1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies certain multidrug-resistant strains of

Escherichia coli (like carbapenem-resistant and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacterales) as Critical Priority Pathogens due to their significant threat in hospital settings and their ability to easily share genetic resistance mechanisms. This designation underscores the urgent global need for new antibiotics and research and development against these highly threatening bacteria [

1]. The global dissemination of AMR is frequently attributed to specific, highly successful bacterial clones, often referred to as high-risk clonal lineages. These lineages are characterized by genetic plasticity that facilitates the stable acquisition and mobilization of resistance and virulence determinants [

2].

Traditional short-read sequencing methods are excellent for identifying resistance and virulence genes, but often fail to accurately assemble the large, repetitive mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as plasmids, which carry these genes [

3]. This inability to fully resolve plasmid structure hinders understanding of AMR transmission dynamics, specifically how resistance and virulence genes are clustered and transferred between bacteria.

The advent of Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing, a third generation, long-read platform, offers a robust solution. By generating extremely long reads, ONT allows for the de novo assembly of complete, closed bacterial chromosomes and plasmids [

4]. This capability is vital for determining the exact location of MDR genes (chromosomal vs. plasmid-encoded), characterizing the genomic architecture of the MGEs (e.g., transposons, integrons) that mediate gene transfer and providing high-resolution phylogenetic analysis to trace the local and regional spread of ST224 isolates. It will be fully resolved about their genome and plasmid structures to identify the complete resistome (AMR genes), virulome (virulence genes), and mobilome (plasmid types and MGEs), thereby illuminating the mechanisms driving the multidrug resistance and pathogenic potential of ST224 in Myanmar.

One such clone of increasing concern worldwide is Sequence Type 224 (ST224) of

E. coli. While ST224 is recognised as an emergent, high-risk lineage associated with extra-intestinal pathogenic

E. coli (ExPEC) and MDR phenotypes in various global settings, its specific genomic features, resistance mechanisms, and epidemiological footprint in Southeast Asia, particularly Myanmar, remain largely underexplored [

5].

Southeast Asia is identified as a significant global hotspot for AMR due to a confluence of factors, including high antibiotic usage, the integration of human and animal health sectors, and limited surveillance capacity [

6]. Myanmar, as a rapidly developing country in this region, is especially vulnerable to the transmission and establishment of high-risk MDR clones. Comprehensive genomic surveillance is essential to track the emergence and spread of these pathogens, but often, data from Myanmar is rare. As a result, detailed local studies are critically needed to inform effective national antimicrobial stewardship and infection control policies.

The present study addresses this limitation and marks a significant step in the country's public health technology by employing Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing, representing one of the first applications of this long-read sequencing technology for bacterial genomic characterization in Myanmar. Given the global threat posed by the MDR ST224 lineage and the critical gap in genomic surveillance data from Myanmar, this study aims to comprehensively characterize MDR ST224 E. coli isolates using Oxford Nanopore Sequencing. The portability, low operating cost, and ONT's ability to generate extremely long reads are particularly advantageous in resource-limited settings. This capability is vital for achieving complete, closed assemblies of bacterial genomes and their associated plasmids, providing an unprecedented level of resolution for epidemiological analysis that was previously unattainable within the country.

2. Materials and Methods

Five multidrug-resistant (MDR) Escherichia coli isolates which were investigated by Vitek2 were collected from the department of microbiology at (No.1) Defense Service General Hospital (DSGH), located in Yangon, Myanmar. This study was executed as a descriptive laboratory study entirely performed at the Defense Services Medical Research Centre Laboratory, Naypyitaw. This research was conducted over a duration of approximately one year. This study was reviewed and approved by Defense Services Medical Research Centre/IRB (Approval No.: IRB/2025/A-20). The isolates were taken from DSGH as transport media and cultured in nutrient broth and incubated overnight in preparation for genomic sequencing at DSMR Laboratory.

2.1. Genomic DNA Extraction

High molecular weight (HMW) genomic DNA was extracted from the single bacterial isolate using DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kits (Cat no. / ID. 69506) following the manufacturer's protocol for Gram-negative bacteria [

7]. DNA purification was done by Thermo Scientific CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Catalogue number K123) [

8]. DNA concentration and purity were assessed using a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively. Extracted DNA was confirmed to be of sufficient quantity and quality for long-read sequencing according to the SQK-nbd114-24 whole genome protocol [

9].

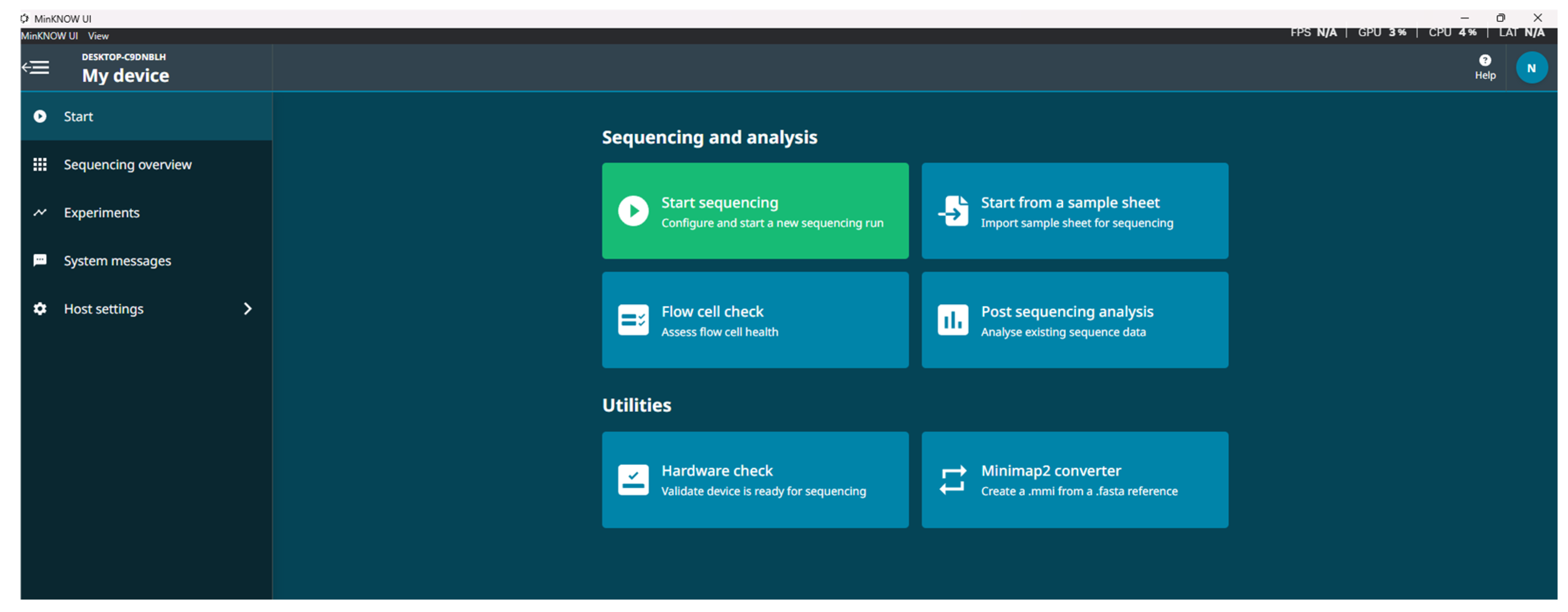

2.2. Nanopore Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Whole-genome sequencing was performed using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) platform to achieve a complete, high-resolution assembly. The DNA library was prepared using the Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-NBD114-24), which enables Native Barcoding (NB) for sequencing on the MinION device. The preparation followed the standard protocol for generating long reads, suitable for full plasmid and chromosome closure. The prepared library was loaded onto a primed R10.4.1 flow cell. Sequencing was carried out on the MinION device, controlled by the MinKNOW software [

10]. Real-time basecalling was performed within MinKNOW, utilising the Super Accuracy (Sup) model to maximize read quality and accuracy (

Figure 1).

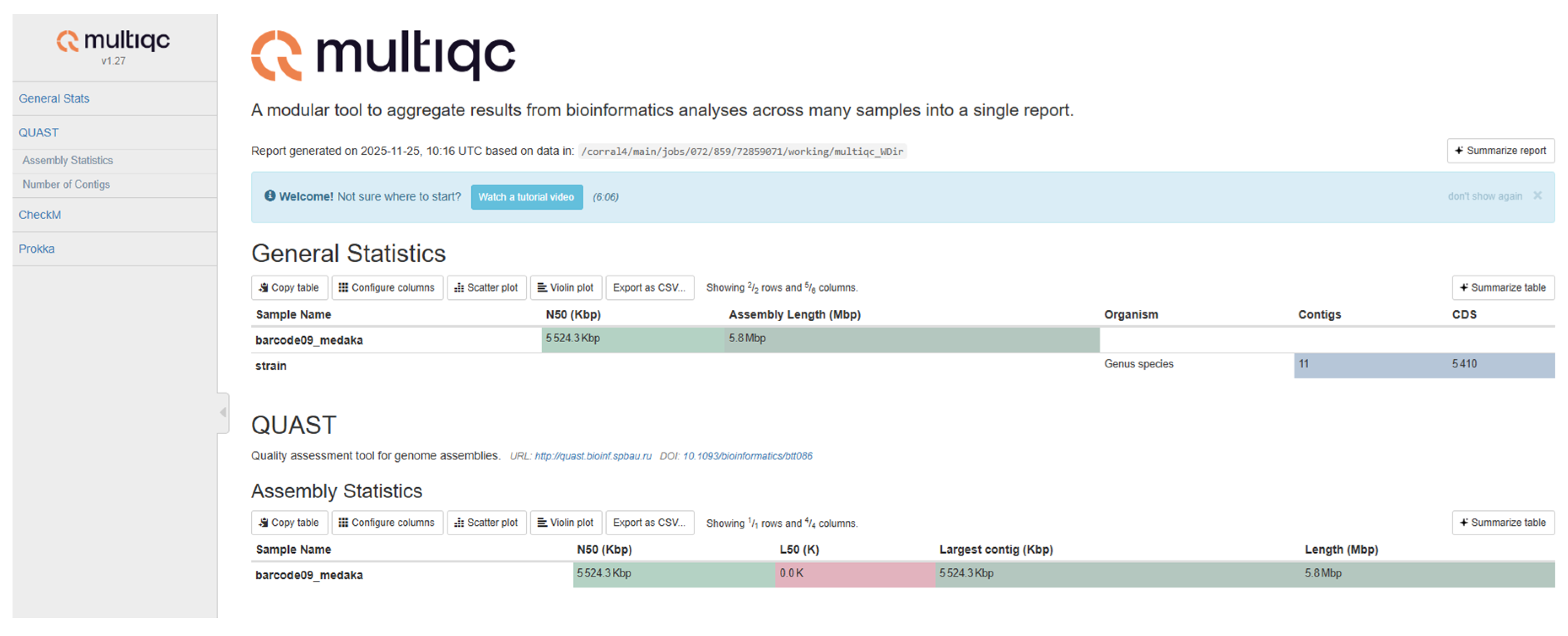

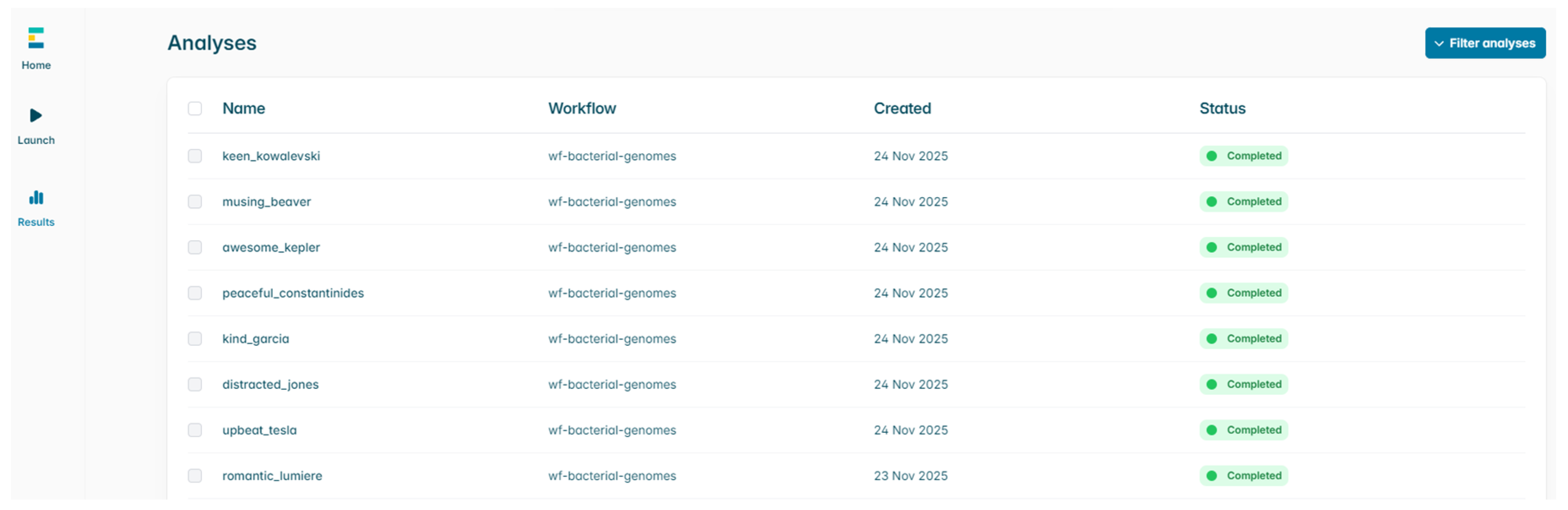

2.3. Bioinformatics and Genomic Analysis

Raw sequencing reads were processed using a comprehensive bioinformatics pipeline to achieve a complete, closed genome assembly and detailed genomic characterization. Initial quality control, filtering, and demultiplexing of raw reads were performed using the default workflows within the ONT EPI2ME platform, specifically the wf-bacteria-genome analysis workflow, which is optimized for bacterial genome analysis (

Figure 2). The resulting high-quality reads were used for de novo assembly, aiming for a single, closed circular contig for the chromosome and for each extrachromosomal plasmid [

11]. The final assembly was confirmed using visualization tools to ensure circularity and correctness. The complete assembled genome was subsequently used as the input FASTA file for downstream analyses within the Galaxy bioinformatics platform [

12].

2.5. Sequence Typing and Annotation

The Sequence Type (ST) was determined using the assembled genome against the Achtman scheme for

E. coli within the MLST tool (Centre for Genomic Epidemiology), confirming the isolate as ST224. The assembled genome was annotated using Prokka (version 1.14.6) to identify coding sequences (CDS), rRNA, and tRNA genes, providing a comprehensive functional map of the isolate’s entire genome [

12].

2.6. Resistome and Mobilome Profiling

High-resolution analysis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes and mobile genetic elements (MGEs) was performed to identify AMR genes (Resistome). The presence of known AMR genes was screened using ABRICate (version 1.0.1) against the ResFinder database (v4.1). Plasmid content was analyzed using PlasmidFinder (v2.1) to identify known plasmid incompatibility groups (replicons) and their location within the assembled contigs. All workflows were accessed in the Centre for Genomic Epidemiology [

12].

3. Results

3.1. Quality Control and Assembly Statistics

Out of five barcoding from each multidrug-resistant (MDR)

Escherichia coli isolate, DMR

E. coli (NMA_MM001) of ONT sequencing successfully generated a high-quality, near-closed assembly (N50: 4,911,841 bp, 5 contigs). The genome sequence of DMR

E. coli (NMA_MM001) isolate (designated barcode07_medaka) was assembled using a long-read pipeline (Flye followed by Medaka polishing) and assessed for quality and contiguity using multiQC (Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies) (

Figure 3). The final assembly was highly contiguous, totaling 5,070,303 base pairs. The assembly demonstrated near-closure, with the largest contig spanning 4,911,841 bp representing approximately 97% of the total genome size. The assembly's base-level quality was exceptionally high. The overall GC content was measured at 50.97%. Crucially, the final assembly contained zero ambiguous bases (N's), confirming the high sequence accuracy achieved through the Medaka polishing process. The QC report confirms a successful de novo genome assembly, resulting in a sequence of very high contiguity and base-level accuracy suitable for downstream genomic analysis. The studied isolate was submitted to the NCBI database as a BioProject (BioProject ID: PRJNA1372388). It was uploaded to the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and released in accordance with NCBI guidelines. [

13].

Figure 3.

QC report of DMR E. coli (NMA_MM001) (Designated as barcode07_medaka).

Figure 3.

QC report of DMR E. coli (NMA_MM001) (Designated as barcode07_medaka).

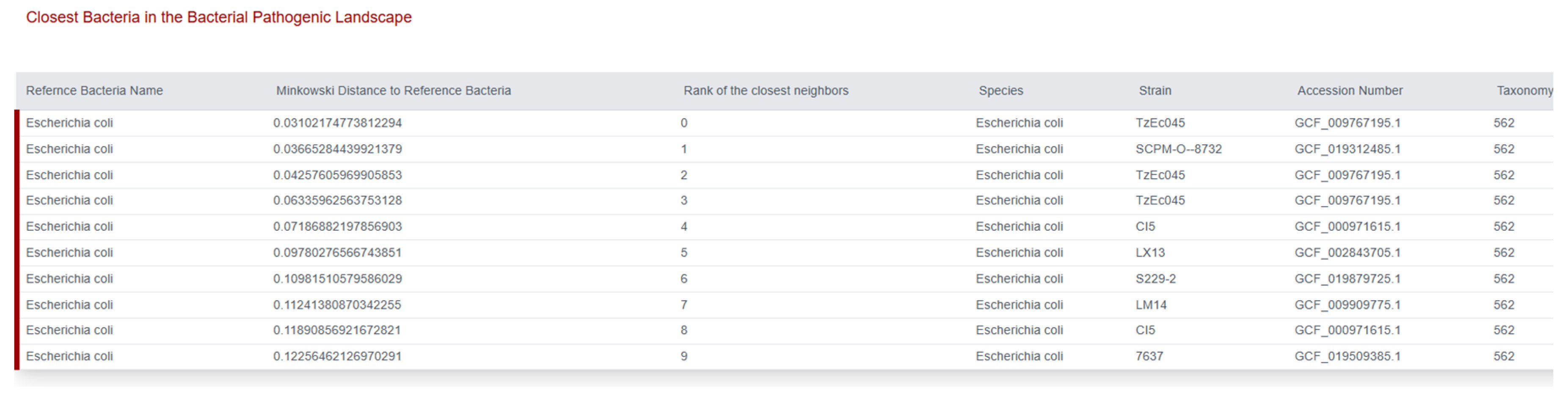

3.2. Phylogenomic Relationship to Reference Strains

To establish the phylogenomic relationship of the isolate were conducted using tools provided by the Centre for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) databases. The analysis, based on the Minkowski distance, confirmed that the isolate belongs to the species

Escherichia coli. The isolate showed the highest genomic similarity to the reference strain,

Escherichia coli TzE045 (GCF_009767195.1) (

Figure 3), with the smallest Minkowski distance of 0.03102. The second closest neighbor was identified as

E. coli SCPM-tO-8732 (GCF_00366284439921379), further confirming its close association with highly similar clinical isolates within the

E. coli pathogenic landscape. This result substantiates the genetic context and potential epidemiological linkage of the studied isolate [

14].

Figure 3.

Pathogen Finder of Centre for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) shows Escherichia coli TzE045.

Figure 3.

Pathogen Finder of Centre for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) shows Escherichia coli TzE045.

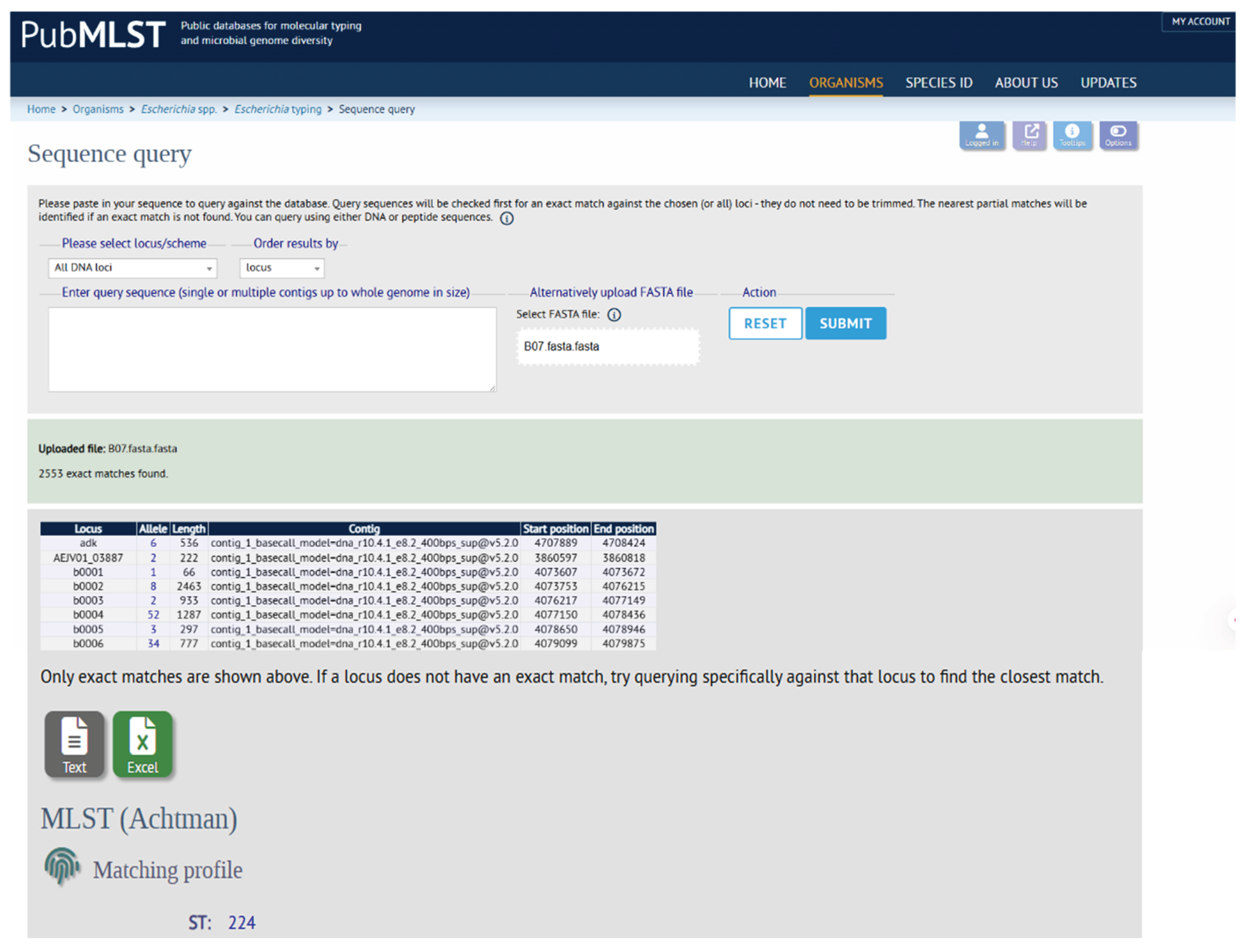

3.4. Molecular Typing and Plasmid Analysis

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) analysis classified the isolate under the

E. coli Achtman scheme, assigning it to Sequence Type ST224 (

Figure 4). Analysis of the assembled genome identified three distinct incompatibility (Inc) groups, indicating the presence of multiple plasmids. These included IncFIA and IncFIB, both linked to the replicon AP001918, and IncFII, which was explicitly associated with the plasmid pAMA1167-NDM (accession number CP024805) (

Table 1). The presence of IncF-type plasmids is highly significant, as these groups are large, broad-host-range plasmids frequently implicated in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes, such as the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase (NDM-5), as indicated by the pAMA1167-NDM-5 nomenclature.

3.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Gene (ARG) Profile

Analysis of the assembled genome sequence revealed 12 distinct antimicrobial resistance genes, confirming that the isolate exhibits a significant multidrug-resistant phenotype. The identified ARGs confer predicted resistance across seven major antibiotic classes (

Table 2). The

blaDHA-1 and

blaTEM-1. The

blaDHA-1 gene is particularly notable, as it confers resistance to a broad spectrum of agents, including penicillins, ampicillin, and early cephalosporins (cefoxitin) and ceftazidime, often indicating an

AmpC beta-lactamase. Co-resistance to aminoglycosides was confirmed by the presence of the

aadA-2 gene, which mediates resistance to streptomycin and spectinomycin.

Further resistance mechanisms were identified across several other classes. Three distinct genes, ermB, mphA, and msrE, confer resistance to the macrolide class, specifically erythromycin and azithromycin, often through ribosomal modification or efflux. The presence of qnrB, a plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene, predicts resistance to quinolones (ciprofloxacin). Finally, the isolate carries tetB, which mediates tetracycline and doxycycline resistance via efflux, as well as genes conferring resistance to trimethoprim (dfrA) and sulfonamides (sul1). The comprehensive nature of this ARG profile underscores the significant clinical challenge posed by this isolate.

4. Discussion

The whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and subsequent bioinformatics analysis of the Escherichia coli isolate NMA_MM001 provide critical insights into the circulating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threats and clearly demonstrate the utility of modern sequencing technology in the Myanmar context.

4.1. The Role of Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) in Genomic Surveillance

The exceptional quality of the assembly statistics (Total length: 5,070,303 bp, N50: 4,911,841 bp, and, notably, only five contigs) strongly validates the successful application of ONT long-read sequencing coupled with a robust assembly and polishing pipeline. The intrinsic capability of ONT to generate long reads is highly advantageous for bacterial genomics, as it effectively resolves complex genomic structures, spans repetitive regions, insertion elements, and, most critically, facilitates the complete resolution of entire circular plasmid sequences. This capability is indispensable in resource-limited settings such as Myanmar, where rapid, affordable, and accurate genomic surveillance is a public health imperative. The effective deployment of this technology establishes a robust foundation for future, real-time epidemiological tracking of pathogenic lineages within the nation.

4.2. Epidemiological Lineage and Phylogenomic Context

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) classified the isolate under the

E. coli Achtman scheme, assigning it to Sequence Type ST224. The identification of the NDM-5-producing

E. coli ST224 isolate (NMA_MM001) in this study, which harbors a multi-drug resistance profile and the

blaNDM-5 gene on an IncFII plasmid, marks the first detection of this high-risk lineage and its associated carbapenemase in Myanmar. This finding closely parallels international reports linking the ST224 lineage to other central resistance mechanisms, such as CTX-M-8, in animal reservoirs, underscoring the lineage's capacity to acquire critical antimicrobial resistance genes. [

15,

16].

Consequently, the established presence of NDM-5 on a highly mobile IncFII plasmid necessitates the urgent implementation of One Health surveillance across human and animal populations to prevent the regional establishment and horizontal transfer of this crucial resistance threat. The phylogenomic analysis confirmed the closest genomic relationship to the reference strain E. coli TzE045 (GCF_009767195.1), yielding the smallest Minkowski distance (0.03102). This high degree of similarity suggests a near-clonal relationship with a defined cluster of clinical isolates, underscoring the need to investigate potential epidemiological linkages and transmission dynamics associated with this strain.

4.3. Mobile Genetic Elements and the Spread of NDM-5

The most consequential finding of this genomic investigation is the molecular evidence supporting the active dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants via mobile genetic elements. The isolate was confirmed to harbor three F group Inc-type plasmids (IncFIA, IncFIB, and IncFII), which are characterized by their large size, high mobility, and capacity to facilitate extensive horizontal gene transfer (HGT) across diverse bacterial species [

17].

The identification of

blaNDM-5 producing E. coli ST224 carrying an IncFII plasmid mirrors the critical findings from the Italian study of ST167 and the Chinese research on ST410, confirming that the rapid spread of carbapenem resistance is driven by the highly mobile plasmid rather than confined to a single bacterial clone. The detection of this multi-drug resistant (MDR) ST224 lineage associated with clinical infections, such as UTIs, reinforces its status as a successful Extraintestinal Pathogenic

E. coli (ExPEC) lineage and demands immediate localised infection control measures. The presence of additional resistance genes, including those for quinolones (

qnrB) and macrolides, in this ST224 isolate significantly complicates therapeutic management by severely restricting treatment options. This convergence of high-level resistance and high plasmid mobility across distinct

E. coli backgrounds highlights the accelerated global dissemination of NDM-5 resistance. Consequently, a One Health approach is imperative for monitoring IncFII plasmids in all potential reservoirs, human, animal, and environmental, to mitigate this rapidly evolving public health threat effectively. [

18,

19]. The identified NDM-5-producing

E. coli ST224 strain, carrying its resistance genes on a mobile IncFII plasmid, highlights the urgent need for One Health surveillance across human and animal populations to contain the spread of this critical carbapenem resistance mechanism, which is circulating across multiple

E. coli lineages.

4.4. The Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) Phenotype

The comprehensive AMR gene profile confirms the isolate's multidrug-resistant phenotype. The isolate's comprehensive multidrug-resistant (MDR) phenotype, confirmed by

blaDHA-1 and

blaTEM-1, which severely limits beta-lactam activity, is further compounded by two distinct plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) mechanisms (

qepA and

qnrB4) and three macrolide resistance genes, underscoring the intense selective pressure driving the acquisition of diverse resistance factors. This study, characterized by the simultaneous identification of such an extensive array of AMR genes across seven classes in a single clinical isolate, represents the first report detailing this high level of genomic complexity in

E. coli in Myanmar, aligning with the alarming global increase in antimicrobial resistance mediated by beta-lactamase enzymes at the One Health interface. [

20,

21]The co-occurrence of two different quinolone resistance genes suggests intense selective pressure within the host environment. Three separate genes (

ermB,

mphA, and

msrE) mediating macrolide resistance were found, further limiting treatment options. [

22]. The confirmed high percentage identity (98.95-100) of all ARGs (CGE) tools validates the functional relevance of these genes.

5. Conclusion

This study successfully applied Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) to characterize a multidrug-resistant E. coli isolate (NMA_MM001) in Myanmar out of each barcoding of five isolates. The key outcome is the validation of ONT as an indispensable tool for public health genomics in resource-limited settings, demonstrating its capacity to produce complete, high-quality bacterial assemblies (N50 of 4,911,841 bp) essential for resolving complex mobile genetic elements. The findings confirm the co-occurrence of ST224 with a highly mobile IncFII plasmid carrying the critical NDM-5 carbapenemase gene. Furthermore, the isolate harbors ARGs conferring resistance across seven antibiotic classes, including beta-lactams and quinolones. This detailed genomic information provides an early warning of the local establishment of a highly virulent, multidrug-resistant strain, necessitating the urgent implementation of targeted infection control measures and regional AMR surveillance programs based on timely WGS data.

References

- Antimicrobial resistance [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Baquero, F; Martínez, JL; F. Lanza, V; Rodríguez-Beltrán, J; Galán, JC; San Millán, A; et al. Evolutionary Pathways and Trajectories in Antibiotic Resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021, 34, e00050-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Escalona, N; Allard, MA; Brown, EW; Sharma, S; Hoffmann, M. Nanopore sequencing for fast determination of plasmids, phages, virulence markers, and antimicrobial resistance genes in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. In PLOS ONE; DebRoy, C, Ed.; 2019; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Scarano, C; Veneruso, I; De Simone, RR; Di Bonito, G; Secondino, A; D’Argenio, V. The Third-Generation Sequencing Challenge: Novel Insights for the Omic Sciences. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flament-Simon, SC; De Toro, M; García, V; Blanco, JE; Blanco, M; Alonso, MP; et al. Molecular Characteristics of Extraintestinal Pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), and Multidrug Resistant E. coli Isolated from Healthy Dogs in Spain. Whole Genome Sequencing of Canine ST372 Isolates and Comparison with Human Isolates Causing Extraintestinal Infections. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambraki, IA; Chadag, MV; Cousins, M; Graells, T; Léger, A; Henriksson, PJG; et al. Factors impacting antimicrobial resistance in the South East Asian food system and potential places to intervene: A participatory, one health study. Front Microbiol. 2023, 13, 992507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits | DNA Purification | QIAGEN [Internet]. Available online: https://www.qiagen.com/us/products/discovery-and-translational-research/dna-rna-purification/dna-purification/genomic-dna/dneasy-blood-and-tissue-kit?catno=69506 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit 20 Reactions | Contact Us | Thermo ScientificTM | thermofisher.com [Internet]. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/catalog/product/K1231 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies [Internet. Ligation sequencing gDNA - Native Barcoding Kit 24 V14 (SQK-NBD114.24). 2022. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/document/ligation-sequencing-gdna-native-barcoding-v14-sqk-nbd114-24 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies [Internet]. 2017. MinKNOW. Available online: https://nanoporetech.com/document/experiment-companion-minknow (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- EPI2ME. 2025. Oxford Nanopore Open Data project. Available online: https://epi2me.nanoporetech.com/dataindex/ (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Galaxy [Internet]. Available online: https://galaxy-main.usegalaxy.org/workflows/invocations/9ee4a409076c2af7?success=true (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- BioProject - NCBI [Internet]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1372388 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Tatusova, T; Ciufo, S; Fedorov, B; O’Neill, K; Tolstoy, I. RefSeq microbial genomes database: new representation and annotation strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D553–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aizawa, J; Neuwirt, N; Barbato, L; Neves, PR; Leigue, L. Identification of fluoroquinolone-resistant extended-spectrum b-lactamase (CTX-M-8)-producing. Escherichia coli ST224, ST2179 and ST2308 in buffalo.

- Wang, M; Ma, M; Yu, L; He, K; Zhang, T; Feng, Y; et al. Characterization of IS26-bracketed blaCTX-M-65 resistance module on IncI1 and IncX1 plasmids in Escherichia coli ST224 isolated from a chicken in China. Vet Microbiol. 2025, 303, 110443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, JW; Bugata, V; Cortés-Cortés, G; Quevedo-Martínez, G; Camps, M. Mechanisms of Theta Plasmid Replication in Enterobacteria and Implications for Adaptation to Its Host. In EcoSal Plus; Slauch, JM, Phillips, G, Eds.; 2020; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giufrè, M; Errico, G; Accogli, M; Monaco, M; Villa, L; Distasi, MA; et al. Emergence of NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 167 clone in Italy. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 52, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, WY; Lv, LC; Pu, WX; Gao, GL; Zhuang, ZL; Lu, YY; et al. Characterization of an International High-Risk Escherichia coli ST410 Clone Coproducing NDM-5 and OXA-181 in a Food Market in China. Microbiol Spectr. 11, e04727-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwojiji, Esther Chigbaziru; Okolo, Ijeoma Onyinye; Osuji, Chigoziri Akudo; Aniokete, Ugonna Cassandra; Akomolafe, Sikiru Oladimeji; Okekeaji, Uchechukwu; et al. Molecular Detection of Ampicillinase blaEBCM, blaFOX and blaDHAM resistant genes in multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. GSC Biol Pharm Sci. 2025, 31, 113–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiemde, D; Ribeiro, I; Sanou, S; Coulibaly, B; Sie, A; Ouedraogo, AS; et al. Molecular characterization of beta-lactamase genes produced by community-acquired uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Nouna. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020, 14, 1274–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo, A; Ruiz-Larrea, F; Zarazaga, M; Alonso, A; Martinez, JL; Torres, C. Macrolide Resistance Genes in Enterococcus spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000, 44, 967–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).