Submitted:

29 July 2025

Posted:

30 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2.2. Solution preparations

2.3. Viscosity measurements

2.4. E-beam irradiation

2.5. Intrinsic viscosity and molar mass determinations

2.6. Characterizations

2.6.1. Degradation kinetics

2.6.2. Scaling laws

2.6.3. Chain flexibility

3. Results and discussion

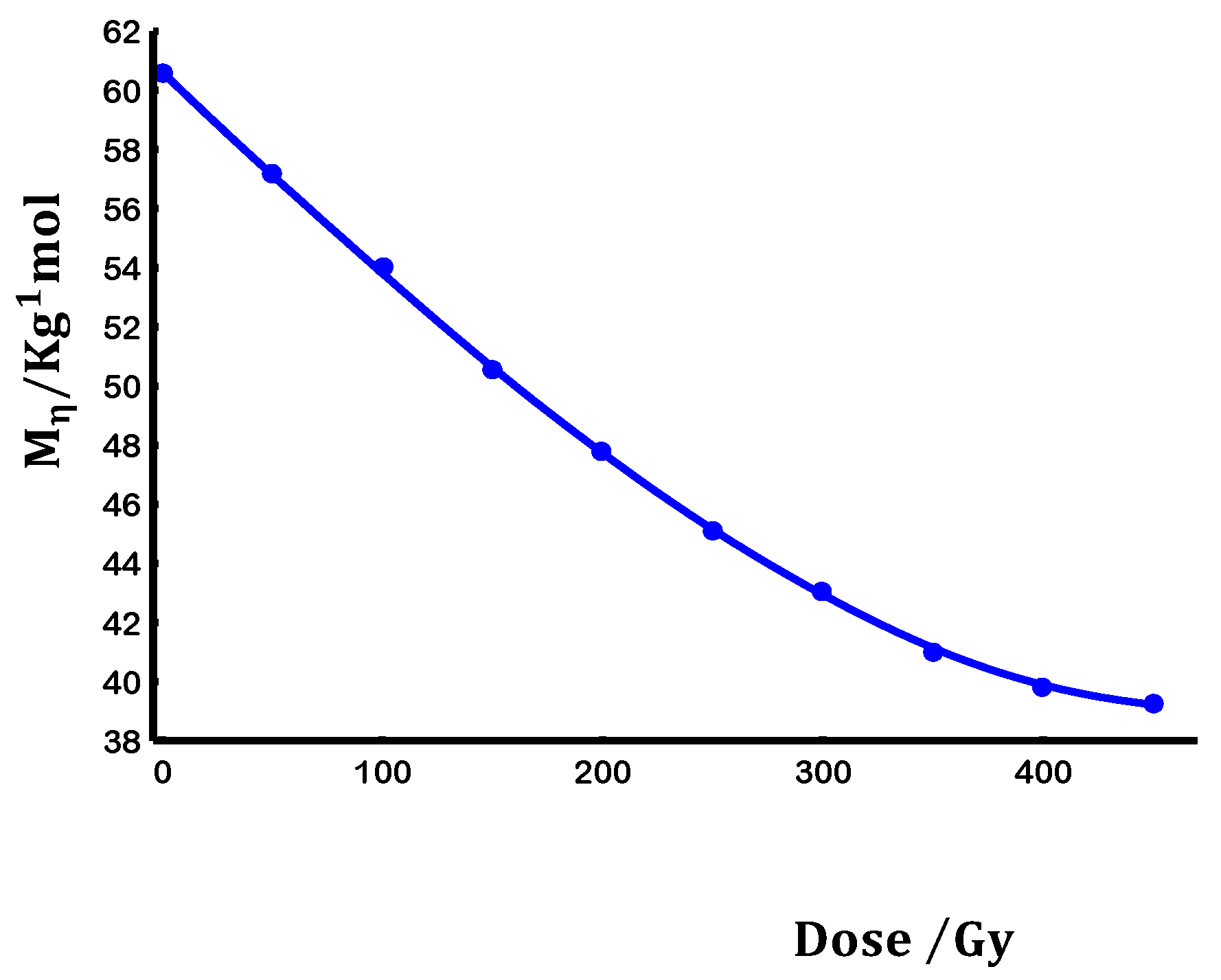

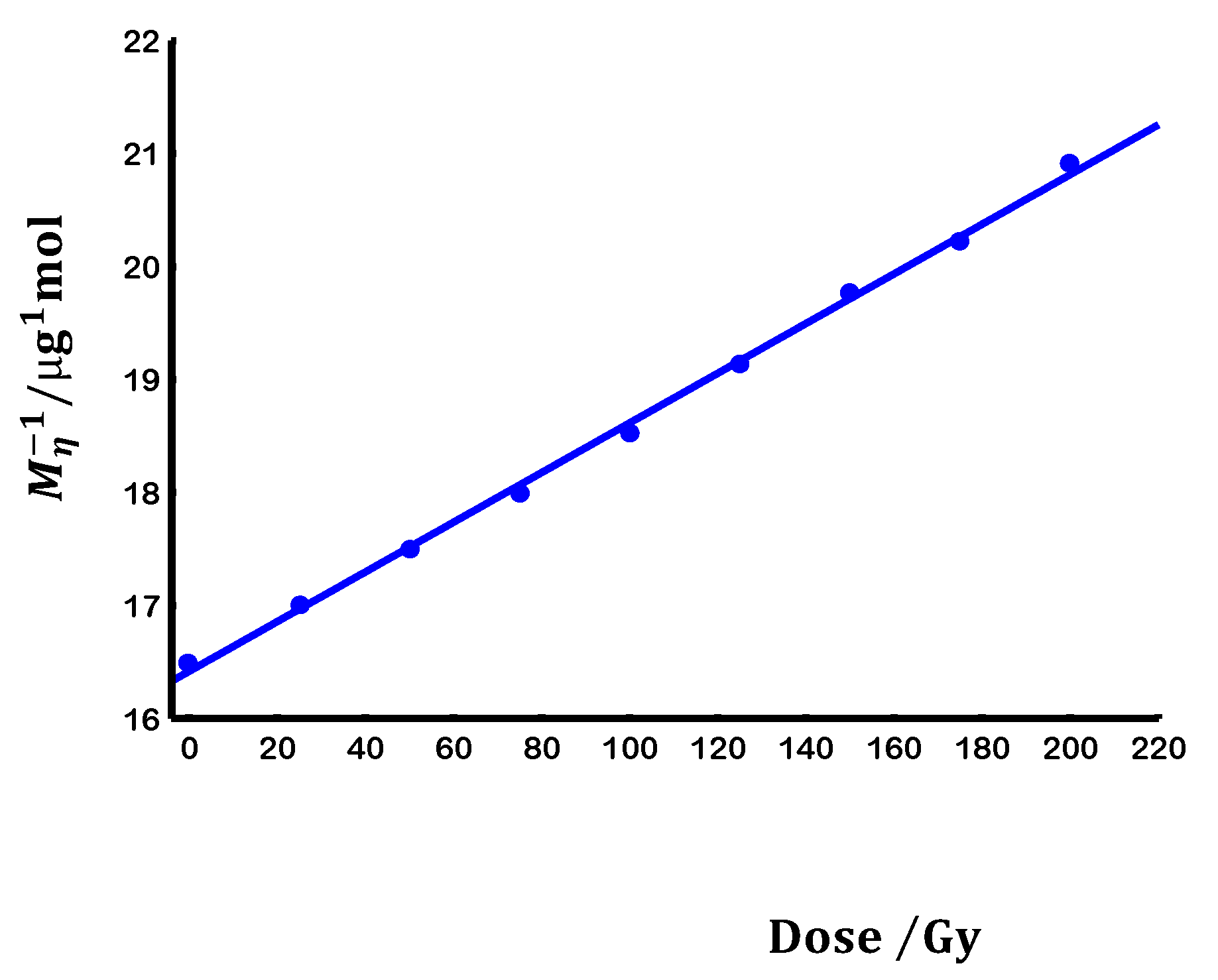

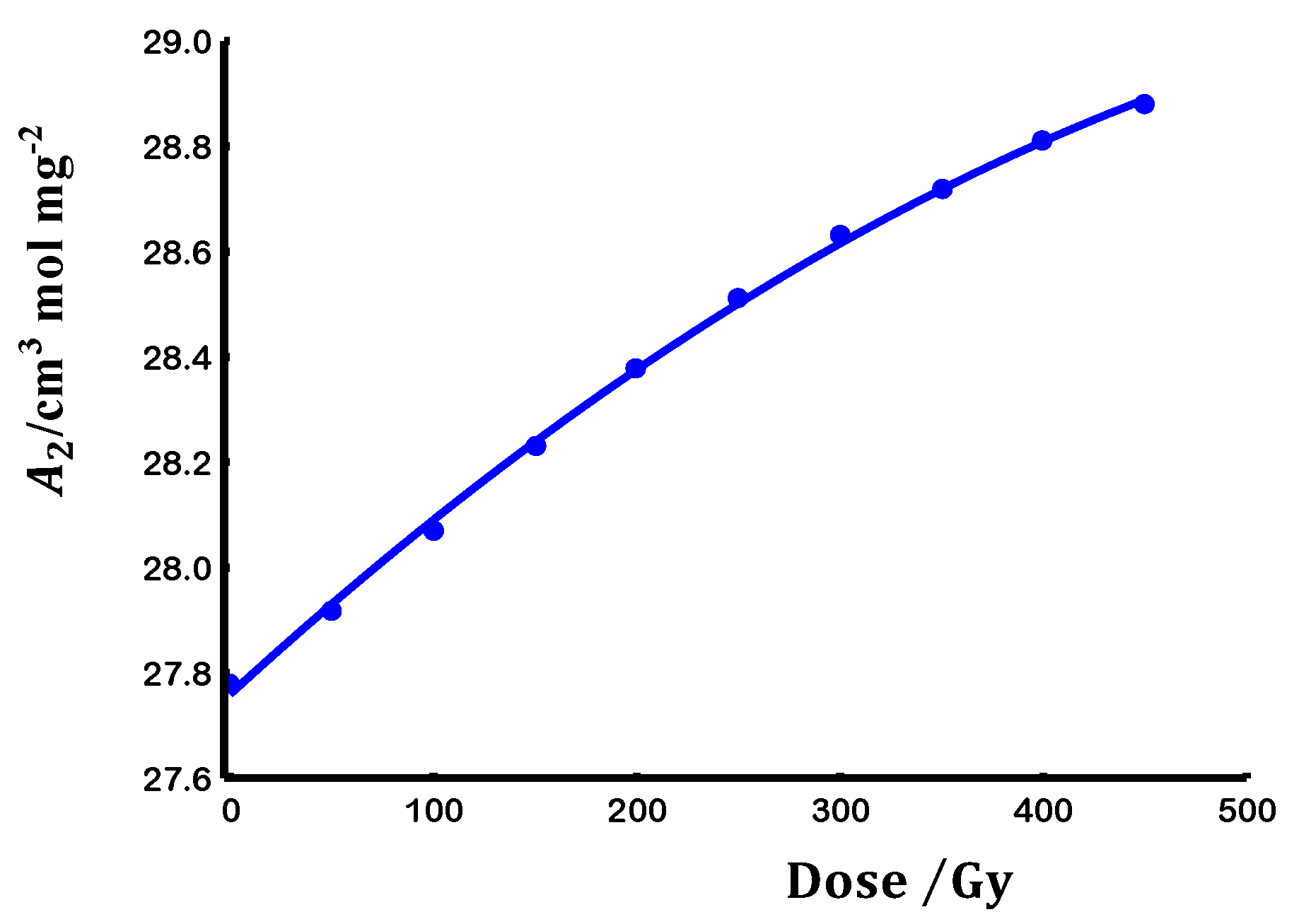

3.1. Degradation kinetics

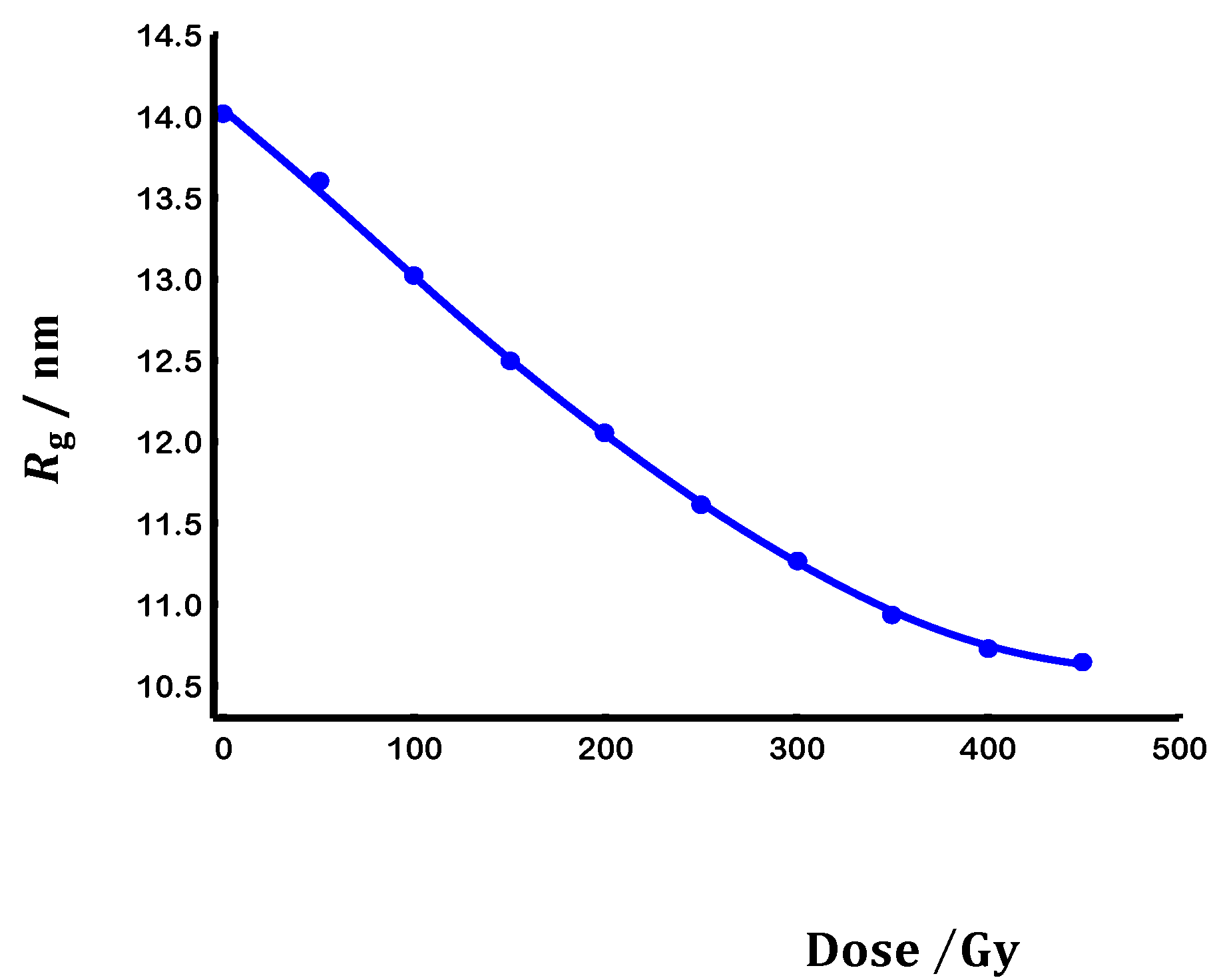

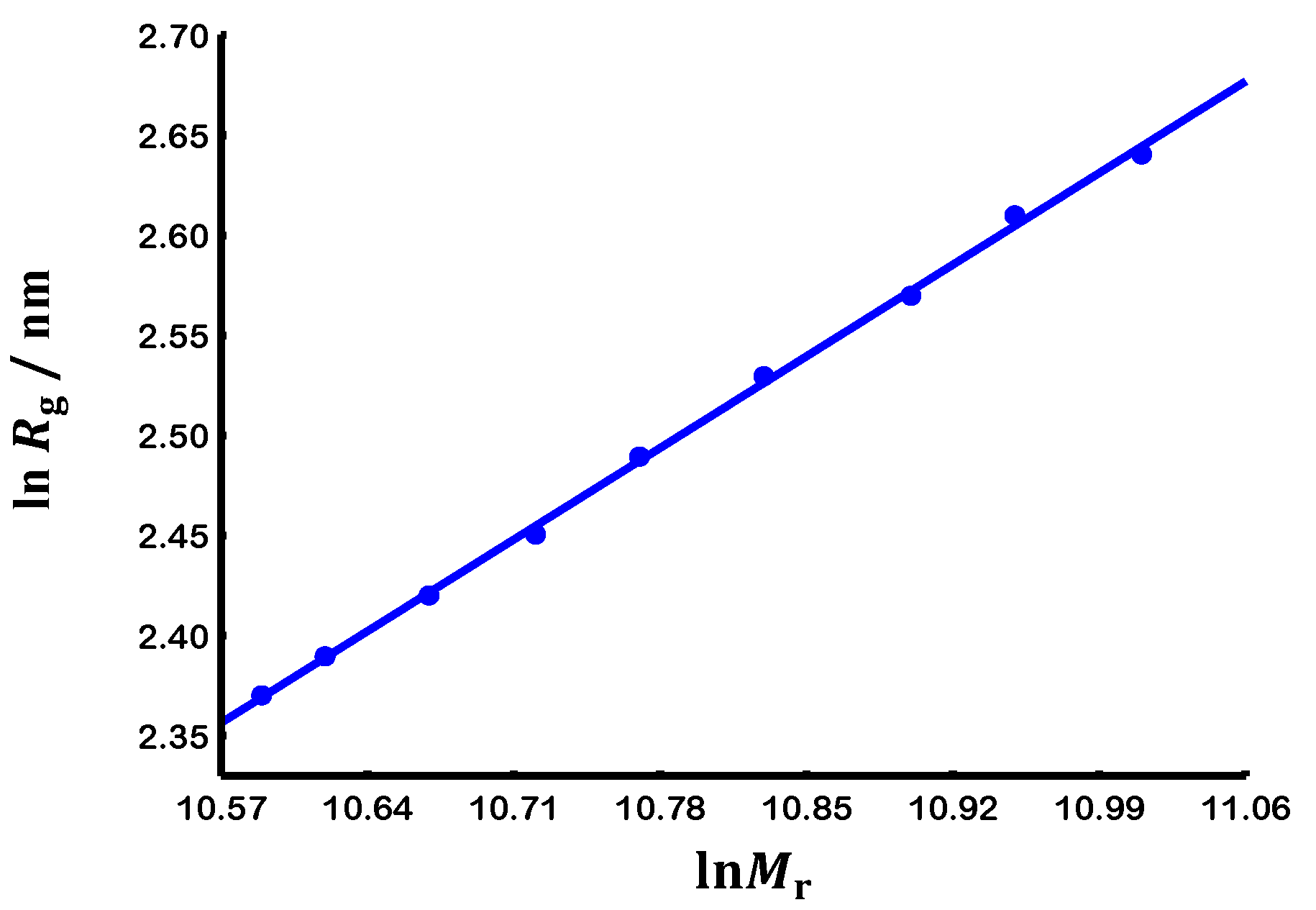

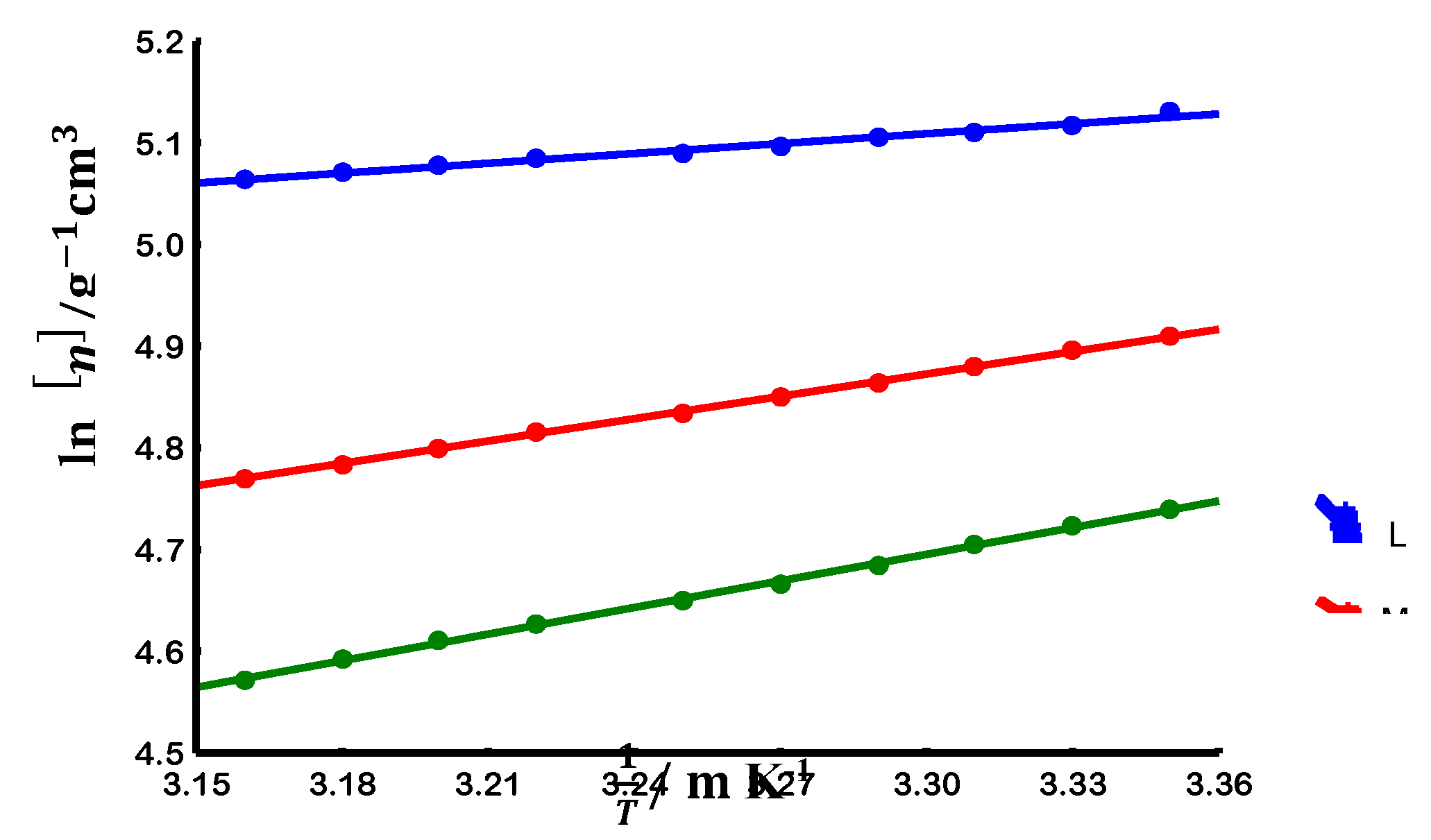

3.2. Scaling laws

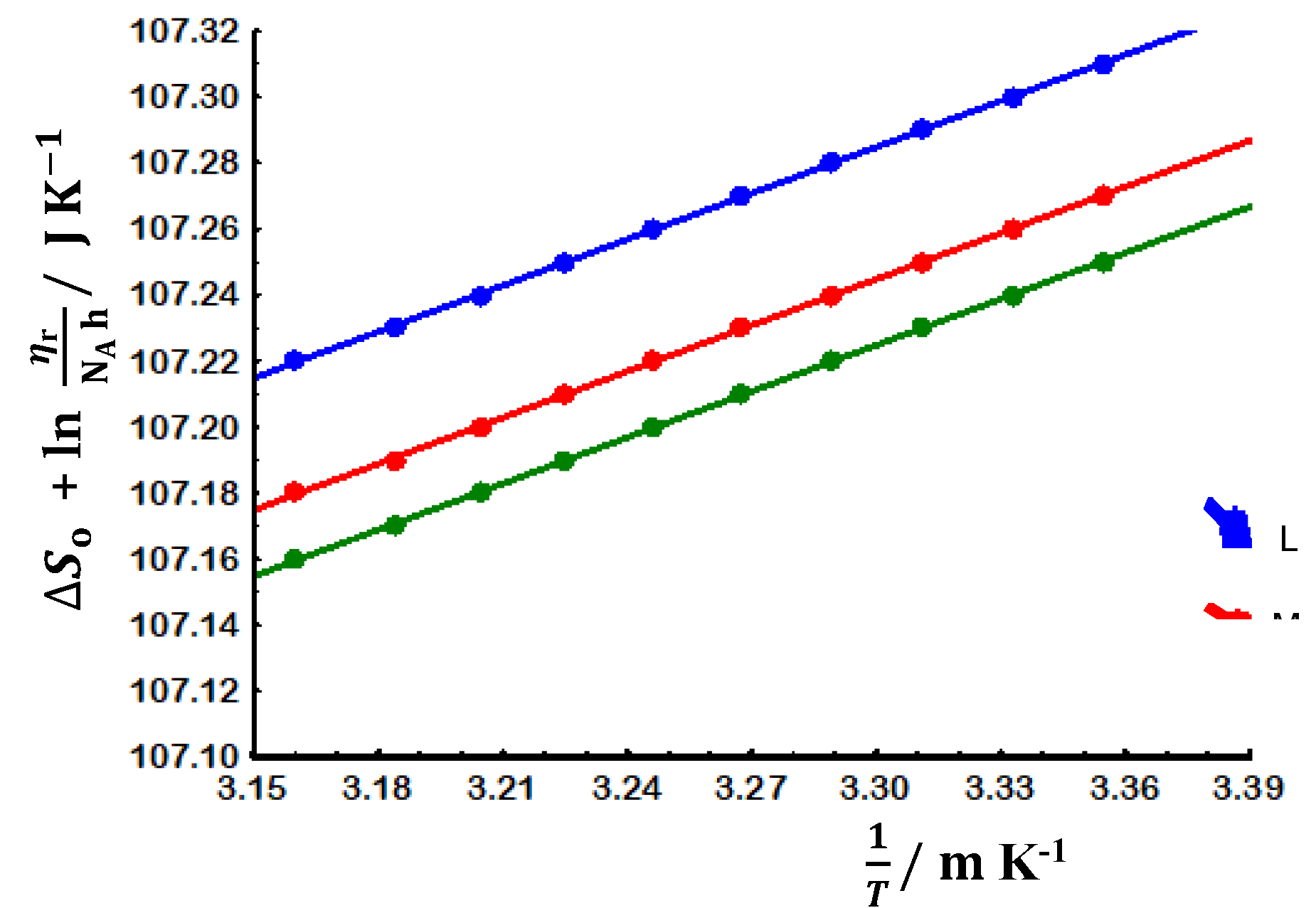

3.3. Chain flexibility

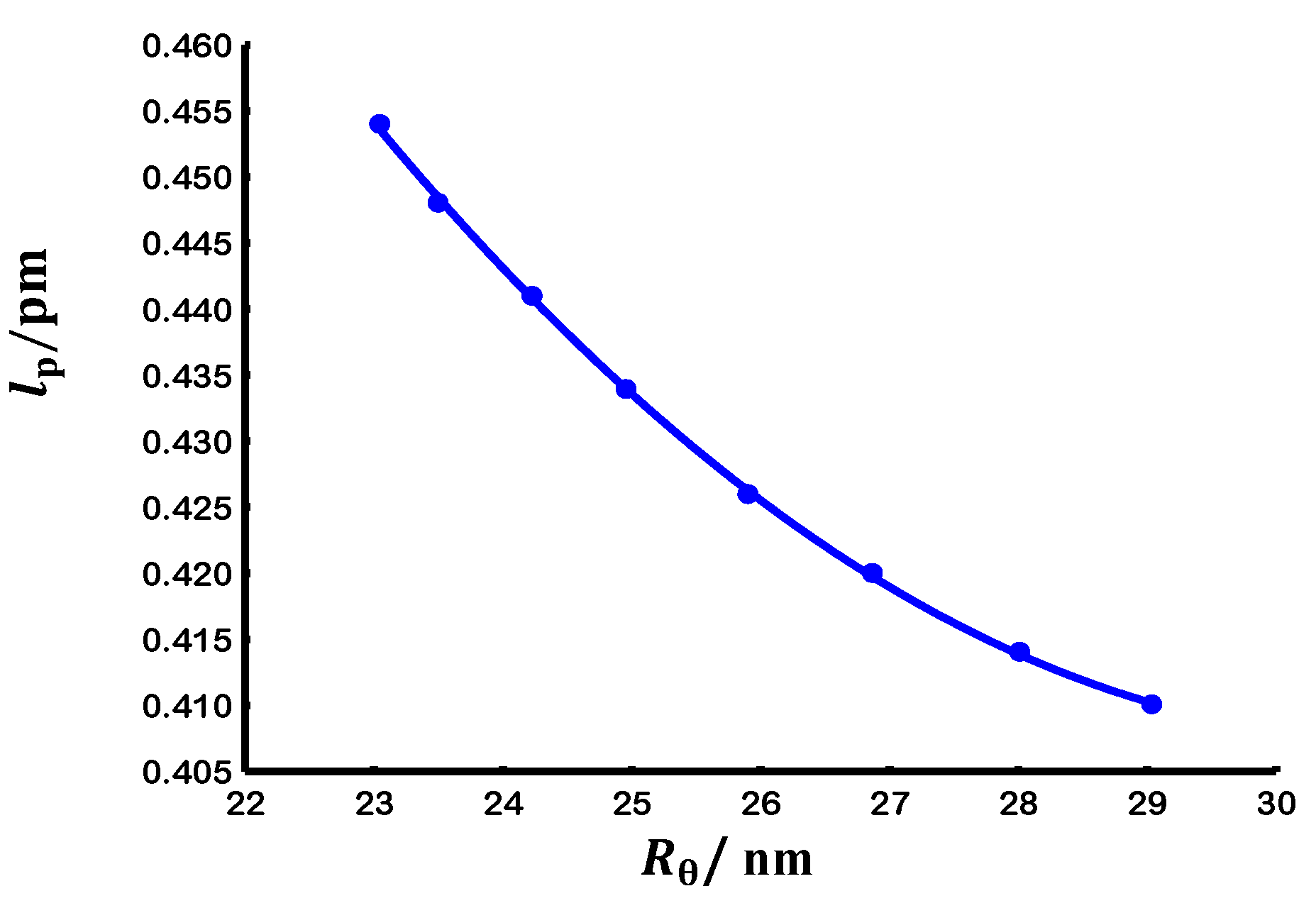

3.3.1. Evaluation at non-theta conditions

3.3.2. Evaluation at theta conditions

4. Concluding remarks

References

- Kulicke WM, Clasen C. Viscosimetry of polymers and polyelectrolytes. Berlin: Springer; 2004.

- W. B. Jensen, “The Origin of the Term Allotrope,” J. Chem. Educ., 2006, 83, 838-839..

- W. Kuhn, Kolloid-Zeitschrift, 1934, 68, 2–15.

- P. J. Flory, Principles of polymer chemistry, Cornell university press, 1953.

- P. J. Flory, Statistical Mechanics of Chain Molecules, Hanser-Gardner, Ohio, 1989.

- Moore WR. Viscosities of dilute polymer solutions. Progress in polymer science. 1967 Jan 1;1:1-43.

- M. Kurata and Y. Tsunashima, in The Wiley Database of Polymer Properties, 1999.

- R. Lapasin, Rheology of industrial polysaccharides: theory and applications, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- Li S, Xiong Q, Lai X, Li X, Wan M, Zhang J, Yan Y, Cao M, Lu L, Guan J, Zhang D. Molecular modification of polysaccharides and resulting bioactivities. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2016 Mar;15(2):237-50.

- Al-Assaf S, Coqueret X, Zaman HM, Sen M, Ulański P, editors. The radiation chemistry of polysaccharides. Vienna, Austria: International Atomic Energy Agency; 2016.

- Hamdani AM, Wani IA, Gani A, Bhat NA, Masoodi FA. Effect of gamma irradiation on physicochemical, structural and rheological properties of plant exudate gums. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2017 Dec 1;44:74-82.

- N. L. del Mastro, in Radiation-Processed Polysaccharides: Emerging Roles in Agriculture, eds. M. Naeem, T. Aftab and M. M. A. Khan, Academic Press, 2022, pp. 91–106.

- Krigbaum WR, Flory PJ. Statistical Mechanics of Dilute Polymer Solutions. IV. Variation of the Osmotic Second Coefficient with Molecular Weight1a, b. Journal of the american chemical society. 1953 Apr;75(8):1775-84.

- Kauzmann W, Eyring H. The viscous flow of large molecules. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1940 Nov;62(11):3113-25.

- Kratky O, Porod G. Röntgenuntersuchung gelöster fadenmoleküle. Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas. 1949;68(12):1106-22.

- Prajapati VD, Jani GK, Zala BS, Khutliwala TA. An insight into the emerging exopolysaccharide gellan gum as a novel polymer. Carbohydrate polymers. 2013 Apr 2;93(2):670-8.

- Lalebeigi F, Alimohamadi A, Afarin S, Aliabadi HA, Mahdavi M, Farahbakhshpour F, Hashemiaval N, Khandani KK, Eivazzadeh-Keihan R, Maleki A. Recent advances on biomedical applications of gellan gum: A review. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2024 Jun 15;334:122008.

- Dreveton E, Monot F, Lecourtier J, Ballerini D, Choplin L. Influence of fermentation hydrodynamics on gellan gum physico-chemical characteristics. Journal of fermentation and bioengineering. 1996 Jan 1;82(3):272-6.

- Kang D, Cai Z, Wei Y, Zhang H. Structure and chain conformation characteristics of high acyl gellan gum polysaccharide in DMSO with sodium nitrate. Polymer. 2017 Oct 16;128:147-58.

- Gao M, Li H, Yang T, Li Z, Hu X, Wang Z, Jiang Y, Zhu L, Zhan X. Production of prebiotic gellan oligosaccharides based on the irradiation treatment and acid hydrolysis of gellan gum. Carbohydrate polymers. 2022 Mar 1;279:119007.

- Solomon OF, Ciutǎ IZ. Détermination de la viscosité intrinsèque de solutions de polymères par une simple détermination de la viscosité. Journal of applied polymer science. 1962 Nov;6(24):683-6.

- Mark H. Über die entstehung und eigenschaften hoch polymer festkörper. In: Sanger R. editor. Der festekörper. Leipzig: Hirzel; 1938. p. 65-104.

- Houwink R. Zusammenhang zwischen viscosimetrisch und osmotisch bestimmten Polymerisationsgraden bei Hochpolymeren. J. Prakt. Chem. 1940;157(1-3):15–18.

- Şen M, Taşkın P, Güven O. Effects of polysaccharide structural parameters on radiation-induced degradation. Hacettepe Journal of Biology and Chemistry. 2014;42(1):9-21.

- Qian JW, Wang ML, Han DL, Cheng RS. A novel method for estimating unperturbed dimension [η] θ of polymer from the measurement of its [η] in a non-theta solvent. European polymer journal. 2001 Jul 1;37(7):1403-7.

- Graessley WW. Polymer chain dimensions and the dependence of viscoelastic properties on concentration, molecular weight and solvent power. Polymer. 1980 Mar 1;21(3):258-62.

| Coefficient | Value |

| a | 0.80 |

| 0.62 | |

| 0.15 |

| M | |||

| L | 2.66 | -879 | 1.19 |

| M | 2.16 | -878 | 1.19 |

| S | 1.74 | -877 | 1.19 |

| M | |||

| L | 30.15 | 5.69 | 0.40 |

| M | 25.91 | 6.08 | 0.43 |

| S | 23.05 | 6.40 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).