1. Introduction

Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) and solid oxide electrolysis cells (SOECs) are emerging energy conversion technologies that can support the energy transition. Their use can improve the efficiency of existing energy conversion concepts, like in the case of an SOFC used for cogeneration applications, or prompt the development of new concepts, like multi-energy systems based on reversible solid oxide cells (rSOCs) [

1], or hybrid power generation systems integrating an SOFC with gas or steam cycles [

2]. Modern SOCs operate at a high temperature between 600 °C-800 °C using in most cases a solid yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) electrolyte. On the one hand, the high temperatures bring several advantages compared to similar electrochemical devices based on polymeric or alkaline electrolytes, including higher efficiency, the possibility of thermal integration at system level, fuel flexibility, and absence of expensive catalysts. On the other hand, the main drawbacks include a faster degradation of the cell main components and the need to carefully manage internal thermal gradients.

Using accurate models to predict the performance of SOFC (or SOEC) is a crucial aspect for the development of energy systems based on this technology. In general, a stationary SOFC model includes mass and energy balances to find the internal gas composition and temperature profiles, and an electro-chemical model to calculate the local rate of electrochemical and chemical reactions. The model dimensionality and complexity can vary substantially, including 1D approaches developed along the main direction of the gas flows [

3], 1D+1D or 2D models with a refined description of the processes occurring within the electrodes [

4] and at the cell layer boundaries, and 3D models of the solid oxide cell (or stack) using commercial software like COMSOL [

5] and CFD (computational fluid-dynamics) approach. The review work of Wu et al. [

6] provides an in-depth description of the available SOFC models, highlighting strengths, weaknesses, and field of application for each of them. In particular, 1D models can be more easily integrated into wider system simulations due to the significant computational burden of 2D and 3D models, allowing the system optimization while retaining a good description of physical processes occurring within the stack. Two- and three-dimensional models provide additional insights on the stack internal operating conditions and can improve the performance estimation, especially at high current density [

7].

This work presents an updated version of a 1D, co-flow, finite-volume model for the simulation of planar SOFCs, that has been already validated and used in several works [

3,

8]. Differently from previous versions, the model is developed to allow running within Aspen Plus

® for wider system and process simulations; the Aspen environment provides built-in functions for the calculation of physical and thermodynamic properties of gases and facilitates the model integration.

The model developed is calibrated and validated using experimental polarization curves of an SOFC, covering a wide range of operating conditions in terms of H

2 and H

2O molar fraction in the fuel, temperature, and fuel utilization factor (exceeding 90%), which is not common for relatively simple 1D models. The experimental data are reported in ref. [

4], which also includes a numerical investigation using a 1D+1D model integrating the dusty gas model (DGM) for species diffusion in the electrode, and a distributed electrochemical model applied throughout the electrode thickness. One of the aims of this work is to demonstrate that the same set of data can be described by a simpler 1D model over a wide range of operating conditions, drastically reducing complexity and computational time, facilitating the grid convergence, while retaining a good accuracy.

2. Model Description

The model developed is designed for the simulation of standard solid oxide cells using Y-doped zirconia as electrolyte. The electrochemical reactions (1) and (2), representing the hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) and the oxygen reduction reaction (ORR), occur at the fuel and air electrode, respectively. In fuel cell mode, H

2 is oxidized to H

2O, consuming an oxygen ion in the electrolyte and producing two electrons in the electronic-conducting phase (e.g., nickel). Electrons flow through an external resistance towards the positive electrode (air electrode), where they combine with oxygen to produce an oxygen ion in the electrolyte. The HOR and the ORR proceed forward and backward in fuel cell and electrolysis mode, respectively.

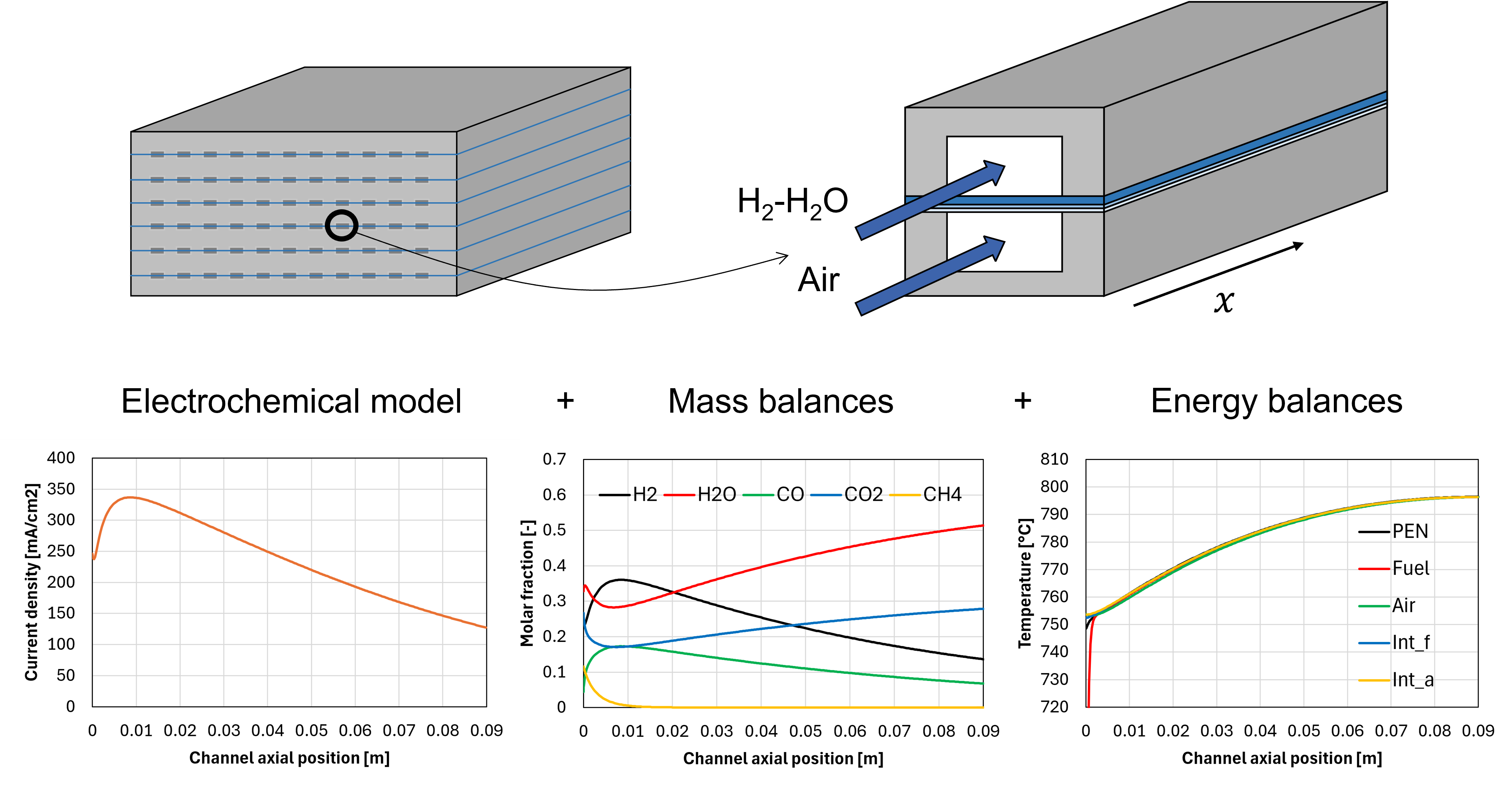

Figure 1 (left) shows a generic solid oxide cell stack made of multiple planar cells stacked on top of each other, each cell containing several gas channels as the one shown in the right-hand side of

Figure 1. The model developed in this work considers a single channel as geometric domain, assuming that the whole stack (or cell) can be represented by a number of identical channels, which significantly limits the model complexity. The finite-volume model developed is one-dimensional in the direction of the channel; it assumes steady-state operation, co-flow arrangement, and it can be used to model both fuel cell and electrolyzer modes. The model is implemented in Aspen Plus

® environment, which allows exploiting a built-in equations solver and accurate datasets for the calculation of thermodynamic and physical properties of gas mixtures.

The model inputs are the channel geometry, the conditions of the inlet streams (temperature, composition, pressure, and mass flow rate), several parameters required to model the physical processes, and the cell voltage, which is assumed to be constant throughout the channel (electrode equipotential assumption). The main outputs of the 1D model are the distribution along the axial direction of:

The temperature of the interconnect at the fuel side and air side ( and );

The current density () and the electrochemical overpotentials ().

Figure 2 shows the main dimensions defining the channel geometry, which also allow to define the relevant geometrical parameters shown in

Table 1.

The finite-volume solution algorithm includes the division of the channel in

N small pieces as the one shown in

Figure 3 (left), which will be called control volume (CV). Assuming that the cell voltage is fixed throughout the channel, the electrochemical model allows to calculate the local current density

, which is equal to the small (but finite) current (

) flowing through the interconnects of the CV divided by the active area contained in it (

), as shown in Eq. (3).

The electrochemical model developed is zero-dimensional, meaning that electrochemical reactions are assumed to only occur at the interface between the electrode and the bulk of the electrolyte. Coherently with the use YSZ as electrolyte, short-circuit electronic currents in the electrolyte are neglected, hence the current collected by the interconnects is equal to the ionic current flowing in the electrolyte.

As shown in

Figure 3 (right), each CV is further divided into 5 sub-volumes enclosing the fuel and air channels, the interconnects, and the PEN structure. Mass and energy balances are solved for each of these 5 x

N sub-volumes to find the temperature and gas composition along the channel. A uniform temperature is defined for the solid parts (interconnects and PEN sub-volumes) of each CV, resulting in 3 x

N unknown temperatures. The fuel and air temperatures at the outlet interface of each CV are also unknown, resulting in 5 x

N unknown temperatures in total, which is equal to the number of energy balance equations.

Axial heat conduction in the direction is considered for the PEN and the interconnects, while it is neglected for gas streams due to the low thermal conductivity of the gases. In the direction, only the convective heat exchange between gases and interconnects is considered (with exchange area per unit length equal to ). The heat exchange in the direction includes the convective heat transfer between gases and solid parts, the conductive heat transfer between PEN and interconnects, and the heat loss which is assumed to be uniformly distributed on the external interconnect surfaces. The radiative heat exchange between PEN and interconnects is neglected since the temperature of the solid parts are always found to be very similar in the and directions even when radiative heat exchange is not considered, while the view factors are very small in the direction.

The main equation used for the calculation of the local current density is the voltage balance shown in Eq. (4). The cell voltage (

) is fixed (if the total current is fixed, instead of the voltage, the same model can be run iteratively to find the voltage which matches the required current), and

is the ideal maximum (minimum) cell voltage in fuel cell (electrolysis) mode. The term

depends on temperature, and a simple correlation can be derived by fitting thermodynamic data [

3]. The partial pressures of hydrogen and steam (

and

used in Equation (5) are those found locally in the fuel channel; similarly, the local oxygen partial pressure in the air channel (

) is used. The overpotentials

shift the cell voltage from the ideal value, decreasing its performance. In the model developed, both the overpotentials and the current density are positive in fuel cell mode and negative in electrolysis mode. All the overpotentials depend on the current density, and Eq. (4) is used to implicitly calculate

.

Equation (6) is used to calculate

, which accounts for the fact that the measured open-circuit voltage (OCV) is typically slightly lower compared to the ideal value calculated with Equation (5), even if the external current is null [

4,

9]. This might be due to small gas leaks or a short-circuit electronic current within the electrolyte. In fuel cell (or electrolysis) mode the maximum current density

is calculated assuming that all the equivalent hydrogen (or steam) is consumed, generating a corresponding faradaic current. Therefore, the leakage loss is important near the OCV and tends to zero when the current density is large (in absolute value).

The concentration overpotential, which is calculated with Eq. (7), accounts for the fact that the ideal voltage should be calculated using the species partial pressures in the proximity of the reaction site (i.e.,

,

, and

), here assumed located at the electrode-electrolyte interface. Assuming that the total pressure is constant throughout the electrodes, the partial pressures in Eq. (7) can be replaced by molar fractions.

The molar fractions of H

2, H

2O, and O

2 at the electrode-electrolyte interfaces are calculated using Eqs. (8), (9), and (10) [

10]. The coefficient

is included to account for the fact that the reference surface for the diffusion process is lower than the active area.

The binary diffusion coefficients

are calculated according to the Fuller method, which is valid for pressures below 35 bar [

11]. The effective molecular diffusion coefficients in the gas mixture are then calculated with Eq. (11), which assumes that the species

diffuses in subsequent gas layers, where each layer

has a thickness proportional to

and a binary diffusion coefficient

. The effective Knudsen diffusion coefficient is calculated with Eq. (12), and the overall diffusion coefficient in the porous electrode

is calculated using Eq. (13), which assumes that molecular and Knudsen diffusion occur in series. The parameter

is the average pore radius, and

is the molar mass of species

.

The ohmic loss is calculated with Eq. (14), where the main contribution is due to the oxygen ion conductivity (

) along the electrolyte thickness (

), and

is a calibration parameter that can be used to fit the data, representing an additional electric contact resistance which includes the effect of the interconnects (material electric resistance and contact resistance) and other contributions that are not (or cannot be) explicitly considered in the model.

The activation overpotentials in the fuel electrode (

) and air electrode (

) are calculated using Butler-Volmer equations (16) and (18), and their sum is equal to the overall activation overpotential (

). The form of the Butler-Volmer equations is taken from [

4], and both

and

are referred to the active area of the cell.

The mass balance equation for each species can be written in differential form as shown in Equation (20), accounting for possible chemical or electrochemical reactions and the stoichiometric coefficient of species in reaction . The reaction rate (mol s-1 m-2) is specific to the active area of the cell. The sum of the HOR and the ORR can be considered as a single overall reaction whose reaction rate is calculated as in Eq. (21), with stoichiometric coefficients equal to -1, 1, and -0.5 for H2, H2O, and O2, respectively.

Concerning water gas shift (WGS) and methane steam reforming (MSR) reactions, a global reaction approach described by Eqs. (22) and (23) is used. In this work, the WGS reaction is assumed to be equilibrated throughout the channel. In particular, the forward kinetic constant is fixed to an arbitrarily large value, the partial pressures in Eq. (22) are those at the outlet of each CV, and is calculated using the fuel temperature at the outlet of each CV. In this way, the species partial pressures are guaranteed to satisfy the WGS equilibrium condition throughout the channel. Assuming that the inlet fuel composition is already in equilibrium, which is typically the case for pre-reformed gas mixtures, using the fuel temperature to calculate also allows to avoid a step-wise change in composition that would arise in case the PEN temperature was used.

Regarding the MSR reaction, the kinetic model reported by Timmermann et al. is selected [

12]. This model is valid in the range 600 °C-750 °C, which is in line with the operating temperature of modern SOFCs; the temperature at cell outlet might be even larger, but methane is typically consumed near the inlet section of the cell. The pre-exponential factor appearing in the kinetic constant

, which is equal to 1483 mol s

-1 m

-2 in the original reference, is scaled by a factor 1.73 to refer to the active area instead of the surface touched by the gas. The scaling factor is derived from the channel width (

) and interconnect thickness (

) stated in ref. [

12], equal to 1.5 mm and 0.55 mm, respectively. Note that both

and

are calculated using the local PEN temperature.

Equations (24)-(28) represent the energy balances for the fuel channel, air channel, PEN assembly, fuel-side interconnect, and air-side interconnect, respectively. The energy exchanges between gas and solid parts are further detailed in

Table 2. The left-hand side of Eqs. (24) and (25) represents the variation of enthalpy flow along the axial coordinate, where

and

are the overall molar flow rate at the fuel and air side, respectively, and the specific enthalpy, which is calculated using Peng-Robinson correlations imported from Aspen Plus

®, is a function of the local gas composition and temperature. The left-hand side of Eqs. (26), (27), and (28) accounts for the axial conduction of the solid parts. A heat loss term

, expressed in W m

-2, is also included in Eqs. (28) and (29), and it is specific to the interconnects surfaces facing adjacent cells. All other external surfaces of the channel are assumed to be adiabatic.

The local convective heat transfer coefficients (

) for the fuel and air streams are calculated from the local gas thermal conductivity and the hydraulic diameter of the channels, and assuming constant Nusselt numbers. The PEN thermal conductivity is calculated as shown in Eq. (30).