Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Feed Resources and Sample Preparation

2.2. Proximate Analysis

2.3. Inoculum Source

2.4. In Vitro Gas Production

2.5. Methane Determinations

2.6. Total Polyphenolic Content

2.7. Antioxidant Activity

2.8. Statistical Analysis

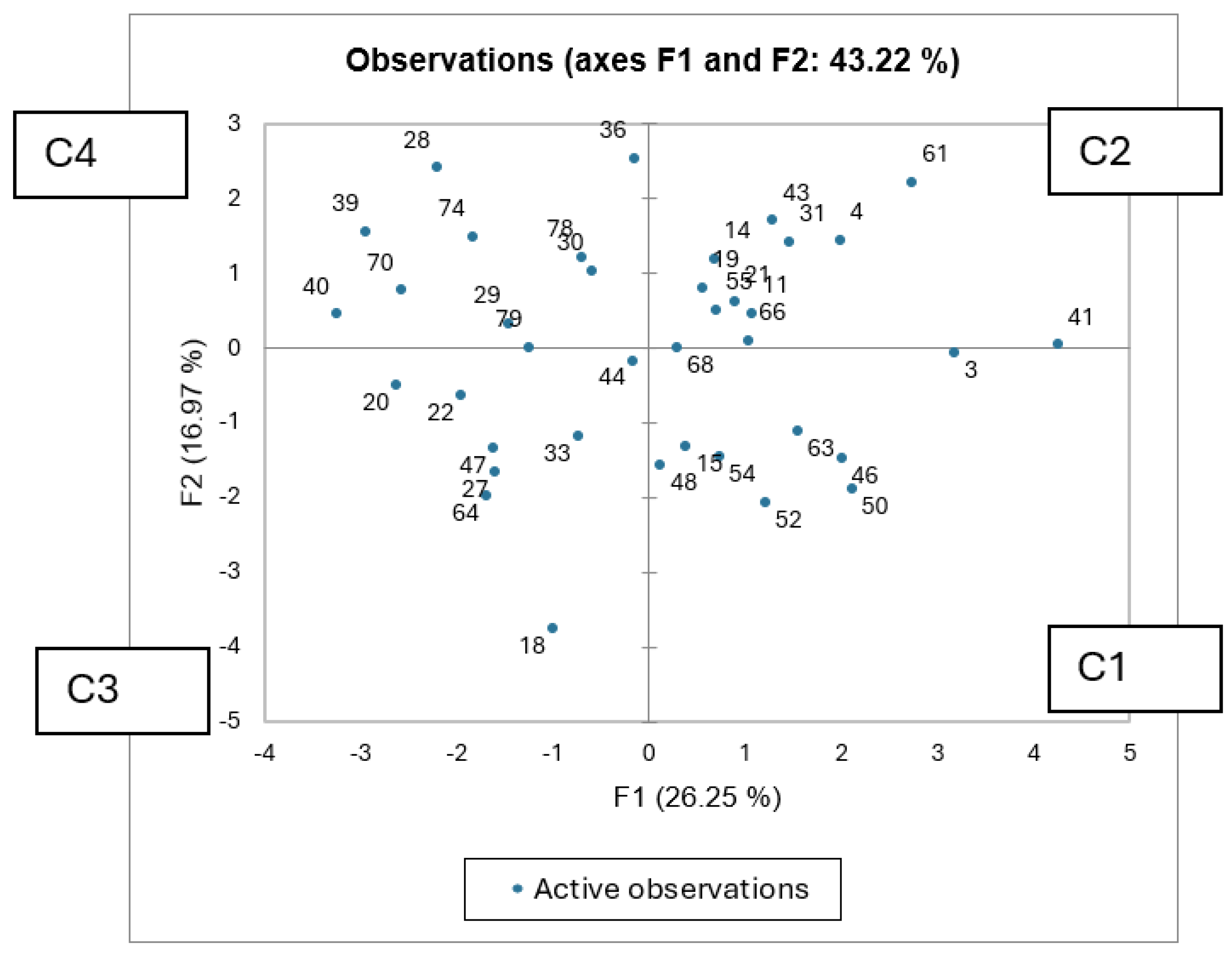

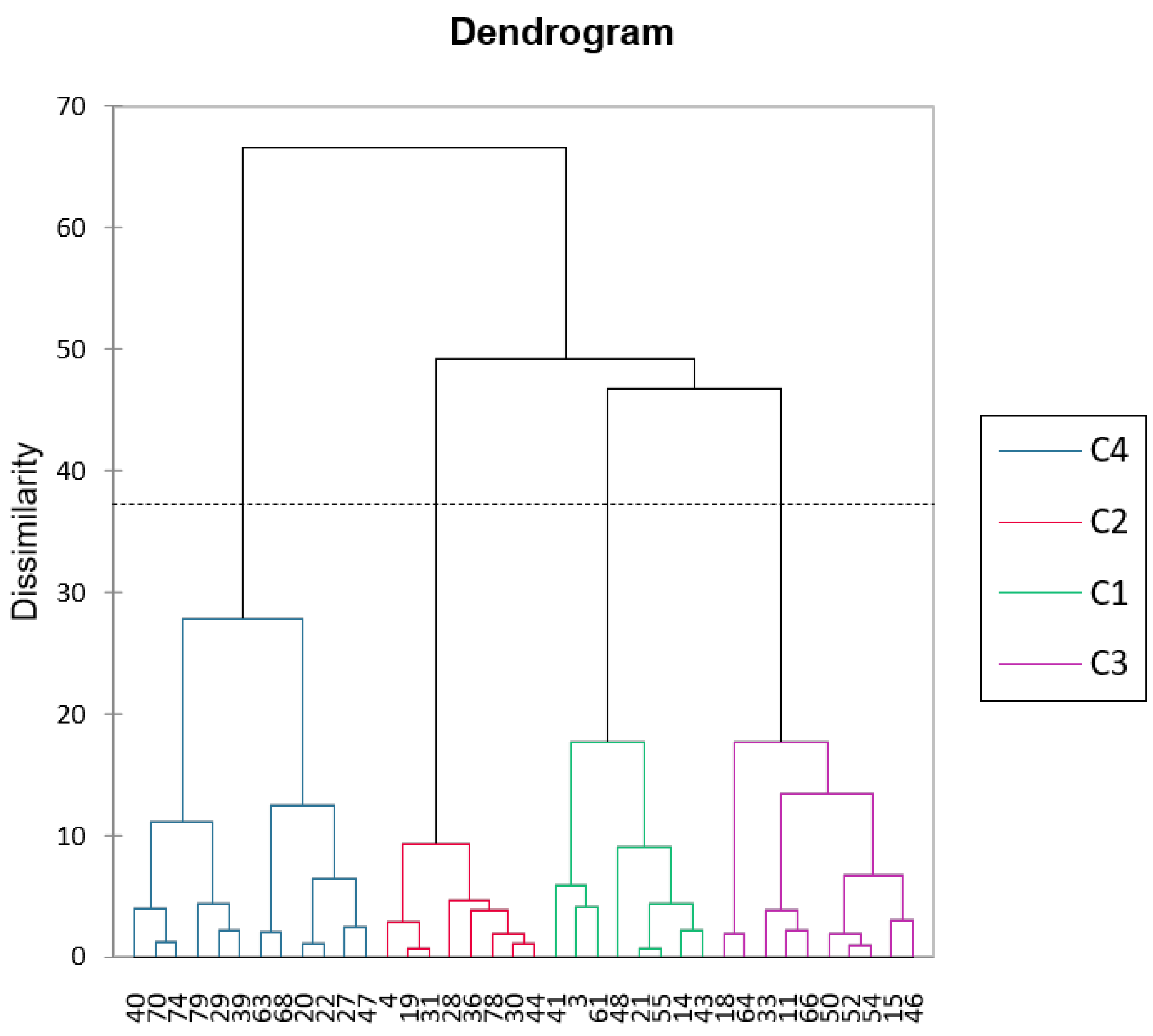

3. Results

3.1. Plant Species Composition Assessment

3.2. Folin Ciocalteu (FC) Results

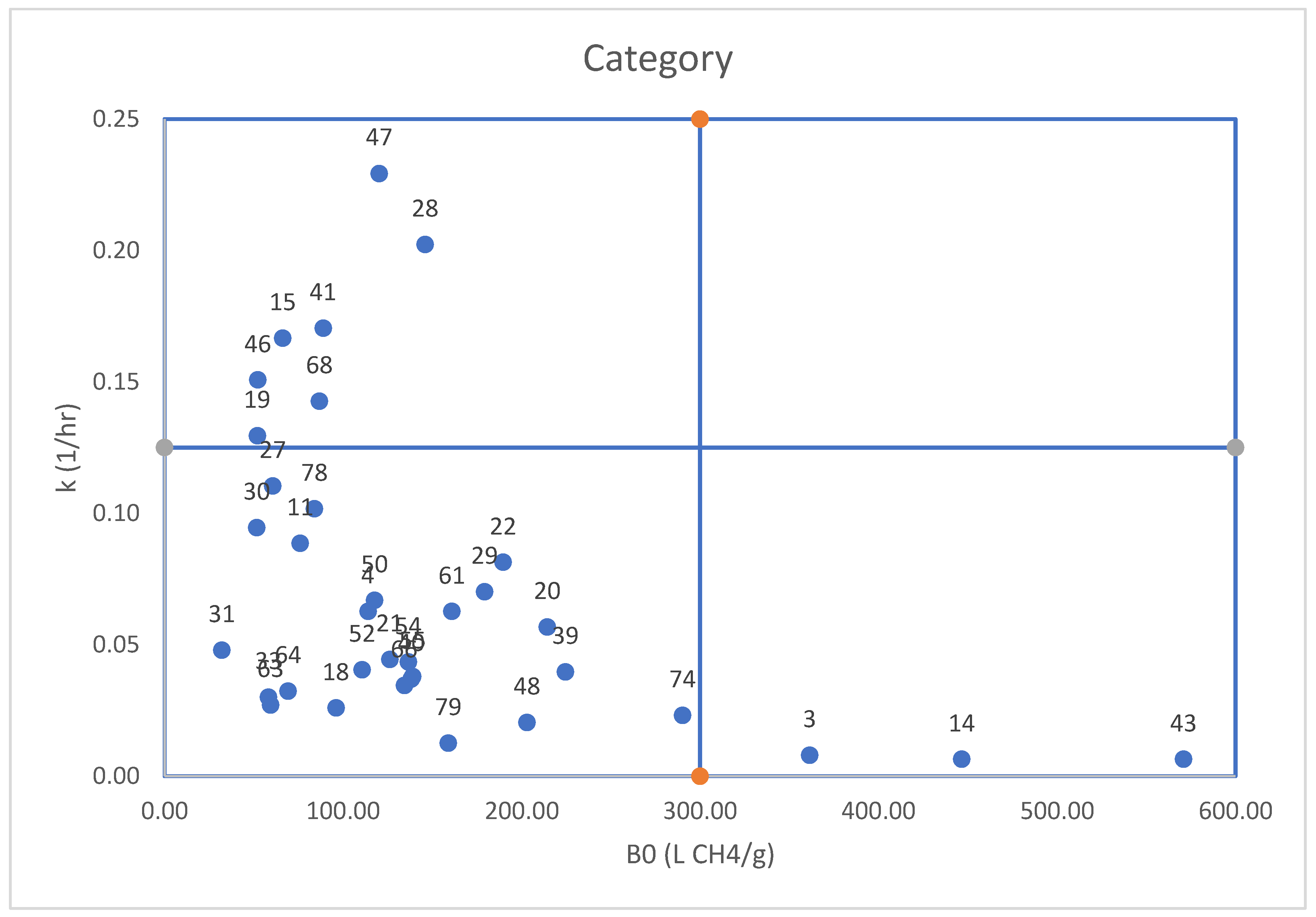

3.3. Methane Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, G.; Jing, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gai, Y.; Tang, W.; Guo, L.; Azzaz, H.H.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Gu, Z.; Mao, S.; Chen, Y. A meta-analysis of dietary inhibitors for reducing methane emissions via modulating rumen microbiota in ruminants. J. Nutr. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumen, A.; Azizi, G.; Chekroun, K.B.; Baghour, M. The effects of livestock methane emission on global warming: A review. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2016, 9, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, P.; Ramilan, T.; Donaghy, D.J.; Pembleton, K.G.; Barber, D.G. Comparison of nutritive values of tropical pasture species grown in different environments and implications for livestock methane production: A meta-analysis. Animals 2022, 12, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gere, J.I.; Restovich, S.B.; Mattera, J.; Cattoni, M.I.; Ortiz-Chura, A.; Posse, G.; Cerón-Cucchi, M.E. Enteric methane emission from cattle grazing systems with cover crops and legume–grass pasture. Animals 2024, 14, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangles, O. Antioxidant activity of plant phenols: Chemical mechanisms and biological significance. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 692–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frond, A.D.; Iuhas, C.I.; Stirbu, I.; Leopold, L.; Socaci, S.; Scurtu, A.; Ayvaz, H.; Mihai, S.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Socaciu, C. Phytochemical characterization of five edible purple-reddish vegetables: Anthocyanins, flavonoids, and phenolic acid derivatives. Molecules 2019, 24, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufarelli, V.; Casalino, E.; D'Alessandro, A.G.; Laudadio, V. Dietary phenolic compounds: Biochemistry, metabolism and significance in animal and human health. Curr. Drug Metab. 2017, 18, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.; Dominguez-López, I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. The chemistry behind the Folin–Ciocalteu method for the estimation of (poly)phenol content in food: Total phenolic intake in a Mediterranean dietary pattern. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 17543–17553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoskina, N.V.; Zubova, M.Y.; Nechaeva, T.L.; Kazantseva, V.V.; Goncharuk, E.A.; Katanskaya, V.M.; Baranova, E.N.; Aksenova, M.A. Polyphenols in plants: Structure, biosynthesis, abiotic stress regulation, and practical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, B.B.; Gruissem, W.; Jones, R.L. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pastorelli, G.; Simeonidis, K.; Faustini, M.; Le Mura, A.; Cavalleri, M.; Serra, V.; Attard, E. Chemical characterization and in vitro gas production kinetics of alternative feed resources for small ruminants in the Maltese Islands. Metabolites 2023, 13, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, E.; Buttigieg, J.; Simeonidis, K.; Pastorelli, G. The modification of dairy cow rations with feed additives mitigates methane production and reduces nitrate content during in vitro ruminal fermentation. Gases 2025, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attard, E. A rapid microtitre plate Folin–Ciocalteu method for the assessment of polyphenols. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2013, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.G. Effect of inoculum/substrate ratio on methane yield and production rate from straw. Biol. Wastes 1989, 28, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, A. Mineral composition and ash content of six major crops. Biomass Bioenergy 2008, 32, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Villalba, J.; Burló, F.; Hernández, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Valorization of wild edible plants as food ingredients and their economic value. Foods 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga, A.; Mainau, E.; González, L.A.; Rodríguez-Prado, M.; Ruíz de la Torre, J.L.; Manteca, X.; Ferret, A. Effect of forage source included in total mixed ration on intake, sorting and feeding behavior of growing heifers fed high-concentrate diets. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 3322–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piątkowska, E.; Biel, W.; Witkowicz, R.; Kępińska-Pacelik, J. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Asteraceae family plants. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.Z.; Islam, M.B.; Jalil, M.A.; Shafique, M.Z. Proximate analysis of Aloe vera leaves. IOSR J. Appl. Chem. 2014, 7, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Berenguer, M.; Salicola, S.A.; Formenti, C.; Giménez, M.J.; Mauromicale, G.; Zapata, P.J.; Lombardo, S.; Pandino, G. Seeds mineral profile and ash content of thirteen different genotypes of cultivated and wild cardoon over three growing seasons. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressurreição, S.; Salgueiro, L.; Figueirinha, A. Diplotaxis genus: A promising source of compounds with nutritional and biological properties. Molecules 2024, 29, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galal, T.M.; Aseeri, S.A.; Soliman, M.A. Nutrients and nutritional value of nine Aloe species grown on the highlands of western Saudi Arabia. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2023, 21, 5481–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheboeuf, D.; Coudert, L.; Bergeault, R.; Lalière, G.; Niderkorn, V. Screening of plants from diversified natural grasslands for their potential to combine high digestibility and low methane and ammonia production. Animal 2014, 8, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzic-Muslic, D.; Petrovic, M.P.; Petrovic, M.M.; Bijelic, Z.; Caro-Petrovic, V.; Maksimovic, N.; Mandic, V. Protein source in diets for ruminant nutrition. Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2014, 30, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Khan, M.Z.; Kou, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, H.; Ullah, Q.; Khan, N.; Khan, A.; Chai, W.; Wang, C. Enhancing metabolism and milk production performance in periparturient dairy cattle through rumen-protected methionine and choline supplementation. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Academies of Sciences; Engineering; and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.A. A global comparison of the nutritive values of forage plants grown in contrasting environments. J. Plant Res. 2018, 131, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveras, I.; Bentley, L.; Fyllas, N.M.; Gvozdevaite, A.; Shenkin, A.F.; Peprah, T.; Morandi, P.; Peixoto, K.S.; Boakye, M.; Adu-Bredu, S.; et al. The influence of taxonomy and environment on leaf trait variation along tropical abiotic gradients. 2020.

- Swart, E.; Brand, T.S.; Engelbrecht, J. The use of near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to predict the chemical composition of feed samples used in ostrich total mixed rations. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 42, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, B.J.; Shurson, G.C. Determination of ether extract digestibility and energy content of specialty lipids with different fatty acid and free fatty acid content, and the effect of lecithin, for nursery pigs. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2017, 33, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Rana, Z.H.; Islam, S.N.; Akhtaruzzaman, M. Comparative assessment of nutritional composition, polyphenol profile, antidiabetic and antioxidative properties of selected edible wild plant species of Bangladesh. Food Chem. 2020, 320, 126646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Giménez-Giménez, A.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Torija-Isasa, M.E. Nutritional composition of Sonchus species (S. asper, S. oleraceus and S. tenerrimus). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 76, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Giller, K.; Kreuzer, M.; Ulbrich, S.E.; Braun, U.; Schwarm, A. Contribution of ruminal fungi, archaea, protozoa, and bacteria to the methane suppression caused by oilseed supplemented diets. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.; Lin, L.; Shih, H.; Shy, Y.; Chang, S.; Lee, T. The potential utilization of high-fiber agricultural by-products as monogastric animal feed and plant species: A review. Animals 2021, 11, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZahal, O.; Or-Rashid, M.M.; Greenwood, S.L.; Douglas, M.S.; McBride, B.W. Effect of dietary fiber level on milk fat concentration and fatty acid profile of cows fed diets containing low levels of polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanchenko, N.; Stefenoni, H.; Hennessy, M.; Nagaraju, I.; Wasson, D.E.; Cueva, S.F.; Räisänen, S.E.; Dechow, C.D.; Pitta, D.W.; Hristov, A.N. Microbial composition, rumen fermentation parameters, enteric methane emissions, and lactational performance of phenotypically high- and low-methane-emitting dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 6146–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, R.; Dong, S.; Mao, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, G. Dietary neutral detergent fiber levels impacting dairy cows’ feeding behavior, rumen fermentation, and production performance during peak lactation. Animals 2023, 13, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziolecka, A.; Osinska, Z.; Sowinski, J.; Kuzdowicz, M. Nitrogen and energy balance in growing cattle. Part 6. Effect of reduced protein content in diets during milk feeding on growth and development of calves. Roczn. Nauk Roln. Ser. B Zootech. 1983, 101, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez, C.V.; Rojas, M.G.V.; Ramírez, C.A.; Chávez-Servín, J.L.; García-Gasca, T.; Ferriz Martínez, R.A.; García, O.P.; Rosado, J.L.; López-Sabater, C.M.; Castellote, A.I.; et al. Total phenolic compounds in milk from different species: Design of an extraction technique for quantification using the Folin–Ciocalteu method. Food Chem. 2015, 176, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, M.; Prathap, P.; Elayadeth-Meethal, M.; Flavel, M.; Eckard, R.; Dunshea, F.R.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Ashar, M.J.; Chen, D.; Chauhan, S. Polyphenol-containing plant species Polygain™ reduces methane production and intensity from grazing dairy cows measured using an inverse method. unpublished. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brinsi, C.; Jedidi, S.; Dhiffalah, A.; Selmi, H.; Sammari, H.; Sebai, H. Nutritional value and phytochemical properties of different parts of dill (Anethum graveolens L.) and their effects on in vitro digestibility in ruminants. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.T.; Li, K.Y.; Tu, P.W.; Ho, S.T.; Hsu, C.C.; Hsieh, J.C.; Chen, M.J. Investigating the reciprocal interrelationships among the ruminal microbiota, metabolome, and mastitis in early lactating Holstein dairy cows. Animals 2021, 11, 3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Terada, F. Factors affecting methane production and mitigation in ruminants. Anim. Sci. J. 2010, 81, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.G. Effect of inoculum/substrate ratio on methane yield and production rate from straw. Biol. Wastes 1989, 28, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Non-conventional fodder resources for feeding livestock. In Recent Approaches in Crop Residue Management and Value Addition for Entrepreneurship Development; ICAR-Indian Grassland and Fodder Research Institute: Jhansi, India, 2016; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

| Number identifier and plant family | Latin Name (Common Name) | DM | ASH | CP | EE | NDF | ADF | NFC | Energy (kcal/100g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Ge | Erodium malacoides (Mallow-Leaved Stork's Bill) | 89.13±3.62 | 11.65±1.28 | 22.4±6.54 | 4.193±1.47 | 22.63±7.55 | 26.2±2.86 | 31.88±0.34 | 369.2±17.05 |

| 4-Bo | Borago officinalis (Common Borage) | 86.68±2.60 | 9.987±0.55 | 20.68±3.63 | 1.52±0.70 | 26.8±2.80 | 21.82±4.52 | 46.01±5.69 | 363.6±4.66 |

| 11-Le | Trifolium nigrescens (Small White Clover) | 89.47±1.85 | 13.83±0.24 | 24.88±3.69 | 0.8767±0.82 | 14.1±10.04 | 25.82±0.77 | 33.72±0.26 | 348.5±5.33 |

| 14-Fa | Scorpiurus muricatus (Many-flowered Scorpiurus) | 88.25±2.32 | 12.76±0.20 | 25.35±4.30 | 1.073±1.41 | 28.83±5.61 | 20.73±1.19 | 35.72±2.15 | 354.3±7.81 |

| 15-Pl | Plantago lagopus (Mediterranean Plantain) | 86.08±4.04 | 12.73±0.63 | 27.98±7.26 | 2.947±0.42 | 38.43±6.71 | 20.58±2.00 | 30.88±0.26 | 347±13.04 |

| 18-Po | Rumex bucephalophorus (Red Dock) | 83.72±1.77 | 17.2±0.37 | 25.3±4.98 | 0.66±0.31 | 33.68±1.92 | 29.8±3.43 | 19.99±3.10 | 326.6±3.74 |

| 19-As | Sonchus oleraceus (Smooth Sow Thistle) | 86.21±1.70 | 13.62±0.87 | 21.09±2.59 | 1.367±1.35 | 26±5.57 | 15.58±4.86 | 30.25±2.42 | 352.4±8.87 |

| 20-As | Calendula arvensis (Field Marigold) | 84.25±1.84 | 15.63±0.37 | 29.86±6.35 | 1.177±1.53 | 26.25±2.34 | 16.81±0.99 | 27.33±0.40 | 343.4±9.11 |

| 21-As | Reichardia picroides (Common Reichardia) | 86.83±1.47 | 13.77±0.05 | 21.63±3.37 | 1.637±0.92 | 18.51±7.76 | 19.47±0.65 | 36.72±0.08 | 353.1±4.50 |

| 22-As | Sonchus asper (Prickly Sow Thistle) | 86.34±3.00 | 16.39±0.80 | 27.81±3.09 | 2.443±0.79 | 24.3±1.70 | 13.47±7.02 | 36.62±5.50 | 337.8±12.38 |

| 27-Ma | Malva sylvestris (Common Mallow) | 87.21±2.46 | 14.68±0.07 | 30±3.37 | 0.85±1.19 | 12.29±4.46 | 19.48±0.50 | 26.44±0.32 | 340.5±6.40 |

| 28-Ra | Nigella damascena (Love-in-a-mist) | 83.85±0.13 | 12.61±1.46 | 28.6±4.23 | 0.6867±1.00 | 23.49±2.56 | 9.18±9.30 | 46.81±8.99 | 348±11.24 |

| 29-Ra | Adonis microcarpa (Pheasant's Eye) | 86.94±2.82 | 13.9±0.25 | 28.96±4.66 | 0.8633±1.25 | 21.87±2.38 | 23.82±1.53 | 33.88±1.02 | 343.3±7.93 |

| 30-Br | Brassica rapa subsp. sylvestris (Wild Turnip) | 83.86±1.05 | 13.89±0.17 | 25.91±2.51 | 1.553±0.81 | 27.72±2.15 | 19±0.99 | 36.78±0.53 | 352.2±4.69 |

| 31-Er | Erica multiflora (Mediterranean Heath) | 86.62±3.00 | 10.36±0.40 | 26.01±6.68 | 2.183±2.83 | 27.3±2.37 | 22.52±0.91 | 33.72±2.13 | 369.5±15.73 |

| 33-Fu | Fumaria capreolata (White Ramping Fumitory) | 86.12±2.79 | 13.65±0.37 | 29.1±5.18 | 0.8667±1.58 | 22.62±7.08 | 23.36±0.81 | 30.75±1.60 | 341.4±9.47 |

| 36-Ir | Gladiolus italicus (Field Gladiolus) | 86.12±2.52 | 12.5±0.66 | 24.94±6.05 | 1.13±1.36 | 44.78±5.03 | 18.46±0.59 | 44.28±4.05 | 351.2±10.45 |

| 39-Xa | Asphodelus fistulosus (Onion Weed) | 85.89±2.09 | 15.66±0.12 | 27.47±4.32 | 0.89±1.20 | 13.62±1.05 | 16.21±1.20 | 45.33±3.84 | 336.6±6.99 |

| 40-Xa | Asphodelus ramosus (Branched Asphodel) | 85.21±2.23 | 15.26±0.23 | 28.43±4.68 | 0.8467±1.34 | 48.89±0.38 | 17.49±0.27 | 43.19±4.27 | 336.4±8.01 |

| 41-As | Galactites tomentosa (Mediterranean Thistle) | 100.9±1.49 | 9.693±1.79 | 1.157±3.01 | 9.457±1.16 | 20.13±2.11 | 31.94±8.32 | 30.81±3.63 | 408.5±12.71 |

| 43-As | Glebionis coronaria (Crown Daisy) | 88±2.67 | 12.56±1.03 | 23.39±5.49 | 4.1±0.29 | 27.23±3.75 | 20.16±0.95 | 41.75±4.30 | 360.6±13.23 |

| 44-La | Teucrium fruticans (Olive-leaved Germander) | 85.61±2.81 | 12.91±0.68 | 26.68±6.67 | 1.17±1.48 | 38.42±6.55 | 23.1±0.62 | 33.57±1.94 | 346.4±11.04 |

| 46-Ap | Foeniculum vulgare (Fennel) | 85.51±1.77 | 12.47±1.17 | 23.02±3.94 | 2.57±0.65 | 24.41±3.31 | 27.32±5.81 | 26.53±5.86 | 347.9±10.37 |

| 47-La | Prasium majus (White Hedge-Nettle) | 85.12±3.32 | 13.93±0.18 | 31.97±4.87 | 2.613±0.51 | 23.66±1.52 | 21.03±2.64 | 31.24±0.56 | 336.5±8.49 |

| 48-So | Solanum nigrum (Black Nightshade) | 88.27±2.49 | 15.78±0.32 | 26.39±4.76 | 3.945±0.55 | 41.6±12.80 | 16.98±2.00 | 31.94±4.04 | 348.1±8.82 |

| 50-As | Pallenis spinosa (Spiny Golden Star) | 91.28±5.11 | 13.88±0.49 | 22.44±7.90 | 1.657±1.70 | 29.04±2.44 | 32.55±9.82 | 21.1±7.34 | 349.4±7.83 |

| 52-Bo | Cynoglossum creticum (Blue Hound's Tongue) | 87.8±2.13 | 13.29±0.59 | 27.62±3.80 | 1.027±1.10 | 24.07±1.53 | 28.8±0.96 | 29.74±0.66 | 348.4±8.85 |

| 54-Ap | Daucus carota (Wild Carrot) | 86.58±2.27 | 13.36±0.42 | 25.69±4.25 | 0.9967±1.13 | 28±7.28 | 27.42±1.74 | 29.42±0.37 | 347.1±8.32 |

| 55-Ac | Acanthus mollis (Bear's Breech) | 88.44±4.90 | 13.71±0.34 | 21.79±10.08 | 1.703±1.90 | 29.08±4.68 | 26.2±6.01 | 36.46±0.29 | 345.3±10.10 |

| 61-Am | Allium subhirsutum (Hairy Garlic) | 91.79±4.84 | 12.21±0.40 | 15.65±9.96 | 3.36±2.78 | 16.65±0.95 | 24.84±5.87 | 46.56±2.11 | 368±12.28 |

| 63-Ur | Urtica pilulifera (Roman Nettle) | 93.03±1.54 | 14.42±0.17 | 29.33±1.95 | 8.05±1.27 | 22.3±5.07 | 25.29±0.51 | 31.54±0.14 | 382.6±6.97 |

| 64-Ur | Parietaria judaica (Pellitory-of-the-wall) | 84.91±0.51 | 15.57±0.26 | 27.47±0.30 | 0.2467±0.22 | 29.17±1.14 | 20.99±0.89 | 34.4±4.89 | 338.9±0.15 |

| 66-As | Centaurea nicaeensis (Mediterranean Star-Thistle) | 86.86±2.04 | 11.75±0.69 | 24.94±4.83 | 0.4467±0.92 | 19.13±1.63 | 21.44±0.14 | 34.65±3.50 | 350.5±7.26 |

| 68-As | Matricaria chamomilla (Scented Mayweed) | 88.49±1.85 | 15.6±0.07 | 27.31±3.13 | 2.427±1.18 | 17.19±2.53 | 20.03±0.75 | 35.54±0.39 | 349.7±6.14 |

| 74-Pl | Bellardia trixago (Mediterranean Lineseed) | 85.8±0.66 | 13.42±0.11 | 27±0.73 | 0.99±1.26 | 17.78±3.91 | 16.18±7.02 | 42.44±3.77 | 339.6±4.95 |

| 78-Pl | Antirrhinum tortuosum (Greater Snapdragon) | 84.83±3.30 | 12.63±0.80 | 25.36±7.68 | 1.02±1.93 | 20.4±1.42 | 23.08±2.24 | 45.58±2.90 | 342.8±12.32 |

| 79-Br | Diplotaxis erucoides (White Wall Rocket) | 89.62±1.88 | 15.67±0.04 | 30.8±2.54 | 1.853±1.02 | 1.853±1.02 | 19.31±0.30 | 31.27±0.19 | 346.6±5.20 |

| Identifier | Latin Name (Common Name) | PolyP (%w/w) | IC50 (mg/ml) |

| 3-Ge | Erodium malacoides (Mallow-Leaved Stork's Bill) | 0.19±0.00 | 1.77±0.52 |

| 4-Bo | Borago officinalis (Common Borage) | 0.26±0.01 | 2.97±0.61 |

| 11-Le | Trifolium nigrescens (Small White Clover) | 0.95±0.06 | 3.07±0.90 |

| 14-Fa | Scorpiurus muricatus (Many-flowered Scorpiurus) | 0.52±0.02 | 3.50±0.87 |

| 15-Pl | Plantago lagopus (Mediterranean Plantain) | 0.17±0.02 | 2.60±0.25 |

| 18-Po | Rumex bucephalophorus (Red Dock) | 0.14±0.02 | 0.37±0.09 |

| 19-As | Sonchus oleraceus (Smooth Sow Thistle) | 0.59±0.06 | 4.40±1.15 |

| 20-As | Calendula arvensis (Field Marigold) | 0.30±0.02 | 22.70±2.17 |

| 21-As | Reichardia picroides (Common Reichardia) | 0.11±0.02 | 5.30±0.32 |

| 22-As | Sonchus asper (Prickly Sow Thistle) | 0.11±0.01 | 10.90±1.29 |

| 27-Ma | Malva sylvestris (Common Mallow) | 0.46±0.01 | 7.23±2.42 |

| 28-Ra | Nigella damascena (Love-in-a-mist) | 0.43±0.02 | 14.40±1.83 |

| 29-Ra | Adonis microcarpa (Pheasant's Eye) | 0.46±0.03 | 5.30±1.21 |

| 30-Br | Brassica rapa subsp. sylvestris (Wild Turnip) | 1.30±0.03 | 6.10±0.96 |

| 31-Er | Erica multiflora (Mediterranean Heath) | 0.50±0.02 | 2.70±1.31 |

| 33-Fu | Fumaria capreolata (White Ramping Fumitory) | 0.68±0.02 | 55.90±5.73 |

| 36-Ir | Gladiolus italicus (Field Gladiolus) | 0.57±0.03 | 11.50±2.33 |

| 39-Xa | Asphodelus fistulosus (Onion Weed) | 0.33±0.05 | 12.50±3.32 |

| 40-Xa | Asphodelus ramosus (Branched Asphodel) | 0.20±0.01 | 3.47±0.53 |

| 41-As | Galactites tomentosa (Mediterranean Thistle) | 0.28±0.02 | 6.50±3.21 |

| 43-As | Glebionis coronaria (Crown Daisy) | 0.46±0.02 | 3.97±0.55 |

| 44-La | Teucrium fruticans (Olive-leaved Germander) | 0.24±0.03 | 0.63±0.09 |

| 46-Ap | Foeniculum vulgare (Fennel) | 0.16±0.01 | 6.50±0.30 |

| 47-La | Prasium majus (White Hedge-Nettle) | 0.07±0.00 | 1.73±0.09 |

| 48-So | Solanum nigrum (Black Nightshade) | 0.18±0.00 | 3.33±0.98 |

| 50-As | Pallenis spinosa (Spiny Golden Star) | 0.13±0.02 | 1.53±0.26 |

| 52-Bo | Cynoglossum creticum (Blue Hound's Tongue) | 0.93±0.02 | 6.17±2.04 |

| 54-Ap | Daucus carota (Wild Carrot) | 0.28±0.01 | 2.13±0.39 |

| 55-Ac | Acanthus mollis (Bear's Breech) | 0.34±0.03 | 9.73±0.29 |

| 61-Am | Allium subhirsutum (Hairy Garlic) | 0.41±0.01 | 3.93±0.73 |

| 63-Ur | Urtica pilulifera (Roman Nettle) | 0.12±0.00 | 5.57±0.43 |

| 64-Ur | Parietaria judaica (Pellitory-of-the-wall) | 0.15±0.04 | 1.17±0.27 |

| 66-As | Centaurea nicaeensis (Mediterranean Star-Thistle) | 0.23±0.03 | 0.43±0.09 |

| 68-As | Matricaria chamomilla (Scented Mayweed) | 0.23±0.01 | 4.30±0.60 |

| 74-Pl | Bellardia trixago (Mediterranean Lineseed) | 0.66±0.04 | 3.77±0.47 |

| 78-Pl | Antirrhinum tortuosum (Greater Snapdragon) | 0.30±0.01 | 9.67±2.46 |

| 79-Br | Diplotaxis erucoides (White Wall Rocket) | 0.37±0.03 | 11.90±0.38 |

| Methane Production (LCH4.kg−1) | |||||

| Additive No | 6h | 24h | 48h | B0 (L CH4/g) | k (1/h) |

| 3 | 22.77±5.55 | 60.37±6.81 | 115.99±6.49 | 361.45 | 0.008 |

| 4 | 13.76±5.27 | 110.42±9.00 | 97.93±12.09 | 114.01 | 0.063 |

| 11 | 38.05±6.05 | 57.38±4.05 | 80.78±4.47 | 76.07 | 0.089 |

| 14 | 14.91±4.28 | 65.25±6.08 | 119.02±22.69 | 446.71 | 0.006 |

| 15 | 37.04±14.49 | 90.47±39.25 | 44.49±9.73 | 66.32 | 0.167 |

| 18 | 9.75±3.92 | 47.01±22.27 | 67.65±24.55 | 96.07 | 0.026 |

| 19 | 25.34±5.80 | 57.22±5.24 | 46.10±8.26 | 51.96 | 0.130 |

| 20 | 22.93±6.04 | 194.82±33.77 | 184.38±4.20 | 214.51 | 0.057 |

| 21 | 16.63±3.60 | 92.65±9.73 | 107.33±27.54 | 126.21 | 0.044 |

| 22 | 68.69±2.89 | 168.79±5.52 | 182.55±5.51 | 189.76 | 0.081 |

| 27 | 32.22±13.05 | 50.57±6.91 | 64.33±25.76 | 60.63 | 0.110 |

| 28 | 105.72±37.86 | 115.01±44.67 | 173.49±47.28 | 146.03 | 0.202 |

| 29 | 35.32±2.89 | 174.87±1.44 | 158.24±27.25 | 179.35 | 0.070 |

| 30 | 22.59±4.21 | 46.10±13.27 | 51.37±14.00 | 51.74 | 0.095 |

| 31 | 12.61±9.53 | 18.23±10.67 | 30.39±14.76 | 32.08 | 0.048 |

| 33 | 12.61±5.81 | 28.09±7.65 | 45.18±7.65 | 58.30 | 0.030 |

| 36 | 38.64±8.38 | 35.78±5.18 | 40.59±2.94 | 38.34 | 10.709 |

| 39 | 35.78±6.18 | 146.54±7.16 | 188.05±2.71 | 224.66 | 0.040 |

| 40 | 56.99±40.31 | 61.00±37.14 | 122.35±2.56 | 138.30 | 0.037 |

| 41 | 57.45±30.23 | 84.51±18.80 | 91.39±13.59 | 88.90 | 0.170 |

| 43 | 37.50±19.37 | 74.07±2.48 | 153.31±29.88 | 570.99 | 0.006 |

| 44 | 72.70±6.09 | 58.02±1.95 | 61.69±4.71 | 64.14 | 5.657 |

| 46 | 29.13±5.57 | 58.82±8.94 | 45.75±5.68 | 52.31 | 0.151 |

| 47 | 89.67±29.91 | 124.30±8.54 | 116.16±7.68 | 120.36 | 0.229 |

| 48 | 7.91±4.16 | 87.61±33.67 | 124.53±23.82 | 203.03 | 0.020 |

| 50 | 30.50±8.37 | 102.97±14.00 | 108.59±7.47 | 117.77 | 0.067 |

| 52 | 31.30±17.02 | 63.41±23.06 | 96.89±32.06 | 110.70 | 0.040 |

| 54 | 5.39±1.29 | 108.02±3.71 | 111.91±6.12 | 136.60 | 0.043 |

| 55 | 48.39±6.39 | 68.91±4.12 | 121.66±3.80 | 139.01 | 0.038 |

| 61 | 78.55±6.03 | 97.58±5.79 | 166.38±45.70 | 160.98 | 0.063 |

| 63 | 12.84±4.60 | 26.03±5.67 | 44.03±10.24 | 59.48 | 0.027 |

| 64 | 10.78±5.13 | 38.30±17.10 | 54.24±13.37 | 69.219 | 0.032 |

| 66 | 26.49±6.12 | 74.76±4.47 | 109.05±7.16 | 134.36 | 0.035 |

| 68 | 33.25±8.10 | 141.38±4.17 | 40.82±6.56 | 86.85 | 0.143 |

| 74 | 57.33±29.29 | 112.37±48.84 | 198.26±21.96 | 290.24 | 0.023 |

| 78 | 28.44±20.84 | 94.26±6.17 | 71.78±12.66 | 83.99 | 0.102 |

| 79 | 20.07±5.45 | 37.15±3.25 | 73.27±15.68 | 159.07 | 0.013 |

| Category | Criteria |

| (1) High B₀ & Low k | High potential yield, slow rate of production |

| (2) High B₀ & High k | High potential yield, fast production rate |

| (3) Moderate B₀ & High k | Moderate yield, fast rate |

| (4) Moderate B₀ & Moderate/Low k | Moderate yield, slow/moderate rate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).