1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is one of the most concerned public health problems [

1] due to Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), which increase morbidity and mortality worldwide [

2,

3,

4]

.

Antimicrobial-resistance Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), including carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and carbapenem-resistant organisms (CRO), such as carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii [

5] increase in their rate during the last ten years and cause the difficulty for choosing antibiotics available for treating them as WHO considered as a priority for developing new drugs [

6]

.

Carbapenem-resistant organisms containing the Carbapenemases hydrolyze many β-lactam antibiotics and confer significant antimicrobial resistance, such as the class A KPC enzyme in K. pneumoniae widely in the USA and some endemic parts of Europe, then the class B metallo-β-lactamases commonly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae family worldwide, finally class D OXA-type enzymes in A. baumanii and Enterobacteriaceaefamily worldwide, particularly in Europe and North Africa [

7]

.

The mechanisms of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria include the loss of porins, the presence of β-lactamases in the periplasmic space, an increase in expressing the transmembrane efflux pump, the presence of antibiotic-modifying enzymes, target site mutated and decreased the antibiotics binding to their site of action, ribosomal mutations or modifications, a mutation in the lipopolysaccharide. These mechanisms cause a decrease in the drug movement through the cell membrane, remove a drug from the bacterium, or make the antibiotics difficult to adhesive to their target, etc [

7].

Some studies showed one isolate producing two or more carbapenemases has increased [

8,

9]

. So, diagnosing and treating the infections due to this isolate becomes more difficult. The carbapenem-resistant genes appearing on mobile genetic elements allow for dissemination between Gram-negative species [

10].

CRE, belonging to Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), often resides in the gastrointestinal tracts of critically ill patients, being the source of spreading CRE for patients through healthcare activities of HCWs [

11,

12]. Next, many studies screened CRE carriage of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii in patients in ICUs, with culture of rectal swabs [

13,

14,

15], showed that risk factors of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative organisms, including CRE and CRO, are previous CRE/CRO colonization [

16], past antibiotic use (for example, Cephalosporins [

17], past carbapenem use [

18,

19], past mechanical ventilation use [

20], past intensive care unit stay, dialysis, past catheter insert, past long-term stay in hospital, comorbidities, intubation use [

21,

22].

In Vietnam, from 2007 to 2013, ten studies were performed in ICUs in hospitals participated in these studies. The prevalence of carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii increased from 69% (N= 170) to 89% (N = 167), as described in

Table 5: Epidemiology and prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in Vietnam [

23]

. The samples in these studies were collected from patients with infections in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of hospitals. So, these infections acquired in the hospitals were due to A. bamannii). Maybe, only a study of the community-acquired pulmonia (CAP) performed in three hospitals and three medical centers in Vinh Long province, South Vietnam, from April 2018 to May 2019, the prevalence of CAP caused by A. baumannii was 28.1 (N= 32) [

24]. Point prevalence survey at Vietnamese pediatric ICUs showed that the main risk factors for hospital-acquired infection included age less than seven months, intubation use, and infection detected at admission [

25].

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) significantly supports an outbreak investigator in determining the relatedness of isolates. It combines epidemiology data, such as hospital admission dates, past surgical operation history, and procedures performed on patients, to detect the transmission events that occurred or not in the activity of prevention and infection control [

26]

. WGS becomes a valuable tool for comprehending sources of infection and transmission routes of pathogens associated with healthcare activities. It can show which transmission sources are humans (HCWs or patients) or the hospital environment [

27].

However, there is no research on CROs in determining contamination and risk factors of CRO colonization in HCWs, residents (orphans) in a rural area, Cu Chi district at one Center of Care for and Protection of Disabled Orphan Children where residents (orphans) have spent their lives nearly during the rest of their lives because they were abandoned children since they were babies. Orphans have spent in this center for a long time. They have had many chances to contact other orphans and HCWs. So, the risk factors and contamination of CRO due to contact with healthcare activities for a long time can happen. For the reasons above, the objectives of this study were

1) To determine the prevalence of CRO colonization in HCWs, residents, and the environment,

2) To determine the CRO contamination/transmission between HCWs and residents,

3) To show the risk factors of CRO colonization in HCWs and residents in this center.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definitions

CRE: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae are resistant to carbapenems, regardless of mechanism (includes ESBL, AmpC, porins, and carbapenemase production).

CPE: Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae have a genetic element that codes for carbapenemase production (e.g., NDM, KPC).

CRO: Carbapenem-resistant organisms include all Gram-negative organisms and all resistance mechanisms.

CPO: Carbapenemase-producing organisms include all Gram-negative bacteria that produce a genetically coded carbapenemase [

28].

2.2. Design

A cross-section study was implemented in South Vietnam from September 2022 to May 2023 at The Care and Protection of Orphaned Children Center, whose area is about 2000 m2, including a building consisting of three floors in which the first and general floors are sections used as bedrooms and patient-care section. On the general floor, there is a section used for preparing food in the kitchen section. There is a small chicken and vegetable farming section to supply food for feeding patients, almost children, residing in this center because they are orphans.

The majority of children in this center have a disability related to cerebral palsy; many of the children have experienced complications of immobility and infection, are admitted to local hospitals, and are exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotics. This center has been operating since 2000 and caring for orphan children of the range of ages from 4 to 26 years old. So, in this study, we proposed the word of residents to replace the word of the orphans, who have lived at this center for two reasons: 1) the range of their age is from 4 to 26 years old, and 2) they have lived at this center since they were abandoned babies.

All 20 healthcare workers (HCWs) and 67 residents, (including children) participated in the study. We observed and determined 303 environmental samples in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children. But we randomly chose some samples in the environment, based on the Yamane formula [

29], was n = 175,

, Where n = sample size required (n =175), N = the total number of environmental samples was 307 (N) observed and determined in the center of care and protection of orphan children, e = 0.05, allowable error (%).

The number of randomly chosen environmental samples is present in Table 1 (Supplementary Tables)

This study received approval from the Board of Directors on Ethics in Biomedical Research at Thien Phuoc Nhan Ai Center of Care and Protection of Disabled Children, Vietnam, under the approval number 026/2565. The written consent forms were obtained from HCWs and the guardians of children.

Most of the residents at the center have a physical and (or) mental disability. The residents’ guardians participated in interviews to collect information. The HCWs at the Center are Catholic Sisters who provide nursing and personal care (wound care, bathing, feeding, etc.) in 8-10 hour shifts and six days a week. All residents and staff of the center participated in this study (20 HCWs and 67 residents (most of them were children).

Exclusion criteria included non-consent, known CRO/CPO colonization or infection during 6 months before the study, or active infection at the conducting study time. However, none of the residents or HCWs fulfilled any exclusion criteria. Hence, all participated in our study.

Residents and HCWs were allocated the participant codes, and isolates were allocated the laboratory codes for tracking.

2.3. Sample Collection

Instruments and method used for fecal collection:

Fecal collection: Tools used to collect specimens include sampling swabs and Amies Transport Medium.

The sampling swab is a method to take a sample. Then, we will transport it in Amies Transport Medium.

The procedure of fecal collection includes the following steps,

Open the swab package and remove a sampling swab tube from this package,

Then, hold the tube cap and remove a cotton swab stick inside. Only touch the cap,

Do not touch a cotton swab stick. Insert a sterile rectal cotton sampling swab approximately 1cm into the anal canal.

Then, rotate slowly for 10 seconds. Take the amount of feces collected on a cotton swab enough to perform the appropriate microbiological tests.

Next, put the rectal swab specimens into Amies Transport Medium.

Finally, these fecal specimens must be stored in a container with dry ice and transported to the Lab Department of Hung Vuong Hospital as soon as possible within 6 hours after collecting rectal swab specimens.

Environmental sample collection:

The tool used to collect the environmental samples is the environmental sampling swab,

Environmental samples are the samples collected from environmental surfaces and furnishings in the center, including the following steps,

Use the sterile rectal cotton sampling swab to collect the environmental sample.

An approximate area (10x10 (cm) was sampled on environmental surfaces and furnishings. After collecting samples, the swabs were placed in Amies Transport Medium and processed in the same way as for the rectal swabs.

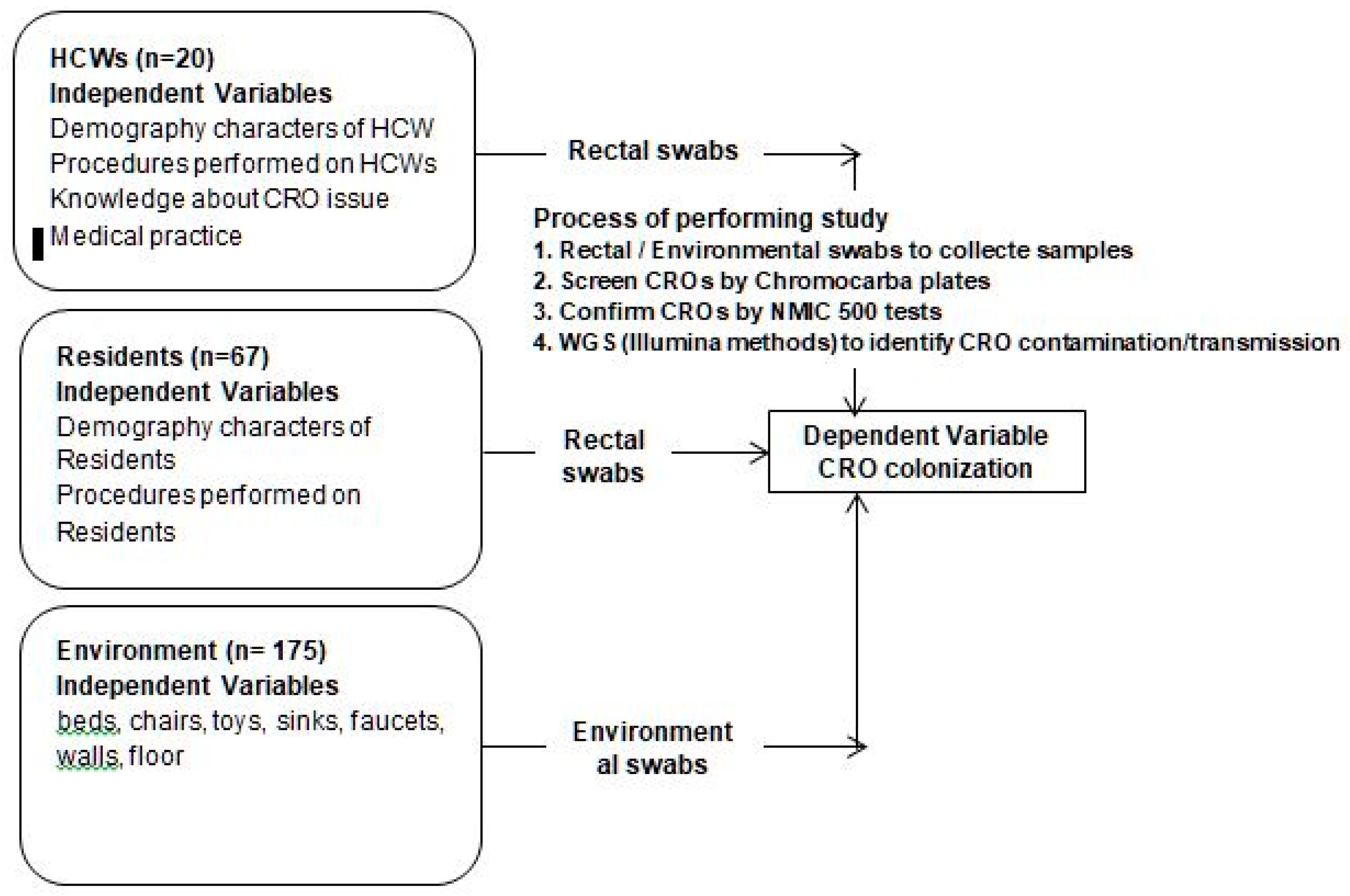

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework and process of screening, confirming and identifying CROs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework and process of screening, confirming and identifying CROs.

Demography characteristics of HCWs/residents are listed, such as age (years), previous antibiotic treatment, chronic disease, previous hospital stay, past surgical intervention, duration of treatment, and professional work (based on number of years and hours per day).

Procedures performed on HCWs/ residents: Peripheral IV catheter insertion, urinary catheter insertion

Knowledge/Attitude and behavior of HCWs in the prevention and control of CRO issues: A questionnaire list evaluates the knowledge/attitude of HCWs before and after training in the prevention and infection control and medical practice in the prevention and control of CRO colonization.

2.4. Microbiology Methods

The sample swabs were plated onto MELAB Chromogenic CARBA agar plates and incubated at 37o Celsius. Purity cultures of suspect colonies were performed on blood agar and species identification followed by Card NID, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and phenotypic carbapenemase detection using the NMIC-500 CPO Detect panel of the BD Phoenix TM Automated Microbiology System.

The reference strains in the NMIC 500 test to confirm susceptibilities are E. coli ATCC® 25922, K. pneumoniae ATCC BAA-1705™, and P. aeruginosa ATCC™ 27853.

2.5. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

We discovered thirty-six CRO isolates in HCWs, residents, and the environment. However, we chose twelve CROs detected from HCWs and residents who had close contact with HCWs: HCWs feed food or bath residents, etc.). CROs belonged to the same species with a high ratio of identical antibiotic-resistant phenotypes between CRO isolates and the number of CROs chosen to perform WGS available to our study financial resources. So, we selected twelve CRO isolates from HCWs and residents, as described in

Table 2, to determine whether the potential CRO transmission/contamination occurred between HCWs and residents in these chosen CROs. We extracted and measured DNA concentration in Vietnam. Next, we sent the samples to Charles River Laboratories in Australia for sequencing. The information on 12 CROs at Charles River Laboratories in Australia was presented in part (a) of

Table 2.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

After data were collected and cleaned, this data would be transferred to the SPSS software version 23.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the independent variables, including the characteristics related to demography in HCWs and residents, antibiotic use, treatment, medical procedures, length of hospital stay, number of hospital admission times related to CRO colonization, and chronic diseases, detected in HCWs and residents, determined the prevalence of CROs in HCWs, residents, and the environment, and risk factors associated with CRO colonization, and the adjusted odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was considered significant. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Process of performing whole genome sequencing for 12 randomly chosen CROs in 36 CROs detected in our study.

Table 2.

Process of performing whole genome sequencing for 12 randomly chosen CROs in 36 CROs detected in our study.

| Part (a): Information of 12 CROs sent to Charles River Laboratories |

| No |

Client ID |

Location of work/ residence |

Name CROs with BD identified in VN |

WGS code In Charles River Laboratories |

| 1 |

24 (C4 003) |

Floor 1 |

K.pneumonia |

6276063 |

| 2 |

193 (H 019) |

Floor 1 & General floor |

E.coli class B |

6276064 |

| 3 |

250 (H 006) |

Floor 1 |

E.coli class D |

6276065 |

| 4 |

251 (C4 003) |

Floor 1 |

E.coli class D |

6276066 |

| 5 |

256 (C3 002) |

General floor |

A. baumannii |

6276067 |

| 6 |

301 (H 008) |

Floor 1 |

Ent. cloacea |

6276068 |

| 7 |

391 (C2 012) |

Floor 1 |

A. baumannii |

6276069 |

| 8 |

403 (C3 022) |

Floor 1 |

A. baumannii |

6276070 |

| 9 |

413 (C3 011) |

Floor1 |

A. baumannii |

6276071 |

| 10 |

414 (C2 020) |

Floor 1 |

A. baumannii |

6276072 |

| 11 |

419 (H 009) |

Floor 1 |

A. baumannii |

6276073 |

| 12 |

H007 (H007) |

Floor 1 |

E.coli |

6276074 |

| H = Healthcare worker, C= Children. |

| Part (b): Genome assembly based species identification with WGS at Charles River Laboratories in Australia |

| Before WGS performance |

After WGS performance |

| No |

CROs confirmed ith BDAMS in VN |

WGS code |

Provisional Species did not changed before and after WGS |

| 1 |

K.pneumonia |

6276063 |

K. pneumoniae |

| 2 |

E.coli class B |

6276064 |

E.coli |

| 3 |

E.coli class D |

6276065 |

E.coli |

| 4 |

E.coli class D |

6276066 |

E.coli |

| 10 |

A. baumannii |

6276072 |

A. baumannii |

| 12 |

E.coli |

6276074 |

E.coli |

| 7 |

A. baumannii |

6276069 |

A. baumannii |

| No |

CROs confirmed ith BDAMS in VN |

WGS code |

Provisional Species changed after WGS |

| 5 |

A. baumannii |

6276067 |

A. seifertii |

| 6 |

Ent. cloacea |

6276068 |

E. cloacae/hormaechei |

| 8 |

A. baumannii |

6276070 |

Acinetobacter nosocomialis |

| 9 |

A. baumannii |

6276071 |

Acinetobacter nosocomialis |

| 11 |

A. baumannii |

6276073 |

A. baumannii/nosocomialis:k-mer graph shows possible mixture

|

| BD Phoenix TM Automated Microbiology System = BDAMS |

| Part (c): Genomic comparision and MALDI performancebased typing of five samples (6276067, 68, 70, 71,73) |

| No |

WGS code |

Name CROs with BDAMS |

Name CRO after WGS |

| 5 |

6276067 |

A. baumannii |

Acinetobacter seifertiI (sensu lato) |

| 6 |

6276068 |

Ent. cloacea |

Enterobacter cloacae/hormaechei (sensu lato) |

| 8 |

6276070 |

A. baumannii (sensu lato) |

Acinetobacter nosocomialis (sensu stricto) |

| 9 |

6276071 |

A. baumanni (sensu lato) |

Acinetobacter nosocomialis (sensu stricto) |

| 11 |

6276073 |

A. baumanni (sensu lato) |

Acinetobacter baumannii/nosocomialis(assembly shattered, possibly mixture)

|

Antibiograms of 12 CROs are shown in Table 3 (Supplementary Tables)

3. Results

3.1. Results of Whole Genome Sequencing of 12 CROs Analyzed at Charles River Laboratories in Australia

We sent 12 DNA samples for whole bacterial genome sequencing at Charles River Laboratories in Australia, where our team assembled and annotated the genomes to give provisional (sensu lato) species-level taxonomic classification, as shown in Part (b) in

Table 2, and done the assembly of genomes by using Unicycler v0.4.8 with default settings and minimum contig size of 300nt. We performed the annotation of genomes by using the RASTtk tool kit.

Continuously, we conducted genome sequencing for the 6276067, 6276068, 6276070, 6276071, and 6276073_sample because

1) There might be some infections due to transmission/contamination events within an orphanage

2) Antibiotic profiling of these isolates demonstrated high resistance.

So, determining the source of this resistance is a crucial issue in our study.

In detail, we used 25 antibiotics to determine the susceptibility or resistance of CROs in our research, as described in Table 3 (SupplementaryTables)

So, we showed the ratios of identical antibiotic-resistant phenotypes of the isolates with the same species below.

The ratios of identical antibiotic-resistant phenotypes

▪ between E. coli of C4003 (6276066) and H006 (6276065),

▪ between A. baumannii of C3022 (6276070) and H009 (6276073),

▪ between A. baumannii of C3011 (6276071) and H009 (6276073) and

▪ between A. baumannii of C3022 (6276070) and C3011 (6276071)

were 80% (20/25), 92% (23/25), 92% (23/25), and 100% (25/25), respectively.

3.2. Transmission/Contamination Tracking by SNP (Single Nucleotide Polymorphism) Count

3.2.1. Transmission/Contamination Between the Isolates, Including 6276070, 6276071 and 6276073_isolate

Firstly, we compared the genomics and performed the MALDI-based typing of five samples (6276067, 6276068, 6276070, 6276071, and 6276073_isolate). The results after performing the WGS for five isolates, as described in Part (c) of

Table 2,

Secondly, we tracked transmission of the same species, including the 6276067, 6276069, 6276070, 6276071, 6276072, and 6276073_sample, by counting SNPs between samples using the Snippy 4.6.0 and an Acinetobacter nosocomialis M2 reference genome (GCF_005281455.1_ASM528145v1). The number of genomes of Acinetobacter spp, including A. nosocomialis, is approximately 3,940,614.

The WGS results showed that the number of SNPs different between Acinetobacter isolates included from the 6276067_isolate to the 6276073_isolate

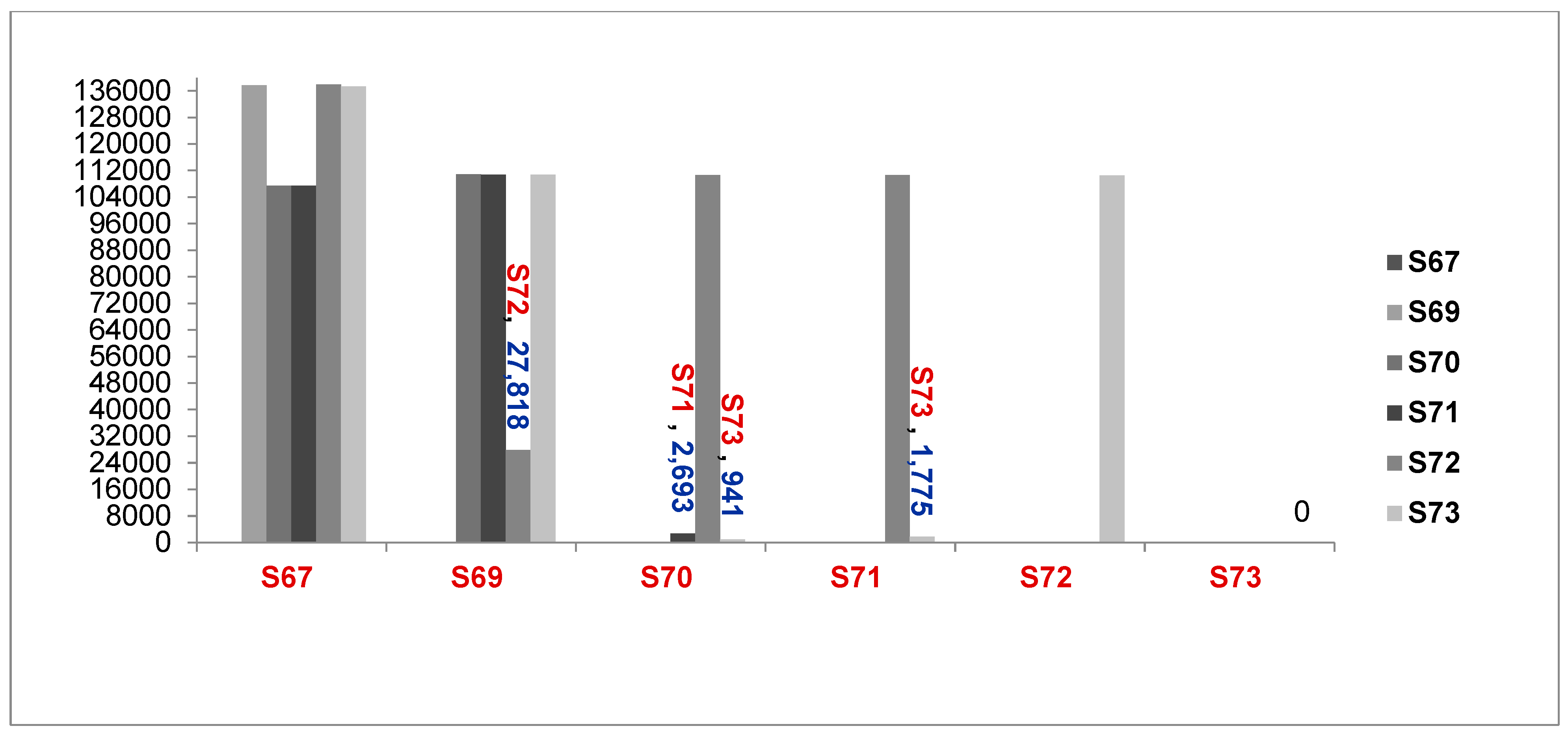

as described in Figure 2,

Figure 2.

: Comparison of Number of Genomes different between samples ( S67 to S73, A baumannii and A.seifertii) (6276067 = S67, 6276069 = S69, 6276070 = S70, 6276071 = S71, 6276072 = S72, 6276073 = S73, A. seifertii, A. baumannii).

Figure 2.

: Comparison of Number of Genomes different between samples ( S67 to S73, A baumannii and A.seifertii) (6276067 = S67, 6276069 = S69, 6276070 = S70, 6276071 = S71, 6276072 = S72, 6276073 = S73, A. seifertii, A. baumannii).

Following Lee's Study, when the ratio of ANI (average nucleotide identity) of two or more strains with the same species is over > 95%, two or more species belong to an identical clone [

30] . The results in Part (a) of

Table 4 showed the ratio of genome difference of each pair of isolates of the same species was less than 5%, as the standard level to confirm two isolates of the same species belong to an identical strain.

These results in Part (a) of

Table 4 confirmed that the 6276067_isolate is A. seifertii, the 6276069_isolate is A. baumannii, the 6276072_isolate is A. baumannii, and 6276073, 6276071, and 6276070_isolate are identical clones. (6276073_isolate = H009, 6276071_isolate = C3011, and 6276070_isolate = C3022). The result presented in Part (a) of

Table 4 showed that 6276070, 6276071, and 6276073 were closely related between a healthcare worker (H009) and residents (children) (C3022 and C3011) by a contamination event.

Table 4.

Determination of contamination/transmission with SNPs and OrthoANI values from S67 to S73_isolate.

Table 4.

Determination of contamination/transmission with SNPs and OrthoANI values from S67 to S73_isolate.

| Part ( a): The results of determining the contamination/transmission from 6276067 to 6276073_isolate) by |

| |

N of genomes of A. nosocomialis (1) |

N of genome different between (2) |

Ratio of genome different (%): (2) /( 1)

|

Ratio of genome difference of two isolates of the same species (%) |

Results |

| A. seifertii and S67 |

3,940,614 |

42246 |

1.07% |

< 5.00% |

S67 is A. seifertii |

|

A. baumannii and S69

|

3,940,614 |

28,554 |

0.72% |

< 5.00% |

S69 is A. baumannii |

| S69 and S72 |

3,940,614 |

27,818 |

0.71% |

< 5.00% |

S72 is A. baumannii |

| S71 and S70 |

3,940,614 |

2,693 |

0.07% |

< 5.00% |

S73, S71, and S70 belong to an identical clone |

| S73 and S70 |

3940614 |

941 |

0.02% |

< 5.00% |

| S73 and S71 |

3940614 |

1,775 |

0.05% |

< 5.00% |

|

S67 = 6276067_isolate, S69 = 6276069_isolate, S70 = 6276070_isolate, S71 = 6276071_isolate, S72 = 6276072_Isolate, S73 = 6276073_isolate |

| Part (b) : ANI matrix of isolates and 2 public reference genomes (A. nosocomialis, A. seifertii) |

| OrthoANI values calculated from the OAT software [30] |

S70_ |

S71_ |

S73_ |

A. nosocomialis |

A. seifertii |

|

asm(C3022)

|

asm(C3011)

|

asm(H009)

|

| S70_asm |

|

|

|

|

|

| S71_asm |

97.6561 |

|

|

|

|

| S73_asm |

98.8262 |

99.347 |

|

|

|

| A. nosocomialis |

97.6676 |

97.4891 |

97.8075 |

|

|

| A. seifertii |

91.9344 |

91.8987 |

91.9274 |

92.2549 |

|

| A. baumanii |

91.5521 |

91.5963 |

91.4095 |

91.363 |

89.7719 |

To improve the taxonomic accuracy of the Acinetobacter sp. samples typing of three isolates, including the 6276071, 6276070, and 6276073_isolate, we calculated the ratio of average nucleotide identity (ANI) of these three isolates by using OrthoANI.

The ratios of ANI between 6276070, 6276071, 6276073_isolate, and A. nosocomialis were over 95% (30), as described in Part (b) of

Table 4. In contrast, the ratios of ANI between 6276070, 6276071, and 6276073_isolate, compared with A. seifertii and A. baumannii, were less than 95%. So, the 6276070, 6276071, and 6276073_isolate were A. nosocomialis sensu stricto as the ANI is over 95% [

30] and belonged to an identical clone. Thus, the 6276070 (C3022), 6276071 (C3011), and 6276073 (H009) were associated with a contamination/ transmission event.

Part (b) of

Table 4 showed that the 6276073_isolate (H009), which had the ratio of genomes identical compared with the 6276071_isolate (C3011), was 99.347%, and compared to the 6276070_isolate (C3022) was 98.8262%. It meant that the 6276073_isolate (H009) was identical to the 6276071_isolate (C3011) and the highest identical to the 6276070_isolate (C3022) in the content of their genomes.

3.2.2. Transmission/Contamination Between the Isolates, Including 6276065, 6276066 Isolate

To determine the transmission/contamination of two E. coli isolates belonging to the 6276065 (H006)_isolate and 6276066 (C4003)_isolate, we selected more random outgroups of Escherichia coli (FORC_044 and strain_2313) and K12 used as the reference genome for SNP calling. All strains, including the 6276064, 6276065, 6276066, 6276074_isolate, FORC_044, and 2313_strain, have from 40,000 to 80,000 different SNPs pairwise between any two genomes. Hence, they are unrelated isolates.

Next, two isolates (6276065 (H006) and 6276066 (C4003)) had only 16 different SNPs, and the number of genomes of E.coli is about 4,608,319 genomes. Hence, the SNP difference between 6276065 and 6276066 was 0.0003% (16/4,608,319). As a result, the ratio of the genomic identity between 6276065 and 6276066 was 99.9997% (100% - 0.00034%). This result is evidence of a cross-contamination event between H006 and C4003.

The results of WGS showed there was clear evidence of transmissions/contaminations

1) between the 6276070 (C3022), 6276071 (C3011), and 6276073 (H009)_isolate, and

2) between the 6276065 (H006) and 6276066 (C4003)_isolate.

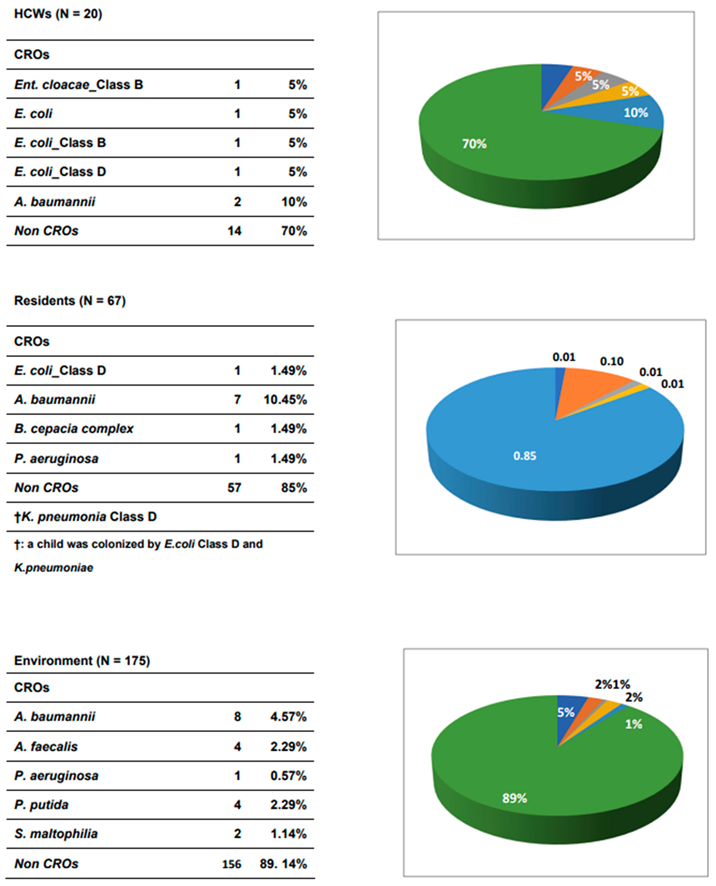

3.3. Prevalence of CROs in HCWs, Residents and Environment

Of 262 samples, including 87 rectal swabs (20 HCWs and 67 residents (most were children) and 175 environmental samples investigated, 36 CROs (i.e., six isolates of CREs and thirty isolates of non-CREs) were detected and successfully isolated in our study. Among 100 rectal swab samples, the detection rates of CROs were 30.0% (6/20) and 16.4% (11/67) found in HCWs and orphan patients, respectively.

In HCWs, four CREs, including three isolates of E. coli (15%, 3/20) and one isolate of E. cloacae (5%, 1/20), were detected, while the two isolates of A. baumannii (10%, 2/20) were identified in the HCWs, as shown in

Table 5.

In residents, 11 CRO isolates, in which a resident (child) was colonized, with 2 CREs (1 E. coli class D and 1 K. pneumoniae), were identified in residents as 1.49% (1/67) in E. coli class D, and K. pneumoniae, 10.45% (7/67) in A. baumannii), 1.49% (1/67) in B. cepacia complex, and 1.49% (1/67) in P. aeruginosa, respectively. So, the prevalence of CROs in residents was 14.93% (10/67)

In addition, 19 CRO isolates (10.9%, 19/175), including 4.57%, (8/175) in A. baumannii, 2.29%, (4/175) in A. faecalis, 0.57%, (1/175) in P. aeruginosa, 2.29%, (4/175) in P. putida and 1.14%, (2/175) in S. maltophilia, were identified in environmental samples.

Table 5.

Prevalence of Carbapenem resistant organisms in Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Childen.

Table 5.

Prevalence of Carbapenem resistant organisms in Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Childen.

3.4. Characteristics (Demographics) of Independent Variables Associated with HCWs and Residents

3.4.1. Demography Characters of HCWs and Residents

The HCWs and residents who participated in this study were 87 (N1=20 HCWs and N2=67 residents). Almost all HCWs were female 100%, while the prevalence of female residents was 26.9 %.

For age, an independent variable, the age range of HCWs was from 20 to 66 years old (Max = 66, Min = 20). The maximum age of the residents was 26 years old. But almost all HCWs were over or equal to 27 years old, and only one case was 20 years old.

The professions of HCWs included child carer (n=12, 60%), food provider (2, 10%), registered nurse (2, 10%), pharmacist (1, 5%), and other professions.

The proportion of HCWs with a duration of years for professional work under five years was 50%, and 50% of HCWs have worked for more than five years, while more than 67% of residents have resided for over five years in the Center of Care and protection Of Orphan Children. This result implied that HCWs and residents have lived, worked, and had many opportunities in close contact for a long time.

100% of HCWs have worked seven days per week, and 90% worked over 8 hours per day. This remarkable finding showed that HCWs had much time to contact residents in performing healthcare practice for residents in this healthcare setting. Thus, CRO transmission happens, such as an evitable event, while HCWs care for and treat patients at this center, as shown in Part (a) in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

| Part (a) Demography characteristics of HCWs and residents |

| 1. Sex |

|

|

|

2. Age (years) |

|

3. Occu |

|

4. Seven days for work p WK |

| |

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

| |

N,20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N,20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N,20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N,20 |

N, 67 |

| |

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

| Female |

20 (100) |

18 (26.9) |

|

≥ 27 yrs old is cut-point |

|

Cc |

12 (60) |

0 |

|

|

20 (100) |

4 (6) |

| Male |

0 (0) |

49 (73.1) |

|

Min / Max of age |

20.00 / 66.00 |

4.00/ 26.00 |

|

Cln |

1 (5) |

0 |

|

6. N of hrs for PW or W per Day |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FP |

2 (10) |

0 |

|

0 |

|

63 (94.0) |

| 5. Drt of PW/ Rsd (years) |

|

≤20 |

1 (5.) |

62 (92.5) |

|

Gd |

1 (5) |

0 |

|

0.5 |

|

3 (4.5) |

| < 5 yrs |

10 (50) |

22 (32.84) |

|

> 20 |

4 (20) |

5 (7.5) |

|

Mgr of Ct |

1 (5) |

0 |

|

4 |

|

1 (1.5) |

| > 5 |

3 (15) |

37 (55.22) |

|

> 30. |

5 (25) |

|

|

Pharm |

1 (5) |

0 |

|

7 |

2 (10) |

|

| > 10 |

7 (35) |

8 (11.94) |

|

> 40 |

10 (50) |

|

|

RN |

2 (10) |

0 |

|

8 |

10 (50) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No_OCCU |

|

67(100) |

|

10 |

8 (40) |

|

3.4.2. Demography Characters of HCWs and Residents Related to Antibiotic Use

In many studies, the trend of antibiotic overuse to treat bacterial infections induced bacteria resistance to antibiotics and disseminated the strains of resistant bacteria [

31,

32] (31,32). Previous studies showed that the more antibiotic use was, the more likely infection with CROs is [

33,

34].

When comparing the antibiotic use between HCWs and orphans, we recognized that HCWs used antibiotics more significantly than residents (χ2 = 31.0743., P < 0.0001, OR = 23.028571 (95% CI: 6.314, 83.996)), as shown in

Section 7, part (b) of Table 6 Next, the number of antibiotic-use times for the last time before the study participation in HCWs from 1 to 10 was 65% (13/20). In contrast, residents only used antibiotics, from 1 to 2 times with 7.5% (5/67), as described in Section 8, part (b) in Table 6.

Moreover, the duration of last antibiotic use by HCWs was from 14 to 180 days, away from the date of study participation, with 65% (13/20) of HCWs using antibiotics. Most were from 14 to 120 days, with 60% of HCWs (12/20), while the duration of last antibiotic use by residents was from 14 to 90 days, away from the date of study participation, with 7.5% (5/67) of patients using the antibiotics, as shown in Section 10, part (b) in Table 6. It implied that the trend of antibiotic use and the duration of antibiotic use and times for using antibiotics around one year before participating in the research in HCWs were more remarkable than in residents.

Specifically, in our study result, the first antibiotics were amoxicillin plus clavulanate acid or amoxicillin for HCWs. Contrarily, amoxicillin/clavulanate acid and azithromycin were for residents. There was an outstanding difference in the number of antibiotic-use days and the proportion of HCWs and residents using antibiotics to treat infectious diseases (ID) for the first time.

The total number of days of antibiotic use for the first time in HCWs was 75 days compared with 25 days in residents. The number of HCWs using antibiotics from 2 to 30 days was 13 (55%), while that of residents using antibiotics was 5 (7.46%), as shown in Section 11, part (b) in Table 6.

Next, HCWs didn’t use antibiotics for the second time, but in residents, three cases used antibiotics for five days for each one with 4.48% (3/67), as described in Section 12, part (b) of

Table 5. When we compared two proportions of no using antibiotics between HCWs and residents, there was no difference in no using antibiotics the second time between HCWs, with 100% (20/20), and orphan children, with 95.52% (64/67), as shown in Section 12, part (b) in Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

| Part (b): Demography characteristics of HCWs and orphan patients to antibiotic use |

| 7. ABU |

|

9. N of Ds of ABU for LT BEF St part |

|

10. LABU, HL, ago (ds): |

| |

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

| |

N,20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N,20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N,20 |

N, 67 |

| |

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

| Yes |

13 ( 65) |

5 (7.46) |

|

0 |

7 (35) |

62 (92.5) |

|

0 (day) |

7 (35) |

62 (92.50) |

| No |

7(35) |

62 (92.5) |

|

1 |

2 (10) |

|

|

14 |

3 (15) |

1(1.50) |

| 8. N of Ts for ABU in LY (times) |

|

2 to 4 |

4 (20) |

|

|

30 |

3 (15) |

1(1.50) |

| 0 |

7 (35) |

62 (92.5) |

|

5 |

4(20) |

4 (6.0) |

|

60 |

|

2 3.00) |

| 1 to 2 |

5 (25) |

5 (7.5) |

|

6 to 7 |

2 (10) |

|

|

90 |

3 (15) |

1 (1.50) |

| 3 to 4 |

5 (25) |

|

|

10 |

|

1 (1.5) |

|

120 |

3 (15) |

|

| 8 to 10 |

3 (15) |

|

|

30 |

1 (5) |

|

|

180 |

1 (5) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| 11. N of ds for 1st ABU days) |

|

12. N of days for 2nd ABU |

|

13. List of AB used for 1st time to treat IDs |

| 2 to 4 |

4 (20) |

|

|

No_Use |

19 (95) |

63 (94.03) |

|

AMC (2:1) |

2 (10) |

1 (1.49) |

| 5 |

4 (20) |

5 (7.46) |

|

Not RMR |

1 (5) |

1 (1.49) |

|

AMC (2:1) |

3 (15) |

AMC, 1 (1.49) |

| 6 to 7 |

2 (10) |

|

|

Use |

0 |

5 days , 3 (4.48) |

|

AMOX |

1 (5) |

AZI, 250 mg: 2 (2.99) |

| 30 |

1 (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

No use |

7 (35) |

62 (92.54) |

| 0 day |

7 (35) |

62 92.53) |

|

14. List of AB used for 2nd time to treat IDs |

|

Not RMB |

7(35) |

AZI, 500 mg: 1 (1.49) |

| not RMR |

2 (10) |

|

|

No (Use & RMB) |

20 (100) |

64(95.52) |

|

|

|

|

| T of ds for ABU |

75 |

25 |

|

ABU |

|

CPN, 250:, 3 (4.48) |

|

|

|

|

3.4.3. Demography Characters of HCWs and Residents Related to Length of Hospital Stay, Number of Hospital Admission Times

The factors that influenced the appearance of multi-drug resistant organisms (for example, Carbapenemase-resistant organisms, CRO) were the number of admission times and the length of hospital stay, as reported in the previous studies [

35,

36].

Hence, the characteristics should be analyzed as follows: the number of times and days, reasons for hospital admission, duration of the last hospital stay out, or in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children, we recognized that the number of past hospital-admission times outside of Center in HCWs was one time with 15% (3/20), as shown in Section 15, part (c) of Table 6, but, that in residents was from 1 to many times, with 16.4% (11/67), as described in Section 15, part (c) of Table 6. The reasons for hospital admission in HCWs outside of the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children were knee ligament tear, laryngeal fibroids, and pneumonia, with one case for each reason, as shown in Section 16, part (c) of Table 6. However, one case of sacral decubitus ulcer was the reason for the residents. The duration of the last hospitalization outside the orphanage care and protection center before participating in the study was from 60 to 365 days, occupied by 15% of cases (3/20) in HCWs, while that in residents was 10 days, occupied 1.49% of cases (1/67), as shown in Section 17, part (c) of Table 6, and the number of days for last admission at hospitals outside the Center of Care and protection of Orphaned Children, in HCWs from 4 to 5 days, occupied by 15% (3/20), while that in residents for ten days was 1.5% (1/67), as shown in Section 18, part (c) of Table 6.

The characteristics associated with chronic diseases were critically different between HCWs and residents, with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 8.1614, p = .004279, OR = 0.2144 (0.0708 to 0.6493). This result suggested cases of chronic diseases in residents more than in HCWs. It also suggested chronic diseases in HCWs, including chronic tonsillitis, laryngeal fibroids, and laryngitis, were distinctive to most chronic diseases in residents: mental and physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, epilepsy, Down syndrome, speech impairment, and hyperactivity, as described in Part (d) of Table 6.

Some studies showed that children with cerebral palsy have often experienced a severe neurological impairment associated with a motor impairment. So, these children have not performed daily activities such as eating some food, drinking water, and maintaining personal hygiene [

37] This children group was particularly susceptible to lower respiratory infection [

37,

38] caused by multi-drug MDROs, including CPO (P. aeruginosa [

39].

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use,treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

| Part (c): Characteristics related to treat HCWs and residents in and out of the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children Care |

| 15. N of HA Os of C of C & P of OC |

|

16. Rs for HA Os of C of C & P of OC |

17. LHA Os of C of C & P of OC, HL ago (Ds) |

| |

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

|

H |

Rsd |

| N,20) |

N, 67 |

N,20) |

N, 67 |

N,20) |

N, 67 |

| |

n, % |

(n, %) |

|

|

n, % |

(n, %) |

|

n, % |

(n, %) |

| No_Ad |

17 (85) |

56 (83.6) |

|

KLT |

1 (5) |

|

10 |

|

1 (1.49) |

| 1 |

3 (15) |

3 (4.5) |

|

LF |

1 (5) |

|

60 |

1 (5) |

|

| 2 to 3 |

|

5 (7.5) |

|

PNA |

1 (5) |

|

120 |

1 (5) |

|

| Many times |

|

3 (4.5) |

|

SDU |

|

1 (1.49) |

365 |

1 (5) |

|

| |

|

|

|

No_Ad |

17 (85) |

66 (98.51) |

No_Ad |

17 (85) |

66 (98.50) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 18. N of Ds for L HA Os of C of C & P of OC |

|

20..LHA at C of C & P of OC, HL ago (Ds) |

21. Reas for ADM at C of C & P of OC |

| 0 days |

17 (85) |

66 (98.5) |

|

10:00 |

|

3 (4.5) |

Epilepsy |

|

3 (4.5) |

| 4 |

1(5) |

|

|

14 |

|

1 (1.5) |

Flu: |

|

1 (1.5) |

| 5 |

2 (10) |

|

|

30 |

|

3 (4.5) |

PNA |

|

3 (4.5) |

| 10 |

|

1 (1.5) |

|

60 |

|

2 (3.0) |

SDU |

|

1 (1.5) |

| 19. chronic diseases |

|

90 |

|

1 (1.5) |

SF |

|

1 (1.5) |

| Yes |

11 (55) |

57 (85.1) |

|

120 |

|

1 (1.5) |

Sinusitis |

|

1 (1.5) |

| NL |

9 (45) |

10 (14.9) |

|

No HA |

20 (100) |

56 (83.6) |

No_Reas |

20 (100) |

57 (85) |

| N of HA Os of C of C & P of OC = Number of Hospital admission out side of center of C & P of OC, N of AT Os of C & P of OC Ly Bef study = Number of admission times outside of C of C & P of OC last year, before performed study, Rs for HA Os of C of C & P of OC = Reason for hospital admission outside of C of C & P of OC, LHA Os of C of C & P of OC, HL ago (Ds) = Last hospital admission outside of C of C & P of OC, How long ago (days), N of Ds for L HA Os of C of C & P of OC = Number of days for last admission at hospitals outside of C of C & P of OC, LHA at C of C & P of OC, HL ago (Ds) = Last hospital admission at C of C & P of OC, How long ago, Reas for ADM at C of C & P of OC = Reasons for admission at Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children. |

| Part (d) Characteristics related to chronic diseases in HCWs and residents |

| |

H |

|

|

Rsd |

|

|

Rsd |

| |

N, 20 |

|

|

N,67 |

|

|

N, 67 |

| |

n (%) |

|

|

n (%) |

|

|

n (%) |

| NL |

10 (50) |

|

NL |

10(14.9) |

|

HPA + SI: |

1 (1.5) |

| CTS |

2 (10) |

|

AT |

1(1.5) |

|

HR + SI: |

2 (3.00) |

| DM |

1 (5) |

|

CP |

27(40.3) |

|

Ment. Retard |

2 (3.0) |

| HND |

1 (5) |

|

CP+ VI |

1(1.5) |

|

OI |

2 (3.0) |

| ELE |

1 (5) |

|

CP+ ELS |

2 (3.0) |

|

ELS |

5(7.50) |

| HTN |

1 (5) |

|

DS |

6 (9.00) |

|

ELS+ SZR |

1(1.50) |

| LF |

1 (5) |

|

DS + SI |

2 (3.0) |

|

ELS+ ID |

1 (1.5) |

| LRG |

1 (5) |

|

ID |

1(1.5) |

|

|

|

| SD |

1 (5) |

|

HC |

1 (1.5) |

|

|

|

| SDH |

1 (5) |

|

HPA |

2(3.0) |

|

|

|

3.4.4. Demography Characters of HCWs and Children Related to Procedures Performed on HCWs and Residents

The other factors associated with CRO colonization or infection were the procedures performed in the past, such as past operations, the number of times for past operations, the duration of past operations [

40]

, and invasive urinary or intravenous catheter use [

41,

42] .

The proportions of past operations before participating in the study in HCWs and residents were 5% (N=20) and 1.50% (N=67), respectively, as described in Section 22, part (e) of Table 6. Similarly, the number of times for past operations last year before participating in the study in HCWs and residents were 5% (N=20) and 1.50% (N=67), respectively, as shown in Section 23, part (e) of Table 6.

The proportions of peripheral intra_catheter use before participating in the study of HCWs and residents were 10% (N=20) and 1.50% (N=67), as presented in Section 25, part (e) in Table 6. The remarkable thing was the urinary catheter procedure without indication for HCWs and residents in our study. The number of days of using the peripheral intra_catheter in HCWs was from 1 to 5 days, with 2 cases (10%), but in residents for 10 days, with 1 case (1.50%), as shown in Section 26, part (e) in Table 6. The urinary catheter use was not performed on HCWs and children, as reported in Section 27, part (e) of Table 6.

The number of times for past operations, the number of days, and times of peripheral intra_catheter and urinary catheter use occupied proportions no more than 10 % for all characteristics of medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents, as shown in part (e) of Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use, treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

Table 6.

Characteristics related to Demography, antibiotic use, treatment and medical procedures performed on HCWs and residents.

| Part (e): Characteristics related to procedures performed on HCWs and Children |

| 22. Past operation before participating in study |

|

24. Last operation before participating study, How long ago |

|

26. Number of days for periperal intra_catheter use before participating study |

| |

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

|

|

H |

Rsd |

| |

N, 20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N, 20 |

N, 67 |

|

|

N, 20 |

N, 67 |

| |

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

|

|

n, % |

n, % |

| |

|

|

|

0 (yrs) |

18 (90) |

66 (98.5) |

|

0 day |

18 (90) |

66 (98.50) |

| Yes |

1 (5) |

1 (1.50) |

|

1 |

2 (10) |

|

|

1 |

1 (5) |

1 (1.50) |

| No |

19 (95) |

66 (98.5) |

|

6 |

|

1(1.50) |

|

5 |

1 (5) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 23. Number of times for past operations last year before participating study |

|

25. Use of periperal intra_catheter before participating study |

|

27. Urinary catheter use before participating study |

| 0 time |

19 (95) |

66 (98.5) |

|

Yes |

2 (10) |

1 (1.50) |

|

No use |

20 (100) |

67 (100) |

| 1 |

1 (5) |

1 (1.50) |

|

No |

18 (90) |

66 (98.5) |

|

|

|

|

3.5. Risk Factors Associated with CROs in HCWs and Residents

From the results of the WGS of 12 CROs, we showed crucial data, including,

1. CRO transmission events between HCWs and residents: one case of E.coli transmission was between an HCW (H006) and one resident, a child (C4003), and another case of A. nosocomialis transmission between an HCW (H009), and two residents (C3022 and (C3011), who were children.

2. In 12 CRO isolates detected in 11 participants, 2 CROs, one E.coli, and one K pneumonia isolate, were found in a child (C4003).

3. 11 participants included five HCWs: H006, H007, H008 and H009 working in the first floor, and H019 working in both the General and first floor. Of six residents, five resided on the first floor, and one (C3002) on the General floor, as described in

Table 2, and 6. HCWs participating in performing the WGS were the child carers in Table 3 (Supplementary Table).

5. The age of all residents was below 27 years old.

6. Residents have lived together in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children for a long time. So, residents have spent a long duration in close contact between themselves and between them and HCWs.

To determine risk factors associated with CRO colonization, we based on crucial data:

1. The study group included 87 participants, including 20 HCWs and 67 residents, linked in a unity group. It meant the risk factors only occurred when HCWs and residents have worked, resided, and contacted for a long time in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children.

2. The risk factors linked to CRO colonization happened due to two or many characters activating together (for example, age more than 27 years old and working or residing in the Center more than four years, etc...

3. The 27-year-old level is a crucial cutting point to divide the 87 participant group into two sub-groups: one belongs to the HCW group, and another belongs to residents.

3.5.1. Risk Factors Associated with CROs in a Group, Including HCWs and Residents

Based on crucial data analyzed above, we detected in the group of 87, CRO colonization was not significantly different between HCWs (20) and residents (67), between HCWs more than 27 years old compared with the rest of the 87 participants, between HCWs more than 27 years old and using antibiotics compared with the rest of 87 participants, as shown in

Section 1, 2, 3 in Table 6. However, the CRO colonization in HCWs more than 27 years old and working on the first floor was significantly different compared to residents, with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 7.522, p =0.006, OR = 6.000 (1.488 to 24.192), as shown in

Section 4 in Table 6.

Next, HCWs being more than 27 years old have worked for more than four years in professional work or worked for more than one year at the first floor or worked for more than four years and more than eight hours for healthcare activity per day at the Center of Orphaned Children, have risk factors colonized with CROs significantly with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 5.025, p = .025, OR = 4.156 (1.117 to 15.462), χ2 (1, N = 87) = 7.522, p = 0.006, OR = 6 (1.488 to 24.192), and χ2 (1, N = 87) = 5.025, p = 0.025, OR = 4.156 (1.117 to 15.462), respectively, as shown in

Section 5, 7, 8 in Table 6.

Especially, as described in

Section 3, part (a) of Table 6, and

Section 6 of

Table 7, Childcarers (n=12) had the risk colonized with CROs significantly, compared with the rest of the participants in our study, with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 5.025, p = 0.025, OR = 4.156 (1.117 to 15.462).

Moreover, in our study, we detected that childcarers who have worked for more than two years at the Center consumed antibiotics more than two times and more than four days each time to treat infectious disease in last time before participating in our study had the risk of colonized with CROs with 6.071 compared with the remaining group, with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 9.084, p = 0.003, OR = 6.071 (3.762 to 9.800), as described in Section 11 in

Table 7.

In particular, we discovered in the group of 79 participants, including 67 residents and 12 childcarers who have worked more than four years at the Center, consumed the antibiotics more than two times and more than four days each time last time to treat the infectious disease before participating in our study had risk colonized with CRO significantly with χ2 (1, N = 87) = 8.755, p = 0.003, OR = 5.923 (3.608 to 9.723), compared with the remaining group, as shown in Section 12 in

Table 7.

The results shown in Sections 11 and 12 of

Table 7 determined that Childcarers had CRO contamination more than the rest of the participants.

Factors such as past operation, peripheral intra-catheter use, and urinary catheter use before participating in the study were not risk factors associated with CRO colonization in our study, as shown in Sections 9 and 10 of

Table 7.

So, the WGS is an effective tool in investigating, estimating, and determining the risk factors associated with CRO colonization and preventing and controlling contamination and transmission of CRO or multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings.

Table 7.

Risk factors related to CRO colonization detecetd in HCWs and children (N=87, HCWs, = 20, residents, =67).

Table 7.

Risk factors related to CRO colonization detecetd in HCWs and children (N=87, HCWs, = 20, residents, =67).

| HCWs + RESIDENTS = 87 |

CRO |

n_CROs |

Pearson χ2 |

P value |

Fisher's Exact Test (2-sided) |

OR |

95% CI |

| 1. HCWs (20) |

6 (3.7) |

14 (16.3) |

2.332a |

0.127 |

0.185 |

2.443 |

0.759 |

7.862 |

| /RESIDENTS (67) |

10 (12.3) |

57 (54.7) |

| 2. AGE ≥ 27 yrs |

6 (3.5) |

13 (15.5) |

2.817a |

0.093 |

0.106 |

2.677 |

0.825 |

8.689 |

| /Others |

10 (12.5) |

58 (55.5) |

| 3. AGE ≥ 27 yrs & ABU |

2 (2.2) |

10 (9.8) |

0.028 |

0.868 |

1 |

0.871 |

0.172 |

4.428 |

| /Others |

14 (13.8) |

61 (61.2) |

| 4. AGE ≥ 27 yrs & Work 1st floor |

5 (1.8) |

5 (8.2) |

7.522a |

0.006 |

0.016 |

6 |

1.488 |

24.192 |

| Others |

11 (14.2) |

66 (62.8) |

| 5. AGE ≥ 27 yrs & Work ≥ 4 years |

5 (2.2) |

7 (9.8) |

5.025a |

0.025 |

0.04 |

4.156 |

1.117 |

15.462 |

| Others |

11 (13.8) |

64 (61.2) |

| 6. Chidcarers |

5 (2.2) |

7 (9.8) |

5.025a |

0.025 |

0.04 |

4.156 |

1.117 |

15.462 |

| / Others |

11 (13.8) |

64 (61.2) |

| 7. Age ≥27,work ≥ 1 year, in floor 1 |

5 (1.8) / |

5 (8.2) / |

7.522a |

0.006 |

0.016 |

6 |

1.488 |

24.192 |

| / Others |

11 (14.2) |

66 (62.8) |

| 8. Age ≥27 years, work ≥ 4 years, work time ≥ 8 hours per day |

5 (2.2) / |

7 (9.8) / |

5.025a |

0.025 |

0.04 |

4.156 |

1.117 |

15.462 |

| / Others |

11 (13.8) |

64 (61.2) |

| 9. Past surgery before participating in study about one year |

1 (0.4) |

1 (1.6) |

1.363a |

0.243 |

0.336 |

4.667 |

0.276 |

78.869 |

| / no_past surgery |

15 (15.6) |

70 (69.4) |

| 10. Periperal intra_catheter use before participating study |

1 (0.4) |

1 (1.6) |

4.825a |

0.028 |

0.086 |

10 |

0.847 |

117.999 |

| / No_Periperal intra_catheter use |

15 (15.6) |

70 (69.4) |

| 11. Childcarers worked ≥2 years at Center, used AB ≥2 times and ≥4 days for each time in last time before particpating study |

2 (0.4) |

0 (1.6) |

9.084a |

0.003 |

0.032 |

6.071 |

3.762 |

9.800 (*) |

| / Others |

14 (15.6) |

71 (69.4) |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HCWs/ chilcarers = 12, Residents =67

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 12. Childcarers worked ≥ 4years at Center, used AB ≥2 times and ≥4 days for each time in last time before particpating study |

2 (0.4) |

0 (1.6) |

8.755a |

0.003 |

0.034 |

5.923 |

3.608 |

9.723 (**) |

| / Others, |

13 (14.6) |

64 (62.4) |

|

AB = Antibiotic,(*)(**) for cohort CRO = CRO

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.5.2. Risk Factors Associated with CROs in Two Different Groups, Including HCWs and Residents

HCWs and residents belonged to two separate groups, including one for 20 HCWs and another for 67 residents,

For HCWs, we can not analyze the risk factors associated with CRO colonization because the number of HCWs participating in our study was 20 HCWs, less than the standard sample size necessary for analyzing the risk factors, which was 30.

For residents, we detected one risk factor associated with CROs, such as the residents less than nine years old and & residing less than or equal to half and seven years in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children, was significantly different from the remaining group, with χ2 (1, N = 87) =6.385, p =0.012, OR = 7.714 (1.296 to 45.905), as shown in Section 13 of

Table 8.

Moreover, for antibiotic use and antibiotic use more than five days for the first time of infectious disease treatment, the group of residents less than nine years old and & residing in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children less than or equal to half and seven years had the risk of CRO colonization more than 6.7 and 6.2 times compared to the remaining group of residents, respectively, as shown in Section 15, 16 of

Table 8.

In particular, so impressively, the residents less than nine years old and & residing less than or equal to half and seven years, antibiotic use for the first time more than two times and more than five days for infectious disease treatment had the risk of CRO colonization more than 6.7 compared to the remaining group of residents, as described in Section 14 of

Table 8.

Similarly, as the risk factors of CRO colonization detected in the group of 87 participants (20 HCWs and 67 residents), the risk factors of CRO colonization detected in the group of 67 participants, based on the WGS results, were a combination of many factors, such as age, duration of residence in the Center of Orphan Children, location of professional work/residence, number of times and days of antibiotic use in the first time for infectious disease treatment. So, the risk factors shown above were an association of two or many demography and medical procedure characteristics in the group of 87 or 67 participants.

Table 8.

Risk factors related to CRO colonization detecetd in children (N=67).

Table 8.

Risk factors related to CRO colonization detecetd in children (N=67).

| Residents, N= 67 |

CRO |

n_CRO |

Pearson χ2 |

P value |

Fisher's Exact Test (2-sided) |

OR |

95% C.I |

| 13. Age < 9 years & resided in center <=7.5 years |

3 (9) |

3 (5.1) |

6.385a |

0.012 |

0.039 |

7.714 |

1.296 |

45.905 |

| / the remaining group |

7 (9.1) |

54 (51.9) |

| 14. Age < 9 years & resided in center <=7.5 years, Times of ABU ≥ 2, ABU in the first time >=5 days |

1 (0.1) |

0 (0.9) |

5.786a |

0.016 |

0.15 |

7.333 |

3.996 |

13.458 |

| / the remaining group |

9 (9.9) |

57 (56.1) |

| For cohort CRO = CRO |

|

|

|

|

|

6.778 |

1.395 |

32.922 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Residents, N= 67 |

ABU |

n_ABU |

Pearson χ2 |

P value |

Fisher's Exact Test (2-sided) |

OR |

95% C.I |

|

| 15. Age < 9 years & resided in center <=7.5 years |

2 (0.4) |

4 (5.6) |

6.387a |

0.011 |

0.06 |

9.667 |

1.237 |

75.554 |

| / the remaining group |

3 (4.6) |

58 (56.4) |

| For cohort = Antibiotic use (ABU) |

|

|

|

|

|

6.778 |

1.395 |

32.922 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Residents, N= 67 |

ABU≥ 5 days in 1st time for ID treatment |

ABU <5 in 1st time for ID treatment |

Pearson χ2 |

P value |

Fisher's Exact Test (2-sided) |

OR |

95% C.I |

|

| 16. Age < 9 years & resided in center <=7.5 years |

2 (0.4) |

3 (4.6) |

6.387a |

0.011 |

0.06 |

9.667 |

1.237 |

75.554 |

| / the remaining group |

4 (5.6) |

58 (56.4) |

| For cohort = ABU>=5 days for 1st time for ID treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

6.2 |

1.395 |

32.922 |

|

ID = Infectious disease |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

We detected evidence of CRO contamination or transmission between E.coli or A.nosocomialis in HCWs and residents with the WGS tool. It is the first evidence of CRO contamination/transmission between HCWs and residents in a healthcare setting in a remote local center in the Cu Chi district in Vietnam.

The previous studies in Vietnam did not show evidence of CRO colonization or transmission between HCWs and patients in the healthcare setting in Vietnam [

43]. Even the studies in other countries did not certainly prove that HCWs were a source of CRO transmission because there was no clear evidence to prove this problem [

44,

45,

46].

Our WGS results show CRO contamination/transmission in the Center for Care and Protection of Orphan Children. The origin of the problem could happen in caring for residents or might be due to cleaning the environment and even food processing. It was a potential issue in the community near the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children.

So, to prevent the CRO spread in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children, a hand hygiene program should be consolidated and prepared with alcohol-based hand-rub bottles at the sites appropriate for HCWs, residents, and even visitors contacting, for example, at the entrance of the resident rooms, reception room, kitchen, and the area for residents playing to be easy to contact and use this product to remove CRO colonization on the hands of HCWs and residents. The environment cleaning guide is a substantial priority in reducing the environmental CROs and preventing CRO spread in HCWs and residents who have lived in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children.

Next, we concerned the population in the community around the Care and Protection of Orphan Children Center, where CROs were found in HCWs, residents, and the environment and transmitted between HCWs and residents. Thus, investigating and evaluating the severe level of CRO colonization for both the prevalence and the level of spreading CRO colonization in the population living near the Center of Care and Protection is a top priority of managers in community and health at this local Government. Based on the WGS results and data related to 12 CROs, as described in

Table 2 (cont), performed with WGS, including characters, for example as the level of age more than or equal to 27 years old and working more than four years, or working more than one year, at the floor 1, or, working more than four years, and working more than 8 hours per day as described in

Table 7, were the valuable data to analyze risk factors associated with CRO colonization.

Firstly, we confirmed the WGS results were a significant guide to discovering the risk factors related to CRO colonization in a study group, including 20 HCWs, 67 children, and 27 years old, such as a particular cut point to divide this study group into a group belonging to HCWs with more than or equal to 27 years old and other group belonging to residents, as shown in

Table 7.

Second, when we separately analyzed the resident group to find the risk factors, we detected one factor related to CRO colonization in residents under nine years old and & residing less than or equal to half and seven years in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children. Another risk factor of CRO colonization was detected in residents who were less than 9 years old, resided in the center for less than 7.5 years, consumed antibiotics more than 2 times, and more than 5 days in the first time of antibiotic use, as shown in

Table 8.

This result suggested that antibiotic consumption and antibiotic consumption for more than five days were potentially related to CRO colonization in residents under nine years old and & residing less than or equal to half and seven years.

Based on the WGS tool in detecting risk factors, in the group of 87 participants (HCWs = 20, residents = 67) and another group (N=67 residents), we recognized that the risk factors analyzed in the group of 87 showed a relationship significant between residents and HCWs, who had the risk of CRO contamination/colonization more than residents. The risk factors of CRO contamination/colonization detected in the group of 87 participants are reasonable and available to the current medical practice at the Center of Care and Protection of Orphan Children and suggested a plan available and effective in preventing and controlling CRO contamination/colonization in current conditions of this center. The WGS is a beneficial tool in detecting CRO risk factors in our study.

Some studies detected the carriage rate of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing gram-negative bacteria (ESBLs) in HCWs in the ICUs [

47], and the prolonged care facilities [

48,

49] significantly changed from 3.5% to 21.4 %.

A study at the US National Institutes of Health Clinical Center from November 2013 to February 2015 showed that healthcare personnel (HCP) or microbiology laboratory staff had a history of regularly close patient contact, they would have a prevalence of ESBL colonization of 4% (15/ 379), higher than staff without frequent contact history with patients or bacterial specimens, with 2.9% (11/ 376). However, the difference between the prevalence of ESBL in HCWs and the control group was not statistically significant, with P = 0.55. There were no HCPs colonized with CROs. This result suggested that ESBL can reside on HCWs through close contact between HCWs and patients. It also implied that HCWs are "victims" of ESBL colonization during healthcare for ESBL colonized patients [

50].

In Vietnam, a prospective study investigated characteristics of antibiotic resistance of intestinal Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) detected in HCWs at the adult ICU at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases (HTD) for two months at the beginning of October 28, 2019. This study results showed that among 40 HCWs participating in this study, the prevalence of HCW carrying ESBL/AmpC β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli was 65% (26/40), and only one HCW colonized with Acinetobacter baumannii. The 25% of HCWs (N=40) were ESBL persistent and frequent carriers [

43]. Our study results showed that CRO colonization appeared at the remote Centers of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children, and multi-drug resistant organisms (MDROs), such as ESBL-producing organisms, were detected in HCWs in other studies, including the studies in Vietnam. So, it suggested that CRO colonization or multi-drug resistant organisms can appear in HCWs in Vietnam. So, an essential project should be conducted at the Central and Local Hospitals in Vietnam to screen and determine the prevalence and risk factors and CRO colonization in HCWs at hospitals and prevent CRO colonization/transmission between HCWs and children..

5. Conclusion

Our study showed that CROs appeared in HCWs, residents, and the environment in the Center of Care and Protection of Orphaned Children. Risk factors of CRO colonization detected in HCWs were associated with age of more than 27 years, professional working time of more than four years or working site at floor_1, and working time over or equal to 8 hours per day, etc. Moreover, CRO transmission can happen in our study because we detected CRE in an HCW and a child (E. coli) or CROs (A baumannii) in an HCW and two children. So, whole genome sequencing will be an effective and beneficial tool to determine CRO contamination/transmission and risk factors associated with CRO colonization. A hand hygiene program and a clear and effective plan will be the best choices to prevent and control CRO colonization/transmission in this center.

6. Limitation of Study

This study was performed at one center of care and protection in a local district in South Vietnam with 87 participants. So, the study results could show a part of the problem of CRO colonization/transmission in healthcare settings for Orphaned Children. However, it was the first time to detect CRO colonization and even CRO transmission in a healthcare setting in Vietnam. Then, our study contributes to determining the microbiological characteristics related to pathogenic CRO and is a good reference for future studies about CRO colonization in healthcare settings in Vietnam.

7. Patents

a. Supplementary Materials:

Table 1: Distribution of environmental samples, number of randomny collected environmental samples, and the number and the ratio of CROs detected

Table 3: Antibiograms of 12 CROs suspected with close relations based on the identifical rate of antibiotic-resistant phylogetype/ BD

Table 3 (cont): Antibiogram of 12 CROs suspected with close relations based on the identifical rate of antibiotic-resistant phylogetype/ BD

b. Author Contributions

Conceptual framework, methodology, design, data acquisition, analyses, and interpretation of study findings, NVK; participating in performing the antimicrobial susceptibility testing and phenotypic carbapenemase detection using the NMIC-500 CPO Detect panel of the BD Phoenix TM Automated Microbiology System, HPPN; review, editing, supervision, and funding acquisition, PN, EG, and KI; preparing and performing WGS for 12 DNA of 12 CRO isolates, L.C; All other authors have read, edited and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

c. Funding:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support “Invitation Research” provided by the Faculty of Public Health, Thammasat University, the Thammasat University Research Unit in Modern Microbiology and Public Health Genomics. Specially, Prof Eugene Athan support us a fund to perform WGS for our study.

d. Institutional Review Board Statement:

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Board of Directors on Ethics in Biomedical Research at THIEN PHUOC NHAN AI CENTER OF CARE AND PROTECTION OF DISABLED CHILDREN (protocol code 026/2565 and date of approval : HCM.City, 19thApril 2021 (Appendix A)

e. Informed Consent Statement:

Written Informed consent was obtained from 20 healthcare workers and 67 residents involved in the study to publish this paper.

f. Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank HCWs and children for their participation in our study. We gratefully acknowledge the Director and Vice Director of Hung Vuong Hospital, Dr. Hoang Thi Diem Tuyet, and Dr. Phan Thi Hang, respectively, for their support. We thank Pham Nguyen Huu Phuc, Tran Dang Thang, Cao Thang Long, Nguyen Thi Tu Tam, Nguyen Thi Hien, and Ta Qui Tan for their support and help in conducting the microbiology tests at the Microbiology Unit of Hung Vuong Hospital. We also thank Dr. Tran Van Hung, Dr. Lam Kim Dung, and Hai Yen for supporting our project.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support “Invitation Research” provided by the Faculty of Public Health, Thammasat University, the Thammasat University Research Unit in Modern Microbiology and Public Health Genomics. Specially, Prof Eugene Athan support us a fund to perform WGS for our study.

g. Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

h. Abbreviations and Acronyms

| 1. Abbreviations of antibiotics |

|

|

| AK: Amikacin; |

CRO: Ceftriaxone; |

NOR: Norfloxacin; |

| AM: Ampicillin; |

CXM: Cefuroxime; |

TZP: Piperacillin/tazobactam; |

| AMC: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; |

CIP: Ciprofloxacin, |

TGC: Tigecylin; |

| AZM: Aztreonam; |

CST: Colistin; |

SXT: Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole; |

| CZ: Cefazolin; |

FO: fosfomycin; |

I: Intermediate, |

| FEP: Cefepime; |

GEN: Gentamicin; |

R: Resistance, |

| FOX: Cefoxitin; |

LVX: Levofloxacin; |

X: MICs of antibiotics are in the range of sensitive or intermediate, |

| CAZ: Ceftazidime; |

MIN: Minocycline; |

N: is an antibiotic not recommended for the treatment of infections |

| CZA: Ceftazidime/ avibactam; |

NFN: Nitrofurantoin; |

|

| 2. Abbreviations related to study |

| ANI: Average nucleotide identity |

B. cepacia: Burkholderia cepacia complex; |

|

| CPE: Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae; |

A. baumannii: Acinetobacter baumannii: |

|

| CPO: Carbapenemase-producing organisms; |

A. faecalis: Alcaligenes faecalis; |

|

| CRE: Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; |

E. cloacae: Enterobacter cloacae; |

|

| CRO: Carbapenem-resistant organisms; |

E. coli: Escherichia coli; |

|

| ESBL: Extended-spectrum β-lactamase; |

K. pneumoniae: Klebsiella pneumoniae |

|

| HCW: Health Care Workers; |

P. aeruginosa: Pseudomonas aeruginosa; |

|

| HCP: Healthcare personnel; |

P. putida: Pseudomonas putida |

|

| NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; |

S. maltophilia: Stenotrophomonas maltophilia; |

|

| PICU: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit |

|

|

| SICU: Surgical Intensive Care Unit |

|

|

| SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; |

|

|

| WGS: Whole Genome Sequencing |

|

|

References

- WHO. Antimicrobial resistance global report on surveillance: 2014 summary. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HSE-PED-AIP-2014.2 2014, (accessed on 23/11/2024).

- CDC. ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE THREATS in the United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf 2013, (accessed on 23/11/2024).

- Canada, P.H.A.o. Antimicrobial resistance and use in Canada: A federal framework for action. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada 2014, 40, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control, E.C.f.D.P.a. "Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2015. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net). Stockholm: ECDC; 2017.," https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/antimicrobial-resistance-surveillance-europe-2015 18 Nov 2020, (accessed on 23/11/2024).

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Epidemiology and Diagnostics of Carbapenem Resistance in Gram-negative Bacteria. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2019, 69, S521–S528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. The Lancet. Infectious diseases 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peleg, A.Y.; Hooper, D.C. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. The New England journal of medicine 2010, 362, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakkoupi, P.; Papagiannitsis, C.C.; Miriagou, V.; Pappa, O.; Polemis, M.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Tzouvelekis, L.S.; Vatopoulos, A.C. An update of the evolving epidemic of blaKPC-2-carrying Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece (2009-10). The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2011, 66, 1510–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porres-Osante, N.; Azcona-Gutiérrez, J.M.; Rojo-Bezares, B.; Undabeitia, E.; Torres, C.; Sáenz, Y. Emergence of a multiresistant KPC-3 and VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli strain in Spain. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2014, 69, 1792–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.A.; Melano, R.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Trueba, G. Mobile genetic elements associated with carbapenemase genes in South American Enterobacterales. The Brazilian journal of infectious diseases : an official publication of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases 2020, 24, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.D.; Kotetishvili, M.; Shurland, S.; Johnson, J.A.; Morris, J.G.; Nemoy, L.L.; Johnson, J.K. How important is patient-to-patient transmission in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli acquisition. American journal of infection control 2007, 35, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]