Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

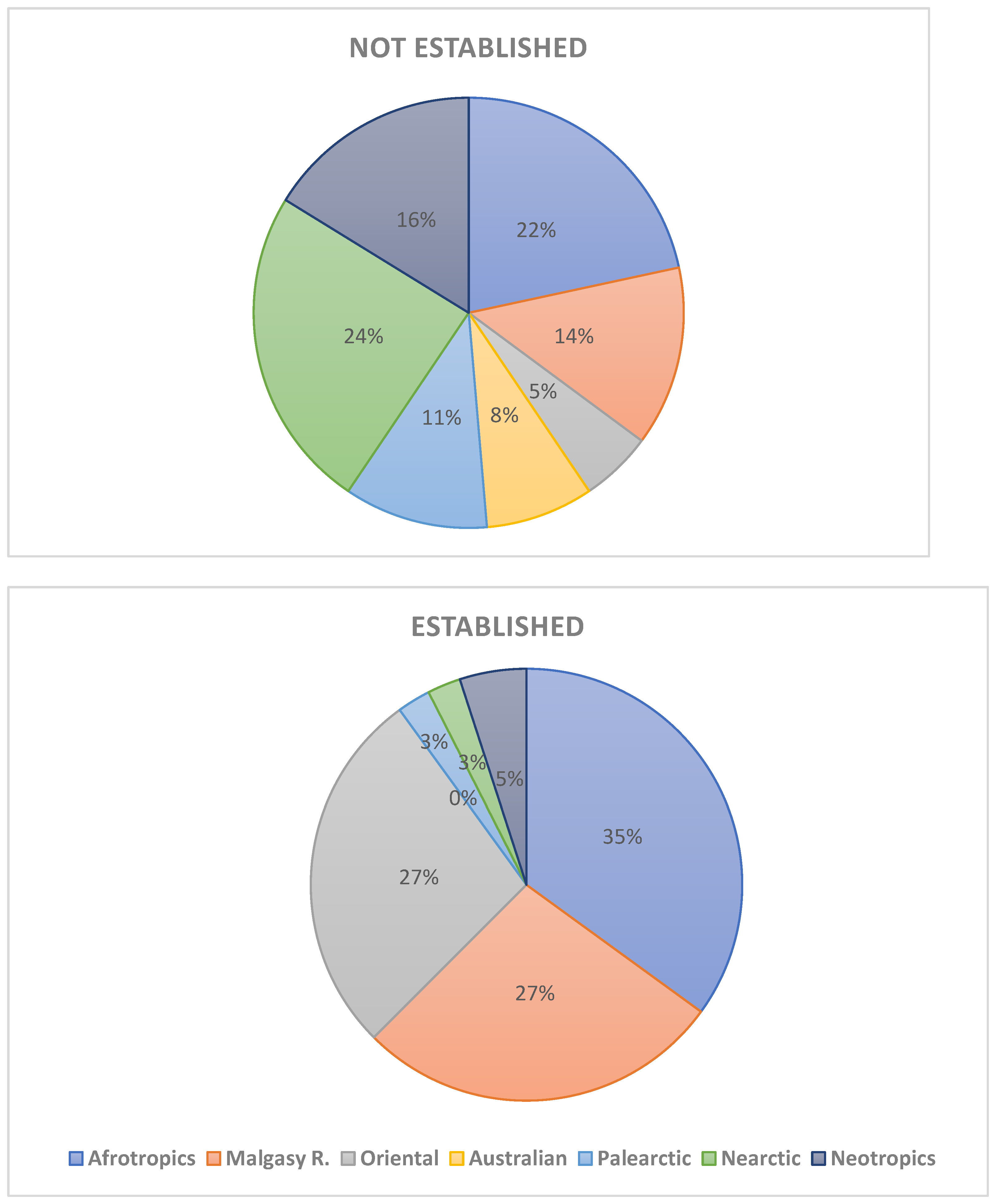

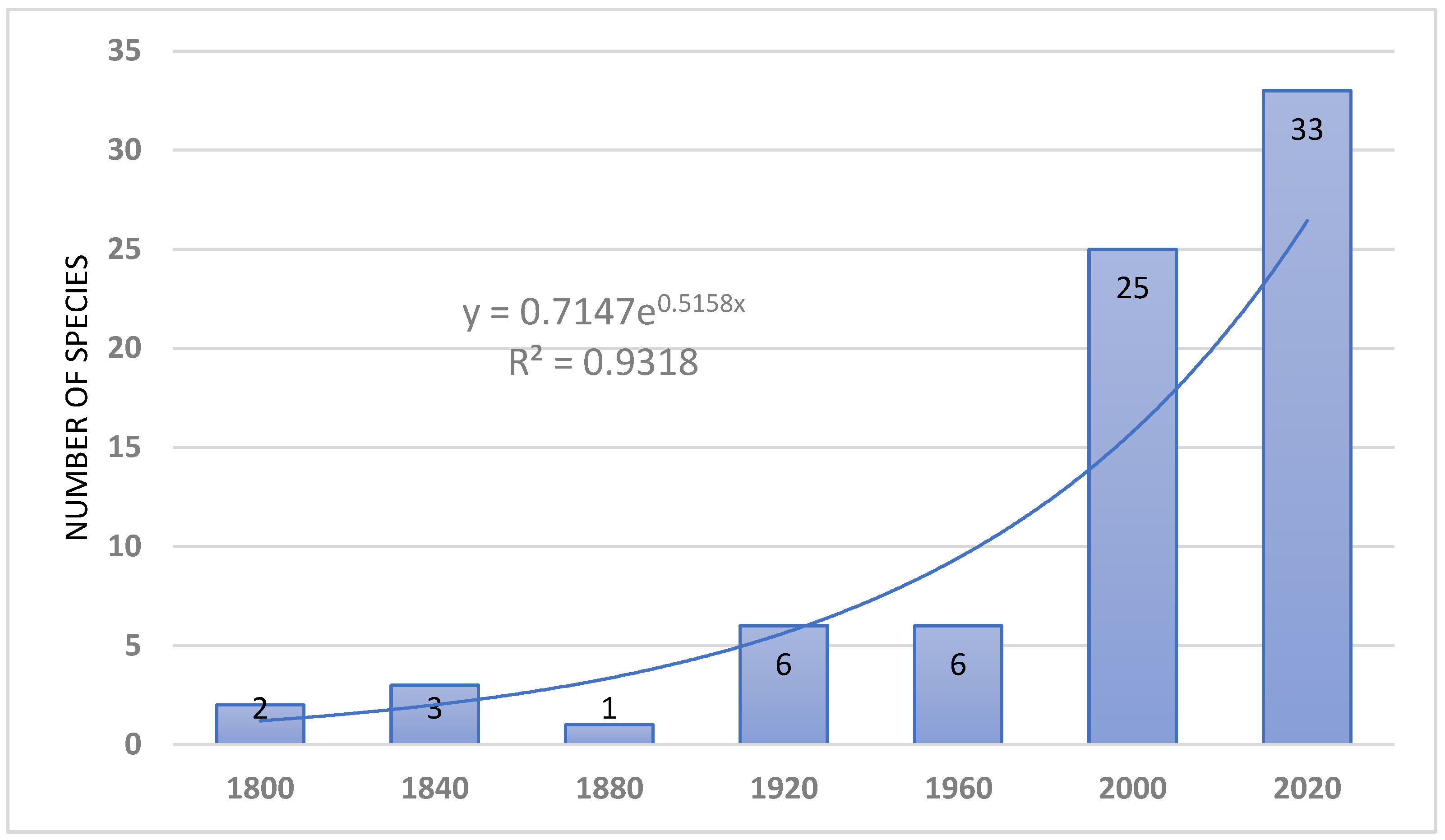

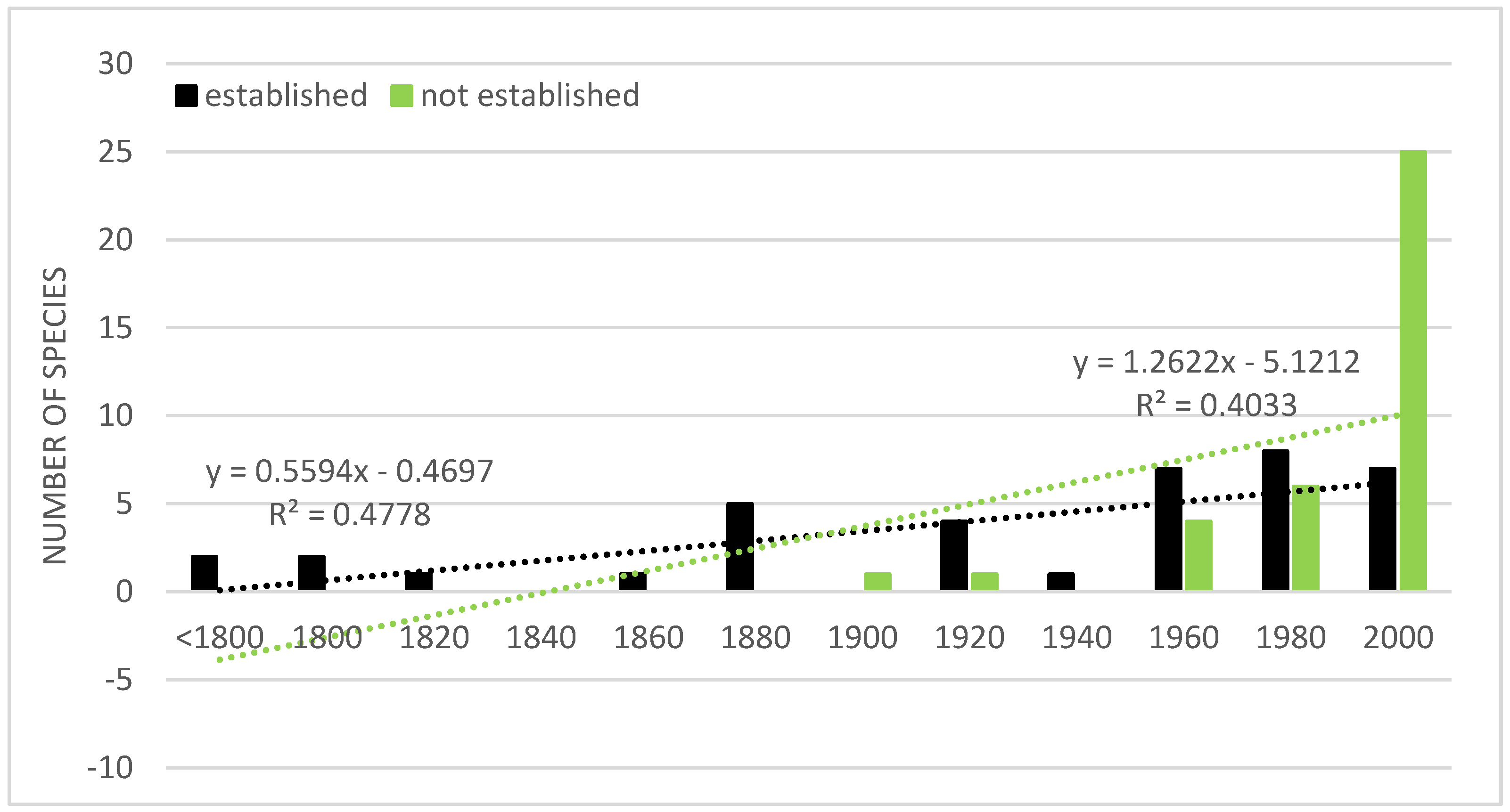

Introduction of species consists today one of the most important problem of nature conservation. Special attention is paid to alien vascular plants and vertebrates. In the Afrotropical Region (sub-Saharan Africa), avian and mammalian introductions have attracted the attention of many re-searchers and was recently reviewed, but there is a lack of such comprehensive review of alien amphibians and reptiles. The presented paper constitutes an attempt to overview the status, distribution, threats introduced herp species to sub-Saharan Africa since he second half of the 18th century. This review includes 21 amphibian (including 10 established) and 57 reptile (including 19 established) species introduced to sub-Saharan. The introduced amphibians are representatives of Urodela (n=4 spp., none established) and Anura (n=17 species, incl. 10 established). Introduced reptiles species belonged to the following orders: Testudines (n=11 species, incl. 6 established), Sauria (n=32 spp., incl. 29 established), Serpentes (n=13 spp., incl. 2 established) and Crocolylia (1 sp. not established). Most species introduced to sub-Saharan Africa which subsequently developed viable populations originated from the Afrotropical (35%), Malagasy (27%) and Oriental (27%) regions. However, the proportions of introduced species which failed to establish viable populations were quite different: Nearctics (25%), Afrotropics (22%), and Neotropics (17%); Malagasy 11%, Oriental Region only 6%. First introduction of alien herp species, i.e. Gehyra mutilate and Ptachadena mascareniensis, in Africa took place in 18th century. By the end of 19th century, four other species have been introduced and in the two last decades of that century – 5 species. Similarly, in 20th century, most introduction were made in the last two decades, when an exponential growth of introduction begun and lasts till present. This growth has been caused by an increase in international trade and herp pet industry, especially in South Africa. Stowaway and pet trade are the most common pathways of introductions. Few factors determine the successful establishment of introduced alien herp species in sub-Saharan Africa, viz.: the behavioural and morphological traits, propagula pressure, climate and habitat overlap, and presence of potentially competing species. The impact of alien herps in sub-Saharan Africa on the local biodiversity is not well-investigated. Negative effects have been, however, evidenced for species such as Sclerophrys gutturalis, Agama agama, Hemidactylus frenatus, Trachemys scripta (competition); Xenopus laevis, Sclerophrys gutturalis, Rhinella marina, Lycodon aulica (predation); Xenopus laevis, Python sabae (hybridization); Xenopus laevis, Palea steindachneri (diseases and parasites). In comparison with other continents (Europe and North America) the number of introduced and established herp species in sub-Saharan Africa is relatively low, possibly because the Afrotropical region is saturated with herps which can potentially compete and prey on the alien species, preventing their successful establishment. Madagascar, the Mascarenes and other small islands in the Malagasy Region have the highest number of introduced herp species in sub-Saharan Africa. However these numbers are still much lower than those recorded for instance in the Greater Caribbean, probably for the same reasons as in the mainland.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- introduced, but has not developed viable population;

- introduced and has developed viable population (usually with very restricted range);

- introduced and developed viable population, but then after declined and finally became extinct;

- introduced, developed viable population and is stable or expanding and may be invasive.

- not intentional (homoinscience) translocation; transportation of habitat or nursery materials, as accidentally transported contaminants of the horticultural trade, within consignments of wood, in construction materials, e.g. by stowaway, airplanes, camping vehicle (Douglas 1990);

- intentional (homoscience) translocation; e.g. by intentional release from a terrarium (Douglas 1990);

- relocation; done within the species range;

- repatriation: natural return to the abandoned areas of the former occurrence;

- reintroduction: return to the natural range with the help of human.

3. The Introduced Species

3.1. Species which have Developed Viable Populations and Expanding/Invasive

3.1.1. African Clawed Frog Xenopus laevis

3.1.2. Guttural Toad Sclerophrys gutturalis

3.1.3. Cane Toad Rhinella marina

3.1.4. Common Slider Trachemys scripta

3.1.5. Brahminy Blind Snake Indotyphlop braminus

3.1.6. Indian Wolf Snake Lycodon aulicus capucinus

3.1.7. Common Agama Agama agama

3.1.8. Green Tree Lizard Calotes versicolor

3.1.9. West Madagascan Clawless Gecko Ebenavia boettgeri

3.1.10. Common Mourning Gecko Lepidodactylus lugubris

3.1.11. Moorish Wall Gecko Tarentola mauritanica

3.1.12. Common Four-toed Gecko Gehyra mutilata

3.1.13. Day Geckos Phelsuma spp.

- Phelsuma borbonica agalegae from Mauritius has been probably introduced recently to Reunion.

- Phelsuma cepediana from Mauritius has been probably introduced to Rodriguez.

- Phelsuma grandis (Madagascar giant day gecko) from N Madagascar has been introduced to Reunion and Mauritus and also to Florida and Hawaii.

- Phelsuma dubia from W and N Madagascar has been probably introduced in the four major Comoro islands, Zanzibar Island, Mozambique Island (Mozambique), and small coastal areas of Tanzania and Kenya.

- Phelsuma laticauda laticauda has been introduced or presumably introduced to the Comoro islands Mayotte and Anjouan, the southern Seychelles Islands, Farquhar, Cerf, and Providence, the Mascarene Island, Réunion and Mauritius, French Polynesia, Florida.

3.1.14. House Geckos Hemidactylus spp.

- H. mabouia. Native to Central and East Africa, extending south into the northeast of South Africa. Populations of H. mabouia species have invaded West Africa, Reunion and Mauritius in the mid-1990s and to Florida (USA) and Hawaii, the Caribbean, South America and Florida. Invasions have resulted in displacement of native geckos in Florida and Curaçao (Meshake et al. 2022).

- H. frenatus. Native to Southeast Asia, spread via ships and cargo; introduced to Hawaii, Australia, the Americas, and islands globally.

- H. turcicus. From the Mediterranean. Introduced to many parts of the world, with similar urban settings.

- H. granotii. Indo-Pacific species. Introduced to Seychelles, New Zealand, Hawaii, Fiji, the Bahamas, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Colombia, and tropical United States (Hawaii, Florida, Georgia, Texas and California).

- H. brooki. The geographical range of this species remains controversial and depends on the definition of. Traditionally regarded as native to sub-Saharan Africa. Introduced to small islands in the Malagasy Region.

3.2. Species which have Developed Viable Population but are not Expanding/invasive

3.2.1. Frogs

3.2.2. Tortoises

3.2.3. Chameleons

3.2.4. Skinks

3.2.5. Geckos

3.3. Species which Failed to Develop Viable Populations

| Taxa | In the world | Established | Not establ. | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | %ar | n | %ar | n | %w | |

| AMPHIBIA | 8973 | 10 | 26.32 | 11 | 57.89 | 21 | 0.23 |

| Caudata | 836 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 21.05 | 4 | 0.48 |

| Salamandridae | 147 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 15.79 | 3 | 2.04 |

| Ambystomatidae | 32 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 5.26 | 1 | 3.13 |

| Anura | 7 917 | 10 | 26.32 | 7 | 36.84 | 17 | 0.14 |

| Pipidae | 41 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Bufonidae | 666 | 4 | 10.53 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.03 |

| Rhacophoridae | 462 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Hyperoliidae | 236 | 2 | 5.26 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Ptychadenidae | 63 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Pyxicephalidae | 91 | 1 | 2.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Ceratophryidae | 12 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 5.26 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Microhylidae | 764 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 5.26 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Hylidae | 762 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 10.53 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Dendrobatidae | 213 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 15.79 | 3 | 0.02 |

| REPTILIA | 12502 | 38 | 100.00 | 19 | 100.00 | 57 | 0.46 |

| Testudines | 366 | 6 | 14.63 | 5 | 13.89 | 11 | 0.09 |

| Emyidae | 58 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Testudinidae | 47 | 3 | 7.32 | 2 | 5.56 | 5 | 0.04 |

| Chelydridae | 5 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Trionychidae | 36 | 3 | 7.32 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 0.02 |

| Pelomedusidae | 27 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Sauria | 7905 | 29 | 70.73 | 3 | 8.33 | 32 | 0.26 |

| Agamidae | 604 | 1 | 2.44 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Chamaeleonidae | 234 | 6 | 14.63 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.05 |

| Iguanidae | 45 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Gekkonidae | 1713 | 22 | 53.66 | 0 | 0.00 | 22 | 0.18 |

| Scincidae | 1793 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Serpentes | 4203 | 2 | 4.88 | 11 | 30.56 | 13 | 0.10 |

| Pythonidae | 40 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Colubridae | 2167 | 1 | 2.44 | 7 | 19.44 | 7 | 0.06 |

| Lamprophiidae | 93 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 5.56 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Viperidae | 406 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Typhlopidae | 425 | 1 | 2.44 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Crocodylia | 27 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Crocodylidae | 17 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 2.78 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Total | 21475 | 41 | 100.00 | 36 | 100.00 | 77 | 0.62 |

4. Places of Introductions

5. Timing of Introduction

6. Pathways of Introduction

6.1. Stowaways

6.2. Pet Trade

6.3. Leading-edge (jump) Dispersal

6.4. Cultivation Dispersal

| Way of introduction | Amphibians | Reptiles | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| est. | not est. | est. | not est. | est. | not est. | |

| Pet released | 0 | 12 | 5 | 18 | 5 | 30 |

| Unintentional translocation | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Intentional translocation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Stowaway | 0 | 3 | 18 | 3 | 18 | 6 |

| Biological control | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 3 | 17 | 29 | 28 | 32 | 45 |

7. Factors Determining Introduction Success

7.1. Behavioural and Morphological traits

7.2. Propagule Pressure

7.3. Climate and Habitat Overlap

7.4. Presence of Potentially Competing Species

8. Impacts of Introduced Amphibians and Reptiles on Local Fauna

8.1. Competition

8.2. Predation

8.3. Hybridization

8.4. Transmission of New Diseases and Parasites

9. Comparison with Other Regions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Scientific name | Common name | Family | Natural range | Inas. | Place and date of introduction | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPHIBIANS | ||||||

| Cynops pyrrhogaster | Japanese fire-bellied newt | Salamandri-dae | Japan | 3 | South Africa: KwaZulu-Natal, Cape Town, 2016 | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Triturus cristatus | crested newt | Salamandri-dae | Europe | 3 | South Africa, 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Notophthalmus viridescens | eastern newt | Salamandri-dae | E North America | 3 | South Africa: W. Cape, 2010’s; a pet | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Ambystoma mexicanum | axolotl | Ambystomatidae | Mexico | 4 | South Africa: Bloemfontein, 1980’s, now extinct | Van Rensburg et al. 2011 |

|

Xenopus laevis |

African clawed frog | Pipidae | Africa | 1 | South Africa (W Cape), 1908’s | De Moor & Bruton 1988 |

| Sclerophrys gutturalis | African common toad | Bufonidae | Southern Africa | 1 | Reunion (1927), Mauritius (1922); South Africa: Cape Town (2000); Kenya: Nairobi (2025) |

Starmühlner 1979 De Villiers 2006 Telford et al. 2019 |

| Rhinella marina | cane toad | Bufonidae | Neotropics | 1 | Mauritius; two cases of introduction, 1936-1938 | Lever 2003 |

| Schismaderma carens | African red toad | Bufonidae | S and E Africa | 2 | SA: Cape Town’ stowaway, 2013; regularly transported in luggage, although records are scarce | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Duttaphrynus melanostictus | Asian common toad | Bufonidae | SE Asia | 2 | South Africa: W. Cape: Tokai, Bellville, 2012; Tomasina (Madagascar), 2015 | Measey et al. 2017 Moore et a. 2015 |

| Chiromantis xerampelina | grey foam-nest tree frog | Rhacophoridae | S and E Africa | 2 | South Africa: Stellenbosch, Porterville, Victoria West, 2012 |

Measey et al. 2017 |

| Hyperolius marmoratus | painted reed frog | Hyperliidae | Mozambique, Malawi, SA | 2 | South Africa: W. Cape: Villiersdorp (1997) and Cape Town (2004) | Davis et al. 2013 |

| Hyperolius tuberilinguis | tinker reed frog | Hyperolidae | S and E Africa | 2 | South Africa: Cape Town, Bloemfontein, 2009; jump dispersal | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Ptychadena mascareniensis | Mascarene grass frog | Ptychadeni-dae | Mascarenes | 2 | Reunion (before 1790) Seychelles, 2010’s; Madagascar? |

Betting de Lancastel 1827, Labisko et al., 2015; Williams et al. 2020 |

| Pyxicephalus adspersus | African bull frog | Pyxicephalidae | S Africa | 2 | South Africa: Cape Peninsula: Muizenberg Mountains, 1980’s | de Moor and Bruton 1988 |

| Ceratophrys ornata | Argentine horned frog | Ceratophryidae | Argentina | 3 | South Africa, c. 2008/2009 | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Dyscophus antongilii | Madagascar tomato frog | Microhylidae | Madagascar | 3 | South Africa: Transvaal Snake Park, 1990’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Dendrobates leucomelas | yellow-banded poison dart frog | Dendrobati-dae | N South America | 3 | South Africa: Johannesburg: Montecasino Bird Gardens; 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Dendrobates auratus | green-and-black poison dart frog | Dendrobati-dae | Central America | 3 | South Africa: Johannesburg: Montecasino Bird Gardens; uShaka; Two Oceans, 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Dendrobates tinctorius | dyeing poison dart frog | Dendrobati-dae | N South America | 3 | South Africa: Johannesburg: Montecasino Bird Gardens, 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Litoria albolabris | Wandolleck's white-lipped tree frog | Hylidae | New Guinea | 3 | South Africa, 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| Litoria caerulea | Australian green tree frog | Hylidae | Australia | 3 | South Africa, 2010’s | Measey et al. 2017 |

| REPRILES | ||||||

| Crocodylus niloticus | Nile crocodile | Crocodylidae | Africa | 3 | South Africa, 1960’s | Douglas 1996 |

| Macrochyles temmincki | alligator snapper turtle | Chelydridae | USA | 4 | South Africa: George, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Palea steindachneri | wattle-necked softshell turtle | Trionychidae | China, Laos Vietnam | 2 | Mautitius, c. 1990 Reunion, SA |

Iverson 1992 King & Burke 1989 |

| Amyda cartilaginea | Sunda softshell turtle | Trionychidae | Oceania | 2 | Mauritius, 1980’s | Owadally & Lambert 1988 |

| Trachemys scripta | common slider | Trionychidae | E USA | 1 | South Africa: Pretoria/Johannesburg and Durban areas; Reunion, Seychelles, 1990’s; Kenya: Nairobi | Douglas 1997 Rhodin et al. 2011 |

| Pelusios subniger | East African black mud turtle | Pelomedusidae | E Africa | 4 | Mauritius; Seychelles; 1970’s; now extinct | Wermuth & Mertens 1977 |

| Emys orbicularis | European pond turtle | Emyidae | Europe | 3 | South Africa (E Cape), 1990’s? | Douglas 1996 |

| Geochelone platynota | Burmese star tortoise | Testudinidae | SE Asia | 4 | Kenya, failed to establish viable population, now extinct | Douglas 1996 |

| Astrochelys radiata | radiated tortoise | Testudinidae | S Madagascar | 2 | Mauritius (Rodrigues, Round Island), Reunion; 1980’s; Rodrigues, 2006 | Owadally & Lambert 1988; Griffiths et al. 2013 |

| Astrochelys yniphora | Madagascar spur tortoise | Testudinidae | NW Madagascar | 2 | Mauritius, 2010’s? | Rhodin et al. 2017 |

| Geochelone pardalis | leopard tortoise | Testudinidae | Africa | 2 | South Africa, 1960’s? | Douglas 1996 |

| Aldabrachelys gigantea | Aldabra giant tortoise | Testidinidae | Seychelles | Rodrigues, 2006 | Griffiths et al. 2013 | |

| Indotyphlops braminus | Brahminy blind snake | Typhlopidae | SE Asia | 1 | Tanzania; Durban, SA: Cape Town, 1920’s; Reunion, beg. 19th cen.?; Mauritius; Seychelles; Annobon, 2003 | Douglas 1996, Maillard 1862, Guibe 1958; Williams et al. 2020 Jesus et al. 2003 |

| Python molurus bivittatus | Burmese python | Pythonidae | SE Asia | 4 | Cape Town, 2000’s; escapee, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Boa constrictor | Boa constrictors | Boidae | South America | 4 | South Africa, now extinct, 2000’s | Booth et al. 2012, 2016 |

| Lycodon aulicus | Indian wolf snake | Colubridae | India | 1 | Reunion, beg. 19th cen.?; Mauritius (1879) | Duméril et al. 1854 Daruty de Grandpré 1883 |

| Lampropeltis californiae | Californian king snake | Colubridae | North America | 4 | South Africa, escapee, now extinct, 2000’s | Booth et al. 2012, 2016 |

| Lampropeltis triangullum | Sinaloan king snake | Colubridae | North America | 4 | South Africa, escapee, now extinct, 2000’s | Booth et al. 2012, 2016 |

| Lampropeltis alterna | gray-banded kingsnake | Colubridae | Mexico | 4 | South Africa: Strand, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Pantherophis guttatus | red corn snakes | Colubridae | SE USA | 4 | South Africa: Durban, Johannesburg, Cape Town, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Elaphe obsoleta spiloides | grey rat snake | Colubridae | E and C USA | 4 | South Africa: Durban, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Elaphe obsoleta quadrivittata | yellow rat snake | Colubridae | USA | 4 | South Africa: Cape Town, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Pituophis m. melanoleucus | northern pine snake | Colubridae | SE USA | 4 | South Africa: Durban, 2000’s; now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Lamprophis inornatus | olive snake | Lamprophi-idae | Africa | 3 | South Africa, 2000’s | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Lamprophis fuliginosus | brown house snake | Lamprophi-idae | Africa | 3 | South Africa, 2000’s | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Crotalus atrox | western diamond-backed rattlesnake | Viperidae | SW USA, N Mexico | 4 | South Africa: Gauteng, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Furcifer pardalis | panther chameleon | Chamaeleonidae | Madagascar | 2 | Reunion (before 1830) | Mertes 1966, Cuvier 1829 |

| Bradypodion pumilum | Cape dwarf chameleon | Chamaeleonidae | Africa | 3 | Namibia, 1990’s: Swakopmund and Walvis Bay; also Luderitz, Windhoek, now extinct | Irish 2025 |

| Calumna parsonii | green giant chameleon | Chemeleontidae | E Madagascar | 3 | Mauritius, 1960’s | Mertes 1966 |

| Chamaeleo quilensis | Flap-necked chameleon | Chemeleontidae | South Africa: KZN | 3 | South Africa: Free State (before 1978) | Douglas 1997; Kopij & Bates 1997 |

| Bradypodion spp. | dwarf chameleon | Chemeleontidae | South Africa: KZN | 3 | South Africa: Free State (1939) | Douglas 19960, 1997; Kopij & Bates 1997 |

| Cryptoblepharus boutoni | Bouton’s snake-eyed skink | Scincidae | Easter coast of Africa | 3 | South Africa: KZN (natural translocation); 1990’s | Douglas 1996 |

| Iguana iguana | green iguana | Iguanidae | Neotropics | 4 | South Africa: Gauteng, 2000’s, now extinct | Van Wilgen 2008 |

| Agama agama | common agama | Agamidae | E Africa | 1 | Reunion (before 1995) Comoro Isl. (1997) Madagascar (2004) |

Guillermet et al. 1998, Meirte 2004 Wagner et al. 2009 |

| Pogona vitticeps | Bearded dragons | Agamidae | Australia | 4 | South Africa, 2000’s, now extinct | Booth et al. 2012, -16 |

| Calotes versicolor | green tree lizard | Agamidae | Indonesia | 1 | Reunion 1865; Rodrigues, Mauritius Seychelles Keyna, end of 20th cen., Nairobi (1920) |

Vinson 1870 Matyot 2004 iNaturalist |

| Gehyra mutilata | common four-clawed gecko | Gekkonidae | SE Asia | 1 | Reunion, 18th cen.?; seaway; Mauritius, Rodrigues, Seychelles |

Bory de St. Vincent 1804; Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

| Phelsuma laticauda | flat-tailed day gecko | Gekkonidae | N Madagascar | 1 | Reunion, 1975; TRL; Mauritius, Mayotte, Comoros, Seychelles | Glaw & Rösler 2015 Moutou 1995 |

| Phelsuma astriata | Seychelles day gecko | Gekkonidae | Seychelles | 1 | Reunion, before 2003; unknown | Mozzi et al. 2005; Gardner 1988 |

| Phelsuma grandis | Madagascar giant day gecko | Gekkonidae | N Madagascar | 1 | Reunion 1994, Mauritius, 1990’s | Glaw & Rösler 2015; Probst 1997; Sanchez & Probst 2014 |

| Phelsuma lineata | lined day gecko | Gekkonidae | Madagascar | 1 | Reunion, 1940; TRL | Cheke (1975) |

| Phelsuma mad-agascariensis | Madagascan day gecko | Gekkonidae | Madagascar | 1 | Reunion, mid.1990’s; Mauritius; translocation? | Buckland et al. 2014 |

| Tarentola mauritanica | Moorish wall gecko | Gekkonidae | Mediterranean Region | 1 | S Western Shara; 1970’s, | Salvador & Peris 1975 |

| Lepidodactylus lugubris | common mourning gecko | Gekkonidae | Indo-Pacific | 1 | Seychelles, Rodrigues; 1960’s, Mauritius | Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

| Lygodactylus capensis | Cape dwarf gecko | Gekkonidae | S, E Africa | 2 | Central Africa, 1956; Tanzania: Pemba; Free State (before 1978) | Measey et al. 2017 Kopij & Bates 1997 |

| Pachydactylus bibronii | Bibron’s gecko | Gekkonidae | South Africa: KZN | 2 | Free State (before 1978) | Douglas 1997; Kopij & Bates 1997 |

| Ebenavia boettgeri | west Madagascan clawless gecko | Gekkonidae | E Madagascar | 1 | Mauritius; 1960’s | Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

| Hemidactylus mercatorius | Farquhar half-toed gecko | Gekkonidae | Madagascar Mozambique, Seychelles | 1 | Cape Verde (Santo Antao, Sao Vincente), Comoro Islands, Europa Is., Reunion, Mauritius, Rodrigues, Mayotte; 1960? | Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

|

Hemidactylus mabouia |

tropical house gecko | Gekkonidae | W and C Africa | 1 | Principe, Sao Tome, 1884; Bazaruto Arch. (Down 1999, J. Biog.); Free State (before 1978);Simon’s Town, 1962; Gordon’s Bay, 1976 East London and Port Elizabeth, | Greeff 1884 Weterings & Vetter 2018; Douglas 1992; Brooke et al. 1986; Rebelo et al. 2019 |

|

Hemidactylus longicephalus |

long-head half-toed gecko | Gekkonidae | C, W Africa | 1 | Principe, Sao Tome, 1892 | Bedriaga 1892 |

| Hemidactylus flaviviridis | northern house gecko | Gekkonidae | SE Asia | 1 | Socotra, end of 19th cen.?; only known from Hadiboh town and outskirts | Blanford 1881a |

| Hemidactylus robustus | Heyden’s gecko | Gekkonidae | SW Asia, Horn of Africa | 1 | Socotra, end of 19th cen. | Boulenger 1903 |

| Hemidactylus homoeolepis | Arabian leaf-toed gecko | Gekkonidae | S Arabian Peninsula | 1 | Socotra, 1990’s | Joger 2000 |

| Hemidactylus frenatus | common house gecko | Gekkonidae | India, Sri Lanka | 1 | Reunion (19th cen.), Mauritius, Rodriguez, Seychelles, Comoros, Madagascar, SA, Somalia | Vinson & Vinson 1969, Maillard 1862 |

| Hemidactylus mercatorius | Farquhar half-toed gecko | Gekkonidae | Madagascar | 2 | Reunion, 2000?; seaway? | Sanchez et al. 2012 |

| Hemidactylus parvimaculatus | small spotted house gecko | Gekkonidae | S India, Sri Lanka | 2 | Mauritius, Reunion, Rodrigues, Comoro; end of 19th century; Seychelles | Bauer et al. 2010, Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

| Hemiphylodacty-lus typus | Indo-Pacific slender gecko | Gekkonidae | SE Asia | 2 | Reunion, 1960’s?; Mauritius, Rodrigues, Comoro Isl. (Moheli) |

Vinson & Vinson 1969 |

| Afrogecko porphyreus | marbled leaf-toed gecko | Gekkonidae | South Africa | 2 | South Africa: Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, 2010’s | Rebelo et al. 2019 |

References

- AmphibiaWeb. University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA; Available online: https://amphibiaweb.org (accessed on 15 Dec 2025).

- Andreone, F.; Carpenter, A.I.; Crottini, A.; et al. Amphibian conservation in Madagascar: old and novel threats to a peculiar fauna. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- ANMH. Amphibian Species of the World 6.2, an Online Reference. American Museum of Natural History. Available online: https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- ISSG. Global Invasive Species Database (GISD); Invasive Species Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, 2011; Available online: http://www.issg.org/database.

- Bauer, A.M.; Jackman, T.; Greenbaum, E.; Papenfuss, T.J. Confirmation of the occurrence of Hemidactylus robustus Heyden, 1827 (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) in Iran and Pakistan. Zoöl. Middle East 2006, 39, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceríaco, L.M.P.; Marques, M.P.; Bell, R.C.; Bauer.

- Bedriaga, J. Note sur les amphibiens et reptiles recueillis par M. Adolphe Moller aux îles de la Guinée. O Instituto 1892, 39, 498–507, 642–648, 736–742, 814–820, 901–907. [Google Scholar]

- Betting de Lancastel, M.E.M. Statistique de l’île Bourbon. Présenté en exécution de l’article 104s28 de l’Ordonnance royale du 21 août 1825; La Huppe, Imprimerie du Gouvernement: Saint-Denis, La Réunion, 1827. [Google Scholar]

- Blanford, W.T. Notes on the lizards collected in Socotra by Prof. I. Bayley Balfour. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1881, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, M.; Collen, B.; Baillie, J.E.; Bowles, P.; Chanson, J.; Cox, N.; Hammerson, G.; Hoffmann, M.; Livingstone, S.R.; Ram, M.; et al. The conservation status of the world’s reptiles. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 157, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borroto-Páez, R.; Bosch, R.A.; Fabres, B.A.; García, O.A. Introduced amphibians and reptiles in the Cuban archipelago. Herpetological Conservation & Biology 2015, 10(3), 985–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Bory de Saint-Vincent, J.-B.G.M. Voyage dans les quatre principales îles des mers d’Afrique, Ténériffe, Maurice, Bourbon et Sainte-Hélène. F. Buisson, Paris, France. 3 volumes + atlas; 1804. [Google Scholar]

- Boulenger, G.A. Reptiles. In The natural history of Sokotra and Abd-el-Kuri; Forbes, H.O., Ed.; Liverpool- the free public Museum Henry Young & Sons publ.: London, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, R.K.; Lloyd, P.H.; de Villiers, A.L.; Macdonald, eds I.A.W.; Kruger, F.J.; Ferrar, A.A. Alien and translocated terrestrial vertebrates in South Africa. In The Ecology and Management of Biological Invasions in Southern Africa; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, 1986; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Buckland, S.; Cole, N.C.; Aguirre-Gutiérrez, J.; Gallagher, L.E.; Henshaw, S.M.; Besnard, A.; Tucker, R.M.; Bachraz, V.; Ruhomaun, K.; Harris, S. Ecological Effects of the Invasive Giant Madagascar Day Gecko on Endemic Mauritian Geckos: Applications of Binomial-Mixture and Species Distribution Models. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e88798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capinha, C.; Seebens, H.; Cassey, P.; García-Díaz, P.; Lenzner, B.; Mang, T.; Moser, D.; Pyšek, P.; Rödder, D.; Scalera, R.; et al. Diversity, biogeography and the global flows of alien amphibians and reptiles. Divers. Distrib. 2017, 23, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Carpenter, A.; Rowcliffe, J.M.; Watkinson, A.R. The dynamics of the global trade in chameleons. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 120, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza, S.; Arnold, E.N.; Mateo, J.A.; López-Jurado, L.F. Parallel gigantism and complex colonization patterns in the Cape Verde scincid lizards Mabuya and Macroscincus (Reptilia: Scincidae) revealed by mitochondrial DNA sequences. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, T.J.; Bolger, D.T. The role of introduced species in shaping the abundance and distribution of island reptiles. Evolutionary Ecology 1991a, 5, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, T.J.; Bolger, D.T. The role of interspecific competition in the biogeography of island lizards. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1991, 6, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtles on the Brink in Madagascar: Proceedings of Two Workshops on the Status, Conservation, and Biology of Malagasy Tortoises and Freshwater Turtles. In Chelonian Research Monographs No. 6; Castellano, C.M., Rhodin, A.G.J., Ogle, M., Mittermeier, R.A., Randriamahazo, H., Hudson, R., Lewis, R.E., Eds.; 2013; p. 184 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A.S. Un lézard malgache introduit à La Réunion. Inf.-Nat. 1975, 13, 94–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A.S. An ecological history of the Mascarene Islands, with particular reference to extinctions and introductions of land vertebrates. In Studies of Mascarene Island Birds; Diamond, A.W., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; pp. Pp. 5–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cheke, A.S.; Hume, L. Lost Land of the Dodo. An Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues; Poyser, T. & AD., Ed.; London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cuvier, G.J.L.N.F.D. Le Règne Animal Distribué, d'après son Organisation, pour servir de base à l'Histoire naturelle des Animaux et d'introduction à l'Anatomie Comparé. Nouvelle Edition; Les Reptiles. Edition Déterville: Paris, France, 1829; Vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M.A. Invasion biology; Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deso, G.; Renet, J.; Gomez, M.-G.; Prio, P.; Capoulade, F.; Geoffroy, D.; Duguet, R.; Rato, C. Documenting the introduction of the Moorish gecko Tarentola mauritanica (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Phyllodactylidae) on the Levant and Port-Cros Islands (Hyères Archipelago, Var department, France). Herpetology Notes 2020, 13, 809–812. [Google Scholar]

- Daruty de Grandpré, C. Rapport annuel du Secrétaire. 5 Février 1879. Transactions de la Société Royale des Arts et Sciences de Maurice, Nouvelle 1883, 12, 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- Das, I.; Charles, J.K.; Edwards, D.S. Calotes versicolor (Squamata: Agamidae)-A New Invasive Squamate for Borneo. Curr. Herpetol. 2008, 27, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Clusella-Trullas, S.; Hui, C.; McGeoch, M.A. Farm dams facilitate amphibian invasion: Extra-limital range expansion of the painted reed frog in South Africa. Austral Ecol. 2013, 38, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; McGeoch, M.A.; Clusella-Trullas, S. Plasticity of thermal tolerance and metabolism but not water loss in an invasive reed frog. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A: Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2015, 189, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Hill, M.P.; McGeoch, M.A.; Clusella-Trullas, S. Niche shift and resource supplementation facilitate an amphibian range expansion. Divers. Distrib. 2018, 25, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, F.A.; de Kock, M.; Measey, G.J. Controlling the African clawed frog Xenopus laevis to conserve the Cape platanna Xenopus gilli in South Africa. Conservation Evidence 2016, 13, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, R.M. Incidences of homoscience and homoinscience translocation in the Orange Free State. J. Herpetol. Assoc. Afr. 1990, 37, 55–56. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, R.M. The genera Bradypodion and Chamaeleo in the Orange Free State. J. Herpetol. Assoc. Afr. 1992, 40, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, R.M. 1996.

- Douglas, R.M. 1997.

- Duméril, A.M.C.; Bibron, G.; Duméril, A. Erpétologie générale ou histoire naturelle complète des Reptiles. Tome 7(1); Edition Roret: Paris, France, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Enge, K.M.; Kryśko, K.L.; Talley, B.L. Distribution and ecology of the introduced African rainbow lizard, Agama agama africana (Sauria: Agamidae), in Florida. Florida Scientist 2004, 67, 303–310. [Google Scholar]

- Filz, K.J.; Bohr, A.; Lötters, S. Abandoned Foreigners: is the stage set for exotic pet reptiles to invade Central Europe? Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 27, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficetola, G.F.; Rödder, D.; Padoa-Schioppa, E. Trachemys scripta (Slider terrapin). Handbook of global freshwater invasive species 2012, 331–339. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, A.S. Day geckos of the genus Phelsuma in the outer Seychelles. Biol. Soc. Washintgton 1988, 8, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Glaw, F.; Rösler, H. Taxonomic checklist of the day geckos of the genera Phelsuma GRAY, 1825 and Rhoptropella HEWITT, 1937 (Squamata: Gekkonidae). Vertebr. Zoöl. 2015, 65, 247–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeff, R. Ueber die Fauna der Guinea-Inseln S. Thomé und Rolas. Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft zur Beförderung der gesammten Naturwissenschaften zu Marburg 1884, 2, 41–80 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, O.; Andre, A.; Meunier.

- Guillermet, C.; Couteyen, S.; Probst, J.-M. Une nouvelle espèce de reptile naturalisée à La Réunion, l’Agame des colons Agama agama (Linnaeus). Bull. Phaethon 1998, 8, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Díaz-Paniagua, C.; Ribas, A.; Florencio, M.; Pérez-Santigosa, N.; Casanova, J. Helminth communities of the exotic introduced turtle, Trachemys scripta elegans in southwestern Spain: Transmission from native turtles. Res. Veter- Sci. 2009, 86, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Martínez-Silvestre, A.; Pérez-Santigosa, N.; León-Vizcaíno, L.; Díaz-Paniagua, C. High prevalence of diseases in two invasive populations of red-eared sliders (Trachemys scripta elegans) in southwestern Spain. Amphibia-Reptilia 2020, 41, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, J. Namibia Biodiversity Database Web Site. Page: Bradypodion pumilum (Gmelin 1789) in Namibia. Interpretive collation based on the combined published sources for all included taxa, as listed, 2025. Available online: https://biodiversity.org.na/taxondisplay.php?nr=2708.

- ISSG. Global Invasive Species Database (GISD); Invasive Species Specialist Group of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, 2011; Available online: http://www.issg.org/database.

- McCoy, C.J.; Iverson, J.B. A Checklist with Distribution Maps of the Turtles of the World. Copeia 1987, 1987, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, D.; Naumov, B.Y.; Pule, A.N. First Record of the Moorish Gecko Tarentola mauritanica (Linnaeus, 1758) (Squamata: Phyllodactylidae) for Bulgaria. Acta Zool. Bulg. 2022, 74(1), 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T.J.; Auliya, M.; Burgess, N.D.; Aust, P.W.; Pertoldi, C.; Strand, J. Exploring the international trade in African snakes not listed on CITES: highlighting the role of the internet and social media. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.; Brehm, A.; Harris, D.J. Relationships of Tarentola (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) from the Cape Verde Islands estimated from DNA sequence data. Amphibia-Reptilia 2002, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, J.; Brehm, A.; Harris, J. The herpetofauna of Annobón island, Gulf of Guinea, West Africa. Herpetological Bulletin 2003, 86, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Joger, U. The reptile fauna of the Soqotra Archipelago. In Isolated vertebrate communities in the tropics. Bonn Zoological Monographs; Rheinwald, G., Ed.; 2000; Volume 46, pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Kark, S.; Solarz, W.; Chiron, F.; Clergeau, P.; Shirley, S. Alien Birds, Amphibians and Reptiles of Europe. In The Handbook of Alien Species in Europe; Springer Science, Business Media B.V., 2008; pp. 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Crocodilian, tuatara, and turtle species of the world. A taxonomic and geographic reference; King, F.W., Burke, R.L., Eds.; Association of Systematics Collections: Washington, D.C., 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kolby, J.E.; Smith, K.M.; Berger, L.; Karesh, W.B.; Preston, A.; Pessier, A.P.; Skerratt, L.F. First Evidence of Amphibian Chytrid Fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) and Ranavirus in Hong Kong Amphibian Trade. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e90750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopij, G. Alien Birds in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview. Conservation 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Alien Mammals in the Afrotropical Region and Their Impact on Vertebrate Biodiversity: A Review. Diversity 2025, 17, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G.; Bates, M.F. Reptiles and amphibians of Bloemfontein. Kovshaan 1997, 17, 17–23. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318461686_Herpetofauna_of_Bloemfontein.

- Kraus, F. Invasion pathways for terrestrial vertebrates. In Invasive species: vectors and management strategies; Carlton, J., Ruiz, G., Mack, R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, D. C., 2003; pp. 68–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, F. Alien Reptiles and Amphibians – a Scientific Compendium and Analysis; Springer Verlag: Heidelberg - New York, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kryśko, K.L.; Burgess, J.P.; Rochford, M.R.; et al. Verified non-indigenous amphibians and rep tiles in Florida from 1863 through2010: Outlining the invasion process and identifying invasionpathways and stages. Zootaxa 2011, 3028, 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Krysko, K.L.; Somma, L.A.; Smith, D.C.; Gillette, C.R.; Cueva, D.; Wasilewski, J.A.; Enge, K.M.; Johnson, S.A.; Campbell, T.S.; Edwards, J.R.; et al. New verified nonindigenous amphibians and reptiles in Florida, 1976 through 2015, with a summary of over 152 years of introductions. Reptil. Amphib. 2016, 23, 110–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labisko, J.; Maddock, S.T.; Taylor, M.L.; et al. Chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) undetected in the two orders of Seychelles amphibians. Herpetological Review 2015, 46, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, T.E.S.; Atkins, W.; Herbert, C. On the distribution, ecology and management of non-native reptiles and amphibians in the London Area. Part 1. Distribution and predator/prey impacts. The London Naturalist 2011, 90, 83–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lever, C.; Ceríaco, Luis M. P.; Marques, Mariana P.; Bell, Rayna C.; Aaron, M. Naturalized Reptiles and Amphibians of the World; Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maillard, L. Notes sur l'île de la Réunion (Bourbon); Édition Dentu: Paris, France, 1862. [Google Scholar]

- Matyot, P. The establishment of the crested tree lizard, Calotes versicolor (Daudin, 1802), in Seychelles. Phelsuma 2004, 12, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Measey, J. Overland movement in African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis): a systematic review. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2474–e2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measey, J.; Davies, S.J.; Vimercati, G.; Rebelo, A.; Schmidt, W.; Turner, A. Invasive amphibians in southern Africa: A review of invasion pathways. Bothalia 2017, 47, 12 pages. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measey, G.J.; Rödder, D.; Green, S.L.; Kobayashi, R.; Lillo, F.; Lobos, G.; Rebelo, R.; Thirion, J.-M. Ongoing invasions of the African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis: a global review. Biol. Invasions 2012, 14, 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecke, S. Invasive species: Review risks before eradicating toads. Nature 2014, 511, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirte, D. The terrestrial fauna of the Comoro archipelago. (La faune terrestre de l'archipel des Comores.). Studies in Afrotropical Zoology 2004, 293, 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Meshaka, W.E., Jr.; Collins, S.L.; Bury, R.B.; McCallum, M.L. Exotic Amphibians and Reptiles of the United States; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, Florida, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Midtgaard, R. RepFocus – A Survey of the Reptiles of the World. 2025. Available online: https://www.repfocus.dk/ (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Moore, M.; Fidy, J.F.S.N.; Edmonds, D. The New Toad in Town: Distribution of the Asian Toad, Duttaphrynus Melanostictus, in the Toamasina Area of Eastern Madagascar. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2015, 8, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutou, F. Phelsuma laticauda, nouvelle espèce de lézard récemment introduite à La Réunion. Bull. Phaethon 1995, 1, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mozzi, R.; Deso, G.; Probst, J.-M. Un nouveau gecko vert introduit à La Réunion le Phelsuma astriata semicarinata (Cheke, 1982). Bull. Phaethon 2005, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mwebaze, P.; MacLeod, A.; Tomlinson, D.; Barois, H.; Rijpma, J. Economic valuation of the influence of invasive alien species on the economy of the Seychelles islands. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2614–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, R.A. The Brahminy blind snake (Ramphotyphlops braminus) in the Seychelles Archipelago: distribution, variation, and further evidence for parthenogenesis. Herpetologica 1980, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Owadally, A.W.; Lambert, M. Herpetology in Mauritius. A history of extinction, future hope for conservation. British Herpetological Society Bulletin 1988, 23, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Picker, M.D. Hybridization and Habitat Selection in Xenopus gilli and Xenopus laevis in the South-Western Cape Province. Copeia 1985, 1985, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picker, M.D.; Griffiths, C.L. Alien animals in South Africa – composition, introduction history, origins and distribution patterns. Bothalia 2017, 47, 19 pages. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-M.; Wu, J.-X.; Gunawan, H.; Tu, R.-Q. Optimization of Machining Parameters for Corner Accuracy Improvement for WEDM Processing. Appl. Sci. 2023, 12, 10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceríaco, L.M.P.; Marques, M.P.; Bell, R.C.; Bauer.

- Powell, R.; Henderson, R.W.; Farmer, M.C.; Breuil, M.; Echternacht, A.C.; Van Buurt, G.; Romagosa, C.M.; Perry.

- Probst, J.-M. Animaux de La Réunion. Guide d’Identification des Oiseaux, Mammifères, Reptiles et Amphibiens; Éditions Azalées: Saint-Denis, La Réunion, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo, A.D.; Burger, M.; Bates, M.F.; Branch, W.R.; Conradie, W. Range expansion of the common dwarf gecko, Lygodactylus capensis: South Africa’s most successful reptile invader, 2019.

- Reshetnikov, A.N.; Zibrova, M.G.; Ayaz, D.; Bhattarai, S.; Borodin, O.V.; Borzée, A.; Brejcha, J.; Çiçek, K.; Dimaki, M.; Doronin, I.V.; et al. Rarely naturalized, but widespread and even invasive: the paradox of a popular pet terrapin expansion in Eurasia. NeoBiota 2023, 81, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiß, C.; Olsson, L.; Hoßfeld, U. The history of the oldest self-sustaining laboratory animal: 150 years of axolotl research. J. Exp. Zoöl. Part B: Mol. Dev. Evol. 2015, 324, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, P.P.; Iverson, J.; Shaffer, B.; Bour, R.; Rhodin.

- Rhodin, A.G.J.; Iverson, J.B.; Bour, R.; Fritz, U.; Georges, A.; Shaffer, H.B.; Dijk; P.P. van (Turtle Taxonomy Working Group). Turtles of the World. Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status, 8th ed.; Chelonian Research Monographs, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 1–292. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, G.; Henriette, E. Invasive alien species in Seychelles. Why and how to eliminate them. In Island Biodiversity and Conservation centre, University of Seychelles, Inventaires & biodiversité series Biotope; Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.C.; Meyer, J.-Y.; Holmes, N.D.; Pagad, S. Invasive alien species on islands: impacts, distribution, interactions and management. Environ. Conserv. 2017, 44, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Peris, S. Contribución al estudio de la fauna herpetológica de Rio-de-Oro- Boi. Est. Cent. Ecol. 1975, 4(8), 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M.; Probst, J. M. Distribution and habitat of the invasive giant day gecko Phelsuma grandis Gray 1870 (Sauria: Gekkonidae) in Reunion Island, and conservation implication. Phelsuma 2014, 22, 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, M.; Rocha, S.; Probst, J.-M. Un nouveau gecko nocturne naturalisé sur l’île de La Réunion: Hemidactylus mercatorius Gray, 1842 (Reptilia: Squamata: Gekkonidae). Bull. Soc. Herp. Fr. 2012, 142-143, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Schembri, S. P.; Schembri, P.J. On the occurrence of Agama agama (L.) (Reptilia: Agamidae) in the Maltese Islands. Lavori. Soc. Ven. Sc. Nat. 1984, 9(1), 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, R. Rhinella marina L. (cane toad). In A Handbook of Global Freshwater Invasive Species; 2012; p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- Shine, R.; Alford, R.A.; Blennerhasset, R.; Brown, G.P.; DeVore, J.L.; Ducatez, S.; Finnerty, P.; Greenlees, M.; Kaiser, S.W.; McCann, S.; et al. Increased rates of dispersal of free-ranging cane toads (Rhinella marina) during their global invasion. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.A. Lycodon aulicus capucinus a colubrid snake introduced to Christmas Island, Indian Ocean. Rec. West. AU8t. Mus. 1988, 14(2), 251–252. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.L.; Reid, D.; Robert, B.; Joby, M.; Clément, S. Status and distribution of the angonoka tortoise ( Geochelone yniphora ) of western Madagascar. Biol. Conserv. 1999, 91, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachinis, I.; Kalaentzis, K.; Daftsios, T. First record of an introduced population of Moorish Gecko,Tarentola mauritanica (Linnaeus, 1758), on the island of Rhodes. Herpetology Notes 2025, 18, 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Starmühlner, F. Results of the Austrian Hydrobiological Mission. 1974, to the Seychelles-Comores- and Mascarene Archipelagoes. Part 1. Preliminary Report. Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien 1979, 82, 621–742. [Google Scholar]

- Telford, N.S.; Channing, A.; Measey, J. Origin of Invasive Populations of the Guttural Toad (Sclerophrys gutturalis) on Reunion and Mauritius Islands and in Constantia, South Africa. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 2019, 14(2), 380–392. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.-H.; Yeung, H.Y. An overlooked invader? Integrative analysis reveals the common wolf snake Lycodon capucinus Boie, 1827 is an introduced species to Hong Kong. BioInvasions Rec. 2024, 13, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uetz, P.; Hellermann, J. The Reptile database, 2025. Available online: https://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/contactus.

- Van Wilgen, N. Alien species: reptiles & amphibians. Quest 2008, 4(4), 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wilgena, N.J.; Richardsona, D.M.; Baard, E.H.W. Alien reptiles and amphibians in South Africa: Towards a pragmatic management strategy. South African Journal of Science 2008, 104, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, R.; Rocha, S.J.; Brito, C.; Carranza, S.; Harris, D.J. First report of introduced African Rainbow Lizard Agama agama (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Cape Verde Islands. Herpetozoa 2009, 21, 3/4. [Google Scholar]

- Vences, M.; Wanke, S.; Vieites, D.R.; Branch, W.R.; Glaw, F.; Meyer, A. Natural colonization or introduction? Phylogeographical relationships and morphological differentiation of house geckos (Hemidactylus) from Madagascar. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2004, 83, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinson, A. [Lettre du Dr. Auguste Vinson datée de 1870 pour L. Bouton sur “Agama versicolor”]. Trans. Roy. Soc. Arts Sci. Mauritius (1871) 1870, 1870(5), 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, J.; Vinson, J.M. The saurian fauna of the Mascarene Islands. Bulletin Mauritius Institute 1969, 6, 203–320. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, G.; Probst, J.-M.; Deso, G.; Hawlitschek, O.; Cole, N.; Florens, V. B. V; Dubos, N. Checking back two centuries: a key criterion to identify the wolf snake, Lycodon aulicus (Linnaeus, 1758), in the Mascarene Islands. Herpetology Notes 2021, 14, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, P.; Glaw, F.; Glaw, K.; Böhme, W. Studies on African Agama IV: First record of Agama agama (Sauria: Agamidae) from Madagascar and identity of the alien population on Grande Comore Island. Herpetology Notes 2009, 2, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.; Lewis, R.; Mandimbihasina, A.; Goode, E.; Gibbons, P.; Currylow, A.; Woolaver, L. The conservation of the world’s most threatened tortoise: the ploughshare tortoise (Astrochelys yniphora) of Madagascar. Testudo 2022, 8(2), 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson, J.B.; Wermuth, H.; Mertens, R. Liste der Rezenten Amphibien und Reptilien. Testudines, Crocodylia, Rhynchocephalia. Copeia 1979, 1979, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Gower, D.; Labisko, J.; Morel, C.; Bristol, R.; Wilkinson, M.; Maddock, S. Are the Mascarene frog (Ptychadena mascareniensis) and Brahminy blind snake (Indotyphlops braminus) really alien species in the Seychelles? 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).