Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

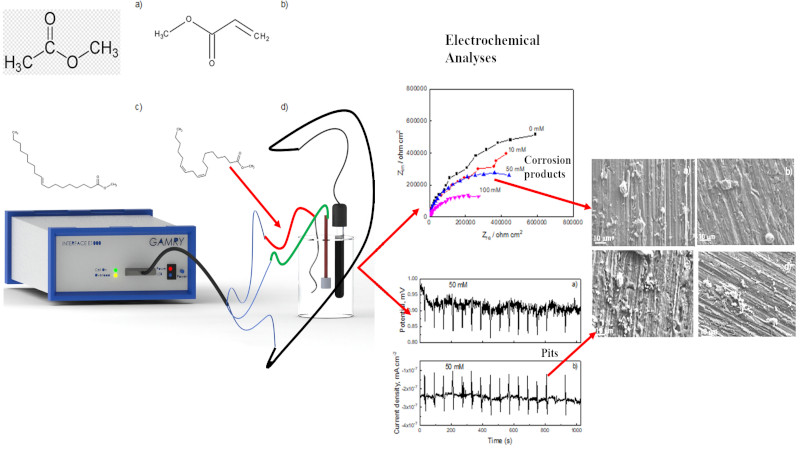

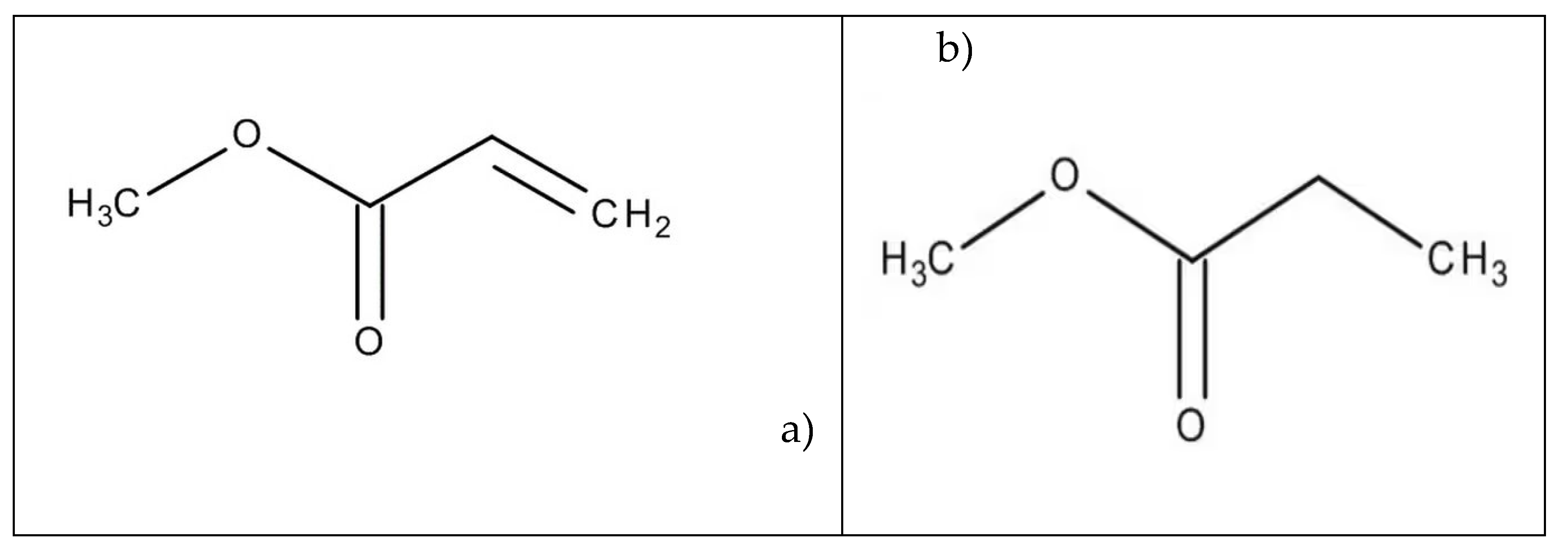

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Testing Solution

2.2. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

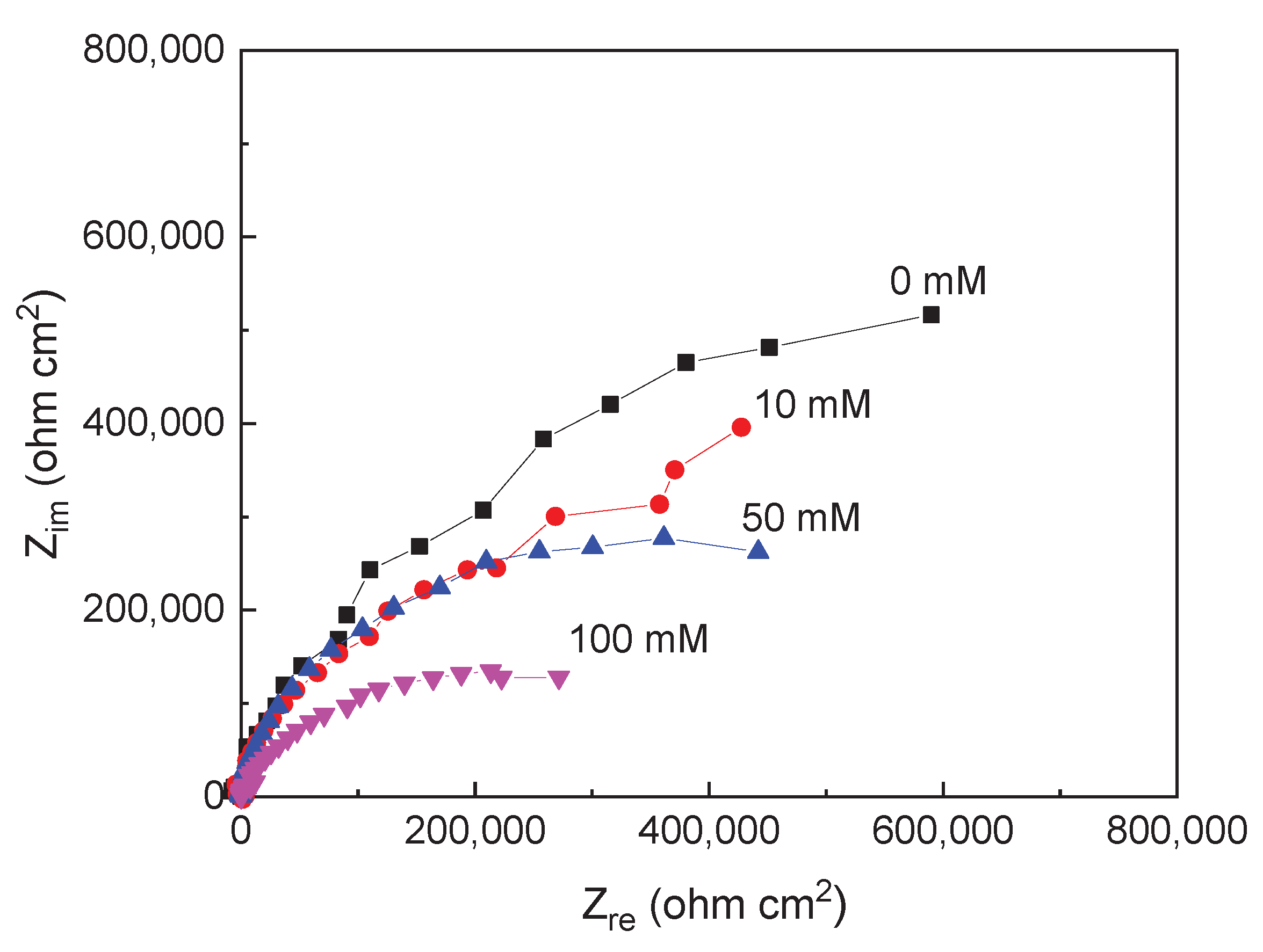

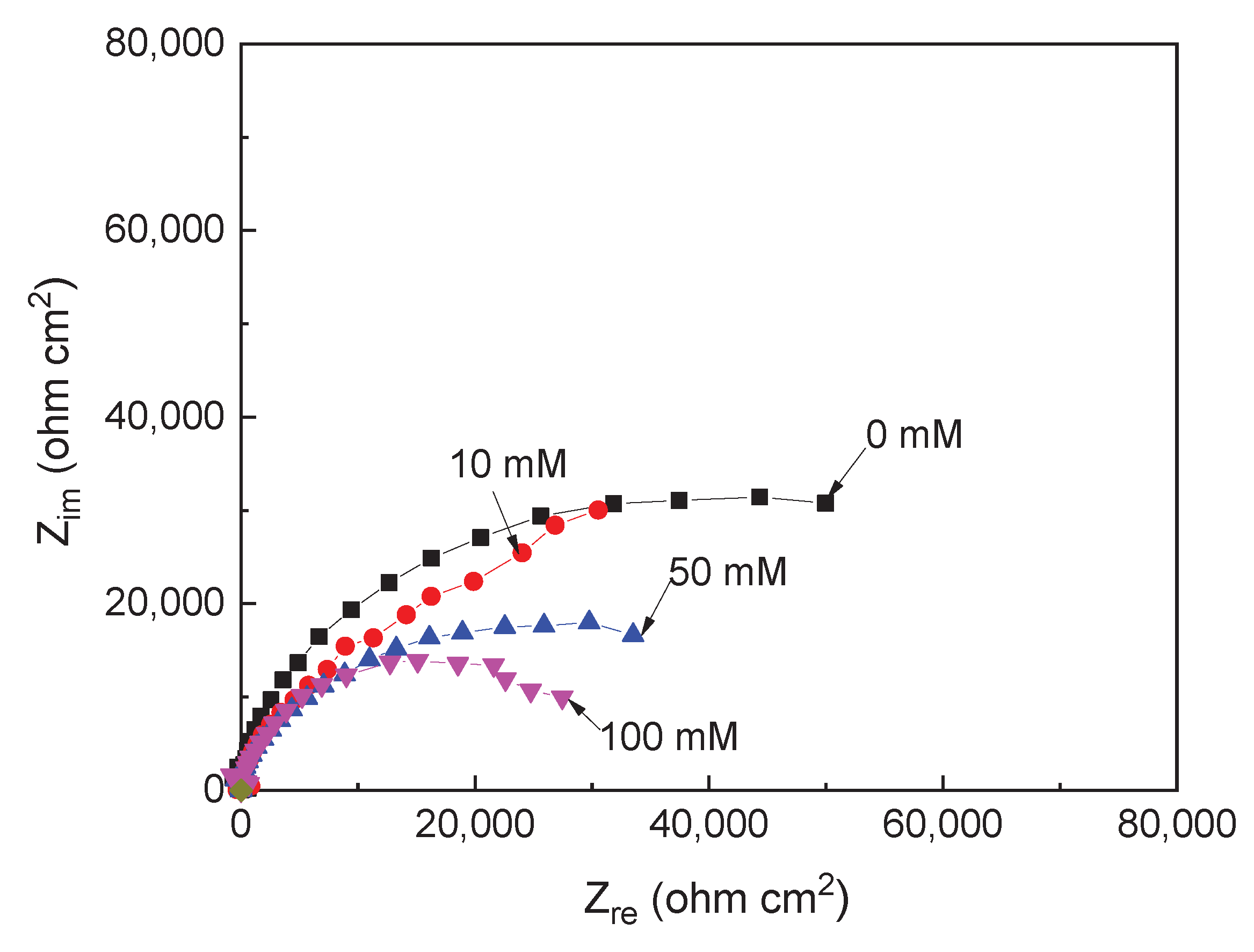

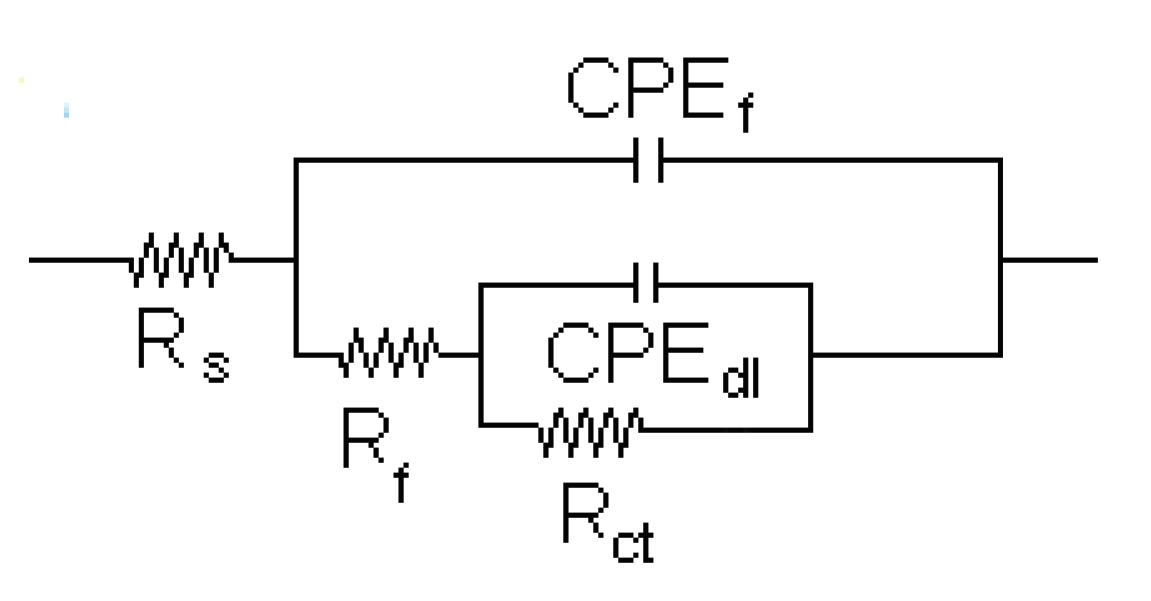

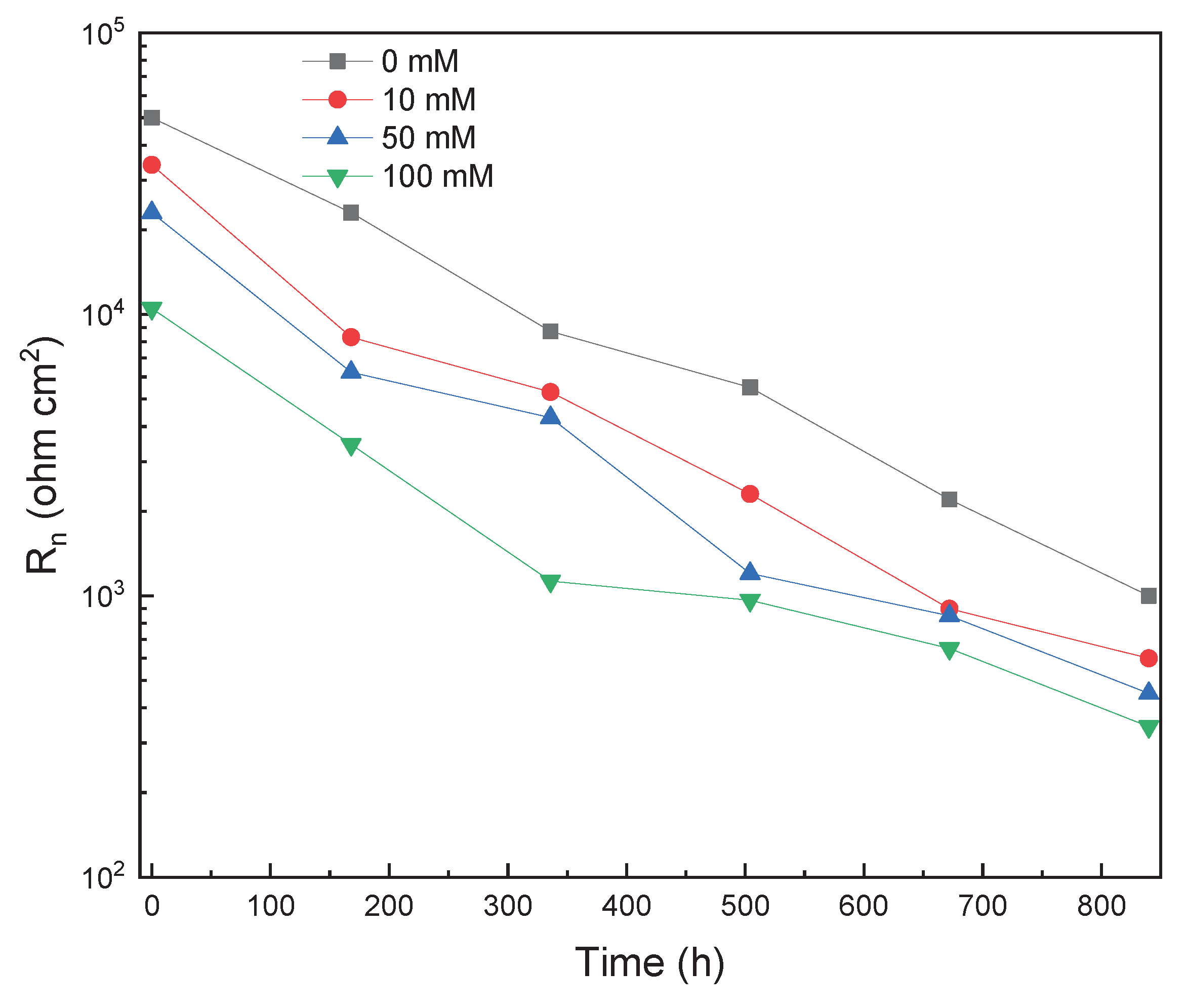

3.1. EIS Measurements

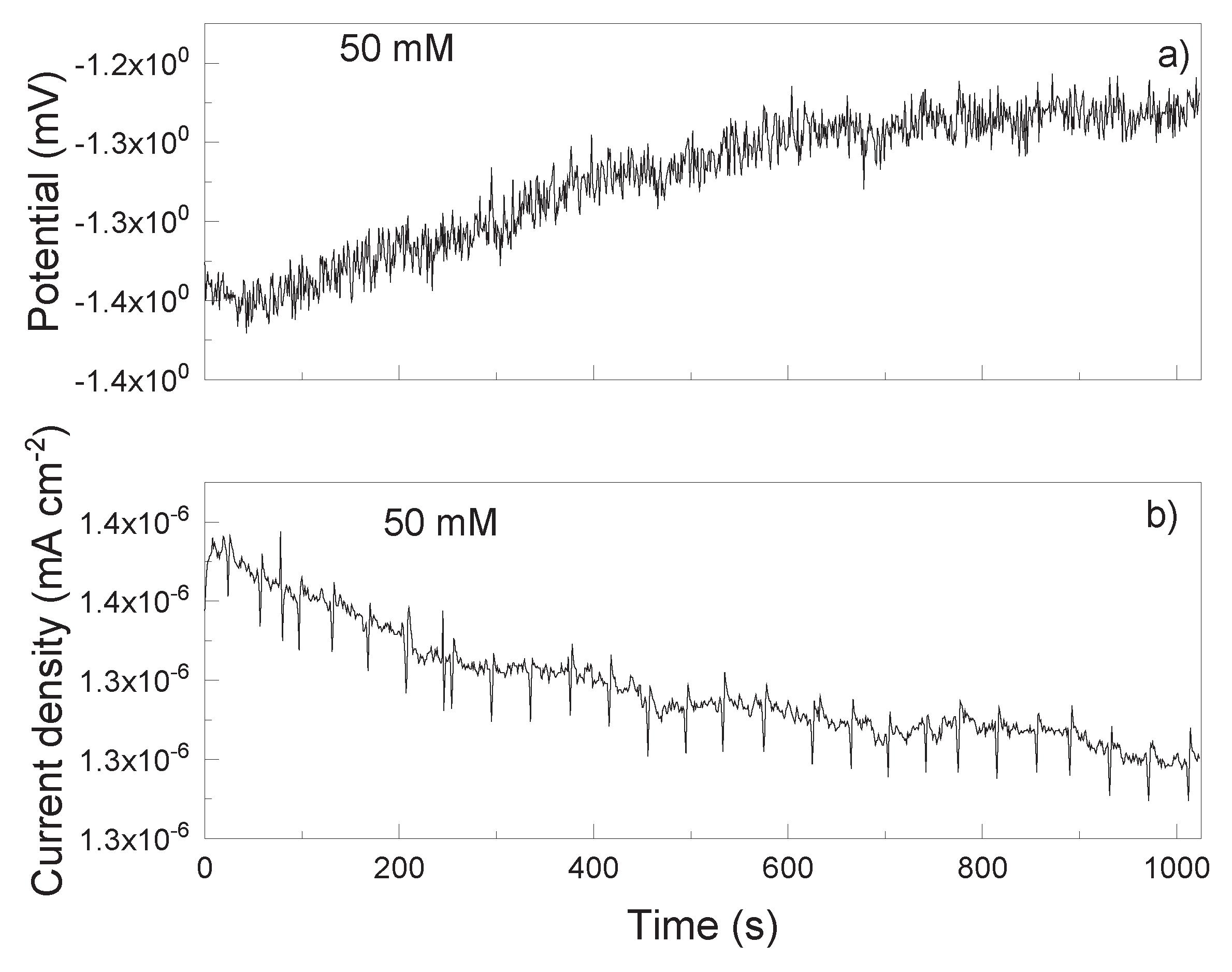

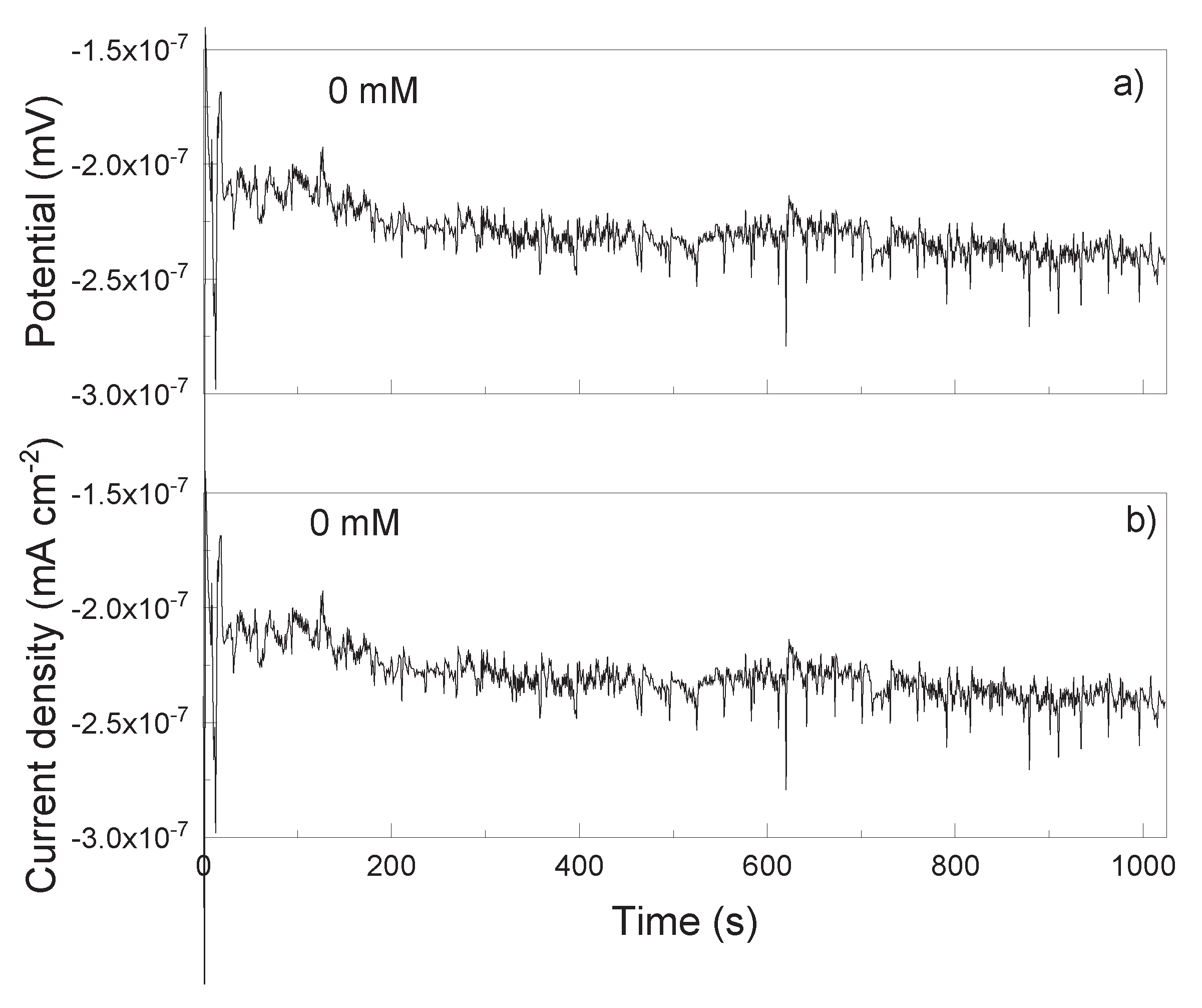

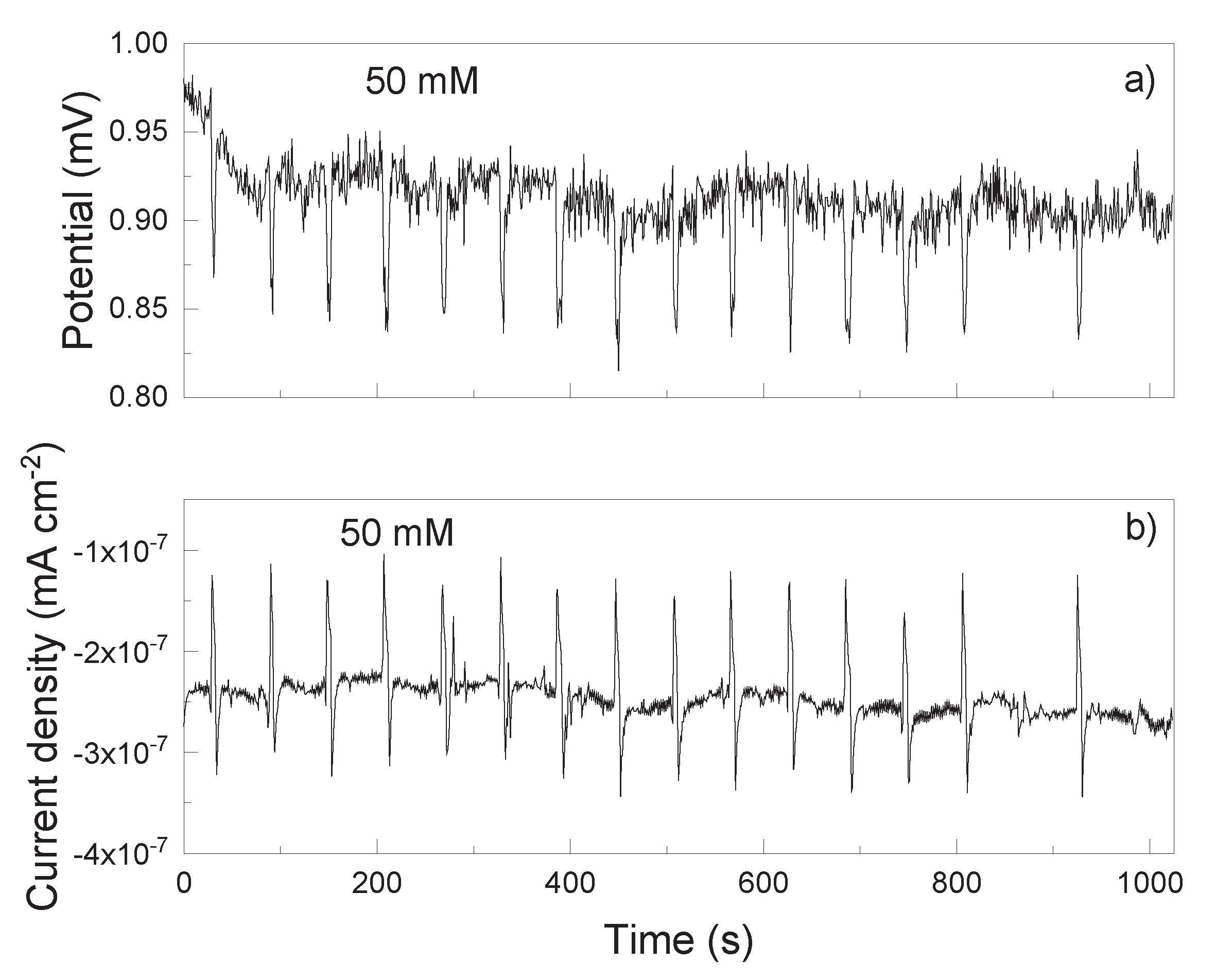

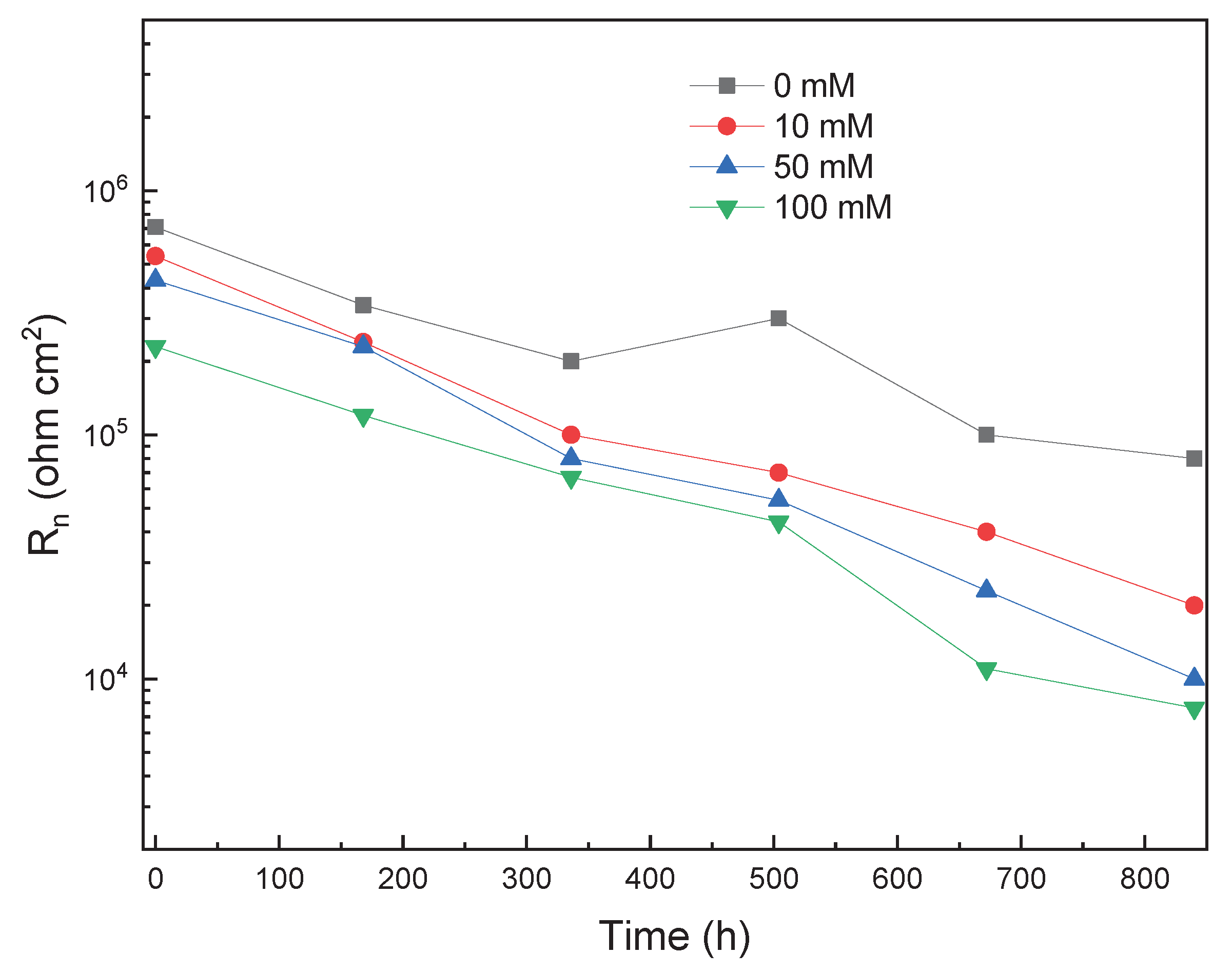

3.2. EN Measurements

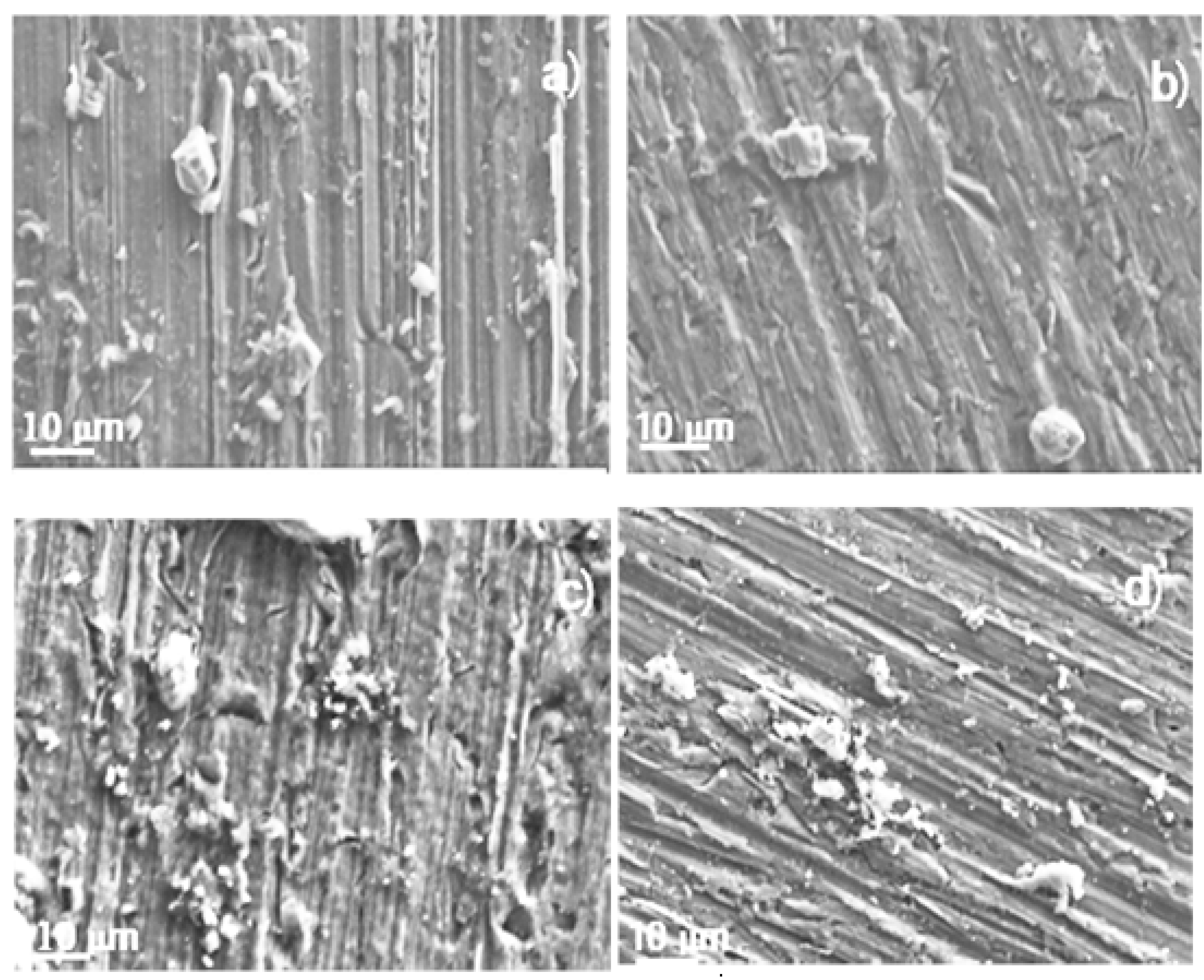

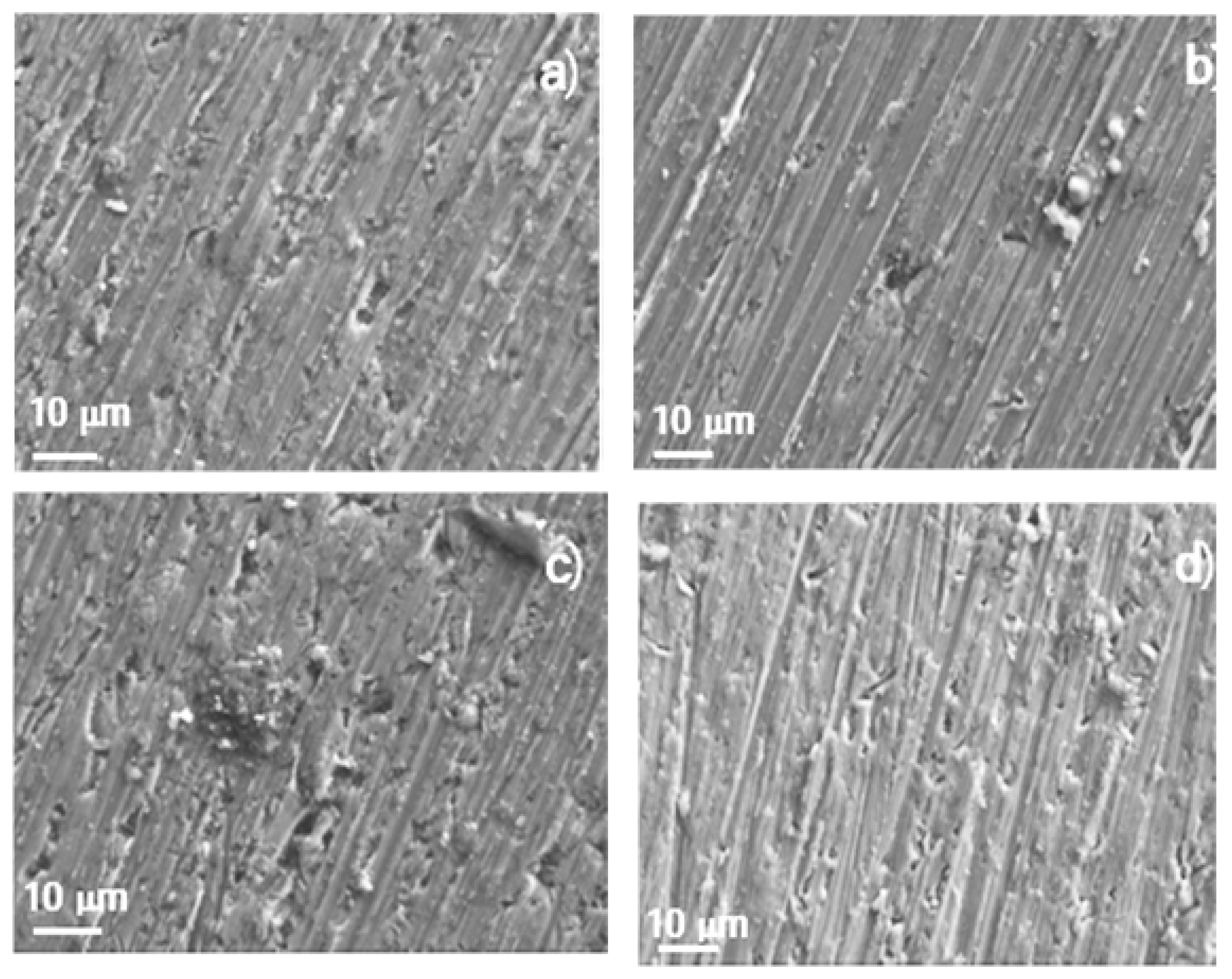

3.3. Corroded Surface Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Data availability

References

- Yang, G.; Yu, J. Advancements in Basic Zeolites for Biodiesel Production via Transesterification. Chemistry 2023, 5, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülüm, M.; Bilgin, A. A comprehensive study on measurement and prediction of viscosity of biodiesel-diesel-alcohol ternary blends. Energy 2018, 148, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosarof, M.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Alabdulkarem, A.; Habibullah, M.; Arslan, A. Assessment of friction and wear characteristics of Calophyllum inophyllum and palm biodiesel. Ind. Crop Prod. 2016, 83, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; El-Gendy, N.; Abdel-Rehim, A.A.; Ashour, F.; Sadek, M.A. Biodiesel production from castor oil in Egypt: process optimisation, kinetic study, diesel engine performance and exhaust emissions analysis. Energy 2018, 157, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yuan, K.; Zhu, G.; Wang, W. Friction and wear behaviors of catalytic methylesterified bio-oil. Tribol. Int. 2014, 71, 168174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G.; Steidley, K.R. The effect of metals and metal oxides on biodiesel oxidative stability from promotion to inhibition. Fuel Process Technol. 2018, 177, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, S.; Sriram, G.; Ellappan, R. Bio-lubricant-biodiesel combination of rapeseed oil: An experimental investigation on engine oil tribology, performance, and emissions of variable compression engine. Energy 2014, 72, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, I.M.A.; Barradas-Filho, A.O.; Marques, E.P.; Pereira, C.F.; Marques, A.L.B. Oxidative stability of biodiesel by mixture design and a four-component diagram. Fuel 2018, 219, 389398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, I.M.R.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Mofijur, M.; Abedin, M.J. Effect of antioxidant on the performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with palm biodiesel blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 79, 265272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Effect of temperature on the corrosion behavior of mild steel upon exposure to palm biodiesel. Energy 2011, 36, 3328–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.V.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Fazal, M.A.; Gupta, M. Corrosion of magnesium and aluminum in palm biodiesel: a comparative evaluation. Energy 2013, 57, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. A review of the effect of biodiesel on the corrosion behavior of metals/alloys in diesel engines. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2020, 42, 2923–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Vu, H.N. Interactions between Used Cooking Oil Biodiesel Blends and Elastomer Materials in the Diesel Engine. Int. J. Ren. Energy Dev. 2019, 8, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.M.; Dutra-Pereira, F.K.; Bicudo, T.C. Influence of stainless steel corrosion on biodiesel oxidative stability during storage. Fuel 2019, 249 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelmeier, C.L.; Monteiro, M.R.; Da Silva, R.; Kuri, S.E.; Sordi, V.L.; Della Rovere, C. A. Corrosion behavior of carbon steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and copper upon exposure to biodiesel blended with petrodiesel. Energy 2021, 226, 120344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Saxena, R.C.; Kumar, A.; Negi, M.S.; Bhatnagar, A.K.; Goyal, H. Corrosion Behavior of Biodiesel from Seed Oils of Indian Origin on Diesel Engine Parts. Fuel Process Technol. 2007, 88, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Biodiesel degradation mechanism upon exposure of metal surfaces: A study on biodiesel sustainability. Fuel 2022, 310, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Pan, L.; Jiang. Corrosion behavior of metals in biodiesel from rapeseed oil and methanol. Renewable Energy 2012, 37, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Ann, L.J.; Fazal, M.A. Corrosion Characteristics of Copper and Leaded Bronze in Palm Biodiesel. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCornick, R.L.; Ratcliff, M.; Moens, L.; Lawrence, T. Several factors affecting the stability of biodiesel in standard accelerated tests. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007, 88, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Comparative Corrosive Characteristics of Petroleum Diesel and Palm Biodiesel for Automotive Materials. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmad, M.S.; Hassan, M.B.H.; Kalam, M.A. Comparative corrosion characteristics of automotive materials in Jatropha biodiesel. Int. J. Green Energy 2018, 15, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuleta, E.C.; Baena, L.; Rios, L.A.; Calderon, J.A. The oxidative stability of biodiesel and its impact on the deterioration of metallic and polymeric materials: a review. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 23, 2159–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, W.; You, Y.; Liu, L. Molecular modeling of the inhibition mechanism of 1-(2-aminoethyl)-2-alkyl-imidazoline. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ballote, L.; López-Sansores, J.F.; Maldonado-López, L.; Garfias-Mesias, L.F. Corrosion Behavior of Aluminum Exposed to a Biodiesel. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehan, S.; Jerman, M.S.; Kegl, M.; Kegl, B. Biodiesel influence on tribology characteristics of a diesel engine. Fuel 2009, 88, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.M.; Mello, V.S.; Medeiros, J.S. Palm and soybean biodiesel compatibility with fuel system elastomers. Tribol. Int. 2013, 65, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladky, K.; Dawson, J.L. The measurement of localized corrosion using electrochemical noise. Corros. Sci. 1982, 22, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solution | Conc., mM | CPEdl F cm-2 |

ndl | Rct ohm cm2 |

CPEf F cm-2 |

nf | Rf ohm cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl propionate + methyl acrylate | 0 | 1.6 x 10-4 | 0.71 | 9.9 x 104 | 1.3 x 10-5 | 0.98 | 6.4 x 105 |

| 10 | 2.4 x 10-4 | 0.99 | 4.9 x 104 | 5.2 x 10-5 | 0.49 | 5.8 x 105 | |

| 50 | 8.7 x 10-4 | 0.78 | 3.3 x 104 | 2.7 x 10-4 | 0.99 | 3.9 x 105 | |

| 100 | 3.2 x 10-3 | 0.99 | 2.4 x 104 | 8.4 x 10-4 | 0.35 | 1.2 x 105 | |

| Methyl oleate + methyl linoleate | 0 | 8.5 x 10-4 | 0.52 | 7.4 x 103 | 1.0x 10-4 | 0.98 | 5.0 x 104 |

| 10 | 3.8 x 10-3 | 0.99 | 6.7 x 103 | 2.6 x 10-4 | 0.20 | 2.8 x 104 | |

| 50 | 5.1 x 10-3 | 0.42 | 5.5 x 103 | 2.1 x 10-3 | 0.99 | 1.7 x 104 | |

| 100 | 8.7 x 10-3 | 0.99 | 3.4 x 103 | 5.1 x 10-3 | 0.25 | 8.2 x 103 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).