Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

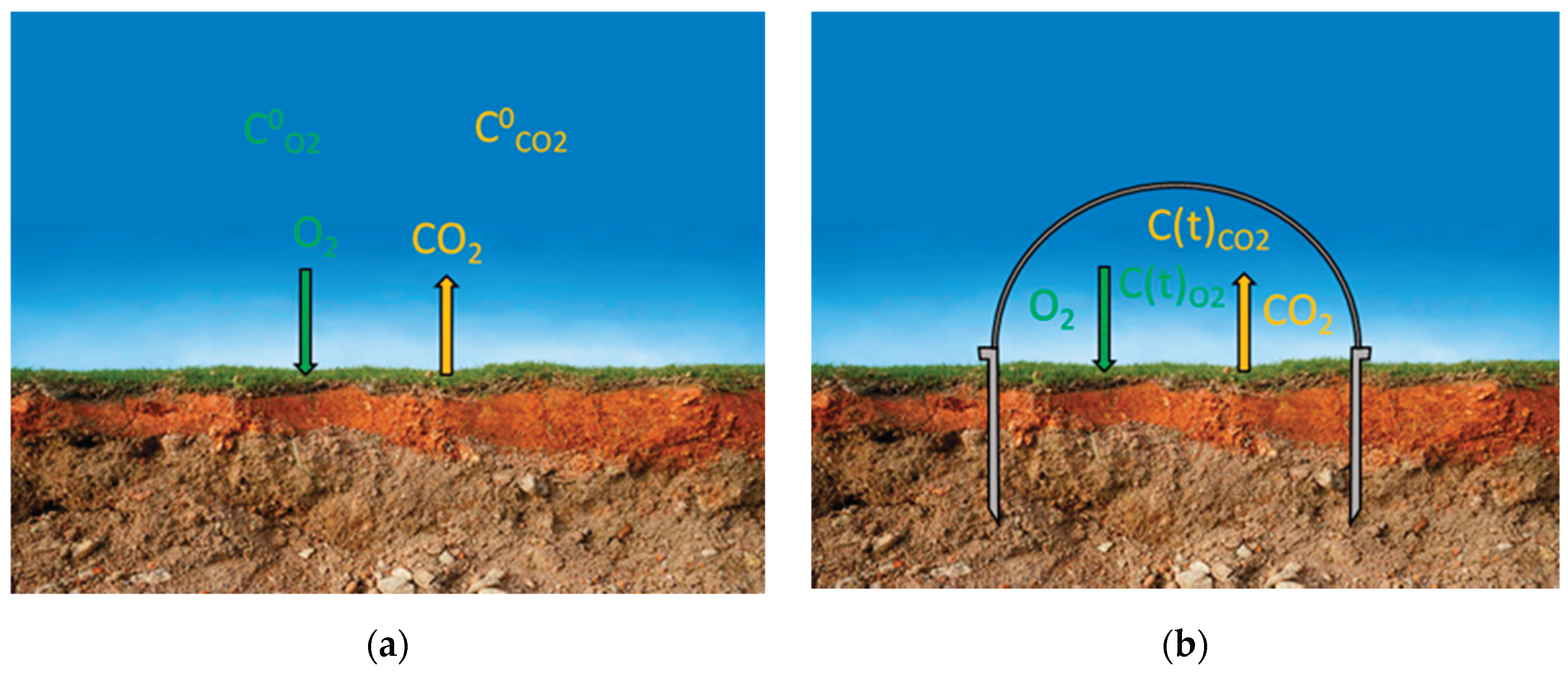

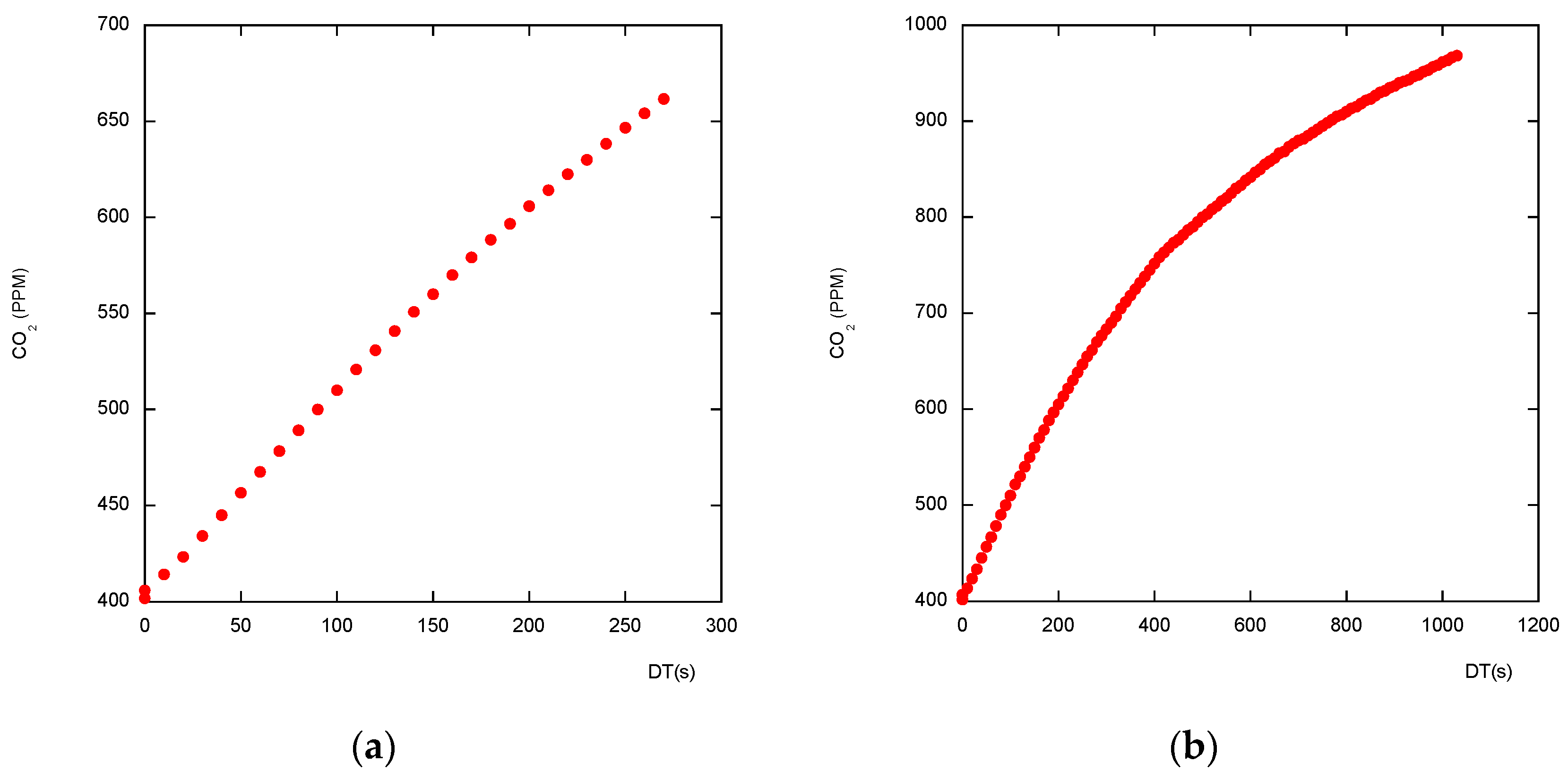

2.1. Closed Accumulation Chambers Technique Principles

2.1.1. Pros and Cons of the Closed Chambers Technique

2.1.2. DIY Philosophy

2.2. Automatic SAGE Chambers

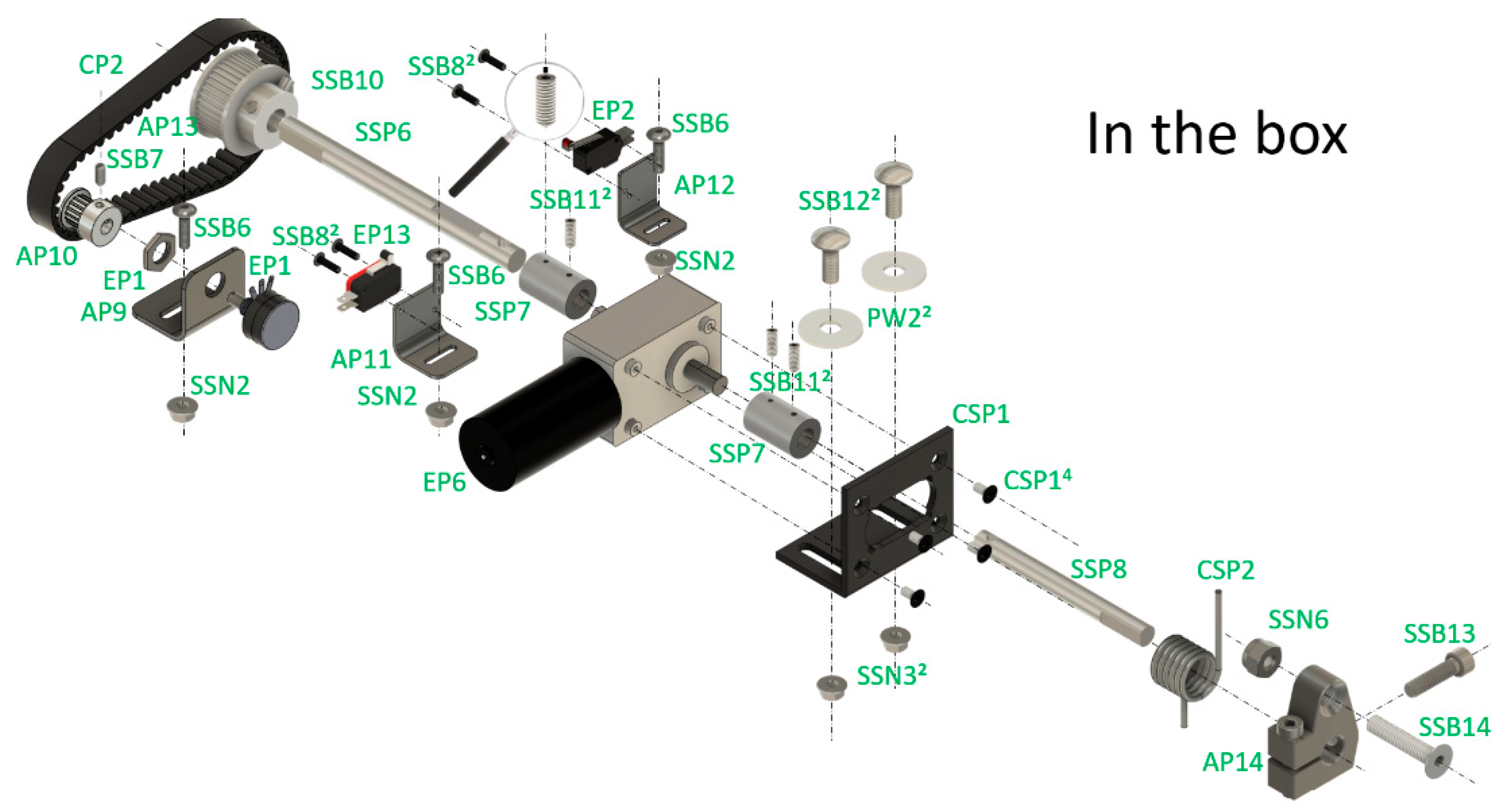

2.2.1. Chambers’ Design

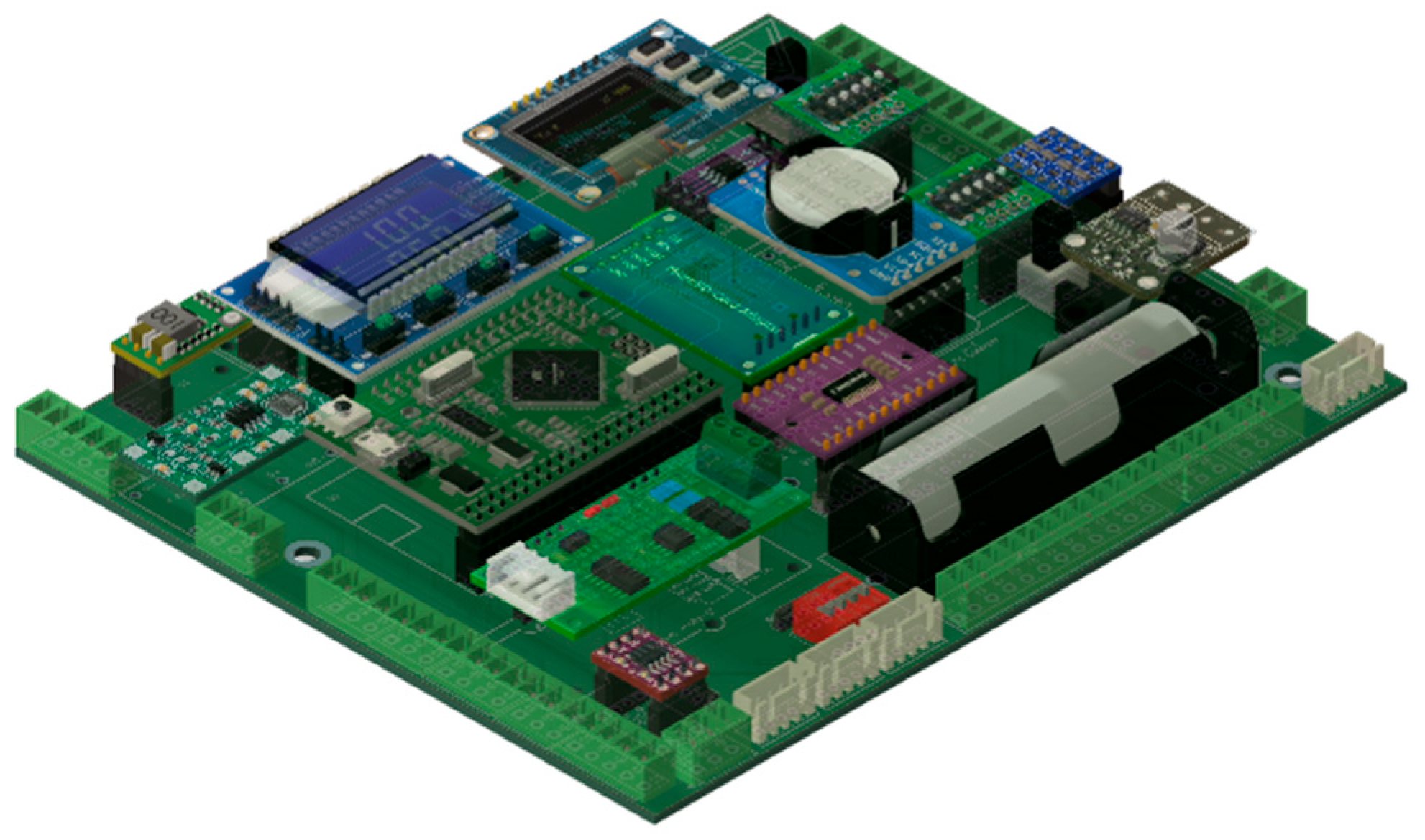

2.2.2. Electronic and Mechanical Construction of SAGE Chambers

- The used microcontroller is a Mega Pro Mini programmable using C and C++ under Arduino IDE, fully compatible with Arduino Mega 2560.

- To be able to use a 24V power line, there are two dc-dc step-down modules. The first module, used only if a 24V power line is actually used, delivers 12V for the motor and, eventually, some sensors, such as the soil water content probe, through a Solid-State Relay (SSR) to be able to cut down the sensors' power line and to save some energy when they are not used. This DC-DC is replaced by a jumper if the used power line is a 12V. The second DC-DC step-down delivers 5V to recharge an internal security battery, to power the microcontroller and all other modules, including the sensors, through another SSR.

- The air homogenization fan is Pule Wide Modulation (PWM) controlled, with an embedded tachometer (4-wire fan) to precisely control its speed of rotation, which is checked and recorded. For a transparent cloche, this fan is also transparent. PWM control is useful for changing fan rotation speed and adapting it to external wind conditions or other factors. This part of the measurement condition adaptations for CO2 efflux is under test and will be described later. For evaporation measurement, because a closed chamber is also able to measure surface evaporation, the wind influence was already corrected and described [10]

- A PWM generator piloted by the microcontroller is implemented on the main board to achieve Fan speed control.

- The embedded OLED display allows for the showing of some info when required. The keys on the OLED module allow interaction with the microcontroller and, consequently, allow several pages and options to be displayed. This display should be cleared when not used to save some energy. The embedded microcontroller is able to manage it.

- Inside the chamber main box, there is an internal battery along with an Uninterrupted Power Supply (UPS). When the main power is available, the battery is recharged. This battery serves to power the microcontroller and the SD card module in case of a main power shortage, allowing it to stop any actions waiting for the power to be restored. It is a security device preventing SD card corruption held directly by an SD card module, deported in an easy-to-access holder plugged with a ribbon cable to the SD module.

- Two LC filters to limit the DC-DC step-down module and motor noise.

- A Real Time Clock module (DS3231-based) is used to hold the current date and time.

- Two delayed switches, along with a motor pilot (DRV8871 H Bridge-based), help to open or close the chamber when triggered by the microcontroller.

- A logic level shift is used between the microcontroller (5V logic level) and the Luminox sensor (3.3V logic level), even if it is not strictly necessary, as Luminox is 5V logic level tolerant and the microcontroller “understands” 3.3V logic level UART inputs. This logic level shifter is also used to reserve one I²C line from the multiplexer (see further text) for a 3.3V logic level.

- A communication module allows the use of RS-485 or another module, RS-422, for long-distance communication. There is also a reserved place and a connector for the LoRa WAN module. However, we kept in mind that LoRa allows a long-range radio communication of low-density data, so the chambers’ raw data cannot be transmitted. However, the internally computed fluxes can be.

- An I²C line multiplexer is added to allow for multiple I²C devices to be used and to add several optional I²C devices without worrying about possible I²C address conflicts. Additionally, most I²C communication-based modules typically have their own pull-up resistors. Then, if there are too many modules on the same line, the resulting Pull-up resistors are too weak. In other words, it is necessary to separate the I²C modules even if there is no address conflict.

- Because the under-cloche sensors are I²C and because this communication bus is not designed for long wires, A switch and connectors are placed on the main board to implement an optional I²C expander module based on the PB2B715 chip. This module allows the use of longer wires between the main board and the under-cloche board with sensors. However, with the high-quality wires we are using, our chambers do not require the I²C expander use.

- As the optional GPS uses the SERIAL0 UART line of the microcontroller, when the GPS is used, and the microcontroller is booting (may be booted by the watchdog), a blockage may occur. To solve this problem, a magnetic isolator based on ADUM1201 is inserted on the SERIAL0 line between the microcontroller and the GPS connector. This isolator is powered by the microcontroller, and when booting, the microcontroller is not powering it, setting the SERIAL0 line as disconnected. There is no more blocking possibility.

- Finally, a DIP switch block (4 Pin) is used for address indication, allowing 16 hard-coded unique addresses. Indeed, each chamber has its own address.

2.2.3. Pricing

2.2.4. Options and Possible Configurations

-

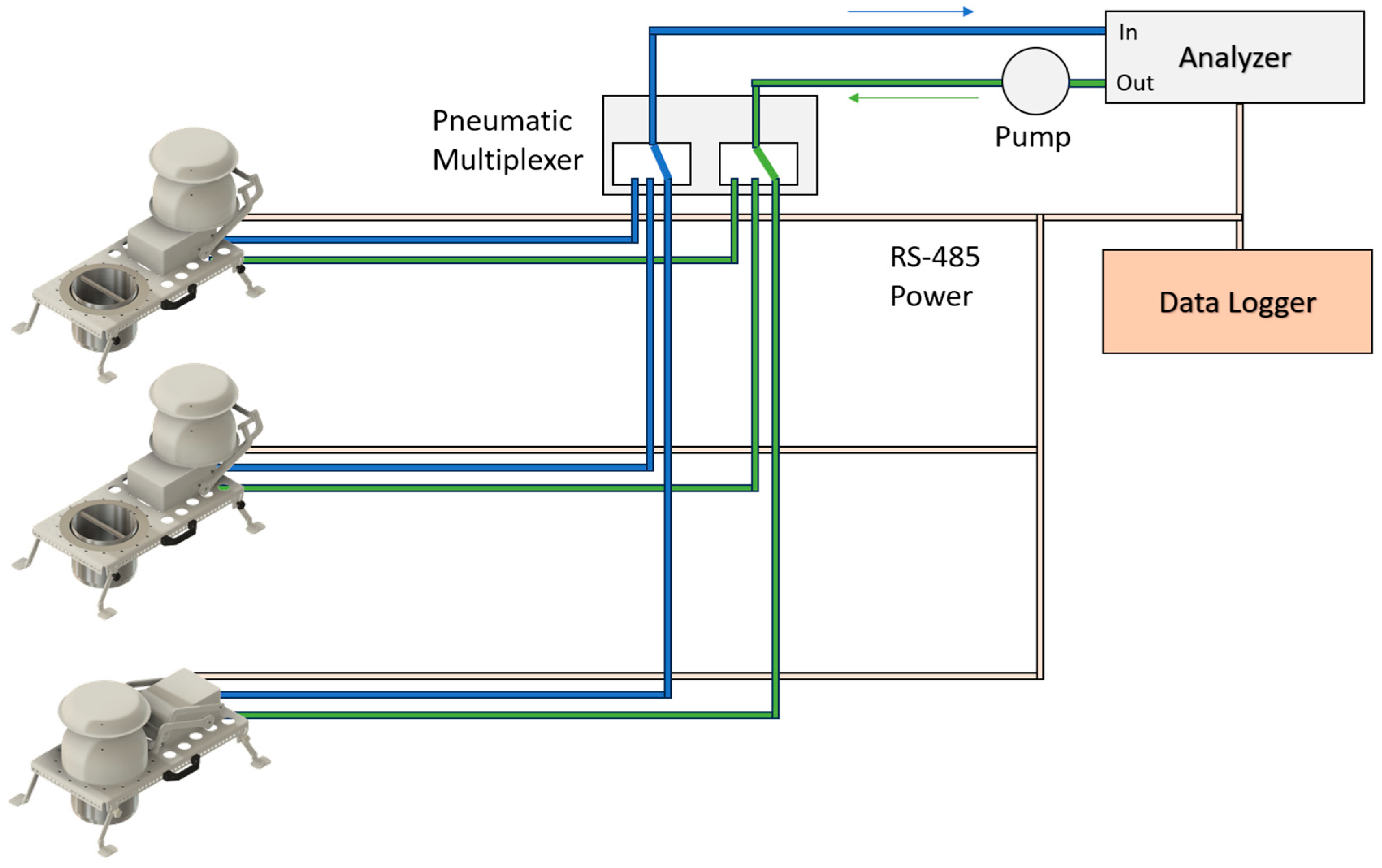

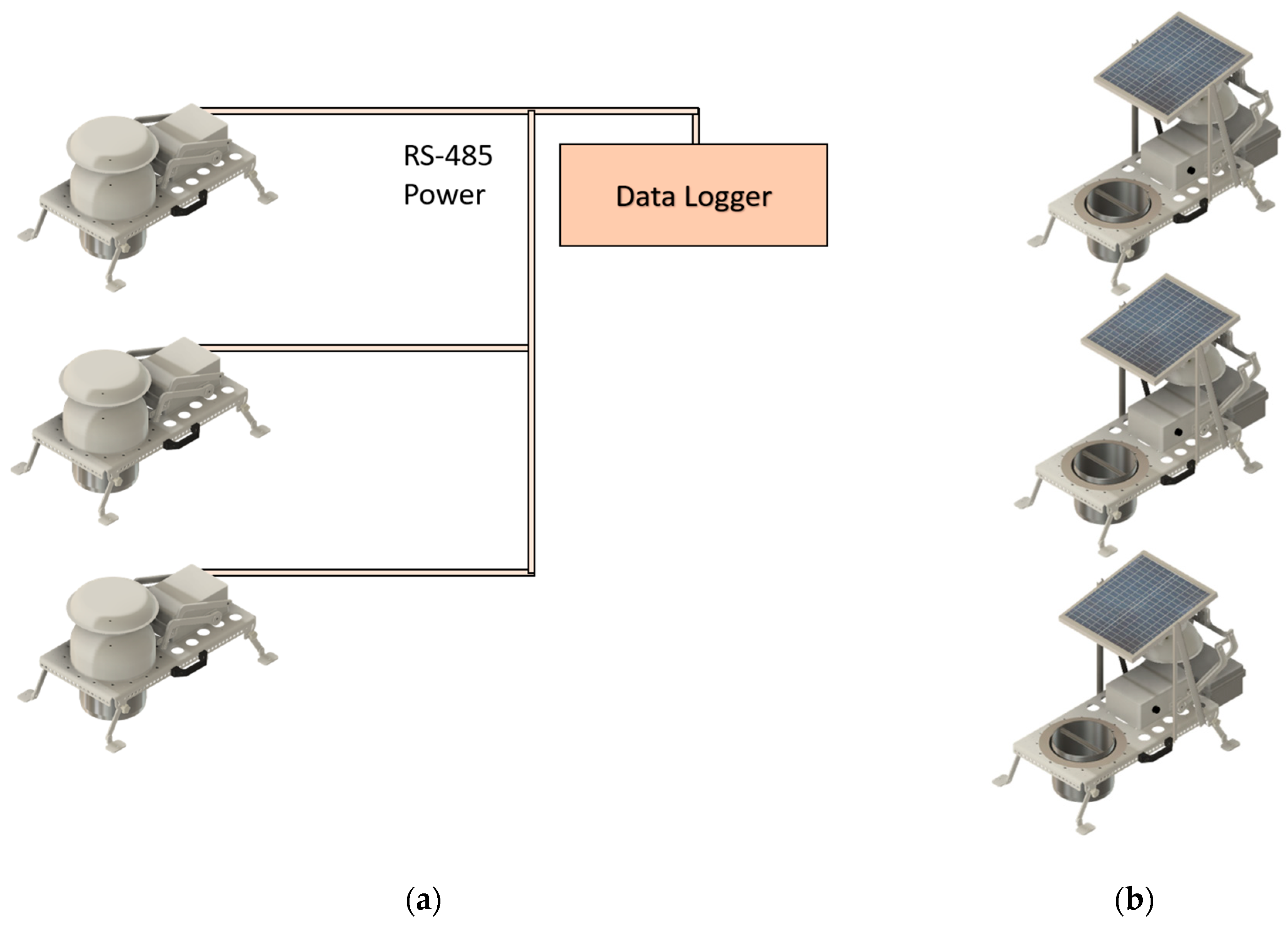

Serial or autonomous configuration.The same chamber can be used, as usual, in a network of several chambers connected to a pneumatic multiplexer and then to a single air analyzer (Figure 5), which is referred to as the “serial” configuration. This configuration is necessary for gas measurements such as nitrous oxide because an analyzer able to measure such small concentrations with such good precision is big and expensive. In other words, it is not realistic to equip each chamber with this kind of analyzer. Chambers are then connected to a pneumatic multiplexer, switching the pumped air sequentially from each chamber, injected into the analyzer, and driven back to the concerned chamber. This installation requires an external piloting, which is usually done by a datalogger that pilots the multiplexer and chambers, and reads data from the gas analyzer. SAGE automatic chambers have the possibility to attach two pipes for air pumping (IN and OUT) and use an RS-485 or RS-422 (both modules can be mounted on the main PCB) to communicate with an external datalogger using a simple protocol.Another, much simpler configuration, so-called “autonomous” (Figure 6), used for the gases that do not require a unique analyzer, lets analyze gases directly under each chamber’s cloche without gas leading pipes, a pneumatic multiplexer, and a unique, expensive analyzer. Automatic SAGE chambers equipped with opaque cloche can use embedded sensors for CO2 measurement (SCD30 from Sensirion), for O2 measurement (Luminox from SST Sensing), for CH4 measurement (TGS2611 from Figaro), for NH3 and H2S (SC05-NH23 and SC05-H2S from Shenzhen Shenchen Technology Co.). All these gases can be measured simultaneously; however, H2S presence can greatly affect CH4 sensor readings. Additionally, each CH4 sensor must be individually calibrated and corrected for air temperature and air moisture, which is a rather complex process [18]. Air constants such as air temperature, air moisture, and air pressure are sensed by the BME280 from Bosch. SAGE chambers equipped with transparent cloche can embed BME280 and CO2, O2, and CH4 sensors only, as under a transparent cloche, the PCB should be small to avoid shadowing enclosed vegetation. However, for any special needs, everything can be adapted. Used CO2 and O2 sensors are the same as for our nomad chambers and are already described in our previous paper [11] and will not be compared here. We will only recall that obviously, the small, cheap sensors are not as accurate as a big, expensive analyzer. There is no miracle. However, small sensors can be based on the same technology, such as Non-Dispersive Infrared (NDIR), and their accuracy is often limited in terms of the absolute value. For the closed chambers, the value flux calculations are based on measured concentration variations, not on the absolute value. Also, using leading air pipes with closed chambers induces some errors. In case of any leak, errors can be important. And the leak occurs all the more, there are numerous pneumatic connections between chambers and multiplexer, between multiplexer and analyzer, or between analyzer and the pump.Any possible leak in a connection is potentially disastrous, as the pressure is lower inside the pumped air tubes and higher inside the driven back air tubes compared to the atmospheric pressure. Inside the multiplexer, there is also a set of solenoid valves, which are rather sensible component that may leak and break down. The pump itself may also leak and break down. The installation with embedded sensors of the lowest accuracy may, all things considered, prove to be more accurate and more reliable.Another benefit of the embedded sensors is the possibility of simultaneous chamber measurement, allowing us to separate spatial variability from temporal variability. Indeed, with the unique analyzer installation, there is no alternative but to perform sequential measurements. In this case, the measurements coming from different chambers may vary because of chamber location (spatial variability), but also because of the chamber measurement period during the day (temporal variability). When the sensors are embedded under the cloche of each chamber, nothing prevents us from measuring at the same time. Also, each chamber is equipped with 32Gb internal memory, allowing to log acquired data. If chamber closure is triggered every three hours for ten minutes, 32Gb provide enough memory for 2000 years of measurements, which is rather comfortable. Data saved in the internal memory can be retrieved by RS-485 or RS-422, whichever is used, by direct USB connection, or by physically removing the SD card, which is the fastest way. This SD card (micro-SD card in fact) is accessible without chamber dismounting but deported into a waterproof SD card holder.The embedded memory may serve to save acquired data, but also to save a log file that includes any information helping to identify dysfunction, if any, and the configuration file.It is a matter of internal soft programming, which is open to each user. In our laboratory, we chose to check and record results for each sensor at each microcontroller boot or wakeup. Any action required is logged and the result saved. If errors are constated adapted checks are performed and results saved. This log file is very useful for troubleshooting.

-

External sensors.Auxiliary measurements, such as soil/water temperature or soil water content, are possible using several sensors. We are always adding soil/water temperature sensors based on the DS18B20 chip, soil water content when the chamber is used on the soil surface, and based on FDR technology with analog output. Other sensors can be added, one analog and a few using I²C communication on six free I²C lines from the multiplexer (one of the lines is a 3.3V logical level). Free I²C lines allow adding a few Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADC), I²C to UART converters for serial communications, and so on, expanding evolution possibilities. An optional GPS (TTL communication) is foreseen, and its connector is optionally placed on the main box. The microcontroller manages it and records the chamber position when a measuring cycle is triggered. This possibility may be interesting when the chamber is freely floating on a lake. For additional sensors, a connector or cable gland should be added.

-

Internal data logger and battery-powered operations.As the chambers can be autonomous for gas analysis, the step to make them autonomous for functioning is relatively small. There is everything onboard, inside each chamber, to pilot its own actions according to the configuration file with the help of an embedded internal RTC. If a 7S3P Li-ion battery made with 4000mAh capacity 18650 elements is attached, 6 weeks of the chamber’s functioning is possible (10 minutes cycle every 3 hours) if the chamber enters deep sleep mode between each cycle. This mode is possible as the internal RTC has its own little rechargeable battery that can power it for years without recharging, and as this RTC can wake up the microcontroller at a programmed date.If an individual solar panel 40cmx33cm is added on the top of the chamber, the limitation of the chamber battery usage is greatly increased, but the limits are not yet known, as our setup was always working correctly during this year. It should be tested with lower solar radiation and lower temperatures that may affect Li-ion battery performance, but locally, as these conditions are specific to each location. When the used solar panel is sufficient for southern France, it may not be sufficient for Greenland.Usual scheduling imposes a periodic cycle triggered every X time. However, we can set SEGE chambers to trigger a cycle randomly with a minimum and maximum waiting time. In this case, if, in spite of this, we want to keep chamber closure all at the same time without any external data logger, we can set one chamber as the master, triggering the other chamber closure. But this is purely a programming matter, not a hardware problem, except for the need to connect all the chambers with a communication line.

-

Anti-pinch grids.For chamber installation on an agricultural plot sown, for example, with winter wheat or rapeseed. There is always a possibility that a straw or other vegetation material gets pinched during chamber closure. In this case, measurements are not valid as the chamber airtightness is compromised. To prevent this kind of situation, we can temporarily attach the anti-pinch grids (Figure 7).

-

Opaque or transparent cloche.An opaque cloche is used when only the soil or water, gas production, or sink is studied. To include photosynthetic activity, a transparent cloche should be used. We are using a PMMA cloche for this purpose, along with a small under-cloche PCB. A transparent cloche is never completely transparent; the chamber base is not transparent, and the collar, even if made from PMMA, is neither totally transparent. A condensation may also be observed on the interior closed cloche [19], which is affecting the solar radiation transmission. All these components stop some percentage of solar radiation. When a transparent cloche is used, the air temperature trapped under this cloche during the measurement cycle can have its temperature quickly rise; typically, 15°C during 10 minutes of closure under the southern French sun. For this reason, air temperature should be checked, and the measurement cycle should end if the air temperature rise is judged too high. Also, as the photosynthetic activity depends on Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR), which can change during the measurement cycle due to the cloud presence, a PAR sensor should be added and the corresponding data recorded. The transparent-cloche-equipped chamber should be oriented with the under-cloche PCB on the north side, and to prevent an eventual solar panel from shadowing the measurement zone.An opaque cloche is used when studying only soil or water, gas production/sink. To include photosynthetic activity, a transparent cloche is required. For this purpose, we use a PMMA cloche with a small printed circuit board holding sensors positioned beneath it, along with a transparent fan. A transparent cloche is never completely transparent: the base of the chamber is neither, and the collar, even if made of PMMA, is not entirely transparent. Condensation can also form inside the closed cloche [19], affecting the transmission of solar radiation. All these components block some of the solar radiation. When using a transparent cloche, the temperature of the air trapped beneath it during the measurement cycle may rise rapidly, typically by 15°C in 10 minutes under the southern French sun. Therefore, it is important to monitor the air temperature and interrupt the measurement cycle if the temperature rise is deemed excessive. Furthermore, since photosynthetic activity depends on photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), which can vary during the measurement cycle due to cloud cover, it is necessary to add a PAR sensor and record the corresponding data. The chamber equipped with a transparent cloche must be oriented so that the printed circuit board under-cloche faces north; this orientation is necessary to prevent an eventual solar panel from casting a shadow on the measurement area.

-

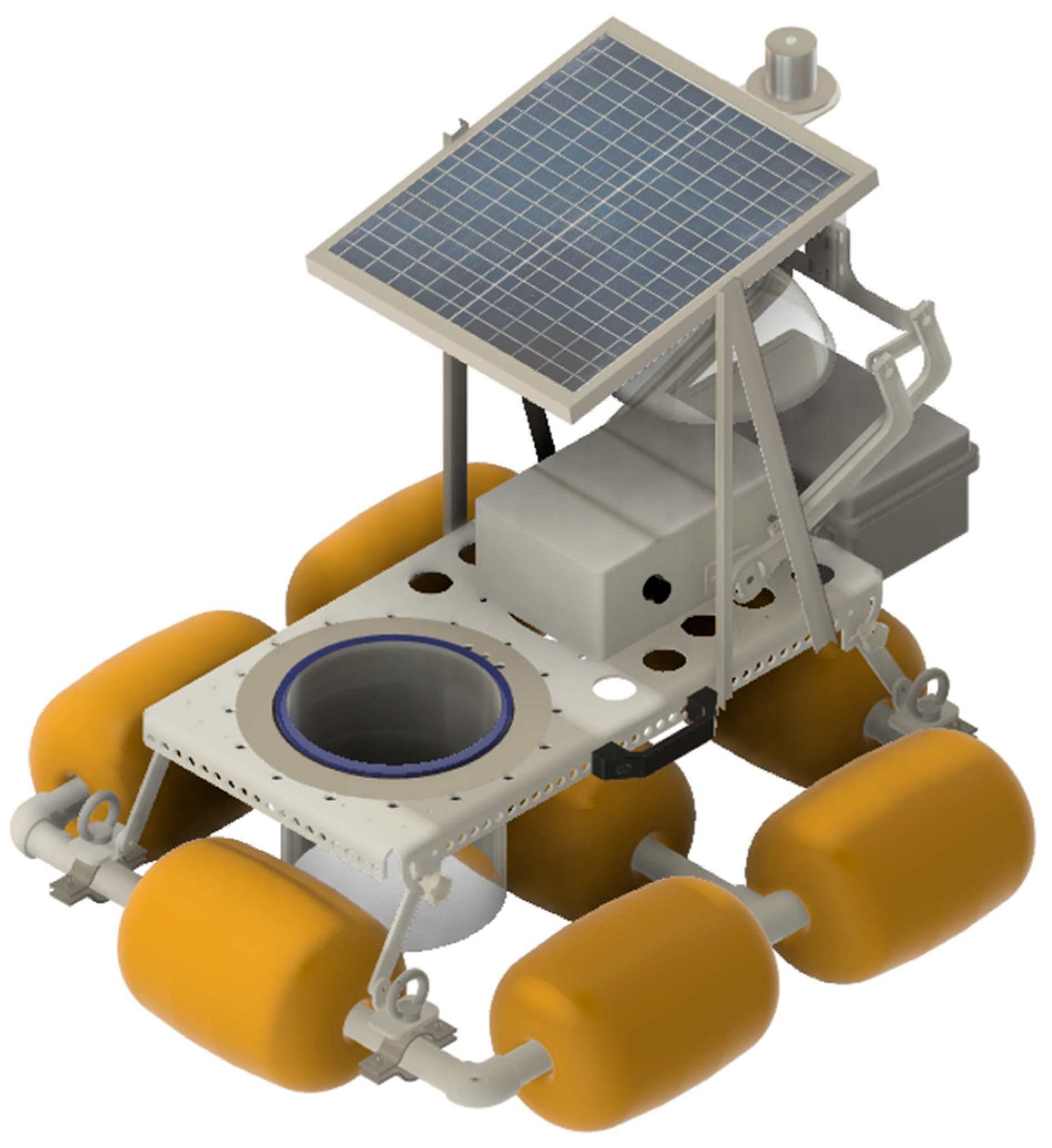

Soil or water monitoring.To our knowledge, no commercial chamber is specifically designed for use on the water surface. This is certainly a deficiency, as water also exchanges gases with the atmosphere, and until now, scientists have had to improvise to obtain the relevant measurements.For monitoring water exchange with the atmosphere, waterwings made of standard PVC tubing and fittings, as well as fishing buoys, can be added (Figure 8). A standard chamber, usually equipped with a battery, is then attached to these waterwings. The stainless-steel collar is replaced with a PVC or PMMA collar. Figure 8 shows a SAGE chamber with a transparent cloche equipped with a PAR sensor mounted on the solar panel and a battery housed in a waterproof casing at the rear of the chamber.The described floating setup is suitable for relatively calm water surfaces, but cannot be used on oceans or rough waters.

3. Results

3.1. Durability and Adaptability

3.2. Maintenance and Troubleshooting

3.3. Versatility and Adaptability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHGs | Greenhouse gases |

| EC | Eddy Covariance |

| ICOS | Integrated carbon observation system |

| RZA | Réseau des zones atelier |

| SSR | Soli state relay |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| UPS | Uninterruptible power supply |

| SD | Secure digital |

| TTL | Transistor-Transistor Logic |

| UART | Universal asynchronous receiver transmitter |

| ADC | Analog to digital converter |

| DAC | Digital to analog converter |

| PAR | Photosynthetically active radiation |

| NDIR | Non-Dispersive Infrared |

References

- Bond-Lamberty, B.; Thomson, A. Temperature-associated increases in the global soil respiration record. Nature 2010, 464, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Shi, H.; Zhong, L.; et al. Nitrous oxide sources, mechanisms and mitigation. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2025, 6, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günthel, M.; Donis, D.; Kirillin, G.; et al. Contribution of oxic methane production to surface methane emission in lakes and its global importance. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burba, G. Eddy Covariance Method for Scientific, Regulatory, and Commercial Applications. LI-COR Biosciences 2022. Available online: https://www.licor.com/products/eddy-covariance/ec-book.

- Maier, M.; Weber, T.K.D.; Fiedler, J.; Fuß, R.; Glatzel, S.; Huth, V.; Jordan, S.; Jurasinski, G.; Kutzbach, L.; Schäfer, K.; Weymann, D.; Hagemann, U. Introduction of a guideline for measurements of greenhouse gas fluxes from soils using non-steady-state chambers. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2022, 185, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, F. Kohlensaure und Pflanzenwachstum. Mitt. Dtsch. Landwirtsch-Ges. 1920, 35–363. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, G.P.; Hutchinson, G.L.; Spartalian, K. Diffusion theory improves chamber-based measurements of trace gas emissions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L24817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzbach, L.; Schneider, J.; Sachs, T.; Giebels, M.; Nykänen, H.; Shurpali, N.J.; Martikainen, P.J.; Alm, J.; Wilmking, M. CO2 flux determination by closed-chamber methods can be seriously biased by inappropriate application of linear regression. Biogeosciences 2007, 4, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.; Lasso, A.; Lubberding, H.J.; Peña, M.R.; Gijzen, H.J. Biases in greenhouse gases static chambers measurements in stabilization ponds: Comparison of flux estimation using linear and non-linear models. Atmospheric Environment 2015, 109, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilski, B.M. : Wind speed influences corrected Autocalibrated Soil Evapo-respiration Chamber (ASERC) evaporation measures. Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 2022, 11, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilski, B. M.; Bustillo, V. Ultra-low-cost manual soil respiration chamber. Geosci. Instrum. Method. Data Syst. 2024, 13, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.P.; Hutchinson, G.L. Enclosure-based measurement of trace gas exchange: applications and sources of error. In Biogenic trace gases: measuring emissions from soil and water; Matson, P.A., Harris, R.C., Eds.; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK., 1995; pp. 14–51. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen, M.; Minkkinen, K.; Ojanen, P.; Kämäräinen, M.; Laurila, T.; Lohila, A. Measurements of CO2 exchange with an automated chamber system throughout the year: challenges in measuring night-time respiration on porous peat soil. Biogeosciences 2014, 11-2, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, T.B.; Venterea, R.T. Chamber-Based Trace Gas Flux Measurements. IN Sampling Protocols Chapter 3, R.F. Follett, USA, 2010, pp. 3-1 to 3-39. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/np212/chapter%203.%20gracenet%20Trace%20Gas%20Sampling%20protocols.pdf.

- Christiansen, J. R.; Korhonen, J. F. J.; Juszczak, R.; Giebels, M.; Pihlatie, M. Assessing the effects of chamber placement, manual sampling and headspace mixing on CH4 fluxes in a laboratory experiment. Plant and Soil 2011, 343, 171–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klein, C.A.M.; Harvey, M.; Clough, T.J.; Petersen, S.O.; Chadwick, D.R.; Venterea, R.T. Global Research Alliance N2O chamber methodology guidelines: Introduction, with health and safety considerations. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, M.; Acosta, M.; Kiese, R.; Altimir, N.; Brümmer, C.; Crill, P. M.; Darenová, E.; Fuß, R.; Gielen, B.; Graf, A.; Klemedtsson, L.; Lohila, A.; Longdoz, B.; Lindroth, A.; Nilsson, M. B.; Jiménez, S.M.; Merbold, L.; Montagnani, L.; Peichl, M.; Pihlatie, M.; Pumpanen, J.; Ortiz, P.S.; Silvennoinen, H.; Skiba, U.M.; Vestin, P.; Weslien, P.; Janous, D.; Kutsch, W.L. Standardisation of chamber technique for CO2, N2O and CH4 fluxes measurements from terrestrial ecosystems. International Agrophysics 2018, 32, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastviken, D.; Nygren, J.; Schenk, J.; Parellada Massana, R.; Duc, N.T. Technical note: Facilitating the use of low-cost methane CH4 sensors. Biogeosciences 2020, 17-13, 3659–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P; Hammerle, A; Zeeman, M; Wohlfahrt, G. On the calculation of daytime CO2 fluxes measured by automated closed transparent chambers. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2018, 263, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).