Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

- Without straw (S0);

- Straw chopped and spread (S1).

- Stubble shaved and plowed in autumn at a depth of 23–25 cm (control, deep plowing, CP);

- Stubble shaved and plowed in autumn at a depth of 10–12 cm (shallow plowing, SP);

- Stubble shaved in autumn with a disc cultivator to a depth of 8–10 cm (shallow cultivation in autumn, SC);

- Stubble left over winter and shaved before sowing with a disc cultivator at a depth of 4–5 cm (stubble left over winter, SOW);

- Direct sowing of cover crops on uncultivated land and shallow loosening with a disc cultivator to a depth of 4–5 cm (no-till with cover crops, NTC);

- Direct sowing on uncultivated land without cover crops (NT).

2.2. Soil Shear Resistance

2.3. Soil Temperature and Moisture

2.4. CO2 Emissions from Soil

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

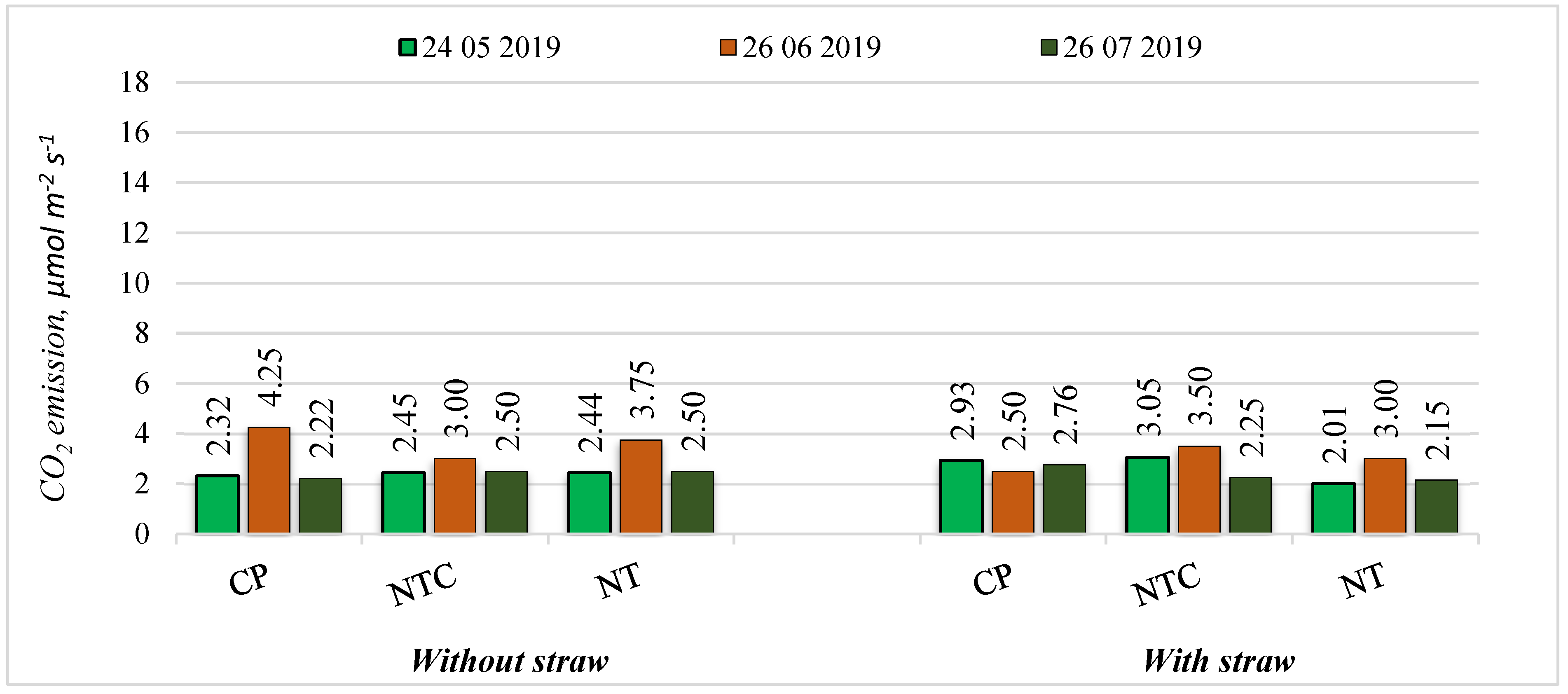

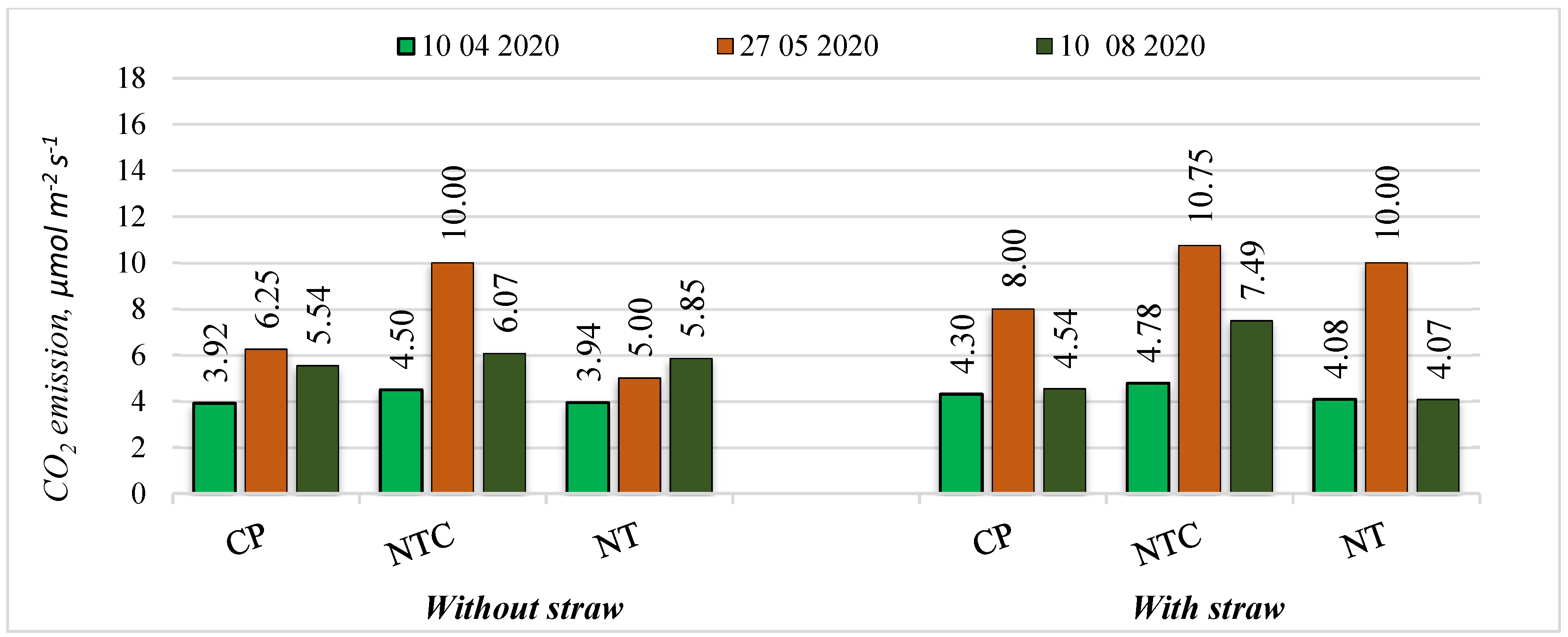

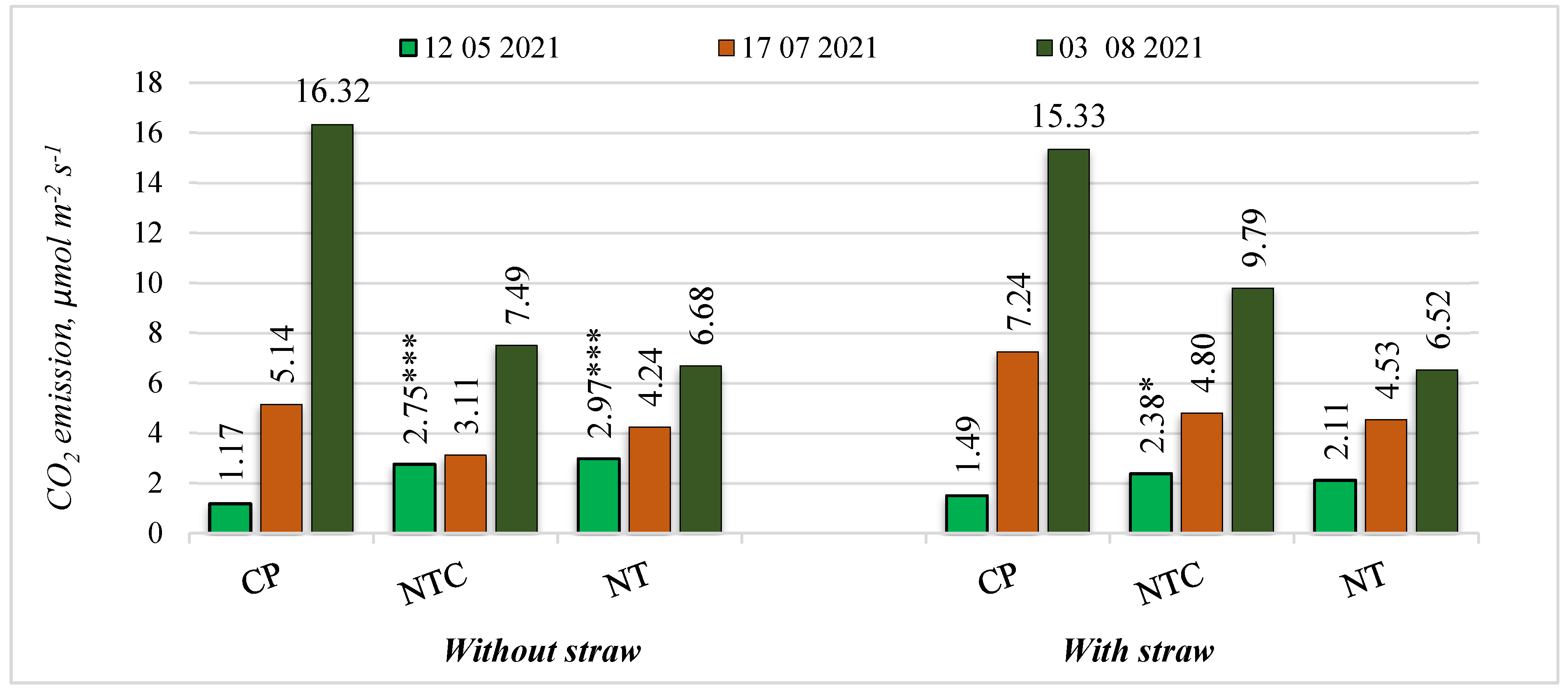

3.1. CO2 Emissions from Soil

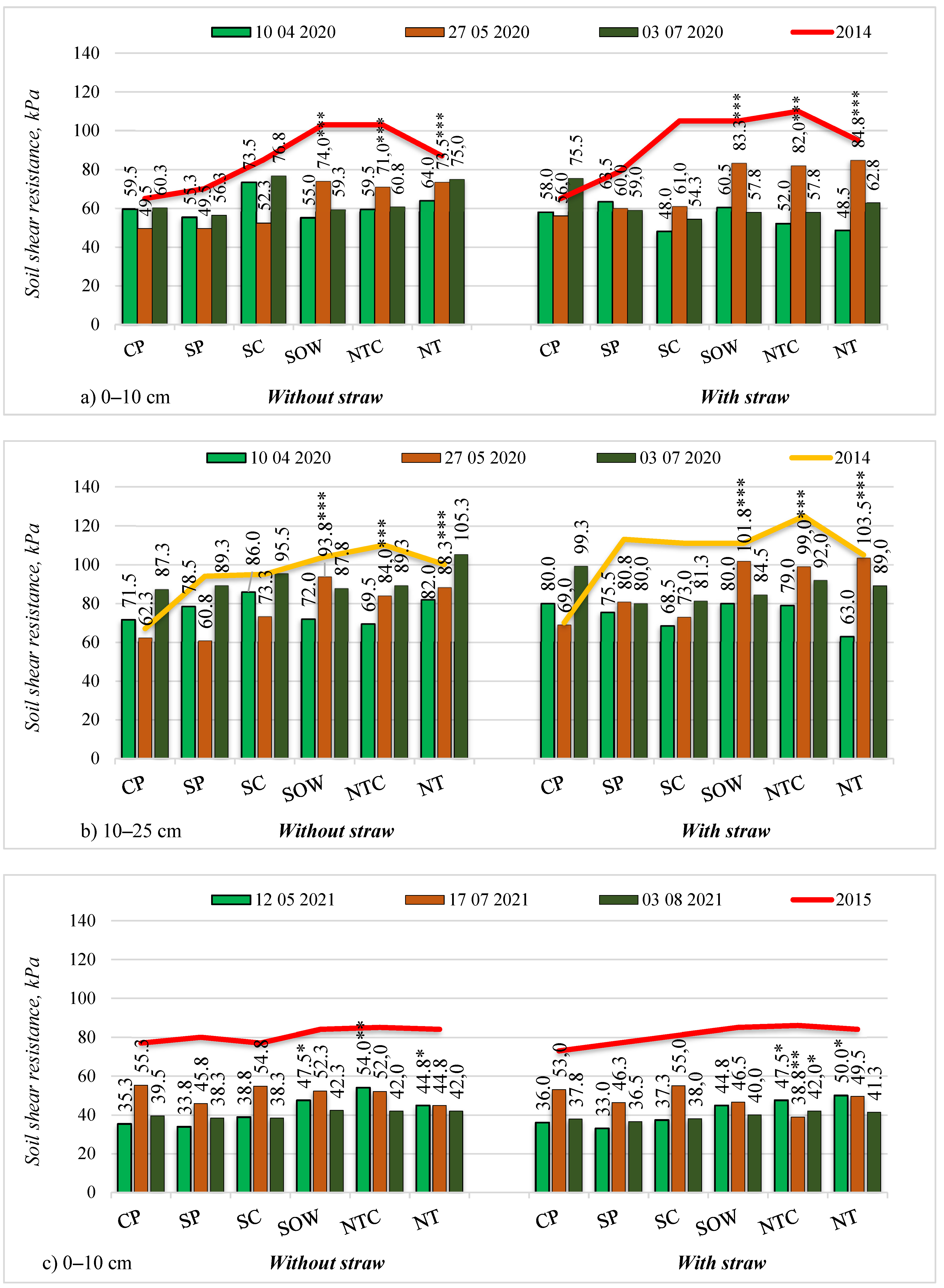

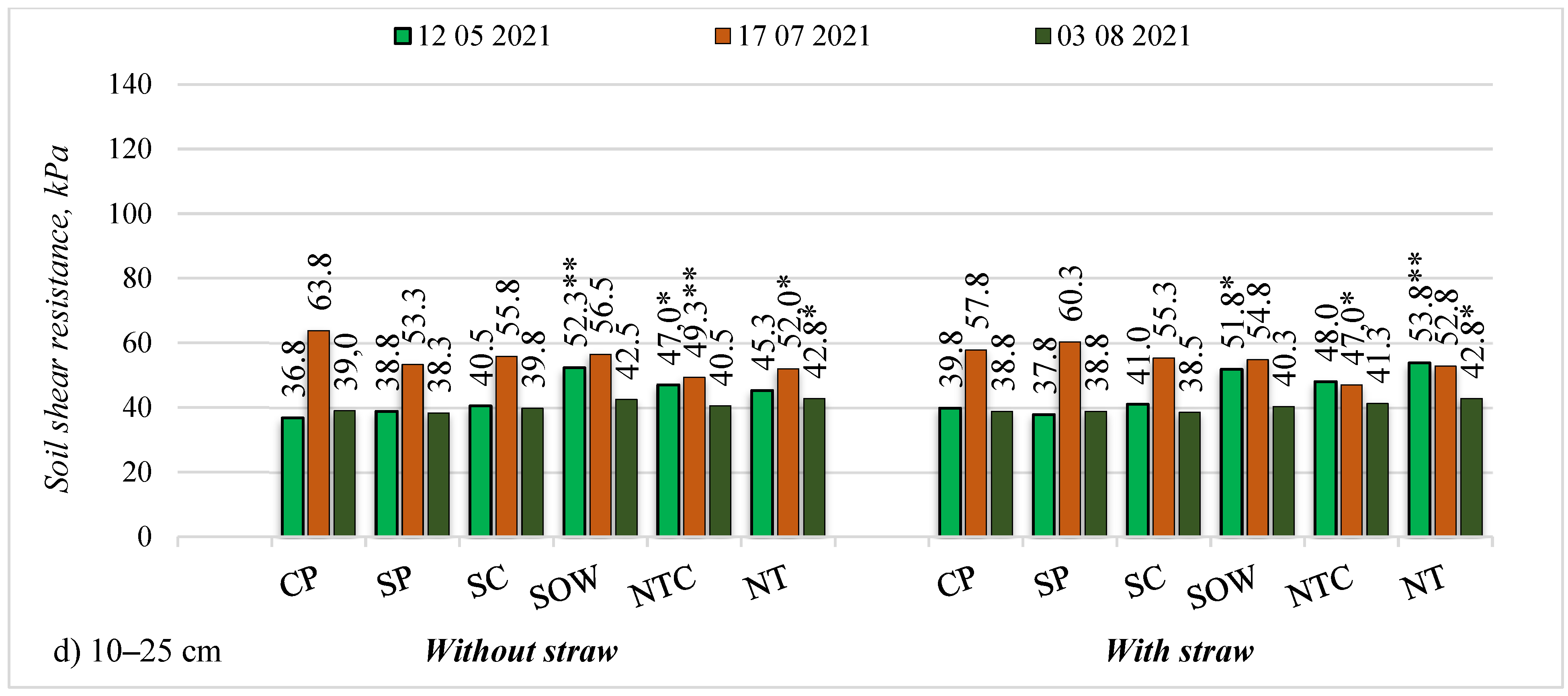

3.2. Soil Shear Resistance

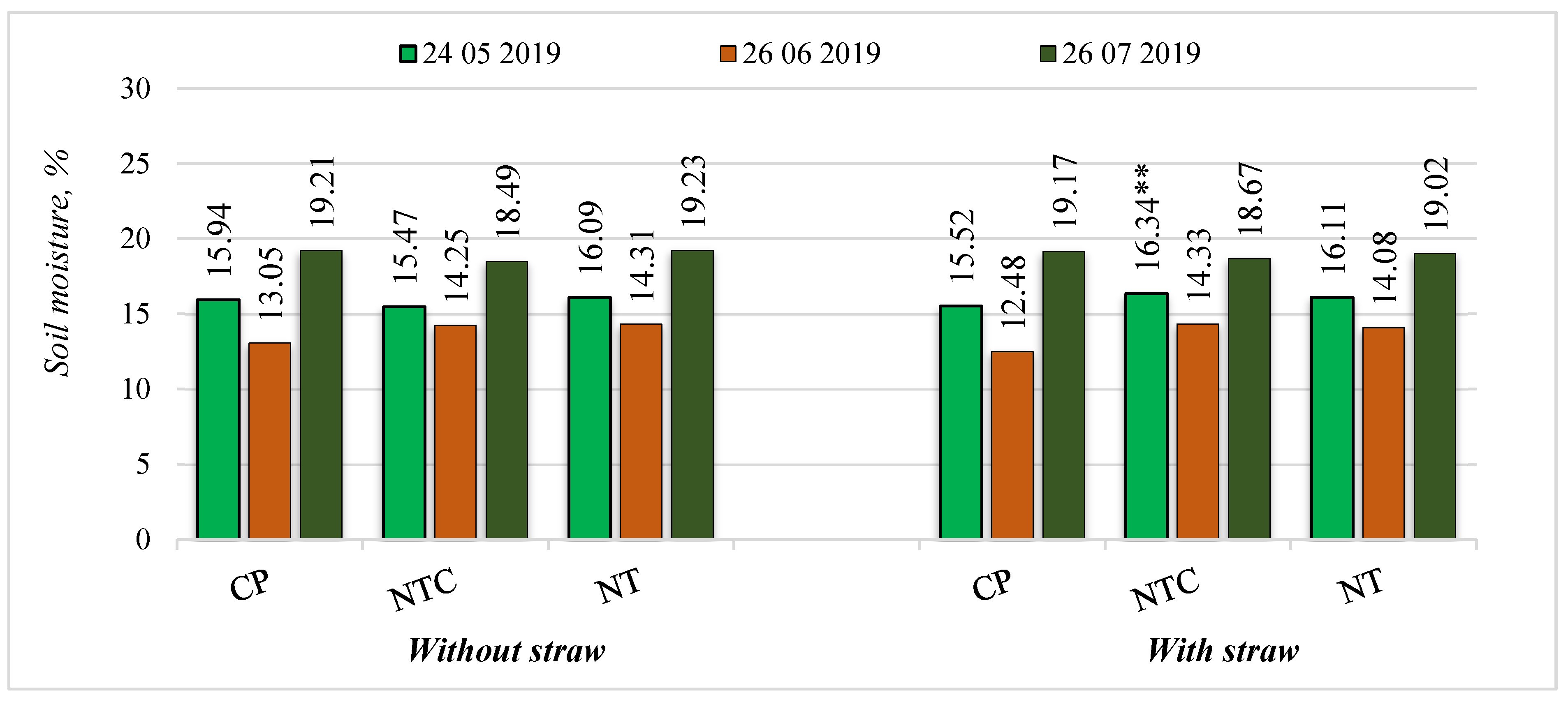

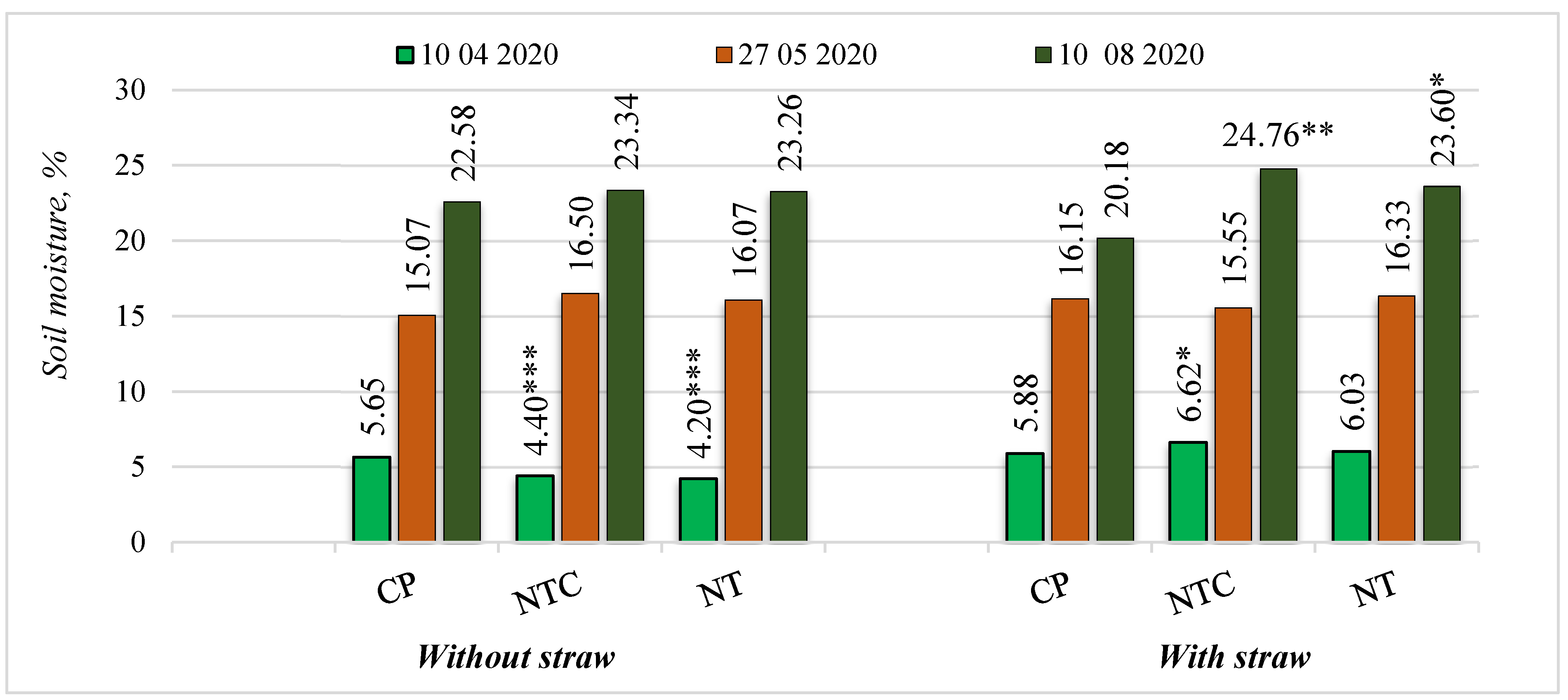

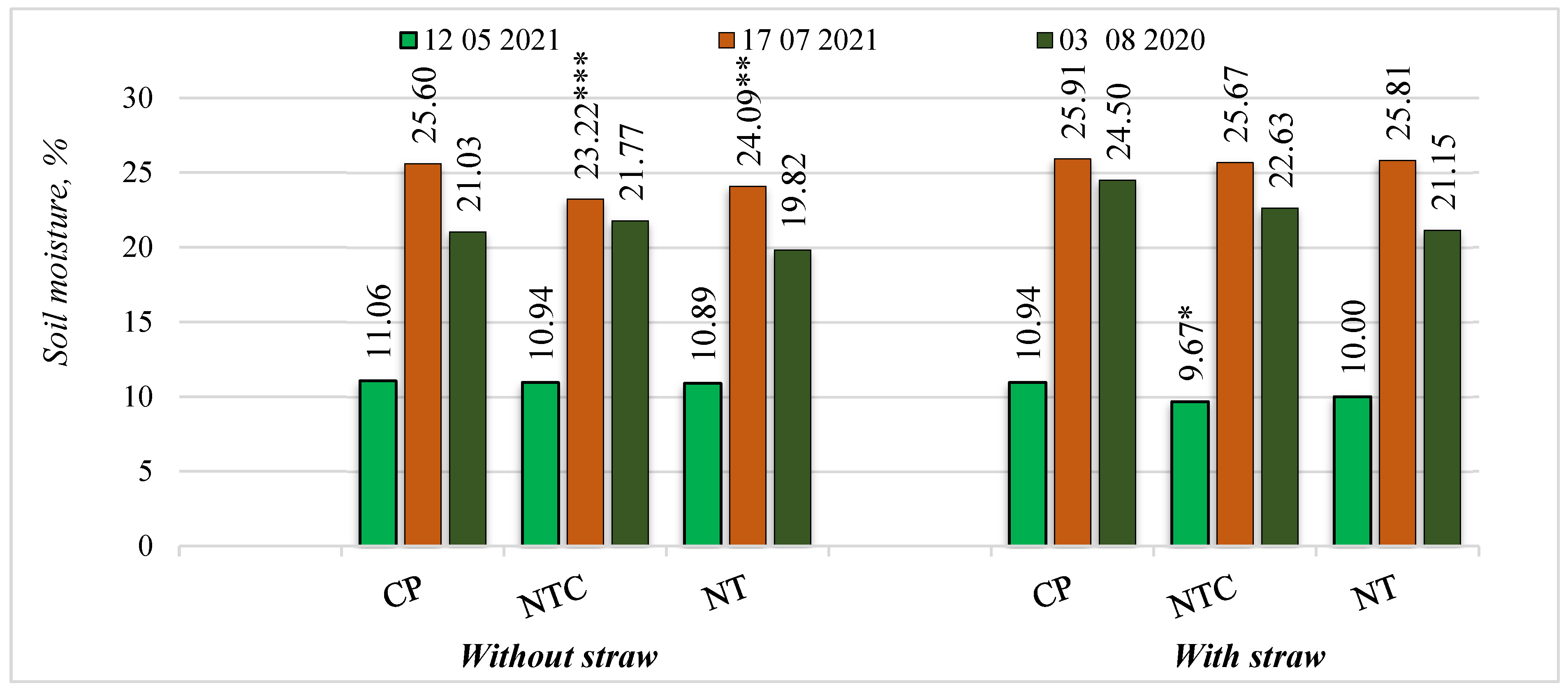

3.3. Soil Moisture

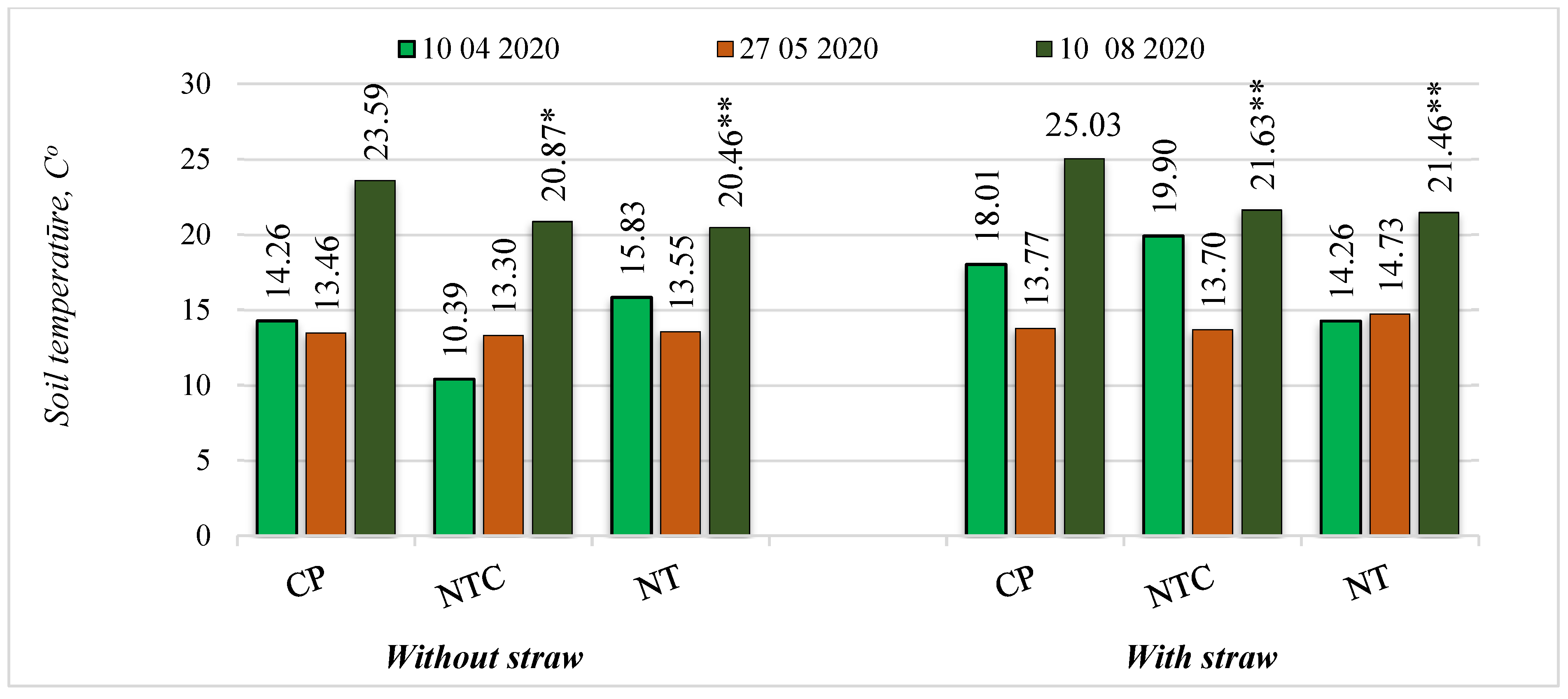

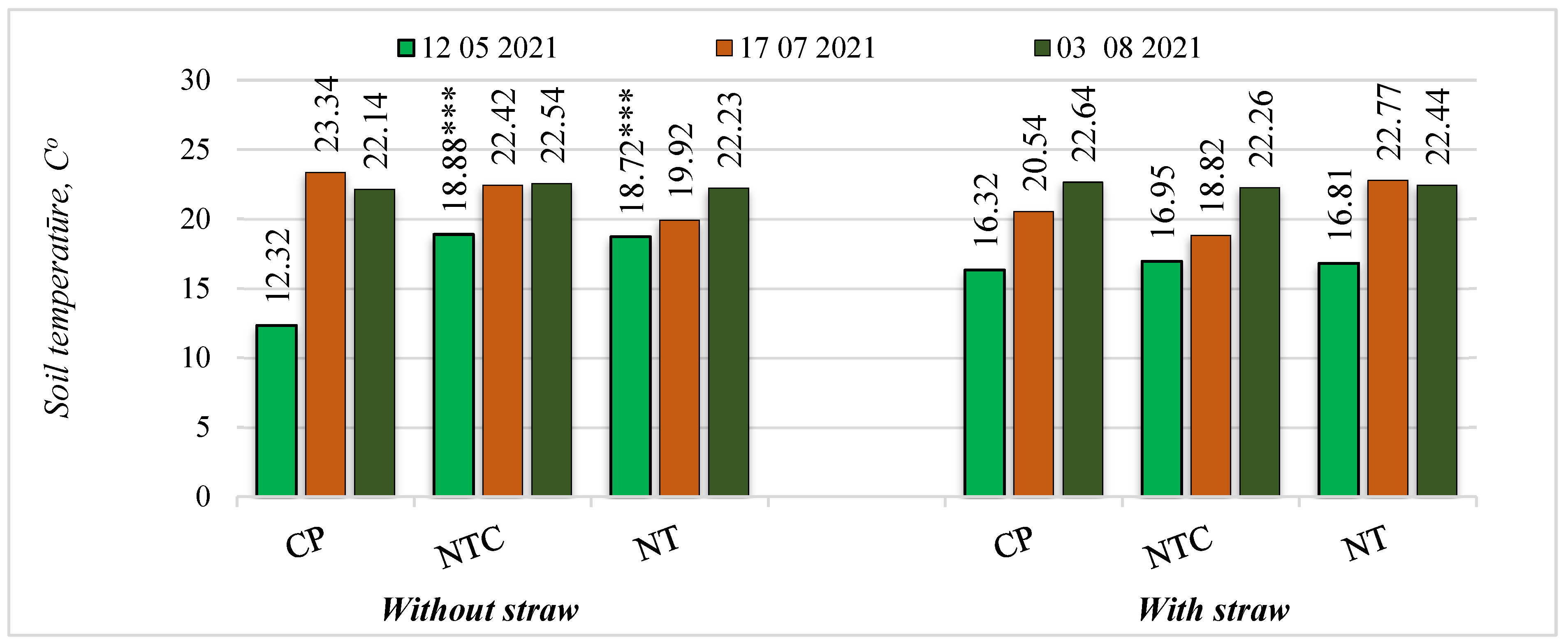

3.4. Soil Temperature

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juchnevičienė, A.; Raudonius, S.; Avižienytė, D.; Romaneckas, K.; Bogužas, V. Ilgalaikio supaprastinto žemės dirbimo ir tiesioginės sėjos įtaka žieminių kviečių pasėliui. Žemės Ūkio Mokslai 2012, 19, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Zhao, G.; Yang, Y. Impact of plant root morphology on rooted-soil shear resistance using triaxial testing. Adv. Civil Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, P.; Di Paolo, E.; Fecondo, G.; Di Fonzo, N.; Pisante, M. No-tillage and conventional tillage effects on durum wheat yield, grain quality and soil moisture content in southern Italy. Soil Tillage Res. 2007, 92, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudinskienė, A., Marcinkevičienė, A., Velička, R., & Steponavičienė, V. (2024). The effects of incorporating caraway into a multi-cropping farming system on the crops and the overall agroecosystem. Agronomy, 14(3), 625.

- Briones, M. J. I., & Schmidt, O. (2017). Conventional tillage decreases the abundance and biomass of earthworms and alters their community structure in a global meta-analysis. Global change biology, 23(10), 4396-4419.

- Skuodienė, R. The influence of primary soil tillage, deep loosening and organic fertilizers on weed incidence in crop. Žemdirbystė 2016, 103, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaneckas, K.; Sarauskis, E.; Masilionyte, L.; Sakalauskas, A.; Pilipavicius, V. Įvairių žemės dirbimo būdų įtaka dumbluoto priemolio Luvisol vandens kiekiui cukrinių runkelių (Beta vulgaris L.) pasėliuose. Žemės Ūkio Mokslai 2013, 18.

- Kateriji, N.; Mastrorilli, M.; Lahmer, F.; Maalouf, F.; Oweis, T. Faba bean productivity in saline–drought conditions. Eur. J. Agron. 2011, 35, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steponavičienė, V., Butkevičienė, L. M., Bogužas, V., Kerdokas, T. (2021). The influence of biological preparations and their mixtures on soil agrochemical properties in winter wheat. In Rural Development: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference (pp. 38-42).

- Kristó, I., Jakab, P., Irmes, K., Rácz, A., Vályi-Nagy, M., & Tar, M. (2021). The effect of soil tillage process on soil physical parameters, yiled of oil seed rape and profitability of production. Research Journal of Agricultural Science, 53(1).

- Valujeva, K., Pilecka-Ulcugaceva, J., Skiste, O., Liepa, S., Lagzdins, A., & Grinfelde, I. (2022). Soil tillage and agricultural crops affect greenhouse gas emissions from Cambic Calcisol in a temperate climate. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science, 72(1), 835-846.

- Darguza, M., & Gaile, Z. (2023). The Productivity of Crop Rotation Depending on the Included Plants and Soil Tillage. Agriculture, 13(9), 1751.

- Blanco-Canqui, H., & Wortmann, C. S. (2020). Does occasional tillage undo the ecosystem services gained with no-till? A review. Soil and Tillage Research, 198, 104534.

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J. The effects of rotating conservation tillage with conventional tillage on soil properties and grain yields in winter wheat-spring maize rotations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 263, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, M. Factors affecting soil temperature as limits of spatial interpretation and simulation of soil temperature. Acta Univ. Palacki. Olomuc. Geogr. 2014, 45, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Amare, G.; Desta, B. Coloured plastic mulches: Impact on soil properties and crop productivity. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haei, M.; Öquist, M.G.; Kreyling, J.; Ilstedt, U.; Laudon, H. Winter climate controls soil carbon dynamics during summer in boreal forests. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 024017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euskirchen, E.; Mcguire, A.D.; Kicklighter, D.W.; Zhuang, Q.; Clein, J.S.; Dargaville, R.J.; Dye, D.G.; Kimball, J.S.; McDonald, K.C.; Melillo, J.M.; et al. Importance of recent shifts in soil thermal dynamics on growing season length, productivity, and carbon sequestration in terrestrial high latitude ecosystems. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 731–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öquist, M.G.; Laudon, H. Winter soil frost conditions in boreal forests control growing season soil CO2 concentration and its atmospheric exchange. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A. Effect of low-temperature stress on germination, growth, and phenology of plants: A review. In Physiological Processes in Plants under Low Temperature Stress; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y., Schindlbacher, A., Malo, C. U., Shi, C., Heinzle, J., Kengdo, S. K.,… & Wanek, W. (2023). Long-term warming of a forest soil reduces microbial biomass and its carbon and nitrogen use efficiencies. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 184, 109109.

- Report EUR 25186 EN; The State of Soil in Europe: A Contribution of the JRC to the European Environment Agency’s Environment State and Outlook Report—SOER 2010. European Commission: Luxembourg, 2012; p. 76.

- Panday, D., Bhusal, N., Das, S., & Ghalehgolabbehbahani, A. (2024). Rooted in nature: The rise, challenges, and potential of organic farming and fertilizers in agroecosystems. Sustainability, 16(4), 1530.

- Lal, R. Challenges and opportunities in soil organic matter research. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2009, 60, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.R.; Baco, A.R. Ecology of whale falls at the deep-sea floor. In Oceanography and Marine Biology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2003; pp. 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Zhou, X., Du, C., Liu, Y., Xu, X., Ejaz, I.,… & Sun, Z. (2023). Trade-off between soil carbon emission and sequestration for winter wheat under reduced irrigation: The role of soil amendments. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 352, 108535.

- Lal, R. Carbon sequestration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Blagodatskaya, E. Microbial hotspots and hot moments in soil: Concept & review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 83, 184–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, N.W.; Slessarev, E.; Marschmann, G.L.; Nicolas, A.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Brodie, E.L.; Firestone, M.K.; Foley, M.M.; Hestrin, R.; Hungate, B.A.; et al. Life and death in the soil microbiome: How ecological processes influence biogeochemistry. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reicosky, D.C.; Lindstrom, M.J.; Schumacher, T.E.; Lobb, D.E.; Malo, D.D. Tillage-induced CO2 loss across an eroded landscape. Soil Tillage Res. 2005, 81, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaisi, M.M.; Yin, X. Tillage and crop residue effects on soil carbon and carbon dioxide emission in corn-soybean rotations. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatskikh, D.; Olesen, J.; Hansen, E.M.; Elsgaard, L.; Peterse, B.M. Effects of reduced tillage on net greenhouse gas fluxes from loamy sand soil under winter crops in Denmark. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, J.W.; Lal, R. Tillage effects on gaseous emissions from an intensively farmed organic soil in North Central Ohio. Soil Tillage Res. 2008, 98, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurevics, A. (2024). Slash and stump harvest–effects on site C and N, and productivity of the subsequent forest stand. Acta Universitatis Agriculturae Sueciae, (2024: 64).

- Dhadli, H. S., Brar, B. S., & Black, T. A. (2015). Influence of crop growth and weather variables on soil CO2 emissions in a maize-wheat cropping system. Agric. Res. J, 52(3), 28-34.

- Ruan, Y., Kuzyakov, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, X., Xu, Q., Guo, J., … & Ling, N. (2023). Elevated temperature and CO2 strongly affect the growth strategies of soil bacteria. Nature Communications, 14(1), 391.

- Steponavičienė, V., Butkevičienė, L. M., Bogužas, V., Kerdokas, T. (2021). The influence of biological preparations and their mixtures on soil agrochemical properties in winter wheat. In Rural Development: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference (pp. 38-42).

- ur Rehman, S., Ijaz, S. S., Raza, M. A., Din, A. M. U., Khan, K. S., Fatima, S., … & Ansar, M. (2023). Soil organic carbon sequestration and modeling under conservation tillage and cropping systems in a rainfed agriculture. European Journal of Agronomy, 147, 126840.

- Valujeva, K., Pilecka-Ulcugaceva, J., Skiste, O., Liepa, S., Lagzdins, A., & Grinfelde, I. (2022). Soil tillage and agricultural crops affect greenhouse gas emissions from Cambic Calcisol in a temperate climate. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil & Plant Science, 72(1), 835-846.

- Panagos, P., De Rosa, D., Liakos, L., Labouyrie, M., Borrelli, P., & Ballabio, C. (2024). Soil bulk density assessment in Europe. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 364, 108907.

- Buivydaitė, V.; Vaičys, M.; Juodis, J.; Motuzas, A.J. Lietuvos Dirvožemių Klasifikacija; Lietuvos Žemės Ūkio Universitetas: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2001; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Steponavičienė, V.; Žiūraitis, G.; Rudinskienė, A.; Jackevičienė, K.; Bogužas, V. Long-Term Effects of Different Tillage Systems and Their Impact on Soil Properties and Crop Yields. Agronomy 2024, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, W.W.; Jacobs, C.M.; Kruijt, B.; Elbers, J.A.; Barendse, S.; Moors, E.J. Carbon Exchange of a maize (Zea mays L.) Crop: Influence of Phenology. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 139, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, F.; Gonzalez-Meler, M.A.; Flower, C.E.; Lynch, D.J.; Czimczik, C.; Tang, J.; Subke, J.A. Ecosystem-Level Controls on Root-Rhizosphere Respiration. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Sun, T.; Chen, L.; Pang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, F. N and P Fertilization Reduced Soil Autotrophic and Heterotrophic Respiration in a Young Cunninghamia Lanceolata Forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 232, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiza, V., Feizienė, D., Sinkevičienė, A., Bogužas, V., Putramentaitė, A., Lazauskas, S.,… & Steponavičienė, V. (2015). Soil water capacity, pore-size distribution and CO2 e-flux in different soils after long-term no-till management. Zemdirb. Agric, 102(1), 3-14.

- Sinkevičius, A. (2023). Žemės dirbimo technologijų ilgalaikis poveikis agroekosistemų tvarumui (Doctoral dissertation).

- Zhu, L.; Liao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Bian, Q.; Zhang, Q. Prediction of soil shear Strength parameters using combined data and different machine learning models. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steponavičienė, V.; Bogužas, V.; Sinkevičienė, A.; Skinulienė, L.; Sinkevičius, A.; Klimas, E. Soil physical state as influenced by long-term reduced tillage, no-tillage and straw management. Žemdirbystė 2020, 107, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, K. L., Dang, Y. P., & Dalal, R. C. (2020). The ability of conservation agriculture to conserve soil organic carbon and the subsequent impact on soil physical, chemical, and biological properties and yield. Frontiers in sustainable food systems, 4, 31.

- Klik, A.; Rosner, J. Long-term experience with conservation tillage practices in Austria: Impacts on soil erosion processes. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 203, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairytė, M.; Stevens, R.L.; Trimonis, E. Provenance of silt and clay within sandy deposits of the Lithuanian coastal zone (Baltic Sea). Mar. Geol. 2005, 218, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudinskienė, A., Marcinkevičienė, A., Velička, R., & Steponavičienė, V. (2024). The effects of incorporating caraway into a multi-cropping farming system on the crops and the overall agroecosystem. Agronomy, 14(3), 625.

- Faqir, Y., Qayoom, A., Erasmus, E., Schutte-Smith, M., & Visser, H. G. (2024). A review on the application of advanced soil and plant sensors in the agriculture sector. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 226, 109385.

- Daly, E. J., Kim, K., Hernandez-Ramirez, G., & Klimchuk, K. (2023). The response of soil physical quality parameters to a perennial grain crop. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 343, 108265.

- Priori, S., Pellegrini, S., Vignozzi, N., & Costantini, E. A. (2020). Soil physical-hydrological degradation in the root-zone of tree crops: problems and solutions. Agronomy, 11(1), 68.

- Trabelsi, M., Mandart, E., Le Grusse, P., & Bord, J. P. (2016). How to measure the agroecological performance of farming in order to assist with the transition process. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23, 139-156.

- Mottet, A., Bicksler, A., Lucantoni, D., De Rosa, F., Scherf, B., Scopel, E.,… & Tittonell, P. (2020). Assessing transitions to sustainable agricultural and food systems: a tool for agroecology performance evaluation (TAPE). Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 579154.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).