Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

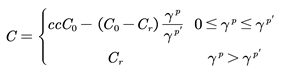

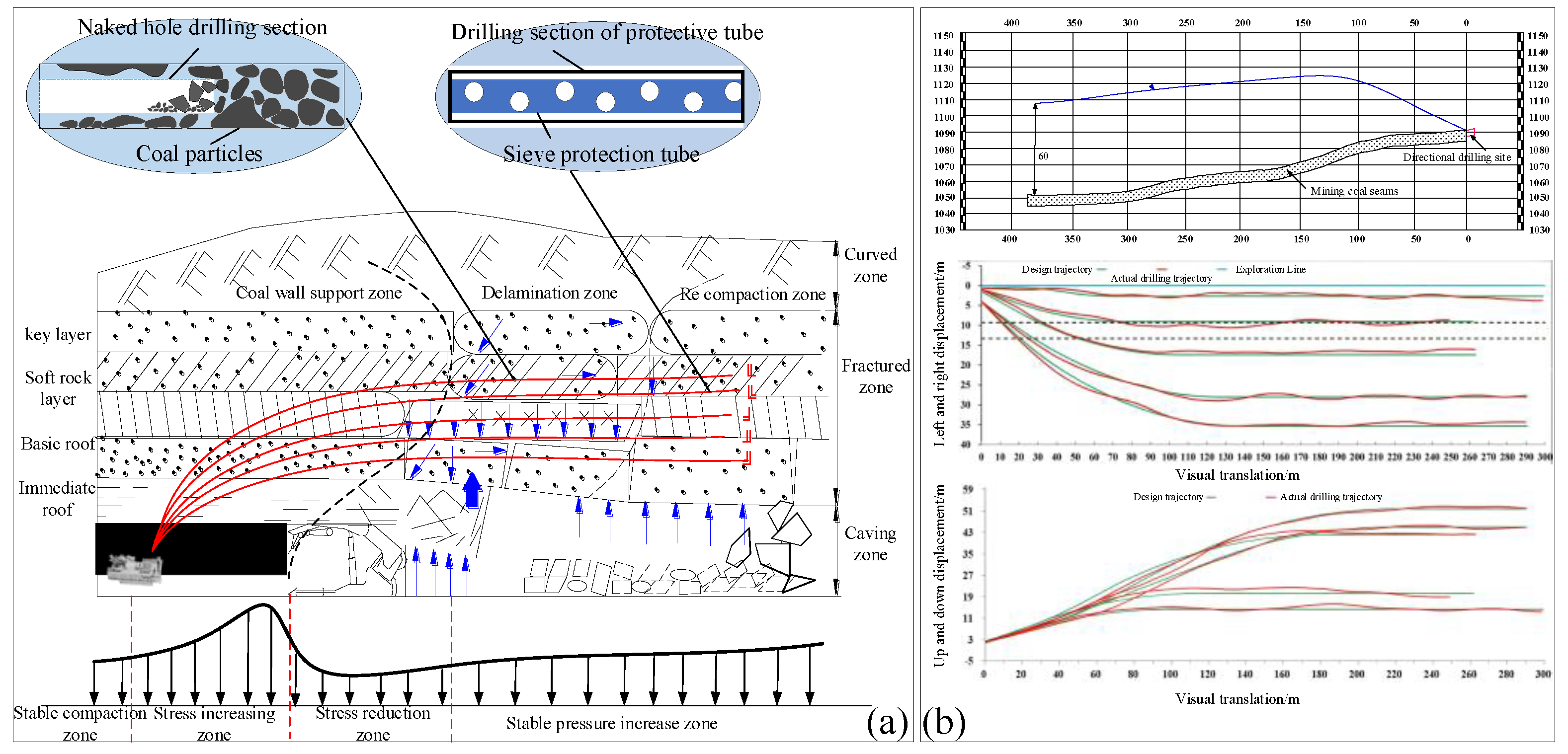

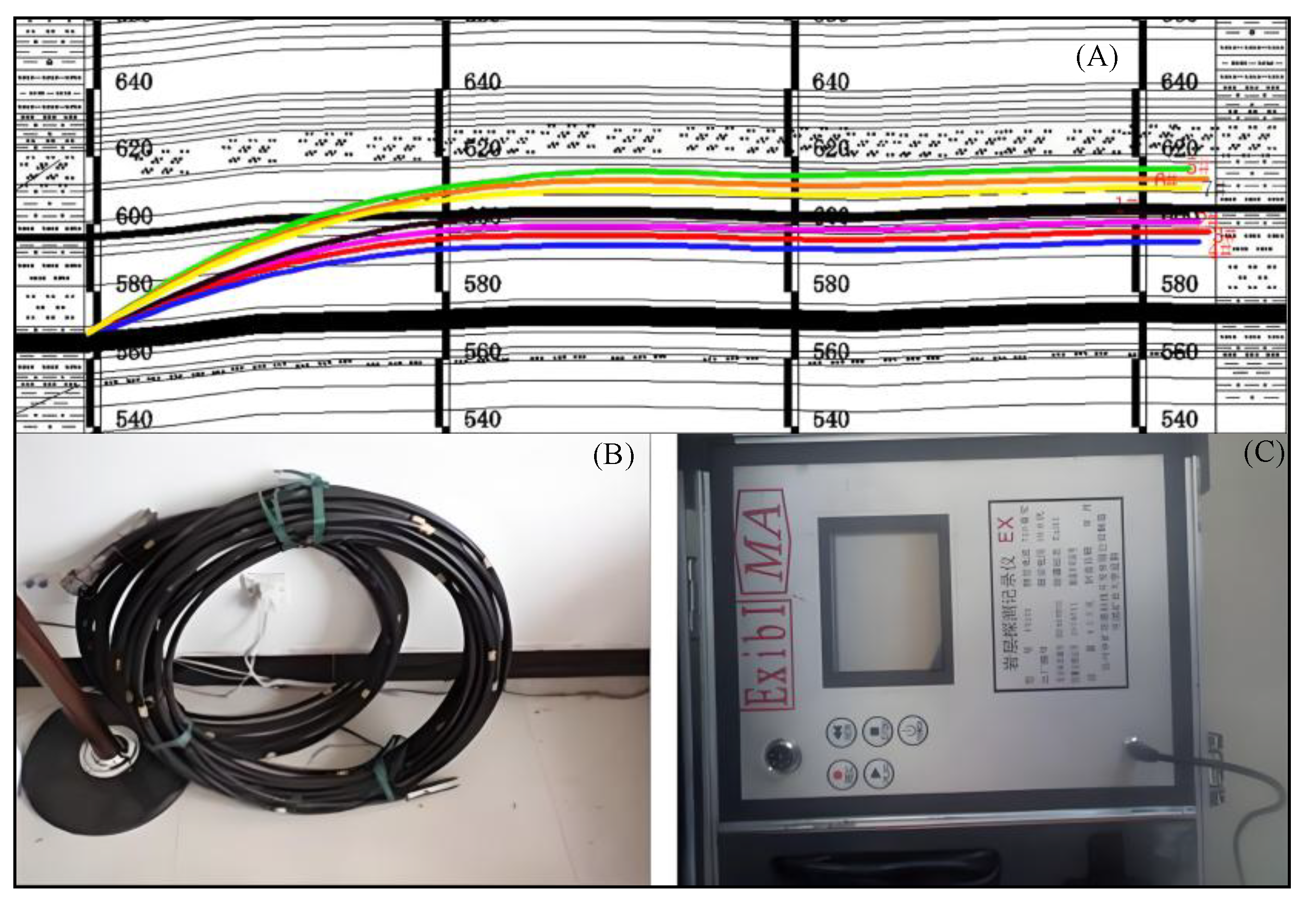

2. Construction and Stress Analysis of High-Level Roof Boreholes in Soft and Fragmented Coal Seams

2.1. Construction Process

2.2. Necessity of Borehole Protection in Directional Drilling within Soft and Fragmented Rock Strata

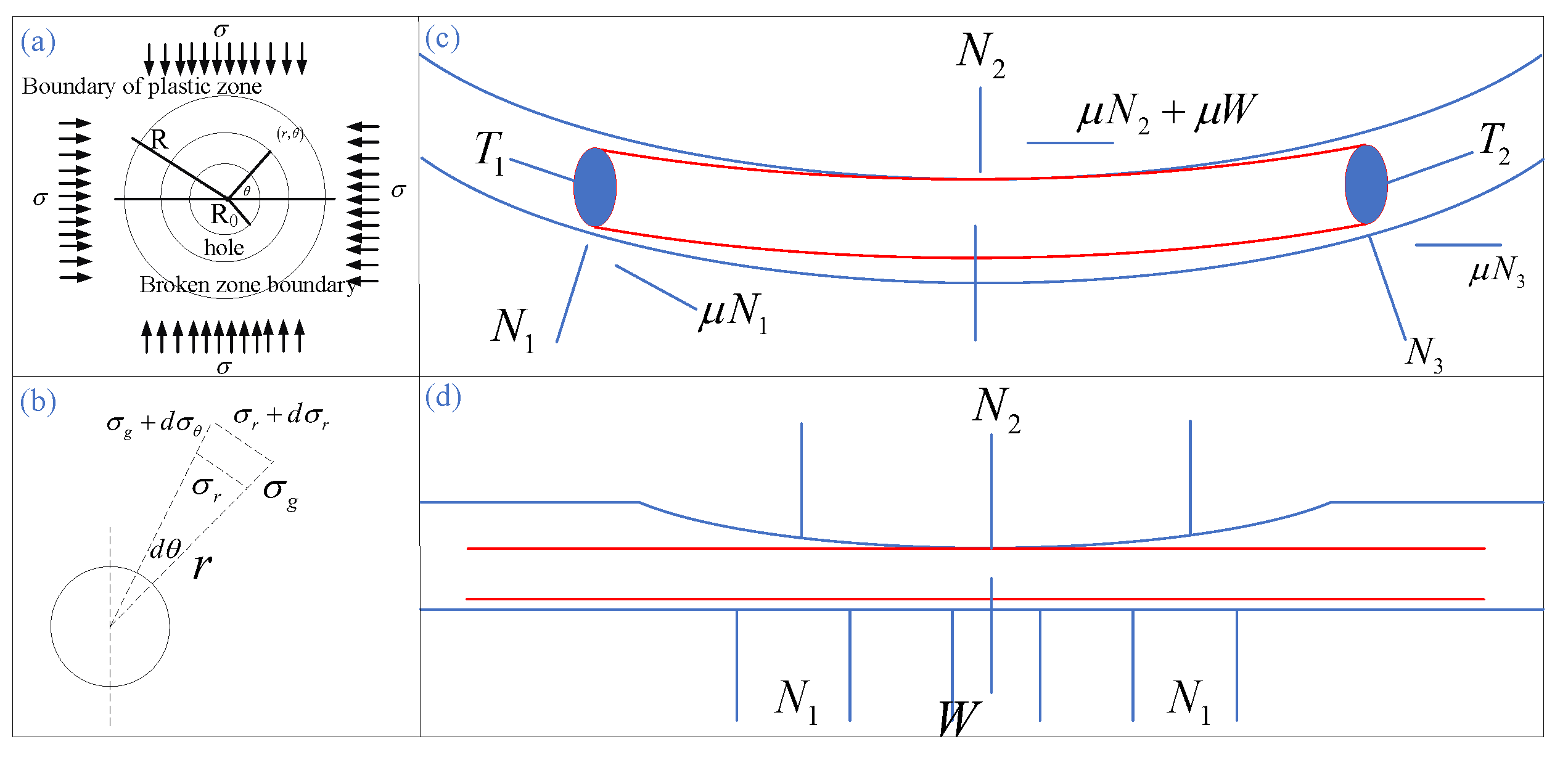

2.3. Stress Analysis of Borehole Protection in Directional Drilling within Soft and Fragmented Rock Strata

3. Directional High-Level Borehole Protection Technology

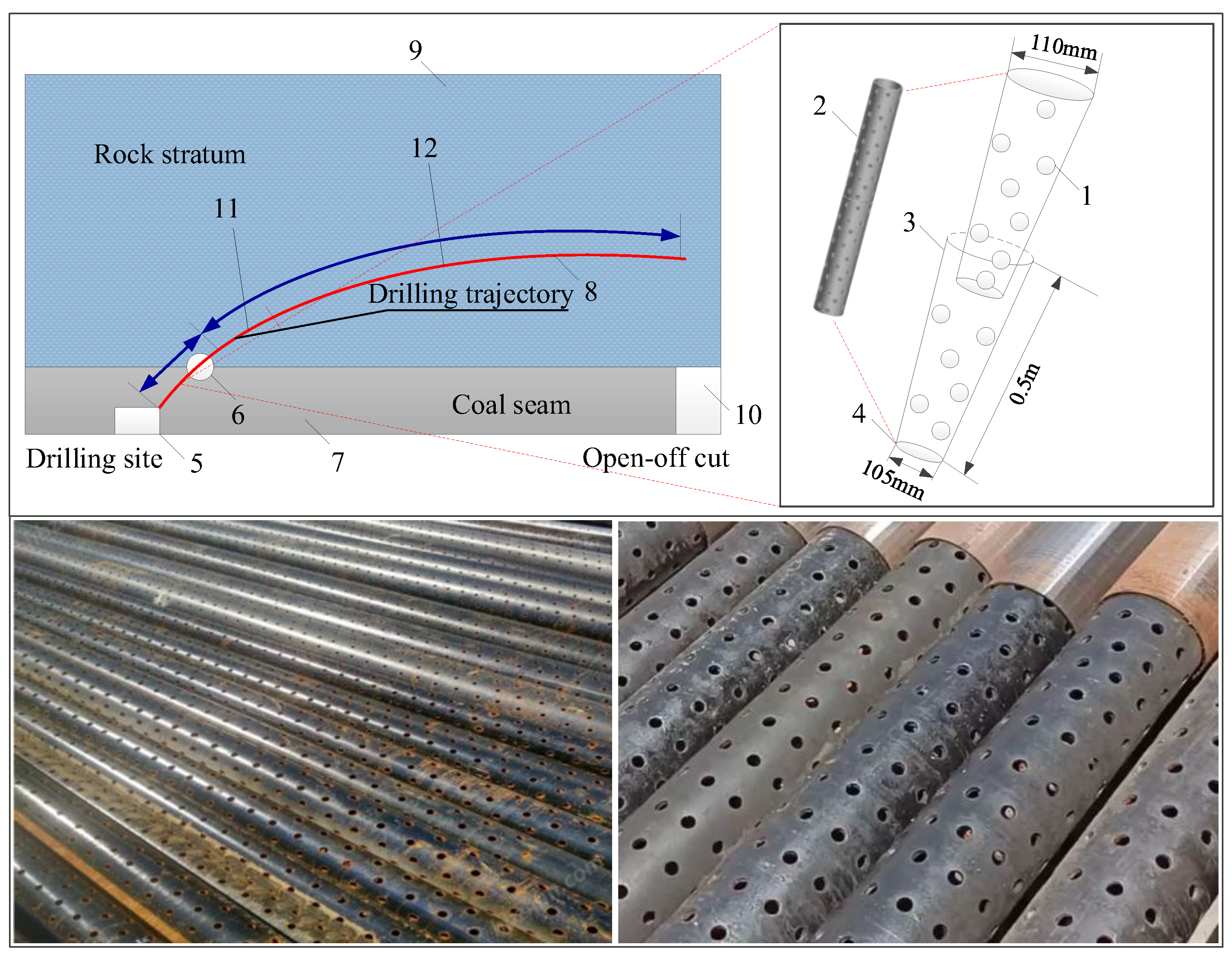

3.1. Composition of the Protective Screen Pipe

3.2. Development and Installation of the Protective Screen Pipe

3.3. Pipe Analysis of Technological Advantages

4. Determination of Key Parameters for Directional High-Level Roof Boreholes

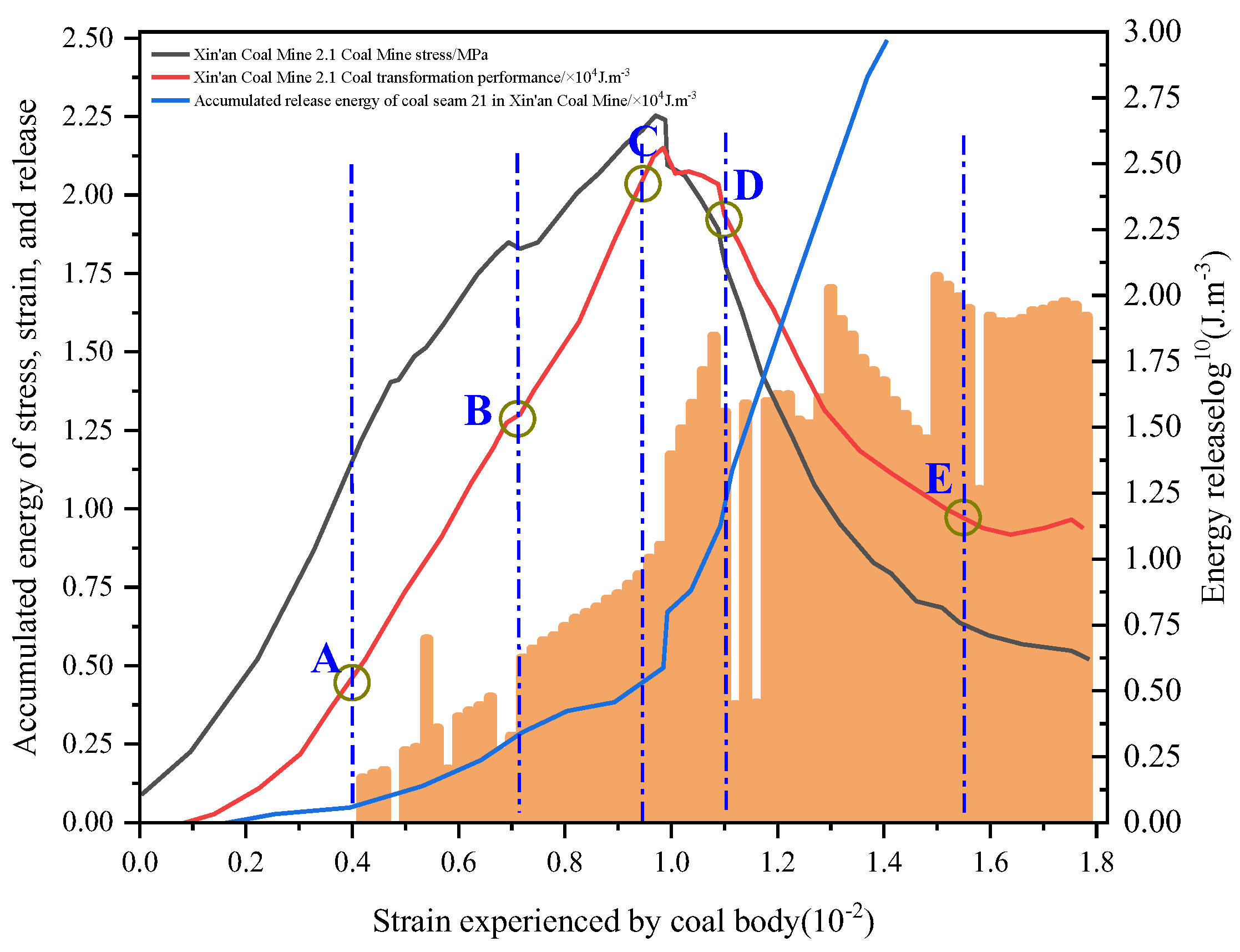

4.1. Fluid-Solid Coupling Model of Coal-rock Media under Pressure-Relief Conditions

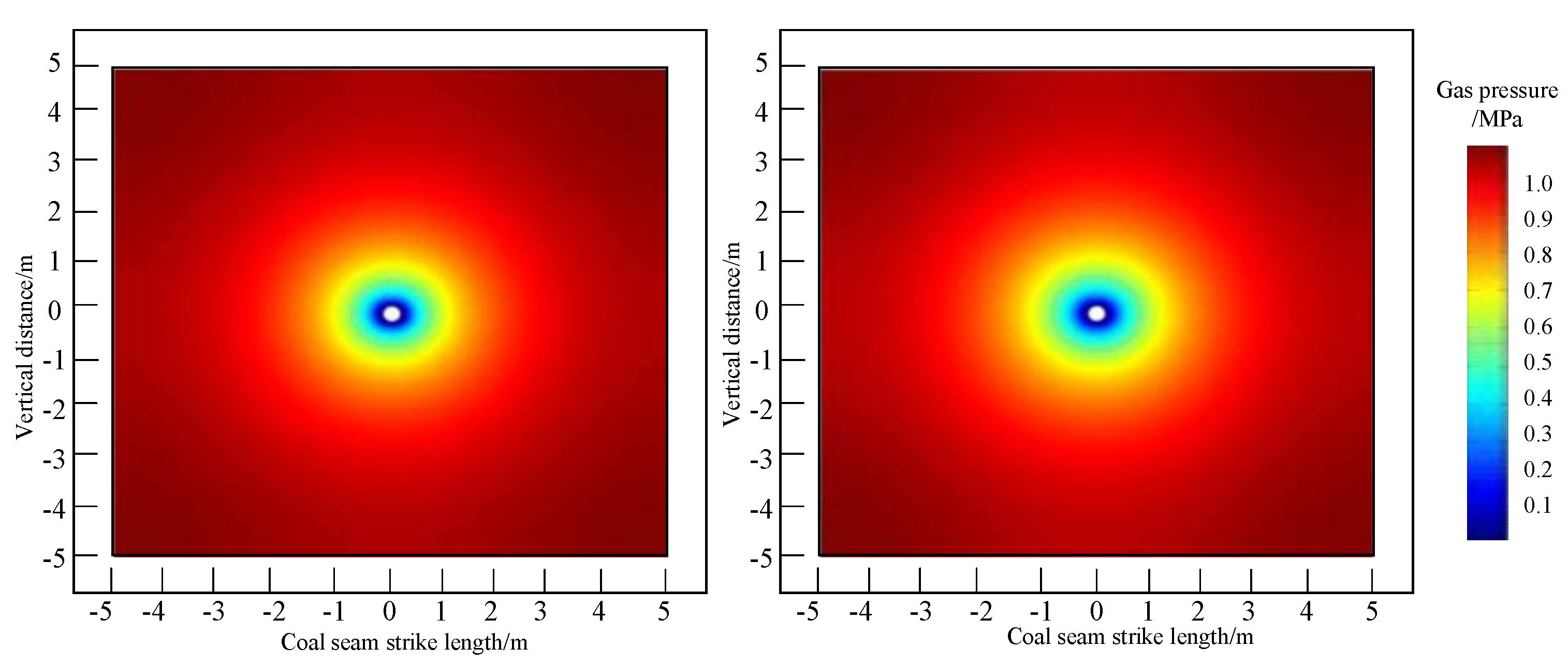

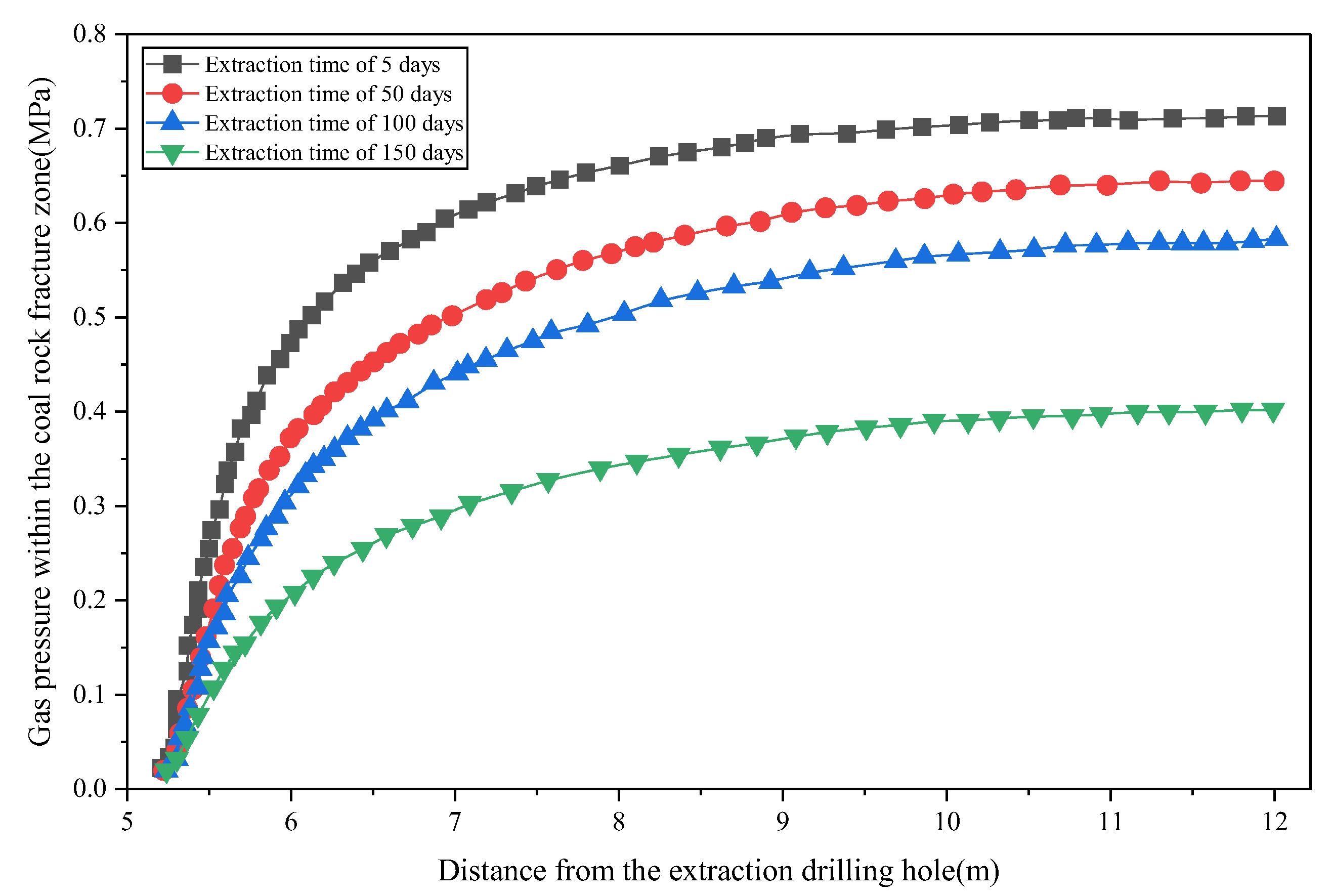

4.2. Influence Radius of Gas Drainage by High-Level Roof Boreholes in the Fracture Zone

4.3. Determination of the Optimal Number of Boreholes

5. Engineering Application

5.1. Borehole Formation Conditions

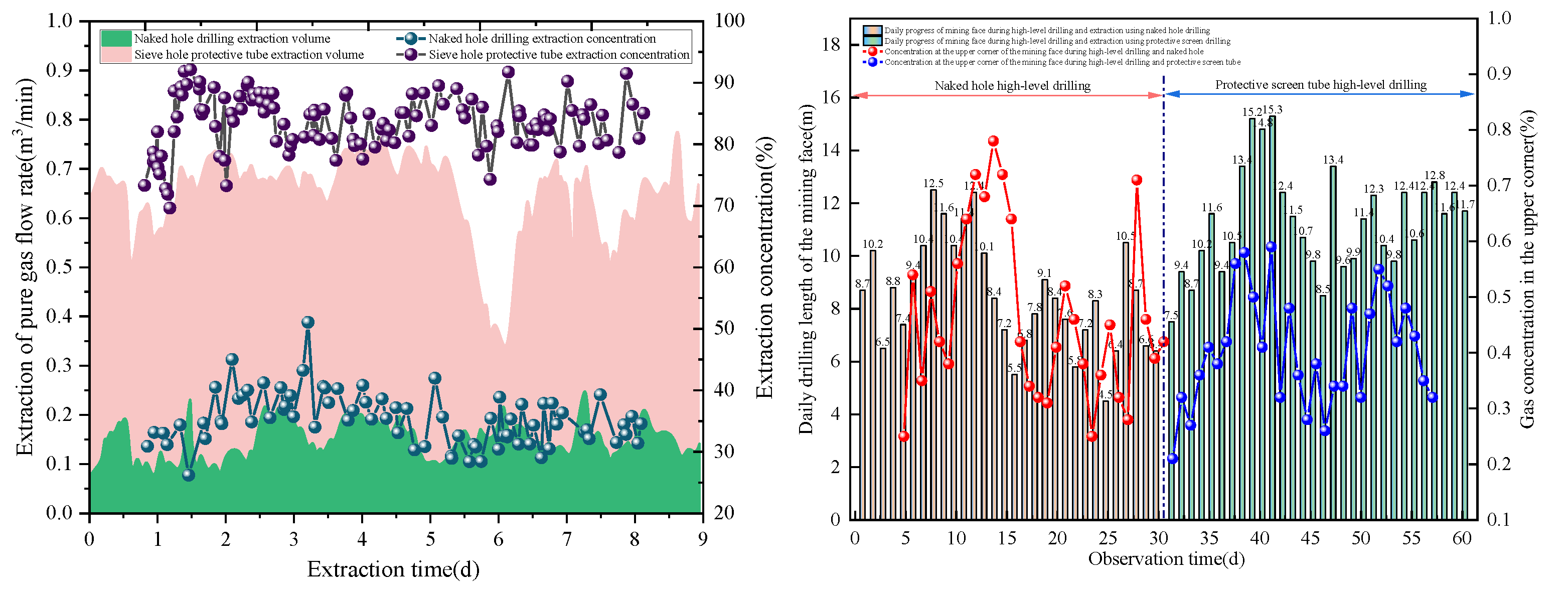

5.2. Gas Extraction Performance

6. Discussion

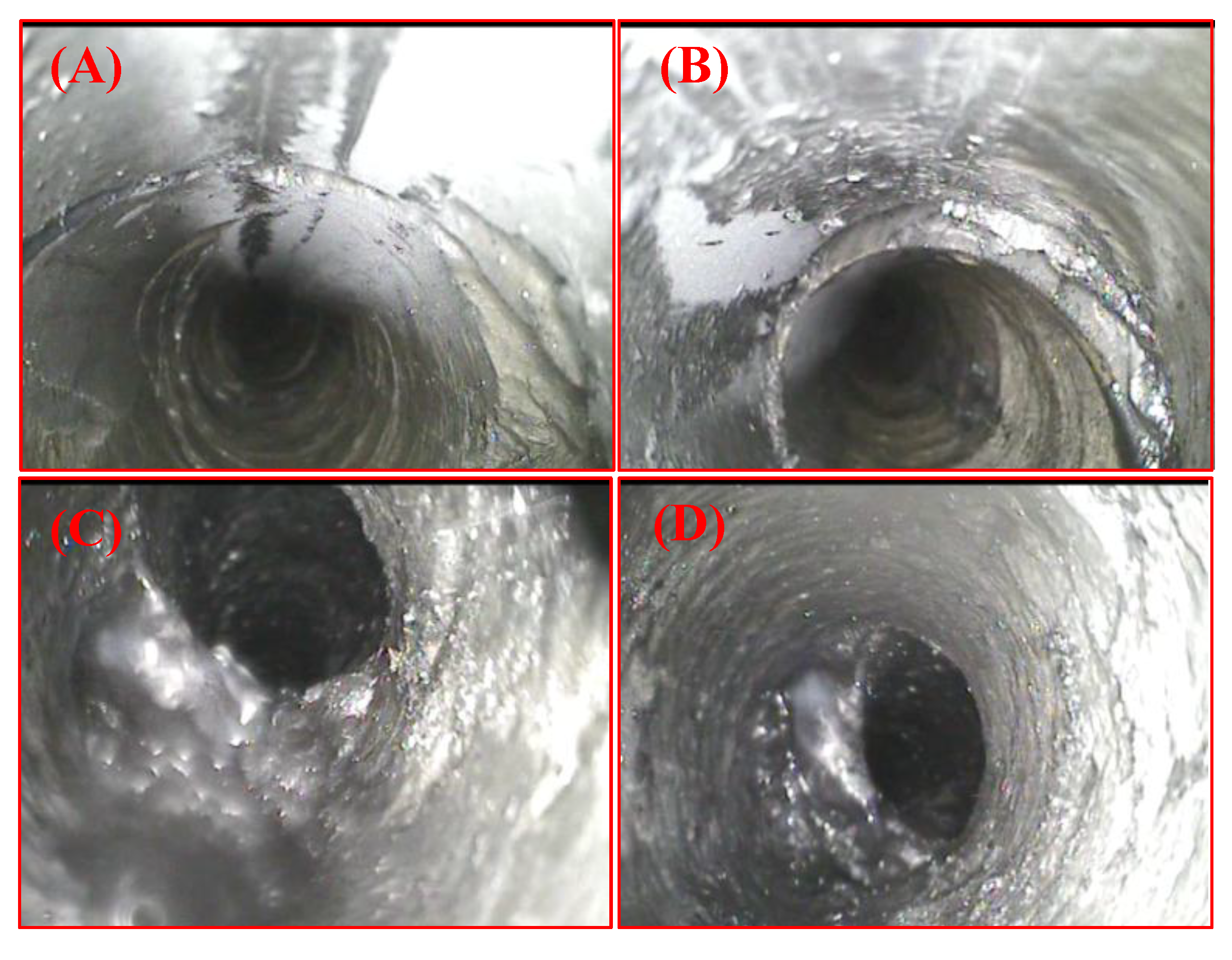

6.1. Stability of the Coal-Rock Interface and Borehole Visualization Results

6.2. Comparative Analysis of Gas Extraction Performance of the Novel Protective Screen Pipe

6.3. Validation of the Fluid-Solid Coupling Model and Optimization of Borehole Parameters

7. Conclusions

- The structural design and mechanical adaptability of the novel protective screen pipe were validated. Based on the mechanical characteristics of soft and fragmented coal-rock masses, a socket-type stainless-steel protective screen pipe with a “larger upper and smaller lower” structure was developed, paired with a PE protective collar pipe of 50 mm diameter to achieve segmented protection along the entire borehole. Mechanical analysis demonstrated that the protective screen pipe effectively resists both radial compressive and axial forces, suppresses crack propagation and systemic collapse at the coal-rock interface, and significantly reduces gas flow resistance. These results confirm that the design is structurally and mechanically compatible with the borehole protection requirements in soft and fragmented strata.

- The stability bottleneck of the coal-rock interface and the effectiveness of the protective technology were quantitatively verified. Visualization of boreholes at the 14230 working face in Xin’an Coal Mine using a YZT-Ⅱ rock formation borehole detector revealed that the coal-rock interface, due to lithological differences, is a high-risk zone for stress concentration, borehole collapse, and wall dislocation. The collapse rate of unprotected boreholes in this zone reached 100%, whereas the wall integrity of boreholes equipped with the new protective screen pipe was maintained at 100%. This ensures unobstructed gas flow throughout the entire extraction period and completely eliminates extraction failure caused by rock accumulation at the borehole end in unprotected boreholes.

- Field applications verified the high efficiency of the protective technology and the rationality of optimized parameters. Comparative field tests conducted at the 14230 working face of Xin’an Coal Mine showed that the gas extraction concentration of protected boreholes remained stable above 80%, with an average pure gas flow rate of ≥0.2 m3/min per borehole. The total gas extraction volume was 8–10 times greater than that of unprotected boreholes. Based on both the fluid-solid coupling model under pressure-relief conditions and field data fitting, the optimal spacing for high-level roof boreholes in this geological setting was determined to be 3.0–3.5 m, with 3–4 boreholes providing the best balance between extraction efficiency and borehole interference avoidance.

- The application of the new protective screen pipe in the soft and fragmented strata of Xin’an Coal Mine confirmed its effectiveness, although some limitations remain. Manual assistance is still required during pipe insertion, and its applicability to floor or vertical boreholes has yet to be verified. Nevertheless, the combined “socket-type protection + drill rig jacking” technique and the optimized fluid-solid coupling parameter model provide a new paradigm for gas control in coal mines with soft and fragmented strata. This approach holds strong potential for direct application in mines characterized by well-developed coal-rock interfaces and significant mining-induced stress, such as Xin’an Coal Mine.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.D.; Zhou, Z.; Ge, Z.L.; Chen, C.J.; Hou, Y.D.; Ye, M.L. Current status and effective suggestions for efficient exploitation of coalbed methane in China: A review. Energy Fuel 2021, 35, 9102–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L. Study on gas extraction technology for goaf using L-shaped borehole on the ground. Appl Sci-Basel 2024, 14, 2076–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.P.; Panigrahi, D.C.; Kumar, P. Computational investigation on effects of geo-mining parameters on layering and dispersion of methane in underground coal mines—A case study of Moonidih Colliery. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 53, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.G.; Chen, K.L.; Liu, H.H. Research on technology of gas drainage in highly gassy and thin coal seams with long wall coal face on the strike. Adv Mater Res. 2013, 807-809, 2450–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Fan, C.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, R. Determination of long horizontal borehole height in roofs and its application to gas drainage. Energies 2018, 11, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, J.; Peng, D. Gas extraction technology and application of near horizontal high directional drilling. Energy Rep 2022, 8, 1326–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Li, S.; Tang, D.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, G. In situ stress distributionand its control on the coalbed methane reservoir permeability in Liulin area, eastern ordos basin, China. Geofluids 2021, 1, 9940375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. Research on gas drainage technology and equipment of high-level directional drilling in coal mine. E3S Web Conf 2024, 528, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; He, C.; Rao, G.; Yan, B.; Lin, A.; Hu, J.; Yu, Y.; Yao, Q. Geomorphological and structural characterization of the southern Weihe Graben, Central China: Implications for fault segmentation. Tectonophysics 2018, 722, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klishin, VI.; Pavlova, LD.; Fryanov, VN.; et al. Influence of spatial orientation of initiator-notch on roof rock deformation near production face in directional hydraulic fracturing. J Min Sci. 2025, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Yuan, L.; Chu, P.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Wang, L. Efficient-safe gas extraction in the superimposed stress strong-outburst risk area: Application of a new hydraulic cavity technology. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 240, 213076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Yang, H.; Hu, P.; Sheng, K.; Ji, H.; Xu, W.; Li, W.; Xi, J.; Lu, Z. Study on roof high-level borehole drainage technology based on temporal and spatial evolution law of gas migration. Min Metall Explor. 2024, 41, 3419–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, R.; Wang, X. Pressure relief gas drainage in a fully mechanised mining face based on the comprehensive determination of ‘three zones’ development height. Arch Min Sci. 2024, 69(2), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, W. Numerical Simulation Research on the Pressure Relief and Permeability Enhancement Mechanism of Large-Diameter Borehole in Coal Seam. Geofluids 2022, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qin, Y.; Tang, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int J Coal Geol. 2023, 279, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tao, S.; Tang, D. In situ coal permeability and favorable development methods for coalbed methane (CBM) extraction in China: from real data. Int J Coal Geol. 2024, 284, 104472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Research on gas extraction effect of high gas mines based on stereoscopic cross directional drilling technology. Acad J Sci Technol 2024, 12, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.E.; Zhen, L. Optimization and application of uncoupled charge coefficient for directional blasting of sandstone roadway roof. Blast 2024, 41, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Han, K.; Xiao, P.; Wang, J.; Zhao, B.; Shuang, H. Evolution law of overburden pressure relief gas enrichment area in fully mechanized caving face of three-soft coal seams and field application. Geoenergy Sci Eng 2024, 238, 212857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.B.; Cao, A.Y.; Xiang, Z.Z.; Wei, C.C.; Si, G.Y. Numerical investigation of two typical outbursts in development headings: A case study in a Chinese coalfield. J Rock Mech Geotech. 2025, 17, 2682–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, X.; Hu, G.; Li, S.; Zhu, K. Fracture evolution mechanisms and roof failure assessment in shallow-buried soft coal seams under fully mechanized caving mining. Appl Sci-Basel 2025, 15, 2076–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.J.; Chen, D.X.; Liu, W.D.; Peng, C.Y.; Cai, F.H.; Hui, D.Z.; Yan, H.H. Study on surrounding rock control technology of gob-gob roadway driven by fully mechanized caving with large mining height and small coal pillar in extra thick coal seam. Energy Sci Eng. 2025, 13, 3422–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.S.; Chang, X.; Yang, C.H.; Guo, Y.T.; Shi, X.L. Integrated supercritical CO2 injection for shale reservoir enhancement: Mechanisms, experimental insights, and implications for energy and carbon storage. Energy 2025, 324, 135908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, K.; Jia, C.; Song, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhuo, Q.; Lu, X. Constraining tectonic compression processes by reservoir pressure evolution: Overpressure generation andevolution in the Kelasu Thrust Belt of Kuqa Foreland Basin, NW China. Mar Petrol Geol. 2016, 72, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Deng, F.H. Tectonic characteristics and evolution of the middle segment of the Jinxi flexure fold belt in the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin. Geol Sci. 2024, 59, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klishin, V.I.; Pavlova, L.D.; Fryanov, V.N.; Tsvetkov, A.B. Influence of spatial orientation of initiator-notch on roof rock deformation near production face in directional hydraulic fracturing. J Min Sci. 2025, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| screen pipe production parameters/mm | Strength of screen pipe/MPa | |||

| Upper port diameter | Lower port diameter | Wall thickness of protective hole tube | Screen pipe size | Resistance to internal pressure |

| 110 | 105 | 7 | 6-8 | 38 |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

| Gas adsorption pressure pL(MPa) | 1.98 | Langmuir constant mL/g | 0.06 |

| Klinkenberg coefficient | 1.44 | Gas adsorption strain εL | 0.10 |

| Rock density ρ(kg/m³) | 2550 | Fracture compressibility Cf | 0.0024 |

| Rock Poisson’s ratio v | 0.3 | Initial gas pressure p0 | 1.03MPa |

| Rock matrix elastic modulus Em(GPa) | 5.323 | Molar volume of methane at standard conditions Vm [L/mol] | 22.4 |

| Initial rock fracture porosity ϕf0 | 0.02 | Gas constant R[J/mol/K] | 8.413 |

| Initial matrix porosity ϕm0 | 0.045 | Gas extraction time t | 600 |

| Initial fracture permeability η0(m²) | 2.1×10−16 | Time delay d | 0.12 |

| Jump coefficient η | 200.96 | Damage coefficient λ | 0.82 |

| Initial cohesion C0(MPa) | 3.7 | Cohesion in plastic stage CR(MPa) | 0.85 |

| Internal friction angle (°) | 38 | Gas dynamic viscosity μ(Pa·s) | 1.88×10−5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).