1. Introduction

Condylar hyperplasia (CH) is characterized by

overgrowth of the mandibular condyle, which disrupts normal facial development. Histologically, this condition presents as an

increase in cell number and thickness within the soft condylar layers[1,2]. This overgrowth can lead to severe deformities because it can occur not only during growth and development but also in adulthood[

3]. Depending on its duration, type, and severity, CH can affect the

temporomandibular joint (TMJ) structures (condyle, disc, fossa) and the

mandibular ramus. This can result in

secondary vertical compensations in the maxilla and malocclusions with sagittal, transverse, and vertical implications[4]. The origin of CH may be linked to hormonal, traumatic, neoplastic, genetic, molecular, or functional factors[

5].

Condylar hyperplasia (CH) presents with varying vectors of alteration, leading to distinct clinical manifestations and associated complications. Three primary forms are recognized[

4,

6]:

Hemimandibular Elongation (HE)

This form is characterized by a horizontal vector of alteration, which shifts the mandible away from the sagittal midline. This results in consistent occlusal changes among patients. Its main etiologic factors are trauma and hormonal influences, often leading to onset during pre- and adolescence. HE also shows a higher female prevalence and is the most common form of hyperplasia.

Hemimandibular Hyperplasia

This type involves a vertical vector of alteration, producing three-dimensional growth on one side of the face without displacing the mandible from the mid-sagittal plane. Consequently, its occlusal characteristics differ significantly from HE. Its main etiologic factor is neoplastic growths, such as osteochondroma, and it is the least common of the hyperplasia.

Hybrid Form (HF)

The HF combines both horizontal and vertical vectors of alteration. This makes it a particularly severe and aggressive expression of the pathology.

Although human anatomy is not entirely symmetrical, anthropometric standards derived from population-based studies provide parametric thresholds to identify when a craniofacial asymmetry falls outside the normal range[

7]. When a patient's craniofacial anthropometric assessment (i.e., quantitative anatomical measurements) deviates from these parameters, facial asymmetry (FA) is evident, typically associated with mandibular deviation (MD)[

4].

In such cases, the midpoint of the mandibular symphysis extends beyond the sagittal midplane of the cranial structures. This deviation is linked to multiple etiological factors, including genetic[

8], neurological[

9], neoplastic[

10], molecular[

11], developmental[

12], environmental and traumatic[

13], functional laterognathism[

14], glenoid cavity asymmetry[

15], and condylar resorption[

16]. Such FA not only impacts bone and soft tissue structures but can also lead to alterations in extracranial structures, such as the cervical vertebrae.

The mandible and cervical spine are anatomically and functionally interconnected. This complex relationship is facilitated by shared muscle chains, including the sternocleidomastoid, suprahyoid, infrahyoid, and suboccipital muscles, as well as the hyoid bone. Furthermore, neurological connections between the trigeminal nerve and brainstem nuclei, which also regulate cervical functions, contribute to this interrelationship[

17]. The C1 (Atlas) and C2 (Axis) vertebrae form the craniovertebral junction, acting as the crucial transition between the brain and the rest of the cervical spine. This area is vital as it houses neural and vascular structures while allowing for significant spinal mobility. Most vertebral rotation, flexion, and extension occur between C1 and C2, while the intervertebral discs is located from the C2-C3 level downwards[

18].

Craniofacial alterations linked to FA have been thoroughly investigated, but research into

extracranial alterations remains in its early stages. A crucial question in a patient's comprehensive evaluation is how

MD affects neck posture and the position of the cervical vertebrae. This is especially relevant given that some scientific literature has established an anatomical-functional and pathophysiological connection between craniomandibular and craniocervical dysfunction, integrating them into a single tonic-postural system[

19].

In line with this, Guan

et al. [

20] and Nakashima

et al. [

21] have

postulated an inherent correlation between MD and cervical posture, affecting it three-dimensionally. Additionally, Cardinal

et al. [

22] noted a

positive correlation between posterior crossbite, a common feature of MD,

and deviation of the first cervical vertebrae.

However, the direct correlation between specific conditions that cause FA, such as CH, and associated vertebral changes remains unexplored. Furthermore, previous studies have neither differentiated cohorts based on the severity of MD nor segmented individual vertebrae to assess their behavior comprehensively.

Given that computed tomography (CT) has proven helpful in the morphological evaluation of anatomical structures, providing detailed views of their size, shape, and position from various angles and slices[

23], this study aims to evaluate the three-dimensional behavior of the upper cervical vertebrae to CH with severe MD, as observed in HE and HF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study, approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees of Clínica Imbanaco (CEI-856) and Universidad del Valle Faculty of Health (E 008-024). We retrieved CT datasets in DICOM format from the institutional repository, encompassing patients with a clinical diagnosis of FA who received care at Clínica Imbanaco between August 2015 and December 2023.

Our selection criteria for FA were based on the classification by López

et al. [

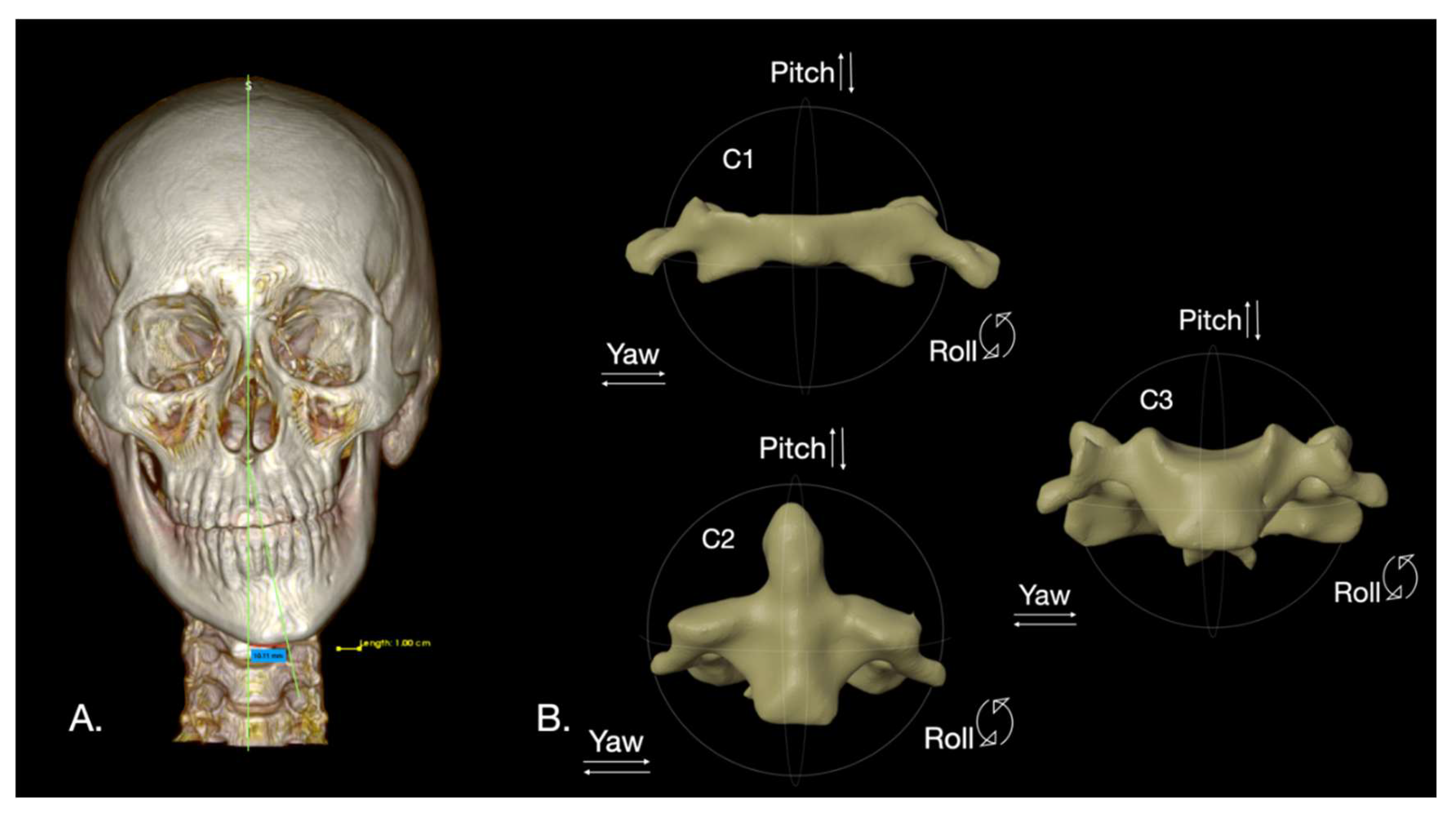

4] We specifically chose datasets from patients with

severe FA, defined as mandibular symphysis deviation of

6 mm or more from the sagittal midplane, caused by CH with a horizontal vector of alteration, such as hemimandibular elongation HE and hybrid form HF (

Figure 1A).

2.2. CT Acquisition and Reconstruction

All CT datasets were acquired using a Biograph mCT20 PET/CT system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) at Clínica Imbanaco. The imaging parameters included:

CT images were reconstructed using a homogeneous low-dose B26F filter for precise anatomical localization.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria and Side Definition

We excluded incomplete CT datasets and those from patients with a history of:

For consistency, the affected side was defined as the side with condylar overgrowth, and MD side was considered the contralateral side.

2.4. CT Dataset Segmentation

For each dataset, the skull, mandible, and cervical vertebrae (C1-C3) were segmented. A trained researcher manually selected hard tissue structures using the

Threshold tool within the

Segment Editor of the open-source software 3D Slicer (v. 5.8.1 r33241/11eaf62, USA). This selection was based on Hounsfield Units (HU) ranging from 140 HU to 5734 HU. Subsequently, a semi-automatic segmentation generated

Standard Tessellation Language (.stl) files for the merged skull and mandible, as well as for each cervical vertebra (

Figure 1B).

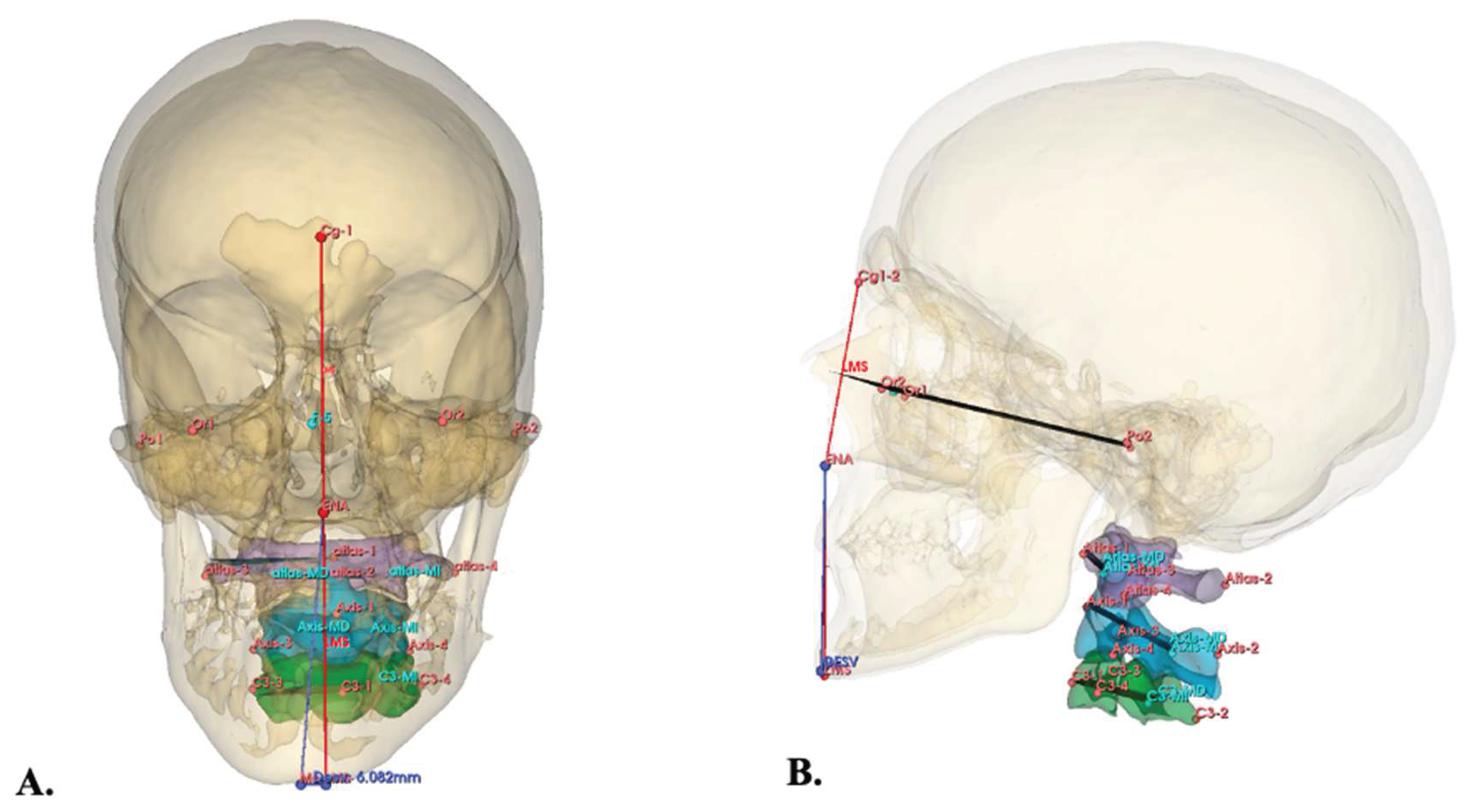

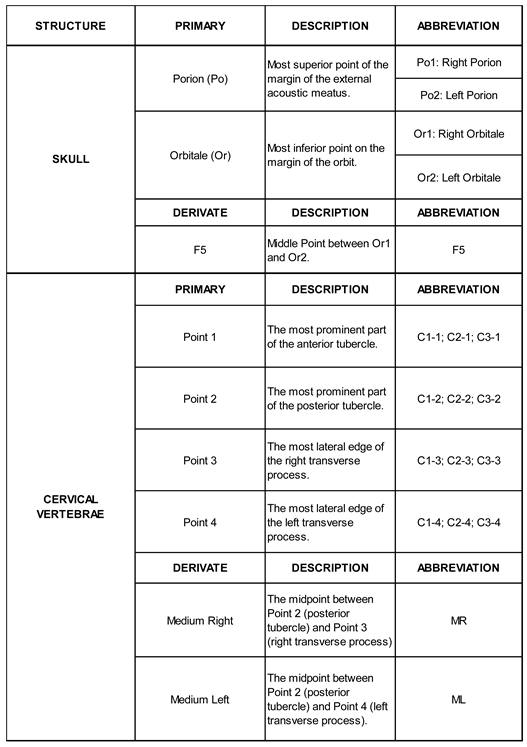

2.5. Cephalometric Landmark Selection

The

Frankfurt plane, serving as the reference, was established by placing four primary cephalometric landmarks on the skull using the

Markups module in 3D Slicer (

Table 1). Following this, primary cephalometric landmarks were similarly placed on the C1 (Atlas), C2 (Axis), and C3 vertebrae to define their respective planes of interest (

Table 1). To determine the

three-dimensional (3D) position of each vertebra based on Pitch, Yaw, and Roll angle deviations relative to the Frankfurt plane, the

Angle Planes module and the

Middle Point tool in 3D Slicer were utilized. Derivative landmarks were automatically generated by the software (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

2.6. Outcomes of Interest

MD was quantified in millimeters (mm) using the method described by López

et al. [

4] (

Figure 1). For the C1-C3 vertebrae, their 3D positions relative to the Frankfurt plane were recorded as Pitch, Yaw, and Roll angles in degrees (°). (

Figure 2).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

A single researcher (CMR) obtained all measurements. To assess intra-examiner agreement, 10 randomly selected CT datasets were re-measured after two weeks, with agreement evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Data are reported as Mean ± SD. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess data normality. Samples were divided into two groups based on the side of CH (right and left). The Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test, was used to compare outcomes of interest between these groups. Spearman correlation coefficient was used to calculate the correlation between MD and the 3D position of the vertebrae.

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 for macOS (Version 10.4.2/534). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

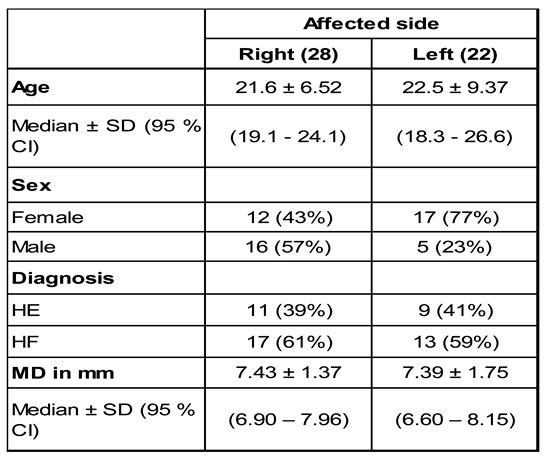

From an initial 247 revised CT datasets, we included 50 from patients with CH. The mean age was 22 ± 7.83 years, with similar mean ages for both right-sided CH (22.5 ± 9.37 years; n=28) and left-sided CH (21.6 ± 6.52 years; n=22). Females predominated in the left CH group (77%), while males were more frequent in the right CH group (57%). High-frequency (HF) was more common in both groups (59% left, 61% right) compared to low-frequency (HE) (41% left, 39% right).

When comparing right versus left CH, no significant differences were found for age (p=0.842), CH type (p>0.999), or amount of MD (p=0.729). However, there was a significant difference in patient distribution based on sex (p=0.021). (

Table 2)

To compare the groups based on the age and the amount of MD, the Mann-Whitney test was used, whereas, to compare the groups based on the distribution of the sex and the CH types, the Chi-square test (Fisher´s exact test) was used. Abbreviations: MD, mandibular deviation; HF, hybrid form; HE, hemimandibular elongation.

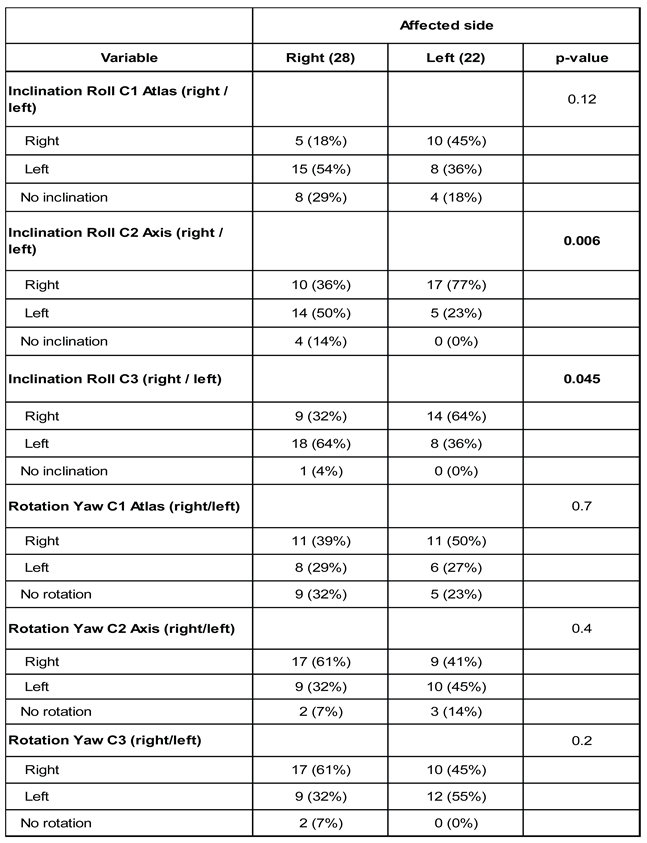

We evaluated the lateral inclination (roll) and axial rotation (yaw) of cervical vertebrae

C1, C2, and C3, classifying movements as rightward, leftward, or no movement, relative to the CH side. (

Table 3)

For C1, the lateral roll inclination pattern showed no statistically significant difference between groups (p=0.12). However, leftward inclination was more prevalent in the right CH group (54%), while rightward inclination predominated in the left CH group (45%).

At C2, we identified statistically significant differences in lateral roll inclination (p=0.006). Most patients with left CH presented C2 inclination to the right (77%), aligning with the side of MD. Conversely, leftward inclination predominated in the right CH group (50%).

Significant differences were also noted for C3's lateral roll inclination pattern (p=0.045). In both the right and left CH groups, 64% of patients exhibited lateral inclination toward the side of their MD.

Regarding axial rotation (yaw) movement, no statistically significant differences were observed in any of the three evaluated vertebrae (C1: p=0.7; C2: p=0.4; C3: p=0.2). However, there was considerable dispersion in rotation directions, with similar proportions across both groups. For example, 50% of the left CH group's C1 vertebrae rotated to the right, compared to 39% in the right CH group.

Pitch (Flexion/Extension)

Mean pitch angles were similar between right and left CH groups across all three evaluated vertebrae:

C1: 11.6° ± 7.26° (95% CI: 8.79–14.4°) in right CH versus 12.1° ± 5.40° (95% CI: 9.74–14.5°) in left CH.

C2: Higher in left CH (18.6° ± 5.53°) than right CH (16.0° ± 6.67°), though not statistically significant (p>0.05).

C3: Similar between groups (5.43° in right CH vs. 4.73° in left CH; p>0.05).

Yaw (Axial Rotation)

Axial rotation angles (yaw) displayed marked interindividual variability, with no significant association with the side of CH:

C1: 44.0° ± 54.7° (right CH) versus 46.6° ± 57.6° (left CH).

C2: 45.5° ± 54.2° (right CH) versus 59.4° ± 63.8° (left CH).

C3: 45.3° ± 54.4° (right CH) versus 19.5° ± 23.3° (left CH).

Roll (Lateral Inclination)

Roll angles were low and similar between groups, with no significant differences:

C1: 2.25° ± 2.49° (right CH) versus 2.41° ± 2.61° (left CH).

C2: 2.18° (right CH) versus 2.32° (left CH).

C3: Slightly higher in right CH (2.68° ± 1.74°) than left CH (1.91° ± 1.66°), without statistical significance.

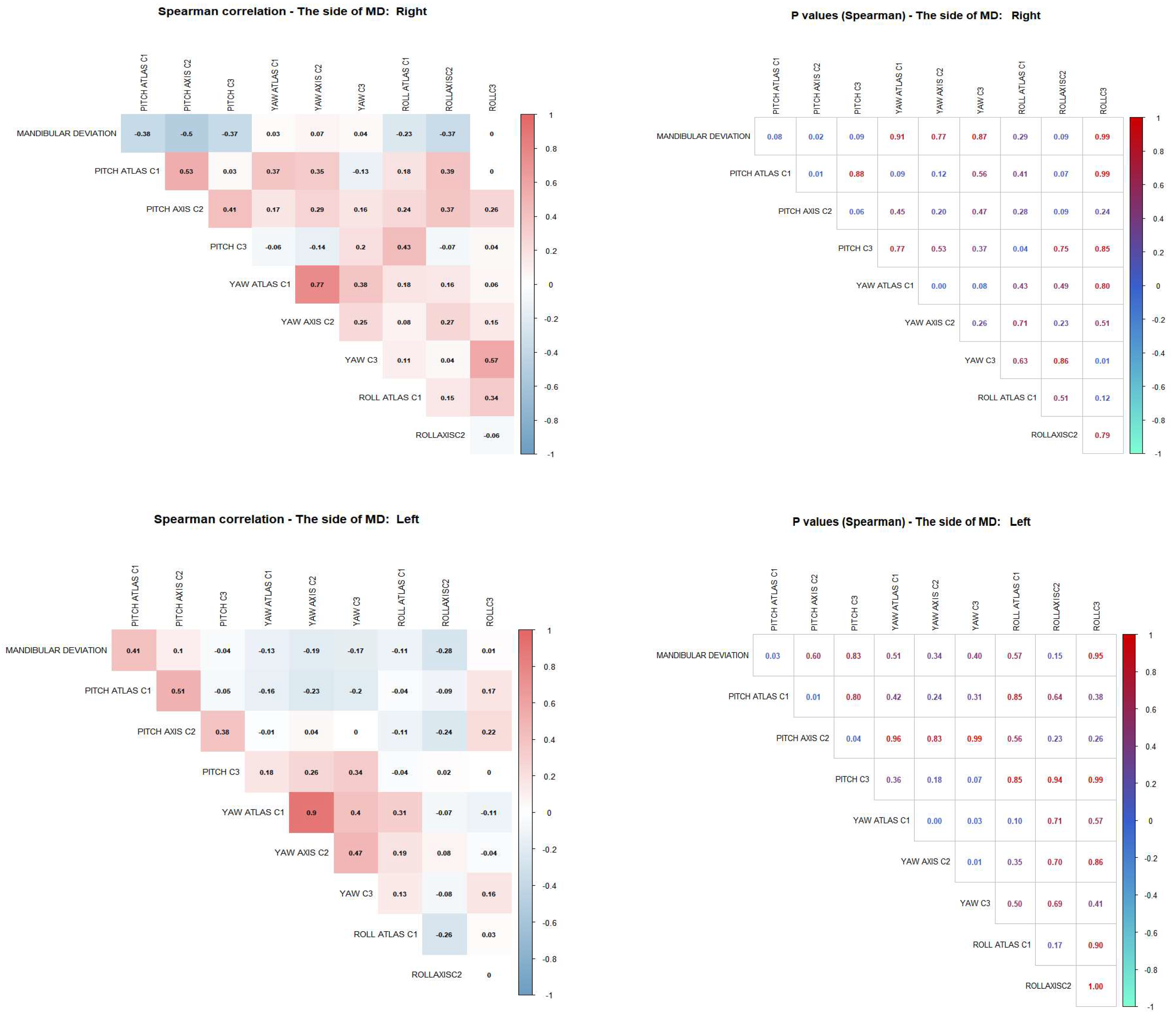

A Spearman correlation analysis investigated the relationship between MD magnitude (mm) and the 3D motion angles (Pitch, Yaw, and Roll) of cervical vertebrae C1, C2, and C3. Results were analyzed independently for each side of MD. (

Figure 3)

For patients with rightward MD, there was a significant negative correlation between MD and C2 Pitch (r=−0.50; p=0.02). A non-significant negative correlation was also noted with C1 Pitch (r=−0.38; p=0.08). These findings suggest that greater leftward MD correlates with lower pitch angles in both C1 and C2.

In patients with leftward MD, a significant positive correlation was observed between MD magnitude and C1 Pitch angle (r=0.41; p=0.03). Conversely, a significant negative correlation was found with C2 Pitch (r=−0.51; p=0.01). This indicates that greater rightward MD is associated with increased C1 pitch and decreased C2 pitch.

Relevant Intravertebral Correlations (

Figure 3)

Analysis of correlations between movement planes within each vertebra revealed strong and statistically significant associations, especially in the Atlas (C1).

In both right and left MD patient groups, we observed a strong positive correlation between the Pitch and Yaw angles of C1 (r = 0.77, p < 0.001 in the right group; r = 0.90, p < 0.001 in the left group). This indicates a high degree of synchrony between vertical and rotational movements at this level.

Similarly, in patients with left MD, a significant positive correlation was found between the Pitch and Yaw angles of the Axis (C2) (r = 0.47, p = 0.01), suggesting that, as in C1, the Axis may also exhibit coordinated movement as part of a superior cervical adaptive pattern in response to MD (

Figure 3). Additionally, in the group with right deviation, a significant correlation was identified between Yaw and Roll in the C3 vertebra (r = 0.57, p = 0.01). (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

A This study utilized computed tomography to analyze craniofacial structure and MD in patients with CH. Through tomographic segmentation, we individualized the cervical vertebrae to assess their three-dimensional behavior relative to the hyperplasia. Our results indicate changes in vertebral inclinations, predominantly towards the contralateral side of the hyperplasia—the side of mandibular deviation. These findings provide a comprehensive understanding of how craniofacial alterations can manifest in extracranial structures, such as the cervical vertebrae, potentially as adaptive responses or due to altered mechanical loads.

Our research sample consisted of patients diagnosed with

unilateral CH. This condition involves disproportionate growth of one condyle compared to the other, leading to not only FA but also significant articular and occlusal changes that affect the entire maxillomandibular system.[

6] While unilateral CH presents in three forms, this study focused exclusively on

HE and

HF. These are the most common CH entities and share a horizontal component in their alteration, effectively displacing the mandible away from the sagittal midplane. We included only severe cases, defined as those with MD of

6mm or more. This threshold signifies deviations that typically exceed personal acceptance and social perception, as reported by Wang

et al.[

7], and commonly necessitate orthodontic or surgical correction.

In our sample, 58% of severe unilateral CH cases occurred in women. This aligns with numerous studies and systematic reviews, including Raijmakers

et al. [

25], which suggest a higher female predisposition, potentially considering female gender a risk factor for unilateral CH. This predisposition, along with other TMJ disorders, may be linked to hormonal differences, particularly estrogen, which regulates bone growth and is evidenced in the TMJ[

26]. The study also revealed a predominance of right condyle alteration (56%), leading to left-sided MD (mandibular levognathism), an incidence also reported by Lopez

et al.[

27].

Regarding the relationship between CH, MD, and vertebral inclinations, our study demonstrated that the lateral roll inclination for both C2 and C3 vertebrae was significantly (p<0.05) more pronounced towards the side contralateral to the CH, which corresponds to the side of MD.

Similar findings were reported by Cardinal

et al.[

22], who observed lateral roll inclination of C2 and C3 on the side of MD and unilateral posterior crossbite in a 26-patient sample analyzed via CBCT. Expanding on these observations, Guan

et al. [

20] conducted a CBCT study on 30 subjects with MD, comparing them to individuals without FA to analyze 3D cervical vertebral changes. They concluded that a correlation exists between MD and vertebral deflection, which influences the 3D position of the cervical vertebrae. Despite methodological differences—Guan

et al. [

20] included asymmetric cases from 2 mm of MD, while our study focused solely on severe cases from 6 mm—the results align. Therefore, as stated by Lippold

et al. [

28], these studies collectively provide evidence of a relationship between jaw position and upper spinal body posture.

It is important to note that MD not only affects facial aesthetics and produces differential joint loading but also leads to asymmetrical occlusal changes, often resulting in crossbite on the deviating side[

3,

5]. In this regard, Matsaberidze

et al.[

19] theorized that inadequate occlusion can cause misalignment of the upper cervical vertebrae, leading to skull tilting and deviation from a symmetrical and balanced position above the shoulders. This, in turn, can sometimes result in postural collapse that affects, strains, and compresses the brainstem, thereby suggesting a relationship between occlusion and posture.

This theory aligns with various research findings. For instance, Meibodi

et al. [

29], Sonnesen et al. [

30], and Aranitasi

et al. [

31] found a significant correlation between cervical vertebrae anomalies and deviations with skeletal malocclusions, such as Class III. Furthermore, studies like Korbmacher

et al. [

32] have demonstrated an association between unilateral crossbite and cervical orthopedic disorders.

All the above imply a relationship between MD and 3D changes in the cervical vertebrae, but the question is how these changes might influence normal anatomy or craniocervical health. In this regard, Wakano

et al. [

33] postulate that horizontal deviation in jaw position alters postural stability, indicating changes in the stomatognathic system that affect dynamic balance. Similarly, Ben-Bassat

et al. [

34] observed that patients with idiopathic scoliosis exhibit more features of asymmetric malocclusion than those without. This suggests that early detection and treatment of asymmetric malocclusions should prompt evaluation for possible underlying orthopedic problems. Furthermore, Ozturk

et al. [

35] stated a significant relationship between the skeletal configuration of the cranio-cervico-mandibular system and temporomandibular disorders, with cranio-atlas axis rotations potentially contributing to the development of these conditions.

In our study, we found no statistically significant differences in vertebral anthropometric measurements between groups based on the CH side or MD side across any of the evaluated planes (Pitch, Yaw, or Roll). However, the

high dispersion of Yaw values, particularly in C1 and C2, is notable. This might reflect greater individual variability in the axial rotation of these vertebrae in patients with severe MD, possibly due to the wide range of flexion, extension, and rotational movements inherent to these cervical segments[

36].

Regarding Pitch (up-down) motion, we observed a significant decrease in the C2 angle for both sides of MD (p<0.05). This means greater MD correlates with a more pronounced downward motion at C2.

Our correlation analysis of motion planes within each vertebra revealed strong, statistically significant associations, especially in the Atlas (C1). This indicates high synchrony between C1's vertical (Pitch) and rotational (Yaw) movements, suggesting an integrated functional response of C1 to postural changes linked to MD.

Similarly, in the left CH and right MD group, a significant positive correlation between Pitch and Yaw was found in the

Axis (C2) vertebra (r=0.47, p=0.01). Like C1, C2 appears to participate coordinately in cervical adaptation to MD. This finding may reflect a functional coupling in the upper cervical spine, possibly associated with compensatory mechanisms or stabilization of the postural axis in relation to MD. This is plausible given that the craniovertebral junction—the complex transition between the brain and cervical spine involving the atlas and axis joined by the odontoid apophysis—houses vital neural and vascular structures while allowing for the greatest range of spinal movements[

17,

18].

The 3D positional deviations observed at C1, C2, and C3 in the present study may reflect a neuromuscular compensatory response to MD associated with CH. However, due to the cross-sectional design of this investigation, the absence of a non-asymmetrical control group, and the limited body of literature addressing this specific interaction, a definitive cause-and-effect relationship between MD and cervical spine positioning cannot be established.

Although existing theoretical frameworks suggest that the stomatognathic system may influence cervical alignment, its overall contribution to global postural control remains insufficiently understood. Moreover, without comparison to individuals presenting mandibular asymmetry of non-pathological origin, it remains uncertain whether the observed alterations in cervical vertebral angulation exceed normal anatomical variability or represent adaptive postural responses.

Accordingly, these findings should be interpreted as exploratory and hypothesis-generating, as it remains uncertain whether the observed changes in vertebral angulation fall within normal anatomical variability or represent postural alterations with potential clinical relevance. Future prospective and longitudinal studies, incorporating both symmetrical healthy controls and appropriately matched asymmetrical groups, are required to elucidate the temporal and causal relationships between mandibular deviation, occlusal characteristics, cervical spine alignment, and overall body posture.

Study Limitations: A key limitation of this study is the absence of a control group of patients with facial symmetry for comparison. Additionally, variables such as postural habits or pre-existing neuromuscular conditions were not measured. Therefore, while a correlation is documented, direct causality requires further evidence, which future longitudinal studies should support.

5. Conclusions

The key findings from this study are:

Vertebral Lateral Inclination: Patients with CH exhibiting a horizontal alteration vector (HE and HF) show a greater proportion of lateral Roll inclination in their C1, C2, and C3 vertebrae. This inclination is consistently directed towards the contralateral side of the hyperplasia, which is also the side of MD.

Mandibular Deviation and C2 Pitch: As the magnitude of MD increases (for both right and left deviation), the Pitch of the C2 vertebra becomes more negative. This indicates a downward, or inferior, movement of the C2 vertebra.

Synchronized Upper Cervical Movement: There's a high degree of synchrony between Pitch and Yaw movements in both the C1 and C2 vertebrae. This suggests that these vertebrae exhibit coordinated motion, likely as part of an adaptive pattern in response to MD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

preprints.org., Table S1: Mean values of the three-dimensional angles (Pitch, Yaw and Roll) of the cervical vertebrae according to the CH side.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.L and C.M.R; methodology, C.M.R and D.F.L.; software, R.C.P.; validation, C.M.R., L.E.A. and R.C.P.; formal analysis, D.F.L. and C.M.R.; investigation, C.M.R and D.F.L.; resources, L.E.A. and R.C.P.; data curation, RC.P. and L.E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.L.; writing—review and editing, D.F.L.; visualization, C.M.R. and D.F.L.; supervision, L.E.A.; project administration, D.F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees of Clínica Imbanaco (CEI-856) and Universidad del Valle Faculty of Health (E 008-024).

Informed Consent Statement

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study where tomographic images were evaluated. All patients signed the institutional informed consent form for these procedures before the scans were performed.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request due to restrictions, such as privacy or ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere acknowledge to the Imbanaco Medical Center, Research Institute staff for their support during the development of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MD |

Mandibular deviation |

| CH |

Condylar hyperplasia |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| HE |

Hemimandibular elongation |

| HF |

Hybrid form |

| TMJ |

Temporomandibular joint |

| FA |

Facial asymmetry |

| C1 |

Atlas |

| C2 |

Axis |

References

- Niño-Sandoval, TC; Maia, FPA; Vasconcelos, BCE. Efficacy of proportional versus high condylectomy in active condylar hyperplasia - A systematic review. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2019, 47, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, DF; López, C; Moreno, M; Pinedo, R. Post-Condylectomy Histopathologic Findings in Patients With a Positive (99m)Tc Methylene Diphosphonate Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomographic Diagnosis for Condylar Hyperplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018, 76, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolte, JW; Schreurs, R; Karssemakers, LHE; Tuinzing, DB; Becking, AG. Demographic features in Unilateral Condylar Hyperplasia: An overview of 309 asymmetric cases and presentation of an algorithm. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2018, 46, 1484–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, DF; Botero, JR; Muñoz, JM; Cárdenas-Perilla, R; Moreno, M. Are There Mandibular Morphological Differences in the Various Facial Asymmetry Etiologies? A Tomographic Three-Dimensional Reconstruction Study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 77, 2324–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gateno, J; Coppelson, KB; Kuang, T; Poliak, CD; Xia, JJ. A Better Understanding of Unilateral Condylar Hyperplasia of the Mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 79, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolford, LM; Movahed, R; Perez, DE. A classification system for conditions causing condylar hyperplasia. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014, 72, 567–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, TT; Wessels, L; Hussain, G; Merten, S. Discriminative Thresholds in Facial Asymmetry: A Review of the Literature. Aesthet Surg J. 2017, 37, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluccio, G; Caridi, V; Impellizzeri, A; Chudan, AP; Vernucci, R; Barbato, E. Familiar occurrence of facial asymmetry: a pilot study. Minerva Stomatol. 2020, 69, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J; Paradowski, B. Facial Asymmetry: A Narrative Review of the Most Common Neurological Causes. Symmetry 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, LE; Zammuto, S; Lopez, DF. Evaluating Surgical Approaches for Hemimandibular Hyperplasia Associated with Osteochondroma: A Systematic Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2024, 13(22). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, LE; Cicciù, M; Doetzer, A; Beck, ML; Cervino, G; Minervini, G. Mandibular condylar hyperplasia and its correlation with vascular endothelial growth factor. J Oral Rehabil. 2023, 50, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launonen, AM; Vuollo, V; Aarnivala, H; et al. A longitudinal study of facial asymmetry in a normal birth cohort up to 6 years of age and the predisposing factors. Eur J Orthod. 2023, 45, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, YW; Lo, LJ. Facial asymmetry: etiology, evaluation, and management. Chang Gung Med J. 2011, 34, 341–351. [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki, K; Suzuki, K; Mito, T; Tanaka, EM; Sato, S. Morphologic, functional, and occlusal characterization of mandibular lateral displacement malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop Off Publ Am Assoc Orthod Its Const Soc Am Board Orthod. 2010, 137, 454.e1-9; discussion 454-455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, MH; Cho, JH. The three-dimensional morphology of mandible and glenoid fossa as contributing factors to menton deviation in facial asymmetry—retrospective study. Prog Orthod. 2020, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, CCR; Silva, EPE. Unilateral tmj prosthetic rehabilitation and facial asymmetry correction after idiopathic condylar resorption: a 6 years follow up. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 48, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M; Wähling, Knut; Stiesch-Scholz, Meike; Tschernitschek, H. The Functional Relationship Between the Craniomandibular System, Cervical Spine, and the Sacroiliac Joint: A Preliminary Investigation. CRANIO® 2003, 21, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, AJ; Scheer, JK; Leibl, KE; Smith, ZA; Dlouhy, BJ; Dahdaleh, NS. Anatomy and biomechanics of the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurg Focus. 2015, 38, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsaberidze, T; Conte, M; Quatrano, V; Bibilashvili, V. Conception of Human Body Biomechanical Balance, Metacognitive Diversity, Interdisciplinary Approach. Oral Health Dent Sci. 2018, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- xin, Guan Y; fei, Tian P; Li, B; ping, Wu X. The correlation study on mandibular deviation and cervical vertebrae posture in patients with mandibular asymmetry. 2021. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:236627260.

- Nakashima, A; Yamada, T; Nakano, H; et al. Jaw asymmetry may cause bad posture of the head and the spine—A preliminary study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2018, 30, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, L; da Silva, TR; Andujar, ALF; Gribel, BF; Dominguez, GC; Janakiraman, N. Evaluation of the three-dimensional (3D) position of cervical vertebrae in individuals with unilateral posterior crossbite. Clin Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J; Sujir, N; Shenoy, N; Binnal, A; Ongole, R. Morphological Assessment of TMJ Spaces, Mandibular Condyle, and Glenoid Fossa Using Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT): A Retrospective Analysis. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2021, 31, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorov, A; Beichel, R; Kalpathy-Cramer, J; et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raijmakers, PG; Karssemakers, LHE; Tuinzing, DB. Female predominance and effect of gender on unilateral condylar hyperplasia: a review and meta-analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012, 70, e72–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zieliński, G; Pająk-Zielińska, B. Association between Estrogen Levels and Temporomandibular Disorders: An Updated Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, B DF; Corral, S CM. Comparison of planar bone scintigraphy and single photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of active condylar hyperplasia. J Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg Off Publ Eur Assoc Cranio-Maxillo-fac Surg. 2016, 44, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippold, C; Danesh, G; Hoppe, G; Drerup, B; Hackenberg, L. Sagittal spinal posture in relation to craniofacial morphology. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meibodi, SE; Parhiz, H; Motamedi, MHK; Fetrati, A; Meibodi, EM; Meshkat, A. Cervical vertebrae anomalies in patients with class III skeletal malocclusion. J Craniovertebral Junction Spine 2011, 2, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnesen, L; Kjaer, I. Cervical column morphology in patients with skeletal Class III malocclusion and mandibular overjet. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop Off Publ Am Assoc Orthod Its Const Soc Am Board Orthod. 2007, 132, 427.e7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranitasi, L; Tarazona, B; Zamora, N; Gandía, JL; Paredes, V. Influence of skeletal class in the morphology of cervical vertebrae: A study using cone beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbmacher, H; Koch, L; Eggers-Stroeder, G; Kahl-Nieke, B. Associations between orthopaedic disturbances and unilateral crossbite in children with asymmetry of the upper cervical spine. Eur J Orthod. 2007, 29, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakano, S; Takeda, T; Nakajima, K; Kurokawa, K; Ishigami, K. Effect of experimental horizontal mandibular deviation on dynamic balance. J Prosthodont Res. 2011, 55, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Bassat, Y; Yitschaky, M; Kaplan, L; Brin, I. Occlusal patterns in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop Off Publ Am Assoc Orthod Its Const Soc Am Board Orthod. 2006, 130, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, K; Danışman, H; Akkoca, F. The effect of temporomandibular joint dysfunction on the craniocervical mandibular system: A retrospective study. J Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, MD; Bruner, HJ; Maiman, DJ. Anatomic and biomechanical considerations of the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery 2010, 66, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Front view. A. Severe mandibular deviation (10.11mm) to the left in a subject with condylar hyperplasia of the hybrid form. B. C1, C2 and C3 vertebrae with Pitch, Roll and Yaw planes.

Figure 1.

Front view. A. Severe mandibular deviation (10.11mm) to the left in a subject with condylar hyperplasia of the hybrid form. B. C1, C2 and C3 vertebrae with Pitch, Roll and Yaw planes.

Figure 2.

A. Frontal view. Severe subject diagnosed with CH of the HF type, anatomical points located Cg1- 2 (Crista Galli), ENA (Anterior Nasal Spine), LMS (Mid Sagittal Line), Me (Menton), in yellow the segmented skull is illustrated, in purple the C1 vertebra, in blue the C2 vertebra, in green the C3 vertebra, all this to evaluate the magnitude of MD and the Roll and Yaw of the cervical vertebrae. B. Sagittal view. Subject with severe MD, diagnosed with CH. Anatomical points located Cg1-2 (Crista Galli), ENA (Anterior Nasal Spine), LMS (Mid Sagittal plane), Me (Menton), Or1 (Right Orbit), Or2 (Left Orbit), Po1 (Right Porion), Po2 (Left Porion), Atlas 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, Axis 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, C3 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, in yellow the segmented skull is illustrated, in purple the C1 vertebra, in blue the C2 vertebra, in green the C3 vertebra, all this to evaluate the up-down movement (pitch) of the first three cervical vertebrae.

Figure 2.

A. Frontal view. Severe subject diagnosed with CH of the HF type, anatomical points located Cg1- 2 (Crista Galli), ENA (Anterior Nasal Spine), LMS (Mid Sagittal Line), Me (Menton), in yellow the segmented skull is illustrated, in purple the C1 vertebra, in blue the C2 vertebra, in green the C3 vertebra, all this to evaluate the magnitude of MD and the Roll and Yaw of the cervical vertebrae. B. Sagittal view. Subject with severe MD, diagnosed with CH. Anatomical points located Cg1-2 (Crista Galli), ENA (Anterior Nasal Spine), LMS (Mid Sagittal plane), Me (Menton), Or1 (Right Orbit), Or2 (Left Orbit), Po1 (Right Porion), Po2 (Left Porion), Atlas 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, Axis 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, C3 1-2-3-4- MD-MI, in yellow the segmented skull is illustrated, in purple the C1 vertebra, in blue the C2 vertebra, in green the C3 vertebra, all this to evaluate the up-down movement (pitch) of the first three cervical vertebrae.

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation matrix between mandibular deviation and the three-dimensional movements of the cervical vertebrae (Pitch, Yaw, and Roll), differentiated by side of the deviation.* p-value < 0.05; statistically significant (Spearman correlation coefficient). Abbreviations: MD, mandibular deviation; r, correlation coefficient.

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation matrix between mandibular deviation and the three-dimensional movements of the cervical vertebrae (Pitch, Yaw, and Roll), differentiated by side of the deviation.* p-value < 0.05; statistically significant (Spearman correlation coefficient). Abbreviations: MD, mandibular deviation; r, correlation coefficient.

Table 1.

Description of the cephalometric landmarks used to determine the reference plane on the skull and the planes of interest in the cervical vertebrae.

Table 1.

Description of the cephalometric landmarks used to determine the reference plane on the skull and the planes of interest in the cervical vertebrae.

Table 2.

Sample distribution according to age, sex, condylar hyperplasia type, and affected side.

Table 2.

Sample distribution according to age, sex, condylar hyperplasia type, and affected side.

Table 3.

Distribution of the direction of the Roll and Yaw movements of the cervical vertebrae (C1-C3) according to the side of the CH.

Table 3.

Distribution of the direction of the Roll and Yaw movements of the cervical vertebrae (C1-C3) according to the side of the CH.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).