1. Introduction

The course of human events is highly determined by words and body behaviors; and the capacity to catch their meanings may give us an insight into history.

On February 28, 2025, the presidents of USA and Ukraine Donald J. Trump and Volodymir Zelensky met in the Oval Office of the White House (

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UhFqdAZ9Xnw), but the conclusions of the meeting were very different from what hoped by Zelensky – getting help to get out of the war and the Russian aggression started on February 24, 2022. To the opposite, in this “Oval Office bullying” (so termed by the political analyst Ruth Deyermond) Zelensky got humiliated by Trump and his collaborators, who aimed to force him into accepting a peace plan favorable to Moscow. The meeting had heavy and long-lasting geopolitical consequences: it revealed the human, communicative, and political style of Trump and in some way determined the future pace of world politics.

The words uttered and the gestures, postures, facial expressions displayed in that meeting impacted on subsequent events and the interactants’ relationships, and generally changed the ways, rules and styles of communication in political affairs, as humans all over the world soon understood. But could have a foundation model caught such a relevant change?

In the last few years, Generative AI has rapidly evolved towards AI Agents – modular LLM-based systems integrated with external tools via advanced prompt engineering – then transitioning toward Agentic AI, characterized by multi-agent collaboration, dynamic task decomposition, persistent memory, orchestrated autonomy [1].

The remarkable capabilities of current AI models rely on a fundamental shift in architecture and computational scale. The Transformer architecture [2], with its self-attention mechanism, unlike previous sequential models (Recurrent Neural Networks), can process an entire input sequence simultaneously, enabling parallel training on massive datasets. This scalability was further fueled by specialized hardware, with NVIDIA GPUs (A100/H100) becoming the industry standard, while Google developed proprietary Tensor Processing Units (TPUs v4/v5p) specifically optimized for training its Gemini models [3].

The growth of these models follows the so-called Scaling Laws [4,5], stating that performance improves predictably with increases in compute, data, and parameters. The most recent frontier—and the focus of this study—is native multimodality in Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs), i.e., foundation models trained from the outset on mixed modalities (text, images, audio, video) rather than combining separate unimodal components post hoc. In this sense, Gemini is an example of a natively MLLM, pretrained on multimodal data, enabling deeper cross-modal semantic alignment between video, audio, and text. This capability can be further enhanced by Mixture-of-Experts architectures [6,7], which balance massive knowledge with inference efficiency.

The emergence of standards such as the Model Context Protocol enabling seamless interoperability and tool integration, and new capabilities and uses for foundation models [1,8,9,10], enhances hope that AI tools may also acquire sophisticated skills of discourse analysis.

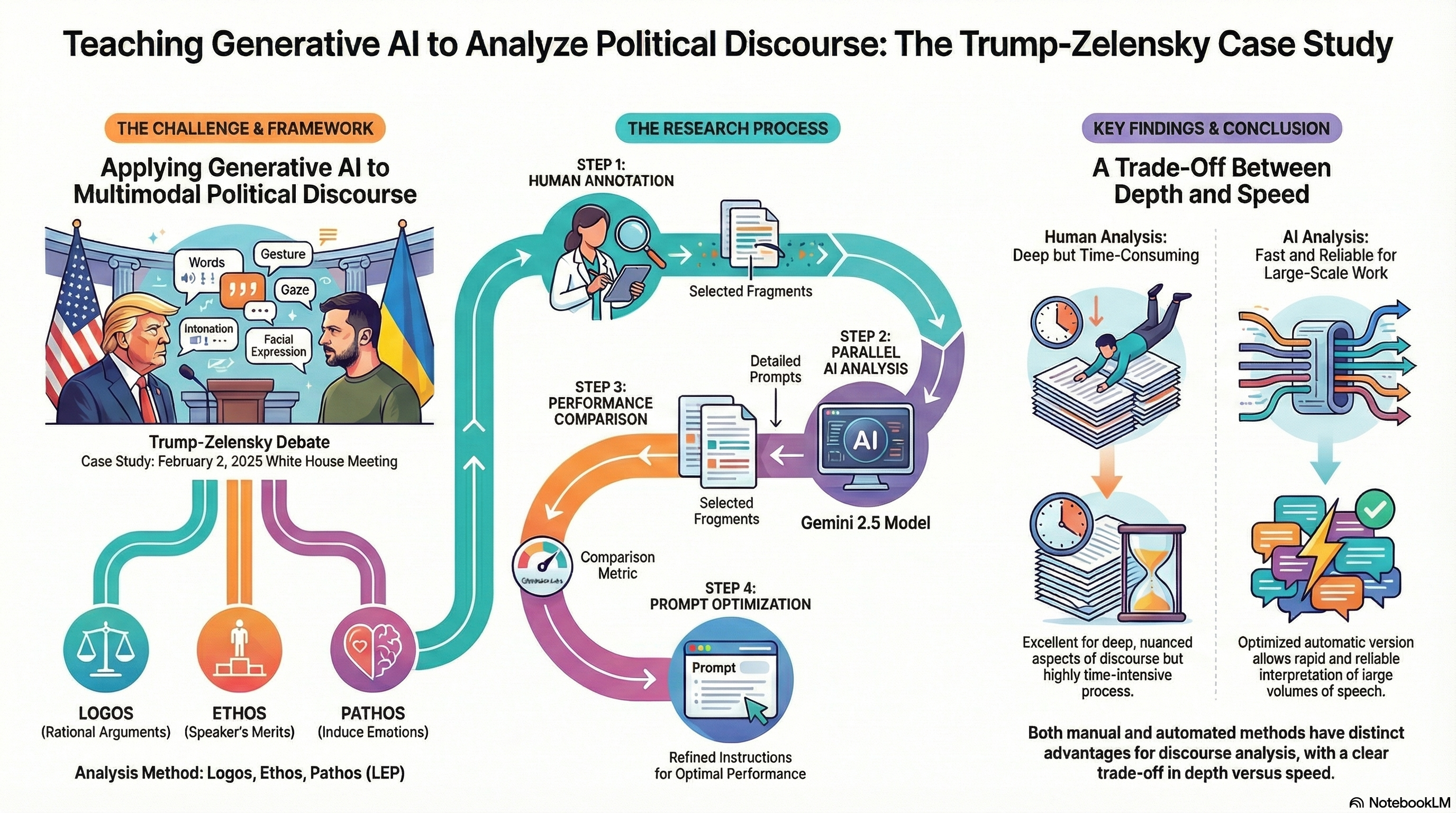

This paper, after overviewing recent works on the application of MLLM to discourse production, comprehension and analysis (Sect.2), takes the Trump-Zelensky meeting of February 28, 2025 as a case study for the analysis of multimodal speech. After recalling literature on the subtleties of body communication in that meeting in Sect.3, Sect. 4 analyses it in terms of a theoretical model of multimodal political communication, and Sect. 5 illustrates a study instructing the Gemini Pro 2.5 model in this analysis. Gemini’s analyses resulting from subsequent prompts are compared to the human’s, proposing a benchmarking model with criteria and measures to assess their discrepancies. Sect. 6 summarizes the successful results attained and highlights the effectiveness of instructing a MLLM in the proposed analysis, whereby large chunks and sophisticated aspects of multimodal discourse (so highly time-consuming when run by humans) are correctly interpreted in a fast but reliable way.

2. Related Work. Generative AI in Text and Discourse Analysis

Generative AI may be usefully applied to the qualitative analysis of discourse [11,12]. This is generally a highly time-consuming and error-prone task, and it would be very useful to have an AI carry out the transcription, categorization and quantification of speeches and debates.

After a first automatization of discourse analysis in the first years of the century, by tools for automatic qualitative analysis and detection of semantic contents, from political discourse to diaries of hospital patients (e.g., LIWC [13]), the rise of foundation models now allows for a deeper analysis of discourse, including, besides the bare count of words, also the skill to make inferences and capture implicit contents.

The first attempts at the automatic coding of discourse did not achieve standard thresholds [11]. In some text annotation tasks, e.g., identifying types of social media posts, these models outperform crowd workers [14], but in other cases they make trivial mistakes unlike humans: as goes the “Generative AI paradox”, foundation models are better at producing than at evaluating texts.

Yet, presently works on text analysis exploiting Large Language Models are flourishing. Text Analyses are conducted on textbox questionnaire responses, interview data, transcribed think-aloud data: ChatGPT is able to generate sentiment scores [15], GPT 3.5-Turbo can perform topic segmentation and inductive Thematic Analysis (TA), and single out explicit and latent meanings in qualitative data, showing capable of inferring most of the main themes with a good degree of validity [16]. Hamilton et al. [17] too find out that the human coders sometimes recognize some themes that ChatGPT does not and vice versa. Chew et al. [18], exploiting LLM-assisted content analysis (LACA) to perform Deductive coding, a qualitative research method for determining the prevalence of themes across documents, find that GPT-3.5 can often perform deductive coding at levels of agreement comparable to human coders, and demonstrate that LACA can help refine prompts for deductive coding, identify codes for which an LLM is randomly guessing, and help assess when to use LLMs vs. human coders.

Nguyen-Trung [19] introduces Guided AI Thematic Analysis (GAITA), positioning the researcher as an intellectual leader guiding GPT-4 in four stages: data familiarization; preliminary coding; template formation and finalization; and theme development. Additionally, the ACTOR framework combines different effective prompting techniques when working with GenAI for qualitative research purposes.

Socially interesting topics are confronted in the field of LLM text analysis: Törnberg [20] shows how LLMs can identify populism in political texts. Chiu et al. [21] find that with zero- and one-shot learning, GPT-3 can identify sexist or racist text with an average accuracy between 55 per cent and 67 per cent, depending on the category of text and type of learning. With few-shot learning, the model’s accuracy can be as high as 85 per cent. On a similar topic, Huang et al. [22], testing ChatGPT’s capacity to provide natural language explanations (NLEs) for implicit hateful speech detection, find that it correctly identifies 80% of the implicit hateful tweets, and that for the remaining 20% it aligns with lay people’s perceptions. Moreover, ChatGPT-generated NLEs can reinforce human perception, and tend to be perceived as clearer than human-written NLEs. Hence, the Authors raise an important ethical issue: if ChatGPT can be convincing, this might lead to the risk of misleading laypeople when its decision is wrong.

Other works focus on conversation and dialogue analysis: according to Fan et al. [23], when instructed in two discourse analysis tasks, topic segmentation and discourse parsing, ChatGPT demonstrates proficiency in identifying topic structures in general-domain, sometimes better than humans, but does not look so skilled in specific-domain conversations, and only linearly parses the hierarchical rhetorical structures, that are in fact more complex than topic structures.

Labruna et al. [24] use ChatGPT to generate and annotate goal-oriented dialogues (task-oriented, collaborative, and explanatory) in English and Italian, and in two generation modes (interactive and one-shot). Evaluating them by an in-depth analysis they conclude that their quality is comparable to dialogues generated by humans, but that the task of dialogue annotation schema, due to its complexity, still requires human supervision.

These works generally compare the coding by LLMs with previous human analyses [25], and some of them more specifically focus on the issue of prompting. De Paoli [26] proposes open-ended prompts, Fan et al. [23] use ablation studies on various prompt components, while Huang et al. [22] propose to investigate the effects of different prompt designs.

Other works [27] highlight the ethical issues, a typical theme of Critical Discourse Studies, raised by the use of LLMs for text production and analysis: the problems of power and inequality, authorship and the ownership of texts, linguistic homogenisation and the privilege of the mainstream induced by LLM usage.

Another scholar who recently explored the use of generative AI for qualitative discourse analysis is Susan Herring [12,28], a pioneer linguist who proposed CMDA (Computer-Mediated Discourse Analysis) as an approach to researching online behavior and who also produced foundational work on online (im)politeness and “flaming” [29]. Wondering whether a MLLM can be taught to perform a complex discourse-analytic task, she asked GPT-4o and GPT-o3 to code a Reddit thread using CMDA conventions and compared their output to human coding. Through a detailed metric system to evaluate their discrepancies, distinguishing types of divergence, from “better than human” to “simply wrong”, and systematic errors in politeness coding (omission, over-application, incorrect assignment of type and tone), Herring [12] showed: a. that differences between human and AI coding are frequent; that some AI errors resemble those of inexperienced students; but that AI reasoning is often sound even when the coding is incorrect; and that prompt refinements can improve performance. Herring claims that for students, LLMs can support understanding and reduce workload but risk reinforcing shallow or mistaken interpretations, and for researchers, they offer scalability and potential contributions to coding scheme development, though their output remains imperfect. She stresses that LLM-assisted CMDA must be accompanied by careful human oversight, recommending systematic verification of AI outputs, and continued direct engagement with the data [30].

A peculiar aspect of discourse analysis concerns multimodal discourse. The term multimodality may define, either: 1. written text, e.g., in social media, that contains images, videos, graphics, gifs, where the issue is how to capture the semantics not only of words, but also of images, and their relationships [12]; 2. the intertwining of speech with body communication, which analysis entails capturing, besides the meanings of words and sentences, those of intonation, gestures, facial expressions, gaze, body movements, and their reciprocal relationships [33].

Taking multimodality in this latter sense, to our knowledge no systematic study has yet applied Generative AI to the analysis of multimodal interaction. Our work aims at filling this gap by instructing an MLLM to analyze multimodal political discourse, extracting its rhetorical structure and the features of its persuasive import. The type of analysis we instruct the AI model in is the LEP (Logos, Ethos, Pathos) analysis, based on a socio-cognitive model of persuasion and multimodal communication, and its specific object is the Trump-Zelensky debate.

3. The Ten Minutes That Shocked the World. A Case Study

The Trump-Zelensky meeting of February 28, 2025, concerning the possibilities of stopping the Russia – Ukraine war, went down in history for unhinging all the rules of diplomacy and causing a heavy impact on future geopolitics. It was held publicly, in front of Trump’s important collaborators, ministers and the Vice President Vance, open to journalists’ questions, and followed a set of previous meetings, where Trump tried to tune a deal with Zelensky about the exploitation of Ukrainian raw earth, clearly implying this deal was a precondition to any further help of U.S. to Ukraine, and somehow a payment for the weapons U.S. had previously given to Ukraine.

3.1. The Meeting

The meeting (

https://youtu.be/UhFqdAZ9Xnw?feature=shared) at first follows the diplomatic protocol: greetings, ritual formulas and reminders of friendship between U.S. and Ukraine. Then Trump mentions he has spoken with President Putin, and that he also wants to bring the war to an end. Trump shows sad and worried about so many soldiers killed on both sides, hoping all that money will be put to different uses, the rebuilding. While acknowledging how brave Ukrainian soldiers were, he puts the blame of letting this war start and continue on Biden, while it would have finished immediately had he, Trump, be there at that time.

Zelensky thanks for the invitation and support, but also asks the deal to include security guarantees for Ukraine and counts on U.S. strong position to stop Putin. After proposing to share the license of Ukrainian drones in exchange for that of U.S. air defence, he goes into more detail about the Ukrainian unfortunate situation – 20.000 stolen children, mistreated prisoners – implying a very bad picture of Russians.

Trump’s reiterates his pragmatic stance, insisting about rare earths but leaving out the guarantee issue, while reminding of the dead soldiers. While seemingly kidding, compares himself to Washington and Lincoln, highlighting his activism aimed at sparing so many deaths in Russia and Ukraine. As Zelensky reminds that it was Russians who invaded their territory, and that Putin 25 times broke the deals and ceasefire, Trump magnifies his own abilities as a mediator, criticizing Biden for sending a lot of weapons and Europe for not doing enough, and blaming the hatred shining through Zelensky’s words, which does not facilitate negotiation.

Conflict escalates in the last ten minutes of the meeting (39.54 – 49.20). Vice-president J.D. Vance reminds Zelensky that the right path to peace is diplomacy as pointed out by Trump, and when Zelensky shows distrust in diplomacy, given the many agreements signed but broken by Putin, Vance complains his lack of respect and gratitude to president Trump. As Zelensky remarks that U.S. do not have the same war problems as Ukrainians just thanks to an ocean in the middle, and asks to imagine how U.S. would feel were they in their same situation, Trump, showing angry and offended, tells Zelensky that he is in no position to dictate what Americans are going to feel, that he doesn’t have the cards, and that he is gambling with World War III; he again blames his ingratitude, remarking he is running low of soldiers who, although brave, would be nothing without U.S. weapons. Finally, Trump stops the meeting sarcastically calling it a piece of great television.

3.2. Body Language and Stances in the Meeting

The Trump – Zelensky meeting at the White House became a focal point of international attention not only for its diplomatic implications but for the intense and revealing non-verbal exchange between the two leaders. According to analysts Caroline Goyder and Darren Stanton, (

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/03/01/zelensky-trump-video-body-language/),the encounter deviated sharply from conventional protocol, unfolding more like a media spectacle than a diplomatic negotiation. Goyder emphasized that the usual “courtly behavior pattern” was visibly stripped away. First, no interpreter was used, increasing the potential for tension and miscommunication, second, the evident power imbalance between Trump and Zelensky, as to both military status and geopolitical leverage, was played out nonverbally, and they embodied contrasting performance frames: the former, calm and courtroom-like, signaled control from a position of domestic stability; the latter, displaying “warrior energy,” brought urgency, military posture, and emotional intensity shaped by Ukraine’s wartime reality. Stanton observed that Zelensky’s posture shifted from engaged to defensive, particularly at Vance’s intervention, with gestures displaying frustration and a solely ego-driven communication. Trump, by contrast, deployed his classic dominance repertoire – bone-crusher handshakes, power pats, and steepled fingers. Paul Boross (

https://news.sky.com/video/what-does-the-body-language-between-trump-and-zelenskyy-tell-us-13319187) framed the event as a clash of alpha energy versus moral resilience: Trump’s wide stance, pointed gestures, and aggressive gaze were met by Zelensky’s composed presence, sincere hand movements, and steady eye contact: a non-verbal duel where Trump sought to overpower, while Zelensky aimed to project unshakable integrity and national dignity. Khyati Bhatt (

https://simplybodytalk.com/blog/trump-zelensky-body-language-analysis/) interpreted the exchange as an alpha–submissive dynamic, with Trump asserting territorial dominance through expansive postures and Zelensky exhibiting physical constriction, anxious facial expressions, appeasing gestures – a cue to a leader under pressure. Traci Brown (

https://youtu.be/yxI-8yaVsZE?feature=shared) traced the meeting’s progression from polite gestures to open confrontation, highlighting Trump’s use of the accusatory finger-point as a symbolically loaded act of aggression and Zelensky’s upward chin tilt and heart-touch as signals of moral defiance. Judi James (

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-14449261/donald-trump-white-house-smackdown-zelensky-jd-vance.html) described the encounter as a high-stakes chess match, where Trump’s physiological escalation – from flushed cheeks to commanding gestures – marked a transition from calculated authority to combative dominance, and emphasized Vance’s role as Trump’s “provocateur” igniting tension and enabling Trump to deliver the climactic verbal blows.

These expert readings agree that beneath the surface of formal diplomacy, the meeting exposed raw, performative power struggles, where every gesture, glance, and shift in posture contributed to a psychological battle in full view of the world.

This jeopardizing event, beyond analysis by political commentators, might go through a more systematic and detailed view, exploiting one of the numerous discourse analysis approaches, from classical rhetoric or pragma-linguistics to lexicographic automatic analysis. But these models, as applied by humans, are highly time-consuming, especially when annotating not only the verbal content of the interaction but also its multimodal communication; so it would be useful to instruct a MLLM how to apply one of these models.

In the following we illustrate a socio-cognitive model of multimodal political discourse, analyzing, as an example, a fragment from the Trump – Zelensky meeting.

4. A Socio-Cognitive Model of Persuasion and the LEP Analysis of Political Discourse

According to a socio-cognitive model that interprets mind, social interaction, emotion, and communication in terms of goals and beliefs [31,32,33,34,35], communication occurs when a Sender performs a verbal or bodily communicative act, that is, a sentence (speech act) or a gesture, gaze, facial expression, posture (nonverbal act), which conveys a performative of information, question, request, and a propositional content – the information given or asked, the requested action. So communicating is always an act of influence, since it asks an Adressee to do something, assume some information, or provide one.

Persuasion is a communicative action aimed at having someone do something: a form of social influence, i.e., of raising or lowering the likeliness for someone to pursue some goal [32]. A influences B when A causes B to pursue some goal GA or not to pursue some goal GB. In the peculiar social influence of persuasion [36], persuader A proposes persuadee B to pursue a goal GA by showing that bringing about GA is a means for B to achieve one’s previous goal GB. Unlike manipulation, in which B gets persuaded without realizing that someone wants to persuade him, in persuasion A does communicate to B one’s intent to influence, and finally B accepts to pursue the proposed goal not through seduction or because induced by promise, threat, or the use of force, but because B gets convinced that the goal proposed by A is indeed a means to achieve one’s goal GB. To bring about this process, the persuader exploits three different strategies proposed by Aristotle’s “Rhetoric”(325 BCE): logos (rational argumentation), ethos (the Orator’s character) and pathos (the Audience’s emotions).

The first strategy, logos, is logical argumentation: to provide pertinent information and good reasons, i.e., to highlight other goals of B which motivate or enhance B’s choice to pursue the goal GA proposed by A as a means for B’s goals.

Ethos is the strategy of enhancing trust in the persuader: we are convinced not only by what someone tells us, but also by who tells us this. Therefore, the persuader must project a positive image of oneself to elicit the persuadee’s trust and make one’s arguments more credible. B trusts A [37] when B believes s/he cannot or does not want to pursue one’s goal GB, and consequently delegates A to bring it about. But to trust A, B must believe 1. that A has the competence – intelligence, knowledge, comprehension, inference and planning skills – that are required to bring about B’s goals, and 2. that to realize B’s goals A will act in the interest of B, not in one’s own: that is, B also relies on A’s benevolence. This always holds in everyday interaction: a car seller, a dentist must be both expert and honest. But in politics, one more characteristic is required to obtain the electors’ trust and their votes: dominance, the capacity of being and showing stronger than the opponent, to exert one’s power over others, not to submit to others’ argumentations and decisions.

Political communication is generally a triangular persuasive job: in rallies and debates both politicians A and B aim to persuade the Voter V; and to have V vote for A, A must persuade that A is better than B. So politicians must display a positive image of themselves, conveying “I am more (good, smart, strong) than my opponent”. But if one (even unconsciously) intimately feels not being really endowed with such skills, one can take another route: to discredit the opponents, i.e., to diminish their image.

This is why the political orator, in speeches, debates and social media, while working on one’s own ethos, to project a positive image of oneself, also often works on the opponents’ ethos by trying to diminish their image, to delegitimate them by criticism, calumny, accusation or gossip, insult or ridicule, aiming to highlight one’s own merits and remark the others’ demerits, alternating communicative acts of self-praise and discredit.

The third Aristotelian persuasive strategy, pathos, consists in eliciting and managing the persuadees’ emotions to induce them to pursue the proposed goal. Although the appeal to emotions is considered a fallacy by argumentation theory (e.g., [38]), emotions are often and heavily exploited in political communication [39,40] thanks to their high motivating power, due to their function of monitoring the primary goals of people, and to their triggering urgent and pressing goals. I feel fear if my goal of survival is at risk; anger if someone thwarted my goal of justice; compassion if my goal of others’ well-being is thwarted; and anger triggers aggression, fear, flight, compassion, the impulse to help.

The three strategies of logos, ethos and pathos can be all exploited in persuasive discourse, including political speech [35,36]; but different speakers may employ them in different ways, relying more on rational argumentation, on the presentation of oneself or the opponent, or on the emotions they can trigger. Moreover, in their self-presentation and discredit strategy the evaluations they stress more – competence, benevolence, or dominance – can tell us something about what values are most important for them, and in the emotions they most often express or try to trigger we see which goals are most important for them. So, by carrying on a LEP analysis (Logos, Ethos, Pathos analysis) [41] of political speeches and debates, we can characterize the respective “political discourse style” of different politicians by comparing the relative frequency with which they employ the three strategies: how much they go into details of political programs (logos), or they highlight positive aspects of self or negative aspects of the opponents (ethos), or they leverage on emotions (pathos), and how their combination of preferences characterizes their discourses.

4.1. The LEP Analysis of Multimodal Political Discourse

Poggi et al. [41] presented the LEP model (LEP analysis of Political Discourse) and applied it to the qualitative analysis of four inauguration speeches delivered by three Italian Prime Ministers. The LEP analysis showed particularly fit to detect the main aspects of their personal history, their communicative style, and their political ideology. In that work, the analysis was carried on only the verbal side of each speech. But a detailed quantitative analysis inspired to the LEP model can be carried on also on the whole multimodal arrangement of speeches.

In speech the sentences produced are only a small part of what a speaker intends to communicate: communication is multimodal in that intonation and prosody, face, gaze, gesture, posture all convey meanings; and, even not considering the information unconsciously leaking from the speaker’s body behavior, such as manipulation gestures (licking one’s lips, grasping a pen), a great part of the contents borne by the body are deliberately conveyed by the speaker as functional to the transmission of the global intended meaning. In political communication too, the behavior of the body is sometimes as relevant as the verbal one, because it can confirm but also add to and complete the meanings conveyed verbally, or sometimes even possibly contradict them. A staring gaze may convey a person’s dominance, a contemptuous face can discredit the Interlocutor, a fast moving gesture can incite and transmit enthusiasm; and all these pieces of information make up the whole mosaic of a politician’s communication, with its peculiar combination of logos, ethos, and pathos. Moreover, each communicative item, whether word or bodily signal, besides its literal meaning may also convey one or more indirect meanings: presupposition, implications or other semantic contents that the Sender wants to be inferred by the Addressee.

Therefore, to provide a more complete grasp of the differences in communication style among politicians’ speeches, the LEP analysis can be conducted on multimodal communication, according to an annotation scheme where

for each verbal or bodily communicative item (sentence, prosody, gesture….) is attributed both its literal and its possible indirect meanings, and these meanings are classified in terms of Logos Ethos and Pathos. This work is the first case in which a Multimodal LEP analysis was exploited. Let us see (

Table 1) how fragments of the Trump – Zelensky meeting can be analysed in terms of this model.

Table 1 shows the annotation scheme of the Multimodal LEP analysis. In the first three columns we write who is the Sender of the analyzed communicative item (Time & Sender, col.1), the modality of that item (Modality, 2), and the transcription of the verbal signal or a description of the bodily signal (Signal, 3). In the following two columns we write the semantic analysis of the signal: its literal meaning in col.4 – e.g., a verbal translation of the gesture or gaze under analysis –, and its indirect meanings (if any) in col. 5. Columns 6 through 11 contain the classification of the communicative moves perfomed by the meanings in cols. 4 and 5: whether barely ritual (col.6), or bearing on logos (7), on ethos – the Sender’s and their side’s merits (8), the Opponents’ demerits (9) – or finally on pathos: the emotions expressed by the Sender (10) and ones s/he wants to elicit in the Audience or the Opponents (11).

Here for example Trump, at minute 13.38 (Col.1) says (Verbal modality, col.2): “There has never been a first month like uh like we’ve had (col. 3), an informative sentence conveying (Literal meaning, col. 4) “I did many things in my first month as a President”, which however implies (indirect meaning, col. 5) an evaluative information: “I am better than all other Presidents”, a self-praise about competence (C, col.8, Ethos our merits), and displays pride (expressed emotion, Pathos col. 10). In the gaze modality (subsequent line, col. 2) Trump at the same time of his sentence looks forward at the camera and the Audience, conveying (literal meaning, col. 3) “I address you all” (col.4) that implies “I am confident” (5), so expressing the emotion of self-confidence (col. 10).

At time 13.52 Trump’s requestive act think of the parents whether they are Russian or Ukraine (col.3) means “you should feel compassion for both Russian and Ukrainian parents” (4), but indirectly implies informative acts (5) “I am neutral, I do not take sides for Ukraine”, further indirectly conveying “this is how to make a deal”, which again highlights the evaluative information “I am skilled in making deals”. The first implication is a communicative act of Logos (col.7) but also conveys Trump’s own Benevolence (8), while by the other two implications he again self-praises his own Competence; and the general meaning of the verbal act tries to induce compassion in the Audience (col.11). At the same time, his head-shake (col.3) means “no no” (4), implying “we must stop this tremendous death” (i.e., so many people dying) (5), a requestive act of Logos (7), while by gaze (2) his squinting eyes (3) perform an informative act of expressing sorrow (10) in order to induce compassion (11).

The very words “whether they are Russian” elicit the (only bodily) reaction of Zelensky who, at the same time 13.52, in the head modality (col.2) “Turns face rightward (the opposite direction of Trump)” (3), meaning “I do not want to hear him while saying so” (4), conveying the implication “I do not agree with Trump” (5): an Ethos move discrediting PS (the Present Speaker Trump) (col.9) for lack of Benevolence (-B). At the same time, Zelensky’s mouth (2) “lowers left corner” (3), meaning “I feel disgust for Russians” (4), implying “Russians are evil, they do not deserve compassion”, hence “I do not agree with Trump” (5), which casts discredit (col.9) for a lack of Benevolence on both Russians (Third Person, TP) and Trump (PS); and by expressing disgust (10) tries to induce the Audience not to feel compassion for Russians (11).

These classifications of communicative acts can be quantified by computing how many of them fall in each class, and how many are performed in each modality: this outlines a “profile” of each interactant in the fragment, somehow their communicative style. For example, from

Table 1. it results that Trump performs 1 verbal and 1 head act of logos, 2 verbal acts of self-praise for Competence and 1 for Benevolence, 1 verbal act expressing pride, by gaze he expresses 1 time self-confidence and 1 sorrow, and induces compassion by 1 verbal and 1 gaze act. Zelensky conveys others’ lack of benevolence by head and mouth, and by mouth expresses disgust and tries to induce lack of compassion.

From these counts, Trump appears a person quite satisfied with himself, inclined to strive for the others’ good, and Zelensky as a bittered person, seeing others as enemies. But this is the profile resulting from these few lines only: in many other cases, Trump displays all his narcissism, his primary interest in money and power, his contempt and criticism for Biden’s stupidity, and his attempt to induce humiliation in Zelensky; whereas Zelensky shows his firmness in confirming Russian responsibility for the war (-B), but also fairness to Europe who always backed his action (B), and tries to elicit worry even in Trump and Vance for Putin’s possible action toward Europe and USA.

4.2. Can Generative AI Run a Multimodal LEP Analysis?

As may be clear from this example, the LEP analysis of multimodal speeches and debates is very effortful and time-consuming: brief fragments of communication require hours for annotation and classification of all communicative signals. A challenging task, then, right for MLLMs.

5. Instructing Gemini 2.5 Pro in the LEP Analysis of a Political Debate

To test this hypothesis, we designed a study aimed at assessing if and how a MLLM can be instructed to categorize a multimodal political discourse in terms of the LEP analysis. As a case study we selected the Trump-Zelensky debate, and as the MLLM to instruct we used Gemini (Pro 1.5/2.5) via Google AI Studio, given its specific technical advantages crucial for political discourse analysis. First, Gemini stands out as a natively multimodal model with an extensive context window (up to 2 million tokens), allowing it to process the entirety of the Trump-Zelensky meeting without fragmentation. Crucially, Google AI Studio offers a unique feature: direct YouTube integration. Unlike other MLLMs that require complex pre-processing (downloading videos, extracting frames, or transcribing audio separately), Gemini can ingest and analyze YouTube videos directly. This capability allows the model to “watch” and “listen” to the debate in its original format, processing non-verbal cues (prosody, facial expressions) alongside the verbal transcript in a unified inference stream. This technological affordance is essential for applying the LEP framework to the interplay between words and body language.

Given the length of the meeting (49 minutes), before feeding Gemini 2.5 Pro pieces of the dialogue and the instructions on how to analyze it, it was necessary to select only some fragments of the Trump-Zelensky meeting. Such selections required a process in more phases, that combined human and AI contributions.

The first phase required a thorough human analysis of the meeting, the second included: a) the construction of prompts to make the model analyze fragments of the meeting, b) the comparison of its analyses with the human’s, and c) the optimization of a final prompt, aimed at making the model as much or even more expert than the human in the LEP analysis.

5.1. Method

The human analysis of the debate included three steps.

Debate transcription: the integral video of the meeting was transcribed through the tool Turboscribe (

https://turboscribe.ai), resulting in a faithful transcription of the dialogue, also encompassing pauses, overlaps and interruptions, timing, and distinction of different speakers, thanks to the tool’s advanced skills of vocal recognition.

Fragments selection: after thorough reading, the most significant fragments of the meeting were selected for a whole detailed LEP analysis: namely,

the fragment from minute 13.38 through 13.57 was chosen to provide a detailed model of analysis within the prompt to feed to Gemini 2.5. Pro. Here Trump urges about making a deal, given the “tremendous death” taking place, and invites the Audience to think of the parents of the dead soldiers, both Russian and Ukraine. Zelensky first reacts with physical signs of tension to Trump’s (for him) excessive equidistance from the two contenders, and finally blurts out “They came to our territory!”.

This fragment is interesting mainly as a test of whether the GAI model decides to represent and classify also the bodily communication delivered by Zelensky, who in this case is but the Interlocutor, not a Present Speaker.

three fragments from the last 10 minutes of the meeting, 38.18 through 49.22. This is the most crucial part of the debate: the level of aggression of Trump and Vance towards Zelensky raises, jeopardizing his possible previous expectations about the conclusion of the debate, and his hope to get some help for Ukraine from the USA. It is also the most widely discussed, commented and viral part of the meeting spread on the social media. These are the three fragments analyzed:

-

(39:14) Trump:

I’m aligned with the world and I want to get this thing over with. You see the hatred he’s got for Putin. It’s very tough for me to make a deal with that kind of hate. He’s got tremendous hatred and I understand that, but I can tell you the other side isn’t exactly in love with, you know, him either. (39:31)

Here, Trump tries to shift the blame for the failed agreement onto Zelensky, and does so also exploiting an ironic euphemistic understatement; the fragment then provides a chance to test Gemini’s skill to catch indirect meanings and rhetorical figures.

-

(40:33) Zelensky:

Sure. Yeah. Yeah. Okay. So he occupied it, uh, our parts, big parts of Ukraine, parts of East and Crimea. Uh, so he occupied it on 2014. So during a lot of years, I’m not speaking about just Biden, but those time was Obama, then president Obama, then president Trump, then president Biden. (40:58)

This excerpt shows Zelensky while rattling off facts, years, and names to explain the context without controversy, thus presenting him as consistent, rational, and respectful, but also precise and strategic. We chose this to test Gemini’s knowledge and skill to take geopolitical issues into account.

-

(44:45) Trump:

You’re not winning. You’re not winning this. I you have a damn good chance of coming out.

(44:50) Zelensky:

Okay. Because the president we are staying in our country, staying strong from the very beginning of the war. We’ve been alone and we are thankful. I said thanks.

(44:58) Trump:

You haven’t been in this cabinet. We gave you the president three hundred and fifty billion dollars. We gave your military equipment. Your men are brave, but they had to use our military. (45:10)

This last exchange is relevant for the level of aggression reaching white heat, with Trump’s attempt to humiliate Zelensky and pretend his gratitude and submission, and Zelensky defending the dignity and legitimacy of his struggle: a test for Gemini’s skills in detecting, among others, expressed and induced emotions.

Humans’ LEP Analysis of three fragments: three of the Authors provided a qualitative analysis of the three selected fragments transcribing, for each interactional move, the verbal and nonverbal signals, and classifying them in terms of Logos, Ethos, Pathos. The annotations were carried on independently and then discussed together by finally finding an agreement on possibly divergent descriptions or classifications. This first human analysis was a basis for reference and comparison with Gemini’s analysis.

The second phase, MLLM’s analysis, included:

Prompt construction and MLLM’s analyses

Two distinct prompts – a “synthetic prompt” and a “detailed prompt” – were fed to Gemini 2.5. Pro asking to analyze the last 10 minutes of the meeting.

The “synthetic prompt” simply requested the MLLM to annotate, for each verbal expression, gesture, posture, or modulation of voice, 1. the minute of occurrence, its 2. literal and 3. indirect meaning (including implications, subtexts, possible strategic or diplomatic interpretations), its 4. Ritual meaning, i.e., the role of the phrase or gesture within the formal and informal communication dynamics of a political debate, 5. classification in terms of logos, ethos (our merits and their demerits), and pathos (emotions expressed - e.g., anger, confidence, irony, frustration, hope - and to be elicited - e.g., fear, trust, indignation, compassion). The prompt also solicited to highlight any discrepancies between verbal and non-verbal language. It finally asked to present the results in the form of a table, with a column for each of the listed criteria (see

Supplementary Materials, 1. Synthetic Prompt).

The “detailed prompt” guided the MLLM step by step describing the bulk of the LEP analysis, incorporating a “Gold Standard” human annotation (fragment 13.38-13.57) as a reference example [42] (see

Supplementary Materials, 2. Detailed Prompt).

The two prompts were fed to the MLLM and the two respective analyses were recorded and compared.

Comparison of the Analyses Stemming from the Two Prompts

The analyses resulting from the two prompts are quite different. The “synthetic” prompt shows some interesting strengths. First, the MLLM clearly identifies the function of portions of discourse as opening, closing, contrast, or stakes raising, and the global scheme of the meeting is quite clearly portrayed, providing a good basis for a general interpretation of the event. But also, more interestingly, Gemini shows a fair grasp of the context and of the political and rhetorical implications of the signals. E.g., it captures:

-

Indirect meanings

Gemini catches Trump’s indirect meaning when it identifies that his reference to Zelensky’s “tremendous hatred” (39:22) for Putin is an indirect blame. It notes: “Shifts potential blame for negotiation failure onto Zelensky’s emotional state. Suggests Trump is the rational actor hindered by emotion”, thus recognizing Trump’s use of emotional framing to obscure responsibility, a sophisticated rhetorical strategy where the literal meaning (Zelensky hates Putin) masks the pragmatic implication (Zelensky’s emotions are an obstacle to Trump’s deal-making).

-

Trump’s Self-Presentation as a Mediator.

As Trump claims “I’m aligned with the world... I want to see if we can get this thing done” (39:14), the analysis captures: “Reasserts his primary focus is deal-making and resolution above taking sides. Emphasizes his role as a facilitator for broader resolution”, recognizing that Trump is employing strategic ambiguity – appearing neutral while simultaneously establishing his authority as the problem-solver.

-

Hidden presuppositions and manipulative moves.

A particularly striking exchange demonstrates Gemini’s ability to identify manipulative framing. Trump’s statement “You’re playing cards... you’re gambling with the lives of millions of people” (43:53) employs a metaphorical escalation that the MLLM correctly parses: “Trump escalates the metaphor to accuse Zelensky of recklessly endangering lives. Turns Zelensky’s situation into a high-stakes gamble he is losing without US help.” This reveals the MLLM’s recognition that Trump is exploiting the tragic situation (death of Ukrainian citizens) to reframe Zelensky’s negotiating position as irresponsible gambling. The hidden presupposition is: “Zelensky’s refusal to make concessions will cause Ukrainian deaths.”

-

Manipulative exploitation of “gratitude”

The MLLM correctly identifies the exploitation of gratitude as a power dynamic. When Vance blames Zelensky for not showing gratitude and explicitly pretends it, the analysis notes: “Vance attempts to reinforce the narrative of Zelensky’s ingratitude by demanding a specific, performative act of thanks... Zelensky pushes back, claiming prior thanks.” The MLLM identifies how thanking Trump serves an instrumental political function: it would constitute public acknowledgment of dependency and validate Trump’s narrative of American generosity. By demanding this ritual performance, Vance (and implicitly Trump) seeks to establish a hierarchical relationship where gratitude becomes a form of subordination.

Despite these brilliant performances, the output of this first prompt is lacking on the microanalytic side, which is the bulk of the LEP analysis. Here are some of its flaws:

the MLLM’s Table lacks some relevant columns: it does not distinguish the signals by modality, not specifying verbal, vocal or other; no marking of the signals opening and closing the interaction; the category Ethos does not set apart “our merits” and “their demerits”, nor does Pathos distinguish expressed from induced emotions;

the analysis mainly takes verbal and vocal behavior into account; only some gestures and postures are quoted, while face, eyes and body are almost never described;

the Interlocutor’s behavior concomitant with the Sender’s is not taken into account, thus lacking any analysis of the interaction and bodily or vocal response of the Interlocutor, e.g., its signals of acceptance or disagreement.

the analysis fails to classify the analyzed signals in terms of the LEP categories, such as “Pathos–Disgust”, “Ethos–Competence” or the like, and is confined to a set of discursive descriptions not systematically coded. This prevents any kind of computation and quantitative comparison of the assessed phenomena.

More generally, the output generated based on the “synthetic” prompt looks more like a discursive interpretation than a detailed semantic/interactional analysis of the fragment.

Coming to the “detailed prompt”, the output is more complete and correct than the former, resulting in a Table strictly complying with the proposed criteria and containing a fairly thorough LEP Analysis. Yet, since the prompt was long and complex, the 10 minutes were split into six segments, each time providing the MLLM with the same prompt and asking to resume from the preceding segment. This iterative approach [43] allowed the model to maintain context fidelity across the timeline, though it occasionally led to fragmentation: Gemini omits pieces of dialogue or stops just at key points, wasting the logical continuity and coherence of the analysis. Further, like with the synthetic prompt, it only analyses the Speaker’s communication, overlooking the Listener’s reactions. Moreover, sometimes it fills in the column concerning Pathos some mental states that are not strictly emotions, such as “pragmatism”, “determination”, “autonomy”. Finally, since a quantitative Table was not displayed in the prompt, Gemini issues different, sometimes ineffective, forms of schematization. Only the analysis of Segment 5 is close to the expected model, with better clarity of classifications and higher adherence to the LEP format.

Despite these problems, the MLLM’s analysis shows good levels of interpretative inferences, sometimes capturing the rhetorical and strategic implications of the analyzed discourse, for instance highlighting attempts to shift responsibility, to mark superiority or deference, or to build an ideological frame of legitimization for one’s discourse.

5.2. Benchmarking Multimodal Reasoning. A Model to Evaluate an MLLM’s LEP Analysis

While traditional benchmarks like MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) test general knowledge [46], evaluating a model’s ability to interpret complex visual dynamics requires newer standards. Benchmarks such as MMMU (Massive Multi-discipline Multimodal Understanding) [47] and MathVista [48] have set the bar for visual reasoning. However, analyzing political rhetoric involves subtle socio-emotional intelligence that standardized tests often miss [49,50]. In this study, we made a first attempt to propose one.

We built a benchmarking model aimed to assess the similarities and discrepancies between human’s and MLLM’s analyses by comparing them according to specific criteria of evaluation and finally rating the AI’s performance.

In our comparison model (

Table 2) three distinct Sections on subsequent lines respectively compare three aspects of the Multimodal LEP analysis: Signal, Meaning, Classification.

Table 2 shows the comparison between the two annotations of a same fragment by the Human and the AI, distinguishing them into three Sections. Section S (Signal, first 3 lines of the scheme) compares MLLM’s annotations of the first three columns of the LEP scheme (in

Table 1 above, col.1 Time & Sender, 2. Modality, 3. Signal) with ones agreed upon by the three human annotators (

Table 2, col. 2 Human), to assess if the AI (col. 3) correctly identified the type of signal (verbal, vocal, gestural…), the Sender and the exact minute. Section M (Meaning) compares columns 4 and 5 of

Table 1 (Literal and Indirect Meaning), to assess if the AI caught the signals’ meaning, but also the implications that can be inferred from them. Section C (Classification) compares Human and AI as to columns 6 through 11 of

Table 1, to assess whether the meanings extracted received the same classification by H and AI in terms of the LEP categories: Ritual, Logos, Ethos (Our Merits and Their Demerits), and Pathos (Expressed and Induced Emotions).

In all three Sections of

Table 2, the comparison goes across 6 columns: in col.1 we write which is the item compared, whether Time, Sender, Modality, or signal; in 2 (Human), the human’s annotation, in 3 (AI) the MLLM’s annotation as instructed by the optimized prompt, for the same line and column of the human’s analysis; Col. 4 (Comparison) contains the result of the comparison between the values in columns 2 and 3, coded according to the coding system below;

I (Identical): AI detects exactly the same value as Human (H)

A (Absence): H detects the value, AI does not

PA (Partial Absence): AI detects part of the correct value, but omits other aspects

R (Redundancy): AI detects a value H did not detect

PR (Partial Redundancy): AI detects something more than H, and partially coherent

D1 (High Discrepancy): both AI and H detect a value, but very different between them

D2 (Minor Discrepancy): both detect a value, with small or only formal differences

Column n.5 (Evaluation), except for cases classified as “Identical” in Col 4, contains a qualitative evaluation of the difference assessed in col.4, trying to determine if AI’s annotation is a more or less relevant error, or even a better choice than the human’s:

W (Wrong): AI makes a mistake (e.g., it misses an important value or adds an inappropriate one).

LR (Limited Relevance): AI makes a light or marginal error: the value can be considered either not so relevant or opinionable.

BC (Better Choice): AI gives a better or more correct value than did H.

NR (Not Relevant): the discrepancy between AI’s and H’s value is not relevant for the analysis

Column n.6 (Rating) writes a numeric score attributed to the evaluation of Col.5, allowing one to quantify AI’s mistaken and correct analyses; each combination “Comparison + Evaluation” is converted into a positive or negative numeric score that measures the accuracy and pertinence of AI’s annotations.

Table 3.

Comparison, evaluation, and rating.

Table 3.

Comparison, evaluation, and rating.

| 4 Comparison |

5 Evaluation |

6 Rating |

| A (Absence) |

Wrong Choice |

-2 |

| A (Absence) |

Better Choice |

+2 |

| PA (Partial Absence) |

Wrong Choice |

-1 |

| R (Redundancy) |

Better Choice |

+2 |

| PR (Partial Redundancy) |

Wrong Choice |

-1 |

| D1 (High Discrepancy) |

Wrong Choice |

-2 |

| D1 (High Discrepancy) |

Better Choice |

+2 |

| D2 (Minor Discrepancy) |

Not Relevant |

0 |

| D2 (Minor Discrepancy) |

Better Choice |

1 |

| I (Identical) |

Good Choice |

1 |

For instance, if H’s analysis goes (

Table 2, col. 2)

Slightly raised pitch, faster pace and the AI’s is

High pitch, stressed tone on “hatred”, it counts as a minor discrepancy (D2, col. 4), but AI’s is a Better Choice (BC) than H’s, so the Rating is 1 (col.6).

5.3. Results and Discussion

The sum of the final scores in all three Tables (Signal, Meaning, Classification) allows us to assess whether AI’s output is superior, inferior, or equivalent to human analysis, further providing a detailed analysis of the nature and quality of the discrepancies detected.

In general, in this benchmarking the annotations concerning the Signal (Section S) show a good level of accuracy of AI in associating the signals to the right time frame and to the Sender, with a fair amount of correspondences classified as “Identical”. Yet some cases of “Absence”, mainly gaze items or micro-expression omitted by AI, carry various “wrong” evaluations negatively impacting on the final score. Some cases of “partial absence” or “partial redundancy” are probably due to AI’s tendency to summarize or expand the perceived signals too much. All in all, AI looks fairly skilled in perceiving the main signals, but not so much in detecting nonverbal signals and precise time segmentation.

Section M (Meaning) reveals quite a high performance of the MLLM in capturing the literal and indirect meanings of the two interactants: indirect meanings, including allusions, presuppositions, and implicatures, are quite precisely detected, even resulting in a significant amount of “better choices”, with AI’s interpretations often more effective and synthetic than H’s. For instance, concerning Indirect Meanings, AI shows a superior ability to identify the speaker’s communicative intent, achieving a “Better Choice” (BC) classification in several key instances. A notable example in

Table 2 is at Line 3 of Section M (Verbal), where H’s analysis fails to provide a full interpretation, while AI offers a highly synthetic and effective one: “I am benevolent enough to understand, but competent enough to see the bigger picture.” In a similar case, comparing the Indirect Meaning of a Gaze item, AI correctly interprets a sign of surprise as an underlying challenge: “I am challenging your characterization of me.” Furthermore, AI excels in providing synthetic and more descriptive literal interpretations: for a Literal Meaning of a Gesture H simply noted “Him” by H, whereas the AI interprets as “I am balancing two opposing parties”, providing the “Better Choice”. Such cases confirm that AI was particularly successful in translating subtle communicative cues into clear, concise, and contextually rich interpretations.

The small amount of “wrong” and the high amount of “identical” and “limited relevance” cases point to a fair skill of AI to catch pragmatic nuances of the interaction. Only where, as found by Section S of the comparison, the signals was not detected, this absence impacts on the global interpretation, resulting in a low score.

Section C (Classification) of the comparison Table assesses the last and most relevant aspect of the analysis: AI’s capacity to correctly classify the communicative moves as Ritual, Logos, Ethos (Our Merits and Their Demerits), and Pathos (Expressed and Induced Emotion). Here Gemini 2.5 Pro shows mixed results. It is very skilled in recognizing expressed and induced emotions, even singling out some like compassion, worry, anger, annoyance. In the Logos category, it often correctly finds out logical elements, even if sometimes too generic ones. The classification of the interactants’ Ethos moves, instead, gives contrasting results: Gemini distinguishes positive from negative judgments, but does not always catch the criterion of the judgment, e.g., competence vs. dominance. Major flaws occur in the category Ritual, which is often omitted. A final problem is that AI often does not attribute any LEP category to the Interlocutor’s nonverbal signals, which classification instead is sometimes relevant for the LEP analysis.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the comparison and evaluation of AI’s vs. H’s performance.

Notwithstanding a fair number of “Identical” and “Minor Discrepancy” cases, very often do the two annotations yield distant results. Yet, beyond revealing formal discrepancies between AI and H, this does not distinguish them from a qualitative point of view: e.g., a case of Absence may be a bare omission, or else instead a sensible choice of AI’s, if that signal is in fact irrelevant. Therefore if we also take into account if any difference is simply “wrong”, “limited” or “no relevance”, or even a “better choice” than H’s (

Table 5), it comes out that the “wrong” cases (35) are far fewer than all other ones (91), namely 27,7% out of all discrepancies, while the “better choices” (51) are as much as 40,47% of them.

A further positive result stemming from the evaluation is that the AI does not seem so biased in its analysis. One problem often pointed out about MLLMs is their being subject to biases induced by their knowledge base. Here instead Gemini’s analyses are quite overlapping with the human’s: even in cases of redundancy, where it highlights something that the human did not, this does not contradict what may be implied by the rest of human’s analsys. In general, Gemini does not seem biased towards one or another position, but fairly impartial between the two interactants: for example, it is not particularly pro-American, although being issued in the States, and keeps its analysis on a descriptive and not evaluative level.

Finally, thanks to this evaluation we were able to tune a “final prompt” that can be used from now on to have a MLLM analyse a political debate in terms of Multimodal LEP Analysis (see Supplementary materials, 4. Final prompt).

6. Conclusion

This study aimed to assess whether a multimodal large language model (MLLM) can be instructed, through prompt engineering, to analyze political discourse and political debates according to a multimodal LEP framework, identifying elements of Logos, Ethos, and Pathos across words, voice, gesture, facial expression, gaze, and posture. Focusing on the Trump-Zelensky meeting held at the White House on February 28, 2025, we first conducted a human LEP-based analysis and then instructed Gemini 2.5 Pro using two different prompts. Through iterative testing and refinement, an optimized prompt was developed, and the model’s performance was evaluated using a benchmarking framework comparing AI and human analyses.

The results indicate that an MLLM can be successfully instructed to perform a theoretically grounded multimodal LEP analysis of political discourse and, in some cases, can match or even outperform human analysis. This finding is encouraging, given that comprehensive multimodal analyses of political speeches and debates are notoriously time-consuming and cognitively demanding, often limiting human research to short excerpts. An AI-assisted approach has the potential to extend such analyses to longer speeches or larger corpora, making them more feasible for research, journalism, and political communication analysis.

It is important, however, to clarify the scope and generalizability of these results. While the empirical findings cannot yet be generalized in a strong sense—given that the study examined a single case using a single model—the methodological approach is highly transferable. The iterative process of prompt design, testing, benchmarking against human analysis, and systematic evaluation can be replicated across different cases, contexts, and analytical frameworks.

From a technical standpoint, the experiments were conducted using Google AI Studio, primarily for reasons of accessibility and ease of use. This choice was pragmatic rather than methodological: the same procedures could be implemented through custom interfaces, APIs, or dedicated virtual environments, potentially allowing for more complex multimodal pipelines. At the same time, the use of an accessible interface highlights an important advantage, namely that advanced forms of discourse analysis through prompt engineering can be made available even to researchers without specialized expertise in machine learning or software development.

A further limitation concerns the exclusive use of a proprietary, state-of-the-art model. While this choice provides insight into the upper bounds of current MLLM performance, it also raises issues of reproducibility, dependency on commercial platforms, and data privacy. Given the rapid evolution of open-source multimodal models, it is plausible that comparable performance could soon be achieved with models running locally and adapted through fine-tuning or instruction tuning. Such developments would be particularly relevant for sensitive domains such as political discourse analysis, where data protection and privacy are crucial.

Of course, the work on LLMs as a tool for Discourse analysis generally raises relevant ethical issues. Although Gemini in our case did not show so subject to biases, this is always a risk, which may have severe outcomes given the apparent “authoritativeness” that a MLLM can inspire. Other ethical concerns, although not holding for public contents like in our case, may be salient for verbal or visual contents exposing vulnerable subjects. To avoid such risks, it is important for AI to be always supervised and monitored by human interpretation.

In fact, this work points toward a more interactive perspective on human-AI collaboration in discourse analysis. Rather than treating the MLLM solely as an analytical tool, future developments may explore richer dialogic interactions in which the model acts as an epistemic partner. Through iterative exchanges, the AI may highlight aspects of the discourse that the human analyst had not initially considered, thereby enriching interpretation, suggesting new analytical angles, and supporting a reflexive analytical process. In this sense, the contribution of MLLMs lies not only in efficiency and scalability, but also in their potential to expand the interpretive space of multimodal discourse analysis.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P., D.D., T.S; formal analysis, I.P., S.C., S.V., T.S., writing, I.P., T.S., D.D., M.D.E.; Supervision, I.P. D.D.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it analyzes publicly available audiovisual media released for public consumption. According to established research ethics frameworks on the use of publicly accessible data, such analyses do not require informed consent and do not pose risks to the individuals involved. No personal or sensitive data were collected, stored, or processed.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived because the human subjects who acted as the three independent annotators of the collected multimodal data analyzed in this work are three Authors of the paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. AI Agents vs. Agentic AI: A Conceptual Taxonomy, Applications and Challenges. Information Fusion 2026, 126, 103599. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2017; Vol. 30.

- Gemini Team Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models; 2023;

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models 2020.

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; de Las Casas, D.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models 2022.

- Gemini Team, Google Gemini 1.5: Unlocking Multimodal Understanding across Millions of Tokens of Context 2024.

- Gemini Team, Google Gemini 2.5: Pushing the Frontier with Advanced Reasoning, Multimodality, Long Context 2025.

- Anthropic Introducing the Model Context Protocol Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/model-context-protocol (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Qu, C.; Dai, S.; Wei, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Xu, J.; Wen, J.-R. Tool Learning with Large Language Models: A Survey; arXiv; 2024;

- Yehudai, A.; Eden, L.; Li, A.; Uziel, G.; Zhao, Y.; Bar-Haim, R.; Cohan, A.; Shmueli-Scheuer, M. Survey on Evaluation of LLM-Based Agents; arXiv; 2025;

- Garg, R.; Han, J.; Cheng, Y.; Fang, Z.; Swiecki, Z. Automated Discourse Analysis via Generative Artificial Intelligence. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th learning analytics and knowledge conference; Kyoto, Japan, March 2024; pp. 814–820.

- Herring, S.C. Débats Sur Le Débat - Susan Herring - Is Generative AI the Future of Qualitative Discourse Analysis? Séminair de l’Université de Lille, May 23rd, 2025. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s2XZQhaaCMg (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Tausczik, Y.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Psychological Meaning of Words: LIWC and Computerized Text Analysis Methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 2010, 29, 24–54. [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.; Koutsiana, E.; Massey, J.; Thuermer, G.; Simperl, E. Prompting Datasets: Data Discovery with Conversational Agents 2023.

- Tabone, W.; De Winter, J. Using ChatGPT for Human–Computer Interaction Research: A Primer. Royal Society Open Science 2023, 10, 231053. [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, S. Performing an Inductive Thematic Analysis of Semi-Structured Interviews with a Large Language Model: An Exploration and Provocation on the Limits of the Approach. Social Science Computer Review 2024, 42, 997–1019.

- Hamilton, L.; Elliott, D.; Quick, A.; Smith, S.; Choplin, V. Exploring the Use of AI in Qualitative Analysis: A Comparative Study of Guaranteed Income Data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231201504. [CrossRef]

- Chew, R.; Bollenbacher, J.; Wenger, M.; Speer, J.; Kim, A. LLM-Assisted Content Analysis: Using Large Language Models to Support Deductive Coding; arXiv, 2023;

- Nguyen-Trung, K. ChatGPT in Thematic Analysis: Can AI Become a Research Assistant in Qualitative Research? Quality & Quantity 2025, 59, 4945–4978. [CrossRef]

- Törnberg, P. How to Use Large Language Models for Text Analysis 2023. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.13106.

- Chiu, K.L.; Collins, A.; Alexander, R. Detecting Hate Speech with GPT-3; arXiv, 2021;

- Huang, F.; Kwak, H.; An, J. Is ChatGPT Better than Human Annotators? Potential and Limitations of ChatGPT in Explaining Implicit Hate Speech; arXiv, 2023;

- Fan, Y.; Jiang, F.; Li, P.; Li, H. Uncovering the Potential of ChatGPT for Discourse Analysis in Dialogue: An Empirical Study; arXiv, 2023;

- Labruna, T.; Brenna, S.; Zaninello, A.; Magnini, B. Unraveling ChatGPT: A Critical Analysis of AI-Generated Goal-Oriented Dialogues and Annotations.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 151–171.

- Siiman, L.A.; Rannastu-Avalos, M.; Pöysä-Tarhonen, J.; Häkkinen, P.; Pedaste, M.; Huang, Y.-M.; Rocha, T. Opportunities and Challenges for AI-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis: An Example from Collaborative Problem-Solving Discourse Data.; Springer, 2023; pp. 87–96.

- De Paoli, S. Further Explorations on the Use of Large Language Models. Open-Ended Prompts, Better Terminologies and Thematic Maps. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gillings, M.; Kohn, T.; Mautner, G. The Rise of Large Language Models: Challenges for Critical Discourse Studies. Critical Discourse Studies 2025, 22, 625–641.

- Herring, S.C. Computer-Mediated Discourse Analysis: An Approach to Researching Online Behavior. In Designing for virtual communities in the service of learning; Barab, S.A., Kling, R., Gray, J.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2004; pp. 338–376.

- Herring, S.C. Politeness in Computer Culture: Why Women Thank and Men Flame. In Cultural Performances: Proceedings of the Third Berkeley Women and Language Conference; Bucholtz, M., Liang, A.C., Sutton, L., Eds.; Berkeley Women and Language Group: Berkeley, CA, 1994; pp. 278–294.

- Herring, S.C. Methodological Synergies in the Study of Digital Discourse: A Critical Reflection. Discourse, Context & Media 2025, 66, 100931. [CrossRef]

- Parisi, D.; Castelfranchi, C. Discourse as a Hierarchy of Goals; Working Papers; Centro Internazionale di Semiotica e Linguistica (Università di Urbino): Urbino, 1976;

- Conte, R.; Castelfranchi, C. Cognitive and Social Action; Garland Science: London, 1995;

- Poggi, I. Mind, Hands, Face and Body. A Goal and Belief View of Multimodal Communication; Weidler: Berlin, 2007;

- Poggi, I. The Language of Gaze. Eyes That Talk; Routledge: London ; New York, 2024;

- Poggi, I.; D’Errico, F. Social Influence, Power, and Multimodal Communication; Routledge: London, 2022;

- Poggi, I. The Goals of Persuasion. Pragmatics & Cognition 2005, 13, 297–336. [CrossRef]

- Castelfranchi, C.; Falcone, R. Trust Theory: A Socio-Cognitive and Computational Model; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 2010;

- Macagno, F.; Walton, D. Emotive Language in Argumentation; Cambridge University Press: New York, 2014;

- Cepernich, C.; Novelli, E. Sfumature del razionale. La comunicazione politica emozionale nell’ecosistema ibrido dei media. Comunicazione politica 2018, 19, 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Wirz, D.S. Persuasion Through Emotion? An Experimental Test of the Emotion-Eliciting Nature of Populist Communication. International Journal of Communication 2018, 12, 1114–1138.

- Poggi, I.; Careri, S.; Violini, S.E. Stili Di Discorso e Orientamento Politico. Populismo, Sovranismo e Strutture Persuasive. In Il ritorno della nazione: linguaggi e culture politiche in Europa e nelle Americhe; Novelli, E., Ed.; Carocci editore: Roma, 2023; pp. 57–77.

- https://independent.academia.edu/PoggiIsabella.

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2020; Vol. 33, pp. 1877–1901.

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Ichter, B.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.H.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in neural information processing systems; 2022; Vol. 35, pp. 24824–24837.

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, A.C.-C. Meta Prompting for AI Systems 2023.

- Pryzant, R.; Iter, D.; Li, J.; Lee, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zeng, M. Automatic Prompt Optimization with “Gradient Descent” and Beam Search. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP); Singapore, 2023.

- Hendrycks, D.; Burns, C.; Basart, S.; Zou, A.; Mazeika, M.; Song, D.; Steinhardt, J. Measuring Massive Multitask Language Understanding.; 2021.

- Yue, X.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, T.; Liu, R.; Zhang, G.; Stevens, S.; Jiang, D.; Ren, W.; Sun, Y.; et al. MMMU: A Massive Multi-Discipline Multimodal Understanding and Reasoning Benchmark for Expert AGI.; 2024; pp. 9556–9567.

- Lu, P.; Bansal, H.; Xia, T.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Hajishirzi, H.; Cheng, H.; Chang, K.-W.; Galley, M.; Gao, J. MathVista: Evaluating Mathematical Reasoning of Foundation Models in Visual Contexts.; 2024.

- Sabour, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.; Sunaryo, A.; Lee, T.; Mihalcea, R.; Huang, M. EmoBench: Evaluating the Emotional Intelligence of Large Language Models.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024; pp. 5986–6004.

- Gennaro, G.; Ash, E. Emotion and Reason in Political Language. The Economic Journal 2022, 132, 1037–1059. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Multimodal LEP analysis. An annotation scheme of multimodal political communication.

Table 1.

Multimodal LEP analysis. An annotation scheme of multimodal political communication.

1

Time & Sender |

2

Modality |

3

Signal |

4

Literal meaning |

5

Indirect meaning |

CLASSIFICATION |

| 6 Ritual |

LOGOS |

ETHOS |

PATHOS |

7

Logos |

8

Our Merits |

9

Their Demerits |

10

Expressed Emotion |

11

Induced Emotion |

13.38

Trump |

Verb |

there has never been a first month like uh like we’ve had |

I did many things in my first month as a President |

I am better than all other Presidents |

|

|

C

|

|

Pride |

|

| |

Gaze |

Looks forward |

I address you all

|

I am confident |

|

|

|

|

Self-confidence |

|

13.52

Trump |

Verb |

Think of the parents whether they are Russian or Ukraine |

You should feel compassion for both Russian and Ukrainian parents |

I am neutral, I do not take sides for Ukraine

→this is how to make a deal

+

I am skilled in making deals |

|

X |

B

C |

|

|

Compassion for Russian victims’ parents |

| |

Head |

Shakes head |

No, no |

We must stop this tremendous death |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

| |

Gaze |

Squints eyes |

I feel sorrow for them |

You should feel compassion |

|

|

|

|

sorrow |

Compassion |

13.52

Zelensky |

Verb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Head |

Turns face rightward (the opposite direction of Trump) |

I do not want to hear him while saying so |

I do not agree with Trump |

|

|

|

PS

-B |

|

|

| |

Mouth |

Left corner lowered |

I feel disgust for Russians |

Russians are evil

→

They do not deserve compassion

→

I do not agree with Trump |

|

|

|

PS

TB

-B |

disgust |

No compassion |

Table 2.

Comparison, Evaluation and Rating of the MLLM’s performance.

Table 2.

Comparison, Evaluation and Rating of the MLLM’s performance.

| 1 Signal |

2 Human |

3 AI |

4 Comparison |

5 Evaluation |

6 Rating |

| Section S (Signal) |

Signal

(Voice) |

Slightly raised pitch, faster pace |

High pitch, stressed tone on “hatred”. |

D2 |

BC |

1 |

Signal

(Gaze) |

Fixed Gaze |

Maintains direct eye contact with Trump |

D1 |

W |

-2 |

Signal

(Gesture) |

Right hand, index finger slightly extended, moves slightly rightward to Z. |

Right hand gestures towards Zelensky (“him”), then left hand gestures away (“the other side”). |

D2 |

BC |

1 |

| Section M (Meaning) |

| Literal Meaning (Verbal) |

Zelensky hates Putin |

Zelensky has a lot of hatred for Putin |

D2 |

NR |

0 |

| Literal Meaning (Body) |

|

I am engaged but tense. |

R |

BC |

2 |

Indirect Meaning

(Verbal) |

|

I am benevolent enough to understand, but competent enough to see the bigger picture |

R |

BC |

2 |

| Indirect Meaning (Gaze) |

This makes a deal impossible |

I am revealing something important about him to you |

D1 |

W |

-2 |

| Section C (Classification) |

| Ethos - Our Merits (Gestures) |

|

C |

R |

BC |

2 |

| Ethos - Their Demerits (Gaze) |

I. -B |

|

A |

W |

-2 |

| Pathos- Expressed Emotion (Verbal) |

|

Frustration |

R |

BC |

2 |

| Pathos- Expressed Emotion (Gaze) |

Alarm, Worry |

Confidence |

D1 |

W |

-2 |

| TOTAL SCORE |

2 |

Table 4.

Rating of Gemini 2.5. Pro’s analysis.

Table 4.

Rating of Gemini 2.5. Pro’s analysis.

| Comparison |

n. |

| Identical |

28 |

| Absence |

37 |

| Partial Absence |

5 |

| Redundancy |

42 |

| Partial Redundancy |

10 |

| High Discrepancy |

11 |

| Minor Discrepancy |

22 |

Table 5.

Evaluation.

| Evaluation |

n. |

| Wrong |

35 |

| Limited Relevance |

25 |

| Not Relevant |

15 |

| Better Choice |

51 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).