Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

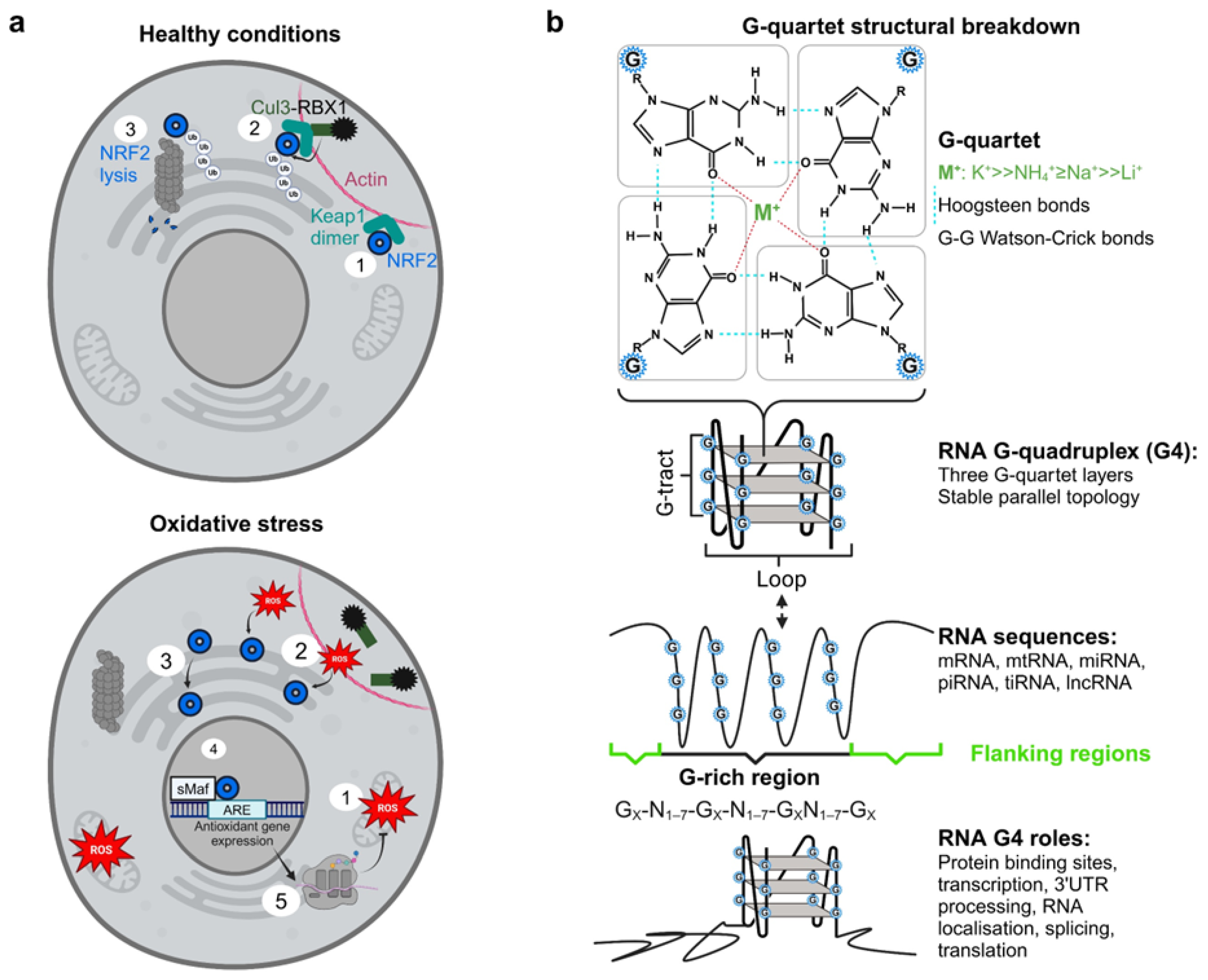

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In Vitro Transcription and Purification of NRF2 5’ UTR RNA

2.2. 5’ End Labelling of RNA Oligonucleotides

2.3. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

2.4. Fluorescence Assays

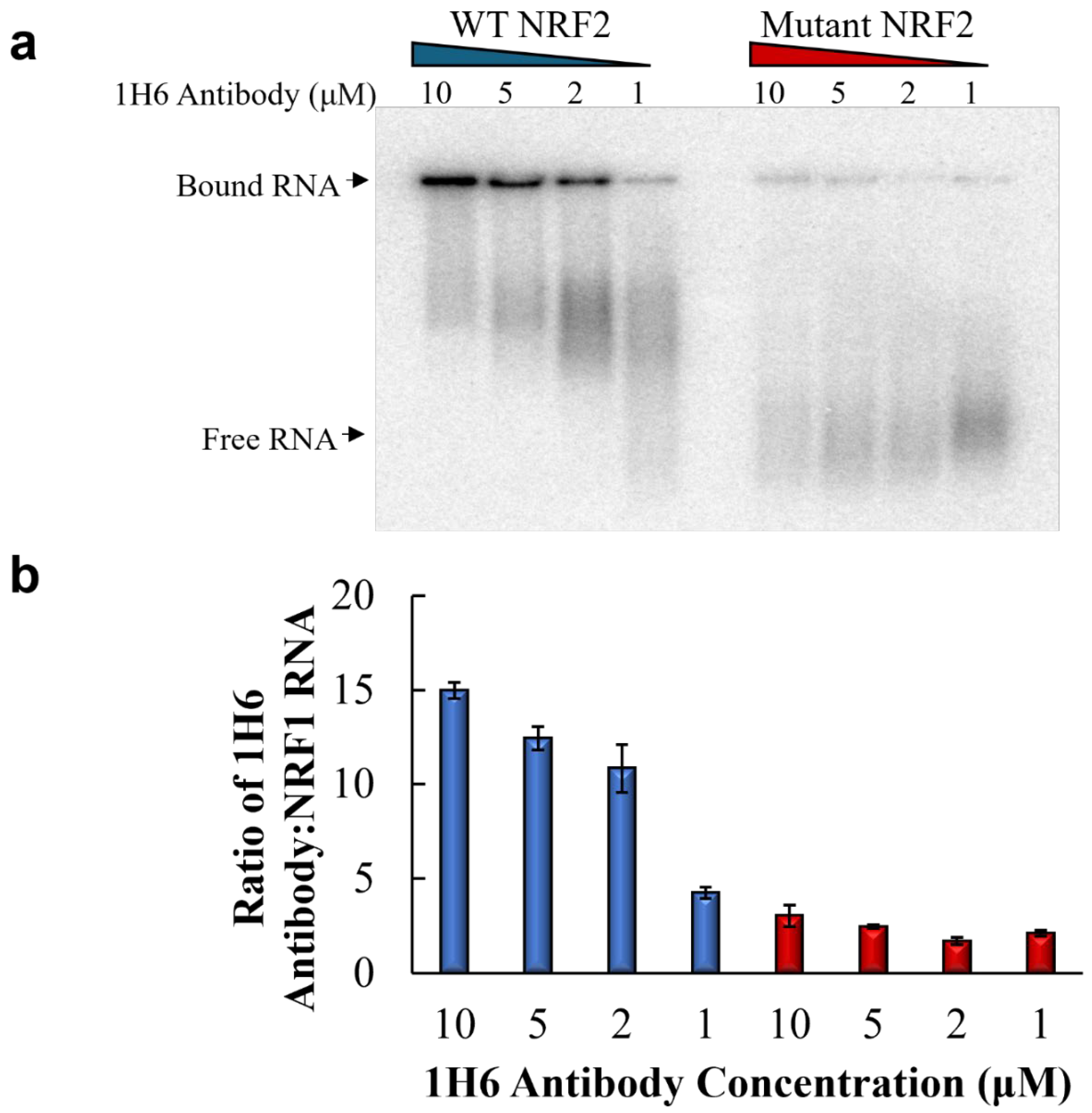

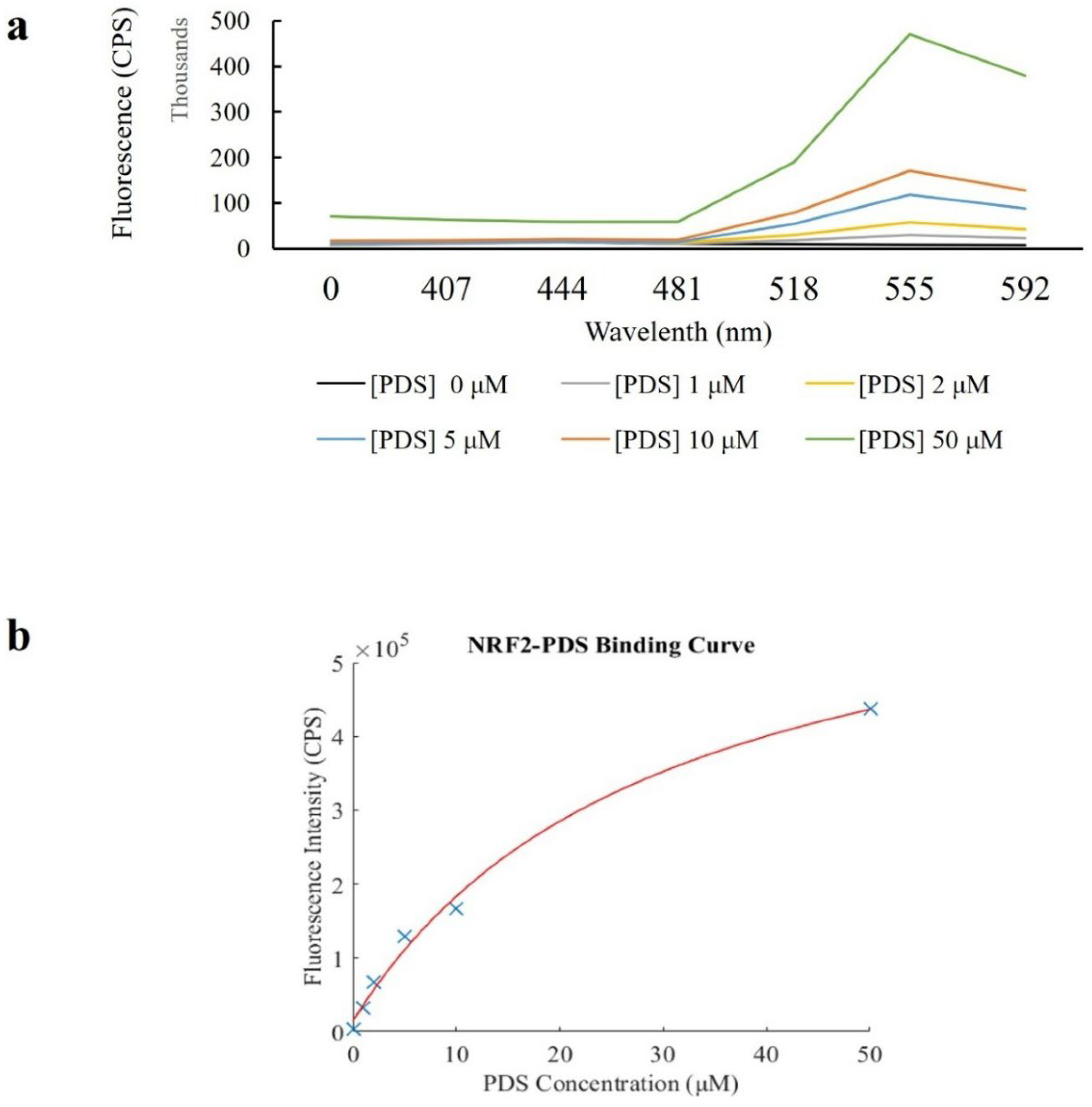

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

References

- Boo SH, Kim YK. The emerging role of RNA modifications in the regulation of mRNA stability. Vol. 52, Experimental and Molecular Medicine. Springer Nature; 2020. p. 400–8.

- Leppek, K; Byeon, GW; Kladwang, W; Wayment-Steele, HK; Kerr, CH; Xu, AF; et al. Combinatorial optimization of mRNA structure, stability, and translation for RNA-based therapeutics. Nat Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppek K, Das R, Barna M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Vol. 19, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. Nature Publishing Group; 2018. p. 158–74.

- Chang, JW; Zhang, W; Yeh, HS; De Jong, EP; Jun, S; Kim, KH; et al. MRNA 3′-UTR shortening is a molecular signature of mTORC1 activation. Nat Commun. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narula, A; Ellis, J; Taliaferro, JM; Rissland, OS. Coding regions affect mRNA stability in human cells. 2019. Available online: http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.

- Buxbaum AR, Haimovich G, Singer RH. In the right place at the right time: Visualizing and understanding mRNA localization. Vol. 16, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. Nature Publishing Group; 2015. p. 95–109.

- Noller HF. Evolution of protein synthesis from an RNAworld. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012, 4.

- Cetnar, DP; Hossain, A; Vezeau, GE; Salis, HM. Predicting synthetic mRNA stability using massively parallel kinetic measurements, biophysical modeling, and machine learning. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 9601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, L; Mao, Y; Ji, Q; Dersh, D; Yewdell, JW; Qian, SB. Decoding mRNA translatability and stability from 5’UTR [Internet]. 2020. Available online: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.03.13.990887.

- Wei, W; Gao, W; Li, Q; Liu, Y; Chen, H; Cui, Y; et al. Comprehensive characterization of posttranscriptional impairment-related 3′-UTR mutations in 2413 whole genomes of cancer patients. NPJ Genom Med. 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Y; Yu, D; Li, Y; Huang, K; Shen, Y; Cong, L; et al. A 5’ UTR Language Model for Decoding Untranslated Regions of mRNA and Function Predictions [Internet]. 2023. Available online: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2023.10.11.561938.

- The role of the 5′ untranslated region of an mRNA in translation regulation during development.

- Ryczek, N; Łyś, A; Makałowska, I. The Functional Meaning of 5′UTR in Protein-Coding Genes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nostrand, EL; Freese, P; Pratt, GA; Wang, X; Wei, X; Xiao, R; et al. A large-scale binding and functional map of human RNA-binding proteins. Nature 2020, 583, 711–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostak, E; Gebauer, F. Translational control by 3’-UTR-binding proteins. Brief Funct Genomics 2013, 12, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steri, M; Idda, ML; Whalen, MB; Orrù, V. Genetic variants in mRNA untranslated regions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, RK; West, JD; Jiang, Y; Fogarty, EA; Grimson, A. Robust partitioning of microRNA targets from downstream regulatory changes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 9724–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiltschewskij, DJ; Harrison, PF; Fitzsimmons, C; Beilharz, TH; Cairns, MJ. Extension of mRNA poly(A) tails and 3′UTRs during neuronal differentiation exhibits variable association with post-transcriptional dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 8181–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strober, BJ; Elorbany, R; Rhodes, K; Krishnan, N; Tayeb, K; Battle, A; et al. Dynamic genetic regulation of gene expression during cellular differentiation HHS Public Access. Science (1979) [Internet] 2019, 364, 1287–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova AT, Kostov R V., Kazantsev AG. The role of Nrf2 signaling in counteracting neurodegenerative diseases. Vol. 285, FEBS Journal. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2018. p. 3576–90.

- Papp, D; Lenti, K; Módos, D; Fazekas, D; Dúl, Z; Türei, D; et al. The NRF2-related interactome and regulome contain multifunctional proteins and fine-tuned autoregulatory loops. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 1795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T; Nioi, P; Pickett, CB. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 13291–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denicola, GM; Karreth, FA; Humpton, TJ; Gopinathan, A; Wei, C; Frese, K; et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan HK, Olayanju A, Goldring CE, Park BK. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of regulation. Vol. 85, Biochemical Pharmacology. Elsevier Inc.; 2013. p. 705–17.

- ung BJ, Yoo HS, Shin S, Park YJ, Jeon SM. Dysregulation of NRF2 in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Vol. 26, Biomolecules and Therapeutics. Korean Society of Applied Pharmacology; 2018. p. 57–68.

- Dhyani N, Tian C, Gao L, Rudebush TL, Zucker IH. Nrf2-Keap1 in Cardiovascular Disease: Which Is the Cart and Which the Horse? Vol. 39, Physiology (Bethesda, Md.). 2024. p. 0.

- Tucci, P; Lattanzi, R; Severini, C; Saso, L. Nrf2 Pathway in Huntington’s Disease (HD): What Is Its Role? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha S, Buttari B, Profumo E, Tucci P, Saso L. A Perspective on Nrf2 Signaling Pathway for Neuroinflammation: A Potential Therapeutic Target in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Vol. 15, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2022.

- Wang, RS; Maron, BA; Loscalzo, J. Multiomics Network Medicine Approaches to Precision Medicine and Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023, 43, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurisic V. Multiomic analysis of cytokines in immuno-oncology. Vol. 17, Expert Review of Proteomics. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2020. p. 663–74.

- Ngo, V; Duennwald, ML. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, SO; Fan, CY; Yeoman, K; Wakefield, J; Ramabhadran, R. NRF2 Oxidative Stress Induced by Heavy Metals is Cell Type Dependent [Internet]. Available online: http://www.ifti.org/cgi-.

- Kensler, TW; Wakabayashi, N; Biswal, S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2007, 47, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurtaux, T; Bouvier, DS; Benani, A; Helgueta Romero, S; Frauenknecht, KBM; Mittelbronn, M; et al. Normal and Pathological NRF2 Signalling in the Central Nervous System. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F; Ru, X; Wen, T. NRF2, a transcription factor for stress response and beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzner, WG; da Silva Sousa, LR; Gutierrez, K; de Macedo, MP; Currin, L; Perecin, F; et al. NRF2 attenuation aggravates detrimental consequences of metabolic stress on cultured porcine parthenote embryos. Sci Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R; Jia, Z; Zhu, H. Regulation of Nrf2 Signaling. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D; Gabrielian, A; Wheeler, D; Usdin, K. The roles of Sp1, Sp3, USF1/USF2 and NRF-1 in the regulation and three-dimensional structure of the Fragile X mental retardation gene promoter. Biochem. J. 2005, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S; Sugimoto, N. Watson-Crick versus Hoogsteen Base Pairs: Chemical Strategy to Encode and Express Genetic Information in Life. Acc Chem Res. 2021, 54, 2110–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumard A, Hennecke M, Hauser H, Nourbakhsh M. Translation of NRF mRNA Is Mediated by Highly Efficient Internal Ribosome Entry. Vol. 20. 2000.

- Lee, DSM; Ghanem, LR; Barash, Y. Integrative analysis reveals RNA G-quadruplexes in UTRs are selectively constrained and enriched for functional associations. Nat Commun. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otovat, F; Bozorgmehr, MR; Mahmoudi, A; Morsali, A. Porphyrin-based ligand interaction with G-quadruplex: Metal cation effects. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2023, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaratnam, S; Torrey, ZR; Calabrese, DR; Banco, MT; Yazdani, K; Liang, X; et al. Investigating the NRAS 5′ UTR as a target for small molecules. Cell Chem Biol. 2023, 30, 643–657.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, SC; Zhang, J; Strom, J; Yang, D; Dinh, TN; Kappeler, K; et al. G-Quadruplex in the NRF2 mRNA 5′ Untranslated Region Regulates De Novo NRF2 Protein Translation under Oxidative Stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu S, Jiang L, Lei L, Fu C, Huang J, Hu Y, et al. Crosstalk between G-quadruplex and ROS. Vol. 14, Cell Death and Disease. Springer Nature; 2023.

- Zang H, Mathew RO, Cui T. The Dark Side of Nrf2 in the Heart. Vol. 11, Frontiers in Physiology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2020.

- Brüschweiler, S; Fuchs, JE; Bader, G; McConnell, DB; Konrat, R; Mayer, M. A Step toward NRF2-DNA Interaction Inhibitors by Fragment-Based NMR Methods. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 3576–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poganik, JR; Long, MJC; Disare, MT; Liu, X; Chang, SH; Hla, T; et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of Nrf2-mRNA by the mRNA-binding proteins HuR and AUF1. FASEB Journal. 2019, 33, 14636–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim YS, Kimball SR, Piskounova E, Begley TJ, Hempel N. Stress response regulation of mRNA translation: Implications for antioxidant enzyme expression in cancer. Vol. 121, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2024.

- Akl, MG; Li, L; Baccetto, R; Phanse, S; Zhang, Q; Trites, MJ; et al. Complementary gene regulation by NRF1 and NRF2 protects against hepatic cholesterol overload. Cell Rep. 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebay LE, Robertson H, Durant ST, Vitale SR, Penning TM, Dinkova-Kostova AT, et al. Mechanisms of activation of the transcription factor Nrf2 by redox stressors, nutrient cues, and energy status and the pathways through which it attenuates degenerative disease. Vol. 88, Free Radical Biology and Medicine. Elsevier Inc.; 2015. p. 108–46.

- Neupane, A; Chariker, JH; Rouchka, EC. Structural and Functional Classification of G-Quadruplex Families within the Human Genome. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskiewicz J, Sarzynska J, Szachniuk M. How bioinformatics resources work with G4 RNAs. Vol. 22, Briefings in Bioinformatics. Oxford University Press; 2021.

- Cagirici, HB; Budak, H; Sen, TZ. G4Boost: a machine learning-based tool for quadruplex identification and stability prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikin O, D’Antonio L, Bagga PS. QGRS Mapper: A web-based server for predicting G-quadruplexes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 Jul;34(WEB. SERV. ISS.).

- Brázda, V; Kolomazník, J; Lýsek, J; Bartas, M; Fojta, M; Šťastný, J; et al. G4Hunter web application: A web server for G-quadruplex prediction. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 3493–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadekar, SM; Nilavar, NM; Paranjape, A; Das, K; Raghavan, SC. Characterization of G-quadruplex antibody reveals differential specificity for G4 DNA forms. DNA Research 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lago, S; Nadai, M; Rossetto, M; Richter, SN. Surface Plasmon Resonance kinetic analysis of the interaction between G-quadruplex nucleic acids and an anti-G-quadruplex monoclonal antibody. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2018, 1862, 1276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellman, LM; Fried, MG. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for detecting protein-nucleic acid interactions. Nat Protoc. 2007, 2, 1849–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y; Gan, T; Fang, T; Zhao, Y; Luo, Q; Liu, X; et al. G-quadruplex inducer/stabilizer pyridostatin targets SUB1 to promote cytotoxicity of a transplatinum complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 3070–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, R; Talarico, C; Moraca, F; Costa, G; Romeo, I; Ortuso, F; et al. Molecular recognition of a carboxy pyridostatin toward G-quadruplex structures: Why does it prefer RNA? Chem Biol Drug Des. 2017, 90, 919–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, LY; Ma, TZ; Zeng, YL; Liu, W; Mao, ZW. Structural Basis of Pyridostatin and Its Derivatives Specifically Binding to G-Quadruplexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2022, 144, 11878–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X; Spiegel, J; Martínez Cuesta, S; Adhikari, S; Balasubramanian, S. Chemical profiling of DNA G-quadruplex-interacting proteins in live cells. Nat Chem. 2021, 13, 626–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M; Lei, L; Egli, M. Label-Free Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for Measuring Dissociation Constants of Protein-RNA Complexes. Curr Protoc Nucleic Acid Chem. 2019, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffler, MA; Walters, RD; Kugel, JF. Using electrophoretic mobility shift assays to measure equilibrium dissociation constants: GAL4-p53 binding DNA as a model system. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 2012, 40, 383–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K; Akiyama, M; Sakakibara, Y. RNA secondary structure prediction using deep learning with thermodynamic integration. Nat Commun. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horspool, DR; Coope, RJ; Holt, RA. Efficient assembly of very short oligonucleotides using T4 DNA Ligase. BMC Res Notes 2010, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller$ CW, Richardson CC. Initiation of DNA Replication at the Primary Origin of Bacteriophage T7 by Purified Proteins SITE AND DIRECTION OF INITIAL DNA SYNTHESIS*. Vol. 260, THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 1985.

- Porecha R, Herschlag D. RNA radiolabeling. In: Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press Inc.; 2013. p. 255–79.

- Yu, L; Verwilst, P; Shim, I; Zhao, YQ; Zhou, Y; Kim, JS. Fluorescent visualization of nucleolar g-quadruplex rna and dynamics of cytoplasm and intranuclear viscosity. CCS Chemistry 2021, 3, 2725–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Oca MC, Quadri R, Bernini GM, Menin L, Grasso L, Rondelli D, et al. Spotlight on G-Quadruplexes: From Structure and Modulation to Physiological and Pathological Roles. Vol. 25, International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024.

- Liu, LY; Ma, TZ; Zeng, YL; Liu, W; Mao, ZW. Structural Basis of Pyridostatin and Its Derivatives Specifically Binding to G-Quadruplexes. J Am Chem Soc. 2022, 144, 11878–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y; Deng, Z; Vladimirova, O; Gulve, N; Johnson, FB; Drosopoulos, WC; et al. TERRA G-quadruplex RNA interaction with TRF2 GAR domain is required for telomere integrity. Sci Rep. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y; Kubo, H; Kawauchi, K; Miyoshi, D. NRAS DNA G-quadruplex-targeting molecules for sequence-selective enzyme inhibition. Chemical Communications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, XX; Wang, SQ; Gan, SQ; Liu, L; Zhong, MQ; Jia, MH; et al. A Small Ligand That Selectively Binds to the G-quadruplex at the Human Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Internal Ribosomal Entry Site and Represses the Translation. Front Chem. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouleau, SG; Garant, JM; Bolduc, F; Bisaillon, M; Perreault, JP. G-Quadruplexes influence pri-microRNA processing. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraj, GG; Pandey, S; Scaria, V; Maiti, S. Potential G-quadruplexes in the human long non-coding transcriptome. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 81–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, L; Herviou, P; Dassi, E; Cammas, A; Millevoi, S. G-Quadruplexes in RNA Biology: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 2021, 46, 270–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H; Zhang, R; Xiao, K; Yang, J; Sun, X. G-Quadruplex-Binding Proteins: Promising Targets for Drug Design. Biomolecules 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammas A, Desprairies A, Dassi E, Millevoi S. The shaping of mRNA translation plasticity by RNA G-quadruplexes in cancer progression and therapy resistance. Vol. 6, NAR Cancer. Oxford University Press; 2024.

- Herdy, B; Mayer, C; Varshney, D; Marsico, G; Murat, P; Taylor, C; et al. Analysis of NRAS RNA G-quadruplex binding proteins reveals DDX3X as a novel interactor of cellular G-quadruplex containing transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 11592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S; Jiang, L; Lei, L; Fu, C; Huang, J; Hu, Y; et al. Crosstalk between G-quadruplex and ROS. Cell Death and Disease 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharel, P; Ivanov, P. RNA G-quadruplexes and stress: emerging mechanisms and functions. Trends in Cell Biology 2024, 34, 771–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, HY; Huang, HL; Zhao, PP; Zhou, H; Qu, LH. Translational repression of cyclin D3 by a stable G-quadruplex in its 5′ UTR: Implications for cell cycle regulation. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 1099–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Drie, JH; Tong, L. Cryo-EM as a powerful tool for drug discovery. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S; Bugaut, A; Huppert, JL; Balasubramanian, S. An RNA G-quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene modulates translation. Nat Chem Biol. 2007, 3, 218–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, MJ; Basu, S. An unusually stable G-quadruplex within the 5′-UTR of the MT3 matrix metalloproteinase mRNA represses translation in eukaryotic cells. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 5313–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, MJ; Negishi, Y; Pazsint, C; Schonhoft, JD; Basu, S. An RNA G-quadruplex is essential for cap-independent translation initiation in human VEGF IRES. J Am Chem Soc. 2010, 132, 17831–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koukouraki, P; Doxakis, E. Constitutive translation of human a-synuclein is mediated by the 50-untranslated region. Open Biol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppek, K; Das, R; Barna, M. Functional 5′ UTR mRNA structures in eukaryotic translation regulation and how to find them. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2018, 19, 158–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, SC; Zhang, J; Strom, J; Yang, D; Dinh, TN; Kappeler, K; et al. G-Quadruplex in the NRF2 mRNA 5′ Untranslated Region Regulates De Novo NRF2 Protein Translation under Oxidative Stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2017, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhyani N, Tian C, Gao L, Rudebush TL, Zucker IH. Nrf2-Keap1 in Cardiovascular Disease: Which Is the Cart and Which the Horse? Vol. 39, Physiology (Bethesda, Md.). 2024. p. 0.

- Marion, D. An introduction to biological NMR spectroscopy. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics 2013, 12, 3006–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi-Appauh, N; Ralph, SF; van Oijen, AM; Spenkelink, LM. Understanding G-Quadruplex Biology and Stability Using Single-Molecule Techniques. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2023, 127, 5521–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, RK; Kumar, P; Halder, K; Verma, A; Kar, A; Parent, JL; et al. Metastases suppressor NM23-H2 interaction with G-quadruplex DNA within c-MYC promoter nuclease hypersensitive element induces c-MYC expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 172–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamzeeva, PN; Alferova, VA; Korshun, VA; Varizhuk, AM; Aralov, A V. 5’-UTR G-Quadruplex-Mediated Translation Regulation in Eukaryotes: Current Understanding and Methodological Challenges. Int J Mol Sci [Internet] 2025, 26. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39940956. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q; Liu, X; Xiong, W; Zhang, K; Shen, W; Zhang, Y; et al. Reducing CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects by optically controlled chemical modifications of guide RNA. Cell Chem Biol. 2024, 31, 1839–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, M; Kikuchi, M; Natsukawa, T; Shinobu, N; Imaizumi, T; Miyagishi, M; et al. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol. 2004, 5, 730–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S; Ali, A; Bhattacharya, S. Theoretical Insight into the Library Screening Approach for Binding of Intermolecular G-Quadruplex RNA and Small Molecules through Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation Studies. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2021, 125, 5489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerhoff, J; Warnecke, KR; Wang, K; Deng, N; Yang, D. Evaluating molecular docking software for small molecule binding to G-quadruplex DNA. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwood, PR; Yang, M; Lewis, G V.; Balaratnam, S; Yazdani, K; Schneekloth, JS. Competitive Microarray Screening Reveals Functional Ligands for the DHX15 RNA G-Quadruplex. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2024, 15, 814–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G; Tillo, D; Ray, S; Chang, TC; Schneekloth, JS; Vinson, C; et al. Custom G4 microarrays reveal selective G-quadruplex recognition of small molecule BMVC: A large-scale assessment of ligand binding selectivity. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-González, D; Pérez-Machado, G; Pallardó, F; Garrigues-Pelufo, TM; Cabrera-Pérez, MA. Send Orders of Reprints at reprints@benthamscience.net Computational Tools in the Discovery of New G-Quadruplex Ligands with Potential Anticancer Activity. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 2012, 12. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, A; Cudney, B. Optimization of crystallization conditions for biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun. 2014, 70, 1445–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, DK; Lukavsky, PJ. NMR solution structure determination of large RNA-protein complexes. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 2016, 97, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, P; Budhathoki, JB; Roy, WA; Balci, H. A practical guide to studying G-quadruplex structures using single-molecule FRET. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2017, 292, 483–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masson, T; Guetta, CL; Laigre, E; Cucchiarini, A; Duchambon, P; Teulade-Fichou, MP; et al. BrdU immuno-tagged G-quadruplex ligands: a new ligand-guided immunofluorescence approach for tracking G-quadruplexes in cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 12644–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiser, N; Fuks, C; Hengesbach, M. Cooperative analysis of structural dynamics in RNA-protein complexes by single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer spectroscopy. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, JA; Pothula, KR; Schröder, GF. Integrating cryo-EM and NMR data. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2020, 61, 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsen, RC; Trent, JO. G-quadruplex virtual drug screening: A review. Biochimie 2018, 152, 134–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schock Vaiani J, Broekgaarden M, Coll JL, Sancey L, Busser B. In vivo vectorization and delivery systems for gene therapies and RNA-based therapeutics in oncology. Nanoscale. Royal Society of Chemistry; 2025.

- Birrer, MJ; Moore, KN; Betella, I; Bates, RC. Antibody-Drug Conjugate-Based Therapeutics: State of the Science. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 538–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biffi, G; Di Antonio, M; Tannahill, D; Balasubramanian, S. Visualization and selective chemical targeting of RNA G-quadruplex structures in the cytoplasm of human cells. Nat Chem. 2014, 6, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L; Jea, JDY; Wang, Y; Chao, PW; Yen, L. Control of mammalian gene expression by modulation of polyA signal cleavage at 5′ UTR. Nat Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1454–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, AJ; de Jong, L; Kennedy, MA. The Dynamic Regulation of G-Quadruplex DNA Structures by Cytosine Methylation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorlíčková, M; Kejnovská, I; Sagi, J; Renčiuk, D; Bednářová, K; Motlová, J; et al. Circular dichroism and guanine quadruplexes. Methods 2012, 57, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S; Jiang, L; Lei, L; Fu, C; Huang, J; Hu, Y; et al. Crosstalk between G-quadruplex and ROS. Cell Death and Disease 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M; Li, JY; Zhang, MJ; Li, JH; Huang, JT; You, PD; et al. G-quadruplex binder pyridostatin as an effective multi-target ZIKV inhibitor. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021, 190, 178–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R; Miller, KM; Forment, J V.; Bradshaw, CR; Nikan, M; Britton, S; et al. Small-molecule-induced DNA damage identifies alternative DNA structures in human genes. Nat Chem Biol. 2012, 8, 301–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng R, Huang Q, Wang L, Qiao G, Huang X, Jiang J, et al. G-quadruplex RNA Based PROTAC Enables Targeted Degradation of RNA Binding Protein FMRP for Tumor Immunotherapy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2024 Nov 18.

- Zhai, LY; Liu, JF; Zhao, JJ; Su, AM; Xi, XG; Hou, XM. Targeting the RNA G-Quadruplex and Protein Interactome for Antiviral Therapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 10161–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgilio, A; Amato, T; Petraccone, L; Esposito, F; Grandi, N; Tramontano, E; et al. Improvement of the activity of the anti-HIV-1 integrase aptamer T30175 by introducing a modified thymidine into the loops. Sci Rep. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, V; Pirone, L; Mayol, L; Pedone, E; Virgilio, A; Galeone, A. Exploring the binding of d(GGGT)4 to the HIV-1 integrase: An approach to investigate G-quadruplex aptamer/target protein interactions. Biochimie 2016, 127, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, KM; Chin, D; Seah, HL; Shi, Q; Lim, KW; Phan, AT. G4-PROTAC: Targeted degradation of a G-quadruplex binding protein. Chemical Communications 2021, 57, 12816–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).