Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

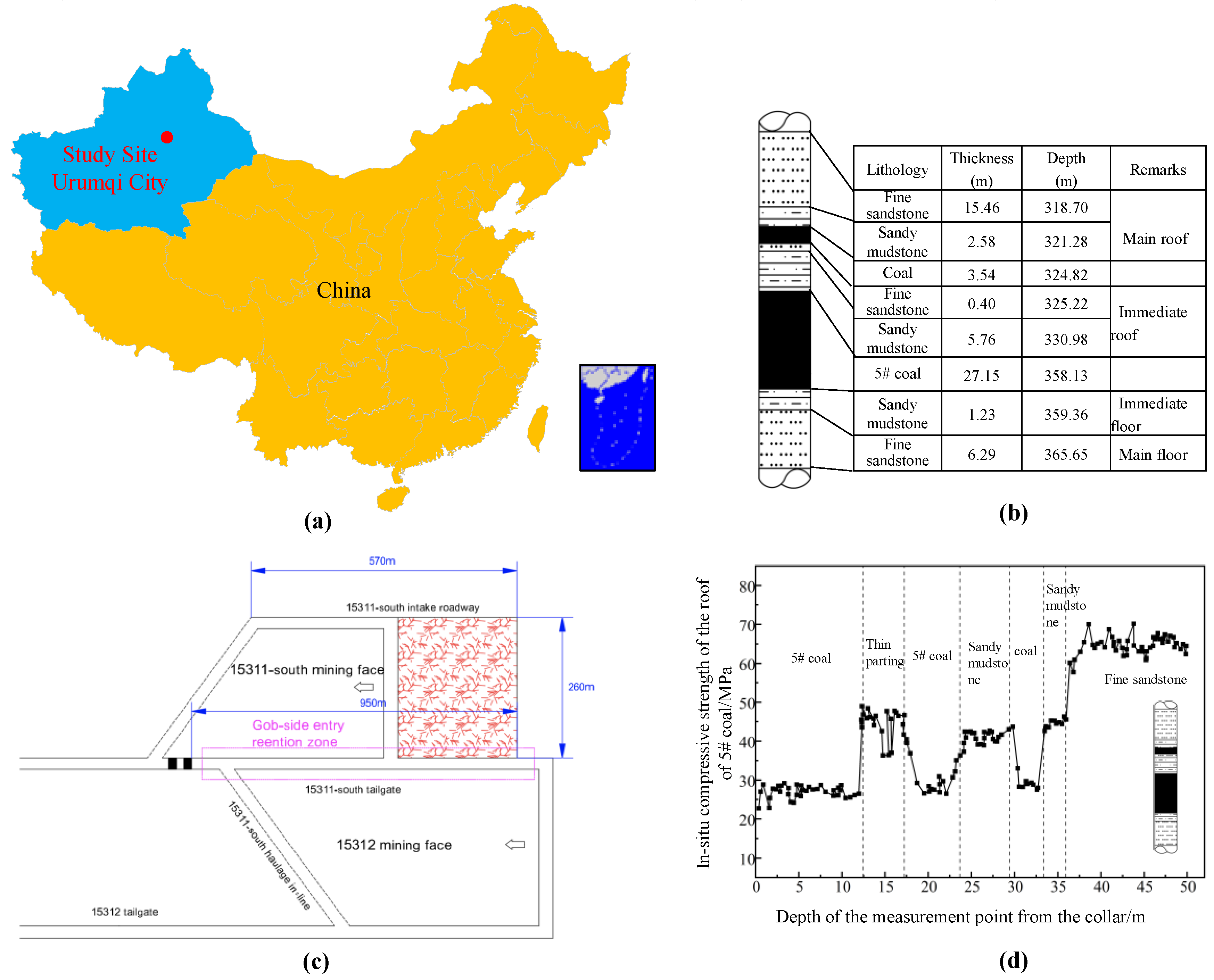

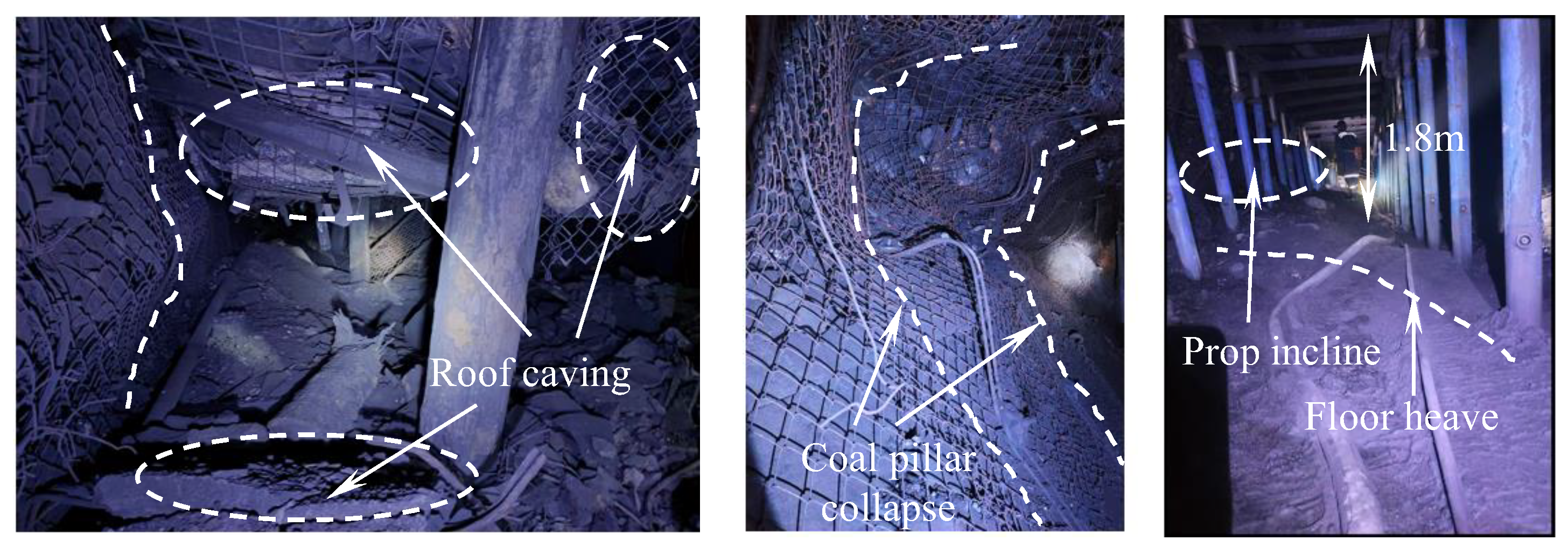

2. Case Study

3. Thick and Hard Overhanging Roof Effect in Longwall Quarries and Its Disaster-Causing Mechanism

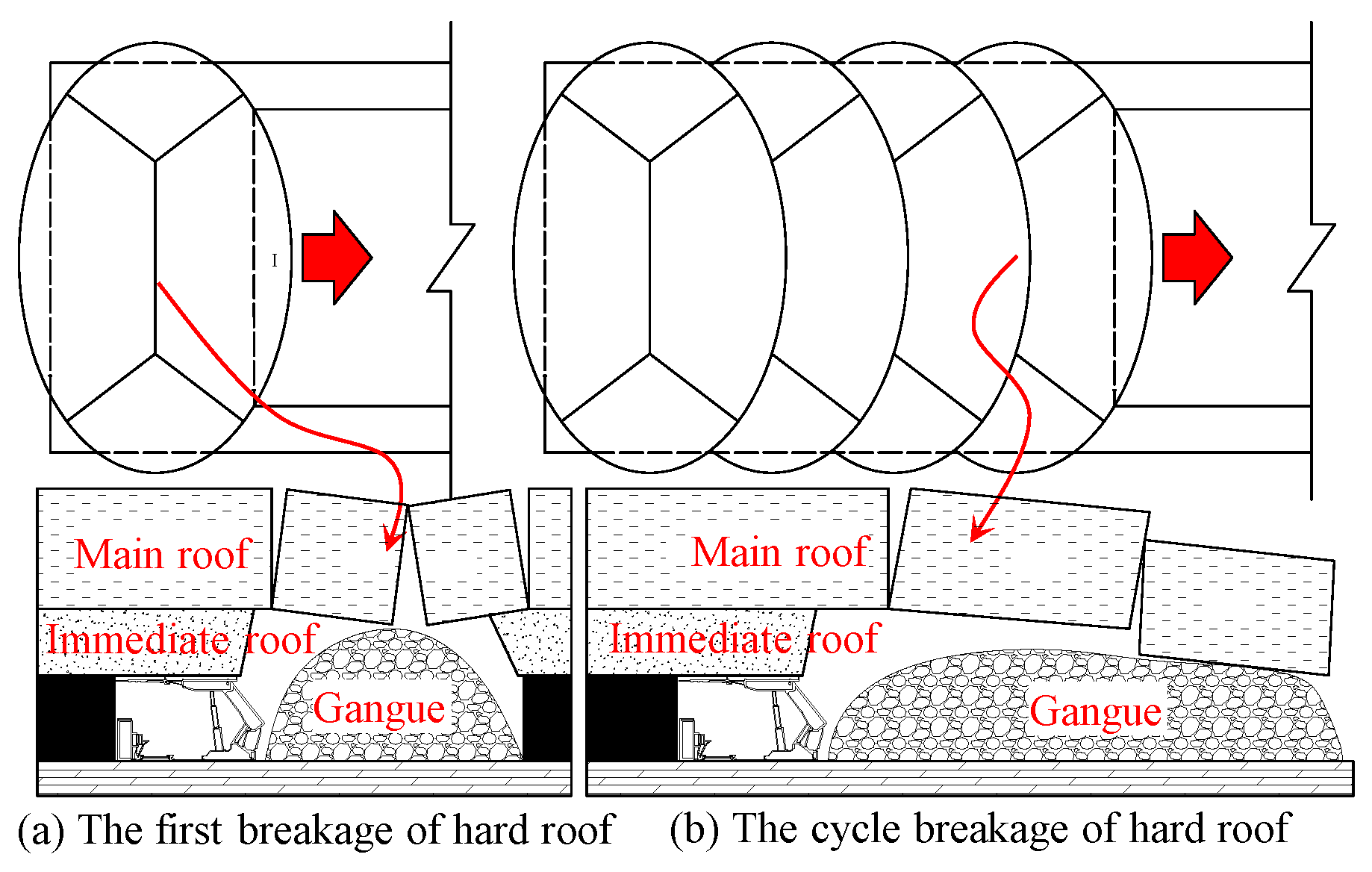

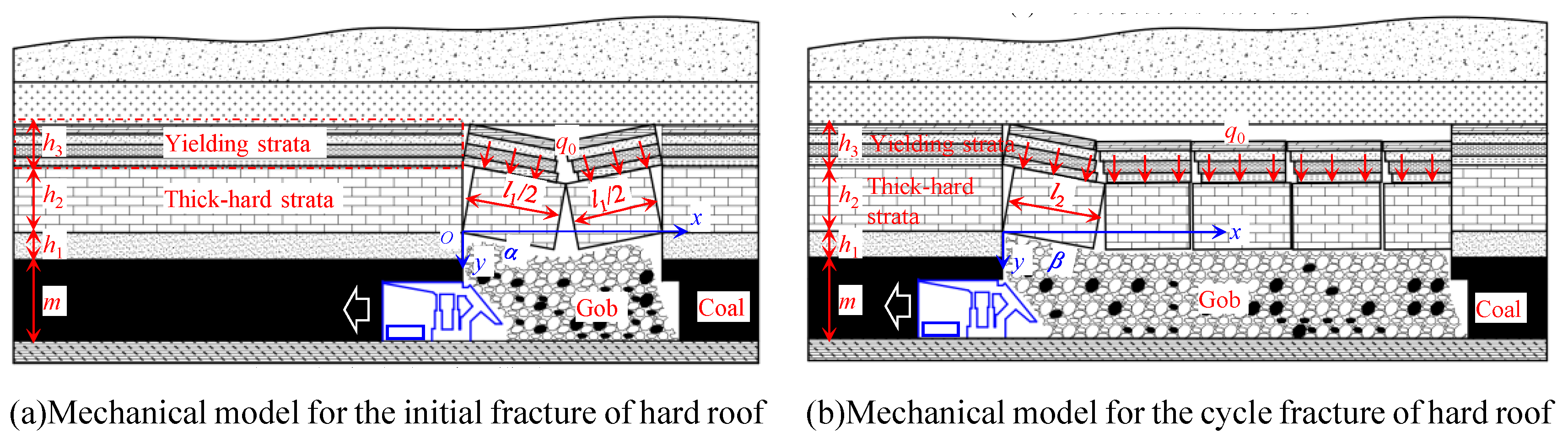

3.1. Suspended Roof Effect of Thick-Hard Main Roof

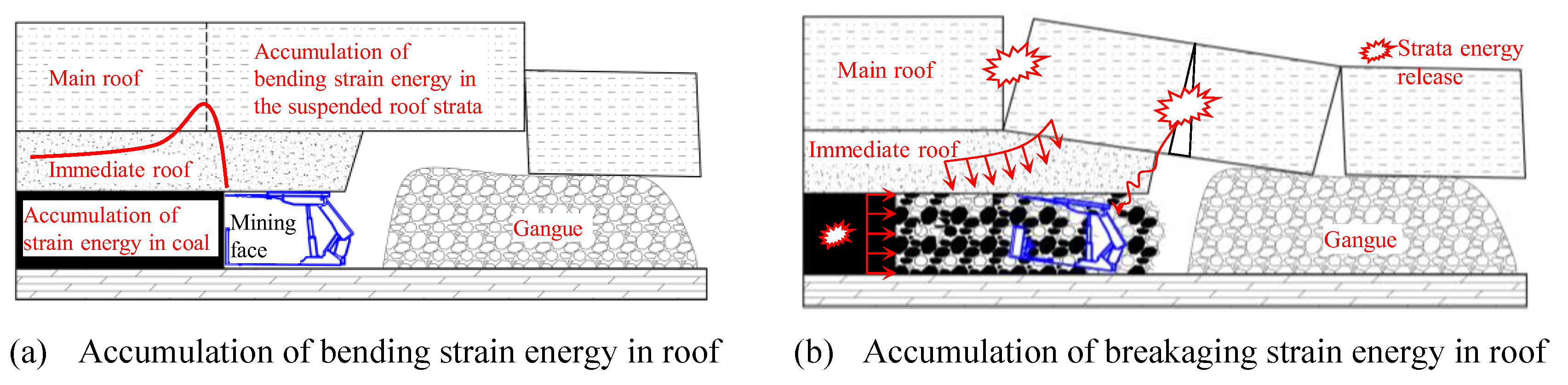

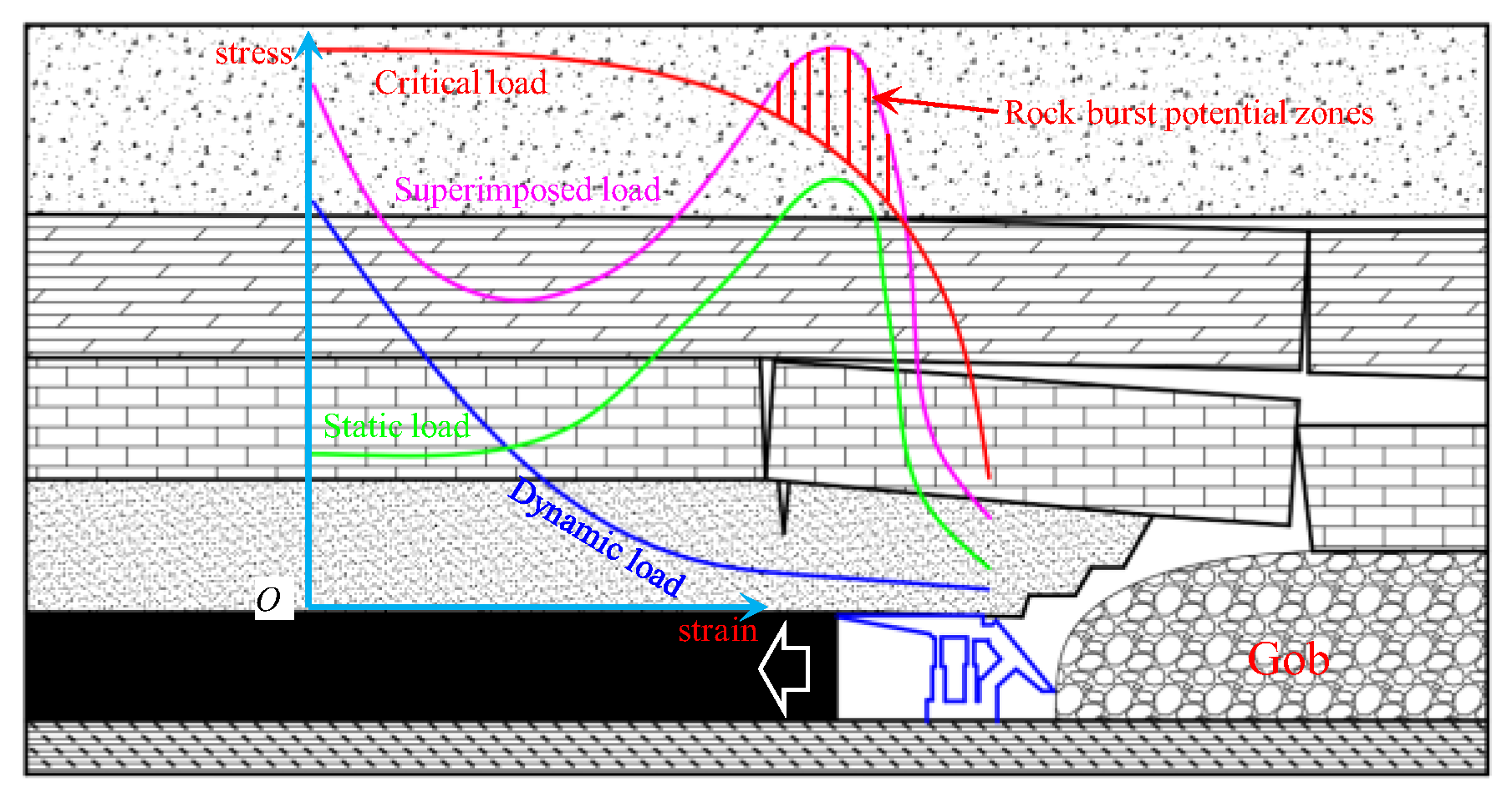

3.2. Disaster Mechanism of Thick Hard-Suspension Roof Breakage

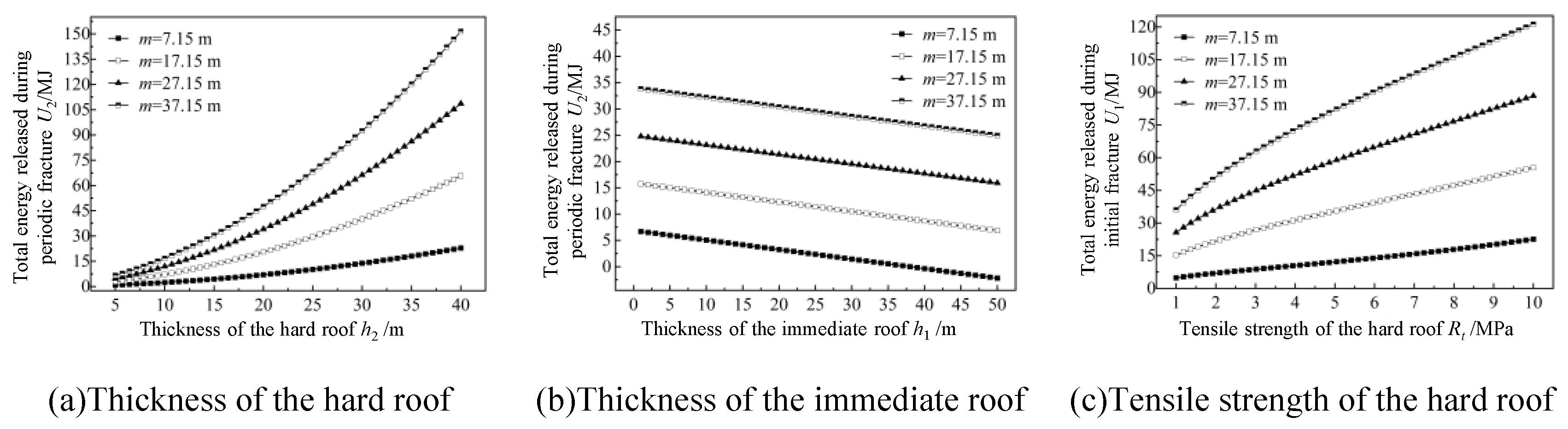

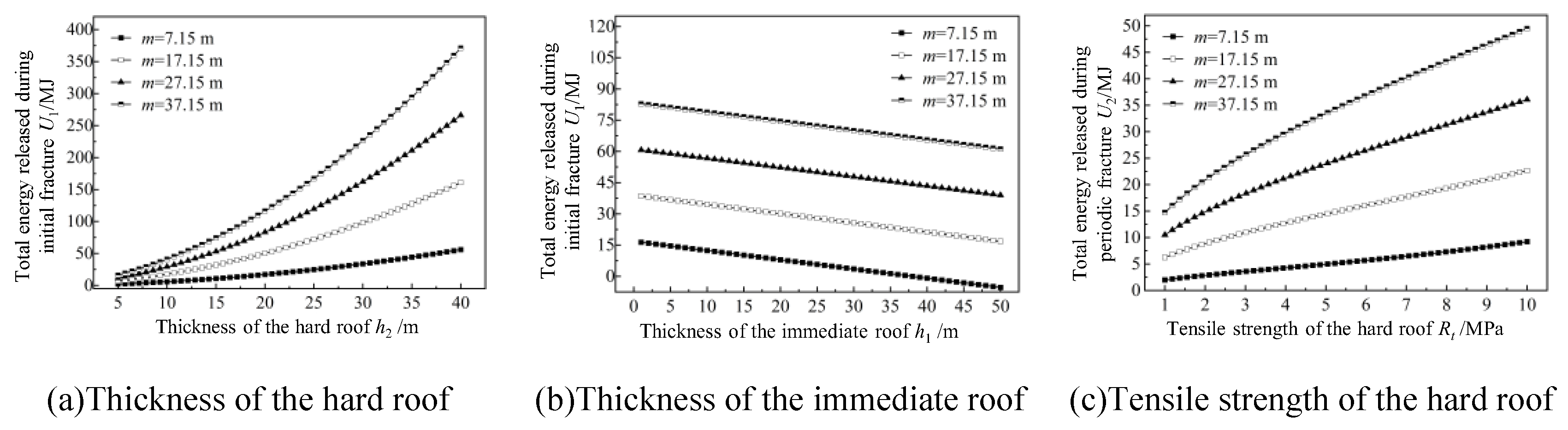

3.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Impact Mechanisms on Total Energy Release During Thick-Hard Roof Fracture

4. Field Practice of Hydraulic Fracturing in Fixed-Length Boreholes

4.1. Principles of Hydraulic Fracturing with Fixed-Length Drilling

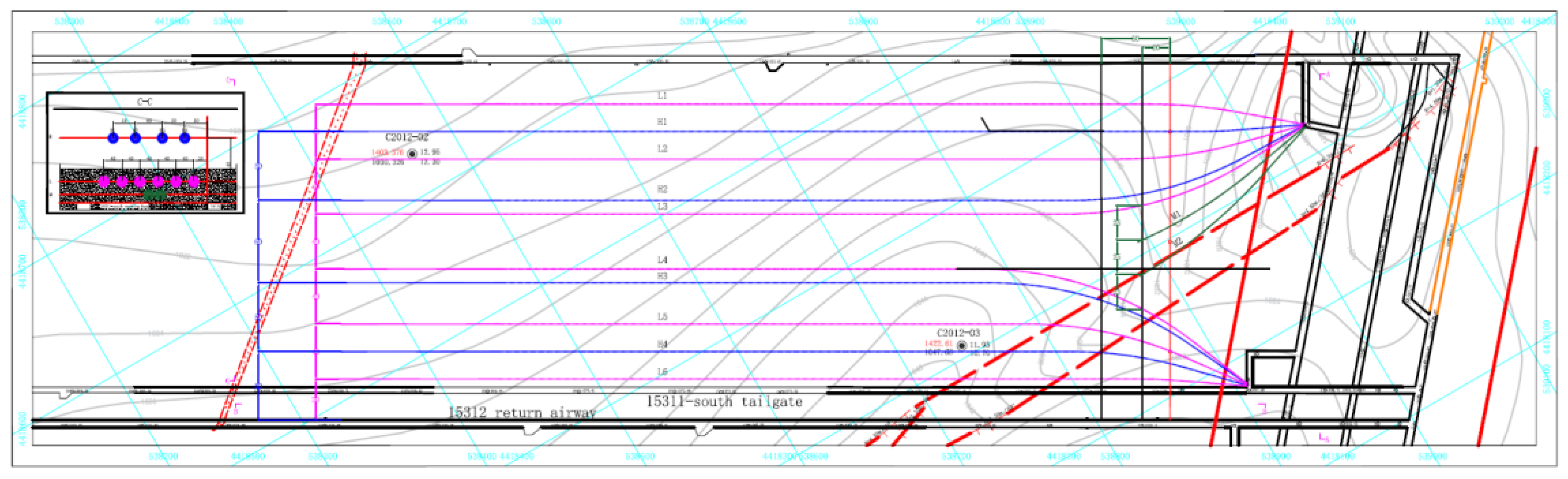

4.2. Hydraulic Fracturing Top Cutting and Pressure Relief Program

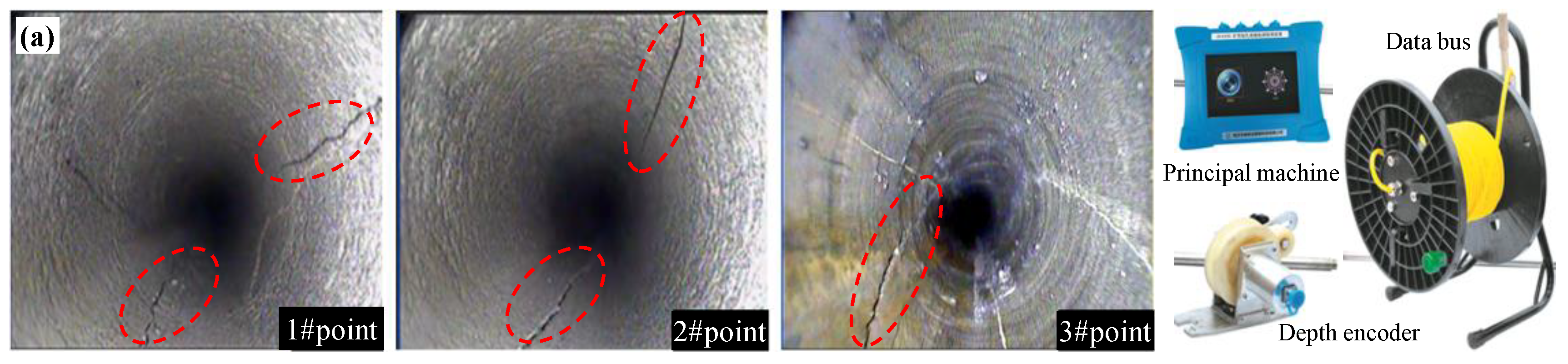

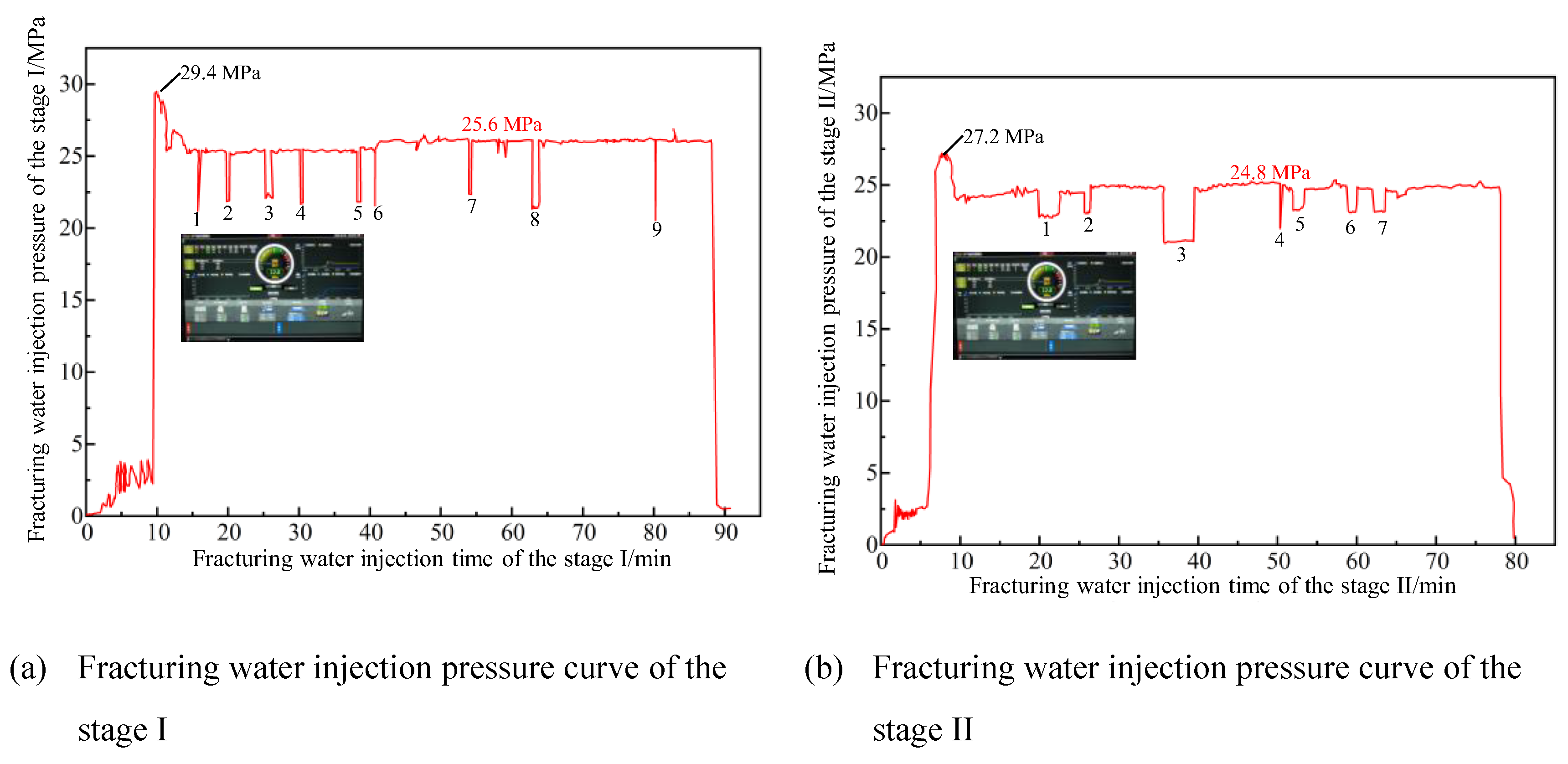

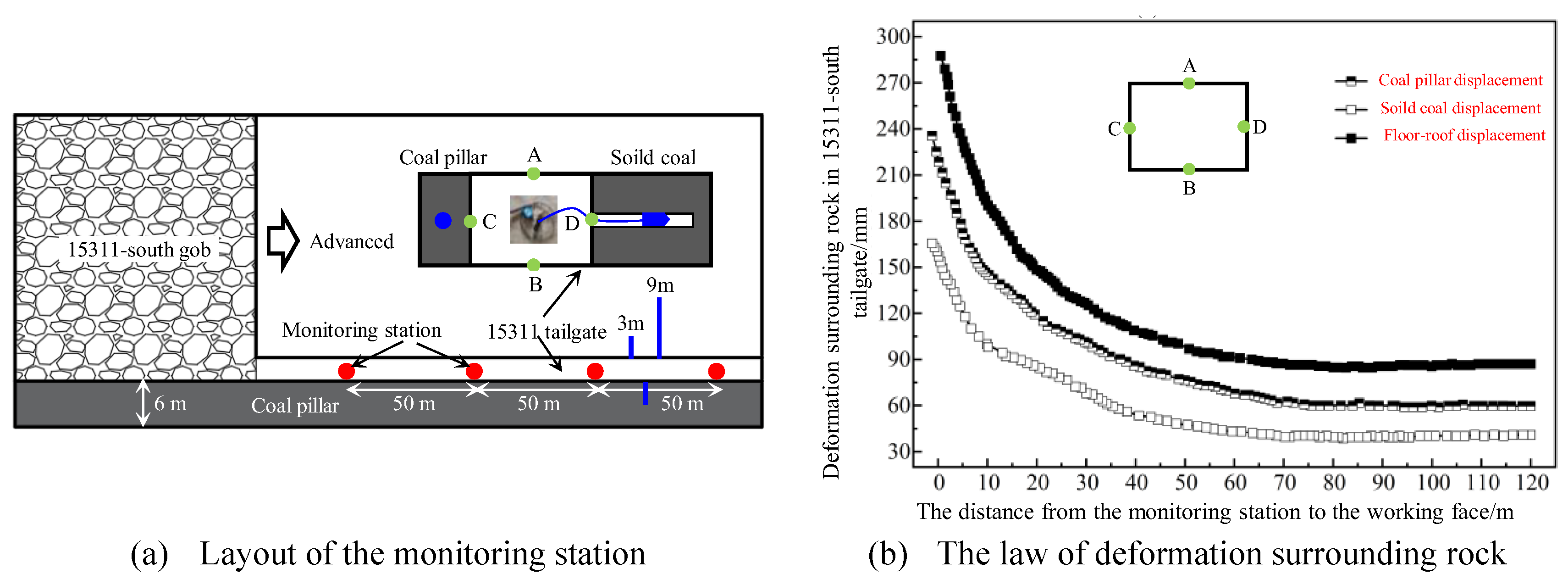

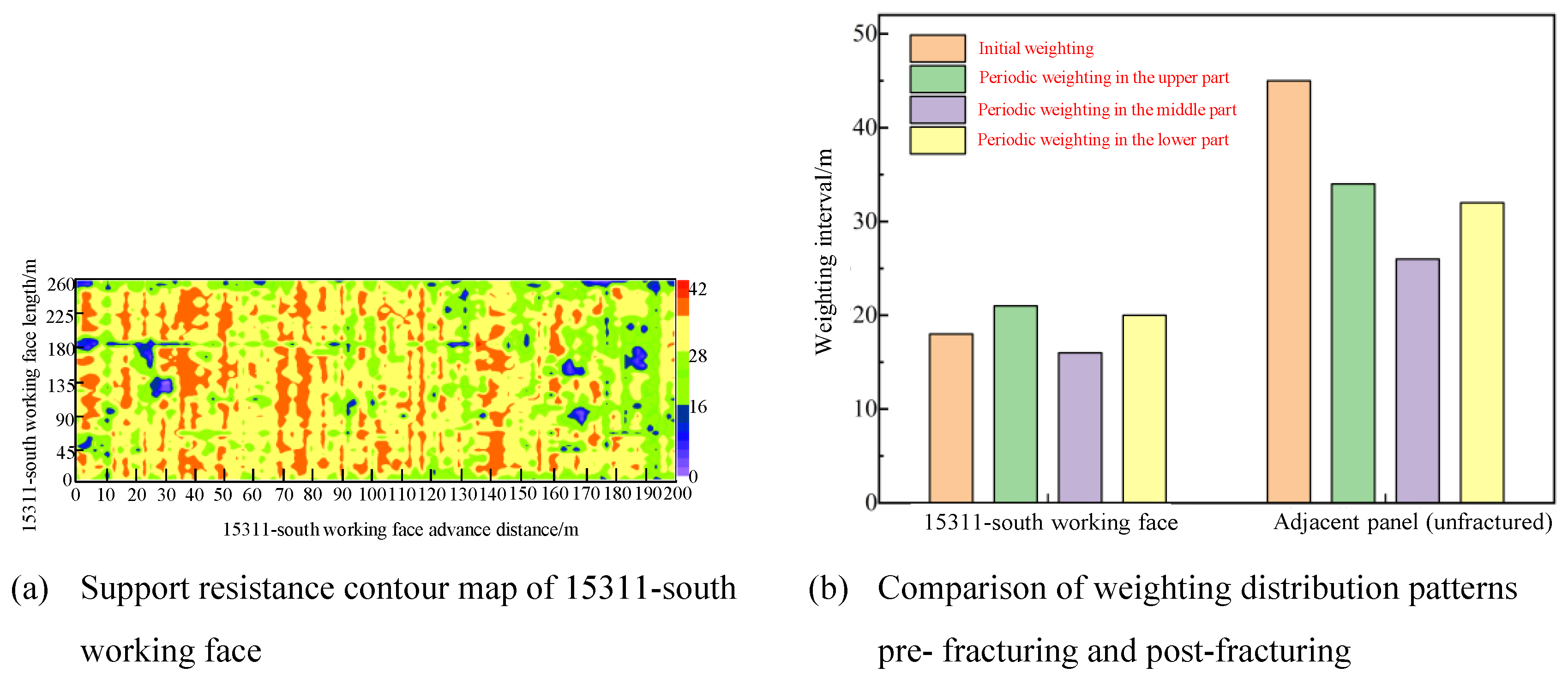

4.3. Hydraulic Fracturing Field Application Results

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z.G. Zhang, L.C. Dai, H.T. Sun, et al. Study on the Spatiotemporal Dynamic Evolution Law of a Deep Thick Hard Roof and Coal Seam[J]. Processes, 2023,11(11):3173. [CrossRef]

- B.B. Chen, C.Y. Liu, B. Wang. A case study of the periodic fracture control of a thick-hard roof based on deep-hole pre-splitting blasting[J]. ENERGY EXPLORATION & EXPLOITATION, 2022, 40(1):279-301. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhang, J. Bai, R. Wang, et al. Investigation on instability mechanism and control of abandoned roadways in coal pillars recovery face: A case study[J]. Underground Space, 2025, 20:119-139. [CrossRef]

- Q.W. Bu, M. Tu, X.Y. Zhang, et al. Analysis of Energy Accumulation and Dispersion Evolution of a Thick Hard Roof and Dynamic Load Response of the Hydraulic Support in a Large Space Stope[J]. FRONTIERS IN EARTH SCIENCE, 2022, 10:884361. [CrossRef]

- D.D. Qin, Z.C. Chang, Z. Xia. Experimental study on the strain energy evolution mechanism of thick and hard sandstone roof in Xinjiang Mining Area[J]. HELIYON, 2024, 10(2):e24594. [CrossRef]

- J.L. Jia, L.W. Cao, D.J. Zhang, et al. Study on the fracture characteristics of thick-hard limestone roof and its controlling technique[J]. ENVIRONMENTAL EARTH SCIENCES,2017, 76(17):605. [CrossRef]

- Y.B. Lu, S.H. Yan, K.Y. Zhou, et al. Structural quantification of multi-thick hard roof and strong ground pressure control in large mining height stope: a case study[J]. GEOMECHANICS AND GEOPHYSICS FOR GEO-ENERGY AND GEO-RESOURCES, 2025, 11(1):56. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhong, W.Z. Chen, W.S. Zhao, et al. Monitoring and evaluation of segmented hydraulic fracturing effect in rock burst prevention on hard roof of coal mine[J]. Journal of Central South University (Science and Technology),2022, 53(7):2582-2593.

- L.M. Dou, J.L. Kan, X.W. Li, et al. Study on prevention technology of rock burst by break-tip blasting and its effect estimation[J]. Coal Science and Technology,2020,48(1):24-32.

- B. Yu, T.J. Kuang, J.X. Yang, et al. Analysis of overburden structure and evolution characteristics of hard roof mining in extremely thick coal seam[J]. Coal Science and Technology, 2023,51(1):95-104. [CrossRef]

- H.P. Kang, Y.J. Feng, Z. Zhang, et al. Hydraulic fracturing technology with directional boreholes for strata control in underground coal mines and its application[J]. Coal Science and Technology,2023,51(1):31-44. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ju, Y.M. Yang, J.L. Chen, et al. 3D reconstruction of low-permeability heterogeneous glutenites and numerical simulation of hydraulic fracturing behavior[J]. China Science Bulletin, 2016,61(1):82-93. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO Yixin, LING Chunwei, LIU Bin, et al. Fracture evolution and energy dissipation of overlying strata in shallow-buried underground mining with ultra-high working face[J]. Journal of Mining & Safety Engineering, 2021,38(1):9-18+30.

- ZHAO Shankun. Mechanism and application of force-structure cooperative prevention and control on rockburst with deep hole roof pre-blasting[J]. Journal of China Coal Society ,2021,46(11):3419-3432.

- LING Chunwei, CHEN Qingtong, GUO Wenyan, et al. Study on overlying rock fissure and energy evolution law of high intensity mining working face adjacent to gob[J]. Safety in Coal Mines,2024,55(12):48-56.

- GAO Mingshi, XU Dong, HE Yongliang, et al. Investigation on the near-far field effect of rock burst subject to the breakage of thick and hard overburden[J]. Journal of Mining & Safety Engineering, 2022,39(2):215-226.

- ZHOU Kunyou, DOU Linming, LI Jiazhuo, et al. Effect of extra-thick key strata on the static and dynamic stress of rockburst[J]. Journal of Mining & Safety Engineering, 2024,41(5):908-919.

- WANG Wanjie, GAO Fuqiang. Study of the evolution of mining-induced fractures with longwall face proceeds-insight from physical and numerical modeling[J]. Journal of Mining and Strata Control Engineering, ,2023,5(2):17-26. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Fuqiang, Stead, Doug, Kang, Hongpu, Numerical Simulation of Squeezing Failure in a Coal Mine Roadway due to Mining-Induced Stresses, Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering.2015;48(4):1635-1645. [CrossRef]

- PANG Lining, HU Quanhong, JING Judong, et al. Regional pressure relief technology with directional hydraulic fracturing of deep buried thick hard roof working face[J]. Coal Engineering, 2023,55(10):67-73.

| Influencing Factors | Variables | Value |

| The thickness of immediate roof | h1 | 12.28 m |

| The density of hard roof | ρ2 | 2500 kg/m3 |

| The elastic modulus of hard roof | E | 6.4 GPa |

| The thickness of hard roof | h2 | 15.46 m |

| The mining height of coal seam | m | 27.15 m |

| Overburden load on hard roof | q0 | 600 kPa |

| The tensile strength of hard roof | Rt | 4.54 MPa |

| The bulking factor of immediate roof | k | 1.2 |

| The density of overburden strata | ρ3i | 2400 kg/m3 |

| The thickness of overburden strata | h3i | 14.56 m |

| Borehole number | Initial hole azimuth(°) | Initial hole dip angle(°) | Target azimuth(°) | Borehole diameter(mm) | Start point(m) | End point(m) | Fracturing stage(m) | Fracturing zone(m) |

| H1 Borehole | 295.5 | 10 | 300.15 | 120 | 0 | 705 | 150-705 | 48m |

| H2 Borehole | 272 | 10 | 0 | 717 | 162-717 | |||

| L1 Borehole | 310.5 | 7 | 0 | 699 | 150-699 | 15m | ||

| L2 Borehole | 284.5 | 7 | 0 | 705 | 150-705 | |||

| L3 Borehole | 268 | 7 | 0 | 717 | 162-717 | |||

| M1 Borehole | 260 | 10 | 0 | 150 | - | 6m | ||

| M2 Borehole | 252 | 10 | 0 | 165 | - | |||

| H3 Borehole | 335 | 10 | 0 | 681 | 126-681 | 48m | ||

| H4 Borehole | 316 | 10 | 0 | 669 | 114-669 | |||

| L4 Borehole | 338 | 7 | 0 | 681 | 126-681 | 15m | ||

| L5 Borehole | 324 | 7 | 0 | 669 | 114-669 | |||

| L6 Borehole | 304.5 | 7 | 0 | 663 | 108-663 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).