Submitted:

09 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

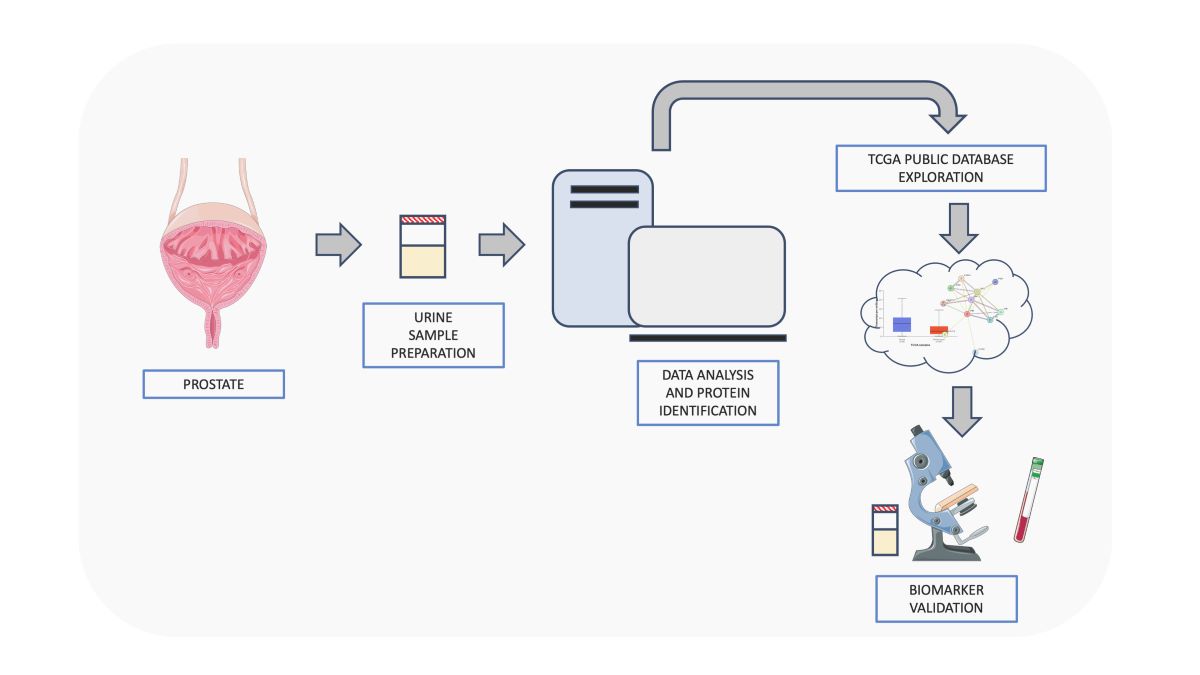

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation of Total Proteins from Urine

2.2. Protein Extraction and Enzymatic Digestion

2.3. Proteomic Analysis by nanoLC-MS/MS

2.4. MS/MS Data Processing

2.5. Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Label-Free Quantitative Analysis

2.7. Reconstruction of PPI Network Model and Functional Modules Identification

2.8. Topological Analysis of PPI and Co-Expression Network Models

2.9. TCGA Bioinformatic Analysis

3. Results

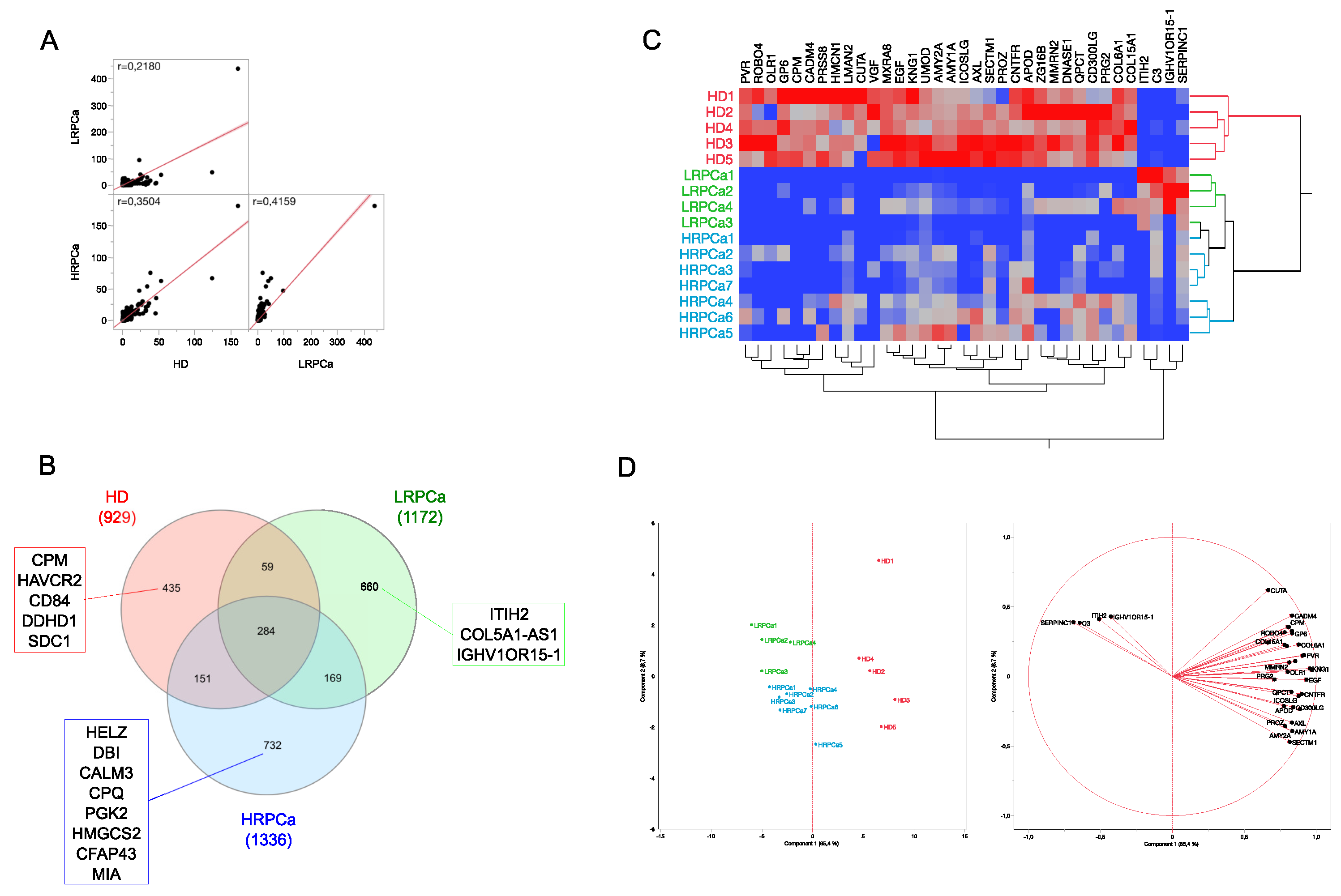

3.1. Protein Profiling of Urine from Healthy Controls and Patients Affected by Prostate Cancer at Low- and High-Risk Level

3.2. Differentially Abundant Proteins (DAPs) by Comparing Urine Protein Profiles from Healthy Controls and Patients Affected by Prostate Cancer at Low- and High-Risk Level

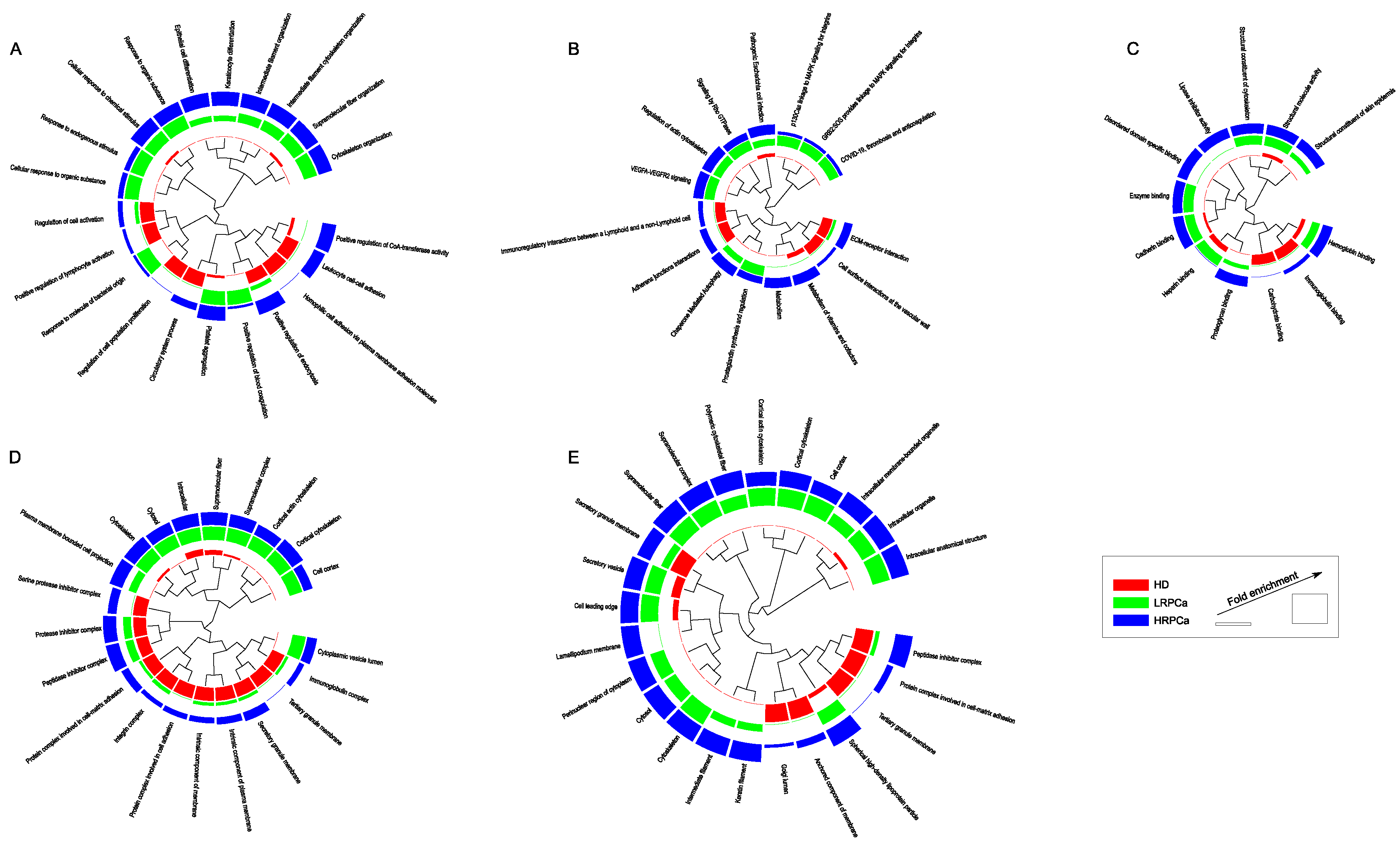

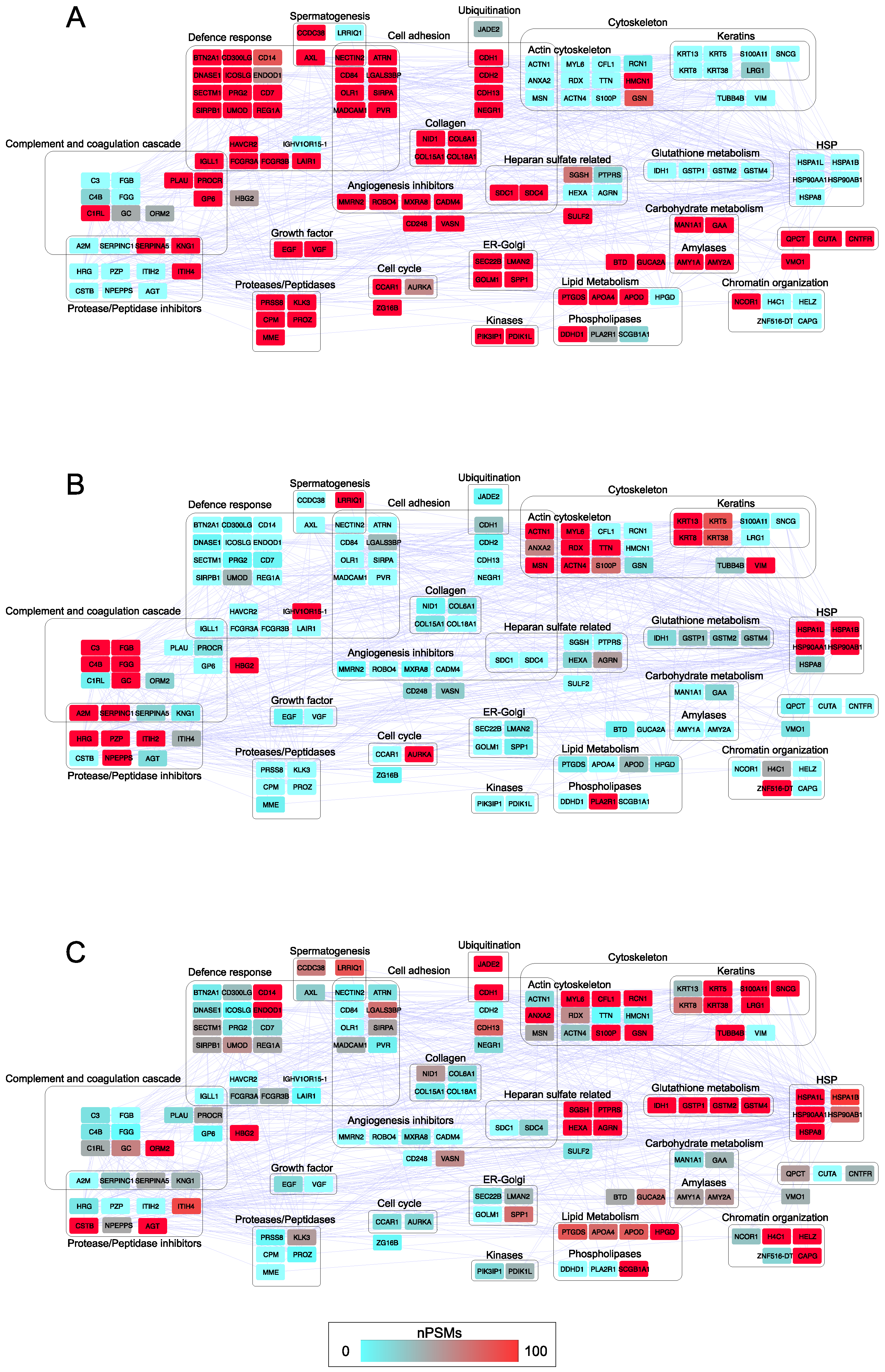

3.3. Functional Modules Marking the Urine Proteome of Healthy Controls and Patients Affected by Prostate Cancer at Low- and High-Risk Level

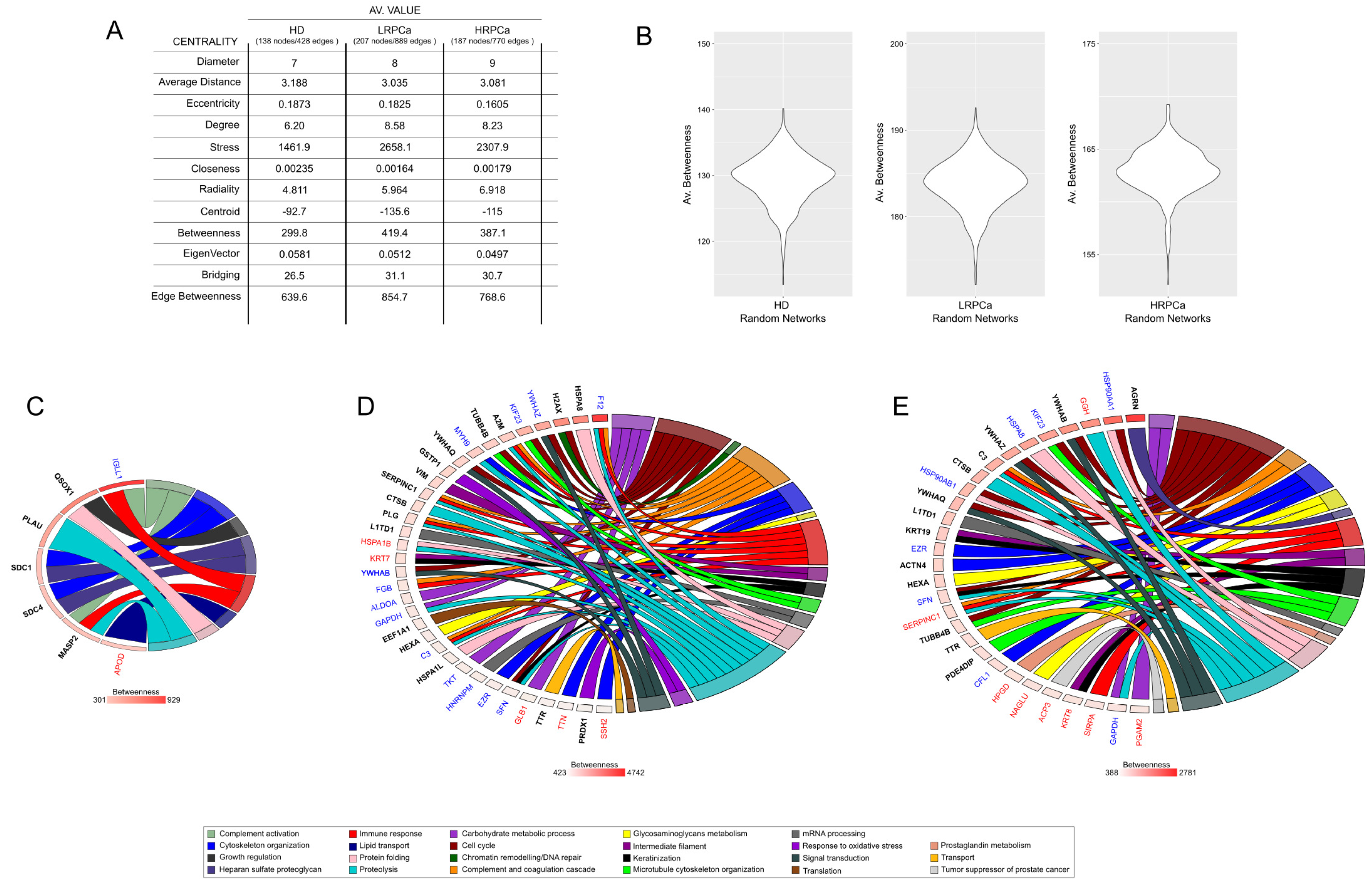

3.4. Network Hubs and Bottlenecks in Urine of Healthy Controls and Patients Affected by Prostate Cancer at Low- and High-Risk Level

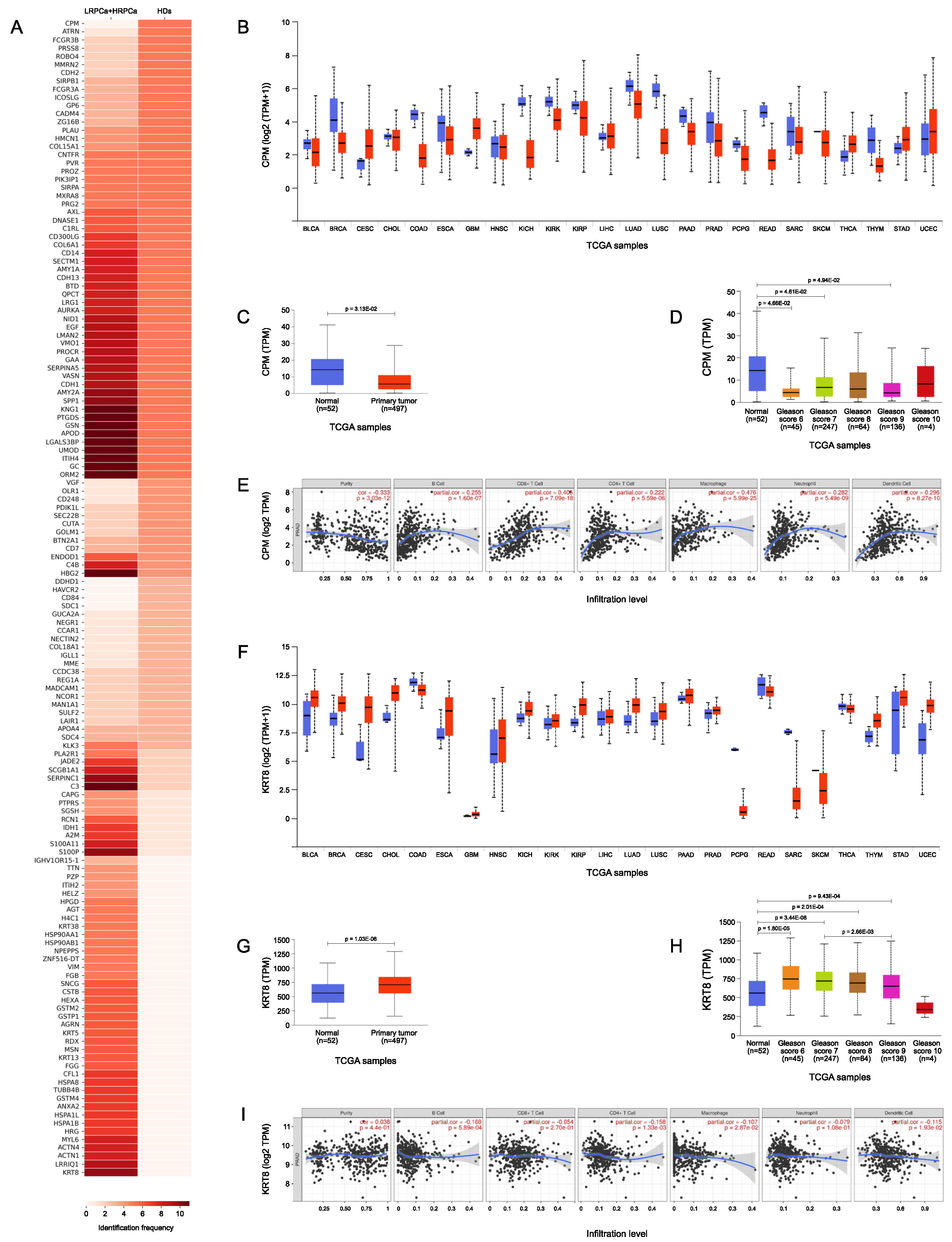

3.5. TCGA Bioinformatic Analysis: HDs vs PCa

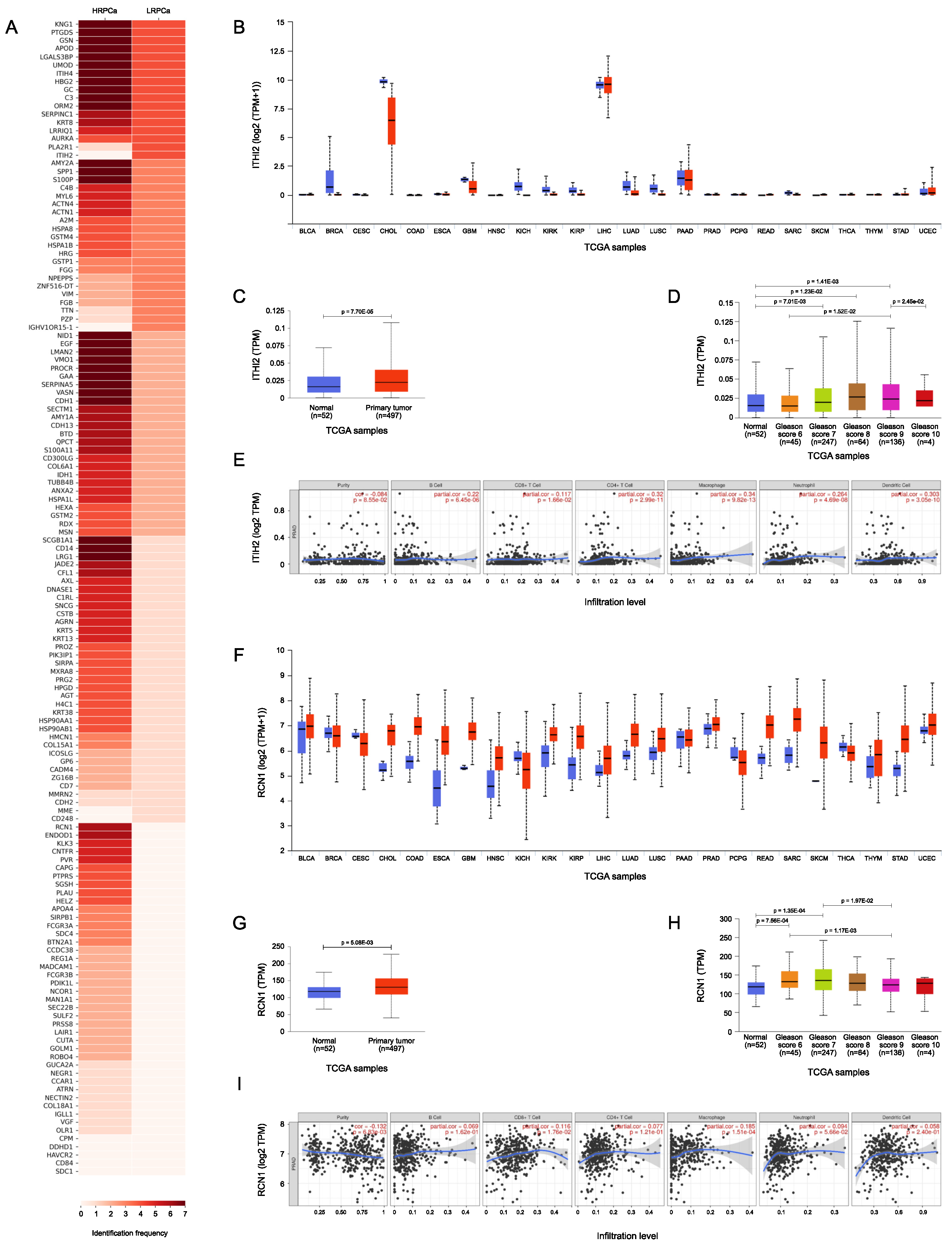

3.6. TCGA Bioinformatic Analysis: LRPCa vs HRPCa

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| DRE | Digital Rectal Examination |

| TRUS | Transrectal Ultrasound |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| GS | Gleason Score |

| mpMRI | multi-parametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| ISUP | International Society of Urological Pathology |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| CAPRA | Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| PPI | Protein-Protein Interaction |

| HDs | Healthy Donors |

| LRPCa | Low-risk PCa |

| HRPCa | High-risk PCa |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic Acid |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| FDR | False Discovery Rates |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| DAPs | Differentially Abundant Proteins |

| IF | Identification Frequency |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| DAve | Differential Average |

| PC | Principal Component |

| PSM | Peptide Spectrum Match |

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohaar, I.; Petrovics, G.; Srivastava, S. A Rich Array of Prostate Cancer Molecular Biomarkers: Opportunities and Challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, M.; Jia, M.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Gao, X.; Tang, B. Precise prostate cancer diagnosis using fluorescent nanoprobes for detecting PSA and PSMA in serum. Chemical Communications 2024, 60, 5181–5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, P.A.; Moch, H.; Cubilla, A.L.; Ulbright, T.M.; Reuter, V.E. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs—Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. European Urology 2016, 70, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooperberg, M.R. Clinical risk stratification for prostate cancer: Where are we, and where do we need to go? Canadian Urological Association Journal 2017, 11, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.U.; El-Shater Bosaily, A.; Brown, L.C.; Gabe, R.; Kaplan, R.; Parmar, M.K.; Collaco-Moraes, Y.; Ward, K.; Hindley, R.G.; Freeman, A.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of multi-parametric MRI and TRUS biopsy in prostate cancer (PROMIS): a paired validating confirmatory study. The Lancet 2017, 389, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamlouche, F.; Yehya, A.; Zeid, Y.; Fakhereddine, H.; Fawaz, J.; Liu, Y.N.; Al-Sayegh, M.; Abou-Kheir, W. MicroRNAs as clinical tools for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy in prostate cancer. Translational Oncology 2023, 28, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; da Silveira, W.A.; Kelly, R.C.; Overton, I.; Allott, E.H.; Hardiman, G. Long non-coding RNAs and their potential impact on diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy in prostate cancer: racial, ethnic, and geographical considerations. Expert Review of Molecular Diagnostics 2021, 21, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montironi, R.; Cimadamore, A.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Scarpelli, M. Update on Prostate Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Prediction to Response to Therapy. Cells 2020, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, F.A.; Lotan, T.L. The Genomic and Molecular Pathology of Prostate Cancer: Clinical Implications for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Advances in Anatomic Pathology 2019, 27, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minas, T.Z.; Candia, J.; Dorsey, T.H.; Baker, F.; Tang, W.; Kiely, M.; Smith, C.J.; Zhang, A.L.; Jordan, S.V.; Obadi, O.M.; et al. Serum proteomics links suppression of tumor immunity to ancestry and lethal prostate cancer. Nature Communications 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modlin, I.M.; Kidd, M.; Drozdov, I.A.; Boegemann, M.; Bodei, L.; Kunikowska, J.; Malczewska, A.; Bernemann, C.; Koduru, S.V.; Rahbar, K. Development of a multigenomic liquid biopsy (PROSTest) for prostate cancer in whole blood. The Prostate 2024, 84, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, R.A.; Schitcu, V.H.; Budisan, L.; Raduly, L.; Braicu, C.; Petrut, B.; Coman, I.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Al Hajjar, N. Evaluation of miR-148a-3p and miR-106a-5p as Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer: Pilot Study. Genes 2024, 15, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Bosma, J.S.; Twilt, J.J.; van Ginneken, B.; Bjartell, A.; Padhani, A.R.; Bonekamp, D.; Villeirs, G.; Salomon, G.; Giannarini, G.; et al. Artificial intelligence and radiologists in prostate cancer detection on MRI (PI-CAI): an international, paired, non-inferiority, confirmatory study. The Lancet Oncology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanase, C.P.; Codrici, E.; Popescu, I.D.; Mihai, S.; Enciu, A.M.; Necula, L.G.; Preda, A.; Ismail, G.; Albulescu, R. Prostate cancer proteomics: Current trends and future perspectives for biomarker discovery. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 18497–18512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, G.M.; Raghunathan, R.; Ashenden, S.; Zhang, B.; Miele, E.; Jarnuczak, A.F. Proteomics of prostate cancer serum and plasma using low and high throughput approaches. Clinical Proteomics 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordström, M.; Wingren, C.; Rose, C.; Bjartell, A.; Becker, C.; Lilja, H.; Borrebaeck, C.A.K. Identification of plasma protein profiles associated with risk groups of prostate cancer patients. PROTEOMICS – Clinical Applications 2014, 8, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Quek, S.I.; Gao, Y.; Nicora, C.D.; Nie, S.; Fillmore, T.L.; Liu, T.; Rodland, K.D.; Smith, R.D.; Leach, R.J.; et al. Multiplexed targeted mass spectrometry assays for prostate cancer-associated urinary proteins. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 101887–101898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzi, M.; Culig, Z.; Heidegger, I.; Mokou, M.; Latosinska, A.; Roesch, M.C.; Merseburger, A.S.; Makridakis, M.; Vlahou, A.; Blanca-Pedregosa, A.; et al. Mass Spectrometry-Based Biomarkers to Detect Prostate Cancer: A Multicentric Study Based on Non-Invasive Urine Collection without Prior Digital Rectal Examination. Cancers 2023, 15, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lygirou, V.; Fasoulakis, K.; Stroggilos, R.; Makridakis, M.; Latosinska, A.; Frantzi, M.; Katafigiotis, I.; Alamanis, C.; Stravodimos, K.G.; Constantinides, C.A.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Prostate Cancer FFPE Samples Reveals Markers of Disease Progression and Aggressiveness. Cancers 2022, 14, 3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawahara, R.; Recuero, S.; Nogueira, F.C.S.; Domont, G.B.; Leite, K.R.M.; Srougi, M.; Thaysen-Andersen, M.; Palmisano, G. Tissue Proteome Signatures Associated with Five Grades of Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. PROTEOMICS 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhondt, B.; Geeurickx, E.; Tulkens, J.; Van Deun, J.; Vergauwen, G.; Lippens, L.; Miinalainen, I.; Rappu, P.; Heino, J.; Ost, P.; et al. Unravelling the proteomic landscape of extracellular vesicles in prostate cancer by density-based fractionation of urine. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Kume, H.; Matsuzaki, K.; Kawashima, A.; Ujike, T.; Nagahara, A.; Uemura, M.; Miyagawa, Y.; Tomonaga, T.; Nonomura, N. Proteomic analysis of urinary extracellular vesicles from high Gleason score prostate cancer. Scientific Reports 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øverbye, A.; Skotland, T.; Koehler, C.J.; Thiede, B.; Seierstad, T.; Berge, V.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Identification of prostate cancer biomarkers in urinary exosomes. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 30357–30376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Fan, J.; Guo, J.; Wu, T.; Lu, D.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Alterations of plasma exosomal proteins and motabolies are associated with the progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Journal of Translational Medicine 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, D.; Casadonte, F.; Terracciano, R.; Damiano, R.; Savino, R.; Sindona, G.; Napoli, A. Targeted proteomic approach in prostatic tissue: a panel of potential biomarkers for cancer detection. Oncoscience 2016, 3, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latosinska, A.; Davalieva, K.; Makridakis, M.; Mullen, W.; Schanstra, J.P.; Vlahou, A.; Mischak, H.; Frantzi, M. Molecular Changes in Tissue Proteome during Prostate Cancer Development: Proof-of-Principle Investigation. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, T.A. ; Hedman,.K.; Dimitriou, M.; Koprulu, M.; Figiel, S.; Yin, W.; Johansson, M.; Watts, E.L.; Atkins, J.R.; Sokolov, A.V.; et al. Identifying proteomic risk factors for overall, aggressive and early onset prostate cancer using Mendelian randomization and tumor spatial transcriptomics 2023. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marques, F.; Liu, S.; Totten, S.M.; Bermudez, A.; Tanimoto, C.; Hsu, E.; Nolley, R.; Hembree, A.; Stoyanova, T.; Brooks, J.D.; et al. Protein signatures to distinguish aggressive from indolent prostate cancer. The Prostate 2022, 82, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CHEN, C.; SHEN, H.; ZHANG, L.G.; LIU, J.; CAO, X.G.; YAO, A.L.; KANG, S.S.; GAO, W.X.; HAN, H.; CAO, F.H.; et al. Construction and analysis of protein-protein interaction networks based on proteomics data of prostate cancer. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2016, 37, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; You, S.; Freeman, M.R.; Yang, W. Quantitative proteomic analysis of prostate tissue specimens identifies deregulated protein complexes in primary prostate cancer. Clinical Proteomics 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, D.; Zoppis, I.; Mauri, G.; Mauri, P.; Di Silvestre, D. From protein-protein interactions to protein co-expression networks: a new perspective to evaluate large-scale proteomic data. EURASIP journal on bioinformatics & systems biology 2017, 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Silvestre, D.; Brambilla, F.; Lavatelli, F.; Chirivì, M.; Canetti, D.; Bearzi, C.; Rizzi, R.; Bijzet, J.; Hazenberg, B.P.C.; Bellotti, V.; et al. The Protein Network in Subcutaneous Fat Biopsies from Patients with AL Amyloidosis: More Than Diagnosis? Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis, 2 ed.; Springer-Verlag New York, 2016.

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol. ; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Research 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Silvestre, D.; Brambilla, F.; Mauri, P.L. Multidimensional protein identification technology for direct-tissue proteomics of heart. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2013, 1005, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maere, S.; Heymans, K.; Kuiper, M. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of Gene Ontology categories in Biological Networks. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3448–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scardoni, G.; Tosadori, G.; Faizan, M.; Spoto, F.; Fabbri, F.; Laudanna, C. Biological network analysis with CentiScaPe: centralities and experimental dataset integration. F1000Research 2014, 3, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfin, S.; Kumar, D.; Lomagno, A.; Mauri, P.L.; Di Silvestre, D. Differentially Expressed Genes, miRNAs and Network Models: A Strategy to Shed Light on Molecular Interactions Driving HNSCC Tumorigenesis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosadori, G.; Bestvina, I.; Spoto, F.; Laudanna, C.; Scardoni, G. Creating, generating and comparing random network models with NetworkRandomizer. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Fu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Cohen, D.; Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Li, B.; Liu, X.S. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, W509–W514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Henrique, R.; Vitorino, R.; Fardilha, M. Bioinformatic analysis of dysregulated proteins in prostate cancer patients reveals putative urinary biomarkers and key biological pathways. Medical Oncology 2021, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraon, P.; Cretu, D.; Musrap, N.; Karagiannis, G.S.; Batruch, I.; Drabovich, A.P.; van der Kwast, T.; Mizokami, A.; Morrissey, C.; Jarvi, K.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals That Enzymes of the Ketogenic Pathway Are Associated with Prostate Cancer Progression. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2013, 12, 1589–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuwirt, H.; Bouchal, J.; Kharaishvili, G.; Ploner, C.; Jöhrer, K.; Pitterl, F.; Weber, A.; Klocker, H.; Eder, I.E. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote prostate tumor growth and progression through upregulation of cholesterol and steroid biosynthesis. Cell Communication and Signaling 2020, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanie Hilario, A.K. Approaches to dimensionality reduction in proteomic biomarker studies. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2008, 2, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cao, F.H.; Li, Z.G.; Zhang, L.G.; Liu, J.; Chen, N.; Yao, A.L.; Kang, S.S.; Gao, W.X.; Han, H.; et al. Bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed proteins in prostate cancer based on proteomics data. OncoTargets and Therapy, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davalieva, K.; Kiprijanovska, S.; Maleva Kostovska, I.; Stavridis, S.; Stankov, O.; Komina, S.; Petrusevska, G.; Polenakovic, M. Comparative Proteomics Analysis of Urine Reveals Down-Regulation of Acute Phase Response Signaling and LXR/RXR Activation Pathways in Prostate Cancer. Proteomes 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortvrindt, C.; Speeckaert, R.; Delanghe, J.R.; Speeckaert, M.M. Urinary Epidermal Growth Factor: A Promising “Next Generation” Biomarker in Kidney Disease. American Journal of Nephrology 2022, 53, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGwire, G.B.; Skidgel, R.A. Extracellular Conversion of Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) to des-Arg53-EGF by Carboxypeptidase M. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1995, 270, 17154–17158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzon, E.; Colladel, R.; Andreuzzi, E.; Marastoni, S.; Todaro, F.; Schiappacassi, M.; Ligresti, G.; Colombatti, A.; Mongiat, M. MULTIMERIN2 impairs tumor angiogenesis and growth by interfering with VEGF-A/VEGFR2 pathway. Oncogene 2011, 31, 3136–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Pinilla-Baquero, A.; Faulkner, J.; Song, X.; Prabhakar, P.; Qiu, H.; Moremen, K.W.; Ludwig, A.; Dempsey, P.J.; Azadi, P.; et al. Robo4 is constitutively shed by ADAMs from endothelial cells and the shed Robo4 functions to inhibit Slit3-induced angiogenesis. Scientific Reports 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.W.; Jung, Y.K.; Lee, E.J.; Park, H.R.; Kim, G.W.; Jeong, J.H.; Han, M.S.; Choi, J.Y. DICAM inhibits angiogenesis via suppression of AKT and p38 MAP kinase signalling. Cardiovascular Research 2013, 98, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifatbegovic, F.; Frech, C.; Abbasi, M.R.; Taschner-Mandl, S.; Weiss, T.; Schmidt, W.M.; Schmidt, I.; Ladenstein, R.; Ambros, I.M.; Ambros, P.F. Neuroblastoma cells undergo transcriptomic alterations upon dissemination into the bone marrow and subsequent tumor progression. International Journal of Cancer 2017, 142, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muazzam, A.; Spick, M.; Cexus, O.N.F.; Geary, B.; Azhar, F.; Pandha, H.; Michael, A.; Reed, R.; Lennon, S.; Gethings, L.A.; et al. A Novel Blood Proteomic Signature for Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katafigioti, A.; Katafigiotis, I.; Sfoungaristos, S.; Alamanis, C.; Stravodimos, K.; Anastasiou, I.; Roumelioti, E.; Duvdevani, M.; Constantinides, C. In the search of novel urine biomarkers for the early diagnosis of prostate cancer. Intracellular or secreted proteins as the target group? Where and how to search for possible biomarkers useful in the everyday clinical practice. Archivio Italiano di Urologia e Andrologia 2016, 88, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y. Network analysis of ChIP-Seq data reveals key genes in prostate cancer. European Journal of Medical Research 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Sharma, N. Quantitative SWATH-Based Proteomic Profiling for Identification of Mechanism-Driven Diagnostic Biomarkers Conferring in the Progression of Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Dong, R.N.; Lin, T.T.; Lin, T.; Lin, Y.Z.; Chen, S.H.; Zhu, J.M.; Ke, Z.B.; Huang, F.; Chen, Y.H.; et al. Development and Validation of Novel Biomarkers Related to M2 Macrophages Infiltration by Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis in Prostate Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brünnert, D.; Langer, C.; Zimmermann, L.; Bargou, R.C.; Burchardt, M.; Chatterjee, M.; Stope, M.B. The heat shock protein 70 inhibitor VER155008 suppresses the expression of HSP27, HOP and HSP90β and the androgen receptor, induces apoptosis, and attenuates prostate cancer cell growth. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2019, 121, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Jia, B. Advances in the role of heat shock protein 90 in prostate cancer. Andrologia 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryza, T.; Bock, N.; Lovell, S.; Rockstroh, A.; Lehman, M.L.; Lesner, A.; Panchadsaram, J.; Silva, L.M.; Srinivasan, S.; Snell, C.E.; et al. The molecular function of kallikrein-related peptidase 14 demonstrates a key modulatory role in advanced prostate cancer. Molecular Oncology 2019, 14, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Song, W.; Xu, H.; Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, Z.; Yang, X. Oncogenic Properties of NEAT1 in Prostate Cancer Cells Depend on the CDC5L–AGRN Transcriptional Regulation Circuit. Cancer Research 2018, 78, 4138–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sudandiradoss, C. Transcriptomic analysis of castration, chemo-resistant and metastatic prostate cancer elucidates complex genetic crosstalk leading to disease progression. Functional & Integrative Genomics 2021, 21, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, J.O.; White, J.; Elhussin, I.; Duduyemi, B.M.; Karanam, B.; Yates, C.; Wang, H. Molecular and pathological subtypes related to prostate cancer disparities and disease outcomes in African American and European American patients. Frontiers in Oncology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, N.; Ocarez, N.; Castellón, E.A.; Mejía, N.; de Herreros, A.G.; Contreras, H.R. The transcriptional factor ZEB1 represses Syndecan 1 expression in prostate cancer. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.; Alborelli, I.; Manzo, M.; Calgua, B.; Keller, E.B.; Vuaroqueaux, V.; Quagliata, L.; Rentsch, C.A.; Spagnoli, G.C.; Diener, P.A.; et al. Critical Evaluation of Transcripts and Long Noncoding RNA Expression Levels in Prostate Cancer Following Radical Prostatectomy. Pathobiology 2023, 90, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.R.; Graves, B.; Pruitt, F.; Chaib, H.; Lynch, J.E.; Cox, A.K.; Sequeria, L.; van Golen, K.L.; Evans, A.; Czymmek, K.; et al. Novel surface expression of reticulocalbin 1 on bone endothelial cells and human prostate cancer cells is regulated by TNF-α. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2008, 104, 2298–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, D.; Zhu, D.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Qian, L.; Niu, H.; Lu, Y.; Ren, G.; et al. Downregulation of reticulocalbin-1 differentially facilitates apoptosis and necroptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Science 2018, 109, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LU, L.; FU, N.; LUO, X.; LI, X.Y.; LI, X.P. Overexpression of cofilin 1 in prostate cancer and the corresponding clinical implications. Oncology Letters 2015, 9, 2757–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.F.; Chao, C.H.; Lin, L.Y.; Tsai, C.H.; Chou, C.; Lee, Y.J. Determination of urine cofilin-1 level in acute kidney injury using a high-throughput localized surface plasmon-coupled fluorescence biosensor. Journal of Biomedical Optics 2013, 19, 011004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakiris, I.; Soos, G.; Nemes, Z.; Kiss, S.S.; Andras, C.; Szantó, J.; Dezso, B. The presence of carboxypeptidase-M in tumour cells signifies epidermal growth factor receptor expression in lung adenocarcinomas: The coexistence predicts a poor prognosis regardless of EGFR levels. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 2007, 134, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiteren, K.; Hendriks, D.; Scharpé, S.; Lambeir, A.M. Carboxypeptidase M: Multiple alliances and unknown partners. Clinica Chimica Acta 2009, 399, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Jin, X.; Wang, K. Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis of Potential Biomarkers for Prostate Cancer. Pathology & Oncology Research 2017, 25, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karantza, V. Keratins in health and cancer: more than mere epithelial cell markers. Oncogene 2010, 30, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porten, S.P.; Wang, E.Y.; Vohra, P.; Carroll, P.R.; Jahanfard, S.; Kim, N.W. Evaluation of URO17® to improve non-invasive detection of bladder cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2024, 42, 176.e21–176.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, N.J.; Barquilha, C.N.; Barbosa, I.C.; Macedo, R.T.; Lima, F.O.; Justulin, L.A.; Barbosa, G.O.; Carvalho, H.F.; Felisbino, S.L. Syndecan Family Gene and Protein Expression and Their Prognostic Values for Prostate Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He Z, Tang F, L. Z.H.Y.L.H.L.Z.Z.G. Analysis of differentially expressed genes, clinical value and biological pathways in prostate cancer. America Journal of Translational Reseach 2028, 5, 1444–1456. [Google Scholar]

- Aykanli, E.; Arisan, S.; Arisan, E.D.; Yavuzsan, A.H. Diagnostic Value of GSTP1, RASSF1, AND RASSF2 Methylation in Serum of Prostate Cancer Patients. Urology Journal 2024, 20, 8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujicic, I.; Rusevski, A.; Stankov, O.; Popov, Z.; Dimovski, A.; Davalieva, K. Potential Role of Seven Proteomics Tissue Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Prostate Cancer in Urine. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesiadecki, M.; Mołoń, M.; Balawender, K.; Kobylińska, Z.; Galiniak, S. Shedding light on the shadows: oxidative stress and its pivotal role in prostate cancer progression. Frontiers in Oncology 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Xu, S.; Dhir, R.; Chandran, U.; O’Keefe, D.S.; Greenberg, N.M.; Gingrich, J.R. Hypoexpression and Epigenetic Regulation of Candidate Tumor Suppressor Gene CADM-2 in Human Prostate Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 2010, 16, 5390–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.A.; London, N.R.; Chen, H.; Park, K.W.; Sauvaget, D.; Stockton, R.A.; Wythe, J.D.; Suh, W.; Larrieu-Lahargue, F.; Mukouyama, Y.s.; et al. Robo4 stabilizes the vascular network by inhibiting pathologic angiogenesis and endothelial hyperpermeability. Nature Medicine 2008, 14, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, K.E.; Staikos, C.A.; Watson, K.L.; Moorehead, R.A. Loss of MXRA8 Delays Mammary Tumor Development and Impairs Metastasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 13730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvagni, F.; Nardi, F.; Spiga, O.; Trezza, A.; Tarticchio, G.; Pellicani, R.; Andreuzzi, E.; Caldi, E.; Toti, P.; Tosi, G.M.; et al. Dissecting the CD93-Multimerin 2 interaction involved in cell adhesion and migration of the activated endothelium. Matrix Biology 2017, 64, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| UNIPROT ID | Protein Name | Gene Name | HDs | PCa | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F8W111 | Carboxypeptidase M | CPM | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.00063 |

| O75882 | Attractin | ATRN | 5 (100%) | 1 (9%) | 0.0034 |

| A0A3B3ISU3 | Low affinity immunoglobulin gamma Fc region receptor III-B | FCGR3B | 5 (100%) | 2 (18%) | 0.012 |

| Q16651 | Prostasin | PRSS8 | 5 (100%) | 2 (18%) | 0.012 |

| Q8WZ75 | Roundabout homolog 4 | ROBO4 | 5 (100%) | 2 (18%) | 0.012 |

| Q9H8L6 | Multimerin-2 | MMRN2 | 5 (100%) | 2 (18%) | 0.012 |

| P19022 | Cadherin-2 | CDH2 | 5 (100%) | 2 (18%) | 0.012 |

| P05787 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 8 | KRT8 | 0 (0%) | 10 (91%) | 0.0034 |

| P25815 | Protein S100-P | S100P | 1 (20%) | 10 (91%) | 0.024 |

| A8MY60 | Leucine-rich repeat and IQ domain-containing protein 1 | LRRIQ1 | 0 (0%) | 9 (82%) | 0.012 |

| UNIPROT ID | Protein Name | Gene Name | LRPCa | HRPCa | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P19823 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | ITIH2 | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.034 |

| Q13018 | Secretory phospholipase A2 receptor | PLA2R1 | 4 (100%) | 1 (14%) | 0.034 |

| Q15293 | Reticulocalbin-1 | RCN1 | 0 (0%) | 6 (86%) | 0.034 |

| O94919 | Endonuclease domain-containing 1 protein | ENDOD1 | 0 (0%) | 6 (86%) | 0.034 |

| P11684 | Uteroglobin | SCGB1A1 | 1 (25%) | 7 (100%) | 0.047 |

| P08571 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | CD14 | 1 (25%) | 7 (100%) | 0.047 |

| P02750 | Leucine-rich alpha-2-glycoprotein | LRG1 | 1 (25%) | 7 (100%) | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).