Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

“Whoever discovers a safe and harmless surgical method could rightly be considered a benefactor of humanity. Thousands of people would be spared great inconveniences; thousands would avoid the dangers and horrific suffering of strangulation.” (Reverdin, 1881)

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Lister and the Antiseptic Method

3.2. From Subcutaneous Surgery to Dissection: When Is the AOEM Incised?

3.3. Participation of the Founding Fathers

4. Conclusion

*“No one can write anything about the subject of hernias without referring to Wood’s work, and although his original operation is no longer practiced, modifications to it are simply the natural result of the introduction of antiseptics into surgery.” (The Lancet, 1892)

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, LF. Hernia. Mosby Co. St. Louis, 1924.

- Sachs, M.; Damm, M.; Encke, A. Historical evolution of inguinal hernia repair. World J. Surg. 1997, 21, 218–223. [CrossRef]

- Malangoni, M.A.; Rosen, M.J. Hernias. En: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston. Tratado de cirugía. 20a ed. Elsevier. Madrid, 2018.

- Bittner, R.R.; Felix, E.L. History of inguinal hernia repair, laparoendoscopic techniques, implementation in surgical praxis, and future perspectives: Considerations of two pioneers. Int J of Abd Wall and Hernia Surg. 2021, 4(4), 133-155. DOI: 10.4103/ijawhs.ijawhs_85_21. [CrossRef]

- Segond, P. Cure radicale des hernies. These présentee au concours de l´agrégation (section de chirurgie et d´accouchements). Masson. Paris, 1883.

- Thierry, A. Des diverses méthodes operatoires pour la cure radicale des hernies. Thése, Faculté de Medecine de Paris. Moquet et Compagnie, 1841.

- Roustan, A. De la hernie interstitielle.Thése pour le Doctorat en Médecine. Faculté de Medecine de Paris. Fonderie de Rignoux, Paris, 1843.

- Boinet, A.A. De la cure radicale des hernies. Thése, Concours d'agrégation. Faculté de Medecine de Paris. Maulde et Renou. Paris, 1839.

- Moreno-Egea, A.; Moreno-Latorre, C.; Moreno-Latorre, A. El Último Cirujano Anatomista: Conrad Martin Johann Langenbeck (1776-1851). Inter J of Morphol. 2024, 42, 1328-1337. 10.4067/S0717-95022024000501328. [CrossRef]

- Ashhurst, J. The International Encyclopaedia of Surgery: A Systematic Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Surgery. William Wood & Co. New York, 1883-85.

- Le Dentu, J.F.K.; Delbet, P. Traité de chirurgie clinique et opératoire. J. B. Bailliere et Fils. Paris, 1898.

- Lister, B.J. On the antiseptic principle in the practice of surgery. The Lancet 1867, 90(2299), 353-356.

- Marcy, H.O. Carbolized catgut sutures (buried in the tissues) for the cure of hernia. Boston Med. Surg. J. 1871, 85, 315-316. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM187111160852002. [CrossRef]

- Biographical sketch of Dr. Henry O. Marcy. Physicians and Surgeons of America, 1896.

- Steele, C. On Operations For The Radical Cure Of Hernia. Brit Med J. 1874, 2(723), 584-584. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25239741.

- Stoppa, R. Survol historique de la chirurgie des hernies De la castration à la haute technologie. Histoire des Sciences Mëdicales 2001, 35(1), 57-70.

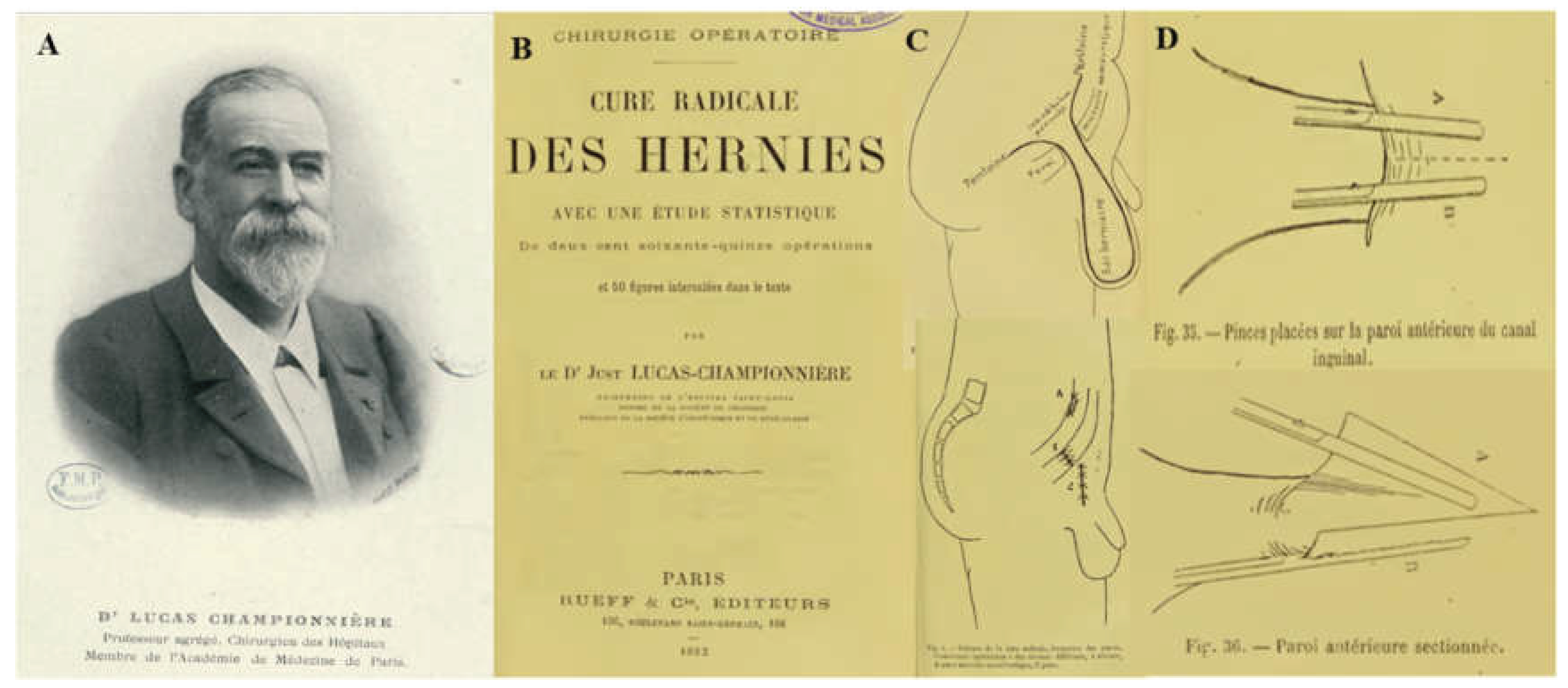

- Lucas-Championnière, J. Sur la cure radicale des hernies. Bull. et Mem. Soc. Chir (Paris). 1887, 13, 737-742.

- Lucas-Championnière, J. Chirurgie opératorie. Cure radicale des hernies; avec une etude statistique de deux cents soixante-quinze operations. Paris, Rueff et Cie, 1892.

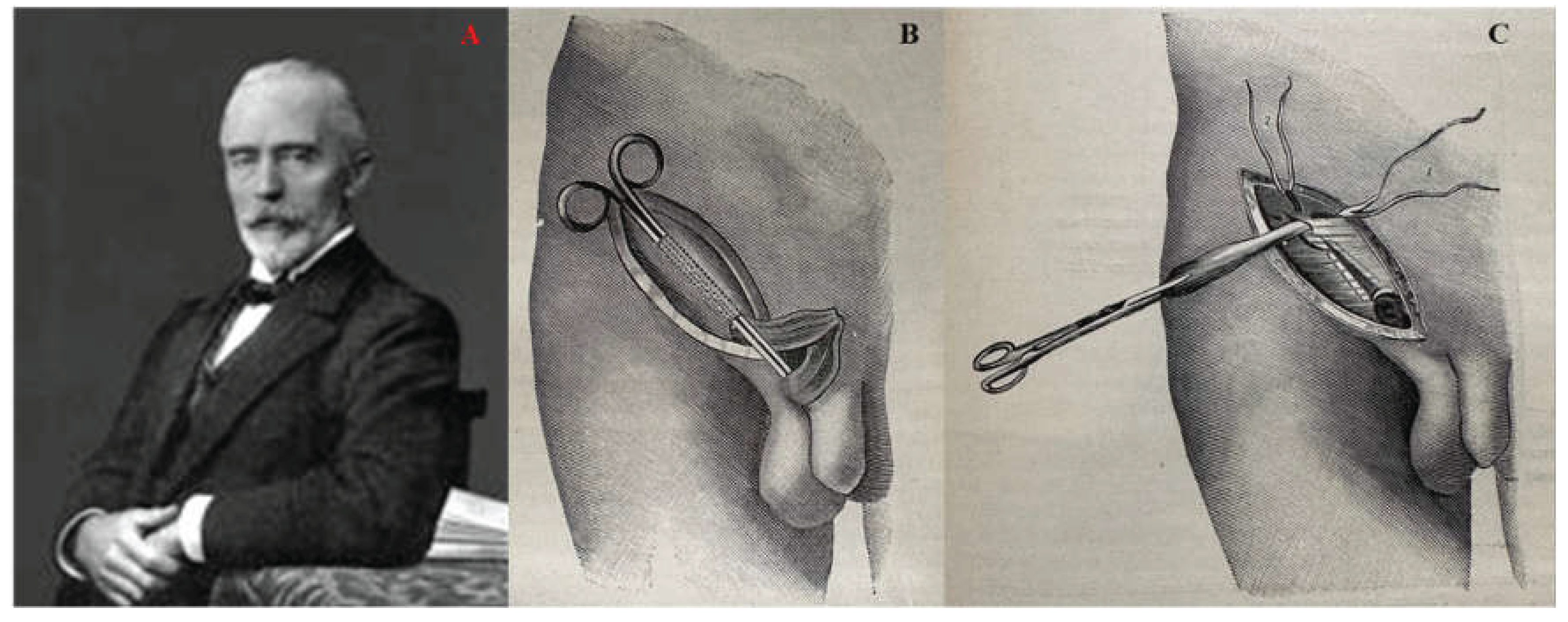

- Wood, J. On a new method of operation for the radical cure of hernia. Medico-Chirurg Transactions 1860, 43, 71. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. On Rupture Inguinal, crural, and umbilical: the anatomy, pathology, diagnosis, cause and prevention with new methods of effecting a radical and permanent cure embodying the Jacksonian prize essay of the Royal College of Surgeons. John W. Davies. London, 1863.

- Wood, J. Lectures on Hernia and its Radical Cure: Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England in June, 1885 - with A Clinical Lecture on Trusses and Their Application to Ruptures. Henry Renshaw. London, 1886.

- Death of professor John Wood. The Lancet 1892, 139(3566), 39. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)13946-8 . [CrossRef]

- Alderson, J.; Toynbee, J.; Durham, A.E.; Smith, W.T. Reports Of Societies. Brit Med J. 1866, 1(286), 674-677. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25205725.

- Reverdin, J-L. Des opérations modernes de cure radicale des hernies. Revue Médicale de la suisse romande. Libraire-Editeur H. George. Genéve, 1881.

- Riesel, O. Versuche zur Radicalheilung freier Hernien. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1877, 3(38), 449-452. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1194032. [CrossRef]

- Riesel, O. Versuche zur Radicalheilung freier Hernien (Schluss aus No. 38.). Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1877, 3(39), 467-469. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1194045. [CrossRef]

- Marcy, H.O. The cure of hernia by the antiseptic use of animal ligature. Trans Int Med Congr. 1881, 2, 446.

- Marcy, H.O. A treatise on hernia. The radical cure by the use of the buried antiseptic animal suture. GS Davis. Detroit, 1889.

- Lucas-Championnière, J. Cure radicale des hernies. Avec une étude statistique de deux cent soixante-quinze opérations, et 50 figures intercalées dans le texte. Rueff & Cie. Paris, 1892.

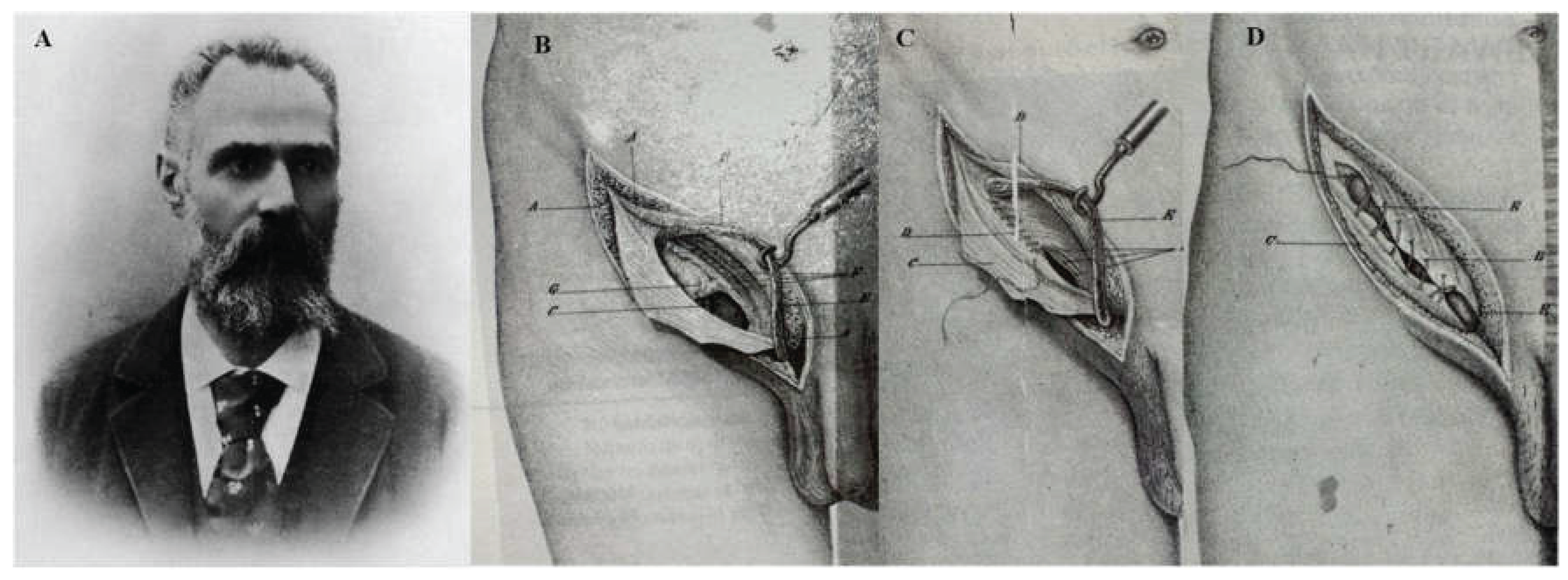

- Bassini, E. Sopra 100 casi di cura radicale dell’ernia inguinale operata col metodo dell-autore. Arch ed Atti Sot ltal Chir. 1888, 5, 315-9.

- Bassini, E. Nuovo metodo per la cura radicale dell’ernia inguinale. Padua: Prosperini, 1889.

- Bassini, E. Ueber de behandlung des leistenbruches. Arch Klin Chir. 1890, 40, 429-476.

- Kocher, E.Th. Zur radicalcur der hernien. Cor. Bl. für Schweiz. Aerzte (Basel), 1892, 18, 12.

- Czerny, V. Studien zur radikalbe-handlung der hernien. Wein Med Wschr. 1877, 27, 497-500.

- Macewen, W.I. On the Radical Cure of Oblique Inguinal Hernia by Internal Abdominal Pad and the Restoration of the Valved Form of the Inguinal Canal. Ann Surg. 1886, 4(2), 89-119. doi: 10.1097/00000658-188612000-00010. [CrossRef]

| Year | Technique | Author (country) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1808 | Open surgery: 1) Sac dissection and ligation 2) Autoplastic flap obturation |

Langenbeck (Hanover, Germany)) | [9] |

| 1835 | Closed or subcutaneous surgery: Intussusception operation | Gerdy (Paris, France) | [6,7] |

| 1846 | Anesthesia | Morton (Boston, EEUU) | [9] |

| 1858 | Open surgery: closure of the inguinal canal (invasive suture) | Wood (London, England) | [21] |

| 1865 | Antisepsis | Lister (Glasgow, England) | [12] |

| 1866 | Dissection surgery: open the AEOM | Durham (London, England) | [23] |

| 1871 | Open surgery: closure of the abdominal ring | Marcy (Boston, EEUU) | [13] |

| 1874 | Open surgery: closure of the superficial ring | Steele (Bristol, England) | [15] |

| 1877 | Dissection surgery: open the AEOM (Riesel method) | Riesel (Halle, Germany) | [26] |

| 1877 | Open surgery: tamponade of the IIR with the folded sac, suture of the EIR pillars, reinforcement of the AEOM (without opening it) | Czerny (Berlín, Germany)) | [34] |

| 1881 | Open surgery: incisions in the AEOM, in two alternating and overlapping series | Reverdin (Geneva, Switzerland) | [24] |

| 1885 | Open surgery: transplant the remodeled sac laterally under the AEOM | Kocher (Bern, Switzerland) | [33] |

| 1885 | Dissection surgery: opening of the inguinal canal; resection of peritoneal diverticulum (Lucas-Ch. concept); overlap of the AEOM | Lucas-Ch. (Paris, France) | [17] |

| 1886 | Open surgery: valve closure of the canal with the sac as a plug | Macewen (Glasgow, England) | [35] |

| 1888 | Total dissection surgery: Posterior floor closure triple layer | Bassini (Padua, Italy)) | [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).