1. Introduction

Agritourism has become an increasingly important component of rural tourism and regional development, reflecting a broader shift in visitor preferences toward authenticity, locality, and immersive experience consumption. Recent studies indicate that agritourism contributes to farm income diversification, enhances community resilience, and strengthens local food systems, while generating distinctive forms of experiential value not typically found in urban leisure settings [

1,

2]. Unlike conventional tourism environments, agritourism is shaped by seasonal rhythms, human–land relationships, agricultural labor, and environmental variability, creating an experiential structure that is both heterogeneous and context dependent. In Taiwan, the institutionalization of leisure agriculture parallels global trends, yet empirical understanding of how agritourism experiences translate into perceived value and satisfaction within authentic farming contexts remains limited. The hybrid nature of agritourism—combining natural landscapes, labor practices, cultural traditions, and rural social interaction—poses important theoretical challenges for experience research and warrants deeper examination of its underlying psychological mechanisms.

Within the broader evolution toward the experience economy [

3], experiential marketing provides a structured framework for understanding how sensory, affective, cognitive, behavioral, and relational components shape visitor responses [

4]. Evidence from tourism studies confirms that these experiential modules influence both perceived value and behavioral intentions [

5]. However, agritourism differs fundamentally from constructed or engineered experience spaces—such as theme parks—in which environmental stimuli and visitor pathways are carefully controlled. In contrast, agritourism experiences arise from natural variability, authentic farm work, local social relations, and embodied engagement with rural settings [

6]. This makes agritourism an important empirical setting for assessing the applicability of the Strategic Experiential Modules (Sense, Feel, Think, Act, Relate) to authenticity-based and labor-intensive tourism contexts. Despite growing interest, limited research has systematically evaluated how experiential marketing translates into perceived value and satisfaction in agritourism, leaving key theoretical and managerial questions insufficiently addressed.

The Memorable Tourism Experience (MTE) framework provides a complementary theoretical lens for understanding how emotional and cognitive processes generate lasting experiential outcomes [

36]. Although MTE has been widely applied in nature-based, food, and cultural tourism [

7], its application to agritourism remains underexplored, despite the high potential of farm-based activities, local interaction, and rural landscape immersion to create memorable experiences. Prior studies have identified links among experience quality, perceived value, and satisfaction in rural tourism [

8,

9], but the psychological mechanisms connecting these constructs have rarely been integrated within a coherent MTE-informed framework.

In East Asian contexts, agritourism demand is largely driven by urban residents seeking experiential contrast from everyday life. Rural novelty, landscape aesthetics, and hands-on agricultural participation have been shown to enhance emotional response, well-being, and place attachment [

6,

10]. This cross-lifeworld contrast underscores the conceptual relevance of applying experiential marketing to agritourism. At the same time, destination management organizations (DMOs) have become increasingly involved in agritourism governance through branding, route development, certification schemes, and local food initiatives [

11,

12], yet their influence on experience formation has seldom been incorporated into empirical models.

Addressing these gaps, this study develops and tests an integrated structural equation model linking agritourism experience, perceived value, and satisfaction, grounded in experiential marketing and MTE theory. The study contributes by (1) validating the applicability of experiential modules in authentic agricultural environments, (2) proposing an MTE-informed model of agritourism experience formation, and (3) identifying the value formation mechanisms through which agritourism experiences influence satisfaction. These insights provide theoretical advancement for experience research and practical guidance for agritourism operators and DMOs in designing culturally embedded and value-driven rural tourism experiences.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Foundations and Recent Developments in Agritourism

Agritourism has emerged as a key strategy for rural revitalization, farm income diversification, and sustainable local development worldwide. It generally refers to tourism activities that take place on farms and integrate agricultural production, rural landscapes, and direct interactions between visitors and farmers [

13]. Recent scholarship conceptualizes agritourism not merely as a leisure activity but as a socio-cultural space in which visitors, farmers, and local communities co-produce meanings associated with food, agriculture, and rural identity [

14].

Studies published after 2018 increasingly emphasize the distinctions between agritourism and artificially constructed leisure environments. Agritourism experiences are shaped by authenticity, seasonality, natural rhythms, and the materiality of farm work, and are characterized by highly experiential, place-specific learning and participation [

15]. Research across Southern and Northern Europe, North America, and East Asia consistently shows rising demand for farm-based engagement, food-related interactions, and immersive learning, all of which enhance visitors’ sensory and emotional involvement [

9,

14,

16].

In Asia, agritourism has expanded rapidly in Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, typically through small, family-operated farms emphasizing local food, community culture, and environmental education [

17,

18]. Taiwan’s leisure agriculture system is one of the most institutionalized in the region, currently comprising more than one hundred officially designated leisure agriculture areas [

19,

20]. Despite this institutional development, empirical research examining how experience design shapes visitor evaluations remains limited—particularly quantitative models integrating experiential marketing, perceived value, and satisfaction. Understanding the mechanisms through which experiential elements influence agritourism evaluations therefore represents an important research gap.

2.2. Experiential Marketing in Tourism: Theoretical Developments and Rural Applications

Experiential marketing has become a foundational framework in tourism research for understanding sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational elements of visitor experience. Schmitt’s Strategic Experiential Modules (SEM)—Sense, Feel, Think, Act, and Relate—provide the conceptual basis for analyzing how marketing stimuli shape experiential responses [

4]. Recent tourism studies, however, expand beyond Schmitt’s framework to consider immersive environments, co-creation, emotional connectedness, and social interaction as deeper determinants of experiential value [

21].

Current evidence highlights sensory richness, emotional resonance, and social interaction as critical drivers of satisfaction and loyalty [

22]. Memory-oriented studies further show that experiential cues play a central role in forming Memorable Tourism Experiences (MTEs), which in turn shape revisit intention [

23].

Despite its theoretical relevance, experiential marketing has been applied only sparingly in agritourism contexts. While existing studies recognize authenticity, social interaction, and hands-on participation as defining features of rural tourism, few have quantitatively operationalized Schmitt’s SEM model in farming environments. Liang et al. find that in rural settings, the Relate and Act dimensions tend to be more influential than in urban leisure environments because rural tourism relies heavily on community interaction and bodily engagement in agricultural activities [

24].

Extending experiential marketing to agritourism therefore requires examining how rurality—such as natural environments, seasonal rhythms, local culture, and farmer interaction—reshapes experiential mechanisms. This study contributes to this line of inquiry.

2.3. Perceived Value and Tourist Satisfaction: Multidimensional Structure and Recent Evidence

Perceived value remains a central construct in tourism behavior research, reflecting the visitor’s overall evaluation of trade-offs between what is given and what is received [

25]. Contemporary perspectives emphasize its multidimensional nature, incorporating emotional, functional, social, monetary, and effort-based components [

26,

27]. Studies published after 2019 increasingly stress the importance of emotional and social value in experience-based and nature-based tourism [

8].

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates that perceived value is a key predictor of satisfaction, loyalty, and revisit intention. Recent research shows that perceived value often acts as a mediator linking experiential elements—such as sensory immersion, emotional engagement, and authenticity—to satisfaction [

28]. Empirical studies also indicate that when visitors experience meaningful social interaction, cultural learning, or personal growth during a trip, their overall value assessment increases significantly [

8].

Findings in agritourism exhibit similar patterns. Suhartanto et al. report that emotional and educational elements in rural homestays and farming activities strongly influence perceived value [

29]. Kastenholz et al. and Liang find that agricultural participation enhances both emotional and cognitive value, which in turn improves satisfaction [

16,

24].

Despite these insights, agritourism research still lacks an integrated theoretical model linking experiential marketing, perceived value, and satisfaction. This study addresses this important gap by proposing a quantitative, empirically testable framework.

2.4. Conceptual Framework

Agritourism provides a distinct form of experiential consumption that integrates sensory immersion, emotional engagement, cognitive stimulation, and social interaction. As discussed above, experiential marketing plays a central role in shaping rural tourism experiences, particularly through sensory stimuli, emotional resonance, and participatory engagement. These experiential elements influence not only immediate affective reactions but also visitors’ perceived value—a multidimensional construct encompassing emotional, functional, social, and monetary components [

26,

27].

Recent empirical studies suggest that perceived value is an important psychological mechanism linking tourism experiences to downstream outcomes such as satisfaction, loyalty, and revisit intention. In experiential and nature-based tourism contexts, factors such as meaningful interaction, authenticity, and emotional involvement enhance perceived value, which subsequently increases satisfaction [

8]. This mediating effect has also been documented in rural and agritourism settings [

29,

30].

Based on these insights, the present study proposes an integrated framework examining the causal relationships among agritourism experience, perceived value, and satisfaction. Agritourism experience is expected to exert both direct and indirect effects on satisfaction, with perceived value serving as the mediating mechanism. This conceptualization is consistent with experiential consumption literature, which posits that consumer evaluations arise from both immediate affective responses and subsequent value appraisal [

23].

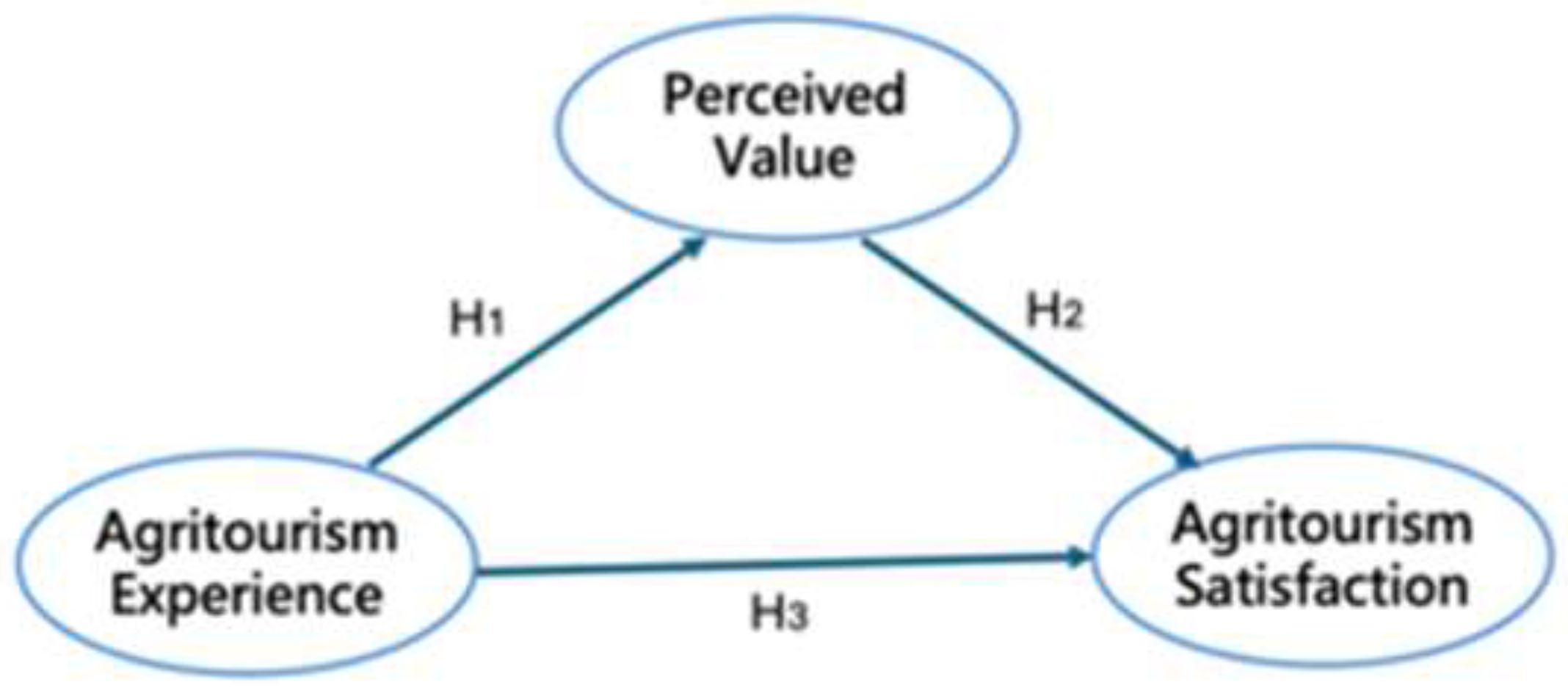

In this study’s conceptual model (

Figure 1), the experiential components derived from Schmitt’s (1999) SEM framework constitute the primary sources of agritourism experience. These experiences are hypothesized to enhance perceived value (H1) and directly influence satisfaction (H3). Perceived value is also proposed as a positive antecedent of satisfaction (H2), consistent with its role in visitors’ overall cost–benefit evaluations [

25].

Figure 1 integrates insights from theory and empirical research and forms the basis for the hypotheses and structural equation modeling presented below.

2.5. Hypotheses Development

The conceptual framework indicates that agritourism experience influences visitor satisfaction both directly and indirectly through perceived value. Drawing on the literature reviewed in this chapter, this study proposes the following hypotheses.

2.5.1. Agritourism Experience on Perceived Value (H1)

Prior research consistently shows that experiential quality is a major determinant of perceived value. Schmitt’s SEM model identifies sensory, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and relational components as core elements shaping experiential depth [

4]. Subsequent studies demonstrate that in tourism, leisure, and nature-based activity contexts, these experiential components significantly enhance emotional, functional, and social value assessments [

26,

27].

In agritourism contexts, immersive engagement through hands-on agricultural activities, cultural interaction, and natural environment exposure fosters emotional resonance, place attachment, and a sense of learning, thereby enhancing perceived value [

5,

29]. Recent findings also indicate that rurality and authenticity positively influence perceived value through interactive experiences. Thus, richer agritourism experiences are expected to result in higher perceived value.

H1: Agritourism experience positively influences perceived value.

2.5.2. Perceived Value on Agritourism Satisfaction (H2)

The positive relationship between perceived value and satisfaction has been firmly established in tourism literature. Zeithaml conceptualizes perceived value as the consumer’s overall evaluation of the give–get trade-off, whereas satisfaction reflects the affective response to this evaluation [

25]. Studies show that when visitors perceive high emotional, functional, social, or monetary value, satisfaction increases significantly [

31,

32].

In experiential and nature-based tourism, perceived value is one of the strongest predictors of satisfaction, especially when experiences deliver learning, meaningful engagement, or emotional rewards [

8]. In agritourism, both Loureiro and Suhartanto et al. confirm that perceived value is a central determinant of visitor satisfaction [

5,

29]. Toeh, Wang and Kwek further emphasize the explanatory power of affective value assessments in experiential tourism [

28].

H2: Perceived value positively influences agritourism satisfaction.

2.5.3. Agritourism Experience on Agritourism Satisfaction (H3)

Beyond its indirect effect through perceived value, agritourism experience may also directly enhance satisfaction. Studies by Rahmawati & Kusumawati and Sharma et al. show that sensory and emotional experiences can generate immediate pleasure and satisfaction even prior to cognitive appraisal [

23,

32]. Volo similarly argue that immersive and affective experiences can elicit satisfaction independently of value judgments [

33].

Agritourism activities are highly interactive, enabling visitors to experience emotional fulfillment and positive sensory stimulation through farm work, cultural participation, and encounters with farmers. These experiences can directly elevate visitors’ overall evaluations, independent of perceived value [

15].

H3: Agritourism experience positively influences agritourism satisfaction.

Building on the theoretical foundations reviewed above, this study adopts an empirical approach to examine how agritourism experiences influence perceived value and satisfaction within authentic farming contexts. The conceptual framework and hypotheses highlight a set of latent constructs—experiential dimensions, value perceptions, and satisfaction—that require rigorous measurement and structural validation. Given the multidimensional nature of these constructs and the mediating processes proposed, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) provides an appropriate analytical strategy for testing the relationships among them. The following section outlines the research design, sampling strategy, measurement instruments, and analytical procedures employed to evaluate the conceptual model. By establishing a robust methodological foundation, the study seeks to provide empirical evidence that advances theoretical understanding and offers practical insights for agritourism development and rural sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Sampling Procedure

Taiwan provides a well-established institutional environment for agritourism research, with more than one hundred leisure agriculture areas formally designated by the Ministry of Agriculture. These destinations operate under standardized administrative guidelines, offering a suitable context for examining experiential mechanisms within authentic farming settings. From the national registry, twelve agritourism communities were purposively selected to ensure variation across geographical location, dominant agricultural production (e.g., rice, tea, fruit, mixed farming), and the diversity of experiential activities available.

Two criteria guided site selection:

formal registration as a leisure agriculture or agritourism destination, ensuring institutional comparability; and

provision of at least two visitor-participatory activities, such as harvesting, food processing, guided farm walks, or ecological learning experiences.

Data collection occurred on-site between May and June 2024 using a visitor-intercept survey approach. Respondents were visitors who had completed at least one agritourism activity. Although convenience sampling was adopted—commonly used in field-based tourism and agricultural experience research—sampling bias was mitigated through systematic data collection across weekdays/weekends and morning/afternoon periods. Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and based on informed consent.

A total of 413 questionnaires were collected, of which 398 were retained after removal of incomplete cases. Missing values accounted for less than 5% of the dataset and showed no systematic pattern; thus, listwise deletion was applied. Respondent demographics are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Measurement Instruments

The questionnaire consisted of three validated multi-item scales—experiential marketing, perceived value, and satisfaction—supplemented by demographic items. All constructs were measured using a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

Experiential marketing was measured using Schmitt’s Strategic Experiential Modules (SEM), including Sense, Feel, Think, Act, and Relate [

4]. Items were adapted to reflect agritourism conditions and were subjected to content validation procedures. The final scale contained twelve items.

Perceived value was measured using the multidimensional frameworks of Sweeney & Soutar and Petrick, comprising quality, emotional response, monetary cost, behavioral cost, and reputation [

26,

27]. These dimensions have been validated in recent tourism and agricultural experience studies [

29,

30]. The final perceived value scale contained ten items.

Satisfaction was measured using a three-item scale reflecting overall evaluative judgment, grounded in Oliver’s satisfaction framework [

39]. To ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence, all items underwent forward translation and back-translation following Brislin’s guidelines [

40].

3.3. Data Quality Assurance and Control for Common Method Variance

To minimize potential common method variance (CMV), the study implemented several procedural controls: respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, item order was randomized to reduce response patterns, and experiential items were separated from evaluative items to avoid priming.

Post hoc statistical assessments were also conducted. Harman’s single-factor test indicated that no single factor accounted for a majority of variance (< 40%). A single-factor confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model exhibited poor fit, further suggesting that CMV did not substantially influence the results. Incorporating CMV diagnostics aligns with methodological best practices in quantitative agricultural and tourism research.

3.4. Preliminary Statistical Diagnostics

Prior to estimating the structural equation model, preliminary diagnostic checks were conducted. Skewness and kurtosis values for all constructs were within acceptable thresholds (|skewness| < 2; |kurtosis| < 7), supporting the use of maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Sampling adequacy was confirmed with a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.921, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < .001), indicating that the dataset was suitable for factor analytic procedures.

3.5. Data Analysis Strategy

The study followed the two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) approach recommended by Hair et al. (2019). SEM was selected because the research model includes multiple latent variables and hypothesized direct and indirect effects that require simultaneous estimation.

Step 1: Measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α, Composite Reliability), convergent validity (Average Variance Extracted), and discriminant validity [

35].

Step 2: Structural model. Path analysis was performed to test the hypothesized relationships among experiential marketing, perceived value, and satisfaction. Model adequacy was evaluated using multiple fit indices, including χ²/df, CFI, TLI, GFI, and RMSEA, consistent with SEM reporting standards.

Mediation analysis employed non-parametric bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples; indirect effects were evaluated using 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals.

The study obtained human-subjects ethical approval from the authors’ institution, and all respondents provided informed consent.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

The analysis followed a two-step Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach. The first step involved evaluating the measurement model to assess the reliability and validity of the latent constructs, including indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The second step estimated the structural model to test the hypothesized relationships and overall model fit.

Regarding indicator reliability, standardized factor loadings for all items were examined. One item exhibited a loading below the acceptable threshold of 0.593 and was therefore removed from the model (see

Table 2). Composite Reliability (CR) was subsequently calculated, as CR provides a more accurate estimate of internal consistency for latent constructs than Cronbach’s α. As shown in

Table 3, all constructs achieved CR values above 0.674, indicating satisfactory reliability.

For convergent validity, all constructs demonstrated Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values greater than 0.50, indicating that the variance explained by the items exceeded the measurement error and therefore met the standard criteria for convergent validity. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion, which compares the square root of each construct’s AVE with its correlations with other constructs. As shown in

Table 3, the square root of each AVE exceeded the corresponding inter-construct correlations, confirming satisfactory discriminant validity.

Overall, the measurement model demonstrated adequate reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, supporting its suitability for subsequent structural path analysis and hypothesis testing.

4.2. Overall Model Fit

Following data collection, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement scales used in the study. According to the guidelines proposed by Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), overall reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for attitudinal or perceptual scales should exceed 0.80, while subscale reliabilities should surpass 0.70; values between 0.60 and 0.70 are considered acceptable in exploratory contexts. In this study, the reliability coefficients of all scales exceeded 0.87, and subscale reliabilities ranged from 0.67 to 0.89, indicating satisfactory internal consistency.

In line with recommendations by Bagozzi & Yi, multiple indices were used to evaluate the overall model fit [

34]. The seven fit indices examined included the chi-square statistic (χ²), the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df), the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index (AGFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

The fit indices are summarized in

Table 4. As suggested by Bagozzi and Yi, χ²/df values below 3 indicate acceptable fit [

35]; the value obtained in this study was 2.52, meeting the required standard. Hair et al. recommend that GFI and AGFI values approach 1 [

38]; in this study, GFI = 0.90 and AGFI = 0.87, both of which demonstrate good fit. The CFI value of 0.95 exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating excellent comparative fit. Finally, the RMSEA value of 0.06 was below the recommended cutoff of 0.08 (Hair et al. 1998), suggesting satisfactory approximate fit.

Overall, the results indicate that the measurement model achieved satisfactory fit across all indices, demonstrating adequate theoretical and empirical support. The model exhibits strong explanatory power and statistical stability, providing a sound basis for subsequent hypothesis testing and structural model evaluation.

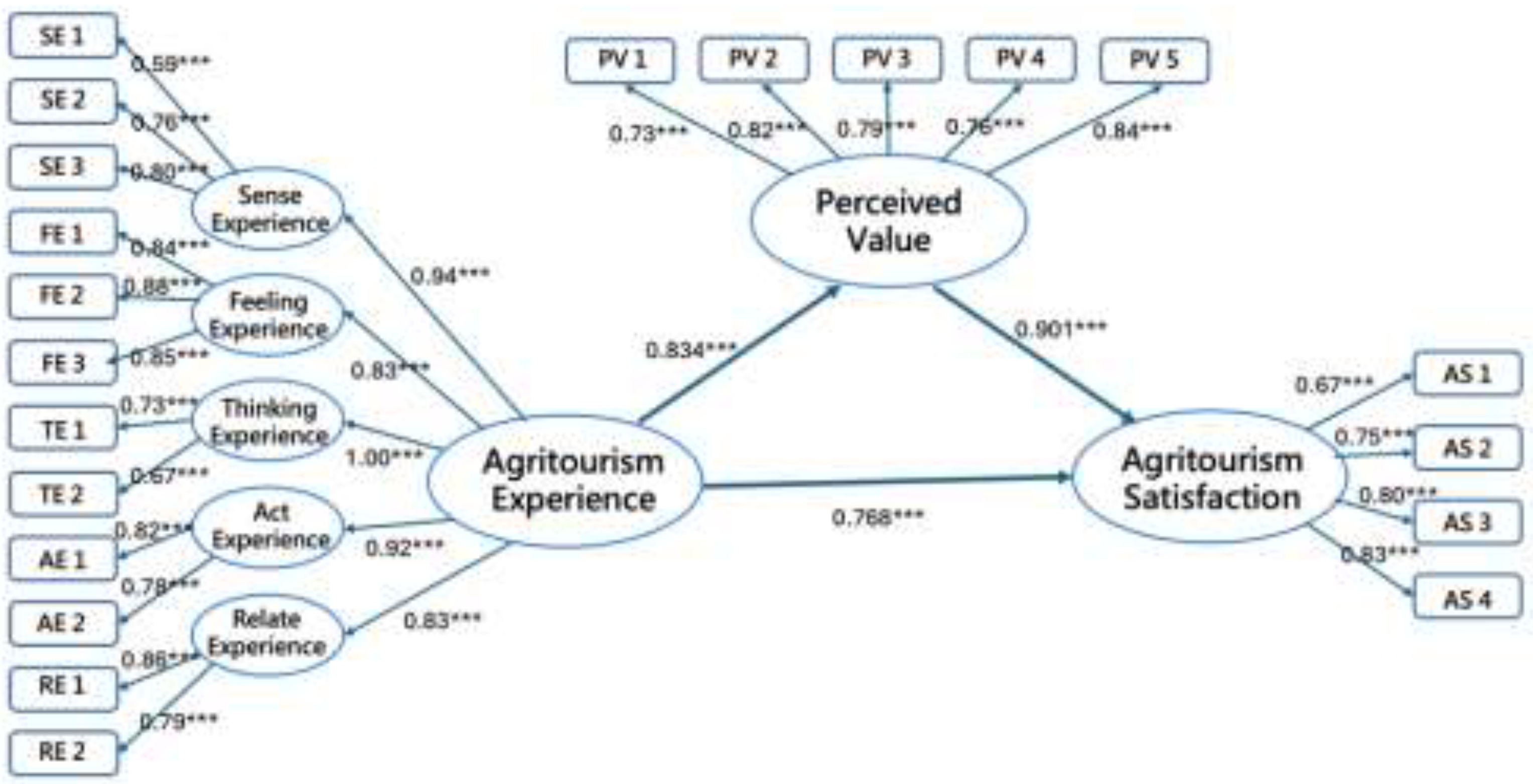

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

After confirming that the measurement model demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity, the structural model was evaluated to examine the estimated path coefficients and their statistical significance. To obtain robust parameter estimates, non-parametric bootstrapping was employed (sample size N = 398, with 5,000 resamples). Standardized path coefficients, standard errors, and t-values were computed accordingly.

The results of the structural model are presented in

Table 5. All three hypotheses proposed in this study were supported. First, agritourism experience exerted a significant positive effect on perceived value (β = 0.834,

p < 0.01), supporting H1. Second, perceived value had a significant positive influence on visitor satisfaction (β = 0.901,

p < 0.01), providing support for H2. Third, agritourism experience also exhibited a significant direct effect on satisfaction (β = 0.768,

p < 0.01), confirming H3.

In addition, all subdimensions of the agritourism experience construct demonstrated significant factor loadings on their corresponding latent variable, indicating strong indicator representativeness. The loadings of each subdimension and the full structural relationships of the proposed model are illustrated in

Figure 2. Notably, agritourism experience and perceived value showed a high degree of association. Although experiential marketing remains an important determinant of agritourism satisfaction, the perceived value formed through actual participation appears to be the more proximal driver of satisfaction.

Overall, the structural model effectively explains the causal relationships among agritourism experience, perceived value, and visitor satisfaction. The model demonstrates strong statistical support and empirical consistency, validating the theoretical framework proposed in this study.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

This study advances the understanding of agritourism experience formation by integrating experiential marketing theory with perceived value and satisfaction in a structural equation model. The results provide clear empirical evidence that experiential elements significantly shape visitors’ value assessments and overall evaluations of agritourism. Two key psychological pathways emerge: experiential encounters generate immediate affective responses, while also informing subsequent cognitive value appraisals. This dual pathway reinforces the need for a more nuanced conceptualization of experiential processes in rural tourism settings, which differ substantively from the commercialized and highly designed experiences typically examined in mainstream tourism research.

A central theoretical contribution of this study is the articulation of how agritourism experiences differ from experiences occurring in constructed leisure environments. In contrast to theme parks or entertainment complexes—where narratives, spatial control, and standardized flows determine experience outcomes—agritourism is embedded within real agricultural labor, environmental variability, and the rhythms of rural life. Such conditions generate experiences that cannot be fully standardized or industrialized. The findings indicate that perceived value in agritourism is not derived from engineered stimuli, but instead from authenticity, place-based engagement, and meaningful human–land interactions. This establishes agritourism as a distinctive empirical site for expanding theories of the experience economy, particularly regarding how authenticity and relationality shape experiential quality.

From the perspective of Memorable Tourism Experiences (MTE) theory, this study further demonstrates that the components of experiential marketing align closely with MTE’s core dimensions—emotion, meaning, learning, novelty, and social connection. The structural model validates the psychological mechanism proposed in MTE frameworks: experiential quality influences satisfaction primarily through value appraisal. This evidence strengthens the theoretical bridge between MTE and rural tourism research by demonstrating how MTE processes unfold within farm-based activities, local cultural encounters, and community interactions. The findings therefore extend MTE theory into an empirical context where memory formation is likely driven by embodied participation and authentic human contact.

The study also clarifies the experiential dynamics for urban visitors, who constitute the primary customer segment for agritourism in East Asia. The results suggest that the experiential potency of agritourism is heightened because rural environments represent a pronounced contrast to urban life. The unfamiliarity, authenticity, and temporal differentiation of rural settings elicit stronger emotional and cognitive reactions, reinforcing the experiential marketing model in ways not observed in more familiar or routine leisure contexts. This highlights agritourism’s value proposition within the broader experience economy: it offers not merely consumption, but an alternative lifeworld.

From a governance and management perspective, the study identifies Destination Management Organizations (DMOs) as a critical institutional actor in Taiwan’s agritourism system. Local tourism associations, slow-city networks, and regional tourism alliances coordinate closely with rural communities and leisure farms to shape experience design, brand identity, thematic routes, and festivals. The Ministry of Agriculture’s Leisure Agriculture Area framework functions similarly to a DMO, incorporating brand certification, quality monitoring, and integrated experience curation. These findings underscore the need for agritourism governance frameworks to evaluate success not only through economic metrics, but through experiential quality and value creation—dimensions central to long-term rural sustainability.

This study contributes to the literature in three substantive ways. First, it offers a theoretically grounded and empirically validated model that integrates experiential marketing with perceived value and satisfaction, addressing a long-standing gap in agritourism research. Second, it demonstrates that agritourism experiences derive their value from authenticity, sense of place, and social interaction—establishing agritourism as a theoretically meaningful context for advancing experience economy and MTE research. Third, it highlights the governance role of DMOs and provides actionable insights for rural experience design, suggesting that future development should foreground local narratives, seasonal rhythms, farm-based participation, and community involvement.

The study is not without limitations. Data were collected from four regions in Taiwan, and cross-cultural generalizability remains to be assessed. The model, while theoretically robust, does not incorporate other constructs relevant to rural tourism such as environmental ethics, land attachment, or cultural sustainability. Additionally, the analysis reflects only the visitor perspective; incorporating the views of farmers and DMOs would allow for a more comprehensive multi-stakeholder understanding. Future research could develop a triadic “visitor–farmer–DMO” framework to deepen theoretical insights into agritourism as a site of rural governance and experiential value creation.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, H-Y.F. and H-c.C.; methodology, H-Y.F and C-L.T.; software, C-L.T.; validation, H-Y.F., H-c.C. and C-L.T..; formal analysis, C-L.T..; data curation, H-Y.F and T-Y.C..; writing—original draft preparation, H-Y.F. and H-c.C.; writing—review and editing, H-cC.; visualization, H-Y.F.; project administration, T-Y.C.; funding acquisition, H-Y.F.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Rural Development and Soil and Water Conservation Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Taiwan, grant number 113-Nongzai-1.1.1-1.1-Bao-001(12).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, S.-C.; Veenstra, A. Resilience through diversification: Agritourism on Canadian family farms. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue canadienne d’agroeconomie 2020, 68(4), 501–517. [Google Scholar]

- Martinus, K.; Boruff, B.; Nunez Picado, A. Authenticity, interaction, learning and location as curators of experiential agritourism. Journal of Rural Studies 2024, 108, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy; Harvard Business School Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C. The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. International journal of hospitality management 2014, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H. A structural model of liminal experience in tourism. Tourism Management 2019, 71, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihombing, S. O.; Antonio, F.; Sijabat, R.; Bernarto, I. The Role of Tourist Experience in Shaping Memorable Tourism Experiences and Behavioral Intentions. International Journal of Sustainable Development & Planning 2024, 19(4). [Google Scholar]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. What drives tourists’ moral decision-making? Moral obligation, value, and loyalty in nature-based tourism. Tourism Management 2020, 79, 104098. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. H. S.; Huang, Y. C. A study of relationships among farm tourism experience, perceived value, and loyalty. International Journal of Tourism Research 2020, 22(4), 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner, L.; Kline, C.; Oliver, J.; Kariko, D. Exploring emotional response to images used in agritourism destination marketing. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 9, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volgger, M.; Erschbamer, G.; Pechlaner, H. Destination design: A heuristic for inter-organizational collaboration in tourism destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2021, 19, 100557. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Food tourism and place identity in the era of the ‘slow’ traveler. Journal of Place Management and Development 2023, 16(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Agritourism from the perspective of providers and visitors: A typology-based study. Tourism Management 2014, 40, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, L. C.; Stewart, M.; Schilling, B.; Smith, B.; Walk, M. Agritourism: Toward a conceptual framework for industry analysis. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 2018, 8(1), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, C.; Barbieri, C. The perceived benefits of agritourism: The provider’s perspective. Tourism management 2012, 33(1), 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M. J.; Marques, C. P.; Loureiro, S. M. C. The dimensions of rural tourism experience: Impacts on arousal, memory, and satisfaction. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2018, 35(5), 639–669. [Google Scholar]

- Ohe, Y. Educational tourism in agriculture and identity of farm successors: Evidence from Japan. Tourism Economics 2018, 24(2), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-H.; Liu, C.-F.; Lin, Y.-T.; Yai, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-H. New agriculture business model in Taiwan. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review 2020, 23(5), 773–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T. H. Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-S.; Sun, C.-H. Promoting local agritourism: A case study of Indigenous agritourism businesses in Hualien County, Taiwan. FFTC Journal of Agricultural Policy 2024, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M.; Seyfi, S.; Rather, R. A.; Hall, C. M. Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tourism Review 2022, 77(2), 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, P.; Alves, H. Customer value co-creation in the hospitality and tourism industry: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 2023, 35(1), 250–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, Z. R.; Kusumawati, A. The Relationship of Destination Attributes, Memorable Tourism Experiences, Satisfaction, and Revisit Intention. KnE Social Sciences 2024, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A. R. D. Considering the role of agritourism co-creation in a culinary tourism context. Tourism Management Perspectives 2017, 23, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means–end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing 1988, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F. The roles of quality, value, and satisfaction in predicting cruise passengers’ behavioral intentions. Journal of Travel Research 2004, 42, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, M. W.; Wang, Y.; Kwek, A. Conceptualising co-created transformative tourism experiences: A systematic narrative review. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2021, 47, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhartanto, D.; Dean, D.; Chen, T.; Kusdibyo, B.; L. Tourist experience with agritourism attractions: what leads to loyalty? Tourism Recreation Research 2020, 45(3), 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. H.; Park, D. B. Relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: Community-based ecotourism in Korea. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 2017, 34(2), 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Soutar, G. N. Value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions in an adventure tourism context. Annals of tourism research 2009, 36(3), 413–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Adly, M. I. Modelling the relationship between hotel perceived value, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2019, 50, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Mohapatra, S.; Roy, S. Memorable tourism experiences (MTE): Integrating antecedents, consequences and moderating factor. Tourism and hospitality management 2022, 28(1), 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volo, S. The experience of emotion: Directions for tourism design. Annals of Tourism Research 2021, 86, 103097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 1988, 16(1), 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ritchie, J.R.B.; McCormick, B. Development of a scale to measure memorable tourism experiences. Journal of Travel Research 2012, 51, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr.; Anderson, R. E.; Tatham, R. L.; Black, W. C. Multivariate data analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R. L. Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer; McGraw-Hill, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of cross-cultural psychology; Triandis, H. C., Berry, J. W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon, 1980; Vol. 2, pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).