Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Participants

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Collection/CBCT Acquisition

2.4. Morphometric Analysis

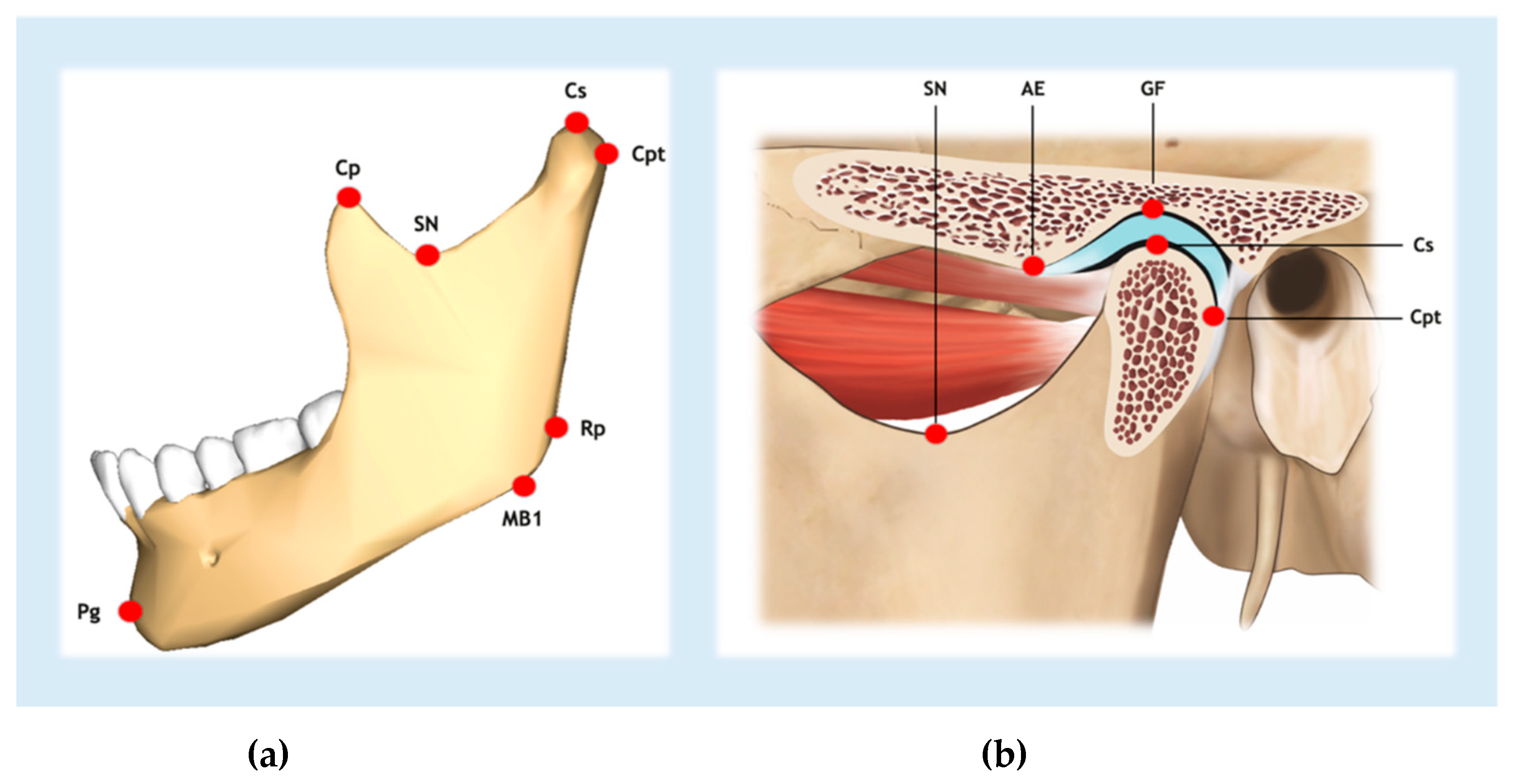

- Condylar process height: from point Cs to a horizontal line (parallel to FP) drawn at point SN. Measurement made on the right and left sides;

- Coronoid process height: From point Cp to a horizontal line (parallel to FP) drawn at point SN. Measurement taken on the right and left sides;

- Articular eminence (AE) height: From point GF to a horizontal line (parallel to FP) drawn at point AE. Measurement taken on the right and left sides;

- AE inclination: Angle formed between a line parallel to FP, drawn at point AE, with a line drawn between points AE and GF [34]. Measurement made on the right and left sides;

- Mandibular ramus height: From point Cs to MB1. Measurement made on the right and left sides;

- Mandibular body length: From point Rp to Pg. Measurement taken on the right and left sides;

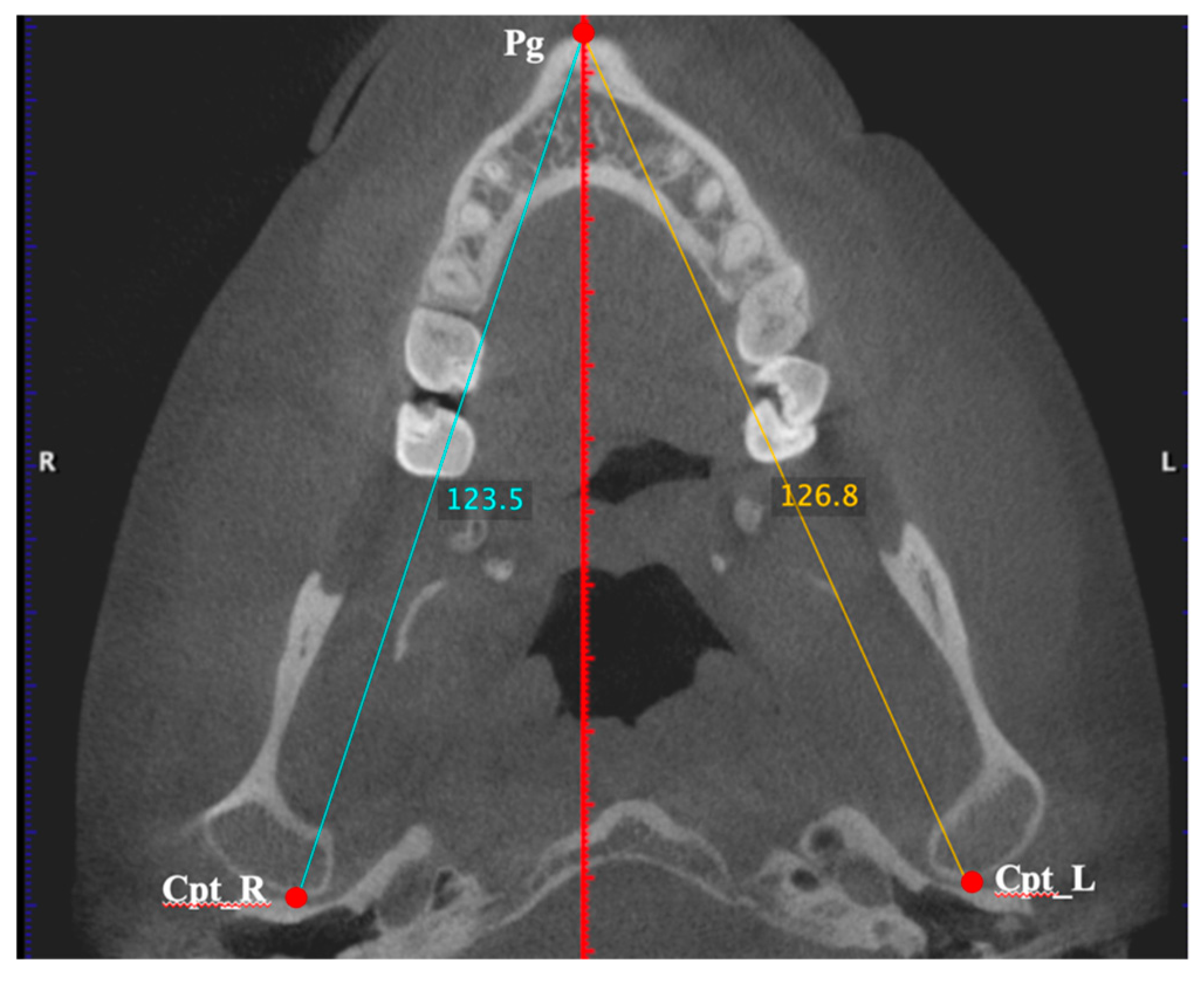

- Hemimandible length: From point Cpt to point Pg. Measurement taken on the right and left sides (Figure 3);

- Right hemimaxilla width: From point P16 to MSP. The measurement is made only on the right side by drawing a horizontal line (parallel to the FP) between the two references;

- Left hemimaxilla width: From point P26 to MSP. The measurement is made only on the left side by drawing a horizontal line (parallel to the FP) between the two references;

- Distance Cl-MSP: From point Cl to MSP. The measurement is made by drawing a horizontal line (parallel to the FP) between the two references and must be taken on the right and left sides.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, M.; Agrawal, J.; Nanjannawar, L.; Fulari, S.; Kagi, V. Dentofacial Asymmetries: Challenging Diagnosis and Treatment Planning. J Int Oral Health. 2015, 7, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silinevica, S.; Lokmane, K.; Vuollo, V.; Jakobsone, G.; Pirttiniemi, P. The association between dental and facial symmetry in adolescents. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2023, 164, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglu, M.; Bayindir, F. Effect of variations in facial flow curves on the perceptions of smile esthetics by laypeople. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2023, 129, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagl, B.; Schmid-Schwap, M.; Piehslinger, E.; Kundi, K.; Stavness, I. A Dynamic Jaw Model With a Finite-Element Temporomandibular Joint. Front Physiol 2019, 13, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms, Tenth edition. [No authors listed]. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 2023, 130, e7–e126. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, G. Centric relation: A needed reference position. Journal of prosthodontics 2023, 32, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Sharma, N.; Patni, P.; Jain, D. Association of midline discrepancy with tempromandibular joint disorder. A systematic review. Clujul Med 2018, 91, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, D.; Maci, M.; Guida, L.; Cazzolla, A.P.; Muzio, E.L.; Tepedino, M. Correction of Midline Deviation and Unilateral Crossbite Treated with Fixed Appliance. Case Rep Dent 2023, 2023, 5620345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hujoel, P.; Masterson, E.; Bollen, A.-M. Lower face asymmetry as a marker for developmental instability. Am J Hum Biol 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, S.; Mei, L.; Wen, J.; Marra, J.; Lei, L.; Li, H. Facial asymmetry of the hard and soft tissues in skeletal Class I, II, and III patients. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Chun, Y.; Bae, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, H. Comparison of ultrasonography-based masticatory muscle thickness between temporomandibular disorders bruxers and temporomandibular disorders non-bruxers. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Mora, U.; López-Cedrún, J.; Suárez-Quintanilla, J.; Varela-Centelles, P.; Mora, M.; Silva, J.; Figueiredo-Costa, F.; Santana-Penín, U. Asymmetry of dental or joint anatomy or impaired chewing function contribute to chronic temporomandibular joint disorders. Annals of Anatomy 2021, 238, 151793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heikkinen, E.; Vuollo, V.; Harila, V.; Sidlauskas, A.; Heikkinen, T. Facial asymmetry and chewing sides in twins. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2022, 80, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, H. Efficient surgical management of mandibular asymmetry. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011, 69, 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y. Surgical-orthodontic treatment for class II asymmetry: outcome and influencing factors. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enlow, D.; Hans, M. Essentials of facial growth; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wen-Ching Ko, E.; Huang, C.; Lin, C.; Chen, Y. Orthodontic Perspective for Face Asymmetry Correction. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, E.; Elluru, S. Cone beam computed tomography: basics and applications in dentistry. J Istanb Univ Fac Dent 2017, 51, S102–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, N.; Ekestubbe, A.; Frisk, F.; Lund, H. Is cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) an alternative to plain radiography in assessments of dental disease? A study of method agreement in a medically compromised patient population. Clinical Oral Investigations 2024, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Mora, U.; López-Cedrún, J.; Mora, M.; Otero, X.; Santana-Penín, U. Temporomandibular Disorders: The Habitual Chewing Side Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, D.; Zhai, X.; Li, H.; Hu, M.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H. Occlusal analysis of patients with chewing side preference and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2022, 40, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H. Research progress in effect of chewing-side preference on temporomandibular joint and its relationship with temporo-mandibular disorders. Journal of Zhejiang University (Medical Sciences) 2023, 52, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritara, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Lou, Y.; Qi, J.; Aida, J.; Ono, T. Association between the Temporomandibular Joint Morphology and Chewing Pattern. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023, 13, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenschurz-Schmidt, D.; Cherkin, D.; Rice, A.; Dworkin, R.; Turk, D.; McDermott, M.; Bair, M.; DeBar, L.; Edwards, R.; Farrar, J.; et al. Research objectives and general considerations for pragmatic clinical trials of pain treatments: IMMPACT statement. Pain 2023, 164, 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, D.; McGrath, P.; Rafii, A.; Buckingham, B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983, 17, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun Oo, L.; Miyamoto, J.; Takada, J.; Cheng, S.; Yoshizawa, H.; Moriyama, K. Three-dimensional characteristics of temporomandibular joint morphology and condylar movement in patients with mandibular asymmetry. Prog Orthod 2022, 23, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusnoto, B.; Kaur, P.; Salem, A.; Zhang, Z.; Galang-Boquiren, M.; Viana, G.; Evans, C.; Manasse, R.; Monahan, R.; BeGole, E.; et al. Implementation of ultra-low-dose CBCT for routine 2D orthodontic diagnostic radiographs: cephalometric landmark identification and image quality assessment. Semin Orthod 2015, 21, 233e247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E.; Orhan, M.; Bahsi, I.; Yalcin, E. Morphometric evaluation of the temporomandibular joint on cone-beam computed tomography. Surg Radiol Anat 2021, 43, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macri, M.; Festa, F. Three-dimensional evaluation using CBCT of the mandibular asymmetry and the compensation mechanism in a growing patient: A case report. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 921413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlicher, W.; Nielsen, I.; Huang, J.; Maki, K.; Hatcher, D.; Miller, A. Consistency and precision of landmark identification in three-dimensional cone beam computed tomography scans. Eur J Orthod 2012, 34, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Xu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Qi, K. Comparative cone-beam computed tomography evaluation of temporomandibular joint position and morphology in female patients with skeletal class II malocclusion. J Int Med Res 2020, 48, 300060519892388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, J.; Park, J.; Tai, K.; Mizutani, K.; Uzuka, S.; Miyashita, W.; Seo, H. Evaluation of condyle-fossa relationships in adolescents with various skeletal patterns using cone-beam computed tomography. Angle Orthod 2020, 90, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsavrias, E. Changes in articular eminence inclination during the craniofacial growth period. Angle Orthod 2002, 72, 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- Corp. , I. IBM SPSS Statistics for macOS, 29.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R.; Rinchuse, D.; Zullo, T. Perceptions of midline deviations among different facial types. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2014, 145, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanze, K.; Riemekasten, S.; Hirsch, C.; Koehne, T. Perception of facial and dental asymmetries and their impact on oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. J Orofac Orthop 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardash, H.; Ormanier, Z.; Laufer, B.-Z. Observable deviation of the facial and anterior tooth midlines. J Prosthet Dent 2003, 89, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyagali, T.; Chandralekha, B.; Bhayya, D.; Kumar, S.; Balasubramanyam, G. Are ratings of dentofacial attractiveness influenced by dentofacial midline discrepancies? Aust Orthod J 2008, 24, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, I.; Xiao, L.; Li, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, Z. Young people’s esthetic perception of dental midline deviation. Angle Orthod 2010, 80, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, S.; Naidoo, S.; Govier, D.; Martin, R.; Kane, A.; Marazita, M. Anthropometric precision and accuracy of digital three-dimensional photogrammetry: Comparing the Genex and 3 dMD imaging systems with one another and with direct anthropometry. J Craniofacc Surg 2010, 21, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübbers, H.; Medinger, L.; Kruse, A.; Grätz, K.; Matthews, F. Precision and accuracy of the 3dMD photogrammetric system in craniomaxillofacial application. J Craniofac Surg 2010, 21, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, E.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y. Characteristics and corrective outcome of face asymmetry by orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 67, 2201–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Reference point | Definition |

| AE | Articular eminence | Most inferior point of the apex of the articular eminence |

| Cl | Condyle-lateral | Most lateral point of the mandibular condyle |

| Cp | Coronoid | Most superior point of the coronoid process |

| Cpt | Condyle-posterior | Most posterior point of the mandibular condyle |

| Cs | Condyle-superior | Most superior point of the mandibular condyle |

| GF | Glenoid fossa | Most superior point of the glenoid fossa |

| MB1 | Mandibular ramus | Most inferior point of the inferior border of the mandibular ramus |

| Pg | Pogonion | Most anterior point of the outline of the mandibular symphysis |

| P16 | Tooth 16 | Most posterolateral point of the crown of tooth 16 |

| P26 | Tooth 26 | Most posterolateral point of the crown of tooth 26 |

| Rp | Mandibular angle | Most prominent posterosuperior point of the angle of the mandible at the mandibular ramus |

| SN | Sigmoid notch | Most inferior point of the sigmoid notch |

| Characteristic | Participants | ||

| Female sex – no. (%) | 35 (92.1) | ||

| Median age (IQR) – years | 29.5 (25 – 42) | ||

| Affected side/s – no. (%) | |||

| Right | 7 (18.4) | ||

| Left | 19 (50) | ||

| Both | 12 (31.6) | ||

| Arthralgia (with or without myalgia) – no. (%) | 32 (84.2) | ||

| Myalgia (without arthralgia) – no. (%) | 6 (15.8) | ||

| Jaw-pain score (VAS) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (6 – 7.6) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.7 (1.2) | ||

| Habitual chewing side – no. (%) | |||

| Right | 12 (31.6) | ||

| Left | 18 (47.4) | ||

| Alternate | 8 (21.1) | ||

| Side toward midline shift was deviated – no. (%) | |||

| Right | 16 (42.1) | ||

| Left | 13 (34.2) | ||

| Both | 8 (21.1) | ||

| Cannot be assessed | 1 (2.6) | ||

| Condylar path angles in relation to Frankfort Horizontal Plane | |||

| Right side. Mean (SD) (degrees) | 50.5 (10.7) | ||

| Left side. Mean (SD) (degrees) | 50.1 (10.5) | ||

|

Variable Mean (SD) |

Side |

Paired differences (95% CI) |

P-value * | Effect size | |

| Right | Left | ||||

| Hemimandible length (mm) | 119.4 (5.7) | 118.6 (5.3) | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.5) | 0.01 | 0.4 |

| Mandibular body length (mm) | 92.2 (5.2) | 92.9 (5.1) | -0.7 (-1.4 to 0.1) | 0.08 | -0.3 |

| Mandibular ramus height (mm) | 65.6 (5.4) | 64.5 (4.3) | 1.1 (0.1 to 2.2) | 0.03 | 0.4 |

| Coronoid process height (mm) | 11.7 (3.2) | 11.6 (3.4) | 0.1 (-0.3 to 0.5) | 0.51 | 0.1 |

| Condylar process height (mm) | 16.0 (2.3) | 15.4 (2.1) | 0.7 (0.0 to 1.3) | 0.04 | 0.4 |

| Distance Cl-MSP (mm) | 56.5 (3.0) | 56.5 (3.2) | 0.0 (-0.8 to 0.8) | 0.97 | 0.9 |

| Hemimaxilla width (mm) | 27.0 (1.3) | 27.0 (1.6) | 0.0 (-0.5 to 0.5) | 0.99 | 0.0 |

| AE height (mm) | 7.0 (1.7) | 6.6 (1.5) | 0.5 (0.0 to 0.9) | 0.04 | 0.4 |

| AE inclination angle (degrees) | 33.5 (7.1) | 33.7 (6.5) | -0.2 (-2.0 to 1.6) | 0.80 | 0.0 |

| Condylar path angle (degrees) | 45.7 (9.9) | 48.8 (9.7) | -3.1 (-6.3 to 0.0) | 0.05 | -0.3 |

|

Variable Mean (SD) |

Side towards the jaw incisal midline deviates |

Paired differences (95% CI) |

P-value | Effect size | |

| Ipsilateral | Contralateral | ||||

| Hemimandible length (mm) | 118.8 (5.1) | 118.8 (5.4) | -0.2 (-1.1 to 0.6) | 0.60 | -0.1 |

| Mandibular body length (mm) | 92.1 (4.4) | 92.5 (4.7) | -0.4 (-1.4 to 0.6) | 0.41 | -0.1 |

| Mandibular ramus height (mm) | 65.4 (5.1) | 64.9 (5.2) | 0.5 (-0.7 to 1.6) | 0.44 | 0.1 |

| Coronoid process height (mm) | 11.7 (3.3) | 12.1 (3.7) | -0.4 (-0.9 to 0.0) | 0.05 | -0.4 |

| Condylar process height (mm) | 15.7 (1.8) | 16.1 (2.3) | -0.3 (-1.0 to 0.4) | 0.40 | -0.2 |

| Distance Cl-MSP (mm) | 56.9 (3.2) | 56.5 (3.2) | 0.4 (-0.5 to 1.3) | 0.35 | 0.2 |

| Hemimaxilla width (mm) | 27.1 (1.3) | 27.0 (1.3) | 0.0 (-0.4 to 0.5) | 0.87 | 0.03 |

| AE height (mm) | 7.0 (1.8) | 6.8 (1.5) | 0.2 (-0.4 to 0.8) | 0.47 | 0.1 |

| AE inclination angle (degrees) | 34.3 (7.1) | 33.7 (7.0) | 0.6 (1.5 to 2.7) | 0.56 | 0.1 |

| Condylar path angle (degrees) | 47.5 (10.8) | 48.9 (9.1) | 0.6 (-1.5 to 2.7) | 0.57 | 0.1 |

|

Variable Mean (SD) |

Chronic TMD (unilateral symptoms) |

Paired differences (95% CI) |

P-value | Effect size | |

| Affected side | Unaffected side | ||||

| Hemimandible length (mm) | 119.8 (5.6) | 120.1 (6.3) | -0.3 (-1.2 to 0.6) | 0.54 | -0.1 |

| Mandibular body length (mm) | 93.3 (5.9) | 93.2 (5.9) | 0.0 (-1.0 to 0.6) | 0.87 | -0.1 |

| Mandibular ramus height (mm) | 65.2 (4.4) | 66.5 (5.7) | -1.3 (-2.6 to 0.05) | 0.06 | -0.4 |

| Coronoid process height (mm) | 11.8 (3.9) | 11.6 (3.7) | 0.3 (-0.2 to 0.7) | 0.25 | 0.2 |

| Condylar process height (mm) | 15.7 (2.2) | 16.2 (2.7) | -0.5 (-1.3 to 0.4) | 0.31 | -0.2 |

| Distance Cl-MSP (mm) | 57.3 (3.2) | 56.8 (1.7) | 0.5 (-0.5 to 1.5) | 0.35 | 0.2 |

| Hemimaxilla width (mm) | 27.1 (1.7) | 27.1 (1.7) | 0.0 (-0.6 to 0.5) | 0.92 | 1.4 |

| AE height (mm) | 6.5 (1.6) | 7.1 (1.9) | -0.5 (-1.2 to 0.1) | 0.09 | 0.4 |

| AE inclination angle (degrees) | 32.6 (7.7) | 33.3 (7.1) | -0.7 (-1.9 to 0.5) | 0.25 | -0.2 |

| Condylar path angle (degrees) | 48.9 (9.5) | 45.2 (11.0) | 3.7 (0.3 to 7.2) | 0.04 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).