1. Introduction

AKI affects 10–15% of hospitalised patients, but in critical care, it has been documented to affect over 50% of patients [

1]. A sudden loss of excretory kidney function is the hallmark of acute kidney injury (AKI). AKI is a component of a group of illnesses often referred to as acute kidney diseases and disorders (AKD), in which kidney function slowly deteriorates or persists and is linked to an irreversible loss of nephrons and kidney cells, which can result in chronic kidney disease (CKD) [

2]. While AKI resulting from general surgical procedures is rare (approximately 1% of cases), it can occur in up to 70% of individuals who are very sick. Sepsis has been the most frequent cause of AKI in critically sick individuals [

3]. Based on the ideas presented, the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative has developed a definition of acute kidney injury. The Acute Kidney Injury Network has provided general support for these RIFLE (risk, injury, failure, loss, and end stage) criteria [

4].

Few suggested treatment compounds that have been shown to be protective in these animals have been successfully translated into clinical practice to yet. The clinical efficacy of prospective therapeutic drugs, which limit harm in the animal but not in people, has therefore not been predicted by animal models of AKI, despite the model’s high efficacy in reproducing pathology and biomarker traits discovered in humans [

5]. The maladaptive repair following acute kidney injury (AKI) in animals, which is typified by fibrosis, vascular rarefaction, tubular loss, glomerulosclerosis, and persistent interstitial inflammation, has been better understood. This state is similar to accelerated kidney ageing and consequently functional decline [

6]. Novel AKI models have been created using rodents and non-rodents, such as zebrafish and drosophila. AKI patients are now undergoing clinical trials for a number of treatments found in animal models, such as bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells and p53 RNAi. It’s possible that improved animal models combined with ongoing and new studies could eventually result in clinical AKI treatments that work [

7]. A new strategy is needed for septic AKI because of its unique pathogenesis. The pathogenesis, diagnostic techniques, and suitable treatment strategies in sepsis remain highly controversial despite remarkable progress in various medical domains. When compared to other critically sick patients, several immunomodulatory drugs that have shown promise in preclinical research are unable to lower the alarmingly high fatality rate of sepsis and cause AKI. Few animal models that closely resemble human sepsis, a relative lack of specialised diagnostic tools, and limited histopathologic data are the main obstacles to the understanding, early identification, and use of effective therapy modalities in sepsis-induced AKI. Further more research is required to fully comprehend the underlying processes of sepsis-induced AKI, the features of animal models, biochemical parameters of blood, histopathology and possible treatment options [

8]. An important part of the pathophysiology of sepsis-induced AKI is played by oxidative stress and inflammation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by LPS stimulation can influence the pathophysiology of sepsis by two different mechanisms: pathological damage to cells and organs, and modulation of the innate immune signalling cascade [

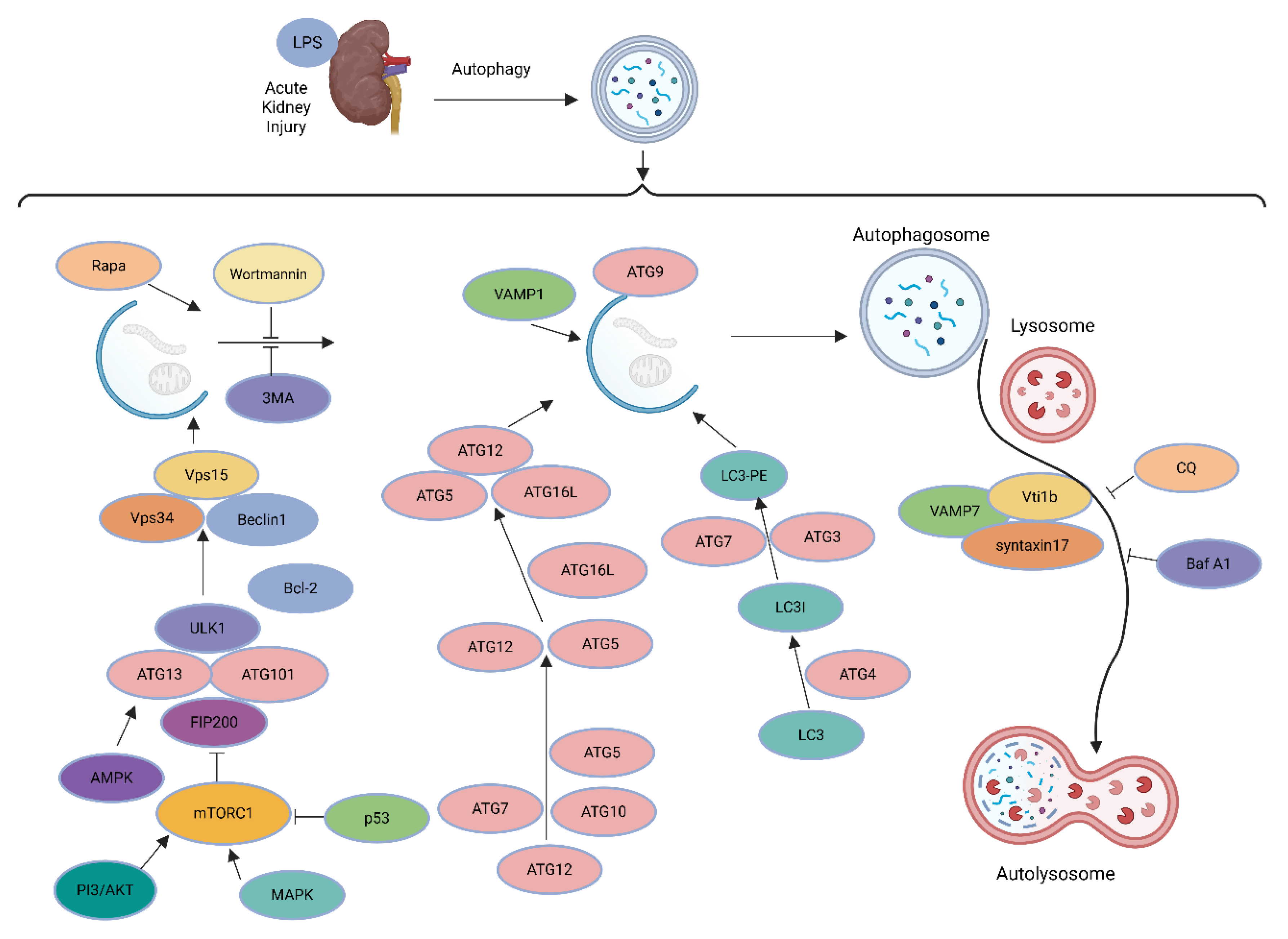

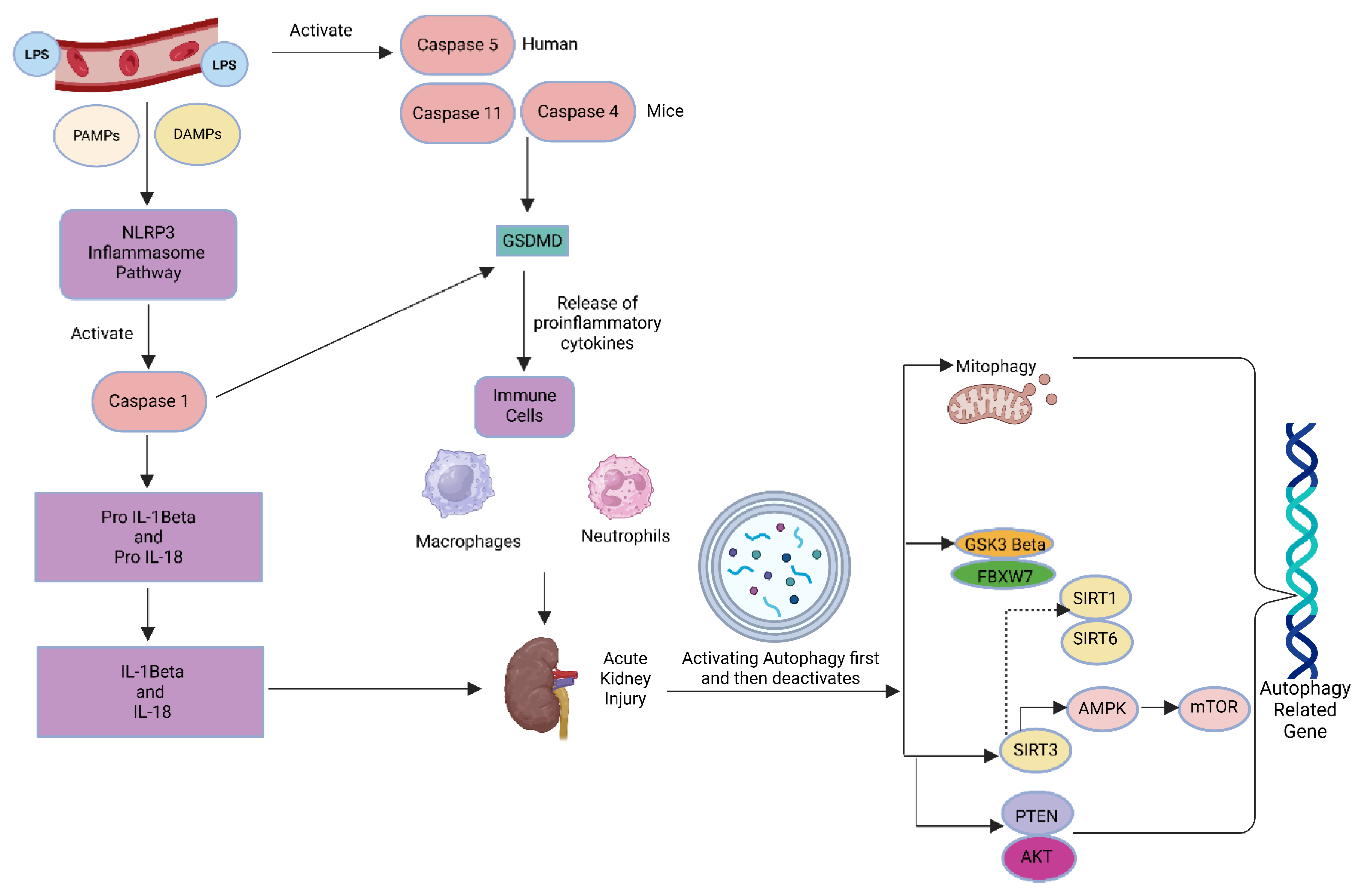

9]. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can promote the release of inflammatory cytokines and activate the nuclear factor-κB pathway, as shown in

Figure 1 [

33]. LPS is also one of the main causes of AKI [

10].

The kidney can heal itself after AKI, but if the damage was significant, the repair might not be complete or maladaptive, which could lead to chronic kidney disease. In addition to being involved in the pathophysiology of renal disorders and playing a significant role in preserving renal function, autophagy is also activated in different kinds of AKI and serves as a protective mechanism against damage and death of kidney cells. Although autophagy’s significance in maladaptive kidney repair has been debatable, it is maintained at a comparatively high level in kidney tubule cells following AKI [

22]. A dynamic alteration in autophagy throughout the recovery phase of AKI appears to be critical for tubular growth and repair [

23]. Deletion of essential autophagy proteins reduced renal function while increasing p62 levels and oxidative stress. In AKI models, deleting autophagy in proximal tubules increased tubular damage and renal function, demonstrating that autophagy is renoprotective. In addition to nonselective sequestration of autophagic cargo, autophagy can aid in the selective breakdown of damaged organelles, particularly mitochondrial degradation via mitophagy.

Damaged mitochondria increase in autophagy-deficient mice’s kidneys after ischemia-reperfusion injury, but the precise mechanisms regulating mitophagy in AKI remain unknown [

24]. Two ubiquitin-like cascades are combined into the ATG5-12-16L1 complex (Conjugation I) and conjugate LC3/GABARAPs onto phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) on the phagophore membrane (Conjugation II, to form LC3-II). The ATG5-12-16L1 complex, targeted by binding of WIPI2 to PI3P/RAB11A, defines conjugation sites.

The phagophore grows (engulfing bulk cargo or selectively through receptors such as P62), seals into an autophagosome, separates from the RAB11A platform, and merges with lysosomes to degrade the cargo [

25,

26]. Energy-sensitive kinases mTORC1 and AMPK, which are essential components of AKI, have been shown to regulate autophagy. mTORC1 phosphorylates ULK1/2 and Atg13, inhibiting ULK1/2 kinase activity and hence adversely regulating autophagy. AMPK promotes autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1 and activating ULK1/2 kinase [

24].

2. Materials and Methods

Materials; Every chemical used was of laboratory quality, and it was acquired from reputable suppliers providing in India (Dehradun, Uttarakhand).

Animals

Male 8-week-old BALB/c mice weighing 20 gm were obtained from NIB (National Institute of Biologicals), Noida, Delhi NCR. All mice were kept in our facility at 25°C and on a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to pelleted diet and water. The Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of UPES, Dehradun authorised each experiment, which followed standard guidelines for ethical animal care and operation of animals in scientific research.

We conducted this study in three phases, first; Prepared a 1 mg/mL stock solution of LPS (E. coli O111.B4) in normal saline (0.9%NaCl). Male mice of age 8 weeks were used. We divided our mice in two groups randomly having 2 mice in each group, one control group and one LPS treated Group. A dose of 1 mg/kg body weight LPS was injected in 2 mice intraperitoneally. 1-2 hours post high dose LPS injection, mice looked morbidant. Due to the higher concentration of the LPS both the LPS treated mice died before 24 hours. So, we collected the kidneys for the Histopathological analysis to see the level of Injury in the Kidney.

In the second phase, we reduced the concentration of the LPS to less than half of the earlier one in order to increase mice life span, our aim was to exceed it beyond 24 hours in order to collect blood samples for biochemical tests. This time we took 1 mouse in each group LPS quantity, 250ug/kg BW, 125 ug/Kg BW, and the control group. 24 hours post LPS treatment mice were sacrificed after blood sample collection and kidneys were isolated for histopathological studies.

To test the effects of LPS, 8-week-old mice (20gm body weight) were randomly divided into two groups: The control group and the LPS group were treated. In the Third phase, 3 mice per group were taken and a dose of 250 ug/kg body weight LPS was injected in 3 mice intraperitoneally of the treatment group. Body weight of both the groups was measured before LPS injection and 24 hours after the injection. Blood samples were taken from the retro orbital vein using capillary tubes to determine the BUN, SCre, and albumin levels. The mice were separately kept in cages for 24 hours. Blood was obtained 24 hours after the LPS injections, followed by kidney samples.

Blood Biochemistry

Serum samples were prepared by centrifuging clotted blood samples for 10 minutes at 3000 rpm. BUN and creatinine levels were determined using commercial assay kits (Mindray BS-230; Mindray kits) from Mindray Medical India Pvt Ltd, Gurugram, Haryana, India.

Histology

The kidney was perfused with cold PBS and soaked in 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 24 hours at 4 °C before being embedded in paraffin. Paraffin block samples were cut into 2-μm slices (three sections per mouse for each staining, 200 μm apart) and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin and PAS. An optical microscope was used to evaluate renal histological alterations. All analyses were conducted on blinded slides.

Determination of the expression of LC3b, Beclin1, ATG4, and ATG5 genes

The gene expression study of LC3b, Beclin1, ATG4, and ATG5 genes was performed in LPS treated group doses 250 ug/kg body weight, 125 ug/kg body weight and controls. Gene expression levels were studied by quantifying complementary DNA (cDNA) by qRT-PCR. Total RNA (1.5 μg) was used to generate cDNA using a thermoscientific Revert Aid First Strand cDNA synthesis kit (molecular biology). Perl Primer software synthesized the primers for LC3b, Beclin1, ATG4, and ATG5 and housekeeping gene β-actin; internal control gene). Real-time PCR was performed on CFX Opus 384 Real-Time PCR System (© 2024 Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) using KAPABIOSYSTEMS SYBER (Sigma-Aldrich, Kapa Biosystem, South Africa). RT-PCR was performed in duplicates and was repeated two times for each gene and each sample. Relative transcript quantities were calculated using the Ct method with β-actin as the endogenous reference gene.

Data and Statistical Analysis

The results are shown as means ± standard errors of the mean. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA. P-values of p < 0.05 have been considered statistically significant.

3. Results

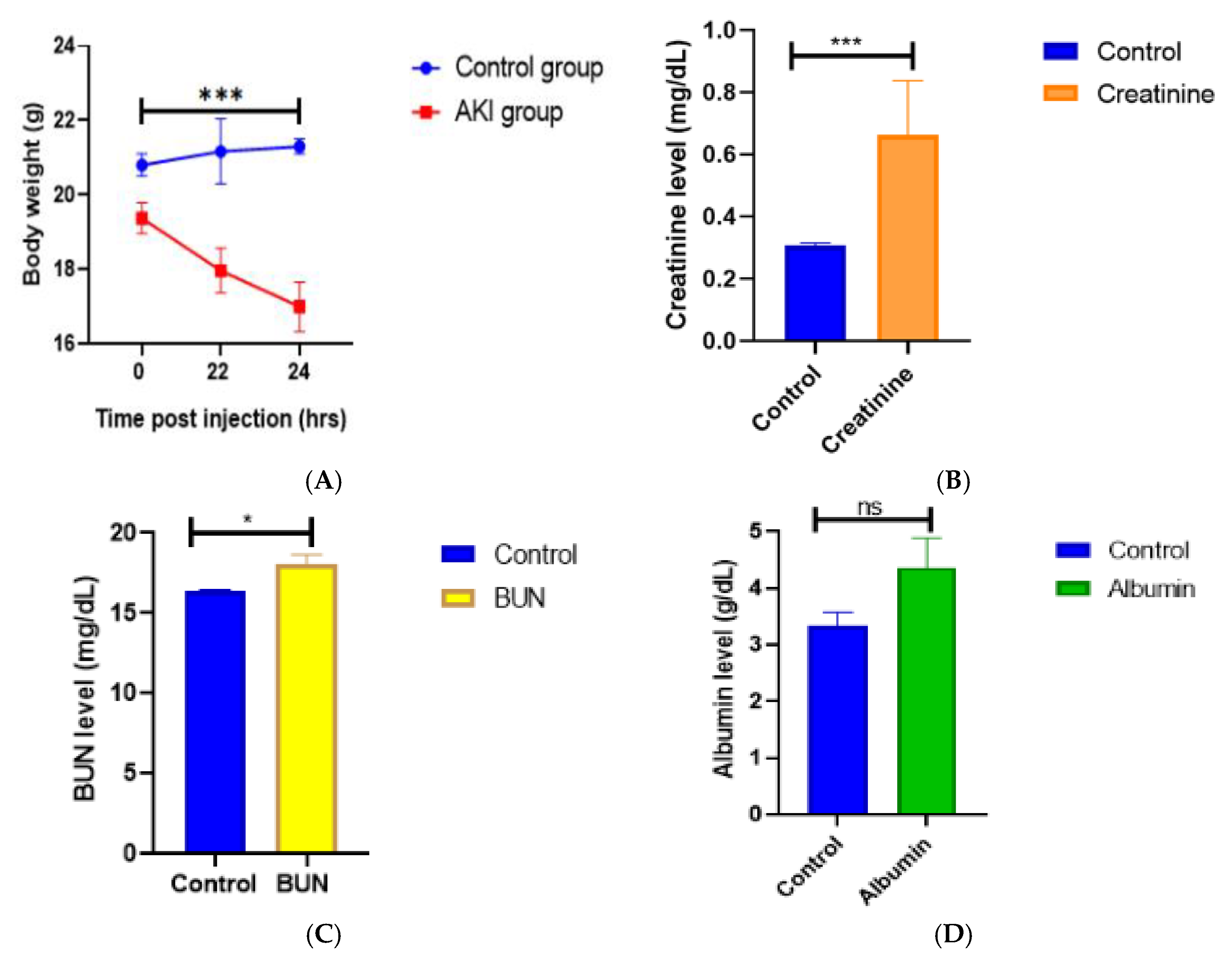

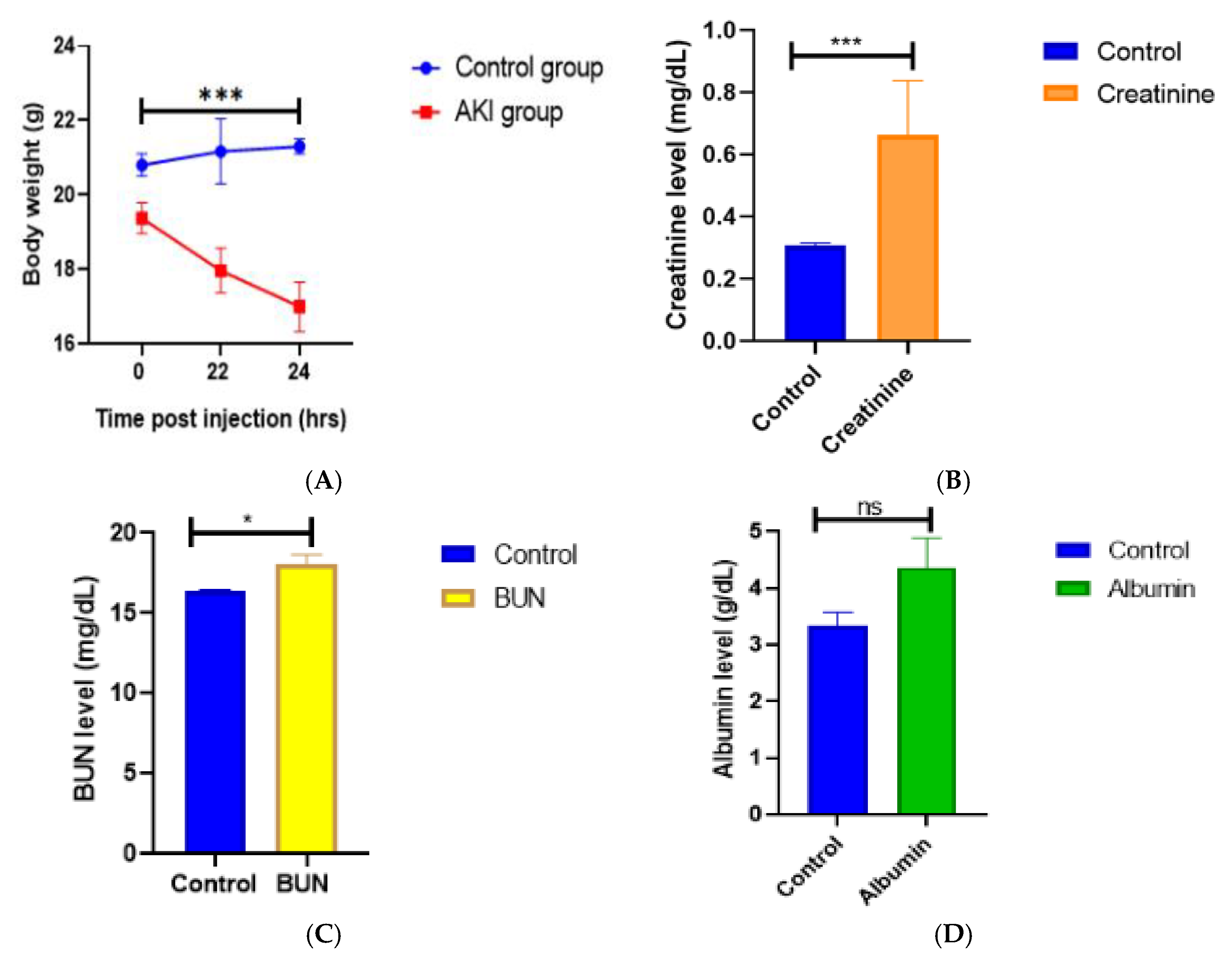

LPS-treated mice displayed the same general pattern of motor activity following infection with E. coli LPS (250 ug/kg, i.p.), as a quick activity-reducing change was noticed. Mice appeared weak and slower after receiving LPS and had decreased locomotor activity during 24 hours. Food intake also decreased in all animals 1-2 hours after LPS administration. Mice treated with 1mg/kg and 250 ug/kg LPS lost considerably more body weight than mice treated with 125 ug/kg B.W and the control group. The peak hours of weight loss were seen between the 22nd- 24th hours after LPS administration in 250ug/kg B.W mice group shown in figure A.

Figure 2.

A. Effect of 250ug/kg LPS on body weight of mice in phase 3 experiments; changes in the body weight were measured before LPS was injected i.p. and at 22nd and 24th hours after injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. ***P<0.001 vs Control group. B. Mouse Serum Creatinine levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control group. Serum Creatinine levels were measured at 24 h afters LPS injection. Data is expressed as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. ***P<0.001 vs Control group. C. Mouse BUN levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control mice. Blood Urea Nitrogen levels were measured at 24 h after LPS injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. *P<0.05 vs Control group (P=0.0246). D. Mouse Albumin levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control mice. Mouse blood Albumin levels were measured at 24 h after LPS injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. P=ns vs Control group (P=non-significant; 0.1017).

Figure 2.

A. Effect of 250ug/kg LPS on body weight of mice in phase 3 experiments; changes in the body weight were measured before LPS was injected i.p. and at 22nd and 24th hours after injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. ***P<0.001 vs Control group. B. Mouse Serum Creatinine levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control group. Serum Creatinine levels were measured at 24 h afters LPS injection. Data is expressed as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. ***P<0.001 vs Control group. C. Mouse BUN levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control mice. Blood Urea Nitrogen levels were measured at 24 h after LPS injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. *P<0.05 vs Control group (P=0.0246). D. Mouse Albumin levels; Renal function in LPS treated mice vs Control mice. Mouse blood Albumin levels were measured at 24 h after LPS injection. Data is presented as means.e.m. for n=3 mice per group. P=ns vs Control group (P=non-significant; 0.1017).

The blood biochemical results of our study to find the impact of administering LPS to cause acute kidney injury (AKI) and assessed renal function was assessed.

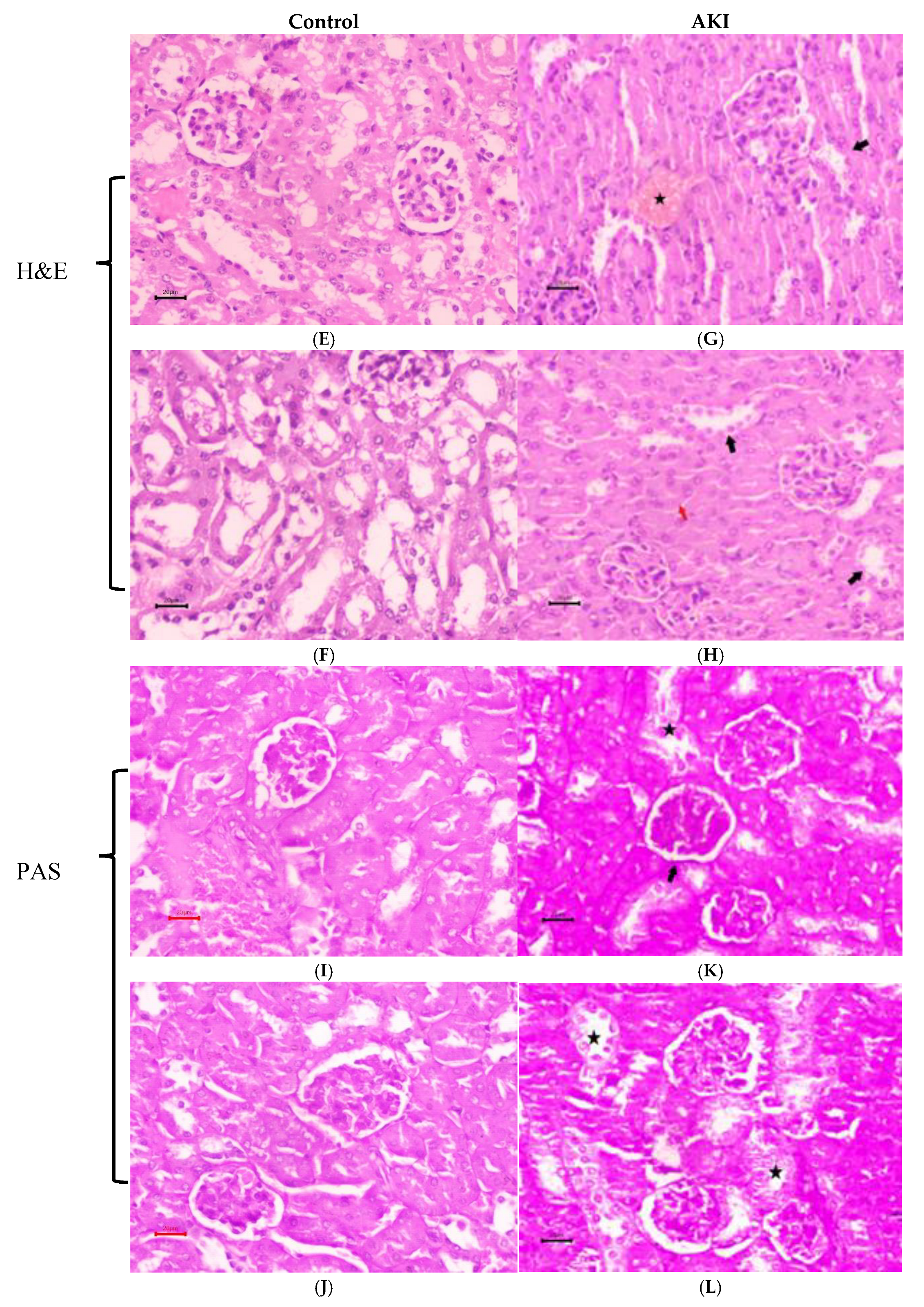

Figure 3.

E. & F. Results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), I. & J. periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) of renal tissue from control mice. G. & H. Results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), K. & L. periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) of renal tissue from LPS treated mice. Renal tubules showed epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis with tubules (Black arrow) showing complete obliteration / swelling (red arrow). Congestion of blood vessels seen (star). Renal paranchyma shows normal PAS reaction along with mild thickening of basement membrane of bowman’s capsule (arrow) and tubular degeneration (star).

Figure 3.

E. & F. Results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), I. & J. periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) of renal tissue from control mice. G. & H. Results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), K. & L. periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) of renal tissue from LPS treated mice. Renal tubules showed epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis with tubules (Black arrow) showing complete obliteration / swelling (red arrow). Congestion of blood vessels seen (star). Renal paranchyma shows normal PAS reaction along with mild thickening of basement membrane of bowman’s capsule (arrow) and tubular degeneration (star).

The second phase of the pilot investigation showed a notable and substantial increase in serum BUN (101.27 mg/dL) compared to the control group one day after exposure to 250 ug/kg of LPS. Moreover, one day after LPS, albumin levels were raised as well, but less so than BUN. On the other hand, LPS-challenged animals at the same dose in the third phase of our investigation showed a considerable reduction in blood BUN levels (Avg. 18.3 mg/dL) (Figure C.), and creatinine levels were also consistently higher while Albumin levels remained insignificant in the third phase of our trial shown in figure B, C, D.

The histological changes in the kidneys caused by LPS were assessed using H&E and PAS staining. H&E histological staining of renal tissue from mice in control figures E. and F., as well as PAS-stained sections. figures I. and J. had normal kidney morphology, with Malpighian corpuscles consisting of a tuft of capillaries (the glomerulus) surrounded by Bowman’s capsule. For control group renal paranchyma exhibits a normal PAS reaction along with right thickness of the basement membrane of the Bowman’s capsule (200nm) whilst in contrast to LPS treated group showed mild thickening of the GBM (250nm). Tubular degeneration was observed one day after LPS injection. Renal tubules showed epithelial cell degeneration and necrosis with tubules, showing complete obliteration /swelling shown in figure G. & H. Congestion of blood vessels seen in PAS staining of AKI mice as shown in figure K. & L. In this sense, the LPS group’s pathologic damage was noticeably higher than that of the control group.

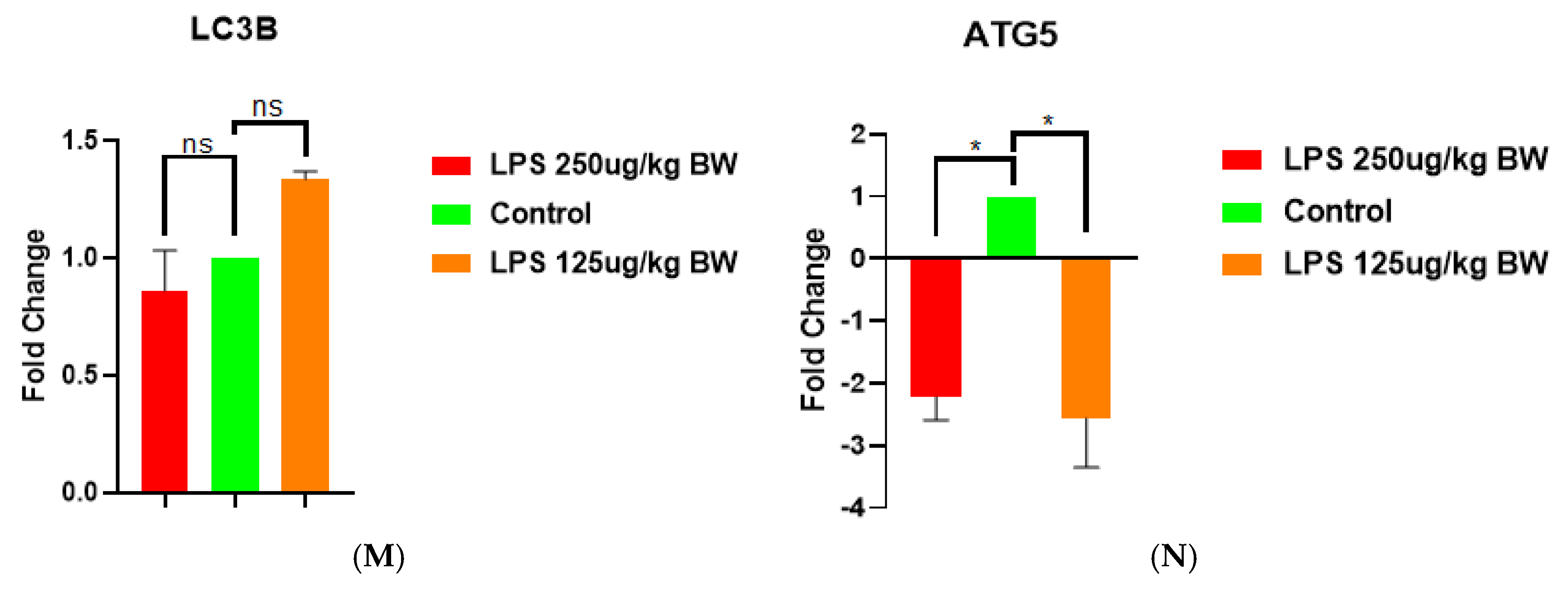

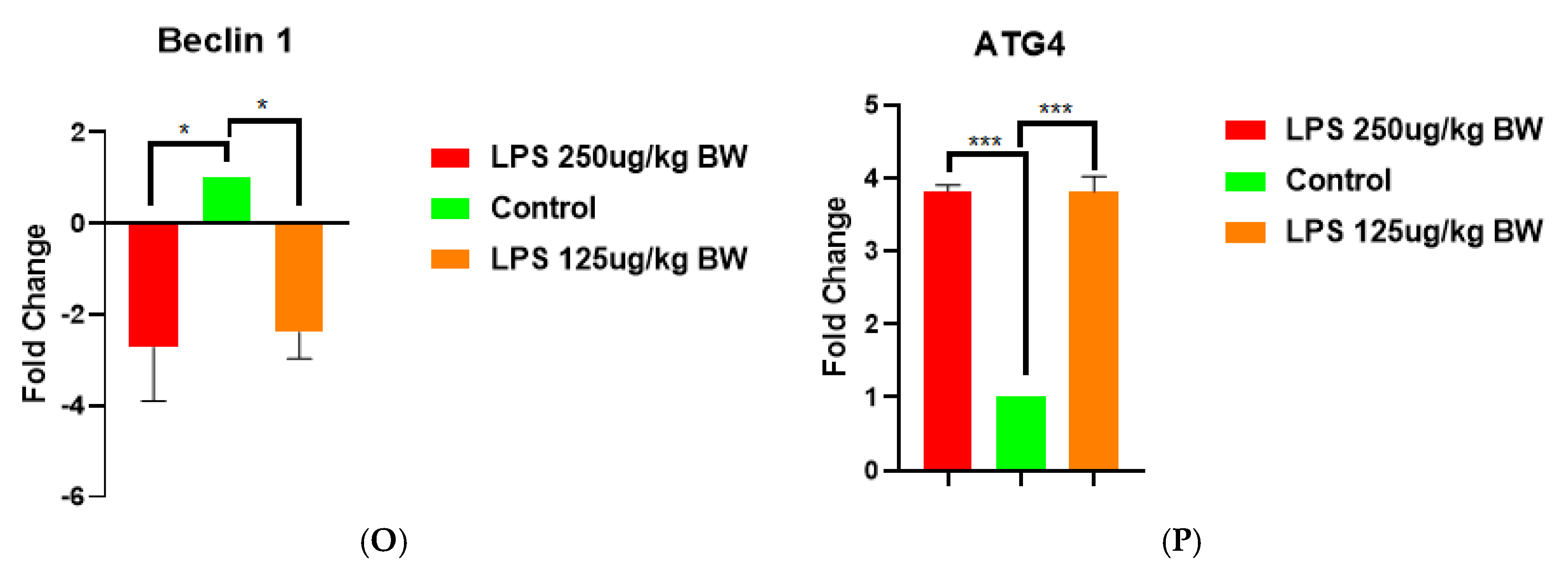

To study the effects of LPS-induced acute kidney injury (AKI) on the expression of autophagy-related genes, we examined the expression of key autophagy-related genes (LC3B, ATG5, Beclin 1, and ATG4) in kidney tissues following treatment with two doses of LPS (125 µg/kg BW and 250 µg/kg BW). Among the set of genes, the levels of LC3B expression showed no significant change across groups, suggesting that LPS exposure had no discernible effect on transcriptional levels as shown in Figure M. ATG5 and Beclin 1 were downregulated during LPS treatment, indicating an overall suppression of the autophagic initiation process during AKI as shown in figures N and O. Meanwhile, it was interesting to note the increase ATG4 expression experienced by both LPS doses, compared to controls (p < 0.001), which may demonstrate either a compensatory/protective action or dysregulation of the autophagic treatment under an inflammatory stress.

Taken together these data suggest that progressive changes in regulating autophagy are at play during LPS induced AKI, where initiation mechanisms of autophagy are suppressed (e.g., ATG5 and Beclin1) while processing components such as ATG4 are upregulated as shown in figure P. In this context, the relative imbalance of increased suppressive initiation components of the autophagic machinery compared to the processing components may contribute to the impaired autophagic flux seen throughout stages of AKI progression.

Figure 4.

M, N, O, & P. Expression profiling of major autophagy-related genes in kidney tissues after LPS-induced AKI. Bar graphs illustrate the fold change in mRNA level of expression of LC3B, ATG5, Beclin 1, and ATG4 in M, N, O, & P; respectively in LPS-treated mice at two doses (125 µg/kg BW and 250 µg/kg BW) versus the control group. ATG4 expression was notably increased in both the LPS-treated groups compared to control (***p < 0.001). ATG5 and Beclin 1 were drastically downregulated in the LPS-treated groups (*p < 0.05), while the control group was relatively higher. LC3B expression had no significant variation between groups (ns = not significant). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Figure 4.

M, N, O, & P. Expression profiling of major autophagy-related genes in kidney tissues after LPS-induced AKI. Bar graphs illustrate the fold change in mRNA level of expression of LC3B, ATG5, Beclin 1, and ATG4 in M, N, O, & P; respectively in LPS-treated mice at two doses (125 µg/kg BW and 250 µg/kg BW) versus the control group. ATG4 expression was notably increased in both the LPS-treated groups compared to control (***p < 0.001). ATG5 and Beclin 1 were drastically downregulated in the LPS-treated groups (*p < 0.05), while the control group was relatively higher. LC3B expression had no significant variation between groups (ns = not significant). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used LPS intraperitoneally to create the sepsis-induced AKI model in BALB/c mice in order to examine the dose-dependent effects of LPS on the kidney morphology and blood biochemistry of mice. Serum CRE and BUN values are traditional markers to assess kidney function in relation to metabolic features. In our study, LPS-treated mice had unusual kidney damage indicators i.e. CRE, BUN levels with more substantial pathologies in renal tissues as compared to the control group.

Sepsis associated AKI is a separate disease from all other phenotypes of AKI due to the complicated and unique pathophysiology of sepsis. It is very difficult to pinpoint the precise beginning of AKI in sepsis, which makes it challenging to respond quickly to prevent renal damage. This has hindered the development of successful treatments and reduced our comprehension of pathophysiologic processes. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) intraperitoneal injection model of sepsis in animals is likely the most researched model. LPS is the main component of the outer surface membrane that is found on practically all Gram-negative bacteria. It is a potent immune system stimulant. This methodology has inherent limitations even though it is easy to understand and apply [

11,

12,

13]. Research has revealed that BALB/c mice exhibit greater resistance to obstruction-mediated damage compared to C57BL/6 mice. Compared to the C57BL/6 strain, BALB/c mice had less severe inflammation and fibrosis as well as a greater degree of (histological) recovery of the unblocked kidney. We exclusively used male mice for our investigation (BALB/c strain), for a number of reasons. First, as compared to male mice suffering from sepsis, female mice exhibit a markedly higher survival rate. When the endotoxic shock approach is used to treat sepsis in female mice, the animals exhibit more resistance than the controls [

14,

15].

The simplest way to assess kidney injury is by histopathological changes and damage. The renal tubular showed variable degrees of cavity enlargement and degradation of epithelial cells following the introduction of LPS. Pathological indicators of renal function, BUN and SCre, have increased but are still within normal ranges. This might be because they did not alter much in the early stages of AKI, as evidenced by studies by Bilgili et al. Creatinine measurements taken repeatedly do not allow for an early diagnosis of AKI. Age, weight, and level of hydration all affect serum creatinine, which only becomes noticeable after the kidneys have lost 50% of their capacity [

16].

Figure 5.

Autophagy Mechanisms in LPS-Triggered Acute Renal Stress: Role of Key Signaling Molecules.

Figure 5.

Autophagy Mechanisms in LPS-Triggered Acute Renal Stress: Role of Key Signaling Molecules.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) impacts nearly every system in the body, yet the effects are not uniform since the kidneys are responsible for preserving homeostasis. Particularly affecting the heart and lungs, fluid retention typically manifests clinically as respiratory or circulatory failure. Additionally, fluid retention weakens the gastrointestinal tract, including the liver and the intestines, encouraging the breakdown of the intestinal barrier and the movement of bacteria and their toxins. The brain, heart, bone marrow, and immune system are all impacted by impaired excretion of uraemic toxin, which can result in neurocognitive impairments, anaemia, and acquired immunodeficiency with ongoing systemic inflammation. Debris from kidney cell necrosis is released into the venous circulation and accumulates in the lungs, where it can lead to thrombosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and direct microvascular damage [

17]. Protein metabolism results in the serum byproduct known as blood urea nitrogen (BUN). It is among the earliest heart failure prognostic biomarkers. The liver produces urea, which is then transported by blood to the kidneys for elimination. When glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines due to illness or injury to the kidneys, BUN builds up in the blood. BUN increases can be brought on by illnesses including shock, heart failure, high-protein diets, and bleeding into the gastrointestinal system [

18]. Since numerous renal and nonrenal variables that are unrelated to kidney damage or function can impact BUN and serum creatinine, they are not highly sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of AKI [

19], as same is also depicted in the blood biochemistry results of our study. Rats and mice have considerably different immune systems and anatomical features from humans, despite being the most often used animal models for AKI research. One of the reasons for the failure of potential therapies investigated and developed in these animal models to find their way into clinical practice is their heterogeneity [

20]. Given that prolonged kidney damage raises the risk of cardiovascular problems and mortality, it is imperative to prevent AKI from occurring as well as to recognise and treat it as soon as possible. There are currently no reliable preventative measures for the development of chronic kidney disease, despite advancements in contemporary medicine [

21].

In the study, the dysregulated autophagy gene expression profile seen in LPS-induced AKI downregulated initiation (ATG5, Beclin-1), invariant LC3B, and overactivated processing (ATG4 overexpression) displays a multifaceted pathophysiological response to sepsis-induced inflammation, autophagy pathway shown in

Figure 5 in detail [

34]. Our gene expression analysis in AKI reveals that pro-inflammatory signaling inhibits autophagy initiation. LPS activates the NF-κB and STAT3 signaling pathways on renal cells, resulting in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α [

27,

28]. These signals prevent autophagy initiation by downregulating Beclin-1 through NF-κB-dependent transcriptional repression. This interferes with the VPS34 complex, which is required for phagophore nucleation [

29]. Autophagosome elongation is inhibited by ATG5 reduction because LC3 lipidation requires the ATG12-ATG5 conjugation. Additionally, inflammatory stressors also activate mTOR, which is an essential inhibitor of autophagy initiation [

30]. Upregulation of ATG4 as a Maladaptive or Compensatory reaction Cysteine protease ATG4 produces pro-LC3 to LC3-I by recycling LC3-II from autophagosomal membranes. In the face of autophagic flux inhibition, attempts to sustain LC3 recycling may be unsuccessful due to the upregulation of ATG4 [

27]. ATG4 transcription is directly induced by LPS/NF-κB signaling, but other ATG genes are inhibited [

27,

31], indicating dysregulation brought on by inflammation and aberrant mitochondrial accumulation result from compromised mitophagy, which further activates ATG4 to combat ubiquitinated aggregates [

32]. LC3B remained unchanged because autophagosome-lysosome fusion is impaired, LC3B content does not change despite decreased initiation. In the presence of stopped degradation [

30,

32], LPS prevents lysosomal acidification, which leads to LC3-II accumulation (measured as unchanged total LC3B). Furthermore, LC3-II is delipidated by overactive ATG4, which prevents it from forming a membrane and reduces the number of functioning autophagosomes [

27,

31]. All of the foregoing gene expression results point to autophagic flux blockade as a consequence of imbalance. A crucial bottleneck is caused by the mismatch between processing and initiation. Reduced autophagosome formation due to decreased Beclin-1/ATG5. Autophagosome maturation failure and premature delipidation of LC3-II are caused by elevated ATG4. As a result, functional autophagic machinery is depleted, leading to oxidative stress is caused by the accumulation of damaged organelles, such as mitochondria. NLRP3 inflammasome activation 68 exacerbated inflammation and tubular cell apoptosis/necrosis [

27,

28,

31,

32]. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that LPS-induced sepsis leads to significant renal damage and impaired autophagy, as evidenced by histopathological changes, elevated kidney injury markers, and altered crucial autophagy gene expressions. Despite traditional limitations in BUN and creatinine sensitivity, early AKI pathology was effectively detected. These findings highlight the urgent need for improved diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to AKI.

References

- Ronco, Claudio et al. “Acute kidney injury.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 394,10212 (2019): 1949-1964. [CrossRef]

- Kellum, John A et al. “Acute kidney injury.” Nature reviews. Disease primers vol. 7,1 52. 15 Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- 3. Rousta, Ali-Mohammad et al. “Protective effect of sesamin in lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse model of acute kidney injury via attenuation of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis.” Immunopharmacology and immunotoxicology vol. 40,5 (2 018): 423-429. [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, Rinaldo et al. “Acute kidney injury.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 380,9843 (2012): 756-66. [CrossRef]

- Anna Zuk1, and Joseph V. Bonventre. “Acute Kidney Injury.” Annual Review of Medicine vol. 67:293-307 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Hsu, R. K., & Hsu, C. (2016). The Role of Acute Kidney Injury in Chronic Kidney Disease. Seminars in Nephrology, 36(4), 283–292. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, A. B., Sanchez-Niño, M. D., Martín-Cleary, C., Ortiz, A., & Ramos, A. M. (2013). Progress in the development of animal models of acute kidney injury and its impact on drug discovery. Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery, 8(7), 879–895. [CrossRef]

- Zarjou, Abolfazl; Agarwal, Anupam. Sepsis and Acute Kidney Injury. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 22(6):p 999-1006, June 2011. |. [CrossRef]

- Mir, Salma Mukhtar et al. “Ferulic acid protects lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury by suppressing inflammatory events and upregulating antioxidant defenses in Balb/c mice.” Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie vol. 100 (2018): 304-315. [CrossRef]

- Senouthai, S., Wang, J., Fu, D. et al. Fractalkine is Involved in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Podocyte Injury through the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in an Acute Kidney Injury Mouse Model. Inflammation 42, 1287–1300 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Zarjou, Abolfazl, and Anupam Agarwal. “Sepsis and acute kidney injury.” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN vol. 22,6 (2011): 999-1006. [CrossRef]

- Doi, Kent et al. “Animal models of sepsis and sepsis-induced kidney injury.” The Journal of clinical investigation vol. 119,10 (2009): 2868-78. [CrossRef]

- Poli-de-Figueiredo, Luiz F et al. “Experimental models of sepsis and their clinical relevance.” Shock (Augusta, Ga.) vol. 30 Suppl 1 (2008): 53-9. [CrossRef]

- Rabe, Michael, and Franz Schaefer. “Non-Transgenic Mouse Models of Kidney Disease.” Nephron vol. 133,1 (2016): 53-61. [CrossRef]

- Arifin, Arifin et al. “Improvement of renal functions in mice with septic acute kidney injury using secretome of mesenchymal stem cells.” Saudi journal of biological sciences vol. 31,3 (2024): 103931. [CrossRef]

- Scheel, Paul J et al. “Uremic lung: new insights into a forgotten condition.” Kidney international vol. 74,7 (2008): 849-51. [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, Beliz et al. “Sepsis and Acute Kidney Injury.” Turkish journal of anaesthesiology and reanimation vol. 42,6 (2014): 294-301. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xue, L.B. Daniels, A.S. Maisel, Navaid Iqbal, Cardiac Biomarkers, Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences, Elsevier, (2014), ISBN 9780128012383, doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.00022-2.

- Edelstein, Charles L. “Biomarkers of acute kidney injury.” Advances in chronic kidney disease vol. 15,3 (2008): 222-34. [CrossRef]

- Packialakshmi, Balamurugan et al. “Large animal models for translational research in acute kidney injury.” Renal failure vol. 42,1 (2020): 1042-1058. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Hyun Goo et al. “A Review of Natural Products for Prevention of Acute Kidney Injury.” Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) vol. 57,11 1266. 18 Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y., Fu, Y., Wu, W., Tang, C., & Dong, Z. (2023). Autophagy in acute kidney injury and maladaptive kidney repair. Burns & trauma, 11, tkac059. [CrossRef]

- He, L., Livingston, M. J., & Dong, Z. (2014). Autophagy in acute kidney injury and repair. Nephron. Clinical practice, 127(1-4), 56–60. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, G. P., & Shah, S. V. (2016). Autophagy in acute kidney injury. Kidney international, 89(4), 779–791. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A., Bourdenx, M., Fujimaki, M., Karabiyik, C., Krause, G. J., Lopez, A., Martín-Segura, A., Puri, C., Scrivo, A., Skidmore, J., Son, S. M., Stamatakou, E., Wrobel, L., Zhu, Y., Cuervo, A. M., & Rubinsztein, D. C. (2022). The different autophagy degradation pathways and neurodegeneration. Neuron, 110(6), 935–966. [CrossRef]

- Axe, Elizabeth L., et al. “Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum.” The Journal of cell biology 182.4 (2008): 685-701.

- Gong, L., Pan, Q., & Yang, N. (2020). Autophagy and Inflammation Regulation in Acute Kidney Injury. Frontiers in physiology, 11, 576463. [CrossRef]

- Lee, SH., Kim, K.H., Lee, S.M. et al. STAT3 blockade ameliorates LPS-induced kidney injury through macrophage-driven inflammation. Cell Commun Signal 22, 476 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Zhang, Y., Wang, L., Diao, Z., Liu, W. (2015). The Role of Autophagy in Kidney Inflammatory Injury via the NF-κB Route Induced by LPS. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 12(8), 655-667. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Feng X, Li B, Sha J, Wang C, Yang T, Cui H and Fan H (2020) Dexmedetomidine Protects Against Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Enhancing Autophagy Through Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 11:128. [CrossRef]

- Han, J., Wu, J., Liu, H., Huang, Y., Ju, W., Xing, Y., Zhang, X. & Yang, J. (2023). Inhibition of pyroptosis and apoptosis by capsaicin protects against LPS-induced acute kidney injury through TRPV1/UCP2 axis in vitro . Open Life Sciences, 18(1), 20220647. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L., Cai, J., Li, C. et al. 4-Octyl itaconate attenuates LPS-induced acute kidney injury by activating Nrf2 and inhibiting STAT3 signaling. Mol Med 29, 58 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wu, W., Lan, W., Jiao, X. et al. Pyroptosis in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Crit Care 29, 168 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee R, Vidic J, Auger S, Wen H-C, Pandey RP, Chang C-M. Exploring Disease Management and Control through Pathogen Diagnostics and One Health Initiative: A Concise Review. Antibiotics. 2024; 13(1):17.

- Tripathi S, Khatri P, Fatima Z, Pandey RP, Hameed S. A Landscape of CRISPR/Cas Technique for Emerging Viral Disease Diagnostics and Therapeutics: Progress and Prospects. Pathogens. 2023; 12(1):56.

- Pandey RP, Mukherjee R, Chang CM. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance system mapping in different countries. Drug Target Insights. 2022 Nov 30;16:36-48. 35. Jia, H., Yan, Y., Liang, Z., Tandra, N., Zhang, B., Wang, J., Xu, W., & Qian, H. (2018). Autophagy: A new treatment strategy for MSC-based therapy in acute kidney injury (Review). Molecular medicine reports, 17(3), 3439–3447.

- Pandey RP,Nascimento MS,Franco CH, Bortoluci K, Silva MN, Zingales B, Gibaldi D, Castaño Barrios L, Lannes-Vieira J, Cariste LM, Vasconcelos JR,Moraes CB, Freitas-Junior LH, Kalil J,Alcântara L, Cunha-Neto E, 2022. Drug Repurposing in Chagas Disease: Chloroquine Potentiates Benznidazole Activity against Trypanosoma cruzi In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e00284-22.

- Ahmad S, Alrouji M, Alhajlah S, Alomeir O, Pandey RP, Ashraf MS, Ahmad S, Khan S. Secondary Metabolite Profiling, Antioxidant, Antidiabetic and Neuroprotective Activity of Cestrum nocturnum (Night Scented-Jasmine): Use of In Vitro and In Silico Approach in Determining the Potential Bioactive Compound. Plants. 2023; 12(6):1206.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).