Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 92C05; 92C15; 92C40; 92C45; 80Axx; 82Cxx; 82B35; 82C26

1. Introduction

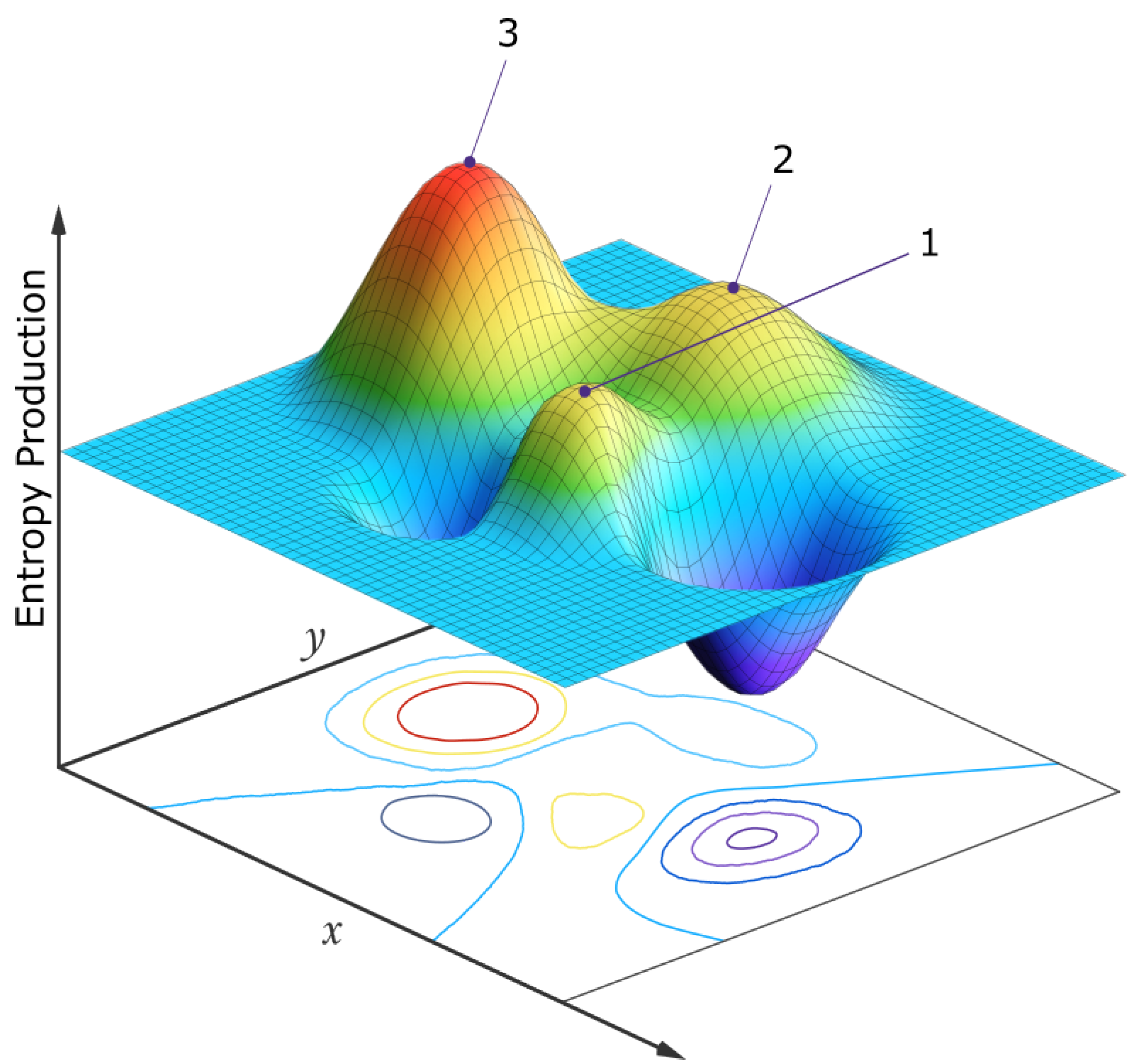

2. Non-Linear Classical Irreversible Thermodynamic Theory

- 1.

- The existence of at least one relatively constant applied external generalized thermodynamic potential defining the environment - the applied thermodynamic forces.

- 2.

- The spontaneous generation of internal generalized thermodynamic flows resulting from these applied external generalized forces and the possibility of new internal forces that these flows themselves generate.

- 3.

- The existence (in the asymptotic time limit) of various sets of these internal (to the system) forces and flows for non-linear systems for the same initial and boundary conditions, (i.e., multiple, locally stable, dissipative structures, or processes, at stationary states), each set of which can have a different rate of dissipation of the applied external potential (entropy production).

- 4.

- External or internal stochastic perturbations which, near a critical point, could cause the non-linear system to leave the local attraction basin in parameter space of one stationary state and evolve to that of another.

- 5.

- The stochastic (non-deterministic) tendency for evolution through perturbation to stationary states (dissipative structures) of generally greater dissipation (entropy production), particularly towards those states with positive feed-back (non-linear auto- or cross-catalytic), since these have a larger “attraction basin” in this generalized parameter space.

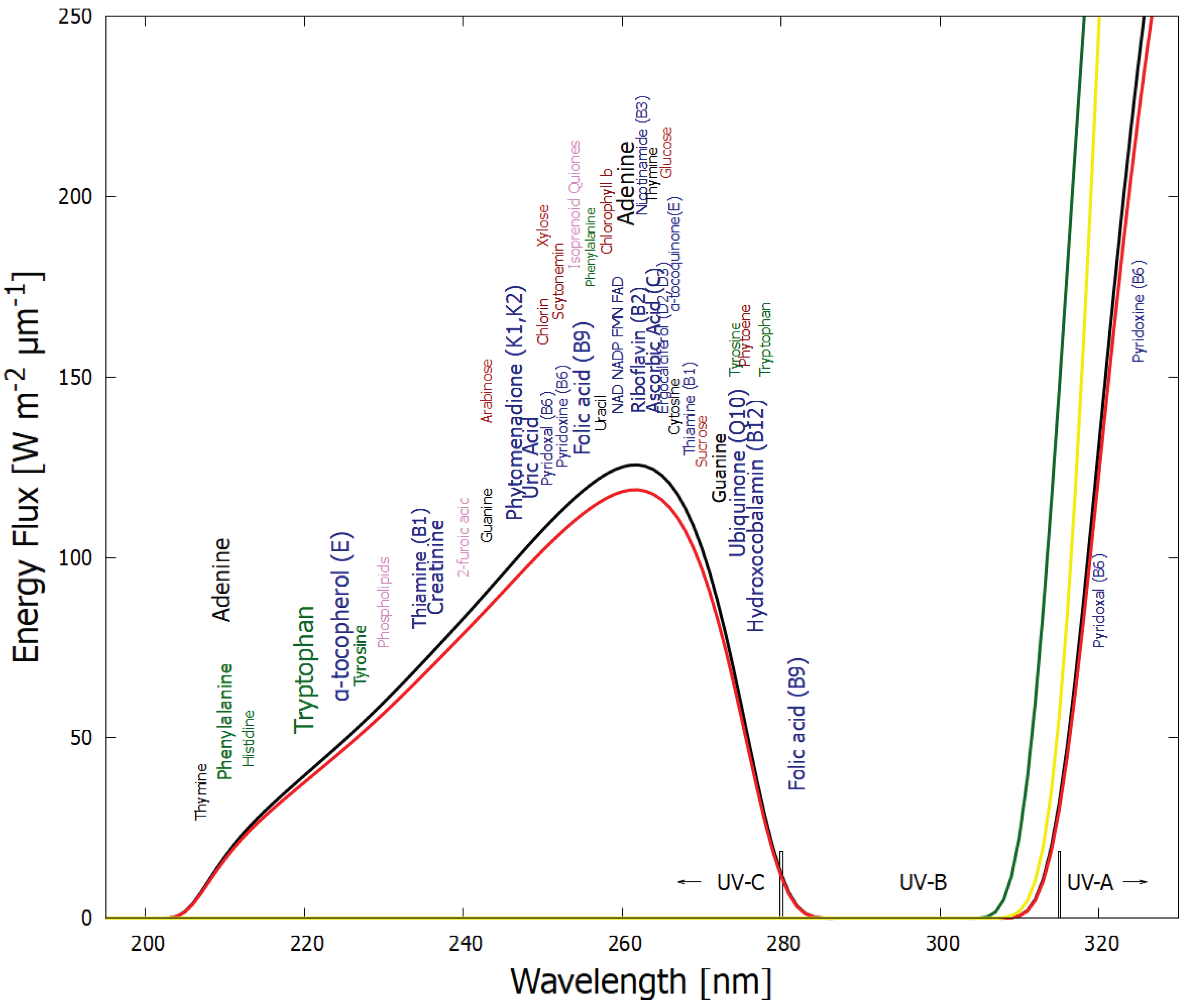

3. The Thermodynamics and Dynamics of Molecular Dissipative Structuring

- 1.

- sufficient energy per photon to overcome activation barriers as well as sufficiently large photoreaction quantum efficiencies,

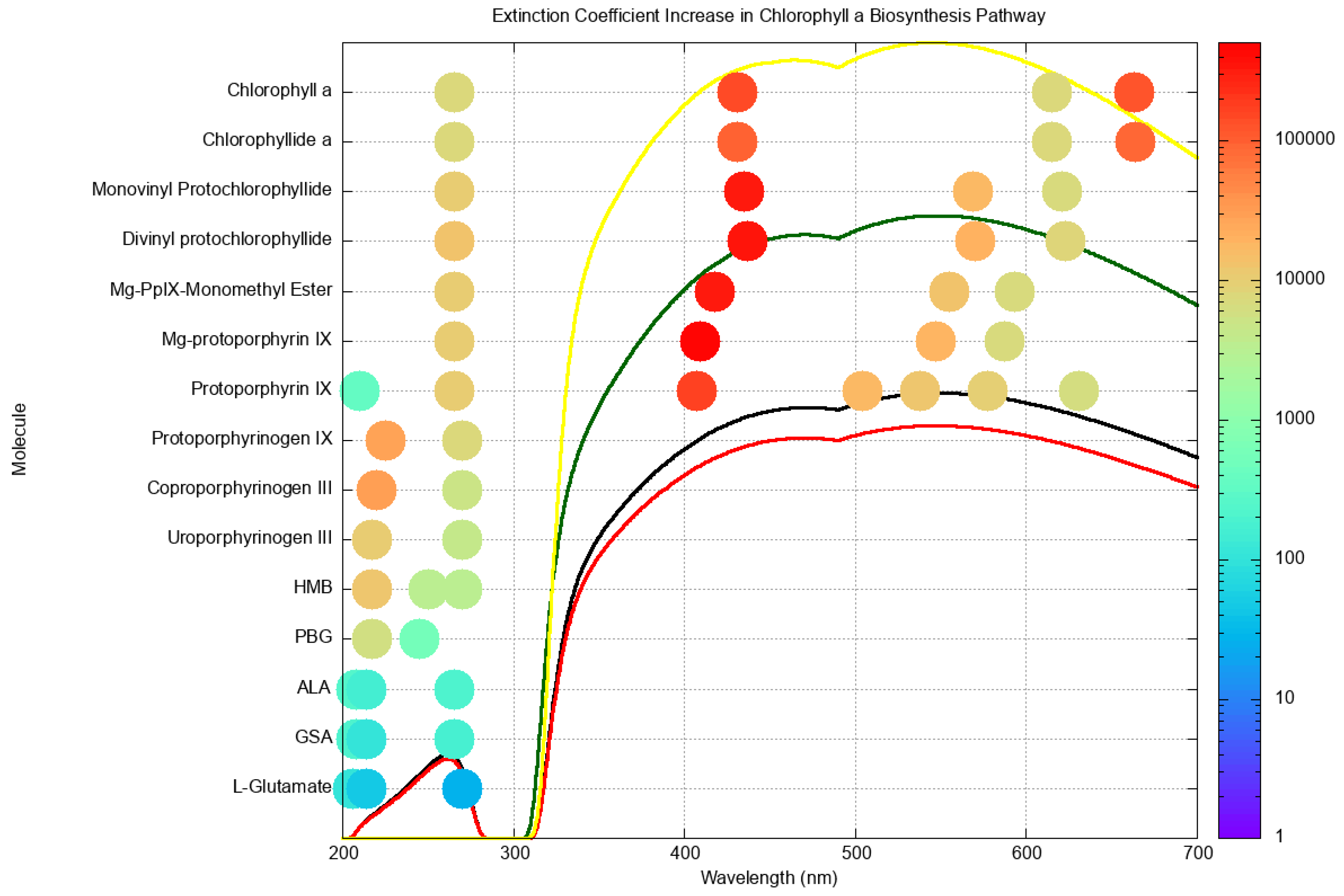

- 2.

- a general increase in photon extinction coefficients as the molecules evolve from simple precursors towards final pigments [25],

- 3.

- the formation of conical intersections connecting excited electronic states with the electronic ground state, allowing ultrafast (subpicosecond) radiationless dissipation (internal conversion),

- 4.

- a general trend towards increasing absorption of the greater intensity longer wavelengths of the prevailing surface solar spectrum,

- 5.

- molecular ionization energies greater than photon energies in the prevailing surface spectrum, inhibiting photon-induced degradation.

4. Examples of Molecular Dissipative Structuring

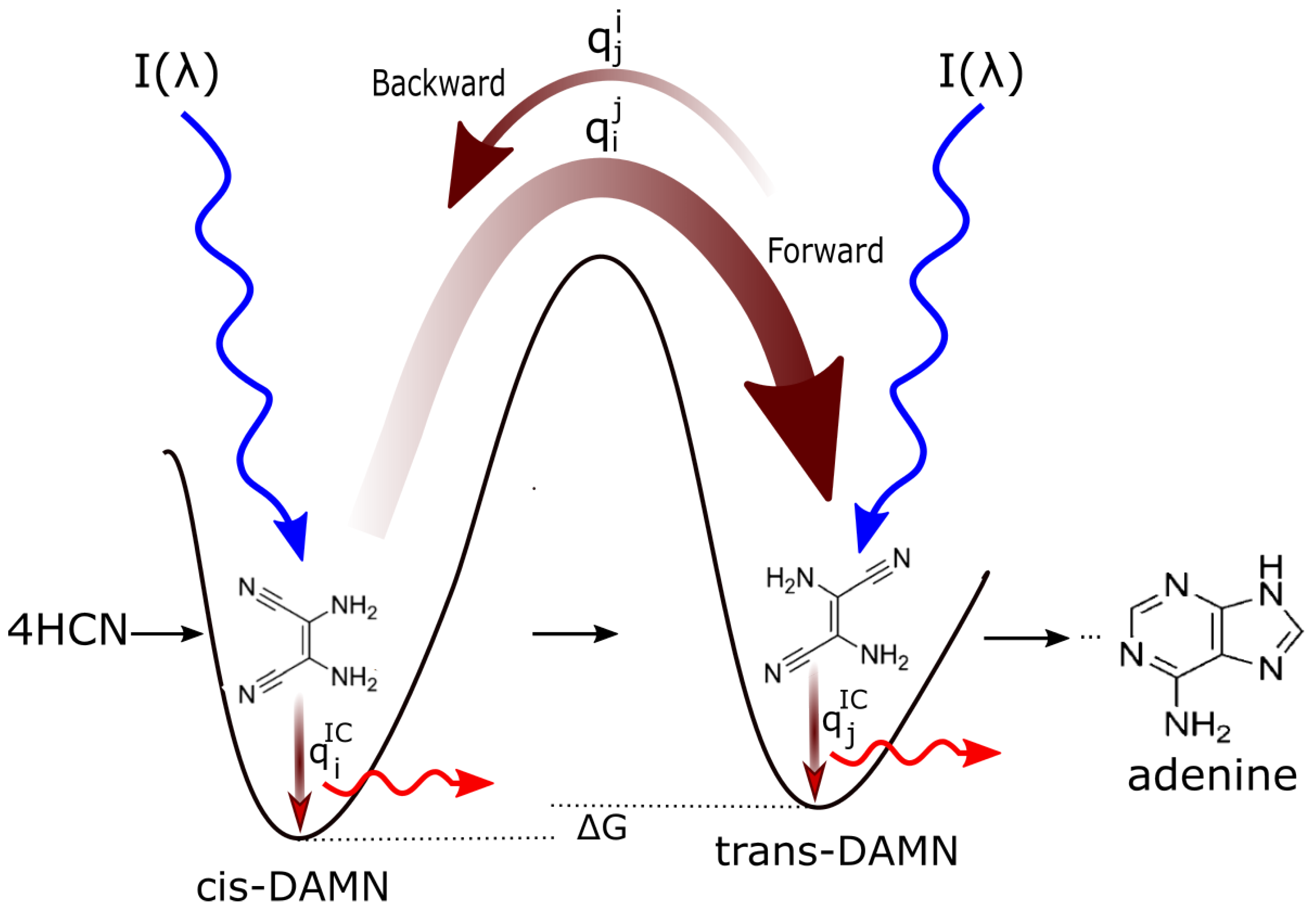

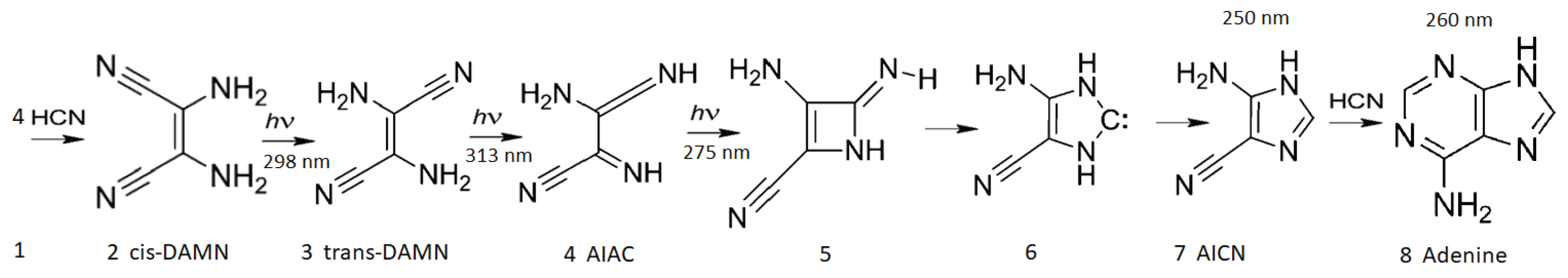

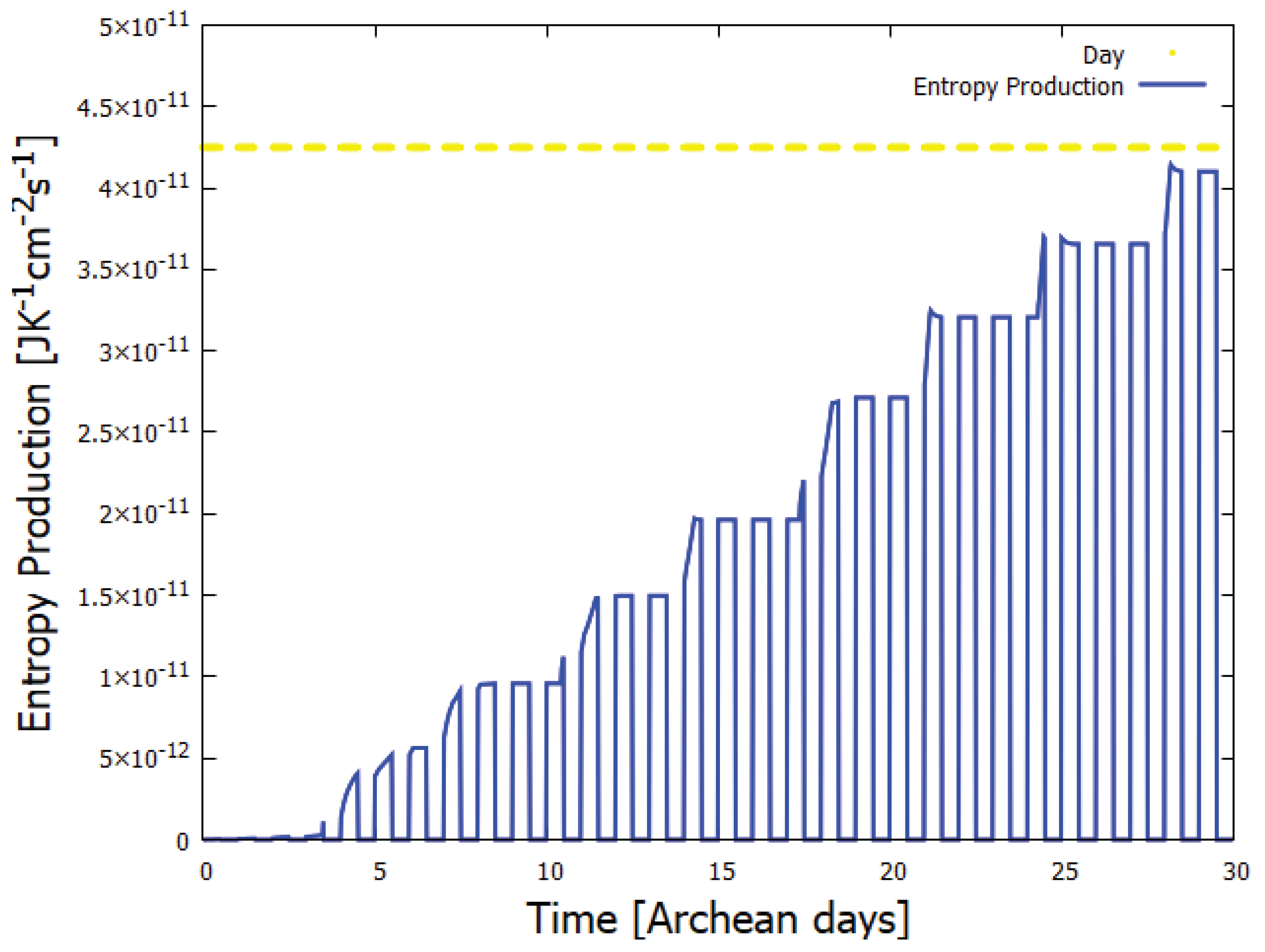

4.1. Nucleotides

4.2. Fatty Acid Vesicles

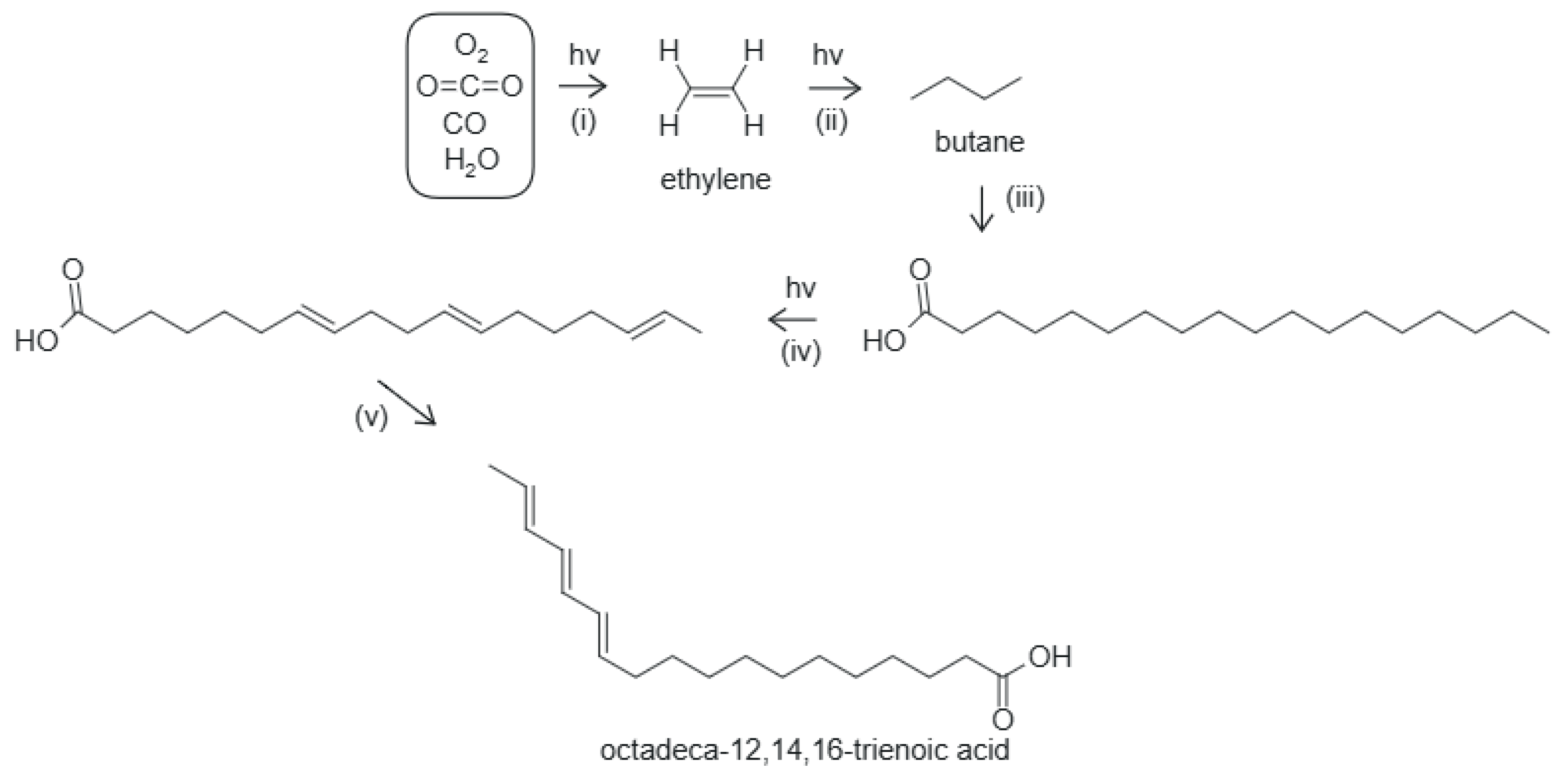

- 1.

- UV-C-induced reduction of CO2 and CO in water saturated with these to form ethylene,

- 2.

- UV-C-induced polymerization of ethylene to form long hydrocarbon tails with an even number of carbon atoms,

- 3.

- oxidation and hydrolysis events to stop the growing of the chain and form the carboxyl group,

- 4.

- UV-C-induced deprotonation of the tails to form a double bond,

- 5.

- double bond migration to give a conjugated diene or triene with a conical intersection and strong absorption within the Archean UV-C spectrum.

4.3. Pigments

5. Dissipative Structuring with Thermodynamic Selection: The Fundamental Creative Force in Biology

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALA | 5-Aminolevulinic Acid |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| CIT | Classical Irreversible Thermodynamic theory |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| GSA | Glutamate-1-Semialdehyde |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| HCN | Hydrogen cyanide |

| HMB | Hydroxymethylbilane |

| PBG | Porphobilinogen |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| TDTOL | Thermodynamic Dissipation Theory for the Origin of Life |

| UV-A | Light within the region 315-400 nm |

| UV-B | Light within the region 280-315 nm |

| UV-C | Light within the region 100-280 nm |

| UV-C (hard) | Light in the region 100-205 nm |

| UV-C (soft) | Light within the region 205-285 nm |

References

- Prigogine, I. Introduction to Thermodynamics Of Irreversible Processes, third ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I. Introduction to Thermodynamics Of Irreversible Processes, third ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Nicolis, G. Biological order, structure and instabilities. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 1971, 4, 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes, I. Phys. Rev. 1931, 37, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes, II. Phys. Rev. 1931, 38, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, L.; Machlup, S. Fluctuations and Irreversible Processes. Phys. Rev. 1953, 91, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, R.D.; Milligan, R.A. The way things move: Looking under the hood of molecular motor proteins. Science 2000, 288, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, H.C.; Brown, D.A. Chemotaxis in Escherichia coli analysed by three-dimensional tracking. Nature 1972, 239, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C. E. coli in Motion; Springer: New York, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Cech, T.R. Peptide bond formation by in vitro selected ribozymes. Nature 1997, 390, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelian, K. Thermodynamic origin of life. ArXiv 2009, arXiv:physics.gen. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelian, K. Thermodynamic dissipation theory for the origin of life. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2011, 224, 37–51. Available online: https://esd.copernicus.org/articles/2/37/2011/esd-2-37-2011.html. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Dissipative Photochemical Origin of Life: UVC Abiogenesis of Adenine. Entropy 2021, 23. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/23/2/217. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meixnerová, J.; Blum, J.D.; Johnson, M.W.; Stüeken, E.E.; Kipp, M.A.; Anbar, A.D.; Buick, R. Mercury abundance and isotopic composition indicate subaerial volcanism prior to the end-Archean “whiff” of oxygen. [https://www.pnas.org/doi/pdf/10.1073/pnas.2107511118]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2107511118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagan, C. Ultraviolet Selection Pressure on the Earliest Organisms. J. Theor. Biol. 1973, 39, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meller, R.; Moortgat, G.K. Temperature dependence of the absorption cross sections of formaldehyde between 223 and 323 K in the wavelength range 225–375 nm. [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/1999JD901074]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2000, 105, 7089–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Natural Selection: From Molecules to the Biosphere. Entropy 2023, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Biosphere. In chapter The biosphere: A thermodynamic imperative; Ishwaran, N., Ed.; INTECH: London, 2012; pp. 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelian, K. Biological catalysis of the hydrological cycle: life’s thermodynamic function. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 2629–2645. Available online: www.hydrol-earth-syst-sci.net/16/2629/2012/. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. A non-linear irreversible thermodynamic perspective on organic pigment proliferation and biological evolution. Conference Series Journal of Physics 475 2013, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Santillán Padilla, N. DNA Denaturing through Photon Dissipation: A Possible Route to Archean Non-enzymatic Replication. bioRxiv. 2014. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2014/11/24/009126.full.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Simeonov, A. Fundamental molecules of life are pigments which arose and co-evolved as a response to the thermodynamic imperative of dissipating the prevailing solar spectrum. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 4913–4937. Available online: https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/12/4913/2015/. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. Thermodynamic Dissipation Theory of the Origin and Evolution of Life: Salient characteristics of RNA and DNA and other fundamental molecules suggest an origin of life driven by UV-C light; Self-published; Printed by CreateSpace: Mexico City, 2016; ISBN 9781541317482. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelian, K. Microscopic Dissipative Structuring and Proliferation at the Origin of Life. In Heliyon; 2017; 3, p. e00424. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5647473/. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Simeonov, A. Thermodynamic explanation of the cosmic ubiquity of organic pigments. Astrobiol. Outreach 2017, 5, 156. Available online: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/thermodynamic-explanation-for-the-cosmic-ubiquity-of-organicpigments-2332-2519-1000156.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. Homochirality through Photon-Induced Denaturing of RNA/DNA at the Origin of Life. Life 2018, 8. Available online: http://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/8/2/21. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Rodriguez, O. Prebiotic fatty acid vesicles through photochemical dissipative structuring. Revista Cubana de Química 2019, 31, 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelian, K.; Santillan, N. UVC photon-induced denaturing of DNA: A possible dissipative route to Archean enzyme-less replication. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01902. Available online: https://www.heliyon.com/article/e01902. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. Photochemical Dissipative Structuring of the Fundamental Molecules of Life. Proceedings, 5th International Electronic Conference on Entropy and Its Applications; Session: Biological Systems 2019.

- Michaelian, K.; Cano, R.E. A Photon Force and Flow for Dissipative Structuring: Application to Pigments, Plants and Ecosystems. Entropy 2022, 24, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamic Foundations of the Origin of Life. Foundations 2022, 2, 308–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, C.; Michaelian, K. Dissipative Photochemical Abiogenesis of the Purines. Entropy 2022, 24, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Pigment World: Life’s Origins as Photon-Dissipating Pigments. Life 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minard, R.D.; Matthews, C.N. HCN World: Establishing Proteininucleic Acid Life via Hydrogen Cyanide Polymers. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 228, U963–U963. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, C.N. Origins: Genesis, Evolution and Diversity of Life. In Series: Cellular Origin and Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology; Seckbach, J., Ed.; Kluwer: Dordrecht, 2004; Vol. 6, chapter The HCN World, pp. 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Catling, D.C.; Zahnle, K.J. The Archean atmosphere. Science Advances 2020, 6, eaax1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, J.P.; Orgel, L.E. An Unusual Photochemical Rearrangement in the Synthesis of Adenine from Hydrogen Cyanide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 1074–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trainer, M.G.; Jimenez, J.L.; Yung, Y.L.; Toon, O.B.; Tolbert, M.A. Nitrogen Incorporation in CH4-N2 Photochemical Aerosol Produced by Far UV Irradiation. In NASA archives; 2012. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20120009529.pdf.

- Rimmer, P.B.; Rugheimer, S. Hydrogen cyanide in nitrogen-rich atmospheres of rocky exoplanets. Icarus 2019, 329, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, E.; Anoop, A.; Nachtigallova, D.; Thiel, W.; Barbatti, M. Photochemical Steps in the Prebiotic Synthesis of Purine Precursors from HCN. Angew. Chem. Int. 2013, 52, 8000–8003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getoff, N. Reduktion der Kohlensäure in wässeriger Lösung unter Einwirkung von UV-licht. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B 1962, 17, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, A.; Antunes, R.; Almeida, D.; Franco, I.J.A.; Hoffmann, S.V.; Mason, N.J.; Eden, S.; Duflot, D.; Canneaux, S.; Delwiche, J.; et al. Photoabsorption measurements and theoretical calculations of the electronic state spectroscopy of propionic, butyric, and valeric acids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 5729–5741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, T.K.; Chatterjee, S.N. Ultraviolet- and Sunlight-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Liposomal Membrane. Radiation Research 1980, 83, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.N.; Calvin, M. The Color of Organic Substances Reports UV absorption maxima for conjugated polyenes: diene 217 nm, triene 258 nm, tetraene 300 nm. Chemical Reviews 1949, 25, 273–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.N.; Kloxin, C.J. Toward an enhanced understanding and implementation of photopolymerization reactions. AIChE J. 2008, 54, 2775–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochida, M.; Kitamori, Y.; Kawamura, K.; Nojiri, Y.; Suzuki, K. Fatty acids in the marine atmosphere: Factors governing their concentrations and evaluation of organic films on sea-salt particles. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2002, 107, AAC 1–1–AAC 1–10. Available online: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2001JD001278. [CrossRef]

- Wellen, B.A.; Lach, E.A.; Allen, H.C. Surface pKa of octanoic, nonanoic, and decanoic fatty acids at the air-water interface: applications to atmospheric aerosol chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 26551–26558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celani, P.; Garavelli, M.; Ottani, S.; Bemardi, F.; Robb, M.A.; Olivucci, M. Molecular “Trigger” for Radiationless Deactivation of Photoexcited Conjugated Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 11584–11585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ma, L. The self-crosslinked ufasome of conjugated linoleic acid: Investigation of morphology, bilayer membrane and stability. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2014, 123, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Calvin, M. Occurrence of fatty acids and aliphatic hydrocarbons in a 3.4 billion-year-old sediment. Nature 1969, 224, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoeven, W.; Maxwell, J.; Calvin, M. Fatty acids and hydrocarbons as evidence of life processes in ancient sediments and crude oils. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1969, 33, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía Morales, J.; Michaelian, K. Photon Dissipation as the Origin of Information Encoding in RNA and DNA. Entropy 2020, 22. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/22/9/940. [CrossRef]

- Lechuga, I.; Michaelian, K. Fatty Acid Vesicles as Hard UV-C Shields for Early Life. Foundations 2023, 3, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Simeonov, A. The Dissipative Photochemical Origin of Photosynthesis. 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Niyogi, K.K.; Wolosiuk, R.A.; Malkin, R. Photosynthesis. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants, 2 ed.; Buchanan, B.B., Gruissem, W., Jones, R.L., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, West Sussex, 2015; pp. 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- Falahati, K.; Hamerla, C.; Huix-Rotllant, M.; Burghardt, I. Ultrafast photochemistry of free-base porphyrin: a theoretical investigation of B → Q internal conversion mediated by dark states This work shows that B → N conversion is barrierless ( 20 fs), followed by N → Q conversion via a conical intersection ( 100 fs), in agreement with experiments on porphine and related free-base porphyrins. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2018, 20, 12483–12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glansdorff, P.; Prigogine, I. Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability and Fluctuations; Wiley - Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Prigogine, I.; Nicolis, G. On Symmetry-Breaking Instabilities in Dissipative Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1967, 46, 3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripple, W.J.; Beschta, R.L. Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: The first 15years after wolf reintroduction. Biological Conservation 2012, 145, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, J.E.; Yu, D.S.; Yoon, S.H.; Jeong, H.; Oh, T.K.; Schneider, D.; Lenski, R.E.; Kim, J.F. Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with Escherichia coli. Nature 2009, 461, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, R. The Cybernetics of Complex Systems: Self-organization, Evolution, and Social Change. In chapter End-directed physics and evolutionary ordering: Obviating the problem of the population of one; Intersystems Publications: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lovelock, J.E. The Ages of Gaia; A Biography of Our Living Earth; W. W. Norton&Company: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kleidon, A.; Fraedrich, K.; Heimann, M.A. Green Planet Versus a Desert World: Estimating the Maximum Effect of Vegetation on the Land Surface Climate. Climatic Change 2000, 44, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanadesikan, A.; Emanuel, K.; Vecchi, G.A.; Anderson, W.G.; Hallberg, R. How ocean color can steer Pacific tropical cyclones. Geophysical Research Letters 2010, 37, L18802. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2010GL044514 [https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2010GL044514. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. Thermodynamic stability of ecosystems. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2005, 237, 323–335. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022519305001839?via%3Dihub. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).