1. Introduction

Aging is a natural and complex process that involves a series of biological changes over time. It involves a variety of molecular and cellular changes, such as DNA damage, telomere shortening, and the accumulation of cellular waste products [

1]. These are associated with oxidative stress by cell hoarding of oxygen reactive species (ROS), leading closely to inflammation [

2]. Inflammation is characterized by an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines; interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), even in the absence of overt infection or injury [

3]. This sterile inflammation is believed to play a role in the development of various age-related diseases and affect multiple systems including kidneys. Senescent cells in the renal tubular epithelium contribute to renal aging and are associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines and fibrosis markers [

4,

5,

6]. The accumulation of senescent cells leads to a pro-inflammatory environment, often referred to as "inflammaging," which exacerbates kidney damage and fibrosis in aged individuals [

5,

7]. For example, aberrantly activated lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (LPAR1) is associated with chronic inflammation and renal fibrosis in aged kidneys and blocking it may reduce excessive inflammation in aged mice, suggesting sterile inflammation leading to fibrosis occurs in kidney during aging process [

4].

Inflammatory response is a key driven factor in aging process in kidneys. Aged mice experienced more severe acute kidney injury (AKI) compared to young mice with increased pro-inflammatory pathways and cellular senescence [

5]. AKI is associated with increased inflammation and cellular senescence, leading to higher mortality and morbidity in older patients [

7]. Kidney where is resident and recruited macrophages, increased macrophage infiltration in aged mice contributes to chronic low-grade inflammation and fibrosis in aged kidneys, with ferroptosis signalling playing a crucial role [

6]. Research evidence intestinal microbiota rejuvenation reduces renal interstitial fibrosis and delays renal senescence in aged male mice by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway [

8]. Additionally, probiotic supplementation can improve renal function and fibrosis in elderly mice by reducing intestinal inflammation and promoting M1-dominant renal inflammation [

9]. Therefore, there has been a crosstalk of gut-kidney axis in maintenance homeostasis, microbiota or their metabolites may have a promising effect on kidney inflammation in aged mice either direct or indirect way. The gut microbiota experiences substantial shifts as one ages, which affects both its diversity and functional capacity. These shifts may lead to greater gut permeability and an increase in systemic inflammation [

10,

11,

12].

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when taken in sufficient quantities, provide health benefits to the host [

13]. Most used probiotics include bacteria belonging to the

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium genera [

14].

Lactobacillus, notably, have proven to be an important genus with numerous beneficial biological characteristics. Potentially,

L. reuteri LR12 and

L. lactis LL10 illustrate positively scavenging activity of 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH) free radical, hydroxyl radical, and superoxide radical [

15]. More specifically to a mixture of

L. acidophilus La-14,

L. casei Lc-11,

L. lactis Ll-23,

B. lactis Bl-04 and

B. bifidum Bb-0, has been shown to lower the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 [

16]. In this context,

L. paracasei HII01 demonstrates the most significant impact on promoting longevity and anti-aging effects in

Caenorhabditis elegans [

17]. Based on our evidence,

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei MSMC39-1 (formerly name:

Lactobacillus paracasei MSMC39-1), previously, isolated from neonatal feces manifested anti-inflammatory effect on alcohol-induced hepatitis in rats and dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in rats [

18,

19]. Gaining insight into the processes of sterile inflammation and fibrosis in aging kidneys is essential for creating effective treatment strategies. This study aimed to assess the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of the probiotic

L. paracasei MSMC39-1 in an aging mouse model. Our findings suggest that

L. paracasei MSMC39-1 may serve as a beneficial anti-aging probiotic, potentially slowing down the aging processes in the kidneys and offering a foundation for supplements aimed at preventing age-related diseases and enhancing gut health.

3. Discussion

Aging is associated with physiological alterations in the body that can result in diminished functionality and the emergence of diseases, such as dementia, cardiovascular ailments, diabetes mellitus, and several chronic conditions, including kidney diseases [

22]. Probiotics is one of the saftest supplementations that has potential to protect or restore the aging process. Probiotics have been suggested that they relief systemic cytokine makers, improved antioxidant level resulting to anti-aging effects [

23]. The kidney plays a vital role in the aging process and is susceptible to the effects of oxidative stress and inflammation. This study investigates the kidneys of aging mice, based on a model created by Flurkey et al. (2007). In this model, young mice are represented by those aged 3–6 months, while the aging group consists of mice aged 18–24 months [

24]. It is consistent with the mice ages in our study. The probiotic MSMC39-1 was administered to mice starting in middle age and continued throughout their old age. The results indicated that treatment leads to significant improvements in oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in the kidneys of aging mice, highlighting the important roles of probiotics in antioxidant and anti-inflammation.

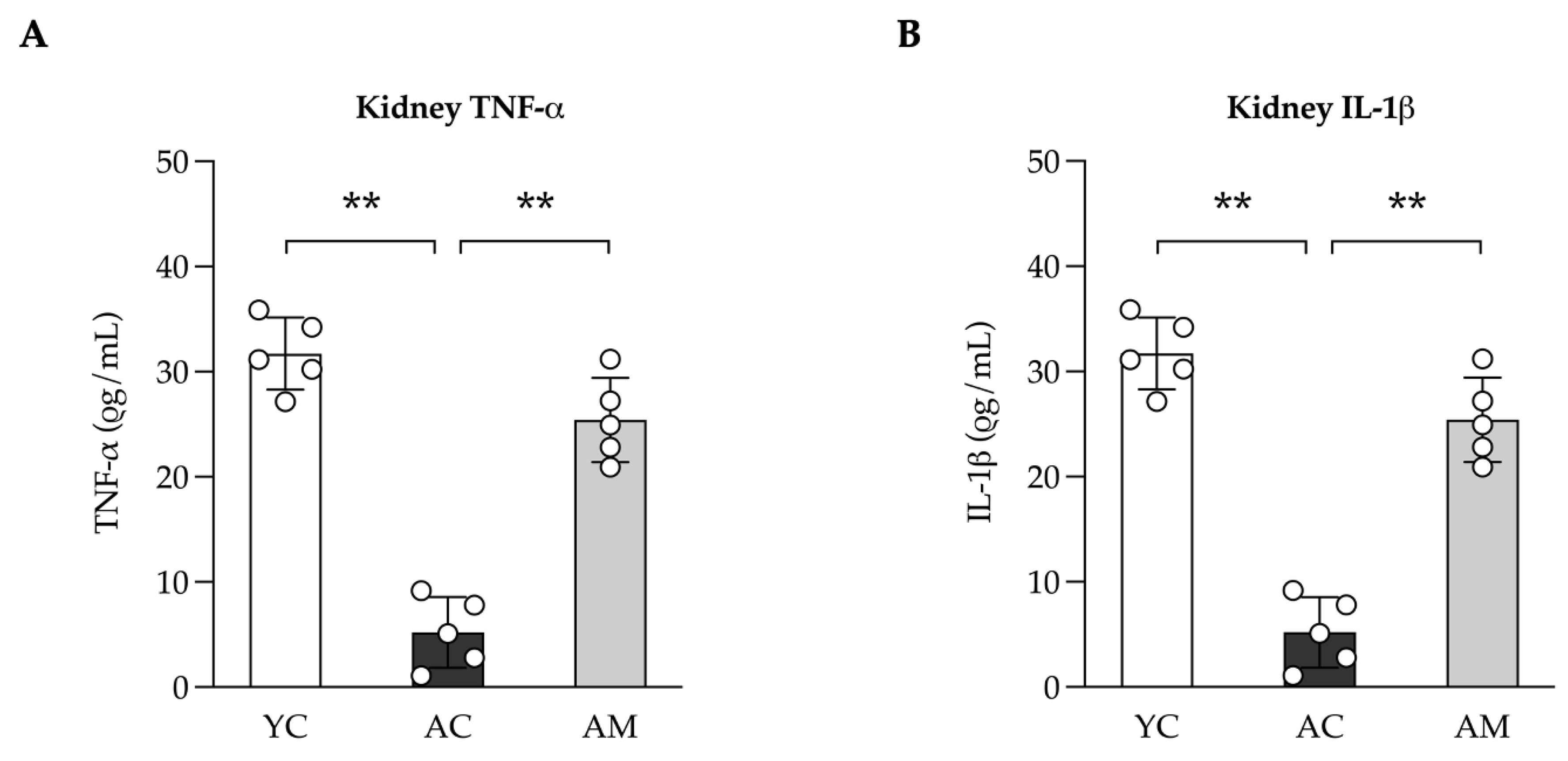

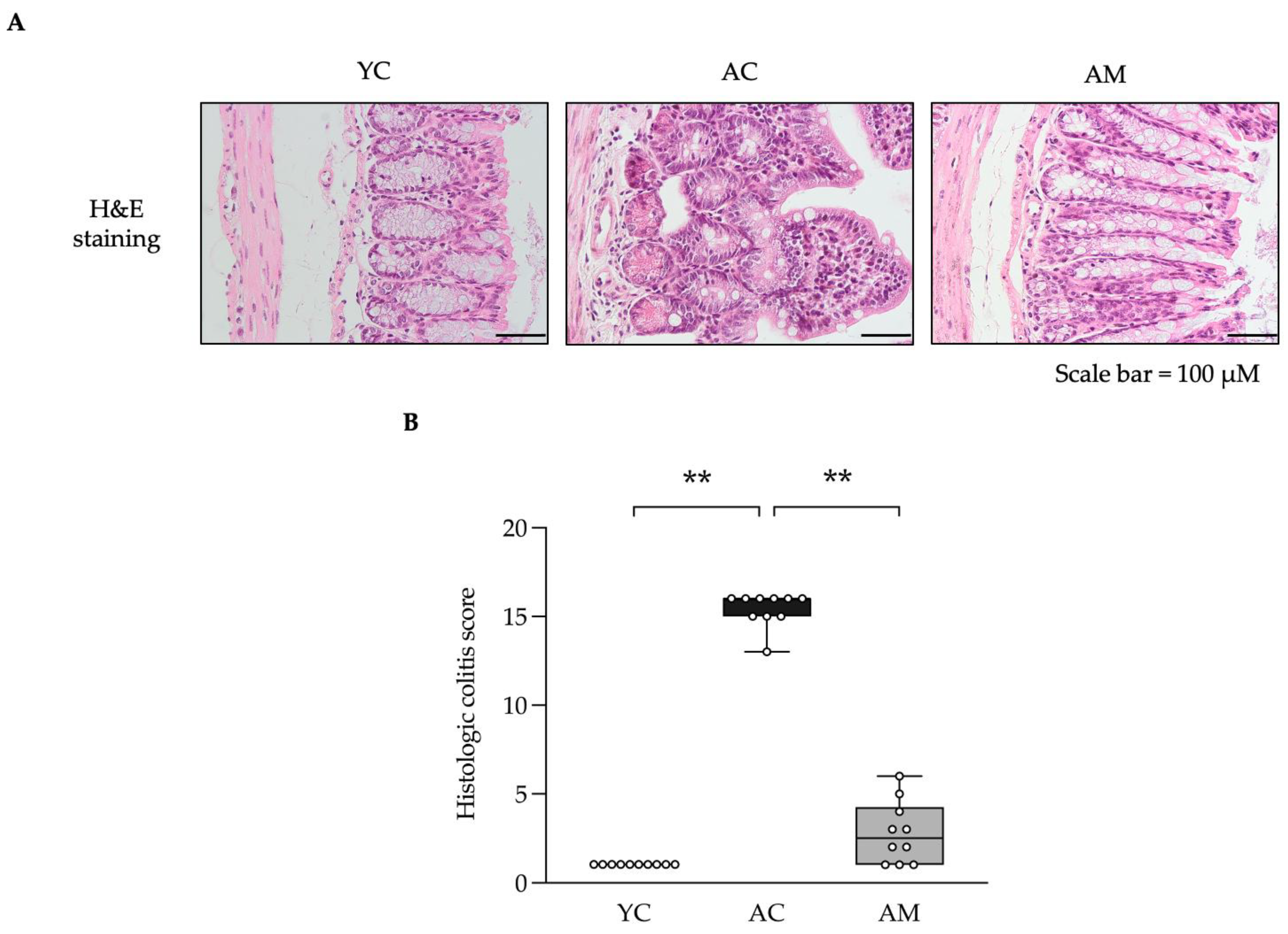

Kidney fibrosis is a common pathological condition linked to aging, characterized by the excessive buildup of extracellular matrix components, leading to tissue scarring and reduced renal function. Our research demonstrates that MSMC39-1 effectively prevents collagen accumulation associated with aging through various cellular and molecular mechanisms, including inflammation, and oxidative stress. MSMC39-1 inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines, highlighting the connection between inflammation and fibrosis. In agreement,

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei HY7207 has shown efficacy in reducing hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [

25]. While the study focused on liver health, the mechanisms by which

Lacticaseibacillus paracasei reduce inflammation and fibrosis in the liver could

potentially be applicable to the kidneys and other tissues, this suggests the systematic effect of probiotics supplementation in mouse model. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in the kidneys, which may result in various complications and a decline in renal function [

26]. As a result, the findings align with the work of Wagner et al. (2022), indicating that dysbiosis facilitates the colonization of bacteria that produce urease, indole, and p-cresol-forming enzymes, ultimately leading to the accumulation of uremic toxins [

27]. We did not measure those toxic agents produced in aged kidney, but tissue inflammation was probably due to toxic agents’ accumulation in aged organ in our model. Instead, we found that blood glucose is being increased in aged mice, this is likely to be a damaged molecule in aged mice that leads to systematic effect. In addition, studies indicate that the use of

Lactobacillus paracasei and

Lactobacillus plantarum can lead to improved kidney function and a reduction in inflammation, potentially serving as a preventive measure against the progression of chronic kidney disease [

28]. This is achieved through the enhancement of the downregulation of harmful metabolites, uremic toxin. Likewise, probiotics develop natural defenses that inhibit harmful bacteria, including those that generate uremic toxins. Recent research has demonstrated that the administration of probiotics can modify the intestinal microbiota in aging mice, resulting in improved outcomes for both acute and chronic kidney injuries [

9]. MSMC39-1 supplementation exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines level; IL-1β and TNF-α in aged kidney mice. Similarly, colon histology score, immune cell infiltration, crypt length distortion, and villi damaged in aged mice is also rescued by MSMC39-1 supplementation. This effect underscores probiotic properties such as immune system modulation via communication between renal and the gut system, which are known as gut-kidney axis. Moreover, strains of

L. paracasei have demonstrated the ability to enhance the integrity of the gut barrier by elevating the levels of tight junction proteins and mucin, thereby contributing to the reduction of inflammation and the preservation of gut health [

29,

30]. This is crucial in preventing conditions like colitis and other inflammatory bowel diseases [

29,

30].

L. paracasei X11 supplementation has been shown to lower serum uric acid levels and reduce renal inflammation, which is beneficial in preventing chronic kidney disease [

31]. This suggests a protective role in the gut-kidney axis.

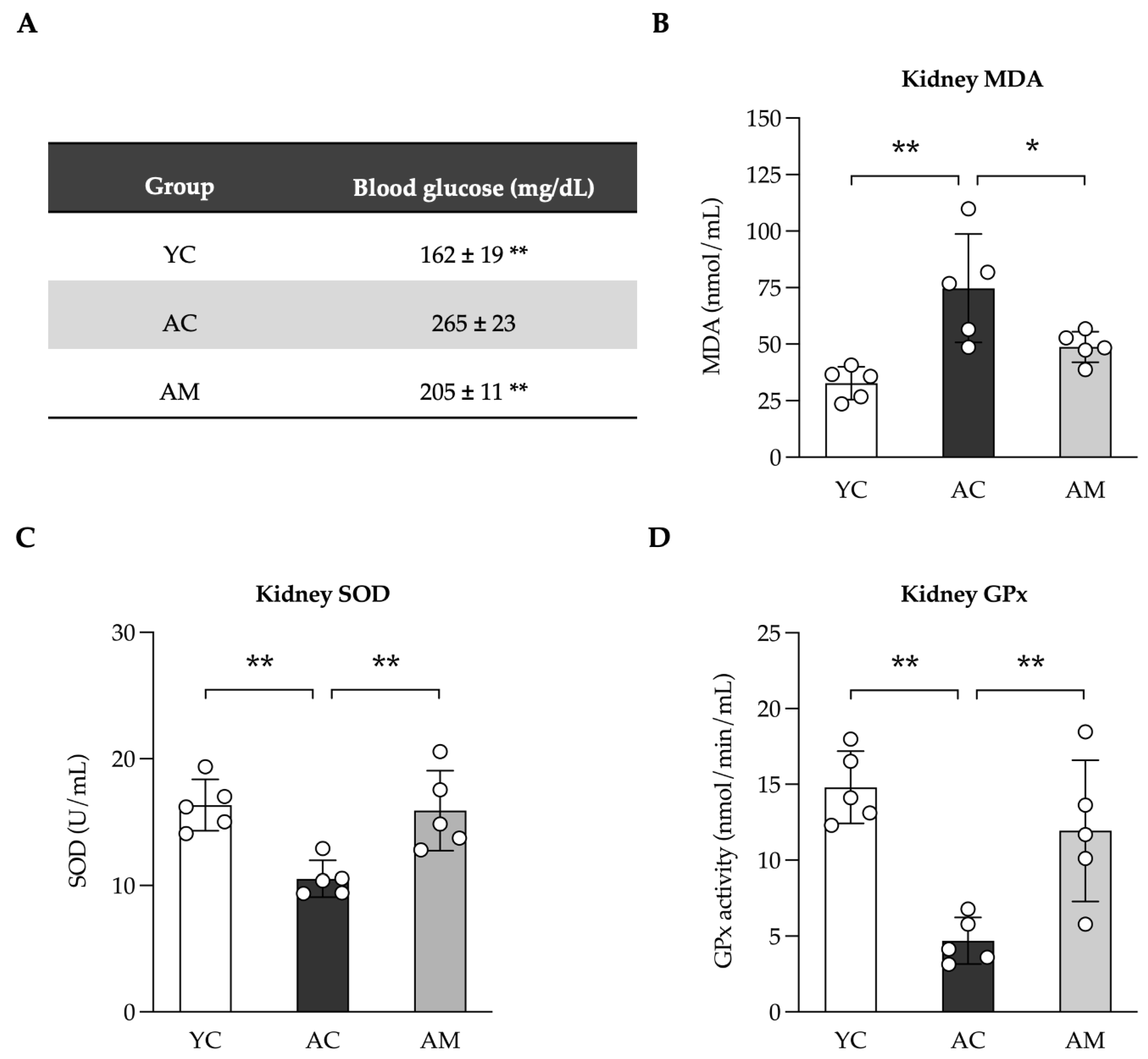

Aging in kidneys is characterized by increased inflammation and oxidative stress, which further promote fibrosis. This can be achieved through several mechanisms, including NF-κB, along with the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

32,

33]. Our research indicates that the restoration of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in the kidneys of aged mice may be attributed to the inhibitory influence of NF-κB activation, as both TNF-α and IL-1β are recognized as well-characterized target genes of NF-kB. We found both cytokines are significantly restored in aged kidney that is consistent with improved kidney histology. Nevertheless, we were unable to establish a clear link between oxidative stress and inflammation, as both factors may exacerbate each other in a feedback loop. An imbalance between the production and neutralization of ROS results in the onset of oxidative stress [

34]. As a result, an overabundance of hydroxy radicals can damage cell membranes, resulting in lipid peroxidation. This process subsequently elevates the levels of MDA in aging kidneys. The study revealed that MSMC39-1 reduces MDA levels while enhancing the activities of SOD and GPx in the kidney. Based on these findings, an examination of the organ's morphology was conducted, which may correlate with the antioxidative levels indicated by H&E staining. In alignment with the findings of Oguntoye et al. (2023), it was observed that Wistar rats receiving provitamin A cassava hydrolysate in conjunction with

Lactobacillus rhamnosus exhibited a notable enhancement in antioxidant biomarkers within their kidneys, heart, and liver [

35]. In individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD), the use of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics has been associated with improvements in markers of oxidative stress, such as elevated glutathione (GSH) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC); however, the specific impacts on GPx and SOD remain unspecified [

36]. This indicates potential for probiotics to enhance overall antioxidant capacity, which could indirectly benefit kidney function. The ability of probiotic MSMC39-1 to neutralize free radicals at the cellular and tissue levels is apparent. This aligns with the findings of Lin et al. (2022), which showed that the combination of

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium probiotics elevates SOD, catalase, and GPx levels in the brain and liver, while decreasing MDA levels in mice undergoing natural aging [

37].

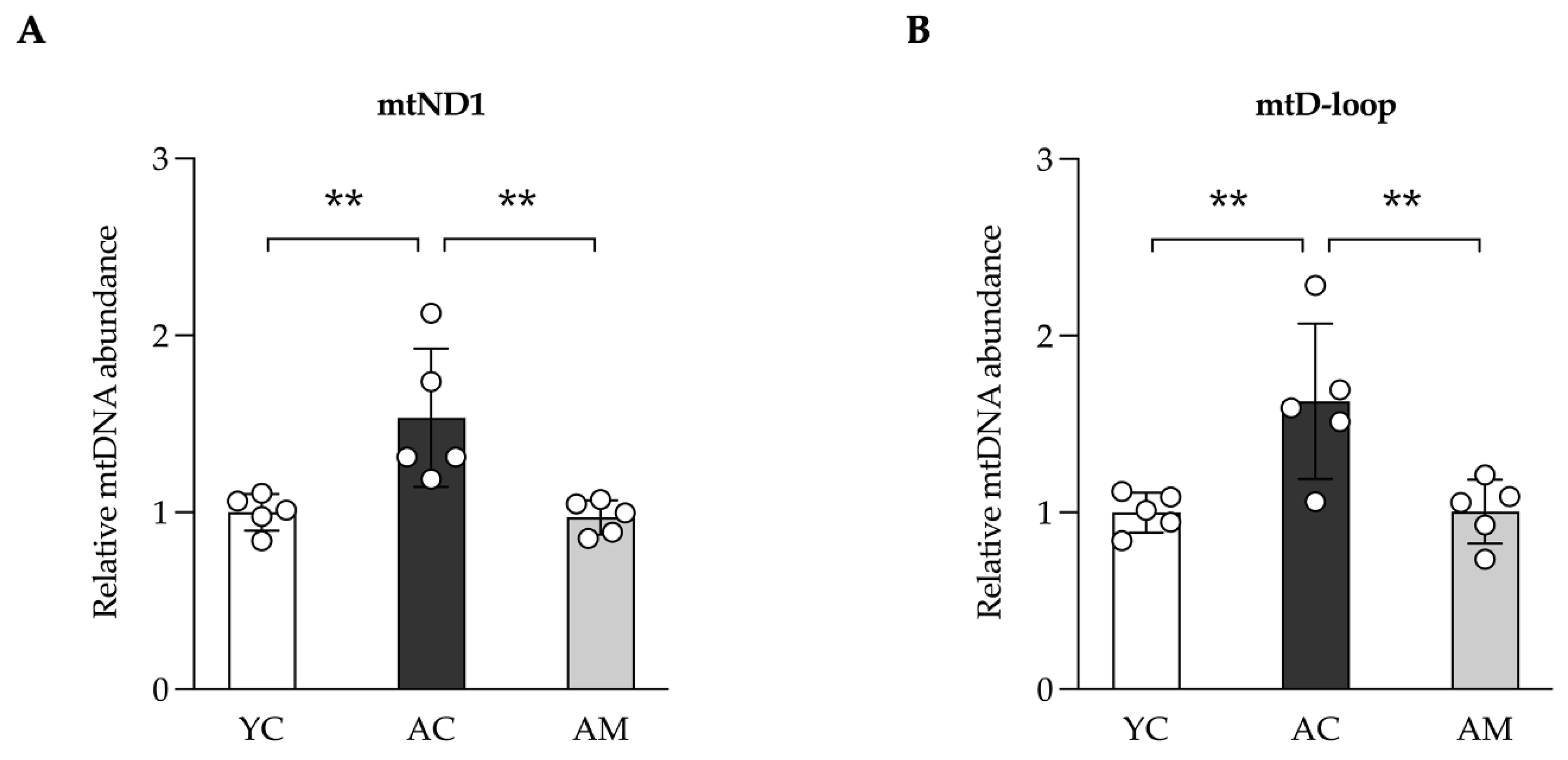

Findings from a population-based study suggest that higher levels of fasting glucose are related to glomerular hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria in adults of middle age, in contrast to insulin resistance measures, which do not exhibit such a connection [

38]. Our research indicated that aged mice exhibited an increased blood glucose level, which aligns with kidney damage characterized by fibrosis and inflammation. The heightened glucose levels in aging mice contribute to kidney fibrosis and inflammation via multiple mechanisms, such as cellular senescence and oxidative stress. How did MSMC30-1 has an effect in improving inflammation and oxidative stress in aged kidney remains elusive. We observed in aging kidneys, mtDNA levels are elevated, correlating positively with inflammation, oxidative stress, and histological changes. This suggests that increased glucose levels may lead to mitochondrial damage, either directly or indirectly. Additionally, aging kidneys seem to activate compensatory mechanisms to reduce mitochondrial damage by enhancing the production of new mitochondria, thereby maintaining cellular energy and function, as indicated by mtDNA levels. Research indicated that a reduction in cytochrome c levels within kidney mitochondria plays a significant role in the impairment of oxidative phosphorylation in older rats. This decline is essential for the process of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and results in diminished mitochondrial function in the kidneys of aged rats [

39]. Moreover, aging is associated with a reduction in mitochondrial mass and function, which exacerbates renal fibrosis and cellular senescence, primarily through the activation of Wnt/catenin/RAS signaling pathways that are implicated in age-related renal fibrosis [

40]. Studies have found that high levels of glucose aggravate renal inflammation and fibrosis through multiple pathways, including cellular senescence and the production of inflammatory cytokines. One study highlights that elevated glucose induces senescence in renal tubular epithelial cells, resulting in increased fibrosis and inflammation in diabetic kidney disease. This mechanism is driven by the secretion of Sonic hedgehog (Shh), which mediates the activation and proliferation of fibroblasts in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [

41]. Future studies are required to evaluate how gut microbiome in aged gut and kidney is being altered by supplementation MSMC39-1. In addition, how dose MSMC39-derived metabolites involve mitigating the inflammatory and oxidative stress in aged kidney are also needed to address.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Vero Cells Culture

The African green monkey kidney cell line, known as Vero cells (CCL-81) was obtained by Dr. Sakdiphong Punpai, Inovative Learning Center and Center of Excellence in Medical and Environmental Innovative Research (CEMEIR), Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand. Cells were regularly maintained in a medium consisting of DMEM low glucose with 1000 mg/L D-glucose and sodium pyruvate (Hyclone, USA). This medium was enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin (Hyclone, USA). The Vero cells were incubated at a temperature of 37 °C in a humidified incubator continuously flushed with a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

4.2. Probiotic Strain and Culture Conditions

A probiotic Lacticaseibacillus paracasei MSMC39-1 strain was sourced from Center of Excellence in Probiotics, Faculty of Medicine, Srinakharinwirot University, Bangkok, Thailand. The probiotics was cultivated in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) medium (HiMedia Lab., Mumbai, India) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively. Afterwards, the bacterial suspension density was adjusted to 109 colony forming units (CFU) in phosphate-buffered saline for oral administration in the mice. For in vitro experiment, supernatant culture was collected and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Then, the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 µm and stored at -80 °C until use.

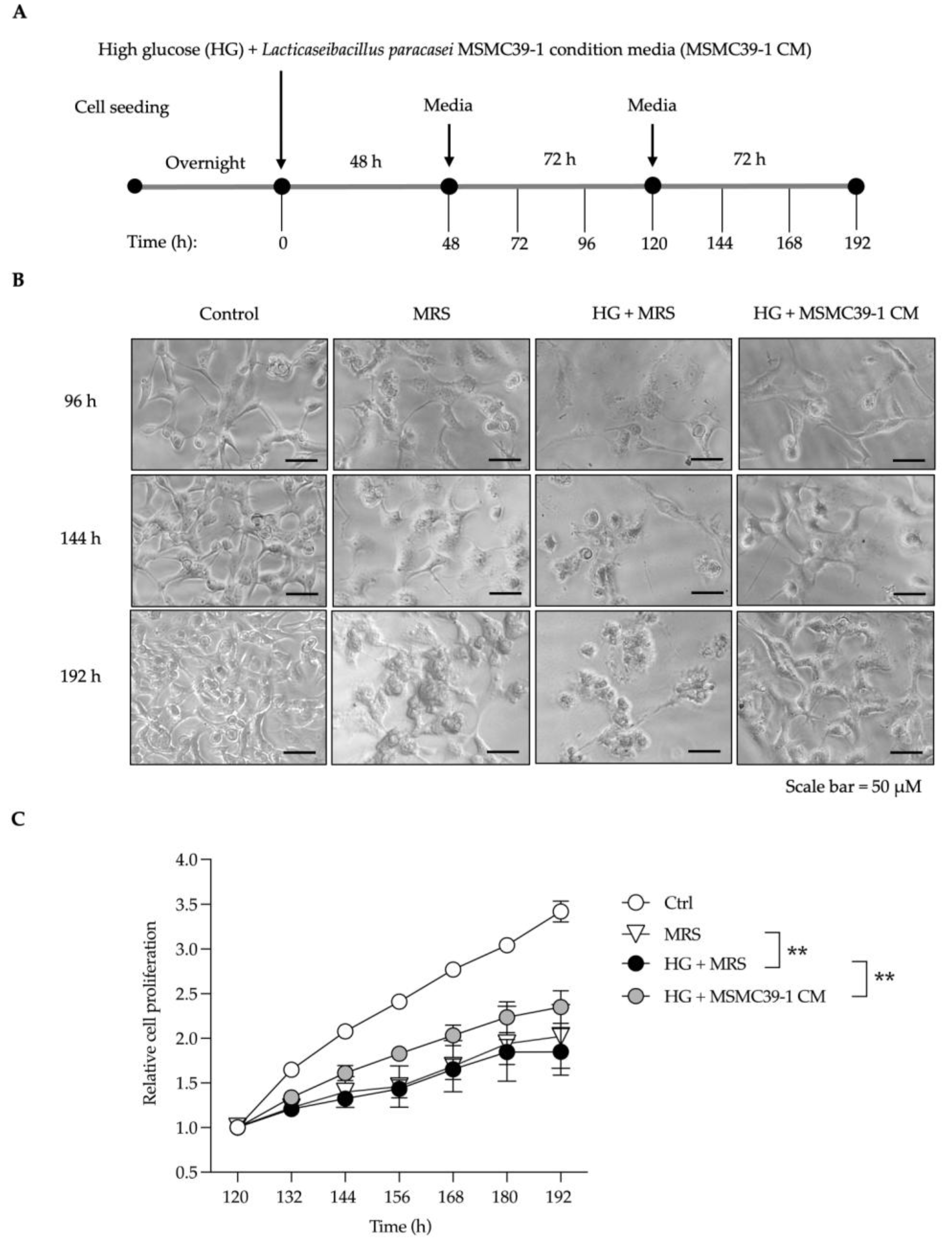

4.3. In Vitro Cell Damaging Induced by Glucose Experiment

Vero cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2,000 cells per 100 µl and incubated overnight. The next day, they were treated with high glucose (Sigma, USA) at 25.5 mM, with and without conditioned medium, for 48 hours. The medium was then replaced with fresh warm low glucose medium, and the cells were maintained until day 8. Throughout this period, the cells were monitored and photographed using a Matero TL Digital Transmitted Light Microscope (Leica Microsystems). Cell proliferation was assessed using the WST-8 (MedChem Express, USA) assay at 460 nm with a Multiskan SkyHigh (Thermo Scientific).

4.4. Mitochondria DNA Measurement

Total genomic DNA was extracted from kidney tissue using GF-1 Tissue DNA Extraction (Vivantis, Malasia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ten nanograms of total cellular DNA was used as a template for mitochondria DNA amplification by real time PCR with the following sequences encoded for mtDNA ND1 (mtND1) 5’ CTAGCAGAAACAAACCGGGC 3’, 5’ CCGGCTGCGTATTCTACGTT 3’; mtDNA D-loop (mtD-loop) 5’ AATCTACCATCCTCCGTGAAACC 3’, 5’ TCAGTTTAGCTACCCCCAAGTTTAA 3’; Total cellular mtDNA was normalized using endogenous genomic HK2; 5’ GCCAGCCTCTCCTGATTTTAGTGT 3’, 5’ GGGAACACAAAAGACCTCTTCTGG 3’.

Total cellular mtDNA was quantified by ExcelTaq™ 2X Fast Q-PCR Master Mix (SYBR, ROX) (SMBIO, Taiwan) using the StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The relative abundance of total mtDNA level was calculated using = 2

(-∆∆Cq) according to reference method [

42].

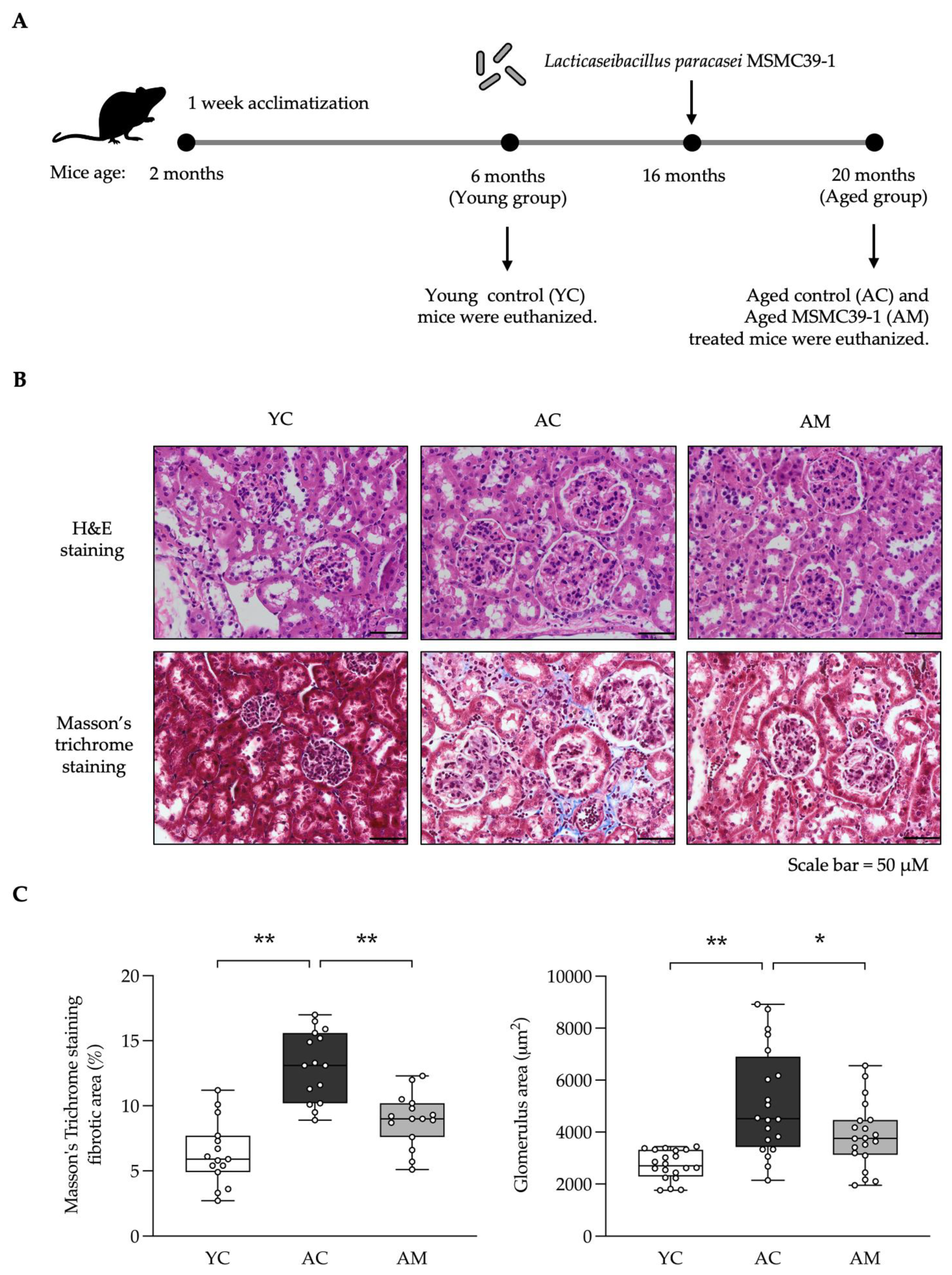

4.5. Experimental Animals

Two-month-old male C56BL/6NJcl mice (Mus musculus) were purchased from Nomura Siam International Co, Ltd (Bangkok, Thailand). Animal experiments were carried out according to the guidelines of the Ethics and Research Standardization Section, Srinakharinwirot University (approval number: COA/AE-015-2564). In short, all mice were housed in a room under controlled temperature and humidity ranges of 22± 2°C and 55± 10%, respectively, on 12 h light–dark cycle and free access to food and water. After 1 week of acclimatization, mice were randomly divided by the design of the aim of this study following into three groups: (1) young group aged 6 months, (2) aging group aged 20 months, and (3) MSMC39-1 group aged 20 months. MSMC39-1 group was fed normal food and water freely for 14 months, then received 100 µL MSMC39-1 via oral gavage at 109 CFU/mL for 4 months then were euthanized.

4.6. Organ Collection and Preparation

The mice were euthanized using isoflurane anesthesia. Briefly, their abdomens were opened, and the diaphragm barrier between the lungs and liver was cut for reaching the heart and excision, then mice died peacefully without pain. After that, the kidney and colon were all removed. The organs were stored at -80 °C then homogenization. The 50-100 mg of kidney was weighed and homogenized in 500 µL 10% (w/v) RIPA buffer using an ultrasonic homogenizer (Sonoplus HD 2070; Bandelin, Germany) at 25-30% power for 3 min. All procedures were performed on ice. Thereafter, the homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. Each supernatant was collected and stored at -80 °C for inflammatory cytokines measurement and oxidative stress study. Histopathological analysis: the samples were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde for 48 hours. The kidney was sliced in 4 µm thickness and colon was sliced in 5-7 µm thickness. All organs were prepared for further study.

4.7. Blood Glucose Evaluation

The blood sample was collected by heparinized blood and centrifuged at 1500 x g for 15 min at 4 °C. Total sugar was measured using plasma by the Professional Laboratory Management Corp, Co., Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand.

4.8. Inflammatory Cytokines Evaluation by ELISA

The samples were measured inflammatory cytokines; TNF-α and IL-1β, using mouse TNF-α DuoSet ELISA (#DY410-05, Minnepolis, MN), a Mouse IL-1 beta/IL-1F2 DuoSet ELISA (#DY401-05, Minnepolis, MN). All the operations were performed under the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, ELISA plate (#DY990, R&D systems) was coated with capture antibody overnight at 4 °C. After washing the plate, reagent diluent was added for blocking the wells and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature. Next, the wells were washed and added supernatant (100 µL/well) overnight at 4 °C. Each supernatant was washed off and incubated with detecting antibody for 2 h at room temperature. The streptavidin-HRP and substrate were added for starting the reaction. After that, the wells were added stop solution and read at 450 nm using Biochrom microplate reader (Anthos 2010, Austria). The concentration of TNF-α, IL-1β were calculated using a standard curve which obtained from TNF-α, IL-1β (mouse) ELISA standard following the manufacturer’s protocols.

4.9. Lipoperoxidation and Anti-Oxidative Stress Evaluation

The samples were measured oxidative markers, including Superoxide dismutase (SOD), Malondialdehyde (MDA) using TBARS Assay Kit (#10009055, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan), and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) using Superoxide Dismutase Kit (#706002, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan), and Glutathione (GPx) using Glutathione Peroxidase Assay Kit (#703102, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan). All the operations were performed under the manufacturer’s protocols. The specific absorbance was read using Biochrom microplate reader (Anthos 2010, Austria). Each activity of enzymes was measured following the manufacturer’s protocols and using a standard curve.

4.10. Histopathological Analysis

The kidney and colon tissues were labeled with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In addition, kidney tissue was labeled with Masson’s Trichrome for fibrosis. The stained sections were observed and examined under a light microscope (OlympusBX53, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Masson’s Trichrome staining positive area and glomerulus area were analyzed using ImageJ software. For colitis manifestation, the sections were graded by two independent investigators blinded to the different cohorts. Score ranged from 0 to 18 (total score), which represents the sum of the scores from grade of inflammation (0-3), extent within the intestine layers (0-3), regeneration (0-4), crypt damage (0-4) and percentage of involvement (0-4), as following

Table 1.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 software, the bars on the graph depict mean ± SD. The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Values of p < 0.05 and 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and T.J.; methodology, P.S., J.N., K.W., C.C. and P.J.; software, P.S. and J.N.; validation, T.J. and J.N.; formal analysis, P.S., J.N. and K.W.; investigation, P.S., J.N., K.W., C.C., and P.J.; resources, M.T. and T.J..; data curation, P.S., J.N. and T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, T.J., M.T. and J.N..; visualization, T.J., M.T. and J.N.; supervision, M.T. and T.J.; project administration, M.T.; funding acquisition, M.T. and T.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.