1. Introduction

Hubless full-mesh very small aperture terminal (VSAT) communication systems are increasingly adopted in satellite networks for their resilience against single points of failure, support for direct VSAT-to-VSAT connectivity, and enhanced security through private network isolation [

52]. Unlike traditional star-configured VSAT architectures that rely on a central hub, hubless full-mesh systems eliminate hub dependency and enable direct remote-to-remote communication, which is critical for modern satellite applications such as broadband connectivity, IoT backhaul, and emergency communications. Reliable satellite communication requires robust forward error correction (FEC) to mitigate noisy channel conditions and maintain data integrity. Conventional FEC schemes such as turbo product codes (TPCs) [

64], convolutional codes [

59,

61,

62,

63], and Reed–Solomon (RS) codes [

59,

60,

61] have been widely deployed. However, low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes, and particularly quasi-cyclic LDPC (QC-LDPC) codes, have gained prominence due to their superior error-correction capability and hardware efficiency. QC-LDPC codes exploit structural regularity in the parity-check matrix, reducing memory and interconnect complexity while achieving near-optimal performance [

50]. These advantages have led to their adoption in modern standards such as DVB-S2 [

59], IEEE 802.11n (WiFi) [

55], and 5G NR [

58]. The sum-product (SP) algorithm, also known as belief propagation (BP), remains the performance benchmark for LDPC decoding [

3], but its probability-domain arithmetic is computationally expensive for resource-constrained FPGAs. Simplified variants such as min-sum (MS) [

2,

35] and normalized min-sum (NMS) reduce complexity by replacing multiplications with add-compare-select operations, albeit at the cost of some coding gain. Further refinements, including second-minimum approximation (SAMS) [

7], two-dimensional MS (2D-MS) [

32], and two-dimensional normalized min-sum (2D-NMS) [

30], improve accuracy with modest overhead. Traditional register-transfer-level (RTL)-based implementations of LDPC decoders are time-consuming, error-prone, and difficult to scale across evolving FPGA platforms. High-Level Synthesis (HLS) offers a modern design methodology that accelerates development, improves portability, and enables rapid design-space exploration without sacrificing hardware efficiency. For FPGA targets such as VSATPlus

®, decoder microarchitecture strongly impacts throughput, latency, and power. Fully parallel layered designs achieve high per-iteration throughput but incur dense interconnect and tight timing closure [

36]. Partially parallel designs reduce wiring and power at the cost of lower throughput [

37], while pipelined block-serial decoders minimize area but increase latency [

38]. Scheduling also influences convergence and memory organization: flooding requires more iterations and higher energy, whereas layered scheduling reduces iterations but demands careful memory banking [

10,

11]. Despite these advances, existing FPGA implementations struggle to balance error-correction performance, resource utilization, and power efficiency under stringent constraints typical of satellite systems. This gap motivates the need for an approach that combines algorithmic improvements with a scalable, hardware-aware design methodology leveraging HLS. To address this challenge, this work proposes a layered 2D-Corrected Normalized Min-Sum (2D-CNMS) decoder integrated into an HLS-based design flow for generating reusable LDPC IP cores. The proposed architecture incorporates dyadic, multiplier-free normalization and dual-scaling of the first and second minima, achieving near-BP performance while minimizing resource usage and power consumption.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows: (1) A hardware-aware LDPC decoder architecture based on the 2D-CNMS algorithm optimized for FPGA implementation; (2) An HLS-based design flow for generating reusable LDPC IP cores, reducing development complexity compared to traditional RTL approaches; (3) Comprehensive evaluation of post-implementation error-correction performance, resource utilization, and throughput under realistic satellite channel conditions. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the VSATPlus

® system and its architectural constraints.

Section 3 and

Section 4 present the proposed LDPC decoder and algorithmic enhancements.

Section 5 details the FPGA-oriented architecture.

Section 7 reports simulation results and analyzes complexity-performance trade-offs. Finally,

Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

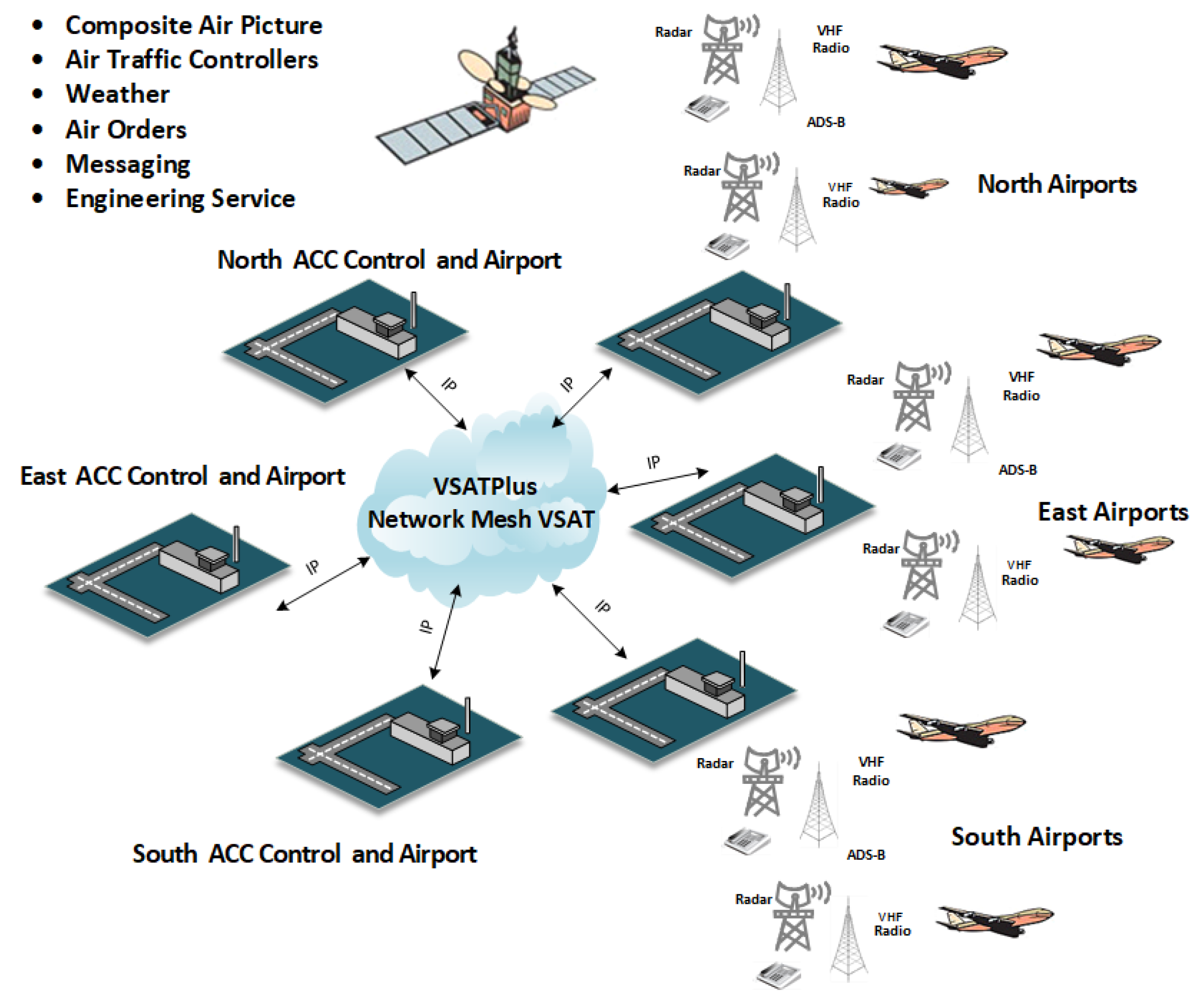

2. VSATPlus System Overview

The VSATPlus [

66] system provides full-mesh, single-hop connectivity within a satellite network, leveraging multi-frequency time division multiple access (MF-TDMA) technology. Each terminal buffers user data and transmits it in short, high-speed bursts scheduled to avoid overlap, ensuring efficient satellite resource utilization without requiring a central hub for scheduling. This hubless architecture supports diverse satellite applications, including broadband connectivity, IoT backhaul, emergency communications, and enterprise networking, where reliability and scalability are critical.

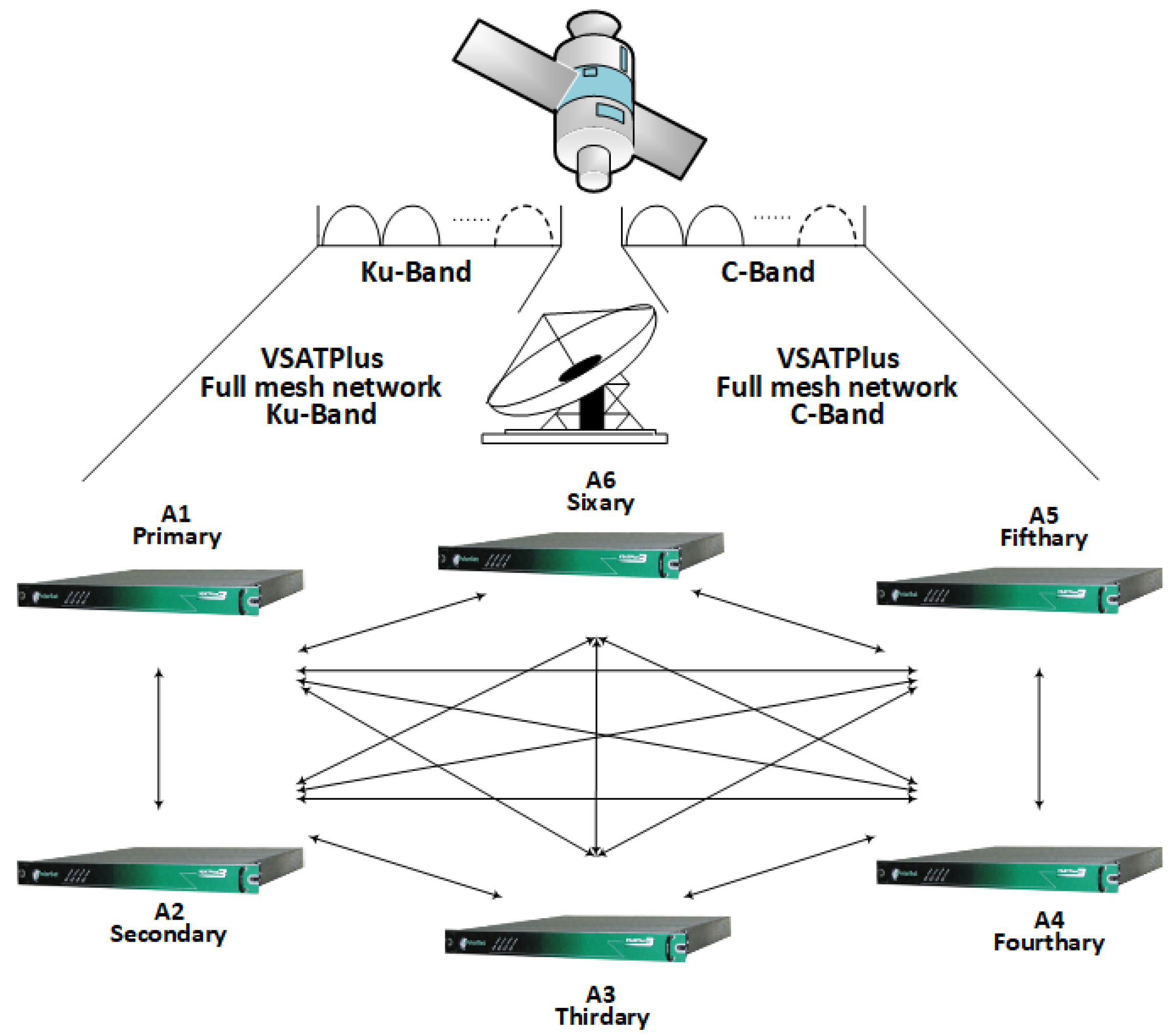

Figure 1 illustrates one example of VSATPlus deployment in air traffic control (ATC), showing direct IP connectivity between area control centers (ACCs) and airports across regions. Similar principles apply to other mission-critical satellite services requiring secure, low-latency communication.

The VSATPlus modem is highly agile, capable of varying multiple parameters burst-by-burst. This flexibility enables carrier-to-carrier hopping for both transmit and receive over 32 carriers, along with adaptive modulation and FEC changes. This capability, referred to as Mesh-ACM

TM, dynamically adjusts modulation and coding to accommodate different terminal antenna sizes and varying channel conditions across the network, optimizing throughput and reliability [

53].

Figure 2 shows the architecture of a VSATPlus full-mesh, hubless network employing Ku-band and C-band satellite links for high-throughput communication. The satellite facilitates signal transmission from ground stations operating on both frequency bands, enabling simultaneous multi-band connectivity.

The network consists of six nodes ( to ), interconnected in a full-mesh topology to ensure direct, bidirectional communication between all nodes. This architecture demonstrates the robustness and scalability of VSATPlus for distributed satellite applications beyond ATC, including broadband and enterprise networking.

3. Decoding Algorithmic Principles

QC-LDPC codes apply parity-check matrices tiled by

submatrices that are either circulant permutations of the identity or zeros [

29]. This regular structure yields compact representations and lower memory requirements while enabling highly parallel, hardware-efficient decoders—an attractive performance/complexity trade-off for high-throughput satellite links. In satellite communication systems, where long propagation delays and limited link budgets make re-transmissions costly, efficient LDPC decoding is essential to maintain reliability and throughput. Although QC-LDPC codes may be degree-irregular (row and column weights

can vary), the locations of ones in

H are deterministically specified by the permutation matrix and its circulant shifts, producing predictable, conflict-free access patterns rather than random placement [

17]. Furthermore, the QC form organizes

H as a regular array of blocks, with

Z distinct memory banks for variable node (VN) data, enabling blockwise schedules that achieve scalable parallelism. A compressed permutation matrix, illustrated in

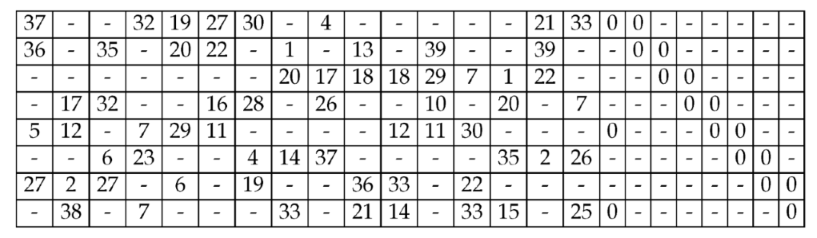

Table 1, stores only shift offsets, where dash marks a zero block and non-negative entries specify the cyclic shift of the identity, minimizing footprint and simplifying decoder configuration. Owing to these advantages, QC-LDPC codes are widely adopted in modern communication standards.

The decoding of QC-LDPC codes typically employs BP algorithms, which are broadly classified based on the nature of the message information exchanged during iterations. Hard-decision decoders, such as the bit-flipping (BF) algorithm, operate on binary decisions extracted directly from the channel [

39]. Conversely, soft-decision decoding techniques, including the sum-product (SP) algorithm and its computationally simplified variant, the min-sum (MS) algorithm, leverage soft information in the form of log-likelihood ratios (LLRs) [

26,

68]. These iterative message-passing algorithms exchange extrinsic information between variable nodes (VNs) and check nodes (CNs) over a bipartite graph representation of the parity-check matrix

H, known as a Tanner graph [

27]. This graph-based framework underpins the inference mechanism that progressively refines the reliability of decoded bits with each iteration.

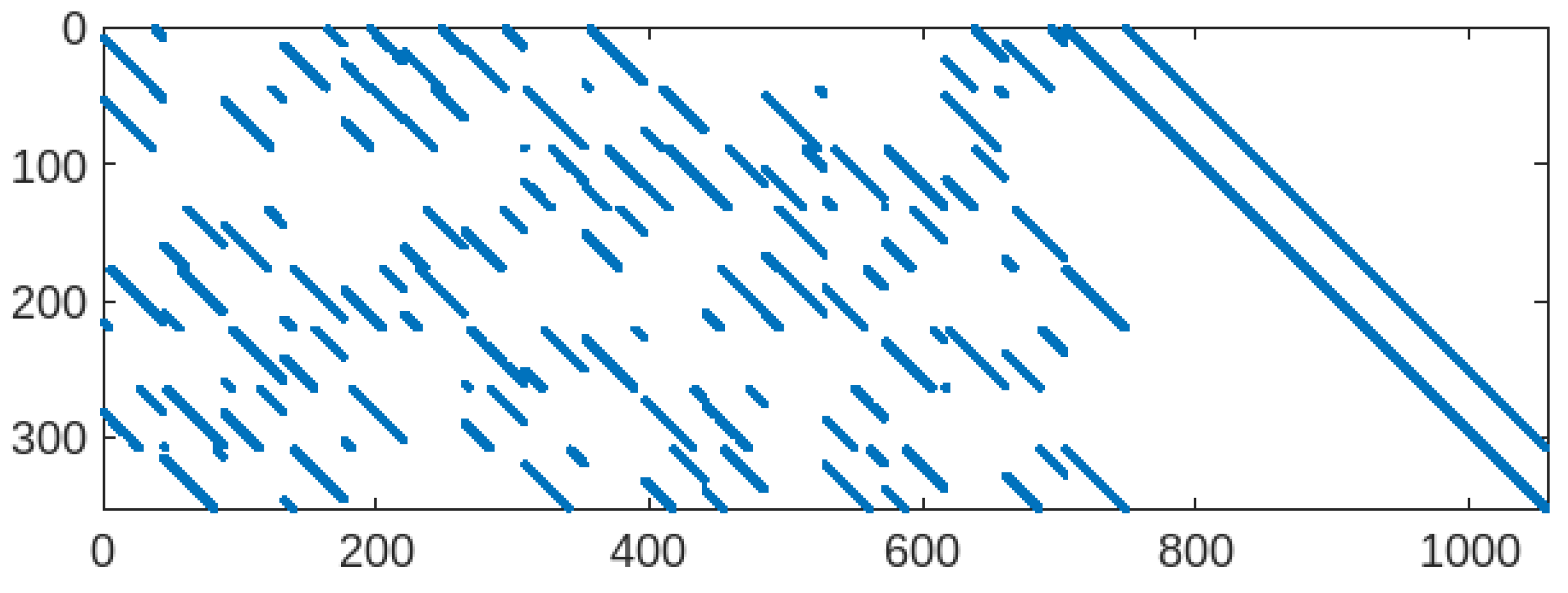

The structure of the LDPC parity-check matrix

H used in this work is derived from the IEEE 802.16e (WiMAX) standard. The matrix is constructed from a permutation matrix, shown in

Table 1, composed of integer shift values and null entries, expanded by a lifting factor

Z. The resulting

H matrix is sparse and quasi-cyclic as illustrated in

Figure 3. Each diagonal or off-diagonal band in the figure corresponds to a circulant permutation matrix. Their distribution reflects the structured connectivity of VNs (columns) and CNs (rows).

3.1. Sum-Product / Belief Propagation

The SP decoding algorithm, also known as the BP [

30], initiates by calculating the LLRs for each received channel symbol

at time

i under an AWGN channel model, as follows:

where

is the channel noise power following the Gaussian distribution. Initially, messages passed from variable node

v to the connected check node

c are set to the LLR value derived from the received symbol, as given by:

where

represents the set of check nodes connected to the variable node

v, excluding

c. Next, the check node information is updated as follows:

Once the convergence condition is satisfied or the maximum number of iterations is reached, the operation terminates. Subsequently, the hard decision for each variable node,

v, is computed based on its LLR:

If

, then the estimated transmitted bit value is 0, otherwise it is considered as 1.

3.2. Min-Sum

While BP achieves excellent error-correction performance, its reliance on nonlinear functions and probability-domain operations results in high computational complexity, motivating the development of simplified algorithms such as Min-Sum. The MS decoding algorithm simplifies the computational complexity of the BP algorithm by replacing nonlinear hyperbolic tangent functions with a minimum operation. Thus, the check node update equation simplifies to:

The variable nodes update and hard decision processes remain consistent with the BP algorithm.

3.3. Normalized Min-Sum

Although the MS significantly reduces hardware resource requirements and processing latency compared to the BP algorithm, it experiences degradation in BER performance, typically around

dB [

39]. This degradation primarily results from overestimation in extrinsic information exchange between nodes. To mitigate this effect, normalized min-sum (NMS) applies scaling factor,

, to correct extrinsic information estimates, thereby enhancing practical decoding performance [

24]:

Whereas NMS attenuates the check-node minima by multiplying the raw minimum magnitude by a constant

, offset min-sum (OMS) instead applies a fixed subtraction to correct for the systematic over-estimation introduced by the plain min-sum rule [

25]. In OMS, each check-to-variable message is computed as:

where

is the offset parameter chosen to minimize the performance loss relative to the full belief-propagation algorithm [

25]. Because the offset operation requires only a single subtraction per edge rather than a multiplication, OMS offers reduced critical-path latency and lower hardware resource usage compared to NMS.

3.4. 2-Dimensional Normalized Min-Sum

In the standard NMS algorithm, a single constant scaling factor compensates the overestimated magnitudes of all incoming check-to-variable messages. However, the extrinsic magnitude sent to a VN equals the smallest incoming magnitude,

, for all edges except the argmin edge, which uses the second-smallest incoming magnitude,

, due to edge exclusion. Consequently, applying one scale for both cases can miscalibrate some messages and degrade performance. The 2D-NMS addresses this by applying distinct scaling (

), conditioned on whether

or

is used, yielding more accurate LLRs with only modest added complexity [

31]:

For LDPC decoders employing the 2D-NMS algorithm, the optimal normalization factors (

), are predominantly determined by the check node degree (

), which is determined by the parity check matrix.

3.5. 2-Dimensional Min-Sum

While 2D-NMS compensates the check-node magnitude bias via the scaling pair (

), it applies the same gain to both message flows. Density-evolution analysis in [

32] shows that the residual bias on the variable-to-check stream differs statistically from that on the check-to-variable stream. Therefore, introducing a second, direction-specific scaling pair eliminates this asymmetry and closes the remaining gap to SP decoding with only two extra multiplications per edge. To address this residual asymmetry more effectively, [

32] proposes applying iteration-dependent scale factors (

) directly to the extrinsic LLRs on each edge, resulting in:

While the corresponding check-to-variable updates is as follows:

Although (

) can be optimized adaptively based on the code structure and channel SNR, [

32] demonstrates that exhaustive AWGN profiling across the operational

range yields two fixed scale factors that preserve virtually all of the SP decoder’s extrinsic-information fidelity.

4. 2-Dimensional Corrected Normalized Min-Sum

For VSATPlus terminals, even modest coding-gain improvements translate into reduced power-amplifier back-off and increased fade margins. However, the SP decoding algorithm remains computationally impractical for the throughput and power envelopes of the target FPGA platforms. Building on [

31,

32], we propose a two-dimensional corrected normalized min–sum (2D-CNMS) decoder that preserves the add–compare–select arithmetic of MS while recovering a substantial fraction of the residual gap to SP algorithm. The update introduces two shift-based per-edge scalings per iteration and incurs no additional on-chip memory, thereby maintaining low architectural complexity. Therefore, the scaled variable-to-check update is defined as:

While, the scaled check-to-variable update is given by:

Similar to 2D-NMS algorithm,

and

denote the smallest and second-smallest absolute values of the incoming messages

, where

.

5. 2D-CNMS Hardware Implementation

Hand-optimized RTL design has traditionally been the standard approach for FPGA-based LDPC decoders. However, High-Level Synthesis (HLS) methodologies [

16] and commercial toolchains such as Vivado HLS [

67] now offer a more productive alternative by enabling designers to specify the decoder in C/C++ or SystemC and automatically generate synthesizable RTL. In practice, HLS significantly reduces design and verification effort [

15], while achieving area, timing, and power results comparable to expert-tuned HDL implementations [

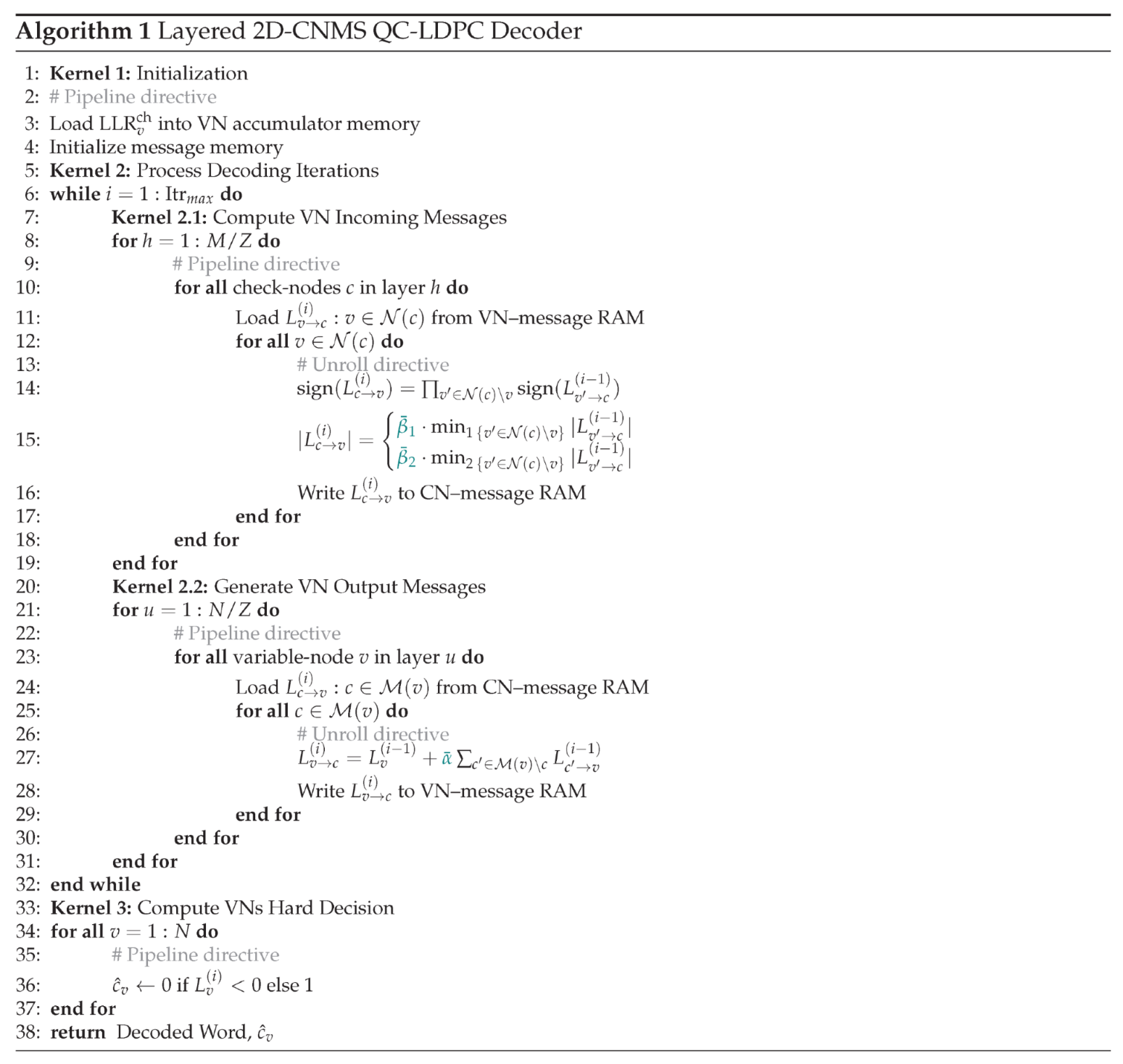

15]. Furthermore, a single high-level source is portable across FPGA families and integrates seamlessly with the VSATPlus C-based simulation environment, facilitating rapid design-space exploration and system-level validation. Algorithm 1 summarizes the layered scheduling strategy employed in the proposed 2D-CNMS decoder. Compared to conventional layered MS, the proposed approach introduces a uniform variable-to-check scaling factor,

, and a two-level check-to-variable scaling pair (

), conditioned on whether the outgoing message is derived from

or

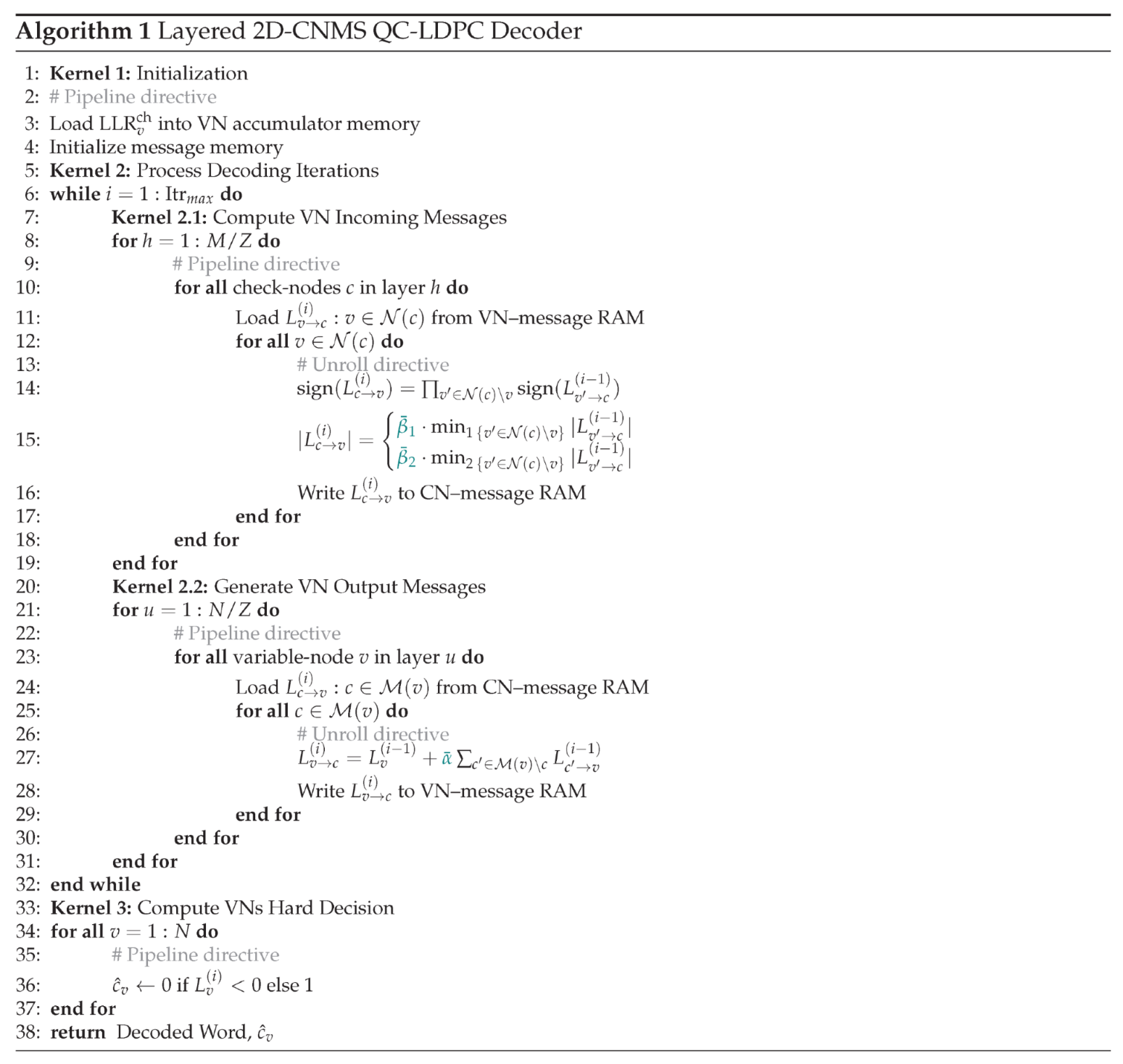

. These refinements improve extrinsic information accuracy while preserving the low-complexity arithmetic of MS.

The proposed decoder is implemented using Vivado HLS 2024, leveraging loop-level parallelism and pipelining to maximize throughput. Inner loops responsible for CN and VN updates are partially or fully unrolled to generate multiple CN→VN and VN→CN messages per cycle, while outer loops are pipelined to minimize the initiation interval (II), enabling iteration overlap and reducing latency. The inherent layered structure of QC-LDPC codes facilitates deterministic memory banking and partitioning across Z dual-port block RAMs (BRAMs), supporting concurrent read–modify–write operations aligned with layer boundaries. Address generation is performed using two ROM-based lookup tables (LUTs) precomputed from the base matrix: for CN updates and for VN updates. These index tables enable constant-time routing without additional buffering or pointer chasing, ensuring efficient memory access.

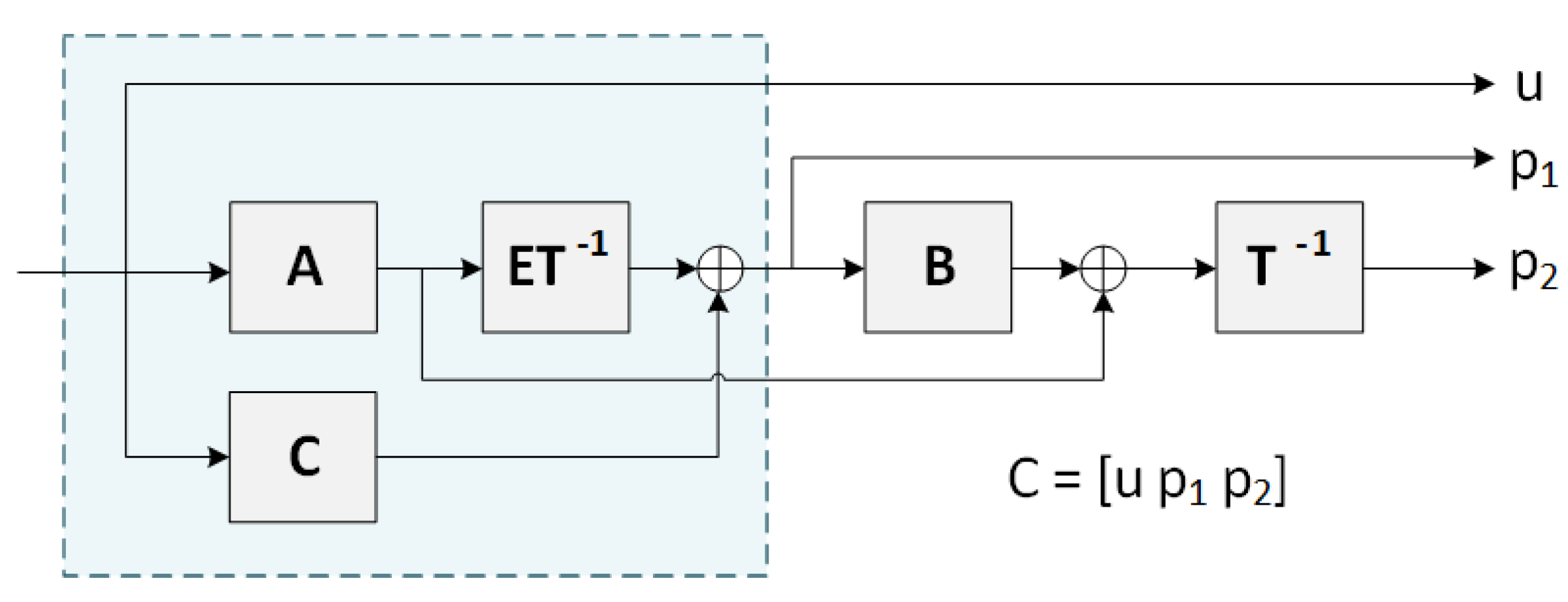

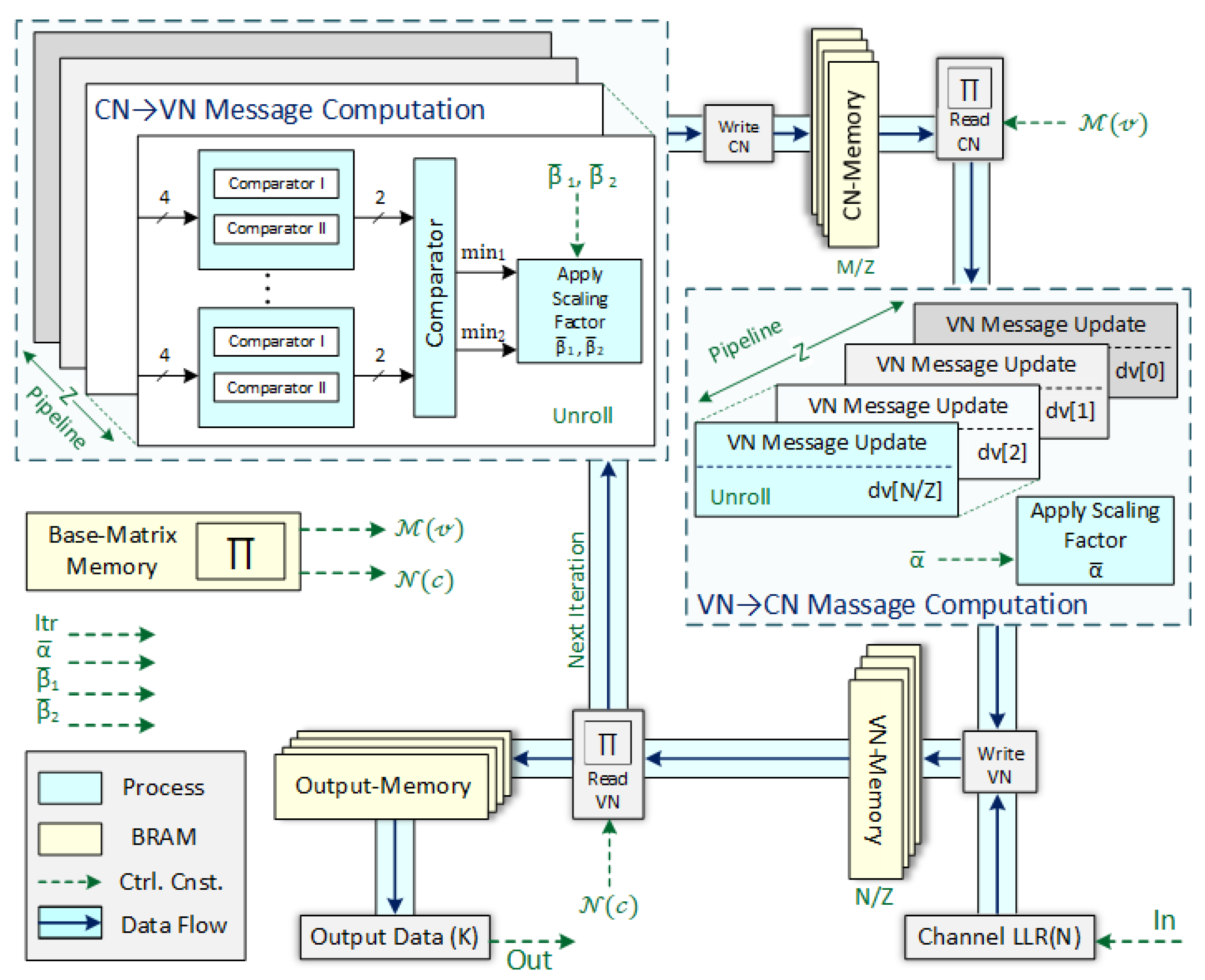

The HLS-based 2D-CNMS decoder architecture, illustrated in

Figure 4, comprises two fully parallel processing engines: one dedicated to CN message computation and the other to VN message computation. Each engine interfaces directly with dual-port BRAM banks under the control of a compact ROM storing non-negative cyclic-shift offsets and connection degrees derived from the base matrix.

In the CN engine, which comprises parallel pipelines, each pipeline retrieves a Z-wide vector of extrinsic LLRs from the VN RAM, applies a fixed-depth tree of four-input comparators to identify the smallest and second-smallest magnitudes, determines the overall output sign through a single XOR reduction stage, and adjusts these minima using normalization factors (). The normalized extrinsic messages are then written back to the CN-RAM via the dual-port interface. Similarly, the VN engine, consisting of parallel pipelines, reads the updated CN messages along with the original channel LLRs, accumulates them using an adder tree, subtracts each corresponding extrinsic to form new messages, scales the result by , applies eight-bit saturation, and generates provisional hard decisions based on the sign. Both the updated soft-value vectors and hard-decision bits are subsequently written to the VN RAM and output RAM, respectively.

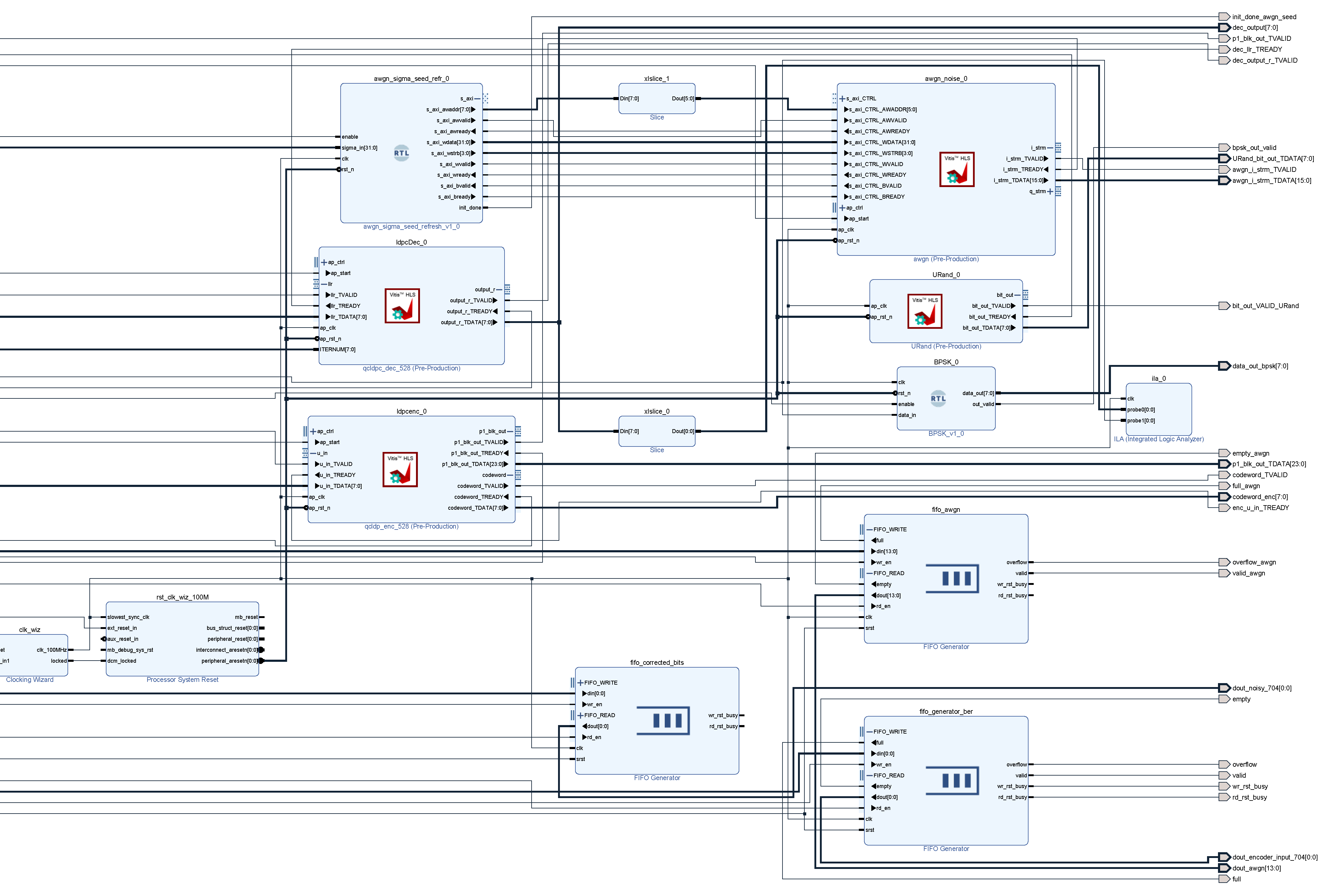

6. End-to-End Vivado Block Design

Figure 5 illustrates the integrated encoder–channel–decoder chain instantiated in Vivado by introducing external IP cores implemented using Vitis HLS 2024. Although the LDPC IP core was validated at a clock frequency of 400 MHz, the design employs a 100 MHz system clock generated by the Clocking Wizard IP and distributed via the Processor System Reset module. Each frame begins with a single-cycle start pulse, and all AXI4-Stream interfaces operate without backpressure, with the

ready signal held asserted.

A pseudorandom source generates independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) Bernoulli bits using a linear feedback shift register (LFSR) method. After AXI4-Stream handshakes, the QC-LDPC encoder accepts the payload and emits a serialized codeword. An RTL binary phase-shift keying (BPSK) modulator maps bits to signed 8-bit symbols with values

. Additive noise is produced by an external AWGN IP implementing the Box–Muller transform (see

Appendix B). Variance and seed registers are programmed via AXI4-Lite memory-mapped writes issued by the Zynq UltraScale+ processing system (PS), enabling deterministic initialization and run-time reconfiguration of the programmable logic (PL) core. The noise stream is buffered in a FIFO to decouple producer and consumer timing. On readout, the noise is added to the BPSK waveform, saturated to

, and treated as the input LLR stream for the decoder. Similar to AWGN parameters, the iteration limit,

, is also configured by a control register for each frame.

During transmission, the reference bit for each payload position is stored in a reference FIFO. In parallel, a channel hard decision is derived from the sign of the saturated received sample and stored in a second FIFO to measure uncoded performance. When decoded bits become available, they are compared against the reference FIFO to accumulate the post-decoder error count, while the channel-hard stream is compared against the same reference to count bit flips caused by noise.

7. Emulation Results

We evaluate decoding algorithms under a layered schedule on the QC-LDPC code with using 8-bit fixed-point LLRs (clip/saturate) and syndrome-based early termination. The channel is AWGN and is swept on a uniform grid with sufficient frames per point to probe down to . All baselines use identical quantization, stopping criteria, and layered scheduling for a fair comparison. Unlike conventional NMS, the proposed 2D-CNMS introduces dual-direction scaling and normalization refinements that significantly improve convergence speed and error-floor performance while maintaining FPGA-friendly complexity.

According to [

31], the optimal two-level CN normalization factors

decrease with increasing check-node degree (

) and approach constants at high SNR. Specifically, for the regular codes with

and

dB,

and

, trending toward the upper end as SNR rises. Consistently, [

32] reports nearly iteration-invariant scalings for IEEE 802.11n

,

as

and

, achieving BER within

dB of SP algorithm over

dB. In line with [

1], the strongest single-scalar NMS baseline uses a fixed normalization schedule:

where

ℓ represents the number of iterations.

These observations support fixed, iteration-invariant gains. Guided by coarse-to-fine emulation sweeps on the target IEEE 802.16e QC-LDPC codes (rates ), we therefore map to and , and set the VN gain to . All scalings are implemented via shift-and-subtract to eliminate multipliers and extra memory.

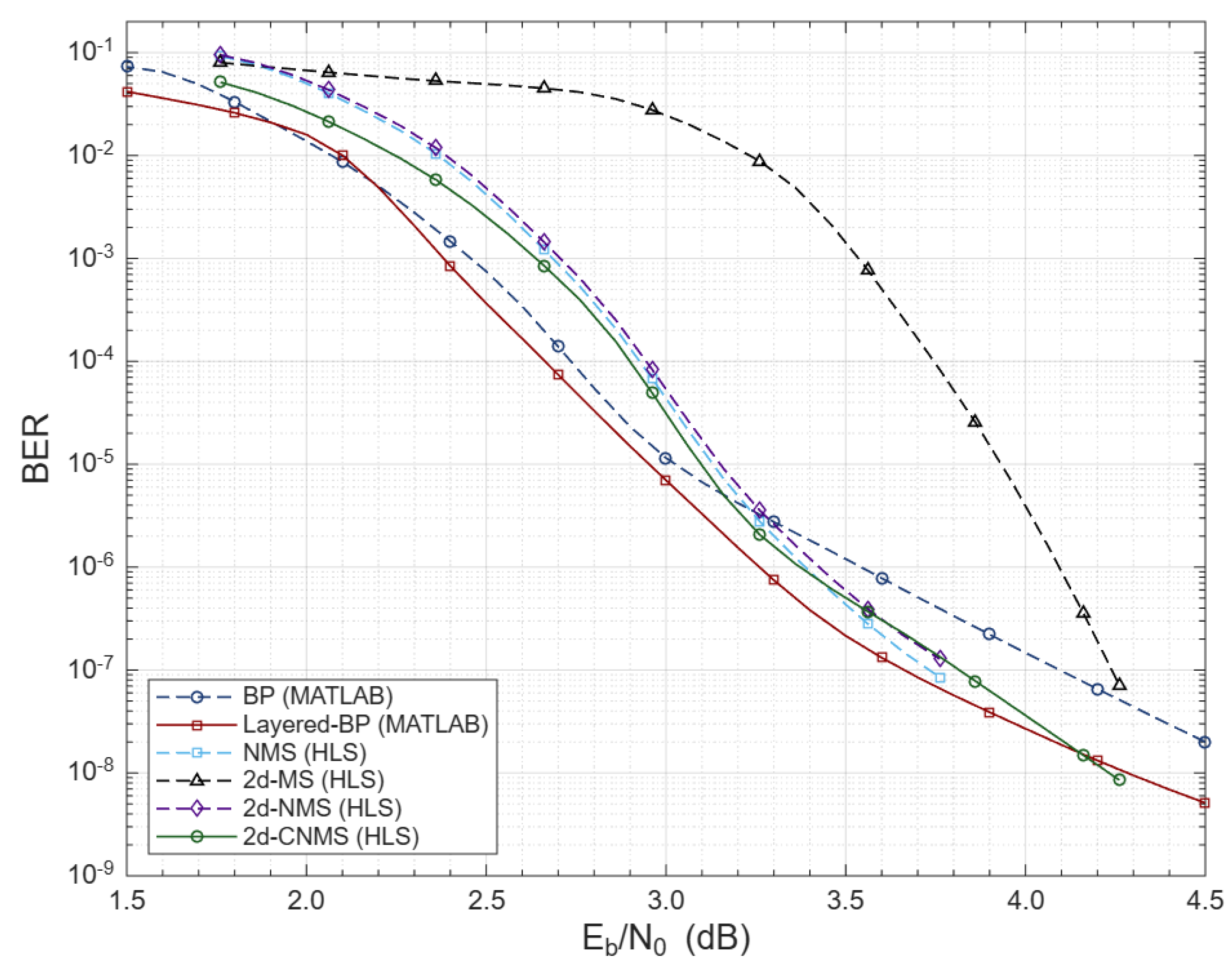

7.1. Performance and Complexity Comparison

Figure 6 compares full-BP, layered-BP, NMS (

) [

1,

24], 2D-MS (

) [

39], 2D-NMS (

)

(

) [

31], and the proposed 2D-CNMS (

)

(

) on QC-LDPC code (

) with

. Across the operational

range, 2D-CNMS closely follows layered-BP and consistently outperforms NMS, 2D-NMS, and 2D-MS. While NMS and 2D-CNMS are comparable in the waterfall region, 2D-CNMS exhibits a lower error floor in the high-SNR, outperforming even the layered-BP reference. While BP remains the theoretical benchmark, its computational complexity makes FPGA implementation impractical. 2D-CNMS achieves near-BP performance without multipliers or dividers, making it suitable for real-time FPGA deployment.

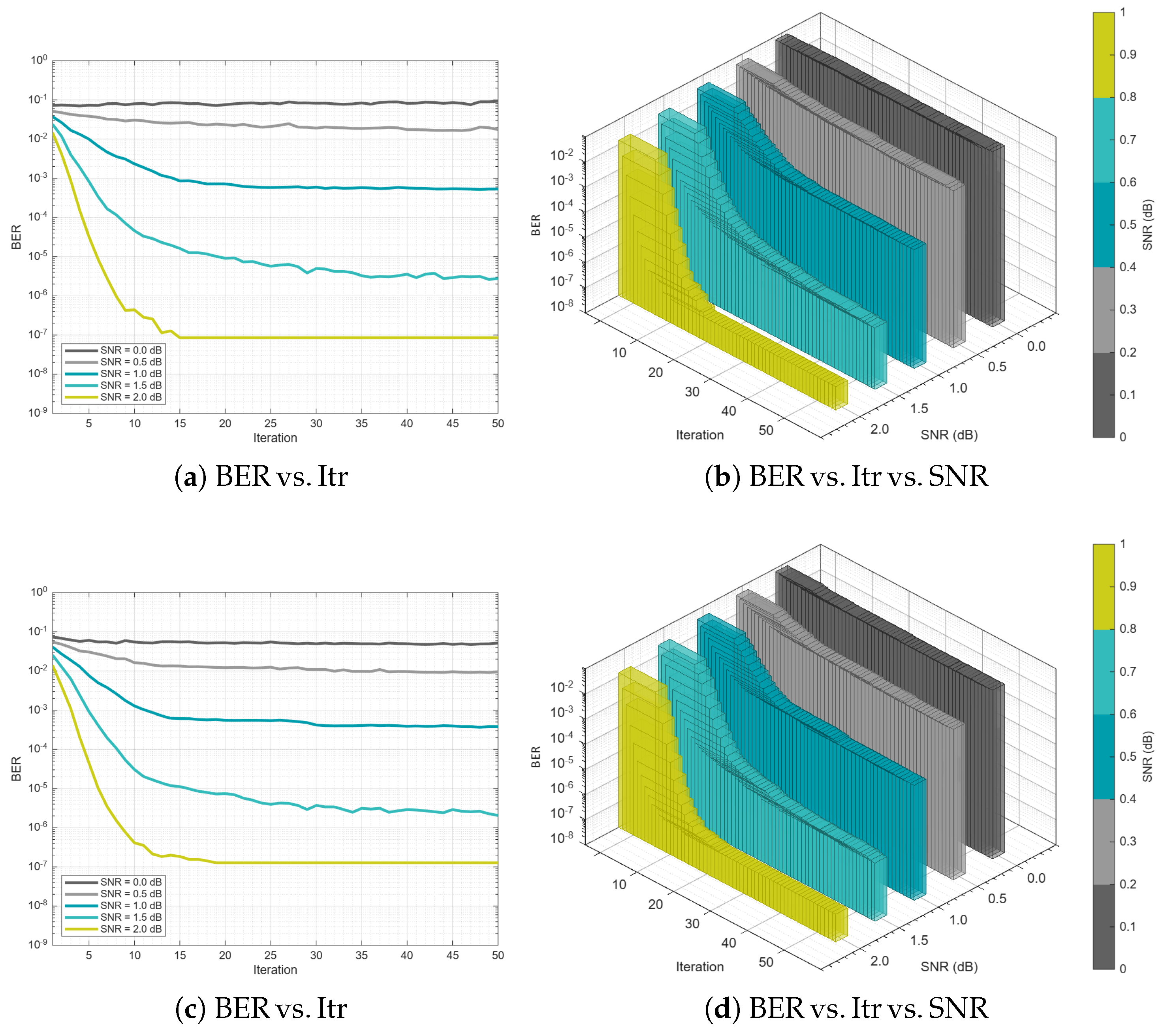

Figure 7 reports BER versus decoder iterations for the

code under BPSK/AWGN. At SNR

dB, the proposed 2D-CNMS achieves BER

by approximately 12 iterations, whereas the conventional NMS (with

) requires roughly 15 iterations. For SNR

dB, neither method reaches

within 50 iterations. Nevertheless, 2D-CNMS maintains a uniformly lower BER for the same iteration budget and, at SNR

dB, attains BER

in the mid–30s iterations while NMS does not achieve

within 50 iterations. These iteration savings translate directly to reduced latency and higher throughput (see

Section 7.3).

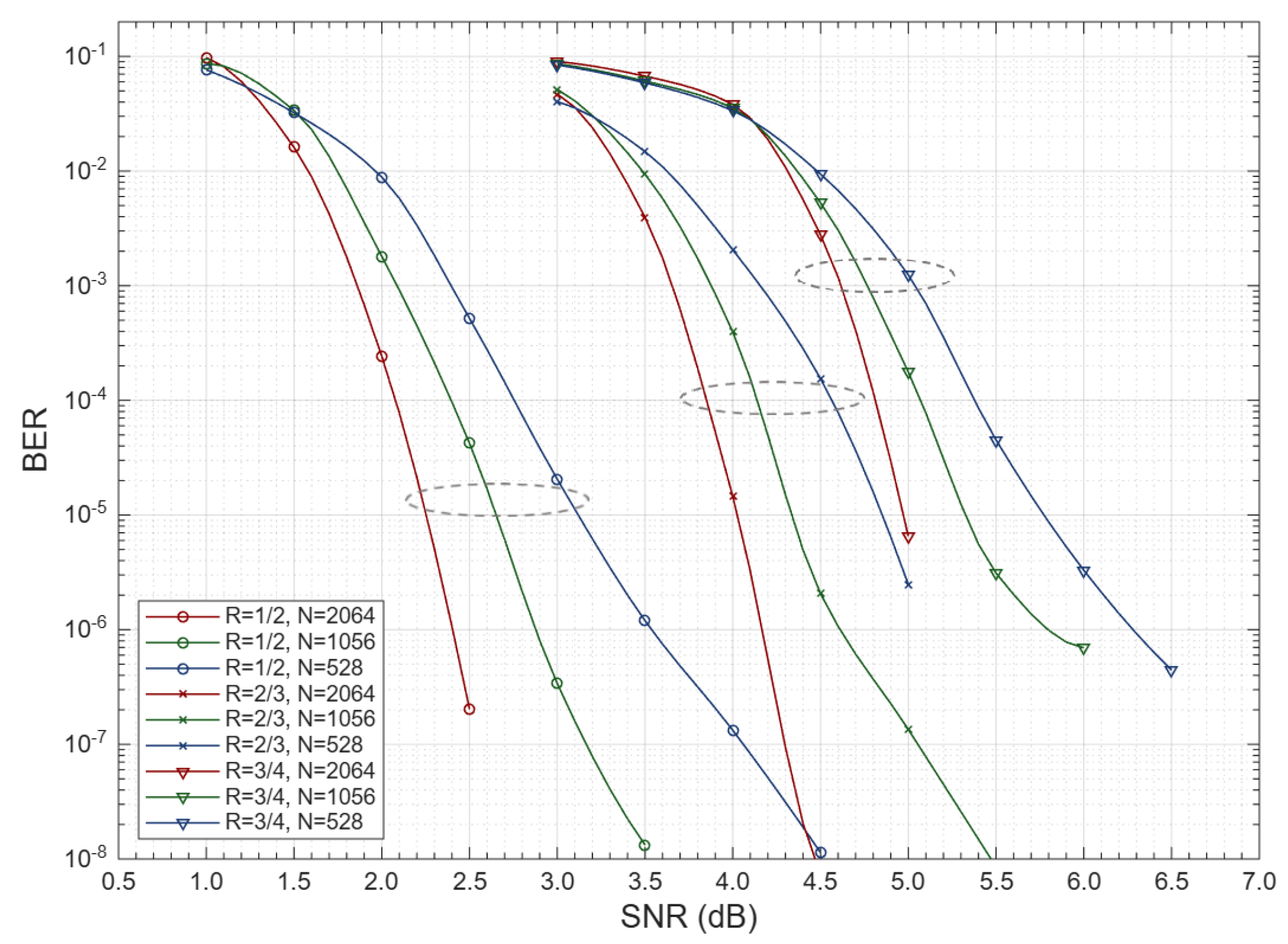

Figure 8 presents the

performance of the proposed 2D-CNMS across

QC-LDPC code profiles. In contrast to the

layered-BP reference in

Figure 6, the 2D-CNMS maintain a sustained waterfall region with no observable error floor over the simulated range, reaching

.

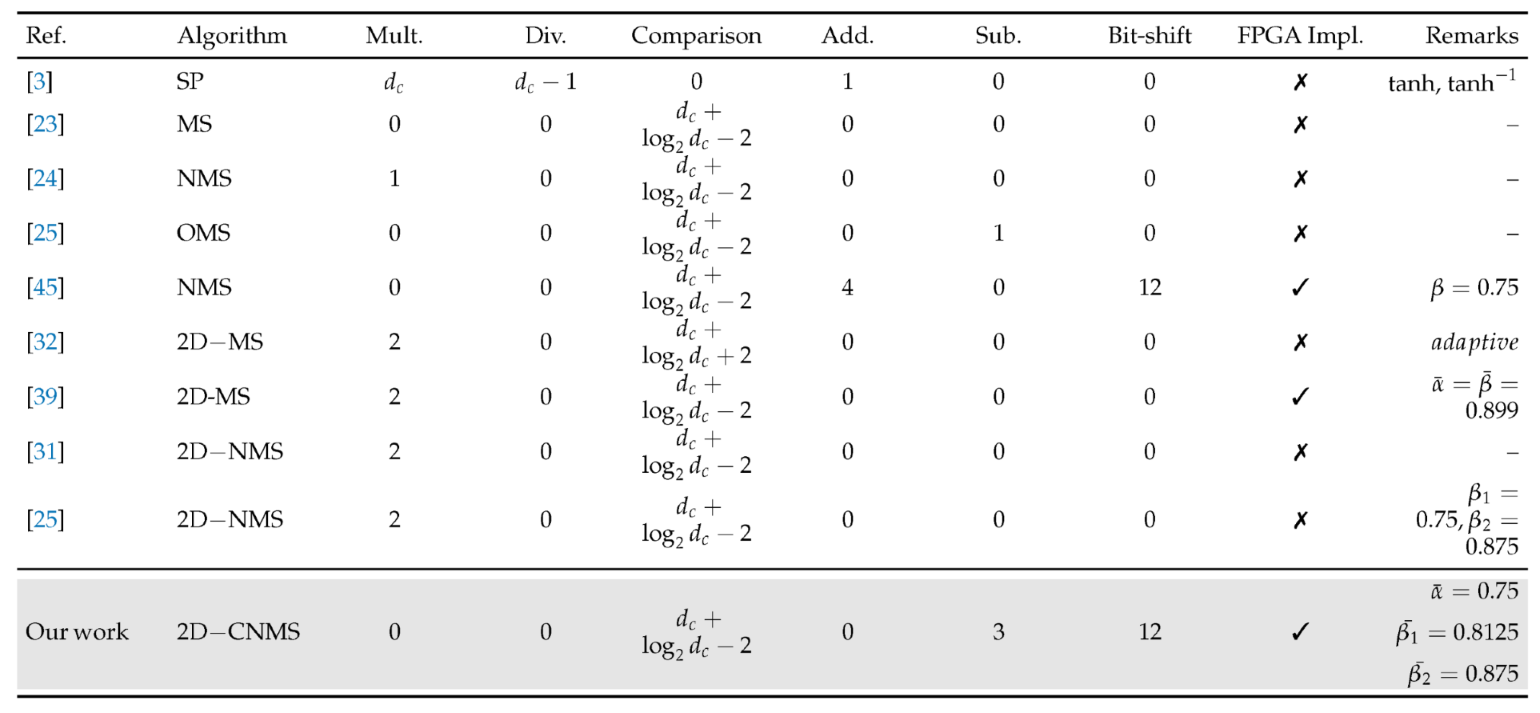

Table 2 contrasts the arithmetic requirements of SP, MS, NMS, OMS, 2D-MS, 2D-NMS, and the proposed 2D-CNMS on a per-check-node basis. SP demands

multiplications and

divisions. 2D-MS retains 2 multipliers. 2D-CNMS removes multipliers and dividers and keeps the comparator count

. Normalization is implemented by 3 subtractions and 12 bit-shifts. The resulting data path is DSP-free and FPGA-native while recovering near-SP message fidelity. In effect, 2D-CNMS trades multiplications/divisions for lightweight comparisons and shifts.

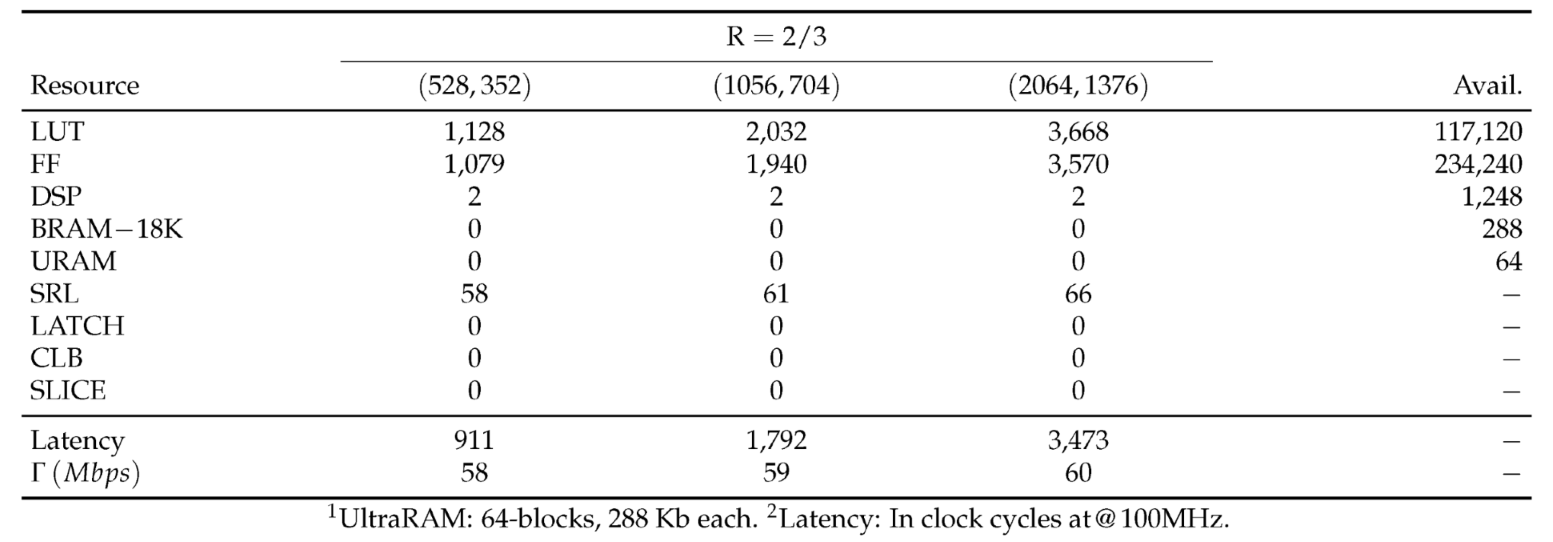

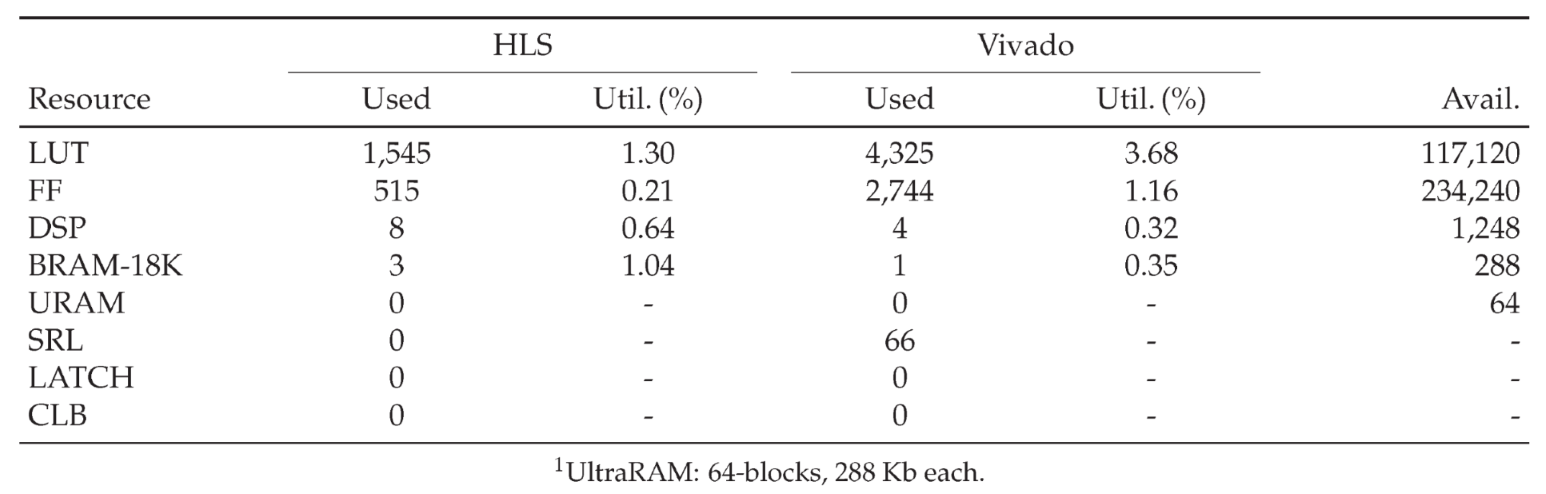

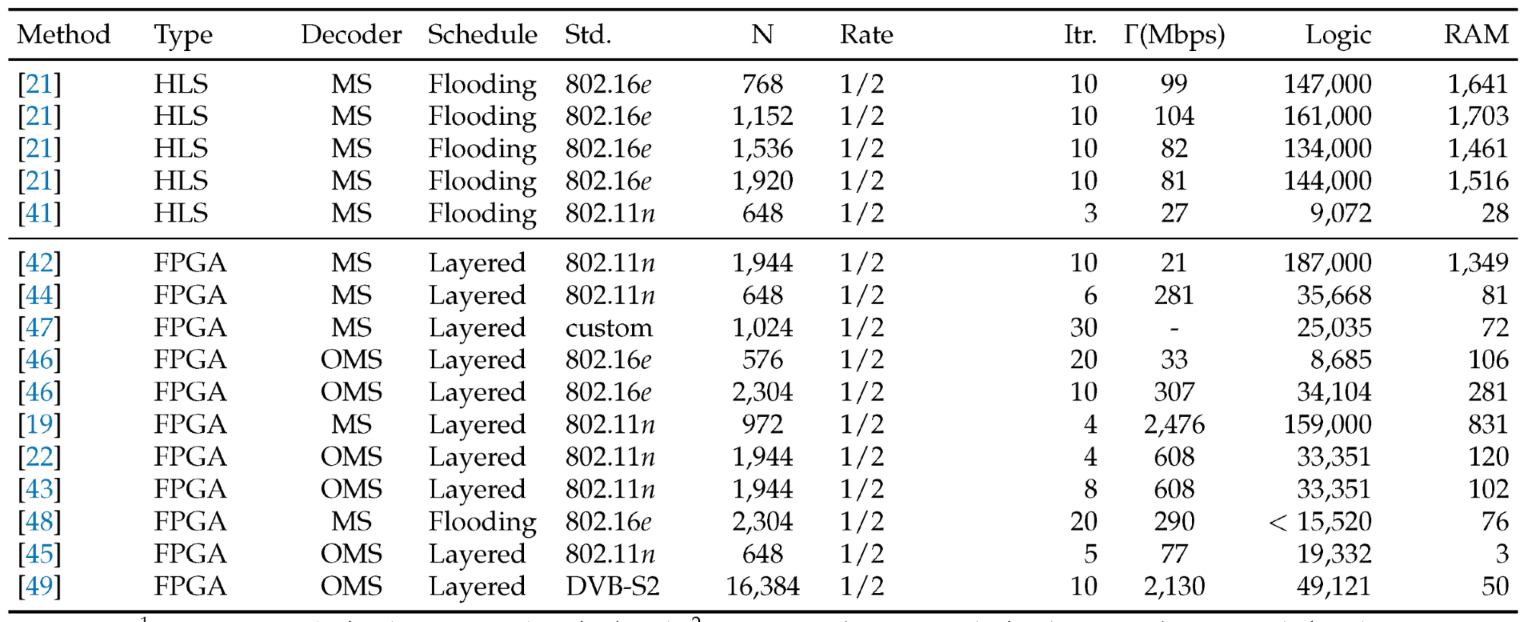

7.2. Resource Utilization

Table 3 benchmarks layered 2D-CNMS against representative HLS and hand-tuned FPGA decoders for WiMAX, Wi-Fi, and DVB-S2 standards under a uniform 100 MHz target and a fixed optimized iteration. The proposed instances deliver 29-41 Mbps coded-bit throughput with 0 DSP usage and moderate memory footprints near 97-217 BRAM-18K.

Considering (

15), throughput scales approximately linearly with the clock for fixed initiation interval and bandwidth, selecting a higher target clock in Vitis HLS (which packages the blocks as Vivado IP) proportionally increases system throughput. Retargeting the same design to

MHz with

yields a

speedup. A comparator–adder–shift data path plus a layered schedule provides a predictable cost–throughput operating point without multiplier-based scaling. The IEEE 802.16e permutation-matrix geometries are

for rate

,

for rate

, and

for rate

. These geometries directly set storage depth and intra-layer parallelism for each instance.

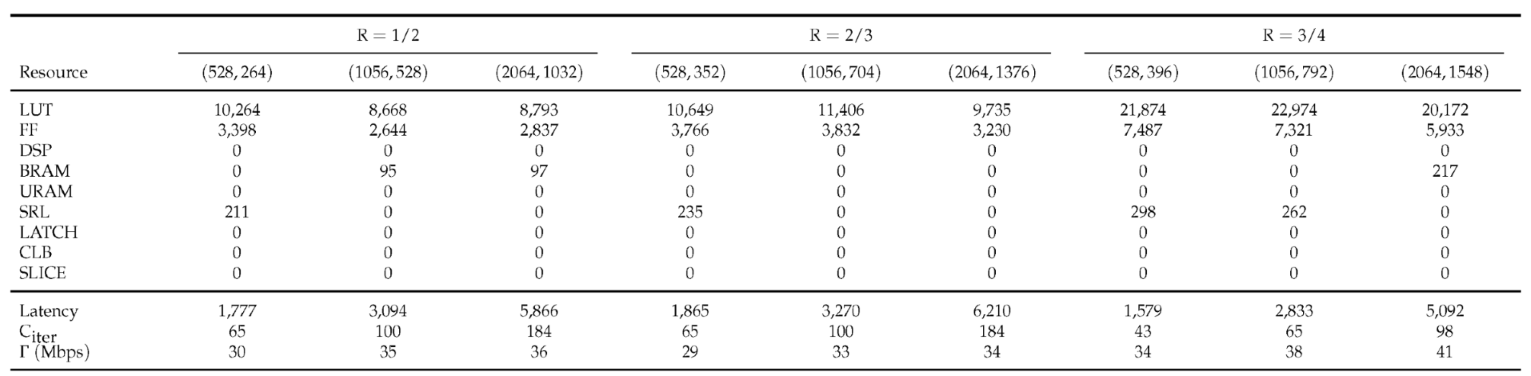

Table 4 summarizes post-synthesis utilization and timing across multiple N, K settings and code rates. All designs remain DSP-free. LUT and FF counts stay modest in the ranges

k-

k and

k-

k. BRAM demand scales with the permutation geometry up to 217 at rate

. Measured decoding latency follows the analytic model

in (

14), with per-iteration costs

that match the scheduled kernels. Achieved coded-bit throughput at 100 MHz spans 29-41 Mbps. These results confirm that the HLS formulation compiles to efficient RTL with stable timing and predictable scaling, while preserving the algorithmic benefits of two-dimensional dyadic normalization.

7.3. Decoding Latency Analysis

Decoding latency is measured in clock cycles to process one full codeword. Under non-overlapped AXI4-Stream I/O the total latency equals sequential input of all channel LLRs, sequential output of the final hard decisions, a fixed I/O and pipeline overhead, and an iteration-dependent compute term. For code rate

defined by an

permutation matrix, see

Table 1, the lifting size is

and the information length is

. Calibrated to the HLS schedule the per-iteration compute cost scales approximately linearly with

Z. For a run with

decoding iterations the latency in cycles is:

with

the fixed pipeline and I/O overhead and

the scheduled check-node and variable-node kernel cost per iteration. From HLS reports, as addressed in

Table 4, at rate

we conservatively upper-bound

cycles,

cycles for QC-LDPC (

), and

cycles for (

).

Given a clock frequency

in

the coded-bit throughput in

is:

while the information-bit throughput equals

.

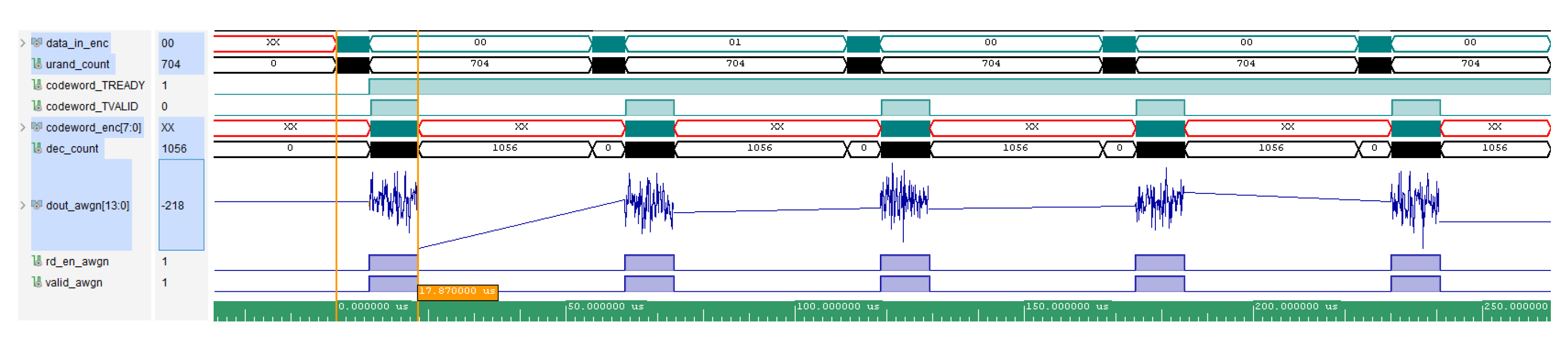

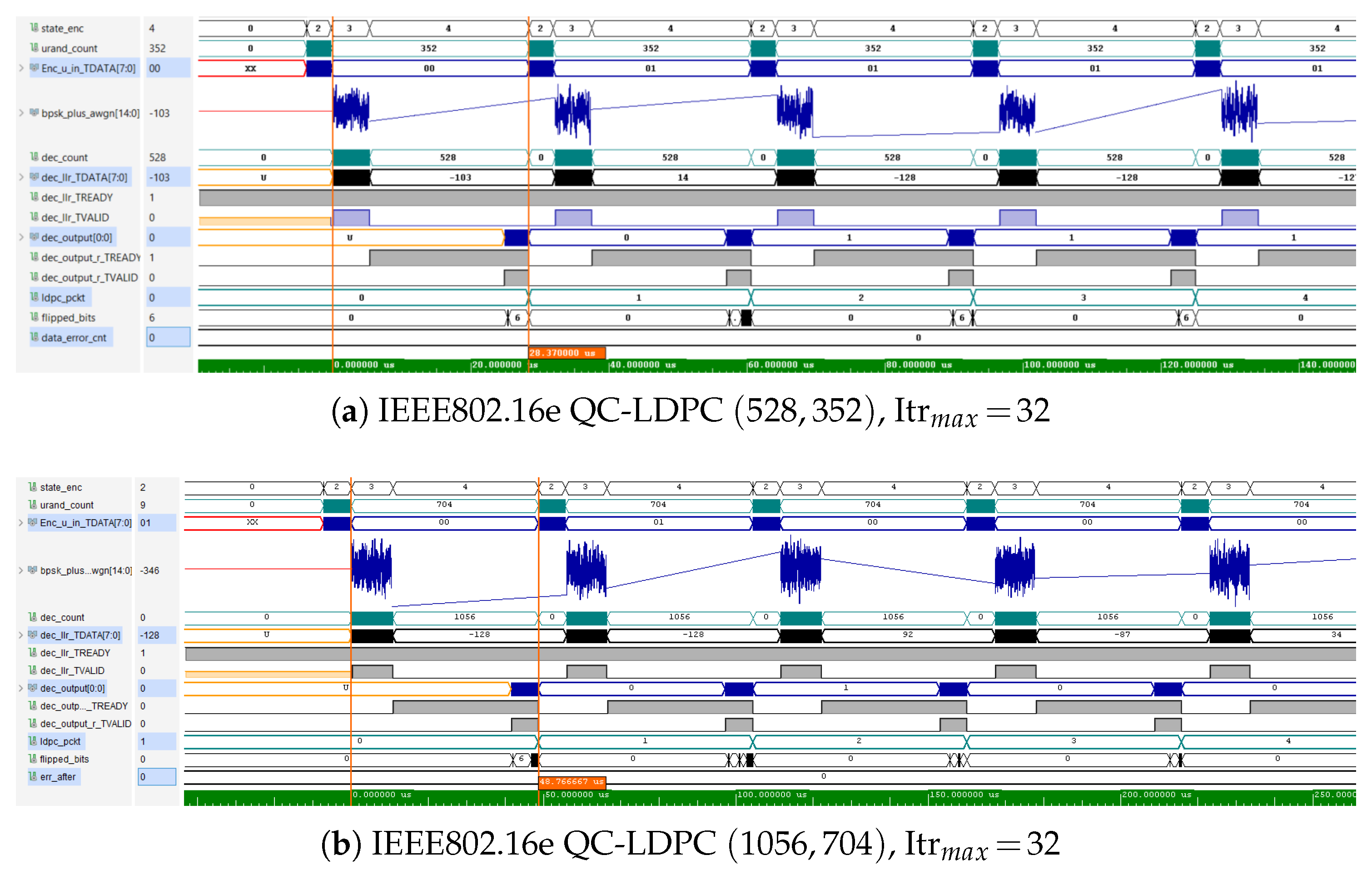

Figure 9 shows RTL simulation traces via Xilinx Vivado 2024. The left cursor aligns to the first valid AXI4-Stream LLR beat and the right cursor to the last valid hard-decision beat. The signal

dec_count ramps over

N samples during input, the decoder executes

iterations, and the design streams out

K bits. A bounded fill and drain overhead is visible in the AXI handshakes and is consistent with

cycles.

Equation (

14) gives

cycles and

cycles while Vivado reports 2037 cycles and 4876 cycles, respectively. The RTL values lie within the analytic bound and are shorter due to scheduler conservatism and the absence of backpressure.

8. Conclusion

This work presented an end-to-end FPGA implementation of a QC-LDPC decoder for VSATPlus systems using Vitis HLS and Vivado 2024. The primary contribution lies in demonstrating a practical design methodology for mapping advanced LDPC decoding techniques onto FPGA hardware through HLS-driven flows, enabling rapid prototyping and deployment without manual RTL development. The proposed architecture employs shift-and-subtract operations to eliminate multipliers and dividers, resulting in a DSP-free design optimized for resource-constrained satellite terminals.

The complete system integration was achieved using HLS-generated IP cores for the encoder, AWGN channel, and decoder. Under a 100 MHz and 400 MHz clock, the design achieves a coded-bit throughput of 29–41 Mbps and 116–164 Mbps, respectively, with moderate memory usage. Post-implementation Vivado power analysis reports an estimated dynamic power of 116 mW at 100 MHz for the encoder and 1.948 W at 400 MHz for the decoder, confirming suitability for low-power VSAT platforms. These values are consistent with reported figures for FPGA-based LDPC decoders of comparable block size (2064 bits) and code rates (1/2, 2/3, and 3/4) in the literature, where dynamic power typically ranges between 1.5 W and 3 W for high-throughput designs operating at 300–500 MHz. Fixed scaling factors were selected through empirical optimization to balance BER performance and hardware simplicity, avoiding the complexity overhead of adaptive scaling with negligible performance penalty.

Performance evaluation under AWGN, which is appropriate for GEO VSATPlus links with negligible Doppler and stable fading, shows near-BP decoding performance and no observable error floor down to . Compared to MS-family baselines, the implemented design achieves faster convergence and lower iteration counts, translating into reduced latency and higher throughput.

Future work will extend this HLS-based methodology to adaptive coding and modulation (ACM) and AI-assisted decoding for non-Gaussian channels, while incorporating detailed power and thermal profiling under realistic traffic conditions. These directions aim to further validate the practicality of HLS-driven FPGA deployment for next-generation satellite communication systems.

Appendix A. QC-LDPC Encoder

The QC-LDPC encoder implemented in this work is based on the

standard [

65], which introduces a harmonized definition of QC-LDPC codes for the OFDMA physical layer, developed collaboratively by six major industry contributors including Intel, Motorola, Nokia, Nortel, Samsung, and Texas Instruments. The proposed LDPC codes are based on structured base matrices expanded into large parity-check matrices using circulant permutation matrices. This method utilizes a recursive structure with circular shifts and XOR operations facilitating streamlined hardware implementation and efficient computational logic on FPGA platforms. The standard supports multiple code-rates (1/2, 2/3, and 3/4) and a wide range of block sizes through scalable expansion, shortening, and puncturing techniques making it well-suited for modern, high-throughput communication systems of VSATPlus satellite communications system.

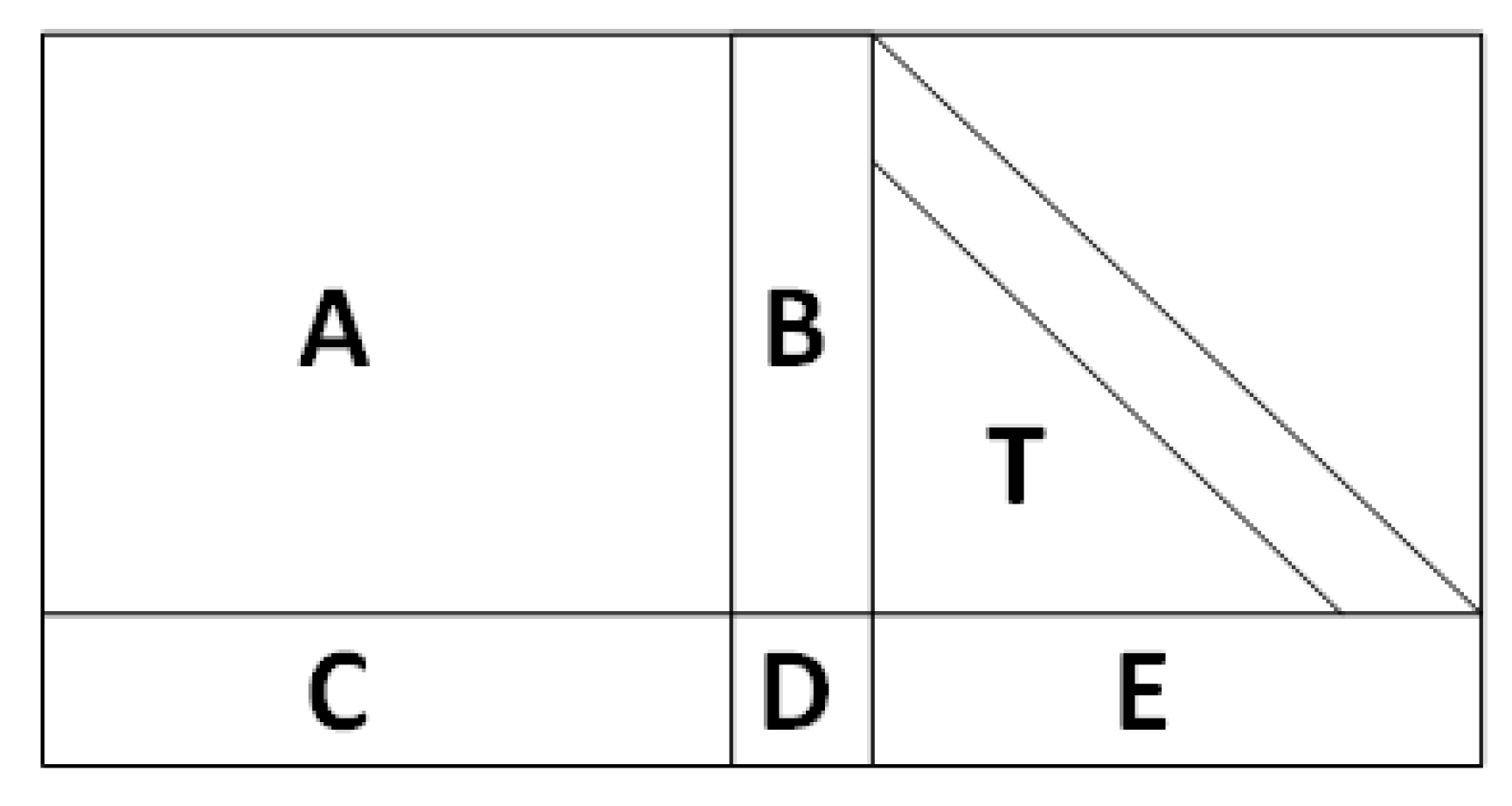

Appendix A.1. VSATPlus Encoder Algorithm

The VSATPlus QC-LDPC encoder leverages the Direct Encoding Method II as specified in the IEEE C802.16e-04/373r1 standard [

65]. This approach is grounded in a structured matrix-partitioning technique that facilitates deterministic, low-complexity encoding suitable for hardware implementation. As illustrated in

Figure A1, the parity-check matrix

H is decomposed into six submatrices:

,

,

,

,

, and

, with

T being a lower-triangular matrix characterized by ones along its main diagonal.

Figure A1.

Structure of the QC-LDPC parity-check matrix implemented for VSATPlus based on

[

65].

Figure A1.

Structure of the QC-LDPC parity-check matrix implemented for VSATPlus based on

[

65].

In the QC-LDPC selected for implementation and evaluation in this work, the instantiated parameters are: , , and for , respectively, where and denote the permutation-matrix rows and columns with lifting factor . The instantiate block lengths in our experiments are with the three code rates.

Given a systematic input vector

u, the encoding procedure begins with the computation of intermediate products

and

, followed by the application of the inverse transform

. The first set of parity bits, denoted

, is then computed according to:

which incorporates contributions from both the

C and

E matrices. Subsequently, the second set of parity bits,

, is obtained using:

where the input

u and partial parity

are jointly encoded via the lower-triangular transformation. A high-level depiction of this block-wise encoding flow is provided in

Figure A2.

Figure A2.

Block diagram of the

QC-LDPC encoder architecture [

65].

Figure A2.

Block diagram of the

QC-LDPC encoder architecture [

65].

The matrix sparsity and hierarchical decomposition yield a high-throughput, pipelined encoder design with minimal logic complexity. For a detailed derivation and theoretical justification of (

A1) and (

A2), refer to [

65].

Appendix A.2. FPGA Implementation of VSATPlus Encoder

The QC-LDPC encoder is implemented using Vitis HLS and synthesized for the Xilinx Zynq UltraScale+ device with a target system clock of 100 MHz. The implementation leverages extensive high level synthesis optimizations including loop pipelining, aggressive unrolling, and complete array partitioning. These transformations enable deep parallelism across matrix-vector computations and circular shift operations, particularly within encoding stages. A detailed summary of the post-RTL optimized resource utilization, latency, and throughput for the specific QC-LDPC codes is presented in

Table A1.

Table A1.

QC-LDPC Enecoder Resource Utilization.

Table A1.

QC-LDPC Enecoder Resource Utilization.

Figure A4 illustrates RTL simulation traces of the QC-LDPC encoder at

MHz in Vivado 2024. The left cursor is aligned to the first valid AXI4-Stream input beat, and the right cursor to the last valid output beat on the codeword port. Two counters ramps over the

accepted information bits, and the

emitted code bits. The output path exhibits no backpressure and only a bounded fill/drain overhead is visible in the handshakes. The measured span between cursors is 1787 cycles at 100 MHz which is aligned with the Vitis HLS report provided in

Table A1.

The simulation also verify the Gaussian noise source used for downstream link tests.

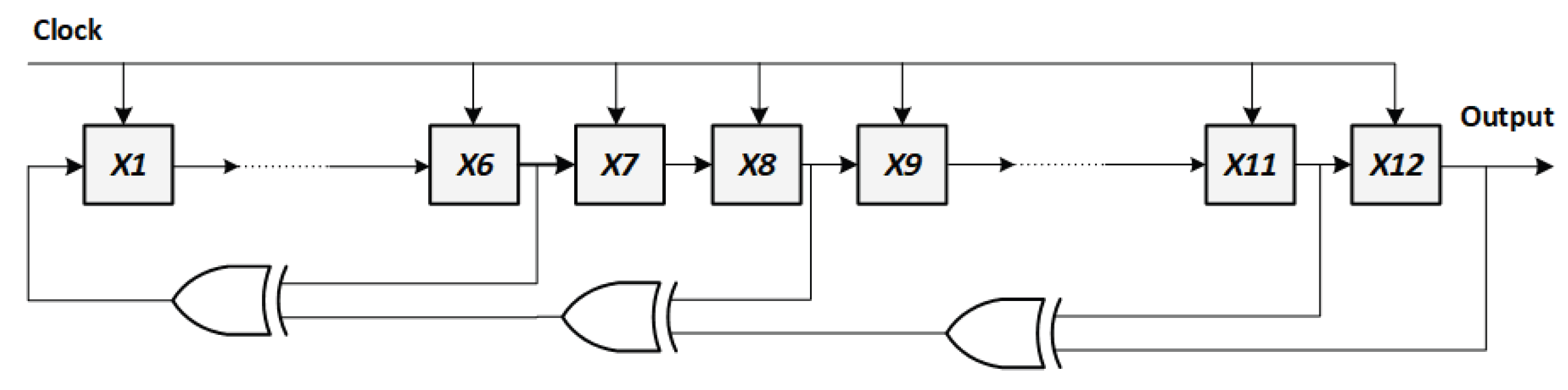

Figure A3.

12-bit LFSR with 1-bit output used in the Box-Muller method to generate i.i.d. random variable.

Figure A3.

12-bit LFSR with 1-bit output used in the Box-Muller method to generate i.i.d. random variable.

Figure A4.

Encoder latency analysis of QC-LDPC with MHz via Xilinx Vivado 2024.

Figure A4.

Encoder latency analysis of QC-LDPC with MHz via Xilinx Vivado 2024.

Appendix B. FPGA Implementation of an AWGN Channel

To evaluate QC-LDPC code in communication link, a dedicated AWGN noise generator is synthesized using Vitis HLS and integrated into the FPGA design via IP instantiation in Xilinx Vivado Design Suite. The generator is clocked at 100MHz and implements the Box-Muller transformation using fixed-point arithmetic and LUT-based approximations [

51]. The Box-Muller method converts two statistically independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables

into a pair of independent, standard normally distributed variables.

where,

. The FPGA-based AWGN generator is architected for cycle-accurate, pipelined synthesis of zero-mean Gaussian noise samples. To minimize hardware complexity and maximize throughput, computationally intensive functions, such as logarithmic operation, are replaced with high-resolution fixed-point LUTs generated offline using Python, which map i.i.d. random variables to radius values

, and

. Address generation for the LUTs is driven by two decorrelated 12-bit LFSRs, seeded independently and defined by the primitive polynomial of

as illustrated in

Figure A3. This primitive polynomial ensures maximal-length pseudo-random sequences. Each LFSR output is truncated to 10 bits, enabling indexed access to LUTs of size 1024, corresponding to a 10-bit address space. To maintain statistical zero-mean behavior, a DC offset correction stage is implemented using a programmable exponential moving average (EMA) applied to the noise sample. The DC bias estimate,

, is iteratively updated and he DC-corrected output is then computed as follows:

where

is a configurable smoothing coefficient. The bias-corrected sample is subsequently saturated to the 14-bit signed output range

. The entire architecture is fully pipelined, delivering one valid output sample per clock cycle.

On Xilinx Zynq UltraScale+ devices, the ARM-based PS provides the control plane for the AWGN IP, exposing all configuration knobs through an AXI4-Lite register file while the I/Q samples stream over AXI4-Stream. In our design, the PS programs noise standard deviation, EMA shift controlling the bias-removal time constant,

in (

A6), and the independent seeds that decorrelate the two LFSR-driven LUT address generators.

Table A2 summarizes post-synthesis resource usage for the AWGN IP-core, comparing HLS estimates to Vivado results. Overall utilization on the target device is very low, with single-digit DSP and BRAM usage, no URAM.

Table A2.

AWGN IP-Core Design Resource Utilization.

Table A2.

AWGN IP-Core Design Resource Utilization.

References

- Li, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Wang, G. An FPGA-Based LDPC Decoder with Optimized Scale Factor in NMS Decoding Algorithm. SSRN Electronic Journal 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossorier, M.P.C.; Mihaljevic, M.; Imai, H. Reduced complexity iterative decoding of low-density parity check codes based on belief propagation. IEEE Trans. Communications 1999, 47(5), 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J.C. Good error-correcting codes based on very sparse matrices. IEEE Trans. Information Theory 1999, 45(2), 399–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Fang, H.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z. Normalized Min-Sum Neural Network for LDPC Decoding. IEEE Trans. Cognitive Communications and Networking 2023, 9(1), 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Parhi, K.K. Min-Sum Decoder Architectures With Reduced Word Length for LDPC Codes. IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2010, 57(1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Shrestha, R. Low computational-complexity SOMS-algorithm and high-throughput decoder architecture for QC–LDPC codes. IEEE Trans. Vehicular Technology 2023, 72(1), 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, H.; Chan, H.-W.; Chiu, K.-L.; Tsai, P.-Y.; Jou, S.-J.J. A 75-Gb/s/mm2 and energy-efficient LDPC decoder based on a reduced complexity second minimum approximation min-sum algorithm. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems 2020, 28(4), 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Kong, B.Y.; Lee, Y. Area- and energy-efficient LDPC decoder using mixed-resolution check-node processing. IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2022, vol. 69(no. 3), 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dholakia, A.; Eleftheriou, E.; Fossorier, M.P.C.; Hu, X.-Y. Reduced-complexity decoding of LDPC codes. IEEE Trans. Communications 2005, 53(8), 1288–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.M. A turbo-decoding message-passing algorithm for sparse parity-check matrix codes. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing 2006, vol. 54(no. 11), 4376–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.J.; Urbanke, R.L. The capacity of low-density parity-check codes under message-passing decoding. IEEE Trans. Information Theory 2001, vol. 47(no. 2), 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Lee, C. Design of a high-throughput QC–LDPC decoder with TDMP scheduling. IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2015, vol. 62(no. 1), 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Huang, X.; Wang, Z. A high-throughput LDPC decoder architecture with rate compatibility. IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2011, vol. 58(no. 4), 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabiha, A.; Chan Carusone, A.; Kschischang, F.R. Power reduction techniques for LDPC decoders. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits 2008, vol. 43(no. 8), 1835–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delomier, Y.; Le Gal, B.; Crenne, J.; Jego, C. Model-based design of flexible and efficient LDPC decoders on FPGA devices. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 2020, vol. 92(no. 7), 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Smith, G. High-Level Synthesis: Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Design & Test of Computers 2009, vol. 26(no. 4), 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, B.; Jego, C.; Leroux, C. A flexible NISC-based LDPC decoder. IEEE Trans. Signal Processing 2014, vol. 62(no. 10), 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Sun, L.; Cao, Q. TLP-LDPC: Three-level parallel FPGA architecture for fast prototyping of LDPC decoder using high-level synthesis. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2022, vol. 37(no. 6), 1290–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaske, S.; Kee, H.; Ly, T.; Aziz, A.; Spasojevic, P. FPGA-Based Channel Coding Architectures for 5G Wireless Using High-Level Synthesis. International Journal of Reconfigurable Computing 2017, Article No. 3689308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Sha, J. 4.7-Gb/s LDPC Decoder on GPU. IEEE Communications Letters 2018, vol. 22(no. 3), 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.; Falcão, G.; Silva, V. Flexible design of wide-pipeline-based WiMAX QC-LDPC decoder architectures on FPGAs using high-level synthesis. IET Electronics Letters 2014, vol. 50, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaske, S.; Kee, H.; Ly, T.; Aziz, A.; Spasojevic, P. FPGA-Based Channel Coding Architectures for 5G Wireless Using High-Level Synthesis. Article ID 3689308; International Journal of Reconfigurable Computing. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wey, C.-L.; Shieh, M.-D.; Lin, S.-Y. Algorithms of finding the first two minimum values and their hardware implementation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Reg. Papers 2008, vol. 55(no. 11), 3430–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Fang, H.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z. Normalized min-sum neural network for LDPC decoding. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2023, vol. 9(no. 1), 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Parhi, K.K. Min-sum decoder architectures with reduced word length for LDPC codes. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I, Reg. Papers 2010, vol. 57(no. 1), 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossorier, M.P.C.; Mihaljević, M.; Imai, H. Reduced complexity iterative decoding of low-density parity-check codes based on belief propagation. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1999, vol. 47(no. 5), 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.M. A recursive approach to low complexity codes. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1981, vol. 27(no. 5), 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Jeon, S.; Mai, K.; Vijaya Kumar, B.V.K. Highly parallel FPGA emulation for LDPC error floor characterization in perpendicular magnetic recording channel. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2009, 45(10), 3761–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossorier , M.P.C. Quasicyclic low-density parity-check codes from circulant permutation matrices. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2004, 50(8), 1788–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.; Cho, K.; Lee, W.-H. Simplified 2-dimensional scaled min-sum algorithm for LDPC decoder J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2017, 12(no. 3), 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Guo, S.; Xu, X.; Bai, H. A classified normalized BP-based algorithm with 2-dimensional correction for LDPC codes. J. Commun. 2013, vol. 8(no. 5), 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A. Estimation of two-dimensional correction factors for min-sum decoding of regular LDPC code. Wireless Eng. Technol. 2013, 4(4), 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.K.; Jayabalan, R. An improved low-complexity sum-product decoding algorithm for low-density parity-check codes. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2015, 16(6), 511–518. [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal, B.; Jego, C. Low-latency software LDPC decoders for x86 multi-core devices. Proc. the 2017 IEEE International Workshop on Signal Processing Systems (SiPS), 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, N.; Loeliger, H.-A.; Kotter, R. Codes and iterative decoding on general graphs. In Proc. 1995 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT); IEEE: Whistler, BC, Canada, 1995; p. pp. 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncalo, O.; Amaricai, A. Ultra high throughput unrolled layered architecture for QC-LDPC decoders. Proc. the 2017 IEEE Computer Society Annual Symposium on VLSI (ISVLSI), Bochum, Germany, 2017; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Jing, S.; Yu, A.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Z.; You, X.; Zhang, C. Reconfigurable decoder for LDPC and polar codes. Proc. 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Florence, Italy, 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, T.; Sundaramurthy, V.; Stolpman, V.; McCain, D. Pipelined block-serial decoder architecture for structured LDPC codes. Proc. 2006 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics Speech and Signal Processing Proceedings (ICASSP), Toulouse, France, 2006; vol. 4, p. IV. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkeen, S.A.; Hamad, A.A. FPGA implementation of scaled “Quasi-Cyclic LDPC” decoder using high-level synthesis. First International Conference on Mathematical Modeling and Computational Science: ICMMCS 2020, Pattaya, Thailand, 2021; pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Jiao, X.; Jääskeläinen, P.; Kultala, H.; Chen, C.; Berg, H.; Bie, Z. A high throughput LDPC decoder using a mid-range GPU. Proc. 2014 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Florence, Italy, 2014; IEEE; pp. 7515–7519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiber, E.; Bruck, G.H.; Jung, P. Implementation of an LDPC decoder for IEEE 802.11n using Vivado™ High-Level Synthesis. Proc. 2013 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Signal Processing and Communication Systems, 2013; no. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, J.; Pratas, F.; Falcao, G.; Silva, V.; Sousa, L. Combining flexibility with low power: Dataflow and wide-pipeline LDPC decoding engines in the Gbit/s era. Proc. 2014 IEEE 25th International Conference on Application-Specific Systems, Architectures and Processors (ASAP), 2014; pp. 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaske, S.; Kee, H.; Ly, T.; Aziz, A.; Spasojevic, P. High-Throughput FPGA-Based QC-LDPC Decoder Architecture. Proc. 2015 IEEE 82nd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2015-Fall), 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zied, S.A.; Sayed, A.T.; Guindi, R. Configurable low complexity decoder architecture for Quasi-Cyclic LDPC codes. Proc. 2013 21st International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM), 2013; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyanon, I.; Choomchuay, S. A hardware design of MS/MMS-based LDPC decoder. Proc. 2012 IEEE International Conference on Electron Devices and Solid State Circuits (EDSSC), 2012; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, B.; Jego, C. Design of an ASIP LDPC Decoder Compliant with Digital Communication Standards. Proc. 2012 IEEE Workshop on Signal Processing Systems (SiPS), 2012; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.H.; Long, J.P. Implementing the NASA Deep Space LDPC Codes for Defense Applications. Proc. 2013 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), 2013; pp. 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaricai, A.; Boncalo, O.; Mot, I. Memory efficient FPGA implementation for flooded LDPC decoder. Proc. 2015 23rd Telecommunications Forum (TELFOR), Belgrade, Serbia, 2015; pp. 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignoly, V.; Le Gal, B.; Jego, C.; Gadat, B. High data rate and flexible hardware QC-LDPC decoder for satellite optical communications. Proc. 2018 IEEE 10th International Symposium on Turbo Codes & Iterative Information Processing (ISTC), 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosroshahi, N.; Gulliver, T.A. Quasi-cyclic low density parity check (LDPC) codes for dedicated short range communication (DSRC) systems. Proc. 2010 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Calgary, AB, Canada, 2010; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlan, A.; İnceöz, E.; Balcısöy, E.; Özbek, M.; Çavuş, E. FPGA implementation of AWGN noise generator using Box–Muller method. Proc. IEEE SIU, May 2016; pp. 1813–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.A.; Fleetwood, T. Hubless VSAT networks. IEE Colloquium on VSATs—Trends and Technologies, 1989; pp. 5/1–5/13. [Google Scholar]

- Khosroshahi, N.; Mankarious, R.; Soleymani, M.R. CNN-Based LDPC Decoder for Hubless Full-Mesh VSATPlus® System. Proc. IEEE/AIAA Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC) to be published, 2025. [Google Scholar]

-

IEEE Std 802.16TM; IEEE Standard for Local and metropolitan area networks - Part 16: Air Interface for Broadband Wireless Access Systems. 2009.

-

IEEE Std 802.11n; IEEE Standard for Local and metropolitan area networks - Specific requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications. 2009.

-

IEEE Std 802.11ad; IEEE Standard for Local and metropolitan area networks - Specific requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications. 2007.

-

TS V5G.212 V1.2; Verizon 5G Technical Forum; Air Interface Working Group; Verizon 5th Generation Radio Access; Multiplexing and channel coding (Release 1). 2016.

-

3GPP TS 38.212 V15.2.0; 3rd Generation Partnership Project; Technical Specification; 5G; NR; Multiplexing and channel coding. 2018.

-

ETSI EN 302 307 V1.4.1; Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Second generation framing structure, channel coding and modulation systems for Broadcasting, Interactive Services, News Gathering and other broadband satellite applications (DVB-S2). 2009.

-

ETSI EN 302 769 V1.3.1; Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Frame structure, channel coding and modulation for a second generation digital transmission system for cable systems (DVB-C2). 2009.

-

ETSI EN 300 744 V1.6.1; Digital Video Broadcasting (DVB); Framing structure, channel coding and modulation for digital terrestrial television (DVB-T). 2009.

-

ETSI ES 300 401 V1.4.1; Radio Broadcast systems; Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) to mobile, portable and fixed receivers. 1995.

-

ETSI GSM 05.05; Digital cellular telecommunications system (Phase 2+); Radio transmission and reception (GSM). 1996.

-

ETSI TS 136 201 V15.2.0; Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access (E-UTRA); LTE physical layer—General description. 2017.

- IEEE 802.16 Working Group LDPC coding for OFDMA PHY Contribution to IEEE 802.16e, Aug. 2004. Available online: http://ieee802.org/16/tge/contrib/C80216e-04_373r1.pdf.

- PolarSat Inc. VSATPlus3® Overview 2003. Available online: https://www.polarsat.com/vsatplus-3.

- AMD Xilinx. Vivado Design Suite User Guide: High-Level Synthesis UG902 V2020.1

. May 2021. Available online: https://docs.amd.com/v/u/en-US/ug902-vivado-high-level-synthesis.

- Wiberg, N. Codes and decoding on general graphs. Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. Elect. Eng., Linköping Univ., Sweden, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Short Biography of Authors

|

Najmeh Khosroshahi (Member, IEEE) received the B.Sc. degree in electrical

and computer engineering from the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, in 2007,

and the M.Sc. degree in electrical and computer engineering from the

University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada, in 2011. She is currently pursuing

the Ph.D. degree in electrical and computer engineering at Concordia

University, Montréal, QC, Canada. She is a Digital Communication Systems

Engineer with PolarSat Inc., Montréal, QC, Canada, developing and verifying

FPGA-centric signal-processing for VSAT platforms. Her current research

interests include error-correcting codes, artificial intelligence (AI),

quantum/learning-assisted decoding, and satellite communications. She is the

author of Inter-Vehicle Communication Systems Improvement (LAP LAMBERT

Academic Publishing, 2014). |

|

Ron Mankarious (Member, IEEE) received the B.Sc. degree in electrical

engineering and the B.A. degree in economics from the University of

California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, USA, in 1985. He is

currently the Executive Vice President of Sales and Marketing with PolarSat

Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada, which he co-founded in 2003. Previously, he held

management and engineering positions with NSI Communications,

ComStream Corporation, Interstate Electronics, and Hughes Aircraft

Company, all in California, USA. He has more than 40 years of experience in

wireless and satellite communications and has authored IEEE papers on

wireless adaptive routing and error-correction coding, as well as articles on

satellite communications in leading industry publications. His current

professional interests include satellite networking, adaptive routing, and

forward error correction for MF–TDMA systems. |

|

M. Reza Soleymani (Senior Member, IEEE) received the B.S. degree in

electrical engineering from the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, in 1976, the

M.S. degree in electrical engineering from San Jose State University, San Jose,

CA, USA, in 1977, and the Ph.D. degree in electrical engineering from

Concordia University, Montréal, QC, Canada, in 1987. From 1987 to 1990, he

was an Assistant Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at

McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada. From 1990 to 1998, he was with

EMS Technologies Ltd. (formerly Spar Aerospace Ltd.), where he had a

leading role in the design and development of several satellite

communications systems. In 1998, he joined the Department of Electrical and

Computer Engineering at Concordia University, Montréal, QC, Canada, where

he is presently a Professor. His current research interests include digital

communications, satellite communications, communications networks,

information theory and coding, and data compression and source coding. He

holds several patents and has coauthored a book, Turbo Coding for Satellite and

Wireless Communications (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002), as well as a

number of book chapters in the field. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |