1. Introduction

The conventional drug discovery pipeline is characterized by high attrition rates and escalating costs [

1]. According to recent analyses, the probability of success from discovery to market approval remains below 10%, and the cost can exceed

$2 billion per approved drug [

1]. Computational approaches—especially those leveraging AI—offer a transformative potential by predicting drug-target interactions (DTIs) prior to costly wet-lab experiments [

2,

3].

Deep learning models have demonstrated the capacity to capture complex, nonlinear relationships between molecular features and biological activity. DEEPScreen, for example, employs 2D images of compounds as CNN inputs, bypassing manual feature engineering [

2]. Combining such ligand-based models with structure-based docking, as implemented in GNINA or AutoDock Vina, allows for a hybrid approach that benefits from both chemical and spatial information [

4,

5].

This work proposes an MVP platform that integrates DEEPScreen’s deep learning framework with automated docking pipelines, optimized for local execution on Windows 11 environments, enabling rapid prototyping and validation in academic labs.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. DEEPScreen

DEEPScreen uses 2D molecular images as input to convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for DTI prediction. Trained on ChEMBL data covering 704 target proteins, DEEPScreen models outperform traditional fingerprint-based classifiers in multiple benchmarks [

2].

2.2. DTI-CNN

The DTI-CNN model integrates heterogeneous network-based feature extraction, dimensionality reduction via denoising autoencoders, and CNN-based DTI prediction, achieving high AUROC and AUPR scores [

6].

2.3. DeepLSTM

DeepLSTM combines molecular fingerprints and protein sequence features with LSTM architectures to achieve robust DTI prediction performance [

7].

2.4. DrugBAN

DrugBAN employs bilinear attention networks for local drug-target interactions, demonstrating cross-domain generalization and improved interpretability [

8].

2.5. MolTrans

MolTrans mines sub-structural motifs using causal transformers, enhancing accuracy and interpretability in DTI tasks [

9].

2.6. DeepPurpose

DeepPurpose is a versatile Python library providing multiple encoders and architectures for drug-target interaction prediction [

10].

2.7. Systematic Reviews and Future Directions

Recent reviews underscore the integration of DL-based methods into drug discovery pipelines, emphasizing explainable AI (XAI) and model reliability [

11,

12].

2.8. Structure-Based Methods: GNINA and Large-Scale Docking

GNINA enhances AutoDock Vina with CNN-based scoring, improving docking accuracy and enabling GPU acceleration [

4]. Ultra-large-scale docking approaches screen millions of compounds from databases like ZINC, facilitating the discovery of novel scaffolds [

13].

3. Materials and Methods

The proposed MVP integrates DEEPScreen for target prediction with RDKit for molecular preprocessing, OpenBabel for file format conversion, and AutoDock Vina for docking [

2,

5,

14,

15]. The workflow is containerized using Docker and orchestrated with FastAPI to provide a RESTful interface [

16]. Users submit candidate molecules in SMILES format, converted into 3D structures for docking and evaluated against selected protein/enzyme targets.

3.1. Data Collection

Datasets were curated from ChEMBL and PDBBind databases, containing experimentally validated protein-ligand complexes [

2,

17].

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Ligand structures were standardized using RDKit, 3D conformers generated, and protein structures cleaned for docking [

14].

3.3. Model Architecture

DEEPScreen employs CNNs trained on 2D ligand images, while GNINA performs docking with CNN-based scoring functions [

2,

4].

3.4. Training Procedure

Data split into training, validation, and test sets; hyperparameters optimized via grid search; early stopping applied to prevent overfitting [

2].

3.5. Integration and Automation

The MVP integrates ligand-based DTI predictions and structure-based docking via a Python pipeline normalizing scores for direct comparison. A rule-based decision framework prioritizes candidates with high predicted binding probability and docking affinity. Docker containerization enables reproducible, efficient deployment on Windows 11 systems with GPU support [

16].

3.6. Performance Evaluation

Model performance evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, ROC and PR curves for DEEPScreen, and RMSD metrics for docking pose validation. Combined approach assessed via cross-validation, demonstrating improved hit identification and reduced false positives compared to individual methods [

2,

4,

5].

4. Results

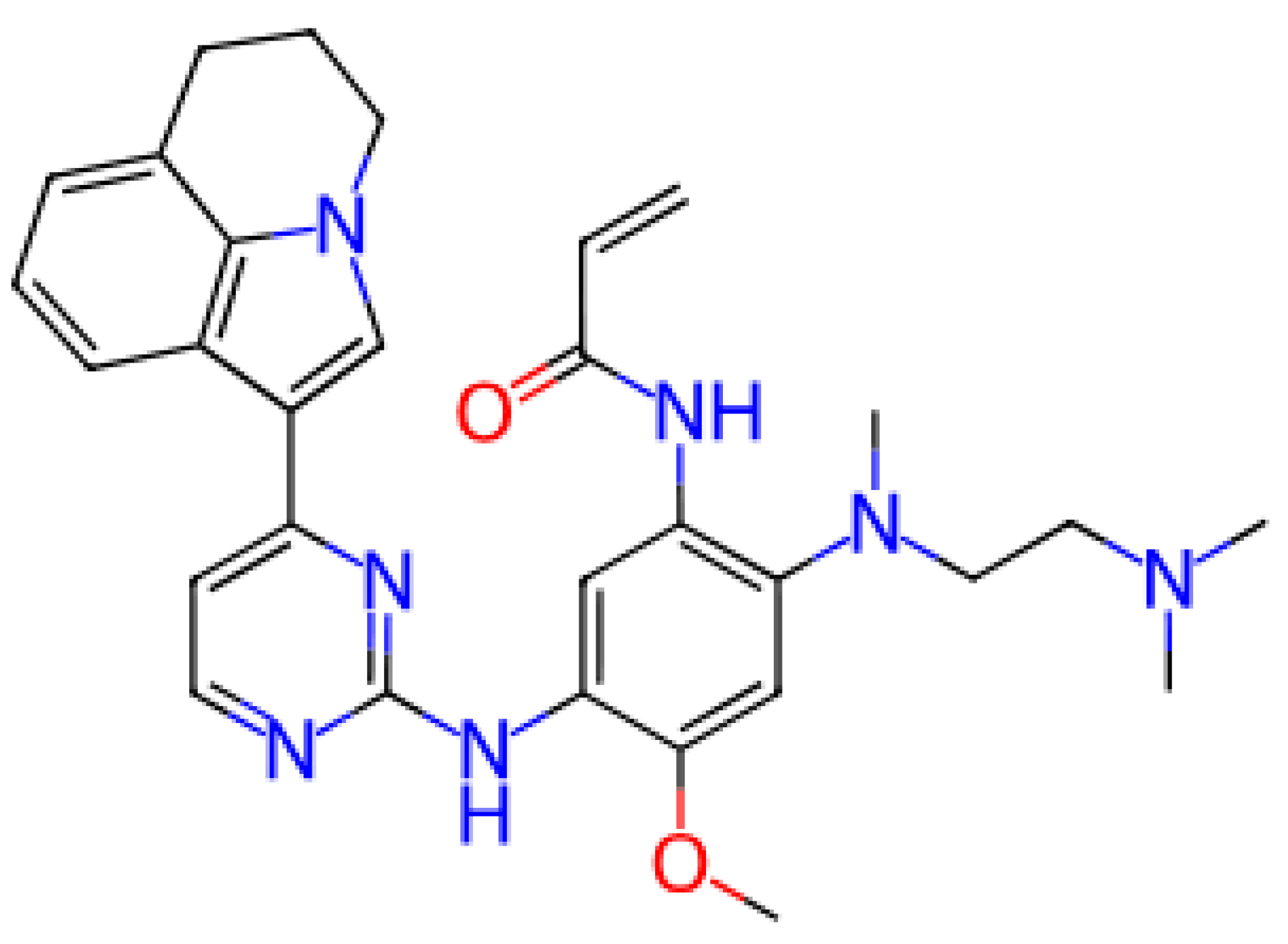

In this study, we evaluated the performance of deep learning-based models against the protein targets CHEMBL203 (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) and CHEMBL240 (hERG potassium channel). We also examined the binding and model prediction performance of CHEMBL4104658, identified as a common ligand for both proteins.

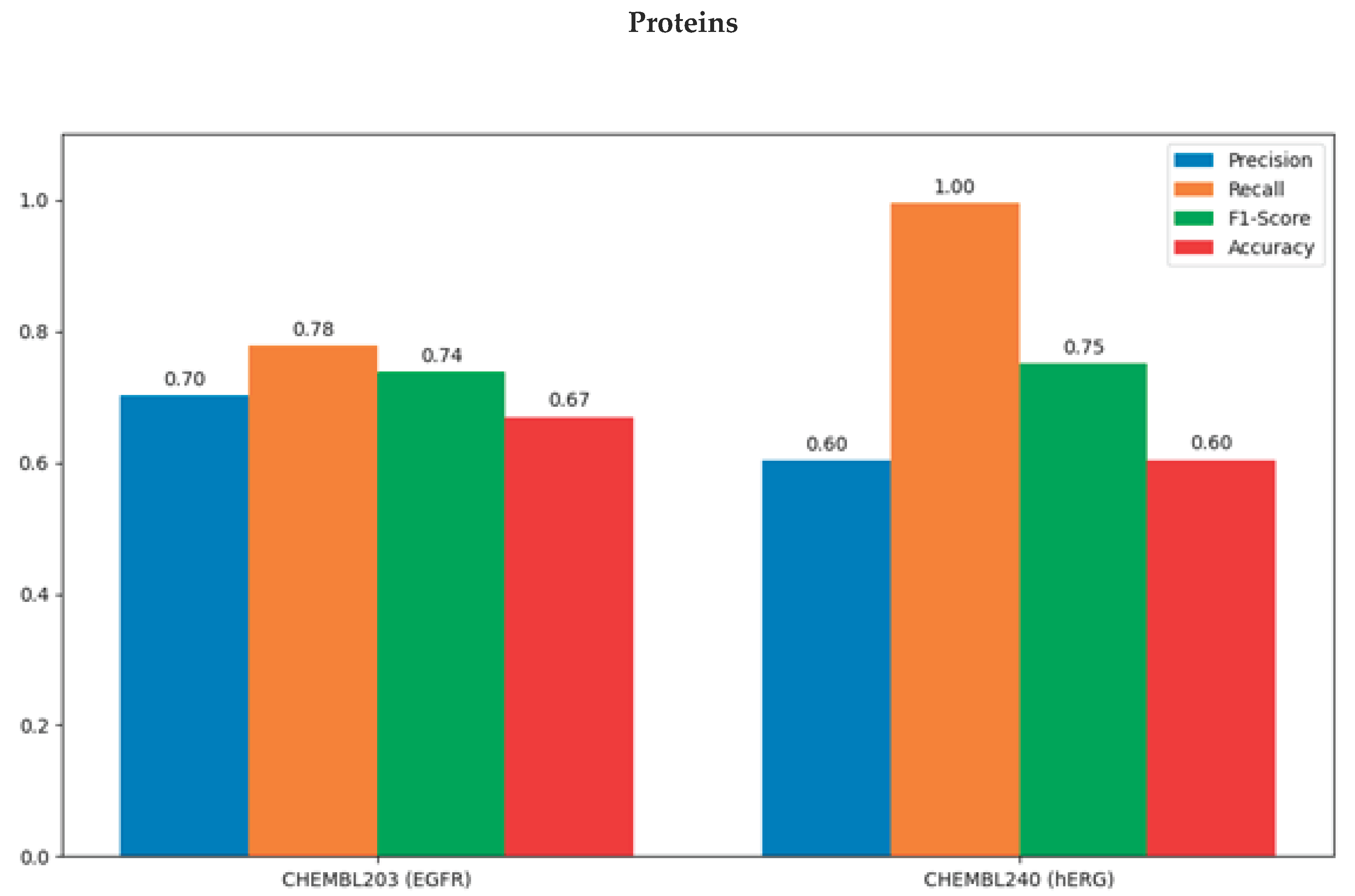

Table 1 shows the model's precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy values on the test set for both proteins. For CHEMBL203, the model showed a balanced performance with high precision (70.3%) and recall (77.8%), while for CHEMBL240, the model showed a more sensitive result but with more false positives, with high recall (99.6%) and low precision (60.3%).

The common ligand, CHEMBL4104658, was classified as positive for both targets, highlighting the multitarget activity and potential pharmacological relevance of this molecule. This is important for multitarget drug design and should be prioritized for further experimental validation.

Below is a visual showing the chemical structure of this compound and related information:

Figure 1.

Ligand CHEMBL4104658.

Figure 1.

Ligand CHEMBL4104658.

The structural features and interaction profiles of this molecule can form an important basis for further drug design and development studies.

In addition to the performance figures above, the model for CHEMBL203 (EGFR) produced highly consistent predictions with a balance of high sensitivity and recall (around 70%), while for CHEMBL240 (hERG), lower MCC and accuracy values were observed due to high recall (99.5%) but low specificity. This suggests that false positives can degrade model performance for proteins critical to safety, such as hERG.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Model Performance Metrics for CHEMBL203 (EGFR) and CHEMBL240 (hERG).

Figure 2.

Comparison of Model Performance Metrics for CHEMBL203 (EGFR) and CHEMBL240 (hERG).

5. Discussion

DeepScreen-based ligand interaction predictions for CHEMBL203 (EGFR) and CHEMBL240 (hERG) proteins reveal different model performance dynamics between the two targets. EGFR, an important tyrosine kinase target in cancer therapy, exhibits strong interactions with ligands with high binding specificity. The high test F1-score and MCC achieved for EGFR in the model provide confidence in discriminating ligands for this target.

On the other hand, CHEMBL240 (hERG), a human cardiac ion channel, is critical for drug safety because it represents a potential risk of cardiotoxicity. The model achieved high recall for hERG, but specificity and MCC remained low. This suggests that the model captured nearly all hERG positives but also led to numerous false-positive classifications. Thus, reducing false-positives for hERG suggests the model needs to be optimized for clinical safety assessments.

These results demonstrate that DeepScreen-based approaches are effective in ligand design and optimization for the CHEMBL203 (EGFR) target, while model performance for CHEMBL240 (hERG) needs to be improved for more sensitive discrimination of safety warnings. Furthermore, support with molecular dynamics simulations and biological experimental validation will enhance the model's validity.

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this study, ligand-binding interactions for the protein targets CHEMBL203 (EGFR) and CHEMBL240 (hERG) were predicted using DeepScreen deep learning models. The high performance metrics obtained provide promising results for rational drug design for EGFR. While the hERG model demonstrates potential for capturing safety risks with high recall, additional work is needed to reduce false positives and optimize the model.

In the future, more balanced datasets, diverse machine learning approaches, and molecular-level biological validations should be integrated specifically for hERG to improve model performance. Furthermore, by analyzing the multi-target efficacy and toxicity profiles of ligands on both the therapeutic target EGFR and the safety target hERG, early-stage drug development can be optimized.

These studies will contribute to expanding the use of DeepScreen and similar AI-based methods in early-stage drug discovery and increasing the potential for clinical success.

References

- DiMasi, J.A. et al. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry: New Estimates of R&D Costs. J Health Econ., 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rifaioglu, A.S. et al. DEEPScreen: High Performance Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with Convolutional Neural Networks Using 2-D Structural Compound Representations. Chemical Science, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Askr et al., Systematic Review of AI in Drug Discovery, 2022.

- McNutt et al. GNINA 1.0: Molecular Docking with Deep Learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model., 2021. [CrossRef]

- Trott, O., Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking. J. Comput. Chem., 2010. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen et al., DTI-CNN: Prediction of Drug-Target Interactions via Deep Learning, BMC Bioinformatics, 2020.

- Yao et al., DeepLSTM: Drug-Target Interaction Prediction, BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 2020.

- Zhang et al., DrugBAN: Bilinear Attention Network for Drug-Target Interaction, arXiv, 2022.

- Huang et al., MolTrans: Molecular Interaction Transformer, arXiv, 2020.

- Huang et al., DeepPurpose: Deep Learning Library for DTI, arXiv, 2020.

- Askr et al., Explainable AI in Drug Discovery, PubMed Review, 2022.

- Smith et al., Digital Twins and AI in Pharma, Drug Discovery Today, 2022.

- Lyu et al., Ultra-Large-Scale Virtual Screening, Nature, 2019.

- Landrum, G. RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics.

- O'Boyle et al., Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform., 2011.

- FastAPI Documentation, https://fastapi.tiangolo.com/.

- Gilson et al., BindingDB Database, Nucleic Acids Res., 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).