1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has transformed lifestyles by offering novel solutions to real-world problems and challenges and has introduced revolutionary changes across application domains. Although AI systems enhance efficiency and generate value, the ethical and societal issues they raise have become global concerns. For instance, the rapid development of various technologies (e.g., autonomous driving, drones, smart health care, and generative language models) has led to ethical risks, including algorithmic bias, data privacy infringements, opacity in decision-making, and ambiguous accountability. In response to these challenges, multiple international AI ethics guidelines and governance frameworks have been introduced, including the European Union’s AI Act and various national white papers on technology ethics, which aim to address the ethical and social risks posed by technological advancements through policy and institutional design [

1,

2]. As AI applications penetrate deeper into decision-making processes and social governance, building AI systems with ethical sensitivity and social legitimacy has become inevitable in technological development and is a cornerstone for maintaining social trust and promoting sustainable development.

Against this backdrop, academic and public interest in AI ethics has significantly increased worldwide. Systematic searches of scholarly databases reveal that existing research encompasses diverse topics, including data governance, model fairness, transparency design, and accountability ethics, forming an interdisciplinary and multifaceted body of knowledge [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Nevertheless, most prior studies have focused on static articles or in-depth analyses of individual issues, without a systematic examination of whether semantic shifts, thematic evolution, or value-focused transformations occur in AI ethics discourse over time. Given the continuous and rapid evolution of AI technology and its application contexts, discourse on ethical issues may significantly change over time and potentially shift in thematic focus due to event-driven factors, policy interventions, and public opinion.

Motivated by these considerations, this study employs topic detection techniques in text mining to conduct an in-depth analysis of multiple unstructured articles. This work explores whether the themes addressed in AI ethics reports demonstrate stable and consistent focal points or reveal dynamic shifts and contextual changes alongside technological and temporal developments. This research aims to identify the underlying semantic shifts and trends in AI ethics topics by thoroughly examining and comparatively analyzing recent AI ethics articles published by academic institutions, media outlets, and nonprofit organizations [

7,

8,

9].

This study integrates the KeyGraph text mining algorithm grounded in the theory of chance discovery with the generative AI capabilities of the large language model (LLM)-based ChatGPT tool to address the challenges of semantic analysis in unstructured textual datasets. This integration establishes an innovative research workflow combining structured mining with semantic interpretation. KeyGraph, a graph-based method, constructs keyword networks and knowledge graphs by calculating the frequency and co-occurrence strength of keywords. Notably, KeyGraph identifies “chance” keywords that, despite their low frequency, possess significant bridging value in the network structure, revealing latent topics or emerging concepts in the dataset. This approach surpasses traditional frequency-based methods by uncovering hidden associations, offering the substantial potential for analyzing thematic evolutions and shifts in ethical focus [

10].

Unlike standard topic modeling techniques, such as latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), correlated topic models, and Pachinko allocation models, which are unsupervised learning methods requiring predefined topic numbers and statistical distributions to infer latent topics [

11,

12,

13], topic detection emphasizes identifying semantic associations and dynamic thematic changes. Topic detection is suitable for analyzing rapidly evolving, cross-temporal, or dynamic problem-oriented datasets. The KeyGraph algorithm is a well-recognized topic detection tool that captures nonlinear co-occurrence relationships between keywords, making it appropriate for exploring complex ethical issues characterized by competing values and shifting contexts, as in this study [

14,

15,

16].

Furthermore, this study employs ChatGPT as an auxiliary tool for semantic interpretation and summary generation to overcome the subjective limitations in conventional topic analysis methods that rely on expert interpretation for deep semantic understanding and domain knowledge. By applying ChatGPT’s advanced language comprehension and summarization capabilities, researchers can achieve more accurate and focused thematic interpretations of each keyword cluster generated by KeyGraph, enhancing the precision of topic detection and the overall efficiency and interpretability of the analytical process [

17].

Researchers have employed a human–AI interactive mechanism based on the double helix model to adjust node parameters, reclassify keyword clusters, and evaluate the semantic consistency and logical coherence of generated summaries dynamically. Through iterative HCI, this process constructs a logically coherent thematic structure for AI ethics [

18].

This study analyzes AI ethics-related articles published between 2022 and 2024 by international academic institutions, news media, and nonprofit organizations. Rigorous selection criteria were applied during data collection. Sources were limited to reputable, authoritative organizations, and articles focusing exclusively on single disciplines or industry-specific applications were excluded. Comprehensive reports reflecting global trends were prioritized to ensure the dataset represented diverse perspectives and contentious issues in AI ethics worldwide, establishing a neutral and macro-level textual database. Eight representative documents were selected for each year as the basis for the KeyGraph algorithm-based topic detection and chance exploration.

This study conducts comparative analyses of annual thematic clusters using a multistage processing approach, including text preprocessing, keyword network construction, topic detection, and semantic interpretation. Core themes, logical shifts, and changing focal points were identified, and the chance keywords were explored to detect potentially nascent but promising ethical issues.

In summary, this research combines the structural keyword mining capabilities of KeyGraph with the semantic comprehension of ChatGPT to develop a dynamic, extensible, and semantically rich method for topic detection. The approach aims to provide empirical evidence and strategic insight for trend monitoring, governance planning, and knowledge construction in AI ethics while enabling nonspecialist audiences to understand the evolving dynamics of AI ethics themes quickly.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI Ethics Literature Review

Recently, ethical issues surrounding AI have become a primary focus in academia and the public sphere, reflecting their increasing importance in the global development of technology and social governance. Systematic searches of scholarly databases have revealed that the existing literature covers diverse themes, with some studies focusing on specific topics (e.g., data transparency and privacy protection), and others attempting to integrate multiple dimensions of ethical concerns for interdisciplinary comprehensive analyses [

7,

19]. However, structural examinations of the interrelationships between various ethical issues remain limited, especially in the context of rapidly evolving and emerging technology, including generative AI and autonomous driving. Thus, capturing the contextual shifts and logical frameworks of ethical controversies across interdisciplinary articles remains a significant research gap [

20]. Against this background, AI ethics-related reports published by news media, academic institutions, and nonprofit organizations (characterized by their timeliness, readability, and public engagement) have become critical data sources for observing thematic evolution and tension regarding value. These reports complement the limited academic articles in clarifying practical contexts and ethical value conflicts.

The ethical issues surrounding AI are highly diverse and complex, encompassing multiple dimensions, including technology, law, society, and philosophy [

19,

20]. In response to these characteristics, this study employs the KeyGraph algorithm combined with text mining techniques to construct keyword co-occurrence networks based on the frequency and co-occurrence relationships of keywords. This work aims to reveal the ethical topics of concern systematically and visually across articles from various sources while assessing the keyword diffusion structure and intrinsic logical associations [

21].

A core subtopic in AI ethics is AI governance, focusing on ensuring the trustworthiness and social acceptance of AI systems in public decision-making and societal applications. The literature indicates that trustworthy AI should encompass multiple elements, including accuracy, robustness, transparency, accountability, fairness, explainability, interpretability, legality, appeal mechanisms, and human oversight. However, in practice, these value indicators often cannot be satisfied simultaneously, resulting in significant priority conflicts and a lack of comparability when using a single value. For example, enhancing the accuracy of AI systems often relies on highly complex models, sacrificing transparency and explainability. Similarly, conflicts may arise in fairness metrics. The statistical impossibility triangle indicates that, under differing group base rates, simultaneously balancing false-positive rates and false-negative rates is not possible [

20,

22].

Furthermore, the integration of AI technology with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has become a focal point in AI ethics research. Although AI plays is critical for promoting technological applications, social innovation, and resource efficiency, it must also address the challenges posed by responsible governance and sustainable deployment.

Relevant studies have identified four primary challenges in integrating AI ethics with sustainability initiatives. First, in the ethical and social dimension, issues of transparency, fairness, bias, and accountability have gained increasing attention as automated decision-making and algorithmic deployment become more widespread. Second, the sustainability of AI imposes environmental pressure, particularly due to the high energy consumption and resource use required by large-scale model computations. Third, existing governance and regulatory frameworks often fail to respond effectively to the challenges and issues introduced by technological evolution, typically remaining at a reactive level. Fourth, technical bottlenecks persist, including insufficient model explainability, data governance challenges, and the design of multidimensional performance metrics, such as accountability, fairness, and accuracy [

9,

22].

Moreover, the large volume of sensitive data generated by AI applications exacerbates risks related to data privacy and information security. In AI-driven knowledge management systems, ethical risks have emerged regarding various issues (e.g., privacy, bias, and transparency). A systematic review of 102 AI ethics research articles reveals that privacy and algorithmic bias account for 27.9% and 25.6% of the addressed topics, respectively, making them the most frequently addressed concerns. Additionally, transparency, accountability, and fairness remain core concerns [

23].

This finding closely aligns with the ethical value frameworks identified in other studies, illustrating that the current AI ethics risks have gradually shifted from abstract principles to practical operational challenges, requiring interdisciplinary integration and technological governance for effective resolution [

20,

23,

24]. To address these challenges, some studies have recommended adopting decentralized data governance models (e.g., federated learning and distributed data architectures) to balance data utility and privacy protection. Moreover, AI system performance evaluation should move beyond traditional single accuracy metrics to multidimensional frameworks encompassing environmental effects, social implications, and ethical compliance to reflect sustainability performance comprehensively. Furthermore, promoting inclusive development processes and human-centered design principles by incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives can help avoid systemic biases and strengthen the legitimacy of ethical governance.

Although existing AI ethics research and policy documents have proposed core principles, such as transparency, accountability, fairness, and privacy, implementing these principles at the organizational level remains a considerable challenge. A notable gap exists between normative formulation and organizational practice in AI ethics, and relying solely on external guidelines and compliance requirements is insufficient to address the ethical controversies and issues encountered in practice. This gap underscores the importance of organizational AI ethics. Organizations should proactively establish internal governance mechanisms that integrate AI ethics principles throughout the technology life cycle, deliberation processes, and risk assessment frameworks to enhance ethical sensitivity and adaptive capacity [

9,

19,

20,

23].

In summary, AI ethics has progressed from the initial stages of principle declaration and conceptual proposals to practice-oriented institutional construction and governance innovation. Future research should further develop integrated analytical frameworks and multilevel governance models encompassing design principles, regulatory mechanisms, ethical conflict identification, and social participation, to ensure that AI development promotes technological innovation and upholds ethical values, social order, and the core objectives of sustainable development [

9,

19,

20].

2.2. Chance Discovery Theory

The chance discovery theory is an interdisciplinary data mining framework designed to identify rare yet highly valuable “chances” in data via HCI and structural data analysis, which may critically influence future decision-making or system development. In this theory,

chance is broadly defined as important information that can guide decision-makers or automated decision systems to make significant responses. These chances may indicate emerging opportunities not yet explicitly recognized or indicate potential undiscovered risks and crises [

10,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Unlike the discovery of random events, chance discovery stresses conscious awareness rather than random detection [

26]. Chance discovery analyzes the frequency of information or keyword occurrences and places greater importance on their associations with other critical information. Keywords and their connections in articles can be visualized via structured keyword analyses and visualization tools (e.g., the Polaris visualization tool implementing the KeyGraph algorithm) [

25], identifying bridging words that are highly associated with multiple keyword clusters. These bridging words may indicate potential chances. This theory has significant application potential in innovation early warning, risk governance, and strategic planning, while providing theoretical support and practical foundations for structured semantic analyses and topic detection methods [

10,

29,

30].

Compared to traditional data analysis methods that assume a stable data structure and known variables, chance discovery focuses on information nodes with low frequency but potentially profound semantic or systemic implications. This process is a gradual unfolding of understanding rather than an immediately identifiable event. The theory of chance discovery underscores that the most critical insight is often hidden in unstructured information, and this theory stresses the need for decision-makers to engage in the dynamic evolution of information. This theory combines the human sensitivity to context and situational awareness with the computational capabilities in data processing and visualization to effectively detect chance information and strategic responses [

10,

29,

30].

Professor Ohsawa proposed the following three criteria for judging chance [

10,

29,

30]:

Establishing and uncovering innovative models and variables: Rather than relying on existing data models and variables, this approach incorporates contextual factors into the analysis to identify noteworthy variables emerging in specific situations, preventing the results from diverging from practical needs and enhancing the accuracy of chance detection.

Identifying tail events: Tail events are rare events with a low frequency but profound influence on the system or domain. Undiscovered chances or phenomena can be identified by observing and analyzing such tail events.

Relying on human–AI interaction for interpretation and judgment: Whether a tail event represents a genuine chance can be discerned by applying extensive human background knowledge and contextual sensitivity. This approach is necessary because the rarity and ambiguity of tail events make it challenging for fully automated data mining methods to assess their true value and significance accurately.

Therefore, the chance discovery theory emphasizes HCI, asserting that the effective awareness, understanding, and realization of chances can be facilitated only by combining computational data processing and visualization capabilities with the rich background knowledge of domain experts, enhancing the accuracy and practical utility of chance identification.

In this exploratory process, information is generated and interpreted in a nonlinear and intertwined manner, giving rise to the double helical model as a cognitive framework for exploring latent meaning via HCI. Computers continuously mine data from the environment and human expression, providing visualized feedback to assist human understanding and judgment. Humans iteratively adjust their comprehension and focus, inspiring new exploration directions. By further integrating the subsumption architecture cognitive model, this approach presents a nonlinear, concurrently operating interactive feedback loop comprising computer mining, feedback results, human understanding, and decision-making processes, requiring continuous and iterative exploration that more closely aligns with human cognitive patterns [

10,

26,

31].

The theory of chance discovery has been widely applied across multiple domains, including health care, business innovation, marketing, disaster prediction, risk management, and decision-making, underscoring its generative rather than merely analytical power. This theory facilitates a deeper understanding of existing data and helps identify rare events and latent information that are difficult to detect via conventional analyses, yet have a significant influence on future decisions. This theory provides a data analysis method and integrated knowledge creation framework that combines human–computer interaction (HCI), semantic construction, and abductive reasoning, fostering the formation of new hypotheses and value creation [

10,

25,

26].

2.3. Double Helix Model: Human–Machine Collaborative Framework for Chance Discovery

This study adopts the theory of chance discovery as its theoretical foundation and applies its core framework (the double helix model) to conduct semantic network analyses and topic detection via an HCI process. The model comprises two interwoven components: the computer- and human-driven processes, forming a spiral cognitive feedback mechanism akin to the structure of DNA. This approach represents the dynamic interplay between data-driven analyses and knowledge interpretation in HCI. The process is designed to assist researchers in identifying low-frequency yet semantically significant nodes (

chances) in the keyword network [

21,

25,

26,

31,

32,

33].

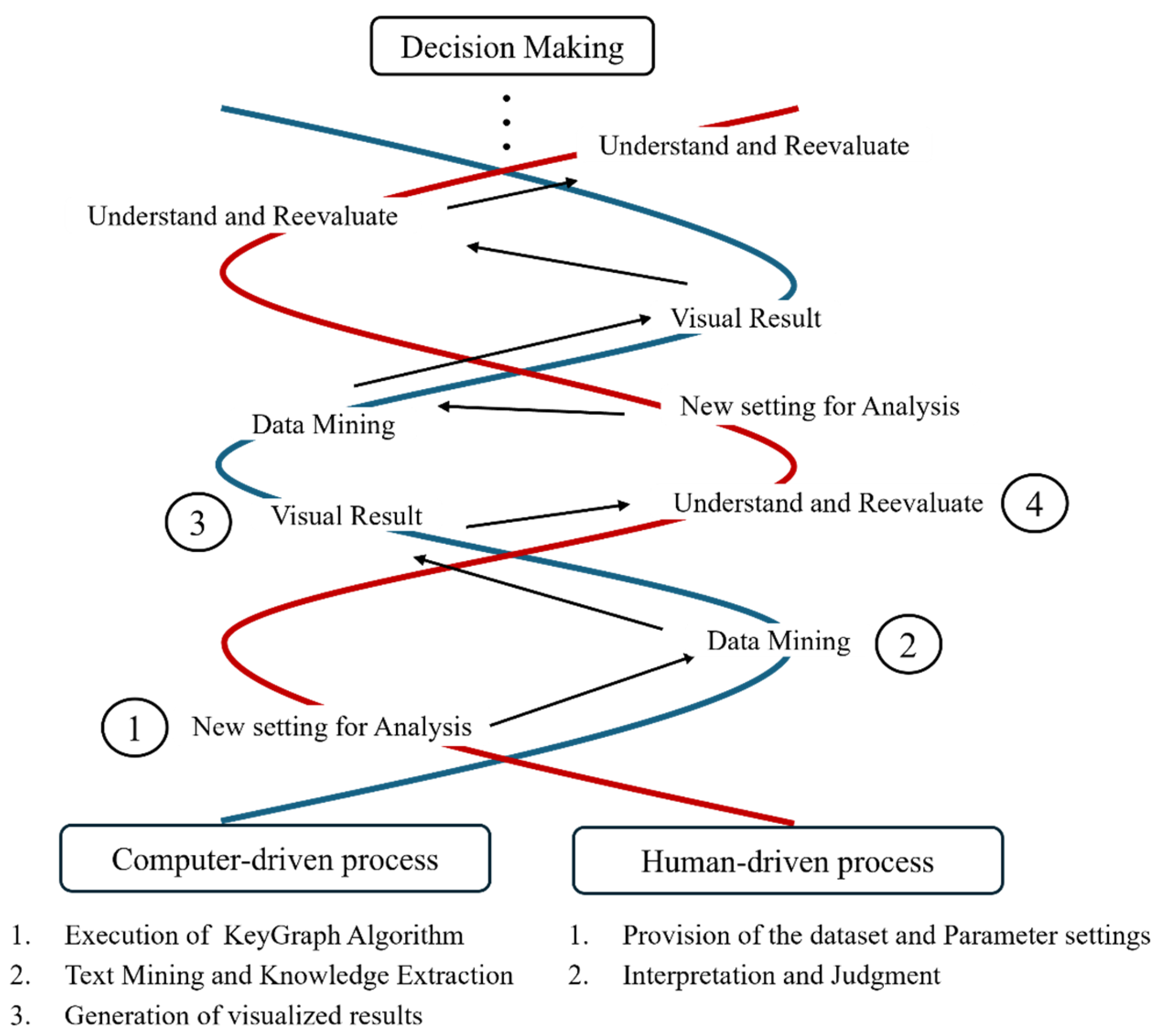

Based on this integrative explanation, this study applies a dual-dimensional interactive structure, advancing through a spiral formation that illustrates the iterative nature of human–AI collaboration. As depicted in

Figure 1, researchers can follow the spiral pathway to track the feedback and adjustment mechanisms dynamically across each stage. According to this double helix model, the HCI loop is divided into four primary stages, each embodying iterative cycles between the human- and computer-driven processes. This ongoing dynamic feedback mechanism facilitates the progressive refinement and optimization of the semantic structure and topic detection [

21,

25,

26,

31,

32,

33].

The specific phases of the human–AI interaction cycle are as follows [

10,

21,

33,

34,

35]:

Human-driven process: New setting for analysis (inputting article data and initializing parameters). The researcher conducts this phase, which marks the starting point of the overall HCI cycle. Based on the research objectives, the researcher provides the original article dataset and employs the Polaris visualization tool to set the initial parameters for the KeyGraph algorithm, such as the number of default bridging nodes (represented as red nodes) and high-frequency black keyword nodes, establishing the foundation for an automated computer analysis (see Phase 1 in

Figure 1).

Computer-driven process: Data mining (data mining and keyword network construction). After the initial parameter setting, the process transitions to a computer-driven process, entering the phases of data mining and keyword network construction. At this stage, the computer autonomously executes the KeyGraph algorithm to conduct in-depth mining of the article dataset. The system constructs a co-occurrence network graph by calculating the co-occurrence frequency and structural relationships between keywords. This phase applies the KeyGraph algorithm to extract latent knowledge structures and keywords automatically from large-scale articles, providing a foundation for semantic interpretation (see Phase 2 in

Figure 1).

Computer-driven process: Visual results (network graph visualization). After data mining is completed, the computer transforms the keyword network generated by the KeyGraph algorithm into a visualized graph illustrating the connections (i.e., the co-occurrence relationships) between keywords, including the red nodes. This visual representation serves as a bridge between the computer and human user, converting abstract keyword associations into intuitive, interpretable images that facilitate information integration and semantic judgment. At this stage, the computer completes its intermediate task and awaits human intervention for further examination (see Phase 3 in

Figure 1).

Human-driven process: Understanding and re-evaluation (interpretation and review). This phase represents the core of human knowledge interpretation in the double helix model, highlighting the iterative nature of HCI. In this process, researchers do not directly engage in topic detection; instead, based on their domain expertise and semantic comprehension abilities, they systematically evaluate the topic detection and semantic interpretation results generated by ChatGPT from the keyword network visualizations constructed using the KeyGraph algorithm. Researchers examine the thematic and keyword relationships in the visualized graphs and assess whether ChatGPT’s initial interpretations are logically coherent, substantively meaningful, and effectively reveal the latent semantics in the articles. For instance, if ChatGPT produces an illogical output (e.g., “I beer”), researchers employ the Polaris visualization tool to adjust the node parameters of the KeyGraph algorithm (e.g., the number of high-frequency black keywords or red chance nodes) until the output becomes coherent and logically consistent (e.g., “I love to drink beer”). This ongoing process of understanding the output and continuously tuning parameters, which triggers new data mining and visual output, is the critical objective of the iterative cycles in the double helix model. Thus, this approach forms a continuously optimized spiral iteration process (see Phase 4 in

Figure 1).

The mentioned HCI process is not a one-time analysis but integrates efficient computer processing capabilities with human critical thinking and domain expertise. The iterative refinement of keyword structures and thematic interpretations forms a continuous and spiraling process via repeated interactive cycles. This iterative cycle is the core driving force of the double helix model, ensuring the analysis process maintains high flexibility and adaptability [

21]. Guided by their deep understanding of the data, researchers continually refine the model, progressively transforming implicit keyword structures into explicit knowledge, providing a solid foundation for informed decision making. Researchers can interpret and understand the emerging or evolving themes and issues via this process, enabling more informed and progressive decisions. This example illustrates the advantages of HCI in addressing complex problem-solving [

10,

32,

34,

35].

2.4. KeyGraph Algorithm Overview

The KeyGraph algorithm is a core tool for implementing chance discovery. This graph-based text mining technique aims to uncover critical contexts and latent events with significant influence that are hidden in texts via a keyword network model, which is compared to traditional keyword frequency-dependent algorithms (e.g., term frequency-inverse document frequency or LDA). The KeyGraph algorithm is widely applied in topic detection research. The operational mechanism extracts high-frequency keywords from the text as nodes and analyzes the co-occurrence relationships between these keywords to construct a keyword network graph [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Furthermore, the uniqueness of this algorithm lies in its ability to identify “keywords that have structural bridging value but occur with low frequency,” revealing latent nonexplicit topics and interdisciplinary conceptual connections in the text. This approach enables the derivation of core issues and underlying value perspectives in articles. This method does not require manual annotation or prior knowledge and can automatically extract representative keywords or topics from the collected technical texts or academic literature. This method constructs a keyword network graph to present the associative structure of keywords, enhancing the transparency and interpretability of topic detection [

36,

37,

41,

42].

2.4.1. KeyGraph Keyword Network Structure and Visualization

The KeyGraph algorithm is suitable for applications, including knowledge structure exploration, thematic context evolution analysis, and emerging topic detection, owing to its advantages in knowledge structure construction and analysis. Ohsawa first proposed this algorithm in 1998, initially as an automatic indexing technique based on keyword co-occurrence graphs in texts, and it was later developed into a core analytical tool for chance discovery applications. In Ohsawa’s original conceptualization, the KeyGraph algorithm is explained using an architectural structure analogy. The literature is viewed as a building, where the foundation represents the fundamental concepts of the literature, constructed by analyzing co-occurrence relationships between high-frequency keywords. The pillars symbolize the associations between the keywords and foundational concepts, forming a structured network connecting concepts in the literature. The roof represents the core viewpoints in the literature, typically constituted by low-frequency bridging keywords strongly connected to multiple conceptual clusters, reflecting the primary perspectives or innovative points in the literature [

10,

38,

41].

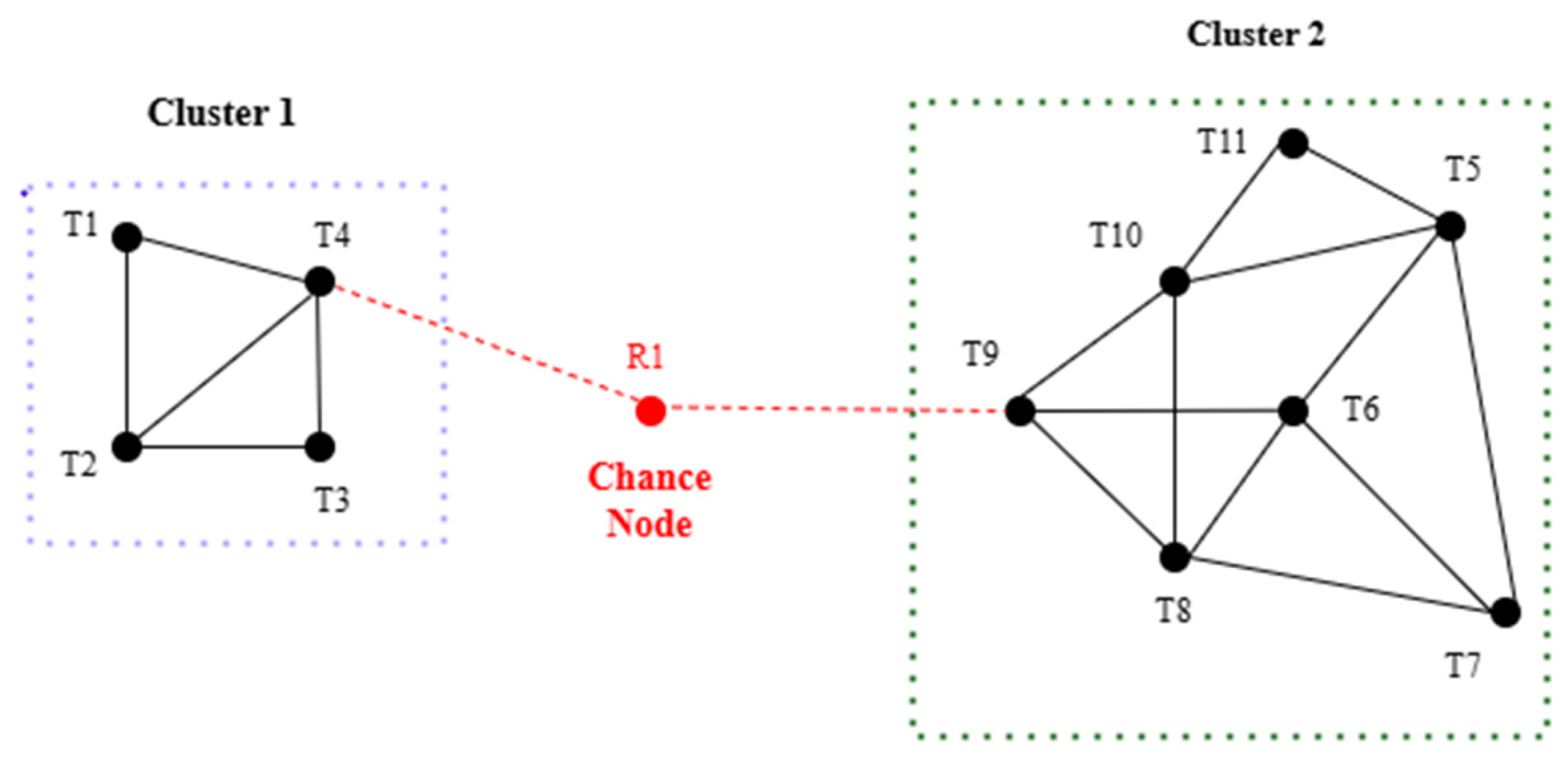

In terms of technical implementation, the KeyGraph algorithm produces a graph structure by analyzing co-occurrence relationships between keywords, where nodes represent keywords and edges indicate the strength of these co-occurrences. As depicted in

Figure 2, the concepts of black and red nodes are further introduced to describe this structure precisely. Black nodes represent high-frequency keywords with strong connections to fundamental concepts. These nodes are responsible for the interpretability of the knowledge structure, serving as the backbone of the knowledge graph and the foundational structure of KeyGraph. Typically, multiple black nodes form clusters that contain latent topics embedded in the articles. Red nodes are keywords with lower frequencies but strong co-occurrence relationships with multiple clusters. They are often metaphorically associated with chance discovery, reflecting atypical yet potentially valuable keywords in articles, called chance nodes in this work. Black edges represent strong co-occurrence relationships between black nodes, forming stable keyword clusters via their connections. Red edges denote bridging relationships between red nodes and clusters, highlighting the value of rare events [

10,

37,

38].

A distinctive feature of the KeyGraph algorithm is its ability to extract key concepts and their associations automatically from articles, revealing implicit relationships between these concepts. Generating visualized knowledge graphs uncovers latent and significant information in articles, enabling users without a technical background to comprehend the complex structures and interrelations of keywords intuitively [

37,

41,

43] (

Figure 2).

2.4.2. KeyGraph Algorithm

Data preprocessing: Data preprocessing serves as the foundation for constructing a keyword network in the KeyGraph algorithm. In this study, this phase involves several steps, including tokenization, normalization, stop-word removal, and part-of-speech filtering. Tokenization and normalization establish a stable keyword base, whereas stop-word removal and part-of-speech filtering reduce semantic noise, enhancing the accuracy of co-occurrence analysis and the network structure quality, optimizing the performance of topic detection and chance node identification [

38,

44,

45].

High-frequency keyword extraction: Based on the preprocessed data, a new dataset

, is generated, comprising a series of sentences, each representing a set of keywords. All keywords are ranked according to their frequency of occurrence in dataset

, and the highest-frequency keywords are selected to form a high-frequency keyword set. These keywords serve as the nodes of the network cluster

[

38,

44,

45,

46].

Calculation formula for keyword network co-occurrence: In the KeyGraph algorithm adopted in this study, the co-occurrence relationship between keywords serves as the core basis for constructing the keyword network. Each keyword is regarded as a network node. When two keywords co-occur in the same semantic unit (e.g., a sentence or paragraph), a link (edge) is formed between the nodes. The KeyGraph algorithm employs a specific measure called the co-occurrence strength to quantify the co-occurrence relationship between keywords [

38,

47,

48], calculated in Eq. (1):

where

represents the co-occurrence strength between keywords

and

in all semantic units

in dataset

This measure is calculated by summing the minimum occurrence frequencies of the two keywords in the same semantic unit, reflecting their co-occurrence count. In addition,

and

denote the frequencies of keywords

and

, respectively, in the semantic unit

indicates the minimum occurrence frequency between

and

in the semantic unit

This metric aggregates the minimal occurrence counts across semantic units to capture the overall semantic linkage strength between the keyword pair. This approach helps construct a semantic backbone comprising high-frequency terms and reveals latent nodes that may have lower surface frequencies yet critical semantic significance.

In addition to the absolute co-occurrence values described above, studies often employ normalized indicators of co-occurrence strength, such as the Jaccard similarity coefficient, as a relative measure [

38], calculated in Eq. (2):

where

indicates the number of times the keywords

and

co-occur in the same semantic unit in dataset

, and

refers to the total frequency of either

or

appearing in dataset

. The value of the

Jaccard similarity coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, where a higher value represents a stronger similarity between keywords, implying greater semantic similarity. As a normalized similarity measure, the

Jaccard similarity coefficient can be employed to adjust the edge weights in the network generated by the KeyGraph algorithm, mitigating the linking bias caused by high-frequency terms and enhancing the performance of the keyword network in topic detection and keyword identification. This approach helps reveal the relational paths in the deeper semantic structure more effectively.

- 4.

Co-occurrence measurement between keywords and keyword clusters: The KeyGraph algorithm employs the Co-Occurrence Strength Index called

, which measures the degree of their co-occurrence within articles to calculate the connection strength between a keyword

and a single keyword cluster

[

38,

47,

48], as in Eq. (3):

where

refers to a retained keyword in the preprocessed dataset

,

denotes the cluster to which the keyword belongs, and

represents the dataset obtained after preprocessing. The co-occurrence strength is calculated based on sentences

, the fundamental semantic units, and the sentences are typically treated as sets of keywords that form the basis for defining co-occurrence relationships. In addition,

indicates the frequency of keyword

appearing in sentence

, whereas

represents the total number of occurrences of all keywords in cluster

, excluding

in the same sentence

. This value is zero if no other keywords from the cluster appear in the sentence.

This formula processes each sentence in datasetto determine whether the target keyword appears. If it does, this formula calculates the frequency of keyword and multiplies it by the total frequency of the other keywords in cluster (excluding) in the same sentence. The resulting products are summed across all sentences to quantify the overall co-occurrence strength between keyword and cluster .

- 5.

Calculating the co-occurrence potential of all keywords in cluster: In a keyword network analysis, the association between a keyword and the keyword cluster

depends on the degree of co-occurrence and the contextual interactions between the cluster and other keywords. The KeyGraph algorithm provides a standardized metric for evaluating such associations by defining a cluster-level semantic quantification measure called

, estimating the potential of a specific keyword cluster

to interact semantically with other keywords throughout the dataset [

38,

47,

48], calculated in Eq. (4):

where

represents each sentence in dataset

, which is regarded as a set of co-occurring keywords and is the basis for defining co-occurrence relationships between keywords. In addition,

denotes the set of all keywords,

indicates any keyword in set

,

refers to the frequency of keyword

appearing in sentence

, and

denotes the total frequency of all keywords in cluster

(excluding keyword

) appearing in the same sentence

. This value is zero if none of the keywords in the cluster appear in the sentence.

This formula traverses each sentence in dataset and, for each keyword in the high-frequency keyword set , calculates its co-occurrence strength with other keywords in cluster when appears in the sentence. These co-occurrence values are summed, and this equation measures the total co-occurrence strength between keyword cluster and keywords in setacross dataset D. A higher value indicates that clusterhas a stronger connection with high-frequency keywords in the keyword network, which may suggest its potential significance in the semantic structure.

- 6.

Evaluation of the importance of the potential of keywords across clusters: This study adopts the keyness calculation formula proposed in the KeyGraph algorithm to evaluate the connective role played by keyword

in the overall keyword network graph to determine whether a specific keyword possesses the semantic potential to bridge clusters [

38,

47,

48], as computed in Eq. (5):

where

represents the importance score of keyword

, ranging between 0 and 1, and

denotes the set of all keyword clusters in the keyword network graph, where each

refers to an individual keyword cluster. The expression

indicates that every cluster in set

is evaluated individually to compute the semantic relevance of keyword

to each cluster. Moreover,

refers to the co-occurrence strength between keyword

and cluster

, whereas

represents the total co-occurrence strength of cluster

.

This formula represents the product of the co-occurrence complement of keyword with each keyword cluster , indicating the overall probability that keywordhas no co-occurrence association with various keyword clusters. The final score is obtained by subtracting this product from 1, reflecting the importance of keywordin bridging multiple clusters in the keyword network.

When keywordexhibits significant co-occurrence relationships with multiple keyword clusters, its score approaches 1, indicating that keyword is highly associated with multiple keyword clusters and may represent a potential chance node. Conversely, when approaches 0, keyword may have little to no co-occurrence with keyword clusters, reflecting a lower importance in the keyword network structure.

3. Materials and Methods

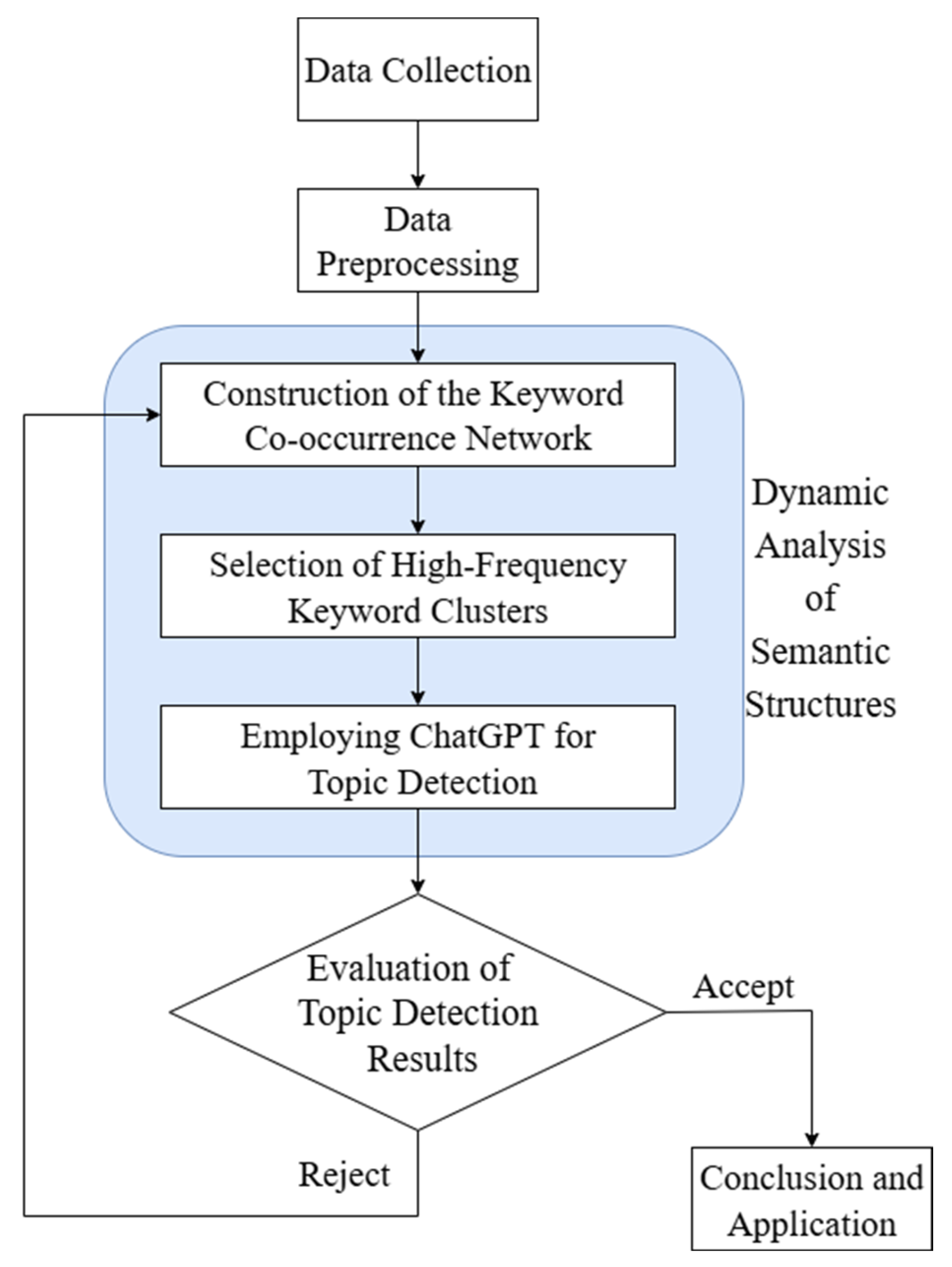

The research process is divided into the five stages at the beginning of

Figure 3.

3.1. Data Collection

The data collection method in this study primarily employs the search terms

AI ethics, ethical AI, and responsible AI, focusing on the overall concepts and frameworks related to AI ethics, cross-industry universal guidelines, and globally influential and controversial problems, while avoiding biases toward specific industry applications. Moreover, AI ethics emphasizes moral principles at the technical level, addressing ethical issues in the design and operation of AI systems [

49]. Ethical AI concerns the implementation of ethical principles in the development and application of AI technology, ensuring compliance with moral standards [

50]. Responsible AI highlights the responsibilities and regulations of developers and users regarding the social influence of AI technology, promoting accountability and governance [

51]. These three concepts are complementary and synergistic, facilitating an in-depth exploration of the ethical challenges faced by AI and advancing discourse on its practical applications and social responsibilities toward greater depth and breadth.

This study prioritizes the selection of reports and articles related to AI ethics published in English between 2022 and 2024 via online searches to emphasize data timeliness and capture recent developments in the field. The aim is to clarify the perspectives and latest trends in AI ethics discourse systematically against the background of rapid AI technological evolution during this period (see

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

A rigorous screening process was conducted during the data collection phase to ensure the comprehensiveness and authority of the research data. Data sources were limited to internationally recognized and credible academic research institutions, news media, and nonprofit organizations. Articles focusing solely on a single domain or industry application were excluded, prioritizing comprehensive reports reflecting international trends. This approach aimed to ensure that the data adequately represent diverse global perspectives and contentious issues regarding AI ethics, constructing a neutral and macro-level article dataset. Eight highly comprehensive and interpretative articles were selected for each year as the analytical corpus for the KeyGraph-based topic detection and chance exploration.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

This study employs the KeyGraph algorithm to extract topics from articles, based on co-occurrence relationships between keywords, and constructs a structured visual graph. However, the original articles often contain numerous stop words, irrelevant information, and punctuation marks. If the articles are analyzed directly using the KeyGraph algorithm without preprocessing, extracting the associations between keywords becomes difficult, resulting in overly cluttered or off-focus keyword networks. This study segments sentences, tokenizes words, and filters out meaningless words and stop words prior to analysis to enhance the accuracy of keyword identification and reduce graph noise, ensuring the accuracy and visualization quality of the keyword co-occurrence network graph.

This study employs Python combined with the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) for article preprocessing during the data processing phase to achieve the objectives. First, each collected article was segmented into independent sentences based on periods, and each sentence was converted to lowercase and tokenized into individual words while removing punctuation marks but retaining contractions containing apostrophes (e.g., in the work don’t). The stopword functionality for NLTK was used to filter out semantically insignificant words (e.g., the, is, and and) to reduce data noise and highlight keywords related to AI ethics. The filtered word list was written line by line into output files with the words separated by spaces. A manual review and filtering process was also conducted to remove any remaining irrelevant words and tokenization errors to enhance the thematic relevance of the data. This process effectively streamlines the data, improves keyword prominence, and establishes a structured data foundation for the keyword network of the KeyGraph algorithm, ensuring the accuracy and visualization quality of the analyses.

3.3. Construction of the Keyword Co-Occurence Network

3.3.1. Chance Discovery in AI Ethics Using KeyGraph

This study employs the graph-based KeyGraph text mining technique as the core tool for topic detection and chance discovery in AI ethics articles to overcome the limitations of traditional text mining methods in analyzing topic evolution and identifying latent issues. As described in

Section 2, KeyGraph is a keyword network analysis method that integrates lexical co-occurrence structures with chance identification. By constructing a co-occurrence graph of keywords, KeyGraph reveals the intrinsic topic structures and semantic linkages in articles, making it suitable for exploring cross-topic or dynamic contexts and emerging keywords. A distinctive feature of KeyGraph is its ability to identify low-frequency but highly connected chance nodes linked to multiple topic clusters, uncovering latent issues that traditional high-frequency analyses often fail to capture. The KeyGraph analytical process can be divided into the following five core strategies, serving as the foundation for semantic mining and topic detection in AI ethics articles:

Keyword frequency and co-occurrence calculation: First, the occurrence frequency of all words in the articles is calculated and sorted. The top consecutive high-frequency words are selected as keywords, representing the core foundational concepts of the articles. Using paragraphs or sentences as the calculation units, the co-occurrence relationships between all keywords are computed and applied to establish connections.

-

Node role classification and keyword clustering: Based on the frequency of keyword occurrences and their structural positions in the co-occurrence network, nodes are classified into three categories, which lays the foundation for chance discovery.

- ○

High-frequency keywords: Keywords with high occurrence frequency that are concentrated in specific topic clusters represent the primary concepts of the topics. In this study, these are consistently represented by high-frequency black nodes.

- ○

Chance keywords: These keywords (known as bridging words) have lower occurrence frequencies but are associated with multiple topic clusters. They typically indicate emerging concepts or interdisciplinary issues and are valuable for discovering latent topics. In this study, they are represented by red nodes.

- ○

General terms: Keywords lacking structural significance are excluded from the visualization network.

Keyword co-occurrence network construction and thematic cluster identification: A keyword association graph is constructed with keywords as nodes and the co-occurrence strength as weighted edges. This method aggregates high-frequency terms and forms thematic clusters.

Keyword network visualization: The nodes and links are visualized using tools (e.g., Polaris), which map co-occurrence relationships between keywords to construct their association network graphs. By adjusting parameters (e.g., frequency thresholds, co-occurrence strength, and the number of nodes), different levels of keyword structures are explored to enhance the understanding of potential keyword clusters and association pathways.

In the practical implementation, this study preprocesses the articles, including word segmentation and stopword removal, and segments them according to the time series from 2022 to 2024 to observe changes and shifts in potential topics or issues over time. The Polaris visualization tool was employed in combination with statistical methods (e.g., word frequency and co-occurrence analysis) and data mining techniques to execute the KeyGraph algorithm [

52], which automatically calculates the keyword co-occurrence frequency and co-occurrence strength. This tool constructs a keyword network graph to explore keyword structures at various levels, promoting semantic interpretation and chance discovery. In the network, high-frequency black nodes represent keywords with a high frequency and stable semantic cores, whereas red nodes represent potential keywords with lower frequency but strong connections to multiple topic clusters. Black edges between nodes reflect the co-occurrence strength between keywords.

This study applies the parameter adjustment functions provided by Polaris to identify an appropriate keyword network structure and dynamically set conditions (e.g., keyword frequency thresholds, co-occurrence link strength, and maximum number of nodes), controlling the hierarchical levels and cluster partitioning of the keyword network graph. This approach enhances the structural clarity of the visualization, facilitating a comparative analysis and interpretation of the keyword networks across years and enabling further observation of the formation, expansion, and evolution of topic clusters.

This method reveals the explicit topic structures in AI ethics articles and can uncover potential low-frequency keywords and emerging issues that traditional techniques often fail to capture, providing a solid foundation for topic detection and chance discovery. Overall, by integrating keyword co-occurrence structures, latent chance nodes, and visualization tools, KeyGraph effectively extracts explicit and implicit issues in articles, enhancing the exploratory and strategic aspects of topic detection.

However, the interpretive precision of the keyword network graph and the clarity of topic detection often depend on the number of high-frequency black nodes and the ratio between high-frequency black nodes and red chance nodes. An excessive or insufficient number of these nodes may affect the semantic clarity and accuracy of topic detection, influencing the reliability of the analytical results. The following section analyzes the relationship between semantic node density and the effectiveness of topic detection, investigating the effect of node density on the keyword structure and topic differentiation.

3.3.2. Analysis of Keyword Network Node Density and Topic Detection Accuracy

When conducting a KeyGraph keyword network analysis, setting too many high-frequency black nodes (e.g., designating 100 out of 1,000 (10%) distinct terms as black nodes) may lead to an overly complex network structure, adversely affecting the accuracy and focus of topic detection. In KeyGraph, high-frequency black nodes represent the core terms in the keyword network, outlining the principal thematic structure of the articles. However, when the number of high-frequency black nodes is too large, the co-occurrence density of high-frequency keywords increases significantly, resulting in an overly dense network. This density can blur thematic boundaries, intensify the semantic overlap between nodes, and hinder the convergence of co-occurrence paths, weakening the ability to detect latent topics and contextual structures [

53,

54,

55,

56].

Second, an excessive number of high-frequency terms may include morphologically varied but semantically similar words (e.g., make, makes, and made). Although these high-frequency terms frequently co-occur, they may lack clear thematic referentiality, disrupting the focus of the keyword network. This disruption often leads to topic analysis results that are biased toward overly generalized dominant themes or may even trigger semantic hallucinations, limiting the ability to identify subtle, overlapping, or emerging topics [

53,

54,

55,

56].

From an operational perspective, setting too many high-frequency black nodes can lead to an overly complex graph structure, reducing the feasibility of cluster partitioning and cross-validation and increasing the difficulty of topic analysis. This outcome may result in the omission of critical information during topic summarization or affect the interpretability of the detection process, weakening the depth and novelty of the conclusions. Conversely, setting too few high-frequency black nodes may cause essential topic-related keywords to be inadequately captured. In particular, some secondary terms (although not highly frequent) may carry significant semantic meaning but be excluded from the analysis, leading to an unbalanced topic distribution. This outcome compromises the formation of structured keyword clusters, dilutes the network core, and undermines the coherence of the keyword network and the overall inference of topic evolution.

In summary, determining the optimal number of key nodes requires iterative parameter tuning and visual inspection to control node density appropriately and identify the most suitable keyword network. This approach helps maintain the structural stability of the keyword network, reducing the risk of overlap and semantic hallucination in the topic analysis and enhancing the overall interpretability and exploratory depth of the analysis.

3.4. Selection of High-Frequency Keyword Clusters

After constructing the keyword network, this study conducts manual classification and clustering based on the network structure formed by the high-frequency black nodes. The initial clustering process employs the chance nodes (i.e., red nodes), identified by the KeyGraph algorithm, as the starting points for keyword diffusion. These red nodes are considered anchors for potential emerging or latent themes due to their role in bridging high-frequency keywords despite having a relatively low frequency themselves. From each red node, the diffusion extends outward to directly connected high-frequency black nodes, with the number of connected black nodes limited to a maximum of six to seven per red node. This setting helps control the cluster size and prevents excessive expansion that may blur or overgeneralize the results of the topic analysis.

After completing the initial clustering, each cluster was input into ChatGPT for topic detection and semantic interpretation. ChatGPT analyzes the complex relationships between the keywords in each cluster and infers the potential ethical issues or discourse associated with the cluster. If the interpretations generated by ChatGPT lack logical coherence or sufficient semantic clarity, researchers can adjust the relevant parameters of the KeyGraph algorithm (e.g., the number of high-frequency black nodes, connection strength, or red nodes) to reconstruct a new keyword structure and cluster distribution. This dynamic human–AI collaborative adjustment mechanism is iteratively repeated until the resulting cluster division demonstrates semantic clarity and structural coherence.

Overall, this procedure embodies a human–AI collaborative mechanism for semantic construction. The KeyGraph algorithm segments clusters based on the proximity of red nodes and high-frequency black nodes, considering their co-occurrence. In contrast, ChatGPT provides complementary support for semantic interpretation, and researchers can manually adjust parameters to ensure coherence. This approach reflects the core aim of HCI in the double helix model, forming a dynamic and iterative process of topic analysis that enhances the semantic focus and ensures the structural integrity of the keyword network.

3.5. Employing ChatGPT for Topic Detection

This section elaborates on how the KeyGraph algorithm is employed to conduct topic detection and chance discovery in AI ethics articles while examining the limitations of traditional keyword network analysis methods. This work employs ChatGPT as an auxiliary tool for semantic interpretation to overcome these constraints during the potential topic detection phase of keyword clusters. The technical advantages and application strategies of this integration are detailed below.

3.5.1. Limitations of Previous Methods

Before the widespread adoption of LLMs, such as ChatGPT, article mining for keyword networks and topic detection primarily relied on interpreting the semantic relationships between node clusters and bridging chance nodes in the keyword network graph. Researchers subjectively assigned thematic meanings to the keyword structures and topics based on these relationships. Researchers needed to trace the data back to the original article and examine the contextual usage for semantic interpretation to clarify the semantic association of a bridging node (e.g., accountability) with multiple clusters [

57,

58,

59,

60]. In this analytical framework, topic detection and semantic clarification were achieved primarily through the following approaches.

Topic cluster identification and core concept summarization: KeyGraph identifies high-frequency keywords in articles and designates them as high-frequency nodes (i.e., black nodes) in the keyword network structure. Based on the co-occurrence relationships between these keywords, tightly connected clusters naturally form, reflecting the primary themes or subdomains in articles. Researchers can summarize representative thematic labels based on the characteristics and co-occurrence patterns of keywords in each cluster, producing an initial thematic summary and classification of the core article content.

Chance keyword identification and pairwise semantic relationship mining: The uniqueness of KeyGraph lies in its ability to identify chance keywords that, despite their low frequency, connect multiple thematic clusters. Although these keywords appear infrequently, they serve as bridging nodes linking thematic clusters in the keyword network. Researchers conduct in-depth analyses of these chance keywords by tracing their contextual usage back to the original articles, manually interpreting their semantic roles and how they connect with multiple thematic clusters. This process facilitates identifying emerging topics, interdisciplinary integration points, or potential trends.

However, although KeyGraph can provide structural information and identify potential chance keywords, without LLM assistance, theme summarization and semantic clarification still heavily rely on manual interpretation and domain-expert knowledge. Researchers must manually integrate the keyword network graph, centrality metrics, and the contextual usage of terms in the original articles to trace and interpret the semantic roles of potential keywords and their connections to multiple thematic clusters. This process is time-consuming, and the results are often limited by the researchers’ professional judgment, reducing the efficiency and scalability of semantic mining. These traditional methods commonly face several significant limitations [

59,

60].

Topic summarization heavily relies on manual interpretation, resulting in subjectivity and inconsistency: Although traditional keyword network graphs can visually present co-occurrence relationships between high-frequency keywords, their semantic connections often lack systematic explanatory mechanisms, typically relying on researchers’ expertise and experience for semantic interpretation and topic detection. This process is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and prone to inconsistencies due to variations in interpreters’ knowledge, affecting the objectivity of topic summarization. These problems become pronounced when analyzing multiple articles or conducting comparative analyses over time.

Limited ability to identify low-frequency, high-value keywords, making latent topic detection difficult: Traditional text mining methods using statistical frequency focus on topic clusters formed by high-frequency keywords, often overlooking low-frequency keywords and chance nodes that play bridging or transitional roles in the keyword structure. These low-frequency keywords often represent emerging concepts, topic intersections, or contextual shifts, holding significant value for uncovering latent research topics and policy chance information. However, traditional methods struggle to identify and interpret their semantic roles systematically, limiting the efficiency and usefulness of topic exploration.

Difficulty tracking dynamic contexts hinders automating topic-evolution pattern analysis: When managing cross-temporal texts, such as AI ethics articles from 2022 to 2024, traditional keyword network analysis often requires a manual comparison of keyword structural changes at various time points and cannot effectively or automatically track how topic keywords undergo semantic shifts or experience topic merging and splitting as the context evolves. This limitation hinders researchers’ understanding and forecasting of topic evolution trajectories, resulting in analyses without the capacity to present temporal and dynamic characteristics.

Visualization maps are challenging to convert into structured data for inference: Although keyword network graphs offer a high degree of visual intuitiveness and help reveal thematic contexts and lexical and relational structures in texts, their results are often presented as images. When the number of keyword nodes in topic clusters is high, the clarity and readability of these visuals significantly decrease, leading to blurred outcomes or difficulty in interpretation during advanced analyses (e.g., topic classification, semantic comparison, or cross-validation).

3.5.2. Technical Background: Semantic Comprehension and Topic Extraction in ChatGPT

The ChatGPT LLM is based on the deep learning transformer architecture that Vaswani et al. proposed in 2017. Unlike the widely used LDA, this model undergoes unsupervised pretraining on large-scale textual data to generate high-dimensional semantic embeddings, capturing the syntactic structures and semantic relationships in sentences. Its core self-attention mechanism captures semantic associations and contextual features in the text, transforming textual data into semantic vector representations to infer deep linguistic patterns and latent word relationships. In practical applications, ChatGPT demonstrates capabilities in processing long texts, generating summaries, and performing topic detection.

The experimental results from existing studies indicate that ChatGPT achieves highly accurate content detection and classification tasks, significantly surpassing the current benchmark methods. Notably, ChatGPT displays outstanding performance in zero-shot learning scenarios. The literature has suggested that ChatGPT can directly understand and execute most tasks without any additional training or fine-tuning, with performance typically exceeding that of other mainstream LLMs, demonstrating exceptional generalizability. Moreover, studies have found that, in specific tasks, the performance of ChatGPT surpasses even that of fine-tuned models. This finding highlights the potential of ChatGPT as a foundation model, achieving or exceeding the performance of task-specific trained models without special optimization, highlighting stronger adaptability and broader application prospects [

61,

62,

63,

64].

This study integrates ChatGPT into the topic detection and summary generation tasks of the keyword networks produced by KeyGraph to apply the semantic analysis potential of KeyGraph fully and overcome the limitations of traditional manual interpretation. When the structure of the keyword network, particularly starting from the red nodes, is expanded layer by layer based on the connection strength and semantic distance with high-frequency black nodes, the corresponding original texts are input into ChatGPT individually. This LLM employs the following steps to conduct semantic interpretation and topic detection processes [

64,

65,

66]:

Comprehension of keyword network structures and semantic interpretation: ChatGPT tokenizes the input text, including the original AI ethics articles and translated descriptions of the KeyGraph keyword network structure, and processes it via its multilayer transformer model for deep syntactic and semantic analyses. The built-in attention mechanism in ChatGPT accurately captures complex relationships between tokens and their contextual meaning, constructing a comprehensive, detailed semantic representation. This approach enables the model to understand the meaning of individual tokens and their positions and roles in the keyword network.

Topic identification: The model identifies frequently recurring keywords and their semantic relationships in the text, grouping them into coherent thematic clusters. Notably, ChatGPT applies its strong contextual reasoning to generate semantically complete and representative thematic descriptions, facilitating the discovery of core concepts in the network structure.

Semantic interpretation and text summarization: ChatGPT extracts critical insight from text based on semantic logic and generates contextually coherent and concise summaries. Researchers can control the content and length of these summaries using precise prompt engineering (e.g., restricting the summary to the imported text) to meet specific analytical requirements. This control considerably enhances the efficiency of extracting insight from complex network graphs [

66,

67].

Through these steps, this study expands the keyword network structure constructed by KeyGraph layer by layer, starting from the red nodes and analyzing their associations with the high-frequency black nodes. Then, this study employs ChatGPT to interpret the natural language and summarize the themes of the topic clusters and bridging nodes of the original AI ethics articles. This integrated process significantly enhances the analytical efficiency and accuracy of thematic induction, realizing the HCI and semantic reciprocal interpretation emphasized by the chance discovery theory and providing a more systematic and operable framework for dynamic topic detection.

3.5.3. Method: Integrating KeyGraph and ChatGPT for Topic Detection

The KeyGraph application emphasizes that mining, understanding, and topic detection should be conducted and interpreted by domain experts to ensure the contextual relevance of the keyword network interpretation. However, given the limited availability of domain experts, this study integrates the KeyGraph keyword network analysis with ChatGPT to enhance the semantic interpretability of detected topics and the ability to determine potential chances by constructing keyword association structures and exploring the topics. The analysis process begins with the KeyGraph algorithm generating a keyword network graph based on the co-occurrence frequency and distance between keywords, identifying potential cross-topic connective chance nodes (red nodes), which serve as the starting points for semantic expansion and topic detection.

Using the red nodes as the starting points for semantic diffusion aligns with the core aim of the chance discovery theory. Although these nodes have a relatively low frequency, they form connections with multiple clusters, displaying cross-topic bridging characteristics and capturing hidden information more effectively. Furthermore, although these nodes may not represent the focus of the texts, they can reveal potential topics at the boundaries of the keyword network, offering high informational value and strategic significance.

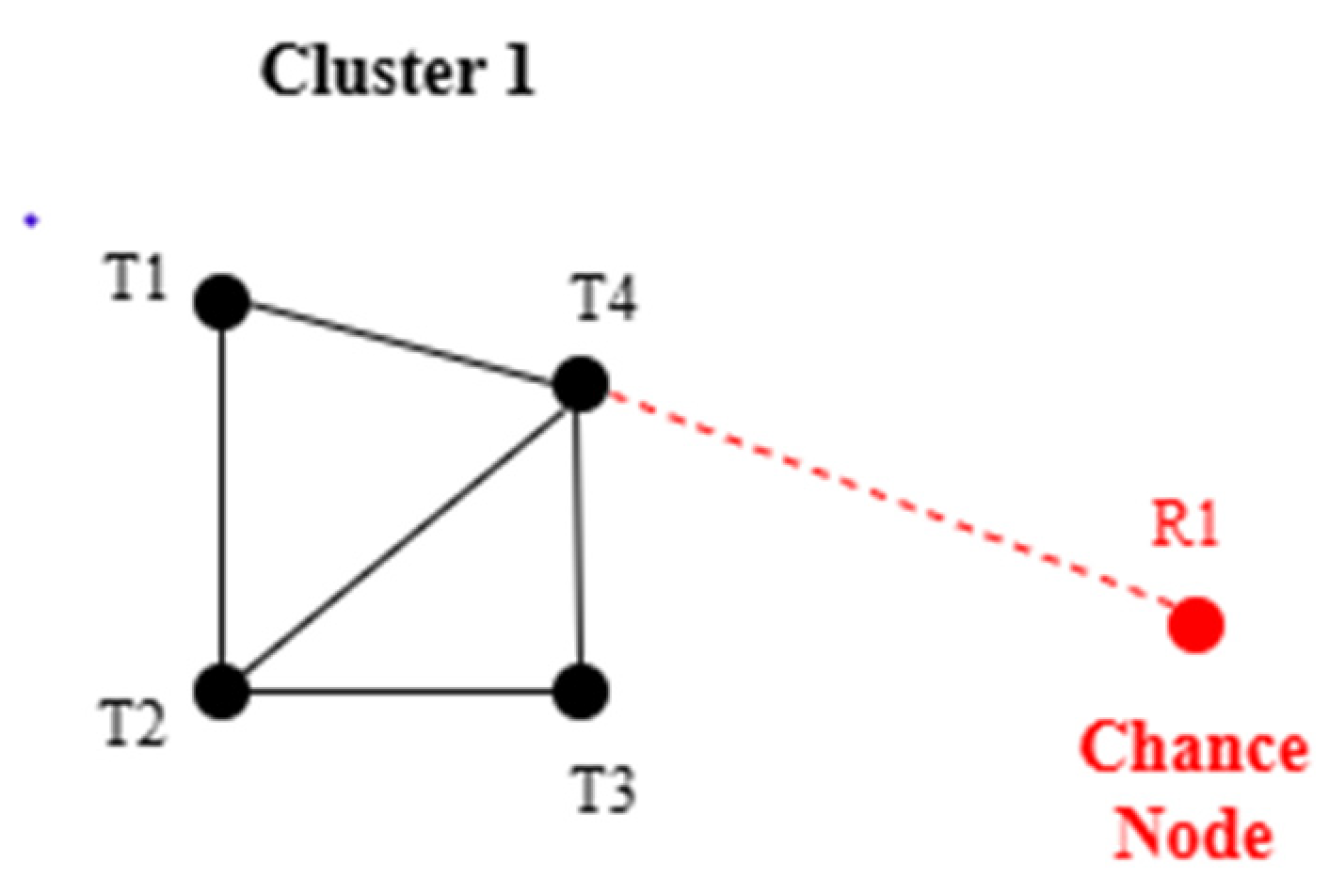

For example, starting from the red node R1, a strong co-occurrence relationship exists between R1 and the high-frequency black node T4, which connects to other high-frequency black nodes (e.g., T1 and T3), with T3 linking to T2. Notably, T2 forms a closed-loop connection with both T1 and T4. This hierarchical node expansion enables the construction of a structured semantic diffusion path, delineating the internal relationships and boundaries of a topic (

Figure 4).

This study integrates the ChatGPT model with an HCI mechanism to apply the semantic diffusion structure to semantic inference and topic interpretation tasks, enhancing the semantic accuracy and interpretative consistency of topic understanding. The keyword clusters identified by KeyGraph are reconstructed into logically coherent semantic diffusion paths, with red nodes serving as the starting points for interpretation. These paths are input into ChatGPT, which is guided to perform semantic judgment and topic mining based on the provided semantic diffusion path.

Figure 4 presents an input example, the R1 semantic diffusion path, where the red node is R1 and the high-frequency black nodes in Cluster 1 include T1, T2, T3, and T4.

3.6. R1 Semantic Diffusion Path

The co-occurrence structure in Cluster 1 consists of the following edges: {(R1, T4), (T4, T1), (T4, T2), (T4, T3), (T1, T2), (T2, T3)}. Although this method integrates the KeyGraph algorithm with ChatGPT for topic detection and semantic interpretation, practical implementation still faces challenges. As an LLM, ChatGPT’s outputs may exhibit risks, including semantic hallucination, topic ambiguity, or semantic overextension. This study adopts a dual-layer control strategy to mitigate these biases effectively [

68].

The first layer employs a refined prompt engineering mechanism to guide ChatGPT to focus on topic inference in a specific context, ensuring that the generated semantics rely solely on the semantic diffusion path and imported textual data. In this process, researchers initially use role-playing prompt strategies to assign ChatGPT a particular identity or perspective. This initial setting helps to converge the model’s understanding of the specific domain or context before topic inference, aligning its behavior more closely with expectations and enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of tasks. Clear task assignments are given to direct ChatGPT to perform various functions, including topic classification, semantic interpretation, or summary generation. Throughout the process, researchers control the scope of contextual input, restricting the topic summary content to the imported textual data, compensating for ChatGPT’s potential limitations in domain-specific knowledge and reducing the influence of semantic hallucinations on the interpretative results.

The second layer involves a repetitive manual review. The topic interpretation results generated by ChatGPT are subject to manual examination and validation by researchers. The aim is not to perform a word-for-word comparison of the semantic interpretations but to assess and revise the logical coherence and consistency of the topic summaries to ensure semantic logic and interpretative consistency. Researchers can adjust the algorithm parameters based on the review outcomes to conduct the next iteration of analyses, progressively refining and optimizing the semantic structure and topic detection results.

This risk management mechanism balances generative capability with interpretative reliability, illustrating the dynamic optimization loop of data-driven insight combined with knowledge reasoning, as described in the double helix model, facilitating incremental knowledge construction. By integrating keyword diffusion structures with HCI workflows, this study deepens the understanding and identification of latent topics. This approach enhances the sensitivity of topic detection and the accuracy of interpretation, improving the overall explainability of semantic analysis and its capacity to support decision-making.

This study conducts topic detection using keyword network graphs and keyword clusters generated by KeyGraph, supplemented by ChatGPT for topic interpretation and summary generation. Researchers interpret the results and make logical judgments, adjusting the model parameters to guide analysis iterations. This iterative process establishes an HCI mechanism for exploring topics and constructing knowledge.

Although the combined use of KeyGraph and generative AI demonstrates strong potential for topic detection and semantic interpretation, its practical implementation still faces challenges. As an LLM, ChatGPT’s outputs may involve risks, including semantic hallucination, topic ambiguity, or excessive semantic expansion. This study adopts a dual-layer control strategy to mitigate these biases. First, the generated semantics are constrained via refined prompt engineering to rely solely on the semantic diffusion paths and imported textual data. Second, a repeated manual review is conducted to enhance semantic consistency and logical thematic accuracy. This risk management mechanism balances generative capability with interpretative reliability, improving the overall explainability of the semantic analysis and decision support.

4. Result Analysis

This section presents a systematic analysis employing the Polaris visualization tool combined with the KeyGraph algorithm to analyze English-language articles related to AI ethics. The dataset comprises representative articles published between 2022 and 2024 by reputable academic institutions, news media, and nonprofit organizations providing comprehensive discourse. Eight representative articles for each year were selected for analysis to deepen the understanding of the evolving context of AI ethics issues and construct a structured keyword network supporting topic detection and interpretation.

Due to the numerous high-frequency black nodes in the initially generated keyword network, the analysis focused on those high-frequency black nodes with explicit connections (i.e., co-occurrence relationships represented by solid black edges). Isolated high-frequency black nodes without connections to other nodes were excluded from the keyword network. This approach improves the readability and relational strength of the keyword network and helps identify potential emerging chance trends.

Next, a structural analysis was conducted on the keyword network formed by these high-frequency black nodes, and keyword clusters were manually delineated. Clustering originated from chance nodes (red nodes) and expanded outward, with the number of linked high-frequency keywords limited to about six to seven per cluster. This process was supported by a keyword review and thematic convergence procedures to ensure semantic coherence and appropriateness within clusters. Following the preliminary clustering, the semantic diffusion paths for each keyword cluster were individually input into ChatGPT for in-depth topic detection and semantic interpretation, revealing the core topics embedded in each cluster.

Cross-cluster thematic integration analyses were conducted to explore latent common topics and interwoven keyword structures of strongly related clusters. All outputs underwent manual inspection to ensure the readability, reliability and logical consistency of the results. This process illustrates the HCI interpretative loop in the double helix model, where dynamic cycles of semantic network visualization, topic clustering, and generative AI-assisted interpretation collectively enhance the depth and explanatory power of topic detection.

4.1. Yearly Analysis of Topic Evolution and Keyword Structures (2022–2024)

The eight articles from 2022 contained 2,595 distinct terms; hence, this study set a parameter of 75 high-frequency keywords as black nodes, connected by 135 solid black edges depicting the co-occurrence network of these keywords to present the core associative structure of AI ethics topics. Additionally, four red nodes were designated as the potential chance discovery nodes. Under these conditions, a keyword network was generated using

automaker,

dignity,

behavior, and

statistical as the red nodes, highlighting the key themes in the 2022 AI ethics articles (

Figure 5). The following bullet points summarize the thematic content.

Cluster A-1: The semantic cluster around the red node automaker focuses on the implementation of autonomous driving technology and the ethical challenges faced by AI in automotive applications. This red node extends through its connection to self to include the keywords based, car, driver, vehicles, and autonomous, outlining application scenarios involving HCI. The keywords driver, task, and autonomous intertwine, reflecting issues of responsibility allocation and control authority. In situations where automated and manual control are combined, the attribution of responsibility for accidents (whether borne by the driver or system) requires further clarification via regulatory frameworks and technical design. Furthermore, task transparency and the interface design are also critical. For example, whether drivers can quickly grasp the operational status and decision rationale of the system directly affects their safety judgments and behavioral responses. Establishing trust and risk perception cannot be overlooked. An insufficient HCI design and information transmission may cause driver overtrust or erroneous reliance, increasing safety risks. Overall, the keyword structure emphasizes several topics, including the behavior prediction of autonomous technologies, system safety, and user responsibility attribution.

Cluster A-2: The red node behavior forms a keyword network related to AI risk prediction, system deployment, and ethical practices. Through its connections to consequences, the network gradually expands to include the keywords risk, privacy, discrimination, design, and capabilities, reflecting the multifaceted and uncertain outcomes of AI system behavior. Notably, discrimination is intertwined with risk, indicating that failure to address data sources and algorithmic bias properly in real-world applications may reinforce existing societal inequalities and trigger ethical crises of systemic discrimination. The association between design and foundational highlights the need to judiciously consider fundamental principles and ethical values during the initial stages of AI development. Overall, this cluster maps the potential externalities that may arise during AI deployment, emphasizing that developers must assume the corresponding responsibility for the potential social and ethical consequences of system behavior.

Cluster A-3: The keyword network extended from the red node statistical focuses on the computational logic and algorithmic architecture of AI systems. The strong co-occurrence relationships, with the keywords computational, learning, machine, critical, and implementation, reveals core problems including statistical biases, risk governance, and explainability in current AI technology. The direct and indirect connections between the keywords issues, concerns, ethical, implementation, and critical reflect that AI ethics is not merely a conceptual discussion but is involved in the development, design, and deployment stages of AI systems. Furthermore, the connections emphasize that the realization of AI ethics must integrate value judgments and ethical norms as essential foundations for technical practice. This cluster demonstrates the role of ethical issues in institutional frameworks, industrial applications, and technical design, indicating that ethical practice has become a critical factor that cannot be overlooked in the development of responsible technology.