Submitted:

18 September 2024

Posted:

19 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure Methodology

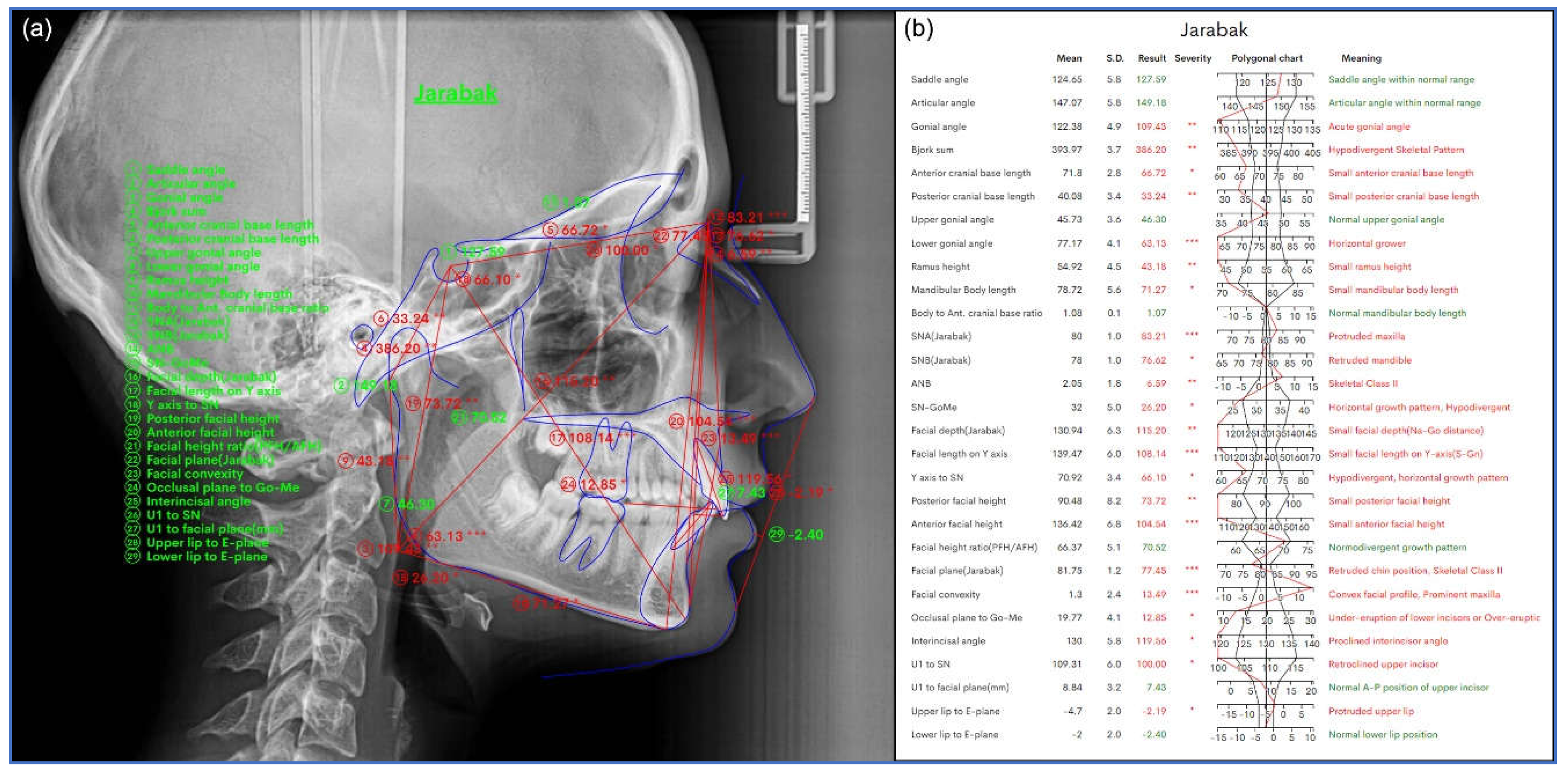

| S. No | Measurement | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total Anterior Facial Height | Measured along the N–Me line. |

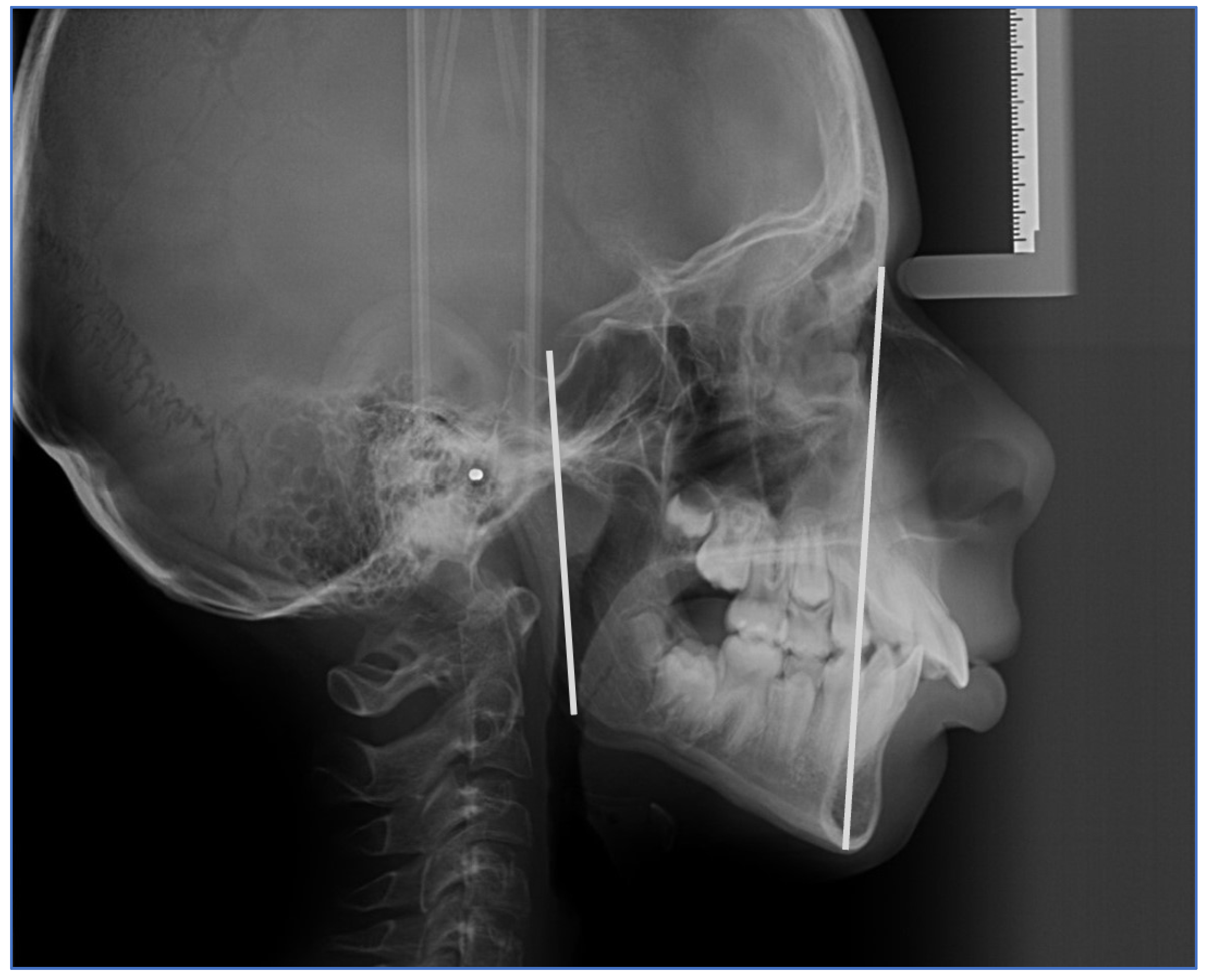

| 2 | Total Posterior Facial Height | Measured along the S–Go line. |

| 3 | FHR | Calculated as the ratio of TPFH to TAFH multiplied by 100, also known as the Jarabak’s ratio. Facial morphology classified into three patterns based on FHR: 1) Hyperdivergent growth pattern: FHR < 59%, predominantly vertical growth pattern. 2) Neutral or normodivergent growth pattern: FHR between 59 and 63%. 3) Hypodivergent growth pattern: FHR > 63%, predominantly horizontal growth pattern [15]. Nahidh et al. reported that the vertical relation is better measured using the sum of posterior angles and the Jarabak ratio [16]. |

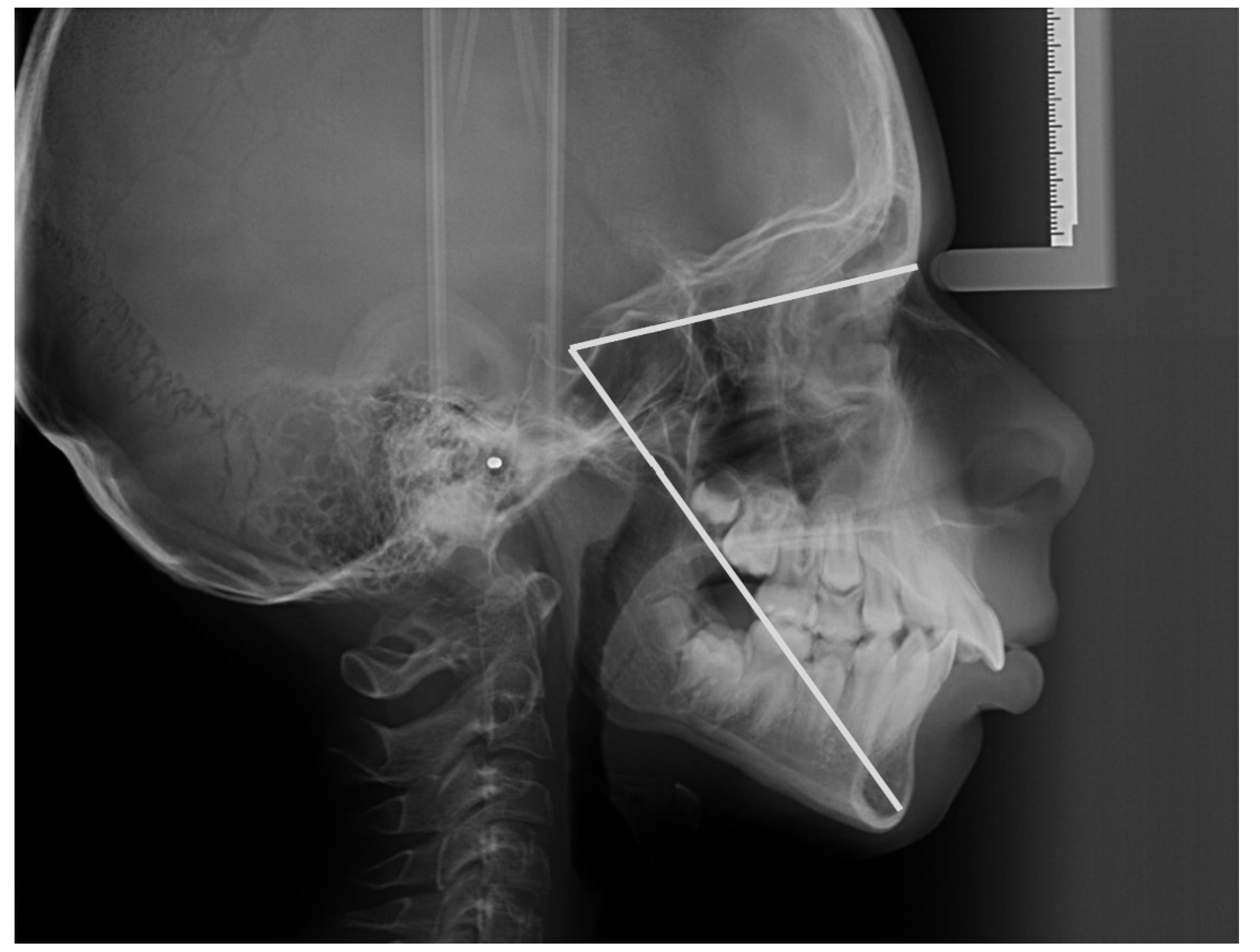

| 4 | S–Gn (Y-Axis) Angle | Defines the location of the mandible in relation to the cranial base. A mean value of 66° indicates a posterior mandibular position and dominance of vertical growth; smaller angles indicate an anterior mandibular position and dominance of anterior growth [17]. |

| 5 | Y SN Angle | Formed by the SN plane and the Y axis, reflects the downward and forward posture of the chin relative to the upper face [18,19,20,21]. |

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristic of Included Sample

3.2. Molar Class Distribution

3.3. Predictors of Gender Differentiation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amatya, S.; Shrestha, R.M.; Napit, S. Growth pattern in skeletal Class I malocclusion: A Cephalometric Study. Orthod. J. Nepal 2021, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, R.S.; Raghunath, N.; Sahoo, K.C.; Shivlinga, B.M. Comparative study of mandibular morphology in patients with hypodivergent and hyperdivergent growth patterns: A cephalometric study. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2013, 47 (Suppl. 3), 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisht, L.; Negi, S.; Aggarwal, M.; Sandhu, G.P.S.; Kaushal, B. TO check the reliability of various cephalometric parameters used for predicting the types of malocclusion and growth pattern. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2016, 4, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Dutta, K.; Gosain, N.; Yadav, A.K.; Yadav, N.; Singh, K.K. Vertical Proportion of the Face: A Cephalometric study. Orthod. J. Nepal 2021, 11, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaija, E.S.A.; Richardson, A. Growth prediction in Class III patients using cluster and discriminant function analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2003, 25, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wins, S.M.; Antonarakis, G.S.; Kiliaridis, S. Predictive factors of sagittal stability after treatment of Class II malocclusions. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, C.V.; Mattos, C.T.; Maia, J.C.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Reis, M.F.; Mucha, J.N.; Vilella, B.; Ruellas, A.C.; Luiz, R.R.; Costa, M.C.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms underlying the skeletal Class III phenotype. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auconi, P.; Scazzocchio, M.; Defraia, E.; McNamara, J.A.; Franchi, L. Forecasting craniofacial growth in individuals with class III malocclusion by computational modelling. Eur. J. Orthod. 2014, 36, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Silva, A.; Carnevali-Arellano, R.; Vivanco-Coke, S.; Tobar-Reyes, J.; Araya-Díaz, P.; Palomino-Montenegro, H. Craniofacial growth predictors for class II and III malocclusions: A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2021, 7, 242–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, U.U.H.; Sidhu, M.S.; Prabhakar, M. A Cephalometric evaluation of dentoskeletal variables and ratios in three different facial types. J. Adv. Med. Dent. Sci. Res. 2021, 9, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Padarthi, S.C.; Vijayalakshmi, D.; Apparao, H. Evaluation of Facial Height Ratios and Growth Patterns in Different Malocclusions in a Population of Dravidian Origin–A Cephalometric study. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2019, 18, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Proffit, W.R.; Fields, H.; Msd, D.M.; Larson, B.; Sarver, D.M. Contemporary Orthodontics, 6e: South Asia Edition-E-Book; Elsevier India: Gurugram, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nadim, K.A.R.; Rizwan, S. Prevalence of angles malocclusion according to age groups and gender. Pak. Oral Dent. J. 2014, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, B.; Tallgren, A. Head posture and craniofacial morphology. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1976, 44, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwat, P.P.; Jarabak, J.R. Malocclusion and facial morphology is there a relationship? An epidemiologic study. Angle Orthod. 1985, 55, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Mahmoud, A.B.; Al-Shaham, S.A. The relation among different methods for assessing the vertical jaws relation. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2016, 15, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rakosi, T.; An Atlas and Manual of Cephalometric Radiology, U.K., London:Wolfe Medical, 1982.

- Valiathan, M.; Valiathan, A.; Ravinder, V. Jarabak cephalometric analysis reborn. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2001, 35, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, V.S.; Nucci, L.; Farahmand, M.; Aghdam, H.M.; Fateh, A.; Jamilian, A.; d’Apuzzo, F. Hard and Soft Tissue Changes in Patients with Borderline Class III Malocclusion after Maxillary Advancement or Mandibular Setback Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Study. Science Repository. 2020.

- Mucedero, M.; Coviello, A.; Baccetti, T.; Franchi, L.; Cozza, P. Stability factors after double-jaw surgery in Class III malocclusion: A systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeltins, A.; Jakobsone, G.; Urtane, I.; Bigestans, A. The stability of bilateral sagittal ramus osteotomy and vertical ramus osteotomy after bimaxillary correction of class III malocclusion. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 39, 583–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangla, R.; Singh, N.; Dua, V.; Padmanabhan, P.; Khanna, M. Evaluation of mandibular morphology in different facial types. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2011, 2, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.P.; Pinzan, A.; Janson, G.; Fernandes, T.M.F.; Sathler, R.C.; Henriques, R.P. Facial height in Japanese-Brazilian descendants with normal occlusion. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2014, 19, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jabaa, A.H.; Aldrees, A.M. ANB, Wits and Molar Relationship, Do they correlate in Orthodontic Patients? Dentistry 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, A.; Kumar, V.; Thakur, S.; Rai, S.; Bharti, P. Facial Morphology and Malocclusion Is there any Relation? A Cephalometric Analysis in Hazaribag Population. J. Contemp. Orthod. 2018, 2, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Roi, A.; Roi, C. I.; Andreescu, N. I.; Riviş, M.; Badea, I. D.; Meszaros, N.; Rusu, L.C.; Iurciuc, S. Oral cancer histopathological subtypes in association with risk factors: A 5-year retrospective study. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, 2020, 61, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maskey, S.; Shrestha, R. Cephalometric approach to vertical facial height. Orthod. J. Nepal 2019, 9, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taner, L.; Gürsoy, G.M.; Uzuner, F.D. Does Gender Have an Effect on Craniofacial Measurements? Turk. J. Orthod. 2019, 32, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.F.; Otsuka, T.; Akimoto, S.; Sato, S. Vertical facial height and its correlation with facial width and depth: Three dimensional cone beam computed tomography evaluation based on dry skulls. Int. J. Stomatol. Occlusion Med. 2013, 6, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdaway, RA. A Soft Tissue Cephalometric Analysis and Its Use In Orthodontic Treatment Planning Part II. Am. J. Orthod. 1984, 84, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, W.J.S.; Hirst, D. Craniofacial characteristics of subjects with normal and postnormal occlusions—A longitudinal study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1987, 92, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björk, A. The nature of facial prognathism and its relation to normal occlusion of the teeth. Am. J. Orthod. 1951, 37, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schudy, F.F. Vertical growth versus anteroposterior growth as related to function and treatment. Angle Orthod. 1964, 34, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, L.E. A simplified approach to prediction. Am. J. Orthod. 1975, 67, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opdebeeck, H.; Bell, W.H. The short face syndrome. Am. J. Orthod. 1978, 73, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisconi, M.F.; Henriques, J.F.C.; Janson, G.; Freitas, K.M.S.D.; Santos, P.B.D.D. Stability of Class II treatment with the Bionator followed by fixed appliances. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2013, 21, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, J.A.M.; Cunha, D.L.; Calheiros, A.D.A.; Koo, D. Rationale for referring class II patients for early orthodontic treatment. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2005, 13, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michele, C.; Federica, A.; Alessandro, S. (2015). Two-dimensional and three-dimensional cephalometry using cone beam computed tomography scans. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2015, 26, e311–e315. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | N = 94 |

|---|---|

| Age | 21 (14, 28) |

| TPFH | 76 (70, 81) |

| TAFH | 112 (104, 120) |

| Jarabak’s ratio | 67.0 (64.0, 72.0) |

| Molar Class | |

| 1 | 35 (37%) |

| 2 | 46 (49%) |

| 3 | 13 (14%) |

| Y axis to SN | 65.0 (62.0, 69.0) |

| Gender | |

| M | 35 (37%) |

| F | 59 (63%) |

| 1 Median (IQR); n (%) |

| Male (N=35) | Female (N=59) | Total (N=94) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I | 13.0 (38.2%) | 21.0 (35.6%) | 34.0 (36.6%) | 0.2231 |

| Group II | 19.0 (55.9%) | 27.0 (45.8%) | 46.0 (49.5%) | |

| Group III | 2.0 (5.9%) | 11.0 (18.6%) | 13.0 (14.0%) |

| N | I | II | III | Test Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=35) | (N=46) | (N=13) | |||

| Y axis to SN | 94 | 61.2 65.0 69.0 | 62.0 65.0 69.0 | 59.7 67.0 69.0 | F2,91=0.00, P=1.001 |

| TPFH | 94 | 71.2 77.0 81.0 | 69.0 75.0 81.1 | 70.7 76.0 78.3 | F2,91=0.30, P=0.741 |

| TAFH | 94 | 104.0 112.0 122.8 | 104.0 112.0 119.1 | 107.0 113.0 116.3 | F2,91=0.26, P=0.771 |

| Hyperdivergent (N=6) | Normodivergent (N=13) | Hypodivergent (N=75) | Total (N=94) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar Class | 0.4281 | ||||

| I | 2.0 (33.3%) | 8.0 (61.5%) | 25.0 (33.3%) | 35.0 (37.2%) | |

| II | 3.0 (50.0%) | 4.0 (30.8%) | 39.0 (52.0%) | 46.0 (48.9%) | |

| III | 1.0 (16.7%) | 1.0 (7.7%) | 11.0 (14.7%) | 13.0 (13.8%) | |

| Gender | 0.4661 | ||||

| F | 5.0 (83.3%) | 7.0 (53.8%) | 47.0 (62.7%) | 59.0 (62.8%) | |

| M | 1.0 (16.7%) | 6.0 (46.2%) | 28.0 (37.3%) | 35.0 (37.2%) |

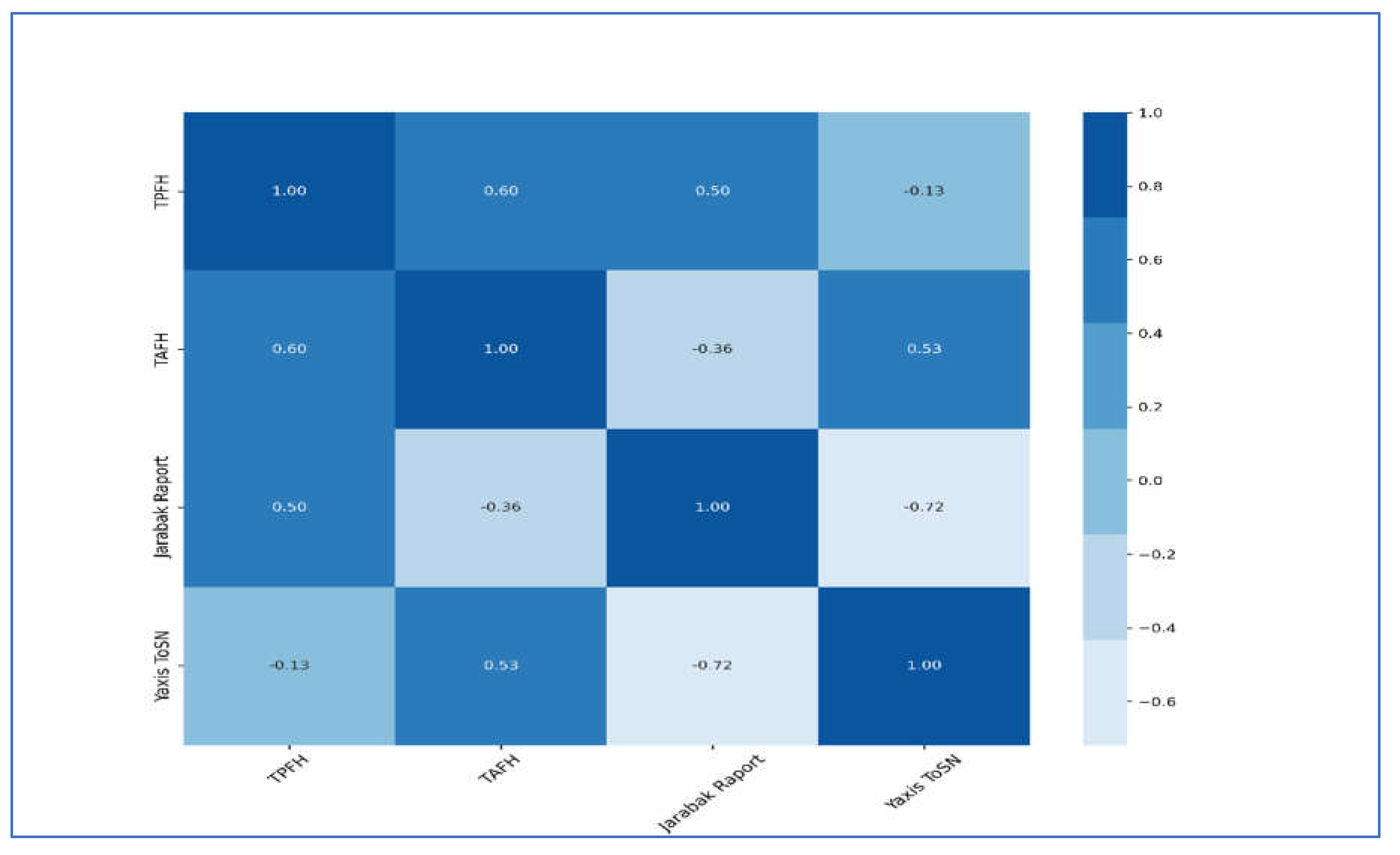

| Model Coefficients—Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% Confidence Interval | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | Z | p | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | -1.30310 | 4.5273 | -0.288 | 0.773 | 0.272 | 3.81e-5 | 1939.431 | |||||||||||||||

| TPFH | -0.00882 | 0.0510 | -0.173 | 0.863 | 0.991 | 0.897 | 1.095 | |||||||||||||||

| TAFH | 0.10096 | 0.0441 | 2.291 | 0.022 | 1.106 | 1.015 | 1.206 | |||||||||||||||

| Y axis to SN | -0.15276 | 0.0748 | -2.043 | 0.041 | 0.858 | 0.741 | 0.994 | |||||||||||||||

| Model Coefficients—Divergent | 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divergent | Predictor | Estimate | SE | Z | p | Odds ratio | Lower | Upper |

|

Hyperdivergent—Normodivergent |

Intercept | 24.8994 | 12.1376 | -2.051 | 0.040 | 1.54e-11 | 7.16e-22 | 0.330 |

| Age | -0.0564 | 0.1059 | -0.532 | 0.594 | 0.945 | 0.768 | 1.163 | |

| Yaxis_to_SN | 0.3547 | 0.1732 | 2.047 | 0.041 | 1.426 | 1.015 | 2.002 | |

|

Hypodivergent—Normodivergent |

Intercept | 21.0955 | 7.1048 | 2.969 | 0.003 | 1.45e0+9 | 1300.356 | 1.62e+15 |

| Age | 0.0475 | 0.0468 | 1.015 | 0.310 | 1.049 | 0.957 | 1.149 | |

| Yaxis to_SN | -0.3050 | 0.1052 | -2.900 | 0.004 | 0.737 | 0.600 | 0.906 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).