Introduction

The use of beneficial microorganisms in the food and pharmaceutical industries has a long history. Despite the beneficial effects of probiotics, recent studies have shown that there are challenges to the use of these bacteria. One of the challenges to use of probiotics is their ability to survive in complicated food matrixes or in vivo gastrointestinal tract. Another important challenge is the safety issues with the use of probiotics in certain groups, such as neonates [

1,

2] and vulnerable populations [

3]. More importantly, given the shared microbial environment in the gastrointestinal tract, there is a possible risk of transmitting antibiotic resistance genes through pathogenic microorganisms to other commensal probiotic and vice versa [

4]. In recent years, researchers have proposed various solutions to address these challenges and have suggested that one of the most effective and practical approaches in this regard is the use of heat-killed probiotics or their metabolites as alternatives [

5]. In 2021, the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) proposed the following definition for the term postbiotic: “a preparation of inanimate microorganisms and/or their components that confers a health benefit on the host” [

6]. Postbiotics, which contain varying biologically active components, have been extensively linked with improvements in nutrition and health. Especially in recent years, there has been growing evidence that postbiotics are useful tools in the fight against human diseases, and the focus of current research is gradually shifting from live probiotics to the postbiotics. For instance, in vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that postbiotics can play a role in boosting immunity [

7], preventing colon cancer [

8], maintaining oral health [

9], preventing osteoporosis [

10]and improving allergies [

11]. Multifunctional active postbiotics are preferred over probiotics because of its safety and stability, reduced risk of microbial translocation, infection or enhanced inflammatory response [

12].

Undoubtedly, these health benefits are related to the multifunctional activities of postbiotics. However, these functions of postbiotics usually have bacterial strain-specific characteristics. That is to say, different kinds of postbiotics derived from different strains of bacteria or different preparation processes have different functions. Therefore, the functions of a postbiotic need to be evaluated firstly by various methods including both in vitro and in vivo methods.

The biological activity of probiotics has been well documented, conversely, few studies have been able to demonstrate the multifunctional activity of postbiotics, which were prepared from probiotics [

13]. Many studies have revealed the great potential of postbiotics in the treatment of diseases. Herein, the aim of our study was to evaluate the anti-inflammatory, anti-hemolytic, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Postbiotic-P obtained from

Lactobacillus paracasei P6, which was obtained from the Lactic Acid Bacteria Collection Center of Qingdao Agricultural University, and deposited in the General Microbiology Center of the China Microbial Strain Deposit Management Committee with the deposit number CGMCC 26237. The study will promote the better applications of postbiotics in the food and pharmaceutical fields.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Reagents

Lactobacillus paracasei Postbio-P6 (

L. paracasei Postbio-P6) was obtained from the Lactic Acid Bacteria Collection Center of Qingdao Agricultural University.

L. paracasei Postbio-P6 was activated in Man Rogosa Sharpe (MRS, Qingdao HopeBiol Co., Qingdao, China) liquid media at 37 ℃ for 24 h aerobically. The indicator strains of antimicrobial assay are shown in

Table 1. All bacteria were cultured for 24 hours, and all fungi were cultured for 48 hours. Mouse erythrocyte solution was purchased from Jiangsu Kewei Biotechnology Co., and all the other chemicals used in study were analytically pure and obtained domestically.

Preparation of Postbiotic-P

The Postbiotic-P was prepared according to the method with some modifications [

11]. Revived

L. paracasei Postbio-P6 was inoculated into MRS medium (2%, V/V) and cultured at 37 °C for 24 h. Then the bacterial suspension was inactivated at 121 ℃ for 15 min. The inactivated suspension was ultrasonicated in an ice bath at 300 W, 10 S/10 S for 15 min, then microscopic examination was performed to determine that no intact bacteria existed. After that, the suspension was centrifuged (4 ℃, 6000 × g) for 10 minutes to remove the bacterial fragments. Cell-free supernatants (CFS) were obtained and were filtered through a 0.22 μm pore size membrane. The

L. paracasei Postbio-P6 CFS was firstly desalted by using Electrodialysis equipment (GUOCHU TECHNOLOGY, XiaMen, China) until the electrical conductivity reached 3.0 ms/cm. Then the desalted CFS was intercepted and subdivided by using ultrafiltration membranes of molecular weight cutoffs of 1, and 5 kDa, respectively (GUOCHU TECHNOLOGY, XiaMen, China). The 1-5 Kd ultrafiltrate was collected and stored at -20°C and named Postbiotic-P.

Antihemolytic Activity Assay

It has been reported that higher-than-normal blood temperatures cause thermolysis of red blood cells [

14]. Thus, well-known diseases (e.g., cancer, atherosclerosis, viral infections, gout) associated with body temperatures above the normal range (pyrexia, also termed fever) induce hemolysis of erythrocytes by affecting the bilayer of cell membranes [

15]. The antihemolytic activity of Postbiotic-P was determined according to the method of Shinde with minor modifications [

16]: 100% of Postbiotic-P was diluted to 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% with distilled water, respectively. Then aliquots of 500 µL of the diluted Postbiotic-P samples were mixed with 500 µL of mouse erythrocyte suspension, respectively. And the mixtures were incubated in a water bath at 56 °C for 30 min to induce hemolysis. After incubation, the sample tubes were immediately cooled in ice, centrifuged (2,500 × g, 5 min, 4 °C), and absorbance of the supernatants was recorded at 575 nm. Equal volume of isotonic solution (0.9% NaCl solution) incubated with mouse erythrocyte suspension and treated the same as Postbiotic-P set was used as positive control. Equal volume of isotonic solution (0.9% NaCl solution) mixed with mouse erythrocyte suspension but not heated was used as negative control. The percentage of inhibition of hemolysis was calculated by the equation:

in the formula:

X—hemolysis rate

A—Absorbance of test group

B—Negative control group absorbance

C—Positive control group absorbance

In-Vitro Anti-inflammatory Activity Test

Reversible protein oxidation plays an important role in modulating signaling pathways in cells, which can cause adverse effects contributing to inflammatory and metabolic diseases [

17]. Therefore, natural active substances with protein denaturation inhibitory effects may play a role in suppressing inflammation and thus be developed as anti-inflammatory agents [

18]. The in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of Postbiotic-P was determined by the albumin-inhibition denaturation method according to Chandra and co researchers with minor modifications [

19]. Specifically, 100% of Postbiotic-P was diluted to 80%, 60%, 40% and 20% with distilled water, respectively. Then, 25 μL egg white protein from fresh eggs, 350 μL PBS (pH 7.2, 0.01 M) and 250 μL different concentration of Postbiotic-P were mixed in a tube, respectively. The tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 15 minutes, followed by denaturation at 70 °C for 5 minutes. After denaturation, the tubes were rapidly cooled on ice for 5 min, and 200 μL of every sample was pipetted into a 96-well flat-bottomed enzyme-labelled plate, the absorbance at 660 nm was determined using an enzyme counter. Equal volume of distilled water instead of Postbiotic-P was used as negative control. Different concentrations of diclofenac sodium solution were used as reference to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activity of Postbiotic-P. The inhibition percentage of protein denaturation was calculated using the following formula:

in the formula:

X: Inhibition rate of protein denaturation

A: Absorbance of the sample

B: Absorbance of the control group

In Vitro Antioxidant Activity Assessment

Antioxidants have received increasing attention due to their protective role against oxidative deterioration and in vivo oxidative stress-mediated pathological processes in food and pharmaceutical products [

20]. Antioxidants are molecules that can safely interact with free radicals, stopping the chain reaction and transforming them into harmless molecules by donating an electron [

21]. Herein, the antioxidant activity of Postbiotic-P was evaluated through three different dimensions, i.e., reducing power, DPPH free radical scavenging activity and hydroxyl radical scavenging activity.

Determination of Reducing Power

Reducing power, which characterizes the ability of a substance to give up electrons for its own oxidation in redox reactions, is both an important manifestation of the antioxidant activity of a substance and a rational explanation of its antioxidant capacity [

22]. Based on the methodology by Benzie and Strain [

23], appropriate modifications were carried out to suit the present work: Serial dilutions of Postbiotic-P solutions of 50%, 40%, 30%, 20% and 10% were prepared with distilled water, respectively. 0.5 mL of different concentrations of Postbiotic-P were added to different test tubes, and then 0.5 mL of PBS (pH 7.2) and 0.5 mL of 1% aqueous potassium ferricyanide were added to each test tube and mixed well. The mixture was rapidly cooled by pacing the tubes in ice after a constant temperature water bath treatment at 50 °C for 20 min. 0.5 mL of trichloroacetic acid solution (10%, w/v) was added to the mixed solution and the supernatant was collected by centrifugation (2000 × g, 5 min). 1.0 mL of the supernatant was pipetted into 1.0 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride solution, mixed for 10 min, shook evenly on a vortex mixer, and 200 μL was transferred to a 96-well plate and the absorbance at 700 nm was measured. Different concentrations of vitamin C were used as control. Equal volume of PBS was used as blank control. The reducing power was calculated according to the formula:

A blank is the absorbance of the control using PBS instead of Postbiotic-P.

Measurement of DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

The DPPH radical is a stable free radical, which has been widely accepted as a tool for estimating the free radical scavenging activities of antioxidants [

24]. DPPH free radical scavenging capacity of Postbiotic-P was determined according to the method with appropriate modifications [

25]: DPPH was dissolved in ethanol to make the concentration of 0.2 mmol/L. 1 mL of the 0.2 mmol/ DPPH solution was added to 1 mL of different concentrations of postbiotics and mixed homogeneously. The samples were placed at 37 ℃ for 30 min in the dark. After that, the samples were centrifuged at 7000 x g for 10 min, and the absorbance of the supernatant was measured at a wavelength of 517 nm. The DPPH clearance was calculated:

where A

blank is the absorbance of the control using equal volume of distilled water instead of Postbiotic-P, A

0 is the absorbance of the control using equal volume of distilled water instead of DPPH.

Measurement of Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity

Hydroxyl radicals are the most reactive oxygen radicals in biological cells, causing oxidative damage to cells and tissues, leading to aging and chronic inflammation [

26,

27]. The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of Postbiotic-P was measured by a hydroxyl radical scavenging activity assay kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After reaction, the absorbance at 536 nm was measured. The hydroxyl radical scavenging rate was measured according to the instruction.

Antibacterial Activity

It has been reported that postbiotics may contain many kinds of antibacterial substances, such as bacteriocin, antibacterial peptide, exopolysaccharides and short chain fatty acid [

28,

29]. It has been shown that postbiotics have a significant inhibitory effect on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [

30]. The antimicrobial activity of Postbiotic-P and its antibacterial spectrum were investigated according to the method of Setyo Putri et al. with appropriate modifications [

31]: Namely, each target bacteria or fungi was incubated for 16 hours for activation and set aside. The Postbiotic-P was centrifuged at 8000 x g for 10 min, and the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm filter membrane before use. The revived indicator bacteria were adjusted to 10

7 CFU/mL with phosphate buffer saline, mixed with sterilized molten nutrient agar (1%, V/V), and poured (20 mL per assay) into fresh sterile plates. After the medium has solidified, use a hole punch to make 8 mm diameter holes in the medium. Inject 200 μL of Postbiotic-P or PBS into the wells, make three replicates, and put them at 4 ℃ for diffusion for 4 hours, then incubate the bacteria at 37 ℃ for 12 hours, and incubate the fungi at 30 ℃ for 48 h, and measure the size of the zone of inhibition. The same volume of PBS was used as negative control.

The Effects of Postbiotic-P on the Peroxide Value and Malondialdehyde Content in Cookies

During food storage, oxidation and microbial proliferation typically occur, resulting in the generation of many harmful substances such as free radicals and malondialdehyde [

32]. Considering the multi-functions of Postbiotic-P, its effects on the peroxide value and malondialdehyde content in cookies were investigated.

Different concentrations of Postbiotic-P (1%, 2%, 3%, 4% and 5%) were added to the raw materials for making cookies. After baking, the peroxide values and malondialdehyde contents in the cookies were measured. The antioxidant values of the cookies were determined according to the method outlined by Cirlini et al. (2012) [

52]. Specifically, 0.1 g of cookies was weighed into a 100 mL conical flask, to which 20 mL of methylene chloride/glacial acetic acid solution (2/3, v/v) was added. After complete dissolution of the sample, 1 mL of saturated potassium iodide solution was added. The solution was then stored in the dark at 25 ℃ for 16 hours. Following this, 20 mL of distilled water was added to the solution, which was titrated with 0.05 M sodium thiosulfate solution, with 1 mL of starch solution added as an indicator. The peroxide value was calculated according to the following equation:

In the formula: X is the peroxide value; V is the volume of standard solution of sodium sulfate consumed by samples; V0 is the volume of standard solution of sodium sulfate consumed by blank tests; C is the concentration of the standard solution of sodium sulfate; m is the sample weight.

The malondialdehyde contents in cookies were determined following a method with minor adjustments as outlined by Castrejón and Yatsimirsky (1997) [

33]: Specifically, 2.0 mL of 0.03 M thiobarbituric acid (TBA) was mixed with 2.0 mL of each sample and incubated at 94 °C for 15 min. After cooling, the absorbance at 532 nm was measured. A calibration curve was constructed based on the absorbances of mixtures containing 2.0 mL of 0.1-10 µM malondialdehyde working solution in 0.1 M perchloric acid and 2.0 mL of 0.03 M TBA solution. The malondialdehyde contents in the samples were calculated using the following formula:

In the formula: X is the malondialdehyde contents of the samples; C is the malondialdehyde concentration in the sample solution obtained from the standard curve; V is the constant volume of the sample solution; m is the weight of the sample.

Statistical Analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-test (SPSS 19.0) with P < 0.05 considered as significant.

Results and Discussion

Antihemolytic Activity of Postbiotic-P

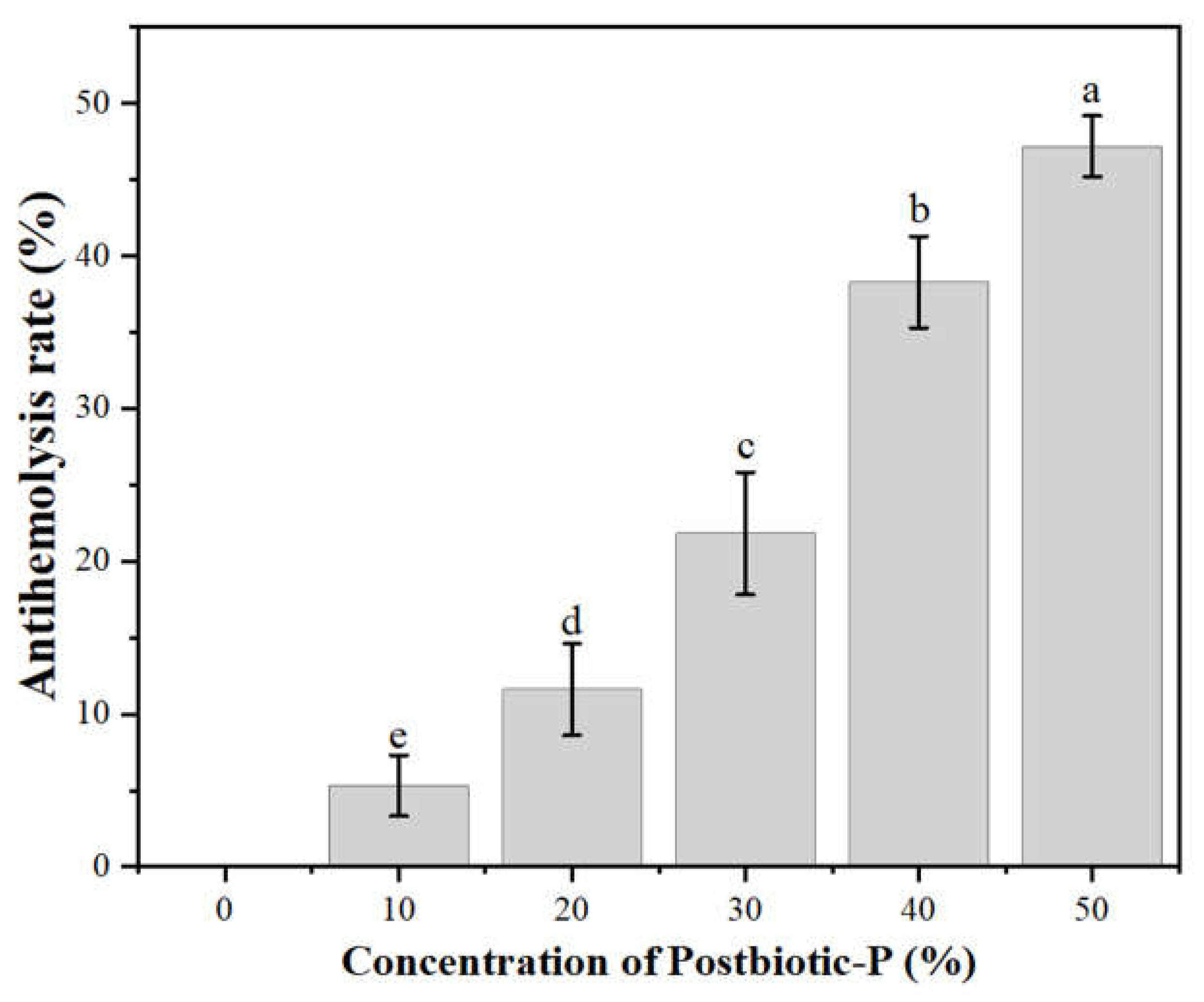

The antihemolytic activity of Postbiotic-P was shown in

Figure 1. The results showed that Postbiotic-P could inhibit the hemolysis of mouse erythrocytes. Moreover, with the increase of Postbiotic-P concentration, the antihemolytic rate also significantly increased (

P <0.05), indicating that the antihemolytic activity of Postbiotic-P against mouse erythrocytes was dose-dependent manner.

The mechanisms underlying the antihemolytic activity of postbiotics are not well understood. However, it has been reported that some bioactive peptides in fermented milk can enhance the stability of the erythrocyte membrane and its resistance to shear stress, and also reduce the sensitivity of the cell membrane to thermal damage, protecting erythrocytes from destruction during the heat period [

34,

35]. Therefore, it is suggested that Postbiotic-P may perform its antihemolytic activity by enhancing the stability of the erythrocyte membrane.

Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Postbiotic-P

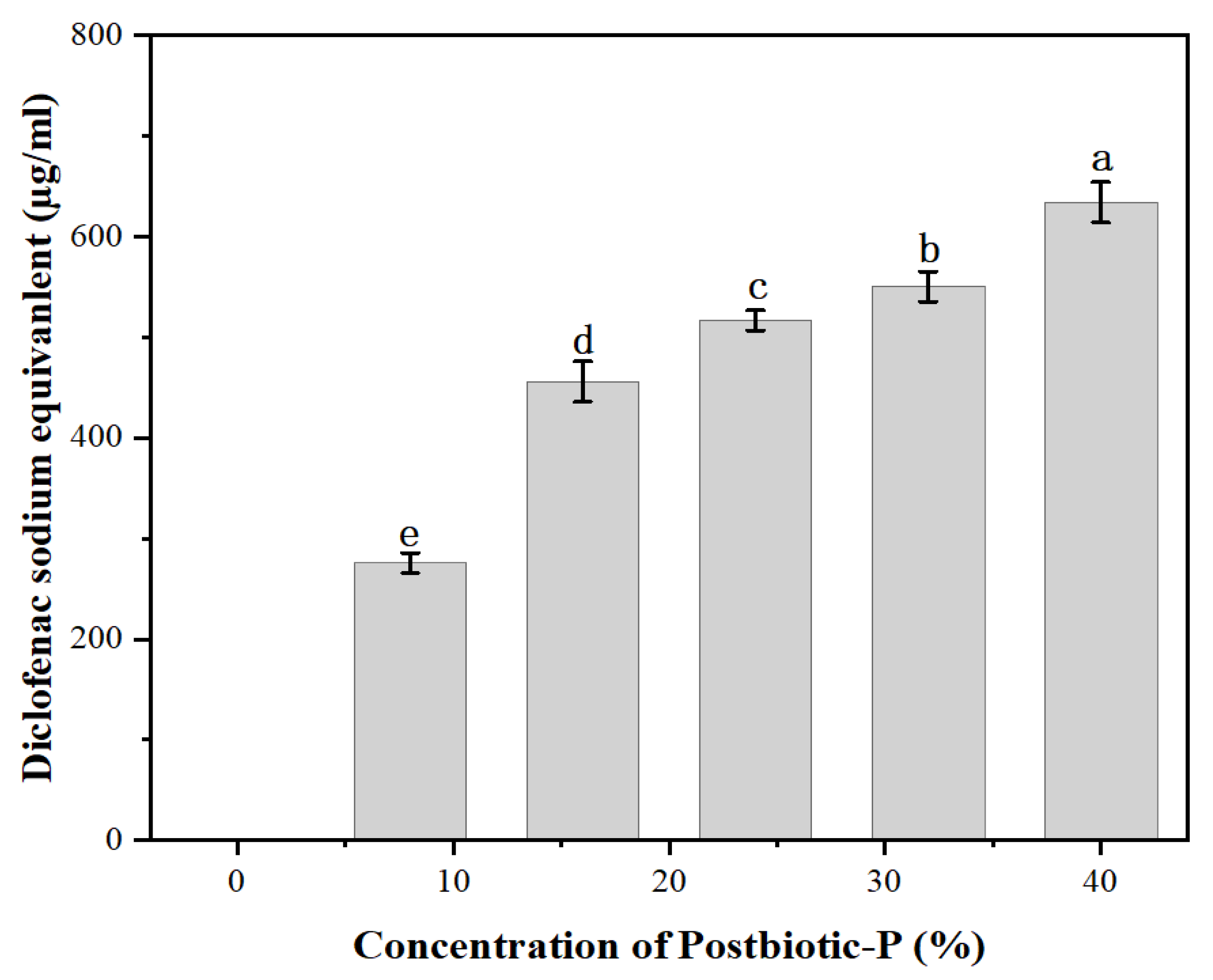

The protein denaturation inhibition rate of Postbiotic-P was expressed as the diclofenac sodium equivalents. As shown in

Figure 2, Postbiotic-P could effectively inhibit protein denaturation. With the increase of Postbiotic-P concentration, the protein denaturation inhibition rate also significantly increased (

P <0.05), suggesting that the anti-inflammatory activity of Postbiotic-P was dose-dependent manner. In particular, 8% to 40% Postbiotic-P showed the anti-inflammatory activity which was comparable to 259.1-645.4 μg/mL of diclofenac sodium equivalents, indicating Postbiotic-P can be used as a potential anti-inflammatory drug for inflammatory diseases.

A previous study has shown that milk-derived peptides have inhibitory effects on heat-induced protein denaturation, and the crude extract of

L. plantarum 55 or its fractions have high anti-inflammatory activity, with diclofenac sodium equivalents ranging from 723.68 to 1,759.43 μg/mL [

15]. In addition, it has been also proved that several natural active substances such as water lily extracts [

36], Cassia Oleifera Extract [

37] and anti-inflammatory drugs such as NSAIDs [

38] can exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting heat-induced protein denaturation. Obruca et al. have investigated the anti-inflammatory mechanisms and proved that some substances affect the hydrated shells around proteins and other biomolecules, thereby creating a protection for the proteins against denaturation caused by environmental changes [

39]. However, the anti-inflammatory mechanism of Postbiotic-P needs to be further studied.

In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Postbiotic-P

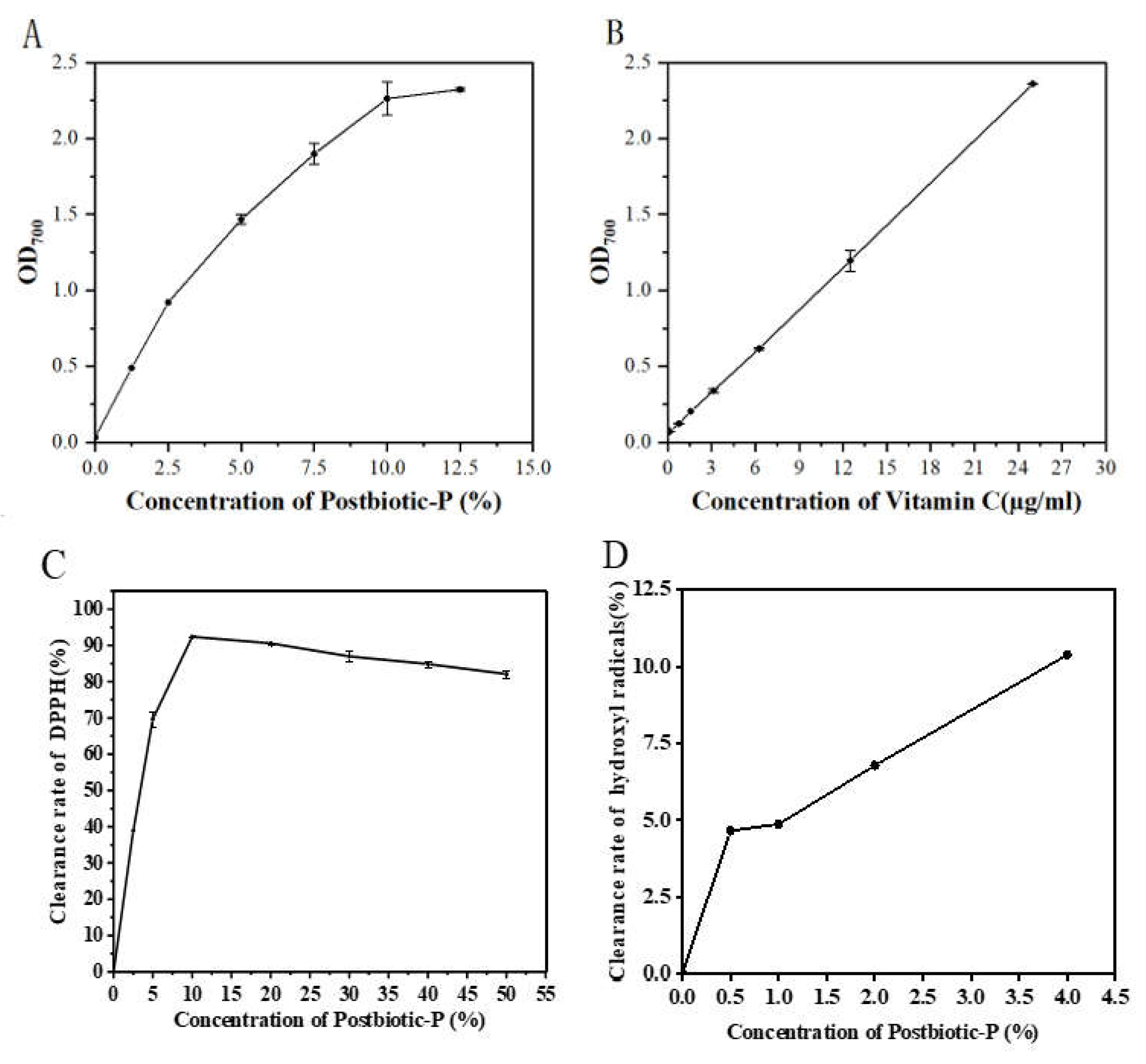

Reducing Power

In the reducing power detection assay, the reducing agent reduces the Fe

3+/ferricyanide complex to the ferrous form, which can be monitored by measuring the formation of Perplex Blue that can be measured at an absorbance of 700 nm [

40]. Our results showed that Postbiotic-P exhibited a strong reducing power that progressively increased with the increase of its concentration. In particular, the reducing power of 12.5% Postbiotic-P is comparable to that of 25 μg/mL vitamin C. It was reported that the extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) from endophytic bacterium

Paenibacilluspolymyxa EJS-3 had some reducing ability and the reducing ability of crude EPS was higher than that of the purified fraction (EPS-1 and EPS-2), probably due to the fact that the crude EPS contained other antioxidant components such as proteins, amino acids, peptides, and organic matter [

41]. It was found that the reducing power values of heat-inactivated phytoalexins Ln1 and KCTC 3108 were 45.90 and 60.75 μM at 10

7 CFU/mL [

42]. Although the reduction mechanism of Postbiotic-P is not clear, it has been shown that some natural substances, which can act as an electron donor, react with free radicals and convert them into more stable products, thus terminating the free radical chain reaction [

40].

DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Activity

DPPH radicals are usually used to evaluate the anti-oxidant capacity of anti-oxidants. In the assay, after the DPPH radicals are removed by the antioxidants, the color of the reaction mixture changes from purple to yellow, and the absorbance at 517 nm decreases [

43]. Our results showed that the DPPH radicals scavenging capacity of Postbiotic-P was dose-dependent manner. And when the concentration was 10%, the DPPH radicals scavenging capacity reached its maximum value of 92.4%, indicating the strong DPPH radicals scavenging capacity of Postbiotic-P.

Consistently, several reports have reported the DPPH radicals scavenging capacity. Jang et al. proved that the inactivated

Lactobacillus plantarum Ln1 scavenged 17.60% of DPPH radicals at a concentration of 10

7 CFU/mL [

42]. A kind of postbiotic named postbiotic RG14 prepared from

Plant yeast RG14 fermentation cell-free supernatant was proved to exhibit high antioxidant activity against DPPH free radicals and also enhance glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity in vivo [

44]. Another kind of postbiotic obtained by co-fermentation of

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens J and

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SN4 showed similar activity to ascorbic acid in terms of DPPH scavenging capacity [

45]. Therefore, postbiotic may be a good antioxidant which can have good application potential in medical, health care products and functional foods.

Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Activity

Like the DPPH free radical scavenging activity of Postbiotic-P, the results showed that Postbiotic-P possessed the hydroxyl radicals scavenging capacity with a dose-dependent manner. And when the concentration was 4%, the hydroxyl radicals scavenging capacity was 10.38% but did not reach maximum value, indicating the strong hydroxyl radicals scavenging capacity of Postbiotic-P.

Jang et al. reported that the intracellular extracts of

Lactobacillus plantarum exhibited high antioxidant activity in the concentration range of 10

8 to 10

10 CFU/mL with certain dose-dependence and strain-specificity, and a strain of

L. plantarum named

L. plantarum C88 had the strongest scavenging ability of hydroxyl radicals with a scavenging rate of 44.31% at a cell concentration of 10

10 CFU/mL. Further studies confirmed that the active components responsible for the antioxidant activity may be cell surface proteins or polysaccharides [

42]. In addition, Li et al. proved that the EPS from

L. helveticus MB2-1 had strong scavenging activity against hydroxyl radicals. And at a concentration of 4 mg/mL, the hydroxyl radical scavenging ability of crude EPS was 80.24%, which was higher than that of its purified fraction, which may be attributed to the presence of other antioxidant components such as proteins, peptides and trace elements in the crude EPS [

46]. One of the mechanisms of its hydroxyl radicals scavenging capacity might be due to the active hydrogen-donating capacity of hydroxyl substituents in EPS.

.

Antimicrobial Activity

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines were used to evaluate the drug sensitivity pattern of Postbiotic-P against different bacteria and fungi. The size of the zone of inhibition> 20 mm is extremely sensitive, 15-20 mm is highly sensitive, 10-14 mm is moderately sensitive, < 10 mm is hypoallergenic, and 0 is resistant. The results showed that Postbiotic-P exhibited different degree of antimicrobial activity against 15 indicator bacteria and two fungi (

Table 2): strong inhibitory activity against

S. aureus,

Y. enteritis and

E. coli; moderate inhibitory activity against

L. monocytogenes,

S. typhimurium,

P. fluorescens,

P. putida,

P. fragi and

E. sakazakii; weak inhibitory against

P. lundensis and

A. flavus; and no inhibitory activity against

B. cereus,

P. aeruginosa,

P. citri and some common LAB and/or probiotic bacteria such as

L. plantarumP-8,

L. rhamnosus Probio-M9 and

L. paracasei Zhang, were observed.

Significantly, Postbiotic-P exerted good antibacterial activity against several food spoilage bacteria, such as P. fluorescens, P. putida and P. fragi, indicating Postbiotic-P has the potential to be applied in food preservation. In addition, Postbiotic-P exerted no inhibitory effect on LAB or probiotics, which makes Postbiotic-P a desirable food biopreservative, which would not alter the endogenous and beneficial gut microbiota when applied in food.

Many studies proved the antibacterial activities with broad antibacterial spectrum. For example, Kareem et al. reported that the cell-free supernatants from

Lactobacillus plantarumstrains RG11, RG14, RI11, UL4, TL1, and RS5 have significant inhibitory activity against a variety of pathogenic bacteria, including

L. monocytogenes L-MS,

Salmonella spp. S-1000,

E. coli E-30, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci [

47]. A kind of postbiotic from

L. casei can significantly inhibit the formation of virulence factors and biofilms, such as

Pseudomonas aeruginosa pusillin and rhamnolipids, and effectively reduce virulence attack and adhesion of harmful bacteria [

48]. Some of the biosurfactants from probiotics have antimicrobial and anti-biofilm effects, disrupting biofilm integrity, leading to cytoplasmic loss and preventing bacterial and fungal colonization [

49]. Biosurfactants produced by

Lactococcuslactis and

L. plantarum was found to interfere with

S. aureus biofilm formation and slightly inhibit

S. aureus growth [

50]. The antibacterial activity of postbiotics was mainly because they are rich in many kinds of antibacterial active components such as bacteriocin, antibacterial peptide, exopolysaccharides and short chain fatty acid [

28,

29,

51] and the different degrees of antibacterial activity and different antibacterial spectrum are due to their different components.

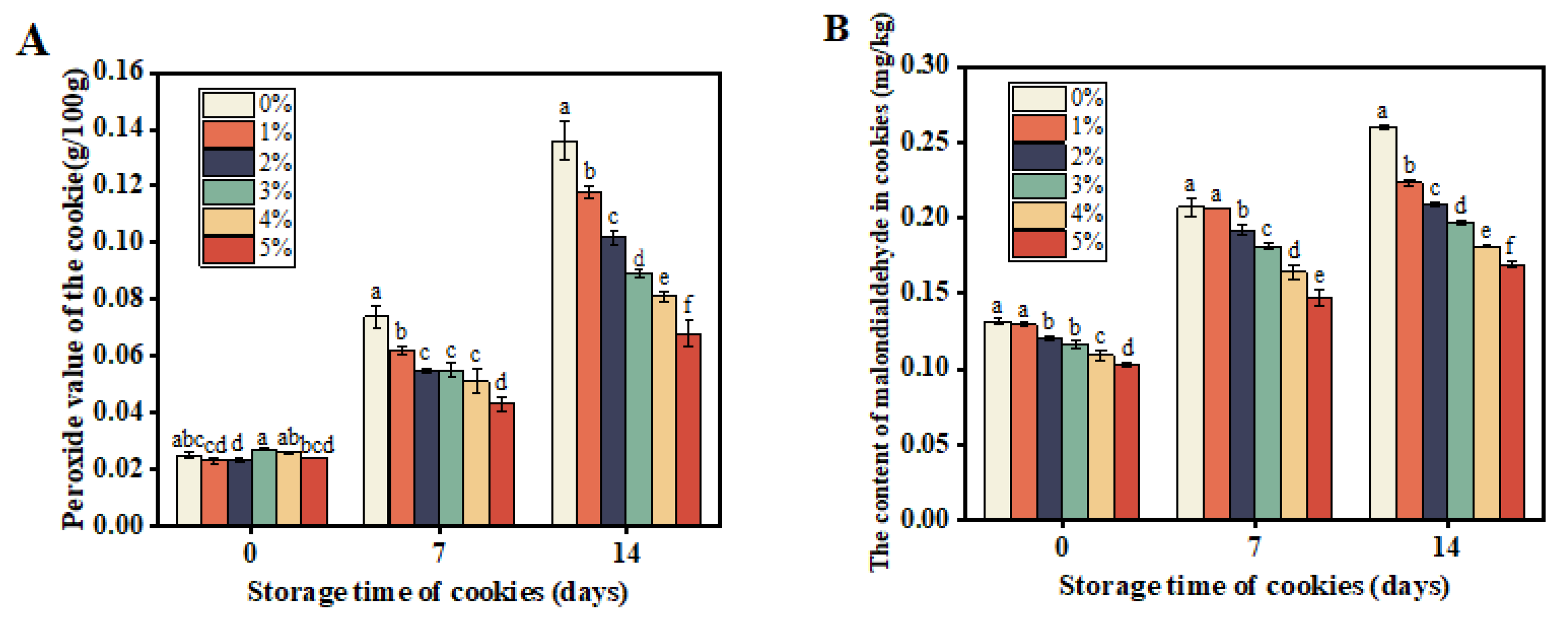

The Effects of Postbiotic-P on the Peroxide Value and Malondialdehyde Content in Cookies

The peroxide value serves as a common indicator to gauge the extent of lipid oxidation in food. The generation of malondialdehyde in food typically arises from chemical reactions involving fats, proteins, and carbohydrates, influenced by elevated temperatures, oxygen exposure, and microbial activity. As depicted in

Figure 4A, peroxide values increased in all samples during storage. However, compared to the control (non-Postbiotic-P sample), the increases of the peroxide value in cookies with Postbiotic-P were significantly inhibited. Moreover, with higher concentrations of Postbiotic-P, the rise in peroxide value decreased notably. Similarly, the malondialdehyde contents in cookies with varying concentrations of Postbiotic-P followed the same trend as peroxide value changes (

Figure 4B). These findings suggest that Postbiotic-P may attenuate food spoilage by inhibiting oxidation and malondialdehyde formation, underscoring its potential in food preservation. Nonetheless, further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Conclusions

The present study prepared a postbiotic named Postbiotic-P by intercepting 1-5 KD of the cell-free supernatants of L. caseiparacasei P6 fermentation broth, and reports the multiple combine dactivities, namely anti-inflammatory, antihemolytic, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. Of these, the antihemolytic and anti-inflammatory activities of Postbiotic-P indicate its potential to protect from some damages induced by series of diseases, the antioxidant activity indicates its potential to decrease the oxidation pressure of tissues, and the antibacterial activity against many foodborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria but not LAB or probiotics indicates its potential application in food safety. Moreover, the inhibition of oxidation and malondialdehyde formation of Postbiotic-P indicates its good potential in food preservation. Taken together, the results indicate that Postbiotic-P from L. caseiparacasei P6 possesses valuable potential as dietary bioactive compounds for the development of health care products and functional foods. However, further studies are needed to determine their precise mechanism of action, to clarify the active components responsible for the function, and to validate the biological activities in animal models or clinical trials.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2020MC217).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Boyle, R.J.; Robins-Browne, R.M.; Tang, M.L. Probiotic use in clinical practice: what are the risks? The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006, 83, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, A.; Takahashi, S.; Ito, Y.; Ohishi, Y.; Tsukamoto, K.; Nanba, Y.; Ito, N.; Kakiuchi, S.; Saitoh, A.; Morotomi, M.; et al. Bifidobacterium septicemia associated with postoperative probiotic therapy in a neonate with omphalocele. The Journal of pediatrics. 2010, 156, 679–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, J.Z.; Yap, C.; Lytvyn, L.; Lo, C.K.; Beardsley, J.; Mertz, D.; Johnston, B.C. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 12, Cd006095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperial, I.C.V.J.; Ibana, J.A. Addressing the antibiotic resistance problem with probiotics: reducing the risk of its double-edged sword effect. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016, 7, 232849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, S.; Singh, R. Antibiotic resistance in food lactic acid bacteria—a review. International journal of food microbiology. 2005, 105, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 18(649) 667. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell, P.; Alvarez, B.; Llopis, S.; et al. Heat-treated Bifidobacterium longum CECT-7347: A whole-cell postbiotic with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and gut-barrier protection properties. Antioxidants. 2021, 10, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; et al. Inhibitory effect of a microecological preparation on azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate-induced inflammatory colorectal cancer in mice. Frontiers in oncology. 2020, 10, 562189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homayouni, rad, A. ; Pourjafar, H.; Mirzakhani, E.J.F.I.C.; et al. A comprehensive review of the application of probiotics and postbiotics in oral health. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2023, 13, 1120995. [Google Scholar]

- Myeong, J-Y. ; Jung, H-Y.; Chae, H-S.; et al. Protective effects of the postbiotic Lactobacillus plantarum MD35 on bone loss in an ovariectomized mice model. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, M.; Molaei, R.; Guimarães, J.T. A review on preparation and chemical analysis of postbiotics from lactic acid bacteria. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2021, 143, 109722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taverniti, V.; Guglielmetti, S. The immunomodulatory properties of probiotic microorganisms beyond their viability (ghost probiotics: proposal of paraprobiotic concept). Genes & nutrition. 2011, 6, 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, B.; Xing, D. The current and future perspectives of postbiotics. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2023, 15, 1626–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChernitskiĬ, E.; IamaĬkina, I. Thermohemolysis of erythrocytes. Biofizika. 1988, 33, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-toalá, J.; Santiago-lópez, L.; Peres, C.; et al. Assessment of multifunctional activity of bioactive peptides derived from fermented milk by specific Lactobacillus plantarum strains. Journal of dairy science. 2017, 100, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, U.; Phadke, A.; Nair, A.; et al. Membrane stabilizing activity—a possible mechanism of action for the anti-inflammatory activity of Cedrus deodara wood oil. Fitoterapia. 1999, 70, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickett, C.M.; Verrastro, I.; Pitt, A.R. Protein oxidation and protein redox interactions in metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2017, 108, S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheb, L.; Wang, H-J. ; Ji, T-F.; et al. Chemoproteomics-based target profiling of sinomenine reveals multiple protein regulators of inflammation. Chemical Communications. 2021, 57, 5981–5984. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Chatterjee, P.; Dey, P.; et al. Evaluation of in vitro anti-inflammatory activity of coffee against the denaturation of protein. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012, 2, S178–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Archives of toxicology. 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; et al. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacognosy reviews. 2010, 4, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchsinger, W.W.; Cornesky, R.A. Reducing power by the dinitrosalicylic acid method. Analytical biochemistry. 1962, 4, 346–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Analytical biochemistry. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-moreno, C.J.F.S.; International, T. Methods used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity in foods and biological systems. Food Sci Technol Int. 1995, 28, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, O.P.; Bhat, T.K. DPPH antioxidant assay revisited. Food chemistry. 2009, 113, 1202–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korycka-dahl, M.B.; RichardsonI, T.; Foote, C.S.J.C.R.I.F.S.; et al. Activated oxygen species and oxidation of food constituents. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition. 1978, 10, 209–241. [Google Scholar]

- Del, valle, L. G. Oxidative stress in aging: theoretical outcomes and clinical evidences in humans. Biomedicine & Aging Pathology. 2011, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aghebati-maleki, L.; Hasannezhad, P.; Abbasi, A.; et al. Antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, and anticancer activities of postbiotics: a review of mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 12, 2629–2645. [Google Scholar]

- Sevins, S.; Karaca, B.; Haliscelik, O.; et al. Postbiotics secreted by Lactobacillus sakei EIR/CM-1 isolated from cow milk microbiota, display antibacterial and antibiofilm activity against ruminant mastitis-causing pathogens. Italian Journal of Animal Science. 2021, 20, 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-ghany, W.A. Paraprobiotics and postbiotics: Contemporary and promising natural antibiotics alternatives and their applications in the poultry field. Open veterinary journal. 2020, 10, 323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Setyo, putri, A.Y.; Purwanta, M.; Indiastuti, D.; et al. Antibacterial Activity Test of Jatropha multifida L. sap against Staphylococcus aureus and Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in vitro. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2021, 15. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marta, Fernáíndez-Garcia; Pedro, J.Zapata. Food oxidation and shelf life: Definition and potential applications of natural antioxidatants. Food reviews International 2011, 27, 191–217.

- Castrejon, S.E.; Ysstumirsk, A. K. Cyclodextrin enhanced fluorimetric determination of malonaldehyde by the thiobarbituric acid method. Talanta. 1997, 44, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Guo, X.; Coppel, R.; et al. The ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen (RESA) of Plasmodium falciparum stabilizes spectrin tetramers and suppresses further invasion. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2007, 110, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, sliva, E. ; Foley, M.; Dluzewski, A.R.; et al. The Plasmodium falciparum protein RESA interacts with the erythrocyte cytoskeleton and modifies erythrocyte thermal stability. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 1994, 66, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A; Khan, H.; Rauf, A.; et al. Inhibition of thermal induced protein denaturation of extract/fractions of withania somnifera and isolated withanolides. Natural Product Research. 2015, 29, 2318–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, A.A.; PUNITHA. S.M.J.; REMA.M. Anti-inflammatory activity of flower extract of Cassia auriculata-an in-vitro study. International Research Journal of Pharmaceutical and Applied Sciences. 2014, 4, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- MizushimaI, Y.; Kobayashi, M. Interaction of anti-inflammatory drugs with serum proteins, especially with some biologically active proteins. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 1968, 20, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obruca, S.; Sedlacek, P.; Mravec,F. ; et al. Evaluation of 3-hydroxybutyrate as an enzyme-protective agent against heating and oxidative damage and its potential role in stress response of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) accumulating cells. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2016, 100, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y-C. ; Chang, C-T.; Chao, W-W.; et al. Antioxidative activity and safety of the 50 ethanolic extract from red bean fermented by Bacillus subtilis IMR-NK1. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2002, 50, 2454–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Ye, H.; et al. Production, characterization and antioxidant activities in vitro of exopolysaccharides from endophytic bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa EJS-3. Carbohydrate polymers. 2009, 78, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.J.; Song, M.W.; Lee, N-K. ; et al. Antioxidant effects of live and heat-killed probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Ln1 isolated from kimchi. Journal of food science and technology. 2018, 55, 3174–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Tseng, K.C.; Chiang, S.S.; et al. Immunomodulatory and antioxidant potential of Lactobacillus exopolysaccharides. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2011, 91, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izuddin, W.I.; Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; et al. Dietary postbiotic Lactobacillus plantarum improves serum and ruminal antioxidant activity and upregulates hepatic antioxidant enzymes and ruminal barrier function in post-weaning lambs. Antioxidants. 2020, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong,Y. ; Abbas, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. Optimizing postbiotic production through solid-state fermentation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens J and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum SN4 enhances antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2023, 14, 1229952. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Ji, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Structural elucidation and antioxidant activities of exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus helveticus MB2-1. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2014, 102, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareem, K.Y.; Hool, ling, F. ; Teck, chwen, L.; et al. Inhibitory activity of postbiotic produced by strains of Lactobacillus plantarum using reconstituted media supplemented with inulin. Gut pathogens. 2014, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azami, S.; Arefian, E.; Kashef, N. Postbiotics of Lactobacillus casei target virulence and biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by modulating quorum sensing. Archives of Microbiology. 2022, 204, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satpute, S.K.; Kulkarni, G.R.; Banpurkar, A.G.; et al. Biosurfactant/s from Lactobacilli species: Properties, challenges and potential biomedical applications. Journal of basic microbiology. 2016, 56, 1140–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Gu, S.; Cui, X.; et al. Antimicrobial, anti-adhesive and anti-biofilm potential of biosurfactants isolated from Pediococcus acidilactici and Lactobacillus plantarum against Staphylococcus aureus CMCC26003. Microbial pathogenesis. 2019, 127, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.G.; Moreira, D.A.; Gullón, P.; et al. Topical application of probiotics in skin: adhesion, antimicrobial and antibiofilm in vitro assays. Journal of applied microbiology. 2017, 122, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirlin, M.; Caligiani, A.; Palla, G.; et al. Stability studies of ozonized sunflower oil and enriched cosmetics with a dedicated peroxide value determination. Ozone: Science & Engineering. 2012, 34, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).