Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

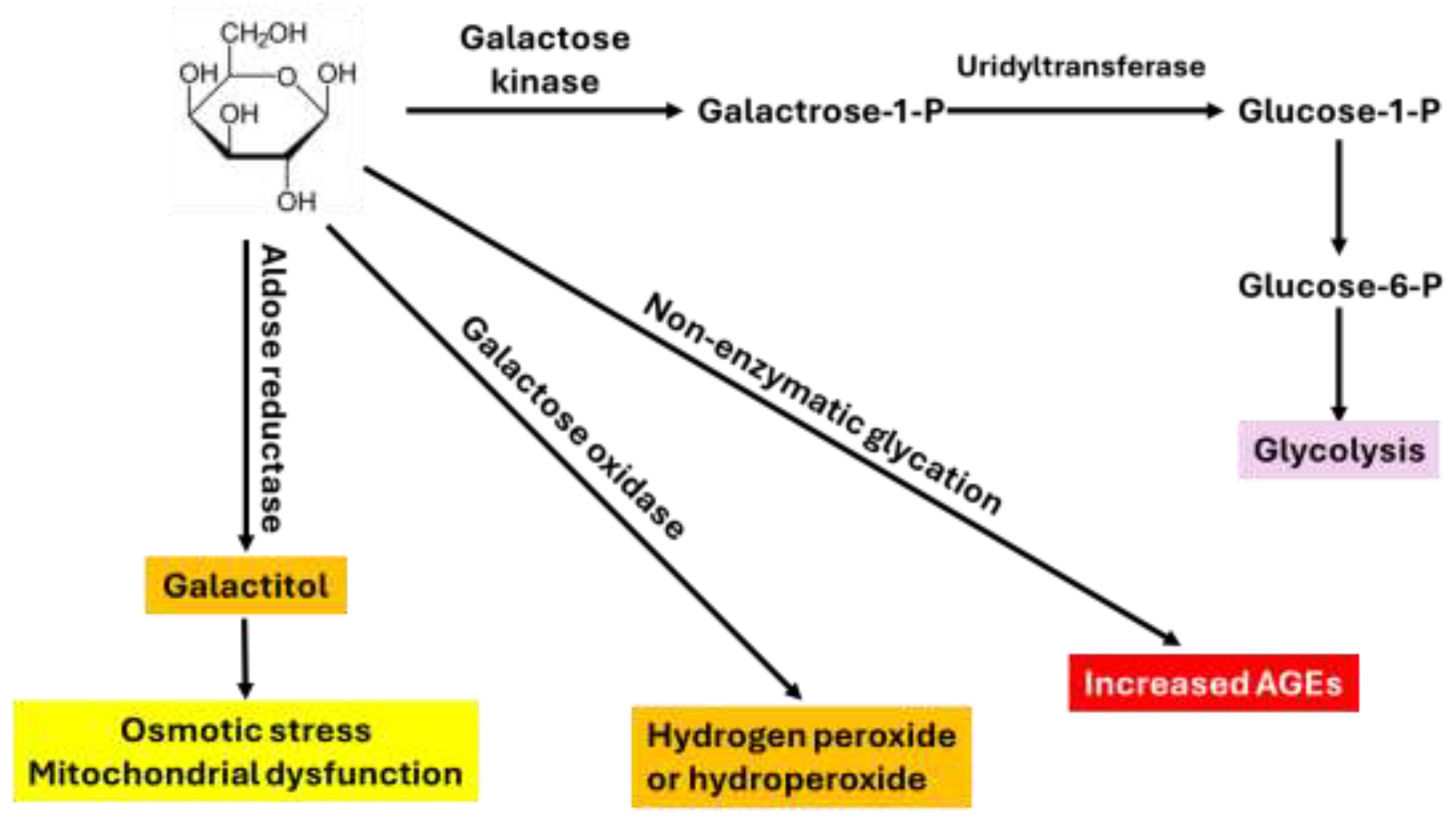

2. D-Gal Catabolism and Common Mechanisms of D-Gal Induced Aging

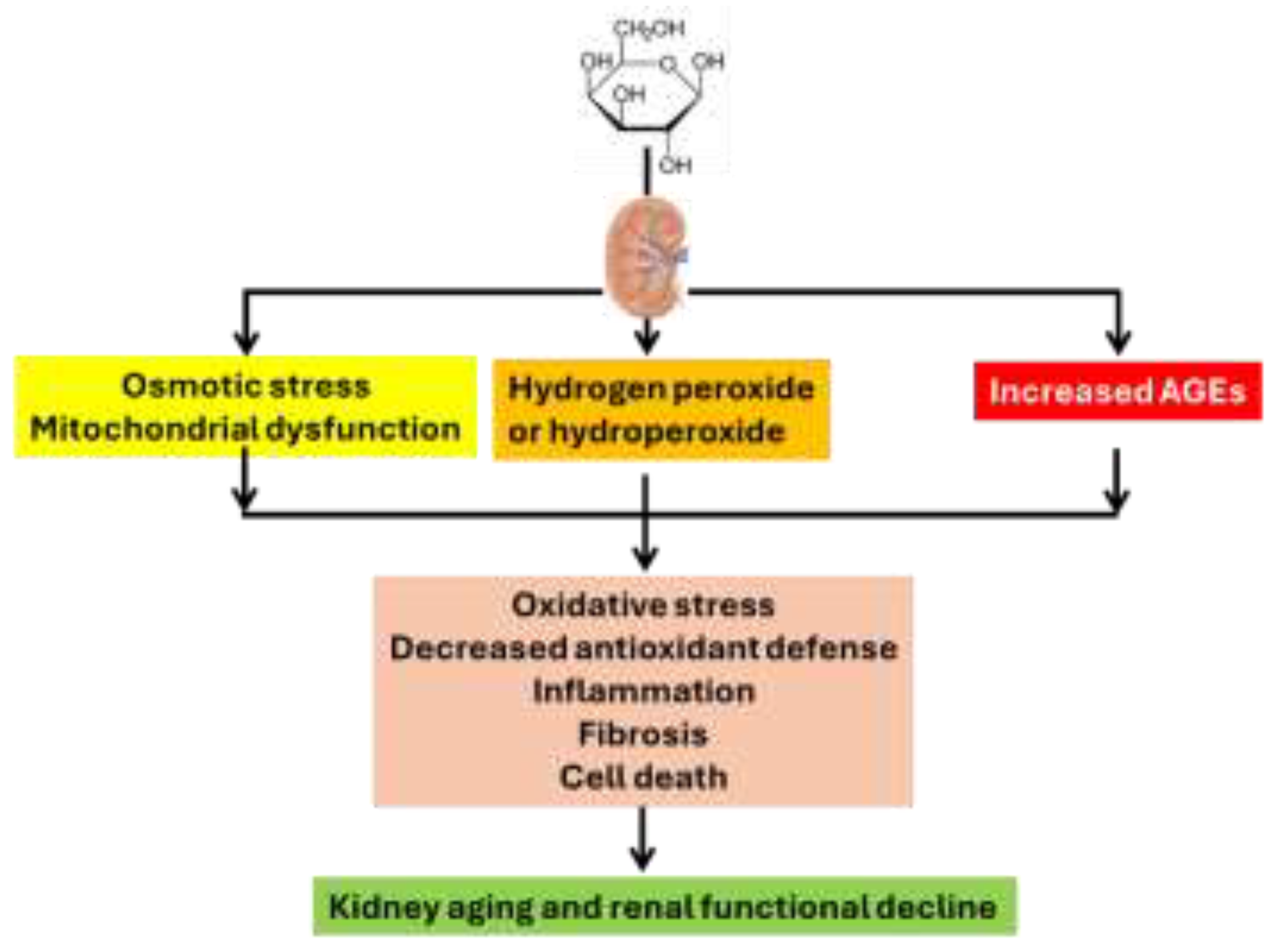

3. Kidney Aging Induced by D-Gal

3.1. Analysis of Oxidative Stress

3.1.1. Measurement of ROS

3.1.2. Measurement of Oxidative Damage to Macromolecules

3.1.3. Measurement of Antioxidant Defense System

3.1.4. Measurement of Inflammation and Fibrosis

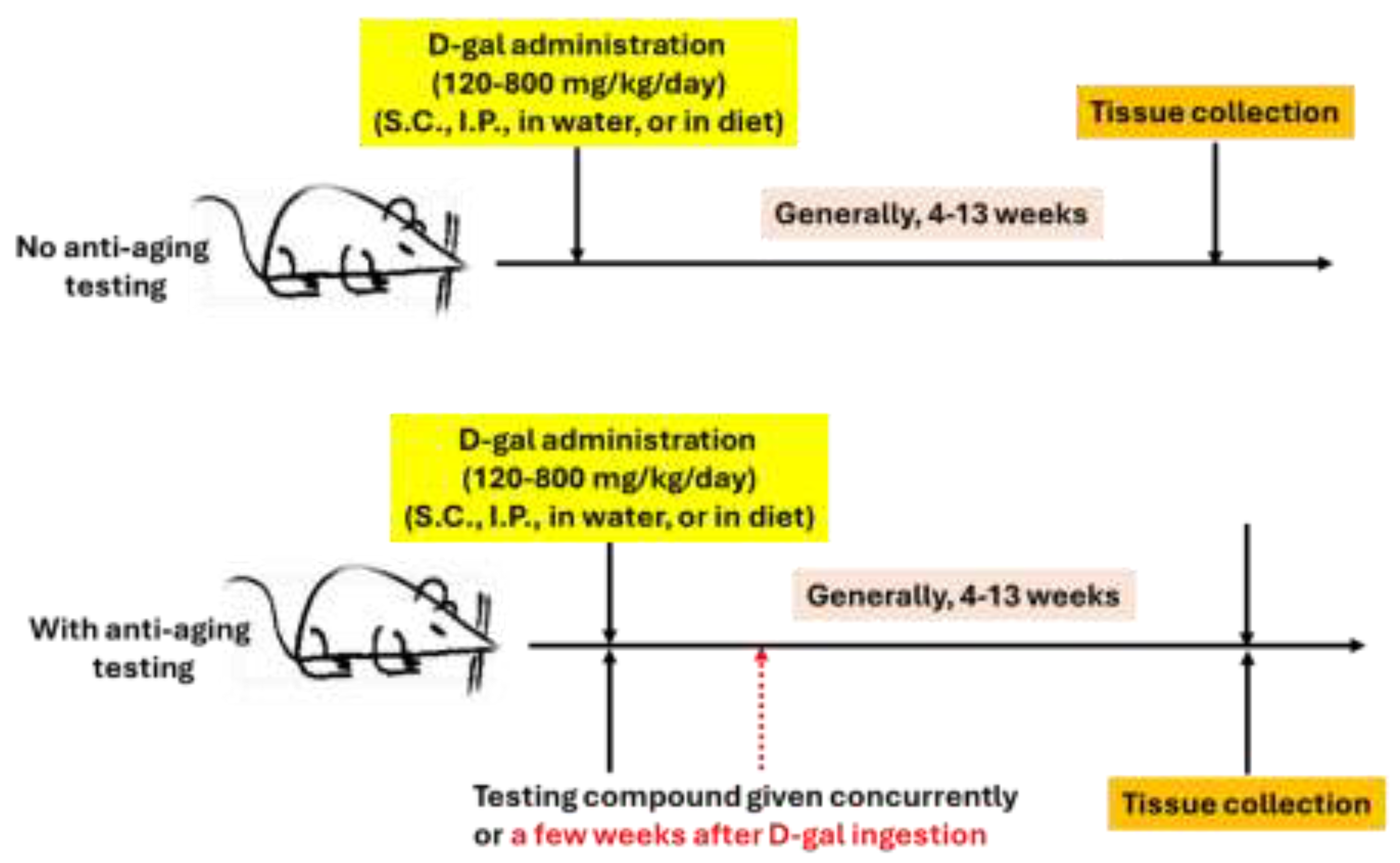

3.2. General Experimental Approaches of D-Gal Induced Aging in Rodents

4. D-Gal-Induced Aging Model as a Platform for Evaluating Anti-Kidney Aging Strategies

5. Miscellaneous

5.1. Synergistic Detrimental Effects with Risk Factors

5.2. D-Gal-Induced Aging as a Platform to Test the Anti-Aging Effects of Caloric Restriction Mimetics

5.3. Potential Difference Between D-Gal Oral Intake vs. D-Gal Injection

5.4. Effects of Ketone Bodies and Ketogenic Diet

5.5. Identification of Common Targets for Both Kidney Aging and CKD

6. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Conflicts: of Interest

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- Reed, S. Essential physiological biochemistry: An organ-based approach; Willey-Blackwell: Noida, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kamt, S.F.; Liu, J.; Yan, L.J. Renal-Protective Roles of Lipoic Acid in Kidney Disease . Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.; Peet, A. Marks’ Basic Medical Biochemistry: A clinical Approach, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yan, L.-J. The Role of Ketone Bodies in Various Animal Models of Kidney Disease. Endocrines 2023, 4, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, K. Aging Selectively Modulates Vitamin C Transporter Expression Patterns in the Kidney. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rex, N.; Melk, A.; Schmitt, R. Cellular senescence and kidney aging . Clin Sci (Lond) 2023, 137, 1805–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E. SGLT2 inhibition to target kidney aging . Clin Kidney J 2024, 17, sfae133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. A high-fat diet increases oxidative renal injury and protein glycation in D-galactose-induced aging rats and its prevention by Korea red ginseng. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2014, 60, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, K.A. Age sensitizes the kidney to heme protein-induced acute kidney injury . Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2013, 304, F317–F325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M. Renal aging and its consequences: navigating the challenges of an aging population. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1615681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. NUAK1 Promotes Diabetic Kidney Disease by Accelerating Renal Tubular Senescence via the ROS/P53 Axis. Diabetes 2025, 74, 2405–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapuskar, K.A. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of avasopasem manganese in age-associated, cisplatin-induced renal injury. Redox Biol 2024, 70, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Panesso, M. Acute kidney injury and aging . Pediatr Nephrol 2021, 36, 2997–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J. Autophagy-senescence interplay in kidney disease: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential. Mol Biol Rep 2025, 53, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, B. Molecular Mechanisms of AKI in the Elderly: From Animal Models to Therapeutic Intervention. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Li, X. Kidney Aging and Chronic Kidney Disease . Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahib, B.S. An Overview of Interplay Between Aging, D-Galactose and Oxidative Stress . Journal of Animal Health and Production 2025, 13, 1095–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. D-Galactose-induced accelerated aging model: an overview . Biogerontology 2019, 20, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Safdar, A.; Zakaria, R. D-galactose-induced liver aging model: Its underlying mechanisms and potential therapeutic interventions. Exp Gerontol 2021, 150, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. Fisetin, a potential caloric restriction mimetic, modulates ionic homeostasis in senescence induced and naturally aged rats. Arch Physiol Biochem 2022, 128, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, M.; Rizvi, S.I. Chitosan Displays a Potent Caloric Restriction Mimetic Effect in Senescent Rats . Rejuvenation Res 2021, 24, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H. Antioxidative potential of Lactobacillus sp. in ameliorating D-galactose-induced aging. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2022, 106, 4831–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Wardlaw’s perspectives in nutrition, 12th ed.; McGraw Hill: Columbus, Ohio, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. Luteolin attenuate the D-galactose-induced renal damage by attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation. Nat Prod Res 2015, 29, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Z. Diosgenin, a Novel Aldose Reductase Inhibitor, Attenuates the Galactosemic Cataract in Rats. J Diabetes Res 2017, 2017, 7309816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, D.; Kang, S.; Park, S. Association of Age-Related Cataract Risk with High Polygenetic Risk Scores Involved in Galactose-Related Metabolism and Dietary Interactions. Lifestyle Genom 2022, 15, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, U.; Chakrapani, U. Biochemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.B. Sub-acute toxicity of D-galactose. The second national conference on aging research, Harbin, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X. D-galactose-caused life shortening in Drosophila melanogaster and Musca domestica is associated with oxidative stress. Biogerontology 2004, 5, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L. L-theanine protects rat kidney from D-galactose-induced injury via inhibition of the AGEs/RAGE signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 927, 175072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaraju, M. Vitamin B12 modulates D-galactose-induced renal dysfunction . Indian J Med Res 2025, 162, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Impellizzeri, D. Memophenol(TM) Prevents Amyloid-beta Deposition and Attenuates Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in the Brain of an Alzheimer’s Disease Rat. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.H. Neuromodulatory effect of vardenafil on aluminium chloride/D-galactose induced Alzheimer’s disease in rats: emphasis on amyloid-beta, p-tau, PI3K/Akt/p53 pathway, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and cellular senescence. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 2653–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Ma, J.Q.; Lou, Y. Chronic administration of troxerutin protects mouse kidney against D-galactose-induced oxidative DNA damage. Food Chem Toxicol 2010, 48, 2809–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafa, A. 5-HT3 antagonist, tropisetron, ameliorates age-related renal injury induced by D-galactose in male mice: Up-regulation of sirtuin 1. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2024, 27, 577–587. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H. Alginate Oligosaccharide Ameliorates D-Galactose-Induced Kidney Aging in Mice through Activation of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 6623328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.M.; Unwin, R.J. The not so ‘mighty chondrion’: emergence of renal diseases due to mitochondrial dysfunction. Nephron Physiol 2007, 105, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Ou, L.; Yu, X. The antioxidant effect of Asparagus cochinchinensis (Lour.) Merr. shoot in D-galactose induced mice aging model and in vitro. J Chin Med Assoc 2016, 79, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y. Protective effects of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) peel phenolics on H(2)O(2)-induced oxidative damages in HepG2 cells and d-galactose-induced aging mice. Food Chem Toxicol 2017, 108, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. Chlorogenic acid protects D-galactose-induced liver and kidney injury via antioxidation and anti-inflammation effects in mice. Pharm Biol 2016, 54, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y. Mechanism of ginsenoside Rg1 renal protection in a mouse model of d-galactose-induced subacute damage. Pharm Biol 2016, 54, 1815–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.Z. Angelica sinensis Supercritical Fluid CO(2) Extract Attenuates D-Galactose-Induced Liver and Kidney Impairment in Mice by Suppressing Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. J Med Food 2018, 21, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Protective Effects of Selenium, Vitamin E, and Purple Carrot Anthocyanins on D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Damage in Blood, Liver, Heart and Kidney Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res 2016, 173, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, Z.Z. Protective Effect of SFE-CO(2) of Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort Against d-Galactose-Induced Injury in the Mouse Liver and Kidney. Rejuvenation Res 2017, 20, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jin, Z.; Yan, L.J. Redox imbalance and mitochondrial abnormalities in the diabetic lung. Redox Biol 2017, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.J. Mouse heat shock transcription factor 1 deficiency alters cardiac redox homeostasis and increases mitochondrial oxidative damage. EMBO J 2002, 21, 5164–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.J. Mouse HSF1 disruption perturbs redox state and increases mitochondrial oxidative stress in kidney. Antioxid Redox Signal 2005, 7, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, A.N. Alamandine: Protective Effects Against Renal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury-Induced Renal and Liver Damage in Diabetic Rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2025, 39, e70423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.P.; Ceron, J.J. Spectrophotometric assays for evaluation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in serum: general concepts and applications in dogs and humans. BMC Vet Res 2021, 17, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erel, O. A new automated colorimetric method for measuring total oxidant status. Clin Biochem 2005, 38, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.J. Analysis of oxidative modification of proteins . Curr Protoc Protein Sci 2009, Chapter 14, p. Unit14 4. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.J. Comparison between copper-mediated and hypochlorite-mediated modifications of human low density lipoproteins evaluated by protein carbonyl formation. J Lipid Res 1997, 38, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.J. Apolipoprotein B carbonyl formation is enhanced by lipid peroxidation during copper-mediated oxidation of human low-density lipoproteins. Arch Biochem Biophys 1997, 339, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.J.; Levine, R.L.; Sohal, R.S. Oxidative damage during aging targets mitochondrial aconitase . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 11168–11172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigenaga, M.K. In vivo oxidative DNA damage: measurement of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine in DNA and urine by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Methods Enzymol 1990, 186, 521–530. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.X. Increased Oxidative Damage of RNA in Early-Stage Nephropathy in db/db Mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017, 2017, 2353729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z. Puerarin alleviates cisplatin-induced acute renal damage and upregulates microRNA-31-related signaling. Exp Ther Med 2020, 20, 3122–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Yan, L.J. Two dimensional blue native/SDS-PAGE to identify mitochondrial complex I subunits modified by 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). Frontiers in Physiology 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. Low expression of SOD and PRX4 as indicators of poor prognosis and systemic inflammation in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol 2025, 15, 1614092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khani, A. Protective effects of crocin against contrast induced acute kidney injury following angiography: A randomized controlled clinical trial. ARYA Atheroscler 2025, 21, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K. Biological studies on exogenous NO stress to improve the quality of Radix Scutellariae herbs. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0339961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauchova, H. Glutathione Levels and Lipid Oxidative Damage in Selected Organs of Obese Koletsky and Lean Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Physiol Res 2024, 73, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X. Sensitive enzymatic cycling assay for glutathione and glutathione disulfide content. Anal Chim Acta 2025, 1369, 344348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F. Guidelines for antioxidant assays for food components . Food Frontiers 2020, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gendy, H.F. Bromhexine hydrochloride enhances the therapeutic efficacy of tiamulin against experimental Staphylococcus aureus infection in dogs: targeting bacterial virulence, boosting antioxidant defense, and improving histopathology. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1679854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S. Eight weeks of moderate aerobic exercise on body composition and markers of inflammation and oxidative stress in middle-aged obese females. J Exerc Rehabil 2025, 21, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, R. Ferulic acid ameliorates renal injury via improving autophagy to inhibit inflammation in diabetic nephropathy mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 153, 113424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Fucoxanthin alleviates renal aging by regulating the oxidative stress process and the inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo models. Redox Rep 2025, 30, 2511458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney disease: molecular mechanisms, pathogenic roles, and emerging small-molecule therapeutics. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1703560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Oxidative stress and inflammation in renal fibrosis: Novel molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Chem Biol Interact 2025, 421, 111784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Zhang, X.; Yan, L.J. Antioxidant activity, antitumor effect, and antiaging property of proanthocyanidins extracted from Kunlun Chrysanthemum flowers. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 983484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulow, R.D.; Boor, P. Extracellular Matrix in Kidney Fibrosis: More Than Just a Scaffold . J Histochem Cytochem 2019, 67, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. FoxM1 inhibition ameliorates renal interstitial fibrosis by decreasing extracellular matrix and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Pharmacol Sci 2020, 143, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Ferroptosis Activation Contributes to Kidney Aging in Mice by Promoting Tubular Cell Senescence. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2025, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. CAV1 Exacerbates Renal Tubular Epithelial Cell Senescence by Suppressing CaMKK2/AMPK-Mediated Autophagy. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. Mincle Maintains M1 Polarization of Macrophages and Contributes to Renal Aging Through the Syk/NF-kappaB Pathway. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2024, 38, e70062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, Y. BRD4 plays an antiaging role in the senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells. Transl Androl Urol 2024, 13, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B. Enhanced TRPC3 transcription through AT1R/PKA/CREB signaling contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction in renal tubular epithelial cells in D-galactose-induced accelerated aging mice. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. Cannabinoid receptor 2 plays a central role in renal tubular mitochondrial dysfunction and kidney ageing. J Cell Mol Med 2021, 25, 8957–8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X. Protocatechualdehyde attenuates oxidative stress in diabetic cataract via GLO1-mediated inhibition of AGE/RAGE glycosylation. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1586173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usiobeigbe, O.S. Biochemical and Histological effect of Moringa Oleifera Seed Aqueous Extract on Galactose-Induced Liver and Kidney Injury in Male Wistar Rat. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res 2024, 58, 50728–50739. [Google Scholar]

- Yagihashi, S. Galactosemic neuropathy in transgenic mice for human aldose reductase. Diabetes 1996, 45, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsyula, M. Oxidative stress in rats after 60 days of hypergalactosemia or hyperglycemia. Int J Toxicol 2003, 22, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B. Hyperoside attenuates renal aging and injury induced by D-galactose via inhibiting AMPK-ULK1 signaling-mediated autophagy. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 4197–4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, Y. Exogenous H(2)S alleviates senescence of glomerular mesangial cells through up-regulating mitophagy by activation of AMPK-ULK1-PINK1-parkin pathway in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2023, 1870, 119568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J. Fucoidan Oligosaccharide Supplementation Relieved Kidney Injury and Modulated Intestinal Homeostasis in D-Galactose-Exposed Rats. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. A serum-free adipose-conditioned medium delays stem cell senescence and maintains tissue homeostasis via IL-6/STAT3 axis suppression. Stem Cell Res Ther 2025, 16, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, X.Z.; He, X.L. Mild moxibustion attenuates vascular and renal aging in senescent rats by regulating the miR-34a/sirt1/p53 signaling pathway. Zhen Ci Yan Jiu 2025, 50, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Mirtajaddini Goki, M. The preventive effects of exercise on renal dysfunction in D-galactose treated rats: the role of miR-296-5p and SGLT2. Eur J Appl Physiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X. Moderate Beer Consumption Ameliorated Aging-Related Metabolic Disorders Induced by D-Galactose in Mice via Modulating Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13, e70678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B. Dendrobium officinale extract alleviates aging-induced kidney injury by inhibiting oxidative stress via the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 352, 120156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T. Inhibition of caspase-1 by ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorates d-gal-induced renal aging and injury through suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation. Ren Fail 2025, 47, 2504634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, H.S. Adropin contributes to the nephro-protective effect of vitamin D in renal aging in a rat model via MAPK/HIFalpha/VEGF/eNOS mechanism. J Nutr Biochem 2025, 143, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Investigating the renoprotective effects of Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides (PSP) on D-galactose-induced aging mice: insights from gut microbiota and metabolomics analyses. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1550971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J. The mechanism underlying of Zuoguiyin on liver and kidney in D-gal-induced subacute aging female rats: A perspective on SIRT1-PPARgamma pathway regulation of oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 347, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Association of alpha-Klotho with anti-aging effects of Ganoderma lucidum in animal models. J Ethnopharmacol 2025, 345, 119597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D. Protective Effects of Black Rice Anthocyanins on D-Galactose-Induced Renal Injury in Mice: The Role of Nrf2 and NF-kappaB Signaling and Gut Microbiota Modulation. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X. Arctium lappaL. polysaccharides alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation in the liver and kidney of aging mice by regulating intestinal homeostasis. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 280, 135802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.J. Renal protective effects of Alpinate Oxyphyllae Fructus and mesenchymal stem cells co-treatment against D- galactose induced renal deterioration. Int J Med Sci 2024, 21, 1491–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumsri, W. Box A of HMGB1 Maintains the DNA Gap and Prevents DDR-induced Kidney Injury in D-galactose Induction Rats. In Vivo 2024, 38, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. The protective effect of PL 1-3 on D-galactose-induced aging mice. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1304801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, S. Antioxidant and anti-aging role of silk sericin in D-galactose induced mice model. Saudi J Biol Sci 2023, 30, 103872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B. New Insight into the Potential Protective Function of Sulforaphene against ROS-Mediated Oxidative Stress Damage In Vitro and In Vivo. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureen, S. Effect of Lactobacillus brevis (MG000874) on antioxidant-related gene expression of the liver and kidney in D-galactose-induced oxidative stress mice model. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2023, 30, 84099–84109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, K.C. Resveratrol Alleviates Advanced Glycation End-Products-Related Renal Dysfunction in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.H. Effect of resveratrol on the repair of kidney and brain injuries and its regulation on klotho gene in d-galactose-induced aging mice. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2021, 40, 127913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. METTL3 alleviates D-gal-induced renal tubular epithelial cellular senescence via promoting miR-181a maturation. Mech Ageing Dev 2023, 210, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimizadeh, E. Gemfibrozil, a lipid-lowering drug, improves hepatorenal damages in a mouse model of aging. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2023, 37, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Various Fractions of Alcoholic Extracts from Dendrobium nobile Functionalized Antioxidation and Antiaging in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2022, 27, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M. KYA1797K, a Novel Small Molecule Destabilizing beta-Catenin, Is Superior to ICG-001 in Protecting against Kidney Aging. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2022, 8, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Effects of Rosa roxburghii Tratt glycosides and quercetin on D-galactose-induced aging mice model. J Food Biochem 2022, 46, e14425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakimizadeh, E. Calcium dobesilate protects against d-galactose-induced hepatic and renal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and pathological damage. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2022, 36, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase aberrations reinstates antioxidant aging suppressors and ameliorates renal aging. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.L. [Effects of astaxanthin combined with aerobic exercise on renal aging of rat induced by D-galactose and its mechanism]. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 2021, 37, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, J.Y. The p53/p21/p16 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways are involved in the ameliorative effects of maltol on D-galactose-induced liver and kidney aging and injury. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 4411–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, N. Effect of lithium chloride on d-galactose induced organs injury: Possible antioxidative role. Pak J Pharm Sci 2020, 33((4) (Supplementary)), 1795–1803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Rare Ginsenoside 20(R)-Rg3 Inhibits D-Galactose-Induced Liver and Kidney Injury by Regulating Oxidative Stress-Induced Apoptosis. Am J Chin Med 2020, 48, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Far, A.H. Quercetin Attenuates Pancreatic and Renal D-Galactose-Induced Aging-Related Oxidative Alterations in Rats. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. Ameliorative effect of urolithin A on d-gal-induced liver and kidney damage in aging mice via its antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic properties. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 8027–8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D. Protective effects of collagen polypeptide from tilapia skin against injuries to the liver and kidneys of mice induced by d-galactose. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 117, 109204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B. Preventive Effect of Small-Leaved Kuding Tea (Ligustrum robustum (Roxb.) Bl.) Polyphenols on D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Aging in Mice. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2019, 2019, 3152324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.Z. Anti-Aging Effect of Chitosan Oligosaccharide on d-Galactose-Induced Subacute Aging in Mice. Mar Drugs 2018, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.Z. Effects of rhein lysinate on D-galactose-induced aging mice. Exp Ther Med 2016, 11, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y. In Vivo Antioxidant and Anti-Skin-Aging Activities of Ethyl Acetate Extraction from Idesia polycarpa Defatted Fruit Residue in Aging Mice Induced by D-Galactose. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 2014, 185716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S. Effect of Regular Exercise on the Histochemical Changes of d-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Renal Injury in High-Fat Diet-Fed Rats. Acta Histochem Cytochem 2013, 46, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, Z. Protective effect of selenoarginine against oxidative stress in D-galactose-induced aging mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 2009, 73, 1461–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Protective Effect of Que Zui Tea on d-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress Damage in Mice via Regulating SIRT1/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Lycopene attenuates D-galactose-induced insulin signaling impairment by enhancing mitochondrial function and suppressing the oxidative stress/inflammatory response in mouse kidneys and livers. Food Funct 2022, 13, 7720–7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroojan, A.A. Effects of hydro-alcoholic extract of Vitex agnus-castus fruit on kidney of D-galactose-induced aging model in female mice. Iran J Vet Res 2016, 17, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.H. Protective effect of Artemisia annua L. extract against galactose-induced oxidative stress in mice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnumukkala, T. Centella asiatica ameliorates AlCl3 and D-galactose induced nephrotoxicity in rats via modulation of oxidative stress. Bioinformation 2024, 20, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R. The Impact of Antarctic Ice Microalgae Polysaccharides on D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Damage in Mice. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 651088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. The preventive effect of Apocynum venetum polyphenols on D-galactose-induced oxidative stress in mice. Exp Ther Med 2020, 19, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P. Characterization, evaluation of nutritional parameters of Radix isatidis protein and its antioxidant activity in D-galactose induced ageing mice. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019, 19, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R. Empagliflozin improves kidney senescence induced by D-galactose by reducing sirt1-mediated oxidative stress. Biogerontology 2023, 24, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Protective Effects of Ulva lactuca Polysaccharide Extract on Oxidative Stress and Kidney Injury Induced by D-Galactose in Mice. Marine Drugs 2021, 19, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somintara, S. Assessment of sub-chronic toxicity and anti-aging effects of a solid self-microemulsifying drug delivery system of Kaempferia parviflora extract in a D-galactose-induced rat model. Pharm Biol 2026, 64, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Daytime-Restricted Feeding Alleviates D-Galactose-Induced Aging in Mice and Regulates the AMPK and mTORC1 Activities. J Cell Physiol 2025, 240, e70020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, S. Sodium arsenite accelerates D-galactose-induced aging in the testis of the rat: Evidence for mitochondrial oxidative damage, NF-kB, JNK, and apoptosis pathways. Toxicology 2022, 470, 153148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Forster, M.J. Caloric restriction and the aging process: a critique . Free Radic Biol Med 2014, 73, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H. Sirtuin signaling in cellular senescence and aging . BMB Rep 2019, 52, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S. Calorie restriction mimetics against aging and inflammation . Biogerontology 2025, 26, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohal, R.S.; Weindruch, R. Oxidative stress, caloric restriction, and aging . Science 1996, 273, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z. Caloric restriction, Sirtuins, and cardiovascular diseases . Chin Med J (Engl) 2024, 137, 921–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watroba, M.; Szukiewicz, D. Sirtuins at the Service of Healthy Longevity . Front Physiol 2021, 12, 724506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R. Early Life Interventions: Impact on Aging and Longevity . Aging Dis 2024, 16, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A. Chrysin, a glycolytic inhibitor, modulates redox homeostasis during aging via a potent calorie restriction mimetic effect in male wistar rats. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. Spermidine protects cellular redox status and ionic homeostasis in D-galactose induced senescence and natural aging rat models. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci 2025, 80, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. Curcumin displays a potent caloric restriction mimetic effect in an accelerated senescent model of rat. Biol Futur 2023, 74, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Saraswat, K.; Rizvi, S.I. Glucosamine Displays a Potent Caloric Restriction Mimetic Effect in Senescent Rats by Activating Mitohormosis. Rejuvenation Res 2021, 24, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Saraswat, K.; Rizvi, S.I. 2 -Deoxy - d-glucose at chronic low dose acts as a caloric restriction mimetic through a mitohormetic induction of ROS in the brain of accelerated senescence model of rat. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2020, 90, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H. Metformin attenuates the D-galactose-induced aging process via the UPR through the AMPK/ERK1/2 signaling pathways. Int J Mol Med 2020, 45, 715–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safdar, A. Goat milk attenuates mimetic aging related memory impairment via suppressing brain oxidative stress, neurodegeneration and modulating neurotrophic factors in D-galactose-induced aging model. Biogerontology 2020, 21, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. Calorie restriction down-regulates expression of the iron regulatory hormone hepcidin in normal and D-galactose-induced aging mouse brain. Rejuvenation Res 2014, 17, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinovic, J. Chronic Oral D-Galactose Induces Oxidative Stress but Not Overt Organ Dysfunction in Male Wistar Rats. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2025, 47 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H. Ketone bodies: from enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med 2021, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Morales, P.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Tapia, E. Ketone bodies, stress response, and redox homeostasis . Redox Biol 2020, 29, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staretz-Chacham, O. The Effects of a Ketogenic Diet on Patients with Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutnik, A.P. Efficacy and Safety of Long-term Ketogenic Diet Therapy in a Patient With Type 1 Diabetes. JCEM Case Rep 2024, 2, luae102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, D. beta-Hydroxybutyrate, a ketone body, reduces the cytotoxic effect of cisplatin via activation of HDAC5 in human renal cortical epithelial cells. Life Sci 2019, 222, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T. Protective effects of exogenous beta-hydroxybutyrate on paraquat toxicity in rat kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2014, 447, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.L.; Hopp, K. Metabolic Reprogramming in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Evidence and Therapeutic Potential. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2020, 15, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athinarayanan, S.J. The case for a ketogenic diet in the management of kidney disease . BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. Identification of potential anti aging drugs and targets in chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y. Asiaticoside and asiatic acid improve diabetic nephropathy by restoring podocyte autophagy and improving gut microbiota dysbiosis. Biochem Pharmacol 2025, 241, 117161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.H. Asiatic acid inhibits endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in diabetic kidney disease by reducing acetyl-CoA production via targeting ACSS2. Biochem Pharmacol 2025, 242, 117311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| D-Gal dosage (mg/kg/day)/ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal models | route/duration | Specific mechanisms | Reference |

| Mouse | 300, S.C. 8 weeks, | Ferroptosis | [74] |

| Mouse | 500, S.C.,12 weeks | Caveolin-1 upregulation | [75] |

| Mouse | 500, S.C., 8 weeks | M1 macrophage polarization | [76] |

| Mouse | 150, I.P., 8 weeks | BRD4 upregulation | [77] |

| Mouse | 150, S.C., 8 weeks | Enhanced TRPC3 transcription | [78] |

| Mouse | 150, S.C., 6 weeks | Cannabinoid receptor 2 upregulation | [79] |

| Chemical/compound/ | D-gal-mg/kg/day | Mechanisms | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| drug/approach/species | duration/route | ||

| Serum free, adipose | |||

| conditioned medium/Mouse | 100, S.C., 8 weeks | Suppressing IL-6/STAT3 | [87] |

| Mild moxibustion/Rat | 300, I.P., 4 weeks | Sirt1/p53 signaling | [88] |

| Vitamin B12/Rat | 300, I.P., 120 days | Decreasing AGEs accumulation | [31] |

| Exercise/Rat | 150, S.C., 8 weeks | Decreased SGLT2 expression | [89] |

| Moderate beer consumption/Mouse | 25, S.C., 8 weeks | Modulating gut dysbiosis | [90] |

| Dendrobium officinale extract/Mouse | 120, S.C., 8 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [91] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1/Mouse | 120, I.P., 7 weeks | Suppressing oxidative stress/inflammation | [92] |

| Adropin/vitamin D/Rat | 120, I.P>, 8 weeks | MAPK/HIFα/VEGF/eNOS | [93] |

| Polygonatum sibiricum polysaccharides/Mouse | 150, I.P., 8 weeks | Modulating gut microbiota | [94] |

| Zuoguiyin (traditional Chinese medicine)/Rat | 125, S.C., 8 weeks | Sirt1/PPARγ signaling | [95] |

| Ganoderma lucidum/Mouse | 600, S.C., 8 weeks | Increasing α-klotho expression | [96] |

| Black rice anthocyanins | 500, S.C., 13 weeks | Nrf2/NF-kB signaling | [97] |

| Fucoidan oligosaccharide/Rat | 150, S.C., 8 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [86] |

| Arctium lappaL. Polysaccharides/Mouse | 150, I.P., 8 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [98] |

| Alpinate oxyphyllae fructus/Rat | 150, N/A, 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress/inflammation | [99] |

| Box A of HMGB1/Rat | 150, S.C., 8 weeks | Inhibiting DNA damage | [100] |

| Tropisetron/Mouse | 200, S.C., 8 weeks | Sirt1 upregulation | [35] |

| Piperlongumine 1-3/Mouse | 500, I.P. 10 weeks | Sirt1 upregulation | [101] |

| Silk sericin/Mouse | 250, I.P., 60 days | Diminishing oxidative stress | [102] |

| Sulforaphene/Mouse | 300-800, S.C. varying | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [103] |

| Exogenous hydrogen sulfide/Mouse | 150, S.C., 10 weeks | Mitophagy activation | [85] |

| Lactobacillus brevis/Mouse | 300, S.C., 5 weeks | Increased antioxidant enzymes | [104] |

| Resveratrol/Mouse | 1000, S.C.,8 weeks | Decreasing AGEs | [105] |

| Resveratrol/Mouse | 1 mg/kg, I.P., 4 weeks | Increasing klotho expression | [106] |

| Methyltransferase-like protein 3/Mouse | 500, S.C., 8 weeks | Promoting miR-181a maturation | [107] |

| Gemfibrozil/Mouse | 150, I.P., 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [108] |

| Dendrobium nobile alcohol extract/Mouse | 125, S.C., 8 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [109] |

| β-catenin inhibitors, KYA1797K/Mouse | 150, S.C., 6 weeks | Suppressing mitochondrial dysfunction | [110] |

| Rosa roxburghii tratt glycosides-quercetin/Mouse | 100, S.C, 6 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [111] |

| Calcium dobesilate/Mouse | 500, P.O., 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [112] |

| Klotho/Mouse | 500, S.C., 6 weeks | Inhibiting DNA methyltransferase | [113] |

| Astaxanthin/exercise/Rat | 100, I.P., 6 weeks | Nrf2 activation | [114] |

| Maltol/Mouse | 800, I.P., 7 weeks | p53/p21/p16, PI3K/Akt pathways | [115] |

| Lithium chloride/Rat | 300, I.P., 6 weeks | Increasing enzymatic antioxidants | [116] |

| Alginate oligosaccharide/Mouse | 200, S.C., 8 weeks | Nrf2/NQO1/HO-1 activation | [36] |

| 20(R)-ginsenoside Rg3/Mouse | 800, S.C., 8 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [117] |

| Quercetin/Rat | 120, S.C., 6 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [118] |

| Urolithin A/Mouse | 150, S.C., 8 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress/inflammation | [119] |

| Collagen polypeptide | 300, S.C., 8 weeks | Attenuating oxidative stress | [120] |

| Small-leaved Kuding tea polyphenols/Mouse | 120, I.P., 6 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [121] |

| Chitosan oligosaccharide/Mouse | 250, S.C., 8 weeks | Anti-oxidative stress | [122] |

| Rhein lysinate/Mouse | 100, S.C., 8 weeks | Enhancing antioxidant activity | [123] |

| Chlorogenic acid/Mouse | 100, S.C., 8 weeks | Antioxidation, anti-inflammation | [40] |

| Korea red ginseng/Rat | 100, I.P. 8 weeks | Suppressing oxidative injury | [8] |

| Ethyl acetate extraction from Idesia polycarpa | 100, S.C., 6 weeks | Anti-oxidation | [124] |

| Exercise/Rat | 100, I.P., 9 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [125] |

| Selenoarginine/Mouse | 150, S.C., 6 weeks | Enhanced antioxidant defense | [126] |

| Que Zui tea/Mouse | 300, S.C., 10 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [127] |

| Lycopene/Mouse | \150, I.P., 8 weeks | Improving insulin signaling | [128] |

| L-theanine/Rat | 200, S.C., 8 weeks | Decreasing AGEs’ toxicity | [30] |

| Vitex agnus-castus extracts | 500, S.C., 45 days | Suppressing apoptosis | [129] |

| Vitamin E/selenium/carrot anthocyanins | 400, I.P., 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [43] |

| Artemisia annua L extract | 100, S.C., 6 weeks | Enhancing antioxidants | [130] |

| Troxerutin/Mouse | 500, S.C., 8 weeks | Inhibiting DNA damage | [34] |

| Angelica sinensis extract | 200, S.C., 8 weeks | Attenuating oxidative stress | [42] |

| Centella asiatica/Rat | 60, I.P., 70 days | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [131] |

| Antarctic ice microalgae polysaccharides/Mouse | 120, I.P., 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [132] |

| Apocynum venetum polyphenols/Mouse | 120, I.P., 6 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [133] |

| Radix isatidis protein/Mouse | 800, S.C., 7 weeks | Anti-oxidation | [134] |

| Ginsenoside Rg1/Mouse | 120, S.C., 6 weeks | Alleviating oxidative stress | [41] |

| Empagliflozin/Mouse | 800, S.C., 8 weeks | Inhibiting sirt1/oxidative stress | [135] |

| Ulva Lactuca polysaccharide/Mouse | 400, S.C., 10 weeks | Inhibiting oxidative stress | [136] |

| Moringa Oleifera see aqueous extract/Rat | 30% in water, 4 weeks | Increasing SOD expression | [81] |

| Hyperoside/Rat | 300, S.C., 4- and 8-weeks | Inhibiting autophagy | [84] |

| Kaempferia parviflora extract | 50, I.P., 60 days | Decreasing lipid peroxidation | [137] |

| Day-time restricted feeding/Mouse | 100, I.P., 16 weeks | Attenuating renal damage | [138] |

| CR mimetics | Reference |

|---|---|

| Chrysin | [147] |

| Fisetin | [20] |

| Spermidine | [148] |

| Curcumin | [149] |

| Chitosan | [21] |

| Glucosamine | [150] |

| 2-Deoxy-d-glucose | [151] |

| Metformin | [152] |

| Goat milk | [153] |

| Caloric restriction per se | [154] |

| Day time restricted feeding | [138] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).