1. Introduction

The potential applications of nanoparticles have expanded dramatically in recent years, driven by their distinctive physicochemical properties such as a high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable size and shape, and versatile surface functionality [

1,

2,

3]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) have emerged as a key class of materials in biomedical and functional-membrane applications [

4,

5,

6]. In healthcare, AgNPs are incorporated not only into conventional formats (such as antimicrobial wound dressings and burn-treatment materials) but increasingly into membrane and composite platforms, such as nanofiber mats, hydrogel membranes, or polymeric scaffolds, in which the nanoparticles are embedded. These composite membranes enable controlled release, improved integration of the nanoparticles within a structural matrix, enhanced mechanical stability, and a more uniform distribution of the active agent, thus extending the functionality of AgNPs beyond free colloids [

7]. Such membrane-based platforms offer the advantages of combining structural support, provided by the membrane, with antimicrobial, sensing, or catalytic activity, provided by the AgNPs, in a single construct [

8,

9].

Beyond healthcare, AgNP-functionalised membranes have been applied in water purification [

10], antimicrobial packaging [

11], and smart textiles [

12], among other applications, where embedding nanoparticles within a matrix provides improved stability, easier handling, reduced leaching, and enhanced application versatility.

Despite the clear functional advantages of nanoparticles, their production often relies on conventional physical or chemical synthesis methods, which typically involve hazardous reagents or generate toxic by-products [

13]. By contrast, green chemistry approaches using biological or plant-derived reducing and capping agents operate under milder, more environmentally benign conditions, offer improved control over reaction kinetics, morphology, and crystallinity, and align with broader sustainability goals. Green synthetic routes for AgNPs have been identified as promising for reducing environmental impact and increasing biocompatibility [

14,

15].

In this context, the design of functional membranes that embed green-synthesised AgNPs becomes especially compelling. Among biopolymeric scaffolds, bacterial cellulose (BC) stands out due to its exceptional physicochemical properties. BC is produced via microbial fermentation, exhibits high purity, features an ultrafine porous nanofibrillar network, and shows remarkable mechanical strength, excellent water retention, and inherent biocompatibility [

16]. These characteristics make BC well suited as a matrix for the development of advanced nanocomposite membranes.

Traditional approaches to loading nanoparticles into membranes (e.g., post-synthesis impregnation, electrostatic adsorption, or layer-by-layer deposition) often suffer from poor penetration of particles into the scaffold, non-uniform distribution, and variable loading efficiency [

17,

18]. In contrast, an in situ synthesis approach within the BC matrix can enable the direct conversion of metal-ion precursors (e.g., AgNO

3) into nanoparticles embedded in the BC network, yielding a more uniform nanoparticle distribution, enhanced matrix–nanoparticle interactions, and improved stability and functionality in the resulting nanocomposite [

19].

The objective of this study is to characterize the production of bacterial-cellulose (BC) membranes functionalized with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) via green synthesis methods. Specifically, we explore the use of plant extracts from mint (Mentha spicata) and avocado (Persea americana) as dual reducing and stabilizing agents for AgNP formation under varied synthesis conditions (precursor concentration, temperature, pH), and we subsequently integrate those nanoparticles into BC membranes.

While many studies have used leaf extracts from medicinal or ornamental plants (e.g.,

Azadirachta indica [

20],

Curcuma longa [

21],

Moringa oleífera [

22]

) for AgNP synthesis, fewer investigations have specifically employed avocado or mint extracts.

According to Shahzadi et al. (2025), the type and concentration of phytochemicals in a plant extract (for example, flavonoids, phenolics, terpenoids, alkaloids) substantially influence nanoparticle formation, morphology, and stability [

23].

In our system, both mint and avocado extracts act simultaneously as reducing and stabilizing agents. The distinct phytochemical profiles of the two extracts likely lead to differences in nucleation and growth kinetics as well as in the final nanoparticle morphology. For example, mint extracts may contain higher proportions of phenolic compounds than avocado extract, thereby altering reduction potential and capping efficiency [

24]. Although we did not quantify phytochemical content in each extract in this work, our results, such as distinct UV–Vis spectral features under different conditions, reflect these differences.

By combining BC’s structural resilience and inherent biocompatibility with an environmentally friendly synthesis of AgNPs, we aim to develop membranes with significant application potential in antimicrobial therapies, wound-healing dressings, water-filtration membranes, antimicrobial packaging, and other functional membrane systems, while avoiding toxic reagents during the nanoparticle synthesis step.

2. Materials and Methods Reagents Used

The plant materials, avocado seeds and mint leaves, were sourced locally from Barcelona, Spain. Silver nitrate (≥99% purity) was procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific and served as the silver- ion precursor. To adjust pH during nanoparticle synthesis, 0.1M NaOH and 0.1M HCl solutions were prepared, enabling control over the reaction environment. A 0.1% (w/v) sodium citrate solution (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the reaction mixture as a stabilizer to prevent nanoparticle agglomeration and promote colloidal stability.

2.1. Preparation of Bacterial Cellulose Membranes

Bacterial cellulose (BC) membranes were prepared using the acetic-acid bacterium

Komagataeibacter hansenii (ATCC 53582), a well-established model organism for BC biosynthesis [

25]. The process began by preparing a liquid-phase inoculum: the strain was cultured in Hestrin–Schramm (HS) medium (glucose 20 g L

−1, yeast extract 5 g L

−1, peptone 5 g L

−1, sodium phosphate dibasic 2.7 g L

−1, citric acid 1.1 g L

−1) at an initial pH of ~5.5. The preculture was incubated at 30 °C under orbital agitation at 200 rpm for 3 days to ensure high cell density.

Following preculture, sterile trays containing 250 mL of fresh HS medium were inoculated with 20% (v/v) of the liquid culture. The trays were then incubated under static conditions at room temperature, allowing BC pellicles to form progressively at the air–liquid interface for 5 days. Upon completion of the cultivation period, BC membranes were harvested and purified by immersion in a 0.1M NaOH solution at 80 °C for 30 min to remove bacterial cells and associated impurities, e.g., proteins and DNA, in accordance with standard procedures [

26]. Following the alkaline treatment, membranes were thoroughly rinsed multiple times with distilled water until pH ≈ 7 was achieved.

2.2. Avocado Seed Extract

Avocado seeds were collected, finely chopped, and transferred into a beaker containing distilled water. The mixture was heated at 50 °C for 40 min to facilitate the extraction of reducing phytochemicals, e.g., phenolics, flavonoids, polysaccharides. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was vacuum-filtered using an MF-Millipore™ filter with 5 µm pore size to remove solid debris. The resulting filtrate constituted the avocado seed extract, which was stored in airtight containers at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Mint Leaf Extract

Fresh mint leaves (0.5g) were thoroughly washed with distilled water to remove surface impurities. The cleaned leaves were incubated in a known volume of distilled water and heated, for instance, boiled until 70 mL remained from an initial 100 mL, in accordance with common protocols [

27]. After heating, the extract was cooled to room temperature and vacuum-filtered using an MF-Millipore™ filter with 5 µm pore size. The clear filtrate was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C for subsequent nanoparticle synthesis.

2.4. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mint and Avocado Extracts in Aqueous Media

Silver nitrate (AgNO

3) was dissolved in Milli-Q water to prepare precursor solutions at varying concentrations (0.01, 0.0075, 0.005, 0.002 and 0.001 M). These concentrations allowed control over nanoparticle nucleation density and size, consistent with literature indicating that higher AgNO

3 concentrations often increase nucleation rates and can shift the LSPR peak position depending on growth and aggregation behavior [

28].

To explore the influence of the reaction environment on nanoparticle formation, syntheses were conducted at three temperatures (4 °C, 23 °C and 70 °C) and under three pH conditions (acidic pH=5, neutral pH=7 and basic pH=11), adjusted using 0.1M HCl or NaOH

For low-temperature synthesis at 4 °C, reactions were carried out in an ice bath. Plant extracts were added dropwise to the AgNO3 solution at a 1:1 volume ratio to promote controlled nucleation. After mixing, the reaction mixture was incubated at 4 °C with gentle shaking at 120 rpm for 24 h.

For room and elevated temperatures (23 °C and 70 °C), the same 1:1 extract-to-AgNO3 ratio was used, and reaction mixtures were incubated at the respective temperatures with shaking at 120 rpm for 24 h.

In all syntheses, a 0.1% (w/v) sodium citrate solution was included as a stabilizing agent to prevent nanoparticle agglomeration, consistent with commonly used green-synthesis approaches [

29,

30]. Verification of AgNP formation relied initially on the characteristic color change of the reaction mixture, which is a qualitative indicator of nanoparticle formation associated with localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR). UV–Vis spectroscopy was subsequently employed to monitor LSPR features and shifts, which can reflect changes in nanoparticle size distribution and aggregation state [

31,

32,

33].

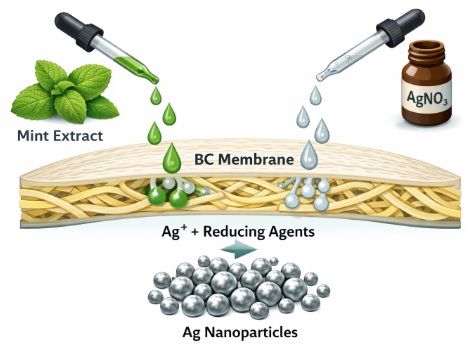

2.5. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts (Mint and Avocado) Within Bacterial Cellulose Membranes

BC membranes with standardized dimensions were sectioned and immersed in 10 mL of AgNO3 solutions at different concentrations (0.01, 0.0075, 0.005, 0.002, and 0.001 M) for 24 h to facilitate diffusion of Ag+ ions into the porous BC network and promote homogeneous precursor distribution.

After loading, the membranes were collected, excess AgNO3 was removed by pressing the membranes between two sheets of paper, and they were then immersed in 100 mL of either mint or avocado extract and incubated for an additional 24h. This step enabled biomolecules present in the extracts, e.g., phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and antioxidants, to reduce Ag+ ions within the BC matrix. A visible color change of the membranes, attributable to LSPR, served as an immediate indicator of AgNP formation.

Upon completion of synthesis, membranes were rinsed thoroughly with Milli-Q water to remove residual reagents and unbound silver ions, ensuring clean nanocomposite surfaces for downstream characterization and applications.

2.6. Characterization of AgNPs by UV–Visible Spectroscopy

The synthesized silver nanoparticles were characterized by UV–Visible (UV–Vis) absorption spectroscopy. Spectral data were collected in the 300–800 nm range using a multimode microplate reader (BioTek Synergy HTX), which employs a monochromator-based absorbance system capable of wavelength scanning in 1nm increments.

2.7. Strains Used for Antibacterial Activity Assays

To evaluate the antibacterial activity of BC membranes functionalized with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs),

Escherichia coli TOP10 (Invitrogen, USA) was used as the model organism. To facilitate visualization of bacterial colonies, a recombinant strain constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the

Ptet promoter [

34] was generated.

The genetic constructs were assembled using the BioBrick assembly method (Ginkgo Bioworks, USA) [

35]. The constructs were cloned into either the pSB1AK3 backbone (high-copy plasmid conferring ampicillin resistance). All transformations were performed using chemically competent cells, and the integrity of the genetic constructs was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Bacterial cultures were initiated from single colonies obtained from streaked glycerol stocks and inoculated into fresh Lysogeny Broth (LB) supplemented with ampicillin (35 µg mL−1; Sigma, USA). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24h. For long-term storage, bacterial strains were preserved at −80 °C in LB supplemented with 20% (v/v) glycerol.

2.8. Antibacterial Activity Assays of BC Membranes Functionalized with AgNPs

A series of assays were conducted to evaluate the antibacterial activity of BC–AgNP membranes under both solid-surface and liquid conditions. The first assay involved measuring the diameter of the bacterial growth inhibition zone on Petri dishes containing Lysogeny Broth (LB) solidified with 1% agar (LB agar) supplemented with ampicillin. For these assays, overnight E.coli:GFP cultures were prepared by inoculating single colonies obtained from streaked glycerol stocks into 5 mL of LB medium. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. Subsequently, 100 µL of culture was uniformly spread over the surface of an LB agar plate. Circular pieces of BC_AgNP membranes were placed at various positions on the plate surface, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24h.

The second assay was carried out in liquid culture. Circular BC–AgNP samples (4 mm in diameter) were introduced into 5 mL of LB medium, which was subsequently inoculated with E. coli:GFP from a single colony obtained from streaked glycerol stocks. A BC membrane without nanoparticles was used as a control. Cultures were incubated at 37 °C with orbital shaking at 200 rpm for 24h. After incubation, BC membranes were removed from the cultures. Subsequently, 1 µL from each culture was transferred into 5 mL of fresh LB medium and incubated again at 37 °C for 24h with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. The absorbance of the resulting cultures was measured at 660 nm.

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of Green-Synthesis Conditions for Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPS)

First, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized in liquid phase by reducing AgNO

3 at different concentrations using plant extracts from mint and avocado, following the procedures detailed in the Materials and Methods section. We evaluated synthesis efficiency as a function of AgNO

3 concentration, temperature, and pH. The liquid-phase reactions were monitored by the characteristic colour change of the reaction mixture, as shown in

Figure S1, which served as a preliminary qualitative indicator of AgNP nucleation.

Nanoparticle formation was further assessed by analyzing the LSPR band in the UV–Vis spectra. For metallic nanoparticles, this analysis not only confirms nanoparticle formation but also provides insight into variations in particle size distribution, morphology, and aggregation state [

36]. In particular, the position and shape of the LSPR maximum (λₘₐₓ) are strongly dependent on nanoparticle size and geometry: smaller nanoparticles typically exhibit a blue shift toward shorter wavelengths, whereas larger particles or aggregated species display a red shift toward longer wavelengths. Moreover, narrow and well-defined LSPR peaks are generally associated with small, spherical, and relatively monodisperse nanoparticles, while peak broadening or pronounced red shifts indicate increased particle size, anisotropy, and/or agglomeration.

This spectral characterization was performed using AgNPs synthesized under different temperature and pH conditions because temperature and pH are known to influence the reaction kinetics and physicochemical properties of nanoparticle formation.

Figures S2 and S3 present the UV–Vis spectra recorded for nanoparticles synthesized using avocado and mint extracts, respectively, at different AgNO

3 concentrations, namely 0.01 M, 0.0075 M, 0.005 M, 0.002 M, and 0.001 M. Syntheses were carried out at low temperature (4 °C), room temperature (23 °C), and elevated temperature (70 °C). Likewise, three pH values were considered: acidic (pH = 5), neutral (pH = 7), and basic (pH = 10). In all cases, plant-extract concentrations were held constant and AgNO

3 concentration was varied. The main characteristics of these UV–Vis spectra and their correlation with synthesis conditions (AgNO

3 concentration, temperature, and pH) were analyzed. As shown in

Figures S2 and S3, both synthesis efficiency and the spectral features of the synthesized nanoparticles depend on AgNO

3 concentration as well as temperature and pH.

AgNPs synthesis using either avocado or mint extracts was inefficient under acidic conditions, in some cases showing no detectable LSPR peak, indicating limited or absent AgNPs formation. Synthesis efficiency increased with pH, while both efficiency and nanoparticle characteristics were further modulated by temperature. At elevated temperature (70 °C), broader LSPR peaks were consistently observed, suggesting a wider particle-size distribution and/or increased aggregation.

Overall, neutral pH (pH 7) and moderate temperature (23 °C) provided the most favorable conditions, yielding higher and narrower LSPR peaks. Although higher temperatures enhanced reaction kinetics, they also led to broader LSPR peaks, whereas acidic conditions strongly suppressed nanoparticle formation. It is worth noting that differences between mint and avocado extracts were reflected in distinct UV–Vis spectral profiles, indicating extract- dependent effects on nanoparticle characteristics.

3.2. Functionalization of Bacterial Cellulose Membranes with Silver Nanoparticles.

Two different strategies were explored to functionalize BC membranes with AgNPs. The first strategy consisted of immersing BC membranes in a suspension containing pre-synthesized AgNPs, whereas the second strategy involved the in situ synthesis of AgNPs directly within the bacterial cellulose membrane.

For functionalization by immersion, BC membranes were submerged in solutions containing AgNPs previously synthesized using either mint or avocado extracts and maintained at 23 °C for 24 h. After immersion, the membranes were removed, excess liquid was drained, and each membrane was analyzed by UV–Vis spectroscopy.

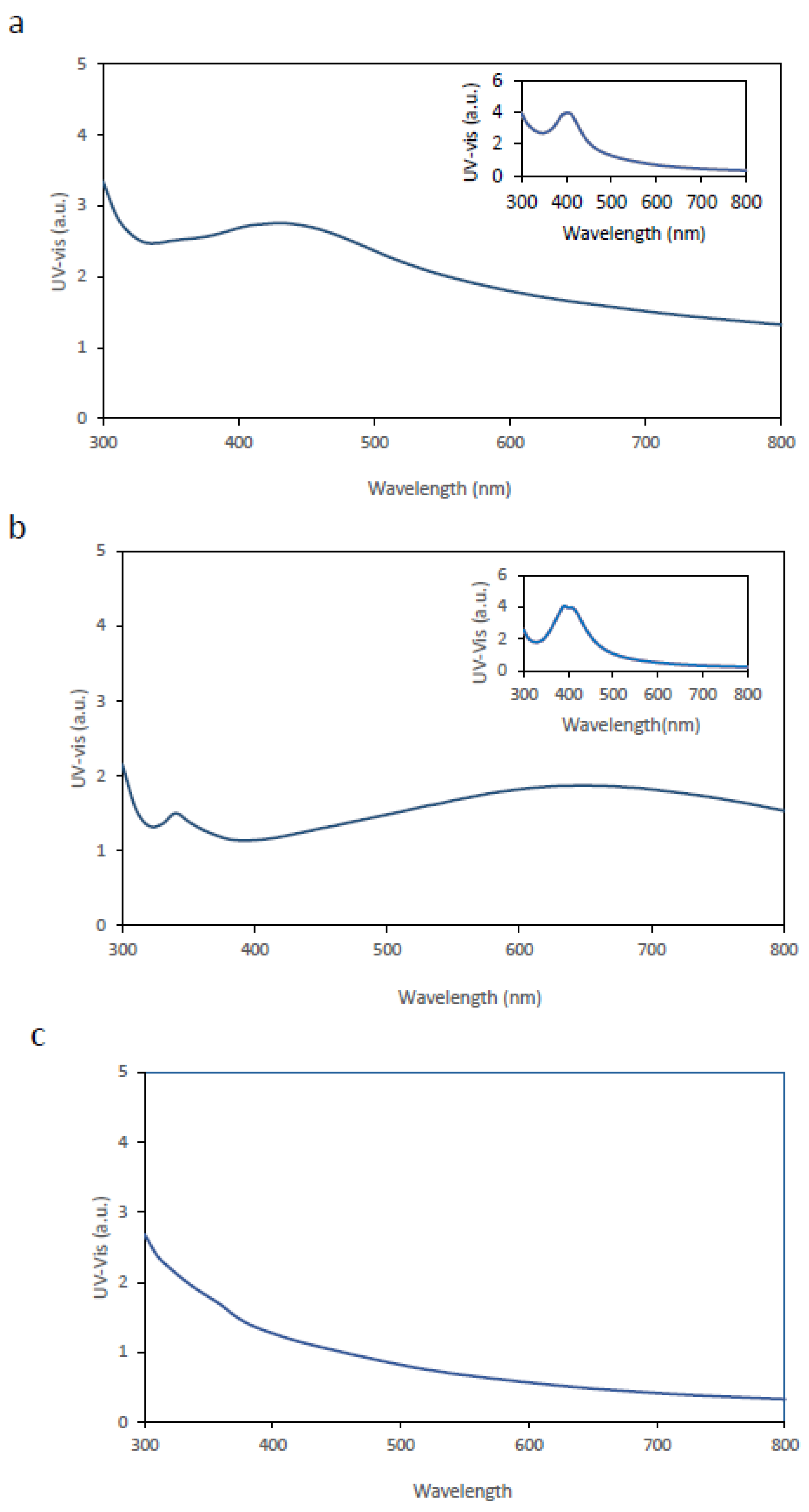

Figure 1a and

Figure 1b show the UV–Vis spectra of BC membranes loaded with AgNPs derived from avocado and mint extracts, respectively, while the inset panels display the spectra of the corresponding AgNPs in liquid suspension.

Comparison of the results indicates that, in both cases, there is a clear alteration in the UV–Vis spectral features of the AgNP-loaded BC membranes relative to the corresponding AgNP suspensions. Notably, neither BC membranes alone not contributed to the UV–Vis peak (

Figure 1c).

The observed changes in the UV–Vis spectra include a decrease in the amplitude of the maximum peak λₘₐₓ and a noticeable broadening of the peak relative to the liquid suspensions.

Several factors may account for these spectral changes. First, effective optical absorption may decrease due to limited AgNPs penetration into the BC membrane and reduced optical accessibility within the fibrous BC matrix, resulting in a diminished peak height. Second, the BC matrix introduces a heterogeneous dielectric environment distinct from the aqueous medium. The proximity of cellulose fibers and confined regions can alter the local refractive index, potentially contributing to peak shifts and amplitude changes. Third, although nanoparticles were initially dispersed, immersion within the membrane may promote nanoparticle– nanoparticle interactions, partial aggregation, or plasmon coupling between adjacent nanoparticles, thereby broadening the distribution of inter-particle distances and leading to band broadening. Finally, the membrane structure may introduce additional optical scattering due to reflection, diffraction, and irregular light paths through the BC network, further contributing to spectral broadening [

37,

38,

39].

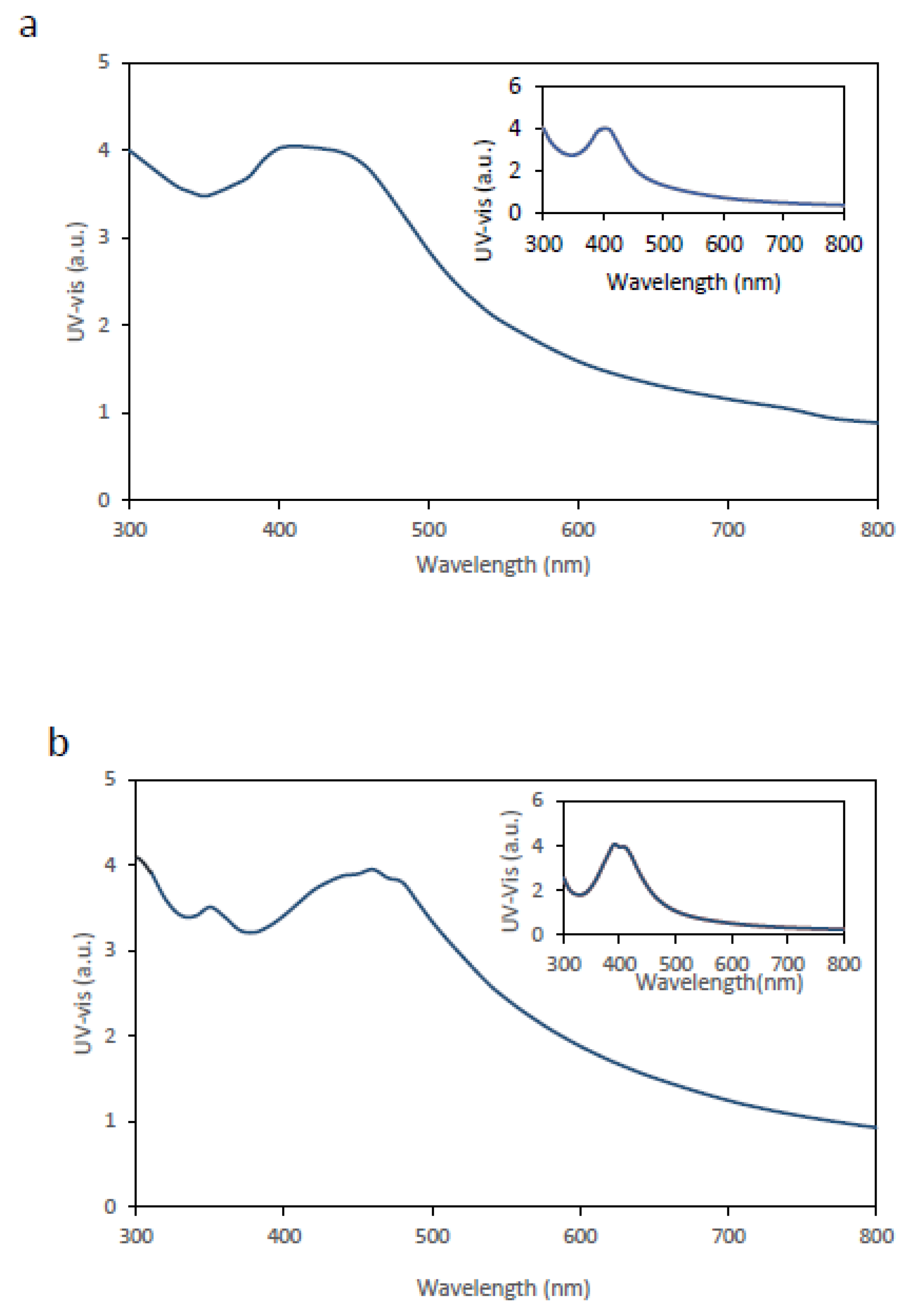

The second approach involved the in situ synthesis of AgNPs directly within the BC membrane (see Materials and Methods for details), and the resulting membranes were characterized by UV–Vis spectroscopy.

Figure 2 shows the corresponding UV–Vis spectra. In both

Figure 2a (avocado extract) and

Figure 2b (mint extract), a clear improvement in the spectral response is observed, evidenced by increased peak intensity and improved definition of the λₘₐₓ peak compared with membranes obtained by immersion. The inset panels display the spectra corresponding to AgNP synthesis in the liquid phase.

For both avocado- and mint-mediated syntheses, the UV–Vis spectra obtained from in situ– functionalised BC membranes more closely resemble those of liquid AgNPs suspensions than the spectra obtained from BC membranes functionalised by immersion. Although the membranes exhibit peak intensities broadly comparable to those of AgNPs synthesised in liquid suspension, a discernible red shift of the λₘₐₓ peak, together with band broadening, is observed. These spectral features are consistent with the mechanisms discussed above. When compared with BC membranes functionalized by immersion, the in situ–functionalized membranes display a higher λₘₐₓ peak amplitude, suggesting a higher density of AgNPs within the BC matrix, as well as a comparatively narrower UV–Vis spectral profile.

Overall, these results indicate that in situ synthesis of AgNPs within BC membranes is a more efficient strategy than liquid-phase synthesis followed by nanoparticle adsorption or uptake into the membrane.

3.3. Analysis of the Antibacterial Activity of BC Membranes Functionalized with AgNPs.

Next, the antibacterial efficacy of bacterial cellulose membranes functionalized with silver nanoparticles (BC–AgNPs) was investigated. Escherichia coli TOP10 constitutively expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (E. coli:GFP) was used as the model organism.

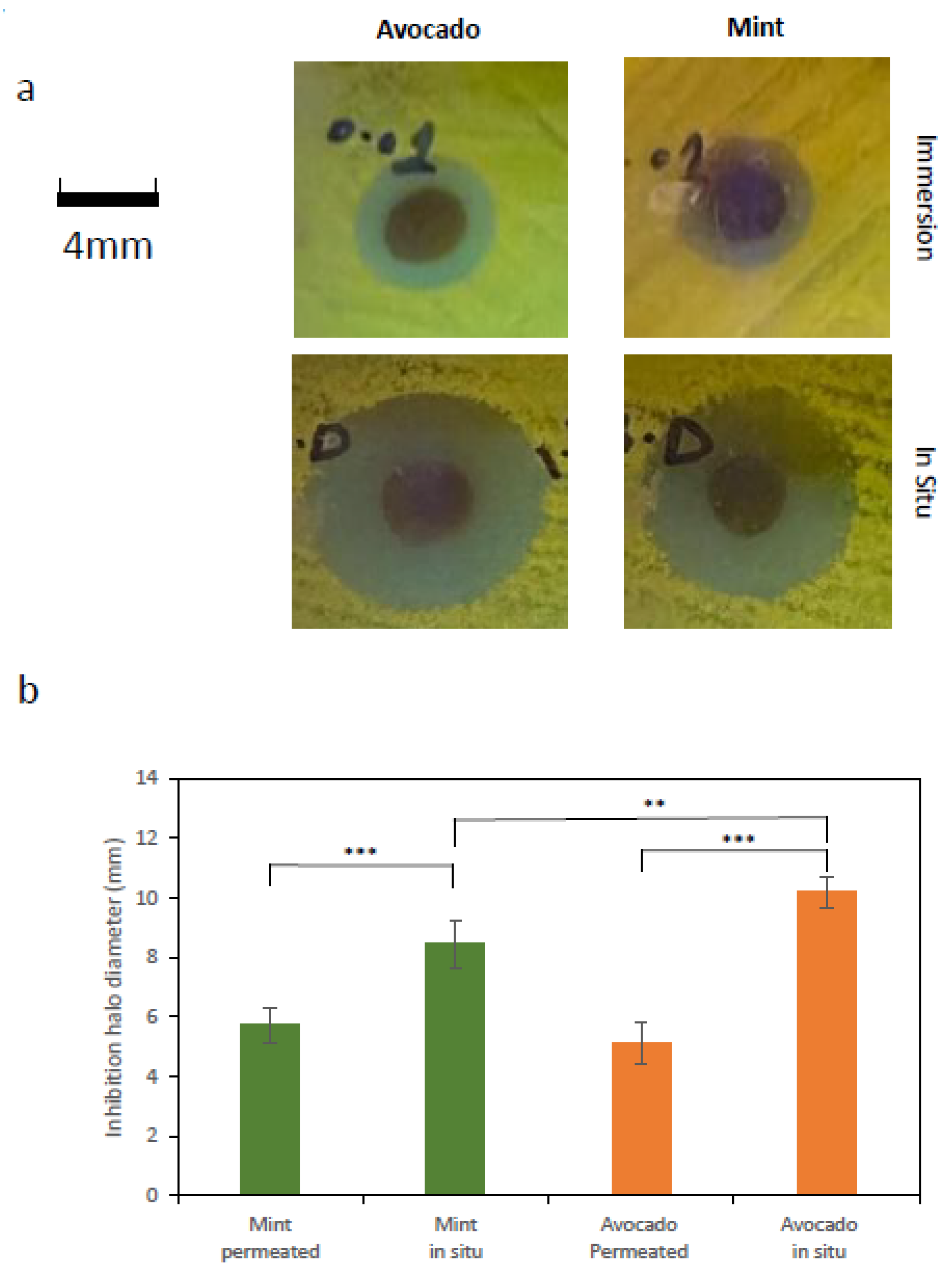

A series of assays were conducted to evaluate antimicrobial performance. In the first assay, the diameter of the bacterial growth inhibition zone was measured on Petri dishes containing a uniformly distributed E. coli:GFP lawn, onto which circular BC–AgNP membranes (4mm in diameter) were placed.

The bacterial growth-inhibition capacity of membrane pieces functionalized either by immersion or by in situ AgNP synthesis was assessed. Inhibitory efficiency was quantified by measuring the diameter of the inhibition zones observed on the agar plates. For illustrative purposes,

Figure 3a shows representative images of characteristic inhibition zones generated by BC–AgNP membranes prepared using avocado and mint extracts for nanoparticle synthesis. The image shows a clear difference in the size of the inhibition zones generated by membranes functionalized by immersion, which are markedly smaller than those corresponding to membranes functionalized via in situ AgNPs synthesis. This comparison clearly demonstrates that the latter approach produces membranes that are substantially more effective in terms of antibacterial activity.

Figure 3b reports the inhibition zone diameters under the different tested conditions. As shown, antibacterial efficiency was consistently higher for membranes functionalized via in situ synthesis, regardless of whether mint or avocado extract was used.

Notably, a statistically significant difference was also observed in the size of the inhibition areas produced by BC–AgNPs synthesized in situ using avocado extract compared with those synthesized using mint extract, with avocado-extract-derived BC–AgNPs exhibiting higher antibacterial efficiency (Welch’s t-test, p < 0.005).

Subsequently, the bactericidal activity of the nanoparticles was evaluated. To this end, two different assays were performed using BC–AgNP membranes functionalized via in situ synthesis with either avocado or mint extracts, as these formulations showed the highest performance in the previous assays.

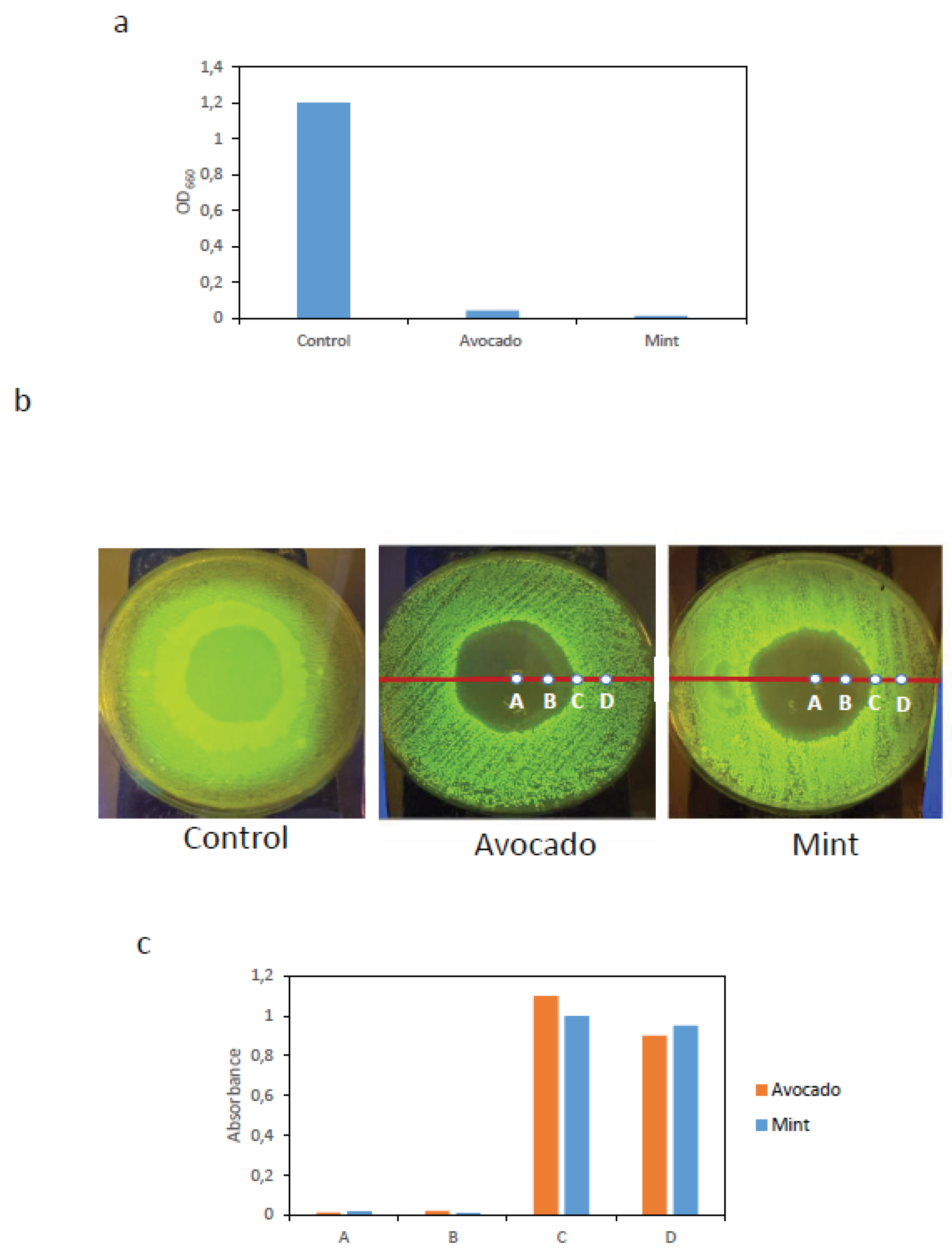

The first assay was carried out in liquid culture, in which circular BC–AgNP simples (4mm in diameter) were introduced into

E. coli:GFP cultures. After incubation, the absorbance of the resulting cultures was measured at 660 nm.

Figure 4a shows that significant bacterial growth was observed only in the control culture, whereas no growth was detected in cultures exposed to BC–AgNP membranes, indicating that these membranes exhibit strong bactericidal activity.

The second assay was performed on solid surfaces. Circular BC–AgNP membranes (30 mm in diameter), synthesized in situ using either avocado or mint extracts, were placed onto LB agar plates previously inoculated with a uniformly spread E.coli:GFP liquid culture. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24h. A BC membrane without nanoparticles was used as a control.

After incubation, the membranes were removed, and clear zones with no observable bacterial growth were evident upon transillumination of the plates. In contrast, the control condition exhibited GFP fluorescence across the entire plate surface.

Figure 4b shows representative images highlighting areas lacking detectable bacterial growth. Starting from the center of the growth inhibition zone, surface samples were collected at four positions (points A, B, C, and D in

Figure 4b). Each sample was transferred to 5 mL of LB medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with orbital shaking at 200 rpm. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 660 nm.

As shown in

Figure 4c, samples collected from points A and B, located within the zone where no bacterial growth was observed, exhibited very low absorbance values, indicating the absence of bacterial growth in liquid culture. In contrast, samples from points C and D showed high absorbance values, indicating clear bacterial growth. These results, consistent with the previous assay, further confirm the strong bactericidal activity of the BC–AgNP membranes.

4. Discussion

The results presented in this work highlight the strong interdependence between synthesis conditions, nanoparticle incorporation strategy, and the resulting antibacterial performance of bacterial cellulose (BC) membranes functionalized with silver nanoparticles obtained via green synthesis. Liquid-phase synthesis experiments clearly demonstrated that the formation and quality of AgNPs obtained using avocado and mint extracts are highly sensitive to both pH and temperature. Increases in temperature accelerate nanoparticle formation by enhancing reaction kinetics, while extreme pH values can modify reduction pathways, influence nucleation and growth processes, and compromise colloidal stability, ultimately affecting particle size, morphology, and dispersion [

30,

40,

41].

Neutral pH (pH 7) and moderate temperature (23 °C) emerged as optimal conditions, yielding well-defined and relatively narrow LSPR bands in UV–Vis spectra. Such spectral features are indicative of efficient nanoparticle formation with a comparatively narrow size distribution.

In contrast, acidic conditions markedly hindered nanoparticle formation, likely due to protonation of functional groups in phytochemicals, such as phenolics and carboxylates, which diminishes their ability to act as effective reducing and capping agents, in agreement with previously reported results [

37]. At elevated temperatures, although reaction kinetics are accelerated, the appearance of broader LSPR peaks suggests less controlled growth, increased polydispersity, and/or aggregation, consistent with thermal destabilization of capping interactions.

A central outcome of this study is the comparison between two distinct membrane functionalization strategies: immersion of BC membranes in pre-formed AgNP suspensions and in situ synthesis of AgNPs within the BC matrix. The immersion approach resulted in UV–Vis spectra with lower peak intensity and pronounced band broadening compared with the corresponding liquid-phase suspensions. These effects can be attributed to several factors, including limited nanoparticle penetration into the dense regions of the BC network, heterogeneous optical environments within the fibrous scaffold, and potential aggregation or plasmon coupling induced by confinement within the matrix. Furthermore, adsorption of pre- formed nanoparticles onto the BC surface is likely governed by relatively weak interactions, which may lead to non-uniform distribution and reduced effective nanoparticle loading.

By contrast, in situ synthesis within the BC membranes consistently produced stronger and more clearly defined LSPR features, indicating more efficient nanoparticle incorporation and a more homogeneous spatial distribution throughout the BC scaffold. In this approach, Ag+ ions first diffuse into the porous BC network and are subsequently reduced by plant extracts, allowing nucleation and growth to occur directly within the matrix and promoting intimate matrix– nanoparticle interactions. Although the in situ–synthesized membranes still exhibited red shifts and some band broadening relative to liquid-phase synthesis, an expected consequence of differences in local refractive index, confinement effects, and possible interparticle interactions, the overall spectral quality and intensity were markedly improved compared with the immersion strategy. These observations underscore the importance of synthesis location and sequence in determining the final nanocomposite structure.

The antibacterial assays provide strong functional validation of these physicochemical findings. BC–AgNP membranes prepared via in situ synthesis showed consistently higher antibacterial efficacy against E. coli than membranes functionalized by immersion, as evidenced by larger inhibition halos on solid media. Importantly, additional experiments designed to probe the nature of the antibacterial effect demonstrated that the observed inhibition was bactericidal rather than merely bacteriostatic. In liquid-culture assays, no bacterial regrowth was detected after removal of the BC–AgNP membranes and transfer of the culture to fresh medium. Similarly, surface sampling from within inhibition zones on agar plates yielded no detectable bacterial growth upon re-culturing, whereas samples collected outside the inhibition zones showed robust growth. Collectively, these results provide compelling evidence that BC–AgNP membranes induce irreversible bacterial damage under the tested conditions.

The enhanced bactericidal performance of in situ–functionalized membranes can be rationalized by improved nanoparticle availability and sustained local exposure to silver species at the membrane–bacteria interface. Immobilization of AgNPs within the BC network may facilitate controlled release and prolonged contact with bacterial cells, thereby enhancing well- established antimicrobial mechanisms such as membrane disruption, oxidative stress generation, and interference with essential cellular components. Although silver release kinetics and reactive oxygen species were not directly quantified in this study, the consistent bactericidal outcomes strongly suggest that the BC scaffold plays an active role in modulating nanoparticle– bacteria interactions.

Finally, the use of mint and avocado extracts highlights the flexibility of plant-based green synthesis routes for the production of functional nanocomposites. While both extracts successfully supported AgNPs formation, differences observed in UV–Vis spectral features indicate that variations in phytochemical composition influence reduction kinetics, nanoparticle stabilization, and final particle characteristics. Notably, membranes synthesized using avocado extract exhibited superior antibacterial activity. This observation emphasizes the need for careful selection and standardization of plant extracts in green synthesis protocols to ensure reproducibility and predictable material performance.

Overall, the findings of this study demonstrate that combining bacterial cellulose with in situ green synthesis of silver nanoparticles yields nanocomposite membranes with enhanced nanoparticle incorporation and robust bactericidal activity. These results reinforce the value of in situ functionalization strategies and green chemistry approaches for the development of sustainable, high-performance antimicrobial materials, and provide a solid foundation for future studies aimed at further optimizing structure–function relationships in BC–AgNP systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: TubescontainingAgNO3andmintoravocadoextractsweremixed.; Figure S2: UV–Visspectraofsilvernanoparticle(AgNP)synthesisinliquidphaseobtainedbycombiningdifferentAgNO3concentrationswiththesamevolumeofavocadoextract.; Figure S3: UV–Visspectraofsilvernanoparticle(AgNP)synthesisinliquidphaseobtainedbycombiningdifferentAgNO3concentrationswiththesamevolumeofmintextract.

Author Contributions

Experiments were designed by GNA., MP. and JM. GNA did the experiments. JM. GNA and MP. wrote the paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Plasmids and strains used in this study and other materials are available upon request to authors. Correspondence and requests for data should be addressed to J.M. (javier.macia@upf.edu).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members of the Synthetic Biology for Biomedical Applications Lab for fruitful conversations. Funding for this study and for the open access charge was in the form of grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [PID2023-151156NB- I00/MICIUN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE]. This work was supported by “Unidad de Excelencia María de Maeztu” CEX2024-001431-M, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baig N, Kammakakam I, Falath W, Kammakakam I. Nanomaterials: A review of synthesis methods, properties, recent progress, and challenges. Vol. 2, Materials Advances. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2021. p. 1821–71. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah M, Obayedullah M, Shariful Islam Shuvo M, Abul Khair M, Hossain D, Nahidul Islam M. A review on multifunctional applications of nanoparticles: Analyzing their multi-physical properties. Vol. 21, Results in Surfaces and Interfaces. Elsevier B.V.; 2025. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse S, Hailemariam T. A Review on the Classification, Characterisation, Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Their Application. Advances. 2025 Jun 23;6(2):63–72. [CrossRef]

- Jangid H, Singh S, Kashyap P, Singh A, Kumar G. Advancing biomedical applications: an in-depth analysis of silver nanoparticles in antimicrobial, anticancer, and wound healing roles. Vol. 15, Frontiers in Pharmacology. Frontiers Media SA; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Meher A, Tandi A, Moharana S, Chakroborty S, Mohapatra SS, Mondal A, et al. Silver nanoparticle for biomedical applications: A review. Vol. 6, Hybrid Advances. Elsevier B.V.; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Burdușel AC, Gherasim O, Grumezescu AM, Mogoantă L, Ficai A, Andronescu E. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: An up-to-date overview. Vol. 8, Nanomaterials. MDPI AG; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan PD, Banas D, Durai RD, Kabanov D, Hosnedlova B, Kepinska M, et al. Silver nanomaterials for wound dressing applications. Vol. 12, Pharmaceutics. MDPI AG; 2020. p. 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Nicolae-Maranciuc A, Chicea D. Polymeric Systems as Hydrogels and Membranes Containing Silver Nanoparticles for Biomedical and Food Applications: Recent Approaches and Perspectives. Vol. 11, Gels. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025. [CrossRef]

- Dube E, Okuthe GE. Silver Nanoparticle-Based Antimicrobial Coatings: Sustainable Strategies for Microbial Contamination Control. Vol. 16, Microbiology Research. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025. [CrossRef]

- Yu Y, Zhou Z, Huang G, Cheng H, Han L, Zhao S, et al. Purifying water with silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)-incorporated membranes: Recent advancements and critical challenges. Vol. 222, Water Research. Elsevier Ltd.; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Okur EE, Eker F, Akdaşçi E, Bechelany M, Karav S. Comprehensive Review of Silver Nanoparticles in Food Packaging Applications. Vol. 26, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shah MA, Pirzada BM, Price G, Shibiru AL, Qurashi A. Applications of nanotechnology in smart textile industry: A critical review. J Adv Res. 2022 May;38:55–75. [CrossRef]

- Saxena R, Kotnala S, Bhatt SC, Uniyal M, Rawat BS, Negi P, et al. A review on green synthesis of nanoparticles toward sustainable environment. Sustainable Chemistry for Climate Action. 2025 Jun;6:100071. [CrossRef]

- Fahim M, Shahzaib A, Nishat N, Jahan A, Bhat TA, Inam A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: A comprehensive review of methods, influencing factors, and applications. Vol. 16, JCIS Open. Elsevier B.V.; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Elmehalawy NG, Zaky MMM, Eid AM, Fouda A. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles: multifaceted antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, and antimicrobial activities. Sci Rep. 2025 Dec 1;15(1). [CrossRef]

- Martirani-VonAbercron SM, Pacheco-Sánchez D. Bacterial cellulose: A highly versatile nanomaterial. Vol. 16, Microbial Biotechnology. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; 2023. p. 1174–8. [CrossRef]

- Mecha AC, Chollom MN, Babatunde BF, Tetteh EK, Rathilal S. Versatile Silver- Nanoparticle-Impregnated Membranes for Water Treatment: A Review. Vol. 13, Membranes. MDPI; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Homayoonfal M, Mehrnia MR, Mojtahedi YM, Ismail AF. Effect of metal and metal oxide nanoparticle impregnation route on structure and liquid filtration performance of polymeric nanocomposite membranes: A comprehensive review. Desalination Water Treat. 2013;51(16–18):3295–316. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Zheng Y, Song W, Luan J, Wen X, Wu Z, et al. In situ synthesis of silver- nanoparticles/bacterial cellulose composites for slow-released antimicrobial wound dressing. Carbohydr Polym. 2014 Feb 15;102(1):762–71. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed S, Saifullah, Ahmad M, Swami BL, Ikram S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica aqueous leaf extract. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2016 Jan;9(1):1–7.

- Singh SR, Akshatha SJ, Abbigeri MB, Padti AC, Bhavi SM, Kulkarni SR, et al. Eco- synthesized silver nanoparticles from Curcuma longa leaves: Phytochemical and biomedical applications. Next Nanotechnology. 2025 Jan 1;8.

- Bindhu MR, Umadevi M, Esmail GA, Al-Dhabi NA, Arasu MV. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Moringa oleifera flower and assessment of antimicrobial and sensing properties. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2020 Apr 1;205. [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi S, Fatima S, Ul Ain Q, Shafiq Z, Janjua MRSA. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (SNPs) using plant extracts: A multifaceted approach in photocatalysis, environmental remediation, and biomedicine. Vol. 15, RSC Advances. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2025. p. 3858–903.

- Velgosova O, Dolinská S, Podolská H, Mačák L, Čižmárová E. Impact of Plant Extract Phytochemicals on the Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Materials. 2024 May 1;17(10). [CrossRef]

- Ryngajłło M, Jędrzejczak-Krzepkowska M, Kubiak K, Ludwicka K, Bielecki S. Towards control of cellulose biosynthesis by Komagataeibacter using systems-level and strain engineering strategies: current progress and perspectives. [CrossRef]

- Said Azmi SNN, Samsu Z ’Asyiqin, Mohd Asnawi ASF, Ariffin H, Syed Abdullah SS. The production and characterization of bacterial cellulose pellicles obtained from oil palm frond juice and their conversion to nanofibrillated cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications. 2023 Jun;5:100327.

- Gabriela ÁM, Gabriela M de OV, Luis AM, Reinaldo PR, Michael HM, Rodolfo GP, et al. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Mint Leaf Extract ( Mentha piperita ) and Their Antibacterial Activity. Adv Sci Eng Med. 2017 Nov 7;9(11):914–23. [CrossRef]

- Htwe YZN, Chow WS, Suda Y, Mariatti M. Effect of Silver Nitrate Concentration on the Production of Silver Nanoparticles by Green Method. Mater Today Proc. 2019;17:568– 73. [CrossRef]

- Kim HY, Rho WY, Lee HY, Park YS, Suh JS. Aggregation effect of silver nanoparticles on the energy conversion efficiency of the surface plasmon-enhanced dye-sensitized solar cells. Solar Energy. 2014 Nov 1;109(1):61–9. [CrossRef]

- Bélteky P, Rónavári A, Igaz N, Szerencsés B, Tóth IY, Pfeiffer I, et al. Silver nanoparticles: Aggregation behavior in biorelevant conditions and its impact on biological activity. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:667–87. [CrossRef]

- Kim HY, Rho WY, Lee HY, Park YS, Suh JS. Aggregation effect of silver nanoparticles on the energy conversion efficiency of the surface plasmon-enhanced dye-sensitized solar cells. Solar Energy. 2014 Nov 1;109(1):61–9. [CrossRef]

- Prathna TC, Chandrasekaran N, Mukherjee A. Studies on aggregation behaviour of silver nanoparticles in aqueous matrices: Effect of surface functionalization and matrix composition. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2011 Oct 20;390(1–3):216–24. [CrossRef]

- Kelly KL, Coronado E, Zhao LL, Schatz GC. The optical properties of metal nanoparticles: The influence of size, shape, and dielectric environment. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2003 Jan 23;107(3):668–77.

- Bertram R, Neumann B, Schuster CF. Status quo of tet regulation in bacteria. Microb Biotechnol. 2022 Apr 29;15(4):1101–19. [CrossRef]

- Shetty R, Lizarazo M, Rettberg R, Knight TF. Assembly of BioBrick Standard Biological Parts Using Three Antibiotic Assembly. In 2011. p. 311–26.

- Conti G. Comprehensive insights into UV-Vis spectroscopy for the characterization and optical properties analysis of plasmonic metal nanoparticles. Journal of Nanomaterials and Devices. 2025; [CrossRef]

- Kinnan MK, Chumanov G. Plasmon coupling in two-dimensional arrays of silver nanoparticles: II. Effect of the particle size and interparticle distance. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2010 Apr 29;114(16):7496–501. [CrossRef]

- Murray WA, Auguié B, Barnes WL. Sensitivity of localized surface plasmon resonances to bulk and local changes in the optical environment. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2009 Apr 2;113(13):5120–5. [CrossRef]

- Tam F, Moran C, Halas N. Geometrical parameters controlling sensitivity of nanoshell plasmon resonances to changes in dielectric environment. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2004 Nov 11;108(45):17290–4. [CrossRef]

- Velgosova O, Mačák L, Lisnichuk M, Varga P. Influence of pH and Temperature on the Synthesis and Stability of Biologically Synthesized AgNPs. Applied Nano [Internet]. 2025 Oct 10;6(4):22. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-3501/6/4/22. [CrossRef]

- Jiang XC, Chen WM, Chen CY, Xiong SX, Yu AB. Role of Temperature in the Growth of Silver Nanoparticles Through a Synergetic Reduction Approach. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6(1):1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).