1. Introduction

Despite continuous advances in surgical techniques and rehabilitation protocols, a substantial proportion of athletes do not achieve full functional recovery [

2]. In particular, persistent deficits in quadriceps and hamstring strength are frequently reported at six months after surgery, a time point commonly used for return-to-sport (RTS) decision-making [

1,

2]. Isokinetic testing represents one of the most reliable and objective methods to assess knee extensor and flexor strength after ACLR [

1,

2]. Previous studies have consistently shown residual inter-limb asymmetries, especially in quadriceps strength and activation, even when athletes meet traditional time-based RTS criteria [

1,

2,

3]. These deficits may compromise neuromuscular control, joint loading capacity, and performance during high-demand sports such as soccer [

3].

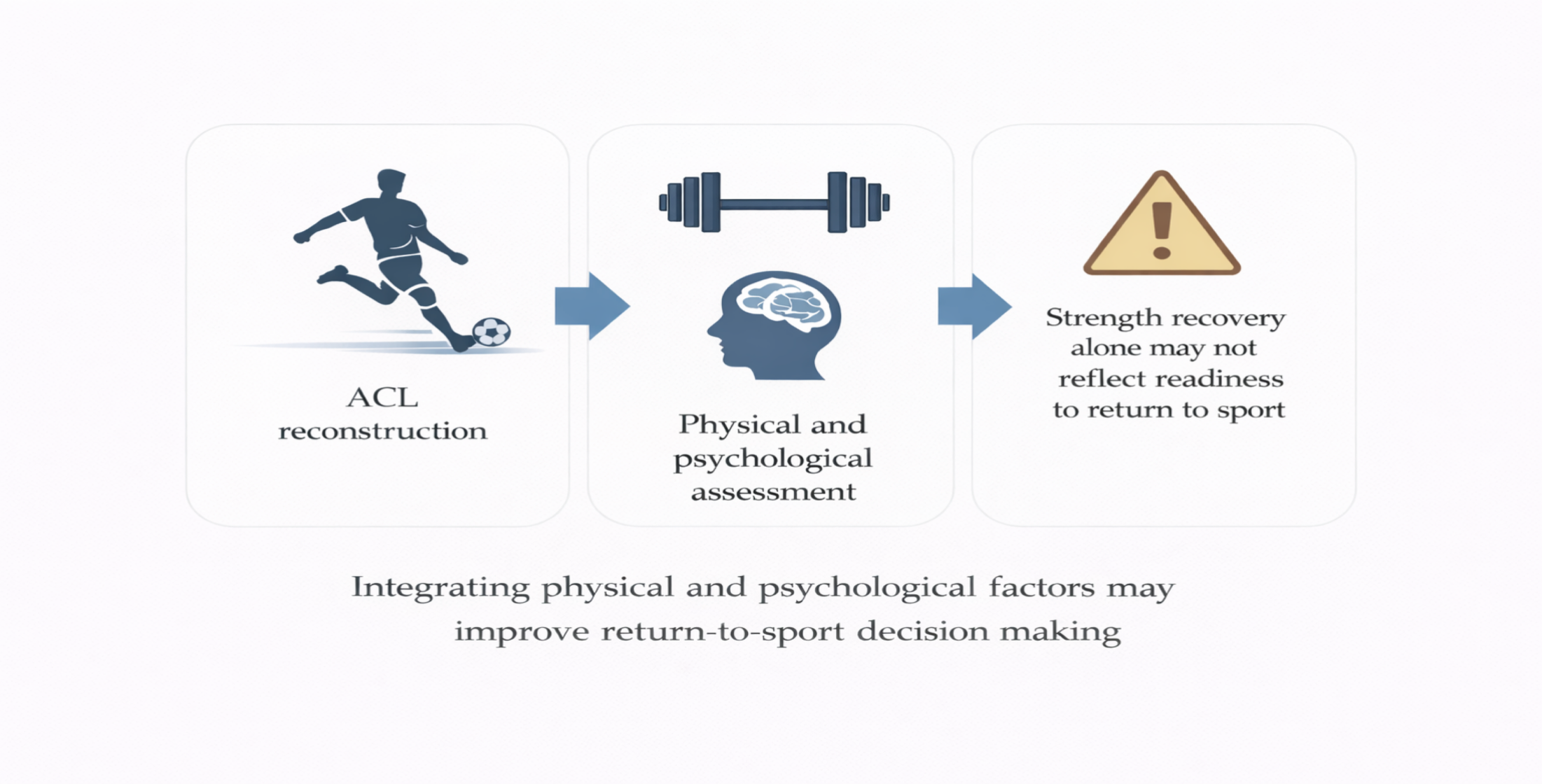

In parallel with physical impairments, psychological factors have emerged as critical determinants of RTS outcomes. Fear of re-injury, loss of confidence, and kinesiophobia are commonly reported after ACLR and may persist long after the athlete has returned to competition [

4]. Importantly, psychological readiness does not necessarily parallel physical recovery [

4,

5], and psychosocial interventions may reduce kinesiophobia, although higher-quality evidence is still needed [

6]. RTS decisions are still frequently based on isolated physical parameters, with limited integration of psychological assessment [

5,

6,

7]. While strength recovery and psychological factors have been investigated separately, fewer studies have explored their long-term interaction. In particular, the relationship between early post-operative isokinetic strength recovery, evolution of limb symmetry, and long-term psychological outcomes remains poorly understood.

Six months after ACL reconstruction represents a critical milestone in the rehabilitation process, as it is frequently used in clinical practice as a reference point for return-to-sport decision-making. However, this time-based milestone does not necessarily reflect complete neuromuscular recovery. Several authors have questioned the validity of using fixed temporal thresholds, highlighting that strength restoration, motor control, and inter-limb symmetry may follow different recovery trajectories.

In particular, improvements in absolute muscle strength may mask persistent deficits in voluntary activation and limb symmetry, especially at the quadriceps level. LSI is widely adopted as a clinical benchmark, yet emerging evidence suggests that LSI values may be influenced not only by recovery of the operated limb but also by compensatory strength gains in the contralateral limb. This phenomenon may lead to an apparent paradox whereby athletes demonstrate higher absolute strength but poorer symmetry, potentially increasing biomechanical and neuromuscular risk during high-demand sport tasks.

In parallel, psychological recovery appears to evolve independently from physical restoration. Fear of re-injury and kinesiophobia may persist even after successful return to sport, suggesting that psychological readiness does not automatically accompany physical clearance. Despite increasing recognition of these factors, the relationship between early post-operative neuromuscular recovery and long-term psychological outcomes remains insufficiently explored, particularly in soccer players exposed to high levels of cutting, pivoting, and contact demands.

Therefore, the primary aim of this retrospective cohort study was to investigate the association between thigh muscle isokinetic strength recovery at six months after ACLR and long-term psychological outcomes related to RTS in competitive male soccer players. Secondary aims were to describe RTS rates, ACL re-injury incidence, limb symmetry indices (LSI) before and after surgery, and kinesiophobia at a mean follow-up of approximately four years after surgery.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was designed as a retrospective cohort study. Isokinetic strength data collected as part of routine clinical assessments between 2020 and 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. Psychological outcomes and RTS-related data were collected through questionnaires administered in 2025. The retrospective design was chosen to analyze isokinetic strength data routinely collected as part of standard clinical assessments in a sports rehabilitation setting. This approach allowed the investigation of long-term psychological outcomes in relation to early post-operative neuromuscular recovery without interfering with clinical decision-making or rehabilitation protocols.

Sixty male soccer players were included in the study (means: age at surgery 21.6 ± 4.5 years, weight 74.65 ± 9.68 kg, height 1.79 ± 0.06 m). Athletes competed at recreational, competitive, and professional levels. Inclusion criteria were: (1) primary unilateral ACL reconstruction, (2) participation in soccer prior to injury, (3) completion of a standardized post-operative rehabilitation protocol, and (4) availability of pre- and post-operative isokinetic testing data. Exclusion criteria included previous ACL injury on either limb, multi-ligament knee injuries, neurological or musculoskeletal disorders affecting lower limb function.

All anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions were performed by the same orthopedic surgeon using a bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. Surgical technique and fixation methods were standardized across all procedures. The use of a single surgeon and a uniform graft choice was intended to minimize procedural variability and to limit potential confounding effects related to different surgical techniques, graft types, or fixation strategies on post-operative neuromuscular and strength recovery.

All athletes followed an identical post-operative rehabilitation program supervised by experienced sports physiotherapists. Rehabilitation was structured according to a phased and criterion-based progression, while maintaining standardized time frames across participants. During the early rehabilitation phase, the primary goals were pain and effusion control, restoration of knee range of motion, and early quadriceps activation, with particular attention to minimizing arthrogenic muscle inhibition. Low-load isometric exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation when indicated, and voluntary activation strategies were implemented to promote quadriceps engagement. The intermediate phase focused on progressive resistance training, with gradual increases in external load and training volume. Both bilateral and unilateral exercises were prescribed, including closed- and open-kinetic-chain movements, with controlled knee extension exercises introduced within safe ranges of motion. Neuromuscular training emphasized balance, proprioception, and movement quality. The late rehabilitation phase incorporated advanced strength training, plyometric exercises, and sport-specific drills, including progressive exposure to running, cutting, jumping, and change-of-direction tasks. Progression through rehabilitation phases was based on predefined clinical criteria, including pain-free execution, adequate range of motion, and tolerance to increasing neuromuscular and mechanical demands.

Isokinetic testing was performed using a Genu 3 isokinetic dynamometer (Easytech, Florence, Italy). Assessments were conducted one week before surgery and six months post-operatively. The six-month post-operative time point was selected as it is commonly used in clinical practice to guide return-to-sport decisions. Concentric quadriceps (Q) and hamstrings (H) strength was evaluated bilaterally at angular velocities of 90°/s (4 maximal repetitions) and 180°/s (20 maximal repetitions). Four maximal repetitions at 90°/s were used to assess peak torque production, while twenty repetitions at 180°/s were performed to evaluate the ability to sustain muscle performance during repeated high-velocity contractions. Peak torque (PT) values were recorded for each muscle group and limb. Limb symmetry index (LSI) was calculated as the ratio between operated and non-operated limb PT values, expressed as a percentage.

At a mean follow-up of approximately four years after RTS, athletes completed a questionnaire investigating RTS status, level of sport participation, ACL re-injuries, and subjective perceptions during sport activity. In addition, kinesiophobia was assessed using the Tampa Scale (TSK): a cut-off value of 37 was used to distinguish between low and high kinesiophobia [

4].

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables and reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or percentages. Paired Student’s t-tests were used to assess pre- to post-operative changes in peak torques and LSI values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using standard statistical software.

3. Results

3.1. Return to Sport and Re-Injury

At long-term follow-up, 91.7% of athletes returned to sport, while the others did not resume sport participation (

Figure 1a). Among those who returned to sport, 81.8% did not sustain any further ACL injuries, while a second ACL injury was reported in 18.2% of the athletes (

Figure 1b).

During sport participation, about half of our athletes reported no fear, whereas the others perceived fear of re-injury or reduced confidence in the operated knee (

Supplementary Figure S1, a). In addition, during soccer activities requiring change of direction, jumping, or physical contact, about two/thirds reported full confidence, while the others reported occasional insecurity and persistent lack of confidence (Supplementary figure S1, b).

3.2. Kinesiophobia

TSK scores ranged from 26 to 52 (mean value:37.5 ± 6.1): based on the cut-off value, 56.7% of athletes were classified as having high kinesiophobia, while 43.4% showed low kinesiophobia (

Figure 2).

3.3. Peak Torque Changes

Absolute quadriceps and hamstring peak torque (PT) values significantly increased from pre- to post-operative assessments both for quadriceps and hamstring PT values at the two angular velocities (

Figure 3). When comparing limbs at the post-surgery assessment, quadriceps PT values remained significantly lower in the operated limb than in the non-operated one at both angular velocities (p<0,01).

3.4. Limb Symmetry Index

In the comparison between pre- and post-surgery strength values, despite the significant improvements in absolute quadriceps strength, limb symmetry index (LSI) analysis revealed an opposite trend: at six months post-surgery, quadriceps LSI significantly decreased, while hamstring LSI remained stable (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

The main finding of this study is that competitive male soccer players exhibit persistent quadriceps inter-limb asymmetry six months after ACL reconstruction, despite significant improvements in absolute strength, high return-to-sport (RTS) rates, and near-complete hamstring recovery. This dissociation between absolute strength gains and limb symmetry highlights a critical limitation of strength-only and time-based RTS criteria [

1,

2]. From a clinical perspective, this dissociation may contribute to a false perception of recovery, whereby improvements in absolute strength lead to premature progression through rehabilitation phases or return-to-sport clearance despite persistent neuromuscular asymmetries. Such discrepancies may not be detected when decision-making relies exclusively on isolated strength values or time-based milestones.

Isokinetic testing demonstrated that quadriceps strength increased from pre- to post-operative assessments in both limbs. However, post-surgery between-limb comparisons revealed that quadriceps strength remained consistently lower in the operated limb compared to the contralateral limb, indicating that the strength recovery was incomplete exclusively on the reconstructed side, as showed by several previous papers [

1,

2,

3]. In parallel, the non-operated limb showed a greater absolute increase in quadriceps strength from pre- to post-operative testing, further contributing to the observed inter-limb asymmetry. These findings indicate that, although overall force-generating capacity improves, the operated limb fails to recover proportionally relative to the uninvolved limb [

3].

Quadriceps asymmetry was more pronounced at lower angular velocity, suggesting impaired maximal force production rather than purely velocity-dependent deficits, a pattern widely reported following ACL injury and reconstruction [

3]. This presentation is consistent with arthrogenic muscle inhibition (AMI), a condition characterized by persistent reductions in voluntary quadriceps activation following knee injury [

7,

8,

9,

10]. In addition, AMI is not solely driven by peripheral joint factors but is strongly influenced by spinal and supra-spinal adaptations, including altered afferent input, reflex inhibition, and reduced cortico-spinal excitability [

9].

Neuro-physiological studies have demonstrated that ACL injury and reconstruction are associated with changes in motor cortex organization, cortico-spinal drive, and sensorimotor integration, which may persist despite intensive rehabilitation and apparent strength recovery [

11]. From this broader brain–knee perspective, ACL injury should be considered a neuro-muscular and neuro-cognitive condition, rather than a purely mechanical lesion [

11,

12]. Contemporary conceptual frameworks emphasize the role of neuro-cognitive and neuro-physiological dysfunctions in ACL injury and advocate for the integration of neuro-cognitive strategies within rehabilitation and RTS testing protocols [

12]. The persistence of kinesiophobia several years after RTS further supports this interpretation [

4]. These neurophysiological alterations may have relevant functional consequences during sport-specific tasks that require rapid decision-making, anticipatory motor control, and efficient integration of sensory information. Altered central motor processing may therefore contribute not only to residual strength asymmetries but also to impaired movement confidence and increased perception of threat during high-demand actions.

In the present cohort, more than half of the athletes demonstrated high kinesiophobia at long-term follow-up, in line with systematic reviews evidence showing that fear of re-injury is highly prevalent after primary ACL reconstruction and influenced by multiple interacting physical and psychological factors [

4,

8,

16,

17]. Notably, this psychological burden persisted despite a high overall RTS rate, revealing a paradox whereby returning to sport does not necessarily equate to psychological readiness [

5,

15]. Fear of re-injury and reduced confidence were particularly evident during high-demand tasks such as cutting, jumping, and physical contact, activities that place substantial demands on neuromuscular control and rapid force generation [

15,

16,

17]. These findings suggest that return-to-sport clearance should not be interpreted as a binary outcome but rather as a continuum, in which physical, psychological, and neuro-cognitive readiness may evolve at different rates. The persistence of fear-related symptoms despite successful RTS highlights the need for ongoing monitoring beyond the initial return to competition.

Residual quadriceps asymmetry and central motor control alterations may increase threat perception during these tasks, reinforcing fear-avoidance behaviors and potentially contributing to maladaptive movement strategies [

11,

12]. This observation is clinically relevant, as previous papers showed that failure to meet objective RTS discharge criteria is associated with a markedly increased risk of ACL graft rupture [

13,

15,

16]. Moreover, substantial heterogeneity exists in RTS clearance criteria across clinical practice, often relying on time-based thresholds rather than objective neuromuscular benchmarks [

7,

14].

Although quadriceps LSI values around 90% are often considered acceptable, emerging evidence suggests that residual strength and activation deficits may persist even when these thresholds are met [

3,

7]. Persistent quadriceps weakness following ACLR has been consistently documented and is associated with altered movement strategies and increased joint loading [

3,

15]. In addition, cohort-based decision rules using objective discharge criteria have been proposed to reduce re-injury risk, reinforcing the need to move beyond isolated measures [

14].

Future studies should adopt prospective and longitudinal designs to better elucidate the temporal relationships between early neuromuscular recovery, central motor adaptations, and long-term psychological outcomes. The integration of objective neuromuscular assessments with psychological screening and neuro-cognitive testing may provide a more comprehensive framework for return-to-sport decision-making.

Taken together, these findings challenge the adequacy of RTS decision-making models based solely on time from surgery or isolated strength thresholds [

15]. A multidimensional RTS framework, integrating isokinetic strength, limb symmetry, psychological readiness, and neuro-cognitive function appears essential to optimize long-term outcomes and reduce re-injury risk [

6,

12,

13].

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations. The retrospective design limits causal inference. Psychological outcomes were assessed through self-reported questionnaires, which may be subject to recall bias. Direct measures of neuromuscular activation or cortical function were not available, limiting mechanistic interpretation. In addition, the heterogeneity of competitive levels may have influenced psychological responses and RTS expectations.

4.2. Clinical Implications

Isokinetic testing is necessary but not sufficient to guide RTS decisions [

1,

2]. Persistent quadriceps asymmetry and high rates of kinesiophobia highlight the need for integrated rehabilitation strategies [

4,

5]. Clinicians should systematically assess psychological readiness and address AMI through targeted neuromuscular interventions, potentially complemented by neurocognitive and psychosocial approaches, to optimize long-term outcomes and reduce re-injury risk [

6,

9,

12].

5. Conclusions

Male soccer players demonstrate persistent quadriceps neuromuscular asymmetry six months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, despite significant improvements in absolute muscle strength, high return-to-sport rates, and near-complete hamstring recovery. The observed reduction in limb symmetry index from pre- to post-operative assessments suggests persistent deficits in voluntary quadriceps activation, likely related to arthrogenic muscle inhibition and central neurophysiological adaptations [

9,

10,

11]. These neuromuscular alterations coexist with long-term psychological consequences, including kinesiophobia and fear of re-injury, even several years after return to sport [

4,

5,

17]. Collectively, these findings support the idea that ACL injury and reconstruction represent not only a mechanical impairment but a neuro-muscular and neuro-cognitive condition [

11,

12]. Return-to-sport decision-making should therefore move beyond time-based and strength-only criteria and integrate objective neuromuscular symmetry, psychological readiness, and neuro-cognitive factors to promote a safe, sustainable, and durable return to sport [

7,

13,

14,

15].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Methodology: M.I. and G.M.; formal analysis: M.I. and G.M.; investigation: M.I., L.S., S.Z. and G.M.; data curation: M.I. and G.M.; writing – original draft preparation: M.I. and G.M.; writing – review & editing: M.I., L.S., F.M., S.Z., G.G. and G.M.; visualization: M.I. and G.M.; supervision: M.I. and G.M.; project Administration: G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived due to the retrospective study design and the use of anonymized data collected during routine clinical practice, in accordance with local regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the athletes who participated in this study for their availability and collaboration. The authors also acknowledge the clinical and technical staff of the “Performance” Rehabilitation and Medical Center (Siena, Italy) and the “Pegaso” Rehabilitation and Medical Center (Grosseto, Italy) for their support during data collection. The authors further thank Easytech (Firenze, Italy) for technical support related to isokinetic testing procedures. Finally, the authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of colleagues Lorenzo Nuti, Matilde Cosimi, and Stefano Casini for their assistance during data collection and clinical management.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. G.G. is affiliated with the Easytech Research Department. However, Easytech had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, manuscript preparation, or decision to publish.

References

- Rivera-Brown A.M.; Frontera W.R., Fontánez R. et al. Evidence for isokinetic and functional testing in return-to-sport decisions following anterior cruciate ligament surgery. PMR. 2022,14, 678–690.

- Undheim M.B.; Cosgrave C., King E.A. et al. Isokinetic muscle strength and readiness to return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Is there an association? A systematic review and a protocol recommendation. Br J Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1305–1310. [CrossRef]

- Lepley L.K. Deficits in quadriceps strength and activation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Sports Health. 2015, 7, 231–238. [CrossRef]

- MirB.; Vivekanantha P., Dhillon S. et al. Fear of reinjury following primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.2023, 31, 2299–2314.

- Ardern C.L.; Taylor N.F., Feller J.A., et al. A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br J Sports Med. 2013, 47, 1120–1126.

- Naderi A.; Fallah Mohammadi M., Dehgan A, et al. Psychosocial interventions seem to reduce kinesiophobia after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, but a higher level of evidence is needed: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.2023, 31, 5848-5855.

- Burgi C.R.; Peters S., Ardern C.L., et al. Which criteria are used to clear patients to return to sport after primary ACL reconstruction? A scoping review. Br J Sports Med. 2019, 53, 1154–1161. [CrossRef]

- Hart J.M.; Pietrosimone B., Hertel J., et al. Quadriceps activation following knee injuries: A systematic review. J Athl Train. 2010, 45, 87–97. [CrossRef]

- Rice D.A.; McNair P.J. Quadriceps arthrogenic muscle inhibition: Neural mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 40, 250–266.

- McPherson A.L.; Schilaty N.D., Anderson S., et al. Arthrogenic muscle inhibition after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Injured and uninjured limb recovery over time. Front Sports Act Living.2023, 21 (5), 1143376. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez K.M.; Palmieri-Smith R.M., Krishnan C. How does anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction affect the functioning of the brain and spinal cord? A review of neurophysiological changes. J Sport Health Sci. 2021, 10, 172-181.

- PiskinD.; Benjaminse A., Dimitrakis P., et al. Neurocognitive and neurophysiological functions related to ACL injury: A framework for neurocognitive approaches in rehabilitation and return-to-sport tests. Sports Health. 2022, 14, 549–555. [CrossRef]

- Kyritsis P.; Bahr R., Landreau P. et al. Likelihood of ACL graft rupture: Not meeting six clinical discharge criteria before return to sport is associated with a four times greater risk of rupture. Br J Sports Med. 2016, 50, 946–951. [CrossRef]

- Grindem H.; Snyder-Mackler L., Moksnes H. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: The Delaware–Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016, 50, 804–808.

- Ardern C.L.; Webster K.E., Taylor N.F. et al. Return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the state of play. Br J Sports Med. 2011, 45, 596–606. [CrossRef]

- Gerfroit A.; Marty-Diloy T., Laboudie P., et al. Correlation between anterior cruciate ligament–return to sport after injury score at six months after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and mid-term functional outcomes. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 4498-4510.

- Ardern C.L.;, Kvist J., Webster K.E. Psychological aspects of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2016, 24, 77–83. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).