1. Introduction

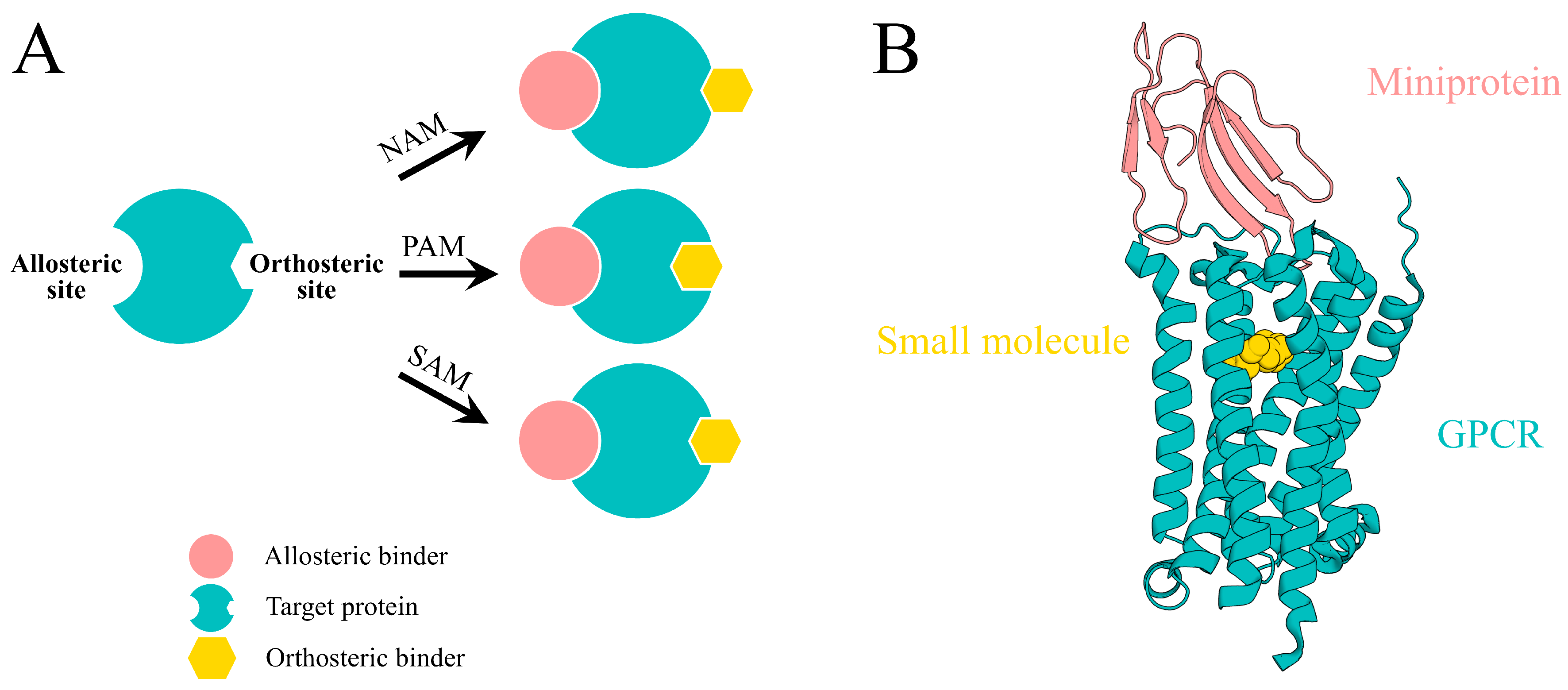

Allosteric modulation is a fundamental mechanism of protein function in which ligand binding at a site remote from the active (orthosteric) site induces conformational or dynamic changes that modulate activity [

1,

2]. Orthosteric sites, which serve as the native binding pockets for substrates, endogenous ligands, or cofactors, are typically highly conserved across protein families due to strict functional constraints [

3]. In contrast, allosteric sites are topologically distinct and exhibit lower sequence conservation. Several distinct modes of allosteric modulation have been described (

Figure 1A) [

4], including negative allosteric modulation (NAM), which decreases orthosteric ligand efficacy, positive allosteric modulation (PAM), which enhances orthosteric signaling, and silent allosteric modulation (SAM), which binds allosteric sites without without intrinsic efficacy. The unique properties make allosteric sites attractive targets for achieving superior selectivity and reduced off-target effects [

4,

5,

6].

The molecular basis of allostery is intimately tied to protein dynamics and is best understood through the modern ensemble model [

2]. It views proteins not as fixed structures but as dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations governed by an energy landscape [

7,

8]. Allosteric ligands reshape this energy landscape by shifting the population distribution among conformational states. Allosteric ligands stabilize or destabilize specific ensembles, alter loop flexibility, or modulate oligomerization interfaces, without necessarily relying on discrete structural changes, fixed propagation pathways, or simple two-state models like the relaxed (R) and tense (T) states. This population shift can occur through diverse mechanisms, including entropic effects, kinetic coupling, or network perturbations, even in the absence of observable structural alterations [

7]. Allosteric modulation exploits these transient or cryptic pockets that become druggable only in certain ensemble states [

9]. Understanding allostery thus demands integrated structural, thermodynamic, and kinetic analyses, as well as tools capable of capturing protein motion at atomic resolution across the conformational ensemble [

10,

11].

Allosteric modulators span diverse chemical classes. Metal ions [

12] (e.g.,

,

, or

) act as endogenous regulators in numerous proteins. Small molecules remain the predominant modality and have produced clinical agents targeting proteins, yet they often struggle to engage shallow, dynamic, or extended allosteric interfaces [

13]. Peptides can access larger surfaces but typically suffer from limited conformational stability and poor pharmacokinetic properties [

4,

5]. Antibody-based binders provide high affinity and specificity at the cost of large size and restricted access to many allosteric sites [

6]. Miniproteins (typically 3–8 kDa), by contrast, occupy an intermediate design space, combining larger interaction surfaces than small molecules with greater compactness and adaptability than antibodies, enabling effective recognition and modulation of complex allosteric interfaces and protein–protein interactions [

6,

14]. A naturally occurring example of miniprotein-mediated regulation is observed in G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) [

15] (

Figure 1B). These attributes make engineered miniproteins particularly well suited for targeting previously intractable allosteric sites, positioning them as promising scaffolds for next-generation allosteric therapeutics [

16,

17,

18].

So far, AI–driven computational approaches are reshaping the investigation of allosteric modulation by enabling systematic analysis of complex conformational ensembles, identification of cryptic allosteric sites, and de novo design of miniproteins [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Miniproteins as potential allosteric modulators represent a rapidly advancing frontier, offering high specificity and enhanced interface adaptability for targets long considered “undruggable”. In the following sections, we focus specifically on AI–driven design strategies, including structure analysis and generative algorithms, and discuss how these methods are being leveraged to optimize miniprotein binders for allosteric sites with two recent and representative case studies.

2. AI-Driven Pipeline for Designing Allosteric Miniprotein Modulators

Miniproteins occupy a unique intermediate design space between small molecules and large protein biologics [

24,

25], thereby providing extended and chemically diverse interaction surfaces that are particularly well suited for engaging shallow, dynamic, and weakly conserved allosteric regulatory sites. Unlike orthosteric pockets, allosteric sites are often transient, conformationally heterogeneous, and weakly conserved, posing fundamental challenges for classical structure-based drug discovery.

Prior to the advent of modern AI methodologies, the computational design of miniprotein binders for allosteric modulation primarily relied on structure-guided rational design and physics-based

de novo modeling [

26]. These approaches leveraged experimentally determined or homology models to identify putative allosteric pockets, infer functional hotspots, and engineer binders through motif grafting, interface redesign, or scaffold repurposing. While successful in selected cases, such strategies were inherently constrained by limited conformational sampling, strong dependence on prior structural knowledge, and the difficulty of explicitly modeling long-range allosteric coupling within complex protein energy landscapes.

Recent advances in AI and machine learning are reshaping this design paradigm [

23]. AI-driven pipelines enable a more integrated treatment of allostery by combining conformational ensemble modeling, generative backbone construction, sequence optimization, and binding assessment within a unified computational framework [

27]. Collectively, AI-enabled design pipelines are transforming the development of allosteric miniprotein modulators from a largely heuristic, case-by-case endeavor into a scalable and systematic process. By coupling data-driven generative models with biophysically grounded evaluation and experimental feedback, these approaches are significantly accelerating the discovery of functional allosteric binders. In parallel, they are expanding the accessible design space beyond what was achievable with traditional computational methods alone.

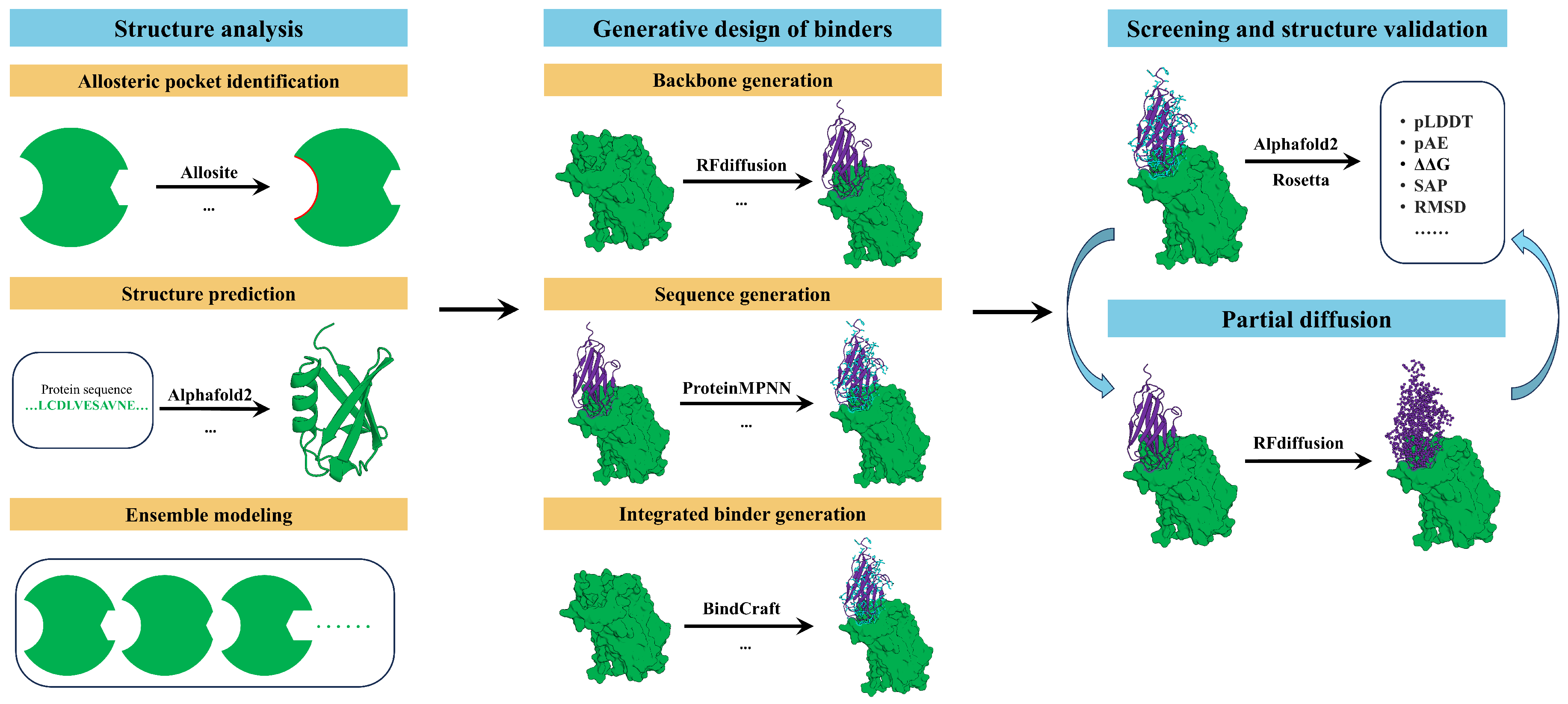

Figure 2 illustrates the AI-driven computational pipeline for the design of allosteric miniprotein modulators.

2.1. Structure Analysis

2.1.1. Allosteric Pocket Identification

Identifying biologically relevant allosteric pockets is a critical first step toward understanding and engineering regulatory control in proteins [

28] (

Figure 2). In contrast to orthosteric binding sites, allosteric pockets are frequently shallow, weakly conserved, and highly dependent on the underlying conformational ensemble, with many sites being cryptic or only transiently populated [

29,

30]. This intrinsic dynamical nature substantially limits the effectiveness of static, geometry-based analyses. Although experimental techniques—including NMR spectroscopy, cryo-electron microscopy, hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS), site-directed mutagenesis, and functional perturbation assays—can provide high-resolution insights into dynamic regulatory regions and allosteric communication [

31,

32], they are typically labor-intensive, costly, and low-throughput. These constraints have motivated the widespread adoption of computational approaches as scalable alternatives for systematic allosteric site discovery.

A broad spectrum of computational methods has therefore been developed to interrogate allostery from a dynamic and network-centric perspective [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Molecular dynamics simulations, Markov state models, elastic network models, coevolutionary coupling analysis, and residue interaction network theory have been routinely employed to reveal allosteric pathways, dynamic hotspots, and long-range coupling mechanisms. More recently, machine-learning-based models have emerged as particularly powerful tools, leveraging curated structural and dynamical datasets to detect cryptic pockets, predict ensemble shifts, and quantify functional coupling with improved accuracy and reduced computational cost (

Table 1) [

40,

41]. Early AI-driven approaches, such as Allosite [

33], framed allosteric pocket identification as a supervised classification task using physicochemical and geometric descriptors, whereas subsequent methods, including AlloPred [

34], integrated perturbation information from normal mode analysis to implicitly encode allosteric coupling. Together, these developments have established machine learning as a central paradigm for scalable and mechanistically informed allosteric pocket identification.

Further improvements were achieved by integrating richer structural feature representations and more robust learning strategies. AllositePro [

35] expanded the feature space and optimized model training to enhance prediction stability across diverse protein families. Building on curated allosteric datasets, the PASSer [

36] framework adopted ensemble learning to improve generalization and scalability, while PASSer 2.0 [

37] further advanced this direction through an AutoML architecture that automates feature selection and model optimization. Rather than treating allosteric pocket identification as a binary classification task, PASSerRank [

38] reframed the problem as a learning-to-rank task, enabling prioritization of candidate pockets according to their predicted regulatory relevance.

Most recently, ensemble optimization strategies such as MEF-AlloSite [

39] have combined multiple machine-learning models with optimized feature selection to achieve improved robustness and accuracy in identifying allosteric regions at both pocket and site levels. These AI-driven approaches transform allosteric pocket identification from heuristic, structure-centric analyses into a data-driven inference problem, providing a systematic and scalable foundation for downstream allosteric modulator and binder design.

2.1.2. Structure Prediction and Ensemble Modeling

Accurate structural models of target proteins are critical for designing allosteric miniprotein binders, as allosteric modulation and ligand recognition are governed by protein dynamics and conformational ensembles rather than a single static structure [

42]. Allosteric modulation is fundamentally an ensemble phenomenon, operating through shifts in conformational equilibria on a complex energy landscape, which makes ensemble-level structural information essential for rational binder design [

1,

2,

8]. Traditional experimental structures obtained by X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM typically represent low-energy or highly populated conformations and may fail to capture excited or low-population states that harbor functional allosteric or cryptic binding sites [

13,

29].

Recent advances in AI-based and MSA-based structure prediction have substantially expanded access to high-quality atomic models (

Table 2). Deep learning frameworks such as AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold achieve near-experimental accuracy for monomeric proteins and many protein complexes by leveraging evolutionary information encoded in multiple sequence alignments [

43,

44,

45]. Extensions including AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold 3 further enable modeling of oligomeric assemblies and biomolecular interactions that are directly relevant to allosteric signaling and regulation [

46,

47]. These AI-predicted structures often serve as starting points for exploring conformational variability and for generating structural hypotheses in systems lacking experimental data [

23,

26].

To address the inherently dynamic nature of allostery, structure prediction is increasingly integrated with ensemble modeling techniques [

11,

48,

49]. Molecular dynamics simulations, together with enhanced sampling approaches such as metadynamics or replica-exchange molecular dynamics, enable systematic exploration of conformational landscapes beyond single predicted structures and provide access to transient or functionally relevant states [

2,

41]. AI-assisted strategies further guide ensemble generation by biasing sampling toward alternative conformational states inferred from evolutionary couplings, energetic frustration, or learned structure–dynamics relationships [

9,

21].

Such ensemble models are particularly valuable for miniprotein binder design, as they help identify conformations that expose regulatory surfaces compatible with extended protein–protein interaction interfaces [

24,

25]. In practical design workflows, ensemble-aware structural models guide the selection of target conformations for binder generation, reducing the risk of designing binders that recognize only rare or non-functional states and improving the likelihood of functional allosteric modulation. Recent AI-driven binder design frameworks explicitly benefit from this ensemble perspective, linking structure prediction and conformational sampling with generative design strategies [

16,

27].

2.2. Generative Design of Binders

Following structural analysis, the generative design stage focuses on constructing miniprotein binders that are geometrically, energetically, and dynamically compatible with target allosteric sites. Unlike small-molecule design, which prioritizes pocket occupancy, miniprotein design aims to engineer extended interfaces capable of engaging regulatory surfaces and stabilizing specific conformational states within target protein’s energy landscape. Generative models are therefore tasked not only with producing binders that bind tightly, but also with shaping interactions that bias conformational equilibria underlying allosteric modulation [

50].

AI-driven generative frameworks treat binder design as a conditional generation problem [

51], in which backbone topology and amino-acid sequence are sampled under explicit constraints imposed by the target structure, binding geometry, and functional objectives (

Figure 2). These pipelines typically decompose the design problem into backbone generation, sequence design, and integrated co-optimization, enabling efficient exploration of the vast combinatorial space associated with miniprotein binders (

Table 3).

2.2.1. Backbone Generation

Backbone generation represents the first and most structurally constrained stage of de novo miniprotein binder design, in which three-dimensional protein scaffolds are generated to geometrically complement a target binding surface. At the miniprotein scale, backbone topology critically determines fold stability, surface curvature, and the spatial organization of interface residues. Consequently, backbone generation models must balance physical realism with sufficient flexibility to accommodate diverse protein–protein interaction geometries.

Recent advances in this area have been driven primarily by generative models operating directly in three-dimensional coordinate space, with diffusion- and flow-based approaches emerging as dominant paradigms [

52,

53,

54,

55]. RFdiffusion exemplifies diffusion-based backbone generation, formulating scaffold design as an iterative denoising process that transforms random coordinate noise into structured protein backbones consistent with learned geometric priors [

52]. By conditioning generation on target surface geometry, interface residue positions, or rigid-body constraints, RFdiffusion enables the design of miniprotein backbones that are explicitly shaped to engage challenging protein surfaces, including shallow and discontinuous allosteric regions.

In contrast, complementary generative models such as Chroma [

56] and FoldFlow [

55] primarily focus on general

de novo protein backbone generation rather than target-conditioned binder design, and thus currently offer limited direct utility for high-precision binder scaffolding, despite their potential as future extensible frameworks. These backbone-generation methods aim to produce physically plausible and foldable miniprotein scaffolds that define a viable structural substrate for downstream optimization. However, backbone-only generation does not ensure functional binding, as interface chemistry and energetic complementarity are not explicitly resolved at this stage. Backbone generation therefore serves primarily to establish geometric feasibility, while sequence design and integrated structure–sequence optimization are required to achieve functional miniprotein binders.

2.2.2. Sequence Design

Following backbone generation, sequence design assigns amino-acid identities that stabilize the intended fold and mediate favorable interactions with the target surface. This inverse folding problem is particularly stringent for miniprotein binders, where limited sequence length balances the coupling between folding stability, interface specificity, and conformational robustness. AI-driven sequence design approaches address this challenge by learning conditional probability distributions over sequence space given a fixed three-dimensional backbone.

Graph-based neural architectures trained on large structural datasets have become central to AI-driven sequence design. ProteinMPNN [

57] represents a widely adopted message-passing neural network that encodes residue–residue spatial relationships and predicts amino-acid probabilities compatible with a given backbone, enabling efficient and accurate sequence optimization for miniprotein scaffolds. PiFold [

58] adopts a related graph neural network paradigm optimized for scalability and computational efficiency, facilitating rapid sequence design cycles for compact proteins.

An alternative class of inverse folding models leverages pretrained protein language models. ESM-IF1 [

59] projects structural information into semantically enriched embedding spaces learned from large-scale sequence data, implicitly encoding evolutionary and biophysical constraints. This language-model-based strategy enables the generation of sequences that are not only structurally compatible but also evolutionarily plausible.

Across these approaches, the unifying objective is to generate sequences that reliably fold into the designed backbone while forming specific, energetically favorable contacts at the binder–target interface. Because these models typically assume a fixed backbone, their effectiveness motivates the development of integrated frameworks that jointly optimize structure and sequence, as introduced in the following.

2.2.3. Integrated Binder Generation

While backbone generation and sequence design can be executed as separate stages, integrated binder generation frameworks aim to co-optimize structure and sequence within a unified generative process. This integration is particularly advantageous for miniprotein binders, where the interface geometry, residue composition, and folding stability are tightly coupled.

In the past two years, several integrated AI-based approaches relying on structure prediction feedback have guided generative optimization. AlphaProteo [

60] and AlphaDesign [

61] employ AlphaFold-assisted evaluation to iteratively refine binder sequences and conformations toward structurally stable and functionally competent states. In these frameworks, structure prediction acts as an implicit physical filter that biases generative sampling toward favorable folding and interaction profiles. O-design [

62] emphasizes objective-driven interface refinement by combining energy-based scoring with deep learning–guided sequence optimization.

Some other recent methods adopt fully end-to-end generative paradigms. BindCraft [

63] implements an automated one-shot design pipeline that integrates backbone generation, sequence assignment, and confidence-based filtering, achieving high experimental hit rates for

de novo miniprotein binders. BoltzGen [

64] extends this concept through an all-atom generative framework that unifies structure and sequence sampling, enabling universal binder design across diverse protein targets. Similarly, PXDesign [

65] provides an end-to-end pipeline combining generative modeling with rigorous post hoc confidence assessment to prioritize experimentally viable designs.

PPDiff [

66] represents a joint sequence–structure diffusion framework capable of directly generating protein–protein complexes, including miniprotein binders, within a single generative process. By modeling interface formation as an emergent property of coupled structure and sequence generation, such approaches further blur the boundary between backbone synthesis and sequence design.

Together, these integrated generative systems represent a significant advance in computational binder design, enabling coherent exploration of structure–sequence space and providing scalable, AI-driven routes to engineer high-affinity and high-specificity miniprotein binders for challenging protein targets.

2.3. Screening and Structure Validation

After generative modeling, large numbers of

de novo miniprotein binders must be computationally screened to identify candidates that are structurally reliable and likely to engage the target (

Figure 2) [

67]. In this stage, MSA-based structure prediction models, particularly AlphaFold2, serve as high-precision filters. Although these binders typically lack natural evolutionary homologs, AlphaFold’s implicit structural and physical priors provide stringent checks on foldability and topology. Key screening metrics include the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT), which estimates residue-level structural confidence, and predicted aligned error (pAE), which evaluates the relative positioning of residue pairs across the binder–target interface [

68]. Designs with low pLDDT, high interface pAE, or significant deviations from the intended backbone (e.g., measured via RMSD) are efficiently filtered, ensuring that only geometrically plausible candidates proceed to downstream validation.

Complementary to AI-driven screening, physics-based scoring functions, most commonly implemented in Rosetta, assess atomic-level interactions and interface quality. The Rosetta interface binding free energy change (

) estimates the energetic contribution of the binder–target interface, while surface complementarity and hydrophobic packing are evaluated using metrics such as the solvent-accessible surface area penalty (SAP_score) [

69]. Integrating AlphaFold2 confidence metrics with Rosetta energy-based evaluations provides a balanced assessment of both structural plausibility and interface competency [

17,

18]. Designs that satisfy both criteria are prioritized as high-confidence candidates for experimental characterization, ensuring that selected binders are geometrically consistent, energetically favorable, and likely to function as intended.

2.4. Partial Diffusion

Partial diffusion is a refinement technique in computational protein design, implemented within the RFdiffusion framework [

52]. It works by selectively adding noise to certain regions of a protein structure and then denoising them to generate optimized variations, while keeping other regions fixed. In the context of miniprotein binder design, this approach enhances affinity, diversity, and specificity. RFdiffusion can selectively re-diffuse only a subset of high-ranked backbones, preserving key structural elements such as the overall fold or anchoring interactions at the allosteric site. This targeted resampling enables local structural optimization without disrupting previously identified favorable binding geometries.

Following partial diffusion, redesigned backbones are subjected to sequence redesign, and the resulting models are re-evaluated using AlphaFold2 confidence metrics, including pLDDT and interface pAE. Designs that exhibit improved structural confidence or interface definition are retained and recycled as inputs for subsequent rounds of partial diffusion. By iterating this cycle of constrained backbone resampling, sequence optimization, and AlphaFold2-based evaluation, the overall quality and reliability of allosteric miniprotein designs can be progressively enhanced [

27,

70].

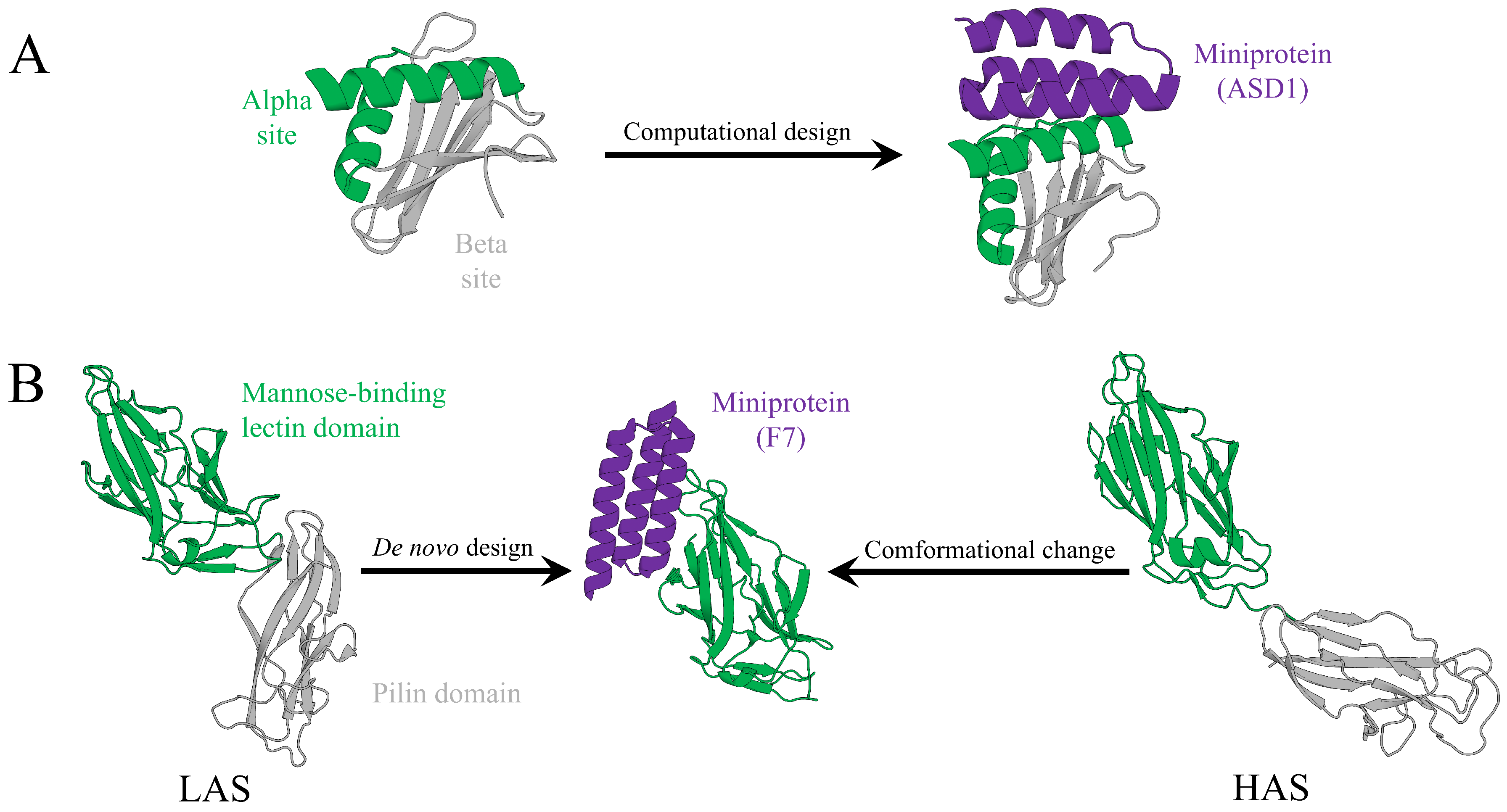

3. Latest Case Study in AI-Driven Design of Miniprotein Modulators

While direct precedents for AI-driven miniprotein design explicitly targeting allosteric sites remain limited, recent two studies employing

de novo design against non-orthosteric pockets provide close analogs. These two approaches modulate protein function through conformational perturbations or interface disruptions, akin to allosteric mechanisms. Below, we introduce these two representative examples (

Figure 3).

3.1. Case 1: High-Affinity Binders to the Flpp3 Virulence Factor

A compelling example is the

de novo design of high-affinity miniprotein binders targeting Flpp3, a virulence factor from

Francisella tularensis (

Figure 3A) [

71]. Notably, Flpp3 lacks deep pockets or known binding partners, rendering it challenging for conventional small-molecule inhibition. The designed binders aim to target two distinct surfaces on Flpp3. Site I corresponds to an electronegative

-helical face that is hypothesized to mediate membrane interaction, whereas Site II is an electropositive

-sheet face. Binding at these surfaces may disrupt immune evasion and bacterial dissemination through induced conformational changes or modulation of protein–protein interactions. Although not explicitly described as allosteric, this strategy closely parallels classical allosteric modulation.

The design pipeline integrated physics-based docking with deep learning tools. Rotamer interaction fields were generated using RIFGen, scaffold placement was performed with PatchDock, and interface refinement was carried out using RIFDock. ProteinMPNN was employed for sequence design, followed by iterative backbone optimization using Rosetta FastRelax. AlphaFold2 was then used for model filtering. Selection criteria emphasized predicted structural confidence and interface quality, including pLDDT values greater than 80–90, interface PAE below 6, Rosetta values less than to kcal/mol, and SAP scores below 30–35.

The pipeline began with a library of 43,724 miniprotein scaffolds ranging from 25 to 65 amino acids in length and generated approximately 500,000 docked conformations. This process yielded 15,000 -site and 8,817 -site candidates for experimental screening. Experimental screening and validation confirmed that several designed miniproteins bind Flpp3 with nanomolar to sub-nanomolar affinity. Yeast surface display–based selection identified a small set of enriched - and -site binders adopting three-helix bundle topologies, consistent with the intended scaffold designs.

Biophysical characterization demonstrated high binding affinity and exceptional stability of the top candidates, while structural analyses revealed near-atomic agreement between the designed models and experimentally determined complex structures. These results validate the accuracy of the AI-assisted design pipeline in targeting shallow, non-orthosteric protein surfaces and demonstrate its potential for functional modulation through allosteric-like mechanisms.

3.2. Case 2: Miniprotein Inhibitors of Bacterial Adhesins

Another illustrative example is the design of miniprotein inhibitors targeting chaperone–usher pathway (CUP) adhesins from uropathogenic

Escherichia coli and

Acinetobacter baumannii, which mediate urinary tract infections (UTIs) (

Figure 3B) [

72]. Here, we focus on designed F7, a miniprotein inhibitor of the FimH adhesin from

E. coli. Rather than directly occupying the orthosteric host receptor–binding site, F7 binds to a pocket adjacent to this site that is preferentially accessible in the low-affinity state (LAS) of FimH. Binding at this site induces a conformational population shift that disfavors the high-affinity state (HAS), thereby exerting allosteric-like inhibitory effects. By stabilizing inactive conformations, F7 disrupts host receptor binding and biofilm formation.

F7 was wholly using the AI-driven pipeline designed to explore the large conformational and sequence space, integrating hotspot-conditioned RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN sequence optimization, Rosetta interface evaluation, and AlphaFold2 (AF2)–based structural filtering. Approximately 10,000 backbone designs were generated per target using crystal structures of FimH in both the high-affinity (HAS; PDB: 1UWF) and low-affinity (LAS; PDB: 3JWN) states, with hotspot residues proximal to the mannose-binding pocket specified as diffusion constraints. For each backbone, multiple sequences were assigned using ProteinMPNN and subjected to initial AF2 filtering, retaining designs with pLDDT values greater than 80 and predicted aligned error (pAE) below 10.

High-confidence designs were further refined through iterative partial diffusion, followed by sequence reassignment and AF2 evaluation. Final candidates were selected using stringent complex- and monomer-level criteria, including AF2 metrics for the complex (binder pLDDT ≥ 90 and interface pAE ≤ 6–6.5), favorable Rosetta interface metrics ( kcal/mol and SAP score ≤ 40), and AF2 monomer confidence for the isolated minibinder (pLDDT ≥ 90). Top-ranked designs were synthesized and screened by cDNA display, leading to the identification of F7.

Experimental screening and validation identified F7 as a high-affinity binder that selectively stabilizes the low-affinity state of FimH, inhibiting red blood cell aggregation and biofilm formation. Structural and functional analyses, including X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and in vivo UTI models, confirmed the designed binding mode and conformational modulation mechanism.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

Allosteric modulation represents a fundamental principle by which biological systems achieve long-range control over protein activity, signal transduction, and gene regulation. Proteins do not function solely through isolated active sites; rather, they operate as dynamic networks, where local perturbations propagate across spatial distances to modulate enzymatic activity, receptor signaling, oligomerization, and transcriptional output. This capacity for remote control underlies critical biological processes, including ion channel gating, receptor activation, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation, and is thus considered a “second layer” of regulation beyond primary ligand recognition, providing robustness and tunability to complex signaling systems [

73].

From a therapeutic perspective, allosteric modulation offers significant advantages over conventional orthosteric drugs. Orthosteric sites are often highly conserved, particularly within kinases, GPCRs, and nuclear receptors, increasing the risk of off-target binding, cross-reactivity, and dose-limiting toxicity. Even highly specific orthosteric ligands may induce adverse effects by perturbing normal physiological signaling. In contrast, allosteric modulators act at less conserved regulatory sites, enabling higher selectivity, reduced systemic toxicity, and precise modulation of protein function rather than simple inhibition or activation [

74,

75,

76,

77]. By modulating conformational equilibria, allosteric binders can bias signaling pathways, control oligomeric states, or selectively affect disease-associated functional states, thus expanding the druggable target space.

Despite these advantages, allosteric modulators have historically been challenging to discover [

4,

6]. Allosteric sites are often shallow, transient, or only populated in specific conformational states, making them poorly suited to traditional high-throughput screening strategies optimized for small molecules. A lack of structural and mechanistic understanding of long-range coupling further limits rational intervention. Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy, solution-based structural techniques, and the accumulation of large structural databases have begun to illuminate these regulatory landscapes. Nonetheless, experimental approaches alone are insufficient to systematically explore the vast combinatorial space of potential allosteric binders.

In this context, AI-driven protein design has emerged as a transformative enabling technology. By learning from large-scale structural, sequence, and biophysical data, modern AI models capture the principles governing protein folding, interaction geometry, and conformational plasticity. Unlike traditional optimization strategies that primarily refine existing scaffolds, AI enables genuine de novo exploration of protein sequence and structure space, allowing the design of entirely new architectures tailored to specific regulatory sites. Importantly, AI does not replace experimental screening but refines it: computational design narrows the astronomically large sequence space to a high-quality subset, efficiently guiding subsequent experimental selection and optimization.

Within this paradigm, miniproteins occupy a uniquely advantageous position [

14,

16,

17,

18,

71,

72]. Compared to small molecules, they offer larger and more versatile interaction surfaces, enabling high-affinity and highly selective recognition of shallow or extended allosteric interfaces. Their inherent structural diversity and capacity for multivalent interactions allow effective engagement of regulatory surfaces involved in protein–protein interactions and conformational control. At the same time, miniproteins are smaller than antibodies, allowing access to sterically restricted environments and, in some cases, intracellular targets inaccessible to large biologics. Advances in computational stabilization and sequence optimization further enhance their structural robustness and functional reliability, making them ideal candidates for allosteric modulation.

Taken together, AI-driven de novo design of miniprotein allosteric modulators represents not merely an incremental improvement but a qualitative shift in drug discovery strategy. Rather than competing with endogenous ligands at highly conserved active sites, this approach leverages regulatory architecture, conformational dynamics, and system-level control to achieve precise modulation of protein function. While challenges remain—including accurate modeling of conformational entropy, reliable prediction of in vivo behavior, and integration of developability constraints—the convergence of AI, structural biology, and protein engineering provides a powerful framework to address them.

Ultimately, as AI-driven design methodologies continue to mature, this paradigm promises to deepen mechanistic understanding of allosteric modulation while enabling novel therapeutic strategies. By coupling

de novo protein design with iterative experimental validation, it offers not only new avenues for drug development but also a framework for probing how biological systems encode and transmit regulatory information across molecular scales [

78].

Funding

This study is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12474192), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LZ24A040002), Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics (No. 2023BNLCMPKF009), Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Soft Matter Biomedical Materials (No. 2025ZY01036, 2025E10072) and Wenzhou Institute, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. WIUCASQD2022019).

References

- Fenton, A.W. Allostery: an illustrated definition for the ‘second secret of life’. Trends in biochemical sciences 2008, 33, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astore, M.A.; Pradhan, A.S.; Thiede, E.H.; Hanson, S.M. Protein dynamics underlying allosteric regulation. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2024, 84, 102768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, T.; Christopoulos, A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2013, 12, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannes, M.; Martin, C.; Menet, C.; Ballet, S. Wandering beyond small molecules: peptides as allosteric protein modulators. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2022, 43, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.M.; Traynor, J.R.; Alt, A. Allosteric modulator leads hiding in plain site: Developing peptide and peptidomimetics as GPCR allosteric modulators. Frontiers in Chemistry 2021, 9, 671483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, L.; Guarnera, E.; Kolmar, H.; Becker, S. Allosteric antibodies: a novel paradigm in drug discovery. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2025, 46, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, G.; Keskin, O.; Gursoy, A.; Nussinov, R. Allostery and population shift in drug discovery. Current opinion in pharmacology 2010, 10, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, J. Funneled energy landscape unifies principles of protein binding and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 27218–27223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Tao, X.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y. Binding Specificity and Local Frustration in Structure-based Drug Discovery. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R. Introduction to protein ensembles and allostery. Chemical reviews 2016, 116, 6263–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.; Hempel, T.; Jiménez-Luna, J.; Gastegger, M.; Xie, Y.; Foong, A.Y.; Satorras, V.G.; Abdin, O.; Veeling, B.S.; Zaporozhets, I.; et al. Scalable emulation of protein equilibrium ensembles with generative deep learning. Science 2025, 389, eadv9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Zhao, C.; Wu, C.; Sun, S.; Li, Z.; Yan, W.; Shao, Z. Allosteric modulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14, 1137604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzigoulas, A.; Cournia, Z. Rational design of allosteric modulators: Challenges and successes. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Molecular Science 2021, 11, e1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asada, N.; Krebs, C.F.; Panzer, U. Miniproteins may have a big impact: new therapeutics for autoimmune diseases and beyond. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, S.; Xu, J.; N. Kadji, F.M.; Clark, M.J.; Zhao, J.; Tsutsumi, N.; Aoki, J.; Sunahara, R.K.; Inoue, A.; Garcia, K.C.; et al. Structure and selectivity engineering of the M1 muscarinic receptor toxin complex. Science 2020, 369, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Goreshnik, I.; Coventry, B.; Case, J.B.; Miller, L.; Kozodoy, L.; Chen, R.E.; Carter, L.; Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; et al. De novo design of picomolar SARS-CoV-2 miniprotein inhibitors. Science 2020, 370, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.; Seeger, F.; Yu, T.Y.; Aydin, M.; Yang, H.; Rosenblum, D.; Guenin-Macé, L.; Glassman, C.; Arguinchona, L.; Sniezek, C.; et al. Preclinical proof of principle for orally delivered Th17 antagonist miniproteins. Cell 2024, 187, 4305–4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Shi, L.; Chang, A.; Dong, X.; Fernandez, A.; Kraft, J.C.; Li, J.; Le, V.Q.; Winegar, R.V.; Cherf, G.M.; et al. De novo design of highly selective miniprotein inhibitors of integrins αvβ6 and αvβ8. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 5660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinov, R.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Jang, H. AlphaFold, artificial intelligence (AI), and allostery. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2022, 126, 6372–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agajanian, S.; Alshahrani, M.; Bai, F.; Tao, P.; Verkhivker, G.M. Exploring and learning the universe of protein allostery using artificial intelligence augmented biophysical and computational approaches. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2023, 63, 1413–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Verkhivker, G.M.; Tao, P. Machine learning and protein allostery. Trends in biochemical sciences 2023, 48, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tang, G.; Liu, N.; Li, X.; Lu, S. Recent advances in computational strategies for allosteric site prediction: Machine learning, molecular dynamics, and network-based approaches. Drug Discovery Today 2025, 104466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, M.; Arora, R.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S.; Li, L.; Church, G.M. AI-driven protein design. Nature Reviews Bioengineering 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchiba, Y.; Ruffini, M.; Schiex, T.; Barbe, S. Computational design of miniprotein binders. In Computational Peptide Science: Methods and Protocols; Springer, 2022; pp. 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Ożga, K.; Berlicki, Ł. Design and engineering of miniproteins. ACS bio & med Chem Au 2022, 2, 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Kortemme, T. De novo protein design—From new structures to programmable functions. Cell 2024, 187, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.R.; Taveneau, C.; Clement, J.; Grinter, R.; Knott, G.J. Code to complex: AI-driven de novo binder design. Structure 2025, 33, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Wu, C.; Zha, J.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J. Decoding allosteric landscapes: computational methodologies for enzyme modulation and drug discovery. RSC Chemical Biology 2025, 6, 539–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Kelly, B.; Valant, C.; Michaelis, J.A.; Mastromihalis, O.; Thompson, G.; Venkatakrishnan, A.; Hertig, S.; Scammells, P.J.; Sexton, P.M.; et al. Cryptic pocket formation underlies allosteric modulator selectivity at muscarinic GPCRs. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemelmans, M.P.; Cournia, Z.; Damm-Ganamet, K.L.; Gervasio, F.L.; Pande, V. Computational advances in discovering cryptic pockets for drug discovery. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2025, 90, 102975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein, J.; Han, X.; Levkovets, M.; Lesovoy, D.; Malmodin, D.; Mirabello, C.; Wallner, B.; Sun, R.; Sandalova, T.; Agback, P.; et al. Insights into mechanisms of MALT1 allostery from NMR and AlphaFold dynamic analyses. Communications biology 2024, 7, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; He, X.H.; Li, S.J.; Xu, H.E. Cryo-electron microscopy for GPCR research and drug discovery in endocrinology and metabolism. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2024, 20, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Lu, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Mou, L.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Hou, T.; et al. Allosite: a method for predicting allosteric sites. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2357–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.G.; Sternberg, M.J. AlloPred: prediction of allosteric pockets on proteins using normal mode perturbation analysis. BMC bioinformatics 2015, 16, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Lu, S.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J. Improved method for the identification and validation of allosteric sites. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2017, 57, 2358–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Jiang, X.; Tao, P. PASSer: Prediction of allosteric sites server. Machine learning: science and technology 2021, 2, 035015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tian, H.; Tao, P. PASSer2. 0: accurate prediction of protein allosteric sites through automated machine learning. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2022, 9, 879251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Xiao, S.; Jiang, X.; Tao, P. PASSerRank: Prediction of allosteric sites with learning to rank. Journal of computational chemistry 2023, 44, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugurlu, S.Y.; McDonald, D.; He, S. Mef-allosite: An accurate and robust multimodel ensemble feature selection for the allosteric site identification model. Journal of Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nerin-Fonz, F.; Cournia, Z. Machine learning approaches in predicting allosteric sites. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2024, 85, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; He, X.; Wu, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, J. Advances in structure-based allosteric drug design. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2025, 90, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Doruker, P.; Li, H.; Demet Akten, E. Understanding protein dynamics, binding and allostery for drug design. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; Wang, J.; Cong, Q.; Kinch, L.N.; Schaeffer, R.D.; et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Su, H.; Wang, W.; Ye, L.; Wei, H.; Peng, Z.; Anishchenko, I.; Baker, D.; Yang, J. The trRosetta server for fast and accurate protein structure prediction. Nature protocols 2021, 16, 5634–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; O’Neill, M.; Pritzel, A.; Antropova, N.; Senior, A.; Green, T.; Žídek, A.; Bates, R.; Blackwell, S.; Yim, J.; et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. biorxiv 2021, 2021–10. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K.; Yang, J. A comprehensive application of FiveFold for conformation ensemble-based protein structure prediction. Scientific Reports 2025, 15, 33498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ge, L.; Chen, X.; Lv, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, G. Beyond static structures: protein dynamic conformations modeling in the post-AlphaFold era. Briefings in bioinformatics 2025, 26, bbaf340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnifrith, A.; Outeiral, C.; Hie, B. Generative artificial intelligence for de novo protein design. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U. Generative AI for drug discovery and protein design: the next frontier in AI-driven molecular science. Medicine in Drug Discovery 2025, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.L.; Juergens, D.; Bennett, N.R.; Trippe, B.L.; Yim, J.; Eisenach, H.E.; Ahern, W.; Borst, A.J.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; et al. De novo design of protein structure and function with RFdiffusion. Nature 2023, 620, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, W.; Yim, J.; Tischer, D.; Salike, S.; Woodbury, S.M.; Kim, D.; Kalvet, I.; Kipnis, Y.; Coventry, B.; Altae-Tran, H.R.; et al. Atom-level enzyme active site scaffolding using RFdiffusion2. Nature Methods 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, J.; Krishna, R.; Mitra, R.; Brent, R.I.; Li, Y.; Corley, N.; Kim, P.T.; Funk, J.; Mathis, S.; Salike, S.; et al. De novo design of all-atom biomolecular interactions with rfdiffusion3. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.J.; Akhound-Sadegh, T.; Huguet, G.; Fatras, K.; Rector-Brooks, J.; Liu, C.H.; Nica, A.C.; Korablyov, M.; Bronstein, M.; Tong, A. Se (3)-stochastic flow matching for protein backbone generation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.02391. [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham, J.B.; Baranov, M.; Costello, Z.; Barber, K.W.; Wang, W.; Ismail, A.; Frappier, V.; Lord, D.M.; Ng-Thow-Hing, C.; Van Vlack, E.R.; et al. Illuminating protein space with a programmable generative model. Nature 2023, 623, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauparas, J.; Anishchenko, I.; Bennett, N.; Bai, H.; Ragotte, R.J.; Milles, L.F.; Wicky, B.I.; Courbet, A.; de Haas, R.J.; Bethel, N.; et al. Robust deep learning–based protein sequence design using ProteinMPNN. Science 2022, 378, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Tan, C.; Chacón, P.; Li, S.Z. Pifold: Toward effective and efficient protein inverse folding. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.12643. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.; Verkuil, R.; Liu, J.; Lin, Z.; Hie, B.; Sercu, T.; Lerer, A.; Rives, A. Learning inverse folding from millions of predicted structures. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2022; pp. 8946–8970. [Google Scholar]

- Zambaldi, V.; La, D.; Chu, A.E.; Patani, H.; Danson, A.E.; Kwan, T.O.; Frerix, T.; Schneider, R.G.; Saxton, D.; Thillaisundaram, A.; et al. De novo design of high-affinity protein binders with AlphaProteo. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2409.08022. [CrossRef]

- Jendrusch, M.A.; Yang, A.L.; Cacace, E.; Bobonis, J.; Voogdt, C.G.; Kaspar, S.; Schweimer, K.; Perez-Borrajero, C.; Lapouge, K.; Scheurich, J.; et al. AlphaDesign: A de novo protein design framework based on AlphaFold. Molecular Systems Biology 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, O.; Zhang, X.; Lin, H.; Tan, C.; Wang, Q.; Mo, Y.; Feng, Q.; Du, G.; Yu, Y.; Jin, Z.; et al. ODesign: A World Model for Biomolecular Interaction Design. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.22304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacesa, M.; Nickel, L.; Schellhaas, C.; Schmidt, J.; Pyatova, E.; Kissling, L.; Barendse, P.; Choudhury, J.; Kapoor, S.; Alcaraz-Serna, A.; et al. BindCraft: one-shot design of functional protein binders. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, H.; Faltings, F.; Choi, M.; Xie, Y.; Hur, E.; O’Donnell, T.J.; Bushuiev, A.; Uçar, T.; Passaro, S.; Mao, W.; et al. BoltzGen: Toward Universal Binder Design. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Sun, J.; Guan, J.; Liu, C.; Gong, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Cai, Q.; Chen, X.; Xiao, W.; et al. Pxdesign: Fast, modular, and accurate de novo design of protein binders. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, T.; Li, L.; Min, M.R. PPDiff: Diffusing in Hybrid Sequence-Structure Space for Protein-Protein Complex Design. arXiv arXiv:2506.11420.

- Bennett, N.R.; Coventry, B.; Goreshnik, I.; Huang, B.; Allen, A.; Vafeados, D.; Peng, Y.P.; Dauparas, J.; Baek, M.; Stewart, L.; et al. Improving de novo protein binder design with deep learning. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jussupow, A.; Kaila, V.R. Effective molecular dynamics from neural network-based structure prediction models. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2023, 19, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Baker, D. Macromolecular modeling with rosetta. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 363–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgrignani, J.; Buscarini, S.; Locatelli, P.; Guerra, C.; Furlan, A.; Chen, Y.; Zoppi, G.; Cavalli, A. AI assisted design of ligands for Lipocalin-2. bioRxiv 2025, 2025–05. [CrossRef]

- Gokce-Alpkilic, G.; Huang, B.; Liu, A.; Kreuk, L.S.; Wang, Y.; Adebomi, V.; Bueso, Y.F.; Bera, A.K.; Kang, A.; Gerben, S.R.; et al. De Novo Design of High-Affinity Miniprotein Binders Targeting Francisella Tularensis Virulence Factor. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2025, e202516058. [Google Scholar]

- Chazin-Gray, A.M.; Thompson, T.R.; Lopatto, E.D.; Magala, P.; Erickson, P.W.; Hunt, A.C.; Manchenko, A.; Aprikian, P.; Tchesnokova, V.; Basova, I.; et al. De Novo Design of Miniprotein Inhibitors of Bacterial Adhesins. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heling, L.W.; van der Veen, J.; Rofe, A.; West, E.; Jiménez-Panizo, A.; Alegre-Martí, A.; Sheikhhassani, V.; Ng, J.; Schmidt, T.; Estébanez-Perpiñá, E.; et al. Deciphering the allosteric control of androgen receptor DNA binding by its disordered N-terminal domain. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2025, 112634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraj, R.G.; Thangapandian, S.; Schauperl, M.; Denny, R.A.; Diller, D.J. Recent applications of computational methods to allosteric drug discovery. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2023, 9, 1070328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Labroska, V.; Qin, S.; Darbalaei, S.; Wu, Y.; Yuliantie, E.; Xie, L.; Tao, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. G protein-coupled receptors: structure-and function-based drug discovery. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, M.N.; Person, K.L.; Robleto, V.L.; Alwin, A.R.; Krusemark, C.L.; Foster, N.; Ray, C.; Inoue, A.; Jackson, M.R.; Sheedlo, M.J.; et al. Designing allosteric modulators to change GPCR G protein subtype selectivity. Nature 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meijer, F.A.; Leijten-van de Gevel, I.A.; de Vries, R.M.; Brunsveld, L. Allosteric small molecule modulators of nuclear receptors. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 2019, 485, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Hawkins, B.A.; Du, J.J.; Groundwater, P.W.; Hibbs, D.E.; Lai, F. A guide to in silico drug design. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).