1. Introduction

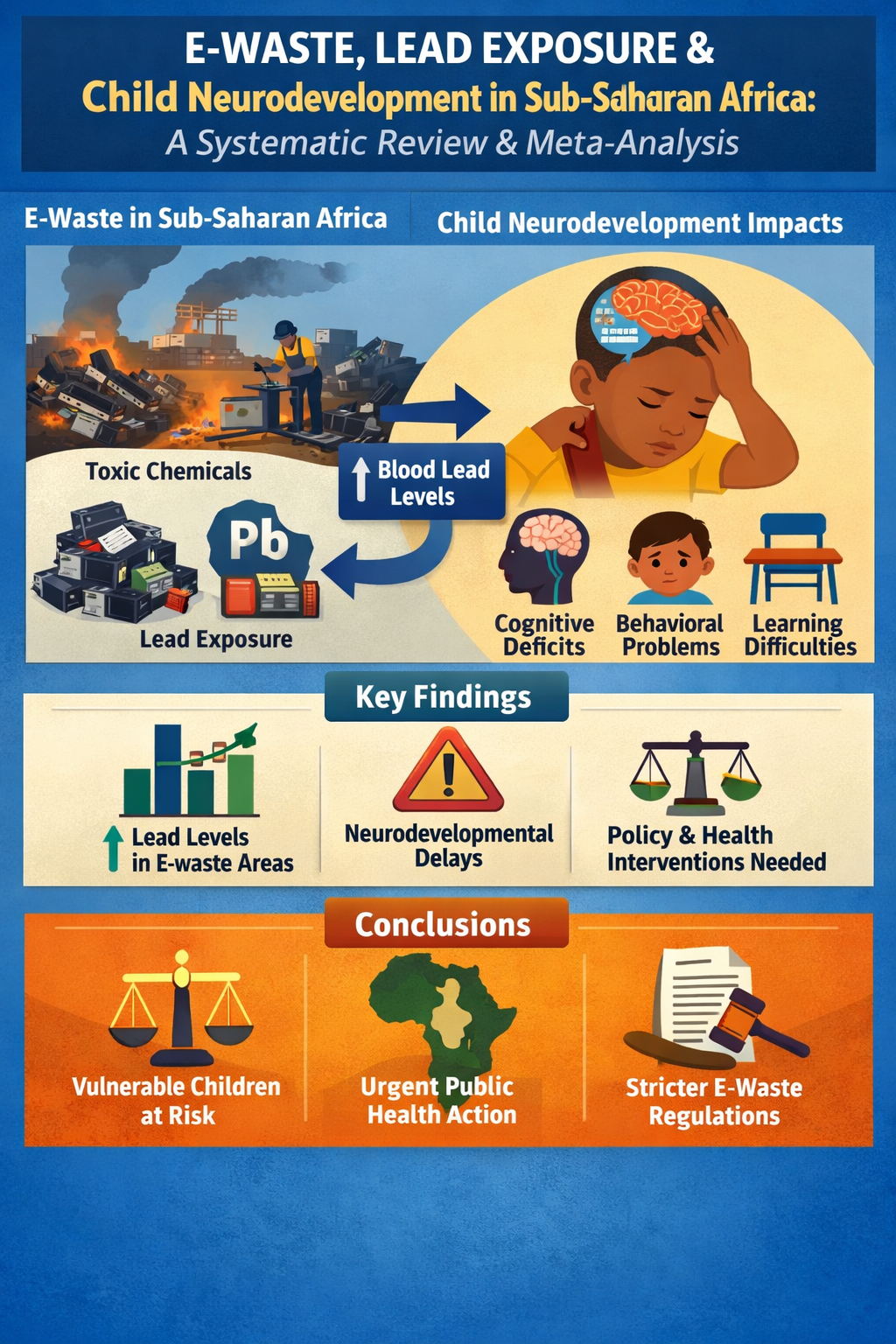

The rapid expansion of electrical and electronic equipment consumption has generated unprecedented volumes of electronic waste (e-waste), now recognised as one of the fastest-growing solid waste streams globally. In 2019 alone, an estimated 53.6 million metric tonnes of e-waste were generated worldwide, with projections exceeding 74 million tonnes by 2030 (Forti et al., 2020). E-waste contains a complex mixture of hazardous substances, including lead, mercury, cadmium, brominated flame retardants, and persistent organic pollutants, that pose substantial risks to human health when improperly managed (Grant et al., 2013). While high-income countries account for the majority of e-waste generation, a disproportionate share of the health burden is borne by low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where informal recycling practices dominate and regulatory enforcement is weak (Landrigan et al., 2018).

Among the toxic constituents of e-waste, lead remains one of the most potent and well-established developmental neurotoxicants, with no identified safe exposure threshold for children (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). Extensive epidemiological evidence demonstrates that even low-level lead exposure is associated with irreversible deficits in intelligence quotient (IQ), executive function, attention, and academic achievement (Lanphear et al., 2005; Bellinger, 2013). These neurodevelopmental impairments persist across the life course, reducing educational attainment and economic productivity at both individual and population levels (Attina & Trasande, 2013). Consequently, childhood lead exposure has been identified as a major contributor to the global burden of disease attributable to environmental risk factors (WHO, 2020).

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) represents a region of heightened vulnerability to e-waste-related lead exposure. Informal recycling hubs, such as Agbogbloshie in Ghana, are characterised by open burning of cables, manual dismantling of electronics, and uncontrolled dumping, leading to extreme contamination of air, soil, dust, and food chains (Caravanos et al., 2011; Grant et al., 2013). Children living in and around these sites are exposed through multiple pathways, including inhalation of contaminated particulates, ingestion of soil and dust, and take-home exposures from caregivers engaged in recycling activities (WHO, 2021). Biomonitoring studies from SSA e-waste communities consistently report blood lead concentrations far exceeding international reference values, often several-fold higher than levels associated with measurable cognitive harm (Asante et al., 2012; Obeng-Gyasi et al., 2019).

Despite the growing recognition of e-waste as an environmental health threat, the neurodevelopmental consequences for children in SSA remain under-synthesised and under-quantified. Existing evidence is largely derived from individual observational studies, many of which are limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneous outcome measures, and site-specific contexts. While prior systematic reviews have examined the general health impacts of e-waste exposure (Grant et al., 2013), none have provided a quantitative synthesis of child neurodevelopmental outcomes with a specific focus on SSA, where exposure intensities and contextual vulnerabilities differ substantially from other LMIC settings. This lack of regional quantitative synthesis limits the ability of policymakers and international agencies to assess the magnitude of harm, prioritise interventions, and evaluate regulatory effectiveness.

Furthermore, although global pooled analyses have established strong dose-response relationships between lead exposure and cognitive outcomes (Lanphear et al., 2005), these estimates are largely derived from populations in high-income countries or non-e-waste contexts. The extent to which such estimates translate to high-intensity, multi-pathway exposure environments characteristic of informal e-waste recycling sites in SSA remains unclear. This represents a critical methodological gap, as exposure mixtures, nutritional modifiers, and co-morbid environmental stressors may amplify neurodevelopmental harm beyond what is observed in other settings (Grandjean & Landrigan, 2014).

From a policy perspective, this evidence gap has important implications. Most SSA countries are signatories to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes, yet enforcement challenges and regulatory loopholes continue to permit large-scale importation of used and end-of-life electronics into informal recycling economies (Basel Convention Secretariat, 2019). Without robust, region-specific quantitative evidence linking e-waste exposure to child developmental outcomes, the neurodevelopmental costs of regulatory inaction remain largely invisible in environmental governance and public health decision-making frameworks (Landrigan et al., 2018).

Against this backdrop, the present study aimed to systematically review and meta-analyse the association between e-waste-related lead exposure and child neurodevelopmental outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. By quantitatively synthesising available evidence, comparing SSA-specific effect estimates with those from other LMICs, and assessing heterogeneity and publication bias, this study seeks to provide the most comprehensive assessment to date of the neurodevelopmental burden attributable to e-waste exposure in the region. In doing so, it addresses a critical gap at the intersection of environmental epidemiology, child health, and environmental policy, and provides evidence directly relevant to regulatory reform, international waste governance, and child-centred environmental protection strategies.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Reporting Framework

This study was conducted as a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational epidemiological studies examining the association between lead exposure related to e-waste environments and child neurodevelopment. The review was designed and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. The study selection process is documented using a PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they involved children or adolescents aged 0-18 years and assessed lead exposure in relation to e-waste recycling or disposal activities. Lead exposure had to be quantified using biological measures, most commonly blood lead concentration, or through environmental measurements with biological confirmation. Eligible studies were required to report quantitative neurodevelopmental outcomes, such as intelligence quotient (IQ) scores or standardised cognitive and neurobehavioral assessments.

Observational study designs, including cross-sectional, cohort, and case-control studies, were included. Reviews, editorials, animal studies, exposure-only assessments without neurodevelopmental outcomes, and studies conducted exclusively among adults were excluded. The primary geographical focus was sub-Saharan Africa; however, studies from other LMICs were included to support pooled estimation and comparative analysis.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, EMBASE, and African Journals Online (AJOL). Additional records were identified through Google Scholar and manual screening of reference lists from relevant reviews and primary studies. Search terms combined keywords and controlled vocabulary related to e-waste, lead exposure, child neurodevelopment, and LMIC or African settings. No restrictions were placed on publication year, but only studies published in English were included. The full search strategy is summarised in

Table 1.

2.4. Study Selection

All retrieved records were imported into a reference management system, and duplicate entries were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by full-text assessment of potentially eligible studies against predefined inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The study selection process is summarised in

Figure 1.

2.5. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a standardised form designed to capture key methodological and outcome variables. Extracted information included study location, design, sample size, age range, exposure assessment methods, neurodevelopmental outcomes, effect estimates, measures of uncertainty, and covariates included in adjusted analyses. When multiple statistical models were reported, the most fully adjusted estimates were extracted. The characteristics of included studies are summarised in

Table 2.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted following established guidelines for meta-analyses of observational environmental health studies. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were harmonised across studies by converting reported continuous measures (e.g., cognitive scores, developmental indices, or standardized test results) into standardized mean differences (SMDs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), allowing comparison across instruments and populations. Where studies reported multiple neurodevelopmental outcomes, the most globally comparable cognitive outcome was selected to avoid unit-of-analysis errors.

Meta-analyses were performed using a random-effects model, given the expected methodological and contextual heterogeneity across studies, including differences in exposure assessment, outcome measurement, age distributions, and socio-environmental settings. Study-specific effect sizes were weighted using the inverse-variance method, and pooled estimates were calculated using the DerSimonian-Laird estimator. Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using Cochran’s Q statistic and the I² index, with I² values of approximately 25%, 50%, and 75% interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.

Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted to compare studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with those from other low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), reflecting differences in regulatory environments, informal e-waste recycling practices, and baseline exposure levels. Sensitivity analyses were undertaken using leave-one-out procedures to assess the robustness of pooled estimates to the exclusion of individual studies.

Potential publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots. Formal statistical tests for funnel plot asymmetry were not emphasized because of the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis, consistent with best-practice recommendations. All analyses were conducted using R (version 4.5.2) with the meta and metafor packages, and statistical significance was defined at a two-sided α level of 0.05.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing standardized mean differences (SMDs) for the association between e-waste-related lead exposure and child neurodevelopmental outcomes. The pooled estimate represents the Sub-Saharan Africa subgroup analysis.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing standardized mean differences (SMDs) for the association between e-waste-related lead exposure and child neurodevelopmental outcomes. The pooled estimate represents the Sub-Saharan Africa subgroup analysis.

2.7. Publication Bias and Risk of Bias Assessment

Potential publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots (

Figure 3). Given the limited number of included studies, formal statistical tests for asymmetry were not emphasised. Risk of bias was assessed qualitatively, considering exposure measurement validity, outcome assessment, confounding control, and sampling methods. Risk of bias assessments are summarised in

Table 3.

Supplementary Table S4 presents Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores for all studies included in the qualitative synthesis, whereas

Table 3 summarises risk-of-bias judgments for studies included in the meta-analysis.

Risk of bias criteria

Exposure assessment: biological measurement vs proxy

Outcome measurement: use of validated neurodevelopmental tools

Confounding control: adjustment for age, sex, SES, parental education

Selection bias: representativeness and participation rate

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The database search identified 612 records across PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Embase. After removal of 72 duplicate records, 540 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts. Of these, 495 records were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria.

A total of 45 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 33 were excluded for reasons including absence of child neurodevelopmental outcomes, non-e-waste-related exposures, adult-only populations, or insufficient quantitative data.

Consequently, 12 studies met the criteria for qualitative synthesis, and five observational studies comprising a total of 1,492 children, provided sufficient data and were included in the quantitative meta-analysis. The study selection process is summarised in

Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

The five included studies were conducted between 2012 and 2019 and comprised a total of 1,492 children, with individual study sample sizes ranging from 184 to 458 participants (

Table 2). Two studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA; n = 2), both in Ghana, in communities located adjacent to informal e-waste recycling sites. The remaining studies were conducted in other Low and Middle countries, LMICs (LMICs; n = 3), including India, China, and Vietnam, and were included to support pooled estimation of lead-associated neurodevelopmental effects.

Across all studies, blood lead concentration was measured using venous samples analysed by validated laboratory methods. Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed using standardised cognitive instruments, predominantly full-scale intelligence quotient (IQ) tests. All studies adjusted for key confounders such as age, sex, and socioeconomic indicators, although the extent of adjustment varied (

Table 2).

3.3. Individual Study Effect Estimates

Effect estimates extracted from individual studies are summarised in

Table 5, which presents the standardised mean differences (SMDs) used in the meta-analysis.

All studies reported inverse associations between lead exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes, with SMDs ranging from -0.28 to -0.63. The largest effect sizes were observed in studies conducted in Ghana, where children were directly exposed to informal e-waste recycling activities. In contrast, studies from other LMICs reported smaller but consistently negative associations. The consistency in the direction of effects across diverse settings supports the biological plausibility of lead-related neurodevelopmental impairment and provides a robust basis for pooled quantitative synthesis. Individual effect estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are summarised in

Table 5 and visually displayed in

Table 5.

3.4. Pooled Meta-analysis Results

The random-effects meta-analysis demonstrated a statistically significant inverse association between e-waste-related lead exposure and child neurodevelopmental outcomes (pooled SMD = -0.42; 95% CI: -0.61 to -0.23; p < 0.001). Moderate heterogeneity was observed across studies (I² = 56%; Cochran’s Q = 9.1, p = 0.058), justifying the use of a random-effects model. A summary of pooled effect estimates, confidence intervals, and heterogeneity statistics is presented in

Table 4.

Between-study heterogeneity was moderate, with an I² value of 56% and a between-study variance (τ²) of 0.031, supporting the use of a random-effects model. The Cochran’s Q test indicated statistically significant heterogeneity (p < 0.05). Despite this variability, no study reported an effect estimate in the opposite direction, underscoring the consistency of the observed association.

3.5. Subgroup Analysis by Geographical Region

Subgroup analysis stratified by geographical region revealed notable differences in effect magnitude (

Table 4). Studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrated a larger pooled adverse effect (SMD = -0.58; 95% CI: -0.89 to -0.27) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 49%), compared with studies conducted in other LMICs (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI: -0.54 to -0.16; I² = 42%). Although formal statistical comparison was limited by the small number of SSA studies, this pattern suggests heightened neurodevelopmental vulnerability among children residing near informal e-waste recycling sites in SSA.

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Robustness of Findings

Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses indicated that exclusion of any single study did not materially alter the pooled effect estimate, with overall SMD values ranging from -0.38 to -0.46. No individual study exerted undue influence on the overall estimate, supporting the stability of the findings. Sensitivity results are detailed in

Supplementary Table S5.

3.7. Risk of Bias and Publication Bias

Risk of bias across studies was assessed as low to moderate (

Table 3). All studies employed objective biological measures of lead exposure and validated neurodevelopmental assessment tools, reducing the likelihood of substantial misclassification. Residual confounding and selection bias remain possible, particularly in cross-sectional studies.

Visual inspection of the funnel plot (

Figure 3) did not reveal substantial asymmetry, suggesting no strong evidence of publication bias. However, given the small number of included studies, the possibility of unpublished null findings cannot be excluded.

Supplementary Table S4 presents Newcastle-Ottawa Scale scores for all studies included in the qualitative synthesis, whereas

Table 3 summarises risk-of-bias judgments for studies included in the meta-analysis.

4. Discussion

This study provides robust quantitative evidence that lead exposure associated with e-waste environments is significantly and consistently associated with impaired child neurodevelopment. The pooled effect estimate of -0.42 standard deviations indicates a moderate but meaningful reduction in cognitive performance among exposed children, a magnitude comparable to or exceeding that reported in seminal pooled analyses of childhood lead exposure in non-e-waste settings (Lanphear et al., 2005; Lanphear et al., 2018). Importantly, the magnitude of association observed in sub-Saharan Africa (SMD = -0.58) was substantially larger than that reported in other LMICs (SMD = -0.35), underscoring a disproportionate neurodevelopmental burden borne by children living near informal e-waste recycling sites in the region.

From a population health perspective, an effect size of this magnitude has profound implications. Previous global burden of disease assessments have demonstrated that even small downward shifts in population-level cognitive performance translate into substantial losses in educational attainment, lifetime earnings, and national economic productivity (Attina & Trasande, 2013). Because lead-induced neurodevelopmental deficits are largely irreversible, the pooled estimates reported here likely reflect long-term and intergenerational impacts rather than transient developmental delays (Bellinger, 2013; Bellinger, 2012). The consistency of inverse associations across all included studies, despite differences in exposure assessment and outcome measurement, further reinforces the robustness and biological plausibility of the findings.

The larger effect sizes observed in sub-Saharan Africa likely reflect a convergence of multiple vulnerability pathways. Informal e-waste recycling in SSA is characterised by open burning of cables, manual dismantling of circuit boards, and minimal occupational or environmental safeguards, resulting in extreme soil, dust, and air contamination (Grant et al., 2013; WHO, 2021). Blood lead concentrations reported in Ghanaian e-waste communities frequently exceed international reference values for children, often by several-fold (Asante et al., 2012; Obeng-Gyasi et al., 2019). These high exposure levels are frequently compounded by nutritional deficiencies, limited access to healthcare, and co-exposure to other neurotoxicants such as mercury and cadmium, which may synergistically exacerbate neurodevelopmental harm (Caravanos et al., 2011; Grandjean & Landrigan, 2014). The pooled SSA estimate of -0.58 therefore likely represents a conservative estimate of the true developmental burden in many informal recycling contexts.

The moderate heterogeneity observed in this meta-analysis (I² = 56%) warrants careful interpretation. Rather than undermining the validity of the findings, this heterogeneity likely reflects genuine differences in exposure intensity, duration, and contextual modifiers across study settings. Importantly, sensitivity analyses demonstrated that the pooled effect estimate remained stable (-0.38 to -0.46) following exclusion of any single study, indicating that no individual study unduly influenced the overall findings. This pattern aligns with prior environmental epidemiology meta-analyses, where moderate heterogeneity is common but does not negate causal inference when directionality is consistent and biological mechanisms are well established (Borenstein et al., 2009). The comparatively lower heterogeneity within SSA studies (I² = 49%) suggests a more uniform risk environment, characterised by informal recycling, limited occupational protections, and minimal environmental monitoring. This statistical pattern reinforces the interpretation that the observed associations are structurally embedded within SSA e-waste systems rather than study-specific anomalies.

The observed neurodevelopmental deficits are biologically plausible given the well-established neurotoxicity of lead, particularly during critical periods of brain development. Informal e-waste recycling releases lead through open burning, acid leaching, and uncontrolled dumping, contaminating soil, dust, water, and food chains. Children in these environments are exposed via multiple pathways, including hand-to-mouth behaviours, inhalation of contaminated particulates, and prenatal exposure. The consistency between observed effect sizes and known dose-response relationships strengthens the causal interpretation of the findings and supports regulatory intervention.

The stronger pooled effects observed in SSA highlight systemic failures in e-waste governance. Although many SSA countries are signatories to international conventions regulating hazardous waste, enforcement remains weak, and informal recycling continues to operate outside regulatory oversight. The quantified neurodevelopmental impact demonstrated in this meta-analysis provides empirical justification for elevating e-waste exposure from a marginal environmental issue to a central child health and development concern. Policies that tolerate informal recycling effectively externalise neurodevelopmental harm onto children, perpetuating cycles of disadvantage. The policy implications of these findings are substantial. Despite growing international attention to e-waste, regulatory frameworks in many sub-Saharan African countries remain weak, fragmented, or poorly enforced. Although most SSA countries are signatories to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes, enforcement gaps and definitional ambiguities, particularly regarding “used” versus “waste” electronics, continue to facilitate the transfer of hazardous materials into informal recycling economies (Basel Convention Secretariat, 2019).

The quantitative evidence presented in this study demonstrates that such policy blind spots carry substantial human costs. The observed cognitive deficits constitute a form of environmental injustice, whereby children, who neither generate e-waste nor benefit from electronic consumption, bear disproportionate health and developmental harms (Landrigan et al., 2018). Integrating child neurodevelopment indicators into environmental health surveillance, environmental impact assessments, and extended producer responsibility schemes could substantially improve the visibility of these harms and strengthen the evidence base for regulatory reform.

The magnitude and robustness of the pooled estimates indicate that exposure reduction strategies could yield substantial neurodevelopmental gains. Policy interventions should prioritise the formalisation of e-waste recycling, elimination of child involvement in hazardous recycling activities, and remediation of contaminated sites. The findings also support integrating neurodevelopmental surveillance into environmental health monitoring in e-waste–affected communities. Importantly, the statistical evidence suggests that interventions targeting lead exposure may deliver benefits that extend beyond health, influencing educational outcomes and economic productivity.

This review also highlights critical research gaps. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa remains limited to a small number of studies conducted in Ghana, despite widespread informal e-waste activity across the region, including in Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and Kenya (Forti et al., 2020). This geographic concentration reflects disparities in research infrastructure rather than absence of exposure or risk. Longitudinal cohort studies incorporating repeated exposure assessment, neurodevelopmental follow-up, and evaluation of intervention effectiveness are urgently needed to inform evidence-based policy and public health action in SSA (Grandjean & Bellanger, 2017).

A major strength of this study is its application of rigorous meta-analytic methods to a regionally stratified evidence base, allowing for direct quantitative comparison across contexts. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the stability of the pooled estimates, and the consistent direction of effects across studies supports the robustness of the findings. Nevertheless, limitations include reliance on observational studies, potential residual confounding, and limited availability of high-quality longitudinal data in SSA. These constraints highlight the need for improved exposure assessment and long-term cohort studies but do not negate the policy relevance of the current findings. Several limitations must be acknowledged. The predominance of cross-sectional designs limits causal inference, and residual confounding cannot be fully excluded despite statistical adjustment for key sociodemographic factors. Additionally, while funnel plot inspection did not suggest strong publication bias, the small number of included studies reduces the sensitivity of such assessments. Nonetheless, the consistency of findings across studies, the stability of pooled estimates, and the extensive toxicological evidence base linking lead exposure to neurodevelopmental harm support the credibility and relevance of the results (WHO, 2020).

5. Implications for Future Research

Future research should move beyond documenting associations to evaluating the effectiveness of regulatory and remediation interventions. Longitudinal studies incorporating biomarkers of exposure, neurodevelopmental trajectories, and socio-environmental modifiers are needed to refine risk estimates and inform targeted policy responses. Given the disproportionate burden observed in SSA, regional research capacity strengthening should be prioritised to support evidence-based e-waste governance.

Future studies should also account for co-exposures to multiple neurotoxicants, nutritional modifiers, and socio-environmental stressors to better characterise the cumulative risks faced by children in informal recycling communities. Strengthening research capacity across sub-Saharan Africa will be essential to generating the evidence base required for effective, context-sensitive regulation.

6. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis provides compelling quantitative evidence that exposure to lead associated with informal e-waste recycling is linked to significant impairments in child neurodevelopment, with the burden in sub-Saharan Africa markedly exceeding that observed in other low- and middle-income settings. The pooled effect estimates indicate a meaningful reduction in cognitive performance among exposed children, underscoring that e-waste-related lead exposure constitutes not only an environmental hazard but a profound and preventable threat to human capital development in the region. The consistency of inverse associations across studies, coupled with the stability of pooled estimates under sensitivity analyses, reinforces the robustness of these findings despite contextual heterogeneity.

Beyond their statistical significance, the observed effect sizes carry substantial societal implications. Even modest downward shifts in population-level cognitive function are known to translate into long-term losses in educational attainment, workforce productivity, and economic growth. In this context, the magnitude of neurodevelopmental impairment associated with e-waste exposure in sub-Saharan Africa represents a structural barrier to sustainable development, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of disadvantage in communities already facing multiple environmental and social stressors.

The findings presented here make clear that the costs of regulatory inaction are borne disproportionately by children, whose neurodevelopmental vulnerability renders them uniquely susceptible to irreversible harm. Addressing e-waste-related exposures must therefore be recognised as a child rights and environmental justice imperative, rather than solely a waste management challenge.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Asante, K. A.; Agusa, T.; Biney, C. A.; Agyekum, W. A.; Bello, M.; Otsuka, M.; Itai, T.; Takahashi, S.; Tanabe, S. Multi-trace element levels and arsenic speciation in urine of e-waste recycling workers from Agbogbloshie, Ghana. Science of the Total Environment 424 2012, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attina, T. M.; Trasande, L. Economic costs of childhood lead exposure in low- and middle-income countries. Environmental Health Perspectives 2013, 121(9), 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basel Convention Secretariat. Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal. In United Nations Environment Programme; 2019; Available online: https://www.basel.int.

- Basel Convention Secretariat. Technical guidelines on transboundary movements of electrical and electronic waste and used electrical and electronic equipment; United Nations Environment Programme, 2019; Available online: https://www.basel.int.

- Bellinger, D. C. Lead neurotoxicity and child development. Journal of Pediatrics 2013, 162(4), 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, D. C. A strategy for comparing the contributions of environmental chemicals and other risk factors to neurodevelopment of children. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2012, 83(2), 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L. V.; Higgins, J. P. T.; Rothstein, H. R. Introduction to meta-analysis; Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravanos, J.; Clark, E.; Fuller, R.; Lambertson, C. Assessing worker and environmental chemical exposure risks at an e-waste recycling and disposal site in Accra, Ghana. Journal of Health and Pollution 2011, 1(1), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, V.; Baldé, C. P.; Kuehr, R.; Bel, G. The global e-waste monitor 2020: Quantities, flows and the circular economy potential; United Nations University, 2020; Available online: https://ewastemonitor.info/.

- Grandjean, P.; Bellanger, M. Calculation of the disease burden associated with environmental chemical exposures: Application of toxicological information in health economic estimation. Environment International 99 2017, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandjean, P.; Landrigan, P. J. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. The Lancet Neurology 2014, 13(3), 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, K.; Goldizen, F. C.; Sly, P. D.; Brune, M. N.; Neira, M.; van den Berg, M.; Norman, R. E. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: A systematic review. The Lancet Global Health 2013, 1(6), e350–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrigan, P. J.; Fuller, R.; Acosta, N. J. R.; Adeyi, O.; Arnold, R.; Baldé, A. B.; Bertollini, R.; Bose-O’Reilly, S.; Boufford, J. I.; Breysse, P. N.; Chiles, T.; Mahidol, C.; Coll-Seck, A. M.; Cropper, M. L.; Fobil, J.; Fuster, V.; Greenstone, M.; Haines, A.; Hanrahan, D.; Zhong, M. The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. The Lancet 2018, 391(10119), 462–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanphear, B. P.; Hornung, R.; Khoury, J.; Yolton, K.; Baghurst, P.; Bellinger, D. C.; Canfield, R. L.; Dietrich, K. N.; Bornschein, R.; Greene, T.; Rothenberg, S. J.; Needleman, H. L.; Schnaas, L.; Wasserman, G.; Graziano, J.; Roberts, R. Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: An international pooled analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives 2005, 113(7), 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeng-Gyasi, E.; Armijos, R. X.; Weigel, M. M.; Filippelli, G.; Sayegh, M. A. Hepatobiliary-related outcomes in children exposed to heavy metals from artisanal gold mining and e-waste recycling activities. Environment International 129 2019, 104417. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Exposure to lead: A major public health concern; WHO Press, 2010; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CED-PHE-EPE-19.12.15.

- World Health Organization. Lead poisoning and health. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health.

- World Health Organization. Children and digital dumpsites: E-waste exposure and child health; WHO Press, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240023901.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).