Submitted:

23 July 2025

Posted:

24 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Problem Statement

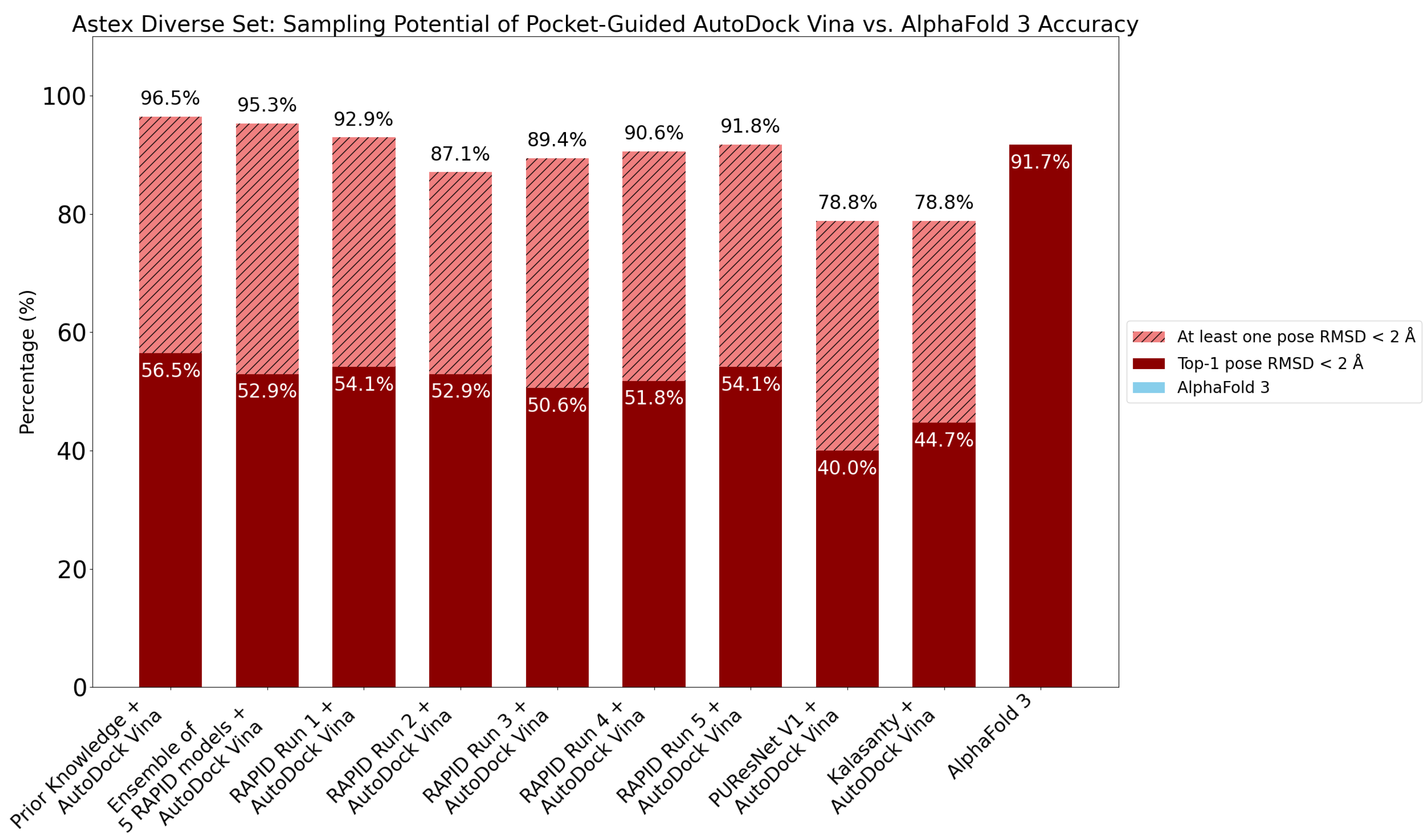

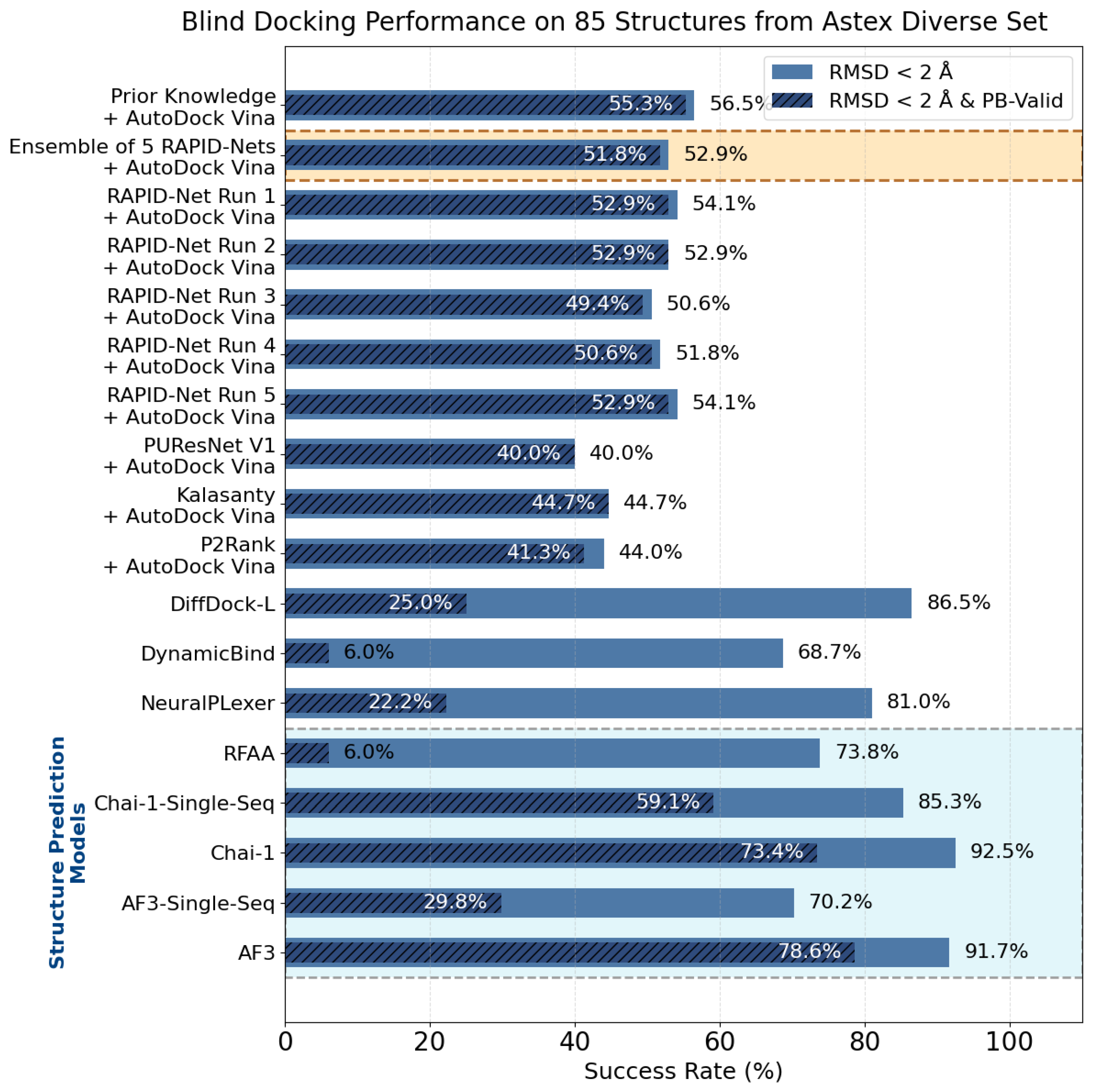

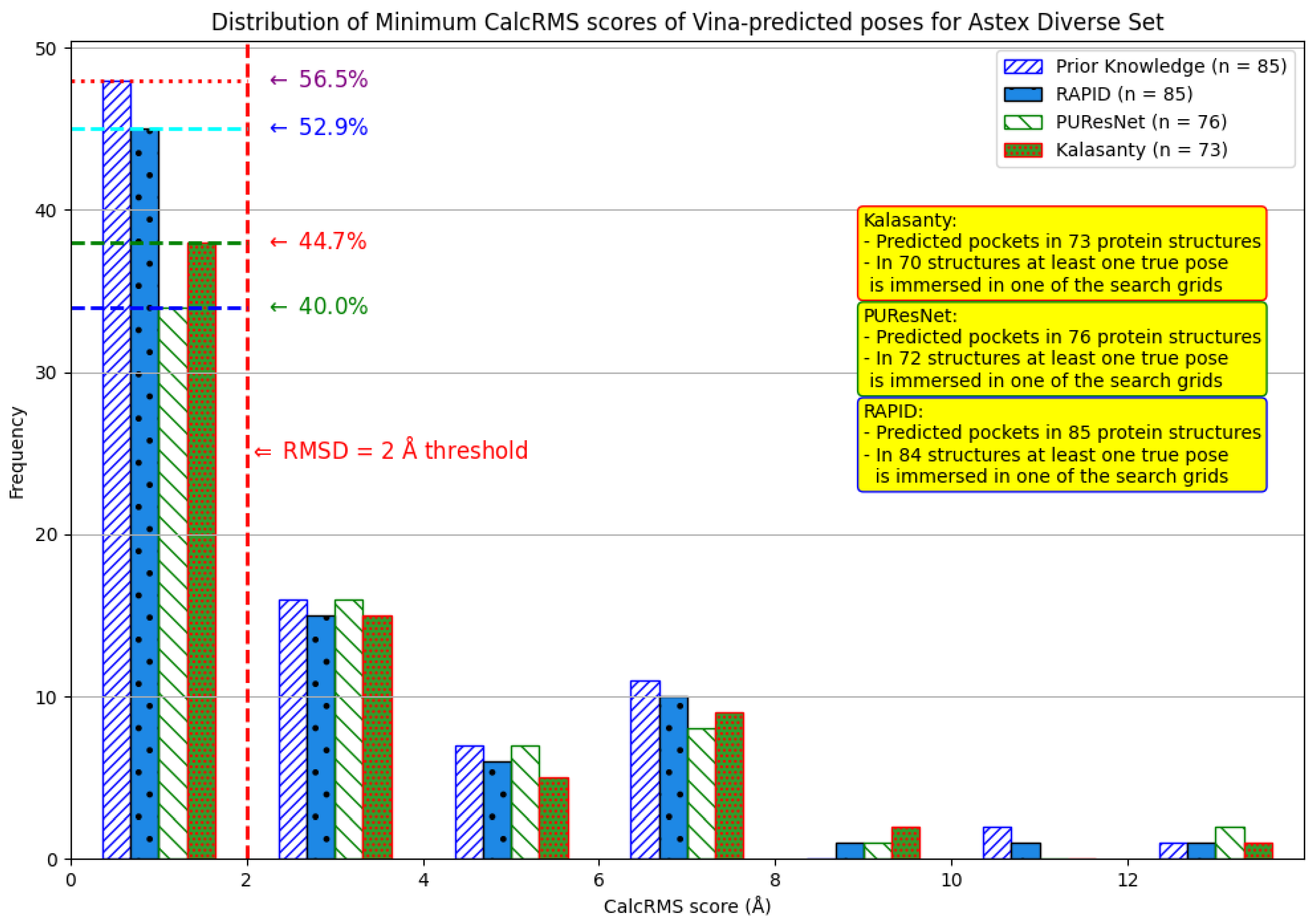

2. Overview of the Available Pocket Prediction Algorithms

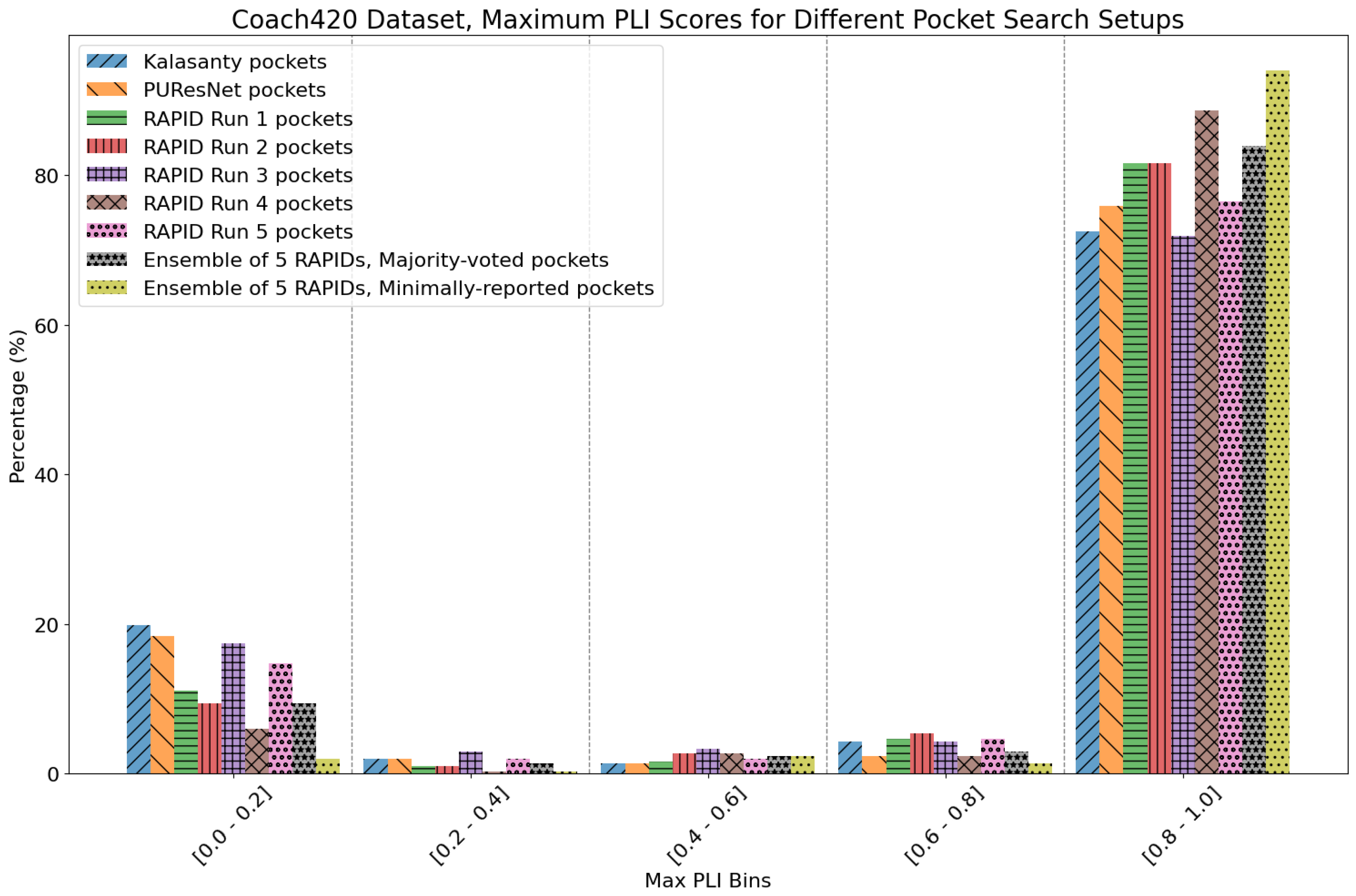

3. Design Rationale behind our Model

- Majority-voted pockets: Consisting of voxels predicted by at least 3 out of 5 ensemble models, for high-confidence predictions.

- Minority-reported pockets: Consisting of voxels predicted by at least 1 out of 5 ensemble models, increasing the overall recall.

4. Model Training and Inference Pipeline

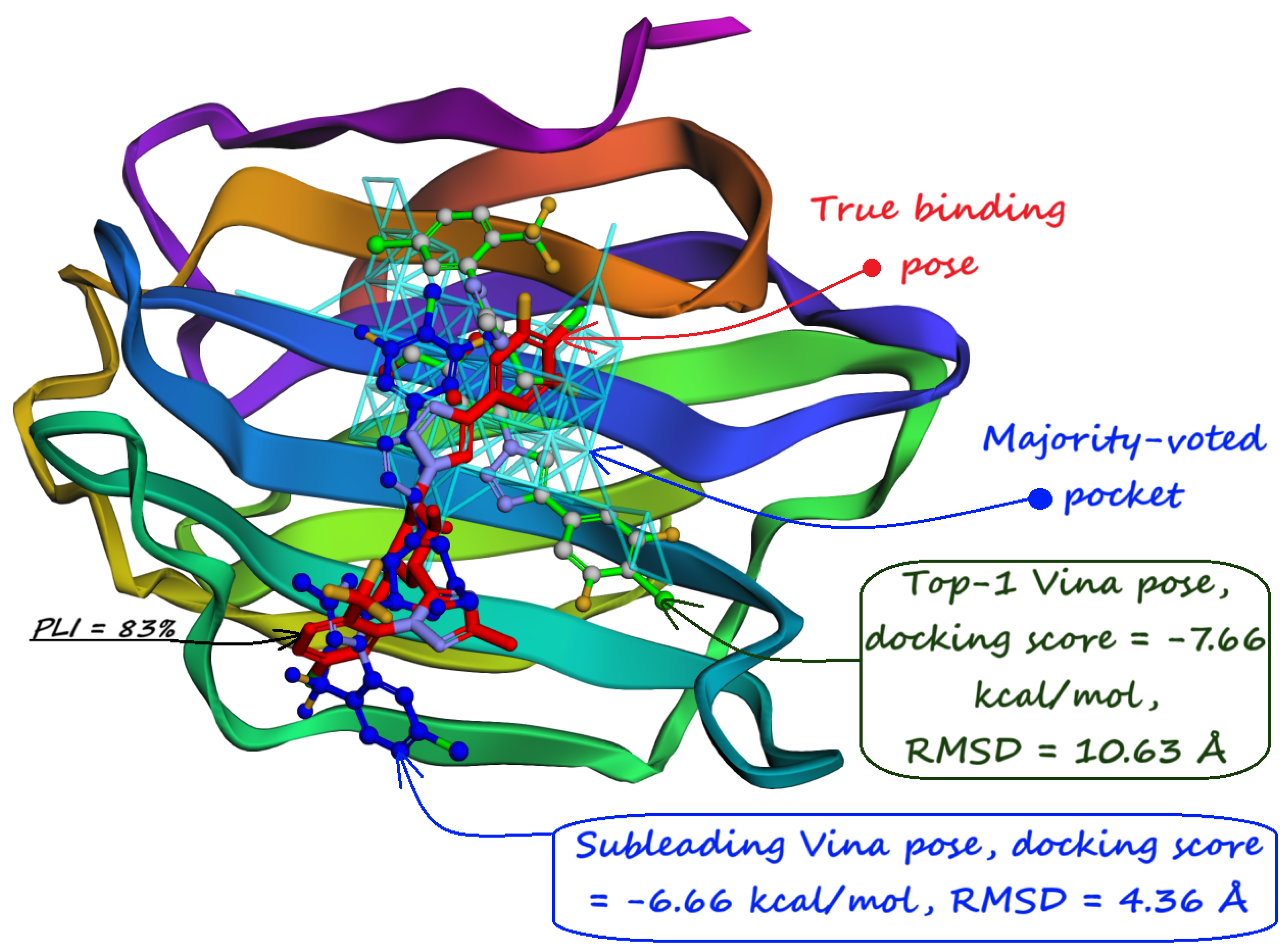

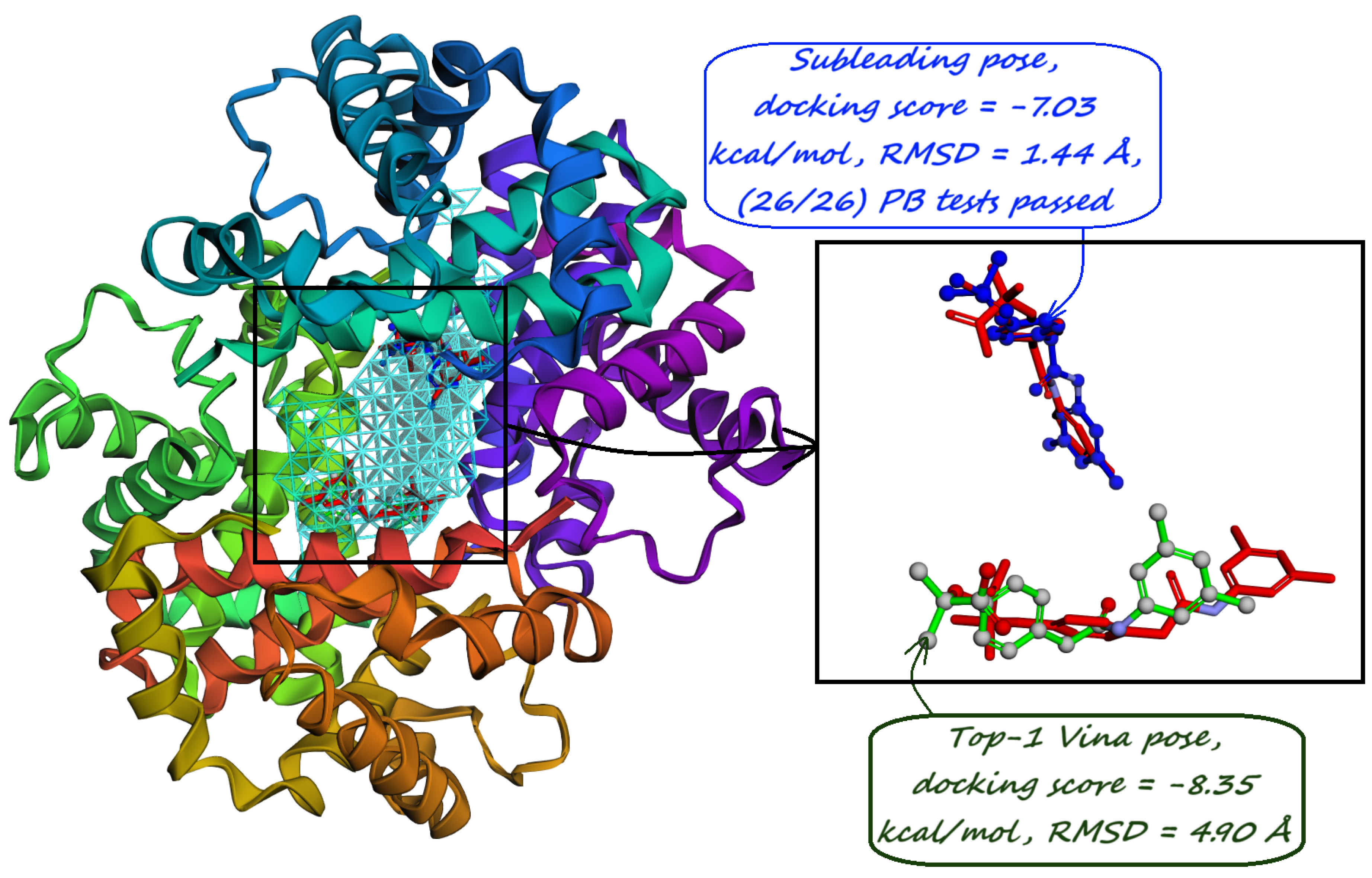

5. Pocket-informed Docking Protocol and its Rationale

6. Test Benchmarks and Evaluation Metrics

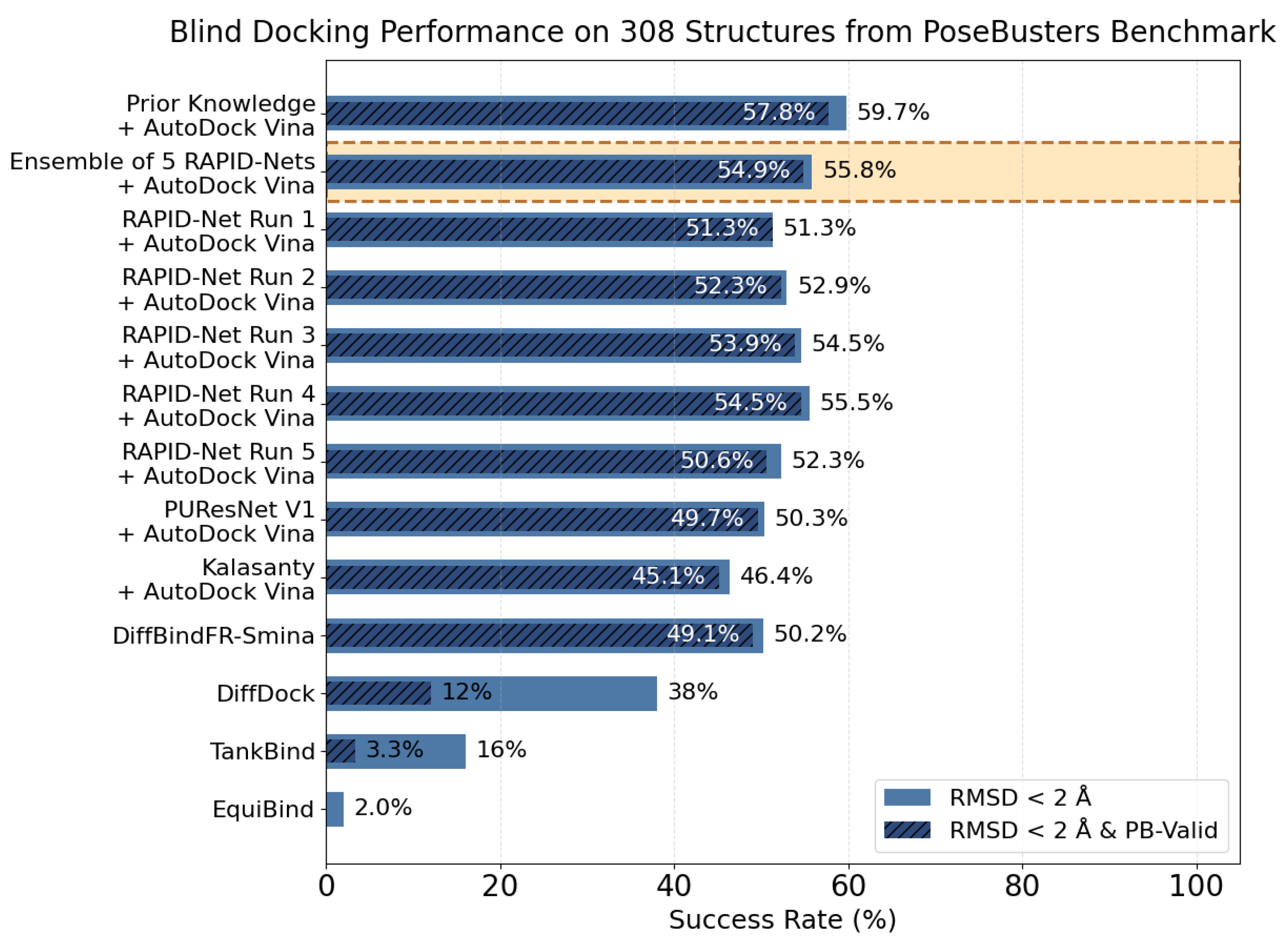

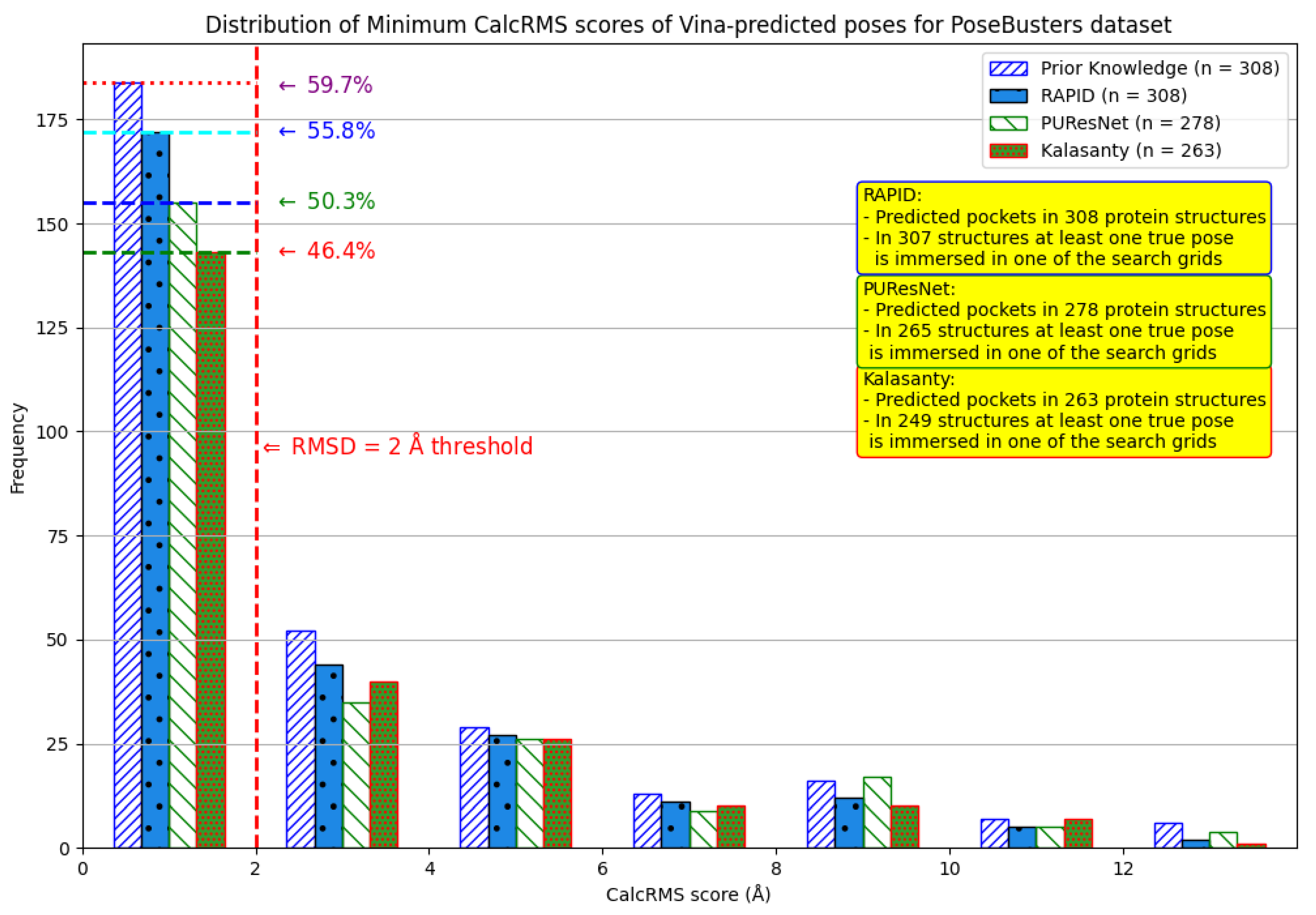

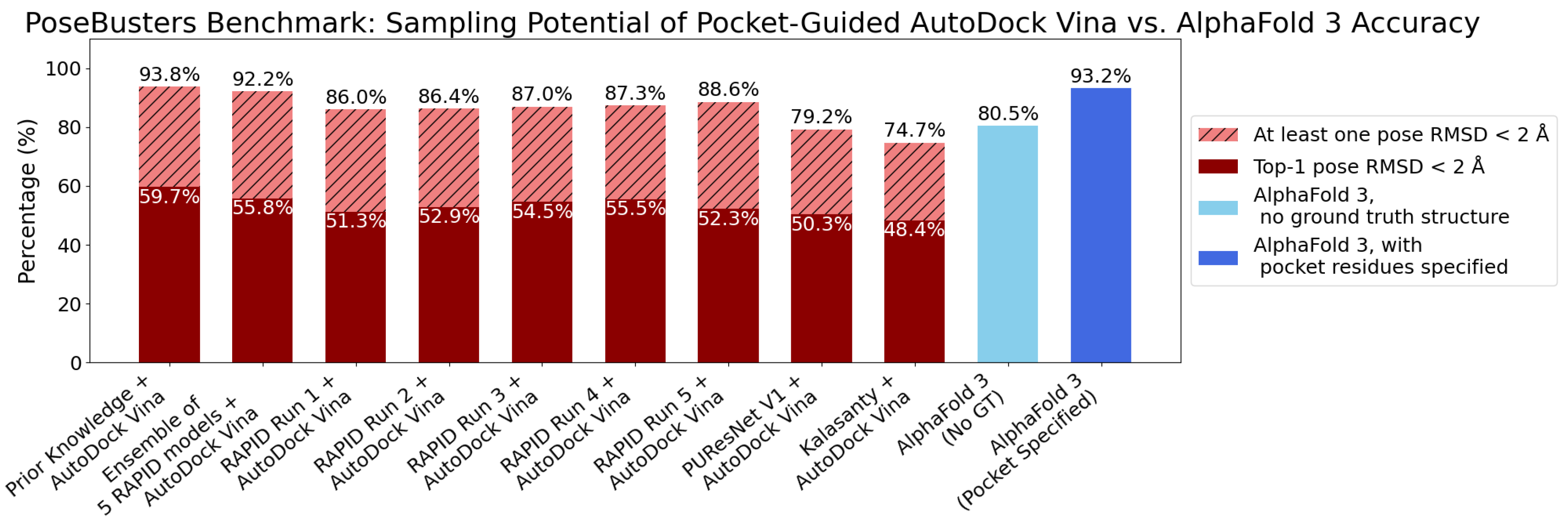

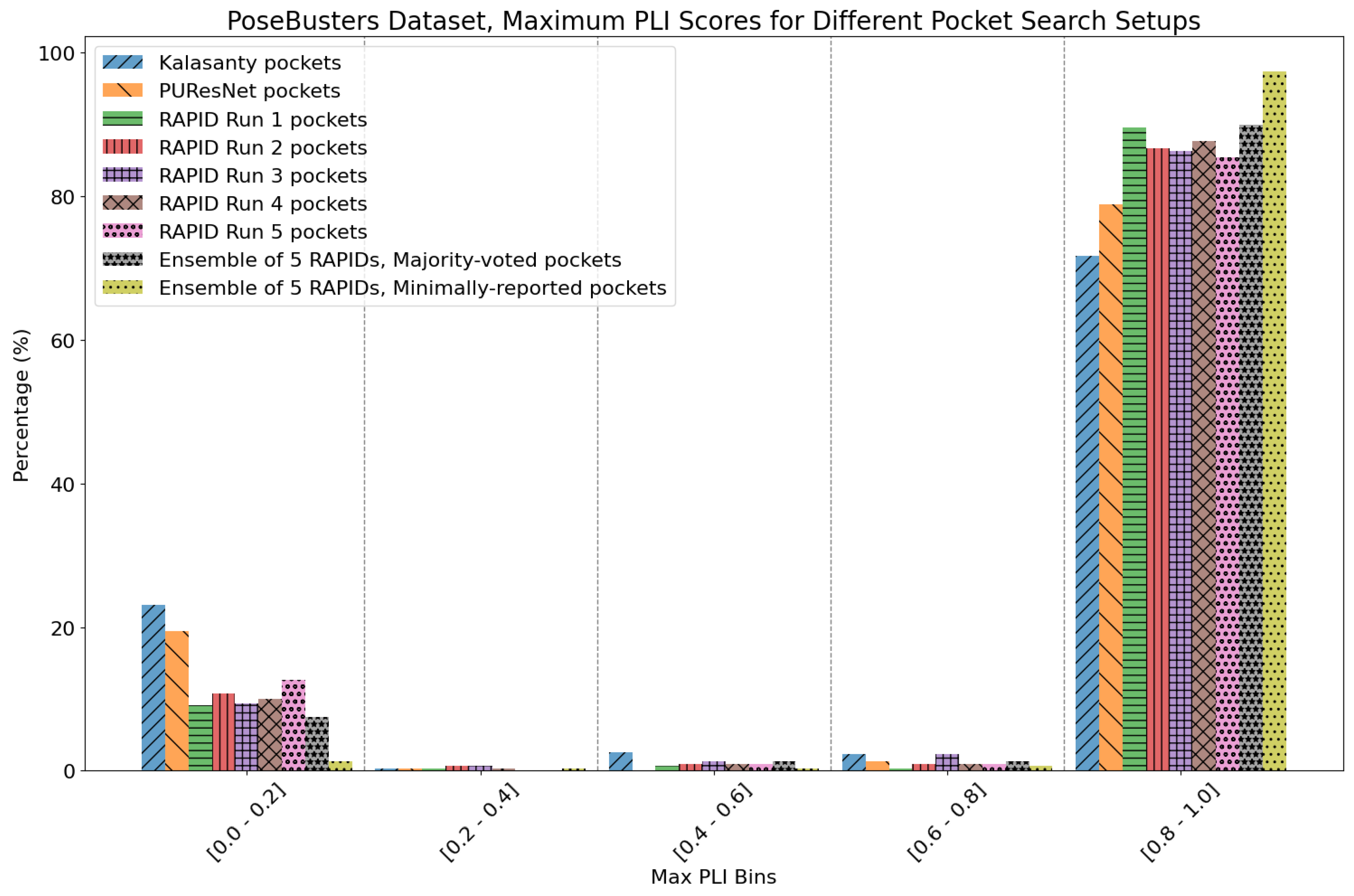

7. Evaluation on the PoseBusters Dataset

- The number of protein structures with at least one predicted pocket (shown in the “Nonzero” column). Since no protein in all our datasets is a true negative, failure to predict any pocket for a given structure is automatically an incorrect prediction.

- The number of structures with viable search grids encompassing at least one true ligand binding pose (“Within ” column), where the docking may succeed.

- The average Pocket-Ligand Intersection (PLI) value for all protein structures.

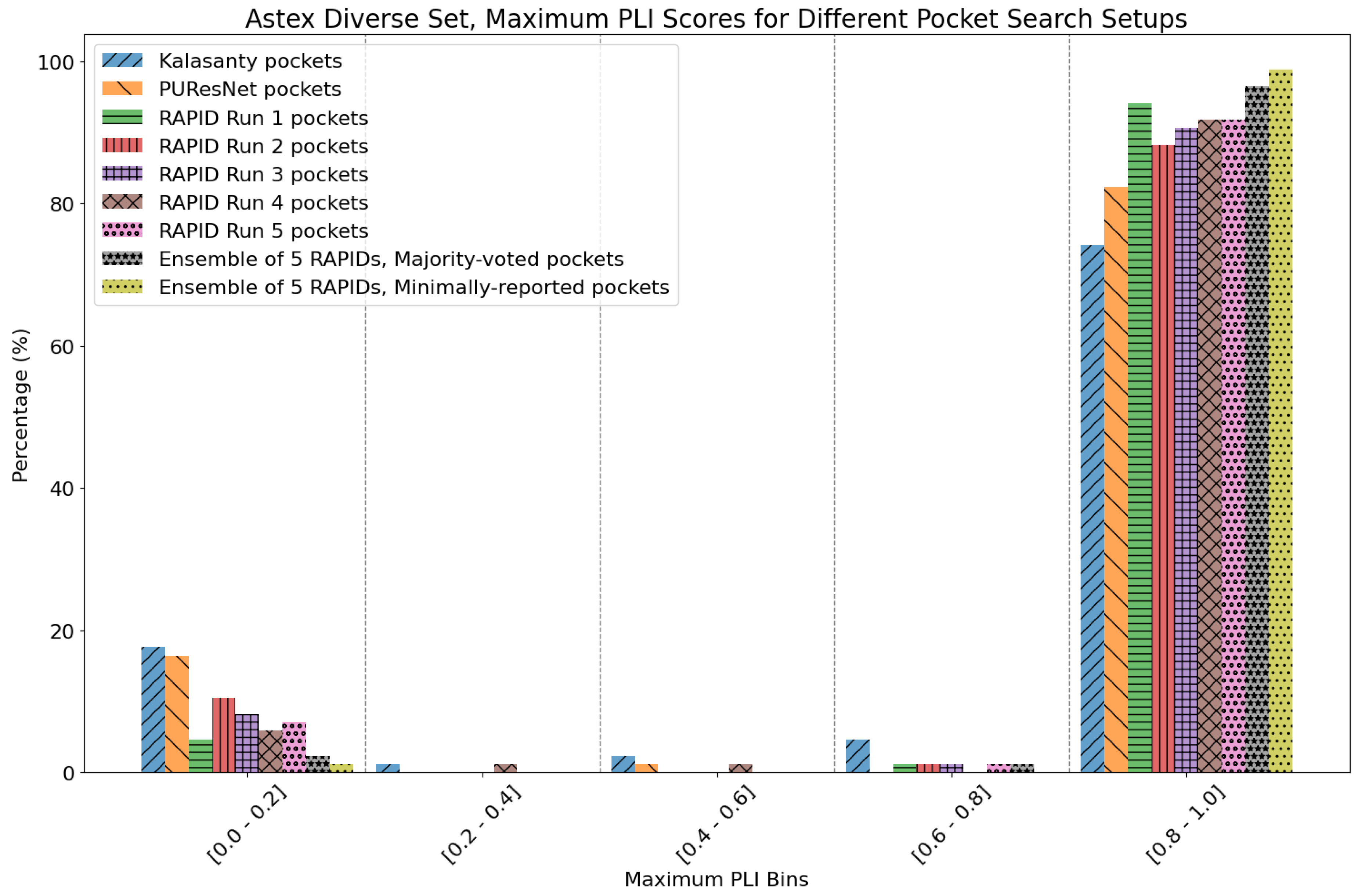

8. Evaluation on the Astex Diverse Set

9. Evaluation on Coach420 and BU48 Datasets

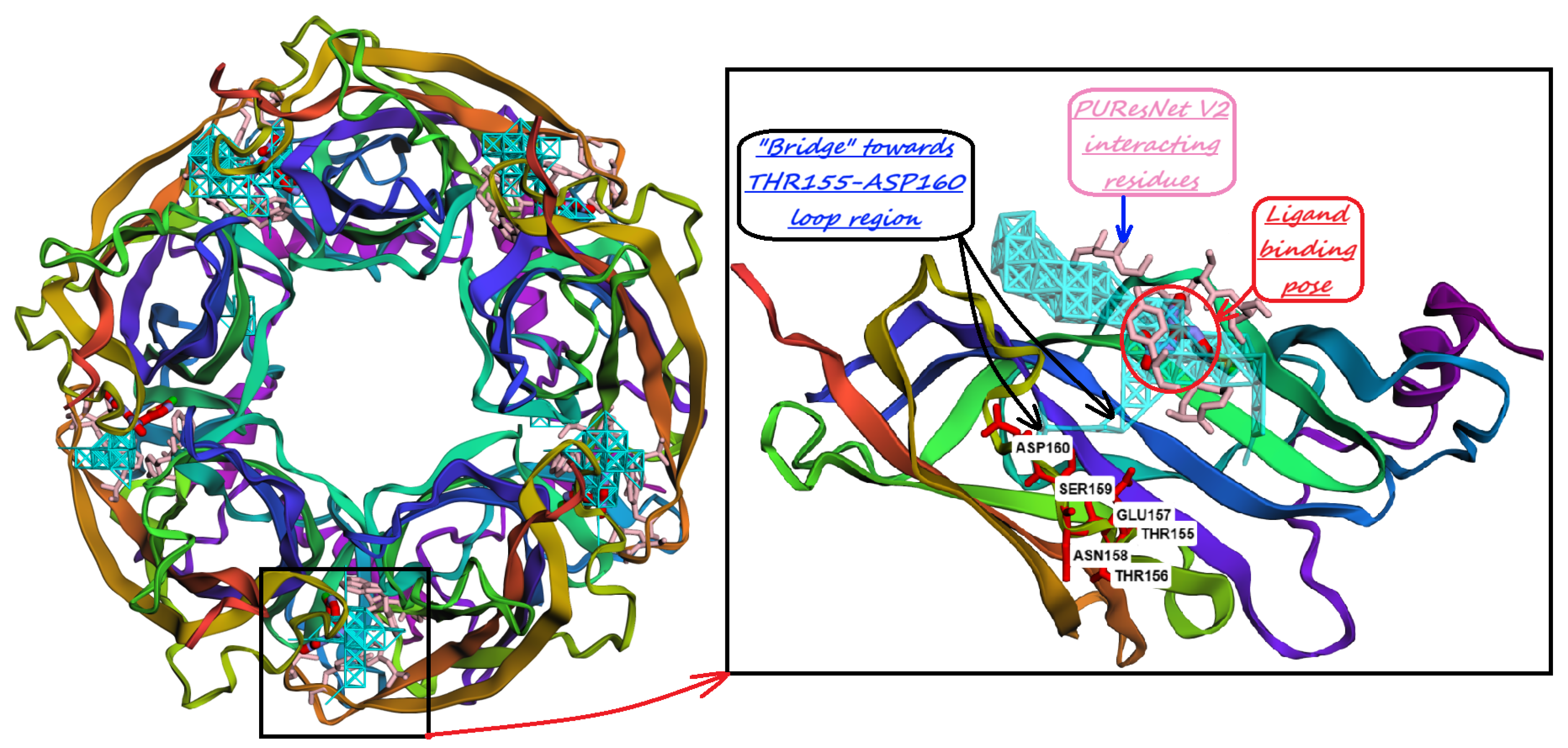

10. Identification of Allosteric Sites, Exosites, and Flexible Regions for Drug Design

11. Discussion and Conclusions

- Soft Labeling and ReLU Activation: Unlike conventional binary segmentation tasks, we applied soft labels and ReLU activation in the output layer, drawing inspiration from medical image segmentation techniques. This approach enables the model to more effectively differentiate between the internal regions of pockets and their boundaries.

- Attention Mechanism: We integrated a single attention block within the encoder-decoder bottleneck, enhancing the model’s ability to focus on relevant features while reducing the risk of overfit in inherently noisy data environments.

- Simplified Architecture: By eliminating excessive residual connections, we streamlined the model architecture, resulting in improved performance. This simplification was effective given the noisy nature of the dataset.

Usage of Our Model and Reproducibility of Results

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kukol, A.; et al. Molecular modeling of proteins; Vol. 443, Springer, 2008.

- An, J.; Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R. Comprehensive identification of “druggable” protein ligand binding sites. Genome Informatics 2004, 15, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Ruyck, J.; Brysbaert, G.; Blossey, R.; Lensink, M.F. Molecular docking as a popular tool in drug design, an in silico travel. Advances and Applications in Bioinformatics and Chemistry 2016, pp. 1–11.

- Rezaei, M.A.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Li, C. Deep learning in drug design: protein-ligand binding affinity prediction. IEEE/ACM transactions on computational biology and bioinformatics 2020, 19, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamathevan, J.; Clark, D.; Czodrowski, P.; Dunham, I.; Ferran, E.; Lee, G.; Li, B.; Madabhushi, A.; Shah, P.; Spitzer, M.; et al. Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2019, 18, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, S.; Bordoloi, M. Molecular docking: challenges, advances and its use in drug discovery perspective. Current drug targets 2019, 20, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoete, V.; Grosdidier, A.; Michielin, O. Docking, virtual high throughput screening and in silico fragment-based drug design. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2009, 13, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionta, E.; Spyrou, G.; K Vassilatis, D.; Cournia, Z. Structure-based virtual screening for drug discovery: principles, applications and recent advances. Current topics in medicinal chemistry 2014, 14, 1923–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, G.L. An introduction to medicinal chemistry; Oxford university press, 2023.

- Hernández-Santoyo, A.; Tenorio-Barajas, A.Y.; Altuzar, V.; Vivanco-Cid, H.; Mendoza-Barrera, C. Protein-protein and protein-ligand docking. Protein engineering-technology and application 2013, pp. 63–81.

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A.F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2. 0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2021, 61, 3891–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdonk, M.L.; Cole, J.C.; Hartshorn, M.J.; Murray, C.W.; Taylor, R.D. Improved protein–ligand docking using GOLD. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2003, 52, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesner, R.A.; Banks, J.L.; Murphy, R.B.; Halgren, T.A.; Klicic, J.J.; Mainz, D.T.; Repasky, M.P.; Knoll, E.H.; Shelley, M.; Perry, J.K.; et al. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, G.; Di Gregorio, A.; Mavkov, B.; Piga, D.; Labate, G.F.D.; Danani, A.; Deriu, M.A. Fragmented blind docking: a novel protein–ligand binding prediction protocol. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2022, 40, 13472–13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.M.; Alhossary, A.A.; Mu, Y.; Kwoh, C.K. Protein-ligand blind docking using QuickVina-W with inter-process spatio-temporal integration. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 15451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koes, D.R.; Baumgartner, M.P.; Camacho, C.J. Lessons learned in empirical scoring with smina from the CSAR 2011 benchmarking exercise. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2013, 53, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Predicting protein structure from single sequences. Nature Computational Science 2022, 2, 775–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nature methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahdritz, G.; Bouatta, N.; Floristean, C.; Kadyan, S.; Xia, Q.; Gerecke, W.; O’Donnell, T.J.; Berenberg, D.; Fisk, I.; Zanichelli, N.; et al. OpenFold: Retraining AlphaFold2 yields new insights into its learning mechanisms and capacity for generalization. Nature Methods 2024, pp. 1–11.

- Baek, M.; DiMaio, F.; Anishchenko, I.; Dauparas, J.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Lee, G.R.; Wang, J.; Cong, Q.; Kinch, L.N.; Schaeffer, R.D.; et al. Accurate prediction of protein structures and interactions using a three-track neural network. Science 2021, 373, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overington, J.P.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hopkins, A.L. How many drug targets are there? Nature reviews Drug discovery 2006, 5, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.; Ursu, O.; Gaulton, A.; Bento, A.P.; Donadi, R.S.; Bologa, C.G.; Karlsson, A.; Al-Lazikani, B.; Hersey, A.; Oprea, T.I.; et al. A comprehensive map of molecular drug targets. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2017, 16, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, S.; Yue, D.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.Q. DSDP: a blind docking strategy accelerated by GPUs. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2023, 63, 4355–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utgés, J.S.; Barton, G.J. Comparative evaluation of methods for the prediction of protein–ligand binding sites. Journal of Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Gu, Z.; Pei, J.; Lai, L. DiffBindFR: an SE(3) equivariant network for flexible protein-ligand docking. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 7926–7942, Supplementary information available: PDF (1982K). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttenschoen, M.; Morris, G.M.; Deane, C.M. PoseBusters: AI-based docking methods fail to generate physically valid poses or generalise to novel sequences. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 3130–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Huang, Y.P.; Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.Q. DSDPFlex: Flexible-Receptor Docking with GPU Acceleration. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2024, 64, 5252–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Jumper, J.M. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, pp. 1–3.

- Morehead, A.; Giri, N.; Liu, J.; Neupane, P.; Cheng, J. Deep Learning for Protein-Ligand Docking: Are We There Yet? In Proceedings of the ICML AI4Science Workshop, 2024. selected as a spotlight presentation.

- Chollet, F. Deep learning with Python; Simon and Schuster, 2021.

- Hartshorn, M.J.; Verdonk, M.L.; Chessari, G.; Brewerton, S.C.; Mooij, W.T.; Mortenson, P.N.; Murray, C.W. Diverse, high-quality test set for the validation of protein- ligand docking performance. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2007, 50, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y. COFACTOR: An Accurate Comparative Algorithm for Structure-Based Protein Function Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W471–W477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Schroeder, M. LIGSITE csc: predicting ligand binding sites using the Connolly surface and degree of conservation. BMC Structural Biology 2006, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Guilloux, V.; Schmidtke, P.; Tufféry, P. Fpocket: An Open Source Platform for Ligand Pocket Detection. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendlich, M.; Rippmann, F.; Barnickel, G. LIGSITE: Automatic and Efficient Detection of Potential Small Molecule-Binding Sites in Proteins. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 1997, 15, 359–363, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A. SURFNET: A Program for Visualizing Molecular Surfaces, Cavities, and Intermolecular Interactions. J. Mol. Graph. 1995, 13, 323–330, 307–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, D.G.; Banaszak, L.J. POCKET: A Computer Graphics Method for Identifying and Displaying Protein Cavities and Their Surrounding Amino Acids. J. Mol. Graph. 1992, 10, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleywegt, G.J.; Jones, T.A. Detection, Delineation, Measurement and Display of Cavities in Macromolecular Structures. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1994, 50, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Edelsbrunner, H.; Woodward, C. Anatomy of Protein Pockets and Cavities: Measurement of Binding Site Geometry and Implications for Ligand Design. Protein Sci. 1998, 7, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, G.P.J.; Stouten, P.F. Fast Prediction and Visualization of Protein Binding Pockets with PASS. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2000, 14, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, M.; Proschak, E.; Schneider, G. PocketPicker: Analysis of Ligand Binding-Sites with Shape Descriptors. Chem. Cent. J. 2007, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R. Pocketome via Comprehensive Identification and Classification of Ligand Binding Envelopes. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2005, 4, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodford, P.J. A Computational Procedure for Determining Energetically Favorable Binding Sites on Biologically Important Macromolecules. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Totrov, M.; Abagyan, R. Comprehensive Identification of “Druggable” Protein Ligand Binding Sites. Genome Inform. 2004, 15, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie, A.T.R.; Jackson, R.M. Q-SiteFinder: An Energy-Based Method for the Prediction of Protein–Ligand Binding Sites. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghersi, D.; Sanchez, R. EasyMIFS and SiteHound: A Toolkit for the Identification of Ligand-Binding Sites in Protein Structures. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 3185–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, C.H.; Bohnuud, T.; Mottarella, S.E.; Beglov, D.; Villar, E.A.; Hall, D.R.; Vajda, S. FTSite: High Accuracy Detection of Ligand Binding Sites on Unbound Protein Structures. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon, A.; Graur, D.; Ben-Tal, N. ConSurf: An Algorithmic Tool for the Identification of Functional Regions in Proteins by Surface Mapping of Phylogenetic Information. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 307, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupko, T.; Bell, R.E.; Mayrose, I.; Glaser, F.; Ben-Tal, N. Rate4Site: An Algorithmic Tool for the Identification of Functional Regions in Proteins by Surface Mapping of Evolutionary Determinants Within Their Homologues. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, S71–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.R.; Hwang, M.J. Ligand-Binding Site Prediction Using Ligand-Interacting and Binding Site-Enriched Protein Triangles. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil, M.J.; Barton, G.J.; Taylor, W.R.; Sternberg, M.J.E. Prediction of Protein Secondary Structure and Active Sites Using the Alignment of Homologous Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 195, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wass, M.N.; Kelley, L.A.; Sternberg, M.J.E. 3DLigandSite: Predicting Ligand-Binding Sites Using Similar Structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W469–W473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Roy, A.; Zhang, Y. Protein–Ligand Binding Site Recognition Using Complementary Binding-Specific Substructure Comparison and Sequence Profile Alignment. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2588–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Im, W. Ligand Binding Site Detection by Local Structure Alignment and Its Performance Complementarity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brylinski, M.; Feinstein, W.P. eFindSite: Improved Prediction of Ligand Binding Sites in Protein Models Using Meta-Threading, Machine Learning and Auxiliary Ligands. J. Comput.-Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, F.; Pupko, T.; Paz, I.; Bell, R.E.; Bechor-Shental, D.; Martz, E.; Ben-Tal, N. A Method for Localizing Ligand Binding Pockets in Protein Structures. Proteins 2006, 62, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A. Identifying and Characterizing Binding Sites and Assessing Druggability. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, J.A.; Laskowski, R.A.; Thornton, J.M.; Singh, M.; Funkhouser, T.A. Predicting Protein Ligand Binding Sites by Combining Evolutionary Sequence Conservation and 3D Structure. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. MetaPocket: A Meta Approach to Improve Protein Ligand Binding Site Prediction. OMICS 2009, 13, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, T.; Marsden, B.D.; Blundell, T.L. SitesIdentify: A Protein Functional Site Prediction Tool. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brylinski, M.; Skolnick, J. FINDSITE: A Threading-Based Approach to Ligand Homology Modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Mao, C.; Luan, X.; Shen, D.D.; Shen, Q.; Su, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, W.; Gao, M.; et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. Science 2020, 368, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gervasoni, S.; Vistoli, G.; Talarico, C.; Manelfi, C.; Beccari, A.R.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Waterhouse, A.M.; Schwede, T.; Pedretti, A. A comprehensive mapping of the druggable cavities within the SARS-CoV-2 therapeutically relevant proteins by combining pocket and docking searches as implemented in pockets 2.0. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevan, K.; Palistha, S.; Tayara, H.; Chong, K.T. PUResNetV2.0: a deep learning model leveraging sparse representation for improved ligand binding site prediction. Journal of Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestak, F.; Schneckenreiter, L.; Brandstetter, J.; Hochreiter, S.; Mayr, A.; Klambauer, G. VN-EGNN: E (3)-Equivariant Graph Neural Networks with Virtual Nodes Enhance Protein Binding Site Identification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.07194 2024.

- Smith, Z.; Strobel, M.; Vani, B.P.; Tiwary, P. Graph attention site prediction (grasp): Identifying druggable binding sites using graph neural networks with attention. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2024, 64, 2637–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, J.; Tayara, H.; Chong, K.T. PUResNet: prediction of protein-ligand binding sites using deep residual neural network. Journal of cheminformatics 2021, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepniewska-Dziubinska, M.M.; Zielenkiewicz, P.; Siedlecki, P. Improving detection of protein-ligand binding sites with 3D segmentation. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivák, R.; Hoksza, D. Improving protein-ligand binding site prediction accuracy by classification of inner pocket points using local features. Journal of cheminformatics 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Gupta, A.; Chelur, V.; Jawahar, C.; Priyakumar, U.D. DeepPocket: ligand binding site detection and segmentation using 3D convolutional neural networks. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2021, 62, 5069–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guilloux, V.; Schmidtke, P.; Tuffery, P. Fpocket: an open source platform for ligand pocket detection. BMC bioinformatics 2009, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbery, A.; Buttenschoen, M.; Skyner, R.; von Delft, F.; Deane, C.M. Learnt representations of proteins can be used for accurate prediction of small molecule binding sites on experimentally determined and predicted protein structures. Journal of Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.; Yuan, M.; Ma, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, M. PGBind: pocket-guided explicit attention learning for protein–ligand docking. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2024, 25, bbae455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1505.04597 2015.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 7132–7141.

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, X. Breast cancer histopathological image classification using convolutional neural networks with small SE-ResNet module. PloS One 2019, 14, e0214587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balytskyi, Y.; Kalashnyk, N.; Hubenko, I.; Balytska, A.; McNear, K. Enhancing Open-World Bacterial Raman Spectra Identification by Feature Regularization for Improved Resilience against Unknown Classes. Chemical & Biomedical Imaging 2024, 2, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desaphy, J.; Bret, G.; Rognan, D.; Kellenberger, E. sc-PDB: a 3D-database of ligandable binding sites—10 years on. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, D399–D404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desaphy, J.; Azdimousa, K.; Kellenberger, E.; Rognan, D. Comparison and druggability prediction of protein–ligand binding sites from pharmacophore-annotated cavity shapes. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2012, 52, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellenberger, E.; Schalon, C.; Rognan, D. How to measure the similarity between protein ligand-binding sites? Current Computer-Aided Drug Design 2008, 4, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajusz, D.; Rácz, A.; Héberger, K. Why is Tanimoto index an appropriate choice for fingerprint-based similarity calculations? Journal of Cheminformatics 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.; Others. tfbio: Molecular features featurization library for TensorFlow. https://github.com/gnina/tfbio, 2018. Accessed: YYYY-MM-DD.

- Gros, C.; Lemay, A.; Cohen-Adad, J. SoftSeg: Advantages of soft versus binary training for image segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2021, 71, 102038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Popordanoska, T.; Bertels, J.; Lemmens, R.; Blaschko, M.B. Dice semimetric losses: Optimizing the dice score with soft labels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Cham, 2023; pp. 475–485.

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV). IEEE, 2016, pp. 565–571.

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), October 2017, pp. 2980–2988.

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2010, pp. 807–814.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadi, M.; Anyango, S.; Deshpande, M.; et al. . AlphaFold Protein Structure Database: massively expanding the structural coverage of protein-sequence space with high-accuracy models. Nucleic Acids Research 2022, 50, D439–D444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, G. Rdkit documentation. Release 2013, 1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Yang, Q.; Du, Y.; Feng, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, R. Comparative assessment of scoring functions: the CASF-2016 update. Journal of chemical information and modeling 2018, 59, 895–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Han, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, R. DELPHI Scorer: A Machine-Learning-Based Scoring Function for Protein-Ligand Interactions. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2017, 57, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Deng, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Kang, Y. Boosting protein–ligand binding pose prediction and virtual screening based on residue–atom distance likelihood potential and graph transformer. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 10691–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Kubra, B.; Sharaf, M.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M.; Abdalla, M. Computational study of SARS-CoV-2 rna dependent rna polymerase allosteric site inhibition. Molecules 2021, 27, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parvez, M.S.A.; Karim, M.A.; Hasan, M.; Jaman, J.; Karim, Z.; Tahsin, T.; Hasan, M.N.; Hosen, M.J. Prediction of potential inhibitors for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of SARS-CoV-2 using comprehensive drug repurposing and molecular docking approach. International journal of biological macromolecules 2020, 163, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banner, D.W.; Hadváry, P. Crystallographic analysis at 3.0-A resolution of the binding to human thrombin of four active site-directed inhibitors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1991, 266, 20085–20093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weitz, J.I.; Buller, H.R. Direct thrombin inhibitors in acute coronary syndromes: present and future. Circulation 2002, 105, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, J.T.B.; Zanardelli, S.; Chion, C.K.N.K.; Lane, D.A. The central role of thrombin in hemostasis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007, 5, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, T.E.; Huntington, J.A. Thrombin-cofactor interactions: structural insights into regulatory mechanisms. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2006, 26, 1738–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, P.; Panizzi, P.; Verhamme, I. Exosites in the substrate specificity of blood coagulation reactions. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 2007, 5, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, R.; Balasco, N.; Autiero, I.; Vitagliano, L.; Sica, F. Exosite binding in thrombin: a global structural/dynamic overview of complexes with aptamers and other ligands. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 10803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrera, N.S.; Stafford, A.R.; Leslie, B.A.; Kretz, C.A.; Fredenburgh, J.C.; Weitz, J.I. Long range communication between exosites 1 and 2 modulates thrombin function. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 25620–25629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, S.; Kannan, K. Drug-protein interactions: refined structures of three sulfonamide drug complexes of human carbonic anhydrase I enzyme. Journal of molecular biology 1994, 243, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sippel, K.H.; Robbins, A.H.; Domsic, J.; Genis, C.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; McKenna, R. High-resolution structure of human carbonic anhydrase II complexed with acetazolamide reveals insights into inhibitor drug design. Acta Crystallographica Section F: Structural Biology and Crystallization Communications 2009, 65, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeiffer, N. Innovative glaucoma therapy: Glaucoma therapy with topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Der Ophthalmologe: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft 2001, 98, 953–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supuran, C.T. Carbonic anhydrases: Novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, D.N.; Lindskog, S. The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase: implications of a rate-limiting protolysis of water. Accounts of Chemical Research 1988, 21, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.K.; Christianson, D.W. Unexpected pH-dependent conformation of His-64, the proton shuttle of carbonic anhydrase II. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1991, 113, 9455–9458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomelino, C.L.; Andring, J.T.; McKenna, R. Crystallography and its impact on carbonic anhydrase research. International journal of medicinal chemistry 2018, 2018, 9419521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jude, K.M.; Banerjee, A.L.; Haldar, M.K.; Manokaran, S.; Roy, B.; Mallik, S.; Srivastava, D.; Christianson, D.W. Ultrahigh resolution crystal structures of human carbonic anhydrases I and II complexed with “two-prong” inhibitors reveal the molecular basis of high affinity. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2006, 128, 3011–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; Jude, K.M.; Banerjee, A.L.; Haldar, M.; Manokaran, S.; Kooren, J.; Mallik, S.; Christianson, D.W. Structural analysis of charge discrimination in the binding of inhibitors to human carbonic anhydrases I and II. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2007, 129, 5528–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, M.; Okajima, T.; Yamashita, A.; Oda, T.; Hirata, K.; Nishiwaki, H.; Morimoto, T.; Akamatsu, M.; Ashikawa, Y.; Kuroda, S.; et al. Crystal structures of Lymnaea stagnalis AChBP in complex with neonicotinoid insecticides imidacloprid and clothianidin. Invertebrate Neuroscience 2008, 8, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taly, A.; Corringer, P.J.; Guedin, D.; Lestage, P.; Changeux, J.P. Nicotinic receptors: allosteric transitions and therapeutic targets in the nervous system. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2009, 8, 733–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneric, S.P.; Holladay, M.; Williams, M. Neuronal nicotinic receptors: a perspective on two decades of drug discovery research. Biochemical pharmacology 2007, 74, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, E.D.; Rezvani, A.H. Nicotinic interactions with antipsychotic drugs, models of schizophrenia and impacts on cognitive function. Biochemical Pharmacology 2007, 74, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanelli, M.N.; Gratteri, P.; Guandalini, L.; Martini, E.; Bonaccini, C.; Gualtieri, F. Central nicotinic receptors: structure, function, ligands, and therapeutic potential. ChemMedChem: Chemistry Enabling Drug Discovery 2007, 2, 746–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, J.; Le, T.; Noé, F.; Clevert, D.A.; Schütt, K.T. PILOT: equivariant diffusion for pocket-conditioned de novo ligand generation with multi-objective guidance via importance sampling. Chemical Science 2024, 15, 14954–14967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, A.; Xie, J.; Huang, W.; Zhang, H.; Rao, J.; Zheng, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, G.B.; Lei, J. A 3D pocket-aware and affinity-guided diffusion model for lead optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.21065 2025.

- Alakhdar, A.; Poczos, B.; Washburn, N. Diffusion models in de novo drug design. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2024, 64, 7238–7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, O.; Zhang, J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, X.; Hu, R.; Shen, C.; Cao, H.; Du, H.; Kang, Y.; Deng, Y.; et al. ResGen is a pocket-aware 3D molecular generation model based on parallel multiscale modelling. Nature Machine Intelligence 2023, 5, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xu, T.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Chen, X.; Han, J.; Xie, Z.; Li, H.; Zhong, W.; Wong, K.C.; et al. A dual diffusion model enables 3D molecule generation and lead optimization based on target pockets. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | A demonstration video is available at: https://youtu.be/EkUKmoW11pE?si=3aKBkL3ZRq8ibWqo

|

| 2 | PUResNet V1[69] predicts cavities where the ligand is likely to reside, whereas PUResNet V2 [66] predicts residues likely to interact with the ligand. For simplicity, we refer to PUResNet V1 as “PUResNet” throughout the text, as in this work we focus on cavities for generating an accurate search grid for subsequent docking. |

| 3 |

| Method | Nonzero | Within 15 Å | PLI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalasanty | 263 | 249 | 74.34% |

| PUResNet | 278 | 265 | 79.51% |

| RAPID Run 1 | 307 | 298 | 90.17% |

| RAPID Run 2 | 305 | 289 | 87.90% |

| RAPID Run 3 | 308 | 296 | 88.71% |

| RAPID Run 4 | 308 | 300 | 88.57% |

| RAPID Run 5 | 308 | 292 | 86.32% |

| RAPID ensemble | 308 | 307 | 91.44%/98.09% |

| Method | Nonzero | Within 15 Å | PLI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalasanty | 73 | 70 | 78.72% |

| PUResNet | 76 | 72 | 82.36% |

| RAPID Run 1 | 85 | 83 | 94.83% |

| RAPID Run 2 | 85 | 79 | 89.00% |

| RAPID Run 3 | 85 | 78 | 91.09% |

| RAPID Run 4 | 85 | 83 | 92.61% |

| RAPID Run 5 | 85 | 81 | 92.47% |

| RAPID ensemble | 85 | 84 | 97.15%/98.82% |

| Method | Nonzero | Within 15 Å | PLI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalasanty | 273 | 248 | 76.41% |

| PUResNet | 280 | 259 | 78.37% |

| RAPID Run 1 | 296 | 285 | 85.68% |

| RAPID Run 2 | 298 | 279 | 86.48% |

| RAPID Run 3 | 293 | 264 | 76.78% |

| RAPID Run 4 | 298 | 288 | 91.39% |

| RAPID Run 5 | 298 | 275 | 80.59% |

| RAPID ensemble | 298 | 297 | 86.75%/95.49% |

| Method | Nonzero | Within 15 Å | PLI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalasanty | 54 | 53 | 77.80% |

| PUResNet | 42 | 39 | 46.90% |

| RAPID Run 1 | 61 | 60 | 86.52% |

| RAPID Run 2 | 62 | 62 | 97.57% |

| RAPID Run 3 | 61 | 60 | 86.68% |

| RAPID Run 4 | 60 | 58 | 84.47% |

| RAPID Run 5 | 62 | 43 | 46.97% |

| RAPID ensemble | 62 | 62 | 95.79%/99.82% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).