviet Materials Science, vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 532–534, 1968, doi: 10.1007/BF01156420. [CrossRef]

- Wolf CT, “Effect of External Stress on the Transport of Fluids in Thermoplastic Resin Systems,” 1994.

- A. S. Krausz, “The theory of non-steady state fracture propagation rate,” Int J Fract, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 239–242, 1976. [CrossRef]

- A. Tobolsky and H. Eyring, “Mechanical properties of polymeric materials,” Journal of Chemical Physics, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 125–134, 1943.

- L. R. G. Treloar, “The mechanics of rubber elasticity,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, vol. 351, no. 1666, pp. 301–330, 1976.

- L. R. G. Treloar, “The physics of rubber elasticity,” 1975.

- T. Toratti and R. Mekaniikka, “Mechano-Sorptive Creep Rupture,” Rakenteiden mekaniikka, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 3–11, 1992.

- K. Fukumori, T. Kurauchi, and O. Kamigaito, “Swelling behaviour of rubber vulcanizates: 2. Effects of tensile strain on swelling,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 31, no. 12, pp. 2361–2367, 1990. [CrossRef]

- C. Montero, J. Gril, C. Legeas, D. G. Hunt, and B. Clair, “Influence of hygromechanical history on the longitudinal mechanosorptive creep of wood,” Holzforschung, vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 757–764, 2012. [CrossRef]

- V. Singh, A. Misra, R. Parthasarathy, Q. Ye, J. Park, and P. Spencer, “Mechanical properties of methacrylate-based model dentin adhesives: Effect of loading rate and moisture exposure,” J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater, vol. 101, no. 8, pp. 1437–1443, 2013. [CrossRef]

- R. Parthasarathy, A. Misra, L. Song, Q. Ye, and P. Spencer, “Structure-property relationships for wet dentin adhesive polymers,” Biointerphases, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 61001–61004, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Armstrong and G. N. Christensen, “Influence of moisture changes on deformation of wood under stress.,” 1961. [CrossRef]

- M. Fujine, T. Takigawa, and K. Urayama, “Strain-driven swelling and accompanying stress reduction in polymer gels under biaxial stretching,” Macromolecules, vol. 48, no. 11, pp. 3622–3628, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Urayama and T. Takigawa, “Volume of polymer gels coupled to deformation,” Soft Matter, vol. 8, no. 31, pp. 8017–8029, 2012. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Flory, “Network Structure and the Elastic Properties of Vulcanized Rubber.,” Chem Rev, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 51–75, 1944. [CrossRef]

- G. Gee, “The interaction between rubber and liquids. X. Some new experimental tests of a statistical thermodynamic theory of rubber-liquid systems,” Transactions of the Faraday Society, vol. 42, pp. B033–B044, 1946. [CrossRef]

- R. H. Pritchard and E. M. Terentjev, “Swelling and de-swelling of gels under external elastic deformation,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 54, no. 26, pp. 6954–6960, Dec. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.11.006. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma et al., “Delayed tensile instabilities of hydrogels,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 168, Nov. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.jmps.2022.105052. [CrossRef]

- A. D. Drozdov, P. Sommer-Larsen, J. D. Christiansen, and C. G. Sanporean, “Time-dependent response of hydrogels under constrained swelling,” J Appl Phys, vol. 115, no. 23, Jun. 2014, doi: 10.1063/1.4884615. [CrossRef]

- P. Pekarski, A. Tkachenko, and Y. Rabin, “Deformation-Induced Anomalous Swelling of Topologically Disordered Gels,” 1994. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines.

- Xu S, Zhou Z, Liu ZS, and Sharma P, “Concurrent stiffening and softening in hydrogels under dehydration,” Science Adcances, vol. 9, no. 1, 2023, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.ade324. [CrossRef]

- M. Rossi, P. Nardinocchi, and T. Wallmersperger, “Swelling and shrinking in prestressed polymer gels: An incremental stress-diffusion analysis,” Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, vol. 475, no. 2230, 2019, doi: 10.1098/rspa.2019.0174. [CrossRef]

- Takigawa T, Urayama K, Morino Y, and Masuda T, “Simultaneous swelling and stress relaxation behavior of uniaxially stretched polymer gels,” Polym J, vol. 25, no. 9, pp. 929–937, 1993, doi: 10.1295/polymj.25.929. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Arnold, “The effects of diffusion on environmental stress crack initiation in PMMA,” J Mater Sci, vol. 33, no. 21, pp. 5193–5204, 1998. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Arnold, J. Li, and D. H. Isaac, “The effects of pre-immersion in hostile environments on the ESC behaviour of urethane-acrylic polymers,” J Mater Process Technol, vol. 56, no. 1–4, pp. 126–135, 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Arnold, “The influence of liquid uptake on environmental stress cracking of glassy polymers,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 197, no. 1, pp. 119–124, 1995. [CrossRef]

- M. Schilling, “Environmental Stress Cracking (ESC) and Slow Crack Growth (SCG) of PE-HD induced by external fluids,” Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und-prüfung (BAM), 2020.

- M. Schilling, N. Marschall, U. Niebergall, V. Wachtendorf, and M. Böhning, “Characteristics of environmental stress cracking of PE-HD induced by biodiesel and diesel fuels,” Polym Test, vol. 138, p. 108547, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Misra and V. Singh, “Micromechanical model for viscoelastic materials undergoing damage,” Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics, vol. 25, no. 2–4, pp. 343–358, 2013. [CrossRef]

- A. Misra, V. Singh, R. Parthasarathy, O. Marangos, and P. Spencer, “Mathematical model for anomalous creep in model dentin adhesives,” Journal of Dental Research. A, vol. 90, 2011.

- S. Reichel and M. Kaliske, “Hygro-mechanically coupled modelling of creep in wooden structures, Part I: Mechanics,” Int J Solids Struct, vol. 77, pp. 28–44, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. P. Buckley and D. C. Jones, “Glass-rubber constitutive model for amorphous polymers near the glass transition,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 36, no. 17, pp. 3301–3312, 1995.

- L. Mascia, Y. Kouparitsas, D. Nocita, and X. Bao, “Antiplasticization of polymer materials: Structural aspects and effects on mechanical and diffusion-controlled properties,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 12, no. 4, p. 769, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rudakova TY and Zaikov GY, “Effect of an aggressive medium and mechanical stress on polymers. Review,” Polymer Science U.S.S.R., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 1–19, Jan. 1987, doi: 10.1016/0032-3950(87)90074-8. [CrossRef]

- Rudakova TE and Zaikov GE, “Stressed polymers in physically active media,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 105–120, Jan. 1988, doi: 10.1016/0141-3910(88)90043-2. [CrossRef]

- Ward AL, Lu X, Huang Y, and Brown N, “The mechanism of slow crack growth in polyethylene by an environmental stress cracking agent,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 2172–2178, 1991, doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(91)90043-I. [CrossRef]

- Breen J, “Environmental stress cracking of PVC and PVC-CPE,” J Mater Sci, vol. 28, no. 14, pp. 3769–3776, Jul. 1993, doi: 10.1007/BF00353177. [CrossRef]

- Breen J, “Environmental stress cracking of PVC and PVC-CPE,” J Mater Sci, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 39–46, 1994, doi: 10.1007/BF00356570. [CrossRef]

- Breen J, “Environmental stress cracking of PVC and PVC-CPE,” J Mater Sci, vol. 30, no. 22, pp. 5833–5840, Nov. 1995, doi: 10.1007/BF00356729. [CrossRef]

- Breen J and Van Dijk DJ, “Environmental stress cracking of PVC: effects of natural gas with different amounts of benzene,” J Mater Sci, vol. 26, no. 19, pp. 5212–5220, Oct. 1991, doi: 10.1007/BF01143215. [CrossRef]

- Arnold JC, “The influence of liquid uptake on environmental stress cracking of glassy polymers,” Materials Science and Engineering: A, vol. 197, no. 1, pp. 119–124, Sep. 1995, doi: 10.1016/0921-5093(94)09759-3. [CrossRef]

- Schilling M, Marschall N, Niebergall U, Wachtendorf V, and Böhning M, “Characteristics of environmental stress cracking of PE-HD induced by biodiesel and diesel fuels,” Polym Test, vol. 138, Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2024.108547. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Al-Saidi, K. Mortensen, and K. Almdal, “Environmental stress cracking resistance. Behaviour of polycarbonate in different chemicals by determination of the time-dependence of stress at constant strains,” Polym Degrad Stab, vol. 82, no. 3, pp. 451–461, 2003. [CrossRef]

- L. Andena, M. Rink, C. Marano, F. Briatico-Vangosa, and L. Castellani, “Effect of processing on the environmental stress cracking resistance of high-impact polystyrene,” Polym Test, vol. 54, pp. 40–47, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharif, N. Mohammadi, and S. R. Ghaffarian, “Practical work of crack growth and environmental stress cracking resistance of semicrystalline polymers,” J Appl Polym Sci, vol. 110, no. 5, pp. 2756–2762, 2008. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Dupaix and M. C. Boyce, “Constitutive modeling of the finite strain behavior of amorphous polymers in and above the glass transition,” Mechanics of Materials, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 39–52, 2007. [CrossRef]

- V. Srivastava, S. A. Chester, N. M. Ames, and L. Anand, “A thermo-mechanically-coupled large-deformation theory for amorphous polymers in a temperature range which spans their glass transition,” Int J Plast, vol. 26, no. 8, pp. 1138–1182, 2010. [CrossRef]

- S. Das and D. Roy, “A poroviscoelasticity model based on effective temperature for water and temperature driven phase transition in hydrogels,” Int J Mech Sci, vol. 196, p. 106290, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Chen and K. S. Schweizer, “Microscopic constitutive equation theory for the nonlinear mechanical response of polymer glasses,” Macromolecules, vol. 41, no. 15, pp. 5908–5918, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, K. Gall, M. L. Dunn, A. R. Greenberg, and J. Diani, “Thermomechanics of shape memory polymers: uniaxial experiments and constitutive modeling,” Int J Plast, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 279–313, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Govindjee and J. C. Simo, “Coupled stress-diffusion: Case II,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 863–887, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Weitsman Y, “Stress assisted diffusion in elastic and viscoelastic materials,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 73–93, 1987, doi: 10.1016/0022-5096(87)90029-9. [CrossRef]

- Weitsman Y, “A continuum diffusion model for viscoelastic materials,” J Phys Chem, vol. 94, no. 2, pp. 961–968, Jan. 1990, doi: 10.1021/j100365a085. [CrossRef]

- Govindjee S and Simo JC, “Coupled stress-diffusion: case II,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 41, no. 5, pp. 863–887, May 1993, doi: 10.1016/0022-5096(93)90003-X. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Ball, M. Doi, S. F. Edwards, and M. Warner, “Elasticity of entangled networks,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1010–1018, 1981.

- F. Tanaka and S. F. Edwards, “Viscoelastic properties of physically crosslinked networks. 1. Transient network theory,” Macromolecules, vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 1516–1523, 1992. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Brereton and P. G. Klein, “Analysis of the rubber elasticity of polyethylene networks based on the slip link model of SF Edwards et al.,” Polymer (Guildf), vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 970–974, 1988. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Cai, B. Su, L. Zou, M. J. Webber, S. C. Heilshorn, and A. J. Spakowitz, “Rheological characterization and theoretical modeling establish molecular design rules for tailored dynamically associating polymers,” ACS Cent Sci, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1318–1327, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Bonnaillie and P. M. Tomasula, “Application of humidity-controlled dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA-RH) to moisture-sensitive edible casein films for use in food packaging,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 91–114, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Wee and B. H. Choi, “Numerical simulation of discontinuous slow crack growth of semi-elliptical surface crack in polyethylene based on crack layer theory,” in 75th Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition of the Society of Plastics Engineers, SPE ANTEC Anaheim 2017, 2017, pp. 2005–2008.

- A. Chudnovsky and Y. Shulkin, “Application of the crack layer theory to modeling of slow crack growth in polyethylene,” Int J Fract, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 83–102, 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. Ciavarella, G. Cricr\`\i, and R. McMeeking, “A comparison of crack propagation theories in viscoelastic materials,” Theoretical and applied fracture mechanics, vol. 116, p. 103113, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. G. Knauss, “A review of fracture in viscoelastic materials,” Int J Fract, vol. 196, no. 1, pp. 99–146, 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Schapery, “A theory of crack initiation and growth in viscoelastic media: I. Theoretical development,” Int J Fract, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 141–159, 1975.

- R. A. Schapery, “A theory of crack initiation and growth in viscoelastic media II. Approximate methods of analysis,” Int J Fract, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 369–388, 1975. [CrossRef]

- B. R. A. Schapery, “Correspondence principles and a generalized J integral for large deformation and fracture analysis of viscoelastic media,” Int J Fract, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 195–223, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Yin and M. Kaliske, “Fracture simulation of viscoelastic polymers by the phase-field method,” Comput Mech, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 293–309, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Ben Said, H. Hentati, M. Wali, B. Ayadi, and M. Alhadri, “Damage Investigation in PMMA Polymer: Experimental and Phase-Field Approaches,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 23, p. 3304, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Hong and X. Wang, “A phase-field model for systems with coupled large deformation and mass transport,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 61, no. 6, pp. 1281–1294, 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. Ciambella, G. Lancioni, and N. Stortini, “A finite viscoelastic phase-field model for prediction of crack propagation speed in elastomers,” European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids, p. 105678, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Ciambella, G. Lancioni, and N. Stortini, “A finite viscoelastic phase-field model for prediction of crack propagation speed in elastomers,” European Journal of Mechanics-A/Solids, p. 105678, 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Eid, A. Gravouil, and G. Molnár, “Influence of rate-dependent damage phase-field on the limiting crack-tip velocity in dynamic fracture,” Eng Fract Mech, vol. 292, p. 109620, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Arunachala, S. Abrari Vajari, M. Neuner, J. S. Sim, R. Zhao, and C. Linder, “A multiscale anisotropic polymer network model coupled with phase field fracture,” Int J Numer Methods Eng, vol. 125, no. 13, p. e7488, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Mai and S. Soghrati, “A phase field model for simulating the stress corrosion cracking initiated from pits,” Corros Sci, vol. 125, pp. 87–98, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Nguyen et al., “A phase field method for modeling anodic dissolution induced stress corrosion crack propagation,” Corros Sci, vol. 132, pp. 146–160, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Aurojyoti, A. Rajagopal, and K. S. S. Reddy, “Modeling fracture in polymeric material using phase field method based on critical stretch criterion,” Int J Solids Struct, vol. 270, p. 112216, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. D. Huynh and R. Abedi, “Rate dependency and fragmentation response of phase field models with micro inertia and micro viscosity terms,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 196, p. 105971, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. De Meo, C. Diyaroglu, N. Zhu, E. Oterkus, and M. A. Siddiq, “Modelling of stress-corrosion cracking by using peridynamics,” Int J Hydrogen Energy, vol. 41, no. 15, pp. 6593–6609, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Rokkam, M. Gunzburger, M. Brothers, N. Phan, and K. Goel, “A nonlocal peridynamics modeling approach for corrosion damage and crack propagation,” Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, vol. 101, pp. 373–387, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Rokkam, M. Gunzburger, M. Brothers, N. Phan, and K. Goel, “A nonlocal peridynamics modeling approach for corrosion damage and crack propagation,” Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, vol. 101, pp. 373–387, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Chiravarambath, N. K. Simha, R. Namani, and J. L. Lewis, “Poroviscoelastic cartilage properties in the mouse from indentation,” 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Hoang and Y. N. Abousleiman, “Poroviscoelastic two-dimensional anisotropic solution with application to articular cartilage testing,” J Eng Mech, vol. 135, p. 367, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Nia, L. Han, Y. Li, C. Ortiz, and A. Grodzinsky, “Poroelasticity of cartilage at the nanoscale,” Biophys J, vol. 101, no. 9, pp. 2304–2313, 2011. [CrossRef]

- C. W. McCutchen, “Cartilage is poroelastic, not viscoelastic (including and exact theorem about strain energy and viscous loss, and an order of magnitude relation for equilibration time),” J Biomech, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 325–327, 1982. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Kollert et al., “Water and ions binding to extracellular matrix drives stress relaxation, aiding MRI detection of swelling-associated pathology,” Nat Biomed Eng, pp. 1–15, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Xu, and J. Gao, “The engineering and application of extracellular matrix hydrogels: a review,” Biomater Sci, vol. 11, no. 11, pp. 3784–3799, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhou, H. Liu, Z. Zheng, and D. Wu, “Design principles in mechanically adaptable biomaterials for repairing annulus fibrosus rupture: A review,” Bioact Mater, vol. 31, pp. 422–439, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Baar, “Stress relaxation and targeted nutrition to treat patellar tendinopathy,” Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 453–457, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Sheng et al., “Cross-linking manipulation of waterborne biodegradable polyurethane for constructing mechanically adaptable tissue engineering scaffolds,” Regen Biomater, vol. 11, p. rbae111, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Sadati et al., “Smart antimicrobial wound dressings based on mechanically and biologically tuneable hybrid films,” J Mater Chem B, 2026. [CrossRef]

- N. Cohen, “The underlying mechanisms behind the hydration-induced and mechanical response of spider silk,” J Mech Phys Solids, vol. 172, p. 105141, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Cohen, M. Levin, and C. D. Eisenbach, “On the origin of supercontraction in spider silk,” Biomacromolecules, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 993–1000, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Termonia, “Molecular modeling of spider silk elasticity,” Macromolecules, vol. 27, no. 25, pp. 7378–7381, 1994. [CrossRef]

- M. Elices, G. R. Plaza, J. Pérez-Rigueiro, and G. V Guinea, “The hidden link between supercontraction and mechanical behavior of spider silks,” J Mech Behav Biomed Mater, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 658–669, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Jang, Y.-T. Wong, and L. T. J. Korley, “A bio-inspired approach to engineering water-responsive, mechanically-adaptive materials,” Mol Syst Des Eng, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 264–278, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. D. Candia Carnevali, M. Sugni, F. Bonasoro, and I. C. Wilkie, “Mutable collagenous tissue: a concept generator for biomimetic materials and devices,” Mar Drugs, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 37, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Shelton, R. L. Jones, and T. H. Epps III, “Kinetics of domain alignment in block polymer thin films during solvent vapor annealing with soft shear: An in situ small-angle neutron scattering investigation,” Macromolecules, vol. 50, no. 14, pp. 5367–5376, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Luo, D. M. Scott, and T. H. Epps III, “Writing highly ordered macroscopic patterns in cylindrical block polymer thin films via raster solvent vapor annealing and soft shear,” ACS Macro Lett, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 516–520, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Qiang, Y. Zhang, J. A. Groff, K. A. Cavicchi, and B. D. Vogt, “A generalized method for alignment of block copolymer films: solvent vapor annealing with soft shear,” Soft Matter, vol. 10, no. 32, pp. 6068–6076, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Akkineni et al., “Biomimetic Mineral Synthesis by Nanopatterned Supramolecular-Block Copolymer Templates,” Nano Lett, vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 4290–4297, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. dell’Isola and A. Misra, “Principle of virtual work as foundational framework for metamaterial discovery and rational design,” Comptes Rendus. Mécanique, vol. 351, no. S3, pp. 1–25, 2023. [CrossRef]

| Reference | Polymer | Conditions resulting in ESC-like failure | Conditions resulting in ESY/MSCR-like failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ward et al. [68] | Polyethylene | Lower stress, Medium: Igepal | Higher stress, Medium: Igepal |

| Breen [69,70,71,72] | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and chlorinated polyethylene-modified PVC | Medium: n-hexane, n-decane and ethanol vapors | Medium: Benzene and toluene vapor |

| Arnold [73] | thermo-plastic toughened phenolic resin | Medium: Oil | Medium: Water |

| Arnold and colleagues [56] | PMMA | Medium: Methanol (short immersion time) | Medium: Methanol (long immersion time) |

| Arnold and colleagues [56] | PMMA | Water, Ethylene glycol, 355TMH (poor solvent compatibility) | Not observed for these solvents |

| Schilling and colleagues [74] | HDPE | Medium: Arkopal | Medium: Diesel, Biodiesel |

| Hargreaves [10] | PMMA | Medium: Vegetable oil | Medium: ethanol, sodium citrate solution, and hydrochloric acid |

| Al-Saidi [75] | Polycarbonate | Medium: ethylene glycol monomethyl ether (good solvent, surface effects dominate) | Medium: methanol (good solvent, bulk plasticization dominates) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).