Submitted:

07 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

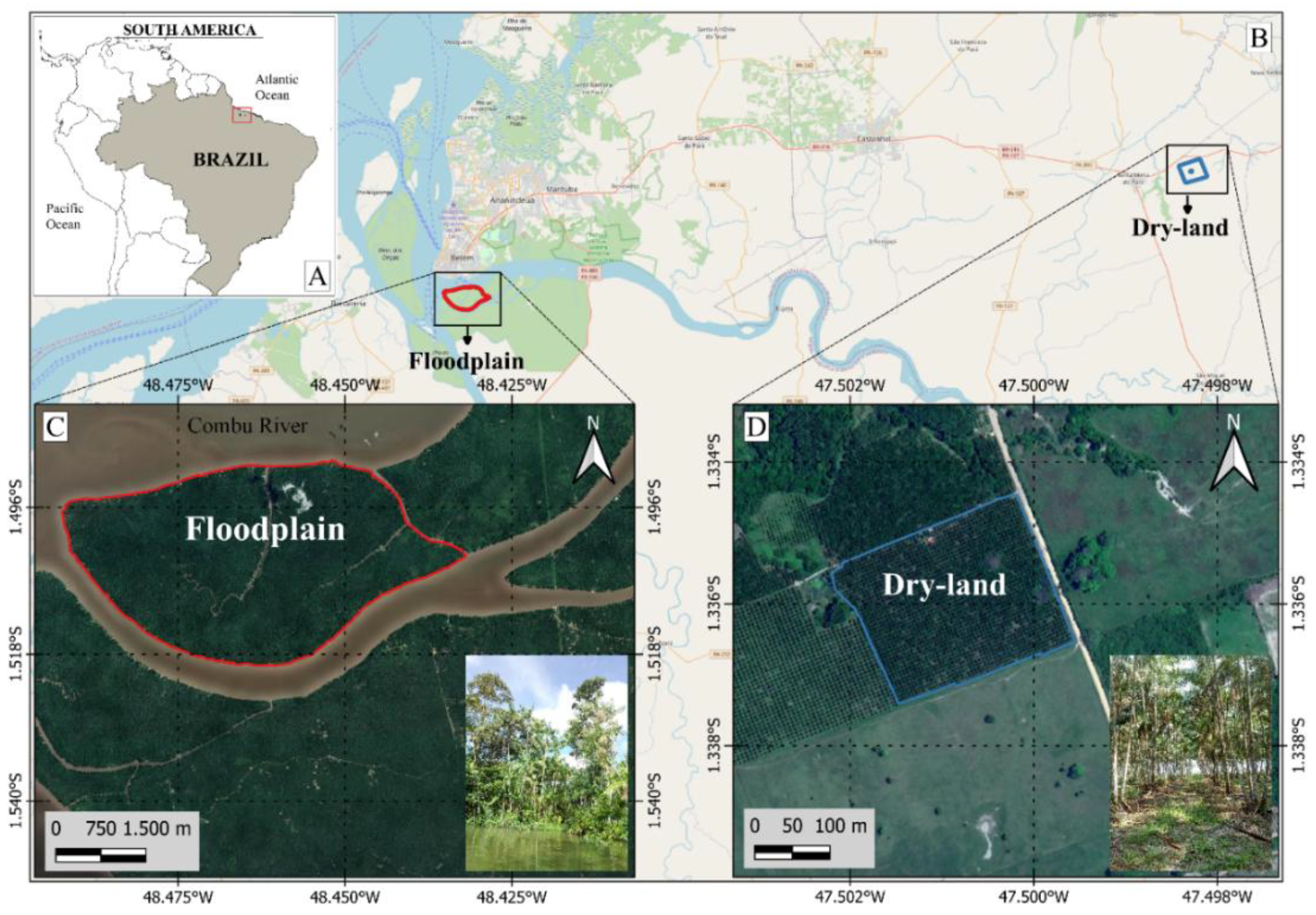

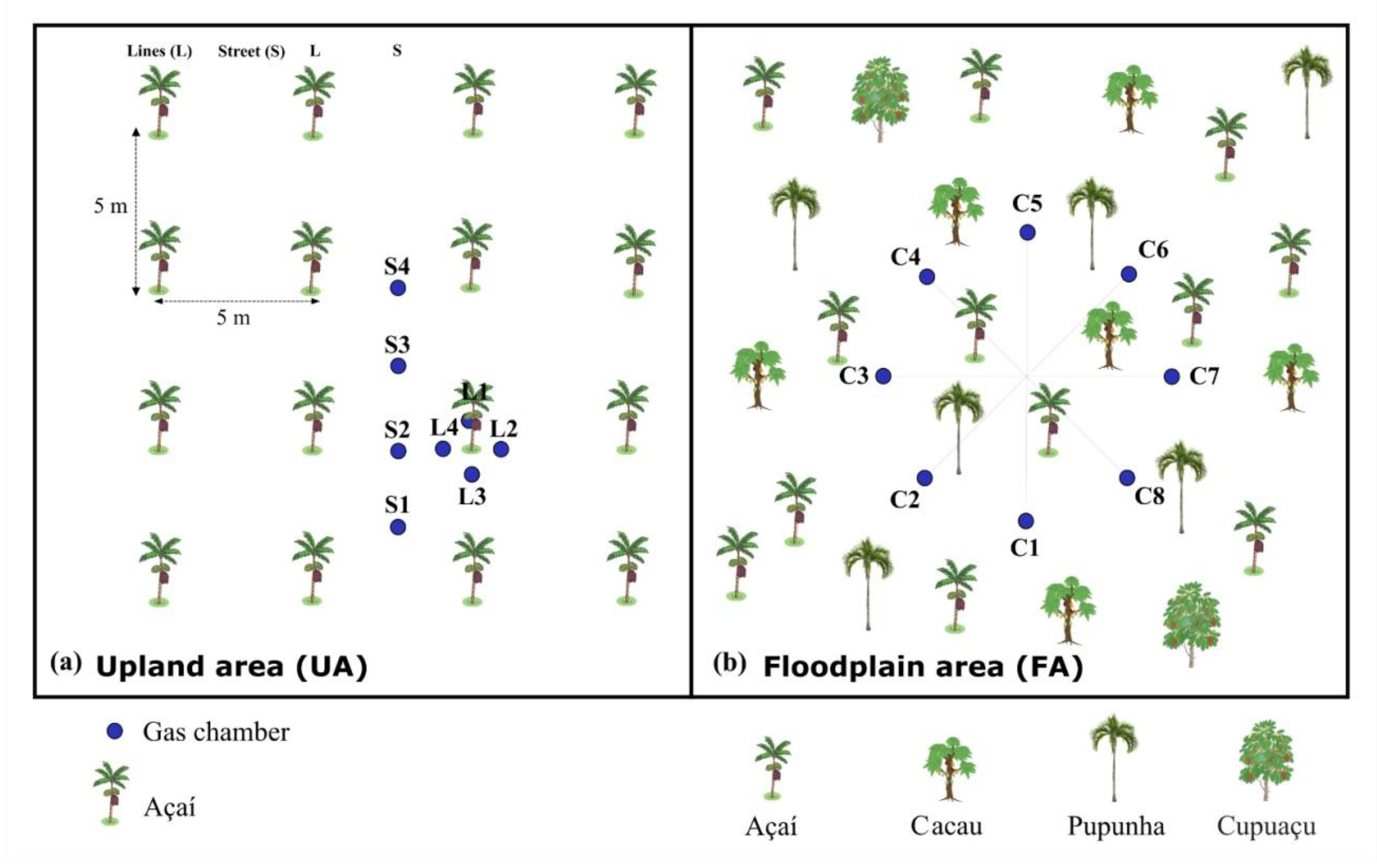

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Experiment on Upland

2.1.2. Comparison Between Dry Land and Floodplain

2.2. Trace Gas Flux Measurements

2.3. Soil Sampling and Analysis and Environmental Characterization

2.4. Environmental Characterization

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

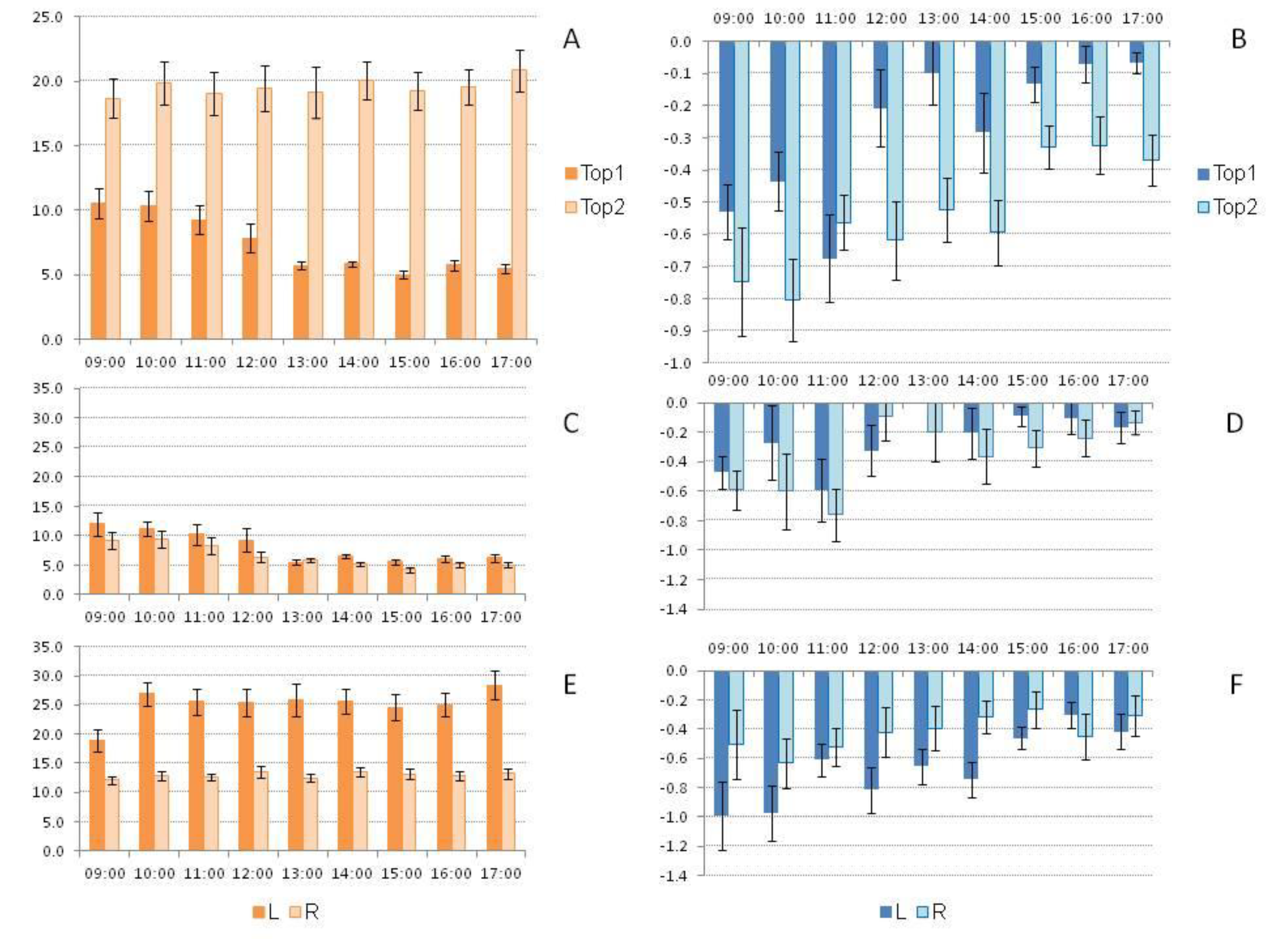

3.1. Carbon Dioxide and Methane Flux

3.1.1. Spatial Analysis of Homogeneous Açaí Planting in the Dry Season

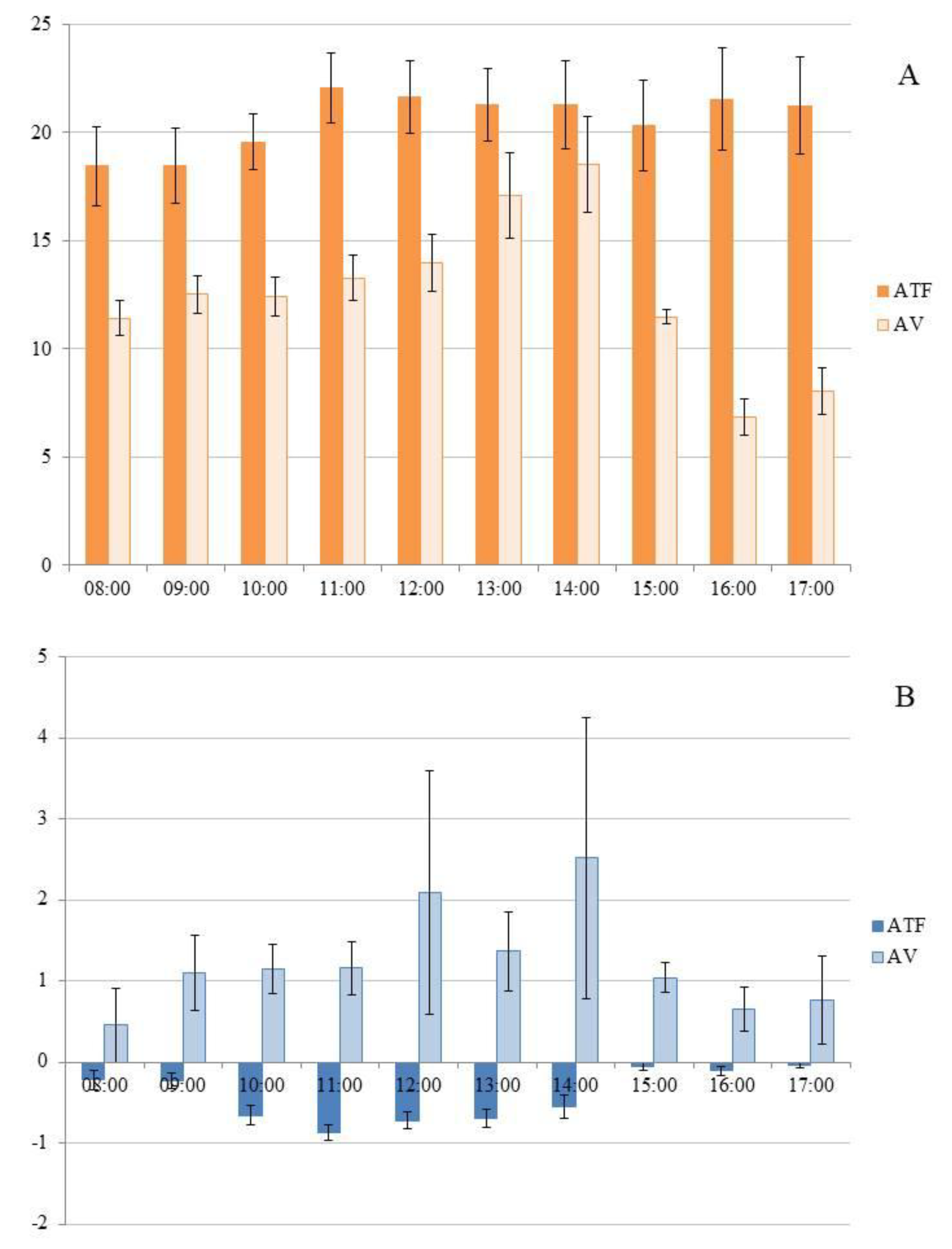

3.1.2. Simultaneous Flow Measurements in Upland and Floodplains

3.2. Seasonal Flux of Greenhouse Gases

3.3. Environmental Variables

3.4. Correlations Between Flow and Environmental Variable

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Carbon Flux in Açaí Plantation on Dry Land

4.2. Soil Carbon Flux During the Rainy Season in Upland Planting Compared to Estuary Floodplain

4.3. Annual Soil Carbon Flux in Upland Planting Compared to Estuary Floodplain

5. Conclusion

References

- IPCC Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri R. K, Meyer, L.A., Eds.; Geneva, 2014;

- Verchot, L. V.; Dannenmann, M.; Kengdo, S.K.; Njine-Bememba, C.B.; Rufino, M.C.; Sonwa, D.J.; Tejedor, J. Land-Use Change and Biogeochemical Controls of Soil CO2, N2O and CH4 Fluxes in Cameroonian Forest Landscapes. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2020, 17, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Ito, A.; Yonemura, S.; Takeuchi, W. Estimation of Global Soil Respiration by Accounting for Land-Use Changes Derived from Remote Sensing Data. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 200, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossio, D.A.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Fargione, J.; Sanderman, J.; Smith, P.; Wood, S.; Zomer, R.J.; von Unger, M.; Emmer, I.M.; et al. The Role of Soil Carbon in Natural Climate Solutions. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, D.G.T.; Bagchi, S. Greening of the Earth Does Not Compensate for Rising Soil Heterotrophic Respiration under Climate Change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 2029–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, M.L. Educational Programs for Team Delivery. Interdisciplinary Education of Health Associates. Acad. Med. 1975, 50, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, N. de O.; Brito, J.; Caumo, S.; Arana, A.; Hacon, S. de S.; Artaxo, P.; Hillamo, R.; Teinilä, K.; Medeiros, S.R.B. de; Vasconcellos, P. de C. Biomass Burning in the Amazon Region: Aerosol Source Apportionment and Associated Health Risk Assessment. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 120, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denardin, L.G. de O.; Alves, L.A.; Ortigara, C.; Winck, B.; Coblinski, J.A.; Schmidt, M.R.; Carlos, F.S.; Toni, C.A.G. de; Camargo, F.A. de O.; Anghinoni, I.; et al. How Different Soil Moisture Levels Affect the Microbial Activity. Ciência Rural 2020, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchot, L. V.; Davidson, E.A.; Cattânio, J.H.; Ackerman, I.L. Land-Use Change and Biogeochemical Controls of Methane Fluxes in Soils of Eastern Amazonia. Ecosystems 2000, 3, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira-Guedes, A.C.; Leal, G.; Fischer, G.; Aguiar, L.J.; Júnior, N.J.; Baia, A.L.; Guedes, M. Carbon Emissions in Hydromorphic Soils from an Estuarine Floodplain Forest in the Amazon River. Brazilian J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 56, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattanio, J.H.; Anderson, A.B.; Carvalho, M.S. Floristic Composition and Topographic Variation in a Tidal Floodplain Forest in the Amazon Estuary. Rev. Bras. Botânica 2002, 25, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, M.; Sirén, A.; Kalliola, R.; Wild, D.; Harvest, S. Açaí: The Forest Farms of the Amazon Estuary. In Diagnosing Wild Species Harvest; Salo, M., Sirén, A., Kalliola, R., Eds.; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 191–202 ISBN 9780123972040.

- Cattânio, J.H.; Davidson, E.A.; Nepstad, D.C.; Verchot, L.V.; Ackerman, I.L. Unexpected Results of a Pilot Throughfall Exclusion Experiment on Soil Emissions of CO2, CH4, N2O, and NO in Eastern Amazonia. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2002, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosier, A.; Wassmann, R.; Verchot, L.; King, J.; Palm, C. Methane and Nitrogen Oxide Fluxes in Tropical Agricultural Soils: Sources, Sinks and Mechanisms. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2004, 6, 11–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, W.D.; Mustin, K.; Hilário, R.R.; Vasconcelos, I.M.; Eilers, V.; Fearnside, P.M. Deforestation Control in the Brazilian Amazon: A Conservation Struggle Being Lost as Agreements and Regulations Are Subverted and Bypassed. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.J.; Carvalheiro, L.G.; Maués, M.M.; Jaffé, R.; Giannini, T.C.; Freitas, M.A.B.; Coelho, B.W.T.; Menezes, C. Anthropogenic Disturbance of Tropical Forests Threatens Pollination Services to Açaí Palm in the Amazon River Delta. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, M.A.B.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Albernaz, A.L.K.M.; Magalhães, J.L.L.; Lees, A.C. Floristic Impoverishment of Amazonian Floodplain Forests Managed for Açaí Fruit Production. For. Ecol. Manage. 2015, 351, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brondizio, E.S.; Moran, E.F. Human Dimensions of Climate Change: The Vulnerability of Small Farmers in the Amazon. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.C. dos; Sena, A.L. dos S.; Homma, A.K.O. Viabilidade Econômica Do Manejo de Açaizais No Estuário Amazônico: Estudo de Caso Na Região Do Rio Tauerá-Açu, Abaetetuba – Estado Do Pará. In Proceedings of the Sociedade Brasileira de Economia, Administração e Sociologia Rural; Vitória, 2012; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Farias Neto, J.T.; Resende, M.D.V.; Oliveira, M. do S.P. Seleção Simultânea Em Progênies de Açaizeiro Irrigado Para Produção e Peso Do Fruto. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2011, 33, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, G. dos S.; Homma, A.K.O.; Menezes, A.J.E.A. de; Palheta, M.P. Análise Da Produção e Comercialização de Açaí No Estado Do Pará, Brasil. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 10, 35215–35221. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INMET Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Available online: http://www.inmet.gov.br/portal/index.php?r=bdmep/bdmep (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- EMBRAPA Mapas de Solo - Brasil.

- Wilkinson, J.; Bors, C.; Burgis, F.; Lorke, A.; Bodmer, P. Measuring CO2 and CH4 with a Portable Gas Analyzer: Closed-Loop Operation, Optimization and Assessment. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0193973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellón, S.E.M.; Cattanio, J.H.; Berrêdo, J.F.; Rollnic, M.; Ruivo, M. de L.; Noriega, C. Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Mangrove Forest Soil in an Amazon Estuary. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 5483–5497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, E.; Vestin, P.; Crill, P.; Persson, T.; Lindroth, A. Short-Term Effects of Thinning, Clear-Cutting and Stump Harvesting on Methane Exchange in a Boreal Forest. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 6095–6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.R.; Weil, R.R. Microwave Irradiation of Soil for Routine Measurement of Microbial Biomass Carbon. Biol. Fertil. Soils 1998, 27, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalembasa, S.J.; Jenkinson, D.S. A Comparative Study of Titrimetric and Gavimetric Methods for Determination of Organic Carbon in Soil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1973, 24, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An Extraction Method for Measuring Soil Microbial Biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, P.C.; Landman, A.; Pruden, G.; Jenkinson, D.S. Chloroform Fumigation and the Release of Soil Nitrogen: A Rapid Direct Extraction Method to Measure Microbial Biomass Nitrogen in Soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1985, 17, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S. Determination of Microbial Biomass C and N in Soil. In Advances in Nitrogen Cycling in Agricultural Ecosystems; Wilson, J.R., Ed.; CAB International: Wallingford, 1988; pp. 368–386. [Google Scholar]

- Embrapa Manual de Métodos de Análises de Solo; Teixeira, P. C., Donagemma, G.K., Fontana, A., Teixeira, W.G., Eds.; 3rd ed.; Brasília, DF: Embrapa: Brasília, DF, 2017; ISBN 9788570357717. [Google Scholar]

- ANA Agência Nacional de Águas e Saneamento Básico: Rede Hidrometeorológica Nacional. Available online: https://www.snirh.gov.br/hidroweb/mapa (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Courtois, E.A.; Stahl, C.; Van den Berge, J.; Bréchet, L.; Van Langenhove, L.; Richter, A.; Urbina, I.; Soong, J.L.; Peñuelas, J.; Janssens, I.A. Spatial Variation of Soil CO2, CH4 and N2O Fluxes Across Topographical Positions in Tropical Forests of the Guiana Shield. Ecosystems 2018, 21, 1445–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, P.J.; Edwards, N.T.; Garten, C.T.; Andrews, J.A. Separating Root and Soil Microbial Contributions to Soil Respiration: A Review Ofmethods and Observations. Biogeochemistry 2000, 48, 115–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, R.; Ohta, S.; Ishizuka, S.; Heriyanto, J.; Wicaksono, A. Seasonal Changes in the Spatial Structures of N2O, CO2, and CH4 Fluxes from Acacia Mangium Plantation Soils in Indonesia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotta, E.D.; Veldkamp, E.; Guimarães, B.R.; Paixão, R.K.; Ruivo, M.L.P.; Almeida, S.S. Landscape and Climatic Controls on Spatial and Temporal Variation in Soil CO2 Efflux in an Eastern Amazonian Rainforest, Caxiuanã, Brazil. For. Ecol. Manage. 2006, 237, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.Q.; Higuchi, N.; Teixeira, L.M.; Dos Santos, J.; Laurance, S.G.; Trumbore, S.E. Response of Tree Biomass and Wood Litter to Disturbance in a Central Amazon Forest. Oecologia 2004, 141, 596–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizuka, S.; Tsuruta, H.; Murdiyarso, D. An Intensive Field Study on CO2, CH4, and N2O Emissions from Soils at Four Land-Use Types in Sumatra, Indonesia. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16, 22–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verchot, L.V.; Brienza, S.; de Oliveira, V.C.; Mutegi, J.K.; Cattânio, J.H.; Davidson, E.A. Fluxes of CH4, CO2, NO, and N2O in an Improved Fallow Agroforestry System in Eastern Amazonia. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Soil-Atmosphere Exchange of N2O, CH4, and CO2 and Controlling Environmental Factors for Tropical Rain Forest Sites in Western Kenya. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2007, 112, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Balser, T.; Buchmann, N.; Hahn, V.; Potvin, C. Linking Tree Biodiversity to Belowground Process in a Young Tropical Plantation: Impacts on Soil CO2 Flux. For. Ecol. Manage. 2008, 255, 2577–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Mer, J.; Roger, P. Production, Oxidation, Emission and Consumption of Methane by Soils: A Review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2001, 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etminan, M.; Myhre, G.; Highwood, E.J.; Shine, K.P. Radiative Forcing of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, and Nitrous Oxide: A Significant Revision of the Methane Radiative Forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 12–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, W.J.; Webber, C.P.; Cox, P.M.; Huntingford, C.; Lowe, J.; Sitch, S.; Chadburn, S.E.; Comyn-Platt, E.; Harper, A.B.; Hayman, G.; et al. Increased Importance of Methane Reduction for a 1.5 Degree Target. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 054003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugokencky, E.J.; Nisbet, E.G.; Fisher, R.; Lowry, D. Global Atmospheric Methane: Budget, Changes and Dangers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2011, 369, 2058–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutaur, L.; Verchot, L. V. A Global Inventory of the Soil CH4 Sink. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2007, 21, GB4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Nepstad, D.C.; Ishida, F.Y.; Brando, P.M. Effects of an Experimental Drought and Recovery on Soil Emissions of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, Nitrous Oxide, and Nitric Oxide in a Moist Tropical Forest. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 2582–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Gundersen, P.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, G.; Christiansen, J.R.; Mo, J.; Dong, S.; Zhang, T. Soil-Atmosphere Exchange of N2O, CO2 and CH4 along a Slope of an Evergreen Broad-Leaved Forest in Southern China. Plant Soil 2009, 319, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, W.L.; Neff, J.; Mcgroddy, M.; Veldkamp, E.; Keller, M.; Cosme, R. Effects of Soil Texture on Belowground Carbon and Nutrient Storage in a Lowland Amazonian Forest Ecosystem. 2000, 193–209. [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, F.L.; Tait, D.E.N.; Flanagan, P.W.; Van Clever, K. Microbial Respiration and Substrate Weight Loss-I. A General Model of the Influences of Abiotic Variables. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1977, 9, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, K.; Hirano, T.; Okimoto, Y.; Hirata, R.; Kiew, F.; Melling, L.; Aeries, E.B.; Lo, K.S.; Musin, K.K.; Waili, J.W.; et al. Soil Carbon Dioxide Emissions Due to Oxidative Peat Decomposition in an Oil Palm Plantation on Tropical Peat. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 254, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A.; Akhand, A.; Manna, S.; Dutta, S.; Das, I.; Hazra, S.; Rao, K.H.; Dadhwal, V.K. Measuring Daytime CO2 Fluxes from the Inter-Tidal Mangrove Soils of Indian Sundarbans. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 72, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, R.; Rochette, P.; Topp, E.; Pattey, E.; Desjardins, R.L.; Beaumont, G. Methane and Carbon Dioxide Fluxes from Poorly Drained Adjacent Cultivated and Forest Sites. Can. J. Soil Sci. 1994, 74, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Verchot, L. V; Cattânio, J.H.; Ackerman, I.L.; Carvalho, J.E.M. Effects of Soil Water Content on Soil Respiration in Forests and Cattle Pastures of Eastern Amazonia; 2000; Vol. 48;

- Segers, R. Methane Production and Methane Consumption--a Review of Processes Underlying Wetland Methane Fluxes [Review]. Biogeochemistry 1998, 41, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.; Mitre, M.E.; Stallard, R.F. Consumption of Atmospheric Methane in Soils of Central Panama: Effects of Agricultural Development. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 1990, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.A.P.; Bernoux, M.; Cerri, C.C.; Feigl, B.J.; Piccolo, M.C. Seasonal Variation of Soil Chemical Properties and CO2 and CH4 Fluxes in Unfertilized and P-Fertilized Pastures in an Ultisol of the Brazilian Amazon. Geoderma 2002, 107, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steudler, P.A.; Melillo, J.M.; Feigl, B.J.; Neill, C.; Piccolo, M.C.; Cerri, C.C. Consequence of Forest-to-Pasture Conversion on CH4 Fluxes in the Brazilian Amazon Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1996, 101, 18547–18554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihi, D.; Davidson, E.A.; Savage, K.E.; Liang, D. Simultaneous Numerical Representation of Soil Microsite Production and Consumption of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, and Nitrous Oxide Using Probability Distribution Functions. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roslev, P.; King, G.M. Regulation of Methane Oxidation in a Freshwater Wetland by Water Table Changes and Anoxia. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1996, 19, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, G.; Huang, W.; Liu, J. Increased Litter Input Increases Litter Decomposition and Soil Respiration but Has Minor Effects on Soil Organic Carbon in Subtropical Forests. Plant Soil 2015, 392, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanin, N.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Barantal, S.; Schimann, H.; Fromin, N. Does Variability in Litter Quality Determine Soil Microbial Respiration in an Amazonian Rainforest? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoyChowdhury, T.; Bramer, L.; Hoyt, D.W.; Kim, Y.-M.; Metz, T.O.; McCue, L.A.; Diefenderfer, H.L.; Jansson, J.K.; Bailey, V. Temporal Dynamics of CO2 and CH4 Loss Potentials in Response to Rapid Hydrological Shifts in Tidal Freshwater Wetland Soils. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 114, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiese, R.; Hewett, B.; Graham, A.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Kiese, C. :; Hewett, B.; Graham, A.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. Seasonal Variability of N2O Emissions and CH4 Uptake by Tropical Rainforest Soils of Queensland, Australia. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2003, 17, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Zheng, X.; Tang, J.; Xie, B.; Liu, C.; Kiese, R.; Butterbach-Bahl, K. N2O, CH4 and CO2 Emissions from Seasonal Tropical Rainforests and a Rubber Plantation in Southwest China. Plant Soil 2006, 289, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, R. The Global Methane Cycle: Recent Advances in Understanding the Microbial Processes Involved. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2009, 1, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, S.C. Biogeochemistry of Methane Exchange between Natural Wetlands and the Atmosphere. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2005, 22, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turetsky, M.R.; Kotowska, A.; Bubier, J.; Dise, N.B.; Crill, P.; Hornibrook, E.R.C.; Minkkinen, K.; Moore, T.R.; Myers-Smith, I.H.; Nykänen, H.; et al. A Synthesis of Methane Emissions from 71 Northern, Temperate, and Subtropical Wetlands. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 2183–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldo, N.B.; Hunt, B.K.; Fadely, E.C.; Moran, J.J.; Neumann, R.B. Plant Root Exudates Increase Methane Emissions through Direct and Indirect Pathways. Biogeochem. 2019 1451 2019, 145, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgham, S.D.; Cadillo-Quiroz, H.; Keller, J.K.; Zhuang, Q. Methane Emissions from Wetlands: Biogeochemical, Microbial, and Modeling Perspectives from Local to Global Scales. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 1325–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Upland | Floodplain | |||

| Dry | Rainy | Dry | Rainy | |

| Soil moisture (Us, %) | 8.64 ± 0.51bB | 23.12 ± 0.77aB | 26.44 ± 0.70bA | 53.27 ± 1.12aA |

| pH | 4.83 ± 0.21aA | 5.16 ± 0.05aA | 4.15 ± 0.01aB | 4.15 ± 0.04aB |

| Fine roots (Mg ha-1) | 2.61 ± 0.28aA | 2.96 ± 0.36aA | 4.64 ± 0.88aA | 2.25 ± 0.42aA |

| Thick roots (Mg ha-1) | 11.38 ± 1.17aA | 8.87 ± 0.77bA | 5.91 ± 0.91aA | 3.39 ± 0.60bB |

| Total Roots (Mg ha-1) | 13.59 ± 1.38aA | 11.84 ± 1.04aA | 6.57 ± 0.40aB | 5.64 ± 0.89aB |

| Microbial carbon (g kg-1) | 0.42 ± 0.03B | ND | 1.56 ± 0.10A | ND |

| Microbial nitrogen (mg kg-1) | 6.12 ± 0.74B | ND | 46.28 ± 2.12A | ND |

| Rainy Season | |||||||||||||

| ATF | FCH4 | Ts | Us | RF | RG | TR | Ta | UR | Pa | Cm | Nm | pH | |

| FCO2 | -0,111 | 0,250** | 0,287** | -0,174** | 0,293** | 0.156** | 0,259** | -0,245** | -0,156** | ND | ND | -0,743** | |

| FCH4 | 1,000 | -0,453** | 0,137* | -0,088 | 0,028 | -0.009 | -0,493** | 0,500** | 0,142* | ND | ND | -0,067 | |

| AV | |||||||||||||

| FCO2 | 0,163** | 0,448** | -0,135* | 0,209** | 0,295** | 0,297** | 0,553** | -0,562** | -0,153* | ND | ND | -0,173** | |

| FCH4 | 1,000 | -0,043 | -0,081 | -0,078 | 0,025 | -0,019 | 0,079 | -0,099 | 0,017 | ND | ND | -0,007 | |

| Dry Season | |||||||||||||

| ATF | FCH4 | Ts | Us | RF | RG | TR | Ta | UR | Pa | Cm | Nm | pH | |

| FCO2 | -0,316** | -0,151** | 0,626** | 0,570** | -0,207** | -0,009 | -0,053 | 0,062 | 0,056 | 0.441** | 0,001 | 0,419** | |

| FCH4 | 1,000 | 0,173** | -0,173** | -0,100** | 0,204** | 0,158** | 0,057 | -0,078 | -0,215** | -0,116** | 0,116* | -0,166** | |

| AV | |||||||||||||

| FCO2 | -0,053 | 0,197 | 0,209 | 0,207 | 0,257 | 0,245 | 0,406* | -0,461* | -0,370 | 0,112 | -0,073 | 0,248 | |

| FCH4 | 1,000 | -0,307 | -0,209 | -0,119 | -0,200 | -0,169 | 0,121 | -0,241 | -0,148 | -0,019 | -0,019 | -0,175 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).