1. Introduction

Metabolomics is an emerging field that provides a comprehensive analysis of metabolic profiles in biological systems, offering critical insights into plant biochemistry, secondary metabolite production, and stress response mechanisms.

Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS), commonly known as the Russian dandelion, has gained attention primarily for its high rubber content, making it a valuable industrial crop [

1]. However, its potential medicinal properties remain largely unexplored. Given its close phylogenetic relationship with

Taraxacum officinale, which is well-documented for its pharmacological benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and antimicrobial properties, TKS may also possess bioactive compounds with significant therapeutic applications [

2,

3].

Previous studies on

T. officinale have demonstrated its flavonoids, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and polysaccharides, which contribute to diverse pharmacological effects such as immune modulation, metabolic regulation, and neuroprotection [

4,

5]. Research on other

Taraxacum species suggests that their bioactive properties vary depending on environmental conditions, plant parts, and developmental stages [

6]. Despite this growing body of research, little is known about the metabolic composition of TKS and its potential as a medicinal resource.

This study applies widely targeted metabolomics using UPLC-MS/MS to comprehensively analyze the metabolic profiles of roots and leaves of field-grown TKS plants. By identifying key metabolites and their associated pathways using KEGG enrichment analysis, we aim to determine whether TKS shares medicinal properties with T. officinale and to explore its potential pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications. The findings of this study will not only contribute to the understanding of TKS metabolism but also broaden its utilization beyond rubber production, positioning it as a promising candidate for therapeutic applications.

highlight controversial and diverging hypotheses when necessary. Finally, briefly mention the main aim of the work and highlight the principal conclusions. As far as possible, please keep the introduction comprehensible to scientists outside your particular field of research. References should be numbered in order of appearance and indicated by a numeral or numerals in square brackets—e.g., [

1] or [

2,

3], or [

4,

5,

6]. See the end of the document for further details on references.

2. Materials and Methods

The Kultevar™ Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) dandelion plants were cultivated under field conditions to ensure optimal growth. The plants were directly seeded and harvested at full maturity, which occurs approximately ten months after germination. At this stage, both roots and leaves were fully developed and suitable for metabolomic analysis. To maintain sample integrity, plants were harvested by hand, washed thoroughly to remove soil and contaminants, and immediately prepared for shipment using dry ice for overnight delivery. This method ensured that the biochemical and structural properties of the samples remained intact for analysis within 24 hours of harvesting.

Metabolite extraction was performed using a 70% methanol-based protocol to maximize recovery. Dried plant material (100 mg) was weighed into 2 mL centrifuge tubes, followed by the addition of 1.0 mL of 70% methanol. The samples were vortex-mixed for 30 seconds, subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction at 40°C for 30 minutes, and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter and stored at −80°C.

Ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis was conducted using an Agilent SB-C18 column (1.8 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm). The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (pure water with 0.1% formic acid) and solvent B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid), with a gradient elution program designed to optimize separation efficiency. The flow rate was set at 0.35 mL/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 40°C. The sample injection volume was 2 μL.

Mass spectrometric detection was performed using a Triple Quadrupole-Linear Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer (AB6500 QTRAP, SCIEX) equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source. Both positive and negative ionization modes were used. The source temperature was set at 550°C, and the ion spray voltage was maintained at +5500 V (positive mode) and −4500 V (negative mode). The curtain gas (CUR) was set to 25 psi, while ion source gas I (GSI) and ion source gas II (GSII) were set to 50 psi and 60 psi, respectively. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for targeted metabolite quantification, with optimized declustering potential (DP) and collision energy (CE) for each ion pair.

Metabolite identification was performed using Metware Biotechnology Inc.'s in-house metabolomics database (MWDB). Identification was based on accurate mass determination, MS/MS fragmentation patterns, retention time alignment, and isotopic distribution analysis. Identified metabolites were further mapped to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database to classify metabolic pathways and assess biological significance.

Statistical analysis included principal component analysis (PCA) and orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) to differentiate metabolic profiles between root and leaf samples. Differential metabolites were identified based on variable importance in projection (VIP) scores greater than 1.0, fold-change thresholds (≥ 2.0 or ≤ 0.5), and statistical significance (p < 0.05, Student’s t-test). Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using Euclidean distance measures to visualize metabolite distribution patterns across tissues.

This study did not involve human or animal subjects, and therefore, ethical approval was not required. All raw metabolomic data and analysis pipelines are available upon request from the corresponding author.

3. Results

The metabolomic analysis of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) revealed distinct biochemical compositions between root and leaf tissues, highlighting key metabolic differences. Through targeted and untargeted metabolomic approaches, we identified a diverse range of metabolites, including flavonoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, and lipid-derived compounds. The findings provide valuable insights into the functional specialization of TKS tissues and their potential medicinal applications.

3.1. Metabolite Identification and Classification

A total of 1813 metabolites were identified in

Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS), spanning diverse biochemical categories, including flavonoids, polyphenols, alkaloids, amino acids, and lipid-derived metabolites (

Table 1). Differential analysis revealed 964 metabolites exhibiting significant variations between root and leaf tissues (

Table 2). The identification of these metabolites provides insights into the specialized metabolic functions of different plant parts.

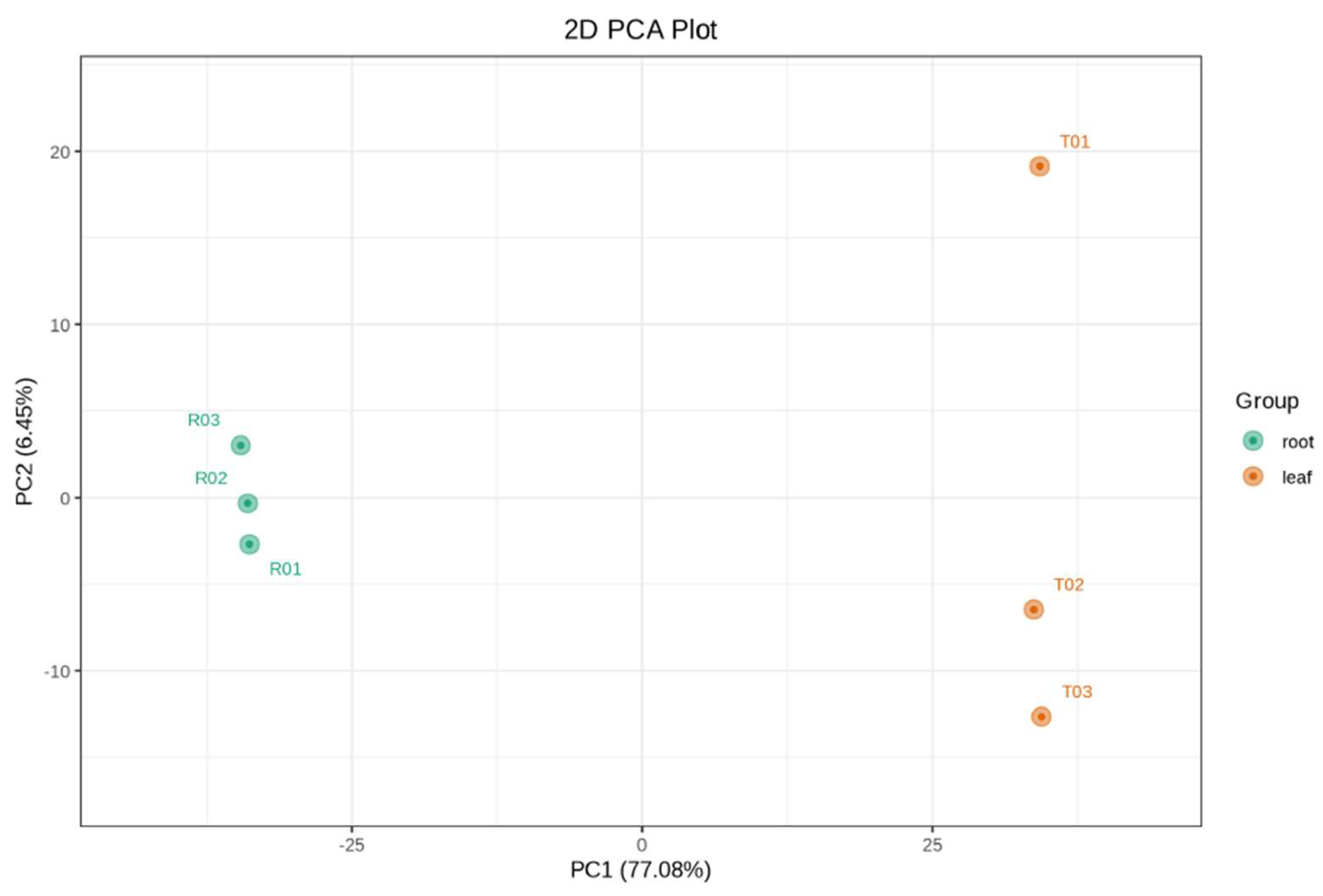

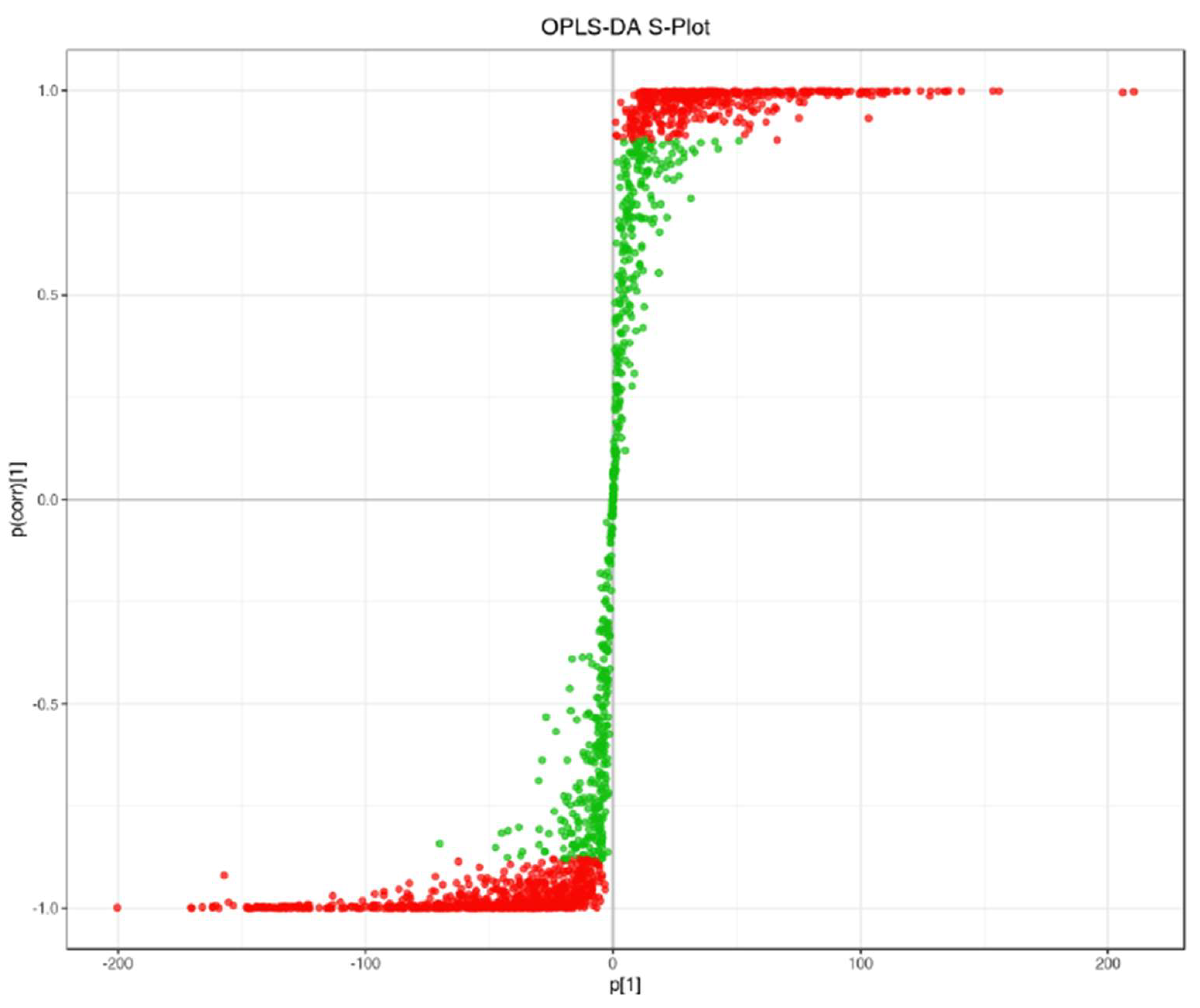

3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and OPLS-DA

PCA and OPLS-DA analyses were performed to distinguish metabolic profiles between TKS leaves and roots. PCA demonstrated clear separation between the two tissue types, indicating distinct biochemical compositions (

Figure 1). The first two principal components accounted for a significant portion of the variance, confirming metabolic differentiation. OPLS-DA further refined the classification by identifying key metabolites responsible for variation, highlighting significant metabolic specialization in TKS.

3.3. OPLS-DA and Differential Metabolite Analysis

OPLS-DA confirmed the PCA results, identifying key metabolites contributing to the variance. A comprehensive metabolomic analysis identified 964 distinct metabolites differentiating TKS leaves and roots, with 609 downregulated and 355 upregulated in roots compared to leaves (

Table 2). This variation indicates significant biochemical specialization between these plant tissues.

Several key metabolites were found to be upregulated in leaves. Among them, 1,3-O-Dicaffeoylquinic Acid (Cynarin) is known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (REF). Additionally, 1’-O-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenethyl)-O-caffeoyl-glucoside, a phenolic glycoside, may contribute to antioxidant activity (REF). Another notable compound, (6R,9R)-3-Oxo-α-ionol-β-D-malonyl-glucoside, is a carotenoid-derived metabolite that could play a role in plant defense mechanisms (REF).

In contrast, certain metabolites were more abundant in roots. The study identified (9Z,11E,13E,15Z)-4-Oxo-9,11,13,15-Octadecatetraenoic Acid, a lipid oxidation product that may be associated with stress response (REF). Additionally, 1,2,4-Trihydroxyanthraquinone, a quinone derivative, was found to have potential antimicrobial effects (REF). Pathway analysis using the KEGG database suggests that certain metabolites are uniquely enriched in either the leaves or the roots. While specific exclusive compounds were not detailed, hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis (PCA) confirmed clear metabolic distinctions between these tissues.

The leaves of TKS are likely to contain higher concentrations of flavonoids and polyphenols, compounds that are well-documented for their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits. Meanwhile, the roots exhibit greater abundance of alkaloids and lipid-derived metabolites, which are often associated with stress response and bioactivity.

This metabolic differentiation highlights the specialized functions of TKS leaves and roots, which may have implications for their medicinal and industrial applications.

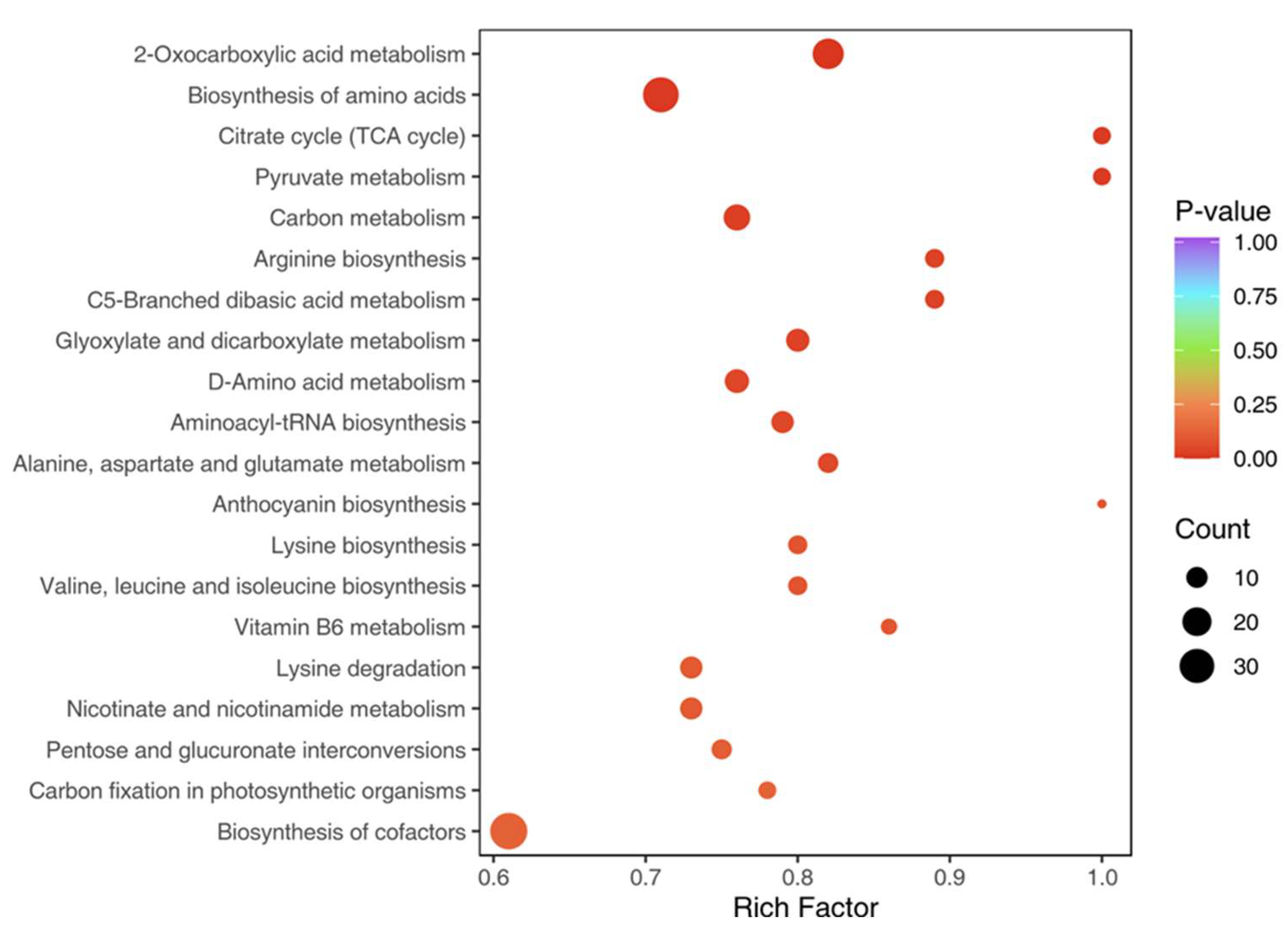

3.4. KEGG Pathway Analysis

O KEGG enrichment analysis revealed that differential metabolites were involved in primary metabolic pathways such as amino acid biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and lipid metabolism. The presence of secondary metabolites, including polyphenols and terpenoids, suggests specialized adaptations in TKS for stress tolerance and growth regulation. The presence of chicoric acid, a known antioxidant found in Taraxacum officinale, suggests potential medicinal applications for TKS.

Table 3.

KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Identified Metabolites.

Table 3.

KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Identified Metabolites.

| KEGG Pathway |

Number of Metabolites |

| Amino Acid Biosynthesis |

112 |

| Flavonoid Biosynthesis |

89 |

| Lipid Metabolism |

135 |

Figure 3.

KEGG enrichment diagram of differential metabolites Note: The X-axis represents the Rich Factor and the Y-axis represents the pathway. The color of points reflects the p-value. The darker the red, the more significant the enrichment. The size of the dot represents the number of enriched differential metabolites.

Figure 3.

KEGG enrichment diagram of differential metabolites Note: The X-axis represents the Rich Factor and the Y-axis represents the pathway. The color of points reflects the p-value. The darker the red, the more significant the enrichment. The size of the dot represents the number of enriched differential metabolites.

3.5. Medicinal Potential of TKS

Taraxacum officinale (common dandelion) is known to contain several bioactive compounds with significant medicinal properties. Chicoric acid has been identified as a potent antioxidant with antiviral and anti-inflammatory benefits (REF). The flavonoids luteolin and apigenin exhibit anticancer and neuroprotective effects (REF). Taraxasterol has been recognized for its anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective properties (REF). Additionally, sesquiterpene lactones have demonstrated potential antimicrobial and immunomodulatory effects (REF). In the current analysis of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS), cynarin (1,3-O-Dicaffeoylquinic Acid) was detected in the leaf, a compound well-documented in T. officinale for its liver-protective and antioxidant properties. While chicoric acid, luteolin, and taraxasterol were not explicitly identified in the dataset, the high concentration of flavonoids and phenylpropanoids in TKS suggests the potential presence of structurally related bioactive compounds. Previous studies on T. officinale have consistently shown a clear distinction in metabolite distribution between leaves and roots. The leaves are typically enriched with flavonoids, phenolic acids, and antioxidants, whereas the roots contain higher concentrations of sesquiterpene lactones and inulin, compounds known for their role in gut health and immune system modulation.

The findings from the TKS metabolomic dataset align with these established trends. The leaves of TKS demonstrate a preference for flavonoid and polyphenol production, while the roots exhibit higher levels of alkaloids, lipid derivatives, and secondary metabolites, indicating a functional role in stress tolerance. Therefore, we can conclude that the metabolic profile of TKS shares notable similarities with T. officinale, reinforcing its potential for medicinal applications. The presence of cynarin and other polyphenols in TKS leaves suggests comparable health benefits to those documented in T. officinale. Additionally, the root metabolome reflects a composition that may support stress adaptation and bioactivity.

Further targeted analysis is required to confirm the presence of key flavonoids and terpenoids that are characteristic of T. officinale.

4. Discussion

The metabolomic profiling of Taraxacum kok-saghyz (TKS) revealed a diverse array of metabolites, including flavonoids, alkaloids, lipids, amino acids, and phenolic compounds, with notable differences between roots and leaves. These findings align with previous studies on Taraxacum officinale, which demonstrated a rich composition of bioactive compounds contributing to various medicinal properties. The high presence of phenolic compounds and flavonoids in TKS leaves suggests antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential, similar to those observed in T. officinale. In contrast, the root metabolome exhibited a greater abundance of alkaloids and lipid derivatives, compounds often associated with stress response and bioactivity.

The differentiation of metabolic profiles between roots and leaves, as confirmed by PCA and OPLS-DA, highlights the specialized functions of these tissues. The upregulation of specific metabolites in leaves, such as cynarin and phenolic glycosides, supports their potential application in pharmaceutical and nutraceutical formulations. Similarly, the identification of lipid oxidation products and quinone derivatives in roots suggests possible antimicrobial and stress-adaptive properties. KEGG pathway analysis further confirmed the involvement of differentially expressed metabolites in critical biosynthetic pathways, including amino acid biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, and lipid metabolism, reinforcing their significance in plant defense and metabolic regulation.

These findings provide valuable insights into the medicinal potential of TKS, yet further investigation is required to fully characterize the functional properties of the identified metabolites. Comparative studies with T. officinale and other related species could help elucidate shared and unique bioactive compounds. Additionally, targeted bioassays are necessary to validate the pharmacological effects of the metabolites identified in this study.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive metabolic profile of Taraxacum kok-saghyz, identifying key bioactive compounds with potential medicinal applications. The distinct metabolomic differentiation between leaves and roots underscores their specialized biochemical roles, with leaves exhibiting higher concentrations of flavonoids and polyphenols, while roots contain more alkaloids and lipid-derived metabolites. KEGG pathway analysis further confirmed their involvement in essential biosynthetic processes.

These findings suggest that TKS holds promise for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications, warranting further exploration of its therapeutic potential. Future research should focus on functional validation of identified metabolites, their bioactivity in clinical settings, and optimizing TKS cultivation to enhance its medicinal value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Michele Tan, and Daniel R. Swiger; methodology, Jeffrey Chu.; software, Jeffrey Chu.; validation, Jeffrey Chu.; formal analysis, Jeffrey Chu; investigation, Michele Tan.; resources, Daniel R. Swiger; data curation, Jeffrey Chu; writing—original draft preparation, Michele Tan; writing—review and editing, Michele Tan, Jeffrey Chu, Daniel R. Swiger.; visualization, Jeffrey Chu.; supervision, Daniel R. Swiger.; project administration, Michele Tan.; funding acquisition, Daniel R. Swiger. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Metware Biotechnology Inc. for performing the metabolomics experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TKS |

Taraxacum kok-saghyz |

| UPLC-MS/MS |

Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| PCA |

Principal Component Analysis |

| OPLS-DA |

Orthogonal Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis |

| KEGG |

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| VIP |

Variable Importance in Projection |

| MRM |

Multiple Reaction Monitoring |

| ESI |

Electrospray Ionization |

| CUR |

Curtain Gas |

| GSI |

Ion Source Gas I |

| GSII |

Ion Source Gas II |

| MWDB |

Metware Biotechnology Inc. in-house Metabolomics Database |

| LD |

Linear Dichroism |

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of Open Access Journals |

References

- Clare, B.A.; Conroy, R.S.; Spelman, K. The diuretic effect in human subjects of an extract of Taraxacum officinale folium over a single day. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 929–934. [CrossRef]

- González-Castejón, M.; Visioli, F.; Rodríguez-Casado, A. Diverse biological activities of Taraxacum officinale Weber ex F.H. Wigg. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 120. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Kitts, D.D. Antioxidant, prooxidant, and cytotoxic activities of solvent-fractionated dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) flower extracts in vitro. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Schütz, K.; Carle, R.; Schieber, A. Taraxacum—A review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 313–323. [CrossRef]

- Whaley, W.G.; Bowen, J.S. Russian dandelion (Taraxacum kok-saghyz): An emergency source of natural rubber. Econ. Bot. 1947, 1, 233–265. [CrossRef]

- Zidorn, C.; Schubert, B.; Stuppner, H. Altitudinal differences in the content of phenolics in flowering heads of Matricaria chamomilla cv. BONA. Plant Biol. 2005, 7, 363–369. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).