1. Introduction

Sepsis, characterized by a dysregulated host response to infection leading to life-threatening organ dysfunction, is defined as a clinical syndrome with a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score≥2 [

1]. During the early phase of sepsis, the kidneys are often the first organs injured, resulting in decreased urine output and acute renal dysfunction, which are common characteristics of acute kidney injury (AKI). This form of acute kidney injury occurring in sepsis is referred to as sepsis-associated acute kidney injury (SAKI) [

2]. Retrospective analysis of clinical data shows that approximately 47.1% of sepsis patients experience AKI [

3]. In contrast to patients with other types of AKI, those with SAKI exhibit longer length of hospital stay and higher mortality rate [

4]. Currently, the pathogenesis of SAKI remains unclear, with its pathological process being highly complex and clinical treatment options limited. This has rendered SAKI a significant medical problem threatening human life and health.

An iron-dependent mode of programmed cell death, ferroptosis features the abnormal overaccumulation of intracellular ferrous ions, excessive production of lipid peroxides, and dysfunction of the amino acid-based antioxidant system [

5]. Studies have shown that in animal models of SAKI, significantly increased mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) induce ferroptosis in renal parenchymal cells, while the ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 effectively alleviates tissue injury in these animals [

6]. Knockdown of Nuclear Factor, Interleukin 3 Regulated (NFIL3) exerts protective effects by downregulating ACSL4 expression, thereby alleviating ferroptosis and inflammatory responses in renal tubular epithelial cells [

7]. Another study showed that melatonin alleviates SAKI by activating Nrf2-dependent HO-1 expression, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis of SAKI [

8]. Conversely, by suppressing GPX4 expression in renal tubular epithelial cells, PGE2 induces ferroptosis, thereby further exacerbating renal injury [

9]. In summary, these findings establish ferroptosis as a critical driver in the sepsis-induced renal deterioration. Although the specific mechanisms by which ferroptosis contributes to SAKI pathology remain incompletely understood, targeting the ferroptosis pathway is considered an effective strategy for alleviating SAKI and thus provides potential therapeutic targets for this condition.

Hepcidin is primarily synthesized in the liver and serves as an essential hormone regulating systemic iron homeostasis. It governs iron uptake and systemic distribution by binding to the iron exporter ferroportin (FPN) expressed on duodenal enterocytes and macrophages [

10]. Studies have shown that hepcidin inhibits the ferroptosis process in septic acute lung injury by upregulating the expression of ferritin heavy chain (FTH) [

11]. In lupus nephritis, hepcidin similarly alleviates renal tissue iron accumulation and inflammatory responses by promoting FTH expression [

12]. In addition, in sepsis animal models, knockout of the hepcidin gene was found to lead to impaired phagocytic clearance capacity of neutrophils and macrophages against bacteria in septic mice, accompanied by a significant increase in blood bacterial load [

13]. Previous studies have also found that hepcidin itself possesses direct antibacterial activity [

14]. These studies demonstrate that modulation of hepcidin signaling may confer therapeutic benefits in SAKI. Nrf2, a critical nuclear antioxidant transcription factor, mediates its antioxidant effect by interacting with antioxidant response elements (ARE), a process that modulates the expression of antioxidant proteins and downstream signaling molecules [

15]. Additionally, Gabapentin, isoorientin, and CBX7 all alleviate AKI by activating the Nrf2 pathway to inhibit oxidative stress [

16,

17,

18]. Through establishing in vivo cellular systems and ex vivo sepsis models, we deciphered the effects of hepcidin on SA-AKI and delineated its Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathways in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animal

All male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were acquired from the Laboratory Animal Center of Ningbo University, China. The experimental animals were kept in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) facility that sustains stable conditions at 22 ± 1°C with a 12-h light/dark cycle and were provided with autoclaved acidified water and irradiated pellets. This study was conducted in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the study gained approval for all animal procedures.

The CLP method was applied to generate the murine model of SAKI [

19]. Briefly, under isoflurane anesthesia, mice were subjected to a midline laparotomy to facilitate cecal exposure. Next, we circumferentially ligated the cecum at the midpoint between the cecal tip and the ileocecal valve using a 4-0 silk suture, created 1 microperforations with a 22G needle, and extruded a small amount of feces (approximately 1 mm) into the peritoneal cavity before abdominal closure. For fluid resuscitation, we subcutaneously injected mice with warm (37°C) saline and guaranteed continuous availability of food and water after recovery from anesthesia. Postoperative analgesia was provided as needed. Finally, we collected serum and renal tissues at 24 h post-CLP induction for further analysis. Hepcidin administration followed a published protocol that mice receiving an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 5 mg/kg hepcidin 24 hours prior to CLP [

20]. Animals were randomized into five groups: Sham group (laparotomy without cecal ligation or puncture); Hamp group (sham operation + IP injection of hepcidin at the same volume as the treatment group); CLP group (cecal ligation and puncture alone); CLP + Hamp group (pretreatment with 5 mg/kg hepcidin 24 hours before CLP); CLP + Hamp + ML385 group (pretreatment with 5 mg/kg hepcidin 24 hours before CLP, followed by IP injection of 30 mg/kg ML385 2 hours prior to CLP to inhibit Nrf2 activity). Exogenous hepcidin was synthesized by the Chinese pharmaceutical company QYAOBIO, and ML385(HY-100523) was purchased from MCE.

2.2. Cell Lines

HK-2 cells were professionally procured from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Cell Bank, a certified cell repository. HK-2 cells were maintained under standard conditions: DMEM/F12 complete medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (C04001-500, Biological Industries, Israel) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. For a 24-h treatment period, HK-2 cells were exposed to LPS (L2630, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) at 10 μg/mL, a condition determined by preliminary experimental results. Hepcidin (10 μg/mL) administered 24 hours prior to LPS exposure attenuates inflammatory responses in HK-2 cells, based on preliminary experimental data.

2.3. Cell Viability

The CCK-8 kit (K1018, APExBIO, the USA) was utilized for the detection of cell viability. Approximately 4×103 cells were seeded into individual wells of 96-well plates and allowed to adhere before treatment according to the experimental groups. After adding the prepared CCK-8 working solution, we shielded the cells from light and incubated them at 37°C for 1 hour to prevent photodegradation of the reagents, after which we used a multimode microplate reader (Spectra Max iD3) to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

2.4. ELISA Assay

Serum concentrations of the cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL), and Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1) were quantified by ELISA with specific kits for each analyte: TNF-α (EK282, MULTI SCIENCES, China), IL-1β (E-EL-M0037, Elabscience, China), NGAL (E-EL-M0828, Elabscience, China), KIM-1 (E-EL-M3039, Elabscience, China), and IL-6 (EK206, MULTI SCIENCES, China). Additionally, levels of TNF-α (RK0030, ABclonal, China) and IL-6 (EK106, MULTI SCIENCES, China) in cell culture supernatants were determined using the similar protocol as for serum samples. Detailed experimental procedures followed the manufacturers’ instructions provided with each kit.

2.5. Biochemical Analysis

In order to evaluate renal function, respective test kits were used to determine serum creatinine (C011-2-1) and BUN (C013-2-1) levels, both purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Institute, China.

2.6. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) Content in Renal Tissue

We measured Fe2+ levels in renal tissues of each group with the aid of a ferrous iron analysis kit (BC5415, Solarbio, China). Approximately 100 mg of renal tissue was homogenized at -10℃ with the extraction buffer provided in the kit. When the homogenate was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10,000 g in a pre-chilled centrifuge, we carefully collected the supernatant to avoid contamination for downstream analysis. After color development using the kit’s reagents, we used a multimode microplate reader (Spectra Max iD3) to measure sample absorbance at 593 nm.

2.7. GSH-Px Activity Assay

GSH-Px activity in renal tissues was assayed by virtue of a colorimetric kit (BC1195, Solarbio, China) that relies on the reduction of 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB). A 20–30 mg aliquot of renal tissue was weighed and subjected to cryogenic grinding using a cryogenic grinder. The renal homogenate was centrifuged to harvest the supernatant, after which GSH-Px activity was assayed by adding the kit’s reaction reagents and measuring absorbance at 412 nm.

2.8. Detection of Lipid Peroxidation Product MDA and GSSH/GSSG Ratio

Levels of MDA, GSH, and GSSG in renal tissues were quantified with commercially purchased assay kits (Solarbio, China), each containing pre-calibrated reagents for MDA (BC002), GSH (BC1175), and GSSG (BC1185).

2.9. Lipid ROS assay

After treatment according to the experimental protocol, we employed a DCFH-DA probe (2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, G1706, Servicebio, China) to measure intracellular ROS levels in HK-2 cells, quantifying fluorescence intensity on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer. Primarily, following medium removal and two PBS washes, cells were incubated with DCFH-DA working solution (1:1000 dilution in basal medium) at 37°C in the dark for 30 minutes. After washing and detaching the cells, we collected them by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 5 min, and then analyzed them by flow cytometry. Fluorescence intensity was measured to quantify ROS levels in each group.

2.10. Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

Following fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h, gradient ethanol dehydrated the renal tissues, xylene cleared them, and paraffin embedded them. Paraffin sections (5 μm thick) were stained with H&E, mounted using neutral gum, and examined under a 200× optical microscope to assess histological changes. Clear blue-stained cell nuclei and pink cytoplasmic structures were visualized. Tubular injury was defined as: swelling of renal tubular epithelial cells, loss of brush border, vacuolar degeneration, tubular dilation, necrosis, cast formation, and desquamation. The degree of tubular injury was evaluated using a semi-quantitative pathological scoring system [

21]. Score 0: normal renal tissue; Score 1: <25% tubular injury; Score 2: 25%–50% tubular injury; Score 3: 50%–75% tubular injury; Score 4: 75%–100% tubular injury.

2.11. Immunohistochemistry

Mice renal tissues were immobilized via immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde buffered with PBS, processed into paraffin sections. First, after deparaffinizing and rehydrating the tissue sections, we incubated them overnight at 4℃ with a 1:1000 dilution of anti-Nrf2 primary antibody (GB113808, Servicebio, China). Then we incubated the sections with a corresponding secondary antibody at room temperature for 50 minutes. We used ImageJ (NIH Co., USA) to measure the integrated optical density (IOD) values as an indicator of Nrf2 expression level.

2.12. Western-Blotting

Freshly isolated kidney specimens were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors, homogenized on ice, centrifuged at 12,000 g, and normalized for protein concentration. The samples were denatured by boiling at 100°C. SDS-PAGE separated equal amounts of renal tissue protein and subsequently transferred to PVDF membranes. Prior to incubation with blocking buffer for 0.5 hour, the PVDF membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse antibody against GPX4 (1:2,000, 67763-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), a rabbit antibody against ACSL4 (1:10,000, 22401-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), a rabbit antibody against Nrf2 (1:1,000, A0674, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), a rabbit antibody against Lamin B1 (1:10,000, 12987-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and a mouse antibody against GAPDH (1:50,000, 60004-1-Ig, Proteintech, Wuhan, China). After washing the membranes three times with TBST, we incubated the PVDF membranes with Goat anti-rabbit (1:5,000, SA00001-2, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) or Goat anti-mouse (1:5,000, SA00001-1, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) IgG-HRP conjugates for 1 hour. Chemiluminescent detection was performed using a Bio-Rad imaging system (USA). Nuclear Protein Kit (PC204, Yazyme, China) separated Nrf2 nuclear protein from cytoplasmic fractions of renal tissues.

2.13. Apoptosis Rates

Apoptotic rates of HK-2 cells were identified and quantified by Annexin V-APC/PI double staining using the Apoptosis Detection Kit (AT107, MultiSciences, China) and analyzed with the BD FACSVia flow cytometer. HK-2 cells, including those in the culture supernatant, were pelleted by spinning at 1200 revolutions per minute for 5 minutes, suspended in 1×Binding Buffer, double-stained with Annexin V-APC and PI. HK-2 cells were stained with Annexin V-APC and PI for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. The total apoptosis rate indicates that Hepcidin modulates LPS-dependent cell death.

2.14. RT-qPCR

Total RNA extraction from mouse kidney tissues and HK-2 cells was carried out with an RNA Extraction Kit (RN001, Yishen Biotechnology, China), followed by concentration assessment via NanoDrop spectrophotometry. cDNA was generated in 20 μL reaction systems using a Kit (RR036A, TaKaRa, Japan) via reverse transcription, and target genes were amplified by qPCR using a Master Mix Kit (A6001, Promega, USA). Transcript levels were quantified using the cycle threshold (CT) method, and relative mRNA expression levels were derived by applying the 2-ΔΔCT method. All primer sequences were sourced from PrimerBank (

https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/).

Table 1.

RT-qPCR Primer.

| Primer |

sequences 5′-3′ |

PrimerBank ID |

NGAL For

NGAL Rev |

GAAGTGTGACTACTGGATCAGG

ACCACTCGGACGAGGTAACT |

108936956c3

|

GAPDH For

GAPDH Rev |

GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT

GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG |

378404907c1 |

Nrf2 For

Nrf2 Rev |

CTGAACTCCTGGACGGGACTA

CGGTGGGTCTCCGTAAATGG |

76573877c3 |

GPX4 For

GPX4 Rev |

TGTGCATCCCGCGATGATT

CCCTGTACTTATCCAGGCAGA |

90903234c1 |

GAPDH For

GAPDH Rev |

AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG

GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA |

126012538c1 |

2.15. Survival Analysis

After 15 mice in each group were subjected to distinct interventions as per the predefined experimental groups, survival rates were observed over a 72-hour timeframe.

2.16. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA was employed to assess overall differences, with Tukey’s tests as post hoc analyses to determine pairwise differences. Survival outcomes of mice were compared between different groups using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Statistical analyses were conducted with the aid of GraphPad Prism version 9.5 software. In this study, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

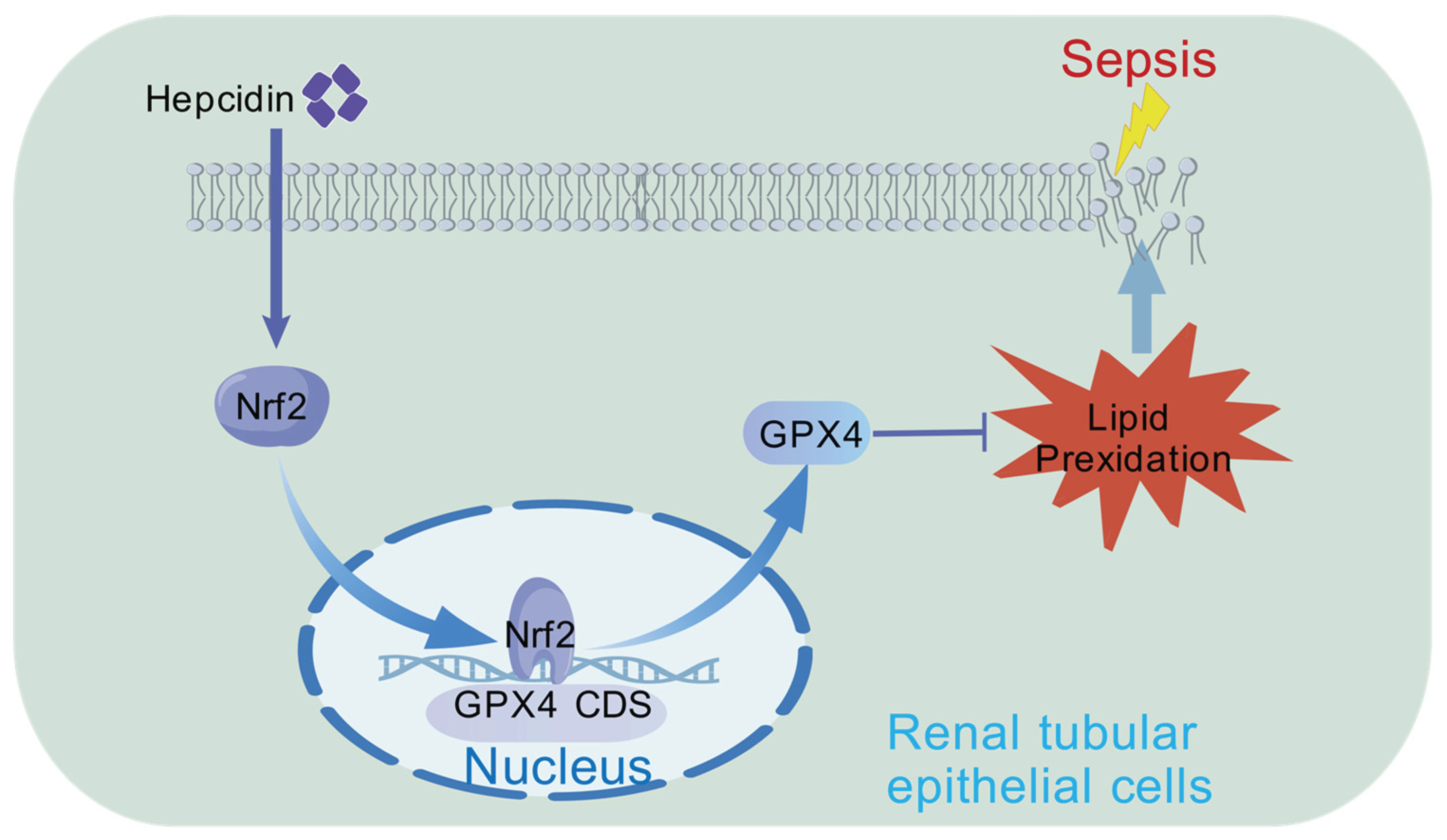

4. Discussion

Immunomodulation, antimicrobial therapy, and inhibition of oxidative stress have become research priorities in the field of SAKI treatment [

22,

23,

24]. In this study, we confirmed ferroptosis in SAKI mice and demonstrated that hepcidin treatment inhibits renal ferroptosis in SAKI mice. The underlying mechanism may involve Nrf2 activation, which upregulates the expression of downstream ferroptosis-regulating protein GPX4, thereby reducing lipid peroxidation and alleviating SAKI.

Hepcidin is believed to exert anti-infective effects by regulating systemic iron metabolism homeostasis, including reducing serum free iron levels to limit bacterial growth and maintaining iron reserves in macrophages to enhance phagocytic capacity, thereby alleviating the pathological process of sepsis [

14]. Our findings similarly demonstrate that hepcidin alleviates inflammatory responses in both septic mice and LPS-induced HK-2 cells, thereby exerting a protective effect against acute kidney injury. This beneficial action stems from hepcidin’s capacity to suppress the excessive production of IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated HK-2 cells, alongside its ability to inhibit the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) /p53 signaling pathway ultimately resulting in a decreased apoptosis rate in HK-2 cells [

25,

26]. This is consistent with our observation that hepcidin treatment reduces LPS-induced apoptosis in HK-2 cells. Based on these results, we found that hepcidin besides improved renal histopatholog-ical manifestations and alleviated tubular injury, also significantly reduced mortality in SAKI mice, indicating that hepcidin holds great potential for ameliorating SAKI.

Previous studies have shown that during sepsis, the uptake of endotoxins by renal tubular epithelial cells induces oxidative stress injury [

27]. The underlying mechanism may involve the activation of NOX4 (NADPH Oxidase 4) in SAKI, which promotes reactive ROS production and subsequent renal dysfunction [

28]. This finding explains why LPS stimulation results in increased ROS production in HK-2 cells, as observed in our flow cytometry experiments, whereas hepcidin suppresses ROS accumulation, thus mitigating cellular oxidative damage. Further investigations have demonstrated that inhibiting renal ferroptosis effectively alleviates SAKI [

29]. Given that ferrous iron overload is a critical step in ferroptosis [

5], our data demonstrate that hepcidin suppresses the Fe

2+-driven Fenton reaction triggered by iron overload in SAKI, which in turn inhibits the subsequent elevation of MDA. Hepcidin intervention significantly reduced both ferrous iron accumulation and MDA production. Accumulating evidence indicates that ROS and lipid peroxides GSH, increase GSSG, decrease the GSH/GSSG ratio, and reduce GSH-Px activity, leading to redox imbalance and ferroptosis [

30]. In line with previous observations, our experimental data have shown that SAKI mice exhibited reduced renal GSH, increased GSSG, a decreased GSH/GSSG ratio, and diminished GSH-Px activity, all of which were reversed by hepcidin treatment. Earlier studies have also demonstrated that ACSL4 promotes lipid peroxide formation, whereas GPX4 degrades lipid peroxides using oxidized GSH, and inhibiting ACSL4 or overexpressing GPX4 suppresses ferroptosis [

31,

32]. Western-blotting analysis in our study revealed that hepcidin pronouncedly downregulated ACSL4 expression and upregulated GPX4 expression in the kidneys of SAKI mice, suggesting that hepcidin inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates renal injury by modulating key ferroptosis-related proteins.

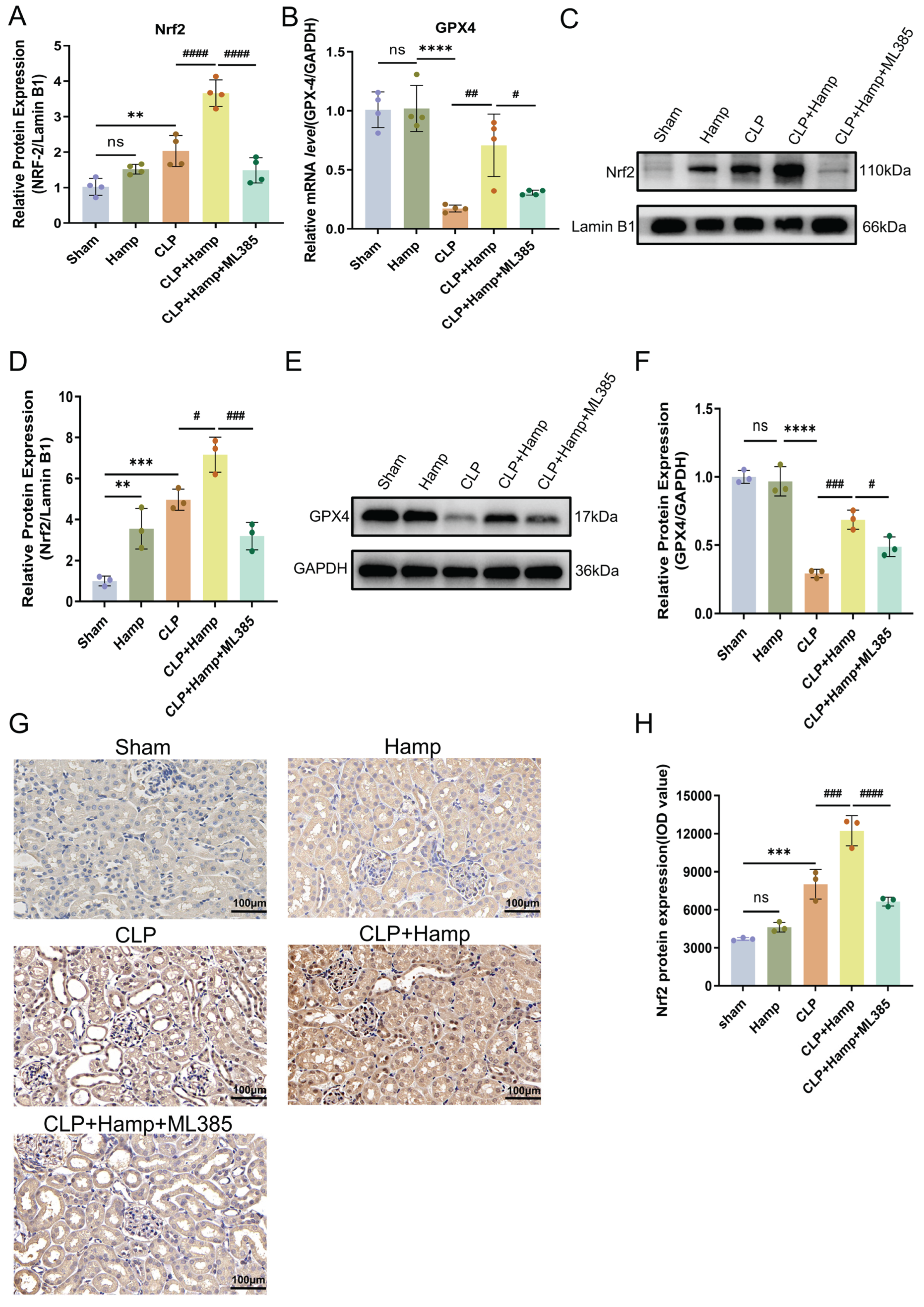

Under oxidative stress, Nrf2, functioning as a pivotal antioxidant transcription factor, dissociates from the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) repressor complex and exerts antioxidant effects [

33]. Further studies have shown that Nrf2 transcriptionally activates downstream GPX4 and HO-1, two key antioxidant enzymes, to counteract oxidative stress [

34,

35]. Given the critical role of Nrf2 in maintaining redox homeostasis, we confirmed the effects of hepcidin on Nrf2 in SAKI through Western-blotting and RT-qPCR, and further validated these findings using immunohistochemistry. Through IHC analysis and Western-blotting validation, the experimental findings provided robust evidence that hepcidin potently enhanced the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 in renal tubular epithelial cells. This finding aligns with pre-studies showing that Nrf2 activation upregulates downstream antioxidant proteins, thereby mitigating SAKI animal models [

13,

36]. GPX4, an essential mediator of ferroptosis, catalyzes the conversion of GSH to GSSG, scavenges lipid peroxides, and thus inhibits cellular ferroptosis [

37]. Previous studies have validated that targeting the Nrf2/GPX4 axis effectively mitigates renal dysfunction in sepsis, a finding that supports our conclusion [

38,

39,

40]. Our results showed that hepcidin significantly increased GPX4 expression in renal tissues of SAKI mice. To further determine whether hepcidin acts through the Nrf2/GPX4 axis, we used the specific Nrf2 inhibitor ML385 to block its activity and found that GPX4 expression was subsequently decreased, suggesting that the regulation of GPX4 by hepcidin is dependent on Nrf2 activation. In summary, hepcidin enhances nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of Nrf2, thereby upregulating downstream GPX4 expression to inhibit ferroptosis and alleviate SAKI.

Figure 1.

Hepcidin ameliorates SAKI in mice. (A) Survival rates of mice in each group over 72 hours(n=15 mice per group); (B) SCr level and (C) BUN level in different groups(n=5 mice per group); (D) Serum IL-6 concentration, (E) serum IL-1β concentration, and (F) serum TNF-α concentration measured by ELISA(n=5 mice per group); Serum kidney injury markers of NGAL(G) and KIM-1(H) quantified by ELISA(n=5 mice per group); (I) Semi-quantitative pathological scores of tubular injury(n=4 mice per group); (J) Histopathological damage in kidney tissues of mice in each group under 200× light microscopy and with local magnification. Scale bar: 150 μm and 600 μm. Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 1.

Hepcidin ameliorates SAKI in mice. (A) Survival rates of mice in each group over 72 hours(n=15 mice per group); (B) SCr level and (C) BUN level in different groups(n=5 mice per group); (D) Serum IL-6 concentration, (E) serum IL-1β concentration, and (F) serum TNF-α concentration measured by ELISA(n=5 mice per group); Serum kidney injury markers of NGAL(G) and KIM-1(H) quantified by ELISA(n=5 mice per group); (I) Semi-quantitative pathological scores of tubular injury(n=4 mice per group); (J) Histopathological damage in kidney tissues of mice in each group under 200× light microscopy and with local magnification. Scale bar: 150 μm and 600 μm. Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 2.

Hepcidin inhibits ferroptosis in SAKI mice. (A) The content of ferrous iron in renal tissues(n=5 mice per group); (B) Renal tissue MDA levels in different animal groups(n=5 mice per group); (C) GSH content in renal tissues of different animal groups(n=5 mice per group); (D) GSH/GSSG ratio; (E) GSH-Px activity(n=5 mice per group); (F) Ferroptosis-dependent protein expression changes in mice; Relative expression levels of ACSL4 (G) and GPX4 (H) in renal tissue, n=3 mice per group; Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 2.

Hepcidin inhibits ferroptosis in SAKI mice. (A) The content of ferrous iron in renal tissues(n=5 mice per group); (B) Renal tissue MDA levels in different animal groups(n=5 mice per group); (C) GSH content in renal tissues of different animal groups(n=5 mice per group); (D) GSH/GSSG ratio; (E) GSH-Px activity(n=5 mice per group); (F) Ferroptosis-dependent protein expression changes in mice; Relative expression levels of ACSL4 (G) and GPX4 (H) in renal tissue, n=3 mice per group; Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 3.

Hepcidin alleviates LPS-induced ROS accumulation and cell injury in HK-2 cells. (A) HK-2 cell viability(n=4 per group); TNF-α (B) and IL-6 (C) levels in HK-2 cell supernatants by ELISA(n=4 or 5 per group); (D) RT-qPCR analysis of NGAL mRNA expression in HK-2 cells(n=4 per group); (E) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of apoptosis in HK-2 cells after LPS treatment(n=5 per group); (F) Flow cytometric analysis of relative fluorescence intensity of ROS(n=3 per group); Compared with the control group, ns, no significant difference; ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the LPS group, ##p < 0.01, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 3.

Hepcidin alleviates LPS-induced ROS accumulation and cell injury in HK-2 cells. (A) HK-2 cell viability(n=4 per group); TNF-α (B) and IL-6 (C) levels in HK-2 cell supernatants by ELISA(n=4 or 5 per group); (D) RT-qPCR analysis of NGAL mRNA expression in HK-2 cells(n=4 per group); (E) Flow cytometry analysis and quantification of apoptosis in HK-2 cells after LPS treatment(n=5 per group); (F) Flow cytometric analysis of relative fluorescence intensity of ROS(n=3 per group); Compared with the control group, ns, no significant difference; ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the LPS group, ##p < 0.01, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 4.

Hepcidin inhibits ferroptosis in SAKI via activation of Nrf2. The relative expression level of Nrf2 mRNA (A) and GPX4 mRNA (B) in renal tissue(n=4 mice per group); (C) Nrf2 nuclear protein bands in renal tissue by WB; (D) Relative levels of Nrf2 nucleoprotein by WB densitometry (Lamin B1) in renal tissue nuclear fractions(n=3 mice per group); (E) GPX4 protein bands in renal tissue by WB; (F) Relative GPX4 protein levels by Western blot (GAPDH) in renal tissue lysates(n=3 mice per group); (G) Nrf2 protein expression by IHC; (H) Quantitative analysis of Nrf2 protein IOD values by IHC(n=3 mice per group); Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP+Hamp group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 4.

Hepcidin inhibits ferroptosis in SAKI via activation of Nrf2. The relative expression level of Nrf2 mRNA (A) and GPX4 mRNA (B) in renal tissue(n=4 mice per group); (C) Nrf2 nuclear protein bands in renal tissue by WB; (D) Relative levels of Nrf2 nucleoprotein by WB densitometry (Lamin B1) in renal tissue nuclear fractions(n=3 mice per group); (E) GPX4 protein bands in renal tissue by WB; (F) Relative GPX4 protein levels by Western blot (GAPDH) in renal tissue lysates(n=3 mice per group); (G) Nrf2 protein expression by IHC; (H) Quantitative analysis of Nrf2 protein IOD values by IHC(n=3 mice per group); Compared with the sham group, ns, no significant difference; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Compared with the CLP+Hamp group, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001, ####p < 0.0001. Hamp, hepcidin.

Figure 5.

Hepcidin treatment may alleviate sepsis-associated acute kidney injury through activating the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway to suppress ferroptosis in SAKI.

Figure 5.

Hepcidin treatment may alleviate sepsis-associated acute kidney injury through activating the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway to suppress ferroptosis in SAKI.