1. Introduction

The influence of facial aesthetics permeates various aspects of human life, transcending superficial interactions to impact fundamental social, psychological, and even economic outcomes [

1]. In the professional domain, facial appearance can affect hiring decisions, promotion prospects, and perceptions of leadership ability. In social contexts, facial attractiveness has been linked to social acceptance and popularity, affecting friendships, romantic relationships, and general social networking opportunities [

2]. Psychologically, the perception of one's own facial aesthetics can profoundly impact self-esteem, confidence, and mental health [

3]. Concerning the economic implications of facial aesthetics, more attractive individuals may earn higher wages than their less attractive counterparts and are more persuasive in marketing and advertising, influencing consumer preferences and decisions, particularly for appearance-relevant products [

4]. Lastly, the significance of facial aesthetics in human life also has ethical and cultural dimensions. Ethical debates arise in the context of cosmetic surgery and the societal pressures to conform to certain aesthetic standards. Cultural differences in what is considered attractive emphasize the diversity of human societies and the subjective nature of beauty [

5]. Thus, the impact of facial aesthetics on human life is multifaceted, influencing individual and societal behaviors, perceptions, and outcomes across a broad spectrum of contexts [

1,

6].

A convex facial profile, often accompanied by an Angle Class II malocclusion, is a common skeletal configuration in the population that is often considered less attractive in terms of facial appearance [

7,

8]. Consequently, patients often seek treatment for this condition, which involves orthodontic interventions, more invasive orthognathic surgery approaches, or a combination of both [

9,

10]. The improvement of facial appearance is a key factor for seeking treatment as well as for patient satisfaction from the provided treatment [

11,

12].

The ability of orthodontic interventions alone to considerably enhance facial appearance has been questioned even for growing patients, and this, according to objective measurements [

13,

14], as well as to facial perception studies [

15,

16]. Patients with convex profiles, after their growth has ceased, primarily have two treatment alternatives. The first option is orthodontic treatment, which is confined to specific modifications within the dentoalveolar structure and is frequently referred to as camouflage orthodontic treatment. The second option involves orthognathic surgery, a more invasive intervention that also seeks to enhance facial aesthetics—a key consideration for many patients. However, the tangible benefits derived from each type of intervention are not always clear-cut, fueling an ongoing debate in the scientific literature [

17,

18].

In a prior investigation that assessed treatment effects on facial profile photos, the perception of facial appearance alterations strongly favored the combined orthodontic and orthognathic approach over exclusive orthodontic treatment [

17]. Nevertheless, earlier research on convex profile adolescents who received conventional orthodontic appliances suggested that the observed profile improvements largely diminished when frontal and profile facial images were presented simultaneously to the assessors [

15,

16]. Thus, we assessed here the facial outcomes of combined orthodontic and orthognathic intervention compared to orthodontic camouflage treatment, through the simultaneous presentation of profile and frontal facial photos to different evaluator types. We hypothesized that similarly perceivable facial appearance changes would be induced in Class II Division 1 convex profile patients by either orthognathic/orthodontic treatment or only orthodontic (camouflage) treatment.

2. Materials and Methods

The methods are similar to those of a previous publication from our team where the assessors rated pairs of profile facial images [

17]. The study protocol has been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Dental School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece prior to study commencement (Date of Approval: 22.06.2018, Protocol Number: 361). All participants provided informed consent, permitting the use of their data for research purposes. In the present study, configurations of profile and frontal facial images were assessed. Apart from the latter strategy, both studies referred to the same patient sample and all other methodological aspects were applied similarly for comparability reasons. However, most methodological considerations will be repeated here to allow for proper comprehension of the study by the readers.

2.1. Sample

The sample of the present study originated from the Postgraduate Clinic of the Department of Orthodontics, Dental School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece and was identical to that of the previous publication [

17]. The selection was made among the most recently treated Class II Division 1 patients with convex facial profile, who met the inclusion criteria, with the goal of forming two groups of 18 patients (Group A and Group B) with a similar distribution of sex. The sample size was selected based on empirical evidence, considering also resource availability and study feasibility in terms of available patients and number of required raters [

15,

16,

19]. It was proved to have adequate power for the primary study outcomes [

17]. Group A included non-growing patients with a convex profile who received orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances in both jaws combined with mono- or bi-maxillary orthognathic surgery. Group B included non-growing patients with a convex profile who were treated solely with fixed orthodontic appliances. The specific plans were tailored per case, according to each patient’s needs and demands, and were not considered in sample selection. Both groups were subject to the following eligibility criteria [

17]:

- Complete initial and final diagnostic data, i.e., history (medical, dental, and orthodontic/orthognathic treatment), initial panoramic and cephalometric radiographs, initial and final dental casts, initial and final intraoral and facial photographs (profile and frontal) of acceptable diagnostic quality.

- Class II Division 1 dental anomaly at the start of treatment (bilateral molar Class II more than half cusp and overjet between 6 and 12 mm) with no considerable functional shift during maximum intercuspation (≥2 mm).

- Convex skeletal configuration at treatment start (5°<ANB<9° on the lateral cephalometric radiograph).

- Convex facial profile at treatment start in the initial facial profile photograph (males: 15°<facial contour angle<25°, females: 17°<facial contour angle<27°) [

20].

- FMA angle between 17.5° and 32.5° on the initial lateral cephalometric radiograph.

- Total treatment duration of 1 to 5 years.

- No rhinoplasty or other aesthetic surgical intervention (including Botox treatment) on the facial soft tissues.

- White European ancestry (this ancestry was largely overrepresented in the searched archives, as well as on the rater population).

- Patients without congenital craniofacial anomalies, syndromes, marked facial asymmetries and marked functional deviation during mouth closure (visual inspection by two authors independently).

- Complete skeletal growth at treatment start (CS5 - CS6 and age>15 years).

- Complete dental arch without missing teeth at treatment start (excluding third molars).

- Completed treatment (no discontinuation).

- No treatment with fixed mandibular advancement devices (e.g. Herbst, Jasperjumper, Forsus).

At the sample selection stage, the initial diagnostic data were used, whereas the final diagnostic data were only checked for availability.

From each patient's diagnostic data file, the initial and final lateral and frontal facial photographs were used for the assessment of the perceived changes in facial appearance by the raters. These were captured with the Frankfurt Horizontal plane parallel to the ground, the teeth in light contact at maximum intercuspation and the lips in a relaxed position.

2.2. Facial Photographs

As reported previously [

17], all digital photographs were edited in Adobe Photoshop (Version 22.0.1, Adobe Systems) to standardize brightness, contrast, and vertical facial height (using Na' to Me' soft tissue points) and adjust the background to white. The photographs were then visually inspected by three independent authors to identify any prominent marks (such as moles, scars) or accessories (such as earrings, tattoos) that could affect the assessments, and these were digitally removed.

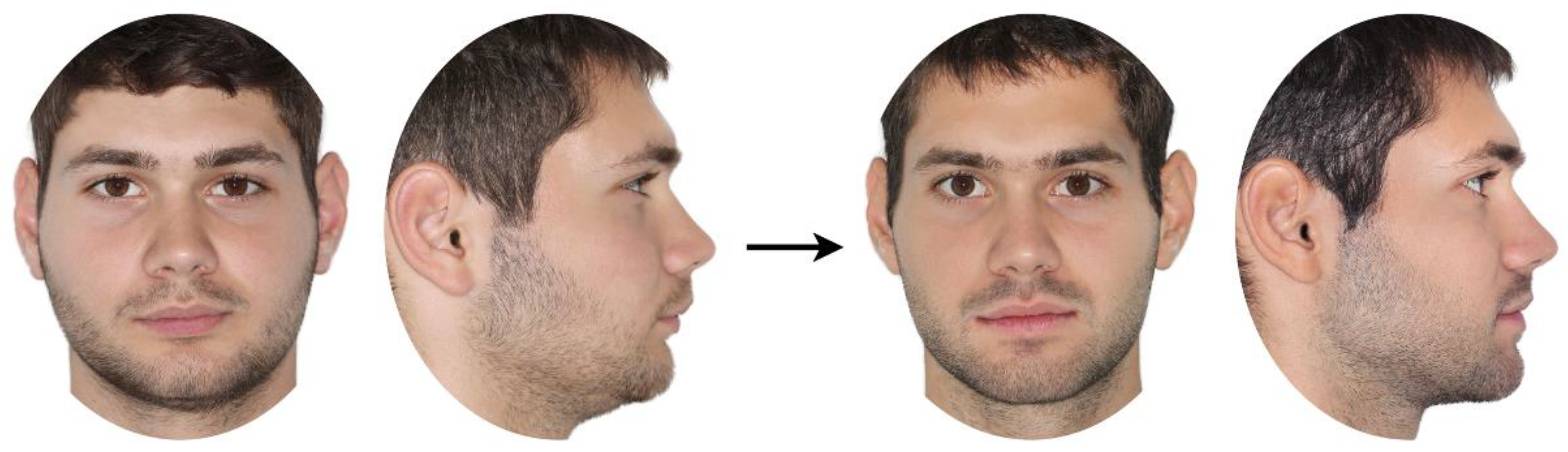

Following image adjustment, a configuration of four images per patient, consisting of pre- and post-treatment profile and frontal facial photos, was set in a landscape-oriented A4 size page as shown in

Figure 1. The subsequent 36 patient photo configurations were printed and presented to the raters as described below.

2.3. Rater Groups

According to a previously published method [

17], each set of images was evaluated by four types of raters: a) orthodontists, b) oral and maxillofacial surgeons, c) convex profile patients and d) laypeople. The number of rated patients per rater session was defined at 12, so that the raters would not experience fatigue or difficulty in the process [

15,

16,

19]. Therefore, the patients under evaluation were randomly assigned into three groups of twelve (six patients from each of treatment group, with balanced sex distribution) using the website

www.random.org (accessed on 23 June 2021). Each patient was then evaluated by 10 members from each rater group for the first three groups, and by 20 laypersons. For this, 30 orthodontists, 30 oral and maxillofacial surgeons, 30 Class II patients, and 60 laypersons rated the patient photos to assess perceived changes in facial appearance following the two treatment regimes.

To form the rater groups of convex profile patients and laypeople, the first white European subjects that agreed to participate were included, aiming at equal sex distribution, wide age range, between 15 and 65 years of age, and wide range of educational level and socioeconomic status. The convex profile patients were selected from the waiting room of the Postgraduate Clinic of the Orthodontics Department, aiming to match the age and sex of these patients with post-treatment age (± three years, or one year for those younger than 19) and sex of the study sample. The first thirty specialists and final-year resident physicians who agreed to participate were included in each rater group. None of the raters had any relation to the patients. Certain raters of the specialists’ groups also participated in an analogous previous study [

17] with a minimum time span of 1 month between the two assessment sessions. These raters assessed different patients in the two sessions and were in both cases unaware of the study aims.

2.4. Questionnaires

Each rater completed a brief personal details questionnaire before assessing the sets of photographs for each patient (

Figure 1), one by one. For half of the cases in each group (three boys and three girls), the initial photos were randomly presented on the right and the final photos on the left, while the remaining cases were presented in the opposite arrangement.

Each set of photographs was accompanied by a previously validated [

15,

16], printed questionnaire, consisting of five questions to be answered on a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) and respective schematic illustrations to enhance understanding. The raters were asked to assess the overall change in facial appearance, the change in the facial area below the nose, the change in the upper and lower lip, and the change in the chin between the left and right photos, and rate it from "extremely negative" to "extremely positive" (

Supplementary Figure S1).

All questionnaires were administered by two researchers who were calibrated to approach the raters similarly. A pilot evaluation using a non-sample case was conducted. The raters were not informed about the study’s purpose or that the photographs depicted treated patients. All questionnaires were completed in a quiet, well-lit room under the discreet supervision of the researcher.

2.5. Data Collection and Verification

The distance from the left end of the visual analogue scale (VAS) to each rater's mark for each question was quantified with an electronic digital caliper (Jainmed, Seoul, Korea), converting the ratings into continuous variables. Measurements were recorded in millimeters, precise to two decimals, in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond WA, USA). When the final photographs were presented on the left, the VAS scores adjusted by subtracting the measured value from 100 to align with the remaining ratings.

To method error in measuring rater responses on the VAS was assessed previously and proved negligible [

17]. Intra-rater reliability for the same questionnaire, used with a similar sample and rater population, has been tested previously and found to be satisfactory [

16], and the questionnaire validity has been verified [

15,

16].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS statistics for Windows (Version 29.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and largely mirrored the methodology of a previous relevant study [

17]. Levene’s test was used to assess the homogeneity of variances, while the Shapiro-Wilk test, along with Q-Q plots and histograms, was employed to evaluate data normality. Parametric and non-parametric statistics were applied accordingly.

Group similarity in key characteristics was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Each patient was rated by ten members of each rater-group and by 20 laypeople. The median of these ratings was considered a reliable assessment for each rater group and was used for further analysis.

The agreement between different rater groups was evaluated using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; two-way mixed model; absolute agreement; average measures). Values above 0.7 indicated strong agreement, while values between 0.5 and 0.7 reflected moderate agreement. This analysis, along with comparative statistics between rater groups, supported the concurrent and statistical conclusion validity of the questionnaires.

Differences between the orthognathic surgery group and the conventional orthodontic treatment group were analyzed using two-way MANOVA. The rater responses to the five questionnaire items were treated as dependent variables, while the two treatment groups and four rater groups were the independent variables. In cases of significant findings, separate ANOVAs were conducted for each dependent variable, followed by post-hoc analysis using Fisher's Least Significant Difference (LSD) test.

Differences between perceived changes in facial appearance by viewing profile only versus combined profile and frontal photos were tested with analogous multivariate analysis, followed by post-hoc tests, where applicable. The data considering the profile only photos have been reported and tested previously [

17] and were reused here.

All cases were two-sided with an alpha level of 0.05. Bonferroni correction was applied for pairwise post-hoc multiple comparisons where necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Treatment Group Characteristics

The two treatment groups had similar demographic, occlusal, and treatment duration characteristics. Their single difference was in facial contour angle, which showed a greater reduction following orthognathic surgery as compared to orthodontic camouflage treatment (

Supplementary Table S1). Cephalometric analysis of additional dental and skeletal outcomes also demonstrated group comparability at baseline, with greater sagittal correction achieved through surgery compared to orthodontic camouflage (

Supplementary Table S2). In group A, 13 patients received bilateral sagittal split osteotomy for mandibular advancement (one of them with additional genioplasty), one patient received LeFort I osteotomy, and 4 patients received bimaxillary surgery (two of them with additional genioplasty).

3.2. Perceived Changes in Facial Appearance

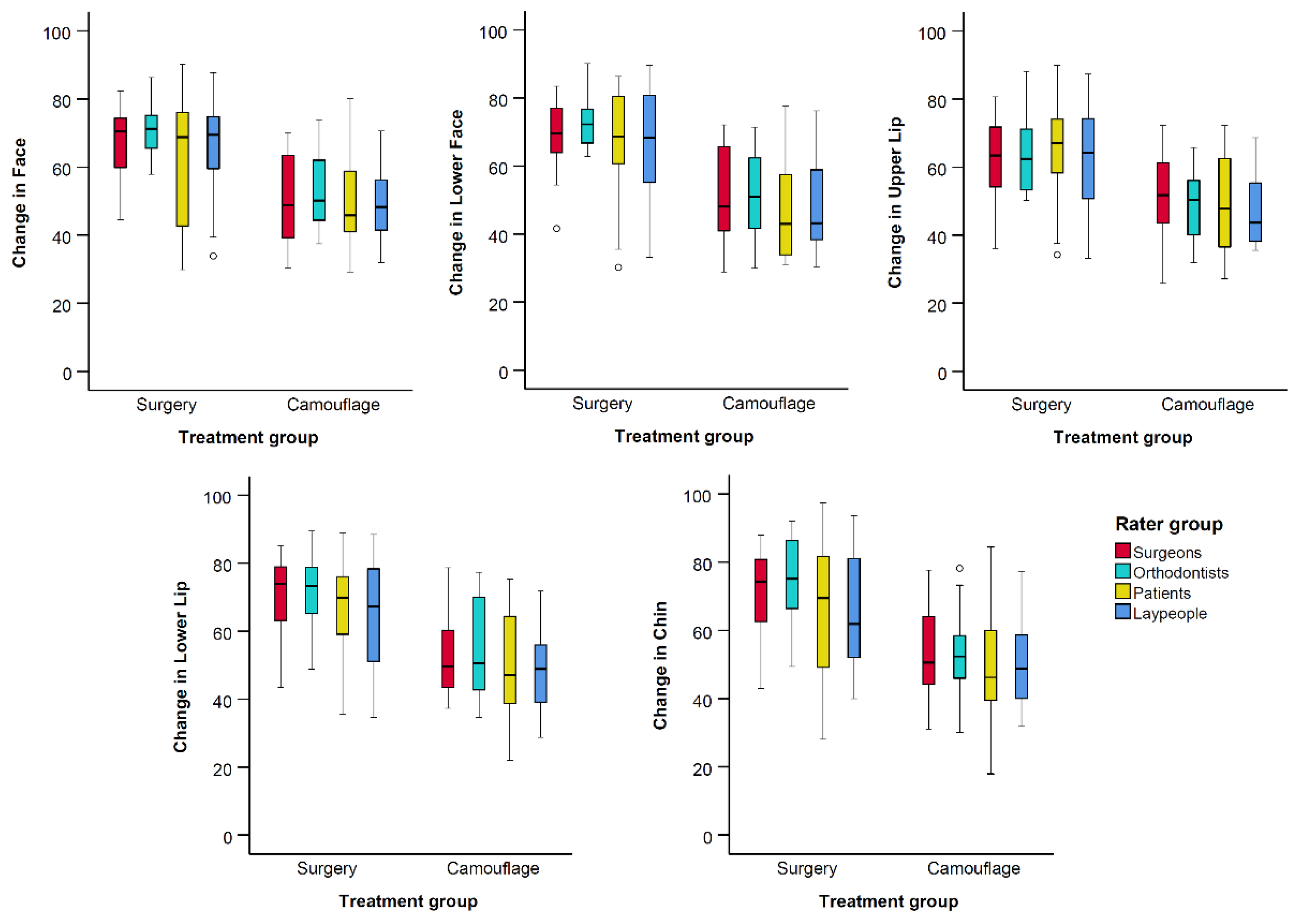

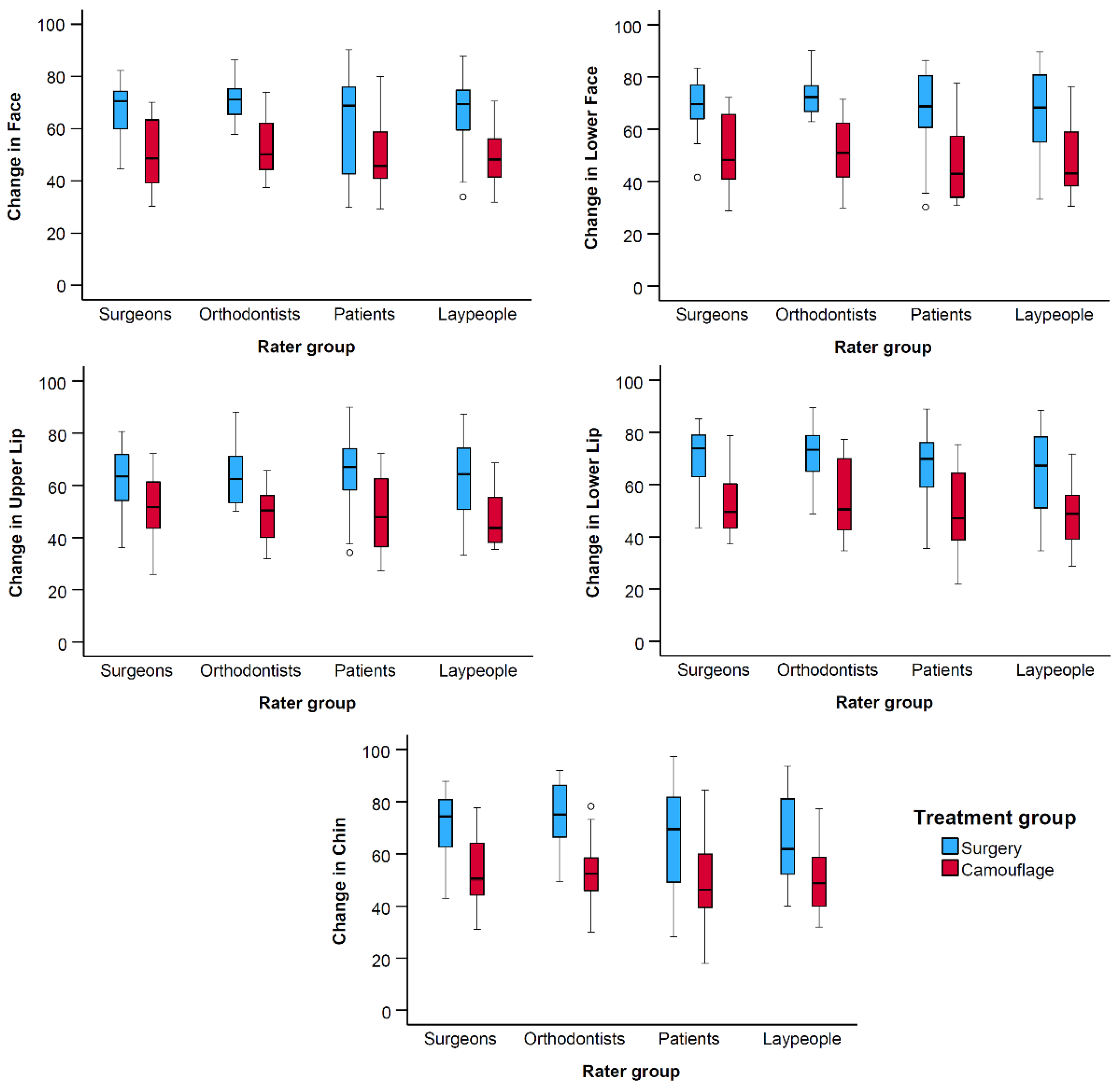

The interrater agreement varied between good and excellent for all assessments (ICC>0.88,

Supplementary Table S3,

Figure 2). The dependent variables showed equal variances across groups (Levene’s test, p > 0.01). Preliminary testing did not show any significant effects of the sex factor on the outcomes (p>0.05), and therefore, this factor was not included in the analysis.

The two treatment groups showed significant differences regarding the perceived changes in facial appearance, as detected by the multivariate analysis (F = 14.63, P < 0.001, Pillai's Trace = 0.36, partial η2 = 0.36). On the contrary, there were no significant differences among rater groups (F = 1.58, P = 0.077, Pillai's Trace = 0.17, partial η2 = 0.06), as well as no combined effects between rater and treatment groups (F = 0.83, P = 0.648, Pillai's Trace = 0.09, partial η2 = 0.03). Separate ANOVAs for each dependent variable showed consistent findings with the multivariate model (

Table 1,

Figure 3).

All rater groups perceived considerably positive changes in facial appearance, following orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery. On the contrary, no changes were perceived for patients that received exclusively orthodontic treatment (

Table 2,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

3.3. Comparison of Perceived Changes by Viewing Profile Only Versus Profile and Frontal Photos

There were statistically significant, but rather limited differences, among rater groups (F = 2.81, P < 0.001, Pillai's Trace = 0.15, partial η2 = 0.05), as well as between photographic setups (F = 2.71, P < 0.021, Pillai's Trace = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.05), regarding the perceived changes in facial appearance. There were no combined effects of the rater groups and the photographic setups on the outcomes (P > 0.05). In contrast, there were substantial differences between the two treatment groups in the perceived changes in facial appearance (F = 31.88, P < 0.001, Pillai's Trace = 0.37, partial η2 = 0.37). The sex factor was not included in the analysis, since preliminary testing did not show any significant effects.

Separate ANOVAs for each dependent variable showed findings consistent with the multivariate analysis, namely no significant difference between the two photographic setups (

Supplementary Table S4). The estimated marginal means for the photographic setups consistently differed on average less than 2 VAS units and these differences were not statistically significant (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

The present study evaluated the perceived differences in facial changes induced by two distinct treatment regimes applied in convex profile patients. The first approach comprised orthodontic treatment combined with orthognathic surgery and the second approach orthodontic treatment alone. The two approaches differ considerably in terms of invasiveness, primarily due to the involvement of a major surgery, which is related to various complications [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Moreover, several patients refuse to undergo orthognathic surgery due the increased costs and the fear for the operation itself as well as for the morbidity and the complications related to the postoperative period [

25,

26]. On the other hand, a primary reason individuals with increased facial convexity seek treatment is to improve their facial appearance [

11,

12,

25]. Therefore, the present assessment that showed that the combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgery approach enhances considerably the facial appearance of convex profile patients, in contrast to orthodontic treatment alone, offers useful information for the decision making process during treatment planning. We analyzed and described the average morphological changes achieved by each approach and their perceptions, so the findings' applicability is based on actual morphological effects rather than individual treatment plan details and responses. These findings should not be viewed as diminishing the value of orthodontic treatment, since it might positively affect dental and eventually smile aesthetics [

27]. But if the enhancement of facial appearance is a major treatment goal, which is often the case, the limitations of single orthodontic treatment should be clearly communicated to patients.

The effectiveness of orthodontic treatment alone in meeting this need has been questioned, even among growing patients aimed at enhancing mandibular growth [

13,

14,

15,

16]. A previous study on actual growing patient images, assessing changes due to functional appliance treatment, identified only slight improvements in profile appearance, compared with normal profile patients who were treated exclusively with fixed appliances. Perceptions of different groups were consistent [

15] and the small differences diminished when profile and frontal facial images were presented simultaneously to the raters [

16]. In the aforementioned studies, small positive changes of about 10% of the VAS scale were detected in the facial appearance of both tested groups. This improvement was primarily attributed to the maturation from preadolescence to adolescence. On the contrary, significant improvements in the facial profile appearance of about 20% were consistently perceived by different groups of assessors in non-growing patients that were subjected to orthognathic surgery [

17] and these were retained when the overall facial appearance was assessed. This is a noteworthy impact, especially given that the orthognathic intervention only modifies facial morphology, which is just one among several factors that could influence the perception of facial appearance [

28]. On the other hand, no changes were perceived for the non-growing, camouflage orthodontic treatment group confirming the validity of the assessments. Previous studies have shown that assessments are modified when different facial views are presented to the raters [

16,

29,

30]. The fact that the considerable improvement perceived in facial profiles remained similarly perceivable when frontal photos were also presented indicates that the changes in overall facial appearance were fundamental. Therefore, the present study offers important insights to the actual treatment effects on facial appearance, so that the patients can receive evidence-based information regarding the expected outcomes, and the anticipated positive impact of treatment on social, psychological, and even economic outcomes. This will facilitate evidence-based decision making during individualized treatment planning relative to the important outcome of facial appearance, which should be considered along with a number of other factors.

Previous research has shown that raters with diverse backgrounds perceive certain facial outcomes differently [

19,

31] and that although objectively measured phenotypic traits contribute significantly to facial attractiveness, a series of other factors is also important [

28]. The fact that in the present study different rater groups perceived changes in facial appearance similarly expands the applicability of the findings supporting their robustness in terms of assessor characteristics. The use of actual patient images instead of largely modified ones is considered a closer approximation of the reality in human interactions, and thus, of associated effects [

32,

33]. Actual patient photos have been rarely used previously for such outcomes and the existing studies presented conflicting findings [

34]. The study of Shell and Woods (2003) [

35] showed similar effects of both treatments on facial attractiveness, whereas the study of Proffit et al. (1992) [

36] identified only minor differences of about 5%, favoring surgical outcomes. Both studies rated sets of frontal and profile facial images for facial attractiveness, but assessed separately the pre- and post-treatment conditions. Different rater groups were also not precisely defined and analyzed. We used slightly modified facial photos to retain the original appearance of individuals, while limiting the effects of confounding factors such as hairstyle and prominent marks or jewelry. Moreover, we applied a robust methodology regarding questionnaire validity and different rater groups that are important from various perspectives in decision-making or treatment impact [

15,

16,

17,

19]. Another strength of the present study is the simultaneous presentation of the pre- and post-treatment images asking the raters to assess changes, after randomizing the treatment phase status. With this design, various individual factors that could potentially confound the assessments - such as skin color, texture, hair color, hairstyle, and certain local morphological features [

1,

28] - are controlled, enhancing the precision of the outcome, which specifically focuses on the perceived impact of morphological changes on facial appearance. Although the surgery cases appeared to be slightly more severe at baseline, the differences between the groups were relatively small and not statistically significant, ensuring their baseline comparability for analysis. The present study identified clear, substantial differences that remained consistent across different types of raters and facial views [

17]. These differences likely emerged as a result of the methodological considerations employed.

The absence of an a priori power calculation could be considered a study limitation, particularly for testing interaction terms. We defined a reasonable sample size based on empirical evidence and resource availability, considering the feasibility in terms of the number of patients and raters. We have comprehensively presented all data, allowing readers to thoroughly evaluate the outcomes. Consistent with previous similar studies [

15,

16,

19], the detection of significant differences between treatment groups suggests sufficient power to address the primary outcomes. The present results need to be tested in different racial groups. The inclusion criteria were defined to exclude extremes in facial morphology, where we would expect greater effects of the surgical approach, but this, as well as the respective effects of camouflage orthodontic treatment, remain to be tested. This study did not test the factors underlying the decisions taken by the patients and their doctors, but focused on the perceived morphological outcomes of the interventions. Pre-treatment facial attractiveness and facial morphology were not thoroughly assessed and should be investigated in future studies as potential mediators of these findings. The present assessment used static images. Functional assessment through actual interactions or presentations of videos might have modified the outcomes. Finally, this study assessed exclusively changes in facial appearance, not accounting for dental or smile aesthetics, which might have affected the outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgery treatment of facial convexity is an efficient treatment approach for the enhancement of facial appearance. On the contrary, orthodontic treatment alone has neither positive nor negative impact on facial appearance. Different rater groups, including laypeople, perceived facial changes similarly.

These findings have important clinical implications for adult patients with facial convexity, and should be carefully considered during patient consultation and individualized treatment planning.. For patients seeking significant facial aesthetic improvement, clinicians should discuss the limitations of orthodontic treatment alone and emphasize the potential benefits of combining it with orthognathic surgery. Clear communication regarding expected outcomes is crucial, especially in managing patient expectations. Orthognathic surgery should be recommended to those whose primary goal is facial profile enhancement, while patients less concerned with facial aesthetic changes may opt for orthodontic treatment alone. In both cases, a multidisciplinary approach and thorough pre-treatment evaluation are essential to ensure optimal patient satisfaction.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Questionnaire to assess changes in facial appearance; Table S1: Overview of the patient sample characteristics; Table S2: Additional patient sample characteristics; Table S3: Agreement among rater groups; Table S4: ANOVAS testing the effect of photographic setup, rater group, and treatment group on the assessed changes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P., and N.G.; methodology, S.P., N.G, I.S. and I.I.; software, S.P. and N.G.; validation, S.P. and N.G.; formal analysis, N.G.; investigation, S.P.; resources, S.P., N.G, I.S. and I.I.; data curation, S.P., I.S. and N.G. ; writing—original draft preparation, S.P. and N.G.; writing—review and editing, S.P., N.G, I.S. and I.I.; visualization, S.P., N.G, I.S.; supervision, N.G, I.S. and I.I.; project administration, I.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Dental School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece prior to study commencement (Date of Approval: 22.06.2018, Protocol Number: 361).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient shown in

Figure 1 to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Little, A.C.; Jones, B.C.; DeBruine, L.M. Facial Attractiveness: Evolutionary Based Research. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011, 366, 1638–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, S.; Rivkin, A.; Sykes, J.M.; Teller, C.F.; Weinkle, S.H.; Shumate, G.T.; Gallagher, C.J. Aesthetic Treatment Positively Impacts Social Perception: Analysis of Subjects From the HARMONY Study. Aesthet Surg J 2019, 39, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremona, M.; Bister, D.; Sheriff, M.; Abela, S. Quality-of-Life Improvement, Psychosocial Benefits, and Patient Satisfaction of Patients Undergoing Orthognathic Surgery: A Summary of Systematic Reviews. European Journal of Orthodontics 2022, 44, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Cui, G.; Chung, Y.; Zheng, W. The Faces of Success: Beauty and Ugliness Premiums in e-Commerce Platforms. Journal of Marketing 2020, 84, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Berganza, M.; Amico, A.; Loreto, V. Subjectivity and Complexity of Facial Attractiveness. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Cheng, Q.; Lin, W.; Lin, J.; Mo, L. Different Influences of Facial Attractiveness on Judgments of Moral Beauty and Moral Goodness. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Arqoub, S.H.; Al-Khateeb, S.N. Perception of Facial Profile Attractiveness of Different Antero-Posterior and Vertical Proportions. European Journal of Orthodontics 2011, 33, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkkahraman, H.; Gökalp, H. Facial Profile Preferences among Various Layers of Turkish Population. Angle Orthod 2004, 74, 640–647. [Google Scholar]

- Pacha, M.M.; Fleming, P.S.; Johal, A. Complications, Impacts, and Success Rates of Different Approaches to Treatment of Class II Malocclusion in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 2020, 158, 477–494.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Choi, Y.-K. Current Trends in Orthognathic Surgery. Arch Craniofac Surg 2021, 22, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Pereira, C.; Abreu, L.G.; Dick, B.D.; De Luca Canto, G.; Paiva, S.M.; Flores-Mir, C. Patient Satisfaction after Orthodontic Treatment Combined with Orthognathic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Angle Orthod 2016, 86, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachêco-Pereira, C.; Pereira, J.R.; Dick, B.D.; Perez, A.; Flores-Mir, C. Factors Associated with Patient and Parent Satisfaction after Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2015, 148, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koretsi, V.; Zymperdikas, V.F.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Treatment Effects of Removable Functional Appliances in Patients with Class II Malocclusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Orthod 2015, 37, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zymperdikas, V.F.; Koretsi, V.; Papageorgiou, S.N.; Papadopoulos, M.A. Treatment Effects of Fixed Functional Appliances in Patients with Class II Malocclusion: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Orthod 2016, 38, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiouli, K.; Topouzelis, N.; Papadopoulos, M.A.; Gkantidis, N. Perceived Facial Changes of Class II Division 1 Patients with Convex Profiles after Functional Orthopedic Treatment Followed by Fixed Orthodontic Appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2017, 152, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouloumi, M.E.; Tsiouli, K.; Psomiadis, S.; Kolokitha, O.E.; Topouzelis, N.; Gkantidis, N. Facial Esthetic Outcome of Functional Followed by Fixed Orthodontic Treatment of Class II Division 1 Patients. Prog Orthod 2019, 20, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomiadis, S.; Gkantidis, N.; Sifakakis, I.; Iatrou, I. Perceived Effects of Orthognathic Surgery versus Orthodontic Camouflage Treatment of Convex Facial Profile Patients. J Clin Med 2023, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.T.; McFadden, L.R.; Wiltshire, W.A.; Pershad, N.; Baker, A.B. Profile Changes in Orthodontic Patients Treated with Mandibular Advancement Surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2009, 135, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkantidis, N.; Papamanou, D.A.; Christou, P.; Topouzelis, N. Aesthetic Outcome of Cleft Lip and Palate Treatment. Perceptions of Patients, Families, and Health Professionals Compared to the General Public. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2013, 41, e105–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyneke, J. Essentials of Orthognathic Surgery; 3rd ed.; 2022.

- Agbaje, J.; Luyten, J.; Politis, C. Pain Complaints in Patients Undergoing Orthognathic Surgery. Pain Res Manag 2018, 2018, 4235025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brons, S.; Becking, A.G.; Tuinzing, D.B. Value of Informed Consent in Surgical Orthodontics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 67, 1021–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friscia, M.; Sbordone, C.; Petrocelli, M.; Vaira, L.A.; Attanasi, F.; Cassandro, F.M.; Paternoster, M.; Iaconetta, G.; Califano, L. Complications after Orthognathic Surgery: Our Experience on 423 Cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017, 21, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jędrzejewski, M.; Smektała, T.; Sporniak-Tutak, K.; Olszewski, R. Preoperative, Intraoperative, and Postoperative Complications in Orthognathic Surgery: A Systematic Review. Clin Oral Invest 2015, 19, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hågensli, N.; Stenvik, A.; Espeland, L. Patients Offered Orthognathic Surgery: Why Do Many Refrain from Treatment? J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014, 42, e296–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, M.; Qadeer, T.A.; Fahim, M.F. Reasons for Refusing Orthognathic Surgery by Orthodontic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J Pak Med Assoc 2022, 72, 1954–1962. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, G.; Christopoulou, I.; Gkantidis, N.; Verna, C.; Pandis, N.; Kanavakis, G. The Effect of Orthodontic Treatment on Smile Attractiveness: A Systematic Review. Prog Orthod 2023, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanavakis, G.; Halazonetis, D.; Katsaros, C.; Gkantidis, N. Facial Shape Affects Self-Perceived Facial Attractiveness. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0245557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, V.F.; Sforza, C.; Poggio, C.E.; Colombo, A.; Tartaglia, G. The Relationship between Facial 3-D Morphometry and the Perception of Attractiveness in Children. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 1997, 12, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, W.J.; O’Donnell, J.M. Panel Perception of Facial Attractiveness. Br J Orthod 1990, 17, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, M.T.; Sandham, A.; Soh, J.; Wong, H.B. Outcome of Orthognathic Surgery in Chinese Patients. A Subjective and Objective Evaluation. Angle Orthod 2007, 77, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockley, A.; Weinstein, M.; Borislow, A.J.; Braitman, L.E. Photos vs Silhouettes for Evaluation of African American Profile Esthetics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2012, 141, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithon, M.M.; Silva, I.S.N.; Almeida, I.O.; Nery, M.S.; de Souza, M.L.; Barbosa, G.; Dos Santos, A.F.; da Silva Coqueiro, R. Photos vs Silhouettes for Evaluation of Profile Esthetics between White and Black Evaluators. Angle Orthod 2014, 84, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouskoura, T.; Ochsner, T.; Verna, C.; Pandis, N.; Kanavakis, G. The Effect of Orthodontic Treatment on Facial Attractiveness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur J Orthod 2022, 44, 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shell, T.L.; Woods, M.G. Perception of Facial Esthetics: A Comparison of Similar Class II Cases Treated with Attempted Growth Modification or Later Orthognathic Surgery. Angle Orthod 2003, 73, 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Proffit, W.R.; Phillips, C.; Douvartzidis, N. A Comparison of Outcomes of Orthodontic and Surgical-Orthodontic Treatment of Class II Malocclusion in Adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1992, 101, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).