Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

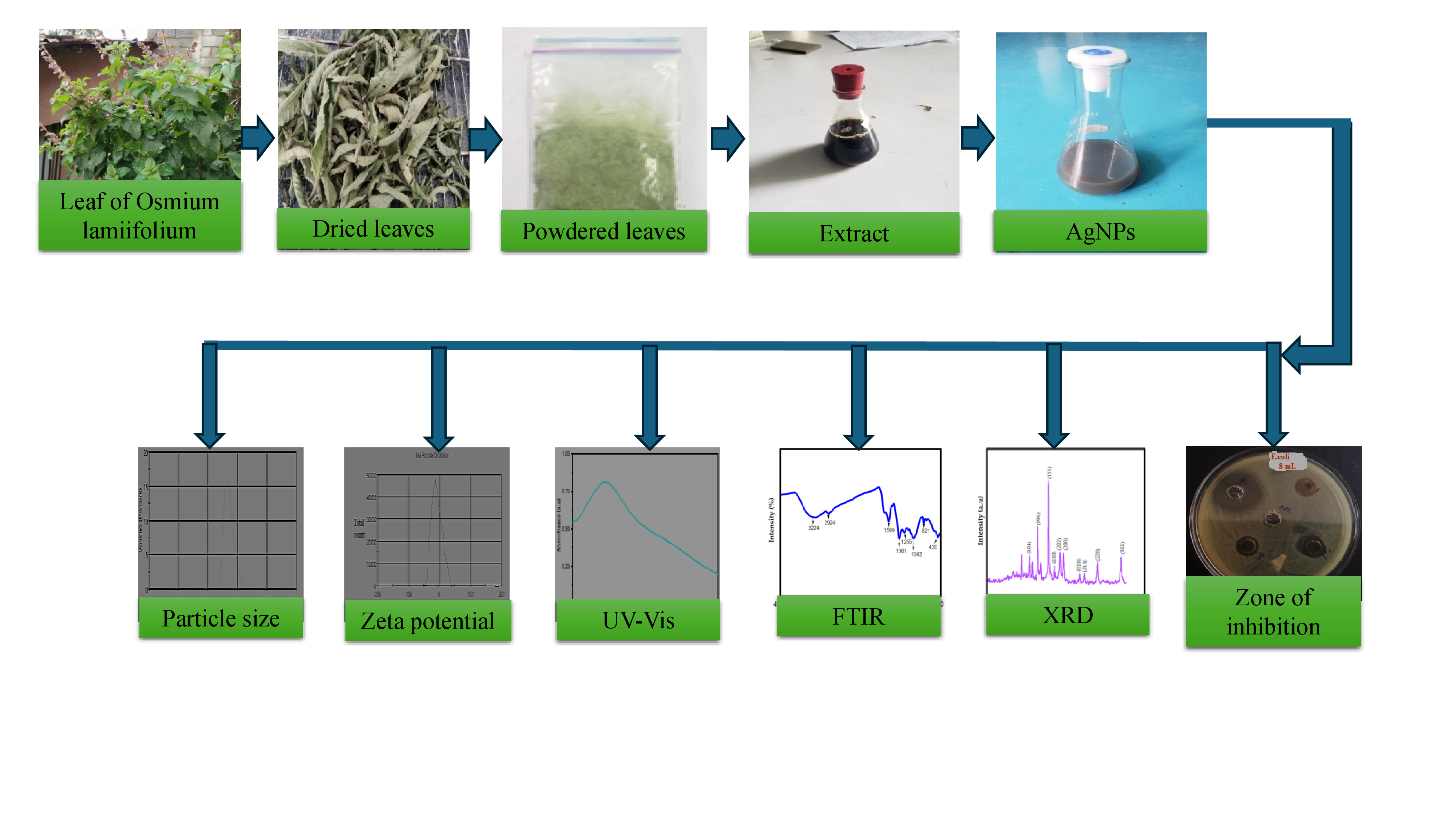

2.2. Synthesis of AgNPs Using Ocimum lamiifolium Extract

2.3. Characterization of Synthesized AgNPs

2.3.1. Droplet Size and Distribution

2.3.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopic Analysis

2.3.3. Zeta Potential

2.3.4. Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy Analysis

2.3.5. X-Ray Diffraction Studies

2.4. Antibacterial Performance Evaluation of AgNPs Mixed with the Leaf Extract

Zone of Inhibition Test for E. coli

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size Distribution Result Analysis Using DLS

3.2. UV-Vis Spectroscopy Analysis

3.3. Zeta Potential

3.4. Fourier Transform Infra-Red Spectroscopy

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy

3.7. Zone of Inhibition Results

3.8. Proposed Mechanisms of AgNPs

4. Conclusions

Data Availability

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

References

- Olaniyan, O.F.; et al. Advances in Green Synthesis and Application of Nanoparticles from Crop Residues: A Comprehensive Review. Scientific African 2025, e02654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokunuzzaman, M.K. The Nanotech Revolution: Advancements in Materials and Medical Science. Journal of Advancements in Material Engineering 2024, 9(2), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, A.; et al. Nanoparticles as drug delivery systems: a review of the implication of nanoparticles’ physicochemical properties on responses in biological systems. Polymers 2023, 15(7), 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.; Meena, A.; et al. Enzymes-based nanomaterial synthesis: an eco-friendly and green synthesis approach. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliraja, T.; et al. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles from ligustrum ovalifolium flower and their catalytic applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15(14), 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, X.; et al. Zingiber officinale polysaccharide silver nanoparticles: a study of its synthesis, structure elucidation, antibacterial and immunomodulatory Activities. Nanomaterials 2025, 15(14), 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malode, S.J.; et al. Bio-based nanomaterials for smart and sustainable nano-biosensing and therapeutics. Industrial Crops and Products 2025, 234, 121603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; et al. Hierarchy of hybrid materials. Part-II: The place of organics-on-inorganics in it, their composition and applications. Frontiers in Chemistry 2023, 11, 1078840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; et al. Organismal Function Enhancement through Biomaterial Intervention. Nanomaterials 2024, 14(4), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, V.; et al. Nanoparticle and nanostructure synthesis and controlled growth methods. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(18), 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, J.; et al. Lead (II)-Azido metal–organic coordination polymers: synthesis, structure and application in PbO nanomaterials preparation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(13), 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, M.; et al. Chromogenic chemodosimeter based on capped silica particles to detect spermine and spermidine. Nanomaterials 2021, 11(3), 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagime, P.V.; et al. Metallic nanostructures: an updated review on synthesis, stability, safety, and applications with tremendous multifunctional opportunities. Pharmaceutical Nanotechnology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, F.; et al. A comprehensive review of nanoparticles: from classification to application and toxicity. Molecules 2024, 29(15), 3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jangid, H.; et al. Advancing biomedical applications: an in-depth analysis of silver nanoparticles in antimicrobial, anticancer, and wound healing roles. Frontiers in pharmacology 2024, 15, 1438227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sati, A.; et al. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs): comprehensive insights into bio/synthesis, key influencing factors, multifaceted applications, and toxicity─ a 2024 update. ACS omega 2025, 10(8), 7549–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, P.J.; et al. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles immobilized on activated carbon nanoparticles: antibacterial activity enhancement study and its application on textiles fabrics. Molecules 2021, 26(13), 3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budama, L.; et al. A new strategy for producing antibacterial textile surfaces using silver nanoparticles. Chemical engineering journal 2013, 228, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, A.; et al. A review on biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their potential applications. Results in Chemistry 2023, 6, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasmi, F.; et al. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Methods of Synthesis, Characterization, and Their Application: A Review. Plasmonics 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.; Gonfa, G.; Hailegiorgis, S.M. Synthesis of modified silica gel supported silver nanoparticles for the application of drinking water disinfection: a review. Results in Engineering 2024, 22, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, A.H.; Toha, M.; Tareq, S.M. Occupational chemical safety and management: A case study to identify best practices for sustainable advancement of Bangladesh. Hygiene and Environmental Health Advances 2024, 12, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.; et al. A review on silver nanoparticles: Classification, various methods of synthesis, and their potential roles in biomedical applications and water treatment. Water 2021, 13(16), 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noga, M.; et al. Toxicological aspects, safety assessment, and green toxicology of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)—critical review: state of the art. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(6), 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using reducing agents of bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) extract and tri-sodium citrate. Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects 2023, 35, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmitwalli, O.S.M.M.S.; et al. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using cinnamomum-based extracts and their applications. Nanotechnology, Science and Applications 2025, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocso, N.-S.; Butnariu, M. The biological role of primary and secondary plants metabolites. Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing 2022, 5(3), 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, K.K.; et al. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using plant extracts as beneficial prospect for cancer theranostics. Molecules 2021, 26(21), 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, G.; et al. Isolation of ursolic acid from the leaves of Ocimum lamiifolium collected from Addis Ababa Area, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Biotechnol 2020, 19, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sahalie, N.A.; Abrha, L.H.; Tolesa, L.D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of leave extract of Ocimum lamiifolium (Damakese) as a treatment for urinary tract infection. Cogent Chemistry 2018, 4(1), 1440894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), structural characterization, and their antibacterial potential. Dose-response 2022, 20(2), 15593258221088709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh-Taheri, R.; et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Salvadora persica and Caccinia macranthera extracts: cytotoxicity analysis and antimicrobial activity against antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2023, 195(8), 5120–5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, A.S.; Raisi, A.; Aroujalian, A.; et al. Control size and stability of colloidal silver nanoparticles with antibacterial activity prepared by a green synthesis method. Synthesis and reactivity in inorganic, Metal-organic, and Nano-metal chemistry 2013, 43(5), 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibici, D.; Kahveci, D. Effect of emulsifier type, maltodextrin, and β-cyclodextrin on physical and oxidative stability of oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of Food Science 2019, 84(6), 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, M. Detection and enumeration of Bacteria, yeast, viruses, and protozoan in foods and freshwater; Springer Nature, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, R.; et al. Overview of changes to the clinical and laboratory standards institute performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100. Journal of clinical microbiology 2021, 59(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinvula, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Moringa oleifera extracts and their evaluation against antibiotic resistant strains of escherichia coli and staphylococcus aureus; University of Namibia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nikam, S.P.; et al. Antibiotic eluting poly (ester urea) films for control of a model cardiac implantable electronic device infection. Acta Biomaterialia 2020, 111, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gildas, F.N.; et al. Phytoassisted synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles using Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract: characterization, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and acute toxicity profile. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.10. 31.621348. [Google Scholar]

- Krkobabić, A.; et al. Plant-assisted synthesis of Ag-based nanoparticles on cotton: Antimicrobial and cytotoxicity studies. Molecules 2024, 29(7), 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khiavi, H.D.; et al. The application of nanostructured lipid carrier for encapsulation of Rosa canina and Heracleum persicum extracts and production of mayonnaise enriched with encapsulated extracts. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2025, 19, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Pandey, A. Formulation development and optimization of nanoemulsion gel containing Prosopis cineraria, Aerva javanica, and Fagonia indica extracts for treatment of arthritis. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2025, 16(1), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G.; Singh, M.; et al. Characterization of silver nano-particles synthesized using fenugreek leave extract and its antibacterial activity. Materials Science for Energy Technologies 2022, 5, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, G.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles prepared with carrasquilla fruit extract (Berberis hallii) and evaluation of its photocatalytic activity. Catalysts 2021, 11(10), 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, Z.; et al. Plant-based synthesis of Ag-doped ZnO/MgO nanocomposites using Caccinia macranthera extract and evaluation of their photocatalytic activity, cytotoxicity, and potential application as a novel sensor for detection of Pb2+ ions. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airemwen, C.; Obarisiagbon, A. Formulation of silver nanoparticles from the leaves extract of Vernonia amygdalina. The Nig J. Pharm 2023, 57(1), 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, N.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Cynodon dactylon leaves and assessment of their antibacterial activity. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2013, 36, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aziz, M.S.; et al. Antioxidant and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles biosynthesized using Chenopodium murale leaf extract. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2014, 18(4), 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; et al. Cynodon dactylon leaf extract assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their anti-microbial activity. Advanced Science, Engineering and Medicine 2013, 5(8), 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, A.; et al. Biogenic Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Bitter Leaf (Vernonia amygdalina) Aqueous Extract and Its Effects on Testosterone-Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH) in Wistar Rat. Chemistry Africa 2021, 4(4), 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzekekwu, A.; Abosede, O. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using leaves extracts of neem (Azadirachta indica) and bitter leaf (Vernonia amygdalina). Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2019, 23(4), 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALAMPALLY, B.B.; et al. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Azadirachta Indica (Neem) Fruit Pulp Extract and Their Antioxidant, Antibacterial, and Anticancer Activity. [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, T.; Ravikumar, C.; Murthy, H.A. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanostructures using medicinal plant Vernonia amygdalina Del. leaf extract for multifunctional applications. Applied Nanoscience 2021, 11(2), 535–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivalingam, A.M.; Pandian, A.; Rengarajan, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract: characterization, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties. Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials 2024, 34(7), 3212–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, O.; et al. Phenolic compound explorer: A mid-infrared spectroscopy database. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2017, 92, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Cichy, M.; Flieger, J. Application of Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy in characterization of green synthesized nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30(3), 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arokiyaraj, S.; et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Rheum palmatum root extract and their antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology 2017, 45(2), 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, K.; Baunthiyal, M.; Singh, A. Characterization of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Urtica dioica Linn. leaves and their synergistic effects with antibiotics. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2016, 9(3), 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romei, M.G.; et al. Frequency changes in terminal alkynes provide strong, sensitive, and solvatochromic Raman probes of biochemical environments. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2022, 127(1), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaonkar, D.; Rai, M.; et al. Sequentially reduced biogenic silver-gold nanoparticles with enhanced antimicrobial potential over silver and gold monometallic nanoparticles. Advanced Materials Letters 2015, 6(4), 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, S.; et al. Synthesis of silver nanostructures of varying morphologies through seed mediated growth approach. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2010, 153(2-3), 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; et al. Novel synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from leaf aqueous extract of Aloe vera and their anti-microbial activity. J Nanosci Nano-Technol 2017, 1, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Tailor, G.; et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum canum and their anti-bacterial activity. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2020, 24, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerragopu, P.S.; et al. Chemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles using tri-sodium citrate, stability study and their characterization. International Research Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry 2020, 21(3), 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavizadeh Yazdi, M.E.; et al. Anticancer, antimicrobial, and dye degradation activity of biosynthesised silver nanoparticle using Artemisia kopetdaghensis. Micro & Nano Letters 2020, 15(14), 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabouri, Z.; et al. Facile green synthesis of Ag-doped ZnO/CaO nanocomposites with Caccinia macranthera seed extract and assessment of their cytotoxicity, antibacterial, and photocatalytic activity. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering 2022, 45(11), 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, N.K.; et al. Green-based synthesis of mixed-phase silver nanoparticles as an effective photocatalyst and investigation of their antibacterial properties. Journal of Molecular Structure 2020, 1203, 127411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, I.; et al. Antimicrobial coating of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles on surgical fabric and surgical blade to prevent nosocomial infections. Heliyon 2024, 10(17). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlous, K.A.; et al. Eco-friendly method for silver nanoparticles immobilized decorated silica: synthesis & characterization and preliminary antibacterial activity. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2019, 95, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; et al. A Facile plant mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an aqueous leaf extract of Ficus hispida Linn. f. for catalytic, antioxidant and antibacterial applications. South African journal of chemical engineering 2018, 26, 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.M.; et al. Reactive oxygen species induced oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins of antibiotic-resistant bacteria by plant-based silver nanoparticles. 3 Biotech 2023, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reducing agents | Methods | Average particle size (nm) | UV-vis analysis | Energy gap (eV) | References |

| Ocimum lamiifolium leaves extract | Green |

65.37 | 467 |

5.344 | Current research work |

| Vernonia amygdalina leaves extract | Green | 63.08 | 452 | 5.234 | [25] |

| Vernonia amygdalina leaves extract | Green | 70-90 | 480 | - | [46] |

| Chenopodium murale leaf | Green | 30-50 | 440 | - | [48] |

| Caccinia macranthera seed extract | Green | 37-89 | 663 | 3.1 | [45] |

| Cynodon dactylon grass leaf extract | Green | 78.66 | 417 | [49] | |

| Vernonia amygdalina leaves extract | Green | 34 | 450 | - | [50] |

| Cynodon dactylon leaves | Green | 8-10 | 451 | - | [47] |

| Azadirachta indica leaves extract | Green | - | 455 | [51] | |

| Azadirachta indica fruit pulp extract | Green | 36.8 | 400–475 | - | [52] |

| Plant source | Tested pathogen | Zone of inhibition (mm) | References |

| Ocimum lamiifolium leaves extract | E. coli | 15.45 | Current research work |

| Azadirachta indica fruit pulp extract | E. coli | 15 | [52] |

| S. aureus | 16 | ||

| Streptococcus | 16 | ||

| Cynodon dactylon grass leaf extrac | E. coli | 12 | [49] |

| Vernonia amygdalina leaves extract | S. aureus | 8.46-9.85 | [46] |

| Leaf extract of Ficus hispida Linn.f | E. coli | 14 | [70] |

| Bacillus subtilis | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).