Submitted:

18 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

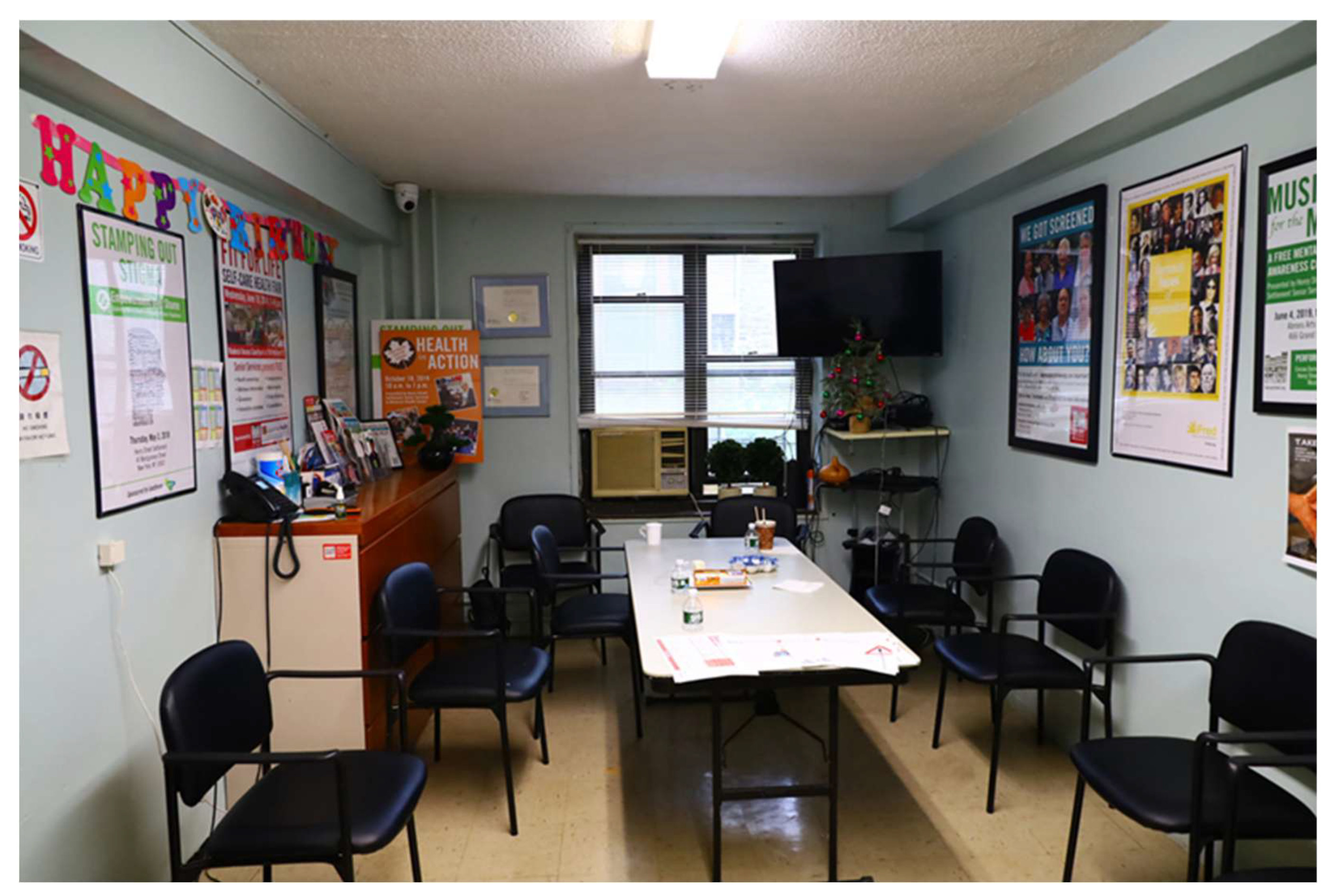

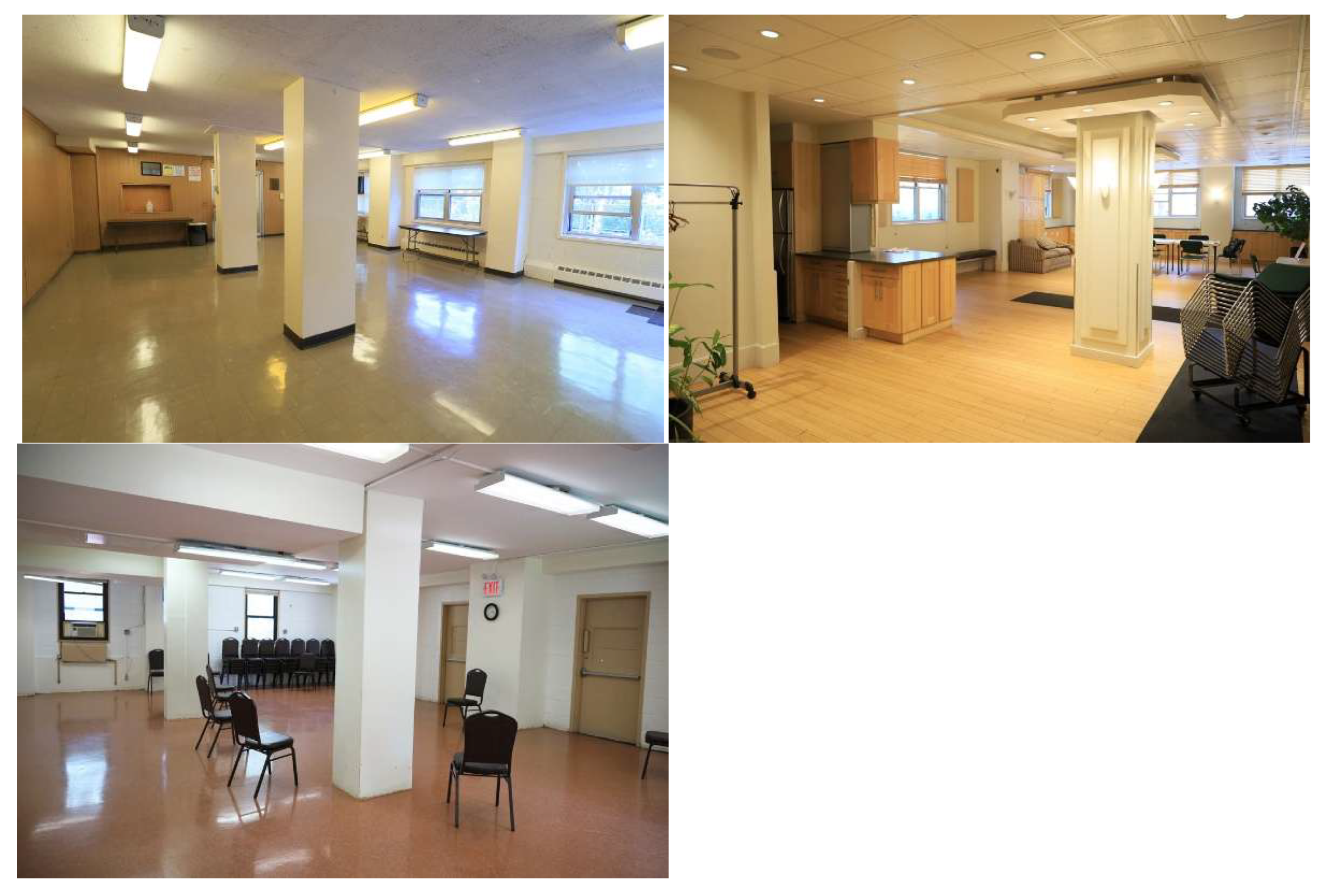

3.1. Architectural Inspection

3.2. Residents Survey

3.2.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2.2. Regression Models: Well-Being Outcomes

3.3. Interviews with the NORC Directors

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of NORC-SSPs

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022; 2022.

- Steels, S. Key characteristics of age-friendly cities and communities: A review. Cities 2015, 47, 45–52.

- World Health Organization. Global age-friendly cities: A guide; Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- American Association of Retired Persons. Aging in place: A State Survey of Livability Policies and Practices; Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Jayantha, W.M.; Qian, Q.K.; Yi, C.O. Applicability of “Aging in Place” in redeveloped public rental housing estates in Hong Kong. Cities 2018, 83, 140–151.

- Vasunilashorn, S.; Steinman, B.A.; Liebig, P.S.; Pynoos, J. Aging in Place: Evolution of a Research Topic Whose Time Has Come. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 1–6.

- Burton, E.J.; Mitchell, L.; Stride, C.B. Good places for ageing in place: Development of objective built environment measures for investigating links with older people’s wellbeing. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 839.

- Greenfield, E.A.; Oberlink, M.; Scharlach, A.E.; Neal, M.B.; Stafford, P.B. Age-friendly community initiatives: Conceptual issues and key questions. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 191–198.

- Scharlach, A.E.; Lehning, A.J. Ageing-friendly communities and social inclusion in the United States of America. Ageing Soc. 2013, 33, 110–136.

- García Lantarón, H. Vivienda para un envejecimiento activo: El paradigma danés. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 2015.

- Greenfield, E.A.; Scharlach, A.; Lehning, A.J.; Davitt, J.K. A conceptual framework for examining the promise of the NORC program and Village models to promote aging in place. J. Aging Stud. 2012, 26, 273–284.

- NYC Department for the Aging. Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/dfta/services/naturally-occurring-retirement-communities.page (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- NYS Office for the Aging. Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC). Available online: https://aging.ny.gov/naturally-occurring-retirement-community-norc (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Vladeck, F. Good place to grow old: New York’s model for NORC supportive service programs; New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- García Sánchez, A.; Torres Barchino, A. The Influence of the Built Environment on the Quality of Life of Urban Older Adults Aging in Place: A Scoping Review. J. Aging Environ. 2024, 38, 398–424.

- Zhang, F.; Li, D.; Ahrentzen, S.; Feng, H. Exploring the inner relationship among neighborhood environmental factors affecting quality of life of older adults based on SLR–ISM method. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 215–242.

- Herbers, D.J.; Mulder, C.H. Housing and subjective well-being of older adults in Europe. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2017, 32, 533–558.

- Prosper, V. Aging in place in multifamily housing. Cityscape 2004, 7, 81–106.

- Clarke, P.; Gallagher, N.A. Optimizing mobility in later life: The role of the urban built environment for older adults aging in place. J. Urban Heal. 2013, 90, 997–1009.

- Fernández-Carro, C.; Módenes, J.A.J.A.; Spijker, J. Living conditions as predictor of elderly residential satisfaction. A cross-European view by poverty status. Eur. J. Ageing 2015, 12, 187–202.

- Greenfield, E.A. Healthy aging and age-friendly community initiatives. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2015, 25, 43–46.

- Temelová, J.; Slezáková, A. The changing environment and neighbourhood satisfaction in socialist high-rise panel housing estates: The time-comparative perceptions of elderly residents in Prague. Cities 2014, 37, 82–91.

- Guo, K.L.; Castillo, R.J. The U.S. long term care system: development and expansion of naturally occurring retirement communities as an innovative model for aging in place. Ageing Int. 2012, 37, 210–227.

- Vladeck, F.; Altman, A. The Future of the NORC-Supportive Service Program Model. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2015, 25, 20–22.

- Chao, C. Planning for the Unplanned Aging Community. Columbia University, 2016.

- Pinckney, S.D.; Bishop, M.L. Design for the Aging in Place Community: Re-Imagining the Older New York City Apartment Dwelling in Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities. State University of New York, 2017.

- Zlotnick, M. Adapting for the senior population: An Examination of the Naturally Occurring Retirement Community [NORC] A Case Study. State University of New York, 2013.

- Garin, N. et al. Built environment and elderly population health: A comprehensive literature review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Heal. 2014, 10, 103–115.

- Serrano-Jiménez, A.; Lima, M.L.; Molina-Huelva, M.; Barrios-Padura, Á. Promoting urban regeneration and aging in place: APRAM – An interdisciplinary method to support decision-making in building renovation. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 47, 101505.

- Oswald, F.; Jopp, D.; Rott, C.; Wahl, H.W. Is aging in place a resource for or risk to life satisfaction?. Gerontologist 2011, 51, 238–250.

- Wang, Z.; Shepley, M.M.C. Can aging-in-place be promoted by the built environment near home for physical activity: A case study of non-Hispanic White elderly in Texas. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 749–766.

- Fernández-Mayoralas Fernández, G.; Rojo Pérez, F.; Pozo Rivera, E.P. Residential environment of the elderly people living in Madrid | El entorno residencial de los mayores en Madrid. Estud. Geogr. 2002, 63, 619–654.

- Welti, L.M. et al. Patterns of home environmental modification use and functional health: The women’s health initiative. Journals Gerontol. Ser. A 2020, 75, 2119–2124.

- NYC Department for the Aging. DFTA Senior Services Results Page: NORCs. Available online: https://a125-egovt.nyc.gov/AgingService/ProgramService/searchResult?programType=NORC (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Choi, Y.J. Age-friendly features in home and community and the self-reported health and functional limitation of older adults: The role of supportive environments. J. Urban Heal. 2020, 97, 471–485.

- Mercader-Moyano, P.; Flores-García, M.; Serrano-Jiménez, A. Housing and neighbourhood diagnosis for ageing in place: Multidimensional Assessment System of the Built Environment (MASBE). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62,.

- Bloom, N.D.; Lasner, M.G. Affordable housing in New York: the people, places, and policies that transformed a city; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA and Oxford, UK, 2016.

- NYPD. City Wide Crime Stats. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/site/nypd/stats/crime-statistics/citywide-crime-stats.page (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- NYCHA. Resident Data Book Summary 2022; 2022.

- Jian, I.Y.; Mo, K.H.; Ng, E.; Chen, W.; Jim, C.Y.; Woo, J. Age-friendly spatial design for residential neighbourhoods in a compact city: Participatory planning with older adults and stakeholders. Habitat Int. 2025, 161, 103428.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2018-2022 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/narrative-profiles/2022/report.php?geotype=place&state=36&place=51000 (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Greenfield, E.A. An overview of Naturally Occurring Retirement Community Supportive Services Programs in New Jersey; 2011.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Dakheel-Ali, M.; Frank, J.K. The impact of a naturally occurring retirement communities service program in Maryland, USA. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 210–220.

- Enguidanos, S.; Pynoos, J.; Siciliano, M.; Diepenbrock, L.; Alexman, S. Integrating community services within a NORC: The Park La Brea experience. Cityscape A J. Policy Dev. Res. 2010, 12, 29–45.

| Name | District | Neighborhood | Housing tenure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Alliance Co op Village NORC | Manhattan | Lower East Side | Cooperative housing |

| Hanac Queensview NORC | Queens | Astoria | Cooperative housing |

| Hanac Ravenswood NORC* | Queens | Astoria | Public housing |

| Queensbridge NNORC | Queens | Long Island City | Public housing |

| Jasa Coney Island Active Aging NORC | Brooklyn | Coney Island | Public housing |

| Jasa Trumps United NORC | Brooklyn | Coney Island | Cooperative housing |

| Warbasse Cares NORC | Brooklyn | Coney Island | Cooperative housing |

| Hamilton Madison Knickerbocker NORC | Manhattan | Two Bridges | Subsidized rental |

| Hamilton Madison Alfred Smith Houses NORC | Manhattan | Two Bridges | Public housing |

| Confucious Plaza NORC | Manhattan | Two Bridges | Cooperative housing |

| Isabella Geriatric River Terrace NORC | Manhattan | Washington Heights | Cooperative housing |

| Lincoln Square NORC | Manhattan | Upper West Side | Cooperative and public housing |

| Jasa Bushwick Hyland NORC | Brooklyn | Bushwick | Public housing |

| Lindsay Park NORC | Brooklyn | Williamsburg | Cooperative housing |

| Penn South NORC | Manhattan | Chelsea | Cooperative housing |

| Amalgamated Pk Reservoir NORC | Bronx | Van Cortland Park | Cooperative housing |

| Selfhelp Big Six NORC | Queens | Woodside | Cooperative housing |

| Stanley M. Isaacs Neighborhood Center NORC | Manhattan | Yorkville | Public housing |

| Name | District/county | Neighborhood | Housing tenure | No. of surveys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morningside MRHS NORC | Manhattan | Morningside Heights | Cooperative housing | 2 |

| Henry Street Settlement NORC/Vladeck Cares | Manhattan | Lower East Side | Public housing | 37 |

| Lincoln House Outreach NORC | Manhattan | Upper West Side | Cooperative housing | 8 |

| Masaryk Tower NORC | Manhattan | Lower East Side | Cooperative housing | 3 |

| Isabella Geriatric Ft George Vistas NORC | Manhattan | Washington Heights | Cooperative housing | 7 |

| Vision Urbana NORC | Manhattan | Lower East Side | Cooperative housing* | 2 |

| Hands on Huntington NNORC | Suffolk (Long Island) | Huntington | Subsidized rental | 13 |

| Baruch Elders Service Team (B.E.S.T.) NORC | Manhattan | Lower East Side | Public housing | 79 |

| TOTAL | 151 |

| Variables | Description & Coding |

| Location variables | |

| Bernard M. Baruch Houses | Attends Bernard M. Baruch Houses NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. (Ommitted Category) |

| Hands on Huntington NNORC | Attends Hands on Huntington NNORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Henry Street Settlement NORC | Attends Henry Street Settlement NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Ft George Vistas | Attends Ft George Vistas NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Lincoln House Outreach | Attends Lincoln House Outreach NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Masaryk Tower | Attends Masaryk Tower NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Morningside MRHS | Attends Morningside MRHS NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Vision Urbana NORC | Attends Vision Urbana NORC. Yes = 1, else =0. |

| Rental | Type of property. Rental = 1; Public housing =1; Co-op = 0. |

| Urban | Location of the NORC. Manhattan = 1, Greenlawn (Long Island) = 0. |

| Demographic variables | |

| Age | Respondent’s age. 60-65 = 1; 66-72 = 2; 73-80 = 3; 81-85 = 4; 86+ = 5. |

| Female | Respondent’s gender. Female = 1, Male = 0. |

| Education | Respondent’s highest education level. Grade school or less = 1; High school = 2; College = 3; Graduate = 4; Post-graduate = 5. |

| Married | Respondent’s marital status. Married = 1, else = 0. |

| Income | Respondent’s total annual household income. $20,000 or less = 1; $20,000-30,000 = 2; $30,000-40,000 = 3; $40,000-50,000 = 4; $50,000 or more = 5. |

| Household | # of people living in the household. I live alone = 1; 1 person = 2; 2 people = 3; 3 people = 4. |

| Employed | Respondent’s occupation. Employed part-time = 1, else = 0. |

| Health and well-being variables | |

| Self-rated health | Self-reported health ranging from 1–5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Self-rated quality of life | Self-reported quality of life ranging from 1–5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Health changes | Has experienced health changes since moving there. Yes = 1, No = 0. |

| Social Integration variables | |

| Lenght of residence | 0-5 years = 1; 6-10 years = 2; 11-15 years = 3; 16-20 years = 4; 20+ years = 5. |

| Visitors | Frequency of having visitors. Never = 1; Once or twice a month = 2; Once a week = 3; A few times a week = 4; Daily = 5. |

| Visit friends | Frequency of visiting friends or relatives. Never = 1; Once or twice a month = 2; Once a week = 3; A few times a week = 4; Daily = 5. |

| Social/physical activity | Frequency of exercising or engaging in social activity. Never = 1; Once or twice a month = 2; Once a week = 3; A few times a week = 4; Daily = 5. |

| NORC attendance | Frequency of attending NORC programs. Never = 1; Once or twice a month = 2; Once a week = 3; A few times a week = 4; Daily = 5. |

| Built environment variables | |

| Bedrooms | # of bedrooms in the apartment ranging from 0-4. |

| Physical Condition (Apartment) | Self-rated physical condition of the apartment ranging from 1–5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Aesthetics (Apartment) | Self-rated aesthetics of the apartment (design, color, light) ranging from 1-5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Environmental Comfort (Apartment) |

Self-rated environmental condition (temperature, noise, air quality) ranging from 1-5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Mobility (Apartment) | Can move around the apartment and perform daily tasks with ease. Ranges from 1-5, with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. |

| Modifications (Apartment) | Has modified or retrofit apartment. Yes = 1, No = 0. |

| Mobility (Complex) | Can move around the building complex with ease. Ranges from 1–5, with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. |

| Safety (Complex) | Feels safe at the building complex. Ranges from 1–5, with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. |

| Mobility (Neighborhood) | Can move around the neighborhood with ease. Ranges from 1–5, with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. |

| Safety (Neighborhood) | Feels safe at the neighborhood. Ranges from 1–5, with 1 = disagree and 5 = agree. |

| Environmental quality (Neighborhood) |

Self-rated environmental quality at the neighborhood (noise, pollution) ranging from 1–5, with 1 = poor and 5 = excellent. |

| Variables | Values / Scales | Total |

| Demographic | Mean (SD)/% | |

| NORC Housing tenure |

Bernard M. Baruch Houses Henry Street Settlement NORC Hands on Huntington NNORC Ft George Vistas Lincoln House Outreach Masaryk Tower Morningside MRHS Vision Urbana NORC Co-op |

52.3 24.5 8.6 4.6 5.3 2.0 1.3 1.3 14.6 |

| Rental | 85.4 | |

| Location | Manhattan | 92.1 |

| Greenlawn (Long Island) | 7.9 | |

| Age group | 60-65 | 3.4 |

| 66-72 | 12.9 | |

| 73-80 | 38.1 | |

| 81-85 | 23.1 | |

| 86+ | 22.4 | |

| Gender | Male | 19.7 |

| Female | 80.3 | |

| Education | Grade school or less | 43.9 |

| High school | 35.1 | |

| College | 8.1 | |

| Graduate | 4.7 | |

| Post-graduate | 8.1 | |

| Marital status | Single | 15.6 |

| Married | 34.7 | |

| Divorced | 12.2 | |

| Separated | 4.1 | |

| Widowed | 33.3 | |

| Annual income | <$20,000 | 81.1 |

| $20,000-30,000 | 8.4 | |

| $30,000-40,000 | 2.1 | |

| $40,000-50,000 | 1.4 | |

| >$50,000 | 7.0 | |

| Household composition | Live alone | 58.4 |

| Live with 1 person | 30.9 | |

| Live with 2 people | 9.4 | |

| Live with 3 people | 1.3 | |

| Occupation | Employed part-time | 0.7 |

| Not employed | 0.7 | |

| Student | 2.0 | |

| Retired | 96.6 | |

| Health and well-being | ||

| Self-rated health | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.25 (0.89) |

| Self-rated quality of life | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.54 (0.81) |

| Health changes | Yes | 72.8 |

| No | 27.2 | |

| Social integration | ||

| Length of residence | 0-5 | 13.3 |

| 6-10 | 12.7 | |

| 11-15 | 14.7 | |

| 16-20 | 22.0 | |

| 20+ | 37.3 | |

| Importance of aging in place | Not at all | 1.3 |

| Somewhat | 12.8 | |

| Very | 85.2 | |

| Not Sure | 0.7 | |

| Frequency of visitors | [1 = Never, 5 = Daily] | 2.31 (0.97) |

| Frequency of visiting friends/relatives | [1 = Never, 5 = Daily] | 2.09 (1.01) |

| Frequency of exercise or social activity | [1 = Never, 5 = Daily] | 3.17 (1.29) |

| Frequency of NORC attendance | [1 = Never, 5 = Daily] | 2.78 (1.01) |

| How much NORC helps age in place | [1 = Nothing, 5 = Very much] | 4.14 (0.73) |

| Built environment | ||

| Apartment | ||

| Bedrooms | 1.30 (0.69) | |

| Physical condition | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.52 (1.03) |

| Aesthetics | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.61 (0.83) |

| Environmental comfort | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.33 (0.95) |

| Mobility | [1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree] | 3.76 (0.91) |

| Modifications | Yes | 26.5 |

| No | 73.5 | |

| Building complex | ||

| Mobility | [1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree] | 3.70 (1.03) |

| Safety | [1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree] | 3.49 (1.13) |

| Neighborhood | ||

| Mobility | [1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree] | 3.64 (0.90) |

| Safety | [1 = Disagree, 5 = Agree] | 3.21 (1.12) |

| Environmental quality | [1 = Poor, 5 = Excellent] | 3.19 (0.89) |

| Model 1: Self-rated Health | Model 2: Self-rated Quality of Life | |||

| Variable | Coef. | p-value | Coef. | p-value |

| Constant | -0.234 | 0.744 | 0.579 | 0.314 |

| Bernard M. Baruch Houses | (omitted variable) | |||

| Hands on Huntington NNORC | -0.430 | 0.184 | 0.172 | 0.509 |

| Henry Street Settlement NORC | -0.220 | 0.215 | 0.138 | 0.332 |

| Ft George Vistas | -0.773 | 0.066* | 0.830 | 0.016** |

| Lincoln House Outreach | -0.023 | 0.961 | 0.583 | 0.118 |

| Masaryk Tower | -0.227 | 0.676 | 0.181 | 0.677 |

| Morningside MRHS | -0.246 | 0.704 | 0.582 | 0.261 |

| Vision Urbana NORC | -0.089 | 0.883 | 0.503 | 0.296 |

| Age | -0.042 | 0.512 | 0.114 | 0.030** |

| Female | 0.305 | 0.071* | 0.030 | 0.826 |

| Education | 0.085 | 0.262 | -0.083 | 0.177 |

| Married | 0.133 | 0.414 | 0.116 | 0.375 |

| Household | 0.047 | 0.667 | -0.042 | 0.633 |

| Employed | 0.824 | 0.247 | 0.642 | 0.261 |

| Self-rated health | N/A | N/A | 0.370 | 0.000** |

| Health_changes | -0.377 | 0.0091** | 0.039 | 0.741 |

| Length of residence | 0.084 | 0.1083 | -0.039 | 0.361 |

| Visit friends | 0.068 | 0.462 | 0.134 | 0.073* |

| Social/physical activity | 0.210 | 0.002** | 0.162 | 0.004** |

| NORC attendance | 0.014 | 0.844 | -0.012 | 0.838 |

| Bedrooms | -0.087 | 0.437 | -0.084 | 0.347 |

| Physical condition_apartment | 0.178 | 0.043** | 0.004 | 0.954 |

| Environment comfort_apartment | -0.012 | 0.895 | -0.113 | 0.111 |

| Aesthetics_apartment | -0.088 | 0.404 | 0.002 | 0.980 |

| Mobility_apartment | 0.156 | 0.098* | 0.041 | 0.587 |

| Apartment_modifications | -0.192 | 0.245 | 0.072 | 0.586 |

| Mobility_building | 0.138 | 0.147 | 0.136 | 0.079* |

| Safety_building | 0.075 | 0.399 | 0.035 | 0.621 |

| Mobility_neighborhood | 0.133 | 0.147 | -0.034 | 0.646 |

| Environment qual_neighborhood | 0.126 | 0.226 | 0.163 | 0.052* |

| R-square | 0.5569 | 0.6595 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).