1. Introduction

Astragalus membranaceus, a perennial herb belonging to the Fabaceae family, is widely distributed in temperate regions of Asia, including northern China, Mongolia, and Russia[

1,

2]. The dried roots, mainly derived from

A.

membranaceus (Fisch.) Bge. Var. Mongholicus (Bge.) Hsiao or

A.

membranaceus (Fisch.) Bge, are collectively known as Astragali Radix (Huangqi) and have been extensively used as medicinal materials in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)[

3]. Phytochemical investigations have revealed that

A. membranaceus is rich in diverse bioactive constituents, including polysaccharides, flavonoids, saponins, and alkaloids, which underpin its broad pharmacological activities, such as immunomodulatory, anti-fatigue, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antiviral effects

[4−10]. In TCM theory,

A. membranaceus is regarded as a representative qi-tonifying herb and is widely prescribed to alleviate conditions associated with qi deficiency, including chronic fatigue, edema, and general debility[

11,

12]. Owing to its combined medicinal and nutritional properties,

A. membranaceus is also classified as a typical medicinal and edible homologous plant. This dual functionality has attracted increasing interest in its application as a functional food ingredient, particularly in the development of health-promoting beverages and dietary supplements[

7].

Despite its considerable potential in functional food development, the application of

A. membranaceus in deeply processed beverages remains limited. Conventional aqueous extraction methods often result in low bioavailability and poor intestinal absorption of its bioactive constituents, thereby restricting their effective utilization in modern functional products. In addition, the intrinsic flavor profile of

A. membranaceus extracts may further limit consumer acceptance. Probiotic fermentation has emerged as a promising strategy to overcome these limitations

[13−16]. Through the action of microbial enzymatic systems, fermentation can degrade macromolecules into smaller, more bioavailable metabolites, enhance the release of bound phytochemicals, and generate novel functional compounds

[17−20]. Simultaneously, fermentation can improve sensory characteristics by modulating taste-active metabolites and organic acid composition, thereby increasing the overall palatability and health-promoting value of fermented herbal products[

21].

Among probiotic lactic acid bacteria,

Pediococcus acidilactici is a homofermentative, Gram-positive strain commonly isolated from fermented foods, plant-derived materials, and the gastrointestinal tract of animals[

22,

23]. As an established probiotic,

P. acidilactici exhibits high tolerance to acidic and bile salt conditions and is capable of producing bacteriocins such as pediocin, which contribute to product biosafety by inhibiting foodborne pathogens

[24−26]. These properties have led to its widespread application in food fermentation and biopreservation. Notably,

P. acidilactici possesses diverse enzymatic activities, including glycosidases and proteases, which enable the efficient biotransformation of complex plant substrates[

27]. During fermentation, this strain can promote the accumulation of functional metabolites such as organic acids, phenyllactic acid, indolelactic acid, and phenolic derivatives, while simultaneously reducing undesirable components[

28]. These metabolic transformations not only enhance nutritional value and flavor complexity but also improve the safety and functional potential of fermented products[

29]. Therefore,

P. acidilactici represents a promising microbial candidate for fermenting medicinal and edible homologous plants such as

A.

membranaceus.

Although probiotic fermentation has been increasingly applied to medicinal and edible herbs, systematic metabolomic investigations focusing on P. acidilactici-fermented A. membranaceus aqueous extracts remain scarce. In particular, comprehensive characterization of fermentation-induced metabolic reprogramming and the associated functional has not yet been fully elucidated. To address this gap, the present study employed ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with Orbitrap mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Orbitrap MS)-based untargeted metabolomics to comprehensively profile metabolic alterations in A. membranaceus aqueous extracts before and after fermentation with P. acidilactici. Multivariate statistical analyses and KEGG pathway enrichment were integrated to identify key differential metabolites and metabolic affected by fermentation. By systematically elucidating the metabolic mechanisms underlying P. acidilactici-mediated fermentation of A. membranaceus, this work provides novel mechanistic insights and a scientific foundation for the development of value-added fermented herbal beverages with enhanced nutritional and functional properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Strain

Methanol, acetonitrile, ammonium hydroxide, and 2-propanol (LC-MS grade) were purchased from CNW Technologies (Düsseldorf, Germany). Ammonium acetate and acetic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Trading Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) was prepared using a Milli-Q purification system (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The isotope-labeled internal standard 2-chloro-L-phenylalanine (10 μg/mL) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mobile phase A consisted of ultrapure water containing 25 mmol/L ammonium acetate and 25 mmol/L ammonium hydroxide, while mobile phase B was HPLC-grade acetonitrile. Pediococcus acidilactici (preservation no. GSICC31620) was obtained from the Gansu Microbial Culture Collection Center (Gansu, China). Prior to inoculation, the strain was activated in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Hopebio, Qingdao, China) at 32 °C for 24 h.

2.2. Preparation and Fermentation of Astragalus membranaceus Extract

Superfine A. membranaceus powder (50 g, >1500 mesh; Shaanxi Wanyuan Biotechnology, Xi’an, China) was mixed with 1 L of ultrapure water and decocted at 100 °C for 2 h. The extract was cooled to room temperature, filtered through sterile cheesecloth to remove coarse residues, and centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 25 °C. The resulting supernatant was collected as the aqueous extract. The extract was sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min and cooled before inoculation. Activated P. acidilactici culture was added at 1% (v/v), and fermentation was performed at 32 °C for 48 h under static conditions. Non-fermented extracts (CK) and fermented extracts (Pa) were stored at −80 °C until metabolomic analysis. Each group consisted of 10 biological replicates.

2.3. Metabolite Extraction

A 100 μL aliquot of each sample was transferred to a microcentrifuge tube and mixed with 400 μL of extraction solvent (methanol:acetonitrile = 1:1, v/v) containing 2-chloro-L-phenylalanine (10 μg/mL) as the internal standard. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s, sonicated in an ice-water bath for 10 min, and incubated at −40 °C for 1 h to precipitate proteins. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,800 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected for UHPLC-Orbitrap MS analysis. Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling equal aliquots of all processed sample extracts and analyzed periodically throughout the sequence to monitor system stability.

2.4. UHPLC-Orbitrap MS Analysis

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.7 μm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (ultrapure water with 25 mmol/L ammonium acetate and 25 mmol/L ammonium hydroxide) and solvent B (acetonitrile). The injection volume was 2 μL, and the autosampler temperature was maintained at 4 °C. The gradient program was as follows: 0–11 min linear transition from 85% to 25% A, 11–12 min linear transition to 2% A, 12–14 min hold at 2% A, 14–14.1 min return to 85% A, and 14.1–16 min re-equilibration at 85% A. Mass spectrometric detection was performed on an Orbitrap Exploris 120 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated in information-dependent acquisition (IDA) mode via Xcalibur 4.4. Full-scan MS and MS/MS spectra were acquired using the following parameters: sheath gas flow 50 Arb; auxiliary gas flow 15 Arb; capillary temperature 320 °C; full MS resolution 60,000; MS/MS resolution 15,000; stepped normalized collision energies (NCE) of 20, 30, and 40 eV; and spray voltage +3.8 kV (positive mode) or −3.4 kV (negative mode). Data were collected in both ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage.

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

All analyses were based on 10 biological replicates per group, consistent with the sample set submitted for UHPLC-Orbitrap MS metabolomic profiling. Raw LC-MS data were converted to mzXML format using ProteoWizard (v3.0.20) and processed in R (v4.1.2) using the XCMS Package (v3.18.0) for peak detection, retention time correction, alignment, and integration. Metabolites were annotated by matching MS/MS spectra against BiotreeDB v3.0 (Biotree Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). QC samples were injected at regular intervals throughout the sequence to assess instrument stability. principal component analysis (PCA) was used to evaluate overall metabolic variance and detect outliers, while orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was employed to identify discriminatory metabolites. Model robustness was assessed by seven-fold cross-validation and 200-time permutation testing. Differential metabolites were defined according to the following criteria: variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1, Student’s t-test p < 0.05, and fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67. Volcano plots and other graphical summaries were used for visualization. Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using MetaboAnalyst 5.0 based on KEGG annotations, and with p < 0.05 were considered significantly affected.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. UHPLC–Orbitrap MS-Based Metabolic Profiling of Astragalus membranaceus Extracts

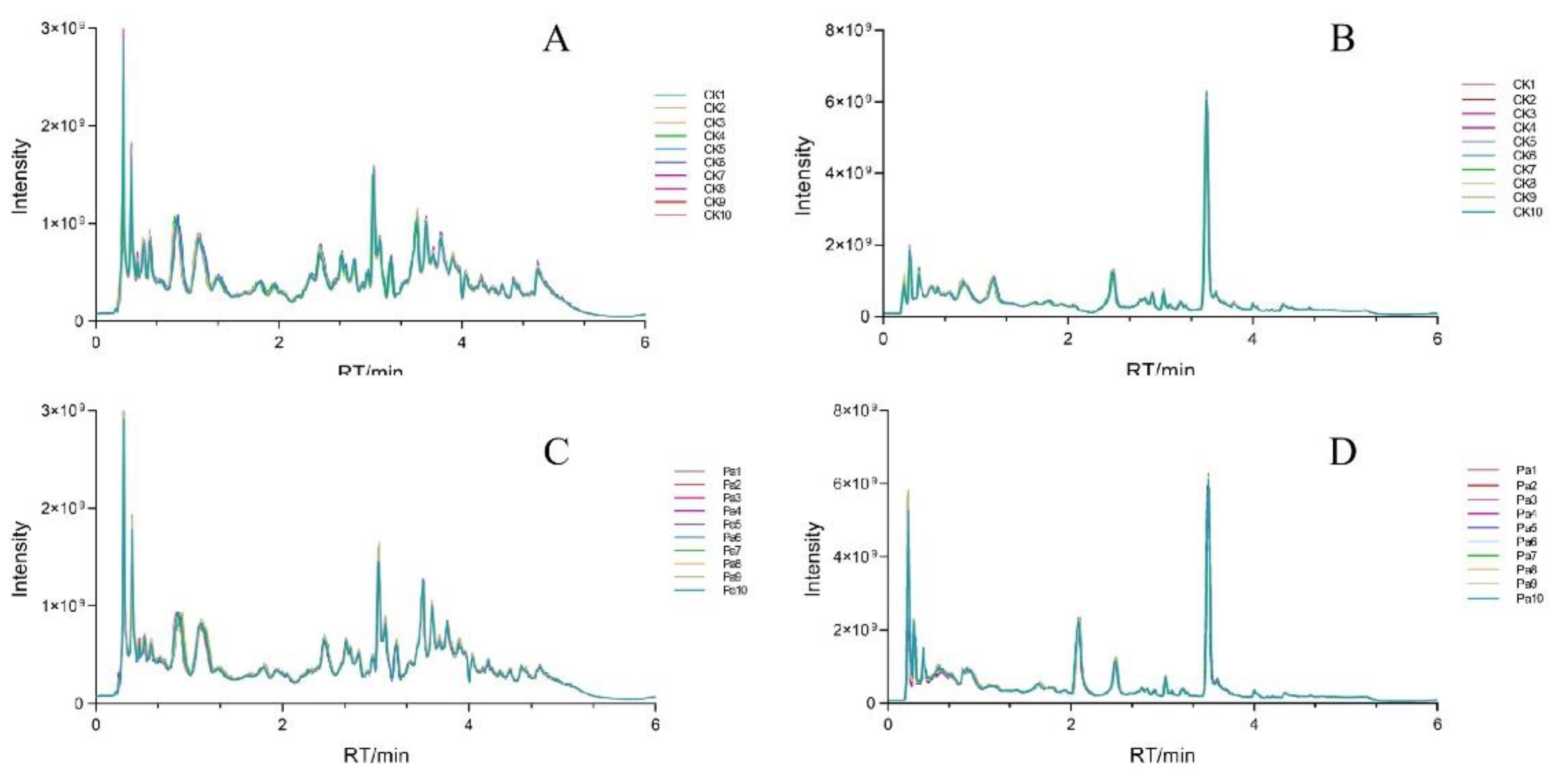

To characterize the global metabolic profiles of

A. membranaceus aqueous extracts before and after fermentation with

Pediococcus acidilactici, untargeted UHPLC–Orbitrap MS analysis was performed in both positive and negative ionization modes. The total ion current (TIC) chromatograms of representative non-fermented control (CK) and fermented (Pa) samples are shown in

Figure 1. Pronounced differences were observed between the two groups in terms of retention time distribution, peak intensity, and the number of detected features in both ionization modes, indicating substantial fermentation-induced metabolic alterations. Notably, the positive and negative ion modes captured distinct but complementary subsets of metabolites, reflecting differences in ionization efficiency and chemical properties of the detected compounds. The combined use of both ionization modes therefore enabled more comprehensive metabolome coverage and improved the reliability of downstream multivariate and differential analyses. Overall, these results demonstrate that

P. acidilactici fermentation markedly reshaped the metabolic landscape of

A. membranaceus aqueous extracts, providing a solid analytical basis for subsequent statistical discrimination and functional interpretation.

3.2. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

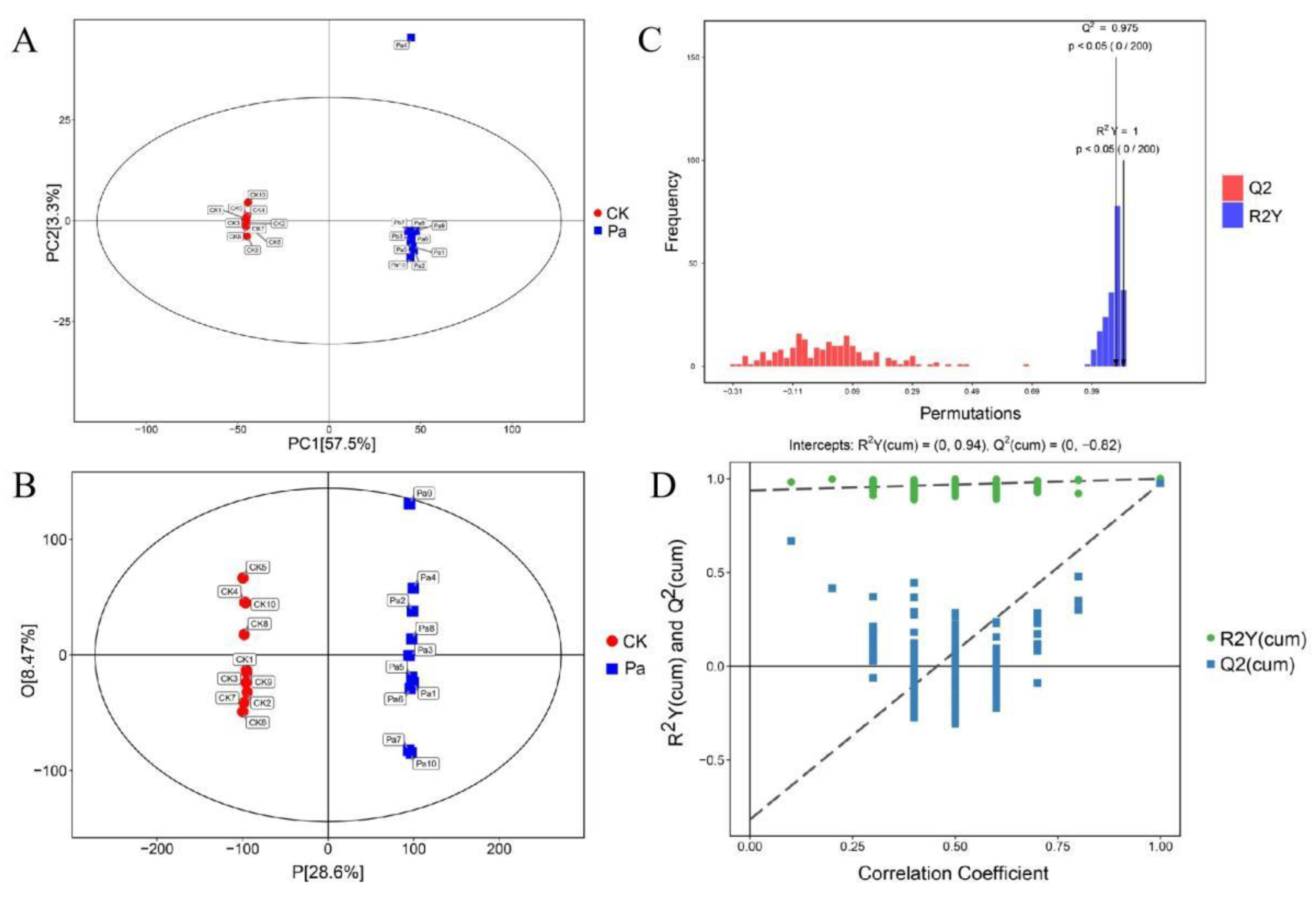

To further evaluate the impact of

P. acidilactici fermentation on the metabolic profiles of

A. membranaceus aqueous extracts, multivariate statistical analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), were performed. The PCA score plot revealed a clear separation between the non-fermented control (CK) and fermented (Pa) groups along the first principal component (PC1), indicating substantial global metabolic differences induced by fermentation (

Figure 2A). PC1 and PC2 accounted for 57.5% and 3.3% of the total variance, respectively, with a cumulative contribution of 60.8%. All samples were distributed within the 95% confidence interval, except for one Pa sample (Pa 9), which showed a slight deviation but did not affect the overall clustering pattern. To enhance group discrimination and identify metabolites contributing to the observed differences, a supervised OPLS-DA model was constructed (

Figure 2B). The model yielded R

2X = 0.371, R

2Y = 1.000, and Q

2 = 0.975, indicating strong explanatory and predictive performance. To assess model robustness and exclude the possibility of overfitting, a 200-iteration permutation test was conducted. The resulting negative Q

2 intercept confirmed that the model was statistically valid and not overfitted. Collectively, the PCA and OPLS-DA results demonstrate that

P. acidilactici fermentation induced pronounced metabolic reprogramming in

A. membranaceus aqueous extracts. The clear group separation observed in the unsupervised PCA reflects global metabolic shifts, while the supervised OPLS-DA model provides a reliable statistical framework for subsequent screening and interpretation of differential metabolites.

3.3. Analysis of Differential Metabolites

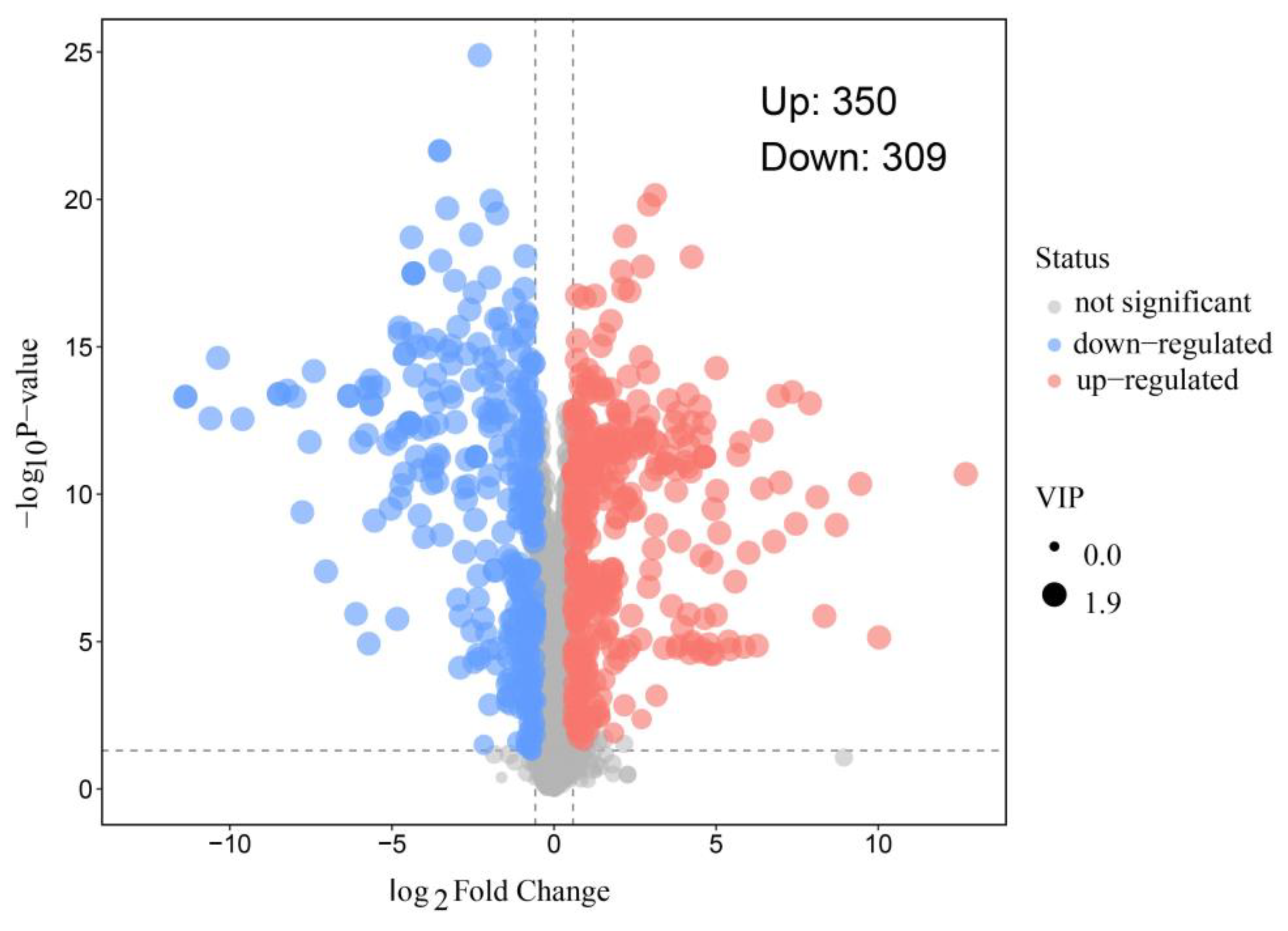

To comprehensively evaluate the metabolic alterations induced by P. acidilactici fermentation, differential metabolites in A. membranaceus aqueous extracts were screened based on the OPLS-DA model using the criteria of variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1, Student’s t-test p < 0.05, and fold change (FC) ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.67. A total of 659 differential metabolites were identified, among which 350 metabolites were significantly upregulated and 309 were downregulated following fermentation. These metabolites encompassed a wide range of chemical classes, including organic acids and their derivatives, amino acids and derivatives, nucleotides and related compounds, glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, polyphenols, terpenoids, and saponins. Collectively, these results indicate that P. acidilactici fermentation induced extensive remodeling of the metabolite composition of A. membranaceus, which may underlie changes in its nutritional, sensory, and functional properties.

To visualize the overall distribution and statistical significance of differential metabolites, a volcano plot was constructed (

Figure 3). Each point represents an individual metabolite, with the abscissa corresponding to the log

2-transformed fold change between the Pa and CK groups, and the ordinate representing the −log

10-transformed p-value. Metabolites without significant changes are shown in gray, whereas significantly upregulated and downregulated metabolites are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. The size of each point reflects its VIP value, indicating its contribution to group discrimination in the OPLS-DA model. As illustrated, a large number of metabolites exhibited significant abundance changes following fermentation, with both up- and downregulated metabolites broadly distributed across the metabolic space, highlighting the pronounced metabolic response induced by

P. acidilactici fermentation.

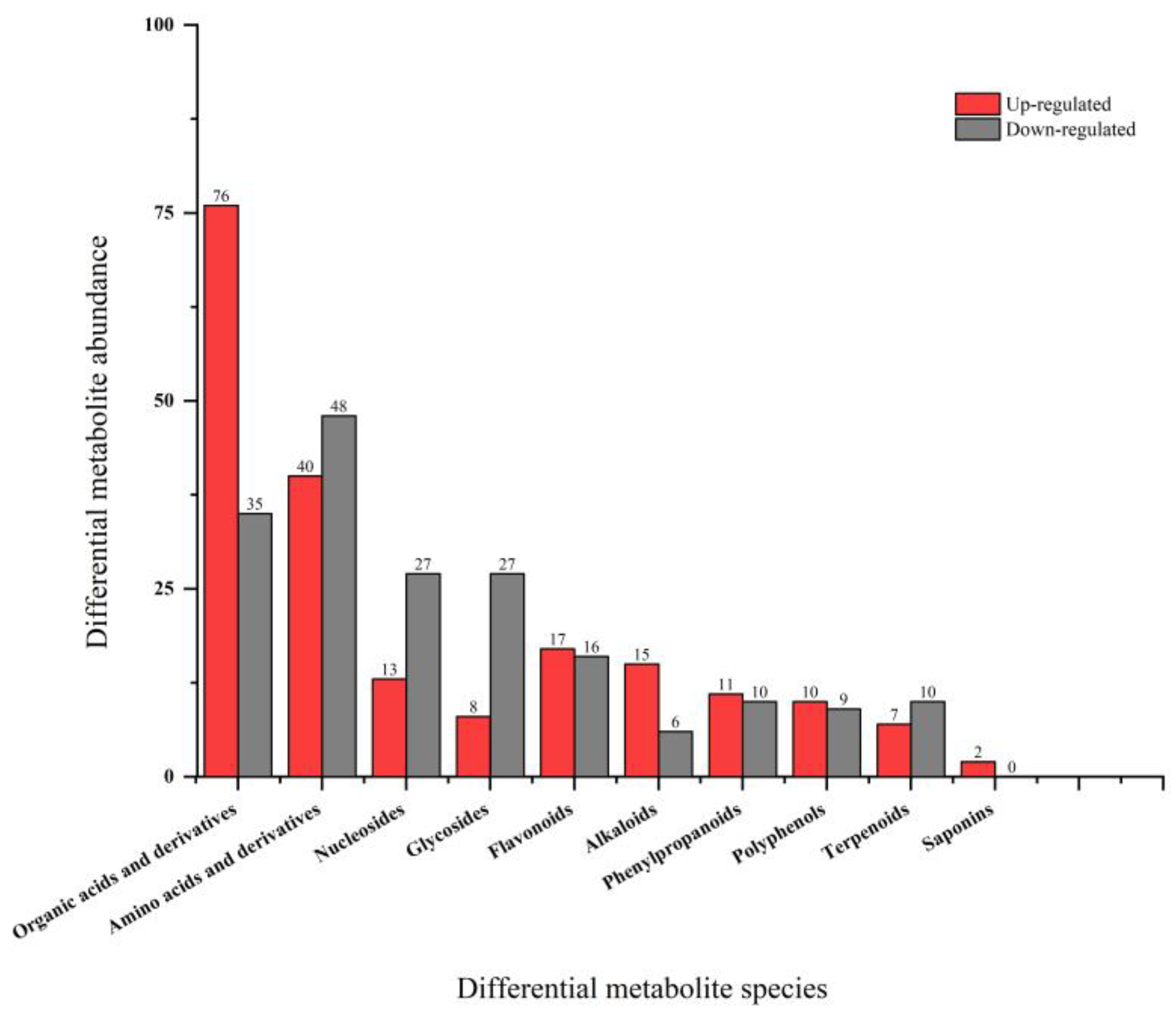

To further characterize the metabolic alterations at the compositional level, differential metabolites were classified according to their chemical categories based on VIP ranking (

Figure 4). Organic acids and their derivatives, amino acids and derivatives, nucleosides, glycosides, flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, polyphenols, terpenoids, and saponins constituted the predominant metabolite classes affected by fermentation. Variations in both metabolite diversity and relative abundance were observed across these categories, indicating that

P. acidilactici fermentation exerted a broad impact on multiple metabolic of

A. membranaceus.

Notably, metabolites closely related to the characteristic bioactive components of A. membranaceus—including organic acids, flavonoids, saponins, alkaloids, amino acid derivatives, and phenylpropanoids—were prominently modulated. These compound classes are well recognized for their contributions to the immunomodulatory, antioxidant, and health-promoting properties of A. membranaceus. The observed alterations suggest that P. acidilactici fermentation may influence the functional potential of the extract by reshaping key biosynthetic and transformation , thereby providing a biochemical basis for the development of fermented A. membranaceus products with enhanced nutritional and functional attributes.

3.3.1. Organic Acids and Their Derivatives

Organic acids and their derivatives play central roles in fermentation systems by influencing flavor development, microbial stability, and metabolic activity[

30]. In the present study, 111 differential organic acids and related compounds were identified, among which 76 were significantly upregulated and 35 were downregulated after fermentation with

P. acidilactici. These results indicate that fermentation markedly reshaped the organic acid profile of the

A. membranaceus water extract. Following fermentation, several organic acids exhibited pronounced increases in relative abundance, including hydroxyphenyllactic acid, lactate, phenyllactic acid, indolelactic acid, 10-hydroxydecanoic acid, pyruvate, caproic acid, 2-hydroxyoctanoic acid, and hydroxyisocaproic acid. In contrast, metabolites such as royal jelly acid, fumaric acid, 5-oxooctanoic acid, L-malic acid, and pantothenic acid were significantly reduced. These coordinated changes suggest a substantial reorganization of organic acid metabolism during fermentation. Hydroxyphenyllactic acid, derived from tyrosine metabolism, has been reported to possess immunomodulatory and antimicrobial activities[

31,

32]. Lactate, a typical end product of lactic acid bacterial fermentation, increased by 18.97-fold, consistent with the reduction of pyruvate through lactate dehydrogenase–mediated reactions. Accumulation of lactate is commonly associated with redox balance maintenance and acidification of the fermentation environment, which may contribute to microbial stability and characteristic sensory properties. Phenyllactic acid, known for its antimicrobial activity against a broad range of microorganisms, may further enhance product preservation

[33−35]. Indolelactic acid, a tryptophan-derived metabolite produced by lactic acid bacteria, has been associated with anti-inflammatory responses and gut barrier function in previous studies[

36]. The increased abundance of 10-hydroxydecanoic acid may reflect microbial transformation of fatty acid precursors during fermentation. Conversely, the relative abundance of malic acid decreased by 12.66-fold after fermentation. This reduction is likely related to malolactic conversion, in which malic acid is transformed into lactic acid by lactic acid bacteria, resulting in a softer acid profile[

37]. Such conversion has been widely reported to reduce sharp acidity and improve sensory quality in fermented products. The observed decrease in pantothenic acid may be associated with its utilization as a precursor for coenzyme A biosynthesis or with its instability under acidic fermentation conditions.

3.3.2. Flavonoid Compounds

Flavonoids, one of the major bioactive constituents of

A. membranaceus, underwent notable alterations during fermentation. A total of 33 flavonoid-related differential metabolites were identified, including 17 upregulated and 16 downregulated compounds, indicating a bidirectional modulation of flavonoid metabolism by

P. acidilactici fermentation. Among the upregulated flavonoids, isoliquiritigenin showed the most pronounced increase, suggesting its strong contribution to the differentiation between fermented and non-fermented samples. Isoliquiritigenin is a chalcone-type flavonoid reported to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities[

38,

39]. Its marked accumulation after fermentation may be associated with microbial enzymatic processes such as deglycosylation or structural conversion of precursor flavonoids[

40]. In addition, several other flavonoids—including catechin, licochalcone A, formononetin, naringenin-7-O-glucoside, homoplantaginin, diosmetin, hydroxygenkwanin, tectorigenin, isoverbascoside, isoformononetin, and 5-hydroxyflavone—also showed increased abundance following fermentation. These compounds have been widely reported to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties

[41−44], suggesting that fermentation may influence the functional composition of flavonoids in

A. membranaceus. Notably, isoformononetin, a characteristic isoflavone of

A. membranaceus, exhibited a significant increase after fermentation, consistent with enrichment of representative bioactive constituents of this herb. Such accumulation may reflect microbial transformation processes that favor the release of aglycones or enhance the relative abundance of more bioactive forms. In contrast, several flavonoids, including morusin, hesperetin dihydrochalcone, and eucannabinolide A, were significantly decreased. These reductions may be attributable to enzymatic degradation, glycosidic hydrolysis, or further microbial metabolism during fermentation. Overall, although the levels of individual flavonoids varied, the flavonoid profile of the fermented extract was substantially restructured.

3.3.3. Alkaloids

Alkaloids, an important group of nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites in

A. membranaceus, also exhibited marked compositional changes following fermentation. In total, 21 alkaloid-related differential metabolites were identified, including 15 upregulated and 6 downregulated compounds, indicating that

P. acidilactici fermentation substantially influenced alkaloid-related metabolic features. Among the upregulated alkaloids, 6,7-dimethoxyquinolin-4-ol showed the most pronounced increase and a high VIP value, highlighting its contribution to group discrimination. Several other alkaloids or alkaloid-like compounds—including coclaurine A, N-feruloyloctopamine, N-acetylhistamine, columbamine, allocryptopine, corynine, vindoline, and berberine-related compounds—also exhibited increased abundance after fermentation. These compounds have been reported in plant-derived or fermentation-associated matrices and are known to display diverse biological activities, including anticancer, antimicrobial, antioxidant, neuroactive, and anti-inflammatory effects

[45−47]. Their increased detection may be associated with microbial biotransformation processes, such as enzymatic modification or enhanced extractability of bound forms. Vindoline, a monoterpene indole alkaloid precursor, has been reported to participate in alkaloid biosynthesis in plants[

48]. Its increased abundance after fermentation may reflect microbial-mediated liberation or transformation rather than de novo synthesis. Similarly, berberine-related compounds, which share structural features with known isoquinoline alkaloids, have been associated with antimicrobial and metabolic regulatory activities and may contribute to the functional properties of the fermented extract. In contrast, several alkaloids, including ionone, 4,5-dimethylsimeondine, piperolactam D, carlina oxide, and solanine D, were significantly reduced after fermentation. These decreases may result from microbial degradation or conversion into other nitrogen-containing metabolites during fermentation.

3.3.4. Phenylpropanoids

phenylpropanoids, a major class of plant-derived secondary metabolites, showed pronounced compositional changes during fermentation. A total of 21 phenylpropanoid-related differential metabolites were identified, including 11 upregulated and 10 downregulated compounds, indicating extensive modulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism by P. acidilactici. Among the upregulated phenylpropanoids, several coumarin derivatives accumulated markedly. Specifically, 8-acetyl-7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin, 7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid, and 8-acetyl-7-hydroxycoumarin increased by 27.28-fold, 19.16-fold, and 14.07-fold, respectively. Their increased abundance suggests that fermentation may promote transformation or enrichment of specific phenylpropanoid derivatives. In addition, phenylpropanoid glycosides such as Uhdoside A, Docynicaside A, and α-peltatin were also significantly upregulated, contributing to increased chemical diversity. In contrast, the abundance of 7-hydroxy-3-(2-methoxyphenyl)coumarin decreased after fermentation. Several other phenylpropanoid-related compounds, including 3-indoleacetonitrile, meranzin hydrate, and 5-carboxymellein, were also reduced. These changes may be associated with microbial-mediated biotransformation processes such as glycosidic hydrolysis or side-chain modification, reflecting a redistribution of phenylpropanoid-related metabolites rather than simple accumulation or depletion.

3.3.5. Polyphenols

Polyphenols, which contribute substantially to the antioxidant capacity of

A. membranaceus, also exhibited notable changes following fermentation. In total, 19 polyphenol-related differential metabolites were identified, including 10 upregulated and 9 downregulated compounds, indicating bidirectional modulation of polyphenol metabolism during fermentation. Several polyphenols—including macluraxanthone, oxyresveratrol, 2′,5′-dihydroxyacetophenone, sanggenon A, octyl gallate, resveratrol, and emodin—showed increased abundance after fermentation. These compounds have been widely reported to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiproliferative activities[

49]. Their enrichment may be attributed to microbial-mediated liberation or transformation of polyphenolic precursors within the

A. membranaceus matrix. Resveratrol, a well-studied stilbenoid polyphenol, plays important roles in redox regulation and metabolic health[

49]. Emodin, a representative anthraquinone derivative, has also been reported to exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities[

50]. The increased abundance of these compounds following fermentation likely reflects microbial enzymatic processes such as deglycosylation or structural modification. In contrast, certain polyphenols, including phloroglucinol, were significantly reduced after fermentation, possibly due to further microbial metabolism or utilization. These changes collectively indicate dynamic restructuring of the polyphenol profile during

P. acidilactici fermentation.

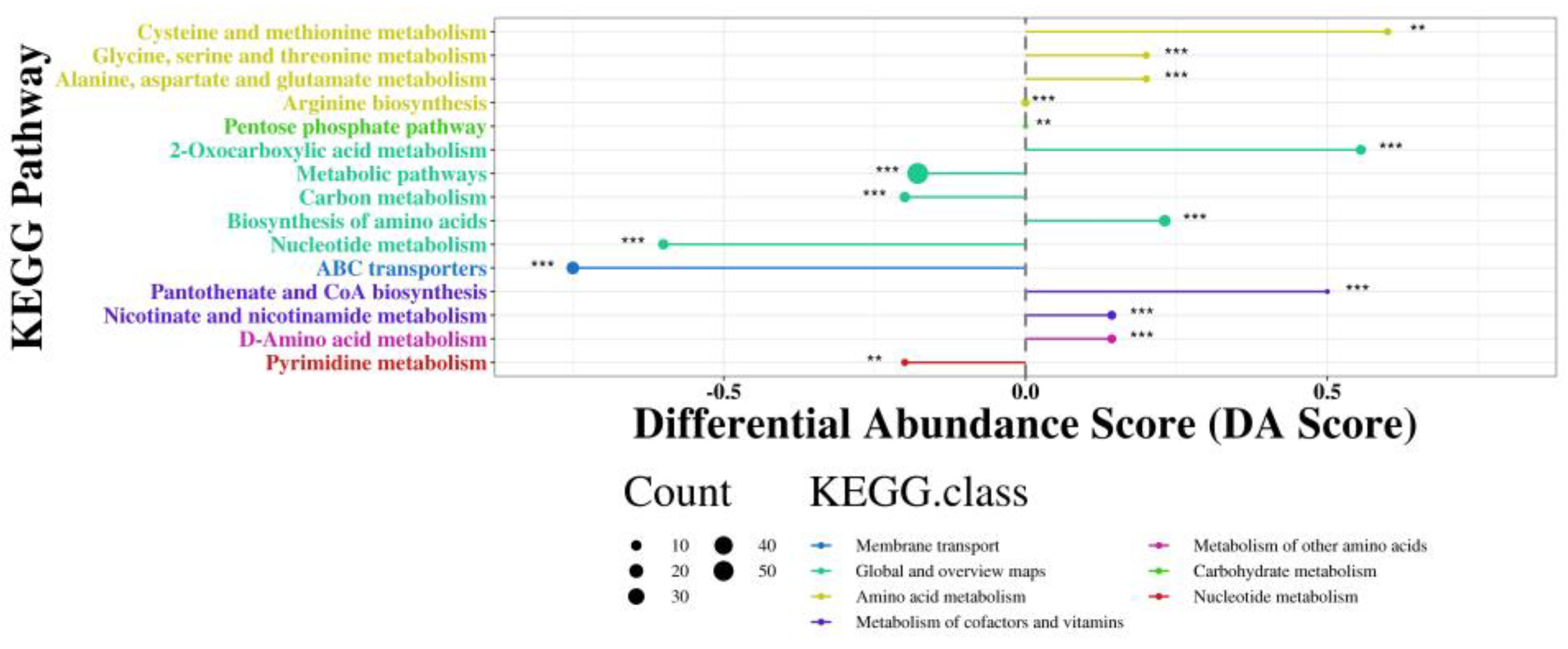

3.4. Metabolic Pathway Analysis

To gain a systems-level understanding of the metabolic reorganization induced by

P. acidilactici fermentation, pathway enrichment analysis was performed based on KEGG annotations of the identified differential metabolites. Rather than reflecting isolated changes in individual compounds, the enrichment results revealed coordinated modulation of multiple metabolic modules, primarily involving amino acid metabolism, central carbon metabolism, and the metabolism of cofactors and vitamins. These pathway-level alterations suggest that fermentation reshapes the metabolic network of

A. membranaceus aqueous extracts in an integrated and functionally oriented manner. The global trends of pathway perturbation are summarized in the differential abundance (DA) score plot (

Figure 5), which integrates both the number and directional changes of metabolites within each pathway. With positive DA scores, indicating overall upregulation, were predominantly associated with amino acid biosynthesis, carbon metabolism, and cofactor metabolism, whereas with negative DA scores, such as pyrimidine metabolism and ABC transporters, exhibited an overall downregulation. This asymmetric distribution implies a metabolic shift favoring biosynthetic and energy-related processes during fermentation.

Amino acid metabolism emerged as the most prominently affected metabolic domain. Multiple , including cysteine and methionine metabolism, glycine/serine/threonine metabolism, and alanine/aspartate/glutamate metabolism, were significantly enriched. Among these, arginine biosynthesis showed the strongest activation. This observation is consistent with the substantial post-fermentation increase in amino acids and their derivatives, including metabolites such as citrulline and creatine. From a biological perspective, enhanced arginine metabolism may reflect increased nitrogen assimilation and redistribution, which are essential for supporting microbial growth and metabolic activity during fermentation. In addition, arginine-related metabolites have been reported to contribute to immunomodulatory and metabolic regulatory functions[

51], suggesting potential relevance to the functional properties of the fermented extract. Central carbon metabolism also underwent marked reorganization following fermentation. Core , including carbon metabolism and 2-oxocarboxylic acid metabolism, were generally upregulated, indicating intensified turnover of carbon skeletons and enhanced metabolic flux through energy-related . Concurrent enrichment of the pentose phosphate pathway suggests an increased generation of reducing equivalents, such as NADPH, which are required for anabolic reactions and redox homeostasis. These changes collectively point to an elevated metabolic activity state in the fermentation system, characterized by coordinated energy production and biosynthesis. Notably, involved in the metabolism of cofactors and vitamins were significantly activated. In particular, pantothenate and coenzyme A biosynthesis, as well as nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, exhibited strong enrichment. This finding is in agreement with the pronounced accumulation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+) observed after fermentation. As a central redox cofactor, NAD

+ plays a critical role in cellular energy metabolism and oxidative balance. Its increased abundance may therefore reflect enhanced redox cycling and metabolic efficiency within the fermentation matrix, potentially contributing to the improved functional and antioxidant characteristics of the fermented product.

In contrast, several associated with nucleotide metabolism and membrane transport, including pyrimidine metabolism and ABC transporters, were downregulated. The suppression of ABC transporter–related may be indicative of altered substrate uptake and transport requirements during fermentation, possibly reflecting a transition from nutrient acquisition toward intracellular metabolic processing. Although D-amino acid metabolism was also annotated, its functional significance in this context remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that P. acidilactici fermentation induces a coordinated reorganization of central metabolic networks in A. membranaceus aqueous extracts, rather than isolated changes in individual metabolites. Untargeted UHPLC-Orbitrap MS-based metabolomic analysis revealed that fermentation systematically reshaped amino acid metabolism, carbon metabolism, and cofactor biosynthesis , resulting in pronounced shifts in metabolic fluxes associated with energy balance, redox regulation, and biosynthetic capacity. In particular, the activation of arginine biosynthesis, together with enhanced carbon metabolism and nicotinate/nicotinamide metabolism, reflects an integrated metabolic response driven by microbial activity and substrate transformation. These pathway-level alterations provide a mechanistic framework for understanding the metabolic basis of probiotic fermentation in medicinal and edible herbs.

At the metabolite level, fermentation led to the accumulation of multiple functionally relevant compounds, including lactate, phenyllactic acid, indolelactic acid, isoliquiritigenin, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), while reducing the abundance of certain precursor or intermediate metabolites. The coordinated enrichment of organic acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, and polyphenols suggests that P. acidilactici fermentation not only enhances metabolite diversity but also favors the formation of compounds associated with antimicrobial activity, redox regulation, and immunomodulatory potential. These compositional shifts are consistent with the observed pathway activation patterns and highlight the role of microbial biotransformation in modulating the functional properties of A. membranaceus extracts.

Collectively, the present findings provide metabolomic evidence that probiotic fermentation represents an effective strategy for reprogramming the chemical and functional landscape of A. membranaceus. By integrating pathway-level remodeling with targeted enrichment of bioactive metabolites, P. acidilactici fermentation offers a rational approach for improving the nutritional quality, functional potential, and sensory characteristics of A. membranaceus-based products. This work establishes a scientific foundation for the development of value-added fermented herbal beverages and contributes to a deeper understanding of microbial-driven metabolic regulation in medicinal and edible plant systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jie Song and Zhiye Wang; Methodology, Jie Song; Investigation, Jie Song, Weiwen Lu and Ali Yang; Formal Analysis, Bin Li and Chen Li; Editing, Ting Mao and Zhiye Wang; Supervision, Bin Ji; Funding Acquisition, Zhiye Wang.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Fund of Gansu Academy of Sciences, grant number 2023QN-04. The APC was funded by the Gansu Academy of Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding anthor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Su, Y.; Mu, Y.; Sun, S.; Chen, G. Root-associated microbiomes are influenced by multiple factors and regulate the growth and quality of Astragalus membranaceus (fisch) Bge. var. mongholicus (Bge.) Hsiao. Rhizosphere 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Nazhand, A.; Lucarini, M.; Silva, A.M.; Souto, S.B.; Guerra, F.; Severino, P.; Zaccardelli, M.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A. Astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus Bunge): botanical, geographical, and historical aspects to pharmaceutical components and beneficial role. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali 2021, 32, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, L.; Zheng, S.; Wang, D.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S. Review of the Botanical Characteristics, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology of Astragalus membranaceus (Huangqi). Phytotherapy Research 2014, 28, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Li, J.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Wei, J. Biosynthesis and Pharmacological Activities of Flavonoids, Triterpene Saponins and Polysaccharides Derived from Astragalus membranaceus. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xie, L.; Shen, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xie, j. Recent advances in Astragalus polysaccharides: Structural characterization, bioactivities and gut microbiota modulation effects. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2024, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, M.; Gao, B.; Hasan, A.; Li, J.; Bao, Y.o.; Fan, J.; Yu, R.; Yi, Y.; Ågren, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Ye, M.; Qiao, X. Characterization and protein engineering of glycosyltransferases for the biosynthesis of diverse hepatoprotective cycloartane-type saponins in Astragalus membranaceus. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2023, 21, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; Chen, W.; Vong, C.T.; Yao, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Astragali Radix (Huangqi): A promising edible immunomodulatory herbal medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2020, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, X.; Yang, L.; Huang, B.; Lin, G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Lin, R. Efficacy of Astragalus Membranaceus (Huang Qi) for Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. Integrative Cancer Therapies 2025, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Dong, Q.; Yang, D.-H.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, M.; Luo, X.; Zhou, C.; Ye, M.; Li, L.; He, Y. Astragali radix (Huangqi): a time-honored nourishing herbal medicine. Chinese Medicine 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, M.; Guo, B.; Zhou, X.; Cui, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ren, Y. Severe enterovirus A71 infection is associated with dysfunction of T cell immune response and alleviated by Astragaloside A. Virologica Sinica 2025, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Li, T.C.; Yang, Y.W.; Huang, W.S.; Lu, M.K.; Tseng, C.H.; Huang, H.C.; Chen, K.F.; Hsu, T.S.; Hsu, Y.T.; Tsai, C.H.; Hsieh, C.L. Effects of the traditional Chinese herb Astragalus membranaceus in patients with poststroke fatigue: A double-blind, randomized, controlled preliminary study. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2016, 194, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.H.; Tsai, W.J.; Loke, S.H.; Wu, T.S.; Chiou, W.F. Astragalus membranaceus flavonoids (AMF) ameliorate chronic fatigue syndrome induced by food intake restriction plus forced swimming. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2009, 122, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miao, Q.; Pan, C.; Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Qu, L.; Yin, Y.; Wei, Y. Research advances in probiotic fermentation of Chinese herbal medicines. iMeta 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Han, L.; Lin, Y.Q.; Li, T.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, L.H.; Tong, X.L. Probiotic Fermentation of Herbal Medicine: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2023, 51, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Ye, T.; Yu, J.; Wu, H.; Niu, P.; Wei, X.; Liu, H.; Fang, H. A novel concoction method of Chinese medicinal and edible plants: probiotic fermentation, sensory and functional composition analysis. Sustainable Food Technology 2025, 3, 822–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, X.; Qiu, S.; Huang, W.; Su, Y.; Li, L. Determining the changes in metabolites of Dendrobium officinale juice fermented with starter cultures containing Saccharomycopsis fibuligera FBKL2.8DCJS1 and Lactobacillus paracasei FBKL1.3028 through untargeted metabolomics. BMC Microbiology 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Jiang, X.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, B.; Huang, Y. Probiotic Fermentation of Kelp Enzymatic Hydrolysate Promoted its Anti-Aging Activity in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice by Modulating Gut Microbiota. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2023, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.C.; Huang, H.; Jiang, B.Y.; Guo, R.X.; Zhang, K.; Du, B.; Li, P. Probiotic fermentation of Polygonatum plant polysaccharides converting fructans to glucans with enhanced anti-obesity activity. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, H.; Lin, L.; Zhao, M. Probiotic fermentation affects the chemical characteristics of coix seed-chrysanthemum beverage: Regulatory role in sensory and nutritional qualities. Food Bioscience 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, J.; Cao, J.; Zhang, G.; Ling, J. New flavonoid and their anti-A549 cell activity from the bi-directional solid fermentation products of Astragalus membranaceus and Cordyceps kyushuensis. Fitoterapia 2024, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangyu, M.; Muller, J.; Bolten, C.J.; Wittmann, C. Fermentation of plant-based milk alternatives for improved flavour and nutritional value. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2019, 103(23-24), 9263–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Song, Q.; Wang, M.; Ren, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, S. Comparative genomics analysis of Pediococcus acidilactici species. Journal of Microbiology 2021, 59, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, H.; Lee, H.J. Investigation of Bacteriocin Production Ability of Pediococcus acidilactici JM01 and Probiotic Properties Isolated From Tarak, a Conventional Korean Fermented Milk. Food Science & Nutrition 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, B.; Bao, J. pH shifting adaptive evolution stimulates the low pH tolerance of Pediococcus acidilactici and high L-lactic acid fermentation efficiency. Bioresource Technology 2025, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.; Jantama, K.; Prasitpuriprecha, C.; Wansutha, S.; Phosriran, C.; Yuenyaow, L.; Cheng, K.-C.; Jantama, S.S. Harnessing Fermented Soymilk Production by a Newly Isolated Pediococcus acidilactici F3 to Enhance Antioxidant Level with High Antimicrobial Activity against Food-Borne Pathogens during Co-Culture. Foods 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, N.; Li, G. Probiotic characteristics and whole-genome sequence analysis of Pediococcus acidilactici isolated from the feces of adult beagles. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, A.; Noda, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Kumar, B.; Kaur, B. Application ofPediococcus acidilacticiBD16 (alaD+) expressing L-alanine dehydrogenase enzyme as a starter culture candidate for secondary wine fermentation. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment 2021, 35, 1643–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Chaichana, N.; Boonsan, J.; Dechathai, T.; Suwannasin, S.; Singkhamanan, K.; Wonglapsuwan, M.; Pomwised, R.; Surachat, K. Comparative genomic analysis of the Pediococcus genus reveals functional diversity for fermentation and probiotic applications. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2025, 27, 4597–4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myo, N.Z.; Kamwa, R.; Khurajog, B.; Pupa, P.; Sirichokchatchawan, W.; Hampson, D.J.; Prapasarakul, N. Industrial production and functional profiling of probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici 72 N for potential use as a swine feed additive. Scientific Reports 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zou, M.; Tang, C.; Ao, H.; He, L.; Qiu, S.; Li, C. The insights into sour flavor and organic acids in alcoholic beverages. Food Chemistry 2024, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, A.; Yang, C.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Li, X.; Bi, J.; Xiang, B.; Jiang, K. Hyperoside, a dietary flavonoid, protects against endometritis via gut microbiota-dependent production of hydroxyphenyllactic acid and the gut–uterus axis. Food & Function 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Parappilly, S.J.; Radhakrishnan, E.K.; George, S.M. Antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of human gut lactic acid bacteria. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2024, 55, 3529–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, M.; Kong, Y.; Fan, X.; Sun, S.; Du, C.; Gong, H. Antifungal mechanisms of phenyllactic acid against Mucor racemosus: Insights from spore growth suppression, and proteomic analysis. Food Chemistry 2025, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Bi, M.; Li, S.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Jiang, X.; Yu, T. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm formation by phenyllactic acid in pasteurized milk is associated with suppression of the Agr system. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2026, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Wu, X. Proteomic investigation of the antibacterial and anti-biofilm mechanisms of phenyllactic acid against Shigella flexneri and its application in tofu preservation. Food Bioscience 2025, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Li, Q.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, G.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, G.; Tian, P. Bifidobacteria with indole-3-lactic acid-producing capacity exhibit psychobiotic potential via reducing neuroinflammation. Cell Reports Medicine 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.T.; Nguyen, H.T. Environmental stress for improving the functionality of lactic acid bacteria in malolactic fermentation. The Microbe 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qi, T.; Zhou, L.; Lin, P.; Chen, Q.; Li, X.; He, R.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Qi, F. Isoliquiritigenin alleviates abnormal sarcomere contraction and inflammation in myofascial trigger points via the IL-17RA/Act1/p38 pathway in rats. Phytomedicine 2025, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Yang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Deng, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, H. Protective Effects of Isoliquiritigenin and Licochalcone B on the Immunotoxicity of BDE-47: Antioxidant Effects Based on the Activation of the Nrf2 Pathway and Inhibition of the NF-κB Pathway. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Lim, B.; Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, S.-J.; Eom, S.H. Deglycosylation patterns of isoflavones in soybean extracts inoculated with two enzymatically different strains of lactobacillus species. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2020, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zharani, M.; Mubarak, M.; Almuqri, E.; Rudayni, H.; Aljarba, N.; Yaseen, K.; Albatli, S.; Alkahtani, S.; Nasr, F.; Al-Doaiss, A.; Al-eissa, M. Catechin (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) supplement restores the oxidation: antioxidation balance through enhancing the total antioxidant capacity in Wistar rats with cadmium-induced oxidative stress. Journal of Nutritional Science 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco, M.; Guzman, L.; Olloquequi, J.; Cano, A.; Fortuna, A.; Vazquez-Carrera, M.; Verdaguer, E.; Auladell, C.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A. Licochalcone A prevents cognitive decline in a lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation mice model. Molecular Medicine 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Yu, W.; Gao, W.; Luo, H.; Fang, X. The Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Formononetin, an Active Constituent of Pueraria montana Var. Lobata, via Modulation of Macrophage Autophagy and Polarization. Molecules 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Cao, X.; Zhao, J. Homoplantaginin exerts therapeutic effects on intervertebral disc degeneration by alleviating TNF-α-induced nucleus pulposus cell senescence and inflammation. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, H.A.; Alghamdi, S.S.; Al-Zahrani, M.H.; Trivilegio, T.; Bahattab, S.; AlRoshody, R.; Alhaidan, Y.; Alghamdi, R.A.; Matou-Nasri, S. Reticuline and Coclaurine Exhibit Vitamin D Receptor-Dependent Anticancer and Pro-Apoptotic Activities in the Colorectal Cancer Cell Line HCT116. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2025, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.Y.; Lin, T.H.; Chen, C.Y.; He, Y.H.; Huang, W.C.; Hsieh, C.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Chang, W.C. Stephania tetrandra and Its Active Compound Coclaurine Sensitize NSCLC Cells to Cisplatin through EFHD2 Inhibition. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Li, S.; Guo, P.; Wang, L.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Z.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yan, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhao, C. Columbamine suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma cells through down-regulation of PI3K/AKT, p38 and ERK1/2 MAPK signaling pathways. Life Sciences 2019, 218, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Liu, T.; Gao, J.; Xu, J.; Gou, Y.; Pan, Y.; Li, D.; Ye, C.; Pan, R.; Huang, L.; Xu, Z.; Lian, J. De Novo Biosynthesis of Vindoline and Catharanthine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BioDesign Research 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.; Kim, K.W.; Liu, Z.; Dong, L.; Yoon, C.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.C.; Oh, H.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, S.C. Macluraxanthone B inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses in RAW264.7 and BV2 cells by regulating the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Immunopharmacology and Immunotoxicology 2021, 44, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.X.; Zhang, H.Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, C.H. Comprehensive insights into emodin compounds research in medicinal chemistry. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2025, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, J.M.; Liu, Y.; Suntornsaratoon, P.; Jones, A.; Ambat, J.; Bala, A.; Kanattu, J.J.; Flores, J.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Upadhyay, R.; Bhupana, J.N.; Su, X.; Li, W.V.; Gao, N.; Ferraris, R.P. Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG-driven remodeling of arginine metabolism mitigates gut barrier dysfunction. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2025, 329, G162–G185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).