1. Introduction

Light-induced mechanical actuation in materials offers a powerful route to remote, reversible control of shape and function, supporting advances in soft robotics, adaptive optics, and smart surfaces [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The development of artificial molecular machines, including light-driven rotary motors, was recognized by the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded to Ben Feringa, Fraser Stoddart, and Jean-Pierre Sauvage, “for the design and synthesis of molecular machines” [

7], underscoring the significance of light-reversible motion at the molecular scale. Photomechanical materials, which hold the intrinsic ability to undergo mechanical deformation in response to light, can be deposited in thin layers onto flexible and mechanically strong host materials, inducing substantial bending or actuation of the entire structure, even when the support is significantly thicker than the active photomechanical layer itself. Among these, azobenzene-containing systems have emerged as a model platform, where light-induced molecular

cis–trans isomerization of azobenzene moieties drives macroscopic shape changes and influences mechanical properties [

8].

Photo-responsive molecules capable of reversible shape change include those that undergo photo-dimerization (e.g., coumarins, anthracenes), intra-molecular bond formation (e.g., fulgides, spiropyrans, diarylethenes), and photo-isomerization (e.g., stilbenes, crowded alkenes, azobenzene) [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The most ubiquitous natural molecule for reversible shape change is the rhodopsin/retinal protein system that enables vision, representing perhaps the quintessential reversible photo-switch [

18]. The small retinal molecule embedded in a cage of rhodopsin helices isomerizes from a

cis geometry to a

trans geometry around a carbon-carbon double bond with the absorption of just a single photon. The modest shape change of just a few angstroms is quickly amplified and sets off a cascade of greater shape and chemical changes, eventually culminating in an electrical signal to the brain that allows vision. The energy of the input photon is amplified thousands of times in the process. The process is fully reversible through biochemical pathways that revert the

trans isomer back to

cis, enabling subsequent cycles. While the complexity of the rhodopsin system limits its direct engineering application, azobenzene stands out as an effective artificial mimic due to its rapid, reversible switching, high fatigue resistance, and synthetic versatility [

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

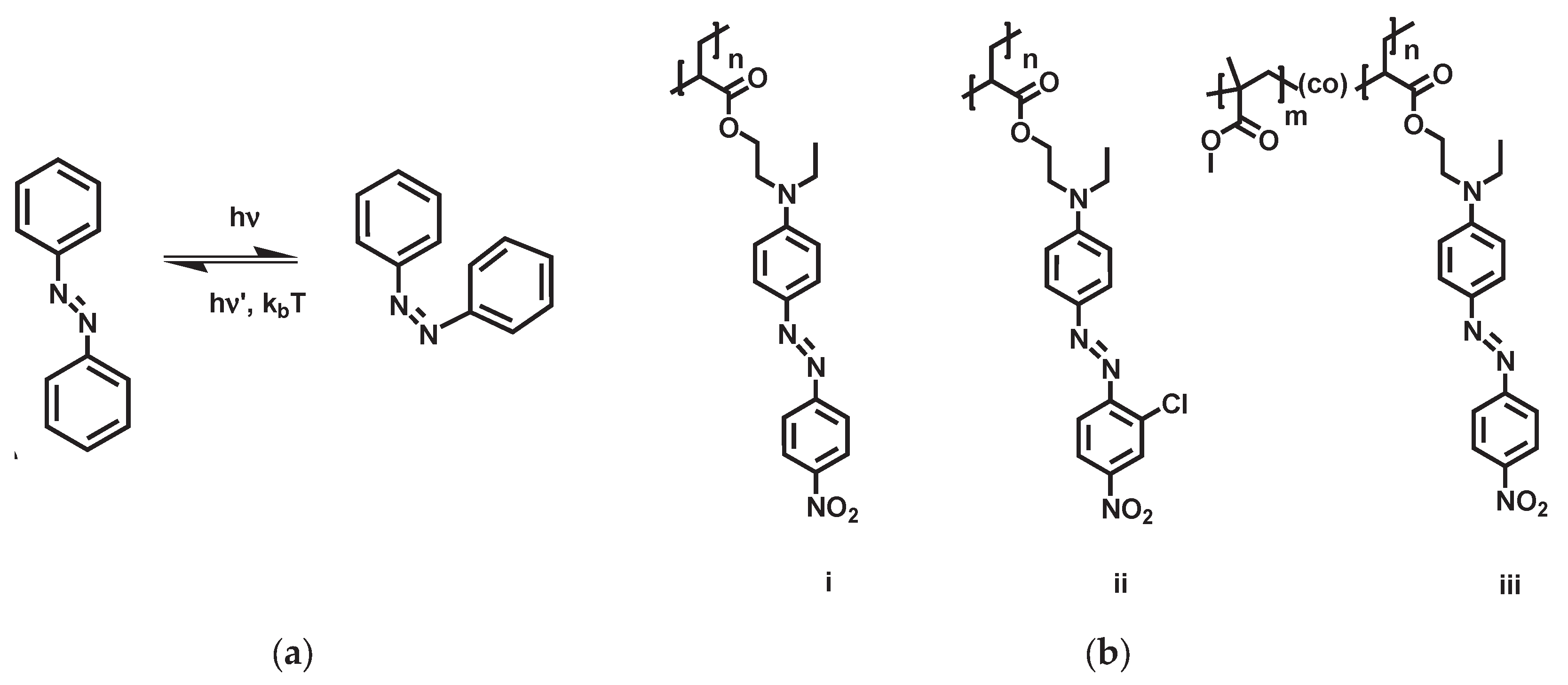

Azobenzenes are aromatic chromophores composed of two phenyl rings linked by an azo (–N=N–) group, capable of reversible photo-isomerization between a thermally stable

trans (E) state and a meta-stable

cis (Z) state (

Figure 1a). This switching can occur in microseconds with low-power light, and azobenzene-based systems routinely achieve reversibility over 10⁵–10⁶ cycles before fatigue [

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The geometric change at the molecular level can be chemically and physically amplified, enabling reversible modulation of material properties such as phase transitions [

9], phase separation [

10,

11], solubility [

12,

13], and applications in surface patterning and photonics [

1,

14,

15,

16,

17].

The photomechanical effect, where photon absorption and subsequent isomerization induce macroscopic mechanical deformation, was first observed by Merian in 1966, who reported photo-induced shrinkage in nylon fabrics dyed with azobenzene derivatives [

24]. While initial effects were modest (0.1% shrinkage), subsequent research has focused on enhancing photomechanical efficiency in new systems [

25,

26]. More recent work has demonstrated real-time, light-driven expansion and contraction in thin films of azobenzene-containing acrylate polymers, with both irreversible and reversible dimensional changes tracked by techniques such as ellipsometry, atomic force microscopy (AFM), and neutron reflectometry [

17,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Upon initial irradiation, azobenzene polymer films with thicknesses ranging from 25 to 140 nm exhibited an irreversible relative expansion of 1.5–4%. Subsequent cycles of irradiation induced a reversible expansion, with the relative extent of expansion measured at 0.6–1.6%. This behaviour highlights the photomechanical response of azobenzene-containing polymer films, wherein the initial expansion is not recovered, but further light-induced volume changes are reversible upon repeated irradiation cycles [

27].

A major advancement in the field is the use of thin active layers of azobenzene-based polymers deposited onto diverse materials. This approach overcomes the mechanical limitations of pure azobenzene crystals and liquid crystals, which are often brittle and difficult to process [

5,

28,

29]. A seminal demonstration of this concept was provided by Yamada

et al., who showed that thin films of azobenzene-containing polymers could undergo substantial, reversible bending and actuation in response to light, paving the way for light-driven plastic motors. Subsequent work expanded the range of achievable photomechanical motions, including complex three-dimensional deformations [

6,

30]. Thin films can be engineered for mechanical robustness and efficient photomechanical response, and when supported on flexible or mechanically strong substrates, they are capable of inducing significant bending or actuation of the composite structure. Importantly, this effect can occur even when the substrate thickness greatly exceeds that of the active film layer [

4,

5,

28]. The applications of these materials span several advanced technology fields. For example, thin-film azobenzene materials can dynamically alter surface properties such as roughness, wettability, and optical properties in response to light to create adaptive surfaces. This makes them ideal for smart windows, tunable optical devices, and self-cleaning or antifouling coatings [

5,

31]. In soft robotics and artificial muscles applications, photomechanical materials are used to fabricate light-driven actuators, artificial muscles, and grippers. Their fast, reversible, and spatially controllable actuation enables soft robots to move, grasp, or change shape in response to light, eliminating the need for wires or traditional motors. Their mechanical robustness and compatibility with flexible substrates make them suitable for wearable devices, biomedical tools, and micro-robotics [

32]. The precise, remote-controlled actuation of thin-film azobenzene materials is leveraged in microfluidic valves and adaptive biomedical devices, where light can be used to control fluid flow or device configuration without direct contact [

3,

32]. The tuneable photomechanical material also has applications in rewritable photopatterning, optical data storage, security features, and dynamic displays, due to their ability to inscribe and erase surface relief gratings or patterns with light [

14,

15,

33,

34,

35]. As smart membranes and sensors, azobenzene-based thin films can reversibly regulate the diffusion of gases by altering their pore structure or surface properties under light [

31]. These materials can also be used as coatings that, when activated by light, generate mechanical motion to disrupt bacterial biofilms, offering a non-pathogen-specific strategy for maintaining clean surfaces in medical and industrial settings [

3].

To accurately evaluate the bending behaviour and mechanical properties of thin photomechanical layers, microcantilever-based (atomic force) systems can be employed. These systems are highly sensitive to small forces and deformations, allowing for precise measurement of the mechanical response of thin films [

36]. Recent advances in metrology, such as light-associated surface wrinkling-based methods, have further enhanced the ability to quantify changes in modulus and photo softening effects in azobenzene-polymer complexes. These techniques, alongside microcantilever-based systems, provide a comprehensive toolkit for evaluating the photomechanical response, including actuation strength, efficiency, and reversibility [

37].

In this paper, we address the need for robust evaluation of the strength and efficiency of photomechanical azobenzene materials. We introduce a versatile technique for characterizing the photomechanical effects of new photo-functional materials, employing well-characterized flexible substrates (atomic force microscopy (AFM) cantilevers) and microcantilever-based (mica) sensor systems. This approach enables full mechanical characterization of thin photomechanical layers and demonstrates their ability to drive actuation in support structures many times thicker than the active layer.

2. Materials and Methods

Materials: Poly (Disperse Red 1 acrylate) (PDR1A) and Poly (methyl methacrylate-co-Disperse Red 1 acrylate) (P(MMA-co-DR1A)) as shown in

Figure 1b were synthesized according to previously published methodology [

17] with 10 wt% AIBN initiator (Aldrich) and polymerization at 62 °C for 4 days (MW = 3 kg/mol). Poly(Disperse Red 13 acrylate) (PDR13A) was purchased from Aldrich.

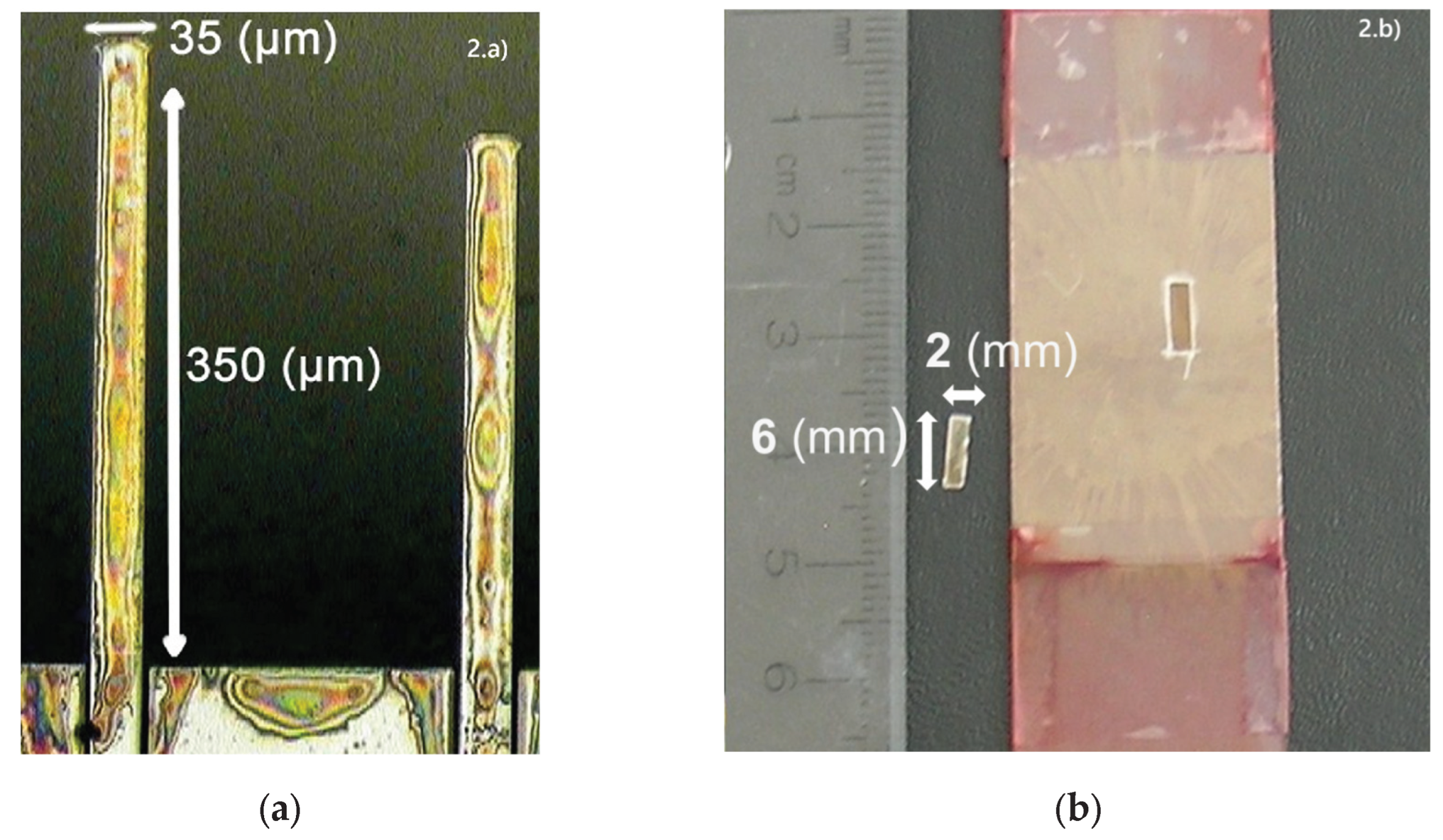

Cantilever Coatings: For the coating of silicon AFM cantilevers (MikroMasch CSC12/tipless/no Al), PDR1A was dissolved in a minimal amount of tetrahydrofuran (THF) or methylene chloride and then ‘painted’ onto the cantilevers under a microscope using solvent resistant paintbrush micro-bristles. The cantilevers were then left to air dry for two hours or more before use. For coating the mica cantilevers, mica sheets (25mm x 50mm x 0.15mm, SPI, V1 grade) were cleaved to a thickness of 30 µm using GEM® Scientific Blades. The sheets were then cleaned by cleaving layers off the top using adhesive tape. Films of PDR1A, PDR13A or P(MMA-co-DR1A) were then spin-cast at 4000 rpm for 90 seconds from polymer concentration 10mg/mL in tetrahydrofuran (THF). The films were annealed under vacuum for 8 h at 90 °C. Finally cantilevers of dimensions in the order of 6mm × 2mm × 30µm were cut from the sheets.

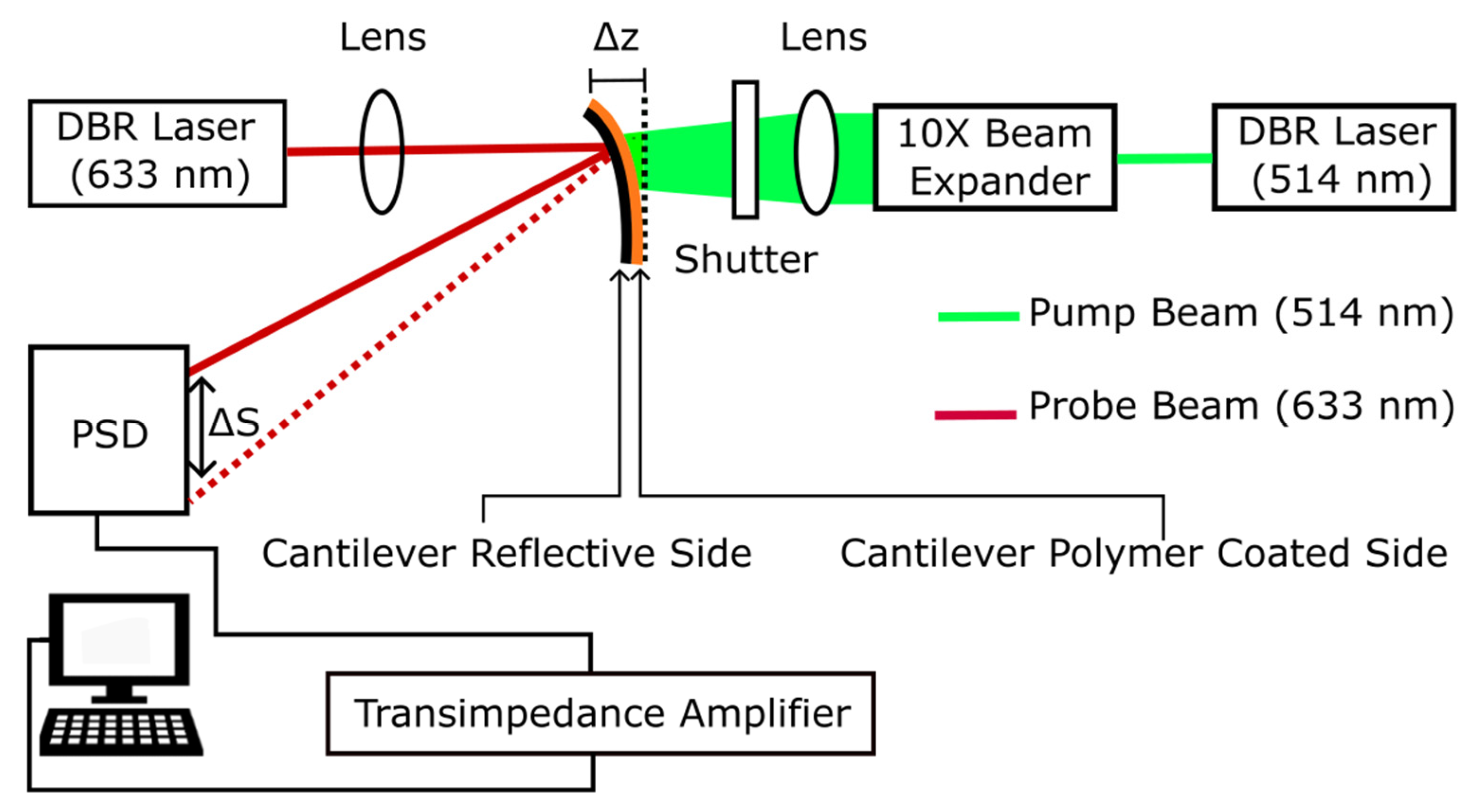

Bending Measurements: Deflection of the silicon cantilevers was measured using a micromechanical AFM cantilever sensor system, as previously described and characterized [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Cantilever bending was induced by illumination from the green line of a tunable Argon gas laser (Melles Griot, 514nm) at an intensity of

100 mW/cm

2. Deflection of mica cantilevers were measured using a micromechanical cantilever sensor system similar in design similar to commercial AFM. The differential microcantilever-based sensor was operated in static mode with microcantilever defections measured using an optical beam, where a low power HeNe laser (JDS Uniphase Model 1136P, 633 nm) was used as the probe beam. The probe beam was focused onto the reflective non-film side surface of the cantilever using a commercial focusing lens (Melles Griot). A position-sensitive detector (PSD, Model 1L10, ON-TRAK Photonics, USA) was placed 6.7 cm away from the cantilever. The pump beam was expanded using a 10× beam expander to achieve a collimated beam with a diameter of approximately 0.40 cm at the cantilever surface. The photocurrents generated at the PSD terminals by the probe beam were converted to voltages using home-built precision transimpedance amplifiers. An electronic shutter was employed to control on/off illumination during the pump cycles. The output voltage

, is directly proportional to the absolute position of the reflected beam on the PSD, according to

. The analog signal was digitized using a 16-bit data acquisition card (National Instruments SCB-68) and recorded on a computer using LabVIEW. The cantilever geometry is shown in

Figure 2, and a schematic representation of the optical detection system is presented in

Figure 3. Measurements recorded were compared to control blanks of illuminated but non-azo-coated cantilevers, which produced no detectable bending at the same power of irradiation.

Use of GenAI: The generative AI GEMA (Amass, accessed on 205/08/15 and 2025/09/04-05) was used for the purposes of text editing with the help of the AI’s writer assistant function. GEMA’s scientific assistant function was used to suggest relevant and up-to-date literature tailored to the research topics, to synthesize and summarize scientific papers, and to generate comprehensive reviews on selected subjects. The output was systematically reviewed and edited by the authors.

3. Results

The microcantilever-based system can measure directly how light-induced molecular stress changes in the azobenzene coating translate into a large-scale mechanical response, specifically the bending of the cantilever’s free end. When the azobenzene molecules undergo geometric photoisomerization under illumination, they generate a surface stress which if sufficient can cause the entire cantilever to bend. The measured deflection of the cantilever tip

can thus provide a direct and quantitative measure of the film’s photomechanical force, power, and efficiency. In this experimental setup, the displacement of the cantilever tip is monitored using a position-sensitive detector (PSD). The PSD produces a voltage signal

that changes linearly with small cantilever deflections. This linear relationship allows the tip deflection

to be calculated from the detector signal using a calibration factor

according to [

38],

where

is the calibration constant (m/V) linking the measured voltage signal from the position-sensitive detector to the actual physical deflection values. For silicon cantilever and optical detector systems

was previously characterized and reported by Tabard- Cossa et al. as

[

38]. Alternatively, this value can also be determined geometrically using an approximation relation derived from beam geometry [38],

where

is the effective length of the microcantilever and

is the distance between the cantilever and the PSD, measured as 6.74 cm. The effective length is defined as the point along the cantilever where the laser beam contacts the surface [

38]. The change in surface stress (∆σ) which is directly proportional to the microcantilever deflection (∆z), can be calculated using the relationship between bending of the cantilever beam and the surface stress difference acting on the two sides [

40].

To quantify the change in surface stress, we employ Stoney’s relation, which links the curvature (or deflection) of the cantilever to the surface stress within the coating [

38]. The corresponding expression is given by

where

is the Young’s modulus,

is the cantilever thickness,

is the cantilever length and

is Poisson’s ratio. Physically, this relation describes how a stress acting on the film surface creates a bending moment that causes the cantilever to curve. A stiffer or thicker substrate produces a smaller deflection for a given surface stress, whereas a softer or thinner substrate yields a larger deflection. This way, Stoney’s relation converts the measured deflection into the film-induced surface stress, quantifying the intrinsic photomechanical response of the active layer, independently of the substrate upon which it is coated. From these direct measurements, one can obtain estimates of the force, power, and efficiency of the transfer of light energy into stress and mechanical energy, even just by basic relationships of cantilever bending covered in most first-year textbooks on mechanics.

The effective spring constant

of a rectangular microcantilever can be expressed as described in [

38] as

with

being the cantilever width. Substituting Equation (4) into Stoney’s relation (Equation 3) yields the commonly used form of the surface stress–deflection relationship, which directly relates the change in surface stress of the coating

to the measured cantilever bending

[

38].

Equation (5) assumes that the probe laser beam is perfectly aligned with the tip (free end) of the cantilever. However, in practice, this is rarely the ideal case. The laser typically reflects from a point slightly before the very end of the cantilever, at the effective length. Because this point is shorter than the total cantilever length, the measured deflection conservatively underestimates the true tip displacement if this geometric offset is not corrected. To account for this, the measured deflection from the PSD can be multiplied by a correction factor, yielding a modified expression for the change in surface stress [

38]:

where Poisson’s ratio

is material dependent. Here, we use

for the single-crystal Si cantilevers, as reported by Tabard-Cossa et al. [

38], and

for muscovite mica cantilevers as reported by Godin et al. [

39]. The factor 4/3 accounts for the fact that a uniform surface stress bends the cantilever differently than a single force acting only at its tip; it corrects point-load calibration to the equivalent response expected for a uniformly stressed beam [38].

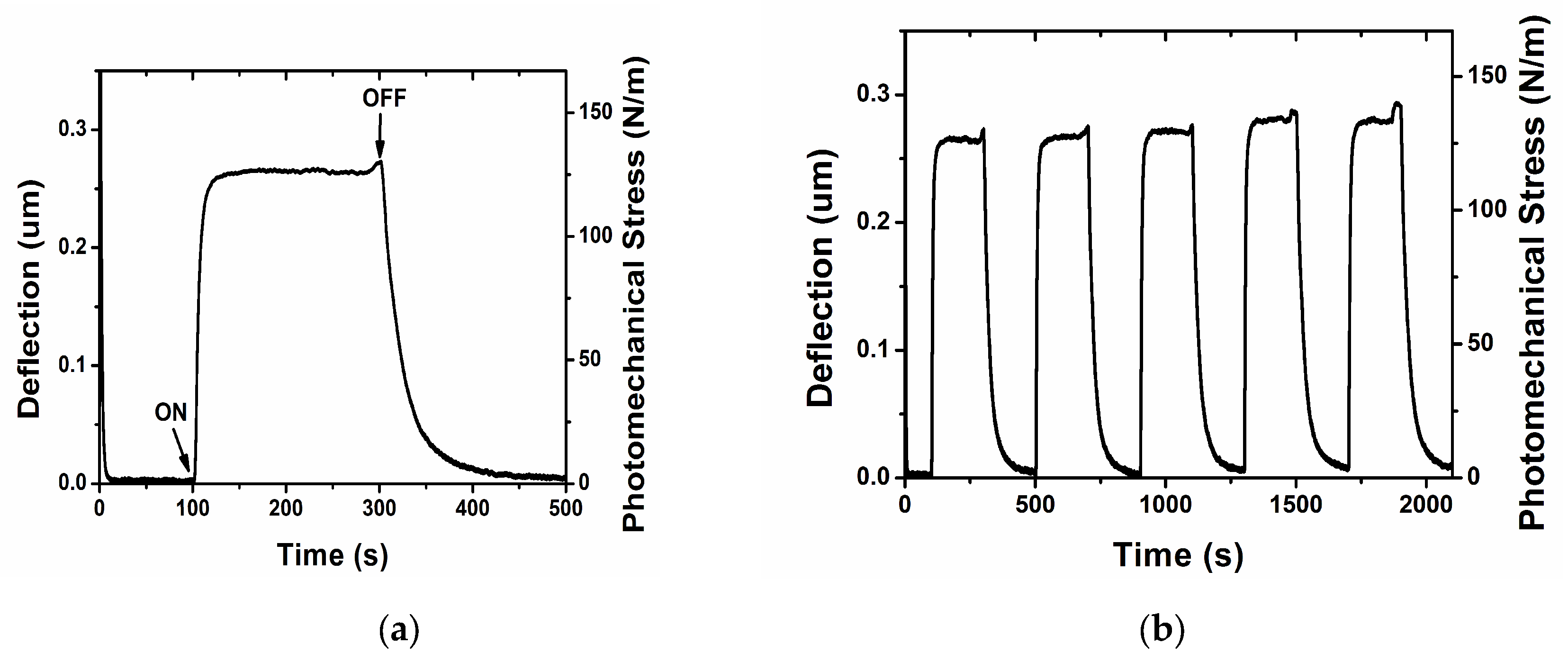

An example of measured deflection and corresponding change in surface stress is presented in the following figures.

Figure 4a shows the deflection and photomechanical stress as a function of time for a silicon cantilever sample irradiated with a pump beam of approximately 100 mW/cm

2 for varying exposure durations. The initial response (characterized by cantilever deformation due to azobenzene photoisomerization) was observed within a few seconds of illumination. The deformation remained stable under continuous irradiation for extended periods (> 200 s) and was reproducible over multiple on/off irradiation cycles (

Figure 4b).

For comparison, a bending measurement output from a mica cantilever is presented in

Figure 5, where both deflection (µm) and corresponding photomechanical surface stress (N/m) are plotted. The sample was irradiated with an 80 mW/cm² pump beam for 50 s and allowed to relax for 100 s (

Figure 5a), while

Figure 5b illustrates the reproducibility of the response over multiple on/off irradiation cycles.

All coatings were prepared using a single solvent preparation system. In order to investigate the effect that the solvent on photomechanical actuation, other solvents were tested (THF vs. methylene dichloride) and variations in deflection, surface stress, and relaxation profiles were measured, with only insignificant variations in relaxation behaviour and baseline stability between samples, perhaps attributed to just differences in film quality. Because the polymer solution was manually applied to one side of the cantilever, the resulting coatings may not have been uniformly thick, fully dry, or consistent across samples, making it difficult to reproduce identical film properties. Despite these inconsistencies, the clear and reversible bending response demonstrates that the PDR1A films exhibit a strong photomechanical effect and that the cantilever setup is suitable for quantitatively assessing the photochemical performance of azobenzene-based polymers.

To address these challenges, we fabricated larger cantilevers from muscovite mica. The increased surface area and mechanical robustness of the mica substrates enabled the use of more controlled deposition techniques such as spin casting, providing more reliable control over film thickness to achieve reproducibility and uniformity, and a much larger bending. The cantilever deflection and corresponding change in surface stress were evaluated using Equations 2 and 3, respectively, with the effective spring constant determined from Equation 4, as described by Tabard-Cossa

et al. [

38]. As expected, more consistent photomechanical responses across multiple samples were obtained using mica cantilevers and spin-cast polymer coatings. More consistent amplitudes were observed, and drifting during on–off modulation cycles was reduced.

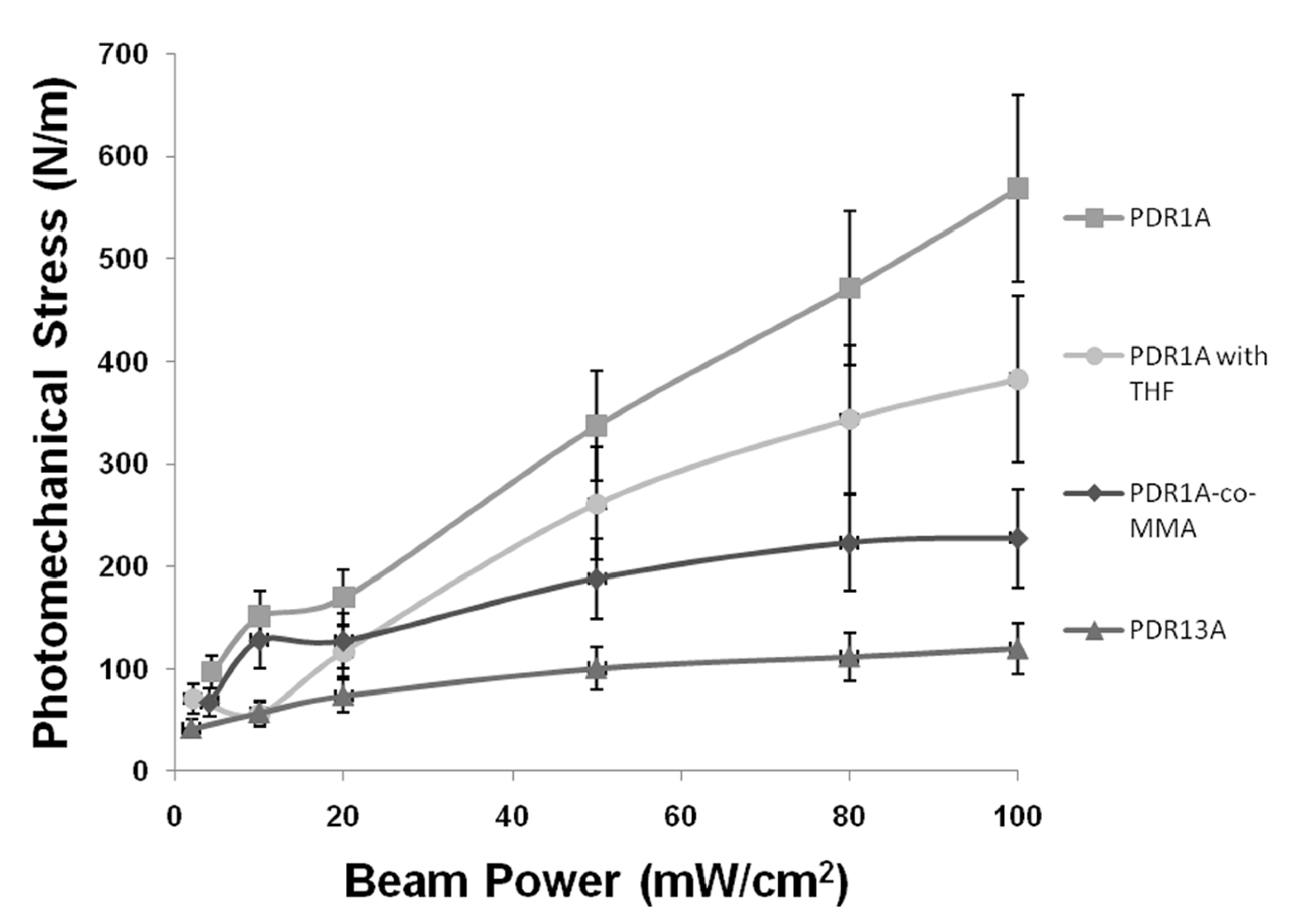

In order to highlight the capability of the cantilever-based method to sensitively characterize a broad range of azobenzene polymer system, we systematically evaluated the influence of coating material properties and external condition on the magnitude of the photomechanical effect in azobenzene polymers, using three key variables: (1) pump beam power, (2) chemical modification of the polymer main chain or chromophore, and (3) the presence of residual solvent. In practice, mica cantilevers were coated with polymer variations of PDR1A, PDR13A and PMMA-co-PDR1A, and the photomechanical stress was recorded with increasing beam power. To evaluate the effect of residual solvent, a PDR1A-coated cantilever was tested without oven-drying (a “wet” sample) immediately after spin casting. Presented in

Figure 6, the measured cantilever deflections were converted to surface stress using the Stoney relation.

As illustrated in

Figure 6, photomechanical stress increased with pump beam power for all coatings. This trend aligns with the established mechanism whereby higher light intensities promote greater

trans–cis isomerization in azobenzene films [

41,

42]. Cantilever deflections reached ~150 µm, corresponding to surface stresses up to ~600 N m

-1. The maximum pump intensity was limited to the usual 100 mW/cm² to minimize thermal contributions to cantilever bending and to prevent any photo-damage or dye photobleaching.

Finally, to assess the ability of each coating to convert absorbed photo-energy into mechanical stress, the photomechanical efficiency of the samples was calculated. The optical energy absorbed by the active layer was estimated from the incident light intensity

100 mW/cm

2 and the time required to reach equilibrium (maximum stable deflection), using the relation

, and an absorption coefficient of 4.3 µm

-1 at 514 nm, to determine the light energy absorbed through the Beer- Lambert Law [

21]. The output photomechanical energy, representing the elastic energy stored in the cantilever due to light-induced surface stress (corresponding to the mechanical work produced by illumination), was determined using Equation 7 [

39],

where

υ represents the Poisson ratio (

for muscovite mica cantilever)s [

39,

40]. To compare the photomechanical performance of the different polymer coatings, the photomechanical energy was expressed as energy density. To obtain the photomechanical energy density, the film volume was estimated geometrically from the known surface area of the coated cantilever and the measured film thickness of 100 nm. Since the films’ thickness is significantly less than the optical absorption length of the azobenzene polymers at 514 nm (~230 nm, given by 1/α, the inverse of the absorption coefficient, α = 4.3 µm⁻¹), and likely mostly reflected back into the film from the cantilever surface, it was assumed that the incident light was absorbed uniformly throughout the film thickness.

Table 1 summarizes the calculated values for absorbed optical energy, photomechanical energy, film volume, efficiency and energy density obtained from the photomechanical responses of mica cantilevers coated with 4 different azo dye polymers.

Across all illumination intensities, PDR1A exhibited the strongest photomechanical response, followed in decreasing order by the THF processed PDR1A film, the copolymer P(MMA-co-DR1A), and PDR13A, which showed the lowest stress generation. This ranking indicates that both residual solvent and chemical modification of the chromophore or backbone reduce the efficiency of stress generation. Previous studies have demonstrated that the mechanical response of azobenzene-containing polymers is influenced by the viscoelastic nature of the matrix and its elastic modulus [

20,

41]. The reduced stress observed in the THF-processed films is likely due to residual solvent acting as a plasticizer, which softens the material and lowers its elastic modulus. Softer films allow increased internal molecular motion but are less efficient at transferring surface stress to the substrate, resulting in smaller cantilever deflections, even though photoisomerization within the film continues to occur [

20,

27,

42]. As discussed by Barrett

et al. and Ikeda

et al., factors such as polymer cross-linking and residual solvent content can influence the efficiency of photomechanical energy transduction [

20,

42]. Interestingly, the bending process measured here appears to be more efficient, as indicated by the higher calculated photomechanical efficiency of the wet PDR1A sample (0.00060%) compared to the dry film (0.00045%), even though the THF-processed film shows a smaller deflection. When incident light causes stress to the azobenzene molecules in the film, only a fraction of the absorbed energy is used for the bending of the cantilever, while a large portion remains within the film through viscoelastic losses; the energy is either stored temporarily inside the film (corresponding to higher internal strain within the softened film) or lost as friction or heat. This energy loss results in lower surface stress on the cantilever and therefore smaller deflection.

The copolymer P(MMA-co-DR1A) produced a smaller absolute deflection, as was expected, since it contains only 15 mol % chromophore and therefore a lower concentration of photomechanical azobenzene drivers compared to PDR1A [

18,

42]. Interestingly, however, P(MMA-co-DR1A) exhibited a slightly higher energy-conversion efficiency (0.00074%). This could be explained by the fact that diluting azobenzene within the PMMA matrix increases the intermolecular separation and available free volume, leaving space for each absorbed photon to cause a fully effective conformational change. As a result, the energy-conversion efficiency is enhanced even with a reduced number of chromophores present in the active layer [

18,

19,

20,

42].

As shown in

Figure 6 and summarized in

Table 1, PDR13A exhibited the lowest deflection value. This could be due to the addition of a chlorine (Cl) atom to the chromophore rings (

Figure 1ii), which introduces molecular asymmetry and steric hindrance. These effects might reduce the planarity of the molecule and decrease the overlap of the (–N=N–) π orbitals, thereby lowering both the light-absorption capability and the isomerization efficiency. Consequently, this film displays the lowest energy-conversion efficiency (0.00024%) and lowest deflection values among all polymer coatings tested. This observed reduction in the photoresponsivity in consistent with literature reports showing that ortho-chloro institution in azobenzene’s induces steric congestion and twisting of the aromatic tings, weakening π- conjugation [

43] and perhaps consequently the photoisomerization efficiency.

When comparing substrates, the time-dependent traces of PDR1A coatings on silicon cantilevers followed the same qualitative trend as those on mica cantilevers, but showed smaller absolute deflections. This behaviour is consistent with the higher spring constant and mechanical stiffness of silicon compared to mica. These results support that the observed response arises from the photomechanical activity of the coating itself, rather than from differences in the substrate’s mechanical properties.

4. Discussion

The results demonstrate that microcantilever sensors coated with azobenzene containing polymers can function as highly sensitive platforms for quantifying light induced bending and associated photomechanical response. Cantilever deflections ranged from ~0.25 µm for silicon substrates to ~150 µm for mica, indicating that nanoscale

trans–cis isomerization of the azobenzene coating generates substantial internal stress within the polymer matrix, which is efficiently transmitted to the cantilever and results in measurable deflection. These magnitudes are consistent with previously reported values for azobenzene thin film actuators operating in similar static (Stoney-type) configurations [

41,

42].

Of all samples tested, PDR1A exhibited the highest surface stress generation and deflection amplitudes, while the THF-processed and chemical variants PDR13A, P(MMA-co-DR1A)) showed diminished responses due to plasticization, steric hindrance, and reduced chromophore density. However, the THF-processed and P(MMA-co-DR1A) copolymer samples displayed increased photomechanical efficiency, suggesting that even if the total surface stress transmitted to the cantilever is reduced, internal molecular isomerization within the film may occur more effectively. In these films, the presence of residual THF solvent or the incorporation of a PMMA matrix in the copolymer increases the free volume between polymer chains and reduces intermolecular constraints. This additional space could allow azobenzene chromophores to undergo a higher yield

cis-trans conformational change with fewer restrictions. At the same time, localized viscoelastic relaxation may well enable the surrounding polymer segments to accommodate this shape change rather than resist it. As a result, less stress is transferred to the substrate, leading to smaller deflection, and a greater fraction of the absorbed optical energy is internally converted into mechanical strain within the film itself [

18,

20].

Although mica cantilevers exhibited greater absolute deflection than silicon, the calculated surface stress in the coating was similar for both substrate types. This confirms that surface stress is intrinsic to the polymer film and primarily determined by molecular orientation and viscoelastic properties, while deflection amplitude depends on the cantilever’s mechanical stiffness. Mica’s lower spring constant allows the same surface stress to produce larger curvature, whereas silicon’s far higher modulus limits its deflection. Thus, the enhanced bending observed with mica reflects a more efficient mechanical transduction due to the substrate’s lower rigidity, rather than a stronger photomechanical effect in the film itself.

The bending response was rapid, fully reversible, and could be cycled repeatedly without significant fatigue, confirming the mechanical stability and robustness of azobenzene-based actuation, in agreement with previous reports [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Despite limited efficiency, the photomechanical energy density reached up to 765 mJ/mm³, which is substantial for thin film actuators and comparable to or higher than those reported for other light-responsive polymer systems [

43]. This demonstrates that even a modest fraction of converted optical energy can generate mechanically significant work at the microscale, reinforcing the potential of azobenzene film coatings for integrated optomechanical and photonic devices.

The observed bending arises from differential surface stress generated by the azobenzene film upon illumination. The magnitude of bending depended on polymer composition and residual solvent content, highlighting the importance of film uniformity, thickness, and mechanical coupling between the coating and substrate. Variability in coating quality, especially with hand-painted films on silicon cantilevers, resulted in notable sample-to-sample differences, emphasizing the need for controlled deposition techniques such as spin coating, which produced uniform and reproducible coatings on mica cantilevers.

Residual solvent was found to reduce effective surface stress upon illumination, as solvent molecules act as plasticizers, lowering the film’s elastic modulus and increasing molecular mobility. During

trans–cis isomerization, these mobile chains can reorganize and relax internal stresses more readily, allowing much of the photoinduced strain to dissipate within the film rather than being efficiently transferred to the substrate. As a result, overall cantilever bending decreases, even though the extent of molecular photoisomerization remains similar. This behaviour is consistent with previous studies showing that plasticization or swelling in azobenzene-based polymers likely softens the matrix and reduces photomechanical transduction efficiency [

18,

20]. Chemical modification, such as the introduction of bulky Cl substituents, increases steric hindrance and distorts the planarity of the azobenzene group, reducing π orbital overlap and the probability of light-induced isomerization, which may well have lead to diminished photomechanical output, as expected [

43].

The ability to tune photomechanical response through polymer composition, chromophore content, and processing conditions highlights the versatility of azobenzene-based materials for designing light-driven micro-actuators and sensors. The quantitative analysis of surface stress and energy conversion efficiency presented here provides a framework for comparing different azobenzene materials and optimizing their performance. Further improvements in film uniformity, thickness control, and chromophore density are expected to yield greater actuation magnitudes and improved efficiencies. Future work could aim to correlate the molecular structure and dynamics of azobenzene polymers with their macroscopic mechanical output, ideally through combined spectroscopic and mechanical characterization. Additionally, systematic studies of long-term stability, fatigue resistance, and environmental response will be essential for advancing these materials toward practical applications.