Submitted:

17 July 2025

Posted:

18 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Coating Production

2.2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology

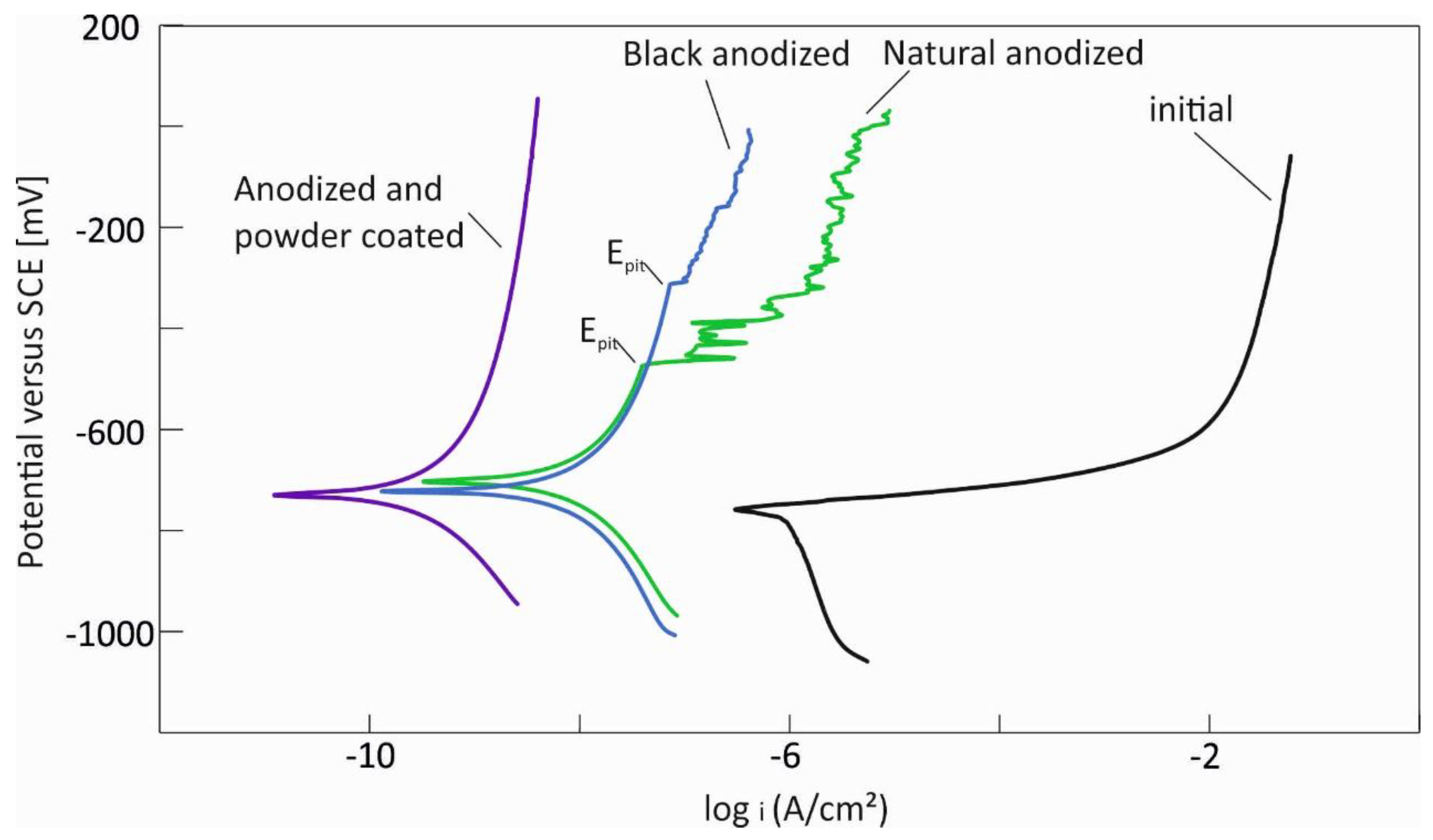

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

| Sample | Ecorr [mV] |

Icorr [A/cm²] |

βa | βc | Corrosion rate [mmpy] |

| Initial | -0.756 | 9 * 10⁻⁷ | 0.022 | -0.52 | 0.03 |

| Natural anodized | -0.702 | 2.72* 10⁻⁸ | 0.78 | -0.52 | 0.0009 |

| Black anodized | -0.722 | 4 * 10⁻⁸ | 1.19 | -0.86 | 0.0014 |

| Anodized and powder coated | -0.729 | 9.72 * 10⁻¹⁰ | 0.91 | -0.46 | 0.0004 |

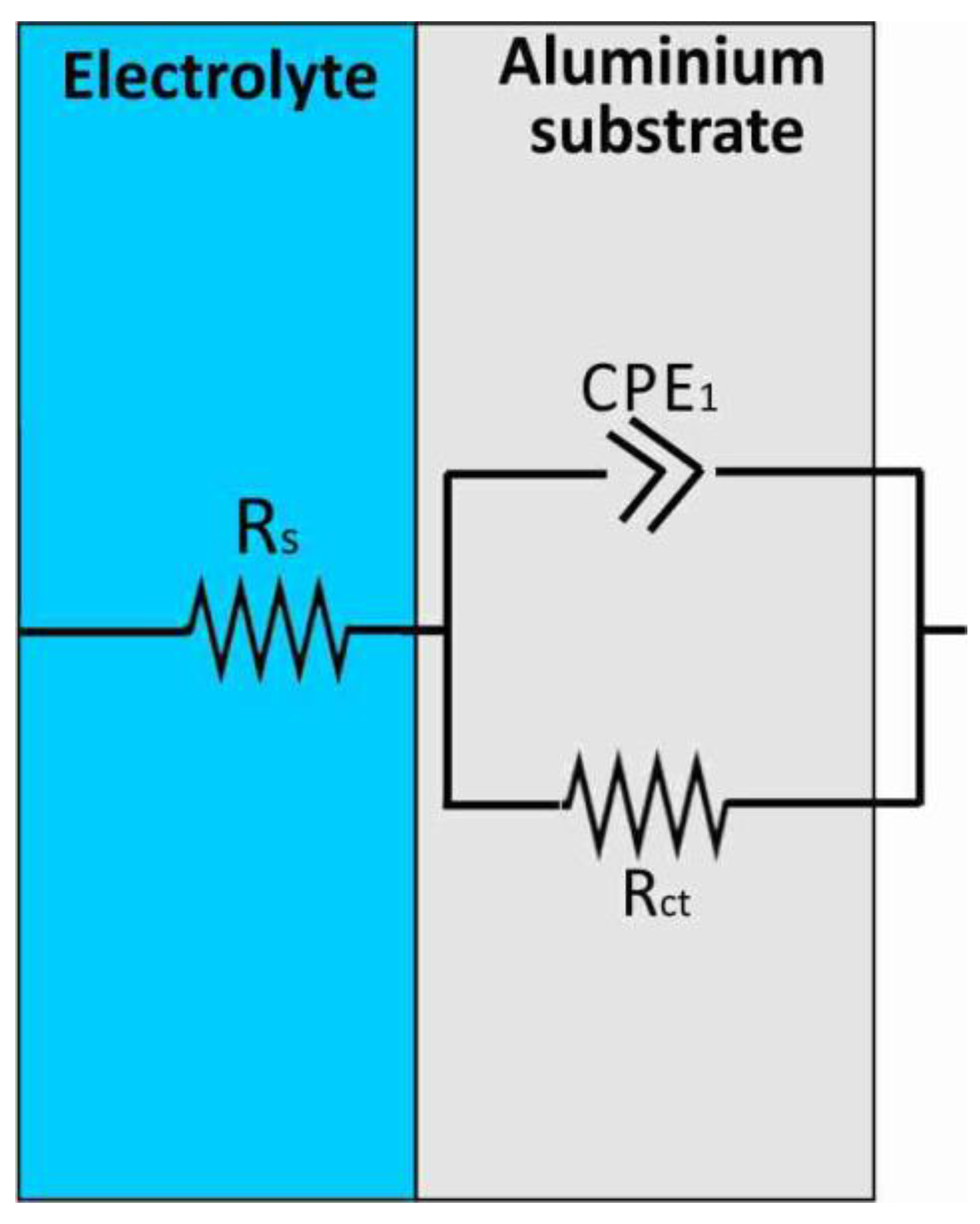

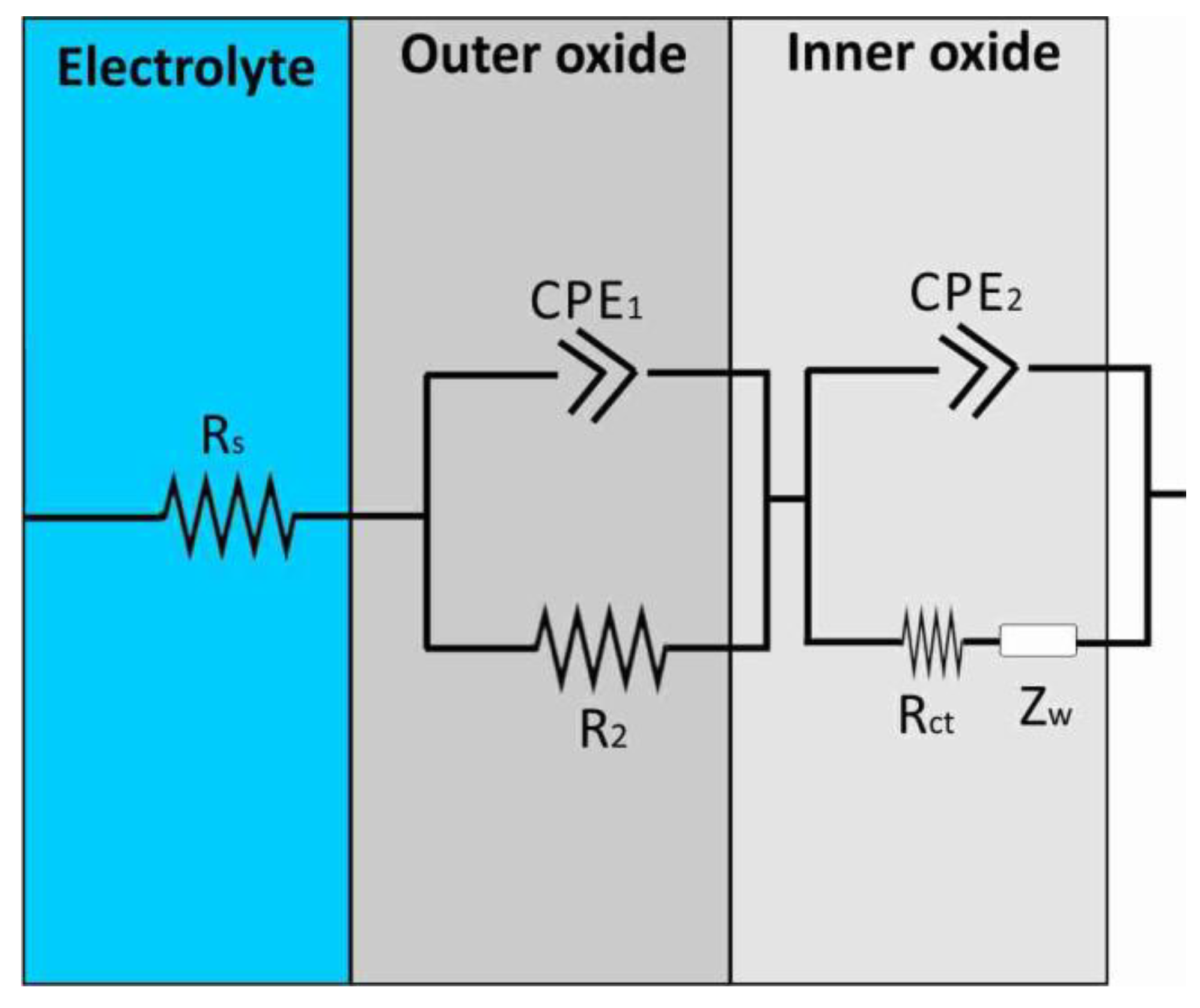

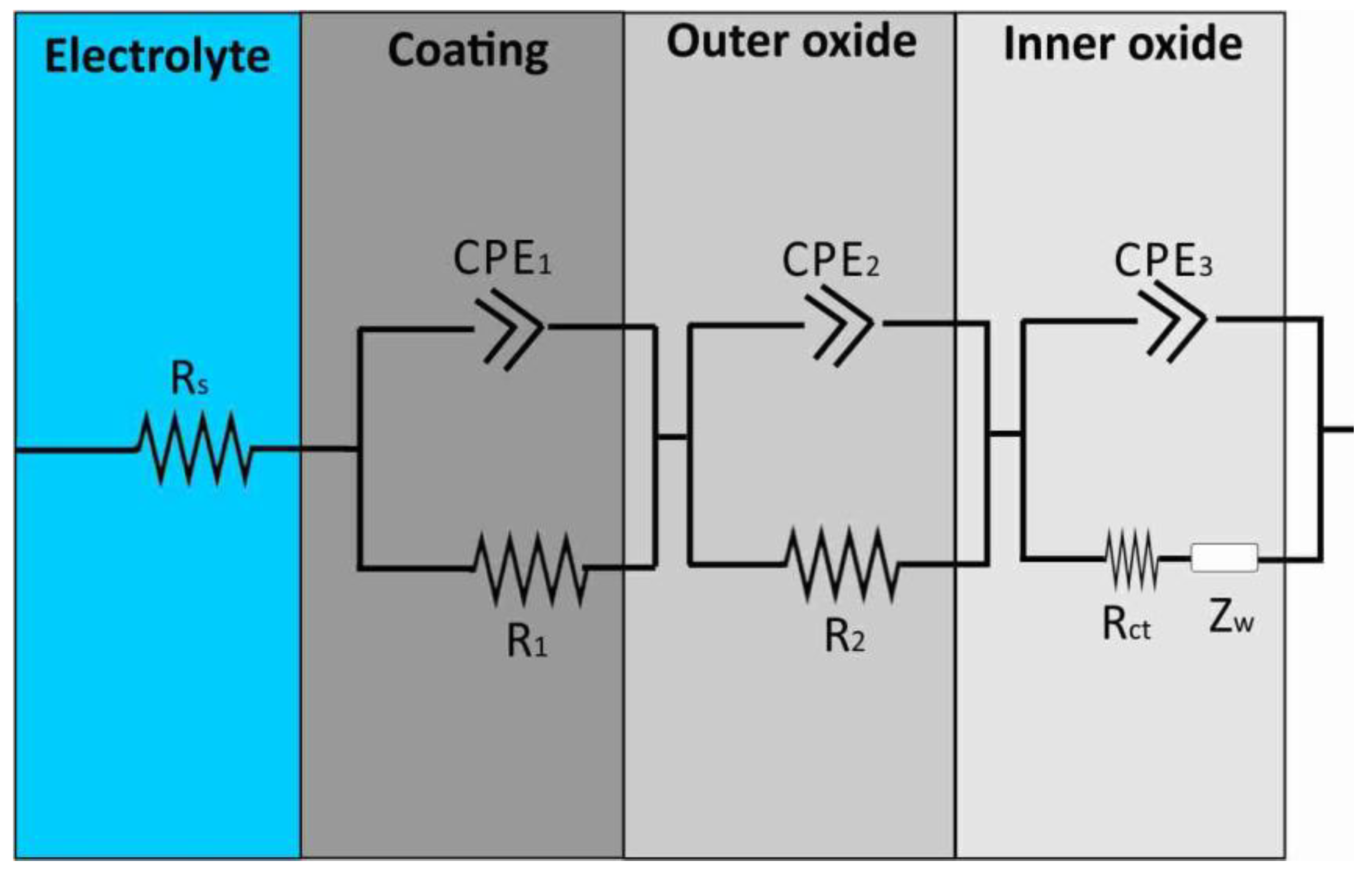

3.3. Proposed Equivalent Electrical Circuit Models

|

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Surface treatments significantly improve corrosion resistance. Anodized samples demonstrate approximately 30 times lower corrosion rate, while the anodized and powder-coated samples offer the highest protection, with a corrosion rate nearly 1000 times lower than that of the untreated aluminium.

- (2)

- The natural sample showed an almost ideal dielectric behavior (α ~ 1) and a charge transfer resistance of 1.48 MΩ, indicating a uniform oxide. The clear anodized sample had higher anodic resistance but lower Rct (0.74 MΩ) suggesting reduced oxide quality, likely due to porosity or dye effects.

- (3)

- The pre-anodized and powder coated samples demonstrates a complex multilayer electrochemical behavior that explains its superior protective performance. The outer layer exhibits very high resistance (7.5 MΩ) and excellent dielectric properties (α = 0.95), indicating an effective barrier against corrosion.

- (4)

- The high values of resistance for the anodized samples indicate that the sealing process was highly effective.

- (5)

- The calculated average thicknesses of the anodized layers confirm the SEM results.

References

- Jawalkar, C., Kant, S., & Yashpal. (2015). A review on use of aluminium alloys in aircraft components. i-Manager’s Journal on Material Science, 3(3), 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Egorkin, V. S. Vyaliy, I. E., Gnedenkov, A. S., Kharchenko, U. V., Sinebryukhov, S. L., & Gnedenkov, S. V. (2024). Corrosion properties of the composite coatings formed on PEO pretreated AlMg3 aluminum alloy by dip-coating in polyvinylidene fluoride-polytetrafluoroethylene suspension. Polymers, 16(20), 2945. [CrossRef]

- Peltier, F., & Thierry, D. (2024). Development of a reliable accelerated corrosion test for painted aluminum alloys used in the aerospace industry. Corrosion and Materials Degradation, 5(3), 427–438. [CrossRef]

- Gyarmati, G., & Erdélyi, J. (2025). Intermetallic phase control in cast aluminum alloys by utilizing heterogeneous nucleation on oxides. Metals, 15(4), 404. [CrossRef]

- Akhyar, A., Syahrial, A., & Syahrul, M. (2018). Cooling rate, hardness and microstructure of aluminum cast alloys. International Journal of Science and Engineering, 10(1), 1–6.

- Guo, F., Cao, Y., Wang, K., Zhang, P., Cui, Y., Hu, Z., & Xie, Z. (2022). Effect of the anodizing temperature on microstructure and tribological properties of 6061 aluminum alloy anodic oxide films. Coatings, 12(3), 314. [CrossRef]

- Cabral-Miramontes, J. Cabral-Miramontes, N., Nieves-Mendoza, D., Lara-Banda, M., Maldonado-Bandala, E., Olguín-Coca, J., Lopez-Leon, L. D., Estupinan-Lopez, F., Calderon, F. A., & Gaona Tiburcio, C. (2024). Anodizing of AA2024 aluminum–copper alloy in citric-sulfuric acid solution: Effect of current density on corrosion resistance. Coatings, 14(7), 816. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K. U. Panemangalore, D. B., Kuruveri, S. B., John, M., & Menezes, P. L. (2022). Surface Modification of 6xxx Series Aluminum Alloys. Coatings, 12(2), 180. [CrossRef]

- Nazeri Abdul Rahman, C. J., Allene Albania Linus, B. H. M. Jan, A. Parabi, C. K. Ming, A. S. L. Parabi, A. James, N. S. Shamsol, S. B. John, E. F. Kushairy, A. A. Jitai, & D. F. A. A. Hamid. (2025). Corrosion resistance and electrochemical adaptation of aluminium in brackish peat water sources under seawater intrusion in the rural tropical peatlands of Borneo. Sustainable Chemistry for Climate Action, 6, Article 100074. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, W., Chen, W., Hong, H., & Zhang, T. (2025). Long-Term Corrosion Behavior of 434 Stainless Steel Coatings on T6061 Aluminum Alloy in Chloride Environments. Coatings, 15(2), 144. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., et al. (2025). "Transition from pitting to intergranular corrosion of 2024-T351 aluminum alloy under atmospheric environment." Journal of Magnesium and Alloys. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2238785425005150.

- Guo, Y., et al. (2025). "Corrosion mechanism of aviation aluminum alloy 7B04 under sulfate-reducing bacteria." RSC Advances, 15, 12230–12239. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2025/ra/d5ra02115d.

- Zhao, J., et al. (2023). "Atmospheric corrosion behavior of typical aluminum alloy at low temperature." Metals, 13(3), 277. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/13/3/277.

- Malaret, F. (2022). Exact calculation of corrosion rates by the weight-loss method. Experimental Results, 3, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Cabrini, M., Lorenzi, S., Pastore, T., Pellegrini, S., Burattini, M., & Miglio, R. (2017). Study of the corrosion resistance of austenitic stainless steels during conversion of waste to biofuel. Materials, 10(3), 325. [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, E. (2025). Quantification of hydrogen evolution in corrosion testing by buoyancy measurements [Preprint]. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Li, J., & Wang, H. (2022). Experimental study on neutral salt spray accelerated corrosion of metal protective coatings for power-transmission equipment. Materials, 15(4), 1234.

- Singh, A., Kumar, P., & Sharma, R. (2021). Corrosion resistance evaluation of coated aluminum alloys using salt spray and electrochemical methods. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research, 18(2), 567-578.

- Chen, Y., Liu, X., & Zhao, F. (2020). Salt spray testing and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for corrosion behavior analysis of anodized aluminum. Surface and Coatings Technology, 385, 125391.

- Patel, S., Mehta, D., & Joshi, M. (2019). Effect of organic coatings on corrosion resistance of aluminum alloys evaluated by salt spray and electrochemical tests. Progress in Organic Coatings, 132, 146-154.

- Kim, J. Lee, S., & Park, C. (2018). Corrosion performance of hybrid organic-inorganic coatings on aluminum alloys in salt spray tests. Corrosion Science, 137, 14-23.

- Jáquez-Muñoz, J. M. Gaona-Tiburcio, C., Méndez-Ramírez, C. T., Martínez-Ramos, C., Baltazar-Zamora, M. A., Santiago-Hurtado, G., Estupinan-Lopez, F., Landa-Ruiz, L., Nieves-Mendoza, D., & Almeraya-Calderon, F. (2024). Electrochemical Noise Analysis: An Approach to the Effectivity of Each Method in Different Materials. Materials, 17(16), 4013. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Wang, F., & Chen, Y. (2021). Application of electrochemical noise technique in corrosion monitoring of metals: A review. Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 70, 140–154. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Sun, Y., & Gao, Y. (2022). Electrochemical noise analysis of corrosion behavior of magnesium alloys in simulated body fluid. Corrosion Science, 195, 109987. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Sun, W., & Wang, H. (2023). Using electrochemical noise technique to evaluate corrosion inhibition performance of novel coatings on steel. Surface and Coatings Technology, 456, 129720. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A. L. & Castaño, V. (2012). Corrosion analysis by electrochemical noise: A teaching approach. Journal of Materials Education, 34, 151–159.

- Barsoukov, E. & Macdonald, J. R. (Eds.). (2018). Impedance spectroscopy: Theory, experiment, and applications (2nd ed.). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Lasia, A. (2014). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and its applications. In B. E. Conway, R. E. White, & J. O’M. Bockris (Eds.), Modern aspects of electrochemistry (pp. 143–248). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, B. A. (2015). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS): An overview. Journal of Electroceramics, 35(2), 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Sherif, E.-S. M., & Karim, N. A. (2020). Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy for corrosion monitoring and evaluation of corrosion inhibitors. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 254, 123464. [CrossRef]

- Bjørgum, A. Lapique, F., Walmsley, J. C., & Redford, K. (2003). Anodizing as pre-treatment for structural bonding. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives, 23(5), 401–412. [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, S. U. Fernandes, F. A. O., & Pereira, A. B. (2020). The Sealing Step in Aluminum Anodizing: A Focus on Sustainable Strategies for Enhancing Both Energy Efficiency and Corrosion Resistance. Coatings, 10(3), 226. [CrossRef]

- Raffin, F. Echouard, J., & Volovitch, P. (2023). Influence of the Anodizing Time on the Microstructure and Immersion Stability of Tartaric-Sulfuric Acid Anodized Aluminum Alloys. Metals, 13(5), 993. [CrossRef]

- Hsing-Hsiang Shih, Yu-Chieh Huang, Study on the black electrolytic coloring of anodized aluminum in cupric sulfate, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Volume 208, Issues 1–3, 2008, Pages 24-28. [CrossRef]

- Mrówka, G. Sieniawski, J., & Wierzbińska, M. (2007). Analysis of intermetallic particles in AlSi1MgMn aluminium alloy. Journal of Achievements in Materials and Manufacturing Engineering, 20(1-2), 283–286.

- Bara, M. Niedźwiedź, M., & Skoneczny, W. (2019). Influence of Anodizing Parameters on Surface Morphology and Surface-Free Energy of Al2O3 Layers Produced on EN AW-5251 Alloy. Materials, 12(5), 695. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. A. (2009). Metastable and stable pitting events on Al induced by chlorate and perchlorate anions—Polarization, XPS and SEM studies. Electrochimica Acta, 54(6), 1857–1863. [CrossRef]

- Radon, A. Ciuraszkiewicz, A., Łukowiec, D., Toroń, B., Baran, T., Kubacki, J., & Włodarczyk, P. (2025). From micro to subnano scale: Insights into the dielectric properties of BiOI nanoplates. Materials Today Nano, 100649. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M. A. Maia, F., Matykina, E., Arrabal, R., Mohedano, M., & Vega, J. M. (2025). Active corrosion protection of AA2024T3 by the synergy of flash-PEO/Ce coating and epoxy coating loaded with LDH/eco-friendly gluconate. Progress in Organic Coatings, 206, 109359. [CrossRef]

- Rodič, P. Kapun, B., & Milošev, I. (2024). Complementary corrosion protection of cast AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy using Zr-Cr conversion and polyacrylic/siloxane-silica multilayer coatings. npj Materials Degradation, 8, 58. [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A. Ch. & Prodromidis, M. I. (2023). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy — A tutorial. ACS Measurement Science Au, 3, 162–193. [CrossRef]

- Stergioudi, F. Vogiatzis, C. A., Gkrekos, K., Michailidis, N., & Skolianos, S. M. (2015). Electrochemical corrosion evaluation of pure, carbon-coated and anodized Al foams. Corrosion Science, 91, 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Huayuelong Huang, Hong Shih, Huochuan Huang, John Daugherty, Shun Wu, Sivakami Ramanathan, Chris Chang, & Florian Mansfeld. (2008). Evaluation of the corrosion resistance of anodized aluminum 6061 using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Corrosion Science, 50(12), 3569–3575. [CrossRef]

- Córdoba-Torres, P. (2017). Relationship between constant-phase element (CPE) parameters and physical properties of films with a distributed resistivity. Electrochimica Acta, 225, 592–604. [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.-Y. (2020). Conversion of a constant phase element to an equivalent capacitor. Journal of Electrochemical Science and Technology, 11(3), 318–321. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Shih, H., Huang, H., Daugherty, J., Wu, S., Ramanathan, S., Chang, C., & Mansfeld, F. (2008). Evaluation of the corrosion resistance of anodized aluminum 6061 using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Corrosion Science, 50(12), 3569–3575. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).