1. Introduction

Fungal symbionts play indispensable roles in terrestrial ecosystems and agriculture, forming mutualistic, parasitic, or commensal relationships with a vast range of host plants [

1]. Among these, the root-inhabiting fungus

Armillaria mellea (

A. mellea) is of particular ecological and economic importance as an obligate symbiont of the achlorophyllous orchid

Gastrodia elata (G. elata), providing essential nutrients for its growth throughout a three-year life cycle [

2,

3]. The vigor and stress resilience of

A. mellea directly determine the yield and quality of

G. elata, a highly valued medicinal herb in traditional Chinese medicine [

4,

5]. However, like many fungi,

A. mellea is highly sensitive to low-temperature stress, which frequently occurs during early spring and late autumn in its cultivation areas. This sensitivity constitutes a major bottleneck for the stable production of

G. elata [

6]. Therefore, enhancing the cold tolerance of this symbiotic fungus is an urgent agricultural objective.

Under abiotic stress, including chilling, cells experience an accelerated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [

7]. To mitigate such damage, organisms have evolved sophisticated antioxidant systems, in which superoxide dismutase (SOD) acts as the first line of defense by catalyzing the dismutation of superoxide anions (O

2•

−) into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen [

8,

9]. Based on their metal cofactors, SODs are classified into Cu/Zn-SODs, Fe-SODs, Mn-SODs, and Ni-SODs [

10,

11]. In plants, the critical role of SODs in conferring tolerance to drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures has been well documented through transgenic approaches [

12,

13,

14]. In contrast, the functional significance of SODs in fungal symbionts, particularly in the context of host-derived gene resources, remains largely unexplored. Investigating whether a plant-derived SOD can function within a fungal partner to enhance its stress resilience represents a novel frontier in symbiotic biology and applied mycology.

The

G. elata–

A. mellea system offers a unique model to address this question.

G. elata, lacking photosynthetic capacity, has likely evolved robust molecular mechanisms to cope with environmental stress, potentially including an efficient antioxidant repertoire [

15]. Recent transcriptomic studies of

G. elata have enabled the genome-wide identification of gene families involved in stress responses [

16]. Among these, the SOD gene family represents a key candidate for biotechnological exploitation to improve the stress tolerance of its fungal partner.

In this study, we identified 10 SOD genes from the G. elata transcriptome and focused on GeSOD7, a highly expressed mitochondrial Mn-SOD, for functional characterization. We hypothesized that heterologous expression of this plant-derived GeSOD7 in A. mellea would enhance its antioxidant capacity and improve its tolerance to low-temperature stress. To test this, we (1) characterized the biochemical properties of the recombinant GeSOD7 protein, (2) generated GeSOD7-overexpressing transgenic strains of A. mellea, and (3) evaluated their physiological, biochemical, and molecular responses under cold stress. Our findings demonstrate that GeSOD7 overexpression significantly enhances cold tolerance in A. mellea by modulating antioxidant metabolism and redox homeostasis, providing a novel genetic strategy for engineering stress-resilient fungal symbionts to support sustainable cultivation of medicinal plants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Fungal Materials

Tubers of G. elata f. glauca were collected from Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province, China. The A. mellea strain AM02, previously isolated and preserved in our laboratory, was used throughout this study. Fungal cultures were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 23 °C in the dark.

2.2. Identification of the SOD Gene Family in G. elata

Hidden Markov models (HMMs) corresponding to SOD family domains (Pfam: PF00080, PF00081, PF02777) were retrieved from the Pfam database (

http://pfam.xfam.org/). Candidate SOD genes were identified from the

G. elata transcriptome using TBtools v2.0 [

17]. Domain validation was performed using SMART (

http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD;

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd/). Redundant sequences and those lacking complete SOD domains were excluded.

2.3. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

Reference SOD protein sequences from

Arabidopsis thaliana and

Dendrobium candidum were downloaded from the NCBI protein database. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW in MEGA-X [

18]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

2.5. Expression Profiling and Gene Selection

Transcriptomic expression data (FPKM values) of GeSOD genes were obtained from three tissue types: immature tubers at 13 °C (NS), immature tubers symbiotic with A. mellea at 23 °C (TB), and mature tubers (SS). Expression values were log2-transformed, and a heatmap was generated using TBtools. GeSOD7 was selected for functional analysis based on its high expression and predicted mitochondrial localization.

2.6. Gene Cloning and Vector Construction

The coding sequence (CDS) of GeSOD7 was amplified from

G. elata cDNA using gene-specific primers (

Table S1). The purified PCR product was ligated into the pET-32a

(+) vector (Novagen) for prokaryotic expression. For fungal transformation, the GeSOD7 CDS was recombined into the Gateway

®-compatible binary vector pH7WG2.0 using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen), generating pH7WG2.0-35S-GeSOD7. The construct was introduced into

A. tumefaciens strain PMP90 via electroporation.

2.7. Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification

The recombinant plasmid pET-32a-GeSOD7 was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Protein expression was induced with 0.1–1.0 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 37 °C for 8 h. His-tagged GeSOD7 was purified under native conditions using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE.

2.8. Enzyme Activity Assay and Biochemical Characterization

SOD activity was measured using the ABTS method [

19]. The optimal temperature was determined by assaying activity between 30 °C and 90 °C. Thermostability was evaluated by pre-incubating the enzyme at 40–70 °C for 0–80 min before activity measurement. The optimal pH was determined in buffers ranging from pH 2.0 to 10.0. The effects of metal ions (Fe

2+, Ca

2+, Mg

2+, Zn

2+, K

+, Na

+, Mn

2+, Cu

2+) at 5 and 9 mM were also tested. All assays were performed in triplicate.

2.9. Genetic Transformation of A. mellea

A. tumefaciens PMP90 harboring pH7WG2.0-35S-GeSOD7 was co-cultured with wild-type

A. mellea mycelia on induction medium (IM) at 25 °C for 10 h. After co-culture, mycelia were washed with sterile water containing cefotaxime (500 µg/mL) and transferred to PDA medium supplemented with hygromycin B (50 µg/mL). Positive transformants were selected after 10–14 days and subcultured on selective media. Integration of

GeSOD7 and the

hph (hygromycin phosphotransferase) gene was confirmed by PCR using specific primers (

Table S1).

2.10. Cold Stress Treatment and Physiological Assays

Wild-type and transgenic strains were pre-cultured on PDA until rhizomorph formation. Rhizomorph fragments were inoculated into semi-solid medium and incubated at 13 °C for 45 days. Mycelia were harvested for physiological analysis. Glutathione content was measured using a commercial assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined by thiobarbituric acid colorimetry [

20], soluble sugar by anthrone colorimetry [

21], hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) by xylenol orange colorimetry [

22], and free proline by the acid ninhydrin method [

23]. All measurements were performed with three biological replicates.

2.11. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg RNA using HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme). RT-qPCR was performed on a QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green master mix (Takara). Gene-specific primers for target genes (Glutamate dehydrogenase, Catalase, Glutathione reductase, Glutathione peroxidase, Trehalose phosphorylase) and the reference gene (Elongation Factor 1-alph, EF-1α) are listed in

Table S2. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method [

24].

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

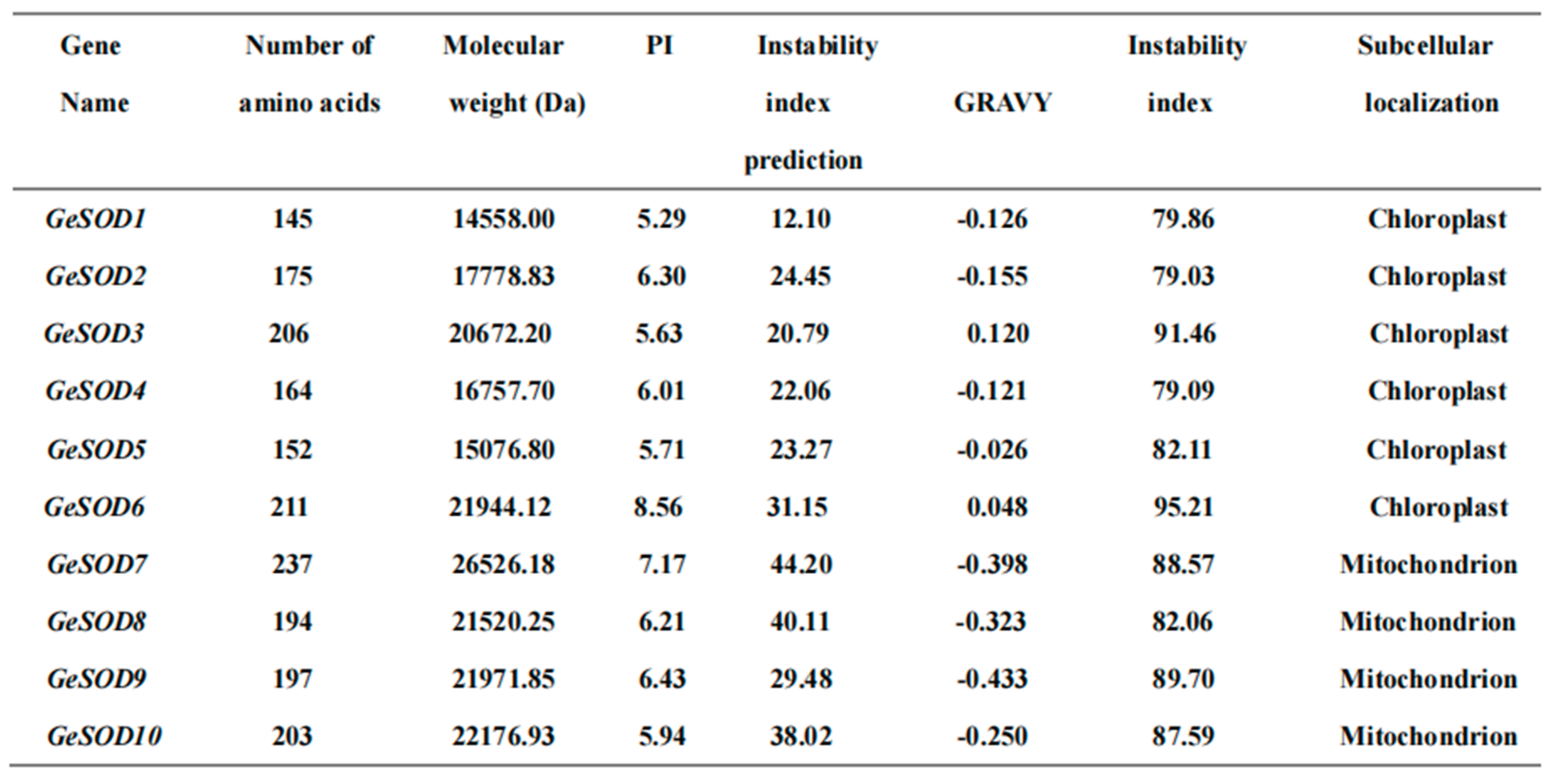

3.1. Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis of the SOD Gene Family in G. elata

A total of 18 putative SOD genes were initially retrieved from the

G. elata transcriptome using HMM searches. After removing redundant and incomplete sequences through domain validation, 10 non-redundant SOD genes were confirmed and designated

GeSOD1 to

GeSOD10 (

Table 1). Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the encoded proteins ranged from 145 to 237 amino acids in length, with molecular weights between 14.39 and 26.53 kDa and theoretical isoelectric points (pI) from 5.29 to 8.56. Subcellular localization predictions indicated that GeSOD1–GeSOD6 are likely chloroplast-targeted, whereas GeSOD7–GeSOD10 are predicted to localize to mitochondria.

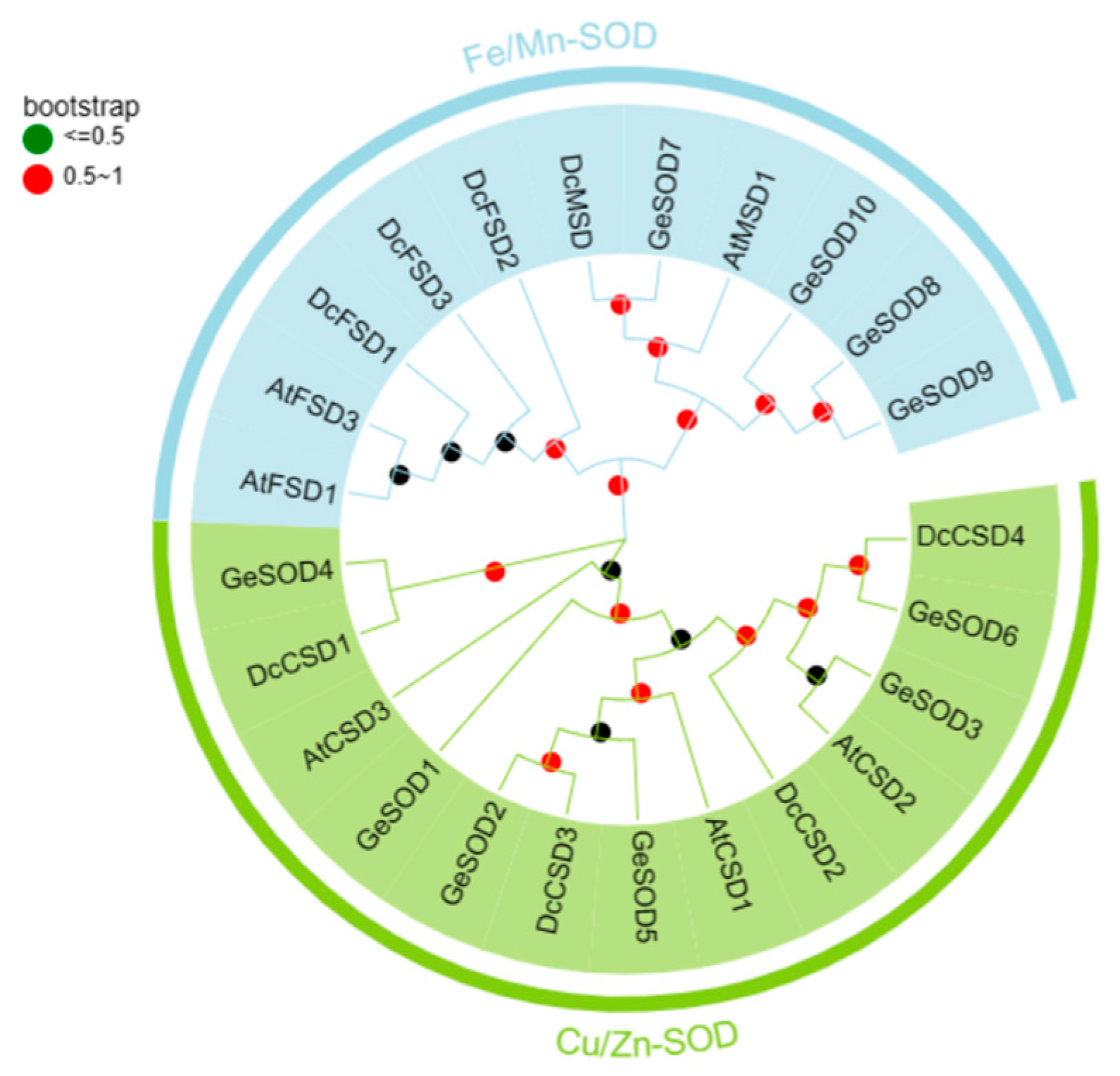

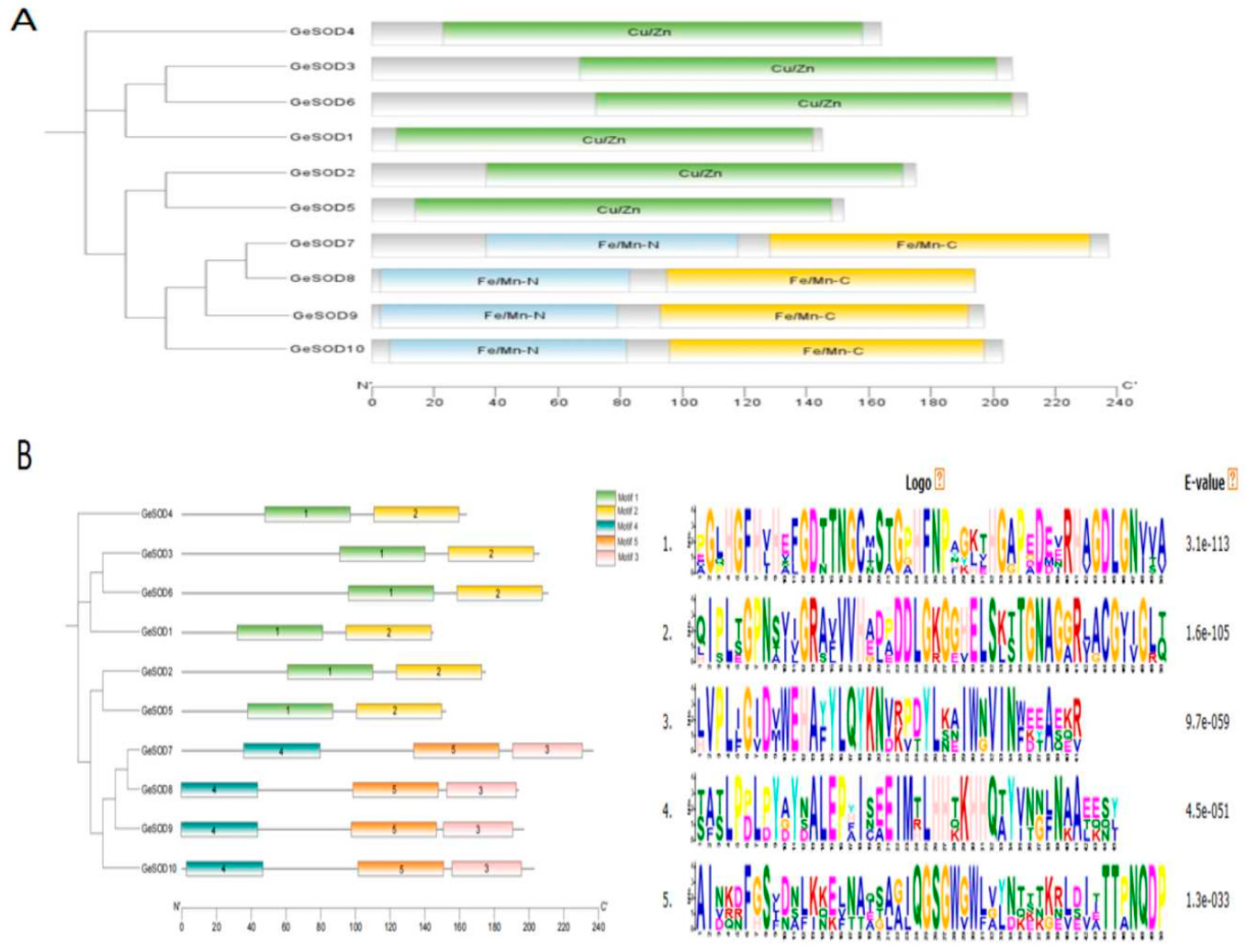

3.2. Phylogenetic and Conserved Motif Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis classified the 10 GeSOD proteins into two distinct clades (

Figure 1). GeSOD1–GeSOD6 clustered with known Cu/Zn-SODs, while GeSOD7–GeSOD10 formed a separate clade closely related to mitochondrial Mn-SODs from

A. thaliana and

Dendrobium candidum. Domain architecture analysis confirmed that GeSOD1–6 contain the Cu/Zn-SOD domain, whereas GeSOD7–10 harbor the Fe/Mn-SOD domain (

Figure 2A). MEME motif analysis further supported this classification, revealing distinct conserved sequence patterns between the two groups (

Figure 2B).

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates, comparing GeSOD proteins with AtSOD (Arabidopsis thaliana) and DcSOD (Dendrobium candidum).

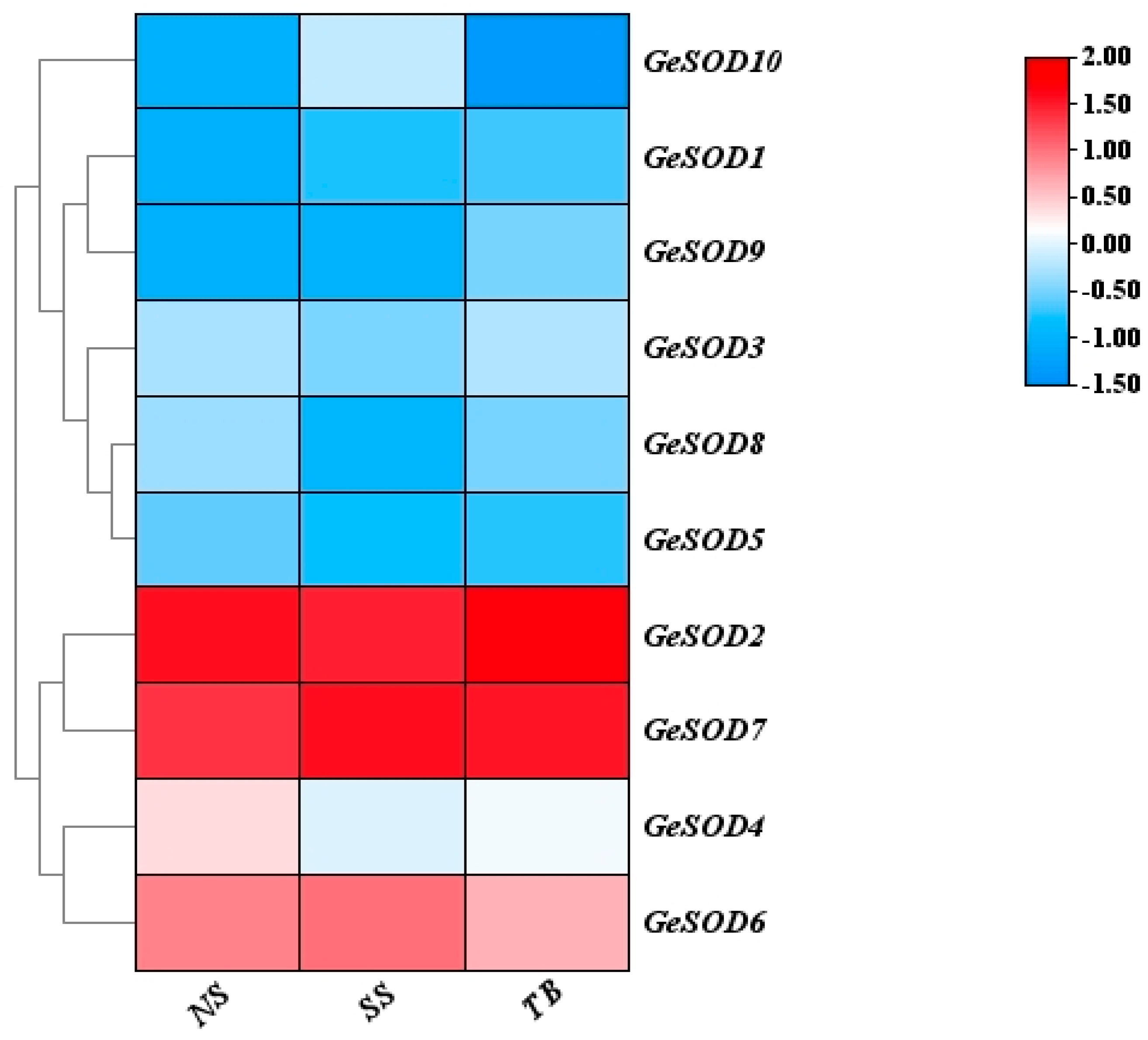

3.3. Expression Profiling and Selection of GeSOD7

Analysis of transcriptomic expression data across different tissues and temperatures showed that GeSOD2 and GeSOD7 were the most highly expressed genes within the family (

Figure 3). Both genes exhibited notably high expression in immature tubers at 13 °C, as well as in symbiotic and mature tuber tissues at 23 °C. Given the achlorophyllous nature of

G. elata tubers and the mitochondrial localization prediction, GeSOD7 was selected as the prime candidate for further functional investigation related to low-temperature stress.

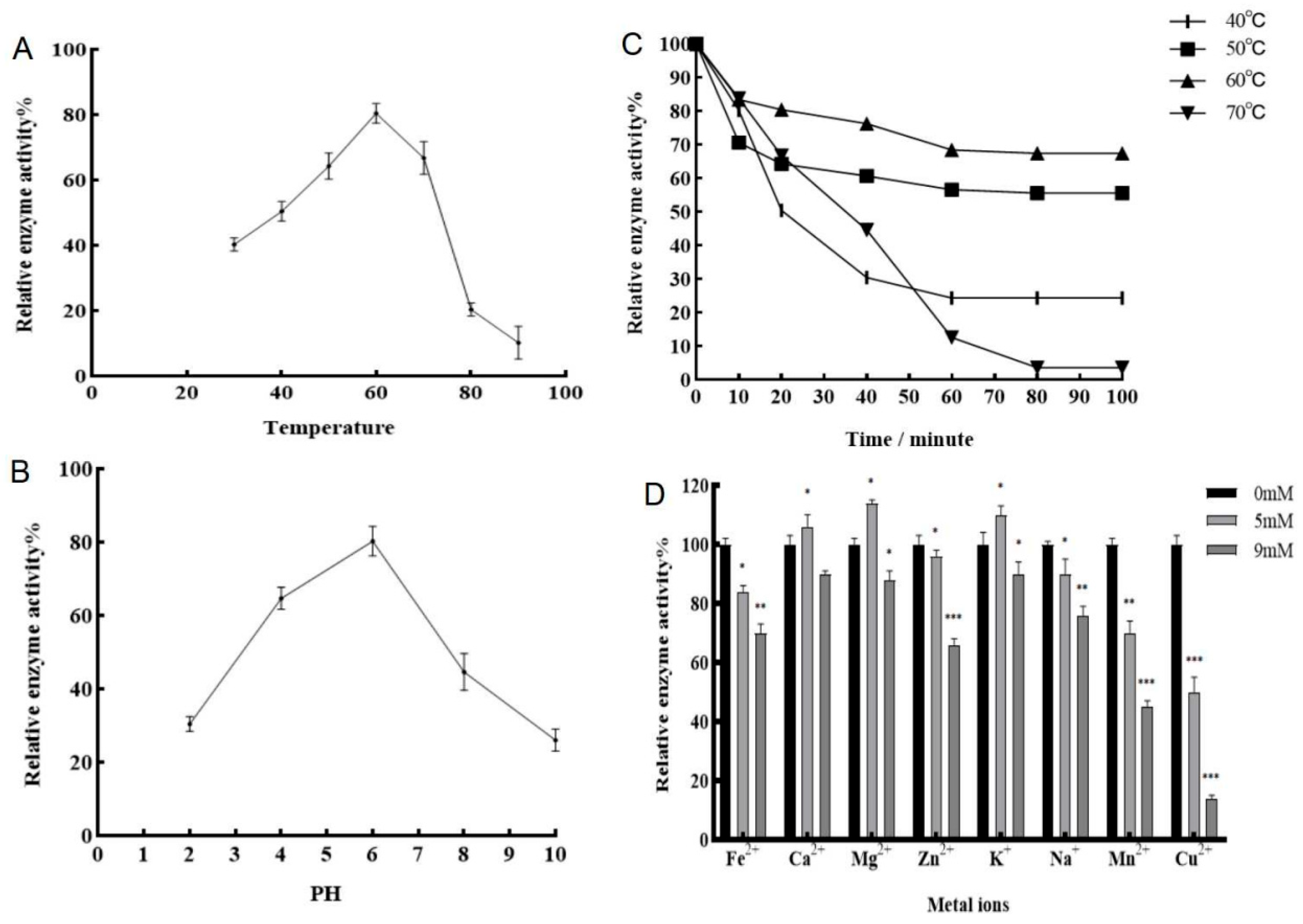

3.4. Heterologous Expression and Enzymatic Characterization of GeSOD7

The GeSOD7 coding sequence was successfully expressed in

E. coli BL21(DE3). SDS-PAGE confirmed the induction and purification of the recombinant His-tagged GeSOD7 protein with an apparent molecular weight of approximately 40 kDa (

Figure S1). Biochemical characterization revealed that the purified GeSOD7 exhibited maximum activity at 60 °C and pH 6.0 (

Figure 4A,C). The enzyme showed moderate thermostability at 60 °C but was rapidly inactivated at 70 °C (

Figure 4B). Metal ion assays indicated that enzyme activity was significantly inhibited by high concentrations (9 mM) of Mn

2+ and Cu

2+, while Ca

2+, Mg

2+, and K

+ had mild effects at lower concentrations (5 mM) (

Figure 4D).

3.5. Overexpression of GeSOD7 Enhances Cold Tolerance in A. mellea

The binary vector pH7WG2.0-35S-GeSOD7 was successfully introduced into wild-type

A. mellea via

A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation. Positive transformants were selected on hygromycin-containing media and validated by PCR amplification of both the GeSOD7 insert and the

hph marker gene (

Figure 5A,B). Under prolonged low-temperature stress (13 °C for 45 days), the GeSOD7-overexpressing (OE) strains displayed significantly more robust rhizomorph development and a higher fresh weight compared to the wild-type (WT) control (

Figure 5C,D).

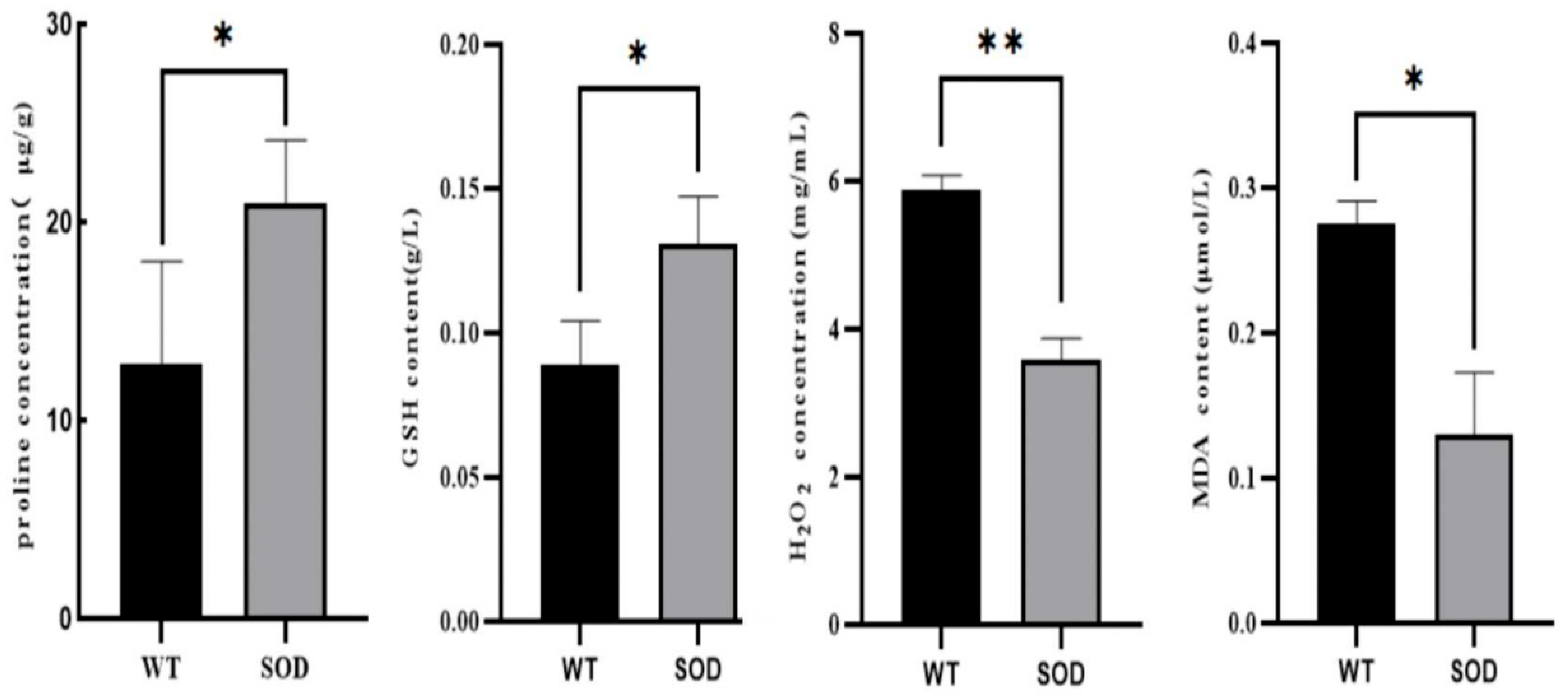

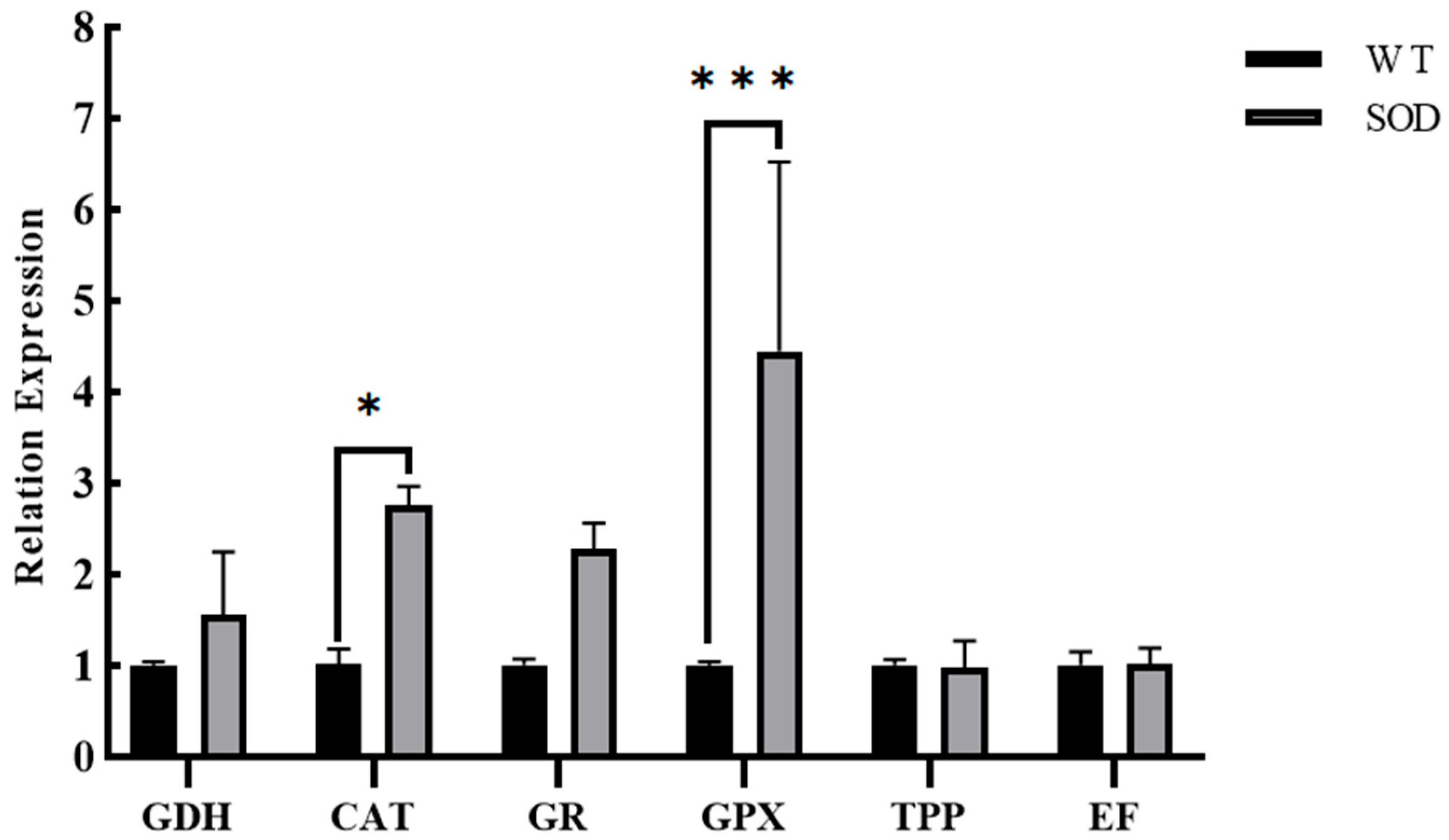

3.6. GeSOD7 Overexpression Modulates Antioxidant Metabolism and Alleviates Oxidative Damage

Physiological analysis revealed that the OE strains accumulated significantly higher levels of glutathione (GSH) and proline compared to the WT under cold stress (

Figure 6A,B). Concurrently, the contents of hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) and malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, were markedly reduced in the transgenic strains (

Figure 6C,D). Consistent with these physiological changes, RT-qPCR analysis showed that the expression of key antioxidant genes—including Glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH), Catalase (CAT), Glutathione reductase (GR), and Glutathione peroxidase (GPX)—was significantly upregulated in the OE strains, whereas Trehalose phosphorylase (TPP) expression remained unchanged (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

Enhancing the stress resilience of symbiotic fungi is a critical step toward securing the productivity of economically important plant–fungus systems. This study demonstrates, for the first time, that the heterologous expression of a plant-derived manganese superoxide dismutase gene, GeSOD7, can significantly improve the cold tolerance of the symbiotic fungus A. mellea. Our findings reveal that this improvement is mechanistically underpinned by a reinforced antioxidant defense system and improved redox homeostasis, offering a novel genetic strategy for engineering stress-tolerant fungal symbionts.

4.1. GeSOD7 as a Functional Mn-SOD with Distinct Biochemical Properties

The 10 GeSOD proteins identified in this study were phylogenetically classified into Cu/Zn-SOD and Fe/Mn-SOD subfamilies, a categorization consistent with those reported in other plant species [

10,

25]. GeSOD7 clustered specifically with mitochondrial Mn-SODs, and its predicted subcellular localization to mitochondria aligns with its presumed role in scavenging superoxide anions (O

2•

-) generated in the electron transport chain—a major site of ROS production under stress [

26]. The recombinant GeSOD7 protein exhibited classic enzymatic characteristics of Mn-SODs, with an optimal activity at 60 °Cand pH 6.0. The pronounced inhibition of its activity by high concentrations of Mn

2+ and Cu

2+ is noteworthy. While Mn

2+ serves as an essential cofactor, excess ions can disrupt enzyme conformation or induce non-productive binding, a phenomenon observed in other metalloenzymes [

27]. This property highlights the importance of intracellular metal ion homeostasis for optimal SOD function in vivo.

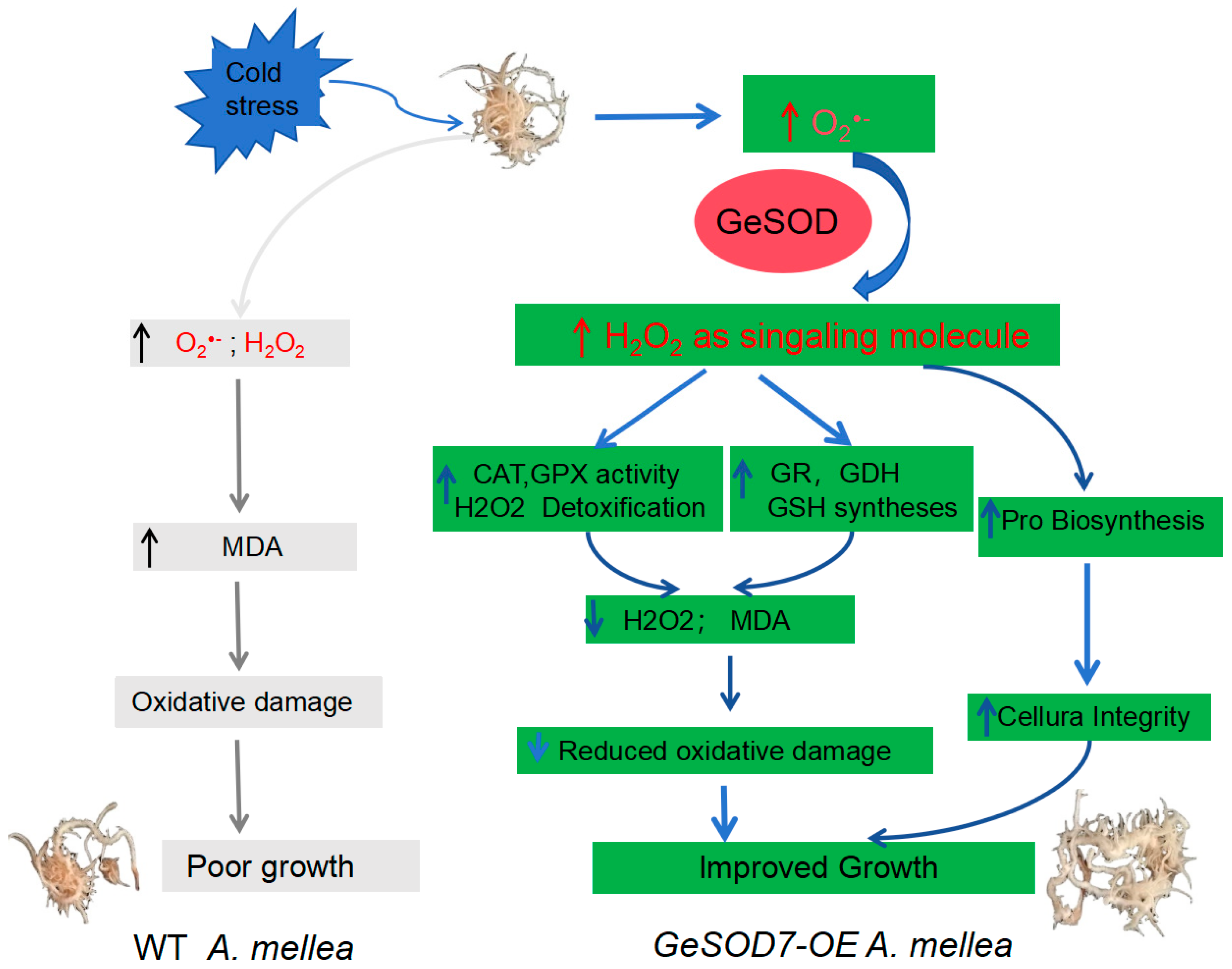

4.2. GeSOD7 Overexpression Confers a Growth Advantage Under Cold Stress by Activating a Coordinated Antioxidant Response

The core finding of this work is that GeSOD7 overexpression conferred a clear growth advantage to

A. mellea under prolonged low-temperature (13 °C) stress (

Figure 5). We propose a mechanistic model wherein enhanced SOD activity serves as the initial trigger for a broader defensive reprogramming (

Figure 8). The primary increase in SOD-mediated H

2O

2 production likely functions not only as a detoxification step but also as a signaling molecule, orchestrating the upregulation of downstream antioxidant components [

13,

28]. This is supported by the concurrent increase in the activities and gene expression of H

2O

2-scavenging enzymes (CAT and GPX) and the key glutathione-cycle enzyme GR in our transgenic strains (

Figure 7). The resultant significant reduction in both H

2O

2 and MDA levels unequivocally indicates mitigated oxidative damage to cellular membranes and other components [

29].

4.3. Synergistic Enhancement of Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Pools

Beyond enzymatic defenses, the transgenic strains exhibited a marked accumulation of the compatible solutes proline and glutathione (GSH) (

Figure 6). Proline is a multifunctional molecule known to act as an osmoprotectant, a ROS scavenger, and a stabilizer of cellular structures under abiotic stress [

30]. Glutathione, a major cellular redox buffer and antioxidant, serves as a crucial substrate for GPX and directly neutralizes reactive species [

31]. The upregulation of Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH), which bridges nitrogen metabolism with the synthesis of these compounds, suggests that GeSOD7 overexpression may rewire central metabolic pathways to support the biosynthesis of protective metabolites. This synergistic enhancement of both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant systems creates a robust defense network, enabling the fungus to maintain cellular integrity under cold stress.

4.4. Implications for Fungal Biotechnology and Sustainable Agriculture

While SOD overexpression has been shown to enhance abiotic stress tolerance in various transgenic plants [

17,

32], its application in improving the resilience of fungal symbionts remains underexplored. Our study effectively bridges this gap. The

G. elata–

A. mellea symbiosis is not only a fascinating model for basic research on cross-kingdom molecular interactions but also a system of high agricultural value [

3,

5]. The cold sensitivity of

A. mellea is a primary limiting factor for

G. elata cultivation in temperate regions. The strategy demonstrated here—using a host plant’s own genetic resource to fortify its fungal partner—presents a targeted and potentially sustainable approach to alleviate this bottleneck. Future work should focus on evaluating the performance of these engineered fungal strains in actual symbiotic cultivation settings and assessing their long-term genetic stability and environmental safety.

As summarized in the proposed model (

Figure 8), under cold stress, the heterologous expression of GeSOD7 in

A. mellea initiated a cascade of antioxidant responses. The primary increase in SOD activity not only directly scavenged O

2•

- but also generated a modulated level of H

2O

2, which likely acted as a signaling molecule to upregulate downstream defenses. This coordinated response ultimately resulted in reduced oxidative damage and improved growth, in stark contrast to the overwhelmed antioxidant system and poor growth observed in the wild-type strain under the same conditions.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides comprehensive evidence that the G. elata Mn-SOD gene GeSOD7 functions as a key regulator of antioxidant defense. Its heterologous expression in the symbiotic fungus A. mellea significantly enhanced cold stress tolerance through a multi-faceted mechanism involving the coordinated upregulation of enzymatic antioxidants and the accumulation of protective osmolytes. These findings advance our understanding of antioxidant network regulation in symbiotic fungi and establish a proof-of-concept for using plant-derived genes to engineer stress-resilient fungal partners, with direct implications for improving the sustainable production of valuable medicinal plants like G. elata.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant GeSOD7 expression and purification. Table S1: Primers used for cloning and PCR confirmation. Table S2: Primers used for RT-qPCR analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and K.L.; methodology, P.X., Z.Z., C.Z. and H.N.; validation, Y.L. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, P.X.; investigation, P.X. and Z.Z.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, P.X.; writing—review and editing, K.L. and X.Z.; visualization, P.X.; supervision, X.Z. and K.L.; project administration, K.L.; funding acquisition, K.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 31960071.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Faculty of Life Science and Technology, Kunming University of Science and Technology, for providing laboratory facilities and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.-Z.; Ma, L.; He, H.-Y.; Wang, Y.-C.; Cao, A.-J. Study of factors for cultivating the orchid species Gastrodia elata, a traditional Chinese medicine. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2014, 36, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-F.; Huang, X.-M.; Wang, R.; Wu, W.-C.; Qi, C. The life history of Gastrodia elata. J. Zhaotong Teach. Coll. 2009, 31, 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Chen, G. Effects of different Armillaria mellea on biological yield and gastrodin content of Gastrodia elata. Shandong Sci. 2003, 16, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, D.; Hu, Z. Plant 4-coumaric acid: coenzyme A ligase. Plant Physiol. Commun. 2006, 42, 529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z.; He, L.; Li, F. Understanding cold stress response mechanisms in plants: an overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1443317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridovich, I. Superoxide anion radical (O2•−), superoxide dismutases, and related matters. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 18515–18517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, G.R. Superoxide dismutase in redox biology: the roles of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, I.A.; Cabelli, D.E. Superoxide dismutases—a review of the metal-associated mechanistic variations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C.L.; Neupane, K.; Shearer, J.; Palenik, B. Diversity, function and evolution of genes coding for putative Ni-containing superoxide dismutases. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.S.; Heinen, J.L.; Holaday, A.S.; Burke, J.J.; Allen, R.D. Increased resistance to oxidative stress in transgenic plants that overexpress chloroplastic Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.-J.; Zhang, B.; Shi, W.-W.; Li, H.-Y. Hydrogen peroxide in plants: a versatile molecule of the reactive oxygen species network. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michonneau, P.; Fleurat-Lessard, P.; Roblin, G.; Bere, E. CuZn-superoxide dismutase is differentially modified in localization and expression by three abiotic stresses in miniature rose bushes. Micron 2023, 174, 103524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, G. The chemical composition, pharmacological effects, clinical applications and market analysis of Gastrodia elata. Pharm. Chem. J. 2017, 51, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Li, D.Q.; Guo, J.H.; Wang, Q.Y.; Zhang, K.J.; Wang, X.B.; Shao, L.M.; Luo, C.; Xia, Y.P.; Zhang, J.P. Identification and Analysis of the Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Gene Family and Potential Roles in High-Temperature Stress Response of Herbaceous Peony (Pall.). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, W.; Wang, W. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.-G.; Xiao, S.-Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.-F.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Li, K.-Z.; Yu, Y.-X.; Chen, L.-M. Changes in the activity and transcription of antioxidant enzymes in response to Al stress in black soybeans. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 31, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J. Experimental Guidance of Plant Physiology; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Huang, J. Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiological and Biochemical Experiments; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C.; Gebicki, J.M. Measurement of protein and lipid hydroperoxides in biological systems by the ferric-xylenol orange method. Anal. Biochem. 2003, 315, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dov, P.; Ren, Y.-Y.; Jiang, H.; Ma, L.; Li, Y.-C.; Bi, Y. Identification of SOD gene family in potato and its response in injured tuber. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2021, 29, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Buettner, G.R.; Ng, C.F.; Wang, M.; Rodgers, V.G.J.; Schafer, F.Q. A new paradigm: Manganese superoxide dismutase influences the production of H2O2 in cells and thereby their biological state. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1338–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Luo, G.-G.; Pan, C.-M.; Zhang, S.-W. Cloning and sequence analysis of full-length cDNA of Mn/Fe-SOD gene from Evodia rutaecarpa. Chin. Herb. Med. 2012, 43, 1814–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, G.; Suzuki, N.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Mittler, R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signalling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.W.; Stals, E.; Panis, B.; Keulemans, J.; Swennen, R.L. High-throughput determination of malondialdehyde in plant tissues. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 347, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Hima Kumari, P.; Sunita, M.S.L.; Sreenivasulu, N. Role of proline in cell wall synthesis and plant development and its implications in plant ontogeny. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Xia, F.; Yan, H. Research progress of plant antioxidant glutathione. Pratacultural Sci. 2013, 21, 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Zhu, Z.; Li, W.-C. Over-expression of exotic superoxide dismutase gene MnSOD and increase in stress resistance in maize. J. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 2006, 32, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).