1. Introduction

The imbalance between antioxidant activity and the increase of reactive oxygen species is associated with various human diseases, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer [

1,

2,

3]. Among the main antioxidant enzymes is catalase (CAT), which plays a central role in decomposing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), preventing cellular oxidative damage. CAT is in peroxisomes and is one of the most efficient known enzymes, as it can convert millions of H₂O₂ molecules per second [

4,

5].

Given its important protective activity, changes in its expression or function can alter cellular homeostasis and promote certain abnormal processes such as chronic inflammation, deregulated cell proliferation, and treatment resistance [

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, in cancer, CAT appears to have a complex role, acting as a protective antioxidant in some situations and as a driver of tumor aggressiveness or treatment resistance in others [

6,

7].

Despite the recognition of CAT's functional importance, little is still known about the specific impact that mutations may have on its enzymatic activity, especially those of uncertain clinical significance [

9,

10]. Some variants have been reported in genomic databases, but their functional consequences remain unclear. Understanding how mutations in CAT alter its activity could provide new insights into the pathophysiology of oxidative stress-related diseases such as cancer and potentially identify biomarkers or personalized therapeutic strategies [

7,

11,

12].

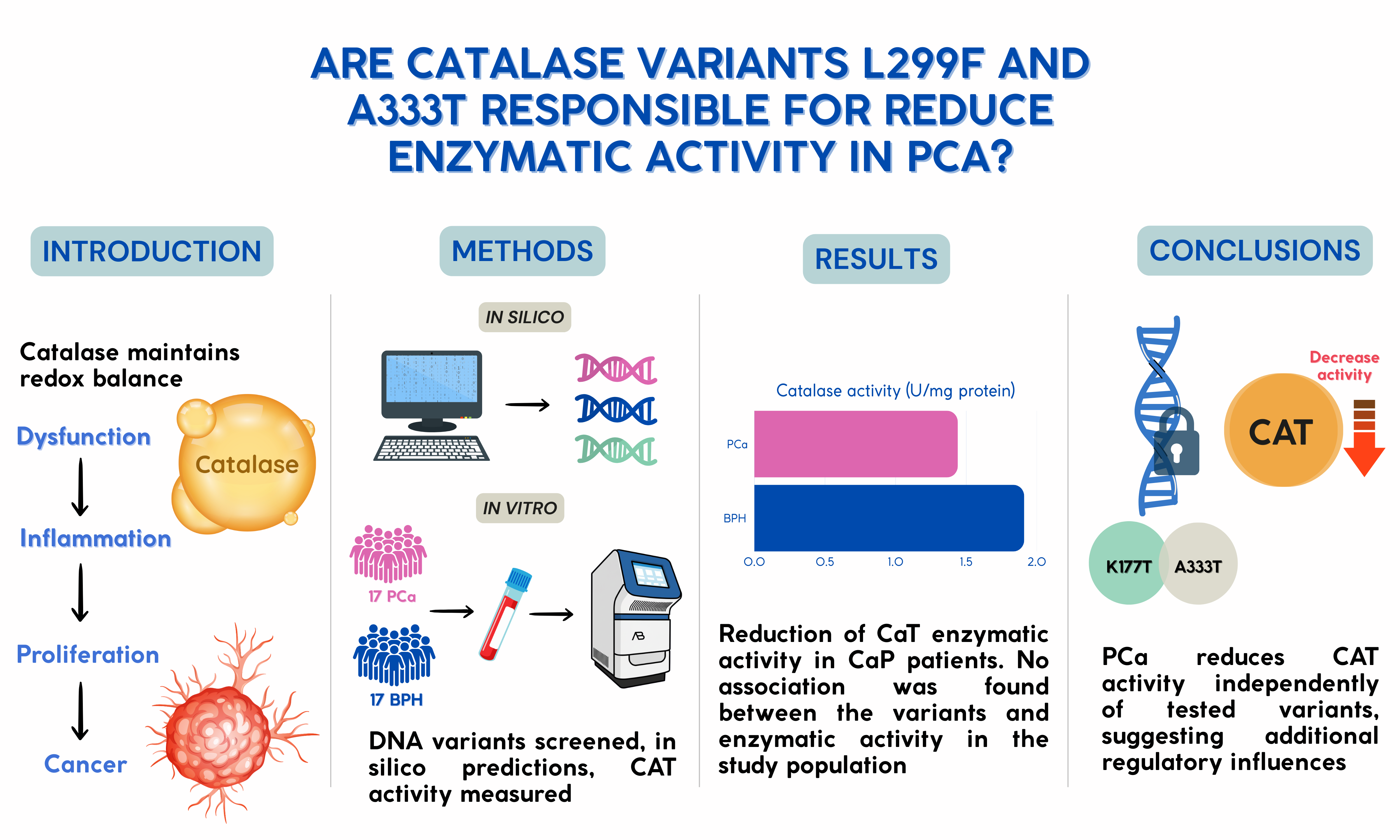

In this study, we combined an in silico and experimental approach to identify and characterize potentially pathogenic mutations in the human CAT gene. Through structural and functional prediction tools, variants with potential impact on enzymatic activity were selected, genotyped in human samples, and finally, their functional effect was evaluated through enzymatic activity assays. Therefore, this study aims to identify functionally relevant variants in CAT, establishing a connection between bioinformatic prediction, genetic analysis, and functional validation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Processing

Peripheral venous blood (4 mL) was collected in EDTA tubes from individuals submitted to PSA analyses at the Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado “Dr. Miguel Angel Camacho Zamudio”, with informed consent. Samples were stored at 5 °C and then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature (22–25 °C). Plasma (500 µL) was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C; the cellular pellet was kept at 5 °C for DNA extraction. Individuals were classified as prostate cancer patients (PCa) or prostatic hyperplasia patients (PH), according to the diagnosis confirmed by a medical specialist assigned to the institute.

2.2. DNA Extraction and Quantification

DNA was extracted in duplicate from 300 µL whole blood using the micromethod of Gustincich [

13] with modifications: lysis at 68 °C, chloroform extraction, CTAB treatment, NaCl wash, ethanol precipitation, and resuspension in TE buffer at 55 °C for 3 h. DNA purity and concentration were measured spectrophotometrically (DS-11, DeNovix®) at 260/280 nm with 320 nm correction. Samples were normalized to 10 ng/µL. Integrity was verified by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.3. Variant Selection and In Silico Analysis

Missense variants in CAT classified as VUS or pathogenic were identified from NCBI, UniProt, ClinVar, SNPedia, and PDB. Variant c.997G>A (p.Ala333Thr) was selected. The CAT crystal structure (PDB:1DGF) was analyzed with UCSF Chimera; structural validation was done by Ramachandran plot in WinCoot. Functional impact was predicted using SNPs&GO, PolyPhen-2, and I-Mutant 2.0 at 25 °C, pH 7.0. Mutagenesis and conformational changes were modeled in PyMOL 3.0.

2.4. Genotyping by rhAmp™ SNP Assay

Genotyping of 34 patients, comprising 17 PCa and 17 PH, was performed in 10 µL reactions containing 5.3 µL Master + Reporter Mix (20:1), 0.5 µL probe, 2.2 µL water, and 2 µL DNA (10 ng/µL). Probes were labeled with FAM (allele G) and YakimaYellow (allele A); ROX was used as reference dye. PCR: 95 °C 10 min; 40 cycles of 95 °C 10 s, 60 °C 30 s, 68 °C 20 s; final extension at 99.9 °C for 15 min. Reactions were processed on StepOnePlus™ and analyzed with TaqMan Genotyper Software v2.3.

2.5. CAT Activity

CAT activity was determined in the study population according to the method described by Aebi [

14], with slight modifications. Briefly, 6 µl of serum was mixed with 120 µl of 15 mM H₂O₂ dissolved in a 100 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.5), after which the reaction kinetics were carried out immediately for five minutes. Readings were taken every 10 seconds at 240 nm using an EPOCH 2NS microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). CAT activity was expressed in U/mg of protein. One unit of CAT activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the breakdown of 1 mmol of H₂O₂ per minute at 30 °C.

2.6. Protein Concentration

Protein concentration in the serum was determined according to the method described by Bradford [

15]. Briefly, 5 µL of serum was mixed with 250 µL of Bradford reagent (B6916, Sigma Aldrich) and incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature (25°C). Absorbance was measured at 595 nm using an EPOCH 2NS microplate spectrophotometer (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The results were calculated from a bovine serum albumin standard curve (0.1–1.4 mg/mL).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

For antioxidant data, differences between experimental groups were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test [

16]. The statistical tests were conducted using RStudio v4.1, with a significance level set at

p < 0.05. The results were visualized using a violin and boxplot generated with the ggplot2 package v3.4.3.

3. Results

3.1. CAT Activity

Figure 1 shows the serum CAT activity in both groups. The CAT activity was significantly decreased in the PCa group (1.44±0.24 U/mg of protein) in comparison to the control group (1.91 ±0.25 U/mg of protein) (

p = 0.033).

No significant correlation was observed between CAT enzymatic activity and either age or serum PSA levels in patients with PCa (p = 0.607 and p = 0.379, respectively). To assess whether the dysregulation in CAT activity observed between patients with and without cancer might be associated with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or arterial hypertension, the potential influence of these conditions was evaluated; however, no statistically significant differences in CAT activity were found concerning these pathologies (p = 0.222 and p = 0.186, respectively).

3.2. In Silico Analysis of CAT Variants

A search for genetic variants of the CAT enzyme was conducted in the ClinVar database from NCBI, initially retrieving 67 mutations. After initial evaluation (excluding conflicting classifications between studies and mutations reported as benign or probably benign), nine variants were selected: K177T, G216V, L299F, A333T, L351P, M392I, V450M, N452S, and H466P.

The selected variants were evaluated

in silico using I-Mutant 2.0, SNPs&GO, and PolyPhen-2 to estimate their potential impact on CAT stability and function (

Table 1). According to I-Mutant 2.0, eight mutations were predicted to be potentially disease-associated, while N452S was classified as neutral. SNPs&GO predicted a decrease in protein stability for all variants except K177T. Consistently, PolyPhen-2 classified most mutations as probably damaging, including K177T, G216V, A333T, L351P, V450M, and H466P, indicating a high likelihood of functional disruption. L299F and M392I were considered possibly damaging, reflecting a moderate potential impact, whereas N452S was also predicted as benign, suggesting no significant effect on CAT function. These converging predictions suggest that several of the variants may compromise the structural integrity or enzymatic activity of CAT, warranting further structural and functional validation.

Structural validation of the selected variants was based on the crystal structure of human CAT available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession code 1DGF. Three-dimensional visualization using UCSF Chimera confirmed that residues L299, A333, and V450 are present and well-defined in the model (

Figure 2a). Additionally, it was verified that the entire amino acid sequence of chain A is represented without gaps (

Figure 2b), supporting the suitability of this model for further structural studies.

3.3. Stereochemical Validation of the Protein Structure

To assess the overall quality of the structural model, a Ramachandran plot was generated using WinCoot (

Figure 3). The analysis revealed that 94.4% of residues fall within favored regions, 4.7% in allowed regions, and only 0.87% were outliers, indicating that the model has an appropriate stereochemical conformation and is structurally reliable for subsequent modeling and simulation analyses.

3.4. Mutational Status

Allelic discrimination genotyping for the L299F and A333T mutations was performed in the study population. All individuals (100%) exhibited the homozygous wild-type genotypes: CC for L299F and GG for A333T, respectively.

4. Discussion

The significant decrease in serum catalase activity observed in PCa patients compared to controls highlights a critical impairment of the antioxidant defense system, reinforcing the well-established link between oxidative stress and prostate tumorigenesis. Catalase enzymatically decomposes hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species that causes DNA damage and activates oncogenic signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT and NF-κB, which promote tumor cell proliferation and survival [

17,

18,

19]. Reduced catalase activity leads to an accumulation of ROS, intensifying oxidative damage and supporting a microenvironment conducive to cancer progression [

20].

Our computational analyses provide compelling evidence that specific catalase missense variants could severely disrupt the enzyme’s structural integrity and function. Using multiple complementary

in silico prediction tools such as I-Mutant 2.0, SNPs&GO, and PolyPhen-2, we identified several mutations (including K177T, G216V, A333T, L351P, V450M, and H466P) as likely deleterious, consistently predicted to destabilize the protein or impair its catalytic activity. These tools have demonstrated reliability in predicting the impact of mutations on protein stability and function [

21,

22]. Structural validation using the human catalase crystal structure confirmed that these residues reside in critical, conserved regions essential for enzymatic activity [

12].

Stereochemical analysis using the Ramachandran plot revealed that 94.40% of the residues were located in preferred regions, 4.73% in allowed regions, and only 0.87% as outliers, exceeding the structural quality criteria established in the literature, where it is considered acceptable for more than 90% of residues to be located in favored regions [

23,

24]. These results are consistent with studies of high-resolution models that allow for a small percentage in permitted regions associated with flexible zones, while the low proportion of outliers contrasts positively with lower-resolution models that typically have values above 2% [

25]. The combined computational evidence strongly indicates these variants may compromise catalase’s role in maintaining redox balance, a key factor in preventing oxidative damage linked to prostate cancer progression.

However, genotyping analysis of two prioritized variants, L299F and A333T, in our cohort revealed exclusively wild-type genotypes, indicating these mutations are absent or extremely rare in the Mexican population. Similar observations have been reported in studies where potentially deleterious variants predicted by computational tools were not detected or found at very low frequencies in specific populations [

26]. This finding indicates that despite the strong theoretical pathogenic potential predicted by bioinformatics tools, these coding mutations do not account for the observed reduction in catalase activity in our patient group. This disparity underscores a crucial consideration: while

in silico analyses are powerful for identifying candidate pathogenic variants, their actual prevalence and functional impact in clinical populations require validation through genetic and biochemical studies [

27,

28].

It is important to contextualize these results within the broader genetic landscape of catalase regulation in PCa. Existing literature suggests that common variation influencing catalase activity predominantly resides in promoter or regulatory regions, such as the rs1001179 (C-262T) polymorphism, which modulates transcriptional expression rather than coding sequence alterations. These regulatory variants have been consistently associated with changes in catalase levels and cancer risk in multiple populations, emphasizing that modulation of gene expression is likely a more significant driver of enzymatic activity changes than rare missense mutations [

9,

29].

Additionally, catalase activity can be influenced by post-translational modifications and oxidative inactivation mechanisms that do not involve genetic mutations, further complicating the relationship between genotype and enzymatic phenotype [

30,

31]. The limited sample size for genotyping in this study may also reduce the likelihood of detecting rare pathogenic variants. Moreover, serum catalase activity reflects the integrated effect of multiple factors beyond single-gene mutations, including environmental and epigenetic influences.

Functionally, androgen receptor signaling has been shown to suppress catalase expression, leading to increased ROS accumulation and enhanced PCa cell proliferation via FOXO3a-mediated pathways. Experimental catalase knockdown models demonstrate decreased tumor cell proliferation and migration, highlighting the enzyme’s pivotal role in modulating tumor aggressiveness [

32,

33,

34]. These findings suggest that transcriptional repression and post-translational mechanisms may contribute more substantially to reduced catalase activity in PCa than rare coding variants.

In summary, this study integrates computational, structural, genetic, and biochemical evidence to highlight catalase as a critical player in PCa pathophysiology. While in silico analyses identified potentially damaging catalase variants with strong theoretical impact on enzyme function, their absence in the current cohort indicates that other regulatory and non-genetic mechanisms underlie the decreased enzymatic activity observed. Future comprehensive studies should combine broad genetic screening, gene expression profiling, and functional assays to fully elucidate the complex regulation of catalase in PCa and its potential as a biomarker or therapeutic target.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that PCa significantly reduces the enzymatic activity of CAT, independent of age, serum PSA levels, or comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or high blood pressure, suggesting that the decrease in CAT activity is attributed to the presence of cancer. In silico predictions indicated that mutations such as K177T, G216V, and L351P may compromise CAT stability and function, whereas genotyping revealed wild-type genotypes for L299F and A333T in both groups. Thus, the observed decrease in CAT activity could also reflect mechanisms beyond the analyzed variants, potentially affecting its expression or function. The findings highlight the role of the enzymatic antioxidant system in the tumor microenvironment, potentially influenced by epigenetic, regulatory, or post-translational factors. However, validation in larger and more diverse populations is required to confirm these observations and clarify the interplay between mutations on enzyme function and the metabolic and epigenetic regulation of PCa.

Author Contributions

Martin Irigoyen-Arredondo: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Alejandra Martínez-Camberos: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Lizeth Flores-Mendez: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Crisantema Hernández: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. José Geovanni Romero-Quintana: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Martha Patricia Gallegos-Arreola: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Asbiel Felipe Garibaldi-Ríos: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Edith Eunice García Alvarez: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. Fernando Bergez-Hernandez: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration.

Funding

This work was supported by the Programa del Apoyo al Fortalecimiento de la Investigación y el Posgrado from Universidad Autónoma de Occidente, Mazatlán, México.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Universidad Autónoma de Occidente (March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to confidentiality restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge undergraduate students Alexa Sofia López Cázares, Alondra Berenice Ríos Márquez, Joaly Elizabeth Baldenegro Rodríguez, Estrella Bianca Lizárraga Estrada, and Jesús Iván Juárez Fragoza for their assistance with various technical aspects. We also thank the Biomedical and Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Universidad Politécnica de Sinaloa for providing access to the real-time PCR thermocycler.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAT |

Catalase |

| PCa |

Prostate cancer |

| BPH |

Benign prostatic hyperplasia |

| PSA |

Prostate-specific antigen |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| VUS |

Varian of uncertain significance |

| PDB |

Protein Data Bank |

| UCSF |

University of California, San Francisco |

References

- Drăgoi, C.M.; Diaconu, C.C.; Nicolae, A.C.; Dumitrescu, I.-B. Redox Homeostasis and Molecular Biomarkers in Precision Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1163. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.-J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.E.; Rhie, S.J.; Yoon, S. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 2015, 24, 325–340. [CrossRef]

- Zahra, K.F.; Lefter, R.; Ali, A.; Abdellah, E.-C.; Trus, C.; Ciobica, A.; Timofte, D. The Involvement of the Oxidative Stress Status in Cancer Pathology: A Double View on the Role of the Antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9965916. [CrossRef]

- Gebicka, L.; Krych-Madej, J. The Role of Catalases in the Prevention/Promotion of Oxidative Stress. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 197, 110699. [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, S.A.; Freitas, J.R.; Conchinha, N.V.; Madureira, P.A. The Tumorigenic Roles of the Cellular REDOX Regulatory Systems. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 8413032. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C.; Dejeans, N.; Sid, B.; Beck, R.; Calderon, P.B.; Verrax, J. Catalase Overexpression in Mammary Cancer Cells Leads to a Less Aggressive Phenotype and an Altered Response to Chemotherapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011, 82, 1384–1390. [CrossRef]

- Kwei, K.A.; Finch, J.S.; Thompson, E.J.; Bowden, G.T. Transcriptional Repression of Catalase in Mouse Skin Tumor Progression. Neoplasia 2004, 6, 440–448. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Kang, H.; Lin, S.; Yang, P.; Dai, C.; Xu, P.; Li, S.; et al. Two Common Functional Catalase Gene Polymorphisms (Rs1001179 and Rs794316) and Cancer Susceptibility: Evidence from 14,942 Cancer Cases and 43,285 Controls. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 62954–62965. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, T.; Paszti, E.; Kaplar, M.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Goth, L. Further Acatalasemia Mutations in Human Patients from Hungary with Diabetes and Microcytic Anemia. Mutat. Res. 2015, 772, 10–14. [CrossRef]

- Galasso, M.; Gambino, S.; Romanelli, M.G.; Donadelli, M.; Scupoli, M.T. Browsing the Oldest Antioxidant Enzyme: Catalase and Its Multiple Regulation in Cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 264–272. [CrossRef]

- Góth, L.; Rass, P.; Páy, A. Catalase Enzyme Mutations and Their Association with Diseases. Mol. Diagn. J. Devoted Underst. Hum. Dis. Clin. Appl. Mol. Biol. 2004, 8, 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Gustincich, S.; Manfioletti, G.; Del Sal, G.; Schneider, C.; Carninci, P. A Fast Method for High-Quality Genomic DNA Extraction from Whole Human Blood. BioTechniques 1991, 11, 298–300, 302.

- Aebi, H. [13] Catalase in Vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Oxygen Radicals in Biological Systems; Academic Press, 1984; Vol. 105, pp. 121–126.

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Zar, J.H. Biostatistical Analysis; Prentice Hall, 1999; ISBN 978-0-13-081542-2.

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free Radicals, Metals and Antioxidants in Oxidative Stress-Induced Cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 1–40. [CrossRef]

- Trachootham, D.; Alexandre, J.; Huang, P. Targeting Cancer Cells by ROS-Mediated Mechanisms: A Radical Therapeutic Approach? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 579–591. [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, S.S.; Schumacker, P.T. Mitochondrial ROS in Cancer: Initiators, Amplifiers or an Achilles’ Heel? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721. [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.-Y.; Storz, P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496. [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P.; Casadio, R. I-Mutant2.0: Predicting Stability Changes upon Mutation from the Protein Sequence or Structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W306–W310. [CrossRef]

- Adzhubei, I.A.; Schmidt, S.; Peshkin, L.; Ramensky, V.E.; Gerasimova, A.; Bork, P.; Kondrashov, A.S.; Sunyaev, S.R. A Method and Server for Predicting Damaging Missense Mutations. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 248–249. [CrossRef]

- Chen, V.B.; Arendall, W.B.; Headd, J.J.; Keedy, D.A.; Immormino, R.M.; Kapral, G.J.; Murray, L.W.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. MolProbity: All-Atom Structure Validation for Macromolecular Crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 12–21. [CrossRef]

- Lovell, S.C.; Davis, I.W.; Arendall, W.B.; De Bakker, P.I.W.; Word, J.M.; Prisant, M.G.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. Structure Validation by Cα Geometry: ϕ,ψ and Cβ Deviation. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2003, 50, 437–450. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.N.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sasisekharan, V. Stereochemistry of Polypeptide Chain Configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 1963, 7, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.C.; Henikoff, S. Predicting the Effects of Amino Acid Substitutions on Protein Function. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2006, 7, 61–80. [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [CrossRef]

- Cirulli, E.T.; Goldstein, D.B. Uncovering the Roles of Rare Variants in Common Disease through Whole-Genome Sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 415–425. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, D.; Tian, P.; Shen, K.; Zhu, J.; Feng, M.; Wan, C.; Yang, T.; Chen, L.; Wen, F. The Catalase C-262T Gene Polymorphism and Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e679. [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Lin, C.-C.; Lett, C.; Karpinska, B.; Wright, M.H.; Foyer, C.H. Catalase: A Critical Node in the Regulation of Cell Fate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 199, 56–66. [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, Á.; Visiedo, F.; Domínguez-Riscart, J.; Durán-Ruiz, M.C.; Saez-Benito, A.; Lechuga-Sancho, A.M.; Mateos, R.M. Catalase Post-Translational Modifications as Key Targets in the Control of Erythrocyte Redox Homeostasis in Children with Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 191, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Giginis, F.; Wang, J.; Chavez, A.; Martins-Green, M. Catalase as a Novel Drug Target for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2023, 13, 2644–2656.

- Gupta, A.; Butts, B.; Kwei, K.A.; Dvorakova, K.; Stratton, S.P.; Briehl, M.M.; Bowden, G.T. Attenuation of Catalase Activity in the Malignant Phenotype Plays a Functional Role in an in Vitro Model for Tumor Progression. Cancer Lett. 2001, 173, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.; Metheni, M.; Batteux, F.; Langsley, G. TGF-Β2, Catalase Activity, H2O2 Output and Metastatic Potential of Diverse Types of Tumour. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 134, 282–287. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).