1. Introduction

Quantum batteries are quantum-mechanical systems designed to store and release energy under controlled operations, exploiting genuinely quantum resources such as coherence, correlations, and entanglement [

1]. Their study is motivated by three central objectives: maximizing the amount of extractable work (ergotropy), enhancing the charging power, and protecting stored energy against decoherence and dissipation.

The notion of ergotropy provides a rigorous quantifier of useful energy, defined as the maximum work extractable from a quantum state via unitary operations [

1]. Within this framework, collective effects have attracted particular attention, as they may enable charging protocols that outperform independent or local strategies. In this context, the Dicke model [

2], describing the collective coupling of an ensemble of two-level systems (TLS) to a common bosonic mode, has emerged as a paradigmatic platform to investigate collective quantum batteries [

1].

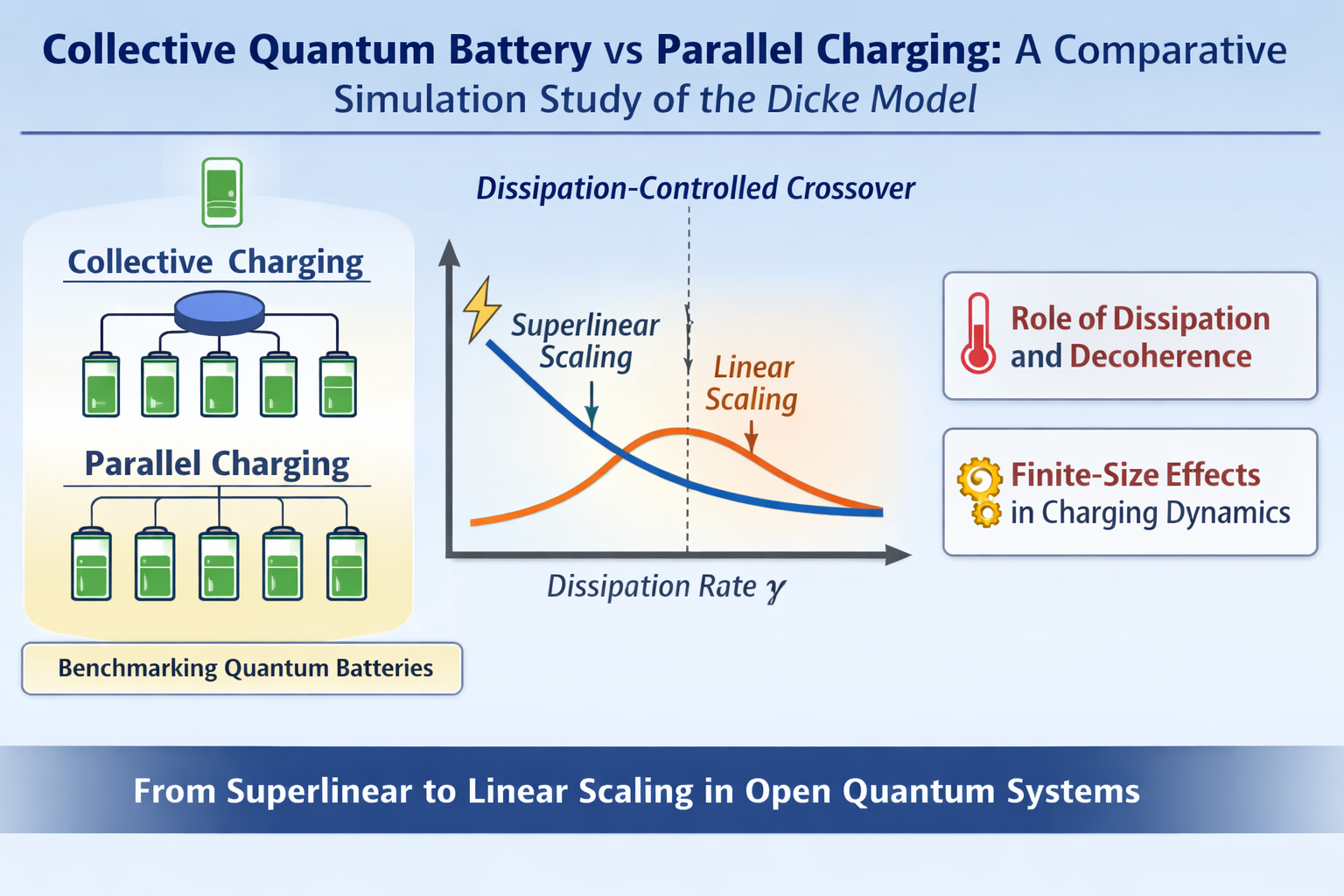

A central claim in the field is the possibility of superlinear scaling of the average charging power with the number of battery cells. For collective charging protocols, theoretical analyses predict power scalings as fast as

, whereas parallel charging architectures—where each TLS is charged independently—are expected to scale linearly with

N [

1,

3]. However, it has also been emphasized that not all apparent enhancements should be interpreted as genuine quantum advantages. In particular, collective speedups may arise from interaction topology or correlated driving rather than from intrinsically quantum correlations [

4].

Several works have explored the microscopic origin and robustness of collective charging advantages. Binder

et al. showed that the build-up of entanglement during the charging process can enable faster-than-classical energy transfer [

5]. Conversely, Andolina

et al. demonstrated that local constraints, correlations, and decoherence mechanisms can severely limit extractable work and suppress scaling advantages in realistic settings [

6]. Moreover, it has been shown that even separable but correlated states may exhibit apparent superlinear behavior when the system–bath interaction structure is nontrivial, further blurring the distinction between classical and quantum enhancements [

4].

From an experimental perspective, collective light–matter platforms operating in the strong and ultrastrong coupling regimes [

7], as well as hybrid architectures such as spin-mechanical systems [

8], provide promising testbeds for implementing quantum batteries. Nevertheless, dissipation, detuning, and finite coherence times remain unavoidable and call for systematic benchmarking against suitable non-collective reference architectures.

In this work, we perform a direct numerical comparison between two charging paradigms under identical physical resources:

- 1.

a collective quantum battery, where an ensemble of N TLS interacts collectively with a single cavity mode via the Dicke Hamiltonian;

- 2.

a parallel (non-collective) battery, where N TLS are charged independently by separate cavity modes, providing a linear benchmark.

By simulating the open-system dynamics using Lindblad master equations, we analyze stored energy, optimal charging time, and average charging power as functions of the system size and dissipation strength. This approach allows us to explicitly identify the parameter regimes in which collective charging advantages persist, as well as the conditions under which decoherence and losses drive a crossover to classical-like linear scaling.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Collective (Quantum) Battery

We model the collective quantum battery using the Dicke Hamiltonian [

1,

2]

where

and

are the cavity and two-level system (TLS) transition frequencies, respectively, and

g denotes the light–matter coupling strength. The operators

and

represent collective spin operators for an ensemble of

N identical TLS.

The Dicke model captures the coherent interaction of multiple TLS with a common bosonic mode, leading to collective phenomena such as superradiant emission and enhanced light–matter coupling. In the context of quantum batteries, this collective coupling enables charging dynamics that differ qualitatively from independent or local charging architectures, and has been shown to allow superlinear scaling of charging power under idealized conditions [

1]. In the following sections, we use this model as a reference framework to investigate how collective charging advantages emerge and how they are affected by dissipation and finite-size effects.

2.2. Parallel (Non-Collective) Battery

As a reference benchmark, we consider a parallel charging architecture in which each two-level system (TLS) interacts independently with its own cavity mode [

3]. The corresponding Hamiltonian reads

where

(

) denotes the annihilation (creation) operator of the cavity mode coupled to the

ith TLS.

In this architecture, each TLS–cavity subsystem evolves independently, and no collective correlations are generated during the charging process. As a consequence, the total stored energy and average charging power scale linearly with the number of cells. In practice, the dynamics of the full system can therefore be obtained from the single-cell solution and rescaled by a factor of N, providing a natural non-collective benchmark against which collective charging advantages can be assessed.

3. Methods

We model the charging dynamics of both collective and parallel battery architectures using a Markovian open-system description based on the Lindblad master equation

where

H denotes either the collective Hamiltonian

or the parallel benchmark Hamiltonian

,

is the cavity decay rate, and

is the spontaneous relaxation rate of the TLS. The Lindblad dissipator is defined as

Unless stated otherwise, the TLS are initialized in their ground state , while the cavity field is prepared in a coherent state . During the evolution, we monitor the stored energy in the TLS ensemble, the optimal charging time (defined as the time at which the stored energy reaches its maximum), and the corresponding average charging power. Numerical simulations are performed using the QuTiP library. For the collective model, the cavity Hilbert space is truncated to a maximum photon number , which is sufficient to ensure numerical convergence for the parameter regimes considered.

4. Results

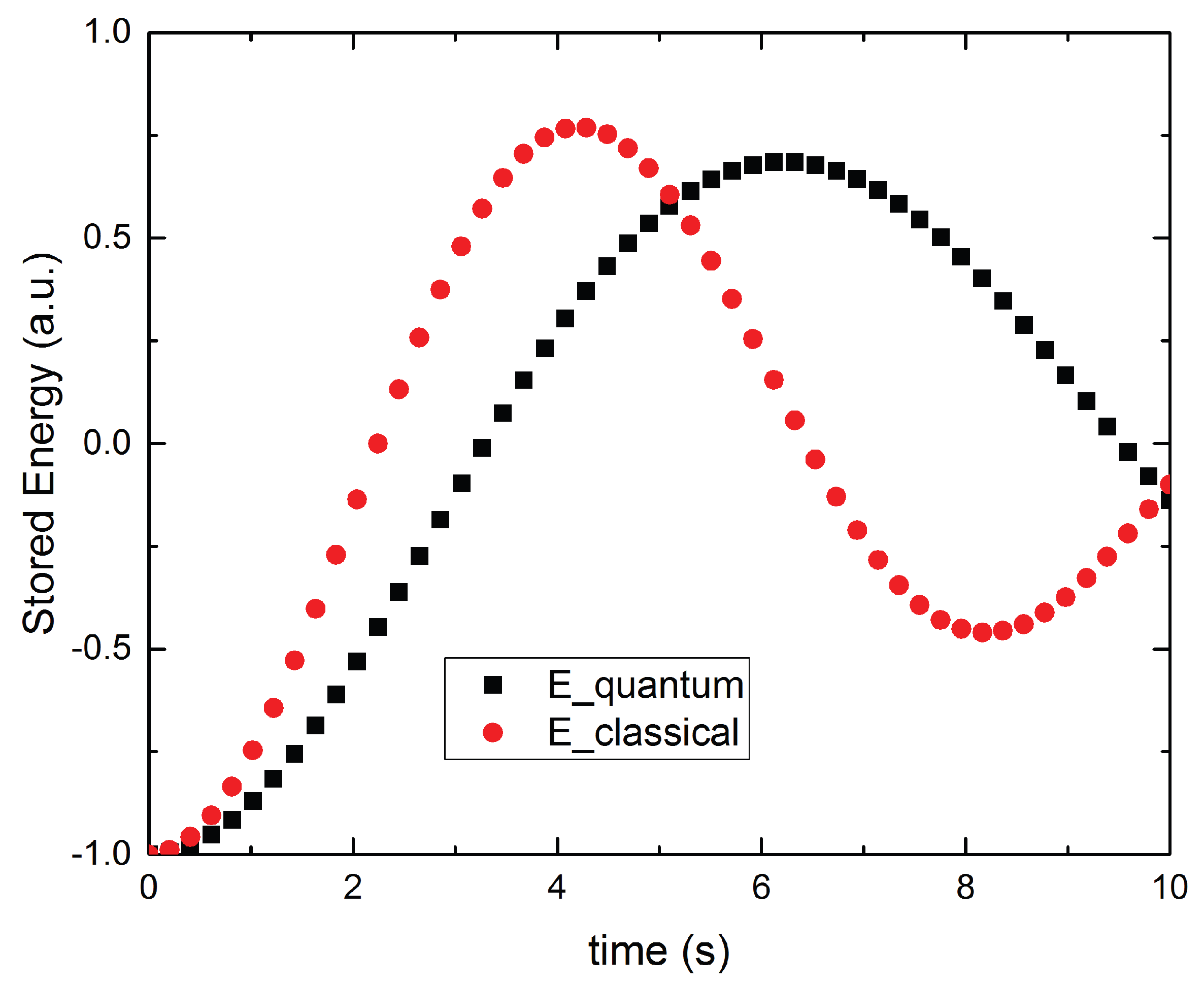

4.1. Energy Dynamics

Figure 1 illustrates the time evolution of the stored energy for both the collective and parallel charging architectures at a representative system size (

). The collective battery exhibits a faster energy uptake and a higher peak stored energy compared to the parallel benchmark.

This enhancement originates from the coherent exchange of excitations between the cavity field and the collective spin degree of freedom, which gives rise to oscillatory dynamics reminiscent of superradiant behavior in strongly coupled light–matter systems [

7]. In contrast, the parallel architecture displays independent Rabi oscillations in each TLS–cavity subsystem, resulting in slower and strictly additive charging dynamics.

4.2. Scaling of Average Power

To quantify the collective advantage, we analyze the scaling of the average charging power with the number of battery cells.

Figure 1 shows the dependence of the average power

on

N for both charging paradigms.

For the collective battery, we observe a superlinear scaling of the form

with an exponent

over a finite range of system sizes, in agreement with previous theoretical predictions [

1,

4,

5]. By contrast, the parallel benchmark exhibits strictly linear scaling,

, as expected from the absence of collective correlations. These results confirm that collective coupling can enhance charging power beyond the limits of independent architectures under idealized conditions.

4.3. Robustness to Dissipation

We next investigate the impact of dissipation on the collective charging advantage by varying the cavity loss rate and the TLS relaxation rate . Both sources of noise act to suppress the coherent build-up of collective excitations, thereby reducing the effective light–matter coupling strength and degrading the superlinear scaling behavior.

Figure 1.

Time evolution of the stored energy in the collective (solid line) and parallel (dashed line) charging architectures for a representative system size . The collective battery exhibits faster charging dynamics and a higher peak stored energy due to coherent collective coupling between the cavity field and the ensemble of two-level systems. Parameters correspond to the reference simulation discussed in the text.

Figure 1.

Time evolution of the stored energy in the collective (solid line) and parallel (dashed line) charging architectures for a representative system size . The collective battery exhibits faster charging dynamics and a higher peak stored energy due to coherent collective coupling between the cavity field and the ensemble of two-level systems. Parameters correspond to the reference simulation discussed in the text.

For weak dissipation (

), the collective battery retains a modest superlinear enhancement of the average charging power. However, as the dissipation rates increase, the scaling exponent decreases and the ratio

approaches unity, signaling a crossover to classical-like behavior. Collective advantages persist only in the regime where coherent coupling dominates over losses, approximately when

, in line with general arguments on the fragility of quantum advantages in open many-body systems [

6].

5. Discussion

We have presented a controlled numerical comparison between collective and parallel charging architectures for quantum batteries, using the Dicke model as a paradigmatic example of collective light–matter coupling. Our results confirm that collective charging can yield superlinear enhancements of the average charging power under idealized conditions, in agreement with previous theoretical analyses [

1,

4,

5].

Crucially, by treating dissipation on equal footing in both architectures, we have shown that these advantages are not generically robust. Cavity losses and TLS relaxation suppress the coherent build-up of collective excitations and drive a crossover toward linear, classical-like scaling. The collective advantage persists only when the coherent coupling strength dominates over dissipative processes, approximately when . This identifies a clear operational regime in which collective quantum batteries can outperform non-collective benchmarks, and delineates the limits imposed by environmental noise.

More broadly, our findings emphasize the importance of carefully distinguishing genuine quantum advantages from enhancements arising solely from interaction topology or correlated driving. In realistic open-system settings, collective charging benefits are inherently fragile and require stringent coherence conditions. From an experimental perspective, this suggests that demonstrating scalable quantum advantages will likely require both optimized coupling strengths and strategies for mitigating dissipation.

6. Outlook

Several directions merit further investigation. First, unraveling the Lindblad dynamics using Monte Carlo wavefunction techniques would enable the study of trajectory-level fluctuations and the role of rare events in collective charging. Second, exploring alternative charger states, such as squeezed or thermal fields, may offer routes to enhance robustness against losses. Third, extending the present analysis to experimentally realistic parameter regimes in cavity QED and organic microcavity platforms would facilitate closer contact with ongoing implementations. Finally, investigating the interplay between collective charging and local control constraints [

6], as well as hybrid architectures such as spin–mechanical quantum batteries [

8], may provide new pathways toward practical and scalable quantum energy-storage devices.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges support from CONICET (Argentina), and SECAT, Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires.

References

- F. Campaioli, M. T. Mitchison, J. Goold, and N. Friis, Colloquium: Quantum Batteries, Rev. Mod. Phys. (in

press), arXiv:2308.02277 (2023).

[CrossRef]

- Dicke, R. H. Coherence in spontaneous radiation processes. Phys. Rev. 1954, 93, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolina, G. M.; Mari, A.; Polini, M.; Giovannetti, V. Quantum versus classical many-body batteries. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 98, 205423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, D.; Campisi, M.; Andolina, G. M.; Pellegrini, V.; Polini, M. High-power collective charging of a solid-state quantum battery. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, F. C.; Vinjanampathy, S.; Modi, K.; Goold, J. Quantum thermodynamics of general quantum processes. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 075015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolina, G. M.; Keck, M.; Mari, A.; Campisi, M.; Giovannetti, V.; Polini, M. Extractable work, the role of correlations, and asymptotic freedom in quantum batteries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 047702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günter, G. , Sub-cycle switch-on of ultrastrong light–matter interaction. Nature 2009, 458, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.-C. Spin-mechanical quantum battery. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 105, 012203. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).